Abstract

Replacing cement with supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) is widely recognized as an effective strategy to reduce the environmental footprint of cement production. However, focusing solely on technical or environmental dimensions is insufficient for drawing comprehensive sustainability conclusions. A thorough evaluation requires integrating key sustainable development indicators across all life-cycle stages. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a valuable tool that quantifies environmental impacts across all stages of a product’s life, including green concretes, which are often assessed from cradle to gate. This study examined the technical, economic, and environmental performance of self-consolidating concretes (SCCs) incorporating various SCMs, including silica fume (SF), ground granulated blast furnace slag (GS), metakaolin (MK), and pumice (PU), across 13 mix designs. The technical evaluation included measures of slump flow, compressive strength, and chloride migration, along with a service life prediction model to estimate long-term environmental impacts associated with each mix. Furthermore, an expert questionnaire was developed to prioritize the importance of these performance indicators from construction professionals’ perspectives. The results indicate that mixes containing 20% and 15% metakalolin or 15% silica fume demonstrated superior performance across combined technical, environmental, and economic criteria, as confirmed by expert evaluations. Compared to the control mixture, these mixes achieved CO₂ emission reductions of 94%, 93%, and 89% per cubic meter per service-year, respectively. Experts prioritized the highest weightage to the technical criterion (66%), followed by economic (21%) and environmental (13%) considerations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Self-consolidating concrete (SCC) is characterized by its high fluidity, which facilitates pumping, placement, and compaction—particularly in concrete structural elements with densely reinforced steel bars1,2,3. To achieve desirable fresh properties of SCC, such as the ability to flow around congested reinforcement zones and to avoid segregation, a high binder content is generally required, mainly in the form of Portland cement (PC)4. However, increasing the content of PC results in more expensive concrete with reduced environmental compatibility5,6. Cement is a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions7,8 and plays a significant role in the depletion of natural resources9. In pursuit of sustainable development goals, extensive efforts have been made to mitigate the adverse environmental impacts of construction operations by reducing cement consumption10,11. One of the key strategies in this regard is the partial replacement of PC with supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs). This shift has led to the emergence of a new type of SCC—featuring lower cement content and acceptable performance—commonly referred to as eco-efficient SCC or Eco-SCC12,13. This approach not only reduces dependence on non-renewable resources and minimizes construction waste14, but also decreases annual CO₂ emissions, which have become a global concern15,16. Nonetheless, compared to conventional SCC, Eco-SCC poses several challenges, including reduced paste volume, increased water content, and lower viscosity, making the mix more susceptible to segregation and bleeding17. Additionally, it is more challenging to attain the required mechanical and durability properties due to the lower binder content17,18. Integrating SCMs into SCC at higher levels has become a global endeavor to guarantee technical performance while lowering the cement content and SCC’s carbon footprint19,20.

Previous studies21,22,23 have investigated the effects of various SCMs on the fresh, mechanical, and durability properties of SCC. The main SCMs in previous studies include silica fume, ground granulated blast furnace slag, metakaolin, and pumice. Silica fume, a by-product of silicon and ferrosilicon alloy production24, significantly enhances compressive strength and durability performance25. Although its cost is relatively high compared to other SCMs26,27, its mechanical benefits are considerable. Most studies recommend replacing 10–15% of OPC with SF as an optimal range28,29,30,31. Within this range, SF has demonstrated the best performance in improving compressive strength and reducing permeability to water and chloride ions32,33,34,35. Ground granulated blast furnace slag (GS), a by-product of the steel industry, has been widely used as a partial replacement for Portland cement in self-consolidating concrete due to its ability to retain mechanical properties and enhance certain durability characteristics36. GS can be used to replace PC in varying proportions, typically ranging from 20% to 80%, contributing to reduced heat of hydration and improved long-term strength and durability of concrete25,37,38. Economically, GS is generally comparable in cost to ordinary cement25,27. Research has shown that SCC mixtures containing GS may initially exhibit lower early-age strength compared to control mixes39, yet their long-term performance is favorable40,41. The optimum replacement level for maximizing compressive strength is typically reported between 30% and 50%.

Metakaolin is another highly pozzolanic mineral that can enhance both the compressive strength and durability of concrete42. Several studies have demonstrated that incorporating MK into concrete improves pore structure, reduces overall porosity, and consequently enhances mechanical performance43,44,45. Pumice, on the other hand, is a volcanic rock composed of coarse-textured volcanic glass, which may or may not contain crystalline minerals. Replacing 10% to 20% of cement with pumice has been shown to improve compressive strength and water absorption characteristics. Studies indicate that pumice exhibits the highest water absorption rate when substituted at 10% by weight46.

Growing concerns over climate change and environmental degradation have prompted the creation of diverse tools and metrics designed to assess these issues and offer actionable strategies for their mitigation. In the context of green concrete, environmental evaluation necessitates a life cycle assessment (LCA) framework that captures the full spectrum of the production process, from raw material extraction to end-of-life disposal47. LCA has become a widely adopted method for assessing the environmental performance of materials and systems. It enables detailed comparisons, systematic analyses, and the identification of critical environmental impact points within various production pathways48. In parallel, sustainability considerations are essential when assessing the environmental impact of concrete production. When using SCMs, their influence on concrete performance must be analyzed from multiple perspectives. While the use of recycled waste materials in concrete production introduces negligible direct environmental impact, a comprehensive framework that includes all stages of the production chain—such as raw material extraction, transportation, utilization, and end-of-life disposal—is necessary. LCA tools allow for a scientifically rigorous evaluation of the environmental impact throughout the life cycle of a product or process15.

Despite the multitude of studies conducted on concrete incorporating supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) (see Table 1), comprehensive life cycle assessments (LCAs) that integrate both environmental and economic dimensions of these materials remain limited. Although SCMs have been extensively studied from technical perspectives, the available data is still fragmented and lacks an integrated sustainability approach. While some research focuses solely on mechanical performance and durability, other studies address environmental impacts associated with so-called “green” concretes. To address this research gap, the present study evaluates the use of four commonly used SCMs—namely silica fume, slag, metakaolin, and pumice—in SCC. In addition to assessing the technical performance of these materials across various mix designs, life cycle-based environmental and economic analyses have also been conducted. The study further includes service life and corrosion probability modeling using specialized software tools. For the environmental assessment, CO₂ emissions associated with the production of each material and mix design were quantified, while cost analysis was performed to address the economic dimension. Furthermore, sustainability indicators were weighted based on expert surveys conducted with professionals in the construction industry, and the results were utilized in a multi-criteria decision-making process to prioritize the concrete mix designs. Ultimately, the technically, environmentally, and economically optimal SCC mixtures were identified. All assessments accounted for regional variability in Iran across the entire concrete production process.

Research methodology

The conceptual framework of this study is presented in Fig. 1. Based on the analysis of experimental results, a structured questionnaire was designed to gather expert input from professionals in the construction industry. This input was used to assign sustainability scores to various green self-consolidating concrete mix designs. The mix design that received the highest sustainability rating was ultimately selected as the optimal solution.

Experimental program

Materials

Ordinary Portland Cement (PC) Type II was used as the primary binder in this study. Supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) included silica fume (SF), ground granulated blast furnace slag (GS), metakaolin (MK), and pumice (PU). The physical and chemical properties of PC and SCMs are presented in Table 2.

