Abstract

To address the prediction and allocation challenges of emergency medical supplies during the middle and late stages of major outbreaks, we proposed an end-to-end ICSL deep learning algorithm architecture. This approach takes into account the characteristics of infectious diseases and the impact of government quarantine measures on their spread, enabling the prediction of the maximum demand for emergency medical supplies. Based on this, a multi-objective scheduling and allocation model was constructed, considering urgency, scheduling time, and cost. We designed a multi-objective particle swarm optimization algorithm to solve this model. Finally, we validated the algorithm using data from the Wuhan pandemic control measures. The results showed that the parameter update method improved the prediction accuracy of the LSTM model, increasing accuracy by 29.37% compared to the traditional LSTM algorithm and by 8.63% compared to the improved BP neural network algorithm. The proposed scheduling and allocation model optimizes delivery timeliness while also considering the urgency and cost-effectiveness of the resource allocation. The research findings can provide decision-making insights for the allocation of emergency medical supplies during public health emergencies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly impacted societies worldwide, posing significant challenges to public health systems and emergency response mechanisms. Public health emergencies such as pandemics, natural disasters, and large-scale accidents are characterized by their unpredictability, rapid escalation, and the critical need for timely and effective intervention1,2. Among these interventions, the efficient forecasting and allocation of emergency medical supplies play a pivotal role in saving lives, mitigating harm, and ensuring public safety3. These supplies, encompassing items like personal protective equipment (PPE), medical devices, and essential medicines, are indispensable in supporting healthcare workers, treating patients, and curbing the spread of infectious diseases4,5. However, the complex and dynamic nature of supply and demand during such crises often leads to significant logistical challenges, particularly during the middle and late stages of an outbreak when resource requirements are less predictable.

Current approaches to emergency medical supply management often rely on traditional forecasting methods and heuristic allocation strategies that struggle to account for the complex interactions between epidemic dynamics, government intervention measures, and resource consumption6,7,8,9. These methods frequently lack the capacity to integrate accurate demand prediction with efficient resource allocation, resulting in inefficiencies that exacerbate shortages and delay critical response efforts. While advancements in emergency logistics have improved certain aspects of supply chain management, significant gaps remain in addressing the multifaceted nature of supply–demand interactions during public health crises.

To address these challenges, this study proposes an integrated framework that combines advanced demand forecasting with multi-objective resource allocation. The framework introduces a novel ICSL deep learning algorithm that incorporates epidemiological characteristics and the effects of government quarantine measures to predict peak demand for emergency medical supplies. This prediction forms the basis for a multi-objective scheduling and allocation model designed to balance urgency, timeliness, and cost. The model is optimized using a particle swarm optimization algorithm, which effectively navigates the trade-offs inherent in resource allocation during emergencies. Validated using data from the Wuhan pandemic response, the proposed approach demonstrates significant improvements in prediction accuracy and allocation efficiency, offering a practical tool for enhancing decision-making in future public health emergencies.

Literature review

Research on emergency resource allocation primarily focuses on three areas: demand prediction, emergency resource allocation, and dynamic scheduling with multi-objective optimization. Each area provides diverse and innovative methodologies to address key challenges in emergency scenarios.

Demand prediction is a fundamental component of emergency resource management, gaining significant attention from scholars. Zhu et al.10 reviewed artificial intelligence-based demand forecasting methods for emergency resources, emphasizing their application in disaster management. Sun et al.11 introduced a fuzzy rough set model for predicting emergency material demand under uncertainty, improving forecasting flexibility. Chen et al. 12 proposed an IACO-BP algorithm for forecasting flood disaster material demand, combining optimization and neural networks. Yang et al.13 developed a forecasting model for emergency material classification based on casualty population data. Sheu J. B.14 introduced a dynamic material demand forecasting model capable of maintaining accuracy despite unstable environments and inaccurate data. Mohammadi R et al.15 suggested a neural network-based method, augmented with a genetic algorithm, for time series forecasting. For emergency decision-making in epidemic contexts, Ekici et al.16 used the SEIR to estimate food demand, while Buyuktahtakn17 proposed an epidemic-logistics mixed-integer planning model. He et al.18 developed a rapid-response model for public health emergencies, integrating time-varying prediction and material allocation mechanisms, emphasizing the importance of mathematical models in forecasting demand during public health crises. This sequence aligns with the decision-making logic needed for managing emergency medical supplies, particularly in the early stages of an epidemic.

However, most of the above studies have been conducted in the static dimension of emergency material demand forecasting, ignoring the urgency of the development of emergency events. Therefore, this thesis addresses the problem of emergency medical material demand forecasting and allocation in the middle and late stages of a major epidemic outbreak, in order to ensure the timely supply of emergency materials, optimize the allocation of resources, improve the efficiency and effectiveness of emergency response, and take into account the timeliness, urgency, and economy of material allocation. Combining the characteristics of infectious diseases and the impact of government isolation measures on the spread of infectious diseases, an end-to-end ICSL deep learning algorithm architecture is proposed so as to predict the maximum demand for emergency medical supplies.

Emergency resource allocation emphasizes optimizing resource efficiency and scientific decision-making. Xu et al.19 developed a mixed-integer programming model incorporating granular optimization and PSO to prioritize demand-based allocation. Guo et al.20 proposed a multi-objective PSO model for port resource allocation, integrating entropy-weighted preferences to determine optimal solutions. Chai et al.21 designed a model for transportation resource allocation based on rescue route estimation. In medical resources, Jiang et al.22 developed a rolling optimization framework combining demand prediction, resource allocation, and parameter updates. Wang et al.23 integrated multi-objective genetic algorithms with A* for disaster scenarios, optimizing paths and trade-offs. Ma Quandang et al.24 applied an AHP-DEA model to maritime emergencies, improving resource allocation under uncertainty. The research summary is shown in Table 1.

