Abstract

This paper experimentally integrates an existing Kirchhoff–Law–Johnson–Noise (KLJN) physical key exchange scheme as a source of truly random keys for decentralized identifiers (DIDs). Web 3.0 is driven by secure keys, typically represented in hexadecimal, that are pseudo-randomly generated by an initialization vector and complex computational algorithms. We demonstrate that the statistical physical KLJN scheme eliminates the additional computational power by naturally generating physically random binary keys to drive the creation of DIDs that are appended to an Ethereum blockchain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Link to web 3.0

Footnote 1Web 3.0 currently exists with the purpose of bringing back ownership to its users1,2,4. To accomplish this, it takes a decentralized approach using blockchain technology5. Similar to a linked list, blockchains consist of blocks appended to a preexisting list. Each block contains information about the previous and preceding block. However, no previous blocks can be deleted or altered6.

Information security in the present day is highly centralized; all data is controlled by singular entities such as the protocols within SSL and TLS, and users have to trust third parties to verify that their data is encrypted7,8. For example, social media companies such as X (formerly known as Twitter), Facebook, and Instagram are all operated by a centralized power: the admin assigned by each company. This system of storing information is based on Web 2.0. The basis of Web 2.0 is that a central power ensures the safety and accuracy of information online and decides what is distributed to its users. These administrators control what information is distributed to its users and which must be hidden or deleted from the platform. For these reasons, this has the potential to be a gateway to corruption, as the basis of the population’s access to information are influenced by personal biases9.

Web 3.0, due to the nature of its data structure, eliminates this problem entirely by removing the centralized power and using other methods of verification to determine the accuracy of information on the internet. The obstacle encountered when trying to incorporate Web 3.0 into education is the centralized nature of learning. In modern society, the validity of an academic credential is established by the institution itself rather than defining individual skills learned. In Web 2.0, the user does not have any ownership of the information that they post online. However, Web 3.0 resolves this issue. In the present paper, we demonstrate that the decentralized elements of Web 3.0 can be utilized in order to ensure that the accomplishments in education remain assigned to the user.

Decentralized identity

Decentralized identity has emerged as a foundational component of Web 3.0 infrastructure, enabling users to control their own digital credentials without reliance on centralized identity providers10. Figure 1 shows an example of a DID document. The W3C DID Core specification defines the standard for creating and resolving decentralized identifiers (DIDs), allowing individuals and organizations to cryptographically prove ownership and control of their identities on distributed ledgers11,12.

Recent advances in DID systems have focused on enhancing security, scalability, and interoperability. Xian et al. provide a comprehensive survey of decentralized identity management systems, covering architectures, consensus mechanisms, and privacy-preserving techniques across multiple blockchain platforms13. Li et al. introduce DisIMS, a fully distributed identity management system that leverages blockchain for transparent and auditable identity operations14. Deng et al. propose FutureDID, a fully decentralized identity framework with multi-party verification to prevent single points of compromise15. Zheng et al. present IDEA-DAC, an advanced credential system using zero-knowledge JSON proofs to enhance privacy while maintaining auditability16.

However, a critical gap remains: all existing DID systems, including those cited above, depend on pseudorandom or deterministically generated cryptographic keys for the underlying identifiers. These keys are typically produced by computationally intensive algorithms such as elliptic curve cryptography (ECC), whose security relies on the assumption that certain mathematical problems are computationally hard–an assumption that may be threatened by advances in quantum computing or algorithmic breakthroughs . Furthermore, the randomness of these keys depends entirely on the quality and unpredictability of the seed value supplied to the pseudorandom number generator (PRNG), a dependency that has been exploited in known RNG attacks17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28.

Our work addresses this gap by demonstrating that DID key generation can instead be grounded in physical randomness derived from thermal noise, leveraging the unconditional security guarantees of the Kirchhoff–Law–Johnson–Noise (KLJN) scheme. Unlike the systems surveyed above, the KLJN-based approach is not dependent on computational hardness assumptions or algorithmic RNG security; rather, it derives its security from fundamental physical principles (the second law of thermodynamics). By integrating KLJN key generation directly into a DID framework (Veramo), we show that DIDs can be established with information-theoretic security, independent of the number of users and resistant to RNG-based attacks.

Example DID document structure with key fields: identifier, controller, public key, and algorithm metadata2.

The DID keys are generated using the base encryption methods for Ethereum blockchains, i.e. a combination of public and private key encryption29. The public key can be generated using a public key hex and ES256 algorithms30. The private key is generated based on elliptic curve cryptography which is commonly used in Bitcoin30,31. However, the vulnerability with the pseudo-random generation is that if either of the keys are found, anyone can access the user. Additionally, these pseudo-random methods involve multiple computational steps, thus the amount of computational power increases accordingly. These results show that secure keys can be generated without computational overhead, i.e., the keys can be generated naturally. Unlike conventional deterministic or computational key generation methods commonly used in decentralized identity systems, which rely on algorithmic processes vulnerable to cryptographic and implementation attacks, our approach leverages the KLJN scheme to achieve true information-theoretic security3,17,18,19,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95. Conventional DID key generation mechanisms have been shown to be susceptible to attacks leading to full impersonation, potential permanent loss of digital identity, and unauthorized access96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109. By exploiting the intrinsic randomness of thermal noise, the KLJN scheme eliminates these vulnerabilities, ensuring that secure keys can be generated independently of the number of users without relying on computational hardness assumptions. In the present paper, we explore how the statistical physical phenomena of the KLJN secure key exchange scheme can generate keys to support the Semantic Web protocols that drive DIDs.

The KLJN scheme

The KLJN scheme is a statistical physical scheme that leverages the well-established Johnson-Nyquist noise phenomenon, which describes the thermal noise voltage generated across a resistor due to random electron motion110. This fundamental physical process provides the randomness source for the key exchange.

Key system parameters include resistor values, noise bandwidth, temperature control, and sampling rates. Resistor values are selected to maximize the distinguishability of valid states while minimizing information leak. The noise bandwidth determines the bit generation speed, balancing between throughput and noise averaging for secure communication. Temperature uniformity ensures consistent noise levels. Sampling rates must comply with Nyquist criteria to capture full noise information111. Careful hardware selection and calibration are necessary to maintain these parameters within secure operational margins.

