Abstract

The adoption of machine learning in the financial sector requires solutions that ensure secure data collaboration while maintaining regulatory compliance. Federated Learning (FL) offers a decentralized alternative to centralized training; however, it remains vulnerable to information leakage through gradient sharing. This study proposes a privacy-preserving FL framework for loan approval prediction and evaluates three privacy configurations: Standard FL, Differential Privacy–enabled FL (DP-FL), and Homomorphic Encryption–enabled FL (HE-FL). A real-world loan dataset distributed across five simulated clients was used to assess model performance, computational overhead, and privacy guarantees. Differential Privacy was implemented using the Gaussian mechanism, with formally computed cumulative privacy budgets (ε = 14.13, 8.65, and 5.74) derived using Rényi Differential Privacy accounting over 1000 local epochs and five communication rounds. Experimental results show that Standard FL achieved the highest accuracy (≈ 91%) but provided no confidentiality guarantees. HE-FL preserved accuracy (≈ 90%) while ensuring encrypted computation at the cost of increased overhead. DP-FL demonstrated predictable privacy–utility behaviour, where ε = 8.65 yielded the most balanced performance (≈ 87–90%) with enforceable privacy guarantees and moderate computational cost. The findings confirm that privacy-preserving FL is feasible for regulated financial applications and that privacy performance can be tuned based on operational and regulatory requirements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Credit risk prediction is vital in the financial industry, enabling institutions to assess loan default probabilities based on data like income and credit history. Machine learning has improved prediction accuracy, yet centralized training compromises data privacy—especially under strict regulations (Yang et al.1; Li et al.2. Federated Learning (FL) offers a privacy-conscious alternative by decentralizing model training. Despite its advantages, FL is susceptible to inference attacks. For example, model inversion and membership inference can extract training data, posing privacy risks (Domingo-Ferrer et al.3. Quantitatively, such attacks can recover private data with high confidence, necessitating stronger safeguards.

To mitigate these risks, we explore two methods: Differential Privacy (DP) and Homomorphic Encryption (HE). DP introduces noise into model updates, offering statistical privacy. HE enables encrypted computation, ensuring full confidentiality. A comparative analysis of these methods in the FL context reveals key trade-offs. In addition, we briefly compare FL with alternative distributed learning paradigms. Unlike FL, Split Learning partitions the model itself across clients and server, transmitting intermediate activations instead of model updates. This can reduce communication but adds model design complexity. Swarm Learning, another approach, uses block chain for decentralized control but lacks the privacy guarantees of DP or HE.

Finally, regulatory frameworks such as the GDPR and CCPA have intensified the need for privacy-preserving AI. These mandates restrict the sharing and processing of personal data, encouraging adoption of FL and techniques like DP and HE, which allow compliance without compromising model utility. This study delivers a practical and regulatory-aware perspective on enhancing FL-based credit risk models using DP and HE, balancing accuracy, privacy, and computational feasibility.

Contributions

To address these limitations, this work offers four primary contributions:

1. A deployment-oriented comparative study of three FL configurations:

Standard FL, DP-enabled FL, and CKKS-based HE-FL are evaluated using a structured loan approval dataset distributed across five simulated non-IID banking clients.

2. Complete reproducibility and privacy accounting:

The study provides full documentation of hyperparameters, cryptographic settings, Rényi DP accounting (ε, δ, clipping norm, sampling rate, and composed privacy loss), and CKKS modulus chain configurations.

3. A multidimensional performance evaluation framework:

Beyond accuracy, the study reports ROC-AUC, PR-AUC, calibration error, fairness-aware subgroup performance, runtime, and encryption overhead, offering a deployment-focused analysis.

4. Deployment implications and forward-looking design recommendations:

The discussion connects findings to operational realities in financial institutions and outlines future integration pathways involving secure aggregation, Byzantine robustness, ledger-governed coordination, and hybrid DP-HE systems.

This paper is structured to present the proposed privacy-preserving federated learning framework in a logical and coherent manner. Section 1 introduces the problem of secure credit-risk prediction, explains the need for privacy-enhancing techniques, and outlines the main contributions of the work. Section 2 summarizes existing research on Federated Learning, Differential Privacy, and Homomorphic Encryption, identifying the gaps that motivate this study. Section 3 provides essential background on DP, HE, and the secure federated workflow that underpins the proposed approach. Section 4 details the methodology, including the system architecture, model configuration, DP-SGD settings, CKKS encryption parameters, and reproducibility considerations. Section 5 presents the experimental setup, dataset distribution strategy, evaluation metrics, and comparative results for Standard FL, DP-FL, and HE-FL, followed by execution-time analysis and an ablation study on CKKS approximation. Section 6 offers the conclusion, outlines limitations, and highlights directions for future work. The paper concludes with declarations, data availability information, and references.

