Abstract

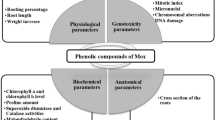

Methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) is a chemical compound that exerts an alkylating effect on DNA and proteins. Alchemilla vulgaris L. is a medicinal plant known for its rich bioactive composition and pharmacological potential. This study investigated the cytoprotective activity of A. vulgaris extract (AVE) against MMS-induced toxicity in Allium cepa L. bulbs. For this purpose, A. cepa bulbs were divided into groups (n = 50 per group) and treated with tap water (control), AVE (250 mg/L and 500 mg/L), MMS (4000 µM), or combinations of MMS (4000 µM) with AVE (250 mg/L and 500 mg/L) for 72 h. A comprehensive analysis was conducted to ascertain the impact of the solutions on physiological parameters (rooting percentage, root elongation, and weight gain), cytogenetic endpoints (mitotic index, micronucleus formation, and chromosomal aberrations), biochemical markers (malondialdehyde, superoxide dismutase, catalase, chlorophyll a and b), and meristematic tissue integrity. Molecular docking was employed to elucidate the potential interactions between MMS and key cellular targets, including and tubulins, topoisomerases, glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase and protochlorophyllide reductase. A targeted LC–MS/MS analysis was carried out to determine the main phenolic compounds that may underlie the observed biological effects. The analysis showed that the extract predominantly contained rosmarinic acid, catechin, p-coumaric acid, rutin, and gentisic acid. MMS administration resulted in a decline in rooting percentage, weight gain, root elongation, mitotic index and chlorophyll content. MMS exposure increased frequencies of micronuclei, chromosomal aberrations, malondialdehyde levels, and the activities of superoxide dismutase and catalase. Meristematic tissue damage in the MMS group included epidermal cell deformation, flattened nuclei, cortical damage, and thickened cortex cell walls. Co-application of AVE significantly alleviated MMS-induced toxicity in a dose-dependent manner. These findings suggest that AVE exhibits notable antigenotoxic and antioxidant properties. However, further in vivo studies are needed to support its potential use in therapeutic or dietary contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Herbal extracts, which are considered a gift of nature to humanity, have been utilized as essential components in the treatment of diseases since ancient civilizations. The most significant advantages of natural extracts are attributable to their composition, which consists of a multitude of active components. Consequently, they are able to exert their effects synergistically on a plethora of pharmacological targets1. Products from the genus Alchemilla, a member of the Rosaceae family, are recognized for their diverse biological activities. These include antioxidant, antiviral, antibacterial and antiproliferative effects2. Alchemilla vulgaris L. (Lady’s mantle/lion’s foot) is common in Europe, North America, and Asia. It has been used in traditional medicine to treat wounds, ulcers, eczema, digestive problems, and gynecological disorders2,3. As a perennial herbaceous species, it is also famous for its antimicrobial, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties4. A. vulgaris has a rich phytochemical profile, including flavonoids, phenolic acids, triterpenes, anthocyanins, tannins, and coumarins. These compounds contribute to its pharmacological properties5. For this reason, AVE has gained attention in toxicological research, particularly as a potential curative agent⁶.

Chemically induced mutagenesis and carcinogenesis often begin with the formation of DNA adducts7. This is a key mechanism of methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) toxicity. MMS is an effective model chemical, capable of inducing mutation formation within the DNA structure through nucleotide alkylation8. Upon interaction with genetic material, MMS transfers methyl groups to DNA bases. Alkylation predominantly occurs at the O6 position of guanine, while N7 of guanine and N3 of adenine are also frequent targets9. Therefore, MMS leads to a deterioration in the structure and integrity of the helix8. This outcome is attributable to the formation of methylated DNA adducts, which are the result of DNA-methyl covalent interactions. In addition to altering the structural integrity of the DNA helix, the adducts cause nucleotide mismatches during DNA replication, leading to replication and transcription defects9. Additionally, MMS methylation can cause double-strand breaks10. Moreover, it has been documented that MMS increases membrane permeability and exerts a cytotoxic effect11. In addition to the formation of DNA adducts, MMS has the ability to form protein adducts. These arise through methylation of valine and histidine residues, contributing to its classification as a super clastogen10. MMS has the potential to contaminate ecosystems, particularly through industrial effluents associated with the chemical and pharmaceutical sectors or through the leakage of laboratory residues into the environment.

The phytotest system uses the sensitivity of plants to chemicals that cause phenotypic and genetic changes. This system holds particular significance in the realm of contemporary toxicity assessments due to its numerous merits, including expediency, ease of execution, and reproducibility, as well as the dependability of the outcomes. Furthermore, it is economically efficient, does not necessitate the utilization of an abundance of specialized equipment, and ensures objectivity in the data obtained12. The Allium assay constitutes a phytotest system that was first introduced by Levan. It has subsequently been employed to demonstrate not only the mutagenic, cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of toxicants but also the protective potential of plant compounds13. Allium cepa L., the subject of the assay, is a standard eukaryotic model in toxicity research due to its similarities to mammalian cells. Its root cells share key features with animal cells14. These similarities include the nucleus surrounded by karyotheca, the presence of linear chromosomes, the DNA origin of the genetic material, and cell division by mitosis15. The test correlates with bacterial, algal, fish and human cell culture assays. It provides various cytogenic and genotoxic data including growth disorders, mitotic abnormalities, mitotic index (MI), chromosomal aberrations (CAs), and micronucleus (MN) formation16. In addition to the aforementioned assays, in the field of bioinformatics, molecular docking has emerged as a prevalent technique in elucidating the mechanisms of genotoxic action in recent years17. It helps explain how small molecules interact with target proteins by predicting binding modes and energies18.

Despite the existence of scientific reports on the protective potential of various plant products in relation to MMS toxicity, to the best of our knowledge, no research on AVE was identified among these studies. The present study therefore aims to be the first comprehensive study to demonstrate the protective effect of AVE against the physiological, biochemical and meristematic damages induced by MMS in A. cepa. In addition, CAs, MN frequency, and MI were evaluated to investigate the genotoxic potential of the test chemicals. Molecular docking analysis was carried out to predict some of the underlying causes of MMS toxicity. Moreover, the phenolic composition of AVE contributing to its ameliorative potential was investigated.

Materials and methods

Preparation of materials and test solutions

A. cepa var. aggregatum (shallot) bulbs were obtained from a local market in Giresun, Türkiye, and in the laboratory, bulbs that were as close as possible in weight (13.4–13.6 g) and size were selected for the experiments. The bulbs were then washed under running water. Following this, the roots were removed. The MMS solution (4000 µM) was prepared using a chemical with a CAS number of 66–27-3 (Merck). AVE was prepared utilizing plant material obtained from a local herbalist. The identification of the plant materials was carried out and confirmed by Prof. Dr. Zafer Türkmen from the Botany Division of the Department of Biology at Giresun University. Specimens of A. vulgaris and A. cepa were subsequently archived in the herbarium of the same department, with voucher numbers AVU-2025 and ACA-01–2025, respectively. For the extraction process, 5 g of the aerial parts of A. vulgaris were ground and mixed with 100 mL of 70% ethanol. The mixture was stirred continuously for 48 h using a mechanical stirrer at room temperature. Following extraction, it was filtered through Whatman No. 4 filter paper, and the resulting filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure using a rotary evaporator (Heidolph Hei-VAP ML, Germany). The final concentrations of AVE (250 mg/L and 500 mg/L) were prepared with distilled water. The MMS dose was selected based on the findings reported by Pehlivan et al.19, where 4000 µM was shown to induce significant genotoxic effects in A. cepa root cells. The concentration of 500 mg/L was selected as the highest soluble dose of A. vulgaris extract, and 250 mg/L was chosen as half of this concentration. In the preliminary tests, both doses were examined to determine whether they had any adverse effects on A. cepa.

Experimental organization

The bulbs were divided into 6 groups of 50 individuals each, which were then subjected to various treatments. These comprised tap water, 250 mg/L AVE, 500 mg/L AVE, and 4000 µM MMS, 4000 µM MMS + 250 mg/L AVE and 4000 µM MMS + 500 mg/L AVE (Table 1). A. cepa bulbs were placed in glass tubes filled with the respective solutions, which were refreshed on a daily basis. The treatments were conducted in an incubator under complete darkness at 23 ± 2 °C and approximately 60% relative humidity to prevent tissue desiccation. During the application process, the bulbs were maintained in glass tubes filled with the treatment solutions in a way that permitted the growth of new roots from the basal plate. At the conclusion of the 72 h treatment period, root samples were collected. The leaf samples for the chlorophyll (chl) analysis were taken at the end of the 144th hour of the treatments.

Alterations in physiological metrics

The calculation of the rooting percentage of MMS- and AVE-treated bulbs (n = 50) was conducted in accordance with the Eq. 120. Rooting percentage was calculated using 50 biological replicates (bulbs), with each bulb considered as one biological replicate (n = 50).