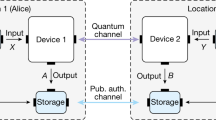

Figure 2 illustrates the core of the KLJN scheme. Communicating parties Alice and Bob are connected by a publicly accessible wire, which has voltage and current, denoted by \(U_{\textrm{w}}(t)\) and \(I_{\textrm{w}}(t)\), respectively. Each communicating party has identical pairs of resistors \(R_{\textrm{H}}\) and \(R_{\textrm{L}}\) (\(R_{\textrm{H}} > R_{\textrm{L}}\)) and their respective artificial noise generators \(U_{\textrm{H,A}}(t)\), \(U_{\textrm{L,A}}(t)\), \(U_{\textrm{H,B}}(t)\), and \(U_{\textrm{L,B}}(t)\) (the former two belonging to Alice, the latter two belonging to Bob) that emulate thermal noise at a publicly-agreed-upon \(T_{\textrm{eff}}\) (typically > \(10^{15}\) K).

To generate a single bit, Alice and Bob begin the bit exchange period (BEP) by randomly selecting one of their resistors to connect to the wire, observing the instantaneous noise voltages over the wire, and taking the mean-square value of those noise voltages to assess the bit status. The mean-square voltage is given by the Johnson Formula,

where k represents the Boltzmann constant (\(1.38 \times 10^{-23}\) J/K), \(T_{\textrm{eff}}\) represents the publicly-agreed-upon effective temperature, \(R_{\textrm{p}}\) represents the parallel combination of Alice’s and Bob’s chosen resistors, given by

where \(R_{\textrm{A}}\) represents Alice’s resistor choice and \(R_{\textrm{B}}\) represents Bob’s resistor choice, and \(\Delta f_{\textrm{B}}\) represents the noise bandwidth of the generators.

Four possible resistance combinations can be formed by Alice and Bob: HH, LL, LH, and HL. Using the Johnson Formula, these correspond to three mean-square voltages, as shown in Fig. 3. The HH and LL cases are insecure situations because they render a distinct mean-square voltage; these bits are discarded by Alice and Bob. The LH and HL cases, on the other hand, are secure situations because they render the exact same mean-square voltage, thus an adversary cannot differentiate between the two situations; however, Alice and Bob know which resistor they have chosen.

The three mean-square voltage levels. The HH and LL cases represent insecure situations because they form distinct mean-square voltages. The HL and LH cases represent secure bit exchange because Eve cannot distinguish between the corresponding two resistance situations (HL and LH). On the other hand, Alice and Bob can determine the resistance at the other end because they know their own connected resistance value17,18,19,37.

We typically represent the LH case as the bit value “0” and the HL as the bit value “1”38,88. Over the course of several BEPs, Alice and Bob generate a secure binary key, or random string of bits (see Section Decentralized Identity). All binary keys can be converted into a hexadecimal representation, thus we believe that a system that utilizes hex keys can be driven by converting the base of the original binary keys. In the present paper, we explore a proof of concept involving the utilization of the statistical physical phenomena of the KLJN scheme to provide secure keys to drive a DID credentialing system that we created2.

Security analysis

CSPRNGs generate pseudorandom sequences deterministically from an initial seed. While widely used, their security fundamentally depends on the seed’s secrecy and unpredictability. If the seed or algorithm is compromised or weak, the pseudorandom outputs become predictable, enabling attacks such as seed recovery and RNG exploits20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28.

In contrast, the KLJN scheme derives its randomness from physical noise sources–specifically, thermal noise governed by the fluctuation dissipation theorem112. This approach provides true randomness that is not algorithmically reproducible, offering foundational information-theoretic security impervious to RNG-related attacks17,19,37. Additionally, KLJN’s reliance on simple hardware components avoids the computational overhead typical of CSPRNGs, making it especially suitable for resource-constrained environments.

Although the KLJN key exchange scheme is information-theoretically secure based on the second law of thermodynamics, practical implementations face challenges. These attacks include cable capacitance effects, current injection, transient response exploitation, and electromagnetic or thermal side-channel leakage. However, extensive research has proposed defense protocols and hardware design optimizations to mitigate these vulnerabilities17,18,19,37,38,39,40,41,75,76,77,78,79,81,82,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,113,114,115. For instance, cable capacitance effects can be neutralized via matched filtering and shielded cable design81, while current injection attacks are countered by real-time monitoring of current and voltage levels79. Our implementation aligns with these secure design principles, ensuring that the practical system retains the unconditional security characteristics of the ideal KLJN setup.

Our KLJN implementation builds upon extensive research demonstrating that both ideal and practical KLJN systems achieve unconditional security through tailored defense protocols. Practical attacks such as cable capacitance, current injection, and transient signal attacks have been studied thoroughly. Proposed countermeasures include balanced cable designs, real-time monitoring of current and voltage waveforms, and transient signal filtering to prevent leakage of information. Importantly, even in scenarios where a minor information leak might occur, privacy amplification techniques–shortening the raw key to a smaller, more secure key–can be applied to maintain unconditional security at the cost of reduced bit rate53,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123. These combined strategies uphold the theoretical security foundations under practical non-ideal conditions, ensuring robust protection in real-world environments.

The primary scientific and engineering contribution of this work lies in addressing a critical security gap in decentralized identity systems: the reliance on insecure pseudorandom key generation mechanisms. While the KLJN key exchange scheme itself is established, its integration as a physical-layer entropy source for real-world DID protocols (e.g., Veramo) provides a novel, testable approach to achieving information-theoretic key security–previously unaddressed in DID systems. This integration showcases a methodology to reliably generate cryptographic keys grounded in fundamental physical randomness rather than deterministic computations, thereby reducing the attack surface for identity forgery and impersonation. Our experimental results validate this integration’s feasibility and highlight the potential for wider adoption of physical-layer security primitives in emerging decentralized identity systems. Hence, beyond a software integration, the work proposes and experimentally validates a new security primitive in DID that advances the field both scientifically and practically.

Our impact

This work makes the following contributions:

-

Introduces the KLJN scheme as a physical entropy source for generating DIDs in a decentralized framework.

-

Demonstrates end-to-end integration of KLJN-generated keys with Veramo and Ethereum, showing that DID creation can be driven entirely by physical randomness instead of pseudorandom seeds.

-

Provides statistical validation of KLJN-generated 256-bit keys using established test suites and compares qualitative performance characteristics with conventional CSPRNG and ECC-based methods.

-

Discusses how KLJN-based key generation can reduce attack surfaces associated with seed compromise and RNG weaknesses in decentralized identity systems.