The research on dynamic scheduling and multi-objective optimization aims to address the realtime changes in resource demands and multi-dimensional constraint issues25. Hu et al.26 summarized existing optimization models and algorithms, emphasizing the importance of scheduling complexity in dynamic environments. Wang et al.27 proposed a multi-objective optimization model based on an improved differential evolution algorithm, effectively solving the resource allocation problem in multi-period logistics networks. Zhou et al.28 studied multi-objective evolutionary algorithms to optimize dynamic scheduling problems across multiple time periods, especially in scenarios in-volving multiple supply points and resource types, improving scheduling efficiency. Zhang et al.29 focused on marine oil spill emergency scenarios, improving resource allocation timeliness by integrating dynamic optimization models with vehicle routing planning. In real world scenarios, the research further considered balancing response time, cost, and resource utilization efficiency. Huang et al.30 proposed a multi-objective optimization model to optimize response time and allocation costs in marine oil spill events. Cui et al.31 studied a scheduling method based on satellite mission priorities, using genetic algorithms to improve disaster response efficiency. Wang et al.32 designed a cellular genetic algorithm for post-disaster multi-period resource allocation, optimizing the dynamic trade-offs between multiple objectives. Tang et al.33 constructed a multi-objective optimization model for railway rescue, balancing urgency and cost-effectiveness. In addition, dynamic scheduling in uncertain environments is also a key area of research. Wan et al.34 developed a dynamic optimization model to address demand fluctuations, solving the problem of demand uncertainty in material allocation. Hu et al.35 combined deep reinforcement learning and multi-objective optimization to propose an intelligent model for water resource scheduling, further enhancing adaptability in complex situations. The research summary is shown in Table 2.

In conclusion, research across demand prediction, resource allocation, and dynamic scheduling has established a comprehensive framework for emergency resource management. These studies demonstrate adaptability and innovation, particularly in addressing the dynamic changes during emergencies. However, despite the growing body of research on emergency material demand forecasting and resource allocation, several critical gaps remain in the literature. Most existing studies predominantly focus on static forecasting models, which overlook the dynamic nature of emergency events, especially during the middle and late stages of outbreaks. These models often fail to account for real-time changes in demand driven by factors such as the progression of the crisis, government interventions, and regional disparities in supply needs. Furthermore, although some studies integrate machine learning techniques, such as neural networks and deep learning, many of these approaches still struggle with handling uncertainty and providing robust forecasts under variable conditions. Additionally, there is a need for more comprehensive multi-objective optimization models that simultaneously address the urgency, cost, and timeliness of resource allocation, the key factors for improving the overall efficiency and effectiveness of emergency response systems. Future research should focus on developing dynamic, real-time models that can adapt to evolving situations, integrating external variables such as socio-political factors, health infrastructure, and public behavior.

Materials and methods

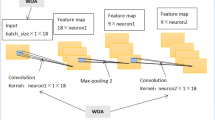

This study proposes an end-to-end ICSL architecture based on the traditional LSTM algorithm. Firstly, Eigenvalue Multi-Scale Decomposition (IVMD) is employed to decompose features, with Principal Component Regression (PCR) used to reduce data dimensionality. Secondly, a two-dimensional CNN architecture is constructed, utilizing convolutional layers, pooling layers, and fully connected layers to extract information from the feature data following IVMD decomposition. Finally, the data is partitioned into a training set (70%) and validation set (30%) at a 7:3 ratio. The iteration count is set to 500 rounds, with the Sparrow Search Algorithm (SSA) employed to optimize the LSTM’s learning rate, regularization terms, and neuron count. The algorithm’s workflow is illustrated in Fig. 1. The final predicted demand results are subsequently fed into the scheduling allocation model.

Feature decomposition based on successive variational mode decomposition

Iterative Variational Mode Decomposition (IVMD) is a signal decomposition method that can decompose a time-domain signal into several Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs). The principle is illustrated in Fig. 2.

IVMD works by iteratively searching for the IMFs and the residual part of the signal until a convergent decomposition result is reached. Each mode can be considered a feature, reflecting different aspects of the original data, and these features can be used individually or in combination as inputs to the LSTM model. The modes separated by IVMD can help remove some minor fluctuations and noise, making it easier for the LSTM to capture the main dynamics in the data. Training the LSTM model on data preprocessed by IVMD allows the model to more effectively learn and predict future values in the time series.

Assuming the original signal \(F\) is decomposed into \(r\) components, IVMD ensures that the decomposed sequences have mode components with limited bandwidth around a central frequency. The goal is to minimize the sum of the estimated bandwidths of all modes, with the constraint that the sum of all modes equals the original signal. The corresponding constrained variational expression is shown in Eq. (2).

In the formula: \(R\) represents the number of modes to be decomposed (a positive integer), \(\left\{ {U_{r} } \right\}\) and \(\left\{ {U_{r} } \right\}\) correspond to the decomposed mode components and their respective central frequencies, and \(\delta (t)\) is the Dirac delta function.

After solving Eq. (2), the Lagrange multiplier operator \(\lambda\) is introduced to transform the constrained variational problem into an unconstrained one, resulting in the augmented Lagrange expression.

In the formula, \(\beta\) is the quadratic penalty factor, which effectively reduces noise interference. The Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM) iterative algorithm, combined with Parseval’s theorem and the Fourier transform, is used to optimize and obtain the mode components and central frequencies. It searches for the saddle points of the augmented Lagrange function. The expressions for the optimal values of \(U_{r}\), \(W_{k}\), and \(\lambda\), obtained through the alternating search, are given in Eq. (4).