Concerning chemical admixtures, particular attention was given to achieving an optimal aggregate gradation capable of producing SCC with a slump flow of 70 cm—without the need for any viscosity-modifying agent (VMA). Instead, a third-generation high-range water-reducing admixture (HRWRA), based on modified polycarboxylates and commercially known as Fercoplast P10-3R, was utilized. The specifications of this admixture are detailed in Table 3. The HRWRA used in this study is classified as a Type G admixture according to ASTM C49484.

Angular natural coarse and fine aggregates with maximum particle sizes of 12.5 mm and 6 mm, respectively, were selected. The water absorption and saturated surface-dry (SSD) densities were measured as 2.28% and 3.2% for fine and coarse aggregates, with corresponding SSD densities of 2540 and 2550 kg/m³. According to ASTM C3385, the sand-to-coarse aggregate ratio was maintained at 60% and 40% by weight of the total aggregates, respectively. The particle size distribution was compared with the recommended grading envelope for 12.5 mm maximum size aggregates, as provided by the national method. As shown in Fig. 2, the gradation curve of the selected aggregates closely aligns with the average grading curve.

Mix design

To investigate the effect of type and content of SCMs, the total binder content and the water-to-binder (w/b) ratio were kept constant at 450 kg/m³ and 0.40, respectively. The w/b ratio of 0.4 was selected based on recommendations for ensuring the durability of concrete. The dosage of the high-range water-reducing admixture was adjusted such that all mixes exhibited similar workability, targeting a slump flow of 70 ± 2 cm. For naming the SCC mix designs, abbreviations were used as follows: CTL refers to the control mix containing only ordinary Portland cement; SF, GS, MK, and PU represent mixes incorporating silica fume, slag, metakaolin, and pumice, respectively. The number following each abbreviation indicates the percentage replacement of PC with the corresponding SCM. The mix proportions of all SCC samples used in this study are presented in Table 4.

Experimental tests

In this study, three types of experimental tests were conducted to evaluate the SCC mixtures: the slump flow test for fresh properties, the compressive strength test for mechanical properties, and the rapid chloride migration test for durability. The slump flow test was performed following EFNARC guidelines86, which is widely recognized as a reliable and practical method for evaluating the workability of fresh SCC. The results of the slump flow diameter were recorded, as illustrated in Fig. 3a. For Compressive strength test, cubic concrete specimens with dimensions of 15 × 15 × 15 cm were prepared and cured for 28 days in saturated lime-water following ASTM C3987. The average of the results for three specimens was reported for each mix design (Fig. 3b). To evaluate durability, the rapid chloride migration test (RCMT) was conducted based on electrical migration techniques and in accordance with NT Build 49288. For sample preparation, concrete cylinders of 20 × 10 cm were cast and sliced into three discs with dimensions of 10 cm in diameter and 5 cm in height at the required age. The apparent chloride diffusion coefficient was determined using three samples for each mix at 28 days (Fig. 3c).

Software-based service life modeling

To assess the impact of SCMs on concrete durability and longevity, this study utilized a service life prediction tool explicitly designed for reinforced concrete structures. Service-life estimates use a hybrid experimental-numerical approach. Though projections come from a numerical model (e.g., Fick’s Second Law), key inputs—chloride diffusion coefficients—are experimentally determined via standard tests (RCMT). This yields robust predictions of extended service life that would be impractical to obtain from long-term exposure alone. The software was applied to estimate the expected service life of various SCC mixtures exposed to aggressive environmental conditions characteristic of the Persian Gulf region, based on their durability performance. The software is developed locally and tested in corrosive environments such as seashores, ports, and marine structures in southern Iran. It can be deployed in similar conditions globally, consistent with recent fib (International federation for structural concrete) recommendations for estimating the service life of reinforced concrete. The software uses the fib Bulletin 34 model code89 to predict chloride ion penetration in concrete.

To perform modeling in software, several parameters are required, including: apparent chloride diffusion coefficient, ambient temperature, concrete cover depth, initial surface chloride concentration, and corrosion threshold. These input parameters—derived from experimental measurements—are listed in Tables 5 and 6. The chloride diffusion coefficient (DRCMT) is one of the key parameters characterizing the durability of the material, obtained from the accelerated chloride migration test88. In the software, this coefficient is assumed to follow a normal distribution, where the mean value is based on 28-day laboratory test results, and the standard deviation is taken as approximately 20% of the mean value, as suggested by the software developers. Figure 4 shows a screenshot of the software interface and the input parameter configuration.

Environmental assessment

In this research, the environmental assessment was conducted based on the LCA methodology in accordance with ISO standards 14,04091 and 14,04492. Through LCA, the amount of carbon dioxide emitted per kilogram of production and transportation of each material used in the concrete mixtures was calculated. The data in this section reflects the most recently published statistics in Iran. In the sections where updates were unavailable or lacking, estimates were derived inputs from experts in the field. Although a multi-impact LCA offers deeper insights, this study focused solely on CO2 emissions because local data for other environmental categories were inconsistently available or incomplete across materials. CO2 is a widely acknowledged, fundamental, and dominant criterion in environmental assessment. It is the most commonly reported metric in similar studies, aiding comparability within the study and with the broader literature.

Portland cement

Cement production follows a set standard, and the same procedure is employed virtually everywhere in the world. Cement production comprises several stages, including raw material extraction, transportation to the plant, grinding, calcination, and final delivery to the construction site. Since the transportation distance of raw materials to the plant significantly influences emissions during the delivery stage, Table 7 outlines the source location of each material along with the distance required for transport to the project site.

It is important to note that raw material extraction was excluded from the scope of this study. This omission reflects a conservative approach to evaluating the benefits of SCMs, as including the emissions associated with raw material extraction would have resulted in even higher CO₂ estimates for conventional cement production than those reported in the current analysis. The chosen system boundary for the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is primarily a ‘cradle-to-gate’ approach, extending only partially into the construction phase. Crucially, the raw material extraction for cement production was excluded due to the absence of consistent and verifiable localized data. This exclusion provides a conservative estimate of the environmental burdens. Since the extracted materials’ impacts predominantly contribute to the overall CO2 emissions, their inclusion would further substantiate the environmental superiority of the mixtures incorporating SCMs.

The raw materials commonly used in the cement industry—namely limestone and clay—are transported to the manufacturing facility after extraction. Since most cement factories source their raw materials from nearby quarries to minimize transportation costs and time, an average hauling distance of 60 km is assumed. A 22-ton diesel truck typically consumes around 50 L of diesel per 100 km, which corresponds to a fuel consumption rate of approximately 0.02273 L per ton-km. According to the energy balance sheet, the combustion of each liter of diesel in road transport emits 2806.413 g of CO2. Moreover, based on prior studies, the production of 1 kg of cement requires about 1.6 kg of raw material93.

In the next stage, the ground raw material is transferred to the kiln for calcination. This stage consumes the largest amount of energy and accounts for the majority of CO₂ emissions associated with cement production. Since roughly 75% of the raw material is limestone, it is estimated that approximately 1.2 kg of limestone is used for every kilogram of cement produced93. Using molar mass relationships, the amount of carbon dioxide released from heating 1.2 kg of limestone can be calculated;

-

1 mol CaCO3 = 100 g, 1 mol CO2 = 44 g.