The rest of this paper is as follows. In the following section, we describe the methodology. Then, we demonstrate the KLJN-powered identifier and compare its performance to conventional cryptographic schemes. Finally, we conclude this paper.

Methodology

Alice and Bob randomly select one of their resistors, \(R_{\textrm{H}}\) or \(R_{\textrm{L}}\), to connect to the wire (see Section The KLJN Scheme). If both communicating parties chose \(R_{\textrm{H}}\) or \(R_{\textrm{L}}\) (i.e. the HH or the LL case), we discard the bit; however, in the secure bit situations where Alice chose \(R_{\textrm{H}}\) and Bob chose \(R_{\textrm{L}}\) (the HL case), or where Alice chose \(R_{\textrm{L}}\) and Bob chose \(R_{\textrm{H}}\) (the LH case), we keep the bit.

Alice and Bob undergo as many BEPs as needed to produce a secure binary key of a fixed length L. We employ base conversion to convert the binary key to its respective hexadecimal representation, which contains \(\frac{1}{4}L\) characters. We then use the resulting hex key to generate a DID for a single user and append the DID to an Ethereum blockchain.

Demonstration

Statistical key generation

Johnson noise emulation

Footnote 2First, we numerically generated Gaussian band-limited white noise (GBLWN) in MATLAB, taking care to mitigate aliasing, improve Gaussianity, and reduce short-term bias. We created a long sequence of Gaussian samples using the built-in randn() function, and several independent realizations were averaged to obtain a single time series with improved statistical properties. This series was then transformed to the frequency domain by a fast Fourier transform (FFT), zero-padded to enforce Nyquist-compatible sampling and suppress aliasing, and finally brought back to the time domain via an inverse FFT. The real part of this inverse-transformed signal served as the band-limited, anti-aliased noise time series used in the simulations. The methodology follows the approach originally detailed in3, with parameter choices adjusted for the present work.

The probability plot of the generated noise is shown in Fig. 4, showing that the noise is Gaussian. Figure 5 demonstrates that the noise has a band-limited, white power density spectrum and that it is anti-aliased.

From the Nyquist Sampling Theorem,

where \(\tau\) represents the time step, an \(\Delta f_{\textrm{B}}\) of 500 Hz renders a time step of \(10^{-3}\) seconds (i.e., a sampling frequency \(f_s\) of 10 kHz).

The resulting normalized Gaussian noise was scaled to emulate Johnson noise for the target resistance, bandwidth, and effective temperature. In this study we chose \(R_{\textrm{H}}=100\) k\(\Omega\), \(R_{\textrm{L}} = 10\) k\(\Omega\), noise bandwidth \(\Delta f_{\textrm{B}}=500\) Hz, and effective temperature \(T_{\textrm{eff}} = 10^{18}\) K, consistent with established KLJN simulation practices.

A realization of Alice’s and Bob’s noise voltages over 100 milliseconds is displayed in Fig. 6. \(U_{\textrm{H,A}}(t)\) is the noise voltage of Alice’s \(R_{\textrm{H}}\), \(U_{\textrm{L,A}}(t)\) is the noise voltage of Alice’s \(R_{\textrm{L}}(t)\), \(U_{\textrm{H,B}}(t)\) is the noise voltage of Bob’s \(R_{\textrm{H}}(t)\), and \(U_{\textrm{L,B}}(t)\) is the noise voltage of Bob’s \(R_{\textrm{L}}(t)\) (see Fig. 2). Each time step is one millisecond17,18,19,37.

Bit exchange

To emulate resistor selection by Alice and Bob during each BEP, we used the MATLAB randi function to draw independent binary values for each party. A value of 0 was mapped to \(R_{\textrm{L}}\) and a value of 1 to \(R_{\textrm{H}}\). When both parties chose the same resistor (HH or LL cases), the corresponding bit was treated as insecure and discarded. When the parties selected different resistors (HL or LH cases), the bit was accepted as secure and retained for the key, since an eavesdropper cannot distinguish between these two configurations based on the observed mean-square noise voltage.

Using this procedure, we simulated repeated BEPs until a key of length \(L = 256\) bits was obtained (i.e., 256 bit exchanges). The resulting binary key was then converted to a hexadecimal representation of length \(\frac{L}{4}= 64\) characters for use in the decentralized identity pipeline.

DID setup

Footnote 3We implemented the decentralized identity layer using the Veramo framework, which provides modular, open-source components for creating and managing DIDs and verifiable credentials35,36. Veramo’s plugin-based architecture allowed us to integrate a custom key management workflow while reusing standardized DID resolution and credential interfaces. Conceptually, our integration consists of three steps: (i) ingesting a KLJN-generated 256-bit binary key and converting it to a 64-character hexadecimal string, (ii) registering this hexadecimal key as the primary key material in Veramo’s key management system, and (iii) using Veramo’s DID provider for Ethereum (ethr-did) to derive and publish a corresponding DID document on the target network. Transport-level security between the DID agent and backend services is handled using TLS via OpenSSL libraries, ensuring that message exchange is cryptographically protected in addition to the physical-layer key generation.

To harden transport security between components, we coupled the Veramo agent with OpenSSL libraries, following configuration patterns from the official OpenSSL repository. This ensured that communication between the web server, DID agent, and backing services remained protected by widely-used TLS mechanisms in addition to the KLJN-based key generation32.

The practical steps to deploy the demonstrator involved setting up a Node.js application, installing the required Veramo packages (via yarn), configuring an agent with Ethereum-compatible DID providers, and wiring the KLJN-derived hexadecimal key into Veramo’s key management system. The overall DID lifecycle and credential issuance flow build on our earlier Web 3.0 DID prototype in, where further implementation details are available, but are extended here to accept physically generated keys from the KLJN scheme.

Key integration

In order for Veramo to be able to properly read the KLJN-generated key, we created the “binaryToHex” function to regroup every four binary digits into a single hexadecimal character. Then, we input the resulting hex key into Veramo’s Key Management System, and we created an identifier by entering the command “yarn ts-node –esm ./src/create-identifier.ts”2. An example of a resulting DID is displayed in Fig. 7. The identifier has a unique DID string that is associated with a key pair. The identifier also contains Ethereum-specific signing functions such as “ES256K”, “ES256K-R” , and “eth_signTransaction that define how the keys can be used for transactions and interactions on the Ethereum blockchain.

Randomness and statistical validation

To rigorously evaluate the statistical properties of KLJN-generated keys, we followed the methodology recommended in NIST SP 800-22 Rev. 1a124. We generated \(N=100\) independent binary sequences, each of length \(10^6\) bits, using the KLJN simulation described in the Methodology section. For each sequence we applied the full set of 15 NIST SP 800-22 tests at a significance level \(\alpha = 0.01\).