(RP: Rooting percentage, NRB: Number of rooted bulbs, TNB: Total number of bulbs).

The measurement of root elongation was conducted by determining the distance from the origin to the tip of the adventitious roots using a ruler (n = 10). Root elongation measurements were performed on 10 bulbs as biological replicates. (n = 10).

The bulbs weighed before starting the experiments (initial weight (g)) were weighed once more after the completion of the treatment process with the solutions (final weight (g)). The difference between these two weights was then calculated to determine the weight gain (g). Initial and final weight measurements were recorded from 10 bulbs, serving as biological replicates (n = 10).

Analysis of genotoxicity parameters

The harvested root tips were washed and gently dried in order to remove any chemical residues. The same extraction and preparation method was employed for the microscopic documentation of MI, MN and CAs21. Following a preliminary rinse with distilled water, 1.5 cm segments of the harvested roots were immersed in Clarke’s fixative and then rinsed again with distilled water. Clarke’s fixative used in the fixation process was freshly prepared by mixing 3 parts of ethanol with 1 part of glacial acetic acid. In order to perform hydrolysis subsequent to fixation, the root pieces were placed into 1 N HCl heated and maintained at 60 °C for 13 min. The root samples were washed with distilled water in order to ensure the complete removal of HCl. The root samples were subjected to staining with acetocarmine (1%) for a period of 14 h, after which they were prepared for microscopic examination by means of the squash preparation technique. For the final treatment, a drop of 45% acetic acid was used. Subsequently, random locations on the slides were imaged at a magnification of × 500 under a research microscope (IRMECO IM-450 TI). For genotoxicity analysis, 10 biological replicates per group were prepared as microscope slides (n = 10). For MI determination, 10,000 cells were examined per group (technical replicates), and for MN and CAs analyses, 1,000 cells per group were evaluated. The MN determination was conducted in accordance with the guidelines set out by Fenech et al.22. The following equation was used to calculate MI (Eq. 2).

(NCIM: Number of cells in mitosis, TCC: Total cell count).

Molecular docking study and visualization

Molecular docking was performed to analyze potential interactions of MMS with histone, tubulins (alpha-1B chain and tubulin beta chain), DNA topoisomerases I and II, glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase and protochlorophyllide reductase. The 3D structure of tubulin (PDB ID: 6RZB)23, the 3D structure of DNA topoisomerases (PDB ID:1K4T and PDB ID:5GWK)24,25, the 3D structure of glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase (PDB ID:2ZSL)26 and the 3D structure of protochlorophyllide reductase (PDB ID:6R48)27 were obtained from the protein data bank. The 3D structure of the MMS molecule (PubChem CID: 4156) was obtained from the PubChem database and prepared by defining active sites, removing water molecules and ligands, and adding polar hydrogen atoms. Energy minimization of proteins was conducted utilizing Gromos 43B1 with the Swiss-PdbViewer28 (v.4.1.0) software. Energy minimization of the 3D structure of MMS was achieved through the use of the uff-force field with the Open Babel v.2.4.0 software29. Kollman charges and Gasteiger charges were given to the receptor molecules and MMS molecule, respectively. Docking simulations were carried out using AutoDock 4.2.630 software based on the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm. The docking parameters were set as follows: 10 genetic algorithm runs, a population size of 150, maximum number of generations 27,000, and a maximum of 2,500,000 energy evaluations. The mutation and crossover rates were set to 0.02 and 0.8, respectively. Grid boxes were defined to cover the active binding regions of each target protein, with a spacing of 0.375 Å. For tubulin alpha, the grid was centered at (x:292.128, y:161.910, z:254.123) with dimensions of approximately 26.6 × 24.0 × 22.5 Å. For tubulin beta, the grid center was set at (x:296.355, y:168.667, z:286.286), with a box size of 27.0 × 37.1 × 37.5 Å. In the case of DNA topoisomerase I (PDB ID: 1K4T), the center was located at (x:15.538, y:7.377, z:23.476), with dimensions of 33.0 × 27.0 × 25.5 Å, and for topoisomerase II (PDB ID: 5GWK), the grid was set at (x:16.052, y:-45.107, z:-54.680), covering an area of 42.8 × 25.5 × 27.0 Å. Lastly, for glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase (PDB ID: 2ZSL), the grid was centered at (x:-1.025, y:31.101, z:31.216), spanning approximately 18.8 × 20.6 × 34.5 Å. All grid boxes were carefully positioned to encompass the active or functionally relevant binding regions of each protein structure. The Biovia Discovery Studio 2020 Client was employed to perform the analysis and the visualization. Molecular docking analyses did not involve biological replicates but were performed as computational technical replicates to validate binding interactions.

Alterations in biochemical metrics

The determination of antioxidant enzymes, superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) activities, and malondialdehyde (MDA) content was conducted in the roots of samples that had been treated with tap water, MMS, AVE and a mixture of MMS and AVE. In the case of leaf samples, the objective was to determine chl a and chl b content. The methodology outlined by Zou et al.31 was used to determine the activity of the SOD and CAT. Following this protocol, 5 mL of monosodium phosphate buffer (50 mM and pH 7.8) was used to mechanically homogenize 0.5 g of fresh root sample. The enzyme-containing supernatant was used for further analyses after the homogenate was centrifuged for 25 min at 10,000 rpm. The process was completed and the resulting supernatant was stored at a temperature of + 4 °C.

The reaction solution was prepared by mixing 1.5 mL of 0.05 M monosodium phosphate buffer, 0.3 mL of 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.3 mL of 750 μM nitroblue tetrazolium chloride, 0.3 mL of 130 mM methionine, 0.3 mL of 20 μM riboflavin, 0.28 mL of distilled water and 0.01 mL of 4% insoluble polyvinylpyrrolidone to measure the activity of the SOD enzyme. After adding 0.01 mL of enzyme-containing extract, the mixture was placed in a tube and exposed to two 15-W fluorescent lights for 12 min. Following the termination of the reaction by removing the tube from the light to a dark place, a spectrometric measurement was performed at 560 nm. The quantity of enzyme needed to provide a 50% inhibition of NBT photoreduction was known as one unit of SOD activity, and it was finally represented as U/mg fresh weight (n = 10)32.

The measurement of CAT activity was conducted using a spectrophotometric approach at a wavelength of 240 nm. This method involved the consideration of the enzymatic degradation of hydrogen peroxide. The reaction mixture, the absorbance of which was subsequently measured, was obtained by the addition of 0.2 mL of enzyme-containing extract to 1.0 mL of distilled water, 0.3 mL of 0.1 M hydrogen peroxide, and 1.5 mL of 200 mM monosodium phosphate buffer. The activity was finally represented as OD240 nm min/g fresh weight (n = 10)33.

MDA level, a marker for lipid peroxidation, was measured using the approach suggested by Unyayar et al.34. To this end, 0.5 g of recently harvested root tips were mechanically ground in 1 mL of 5% trichloroacetic acid. After adding equal amounts of supernatant, thiobarbituric acid (5%) and trichloroacetic acid (20%), the mixture was left to react for 25 min at 98 °C. The tube was immersed in an ice bath to stop the reaction. 10,000 g centrifugation for 5 min was carried out to obtain the supernatant layer of the mixture. A spectrometric measurement was performed at 532 nm (n = 10). The MDA level was finally represented as µM/g fresh weight.

The method suggested by Kaydan et al.35 was modified to determine the chl a and chl b content of the leaves. A quantity of 0.3 g of leaf segment was expeditiously ground up in an experimental tube containing 7.5 mL of 100% acetone. The tubes were stored in the refrigerator for 7 days in the dark to allow sufficient time for pigment diffusion. This incubation period was based on our preliminary observations, which showed that 7 days was adequate for complete pigment extraction without visible degradation. The solution was filtered to remove whitened leaf fragments. The pigment extract was diluted with 7.5 mL of 100% acetone and centrifuged at 3000 rpm. The measurement of the absorbances of the supernatant was conducted using a spectrophotometer, with the readings obtained at 645 nm and 663 nm (n = 10). The equation formulated by Witham et al.36 was implemented to calculate the pigment levels.

Biochemical assays were conducted on 10 biological replicates for each treatment group. Each assay involved technical replicates in spectrophotometric measurements.

Alterations in meristematic tissue organization

Cross-sections of the adventitious roots were utilized to monitor the alterations in the meristematic tissue. After dropping 1 mL of 1% methylene blue, from each bulb (n = 10), 10 root cross-sections were obtained, resulting in a total of 100 sections per group. Cross-sections were photographed under a microscope (IM-450 TI). Since each bulb produced multiple roots, representative sections from different root regions were collected to ensure adequate sampling. The frequency of observed tissue damage was assessed across these 100 sections per group and classified as undamaged (UD) for 0 to 5 damaged sections, slightly damaged (●) for 6 to 25 damaged sections, moderately damaged (●●) for 26 to 50 damaged sections, and severely damaged (●●●) for 51 or more damaged Sects. 37.