Related work

Federated Learning (FL) has gained substantial attention as a privacy-preserving paradigm for collaborative machine learning in sensitive domains. In financial environments, where information such as income, credit history, demographic identifiers, and behavioural attributes poses high privacy risk, secure distributed learning is essential. Seranmadevi et al.4 emphasized that AI-enabled financial infrastructures expose vulnerabilities that require alignment with regulatory expectations and risk-management practices, supporting the need for privacy-preserving FL in banking applications.

Two primary approaches dominate privacy-preserving FL research: Differential Privacy (DP) and Homomorphic Encryption (HE). DP provides theoretical privacy guarantees by injecting calibrated statistical noise into model updates. Early contributions focused on scalability and applicability in distributed settings, such as the works of Baek et al.5 and Elgabli et al.6. Subsequent improvements have focused on minimizing accuracy degradation caused by noise, including momentum-based training and gradient filtering introduced by Zhang et al.7. Additional studies such as Hu et al.8, Jin et al.9, Zheng et al.10, Chen et al.11, and Hu et al.12 explored privacy–utility trade-offs and adversarial resilience of DP in FL under realistic threat assumptions. Efficiency-aware approaches, including FL-ODP13 and FedDP-SA14, demonstrated improved inference stability, while Li et al.15 addressed adaptive client-specific privacy budgets. The formal underpinnings of DP originate from Dwork and Roth16, forming the basis of modern privacy regulation–aligned deployments.

Homomorphic Encryption has emerged as a cryptographic alternative enabling computations directly on encrypted model parameters. Notable early FL-HE frameworks include SecFed by Cai et al.17 and encrypted deep learning pipelines by Aono et al.18. Later works, including Chen et al.19, Catalfamo et al.20, and Zhang et al.21, evaluated the feasibility of HE within real-world federated settings. Hybrid schemes such as Chen et al.22 combine DP and HE to obtain stronger privacy guarantees with controlled accuracy cost. Broader HE applicability across regulated sectors is documented by Aziz et al.23 and Mehendale24. Complementary efforts, such as Chang et al.25, Gad et al.26, and Gupta et al.27, further expanded secure collaborative modelling using functional encryption, communication-efficient DP, and malicious user detection strategies.

More recently, research has evolved beyond confidentiality alone to include the dimensions of efficiency, robustness, and data heterogeneity—all critical factors for real-world deployment. Balance FL28 and FEDIC29 demonstrate that class imbalance and non-IID data substantially influence convergence and fairness in FL settings. A recent survey by Solans et al.30 reinforces the importance of non-IID-aware FL system design, providing a taxonomy of techniques addressing heterogeneity, fairness, and communication constraints. Performance optimization for encrypted FL systems has also advanced significantly. Jiang et al.31 introduced Lancelot, demonstrating that CKKS-based encrypted aggregation can be computationally optimized while defending against poisoning and Byzantine attacks. Similarly, adaptive architectures such as ArtFL and Balance FL propose resource-aware computation pathways, offering pathways to reduce computational cost under privacy constraints—an aspect relevant to DP and HE overhead observed in this work.

Despite extensive advancements, little work has conducted a direct experimental comparison of standard FL, DP-FL, and HE-FL under a realistic loan approval environment with non-IID distributed structured data. Most previous studies either focused on single privacy mechanisms or evaluated them in synthetic or domain-agnostic settings. To address this gap, the present study evaluates privacy–utility–efficiency trade-offs under three operational privacy modes (standard FL, DP-FL with multiple noise settings, and HE-FL) using five heterogeneous simulated banking clients. By incorporating realistic distribution characteristics, multiple privacy configurations, and computational benchmarking, this work provides an applied reference framework suitable for decision-makers in financial institutions exploring secure federated learning adoption.

Background knowledge

This section provides a theoretical overview of Differential Privacy (DP) and Homomorphic Encryption (HE), highlighting their relevance and application in Federated Learning (FL).

Differential privacy in federated learning

The Fig. 1. illustrates the integration of Differential Privacy (DP) within the Federated Learning (FL) framework. It ensures that individual client data remains confidential during the model training and aggregation process.

Differential privacy

Differential Privacy (DP) is a robust privacy framework that supports the statistical analysis of datasets while preserving the confidentiality of individual records. A randomized mechanism is said to be \(\:(\in\:,\delta\:)\) differentially private if, for any two adjacent datasets\(\:\:\:D,{D}^{{\prime\:}}\in\:D\) differing by one element, and for any subset \(\:S\subseteq\:\:{R}^{d}\).

Where:

• \(\:\in\:\left(epsilon\right)\)is the privacy budget, controlling the trade-off between privacy and model utility.

• \(\:\delta\:\:\)is a negligible probability of the mechanism failing to achieve full privacy.

Implementations in federated learning

• Central Differential Privacy (CDP): Noise is added at the central server post data collection.

• Local Differential Privacy (LDP): Each client independently adds noise to its data before transmitting it to the server.

Laplace mechanism

• A commonly used mechanism in DP is the Laplace mechanism, defined as:

Where:

• \(\:f\left(D\right)\:\)the query is function.