For each test, we computed (i) the proportion of sequences whose individual p-values exceeded 0.01 and (ii) a second-level p-value assessing the uniformity of the p-value distribution across sequences, as prescribed in SP 800-22. The acceptable interval for the passing proportion was taken as \((1-\alpha )\pm 3\sqrt{\frac{\alpha (1-\alpha )}{N}}\), following NIST’s recommendation124. All tests produced passing proportions within this interval, and all second-level p-values exceeded 0.0001, indicating no statistically significant deviation from the ideal uniform distribution of p-values.

Table 1 summarizes the results across all 15 tests. These findings show that long KLJN-generated bit streams satisfy the standard statistical criteria for cryptographic-grade randomness, complementing the information-theoretic security guarantees derived from the physical model.

Our results demonstrate that the long KLJN-generated bit streams generated by the KLJN scheme consistently pass all critical tests within these suites, confirming their suitability for cryptographic applications. This statistical validation reinforces the physical security guarantees by confirming the randomness quality of the generated keys.

Performance comparison

The KLJN scheme exhibits key generation rates that typically range from several hundred bits per second to tens of kilobits per second depending on system configuration and component quality51. Its core operation leverages elementary electronic components (e.g., resistors, switches) that are inherently low-cost and readily integrable into simple hardware modules. This results in negligible computational overhead and energy consumption compared to conventional cryptographic methods.

In contrast, elliptic curve cryptography (ECC) relies on computationally intensive mathematical operations such as scalar multiplication, point addition, and doubling on elliptic curve points. These operations generally require dedicated processors or specialized hardware like FPGAs, consuming considerable power and increasing latency125,126,127,128,129,130,131. While ECC is more efficient than older public-key approaches, its energy consumption remains significant enough to impact resource-constrained devices such as IoT endpoints or embedded systems. Consequently, the KLJN method offers a distinct advantage in scenarios demanding both strong information-theoretic security and low energy footprint.

This distinction is particularly critical in decentralized identity systems, where devices may possess limited processing capabilities and operate in energy-sensitive environments.

Conclusion

Decentralized identity ecosystems depend on secure keys to function. Such keys are represented in hexadecimal, and they rely on computational algorithms for production. We showed that such keys can be generated in the absence of a computer, i.e. with statistical physical means. Since the keys are truly random, they are immune to vulnerabilities involving computational knowledge. We can then employ a base conversion algorithm and use the output to create a DID that was appended to an Ethereum blockchain.

This work was carried out on a local client-server network for a single user. Future work would involve integration on a cloud server and mass scalability of the KLJN scheme to make it accessible for multiple users.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript. Original files are available upon request. Christiana Chamon Garcia (ccgarcia@vt.edu) is the point of contact for requesting data.

Notes

This Johnson-noise emulation procedure follows the method originally described in3, with parameter values adjusted for the present study.

References

Flanery, S. A., Chamon, C., Kotikela, S. D. & Quek, F. K. Web 3.0 and the ownership of learning. In The Fifth IEEE International Conference on Trust, Privacy and Security in Intelligent Systems, and Applications, TPS ’23, https://doi.org/10.1109/TPS-ISA58951.2023.00016 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 2023). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Flanery, S. A., Mohanasundar, K., Chamon, C., Kotikela, S. D. & Quek, F. K. Web 3.0 and a decentralized approach to education. arXiv preprint https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2312.12268 (2023). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Ferdous, S., Chamon, C. & Kish, L. B. Comments on the generalized kljn key exchanger with arbitrary resistors: Power, impedance, security. Fluct. Noise Lett. 20, 2130002. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477521300020 (2021).

Nath, K., Dhar, S. & Basishtha, S. Web 1.0 to web 3.0 - evolution of the web and its various challenges. In International Conference on Reliability Optimization and Information Technology (ICROIT), 86–89, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICROIT.2014.6798297 (Faridabad, India, 2014). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Alabdulwahhab, F. A. Web 3.0: The decentralized web blockchain networks and protocol innovation. In IEEE International Conference on Cloud Computing and Big Data Analysis (ICCCBDA), 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCCBDA.2016.7529541 (Chengdu, China, 2016). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Zheng, Z., Xie, S., Dai, H., Chen, X. & Wang, H. An overview of blockchain technology: Architecture, consensus, and future trends. In 2017 IEEE International Congress on Big Data (BigData Congress), 557–564, https://doi.org/10.1109/BigDataCongress.2017.85 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Honolulu, Hawaii, USA, 2017). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Turner, S. Transport layer security. IEEE Internet Comput. 18, 60–63. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIC.2014.126 (2014).

Zhao, X. & Si, Y. W. Nftcert: Nft-based certificates with online payment gateway. In 2021 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain (Blockchain), 538–543, https://doi.org/10.1109/Blockchain53845.2021.00081 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Melbourne, Australia, 2021). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Enikolopov, R., Petrova, M. & Sonin, K. Social media and corruption. Am. Econ. J.: Appl. Econ. 10, 150–174. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20160089 (2018).

Decentralized identifiers (dids) v1.0. https://www.w3.org/TR/did-core/. (Accessed: Dec. 16, 2023).

European digital identity: Council and parliament reach a provisional agreement on eid (2023). https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2023/11/08/european-digital-identity-council-and-parliament-reach-a-provisional-agreement-on-eid/. (Accessed: Dec. 16, 2023).

Decentralized identity and access management of cloud for security as a service, https://doi.org/10.1109/COMSNETS53615.2022.9668529. (Accessed: Dec. 16, 2023).

Xian, J., You, L., Yi, Q., Wang, J. & Hu, G. A survey on decentralized identity management systems. Comput. Sci. Rev. 58, 100811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosrev.2025.100811 (2025).

Li, Z. Z. et al. Disims: A distributed identity management system via blockchain. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing 1–16, https://doi.org/10.1109/TDSC.2025.3624710 (2025). (Accessed: Dec. 17, 2025).

Deng, H. et al. Futuredid: A fully decentralized identity framework with multi-party verification. IEEE Trans. Comput. 73, 2051–2065. https://doi.org/10.1109/TC.2024.3398509 (2024).

Lim, S. Y., Musa, O., Al-rimy, B. & Almasri, A. Trust models for blockchain-based self-sovereign identity management: A survey and research directions. In Blockchain Applications, 277–302, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-93646-4_13 (Springer, 2022). (Accessed: Dec. 17, 2025).