Determination of phenolics in AVE

The analysis of phenolic components was conducted at Hitit University Scientific, Technical Application and Research Centre (HUBTUAM). The phenolic constituents of AVE ascertained through the implementation of the LC–MS/MS technique. The extraction of 1 g of AVE was performed using a 4:1 ratio of methanol and dichloromethane. The extract was subsequently filtered through a 0.45 µm syringe filter, after which the filtrate was utilized for analysis. Using an ODS Hypersil 4.6*250 mm column and an LC–MS/MS apparatus (Thermo Scientific), the analysis was carried out for 34 min at 30 °C with a flow rate of 0.7 mL/minute38,39. Phenolic content analysis was performed using a single biological replicate of powdered material, with technical replicates ensured by multiple injections during LC–MS/MS analysis.

The LC–MS/MS analysis was performed using a targeted approach, focusing on selected phenolic standards with known antioxidant and genoprotective properties. Quantification was based on external calibration curves of authentic reference compounds, and not on total ion chromatogram peak-area normalization.

Statistical data analysis

The results of the study were analyzed using the statistical analysis application IBM SPSS Statistics 23. The findings were shown as means with standard deviations (mean ± SD). One-way ANOVA and post hoc multiple comparisons (Duncan tests) were used to examine the statistical significance of the data between each group, with a p-value of less than 0.05 (p < 0.05).

Results and discussion

In preliminary tests, both AVE concentrations (250 and 500 mg/L) were assessed to ensure their suitability for application, without interpreting any biological outcomes. The effects of MMS and AVE on physiological events in A. cepa bulbs were evaluated in terms of rooting percentage, root elongation and weight gain. It was determined that the AVE 1 and AVE 2 groups exhibited 100% rooting, a finding similar to that of the control group. Furthermore, the root length and weight gain values of these groups did not differ significantly from the control values (p > 0.05) (Table 2). The findings indicated that the selected AVE doses were devoid of any adverse effects on A. cepa. Conversely, rooting percentage exhibited a decline of up to 35% in the MMS-treated group (Table 2). Furthermore, the MMS group demonstrated a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in root elongation and weight gain, with values of 77.1% and 68.2%, respectively, in comparison to the control group. The MMSAVE 1 and MMSAVE 2 groups, which received a mixture of MMS and AVE, exhibited rooting rates of 44% and 57%, respectively. In both the MMSAVE 1 and MMSAVE 2 groups, there was an increase in root elongation and weight gain values, as well as an increase in rooting percentage, in comparison with the MMS group. Additionally, the values for root elongation and weight gain were found to be higher in the MMSAVE 2 group than in the MMSAVE 1 group. Indeed, the root elongation and weight gain of the MMSAVE 2 group were 2.8 and 2.3 times that of the MMS group, respectively (Table 2). In addition, all physiological parameters showed statistically significant differences between the MMSAVE 1 and MMSAVE 2 groups (p < 0.05).

The findings of the present study on MMS-induced physiological damage are consistent with those of Pehlivan et al.19, who demonstrated that MMS constrained rooting percentage, root elongation, and weight gain in A. cepa. In addition, Shah et al.40 demonstrated that ethyl methyl sulfonate, another alkylating agent, delayed both germination and seedling development in cucumber. Furthermore, ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS), another alkylating compound, was found to reduce seedling growth of Capsicum annuum by analyzing the length of taproot and the longest lateral root length as well as the number of lateral root41. According to Türkoğlu et al.42, alkylating agents are mutagenic materials, with the capacity to induce DNA damage and chromosomal abnormalities, in addition to epigenetic changes. As posited by Hu et al.43, the induction of DNA damage leads to the inhibition of growth and the occurrence of developmental defects in plants. Furthermore, Pehlivan et al.19 proposed that alkylating agent-related growth inhibition may be attributable to defects in hormones and enzyme activities, as well as to deterioration in ATP biosynthesis. Since oxidative imbalance may lead to suppression of normal growth of a plant44, MMS-induced growth retardation may also be a consequence of reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation. Moreover, numerous studies have demonstrated that the decline in growth is concurrent with a decrease in mitotic activity16. It is therefore important to consider the possibility that MMS-induced growth retardation may be linked to a reduction in cell division.

Our findings suggest that AVE can alleviate MMS-induced growth impairment to a certain extent. To our knowledge, no studies have investigated how AVE protects plant cells from MMS-induced toxicity. However, because AVE contains more than 20 phenolic compounds, Jurić et al.6 demonstrated its preventive potential against oxidative stress-induced diseases in rats. Hamad et al.45 demonstrated the protective power and free radical scavenging potential of AVE against DNA, protein and lipid oxidation. In addition, the ameliorative capacity of natural extracts of plants such as Cymbopogon flexuosus10, Erythrina velutina46 and Carica papaya47 against MMS-induced toxicity has been previously demonstrated in various organisms, including A. cepa. For instance, similar to our study, Silva et al.46 showed that plant-derived extracts have potential to limit MMS-induced growth inhibition in A. cepa. The impact of AVE in the suppression of MMS-induced growth inhibition may have been facilitated by the alleviation of oxidative stress, the modulation of enzyme activities, and the enhancement of cell proliferation through the restoration of mechanisms involved in mitosis.

The present study examined the data on MI, MN and CAs in order to monitor the attenuating effect of AVE on MMS-associated genotoxicity in A. cepa root cells (Table 3). These metrics are short-term indicators. They provide evidence for how agents disturb cell kinetics and chromosomal damage48. The observation that a negligible number of CAs were detected in these three groups may be attributable to spontaneous DNA alterations. In addition, it was determined that there was no remarkable difference between the means of MI, MN and CAs results obtained from the control, AVE 1 and AVE 2 groups (p > 0.05). Conversely, the mean value of MI was lower and the mean values of MN and CAs were higher in the MMS group than those of the control group. The differences between the means of the MMS and the control groups were statistically significant (p < 0.05). The weight gain, root elongation, and rooting restriction that accompanied the decrease in MI demonstrated that MMS slowed growth via lowering cell proliferation (Table 2 and Table 3). The findings of this study on the genotoxic effects of MMS are in agreement with the study of Pehlivan et al.19, which revealed that MMS decreased MI and increased the frequency of MN and CAs in A. cepa organism. In addition, Chacón et al.48 demonstrated the MMS-provoked cytotoxicity in Caiman latirostris through a gradual decrease in MI in response to increasing MMS concentration. Furthermore, El-Adl et al.49 demonstrated that ethyl methane sulfonate reduced cell proliferation in somatic cells of A. cepa, which in turn resulted in lower MI values.

MI is an indicator of cell proliferation and the sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility of MI make it a frequently employed biomarker of cytotoxicity50. Graña51 states that a considerable reduction in MI indicates the possibility of genotoxicity, and that an effect is deemed sub-lethal when the mitotic index drops below 50% of the control and lethal when the inhibition drops below 22%. The MI value of the MMS group showed a 51.4% decrease compared to the control group. Therefore, it can be assumed that MMS is lethal for A. cepa root cells. MI decrease may be caused by spindle dysregulation, G2 phase arrest, DNA double chain breakage, suppression of DNA synthesis, or cell death48,51,52. Bianchi et al.53 suggested that oxidative stress associated with ROS accumulation in A. cepa may also play an active role in the reduction of MI, as it alters membrane fluidity and DNA stability.

It has been suggested that MMS may affect the nuclear membrane, which coordinates replication and transcription, stabilizes chromosome regions, and controls DNA damage repair, by altering the lipids of the inner membrane, which may lead to genetic damage8. According to Guruprasad et al.54, MMS is an electrophilic compound that can trigger the formation of CAs by attacking the nucleophilic center of DNA. Indeed, MMS exposure resulted in a definite accumulation of MN (Fig. 1a) and CAs in A. cepa root cells (Table 3 and Fig. 1). The CAs identified in the MMS group were ranked as sticky chromosome (Fig. 1b), vagrant chromosome (Fig. 1c), fragment (Fig. 1d), unequal organization of chromatin (Fig. 1e), bridge (Fig. 1f), nucleus with vacuole (Fig. 1g), orientation disorder (Fig. 1h) and irregular mitosis (Fig. 1i) from most to least considering the frequency of their presence. The present findings confirmed the results of Pehlivan et al.19, who found that MMS treatment increased MN and CAs accumulation in A. cepa root cells. Dias et al.55 also demonstrated that MMS triggered the formation of MN and several CA types, including chromosomal breaks, bridges and adherence in A. cepa. Moreover, Liman56 used MMS as a positive control for genotoxicity in A. cepa roots and revealed that exposure to this agent resulted in the formation of laggard and sticky chromosomes, bridging and polyploidy. In the study of Devi and Mullainathan41, it was shown that MMS-like chemical EMS induced the formation of MN, stickiness, bridging and many other CAs in C. annuum and this effect was exacerbated with increasing application dose.