-

CO2-Eq =(44/100)× 1200 = 528 g.

Throughout the cement production process—including clinker production, crushing, and grinding—significant energy consumption leads to greenhouse gas emissions. According to the energy balance sheet 200794, the production of 1 kg of clinker requires approximately 850 kilocalories (3570 kJ) of thermal energy and 0.1 kWh of electrical energy. Based on the energy balance sheet, 60% of the thermal energy in cement plants is derived from natural gas, and the remaining 40% from heavy fuel oil (mazut). Therefore:

-

Calorific value of natural gas: 48,000 kJ/kg = 32,640 kJ/m³.

-

CO₂ emissions from burning natural gas in industry: 2162.683 g/m³.

-

Calorific value of mazut: 41,300 kJ/kg = 37,170 kJ/li.

-

CO₂ emissions from burning mazut in industry: 3329.138 g/L.

-

CO₂ emissions from electricity consumption: 450 g/kWh.

In the final grinding stage, the produced clinker is blended with additives such as gypsum, pozzolan, and other components, and ground into cement. On average, grinding mills consume about 6700 kWh per kiloton of cement95, with every kWh of electricity resulting in approximately 0.45 kg of CO₂ emissions96. Additionally, emissions from transporting the final cement product to the construction site are calculated based on distances given in Table 7.

Silica fume

Since silica fume is a by-product of ferroalloy production, it does not generate carbon dioxide emissions during its manufacturing process. The only CO₂ emissions associated with silica fume arise from its transportation, which spans a distance of 1723 km, as noted in Table 7.

Slag

Slag, a by-product of the steel manufacturing process, is formed during the separation of impurities from iron in blast furnaces. Similar to silica fume, the use of slag does not involve direct carbon emissions, and its environmental impact is solely due to transportation. It is sourced from the Esfahan Steel Company, requiring a transport distance of 1467 km to the project site.

Metakaolin

According to previous studies, 1 kg of metakaolin is produced by the calcination of 1.12 kg of kaolin. As many cities are near active kilns, the average transport distance to kilns is assumed to be 30 km. Kaolin needs to be heated to 700 °C. To calculate the fuel required for this process, it is assumed that kilns operate at 50% thermal efficiency to account for energy loss. Based on emission factors for fuels in industrial applications, burning 1 L of diesel emits about 2817.68 g of CO₂. The energy calculations are as follows:

-

Specific heat of kaolin97: 1000 J/kg·K.

-

Diesel calorific value: 44,000 kJ/kg = 37,400 kJ/L.

-

Q = m × c × ΔT = 1.12 × 1000 × 700 = 784,000 J = 784 kJ.

-

Ideal diesel required = 784/37,400 ≈ 0.021 L.

-

Actual diesel used with 50% efficiency = 0.042 L.

Additionally, to ensure that the metakaolin exhibits its desired properties in concrete mixtures, it must be finely ground. Emissions from transporting this material to the project site are calculated based on Table 7 distances.

Pumice

As for pumice, carbon emissions are assessed for three stages: transportation to the grinding facility, the grinding process itself, and final transportation to the project site. These calculations follow the same methodology as those used for other supplementary cementitious materials. Considering that the primary pumice production zone in Iran is located near the city of Khash, the hauling distance from Khash to Konarak is shown in Table 7.

Economic evaluation

To conduct the economic evaluation of the studied concrete mixtures, the cost per kilogram of each material was determined. Based on the specific mix proportions, the total cost for each concrete mixture was calculated. For better comparison, each mix was benchmarked against the control mix. The cost assessment is based on the final, ex-factory purchase price of the finished materials. This price implicitly incorporates fundamental economic factors such as labor, energy, equipment depreciation, and manufacturing overhead costs incurred during the production process, thereby representing a comprehensive assessment of the material’s cost contribution to the concrete mix. Material and transport costs were evaluated using Iranian cost data, and the prices shown in this study align with Iran’s market rates for the first six months of 2022.

Evaluation of criteria weights

To better assess the performance of the concrete mix designs developed in this study, a structured questionnaire was designed to prioritize the alternatives based on selected evaluation parameters. These parameters include technical criteria (such as workability, compressive strength, and resistance to chloride ion penetration), environmental criteria (i.e., carbon dioxide emissions), and economic criteria (i.e., concrete production cost). To perform the prioritization, the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP)98, a well-known multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) method, was employed (Fig. 5). In the AHP procedure, pairwise comparisons were conducted among the parameters based on the AHP scale presented in Table 8. The pairwise comparison data were then entered into the Expert Choice software to determine the relative weight of each criterion.

Ethical statement

All methods involving the survey of experts were performed in accordance with relevant ethical guidelines and regulations. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Amirkabir University of Technology. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants (experts) included in the study. Before agreeing to participate, all experts were provided with detailed information regarding the research objectives, the voluntary nature of their participation, and how their anonymized data would be used.

Results

Technical assessment results

Slump flow diameter

One of the distinct characteristics of self-compacting concrete that differentiates it from conventional concrete is its fresh and flowable behavior99. Considering that different dosages of superplasticizer were used in this study to achieve target slump flow values, a direct comparison of slump diameters may not be appropriate. Therefore, Fig. 6 illustrates the ratio of the superplasticizer dosage (by weight%) to the slump flow diameter (SP/D) for each concrete mix design. According to the results, SCC mixes incorporating SF exhibited higher SP/D ratios due to the higher specific surface area of SF particles25, which increases the demand for admixtures. Conversely, mixes containing ground slag demonstrated lower SP/D values, attributable to the smooth surface texture of slag particles25,27, which enhances flowability. This trend is more pronounced at higher replacement levels of GS. Metakaolin, due to its finer particle size compared to PC, behaves similarly to silica fume and increases the mixture’s viscosity, requiring higher SP dosages to achieve the same workability. Pumice-based mixes displayed behavior relatively similar to the control sample, likely due to the counteracting effects of increased paste volume and fineness, which tend to offset each other73.

Compressive strength

The 28-day compressive strength results shown in Fig. 7 indicate that all SCC mixes incorporating supplementary cementitious materials—except for those containing pumice—achieved higher compressive strength compared to the control mix. This is primarily due to the pozzolanic reaction of SCMs with cement hydration products, particularly calcium hydroxide, resulting in the formation of additional calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H) gel, which leads to a denser microstructure and enhanced strength100,101. In contrast, pumice-containing mixes exhibited lower 28-day compressive strength compared to the control, likely due to the dilution effect and the relatively slower pozzolanic reaction of pumice with calcium hydroxide71,74. However, it is expected that strength will increase at later ages as the pozzolanic reaction progresses and additional C-S-H gel forms. Among the studied mixes, those containing silica fume demonstrated the highest compressive strength, owing not only to its strong early-age pozzolanic activity but also to its filler effect, which densifies the cement paste and enhances strength52,55.