In the formula: \(\gamma\) represents the noise tolerance, ensuring the fidelity of the signal decomposition. \(\hat{U}_{r}^{n + 1} \left( \omega \right)\), \(\hat{U}_{i} \left( \omega \right)\), \(\hat{F}\left( \omega \right)\), and \(\hat{\lambda }\left( \omega \right)\) correspond to the Fourier transforms of \(U_{r}^{n + 1} \left( t \right)\), \(U_{r} \left( t \right)\), \(F\left( t \right)\), and \(\lambda \left( t \right)\), respectively.

As shown in Fig. 3, the IVMD decomposition resulted in four Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) and one residual. These can be considered four feature variables, with the residual representing the trend component of the signal, indicating the slow-varying part of the signal. The cumulative number of close contacts, the number of people under medical observation, and suspected cases were also decomposed using IVMD, yielding 40 decomposed features and 10 residuals to be used as feature inputs for the LSTM. This completes the feature decomposition process.

Feature selection based on principal component regression analysis

In the field of machine learning, high-dimensional data often presents challenges such as increased computational complexity and the risk of overfitting. To effectively address these issues, dimensionality reduction techniques are essential tools. Principal Component Regression (PCR) is a widely used method for dimensionality reduction. By projecting input features onto principal components, PCR achieves dimensionality reduction and denoising, thus simplifying the model’s complexity36.

The core principle of PCR is to use a linear transformation to map the original input feature matrix X into a lower-dimensional linear space, composed of the data’s principal components. Principal components are the directions in the data set where variance is maximized, capturing and retaining the primary information in the data. This process not only removes redundancy and noise from the data but also enhances the model’s ability to generalize to new data.

Additionally, an increase in the number of features may lead to the model learning noise and irrelevant details from the training data, potentially ignoring the true underlying mechanisms that generate the data. This can weaken the model’s predictive capability on unseen data. Moreover, a larger number of features can make the model’s structure more complex, not only increasing computational load but also potentially reducing the interpretability of the model, making the decision-making process difficult to understand and verify. Therefore, proper feature processing and dimensionality reduction strategies are crucial for building efficient and reliable predictive models.

As shown in Fig. 4-A, features with eigenvalues greater than 1 were selected for dimensionality reduction via Principal Component Analysis (PCA). The cumulative contribution rate of the top eight features exceeded 91%, indicating the effectiveness of PCA. The cumulative contribution rates are depicted in Fig. 4-B, while the feature importance ranking is illustrated in Fig. 4-C. Eight decomposed features were selected as the input feature set for the LSTM model. This completes the feature dimensionality reduction process.

Scheduling and distribution model is established

Problem description

The evolution of the epidemic has led to issues of untimely and inaccurate sup-ply-demand distribution for emergency medical supplies, resulting in difficulties in timely matching medical resources to needs. Therefore, the primary problem that needs to be addressed is how to reasonably allocate emergency supplies to meet the urgent medical resource demands of various cities and reduce the urgency across different regions. Additionally, the large-scale distribution of supplies must not only consider the urgency level at affected sites but also meet delivery timeliness requirements and reduce the total cost of dispatching emergency supplies.

Model assumptions

Assumption 1: Vehicles travel at constant speeds during transport, unaffected by traffic conditions or other external factors. In practical scheduling, it is challenging to obtain precise, real-time congestion data for every road in advance. This ensures all vehicles establish a fair, comparable time baseline.

Assumption 2: The scheduling process permits time overruns but does not allow exceeding the predetermined quantity of goods to be delivered. The physical capacity of vehicles is a hard constraint; overloading directly results in goods being unable to be loaded or violates traffic safety regulations.

Assumption 3: After delivering goods to the initial demand point, vehicles may only proceed to the next demand point and cannot return to the starting point. This ensures continuity and efficiency in the dispatch route, avoiding additional time and fuel costs incurred by arbitrary backtracking.

Assumption 4: Vehicle status and utilization are disregarded during dispatching, with focus solely on current or future demand allocation. Vehicle maintenance conditions do not influence scheduling decisions. Vehicle maintenance status does not influence scheduling decisions, as it is assumed to have been addressed prior to plan execution. This allows the scheduling model to concentrate on resolving macro-level resource optimization challenges.

Assumption 5: The material demand at all demand points is known before scheduling commences and remains constant throughout the scheduling process. This simplifies the formulation and execution of the scheduling plan.

Assumption 6: All dispatched vehicles possess identical cargo capacities. This eliminates allocation complexities arising from varying vehicle capabilities, thereby simplifying model construction.

Assumption 7: The scheduling process remains unaffected by weather conditions, assuming stable climatic conditions that do not cause delays or damage to transported goods. This assumption helps maintain the accuracy and reliability of the scheduling plan. External environmental factors are excluded as random disturbances, treating the system as a closed, deterministic network.

Notation explanation

The meanings of the various symbols used in the model are explained in Table 3, wherein the parameter \(\mu_{ij}\) represents the demand quantity obtained through the forecasting algorithm.

Model construction

This study constructs an urgency model for emergency medical supplies under conditions of supply and demand imbalance. When the allocation of supplies exceeds demand at a certain point in time, the urgency at that point is alleviated; conversely, if the supply allocation is lower than the demand, the urgency increases. The objective of the study is to allocate emergency medical supplies in a way that minimizes urgency, according to the urgency function shown in Eq. (7).