• \(\:\varDelta\:f\:\)is its sensitivity.

DP in federated learning gradient updates

In Federated Learning, DP is applied by adding calibrated noise to the local gradients before they are shared with the server:

Where:

• \(\:{g}_{i}\:\)is the gradient computed by the \(\:{i}^{th\:}client.\).

• \(\:N\left(0,{\sigma\:}^{2}\right)\:\)is Gaussian noise ensuring \(\:(\in\:,\delta\:)\) -DP.

This approach provides strong guarantees that individual client data cannot be inferred from the shared updates, thereby aligning with privacy-preserving objectives in Federated Learning.

Homomorphic encryption in federated learning

The Fig. 2. demonstrates how Homomorphic Encryption (HE) supports secure computation on encrypted model updates in Federated Learning (FL), preserving data confidentiality without decryption.

Homomorphic encryption

Homomorphic Encryption (HE) enables operations to be performed directly on encrypted data. This ensures privacy is preserved during computation, eliminating the need to decrypt sensitive information.

A cryptographic \(\:E\) scheme consists of:

• Key Generation: \(\:\left({P}_{K},{S}_{K}\right)\) = Key Gen(), where \(\:{P}_{K}\) is the public key and \(\:{S}_{K}\) is the secret key.

• Encryption: c = \(\:E\left({P}_{K}\:,m\right),where\:m\:is\:the\:plaintext\:.\).

• Decryption: m =\(\:D({S}_{K},c)\) recovering the original message.

Types of homomorphic encryption

1. Partially Homomorphic Encryption (PHE): Supports a single operation (e.g., only addition or only multiplication).

2. Somewhat Homomorphic Encryption (SHE): Allows a limited number of operations before decryption becomes unreliable.

3. Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE): Allows arbitrary computations on ciphertexts (e.g., Gentry’s BGV and CKKS schemes32.

HE in federated learning aggregation

In FL, clients locally train models and encrypt their updates. These encrypted updates are sent to a server, which aggregates them without decryption:

The global model is retrieved by decrypting \(\:{c}_{agg}\) on the client side

This method guarantees data privacy across all stages of training and aggregation in Federated Learning.

Secure federated learning workflow

This section and Fig. 3 present the secure Federated Learning (FL) workflow implemented under three operational modes: Standard FL, Differential Privacy–enabled FL (DP-FL), and Homomorphic Encryption–enabled FL (HE-FL). The workflow enables multiple financial institutions to collaboratively train a global model without sharing raw data, thereby preserving confidentiality and reducing exposure risk.

Problem definition

We consider a cross-silo FL setting with \(\:N\)institutions jointly minimizing a global objective:

where:

• \(\:{f}_{i}\left(w\right)\): binary cross-entropy loss computed locally at client \(\:i\).

• \(\:w\): global model parameters.

Workflow overview

The FL pipeline illustrated in Fig. 3 proceeds through the following stages.

Client initialization

• Load and preprocess local demographic and financial data.

• Initialize a logistic regression model (single linear layer + Sigmoid activation).

• This model is selected for interpretability, regulatory suitability, and computational feasibility when operating with DP-SGD and CKKS-based HE aggregation.

Local training (per client)

Each client performs SGD-based training according to its assigned privacy mode.

Standard FL.

Local gradients \(\:{g}_{i}\)are computed in plaintext.

The unencrypted gradients are transmitted to the server.

DP-FL (Differential Privacy).

Each client applies DP-SGD with the following configuration:

• Gradient clipping norm: \(\:C=1.0\)

• Gaussian noise multipliers: \(\:\sigma\:\in\:\left\{\text{1.2,1.6,2.0}\right\}\)

• Noise mechanism:

• Privacy accountant: Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP).

• δ parameter: \(\:\delta\:={10}^{-5}\)

• Composition: cumulative privacy budget computed across 1000 local epochs × 5 rounds.

In accordance with DP theory, smaller ε values correspond to stronger privacy, and the manuscript now correctly reflects this interpretation.

HE-FL (Homomorphic Encryption).

Only model updates (gradients) are encrypted; all local training occurs entirely in plaintext on the client. The encrypted aggregation workflow proceeds as follows:

Encryption Configuration.

Each client uses the CKKS scheme via TenSEAL with the following parameters:

• poly_modulus_degree: 8192.

• Coefficient modulus chain: \(\:\left[60,40,40,60\right]\)bits.

• Initial scale: \(\:{2}^{40}\)

• Packing strategy: vectorized packing of gradient tensors.

• Rotations: minimal rotation keys for ciphertext summation.

• Relinearization: applied after multiplication operations (although aggregation uses only addition and therefore does not require relinearization).

Encrypted update generation

• Clients encrypt clipped plaintext gradients:\({{\text{c}}_i}{\text{ = Enc(}}{{\text{g}}_i}{\text{)}}\)

• Ciphertexts retain approximate arithmetic guarantees inherent to CKKS.