Rapid chloride migration test (RCMT)

Similar to the compressive strength results, all SCC mixes containing SCMs—except for those with pumice—showed lower chloride ion diffusion coefficients compared to the control mix, as depicted in Fig. 8. This reduction in diffusion can be attributed to both the chemical and physical effects of SCMs in the concrete matrix21,22,23. Chemically, SCMs react with calcium hydroxide to form additional C-S-H gel, reducing pore connectivity. Physically, their fine particles fill the voids and enhance the overall density of the matrix, lowering permeability79,102. Together, these mechanisms contribute to the reduced chloride ion diffusion observed in SF, GS, and MK mixes. For pumice-based mixes, the diffusion coefficients were slightly higher than the control, except for PU30, which showed an improved result. This can be explained by the relatively slow pozzolanic activity of pumice and its particle fineness71, which is similar to that of PC. It is expected that, over time, as the hydration and pozzolanic reactions progress, the chloride ion diffusion coefficients for pumice-containing mixes will further decrease.

Estimated service life and corrosion probability

Figure 9 presents the probability of reinforcement corrosion for all studied concrete mixes after 50 years of service life. According to the results, mixtures containing metakaolin exhibited the highest corrosion resistance. This outcome is directly linked to the lower chloride ion diffusion coefficients observed in MK-containing samples. In essence, the greater the chloride diffusion coefficient of a sample, the higher its permeability and corrosion risk. This relationship is inferred when comparing Figs. 8 and 9.

Figure 10 illustrates the estimated service life of the various mix designs. For this calculation, a corrosion threshold of 10% was considered. The lower the corrosion probability, the longer the predicted service life64. Therefore, MK-containing mixes demonstrated the longest estimated service life, with the MK20 mix reaching approximately 116 years. Following MK, mixes containing SF also performed well in terms of durability. In contrast, the service life of all other mixes was below 20 years, indicating a significant reduction in durability compared to the MK and SF-based concretes.

Environmental assessment results

Environmental performance of PC and SCMs

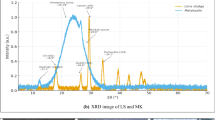

The amount of CO₂ emissions in each stage of processing and the contribution of each stage to the total emissions for PC and other SCMs are summarized in Table 9. While the majority of CO₂ emissions associated with the use of SF, GS, and PU are due to transportation, in the case of PC and MK, emissions are primarily generated during thermal processing (i.e., calcination and firing). This indicates that improving energy efficiency in production methods can significantly reduce the environmental footprint of these materials55. Figure 11 illustrates the total CO₂ emissions per kilogram for each material. According to the results, the production of PC (~ 861 g/kg) generates more CO₂ than the studied SCMs. Among the SCMs, MK had the highest carbon footprint, while PU demonstrated the lowest CO₂ emissions and environmental impact. Therefore, partial replacement of PC with SCMs in concrete can lead to meaningful reductions in the environmental consequences of cement use74.

Environmental performance of SCC

To evaluate the environmental performance of each SCC mix design, the amount of CO₂ emissions per cubic meter of concrete was calculated and compared (Fig. 12). Based on previous studies103, the emissions associated with non-cementitious components of concrete—such as aggregates (sand and gravel), water, and chemical admixtures—are estimated to be approximately 10 kg per cubic meter of concrete. As illustrated in Fig. 12, the highest level of CO₂ emissions—and consequently the poorest environmental performance—is associated with the control SCC mix, due to its high PC content. When SCMs are introduced as partial replacements for PC, CO₂ emissions are significantly reduced. Furthermore, this reduction in emissions becomes more pronounced with higher replacement levels of SCMs. Among the studied mixes, GS40 (containing 40% slag) demonstrated the lowest CO₂ emissions and thus the best environmental performance, which is attributed to its high PC replacement ratio.

It is important to note that the results presented here only reflect emissions from the production and transportation phases of each mixture. The long-term durability and service life impacts of these mixes are discussed in the following sections.

Economic assessment results

Economic performance of PC and SCMs

Figure 13 provides details of the production and transportation costs for 1 kg of SCMs relative to cement. According to the data, pumice is the most economical SCM, while metakaolin is the most expensive. Pumice, which is locally sourced from the Sistan and Baluchestan province near the project site, incurs the lowest transportation cost among the SCMs studied. In contrast, metakaolin exhibits the highest production cost due to the high energy requirements for calcination and prolonged grinding processes. Although silica fume, slag, and pumice all exhibit lower production costs than PC, the overall costs of SF and GS exceed those of PC because of their significant transportation distances. As a result, except for pumice, all SCMs evaluated in this study cost more than PC when both production and transport costs are considered.

From a short-term economic perspective focused solely on upfront material costs, incorporating SCMs into concrete may not appear financially justified. However, this conclusion could change when additional factors—particularly durability and extended service life—are considered in a holistic sustainability framework78.

Economic performance of SCC

The economic performance of the SCC mixtures was assessed by comparing both the total production cost per m³ and the total cost over the structure’s useful life (as depicted in Fig. 10) against the control mixture (CTL) shown in Fig. 14. The cost required to produce one m3 of each mix include all concrete constituents and transportation to the construction site is shown in Fig. 14. These constituents include PC, SCMs, aggregates (coarse and fine), and HRWRA. Figure 14 indicates that SCC mixtures containing pumice yield the lowest production costs, which is attributed to the lower unit price of pumice relative to PC and other SCMs, coupled with reduced transportation distances. Conversely, SCC mixtures incorporating metakaolin incur the highest costs, driven by the elevated price of metakaolin, longer transportation distances, and the greater HRWRA demand required to maintain workability.

According to Fig. 14, SCC containing SF, GS, and MK exhibited higher initial production costs, approximately 1.20, 1.16, and 1.33 times that of the control mix, respectively. However, when assessed over the structure’s service life, the corresponding lifetime costs were significantly lower in relative terms: about 0.32, 0.83, and 0.12 times the cost of the CTL. From the results, it is evident that for a robust comparison of the economic performance of green SCC, the total production cost over the structure’s service life provides a more accurate parameter than the initial production cost.

Comparison of mix designs based on multiple criteria

Technical, environmental, and economic criteria

Based on the previously obtained results, a comparative analysis was conducted for all mix designs using three main criteria: technical performance, environmental impact, and cost-efficiency. The details of the assessments, including the best and worst performing mixes under each criterion, are summarized in Table 10. The first combined index evaluated is the environmental-mechanical criterion, which considers the amount of CO₂ emitted per cubic meter of concrete per unit of compressive strength (kg CO₂/MPa). This index provides an integrated view of both structural efficiency and environmental burden. The comparative results for different mix designs are illustrated in Fig. 15. The findings show that mixtures with 20% MK, 15% MK, and 15% SF achieved CO₂ emission reductions of 94%, 93%, and 89% per cubic meter per service-year, respectively, relative to the control mixture.

According to the findings, SCC mixtures incorporating PU exhibited the weakest performance under this index. This is primarily due to their lower 28-day compressive strength. In contrast, SCC mixes with other SCMs displayed improved environmental-mechanical performance relative to the control mix (CTL). The best performance was recorded for the mix containing 40% slag (GS40), which emitted an average of 4.2 kg CO₂ per MPa of compressive strength per cubic meter. Conversely, the worst performance belonged to the SCC mix with 20% pumice (PU20), which released approximately 9.1 kg CO₂ per MPa.