Whole chromosomes or chromosome fragments that are not located in daughter cell nuclei and instead appear in the cytoplasm surrounded by a nuclear membrane separate from the main nucleus are known as MN41. It is regarded as a clastogenic endpoint that is a fundamental marker of DNA damage41,51. The clustering of chromosomes as a result of direct interaction of the mutagen with histones usually results in the formation of sticky chromosomes, which is the most frequently observed CA in this study (Fig. 1b)57. Stickiness can also be caused by chemical compounds altering the physical and chemical properties of genetic material, interactions of the chemical with phosphate groups in the DNA skeleton, condensation of DNA or formation of cross-links within or between chromatids41. A spindle abnormality known as a vagrant chromosome (Fig. 1c) occurs when the nucleus contains an uneven number of chromosomes, producing daughter cells with unusual shapes or sizes during interphase. In this case, MMS can be considered as a spindle toxin. Fragments (Fig. 1d) and sticky bridges (Fig. 1f) have been reported to cause structural changes in chromosomes and fragment formation is usually associated with the presence of MN58. Chacón et al.48 also stated that MMS has a role in the breakage of chromosomes. On the other hand, bridge may be generated due to the defects in telomeres and leads to the formation of chromosomal fragments59. Similar to vagrant, unequal chromatin organization (Fig. 1e) is brought on by a disruption in spindle thread order, and even vagrant occurrence can lead to unequally distributed chromatins60. One of the nuclear alterations that causes apoptosis is nuclear vacuolization (Fig. 1 g), which suggests that a nuclear toxin prevents DNA synthesis61. So, the present study has demonstrated that MMS functions as both a spindle and nuclear poison. According to Kalcheva et al.62, orientation disorder (Fig. 1h) in the MMS group is a polarization defect caused by improper functioning of the spindle thread system. Irregular mitosis (Fig. 1i) was another spindle defect-based CAs that appeared upon MMS application.

In the MMSAVE 1 and MMSAVE 2 groups, MI increased while MN and CAs frequencies decreased significantly compared to the MMS group (p < 0.05) (Table 3). Nevertheless, the mean values of MN, MI, and CAs in both groups remained statistically different from those of the control group (p < 0.05). This residual toxicity carries biological significance, suggesting that while AVE provides notable protection, it does not fully counteract the genotoxic impact of MMS at the tested concentrations. The findings, therefore emphasize both the strong antigenotoxic potential of AVE and the inherent limitations of phenolic defenses under severe genotoxic stress.

The attenuating effect of AVE on genotoxicity mediated by alterations in MI, MN, and CAs levels was demonstrated for the first time in a model organism. This protective modulation may be attributed to AVE’s rich phenolic compounds, which neutralize ROS generated by MMS, thereby preventing DNA and chromosomal damage and supporting cellular repair mechanisms. Co-application of AVE significantly lowered MDA levels while normalizing antioxidant enzyme activities, suggesting that AVE mitigated oxidative imbalance rather than merely stimulating stress-responsive enzymes. This restoration of redox homeostasis provides a plausible explanation for the observed recovery of mitotic activity and the reduction in chromosomal damage. Building on existing literature, the genoprotective effect of AVE also can be further attributed to its capacity to modulate molecular pathways involved in oxidative stress response and DNA repair. Phenolic compounds in AVE may activate the Nrf2 signaling pathway, enhancing the expression of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD and glutathione peroxidase. Additionally, AVE could support the upregulation of DNA repair enzymes, facilitating the correction of MMS-induced alkylation damage. These molecular mechanisms collectively contribute to the observed reduction in MN and CAs frequencies, reinforcing AVE’s role as a potent antigenotoxic agent. Bioactive compounds such as piperine and capsaicin have already been demonstrated to reduce MN accumulation resulting from MMS55. Additionally, co-administration of appropriate doses of Erythrina velutina extract with MMS has been proven to increase MMS-induced MI and decrease CAs in A. cepa. It has also been shown that mice treated with Calendula officinalis extract63 and Solanum cernuum extract64 had fewer MN-bearing polychromatic erythrocytes after being exposed to MMS. It has been documented that MMS causes DNA damage and oxidative stress65, which can be mitigated by antioxidant agents through multiple pathways, including lowering oxidative stress, reducing alkylation, or enhancing detoxifying enzyme activities11.

Molecular docking studies serve as a critical tool for investigating the interactions between small molecules and macromolecules, offering profound insights into their potential effects on cellular functions66. In this research, molecular docking analyses were employed to examine the binding affinities and interaction mechanisms of MMS with several key macromolecules (Table 4). These macromolecules included tubulins, DNA topoisomerases, glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase, and protochlorophyllide reductase, each of which plays a pivotal role in essential cellular processes such as microtubule assembly, DNA topology regulation, amino acid metabolism, and chl biosynthesis, respectively67,68,69. The interactions between MMS and these macromolecules are particularly noteworthy due to their potential to influence cellular health and functionality. For example, disruptions in microtubule dynamics, which are mediated by tubulins, can adversely affect processes such as cell division and intracellular transport70. Similarly, alterations in DNA topology, regulated by DNA topoisomerases, may lead to chromosomal instability and aberrations71. Furthermore, changes in the activity of glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase can disrupt amino acid metabolism72, while interactions with protochlorophyllide reductase may hinder chl biosynthesis and impair photosynthetic efficiency73. The findings from the molecular docking analysis are presented in Table 4 and Fig. 2, which illustrate the binding affinities and interaction patterns of MMS with the selected macromolecules. These results provide a foundational understanding of the molecular-level effects of MMS and its potential implications for cellular processes, chromosomal integrity, and photosynthetic performance. Interestingly, no hydrophobic interactions were found in any of the complexes that were examined. This could be explained by the physicochemical properties of the protein binding sites as well as the small molecular size and high polarity of MMS. According to earlier research, small and highly polar molecules typically create fewer hydrophobic contacts in docking simulations. This is probably because they have a smaller hydrophobic surface area and prefer polar interactions74. MMS exhibited a binding affinity of −4.29 kcal/mol with the tubulin alpha-1B chain, indicating a moderate interaction. The inhibition constant (Ki) of 713.16 µM suggests that MMS has a moderate inhibitory potential against this protein. The interaction is stabilized by hydrogen bonds with residues ALA99, ALA100, GLY144, THR145, ASN101, and ASP69. These residues are located in regions critical for tubulin’s structural integrity and polymerization. The absence of hydrophobic interactions implies that the binding is primarily driven by polar interactions. This finding aligns with the observed chromosomal abnormalities in the study, as tubulin plays a key role in spindle formation during cell division. Disruption of tubulin function by MMS could lead to mitotic errors and chromosomal aberrations. MMS showed a slightly lower binding affinity ( −3.91 kcal/mol) with the tubulin beta chain compared to the alpha-1B chain, with a higher Ki value of 1.36 mM. This indicates a weaker interaction. Hydrogen bonds were formed with ASN99, GLY142, and GLU69, which are located in the GTP-binding domain of tubulin. The lack of hydrophobic interactions suggests that the binding is predominantly polar. The weaker binding to the beta chain compared to the alpha chain may reflect differential susceptibility of tubulin subunits to MMS. This could contribute to the disruption of microtubule dynamics, further supporting the observed chromosomal abnormalities in this study.

The binding affinity of MMS with DNA topoisomerase I was −3.89 kcal/mol, with a Ki value of 1.4 mM, indicating a relatively weak interaction. Hydrogen bonds were formed with LYS493, GLY496, THR498, and GLU494, which are located near the active site of the enzyme. The absence of hydrophobic interactions suggests that the binding is driven by polar contacts. DNA topoisomerase I is essential for relieving DNA supercoiling during replication and transcription. The interaction of MMS with this enzyme could impair its function, leading to DNA damage and replication stress, consistent with the DNA damage observed in the study. MMS exhibited the lowest binding affinity ( −2.80 kcal/mol) with DNA topoisomerase II, with a Ki value of 8.81 mM, indicating a weak interaction. Hydrogen bonds were formed with SER464, LEU616, GLY617, and ASP541. The lack of hydrophobic interactions suggests that the binding is primarily polar. DNA topoisomerase II is crucial for chromosome segregation during mitosis. The weak interaction with MMS may not significantly inhibit the enzyme activity, but it could still contribute to genomic instability, especially in combination with other mechanisms of MMS-induced DNA damage.

MMS showed a binding affinity of −3.81 kcal/mol with glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase, with a Ki value of 1.61 mM, indicating a moderate interaction. Hydrogen bonds were formed with ARG130 (two bonds), ASN300, and ALA301 (two bonds). These residues are located near the active site of the enzyme, which is involved in chl biosynthesis. The absence of hydrophobic interactions suggests that the binding is driven by polar contacts. The interaction of MMS with this enzyme could impair chl synthesis due to disruption of amino acid metabolism, leading to the observed reduction in chl content in the study.