To minimize the total travel time of the dispatch routes, the model aims to reduce the total travel time from all reserve points to all distribution points. The reason for using total dispatch time as an optimization objective is to facilitate nearby rescue efforts, thereby minimizing total dispatch time and enhancing emergency response efficiency. The objective function for the shortest dispatch time is given in Eq. (8).

In addition to scheduling based on urgency, cost control in the dispatch process is also crucial. It aims to reduce the waste of transportation resources and improve the eco-nomic efficiency of the dispatch plan. The total cost model includes dispatch costs, transportation costs, and penalty costs, as expressed in the total cost function in Eq. (9).

Constraint (10): The cumulative dispatch to each demand point does not exceed the total inventory. Constraint (11): The cumulative allocation weight sums to 1. Constraint (12): After serving a demand point, the dispatch can only move to the next demand point. Constraint (13): After satisfying a demand point, the vehicle cannot return to its original location. Constraint (14): The vehicle speed is controlled within the range of 50 km/h to 60 km/h. Constraint (15): Service time window constraint.

In the model, \(\mu_{ij}\) represents the demand from the \(i\)-th supply point to the \(j\)-th demand point, obtaining the demand at disaster-affected locations through forecasting. \(\omega_{ij}^{l}\) denotes the allocation weight; \(N_{ij}^{l}\) indicates the supply quantity from the \(i\)-th supply point to the \(j\)-th demand point, and \(N_{\max }^{l}\) is the total inventory of the \(l\)-th type of supplies at time \(T\). The variable \(d_{ij}\) represents the distance from the \(i\)-th supply point to the \(j\)-th demand point; \(v_{ij}\) denotes the vehicle speed; \(T_{ij}\) indicates the service time window, \(b_{ij}^{l}\) represents the unit cost of various supplies, \(c_{ij}^{l}\) is the unit transportation cos t, and \(h_{ij}^{l}\) is the penalty coefficient for violating the time window. The final model results after modeling are as follows:

Experiment

Data preprocessing

Data description

This study collected emergency supply dispatch data from 17 cities in Hubei Province between 12 February 2020 and 11 March 2020. The data originates from the official website of the Hubei Provincial Health Commission (https://wjw.hubei.gov.cn) and encompasses the distribution of medical protective supplies by the Material Support Group of the Hubei Provincial COVID-19 Prevention and Control Headquarters. Given the unclear transmission patterns and immense challenges in containment, this study focuses on five critical emergency supplies, as illustrated in Fig. 5-B: medical protective suits, N95 masks, medical surgical masks, isolation gowns, and medical protective face shields. Wuhan adopted a ‘government-led, socially-participatory’ medical supply distribution model, achieving some success in controlling new case numbers. However, as the epidemic progressed, demand for emergency supplies continued to rise. As illustrated in Fig. 5-A, despite some containment of new cases, demand for surgical masks surged dramatically between days 10 and 15. This not only triggered potential supply–demand imbalances but also exposed the model’s inherent flaws: lacking scientific scheduling methods and featuring inefficient resource allocation, it proved incapable of precisely matching material requirements throughout the epidemic’s progression.

As illustrated in Fig. 6, the distribution of medical protective supplies exhibits distinct spatial clustering and gradient radiation characteristics. As the core containment area, Wuhan received peak allocations across all categories of medical protective equipment, including medical protective suits, N95 masks, and medical protective masks. From the perspective of spatial gradient distribution, the density of material allocation diminishes in concentric zones from Wuhan towards surrounding cities such as Xiaogan and Huanggang. The scale of material provision in peripheral cities like Shiyan and Xiangyang is significantly lower than that of the core zone, reflecting the dispatch strategy’s prioritisation of regional epidemic control responses.

As shown in Fig. 7, a Sankey diagram was used to analyze the distribution of emergency supplies, including medical protective clothing, N95 masks, medical surgical masks, isolation gowns, and medical face shields. The diagram clearly illustrates that the demand for mask-related supplies was extremely urgent, with the majority of these re-sources being directed to Wuhan. This indicates the severe epidemic situation in Wuhan. Therefore, it is crucial to rationally plan the dispatch of emergency supplies to effectively address the uneven distribution of resources and alleviate the urgency of supply demand.

Data validation

As illustrated in Fig. 8, outlier checks are performed on the input data. Any detected outliers are corrected using radial basis function interpolation, calculated according to Eq. (16). This process helps mitigate the impact of outliers on the model, thereby enhancing its predictive accuracy and reliability.

Here, \(\alpha_{i}\) denotes the weighting factor for RBF interpolation. \(w\left( \cdot \right)\) represents the radial basis function. \(\left\| {x - x_{i} } \right\|\) is the Euclidean norm, signifying the distance between the interpolation point \(x\) and the interpolation node \(x_{i}\).

Descriptive statistics of the data

As shown in Table 4, statistical analysis revealed that some data points had high variance and standard deviation, indicating a high degree of dispersion. The kurtosis coefficient’s value approaching zero suggests that the data distribution’s kurtosis is similar to a normal distribution; conversely, a greater deviation from zero indicates a less normal distribution. A negative kurtosis coefficient means that the data set is more concentrated, with fewer data points on the sides, while a positive kurtosis indicates more data points on the sides and fewer in the center. When both the skewness and kurtosis coefficients are zero, the data set can be considered to follow a standard normal distribution.

Correlation analysis

This study employs machine learning methods for prediction, which necessitates the use of feature variables. Consequently, it is essential to conduct a correlation analysis on the feature set. The Pearson correlation coefficient formula, as shown in Eq. (17), was utilized to calculate the correlations among the ten feature variables. Subsequently, a heatmap was plotted, as depicted in Fig. 9, to visualize these correlations. This facilitates the identification and adjustment of variables that may interfere with the model during the prediction process, thereby reducing model prediction errors and enhancing accuracy.