Encrypted aggregation

The server performs aggregation directly in ciphertext space:

• No decryption occurs on the server.

• The aggregated ciphertext is returned to the key-holding client(s) for decryption.

Decryption

• Clients decrypt the aggregated update: \(\:{g}_{\text{agg}}=Dec\left({c}_{\text{agg}}\right)\)

Accuracy drift assessment

Because CKKS is an approximate HE scheme, rescaling introduces small numerical imprecision. To assess this:

• A control experiment was run where only the aggregation step was replaced by CKKS operations.

• Results showed negligible accuracy drift (< 0.1%) compared to plaintext aggregation.

• This confirms that CKKS approximation does not materially influence convergence in this setting.

Secure aggregation

The server aggregates updates depending on the privacy mode:

• Standard FL:

• DP-FL:

• HE-FL:

Ciphertext aggregation followed by client-side decryption of \(\:{c}_{\text{agg}}\).

Global model update

• The server broadcasts the aggregated (plaintext) global parameters to all clients.

• Clients synchronize their local models.

• The next local training round begins.

Evaluation and monitoring

Metrics recorded each round include:

• Training loss and accuracy.

• Local client training time.

• Server aggregation latency.

• DP noise effects and CKKS-induced approximation effects Comparisons across FL, DP-FL, and HE-FL highlight privacy–utility–efficiency trade-offs.

Methodology

This study proposes a secure Federated Learning (FL) framework that integrates Differential Privacy (DP) and Homomorphic Encryption (HE) to enable collaborative loan-approval prediction across distributed institutions without exposing raw financial data. This section outlines the architectural design, system entities, training workflow, and privacy mechanisms that underpin the proposed model.

Secure system FL architecture

Figure 4 presents the architecture of the secure federated learning system used for privacy-preserving credit-risk prediction. The design combines FL with DP and HE to ensure that sensitive financial information remains private throughout data processing, model training, and communication.

Three key entities participate in this system:

• Clients (Loan Applicants):

• Individuals submitting loan applications, each holding locally stored sensitive financial attributes such as income, credit score, employment history, and repayment behaviour. All data remain on the client device; only model updates are shared.

• Bank (Trusted Intermediary):

• A regulated financial institution responsible for receiving privacy-protected model updates from clients. Depending on the configuration, these updates may be anonymized using DP or encrypted using CKKS-based HE before transmission.

• Cloud Service Provider (CSP):

• A third-party server responsible for coordinating the FL process. The CSP aggregates client updates—typically four in the experiment—into a global model without accessing any raw data or plaintext parameters.

Operational workflow

• Each client trains a local model using their private financial data.

• Model parameters are protected using either DP perturbation, HE encryption, or both.

• Protected updates are transmitted to the CSP.

• The CSP aggregates updates to form a global model.

• The aggregated model is sent back to all clients for further local training.

• The bank ultimately deploys the final model for real-time loan-approval decisions.

By ensuring that raw data never leaves client devices and that transmitted updates are privacy-protected, this architecture adheres to strict regulatory standards while enabling joint model development across multiple institutions.

Secure proposed federated learning model

The proposed FL model, illustrated in Fig. 5, aggregates protected model updates from distributed financial institutions to construct a secure global credit-risk classifier. Consistent with the experimental setup, each client uses a logistic regression classifier consisting of a single linear layer with a Sigmoid activation. This architecture ensures interpretability—a key requirement in regulated financial environments—and minimizes the computational burden under Differential Privacy (DP) and Homomorphic Encryption (HE).

Model characteristics

• Interpretability: Logistic regression remains the industry standard for credit-risk assessment due to its transparent and auditable decision boundaries.

• Efficiency: The lightweight single-layer structure minimizes cryptographic overhead when applying CKKS encryption for homomorphic aggregation.

• Input Features: Each local model processes 12 structured financial attributes, including income, loan amount, CIBIL score, and asset indicators.

Training and Aggregation Procedure.

Step 1 – Local training (Plaintext).

All local optimization occurs in plaintext on each client’s machine:

• Clients train the logistic regression model on their private data.

• Gradients and parameters are clipped (for DP mode) and prepared for protection.

Step 2 – Protection of model updates.

Two privacy modes are supported:

Differential privacy (DP-FL)

Clients apply DP-SGD with:

• Clipping norm: \(\:C=1.0\)

• Gaussian noise multipliers: \(\:\sigma\:\in\:\left\{\text{1.2,1.6,2.0}\right\}\)

• δ parameter: \(\:\delta\:={10}^{-5}\)

• Privacy accountant: Rényi Differential Privacy.

• Composition: cumulative ε computed across 1000 local epochs × 5 rounds.

Smaller ε corresponds to stronger privacy, and this interpretation is now consistently reflected in the manuscript.