Chamon, C., Ferdous, S. & Kish, L. B. Random number generator attack against the kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise secure key exchange protocol. arXiv preprint https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2005.10429 (2020). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Chamon, C. Random Number Generator, Zero-Crossing, and Nonlinearity Attacks Against the Kirchhoff-Law-Johnson-Noise (KLJN) Secure Key Exchange Protocol. Ph.D. thesis, Texas A&M University (2022).arxiv:2112.09052. (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Chamon, C., Ferdous, S. & Kish, L. B. Statistical random number generator attack against the kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise (kljn) secure key exchange protocol. Fluct. Noise Lett. 21, 2250027. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477522500274 (2022).

Alhassan, I. Z., Abdul-Salaam, G., Asante, M., Missah, Y. M. & Shirazu, A. S. An overview and comparative study of traditional, chaos-based and machine learning approaches in pseudorandom number generation. Journal of Cyber Security (JCS) 7, https://doi.org/10.32604/jcs.2025.063529 (2025). (Accessed: Dec. 17, 2025).

Saini, A., Tsokanos, A. & Kirner, R. Quantum randomness in cryptography-a survey of cryptosystems, rng-based ciphers, and qrngs. Information 13, 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/info13080358 (2022).

Cohney, S. N., Green, M. D. & Heninger, N. Practical state recovery attacks against legacy rng implementations. Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security 265–280, https://doi.org/10.1145/3243734.3243756 (2018). (Accessed: Dec. 17, 2025).

Vennos, A., George, K. & Michaels, A. Attacks and defenses for single-stage residue number system prngs. IoT 2, 375–400. https://doi.org/10.3390/iot2030020 (2021).

Matthew, B., Idowu, M., Koc, V. & Kaushik, T. Role of secure random number generation in messaging security. (2025). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/394864658_Role_of_Secure_Random_Number_Generation_in_Messaging_Security. (Accessed: Dec. 17, 2025).

Naumenko, M. Cryptographically Secure Pseudorandom Number Generators. Master’s thesis, Charles University, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Prague, Czech Republic (2024). Diploma thesis defended on 6 September 2024. Accessed: Dec. 17, 2025, https://dspace.cuni.cz/handle/20.500.11956/193197.

Kietzmann, P., Schmidt, T. C. & Wählisch, M. A guideline on pseudorandom number generation (prng) in the iot. ACM Computing Surveys54, 112:1–112:38, https://doi.org/10.1145/3453159 (2021). (Accessed: Dec. 17, 2025).

Safoev, N. & Fayziraxmonov, B. Secure randomness in modern operating systems: An analysis of rng architectures in windows, linux, and macos/ios. Zamonaviy Dunyo Ilmi Va Texnologiyalari (ZDIT) 4, 105–113. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15637151 (2025).

Martínez, E. & Lammer, S. An examination of various random number generator weaknesses. Tech. Rep., eComai KGolf Labs (2023). Cryptanalysis ST 2023 report. https://ls.ecomaikgolf.com/slides/randomnumbers/report.pdf. (Accessed: Dec. 17, 2025).

ethr-did. https://developer.uport.me/ethr-did/docs/guides/index. (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

secp256k1. https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Secp256k1. (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Elliptic curve digital signature algorithm. https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/Elliptic_Curve_Digital_Signature_Algorithm. (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Digitize your diplomas, certificates and micro-certifications on the blockchain. https://www.bcdiploma.com/en. (Accessed: Dec. 16, 2023).

openssl/openssl (2021). https://github.com/openssl/openssl. (Accessed: Dec. 16, 2023)

Dahill-Brown, S. E., Witte, J. F. & Wolfe, B. Income and access to higher education: Are high quality universities becoming more or less elite? a longitudinal case study of admissions at uw-madison. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 2, 69–89, https://doi.org/10.7758/RSF.2016.2.1.04 (2016). (Accessed: Dec. 16, 2023).

Introduction | performant and modular apis for verifiable data and ssi. https://veramo.io/docs/basics/introduction. (Accessed: Dec. 16, 2023).

Update did document | performant and modular apis for verifiable data and ssi. https://veramo.io/docs/react_native_tutorials/react_native_5_update_did_document/. (Accessed: Dec. 16, 2023).

Chamon, C., Ferdous, S. & Kish, L. B. Deterministic random number generator attack against the kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise secure key exchange protocol. Fluct. Noise Lett. 20, 2150046, https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477521500462 (2021). arxiv:2012.02848. (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Melhem, M. Y., Chamon, C., Ferdous, S. & Kish, L. B. Alternating (ac) loop current attacks against the kljn secure key exchange scheme. Fluct. Noise Lett. 20, 2150050. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477521500504 (2020).

Chamon, C. & Kish, L. B. Perspective—on the thermodynamics of perfect unconditional security. Appl. Phys. Lett. 119, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0057764 (2021). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Ferdous, S., Chamon, C. & Kish, L. B. Current injection and voltage insertion attacks against the vmg-kljn secure key exchanger. Fluct. Noise Lett.22, 2350009. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477523500098 (2023).

Chamon, C. & Kish, L. B. Nonlinearity attack against the kirchhoff–law–johnson-noise (kljn) secure key exchange protocol. Fluct. Noise Lett. 21, 2250020, https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477522500201 (2022). arxiv:2108.09370. (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Kish, L. B. The Kish Cypher (WORLD SCIENTIFIC, 2017). https://www.worldscientific.com/doi/pdf/10.1142/8707.

Kish, L. B. Totally secure classical communication utilizing johnson (-like) noise and kirchhoff’s law. Physics Letters A 352, 178–182, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physleta.2005.11.062arxiv:physics/0509136 (2006). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Cho, A. Simple noise may stymie spies without quantum weirdness. Science 309, 2148. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.309.5744.2148b (2005).