MMS exhibited a binding affinity of −3.81 kcal/mol with protochlorophyllide reductase, with a Ki value of 1.62 mM, indicating a moderate interaction. Hydrogen bonds were formed with VAL14, ASN86, and SER12, which are located near the enzyme’s active site. Protochlorophyllide reductase is essential for chl biosynthesis. The interaction of MMS with this enzyme could disrupt its function, contributing to the observed decrease in chl content. The absence of hydrophobic interactions suggests that the binding is primarily polar. This enzyme is also involved in chl biosynthesis, and its inhibition by MMS could further contribute to the observed reduction in chl content.

The molecular docking results indicate that MMS interacts with multiple macromolecules involved in critical cellular processes, including microtubule dynamics (tubulin), DNA topology regulation (topoisomerases), and chl biosynthesis (glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase and protochlorophyllide reductase). The binding affinities and inhibition constants suggest that MMS has a moderate inhibitory potential against these targets. These results are consistent with previous docking studies involving small polar molecules, which frequently show weaker interaction energies compared to larger, more hydrophobic ligands with established inhibitory activity74. Although MMS displayed relatively modest binding affinities, even weak interactions could have significant biological consequences. This is particularly plausible when such interactions act in combination with other MMS-induced mechanisms, such as DNA alkylation. The observed hydrogen bond interactions with key residues in the active sites or functional regions of these proteins suggest that MMS could disrupt their normal functions. This aligns with the experimental findings in the study, where MMS caused chromosomal abnormalities, DNA damage, and reduced chl content. The lack of hydrophobic interactions in all cases indicates that the binding is primarily driven by polar interactions, which is consistent with the chemical structure of MMS. These docking results provide a molecular basis for the observed biological effects of MMS in the present study.

In order to determine the biochemical impacts of MMS, AVE and mixtures of MMS and AVE on A. cepa root cells, changes in MDA and chl (a and b) contents as well as SOD and CAT enzyme activities following solution treatments were analyzed. No statistically significant differences were observed in the mean values of biochemical parameters of AVE 1, AVE 2 and the control groups (p > 0.05) (Table 5). In this case, exposure to selected AVE dosages did not cause biochemical toxicity in A. cepa. In contrast, the MMS-exposed group exhibited higher MDA content and SOD and CAT activities along with lower chl levels than those of the control group. It is noteworthy that all differences between means were statistically significant (p < 0.05). MDA level and SOD and CAT activities in the MMS group were determined approximately 2.1 times of the values in the control group. The findings of the present study corroborate those of the study conducted by Pehlivan et al.19, wherein different dosages of MMS were observed to induce an increase in SOD and CAT activity, concomitant with an elevation in MDA levels in A. cepa. In addition, the findings of Çavuşoğlu and Yalçin75 proved that 10 mg L−1 MMS caused increase in MDA level and alterations in antioxidant enzyme activities. In another study, it was revealed that the alkylating agent EMS induced oxidative stress in A. cepa and increased the activities of antioxidant enzymes, including SOD, CAT, ascorbate peroxidase, and glutathione reductase76. According to the study of Dhannoon et al.77, EMS application triggered the expression of Cu/Zn-SOD and MnSOD genes at high levels. In this case, in the battle against oxidative destruction associated with alkylating compounds, enhancement of the biosynthesis of enzymes is as important as an increase in their activity.

A disruption in the redox state brought on by either a rise in the generation of free radicals or a decline in antioxidant defenses against them is known as oxidative stress. SOD, CAT and MDA are among the most important indicators of oxidative imbalance78. The increase in antioxidant enzyme activities can be explained by the survival mechanism of the organism against free radical-induced damages79. SOD is a metalloenzyme that has a high affinity for superoxide and catalyzes the dismutation of this molecule to hydrogen peroxide and water80. On the other hand, CAT is the antioxidant enzyme responsible for detoxification of hydrogen peroxide by converting it into non-toxic water and oxygen81. Despite the elevated activities of these enzymes, increased production of free radicals causes the oxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids, which disrupts the membrane lipid bilayer and produces a number of harmful metabolites, including MDA82. It has been demonstrated that MDA, a lipid peroxidation byproduct, can damage DNA by interacting directly with DNA bases or by forming more reactive electrophilic molecules such as bifunctional epoxides83. Many studies showed that oxidative stress and DNA damage occur simultaneously following MMS exposure10,65. Indeed, although elevated SOD and CAT activities in the MMS-treated group indicate activation of the antioxidant defense system, this response was insufficient to prevent the increase in MDA levels and genetic damage in A. cepa stem cells (Table 2 and Table 4). Jiang et al.84 reported that hydrogen peroxide, which may continue to accumulate even if CAT is activated in cells, not only disrupts the integrity of biological membranes but also may facilitate the formation of hydroxyl radicals that directly target DNA, similar to MMS.

Pigments are primary indicators used to evaluate photosynthetic quality. Chl a and chl b are two vital molecules in photosynthetic apparatus. Chl a absorbs photons and converts them into energy. On the other hand, chl b absorbs photons and transfers them to chl a85. Chl reduction limits the plant’s ability to absorb light energy, which can compromise photosystem activity and downstream carbon assimilation processes. Therefore, examining the extent to which chl loss correlates with declines in photosynthetic efficiency would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the physiological consequences under stress conditions. MMS exposure induced biochemical alterations not only in the roots but also in the upper parts of the plant. In the MMS group, chl a and chl b levels decreased by 47.9% and 68.5%, respectively, compared to the control group. This finding indicated that MMS could be transported from the application site to the green leaves of the plant developing after the roots. It has previously been demonstrated that EMS exposure in Oryza sativa induces the formation of chl mutants by increasing chl synthesis86. However, in support of our findings, Rime et al.87 suggested that increasing doses of EMS reduced chl a and chl b levels in mango. A reduction of chl level could be caused either by a decrease in chl biosynthesis or overproduction of chl88. According to Pawar et al.89, EMS alters the chl metabolic pathway. Moreover, higher EMS doses result in greater mutagenesis activity. A decrease in chl pigments may be associated with several factors. These include the inhibition of plastid formation or the conversion of other plastids into chloroplasts. Mutations in genes involved in chl biosynthesis and damage to the relevant enzymes may also contribute. Additionally, the presence of ROS near the thylakoid membrane is another possible cause90,91.

The MMSAVE 1 and MMSAVE 2 groups exhibited lower MDA content and enzyme activities, and higher chl levels, in comparison to the MMS group (Table 5). The mean values for these parameters showed statistical differences between the three groups (p < 0.05). The attenuation of biochemical toxicity was more pronounced in the MMSAVE 2 group, and the mean values of the MMSAVE 2 group were closer to the values of the control group for all biochemical parameters. In the MMSAVE 2 group, MDA content and chl a and chl b activities decreased by 33.5%, 36.7%, and 35.7%, respectively, compared to the MMS group. On the other hand, the mean values of chl a and chl b of this group were 1.5 and 2 times of the MMS group, respectively. The observed decline in chl a and b levels following MMS exposure, along with their partial restoration after AVE treatment, suggests that MMS may induce oxidative damage within chloroplasts and interfere with chlorophyll biosynthesis. The elevated MDA content and changes in antioxidant enzyme activities point to enhanced lipid peroxidation at the thylakoid membranes, a process known to accelerate pigment degradation and compromise photosynthetic efficiency91. Consistent with these findings, molecular docking analyses indicated that MMS can interact with key enzymes involved in chlorophyll formation-such as glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase and protochlorophyllide reductase- which may partially explain the loss of chlorophyll. These interactions, combined with oxidative membrane damage, synergistically induce the observed decline in pigment stability and photosynthetic efficiency. To the best of our knowledge, there is a lack in the literature investigating the therapeutic effect of AVE against MMS-induced damage. However, AVE has already been shown to have a protective effect against a number of other toxicants. The findings of Jurić et al.6 demonstrated that AVE exhibited a protective effect against cisplatin-induced oxidative stress in rats by restoring the antioxidant defense system. Additionally, it has been evidenced that extracts obtained from both roots and aerial parts of A. vulgaris possess radical-scavenging capacity and effectively reduce lipid peroxidation2. In a separate study, AVE demonstrated efficacy in mitigating isoproterenol-induced cardiac injury, attributable to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. The study observed a direct proportionality between the applied dose and modifications in SOD and CAT activities, as well as MDA levels within cells93. We were unable to find any reports addressing the effect of AVE on chl biosynthesis in plants. However, there are studies showing that various plant extracts can enhance the levels of chl pigments in A. cepa experiencing toxicity60,94. The bioactive compounds present in plant extracts may protect chlorophyll from degradation by neutralizing free radicals, absorbing or reflecting UV light, or suppressing enzymes responsible for chlorophyll degradation.