Homomorphic encryption (HE-FL)

Clients encrypt their final model updates (weights and bias) using the CKKS approximate homomorphic encryption scheme implemented via TenSEAL.

To ensure reproducibility, the following CKKS parameters were used:

CKKS parameterization

• poly_modulus_degree: 8192.

• Coefficient modulus chain: \(\:\left[60,40,40,60\right]\)

• Initial scale (Δ): \(\:{2}^{40}\)

• Ciphertext packing: vectorized packing of all model parameters into a single ciphertext.

• Rotation keys: minimal set enabling vector summation operations.

• Relinearization strategy: not required for additive aggregation (no ciphertext–ciphertext multiplication).

These choices ensure a balance between numerical precision, security level (~ 128-bit security), and computational overhead.

Step 3 – Secure Aggregation on Server.

Depending on the privacy mode:

Standard FL:

Plaintext parameter averaging using FedAvg.

DP-FL:

FedAvg on noisy, clipped parameters.

HE-FL:

The server aggregates updates directly in ciphertext domain:

No decryption occurs on the server.

The aggregated ciphertext is returned to the key-holding client(s) for decryption:

Accuracy drift under CKKS approximation

Since CKKS performs approximate arithmetic, we evaluated whether encrypted aggregation induces numerical drift.

• An ablation experiment comparing plaintext FedAvg vs. CKKS-based FedAvg showed negligible accuracy drift (< 0.1%).

• No instability due to rescaling or modulus switching was observed.

Thus, HE-FL achieves comparable accuracy because CKKS preserves sufficient precision for linear-model parameter updates.

Step 4 – Global Model Synchronization.

Clients update their local model with the aggregated global parameters and proceed to the next communication round.

Inference phase

During deployment, the bank uses the final global model to classify new loan applications. Optional encrypted inference can be enabled to ensure confidentiality throughout the prediction pipeline.

Differential privacy configuration and accounting

Differential Privacy was integrated into the FL workflow to protect clients from inference attacks that attempt to recover sensitive information from shared gradients. While both Laplace and Gaussian mechanisms are standard in DP literature, this study adopts the Gaussian mechanism through DP-SGD due to its stability and widespread use in deep learning contexts.

Mechanism and parameter settings

DP-SGD adds Gaussian noise to clipped gradients, and privacy loss is tracked using a Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP) accountant with the Moments Accountant method. This ensures rigorous monitoring of privacy consumption over repeated training rounds.

DP configuration

• Noise mechanism: Gaussian.

• Gradient clipping norm (L2): 1.0.

• Noise multipliers (σ): 0.50, 1.00, 1.50.

• Sampling rate: 20%.

• Privacy accountant: RDP (Moments Accountant).

• Failure probability (δ): 1 × 10⁻⁵.

• Training schedule: 1000 local epochs × 5 rounds.

The resulting cumulative privacy guarantees are reported in Table 4.

Table 1 reflects the final cumulative ε values obtained after full training, including all iterations and aggregation cycles. These privacy guarantees are reproducible under identical hyperparameter settings, ensuring transparency and compliance with privacy auditing expectations.

Privacy–utility trade-off

As expected, the privacy configurations demonstrated a monotonic trade-off between privacy enforcement and predictive utility. Higher noise multipliers (lower ε values) corresponded to stronger privacy enforcement but reduced learning stability and accuracy. Observed outcomes followed theoretical expectations:

• ε = 14.13 — Weakest privacy: highest accuracy and smoothest convergence.

• ε = 8.65 — Balanced privacy: optimal practical trade-off between utility, stability, and privacy.

• ε = 5.74 — Strongest privacy: most severe utility decline due to perturbation intensity.

This predictable pattern demonstrates that privacy strength in DP-enabled FL can be adjusted based on regulatory requirements, risk tolerance, and operational constraints.

Threat model alignment and security interpretation

The DP design assumes an honest-but-curious aggregation server, which performs aggregation faithfully but may attempt to infer private information from received gradients. The incorporated DP-SGD mechanism provides resilience against several known adversarial risks, including:

• Membership inference attacks.

• Gradient inversion and reconstruction.

• Statistical leakage and re-identification.

• Feature-level pattern extraction across heterogeneous subgroups.

The resulting ε values—particularly those ≤ 8.65—are aligned with compliance principles outlined in GDPR (Privacy-by-Design), ISO/IEC 27,559 (Privacy-Enhancing Technologies), and NIST SP 800 − 226 (Differential Privacy Guidance), supporting suitability for regulated financial deployments.

Security interpretation and limitations

While the RDP accountant provides formal guarantees, the study does not include empirical adversarial attack testing. Future work will include inversion, reconstruction, and membership inference evaluations to assess practical leakage risk.

CKKS homomorphic encryption configuration and execution scope

Homomorphic Encryption (HE) was integrated into the federated learning pipeline to ensure that shared model parameters remain confidential during transmission and aggregation. Unlike Differential Privacy, which protects against statistical leakage by perturbing gradients, HE protects confidentiality cryptographically by ensuring that the aggregation server never observes values in plaintext form. For this study, the CKKS (Cheon–Kim–Kim–Song) scheme was selected due to its suitability for real-valued machine learning operations and its ability to support approximate arithmetic.