Due to the inherently different units of measurement for environmental and economic indicators, it is not straightforward to simultaneously analyze and compare these two domains. Therefore, in this study, a data normalization approach was adopted. The control SCC mix (CTL) was used as the baseline for comparison, and performance indices were calculated accordingly. The comprehensive sustainability assessment index, combining environmental, economic, mechanical, and durability aspects, is defined as Eq. (1):

This equation facilitates the simultaneous assessment of all relevant sustainability dimensions for each concrete mixture. The resulting performance index for each mix design is presented in Fig. 16. Based on this integrated evaluation, the SCC mix incorporating 20% pumice exhibited the lowest overall performance. In contrast, the mix with 20% metakaolin achieved the highest combined performance across technical, environmental, and economic criteria. Moreover, all SCC mixes containing SCMs—except those incorporating 10% and 20% pumice—demonstrated superior performance compared to the control mix (CTL).

Ultimately, from a comprehensive standpoint—considering technical, environmental, and economic performance—the studied self-consolidating concrete mixtures can be ranked accordingly. Table 11 presents the ranking of the various SCC mix designs based on these three key sustainability criteria.

Sustainability index

Eco-friendly or sustainable SCC, which is produced with significantly reduced PC content, represents a promising pathway for improving the sustainability of concrete construction. However, producing such concrete is not straightforward, as it must retain all the traditional functional characteristics of cement and concrete, while also adapting to new mix designs and material proportions, often requiring specialized design and production methods. To comprehensively assess the sustainability of these concretes, not only their environmental impact, but also their technical performance—i.e., mechanical, physical, and chemical properties—must be considered94,104. One of the most recent and robust metrics proposed for such evaluation is the Building Material Sustainability Potential (BMSP) index, introduced by Müller et al.105. The BMSP is calculated as shown in Eq. (2):

In this equation, the numerator represents the product of the specimen’s compressive strength and its estimated service life, while the denominator is the amount of CO₂ emissions (in kilograms) for the production and transportation of one m3 of concrete. This index thus enables a holistic sustainability evaluation of SCC mixes, simultaneously accounting for environmental, mechanical, and durability aspects. The calculated BMSP values for all studied SCC mixes are shown in Fig. 17. According to the results, the ranking based on the BMSP index aligns with the combined ranking derived earlier from the technical, environmental, and economic assessments, except for the SCC mixes containing 10% and 20% pumice, where the 12th and 13th positions were interchanged.

Importance of criteria based on expert opinions

Scoring of mix designs

To develop the questionnaire, opinions of 30 experienced civil engineers with minimum 5 years of experience in concrete technology and durability were collected. These experts included academics, consultants, and contractors, whose opinions helped prioritize the sustainability indexes. The questionnaire was completed by 30 specialists: 10 contractors, 10 consultants, and 10 university professors and researchers. The sample was carefully selected to represent the entire population, ensuring the results are reliable and applicable. Based on the feedback from experts in the construction field, each of the considered evaluation criteria was prioritized according to its obtained weight (Fig. 18). According to the experts’ opinions, the technical, economic, and environmental criteria were assigned relative weights of 66%, 21%, and 13%, respectively. Among the sub-criteria of technical performance, chloride resistance was rated as the most important, with a weight of 59%, surpassing compressive strength and workability.

Moreover, using these parameter weights, each of the SCC mix designs was scored accordingly. The resulting rankings, generated by Expert Choice software, are summarized in Table 12 and visualized in Fig. 19. Based on the results, SCC with 20% metakaolin (MK20), 15% silica fume (SF15), and 15% metakaolin (MK15) achieved the highest composite scores across all considered criteria. On the other hand, the control mix (CTL) and SCC with 5% silica fume (SF5) showed the weakest performance in terms of technical, environmental, and economic indicators.

However, as illustrated in Table 12, the optimal mix design can change depending on the specific evaluation criterion. For example, from a workability or environmental performance perspective, GS40 (SCC with 40% slag) was found to be the most effective.

Comparison of mix designs with CTL

Figure 20 presents the comparative evaluation of different SCC mix designs against the control mix (CTL). Each mix was assessed across the various evaluation criteria and compared with the control in an integrated manner. The results indicate that technical and environmental performance significantly contributed to the superior overall performance of MK20, SF15, and MK15, despite these mixes demonstrating weaker economic performance compared to the control. This pattern is generally applicable across other mixes as well.

The results of the sensitivity analysis, extracted from the Expert Choice software output, for comparing the optimized mix designs in terms of technical, environmental, and economic performance, are presented in Fig. 21. As observed, SCC containing 20% MK demonstrates the best overall performance, while the mix containing 5% silica fume exhibits the worst performance.

Based on the results of the multi-criteria evaluation, the superiority and overall performance of a green self-compacting concrete mixture can be attributed to several key factors. One of the most critical is the chemical composition and reactivity of the SCMs. Materials such as metakaolin and silica fume play a direct role in pozzolanic reactions, the development of compressive strength, and the refinement of the concrete’s microstructure. Metakaolin, due to its high reactivity and its active role in reducing porosity and improving the microstructure, is more effective than silica fume—particularly at low replacement levels. This highlights the importance of carefully selecting the type and dosage of SCMs, as they have a significant impact on the final properties of the concrete.

Another crucial factor is the environmental benefit associated with reducing Portland cement consumption. Replacing a portion of cement with SCMs contributes to lower CO₂ emissions and improved environmental performance. In this regard, mixtures containing 20% and 15% metakaolin (MK20 and MK15) scored higher in the sustainability criteria of the multi-criteria analysis, due to their substantial reduction in cement content and thus carbon footprint.

However, economic considerations present a contrasting challenge. Despite their superior technical and environmental performance, the MK20 and MK15 mixes exhibited lower economic efficiency compared to the control mixture. This reflects the higher cost associated with procuring or processing specialized SCMs such as metakaolin. Hence, achieving a balance between enhanced durability and quality on the one hand, and cost-effectiveness on the other, remains a critical and complex trade-off.

To optimize the Eco-SCC mix, it is essential to concurrently address three core dimensions: technical performance, environmental sustainability, and economic feasibility. Several strategies are recommended in this regard:

-

Investing in the development and use of locally available, cost-effective SCMs with high pozzolanic activity;

-

Optimizing mix proportions through numerical modeling or multi-criteria decision-making algorithms to achieve a balanced trade-off;

-

Conducting further research on the behavior of SCMs in blended systems (e.g., combining MK with SF or FA) to leverage synergistic effects;

-

Performing life-cycle assessment to gain a more comprehensive understanding of long-term sustainability, beyond immediate indicators such as cement reduction.

Ultimately, the classification of a mix as “best” or “worst” cannot be determined by a single factor alone, but rather emerges from the interplay between technical specifications, economic constraints, and environmental demands. In contemporary concrete mix design, the use of multi-criteria analysis tools enables more informed and balanced decisions, supporting the broader goals of sustainable construction.