In the present study, microscopic examinations were utilized to demonstrate the damage caused by 4000 µM MMS treatment and the protective effect of AVE in meristematic cells of A. cepa roots. Following the application of the extract at concentrations of 250 mg/L and 500 mg/L, no damage was observed in the roots of the AVE 1 and AVE 2 groups, similar to the control group (Table 6 and Fig. 3a, b and c). In contrast, 4000 µM MMS treatment severely damaged meristematic cells in A. cepa roots (Table 6 and Fig. 3). In the MMS group, epidermis cell damage (Fig. 3d), flattened cell nucleus (Fig. 3e) and cortex cell damage (Fig. 3f) were found at a ‘severe’ level, while thickening of the cortex cell wall (Fig. 3g) was found at a ‘moderate’ level. Microscopic observations were in agreement with biochemical indicators of oxidative stress (increased MDA levels and enhanced SOD/CAT activity) and genotoxic alterations (decreased MI and elevated MN and CAs frequencies). Together, these findings outline a likely mechanistic sequence in which MMS induces DNA alkylation and oxidative stress, leading to disturbances in microtubule organization and DNA-associated proteins-as supported by the docking results with tubulin and topoisomerase enzymes. These disruptions can cause mitotic spindle malfunction, chromosomal instability, and ultimately, structural damage to membranes and organelles. The MMS application caused a phytotoxic effect that was clearly observable within the root meristem of the A. cepa, which may have a detrimental effect on the plant by limiting the water and substance uptake of the plant. The existing body of knowledge on the structural alterations of MMS on root meristem tissue is scarce. However, the results obtained from the present study are in agreement with the findings of Pehlivan et al.19, who observed deformity of the epidermis, flattened nucleus, deformity in cortex cell and cortex cell wall thickening in A. cepa root meristem due to increasing doses of MMS. Pehlivan et al.19 also interpreted that one of the main causes of MMS-induced changes in A. cepa root meristem tissue was physical stress caused by increased number of root epithelial and cortex cells and thickening of the walls of cortex cells to reduce the uptake of harmful chemicals by the plant. In addition to being caused by physical stress, flattened nuclei may be indicative of genetic damage caused by toxicant-induced oxidative stress, peroxidation of cell membranes or genotoxicity50. On the other hand, when AVE was co-applied with MMS, the severity of MMS-induced damage to the root meristem was mitigated. This reducing effect was more notable in the MMSAVE 2 group, which received a higher dosage of AVE. In the MMSAVE 2 group treated with 500 mg/L AVE together with MMS, epidermis cell damage, flattened cell nucleus and cortex cell damage decreased to slightly damaged level, while thickening of the cortex cell wall disappeared completely. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study providing evidence of the protective effect of AVE against toxicant-induced damage to root meristem tissue in plants. However, the findings concur with those of preceding research, which has indicated the protective effect of plant extracts rich in antioxidants against structural impairments caused by deleterious chemicals in the roots of A. cepa36,61,95. Treatment with AVE appears to interfere with these adverse effects scavenging reactive oxygen species, and protecting membrane integrity thereby conferring comprehensive protection against MMS toxicity. The findings outlined above demonstrate that the protective effect of AVE against MMS-induced meristematic defects may be a consequence of its high antioxidant content.

Observed meristematic tissue organization alterations in A. cepa roots caused by MMS. Normal appearance of epidermis cells (a), normal appearance of cell nucleus-oval (b), normal appearance of cortex cells (c), epidermis cell damage (d), flattened cell nucleus (e), cortex cell damage (f), thickening of cortex cell wall (g). Bar = 10 µm.

The chemical analysis was conducted to support biological interpretation rather than to establish a complete phytochemical fingerprint of the extract. The findings of this study suggest that the protective activity of AVE is comparable to that of several other plant-based extracts that have previously been tested against MMS-induced toxicity. For instance, pre-treatment with Crocus sativus stigma aqueous extract and its major component crocin has been reported to reduce the percentage of tail DNA in MMS-exposed renal and pulmonary tissues by approximately 2.7-fold and 4.5-fold, respectively96. In another study, Mikania laevigata extract (200 mg/kg orally) has been demonstrated to cause a 52% reduction in damage index and a 56% decrease in damage frequency in bone marrow cells subjected to MMS97. In the study by Vilela et al.98, it has been found that Hibiscus acetosella leaf extract provides substantial DNA protection against MMS in both the comet assay and MN test models at doses ranging from 50 to 100 mg/kg. The characterization of phenolic compounds in AVE by LC/MS–MS is presented in Table 7 and Fig. 4. Rosmarinic acid, catechin, p-coumaric acid, rutin, gentisic acid, quercetin, ferulic acid, and caffeic acid were the most prevalent phenolic compounds in AVE based on their abundance levels. Previous research has associated the free radical scavenging and genoprotective capacity of AVE with the phenolic compounds in its content2,99. The phenolic ratios in the composition may differ based on the age of the plant, growing conditions, quantification method, and extraction technique and solvent, even though there are numerous findings on the phenolic composition of AVE in the literature. For instance, AVE was high in gallic acid, caffeic acid, catechin, and quercetin, according to the study of Vlaisavljević et al.4. On the other hand, Jurić et al.6 determined that ellagic acid, catechin, and catechin gallate are the dominant phenolics in AVE. In addition to their general antioxidant role, the major identified phenolic components in AVE have a role in various cellular defense pathways. Rosmarinic acid is a polyphenolic compound found naturally in members of the plant kingdom, which can affect the activities of numerous enzymes and transcriptional factors within the cells100. According to Jeong et al.101, rosmarinic acid inhibits oxidative stress-induced DNA damage in murine myoblast C2C12 cells. In addition, it has been proposed that rosmarinic acid suppress lipid peroxidation, which is mostly accomplished by altering membrane fluidity and preventing ROS formation between the bilayer102. Rosmarinic acid has been reported to activate the Nrf2-Keap1 signaling pathway, leading to transcriptional up-regulation of antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione peroxidase and heme oxygenase-1103. Moreover, it has the ability to protect DNA and to reduce chromosomal fragmentation104. Catechin, the second most abundant phenolic compound in AVE (Table 7) has been reported to participate in epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation-demethylation and histone acetylation-deacetylation, while also modifying the balance between tubulin and microtubule dynamics4. Another study revealed that catechin regulates MAPK signaling cascades and preserves mitochondrial function under stress, thus maintaining redox balance and cellular viability105,106. In the study by Kittipornkul et al.107, it has been demonstrated that exogenous catechin maintained chlorophyll levels, promoted catalase activity, and decreased lipid peroxidation in rice subjected to ozone stress. The third most common phenolic in AVE, p-coumaric acid, has been shown to decrease oxidative stress by modifying SOD and CAT activities and lowering lipid peroxidation108. Additionally, Pei et al.109 suggested that p-coumaric acid protects DNA and reduces chromosomal disorders by scavenging both hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radical, the production of which is linked to hydrogen peroxide. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that pretreatment with rutin and quercetin decreased chromium trioxide-induced MN accumulation in mouse polychromatic erythrocytes110. Gentisic acid was another phenolic compound that was present in considerable quantities in AVE (Table 7). It is a salicylic acid derivative and has potential to scavenge free radicals to prevent them from reaching genetic apparatus111. The marked protective response observed in AVE-treated groups may not arise from a single compound but is more plausibly associated with the combined presence of several phenolics identified by LC–MS/MS, such as rosmarinic acid, catechin, p-coumaric acid, rutin, and gentisic acid. Phenolic compounds reported in the literature are known to act cooperatively through mechanisms such as free radical scavenging, metal chelation, regeneration of endogenous antioxidants, and modulation of redox-sensitive signaling pathways112. Through these complementary mechanisms, mixtures of phenolics typically provide stronger cytoprotection than any individual compound (Skroza et al.113). Some of the phenolic compounds found in AVE such as rosmarinic acid, catechin, and rutin have been shown to activate endogenous antioxidant defense systems through modulation of redox-sensitive transcription factors such as Nrf2114,115,116. Activation of the Nrf2/Keap1 pathway promotes the transcription of genes encoding antioxidant and detoxification enzymes thereby enhancing cellular resilience against oxidative and genotoxic stress116. Additionally, these phenolics may contribute to the maintenance of genomic integrity by stimulating DNA damage response mechanisms and facilitating the repair of alkylated or oxidized bases. Although Nrf2 activation and DNA-repair enzyme expression were not directly evaluated in the present study, these pathways may provide a plausible biological framework to explain the observed normalization of antioxidant enzyme activity and reduction in MN and CAs in the MMSAVE1 and MMSAVE 2 groups. Future studies that quantify the expression of Nrf2-regulated genes and DNA-repair markers would help verify these proposed protective mechanisms in plant systems.

The progressively greater recovery seen in physiological, biochemical, and genotoxic parameters with increasing AVE concentration (MMSAVE N1 < MMSAVE 2) further supports this view, implying that a higher overall phenolic content enhances the plant’s ability to counter MMS-induced oxidative stress and to preserve cellular integrity.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that AVE effectively mitigates MMS-induced physiological, genotoxic, biochemical, and anatomical damage in A. cepa. The physiological, cytogenetic, biochemical, and anatomical findings collectively revealed that MMS triggers severe toxicity by inducing oxidative stress and directly interacting with cellular structures. Co-application of AVE markedly reduced these adverse effects, confirming its strong antioxidant and genoprotective potential. Although AVE significantly alleviated MMS-induced toxicity, some residual damage persisted, suggesting that it cannot completely counteract genotoxic stress at the tested concentrations. The more pronounced protection observed at 500 mg/L highlights the dose-dependent nature of AVE’s defensive action.