A Chord Diagram is a visualization method used to display the relationships be-tween data in a matrix, where node data is arranged radially along the circumference and linked by weighted (varying width) arcs. It is suitable for observing relationships in node or edge datasets. The Pearson correlation results were visualized using a correlation chord diagram. The diagram shows that there is a high positive correlation among the dis-patched materials, a weak correlation with the number of close contacts, recoveries, and infections, and a strong negative correlation among these three indicators. These three indicators also have weaker negative correlations with other variables. The specific details are illustrated in Fig. 9.

Instance verification

This study employs a multi-objective particle swarm optimization algorithm to address the problem. A comparison of the algorithm’s key parameters with those of the MOPSO algorithm is presented in Table 5.

MOPSO algorithm obtained 51 Pareto solutions; as shown in Fig. 10, the Pareto solution surfaces indicate the distribution of various schemes on the surface. Each solution represents a trade-off state in multi-objective optimization, meaning that while satisfying one objective, it also aims to meet or approach the optimal state of other objectives as closely as possible.

Taking the emergency medical supplies dispatch in Wuhan as a case study, and utilizing the dispatch allocation data presented in Table 6 of this paper, nine feasible Pareto optimal dispatch solutions were ultimately identified by filtering out solutions with an urgency level below 70%. Each scheme exhibits pronounced multi-objective trade-offs across the three-dimensional targets of urgency, delivery timeliness, and total cost: Scheme 1 offers the lowest urgency and fastest response speed, enabling rapid mitigation of medical resource shortages but at a higher cost; Scheme 9 centres on optimal cost as its core advantage, with both urgency and timeliness falling within reasonable, controllable ranges. From a decision-making suitability perspective: during the pandemic’s initial phase characterized by rapid case growth and scarce medical resources, safeguarding lives and rapid response took precedence over cost-effectiveness. Solution 1, efficiently bridging resource gaps, was thus best suited. As the epidemic stabilized with declining new cases and easing supply–demand dynamics, cost control and resource utilization efficiency became paramount. Solution 9’s cost advantage rendered it more aligned with long-term scheduling requirements. Option 5 enables relatively swift delivery through moderate cost investment, preventing further escalation in urgency levels. Options 6 and 7 differ only in the proportion of medical protective suits and isolation gowns allocated. They are better suited for the later mid-stage of the outbreak when decision-makers face budgetary constraints and material shortages across Wuhan districts have been reduced to manageable levels. In such circumstances, Option 6 or 7 may be prioritized.

To comprehensively evaluate the overall performance of the model, this study employs Spacing and the Hypervolume (HV) metric for optimization algorithm assessment. Spacing measures the standard deviation of the minimum distances between each solution and all others; a lower Spacing value indicates greater uniformity within the solution set. The Hypervolume (HV) metric represents the volume of the region enclosed by the non-dominated solution set and the reference point within the objective space; a higher HV value signifies superior overall algorithmic performance.

Here, \(\left| P \right|\) denotes the number of solutions in the solution set \(P\). \(d_{i}\) represents the minimum Euclidean distance from the \(i\)-th solution in the set to all other solutions within that set. \(\overline{d}\) denotes the mean of all \(d_{i}\) values. \(\sigma\) denotes the Lebesgue measure, used to quantify volume. \(\upsilon_{i}\) denotes the hypervolume formed by the reference point and the \(i\)-th solution in the solution set.

The performance evaluation of prediction algorithms employs root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), coefficient of determination (R2), and symmetric mean absolute percentage error (SMAPE). The calculation methods for these four metrics are as follows.

Here, \(n\) denotes the total number of samples, \(y_{i}\) represents the true value, \(\hat{y}_{i}\) denotes the predicted value, and \(\overline{y}_{i}\) denotes the mean of all true values across the samples.

The Spacing metric describes the uniformity of solution set distribution by calculating the distance between points on the Pareto front. Smaller spacing values indicate more uniform solution set distribution. The Hypervolume (HV) metric is a commonly used performance evaluation indicator in multi-objective optimization, measuring solution quality by calculating the volume of the region covered by the solution set within the objective space. As illustrated in Fig. 11, the instance validation results indicate that during model solution, the first 250 iterations of all three models exhibited relative instability. Through continuous optimization, convergence was gradually achieved. MOPSO demonstrated superior stability and performance, readily escaping local optima. Following iterative processing, the Spacing metric converged progressively, indicating balanced solution set distributions across each model.

Results

Parameter calibration

This study did not decompose the input feature data, employing a conventional LSTM algorithm for initial prediction to analyze the forecasting performance and error of the raw sequence. Appropriate refinements were made based on these results, and comparative forecasting experiments were conducted. The ICSL model functions as a multi-output predictor with an output dimension of 5. The overall parameter settings for the ICSL framework are detailed in Table 7.

As shown in Fig. 12, the traditional LSTM algorithm can capture the trend features of the sequences to some extent. However, there are significant deviations in some predictions, and the accuracy of the predictions becomes less stable with longer time series. Therefore, further optimization and improvement of the traditional LSTM are needed. To better analyze the model’s capability to predict the demand for emergency supplies and the differences in the performance of various models, this study proposes an ICSL algorithm to optimize the parameter update method, thereby enhancing the prediction ac-curacy.

Additionally, an improved BP neural network algorithm is proposed as a comparative algorithm to further explore the advantages of the ICSL algorithm. The optimization approach for the algorithm involves three steps: 1) Feature Input: The BP neural network uses features derived from IVMD as input; 2) Optimizing Initial Weights and Bias Parameters: Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is employed to optimize initial weights and bias parameters, allowing the network to train from different starting points and avoid local minima; 3) Adjusting Learning Rate: PSO is used to adjust the learning rate to maintain stability near the optimal solution, effectively reducing overall error.