Conclusion

In this study, a life cycle assessment approach was employed to evaluate and compare the technical, economic, and environmental performance of green self-consolidating concretes incorporating four types of supplementary cementitious materials. The findings underscore the value of LCA in comprehensively assessing the sustainability benefits and associated trade-offs of alternative concrete materials. By integrating detailed performance data with a broad analytical framework, the study provides new insights that extend beyond those offered by previous research. The inclusion of regional context and the focus on less-explored SCMs further enhance the contribution, addressing a critical gap in the literature and offering practical guidance for selecting more sustainable materials in concrete construction. Key findings are summarized below:

-

Mixes containing 30–40% slag and 10–30% pumice demonstrated superior workability compared to the control mixture. Among these, the one containing 40% slag exhibited the highest flowability, while the one with 10% silica fume showed the lowest. In terms of compressive strength, all mixes outperformed the control except those containing pumice. The SCC incorporating 15% silica fume achieved the highest compressive strength. Additionally, all SCM-based SCCs—excluding mixes with 10% and 20% pumice—exhibited lower chloride ion diffusion coefficients than the control mix, with the 20% metakaolin mix showing the most significant resistance to chloride penetration.

-

Modeling results indicated that SCCs containing 15% silica fume and 10–20% metakaolin achieved projected service lives exceeding 50 years. Extended durability reduces annualized maintenance costs and contributes significantly to the sustainability score of MK- and SF-containing mixes. Improved durability translates into fewer repairs and replacements over the structure’s life span.

-

All green SCCs showed lower CO₂ emissions than the control mix. The SCC with 40% slag achieved the best environmental performance, with a carbon footprint approximately 35% lower than the control.

-

When evaluated by the integrated metric of CO₂ emissions per MPa of compressive strength per year of service life, the SCC with 20% metakaolin performed best, emitting only 2.94 kg CO₂/MPa-year. This mix also ranked highest in overall sustainability, with a 93% improvement in the composite technical–environmental–economic score compared to the control.

-

While most SCMs (excluding metakaolin) had lower production costs than cement, the inclusion of transportation costs led to higher total costs for some materials, such as silica fume and slag.

-

Overall, pumice-based SCCs showed better economic performance due to lower total material costs. Conversely, SCC with 20% metakaolin had the least favorable initial economic profile. However, when service life was considered, mixes containing SCMs—particularly metakaolin—proved significantly more cost-effective over the long term. MK20 emerged as the most economically viable option when evaluated on a per-year-of-service basis.

-

The technical criterion was deemed most important by construction industry experts, receiving a relative weight of 66%. Among technical sub-criteria, durability was prioritized highest, accounting for 59% of the technical weighting.

-

Based on an integrated sustainability assessment using the BMSP index and expert input, the SCC containing 20% metakaolin was identified as the most sustainable mix. In contrast, mixes incorporating 10% and 20% pumice demonstrated the weakest performance across all evaluated dimensions.

It is essential to interpret the findings of this study in light of its limitations: the cost and environmental data are specific to the geographical context of Iran, which may affect the generalizability of the results. While the methodology is broadly applicable, the quantified results for sustainability metrics are highly context-specific and may not be directly generalizable to international scenarios without recalibration to local conditions. Furthermore, the expert opinions are derived from a limited sample of 30 professionals, potentially not representing the entire industry’s perspective. Finally, the calculated service life is based on predictive modeling rather than long-term empirical data.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ahari, R. S., Erdem, T. K. & Ramyar, K. Permeability properties of self-consolidating concrete containing various supplementary cementitious materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 79, 326–336 (2015).

Long, G., Gao, Y. & Xie, Y. Designing more sustainable and greener self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 84, 301–306 (2015).

Sua-Iam, G. & Makul, N. Utilization of coal-and biomass-fired Ash in the production of self-consolidating concrete: a literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 100, 59–76 (2015).

el Safhi, M. Prediction of self-consolidating concrete properties using XGBoost machine learning algorithm: part 1–Workability. Constr. Build. Mater. 408, 133560 (2023).

Ranjbar, M. M. et al. Effects of natural zeolite on the fresh and hardened properties of self-compacted concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 47, 806–813 (2013).

Grunewald, S. & De Schutter, G. Effect of the mix design of self-compacting concrete: reduction of the environmental impact. Concrete Plant. Int. 2016 (5), 46–50 (2016).

Agwa, I. S. et al. Effects of using rice straw and cotton stalk ashes on the properties of lightweight self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 235, 117541 (2020).

Amin, M., Tayeh, B. A. & Agwa, I. S. Effect of using mineral admixtures and ceramic wastes as coarse aggregates on properties of ultrahigh-performance concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 273, 123073 (2020).

Sandanayake, M. et al. Sustainable criterion selection framework for green Building materials–An optimisation based study of fly-ash geopolymer concrete. Sustainable Mater. Technol. 25, e00178 (2020).

Mohammadi, P., Ramezanianpour, A. M. & Erfani, A. Identifying and prioritizing criteria for selecting sustainable façade materials of high-rise buildings. in Construction Research Congress 2022. (2022).

Madheswaran, C., Gnanasundar, G. & Gopalakrishnan, N. Effect of molarity in geopolymer concrete. Int. J. Civil Struct. Eng. 4 (2), 106–115 (2013).

Urban, M. Low cement content SCC (Eco-SCC)–the alternative for ready-mix traditional concrete. In MATEC web of conferences. (EDP Sciences, 2018).

Hu, J., Souza, I. L., Cortês, F. & Genarini. Engineering and environmental performance of eco-efficient self-consolidating concrete (Eco-SCC) with low powder content and recycled concrete aggregate. Journal of Sustainable Cement-Based Materials, 6(1), 2–16 (2017).

Gursel, A. P., Maryman, H. & Ostertag, C. A life-cycle approach to environmental, mechanical, and durability properties of green concrete mixes with rice husk Ash. J. Clean. Prod. 112, 823–836 (2016).

Vieira, D. R., Calmon, J. L. & Coelho, F. Z. Life cycle assessment (LCA) applied to the manufacturing of common and ecological concrete: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 124, 656–666 (2016).

Makul, N. Modern sustainable cement and concrete composites: review of current status, challenges and guidelines. Sustain Mater Technol 25, e00155 (2020).

Esmaeilkhanian, B., Khayat, K. & Wallevik, O. H. Mix design approach for low-powder self-consolidating concrete: Eco-SCC—Content optimization and performance. Mater. Struct. 50, 1–18 (2017).

Ashish, D. K. & Verma, S. K. An overview on mixture design of self-compacting concrete. Struct. Concrete. 20 (1), 371–395 (2019).

Xie, T. et al. Mechanical and durability properties of self-compacting concrete with blended binders. Computers Concrete Int. J. 22 (4), 407–417 (2018).

Da Silva, P. R. & De Brito, J. Durability performance of self-compacting concrete (SCC) with binary and ternary mixes of fly Ash and limestone filler. Mater. Struct. 49, 2749–2766 (2016).

Şahmaran, M., Christianto, H. A. & Yaman, İ. Ö. The effect of chemical admixtures and mineral additives on the properties of self-compacting mortars. Cem. Concr. Compos. 28 (5), 432–440 (2006).

Vejmelková, E. et al. Properties of self-compacting concrete mixtures containing Metakaolin and blast furnace slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 25 (3), 1325–1331 (2011).

el Safhi, M. Valorization of dredged sediments in self-consolidating concrete: Fresh, hardened, and microstructural properties. J. Clean. Prod. 263, 121472 (2020).

King, D. The effect of silica fume on the properties of concrete as defined in concrete society report 74, cementitious materials. In 37th Conference on our world in concrete and structures, Singapore. (2012).