The observed protective effects are likely due to the synergistic interactions among its major identified phenolic constituents-rosmarinic acid, catechin, and p-coumaric acid-reducing oxidative stress, stabilize cellular components, and preserve genomic stability. Molecular docking outcomes also supports the view that AVE-mediated antioxidant protection may contribute to the mitigation of MMS-induced disturbances in microtubule dynamics, DNA topology, and chlorophyll biosynthetic pathways. Overall, AVE emerges as a promising natural agent capable of mitigating genotoxic damage through its phenolic-based defense mechanisms. Future studies should aim to isolate the active compounds, elucidate molecular pathways such as Nrf2 activation and DNA repair modulation, and validate these protective effects in in vivo and other models. The present work provides a valuable foundation for future pharmacological and toxicological research exploring the therapeutic potential of A. vulgaris as a natural cytoprotective source.

References

Gibbons, S. An overview of plant extracts as potential therapeutics. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 13, 489–497 (2003).

Boroja, T. et al. The biological activities of roots and aerial parts of Alchemilla vulgaris L. S. Afr. J. Bot. 116, 175–184 (2018).

Tadić, V., Krgović, N. & Žugić, A. Lady’s mantle (Alchemilla vulgaris L., Rosaceae): A review of traditional uses, phytochemical profile, and biological properties. Lek. Sirovine. 40, 66–74 (2020).

Vlaisavljević, S. et al. Alchemilla vulgaris agg. (lady’s mantle) from central Balkan: Antioxidant, anticancer and enzyme inhibition properties. RSC Adv. 9, 37474–37483 (2019).

Jakimiuk, K. et al. Ex vivo biotransformation of lady’s mantle extracts via the human gut microbiota: The formation of phenolic metabolites and their impact on human normal and colon cancer cell lines. Front. Pharmacol. 16, 1504787 (2025).

Jurić, T. et al. Protective effects of Alchemilla vulgaris L. extracts against cisplatin-induced toxicological alterations in rats. S. Afr. J. Bot. 128, 141–151 (2020).

Brink, A., Schulz, B., Stopper, H. & Lutz, W. K. Biological significance of DNA adducts investigated by simultaneous analysis of different endpoints of genotoxicity in L5178Y mouse lymphoma cells treated with methyl methanesulfonate. Mutat. Res. Fund. Mol. Mutagen. 625, 94–101 (2007).

Ovejero, S., Soulet, C. & Moriel-Carretero, M. The alkylating agent methyl methanesulfonate triggers lipid alterations at the inner nuclear membrane that are independent from its DNA-damaging ability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 7461 (2021).

Mustafa, M. et al. Characterization of structural, genotoxic, and immunological effects of methyl methanesulfonate (MMS) induced DNA modifications: Implications for inflammation-driven carcinogenesis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 268, 131743 (2024).

Ali Khan, M. et al. Effect of lemon grass extract against methyl methanesulfonate-induced toxicity. Toxin Rev. 40, 1172–1186 (2021).

Siddique, Y. H. et al. Protective effect of luteolin against methyl methanesulfonate-induced toxicity. Toxin Rev. 40, 65–76 (2021).

Tkachuk, N. & Zelena, L. An onion (Allium cepa L.) as a test plant. Biot. Hum. Technol. 3, 50–59 (2022).

Kalefetoğlu Macar, T. & Macar, O. A study on the effect of Hypericum perforatum L extract on vanadium toxicity in Allium cepa L.. Sci. Rep. 14, 28486 (2024).

Melo, E. C. D. et al. Allium cepa as a toxicogenetic investigational tool for plant extracts: A systematic review. Chem. Biodivers. 21, e202401406 (2024).

Felicidade, I. et al. Mutagenic and antimutagenic effects of aqueous extract of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) on meristematic cells of Allium cepa. Genet. Mol. Res. 13, 9986–9996 (2014).

Ristea, M. E. & Zarnescu, O. Effects of indigo carmine on growth, cell division, and morphology of Allium cepa L. root tip. Toxics. 12, 194 (2024).

Liman, R., Ali, M. M., Istifli, E. S., Ciğerci, İH. & Bonciu, E. Genotoxic and cytotoxic effects of pethoxamid herbicide on Allium cepa cells and its molecular docking studies to unravel genotoxicity mechanism. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 63127–63140 (2022).

Ince Yardimci, A. et al. Synthesis and characterization of single-walled carbon nanotube: Cyto-genotoxicity in Allium cepa root tips and molecular docking studies. Microsc. Res. Tech. 85, 3193–3206 (2022).

Pehlivan, Ö. C., Cavuşoğlu, K., Yalçin, E. & Acar, A. In silico interactions and deep neural network modeling for toxicity profile of methyl methanesulfonate. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 117952–117969 (2023).

Atik, M., Karagüzel, O. & Ersoy, S. Effect of temperature on germination characteristics of Dalbergia sissoo seeds. Mediterr. Agric. Sci. 20, 203–210 (2007).

Staykova, T. A., Ivanova, E. N. & Velcheva, D. G. Cytogenetic effect of heavy-metal and cyanide in contaminated waters from the region of southwest Bulgaria. J. Cell. Mol. Biol. 4, 41–46 (2005).

Fenech, M. et al. HUMN project: Detailed description of the scoring criteria for the cytokinesis-block micronucleus assay using isolated human lymphocyte cultures. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 534, 65–75 (2003).

Lacey, S. E., He, S., Scheres, S. H. & Carter, A. P. Cryo-EM of dynein microtubule-binding domains shows how an axonemal dynein distorts the microtubule. Elife 8, e47145 (2019).

Staker, B. L. et al. The mechanism of topoisomerase I poisoning by a camptothecin analog. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 99, 15387–15392 (2002).

Wang, Y. R. et al. Producing irreversible topoisomerase II-mediated DNA breaks by site-specific Pt (II)-methionine coordination chemistry. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 10861–10871 (2017).

Mizutani, H. & Kunishima, N. Crystal structure of glutamate-1-semialdehyde 2,1-aminomutase from Aeropyrum pernix. https://www.wwpdb.org/pdb?id=pdb_00002zsl. https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb2ZSL/pdb (2011)

Zhang, S. et al. Structural basis for enzymatic photocatalysis in chlorophyll biosynthesis. Nature 574, 722–725 (2019).

Guex, N. & Peitsch, M. C. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-Pdb Viewer: An environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18, 2714–2723 (2005).

O’Boyle, N. M. et al. Open Babel: An open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminf. 3, 33 (2011).

Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2785–2791 (2009).

Zou, J., Yue, J., Jiang, W. & Liu, D. Effects of cadmium stress on root tip cells and some physiological indexes in Allium cepa var. agrogarum L. Acta Biol. Cracov. Ser. Bot. 54, 129–141 (2012).

Beauchamp, C. & Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase: Improved assays and an assay applicable to acrylamide gels. Anal. Biochem. 44, 276–287 (1971).

Beers, R. F. & Sizer, I. W. Colorimetric method for estimation of catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 195, 133–139 (1952).

Unyayar, S., Celik, A., Çekiç, F. Ö. & Gözel, A. Cadmium-induced genotoxicity, cytotoxicity and lipid peroxidation in Allium sativum and Vicia faba. Mutagenesis 21, 77–81 (2006).

Kaydan, D., Yagmur, M. & Okut, N. Effects of salicylic acid on the growth and some physiological characters in salt stressed wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J. Agri. Sci. 13, 114–119 (2007).

Witham, F. H., Blaydes, D. R. & Devlin, R. M. Experiments in Plant Physiology (ed. Witham, F. H.) (Van Nostrand Reinhold Co, 1971).

Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçın, E. Spectral shift supported epichlorohydrin toxicity and the protective role of sage. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 1374–1385 (2023).

Akman, T. C. et al. LC-ESI-MS/MS chemical characterization, antioxidant and antidiabetic properties of propolis extracted with organic solvents from Eastern Anatolia Region. Chem. Biodivers. 20, e202201189 (2023).

Kayir, Ö., Doğan, H., Alver, E. & Bilici, İ. Quantification of phenolic component by LC-HESI-MS/MS and evaluation of antioxidant activities of Crocus ancyrensis (Ankara Çiğdemi) extracts obtained with different solvents. Chem. Biodivers. 20, e202201186 (2023).

Shah, S. N. M., Gong, Z. H., Arisha, M. H., Khan, A. & Tian, S. L. Effect of ethyl methyl sulfonate concentration and different treatment conditions on germination and seedling growth of the cucumber cultivar Chinese long (9930). Genet. Mol. Res. 14, 2440–2449 (2015).