As shown in Fig. 13, the improved BP neural network performs well in the early stages of prediction, but its accuracy becomes less stable with longer sequences. In contrast, the enhanced LSTM deep learning model demonstrates a better ability to learn from long sequences, effectively utilizing the feature information decomposed by IVMD. This results in significantly improved prediction accuracy compared to other deep learning models, allowing for more accurate forecasts of future emergency supply demands. Although prediction accuracy generally decreases as the forecast period extends, the ICSL algorithm consistently provides more precise predictions for emergency supply demand.

Prediction results

Using the ICSL algorithm, this study predicted the demand for emergency medical supplies from March 12 to March 20, 2020, as shown in Table 8. The predicted demand for 17 cities serves as the maximum dispatchable quantity in the scheduling model. This model optimizes the distribution of supplies based on urgency, minimum delivery time, and total cost, ensuring that the allocation falls within a reasonable range.

Discussion

In this study, the traditional LSTM algorithm and the improved BP neural network algorithm were used as comparative algorithms to explore the predictive accuracy of the proposed ICSL algorithm. As shown in Fig. 14, the improved LSTM algorithm significantly reduced prediction errors compared to the traditional LSTM, with an accuracy improvement of 29.37%. It also showed an 8.63% improvement over the improved BP neural network, with relatively stable prediction errors. The improved BP neural network performed better than the traditional LSTM, reducing errors by 20.73%, but its predictions were relatively less stable.

From a temporal perspective, the demand fluctuations for the five categories of supplies exhibit similar cycles, all influenced by external factors such as epidemic control measures. Regarding differences, items with high demand and significant volatility—such as surgical masks and N95 respirators—exhibit greater absolute prediction errors in the algorithms. Nevertheless, the improved algorithms still demonstrate a marked increase in accuracy. Medical protective suits and isolation gowns exhibit phased demand patterns, while medical face shields demonstrate relatively stable demand. This results in differing algorithmic performance when capturing subtle fluctuations in steady demand. Concurrently, distinct algorithmic strengths emerge: IVMD-PSO-BP proves more agile in short-term demand forecasting, ICSL better captures long-cycle fluctuations, whereas traditional LSTM predictions generally lack stability.

This study conducted ablation experiments on the ICSL architecture to validate changes in the model’s overall performance. As shown in Table 9, the experimental results indicate that removing the IVMD module leads to a significant decline in model performance. The RMSE increases from 197, 212.61 to 212, 636.39, the MAE rises from 64, 839.10 to 74, 794.13, the R2 fit decreased by 1%, and the SMAPE rose from 11.20 to 19.77, demonstrating IVMD’s pivotal role in sub-sequence feature extraction. Furthermore, the PCR module’s effectiveness relies on IVMD’s pre-processing results; their combination further reduces RMSE. Without IVMD pre-processing, PCR suffers performance degradation due to feature redundancy. When introduced independently, the CNN module enhances local feature extraction capabilities, reducing RMSE. However, its integration with IVMD and PCR requires optimization, as MAE fluctuates in certain combinations. Notably, when LSTM, IVMD, PCR, and CNN modules are fully integrated, the model achieves optimal performance: RMSE drops to 197, 212.61 and R2 rises to 0.936. Within the ICSL architecture, IVMD handles sequence modal decomposition, PCR performs feature dimension reduction, CNN enhances local pattern recognition, and LSTM captures long-term temporal dependencies, collectively forming an efficient end-to-end prediction model.

Figure 15 presents a stacked bar chart illustrating the runtime distribution across modules within the ICSL model. During each execution cycle, the SSA module accounted for the largest proportion of computational time, whereas modules such as CNN-LSTM, PCR, and IVMD exhibited comparatively lower time consumption. The MOPSO algorithm recorded an average runtime of 30.62 s.

The superior performance of the ICSL algorithm highlights its capacity to adapt to the dynamic and complex nature of emergency medical supply demand during public health crises. These findings suggest that the ICSL algorithm could serve as a reliable tool for optimizing logistics decisions, thereby reducing response times and enhancing the efficiency of supply chains in emergencies. Unlike traditional approaches, such as standard LSTM and BP neural networks, the ICSL algorithm leverages advanced deep learning techniques to achieve superior accuracy. Previous studies have reported notable improvements through the use of hybrid algorithms, yet these methods often lack scalability or fail to ad-dress the unique challenges posed by epidemic demand forecasting. The ICSL approach not only builds on these advancements but also introduces a more comprehensive framework tailored to high-stakes environments, setting a new benchmark in this field.

The enhanced performance of the ICSL algorithm can be attributed to its ability to integrate sequential learning mechanisms with feature optimization techniques. By dynamically adjusting to fluctuations in demand patterns, the model demonstrates robustness against noise and variability, which are common in real-world data. This capability is particularly critical in the context of public health emergencies, where accurate and timely forecasts are essential for effective decision-making. While the ICSL algorithm exhibits promising results, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the model’s performance relies heavily on the quality and quantity of historical data. In scenarios with in-complete or sparse data, its predictive power may diminish. Second, the study does not fully explore the algorithm’s generalizability across different types of emergencies, such as natural disasters or pandemics with distinct demand patterns. Future research should focus on addressing these limitations by integrating real-time data streams and exploring transfer learning approaches to enhance the model’s adaptability. Additionally, collaboration with public health authorities and logistics providers could provide valuable in-sights, leading to more practical and implementable solutions.