Meyer, C. The greening of the concrete industry. Cem. Concr. Compos. 31 (8), 601–605 (2009).

Assi, L. et al. Sustainable concrete: Building a greener future. J. Clean. Prod. 198, 1641–1651 (2018).

Illankoon, I. C. S. et al. Life cycle costing for obtaining concrete credits in green star rating system in Australia. J. Clean. Prod. 172, 4212–4219 (2018).

Gesoğlu, M. & Özbay, E. Effects of mineral admixtures on fresh and hardened properties of self-compacting concretes: binary, ternary and quaternary systems. Mater. Struct. 40, 923–937 (2007).

Güneyisi, E., Gesoğlu, M. & Özbay, E. Strength and drying shrinkage properties of self-compacting concretes incorporating multi-system blended mineral admixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 24 (10), 1878–1887 (2010).

Johari, M. M. et al. Influence of supplementary cementitious materials on engineering properties of high strength concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 25 (5), 2639–2648 (2011).

Xu, W. et al. Pozzolanic reactivity of silica fume and ground rice husk Ash as reactive silica in a cementitious system: A comparative study. Materials 9 (3), 146 (2016).

Borosnyói, A. Long term durability performance and mechanical properties of high performance concretes with combined use of supplementary cementing materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 112, 307–324 (2016).

Vivek, S. & Dhinakaran, G. Durability characteristics of binary blend high strength SCC. Constr. Build. Mater. 146, 1–8 (2017).

Gesoğlu, M., Güneyisi, E. & Özbay, E. Properties of self-compacting concretes made with binary, ternary, and quaternary cementitious blends of fly ash, blast furnace slag, and silica fume. Constr. Build. Mater. 23 (5), 1847–1854 (2009).

Bhanja, S. & Sengupta, B. Optimum silica fume content and its mode of action on concrete. Mater. J. 100 (5), 407–412 (2003).

Bayat, H. et al. Durability, mechanical, workability, and environmental assessment of self-consolidating concrete containing blast furnace slag and natural zeolite. J. Building Eng. 86, 108737 (2024).

Kim, Y. et al. Slag waste incorporation in high early strength concrete as cement replacement: environmental impact and influence on hydration & durability attributes. J. Clean. Prod. 172, 3056–3065 (2018).

Malhotra, V. M. & Mehta, P. K. High-performance, high-volume fly ash concrete: materials, mixture proportioning, properties, construction practice, and case histories. (2002).

Zhao, H. et al. The properties of the self-compacting concrete with fly Ash and ground granulated blast furnace slag mineral admixtures. J. Clean. Prod. 95, 66–74 (2015).

Lee, H. S. et al. Analysis of the optimum usage of slag for the compressive strength of concrete. Materials 8 (3), 1213–1229 (2015).

Khan, K. M. & Ghani, U. Effect of blending of portland cement with ground granulated blast furnace slag on the properties of concrete. In Proceedings of the 29th conference on our world in concrete & structures, premier PTE LTD, Singapore. (2004).

Asadollahfardi, G., MohsenZadeh, P. & Saghravani, S. F. The effects of using Metakaolin and micro-nanobubble water on concrete properties. J. Building Eng. 25, 100781 (2019).

Güneyisi, E., Gesoğlu, M. & Mermerdaş, K. Improving strength, drying shrinkage, and pore structure of concrete using Metakaolin. Mater. Struct. 41, 937–949 (2008).

Maddalena, R., Roberts, J. J. & Hamilton, A. Can Portland cement be replaced by low-carbon alternative materials? A study on the thermal properties and carbon emissions of innovative cements. J. Clean. Prod. 186, 933–942 (2018).

Ženíšek, M., Vlach, T. & Laiblová, L. Dosage of Metakaolin in high performance concrete. Key Eng. Mater. 722, 311–315 (2017).

Alqarni, A. S. A comprehensive review on properties of sustainable concrete using volcanic pumice powder Ash as a supplementary cementitious material. Constr. Build. Mater. 323, 126533 (2022).

Khasreen, M. M., Banfill, P. F. & Menzies, G. F. Life-cycle assessment and the environmental impact of buildings: a review. Sustainability 1 (3), 674–701 (2009).

Bishop, G., Styles, D. & Lens, P. N. Environmental Performance Comparison of Bioplastics and Petrochemical Plastics: A Review of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Methodological Decisions. 168, 105451 (Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2021).

Sabet, F. A., Libre, N. A. & Shekarchi, M. Mechanical and durability properties of self consolidating high performance concrete incorporating natural zeolite, silica fume and fly Ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 44, 175–184 (2013).

Wongkeo, W. et al. Compressive strength and chloride resistance of self-compacting concrete containing high level fly Ash and silica fume. Mater. Design. 64, 261–269 (2014).

Benaicha, M. et al. Influence of silica fume and viscosity modifying agent on the mechanical and rheological behavior of self compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 84, 103–110 (2015).

Mastali, M. & Dalvand, A. Use of silica fume and recycled steel fibers in self-compacting concrete (SCC). Constr. Build. Mater. 125, 196–209 (2016).

Massana, J. et al. Influence of nano-and micro-silica additions on the durability of a high-performance self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 165, 93–103 (2018).

Alaghebandian, N., Mirvalad, S. & Javid, A. A. S. Durability of self-consolidating concrete and mortar mixtures containing ternary and quaternary cement blends exposed to simulated marine environment. Constr. Build. Mater. 259, 119767 (2020).

Nasir, M. et al. Strength, microstructure, and life cycle assessment of Silicomanganese fume, silica fume, and Portland cement composites designed using Taguchi method. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 36 (7), 04024190 (2024).

Uysal, M. & Sumer, M. Performance of self-compacting concrete containing different mineral admixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 25 (11), 4112–4120 (2011).

Boukendakdji, O., Kadri, E. H. & Kenai, S. Effects of granulated blast furnace slag and superplasticizer type on the fresh properties and compressive strength of self-compacting concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 34 (4), 583–590 (2012).

Ryan, P. C. & O’Connor, A. Comparing the durability of self-compacting concretes and conventionally vibrated concretes in chloride rich environments. Constr. Build. Mater. 120, 504–513 (2016).

Altoubat, S. et al. Restrained shrinkage behavior of Self-Compacting concrete containing ground-granulated blast-furnace slag. Constr. Build. Mater. 129, 98–105 (2016).

Mohammed, A. M., Asaad, D. S. & Al-Hadithi, A. I. Experimental and statistical evaluation of rheological properties of self-compacting concrete containing fly Ash and ground granulated blast furnace slag. J. King Saud University-Engineering Sci. 34 (6), 388–397 (2022).

Hamza, F. et al. Sustainable Self-Compacting concrete with recycled Aggregates, ground granulated blast Slag, and limestone filler: A technical and environmental assessment. Sustainability 17 (8), 3395 (2025).

Madandoust, R. & Mousavi, S. Y. Fresh and hardened properties of self-compacting concrete containing Metakaolin. Constr. Build. Mater. 35, 752–760 (2012).

Kavitha, O. et al. Fresh, micro-and macrolevel studies of Metakaolin blended self-compacting concrete. Appl. Clay Sci. 114, 370–374 (2015).

Badogiannis, E. G. et al. Durability of Metakaolin self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 82, 133–141 (2015).