Kish, L. B. & Granqvist, C. G. On the security of the kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise (kljn) communicator. Quantum Inf. Process.13, 2213–2219, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11128-014-0729-7arxiv:1309.4112 (2014). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Kish, L. B. Enhanced secure key exchange systems based on the johnson-noise scheme. Metrol. Meas. Syst. 20, 191–204, https://doi.org/10.2478/mms-2013-0017arxiv:1302.3901 (2013). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Kish, L. B. & Horvath, T. Notes on recent approaches concerning the kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise based secure key exchange. Phys. Lett. A 373, 2858–2868, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physleta.2009.05.077arxiv:0903.2071 (2009). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Vadai, G., Mingesz, R. & Gingl, Z. Generalized kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise (kljn) secure key exchange system using arbitrary resistors. Sci. Rep. 5, 13653, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13653arxiv:1506.00950 (2015). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Kish, L. B. & Granqvist, C. G. Random-resistor-random-temperature kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise (rrrt-kljn) key exchange. Metrol. Meas. Syst. 23, 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1515/mms-2016-0007 (2016).

Smulko, J. Performance analysis of the ‘intelligent’ kirchhoff’s-law-johnson-noise secure key exchange. Fluct. Noise Lett. 13, 1450024. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477514500242 (2014).

Mingesz, R., Gingl, Z. & Kish, L. B. Johnson(-like)-noise-kirchhoff-loop based secure classical communicator characteristics, for ranges of two to two thousand kilometers, via model-line. Phys. Lett. A 372, 978–984, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physleta.2007.07.086arxiv:physics/0612153 (2008). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Mingesz, R., Vadai, G. & Gingl, Z. Unconditional security by the laws of classical physics. Metrol. Meas. Syst. 20, 3–16. https://doi.org/10.2478/mms-2013-0001 (2013).

Horvath, T., Kish, L. B. & Scheuer, J. Effective privacy amplification for secure classical communications. Europhys. Lett. 94, 28002. https://doi.org/10.1209/0295-5075/94/28002 (2011).

Saez, Y. & Kish, L. B. Errors and their mitigation at the kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise secure key exchange. PLoS ONE 8, e81103. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081103 (2013).

Mingesz, R., Vadai, G. & Gingl, Z. What kind of noise guarantees security for the kirchhoff-loop-johnson-noise key exchange?. Fluct. Noise Lett. 13, 1450021. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477514500217 (2014).

Saez, Y., Kish, L. B., Mingesz, R., Gingl, Z. & Granqvist, C. G. Current and voltage based bit errors and their combined mitigation for the kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise secure key exchange. J. Comput. Electron. 13, 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10825-013-0515-2 (2014).

Saez, Y., Kish, L. B., Mingesz, R., Gingl, Z. & Granqvist, C. G. Bit errors in the kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise secure key exchange. Int. J. Mod. Phys.: Conference Series 33, 1460367. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2010194514603676 (2014).

Gingl, Z. & Mingesz, R. Noise properties in the ideal kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise secure communication system. PLoS ONE 9, e96109. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096109 (2014).

Liu, P. L. A key agreement protocol using band-limited random signals and feedback. IEEE J. Light. Technol. 27, 5230–5234. https://doi.org/10.1109/JLT.2009.2031421 (2009).

Kish, L. B. & Mingesz, R. Totally secure classical networks with multipoint telecloning (teleportation) of classical bits through loops with johnson-like noise. Fluct. Noise Lett. 6, C9–C21. https://doi.org/10.1142/S021947750600332X (2006).

Kish, L. B. Methods of using existing wire lines (power lines, phone lines, internet lines) for totally secure classical communication utilizing kirchoff’s law and johnson-like noise. arXiv preprint https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.physics/0610014 (2006). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Kish, L. B. & Peper, F. Information networks secured by the laws of physics. IEICE Trans. Commun. E95-B, 1501–1507, https://doi.org/10.1587/transcom.E95.B.1501 (2012). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Gonzalez, E., Kish, L. B., Balog, R. S. & Enjeti, P. Information theoretically secure, enhanced johnson noise based key distribution over the smart grid with switched filters. PLoS ONE 8, e70206. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0070206 (2013).

Gonzalez, E., Kish, L. B. & Balog, R. S. Encryption key distribution system and method. U.S. Patent. https://patents.google.com/patent/US9270448B2. (2016). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Gonzalez, E., Balog, R. S., Mingesz, R. & Kish, L. B. Unconditional security for the smart power grids and star networks. In 23rd Int. Conf. Noise and Fluctuations (ICNF 2015), https://doi.org/10.1109/ICNF.2015.7288626 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2015). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Gonzalez, E., Balog, R. S. & Kish, L. B. Resource requirements and speed versus geometry of unconditionally secure physical key exchanges. Entropy 2010–2014, https://doi.org/10.3390/e17042010 (2015). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Gonzalez, E. & Kish, L. B. Key exchange trust evaluation in peer-to-peer sensor networks with unconditionally secure key exchange. Fluct. Noise Lett. 1650008, https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477516500085 (2016). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Kish, L. B. & Saidi, O. Unconditionally secure computers, algorithms and hardware, such as memories, processors, keyboards, flash and hard drives. Fluct. Noise Lett. L95–L98, https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477508004362 (2008). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Kish, L. B., Entesari, K., Granqvist, C. G. & Kwan, C. Unconditionally secure credit/debit card chip scheme and physical unclonable function. Fluct. Noise Lett. 16, 1750002. https://doi.org/10.1142/S021947751750002X (2017).

Kish, L. B. & Kwan, C. Physical unclonable function hardware keys utilizing kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise secure key exchange and noise-based logic. Fluct. Noise Lett. 12, 1350018. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477513500181 (2013).

Saez, Y. & Kish, L. B. Securing vehicle communication systems by the kljn key exchange protocol. Fluct. Noise Lett. 13, 1450020. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477514500205 (2014).

Cao, X., Saez, Y., Pesti, G. & Kish, L. B. On kljn-based secure key distribution in vehicular communication networks. Fluct. Noise Lett. 14, 1550008. https://doi.org/10.1142/S021947751550008X (2015).

Kish, L. B. & Granqvist, C. G. Enhanced usage of keys obtained by physical, unconditionally secure distributions. Fluct. Noise Lett. 14, 1550007. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477515500078 (2015).

Liu, P. L. A complete circuit model for the key distribution system using resistors and noise sources. Fluct. Noise Lett. 19, 2050012. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477520500121 (2020).

Melhem, M. Y. & Kish, L. B. Generalized dc loop current attack against the kljn secure key exchange scheme. Metrol. Meas. Syst. 26, 607–616, https://doi.org/10.24425/mms.2019.129576 (2019). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Melhem, M. Y. & Kish, L. B. A static-loop-current attack against the kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise (kljn) secure key exchange system. Appl. Sci. 9, 666. https://doi.org/10.3390/app9040666 (2019).