This study underscores the practical implications of the ICSL algorithm in real-world scenarios. By enabling more accurate forecasting and efficient logistics planning, the approach has the potential to save lives and resources during public health emergencies. Its application can be extended to other domains, such as disaster relief and humanitarian aid, further broadening its impact. In summary, the ICSL algorithm represents a significant step forward in the field of emergency medical supply forecasting. By addressing existing challenges and setting the stage for future innovation, this study contributes meaningfully to both the academic and practical discourse surrounding public health logistics.

Conclusion

This paper explores the joint decision-making problem of forecasting the demand for emergency medical supplies and the logistics scheduling and allocation in the context of sudden epidemic outbreaks. It proposes an integrated forecasting method based on the ICSL algorithm, which meets the demand forecasting process for emergency supplies in the later stages of the epidemic. Using data from Wuhan and the demand situation, the following conclusions were reached:

-

(1)

To address the problem of high error in traditional static forecasts, this paper proposes an end-to-end ICSL deep learning algorithm architecture to predict the maxi-mum demand for emergency medical supplies. Compared to traditional LSTM, this algorithm significantly improves accuracy, reducing prediction error by 29.37% and outperforming the improved BP neural network by 8.63%. The prediction error is relatively stable. The improved BP neural network shows less error compared to traditional LSTM, with an accuracy improvement of 20.73%, although the prediction stability is relatively lower.

-

(2)

To ensure the timely supply of emergency supplies and optimize resource allocation, enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of emergency response, this paper develops a multi-objective scheduling and allocation model considering urgency, scheduling time, and scheduling cost, and designs a multi-objective particle swarm optimization algorithm to solve it. The designed model takes into account the timeliness, urgency, and economic aspects of resource allocation.

-

(3)

Future research may further consider the possibility of secondary infections in the population. Additionally, due to potential deviations between forecasted and actual values caused by random disturbances, a robust optimization model can be established for decision-making in emergency response plans.

Data availability

All data utilized in this study were sourced from publicly available epidemic-related material dispatch data published on the Wuhan Municipal Government official website (accessible via the corresponding public section of the website). Should datasets used or analyzed during the research require access, they may be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to compliance with the licensing restrictions of the original public data source (such as non-commercial research use).

References

Ivanov, D. Predicting the impacts of epidemic outbreaks on global supply chains: A simulation-based analysis on the coronavirus outbreak (COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2) case. Trans. Res. Part E: Logistics Trans. Rev. 136, 101922–101936. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2020.101922 (2020).

Queiroz, M. M. et al. Impacts of epidemic outbreaks on supply chains: Mapping a research agenda amid the COVID-19 pandemic through a structured literature review. Ann. Oper. Res. 319(1), 1159–1196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-020-03685-7 (2022).

Alzamili, Z., Danach, K. & Frikha, M. Revolutionizing COVID-19 diagnosis: Advancements in chest X-ray analysis through customized convolutional neural networks and image fusion data augmentation. BIO Web Conf. 97, 00014. https://doi.org/10.1051/bioconf/20249700014 (2024).

Govindan, K., Mina, H. & Alavi, B. A decision support system for demand management in healthcare supply chains considering the epidemic outbreaks: A case study of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Trans. Res. Part E: Logistics Trans. Rev. 138, 101967–101981. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2020.101967 (2020).

Moosavi, J., Fathollahi-Fard, A. M. & Dulebenets, M. A. Supply chain disruption during the COVID-19 pandemic: Recognizing potential disruption management strategies. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 75, 102983–103002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.102983 (2022).

Paul, S. K. & Chowdhury, P. A production recovery plan in manufacturing supply chains for a high-demand item during COVID-19. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 51(2), 104–125. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPDLM-04-2020-0127 (2021).

Dolgui, A., Ivanov, D. & Sokolov, B. Reconfigurable supply chain: The X-network. Int. J. Prod. Res. 58(13), 4138–4163. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2020.1774679 (2020).

AlZamili, Z., Danach, K. M. & Frikha, M. Deep learning-based patch-wise illumination estimation for enhanced multi-exposure fusion. IEEE Access 11, 120642–120653. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2023.3328579 (2023).

Dasaklis, T. K., Pappis, C. P. & Rachaniotis, N. P. Epidemics control and logistics operations: A review. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 139(2), 393–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2012.05.023 (2012).

Zhu, X., Zhang, G. & Sun, B. A comprehensive literature review of the demand forecasting methods of emergency resources from the perspective of artificial intelligence. Nat. Hazards 97(1), 65–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-019-03626-z (2019).

Sun, B., Ma, W. & Zhao, H. A fuzzy rough set approach to emergency material demand prediction over two universes. Appl. Math. Model. 37(10–11), 7062–7070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apm.2013.02.008 (2013).

Chen, F., Chen, J. & Liu, J. Forecast of flood disaster emergency material demand based on IACO-BP algorithm. Neural Comput. Appl. 34(5), 3537–3549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00521-021-05883-1 (2022).

Yang, J., Zhang, K., Hou, H. & Li, N. Forecasting demand for emergency material classification based on casualty population. Systems. 13(6), 478–498. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems13060478 (2025).

Sheu, J. B. Dynamic relief-demand management for emergency logistics operations under large-scale disasters. Trans. Res. Part E Logistics Trans. Rev. 46(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2009.07.005 (2010).

Mohammadi, R., Ghomi, S. M. & Zeinali, F. A new hybrid evolutionary based Rbf networks method for forecasting time series. Eng. Appl. Artificial Intell. 36(Nov), 204–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2014.07.022 (2014).