Kavitha, O. et al. Microstructural studies on eco-friendly and durable Self-compacting concrete blended with Metakaolin. Appl. Clay Sci. 124, 143–149 (2016).

Gill, A. S. & Siddique, R. Strength and micro-structural properties of self-compacting concrete containing Metakaolin and rice husk Ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 157, 51–64 (2017).

Al-Oran, A. A. A., Safiee, N. A. & Nasir, N. A. M. Fresh and hardened properties of self-compacting concrete using Metakaolin and GGBS as cement replacement. Eur. J. Environ. Civil Eng. 26 (1), 379–392 (2022).

Ouldkhaoua, Y. et al. Effect of using Metakaolin as supplementary cementitious material and recycled CRT funnel glass as fine aggregate on the durability of green self-compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 235, 117802 (2020).

Samimi, K., Shirzadi, A. A. & Javid Magnesium sulfate (MgSO 4) attack and chloride isothermal effects on the self-consolidating concrete containing Metakaolin and zeolite. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Civil Eng. 45, 165–180 (2021).

OR, K. A Sustainable Approach to Enhancing the Durability of Scc Using Waste Foundry Sand and Metakaolin.

Samimi, K. et al. Influence of pumice and zeolite on compressive strength, transport properties and resistance to chloride penetration of high strength self-compacting concretes. Constr. Build. Mater. 151, 292–311 (2017).

Hedayatinia, F., Delnavaz, M. & Emamzadeh, S. S. Rheological properties, compressive strength and life cycle assessment of self-compacting concrete containing natural pumice Pozzolan. Constr. Build. Mater. 206, 122–129 (2019).

Magbool, H. M. & Zeyad, A. M. The effect of various steel fibers and volcanic pumice powder on fracture characteristics of Self-Compacting concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 312, 125444 (2021).

Khodaparast, A. et al. Effect of pumice on self-compacting Earth concrete: mechanical and microstructural characteristics, and life cycle assessments. J. Building Eng. 100, 111703 (2025).

Mohamed, O. A. & Najm, O. F. Compressive strength and stability of sustainable self-consolidating concrete containing fly ash, silica fume, and GGBS. Front. Struct. Civil Eng. 11, 406–411 (2017).

Langaroudi, M. A. M. & Mohammadi, Y. Effect of nano-clay on workability, mechanical, and durability properties of self-consolidating concrete containing mineral admixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 191, 619–634 (2018).

Salehi, H. & Mazloom, M. Opposite effects of ground granulated blast-furnace slag and silica fume on the fracture behavior of self-compacting lightweight concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 222, 622–632 (2019).

Vivek, S. & Dhinakaran, G. Fresh and hardened properties of binary blend high strength self compacting concrete. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 20 (3), 1173–1179 (2017).

Hassan, A. A., Lachemi, M. & Hossain, K. M. Effect of Metakaolin and silica fume on the durability of self-consolidating concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 34 (6), 801–807 (2012).

Gholhaki, M., Hajforoush, M. & Kazemi, M. An investigation on the fresh and hardened properties of self-compacting concrete incorporating magnetic water with various pozzolanic materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 158, 173–180 (2018).

Dadsetan, S. & Bai, J. Mechanical and microstructural properties of self-compacting concrete blended with metakaolin, ground granulated blast-furnace slag and fly Ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 146, 658–667 (2017).

Ardalan, R. B., Joshaghani, A. & Hooton, R. D. Workability retention and compressive strength of self-compacting concrete incorporating pumice powder and silica fume. Constr. Build. Mater. 134, 116–122 (2017).

Askarian, M., Fakhretaha Aval, S. & Joshaghani, A. A comprehensive experimental study on the performance of pumice powder in self-compacting concrete (SCC). J. Sustainable Cement-Based Mater. 7 (6), 340–356 (2018).

ASTM C494, Standard Specification for Chemical Admixtures for Concrete, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA.

ASTM C33/C33M-18, Standard Specification for Concrete Aggregates, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2018.

EFNARC, Specifications and guidelines for self-compacting concrete, European Federation of Producers and Applicators of Specialist Products for Structures,. (2002).

ASTM C39, Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength of Cylindrical Concrete Specimens, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, 2012.

NT Build 492, Nord test method: Chloride Migration Coefficients from Non-Steady-State, 1999.

Schießl, P. et al. Model Code for Service Life Design; Fib Bulletin No. 34 (International Federation for Structural Concrete, 2006).

Iranian Concrete Code of Practice, ABA. Management and Planning Organization of I.R. Iran, Ministry of Roads & Urban Development, Persian, 2020.

ISO-14040. I., Environmental Management–Life Cycle Assessment–Principles and Framework. (2006).

Standardization, I. O. Environmental Management: Life Cycle assessment; Requirements and Guidelines Vol. 14044 (ISO Geneva, 2006).

Gao, T. et al. Analysis of material flow and consumption in cement production process. J. Clean. Prod. 112, 553–565 (2016).

Mohammadi, A. & Ramezanianpour, A. M. Investigating the environmental and economic impacts of using supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs) using the life cycle approach. J. Building Eng. 79, 107934 (2023).

Jeswiet, J. & Szekeres, A. Energy consumption in mining comminution. Procedia CIRP. 48, 140–145 (2016).

U.S. Energy Information Administration, How much carbon dioxide is produced per kilowatthour of U.S. electricity generation? (2020). https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=74&t=11,.

Michot, A. et al. Thermal conductivity and specific heat of kaolinite: evolution with thermal treatment. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 28 (14), 2639–2644 (2008).

Saaty, T. L. Analytic hierarchy process. Encyclopedia of Operations Research and Management Science. 52–64 (Springer, 2013).

Bayat, H. et al. Durability, mechanical, workability, and environmental assessment of self-consolidating concrete containing blast furnace slag and natural zeolite. J. Building Eng. Vol 86, 108737 (2024).

Banar, R. et al. A comprehensive comparison between using silica fume in the forms of water slurry or blended cement in mortar/concrete. J. Building Eng. 46, 103802 (2022).

Banar, R. et al. Experimental and numerical simulation of carbonation-induced corrosion in reinforced concretes. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 22, e04464 (2025).

Nehdi, M., Pardhan, M. & Koshowski, S. Durability of self-consolidating concrete incorporating high-volume replacement composite cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 34 (11), 2103–2112 (2004).

Madani, H., Norouzifar, M. N. & Rostami, J. The synergistic effect of pumice and silica fume on the durability and mechanical characteristics of eco-friendly concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 174, 356–368 (2018).

Dashti, P. et al. Evaluation of sustainability performance of cementitious mortars containing silica fume. AUT J. Civil Eng. 6 (2), 175–190 (2022).

Müller, H. et al. A New Generation of Sustainable Structural Concretes–Design Approach and Material Properties. in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. (IOP Publishing, 2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RB: contributed to Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Visualization. MRG: contributed to Resources, Data curation, Formal analysis, Validation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing. AMR: contributed to Investigation, Resources, Project administration, Writing—review and editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Banar, R., GivKashi, M.R. & Ramezanianpour, A.M. Life cycle sustainability assessment of eco-friendly self-consolidating concretes using expert insights from the construction industry. Sci Rep 16, 4077 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34276-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34276-w