Melhem, M. Y. & Kish, L. B. The problem of information leak due to parasitic loop currents and voltages in the kljn secure key exchange scheme. Metrol. Meas. Syst. 26, 37–40, https://doi.org/10.24425/mms.2019.126335 (2019). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Liu, P. L. Re-examination of the cable capacitance in the key distribution system using resistors and noise sources. Fluct. Noise Lett. 16, 1750025. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477517500250 (2017).

Chen, H. P. & Kish, L. B. Current injection attack against the kljn secure key exchange. Metrol. Meas. Syst. 23, 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1515/mms-2016-0025 (2016).

Vadai, G., Gingl, Z. & Mingesz, R. Generalized attack protection in the kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise key exchanger. IEEE Access 4, 1141–1147. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2016.2544442 (2016).

Chen, H. P., Gonzalez, E., Saez, Y. & Kish, L. B. Cable capacitance attack against the kljn secure key exchange. Information 719–732, https://doi.org/10.3390/info6040719 (2015). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Kish, L. B. & Granqvist, C. G. Elimination of a second-law-attack, and all cable-resistance-based attacks, in the kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise (kljn) secure key exchange system. Entropy 16, 5223–5231. https://doi.org/10.3390/e16105223 (2014).

Kish, L. B. & Scheuer, J. Noise in the wire: The real impact of wire resistance for the johnson (-like) noise based secure communicator. Phys. Lett. A 2140–2142, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physleta.2010.03.021 (2010). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Hao, F. Kish’s key exchange scheme is insecure. IEE Proceedings - Information Security 141–142, https://doi.org/10.1049/ip-ifs:20060068 (2006). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Kish, L. B. Response to feng hao’s paper ”kish’s key exchange scheme is insecure”. Fluct. Noise Lett. C37–C41, https://doi.org/10.1142/S021947750600363X (2006). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Kish, L. B. Protection against the man-in-the-middle-attack for the kirchhoff-loop-johnson (-like)-noise cipher and expansion by voltage-based security. Fluct. Noise Lett. L57–L63, https://doi.org/10.1142/9789811252143_0056 (2006). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Gunn, L. J., Allison, A. & Abbott, D. A new transient attack on the kish key distribution system. IEEE Access 1640–1648, https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2015.2480422 (2015). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Ferdous, S. & Kish, L. B. Transient attacks against the kirchhoff–law–johnson–noise (kljn) secure key exchanger. Appl. Phys. Lett. 143503, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0146190 (2023). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Kish, L. B. & Granqvist, C. G. Comments on ”a new transient attack on the kish key distribution system”. Metrol. Meas. Syst. 321–331, https://doi.org/10.1515/mms-2016-0039 (2015). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Gunn, L. J., Allison, A. & Abbott, D. A directional wave measurement attack against the kish key distribution system. Sci. Rep. 6461, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep06461 (2014). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Chen, H. P., Kish, L. B., Granqvist, C. G. & Schmera, G. On the “cracking” scheme in the paper “a directional coupler attack against the kish key distribution system” by gunn, allison and abbott. Metrol. Meas. Syst. 21, 389–400, https://doi.org/10.2478/mms-2014-0033arxiv:1405.2034 (2014). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Chen, H. P., Kish, L. B., Granqvist, C. G. & Schmera, G. Do electromagnetic waves exist in a short cable at low frequencies? what does physics say?. Fluct. Noise Lett. 13, 1450016. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477514500163 (2014).

Kish, L. B. et al. Analysis of an attenuator artifact in an experimental attack by gunn–allison–abbott against the kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise (kljn) secure key exchange system. Fluct. Noise Lett. 1550011, https://doi.org/10.1142/S021947751550011X (2015). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Chamon, C. Thermod communication: Low power or hot air? Fluct. Noise Lett. 2540006, https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477525400061. (Accessed: Dec. 17,2025).

Flanery, S. A., Trapani, A., Chamon, C. & Nazhandali, L. Duality on the thermodynamics of the kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise (kljn) secure key exchange scheme. Fluct. Noise Lett. 0, 2540005, https://doi.org/10.1142/S021947752540005X (2025).

Gilani, K., Bertin, E., Hatin, J. & Crespi, N. A survey on blockchain-based identity management and decentralized privacy for personal data. In 2020 2nd Conference on Blockchain Research & Applications for Innovative Networks and Services (BRAINS), 97–101, https://doi.org/10.1109/BRAINS49436.2020.9223312 (2020). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Alanzi, H. & Alkhatib, M. Towards improving privacy and security of identity management systems using blockchain technology: A systematic review. Appl. Sci.12, https://doi.org/10.3390/app122312415 (2022). (Accessed: Dec. 22,2023).

Anasuri, S., Rusum, G. P. & Pappula, K. K. Blockchain-based identity management in decentralized applications. International Journal of AI, Big Data, Computing and Management Studies3, 70–81, https://doi.org/10.63282/3050-9416.IJAIBDCMS-V3I3P109 (2022). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Cao, Y. & Yang, L. A survey of identity management technology. In 2010 IEEE International Conference on Information Theory and Information Security, 287–293, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICITIS.2010.5689468 (2010). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Goel, A. & Rahulamathavan, Y. A comparative survey of centralised and decentralised identity management systems: Analysing scalability, security, and feasibility. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Future Internet (FiCloud), 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1109/FiCloud58648.2023.00011 (2023). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Dib, O. & Toumi, K. Decentralized identity systems: Architecture, challenges, solutions and future directions. Annals of Emerging Technologies in Computing (AETiC) 4, 19–40, https://doi.org/10.33166/AETiC.2020.05.002 (2020). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Buttar, A. M., Shahid, M. A., Arshad, M. N. & Akbar, M. Decentralized identity management using blockchain technology: Challenges and solutions. In Blockchain Applications - Transforming Industries, Enhancing Security, and Addressing Ethical Considerations, 131–166, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-45028-0_6 (Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2024). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Ahmed, M. R., Islam, A. K. M. M., Shatabda, S. & Islam, S. Blockchain-based identity management system and self-sovereign identity ecosystem: A comprehensive survey. IEEE Access 10, 113436–113481. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2022.3216643 (2022).

Siddiqui, S. T., Ahmad, R., Shuaib, M. & Alam, S. Blockchain security threats, attacks and countermeasures. In Hu, Y.-C., Tiwari, S., Trivedi, M. C. & Mishra, K. K. (eds.) Ambient Communications and Computer Systems, vol. 1097 of Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, 51–62, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-1518-7_5 (Springer Singapore, Singapore, 2020).