Ekici, A., Keskinocak, P. & Swann, J. L. Modeling influenza pandemic and planning food distribution. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 16(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1287/msom.2013.0460 (2014).

Büyüktahtakn, İE., Des-Bordes, E. & Kıbış, E. Y. A new epidemics–logistics model: Insights into controlling the Ebola virus disease in West Africa. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 265(3), 1046–1063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2017.08.037 (2018).

He, Y. X. & Liu, N. Methodology of emergency medical logistics for public health emergencies. Trans. Res. Part E: Logistics Trans. Rev. 79, 178–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2015.04.007 (2015).

Xu, X. F. et al. Flexible districting policy for the multiperiod emergency resource allocation problem with demand priority. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybernetics: Syst. 54, 6977–6988. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSMC.2024.3443116 (2024).

Guo, J. Q. et al. Optimal allocation model of port emergency resources based on the improved multi-objective particle swarm algorithm and TOPSIS method. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 209, 117214–117224. https://doi.org/10.1109/TSMC.2024.3443116 (2024).

Chai, G. et al. Optimized traffic emergency resource scheduling using time varying rescue route travel time. Neurocomputing 275, 1567–1575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2017.09.086 (2018).

Jiang, J. H. et al. Data-driven collaborative healthcare resource allocation in pandemics. Trans. Res. Part E: Logistics Trans. Rev. 192, 103828–103852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2024.103828 (2024).

Wang, F. Y. et al. Multiobjective emergency resource allocation under the natural disaster chain with path planning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19(13), 7876–7895. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137876 (2022).

Ma, Q. D. et al. A method for optimizing maritime emergency resource allocation in inland waterways. Ocean Eng. 289, 116224–116236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2023.116224 (2023).

Liu, H. Q. et al. Coordinated planning model for multi-regional ammonia industries leveraging hydrogen supply chain and power grid integration: A case study of Shandong. Appl. Energy 377, 124456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.124456 (2025).

Hu, H. et al. Emergency material scheduling optimization model and algorithms: A review. J. Traffic Trans. Eng. (English edition) 6(5), 441–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtte.2019.07.001 (2019).

Wang, Y. D., Shi, Q. & Hu, Q. W. Dynamic multi-objective optimization for multi-period emergency logistics network. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 37(6), 8471–8481. https://doi.org/10.3233/JIFS-191130 (2019).

Zhou, Y. W. et al. A multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for multi-period dynamic emergency resource scheduling problems. Trans. Res. Part E: Logistics Trans. Rev. 99, 77–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2016.12.011 (2017).

Zhang, L. Y., Lu, J. & Yang, Z. L. Dynamic optimization of emergency resource scheduling in a large-scale maritime oil spill accident. Comput. Ind. Eng. 152, 107028–107047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cie.2020.107028 (2021).

Huang, X. L. et al. Dynamic scheduling optimization of marine oil spill emergency resource. J. Coast. Researc 107(SI), 437–442. https://doi.org/10.2112/JCR-SI107-097.1 (2020).

Cui, J. T. & Zhang, X. Application of a multi-satellite dynamic mission scheduling model based on mission priority in emergency response. Sensors. 19(6), 1430–1451. https://doi.org/10.3390/s19061430 (2019).

Wang, F. Y. et al. Emergency resource allocation for multi-period post-disaster using multi-objective cellular genetic algorithm. IEEE access. 8, 82255–82265. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2991865 (2020).

Tang, Z. P. & Sun, J. P. Multi objective optimization of railway emergency rescue resource allocation and decision. Int. J. Syst. Assurance Eng. Manage. 9(3), 696–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13198-017-0648-y (2018).

Wan, M. G., Ye, C. M. & Peng, D. J. Multi-period dynamic multi-objective emergency material distribution model under uncertain demand. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 117, 105530–105556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105530 (2023).

Hu, C. Y. et al. Multi-objective deep reinforcement learning for emergency scheduling in a water distribution network. Memetic Computing. 14(2), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12293-022-00366-9 (2022).

Chen, N. et al. Motion and appearance decoupling representation for event cameras. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 34, 5964–5977. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2025.3607632 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Guangxi Science and Technology Base and Talent Project for Guangxi Science and Technology Plan Project: Construction of Guangxi Transportation New Technology Transfer Center Platform (No. Guike AD23026029);Innovation Driven Development Special Project for Guangxi Science and Technology Plan Project: Construction of China-ASEAN International Joint Laboratory for Comprehensive Transportation (Phase I) (No. Guike AA21077011)..

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.P. and S.Z. were responsible for the conceptualization and supervision of the study and drafted the primary manuscript text. They also led the overall planning and direction of the project. B.L. was responsible for data curation, formal analysis, and validation, as well as leading the design and implementation of the methodology. He also provided technical support for project administration. H.X. and K.F. assisted with data curation and contributed to project administration by supporting the coordination of the research team’s daily activities. L.N. was responsible for the investigation and contributed to the design of certain aspects of the methodology. He also analyzed and discussed key experiments conducted during the study. Y.Pa. and G.G. prepared the figures in the manuscript and assisted with data curation and analysis. They also participated in the initial drafting and refinement of the manuscript. X.W. and D.Z. assisted with drafting and editing the manuscript and contributed to the discussion and refinement of the methodology. They also supported the validation of the research findings. C.B. and D.Z. were involved in software development for the study and assisted with project administration, providing technical tools and support for analytical platforms. All authors reviewed the final manuscript and approved it for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pang, Y., Zhou, S., Lou, B. et al. A multi-objective optimization framework integrating ICSL deep learning for forecasting and scheduling emergency medical supply demand in public health emergencies. Sci Rep 16, 4199 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34300-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34300-z