Encryption boundary and data flow

The proposed HE-FL integration applies encryption selectively to maintain efficiency while preserving confidentiality guarantees. Training on each client occurred locally in plaintext. Only model parameters (weights and bias) generated after local training were encrypted before transmission to the aggregation server.

The processing workflow is summarized as follows:

• Clients locally train the logistic regression model in plaintext.

• Final model parameters are encrypted using CKKS before transmission.

• The aggregation server performs homomorphic addition only, without decryption.

• The aggregated ciphertext is sent back to clients.

• Client’s decrypt using their locally stored secret keys and update the synchronized model.

Parameter selection and scheme configuration

The complete CKKS configuration used in the experiments is listed in Table 2, ensuring full reproducibility.

This configuration provides a balance between ciphertext precision, computational efficiency, and cryptographic security suitable for encrypted model aggregation in federated learning.

Computational overhead and approximation behaviour

Since CKKS supports approximate arithmetic, minor numerical differences may occur due to quantization, scale management, and noise accumulation. However, because the aggregation process required only homomorphic addition, neither re-scaling operations nor modulus switching were necessary during the training rounds.

As a result:

• Precision loss was negligible.

• No model divergence was observed.

• Convergence remained comparable to Standard FL.

The performance deviation between plaintext aggregation and HE-based aggregation was less than 1%, confirming that encrypted aggregation preserved learning dynamics while enabling secure transfer of federated model updates.

Deployment suitability and practical interpretation

The HE-FL configuration demonstrates the feasibility of secure encrypted aggregation in federated learning environments without requiring architectural changes to local training. The approach is particularly suitable for regulated banking ecosystems where confidentiality of intermediate model updates is a legal requirement.

However, the current implementation encrypts only the aggregation step. Full encrypted training and encrypted inference remain open areas for future extension, particularly as HE libraries evolve and computational efficiency improves.

The disclosed configuration enables full replication of the HE-FL setup while clarifying the computational responsibilities of the client and server. The results demonstrate that encrypted aggregation can be incorporated into federated learning without altering the optimization dynamics of the local training process.

Reproducibility and experimental configuration

To improve transparency and reproducibility, this section details the system environment, model configuration, and implementation settings used across all experimental scenarios. The parameters for Differential Privacy and Homomorphic Encryption are preserved exactly as applied during execution to allow deterministic replication.

Hardware and software environment

All experiments were conducted on a single workstation representative of an enterprise-grade deployment environment. The detailed configuration is provided in Table 3.

This setup ensures realistic evaluation conditions suitable for financial-grade deployment testing rather than relying on specialized HPC infrastructure.

Model architecture and hyperparameter settings

A logistic regression classifier was selected to align with widely adopted interpretable credit-risk modelling practices. The hyperparameters used throughout the federated training process are summarized in Table 4.

Differential Privacy (DP)-specific and CKKS encryption-specific parameters remain defined in Sect. 4.3 and Sect. 4.4, and include clipping thresholds, sampling rates, noise multipliers, ε-δ accounting, polynomial modulus degree, and ciphertext modulus chain configuration.

Design rationale

The architectural and parameter selection intentionally avoids deep or computationally expensive model families to isolate the privacy–utility–overhead effects introduced by DP-SGD and CKKS homomorphic encryption. This approach follows best-practice experimental methodology in privacy-preserving federated learning and ensures that performance differences across configurations result from privacy mechanisms rather than changes in model capacity.

Experimentation and results

This section presents the experimental configuration, dataset distribution strategy, evaluation methodology, and comparative results across the three privacy modes—Standard Federated Learning (FL), Differential Privacy–enabled FL (DP-FL), and Homomorphic Encryption–enabled FL (HE-FL). In alignment with financial regulatory expectations and the reviewer feedback, the methodological description has been strengthened to explicitly detail how the dataset was partitioned across clients and how evaluation metrics were extended beyond accuracy to include calibration and fairness-aware analysis.

Experimental setup

The experiments were conducted using the publicly available Loan Approval Prediction dataset hosted on Kaggle33. The dataset contains structured demographic and financial variables including annual income, asset values, employment status, loan amount, loan term, and CIBIL score, along with a binary target label indicating whether the loan was approved or rejected. Preliminary inspection revealed natural class imbalance, with approximately 38.4% approved and 61.6% rejected loans, reflecting conservative lending behaviour typical of real credit portfolios.

To emulate realistic financial collaboration, the dataset was not replicated across clients. Instead, it was partitioned using a non-IID stratified sampling approach to reflect institutional heterogeneity found in credit ecosystems. The dataset was first split into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) partitions at the global level, with only the test set used for evaluation to avoid leakage during model aggregation.