Devi, A. S. & Mullainathan, L. Genotoxicity effect of ethyl methanesulfonate on root tip cells of chilli (Capsicum annuum L.). World J. Agric. Sci. 7, 368–374 (2011).

Türkoğlu, A. Ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) mutagen toxicity-induced DNA damage, cytosine methylation alteration, and iPBS-retrotransposon polymorphisms in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Agronomy 13, 1767 (2023).

Hu, Z., Cools, T. & De Veylder, L. Mechanisms used by plants to cope with DNA damage. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 67, 439–462 (2016).

Noori, A. et al. Silver nanoparticles in plant health: Physiological response to phytotoxicity and oxidative stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 205, 108538 (2024).

Hamad, I., Erol-Dayi, O., Pekmez, M., Onay-Ucar, E. & Arda, N. Free radical scavenging activity and protective effects of Alchemilla vulgaris (L.). J. Biotechnol. 131, 40–41 (2007).

Silva, D. S. et al. Investigation of protective effects of Erythrina velutina extract against MMS induced damages in the root meristem cells of Allium cepa. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 23, 273–278 (2013).

Rathnasamy, S., Mohamed, K. B., Sulaiman, S. F. & Akinboro, A. Evaluation of cytotoxic, mutagenic and antimutagenic potential of leaf extracts of three medicinal plants using Allium cepa chromosome assay. Int. Curr. Pharm. J. 2, 131–140 (2013).

Chacón, C. F., González, E. C. L. & Poletta, G. L. Biomarkers of geno-and cytotoxicity in the native broad-snouted caiman (Caiman latirostris): chromosomal aberrations and mitotic index. Mutat. Res. Genet. Toxicol. Environ. Mutagen. 867, 503353 (2021).

El-Adl, A. M., Kash, K. S., Zaied, K. A. & Kamal, M. I. Effect of endoxan and ethyle methane sulphonate on chromosomal behaviour and mitotic index in somatic cells of onion (Allium cepa, L.). J. Agr. Chem. Biotechnol. 4, 93–102 (2013).

Ayhan, B. S. et al. Comprehensive analysis of royal jelly protection against cypermethrin-induced toxicity in the model organism Allium cepa L., employing spectral shift and molecular docking approaches. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 203, 105997 (2024).

Graña, E. Mitotic index in Advances in plant ecophysiology techniques (eds. Sánchez-Moreiras, A. M. & Reigosa, M. J.) 231–240 (Springer, 2018).

Çavuşoğlu, K., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Macar, O., Çavuşoğlu, D. & Yalçın, E. Comparative investigation of toxicity induced by UV-A and UV-C radiation using Allium test. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 33988–33998 (2022).

Bianchi, J., Fernandes, T. C. C. & Marin-Morales, M. A. Induction of mitotic and chromosomal abnormalities on Allium cepa cells by pesticides imidacloprid and sulfentrazone and the mixture of them. Chemosphere 144, 475–483 (2016).

Guruprasad, K. P. et al. Brahmarasayana protects against ethyl methanesulfonate or methyl methanesulfonate induced chromosomal aberrations in mouse bone marrow cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 12, 113 (2012).

Dias, M. S. et al. Cytogenotoxicity and protective effect of piperine and capsaicin on meristematic cells of Allium cepa L. Anais Acad. Brasil. Ci. 93, e20201772 (2021).

Liman, R. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of 4-methylimidazole on Allium cepa root tips. Res. J. Biotech. 15, 121–127 (2020).

Rai, P. & Dayal, S. Evaluating genotoxic potential of chromium on Pisum sativum. Chromosom. Bot. 11, 44–47 (2016).

Kuchy, A. H., Wani, A. A. & Kamili, A. N. Cytogenetic effects of three commercially formulated pesticides on somatic and germ cells of Allium cepa. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 23, 6895–6906 (2016).

Bolzán, A. D. & Bianchi, M. S. Telomeres, interstitial telomeric repeat sequences, and chromosomal aberrations. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 612, 189–214 (2006).

Üstündağ, Ü., Macar, O., Kalefetoğlu Macar, T., Yalçın, E. & Çavuşoğlu, K. Effect of Melissa officinalis L. leaf extract on manganese-induced cyto-genotoxicity on Allium cepa L.. Sci. Rep. 13, 22110 (2023).

Topatan, Z. Ş et al. Alleviatory efficacy of Achillea millefolium L. in etoxazole-mediated toxicity in Allium cepa L. Sci. Rep. 14, 31674 (2024).

Kalcheva, V. P., Dragoeva, A. P., Kalchev, K. N. & Enchev, D. D. Cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of Br-containing oxaphosphole on Allium cepa L. root tip cells and mouse bone marrow cells. Genet. Mol. Biol. 32, 389–393 (2009).

Leffa, D. D. et al. Genotoxic and antigenotoxic properties of Calendula officinalis extracts in mice treated with methyl methanesulfonate. Adv. Life Sci. 2, 21–28 (2012).

Damasceno, J. L. et al. Protective effects of Solanum cernuum extract against chromosomal and genomic damage induced by methyl methanesulfonate in Swiss mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 83, 1111–1115 (2016).

Lackinger, D., Eichhorn, U. & Kaina, B. Effect of ultraviolet light, methyl methanesulfonate and ionizing radiation on the genotoxic response and apoptosis of mouse fibroblasts lacking c-Fos, p53 or both. Mutagenesis 16, 233–241 (2001).

Kitchen, D. B., Decornez, H., Furr, J. R. & Bajorath, J. Docking and scoring in virtual screening for drug discovery: Methods and applications. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 3, 935–949 (2004).

Wang, J. C. Cellular roles of DNA topoisomerases: a molecular perspective. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 430–440 (2002).

Buey, R. M., Díaz, J. F. & Andreu, J. M. The nucleotide switch of tubulin and microtubule assembly: A polymerization-driven structural change. Biochemistry 45, 5933–5938 (2006).

Vedalankar, P. & Tripathy, B. C. Evolution of light-independent protochlorophyllide oxidoreductase. Protoplasma 256, 293–312 (2019).

Parker, A. L., Kavallaris, M. & McCarroll, J. A. Microtubules and their role in cellular stress in cancer. Front. Oncol. 4, 153 (2014).

Zagnoli-Vieira, G. & Caldecott, K. W. Untangling trapped topoisomerases with tyrosyl-DNA phosphodiesterases. DNA Repair 94, 102900 (2020).

Grimm, B. Glutamate 1-semialdehyde aminotransferase, a unique enzyme in chlorophyll biosynthesis in Biochemistry of vitamin B6 and PQQ (eds. Marino, G., Sannia, G. & Bossa, F.) 99–103 (Springer, 1994).

Fujita, Y. & Bauer, C. E. Reconstitution of light-independent protochlorophyllide reductase from purified BchL and BchN-BchB subunits: in vitro confirmation of nitrogenase-like features of a bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23583–23588 (2000).

Ferreira, L. G., Dos Santos, R. N., Oliva, G. & Andricopulo, A. D. Molecular docking and structure-based drug design strategies. Molecules 20, 13384–13421 (2015).

Çavuşoğlu, K. & Yalçin, E. Antioxidant-oxidant balance and vital parameter alterations in an eukaryotic system induced by aflatoxin B2 exposure. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 37275–37281 (2019).

Tan, D. et al. Rhodamine B induces long nucleoplasmic bridges and other nuclear anomalies in Allium cepa root tip cells. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 21, 3363–3370 (2014).

Dhannoon, O. M., Alfalahi, A. O. & Ibrahim, K. M. Cu/Zn and MnSOD gene expression induced by ethyl methanesulfonate and drought stress in maize in AIP Conference Proceedings. 2290, 1-6 (2020).

Shakya, R. Markers of oxidative stress in plants in Ecophysiology of tropical plants (eds. Tripathi, S., Bhadouria, R., Srivastava, P., Singh, R. & Devi, R. S.) 298–310 (CRC Press, 2024).

Noaishi, M. A. F., Eweis, E. E. A. R., Saleh, A. Y. & Helmy, W. S. Evaluation of the mutagenicity and oxidative stress of fipronil after subchronic exposure in male albino rats. Egypt. Acad. J. Biol. Sci. F. Toxicol. 13, 129–141 (2021).

Demirci-Çekiç, S. et al. Biomarkers of oxidative stress and antioxidant defense. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 209, 114477 (2022).

Shuvo, M. R. K., Bhuya, A. R., Al Nahid, A. & Ghosh, A. Identification, characterization, and expression profiling of catalase gene family in Sorghum bicolor L. Plant Gene. 41, 100482 (2025).

Anet, A., Olakkaran, S., Purayil, A. K. & Puttaswamygowda, G. H. Bisphenol A induced oxidative stress mediated genotoxicity in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Hazard. Mater. 370, 42–53 (2019).

Martinez, G. R. Oxidative and alkylating damage in DNA. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 544, 115–127 (2003).