Sani, A. S., Yuan, D., Meng, K. & Dong, Z. Y. Idenx: A blockchain-based identity management system for supply chain attacks mitigation in smart grids. In 2020 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1109/PESGM41954.2020.9281929 (2020). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Alsunbul, A., Elmedany, W. & Al-Ammal, H. Blockchain application in healthcare industry: Attacks and countermeasures. In 2021 International Conference on Data Analytics for Business and Industry (ICDABI), 621–629, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDABI53623.2021.9655852 (2021). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Guggenberger, T., Schlatt, V., Schmid, J. & Urbach, N. A structured overview of attacks on blockchain systems. In Proceedings of the 25th Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems (PACIS 2021), 100 https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2021/100 (2021). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Pöhn, D., Grabatin, M. & Hommel, W. Analyzing the threats to blockchain-based self-sovereign identities by conducting a literature survey. Appl. Sci. 14, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/app14010139 (2024).

Shakib, K. H., Rahman, M., Islam, M. & Chowdhury, M. Impersonation attack using quantum shor’s algorithm against blockchain-based vehicular ad-hoc network. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 26, 6530–6544. https://doi.org/10.1109/TITS.2025.3534656 (2025).

Johnson, J. B. Thermal agitation of electricity in conductors. Phys. Rev. 32, 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.32.97 (1928).

Por, E., van Kooten, M. & Sarkovic, V. Nyquist–shannon sampling theorem. Tech. Rep., Leiden University, Faculty of Science. AOT 2019 exercise sheet/explanation document. https://home.strw.leidenuniv.nl/~por/AOT2019/docs/AOT2019Ex13NyquistTheorem.pdf. (2019). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Kubo, R. The fluctuation-dissipation theorem. Rep. Prog. Phys. 29, 255–284. https://doi.org/10.1088/0034-4885/29/1/306 (1966).

Kish, L. B., Abbott, D. & Granqvist, C. G. Critical analysis of the bennett–riedel attack on secure cryptographic key distributions via the kirchhoff-law-johnson-noise scheme. PLoS ONE e81810, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0081810 (2013). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Chamon, C. Comment on “a kljn-based thermal noise modulation scheme with enhanced reliability for low-power iot communication”. Fluct. Noise Lett. 2650018, https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477526500185. (Accessed: Dec. 17,2025).

Chamon, C. Revisiting modulated johnson noise communication: A critical analysis of novelty and power efficiency claims in “communication by means of modulated johnson noise”. Fluct. Noise Lett. 2650017, https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219477526500173. (Accessed: Dec. 17,2025).

Bennett, C. H., Brassard, G. & Robert, J.-M. Privacy amplification by public discussion. SIAM J. Comput. 17, 210–229. https://doi.org/10.1137/0217014 (1988).

Bennett, C., Brassard, G., Crepeau, C. & Maurer, U. Generalized privacy amplification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 41, 1915–1923. https://doi.org/10.1109/18.476316 (1995).

Maurer, U. & Wolf, S. Privacy amplification secure against active adversaries. In Kaliski, B. S. (ed.) Advances in Cryptology — CRYPTO ’97, 307–321, https://doi.org/10.1007/BFb0 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1997). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Hayashi, M. Exponential decreasing rate of leaked information in universal random privacy amplification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 57, 3989–4001. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIT.2011.2110950 (2011).

Aggarwal, D., Dodis, Y., Jafargholi, Z., Miles, E. & Reyzin, L. Amplifying privacy in privacy amplification. In Garay, J. A. & Gennaro, R. (eds.) Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO 2014, 183–198, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-44381-1_11 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2014). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Chen, W.-N., Song, D., özgür, A. & Kairouz, P. Privacy amplification via compression: Achieving the optimal privacy-accuracy-communication trade-off in distributed mean estimation. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36 (NeurIPS 2023), —, https://doi.org/10.5555/3666122.3669152 (2023). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Cachin, C. & Maurer, U. M. Linking information reconciliation and privacy amplification. J. Cryptol. 10, 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001459900023 (1997).

Maurer, U. & Wolf, S. Secret-key agreement over unauthenticated public channels .ii. privacy amplification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 49, 839–851, https://doi.org/10.1109/TIT.2003.809559 (2003). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Rukhin, A. et al. A statistical test suite for random and pseudorandom number generators for cryptographic applications. Tech. Rep. 800-22 Rev. 1a, National Institute of Standards and Technology (2010). https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.800-22r1a. (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Hankerson, D., Menezes, A. & Vanstone, S. Guide to elliptic curve cryptography. Springer 75–152 https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/b97644 (2004). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Handschuh, H. & Trichina, E. Hardware security features for secure embedded devices. Vieweg. Wiesbaden 38–44 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-8348-9195-2_5 (2006).

Suárez-Albela, M., Fernández-Caramés, T. M., Fraga-Lamas, P. & Castedo, L. A practical performance comparison of ecc and rsa for resource-constrained iot devices. In 2018 Global Internet of Things Summit (GIoTS), 1–6,https://doi.org/10.1109/GIOTS.2018.8534575 (2018). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Mössinger, M. Towards. et al. IEEE 17th International Symposium on A World of Wireless. Mobile and Multimedia Networks (WoWMoM)1–6, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1109/WoWMoM.2016.7523559 (2016).

Elhajj, M. & Mulder, P. A comparative analysis of the computation cost and energy consumption of relevant curves of ecc presented in literature. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering Research 3, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.53375/ijecer.2023.318 (2023). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Vahdati, Z., Yasin, S. M., Ghasempour, A. & Salehi, M. Comparison of ecc and rsa algorithms in iot devices. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Information Technology 97, 4293–4308 https://www.jatit.org/volumes/Vol97No16/6Vol97No16.pdf (2019). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Suárez-Albela, M., Fraga-Lamas, P. & Fernández-Caramés, T. M. A practical evaluation on rsa and ecc-based cipher suites for iot high-security energy-efficient fog and mist computing devices. Sensors 18, https://doi.org/10.3390/s18113868 (2018). (Accessed: Dec. 22, 2023).

Funding

This work was completed without the use of funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C. and S.K conceived the experiment(s), K.M, S.A.F, and C.C. conducted the experiment(s), C.C. analysed the results. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohanasundar, K., Flanery, S.A., Kotikela, S. et al. Kirchhoff Law Johnson noise key generation for secure decentralized identifiers. Sci Rep 16, 4434 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34403-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34403-7