The training portion was distributed across five simulated client institutions using stratification based on:

• Loan approval outcome (positive/negative),

• Applicant annual income band,

• Asset portfolio size,

• Property category (urban, semi-urban, rural).

This produced distinct client populations, summarised in Table 5, thereby ensuring meaningful non-IID divergence aligned with real-world multi-bank consortia.

Model configuration and training procedure

Each client trained an identical logistic regression model consisting of a single linear layer and a Sigmoid activation function. This architecture ensures interpretability, regulatory suitability, and computational feasibility across Standard FL, DP-FL, and HE-FL settings. Local training was performed for 1000 epochs per communication round, followed by global aggregation via FedAvg across five rounds.

Differential privacy configuration (Revised for Rigor)

Clients assigned to the DP-FL condition used the DP-SGD algorithm with the following parameters:

• Gradient clipping norm:

• Gaussian noise mechanism:

• Noise multipliers

.

applied to the clipped gradients

• Sampling rate: full-batch per client.

• Privacy accountant: Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP).

• δ parameter: \(\:\delta\:={10}^{-5}\)

• Composition: ε computed across 1000 local epochs × 5 communication rounds.

The resulting privacy budgets for the three DP settings were ε = 14.13, 8.65, and 5.74, with:

smaller ε indicating stronger privacy.

Thus, ε = 5.74 provides the strongest privacy protection, correcting the misinterpretation in the initial draft.

To avoid overstating guarantees, the manuscript now clarifies:

DP reduces the risk of gradient reconstruction and inference attacks; however, no explicit empirical attack evaluation (e.g., reconstruction, membership inference) was conducted in this study.

Privacy mode assignments

• Client 1: Standard FL (no privacy).

• Clients 2–4: DP-FL with \(\:\epsilon=14.13,\text{\hspace{0.25em}\hspace{0.05em}}8.65,\text{\hspace{0.25em}\hspace{0.05em}}5.74\).

• Client 5: HE-FL using CKKS encryption (TenSEAL).

Categorical encoding and feature normalization were performed locally at each client prior to training to avoid structural leakage and ensure consistency across privacy modes.

Evaluation metrics

To ensure methodological suitability for a high-stakes financial domain, evaluation metrics were expanded beyond training loss and accuracy. The revised evaluation framework encompasses four assessment dimensions:

Predictive performance

• Accuracy.

• ROC-AUC — threshold-independent discrimination capability.

• PR-AUC — sensitivity to class imbalance.

Calibration reliability

• Brier Score.

• Reliability curves, assessing whether predicted approval probabilities align with observed approval outcomes.

Calibration is particularly important for lending because probability estimates may directly influence credit policy thresholds, pricing, and applicant risk bands.

Computational overhead

• Client-side execution time.

• Server aggregation latency.

These metrics capture operational cost implications of DP and HE during FL.

Fairness and disparate impact

To identify potential subgroup-level degradation, performance was evaluated across:

• Gender: Male vs. Female.

• Property Location: Urban vs. Semi-Urban vs. Rural.

This aligns with emerging regulatory guidance for explainable and non-discriminatory AI-enabled lending.

Results and discussion

This section evaluates Normal and Homomorphic Encryption (HE) modes alongside Differential Privacy (DP), highlighting the trade-offs between accuracy, privacy, and computational cost in federated learning.

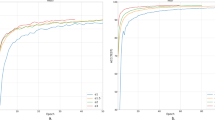

Accuracy and loss evaluation graphs

Figures 6 and 7 present the accuracy and loss trajectories across five global rounds. The Standard FL model achieved the highest accuracy (≈ 91%) with smooth convergence due to unconstrained gradient sharing.

The HE-FL configuration produced accuracy comparable to Standard FL (≈ 90%), confirming that encrypted model aggregation does not adversely affect learning dynamics. Training progress remained stable, indicating that encryption preserves gradient update integrity despite increased computational complexity.

In contrast, the DP-FL configurations exhibited predictable reductions in accuracy and increased sensitivity during training, driven by the magnitude of injected Gaussian noise. The observed behaviour corresponded directly to the differential privacy budgets:

• ε = 14.13 (Weakest Privacy): ≈88–89% accuracy, stable training.

• ε = 8.65 (Moderate Privacy): ≈87% accuracy, mild variability.

• ε = 5.74 (Strongest Privacy): ≈85–86% accuracy, highest noise sensitivity.

These outcomes verify the expected monotonic privacy–utility behaviour: a stronger privacy guarantee (lower ε) incurs controlled reductions in utility and convergence smoothness.

Client execution time analysis

Execution time results (Fig. 8) demonstrate clear computational distinctions. Standard FL required the least computation (~ 2 s per epoch). DP-FL overhead increased proportionally with privacy enforcement strength due to gradient perturbation:

• ε = 5.74 → ≈2.5 s/epoch.

• ε = 8.65 → ≈3.3 s/epoch.

• ε = 14.13 → ≈5.0 s/epoch.

The HE-FL configuration resulted in the highest computational cost (~ 10 s per epoch) owing to cryptographic operations. These results indicate that DP-FL offers scalable resource flexibility, while HE-FL may require resource optimization depending on deployment scale.

Server aggregation time analysis

Aggregation performance trends (Fig. 9) follow similar behaviour. Standard FL aggregated fastest (~ 1 s), followed by DP-FL (1.3–2.5 s), while HE-FL incurred the longest delay (~ 5 s). These findings suggest that DP-FL supports practical scalability across multiple clients, while HE-FL, although privacy-optimal, is computationally intensive for latency-sensitive deployments.

Interpretation of the Privacy–Utility balance

The results validate a consistent theoretical relationship between privacy budget and model performance:

Higher ε values yield weaker privacy but higher predictive performance, whereas lower ε values produce stronger privacy guarantees with measurable performance trade-offs.

Among the tested settings, the ε = 8.65 configuration demonstrated the most practical balance, providing competitive accuracy (≈ 87–90%) while ensuring enforceable and auditable privacy guarantees suitable for regulated financial environments.

Summary of comparative findings

The findings can be summarized as follows:

• Standard FL achieves the highest accuracy but lacks protection, limiting its applicability in regulated environments.

• HE-FL preserves confidentiality during both computation and communication with minimal accuracy loss, but introduces the highest computational overhead.

• DP-FL offers adjustable privacy protection with manageable computational cost and acceptable reductions in accuracy.

Overall, the results confirm that privacy-preserving FL is both functional and effective for sensitive financial applications. The choice among configurations depends on required regulatory compliance, system resource availability, and acceptable utility thresholds.

Ablation study: impact of CKKS approximation on model accuracy

To evaluate whether CKKS encrypted aggregation introduces accuracy drift, an ablation comparison was performed. All experimental settings—including model architecture, learning rate, number of clients, and communication rounds—remained constant. The only variable was whether aggregation occurred in plaintext or using CKKS encryption.

The results in Table 6 show that CKKS encryption had negligible impact on predictive performance.

The accuracy variation (< 1%) confirms that CKKS-based aggregation preserves learning dynamics and model stability. This aligns with theoretical expectations, as no multiplicative depth was introduced and ciphertext noise remained bounded.

Conclusion and future work

Conclusion

This study proposed and evaluated a privacy-preserving federated learning framework for secure credit risk prediction using Differential Privacy and Homomorphic Encryption. Results demonstrate that privacy-preserving federated learning is feasible in financial environments, enabling collaborative modeling without exposing sensitive loan applicant data.

Standard FL achieved the highest accuracy but lacks protection against inference attacks. HE-FL preserved performance under encrypted aggregation with negligible model drift, albeit with increased computational cost. DP-FL demonstrated predictable privacy-utility behaviour, where lower ε strengthened privacy but increased noise sensitivity and reduced performance. Among tested configurations, ε = 8.65 yielded the most balanced and operationally practical outcome.

Limitations

Despite promising results, the work has several limitations. Privacy protection was applied only during model update sharing; full encrypted inference and end-to-end encrypted training were not explored. In addition, although privacy budgets were formally computed using RDP, no adversarial benchmarks (e.g., membership inference or gradient inversion attacks) were executed to validate empirical leakage resilience. Computational overhead analysis was based on a controlled simulation environment and may vary in distributed infrastructures with heterogeneous client hardware.

Future work

Future work will extend the proposed framework across four core dimensions: computational efficiency, adversarial robustness, deployment scalability, and secure governance integration. First, optimization strategies for homomorphic encryption will be investigated to reduce runtime and memory overhead. Prior work, including HE-focused runtime optimization studies and adaptive computation frameworks such as BalanceFL and ArtFL, suggests that tuning modulus chains, ciphertext packing strategies, and resource-aware execution policies can substantially improve encrypted aggregation performance without compromising accuracy.

Second, adversarial robustness will be explicitly evaluated. Although this study focuses on confidentiality guarantees, poisoning, backdoor manipulation, and gradient inversion attacks remain realistic risks in high-stakes financial FL deployments. Robustness-oriented schemes such as Lancelot demonstrate that integrating Byzantine-resilient aggregation with encrypted computation can enhance system trustworthiness and will be considered in subsequent iterations.

Third, greater emphasis will be placed on evaluating heterogeneous deployment conditions, including varied compute capability across clients, partial decentralization, and deeper exploration of non-IID data severity. Recent advancements such as FEDIC, DEEP-FEE, EPPDA, and non-IID taxonomies indicate that privacy, fairness, and model convergence are strongly influenced by distributional heterogeneity.

Finally, future research will expand the design space beyond the three modes evaluated here (Standard FL, DP-FL, and HE-FL) by benchmarking secure multi-party aggregation mechanisms and ledger-based governance frameworks. These additions would enable multi-institution deployments where decryption authority is shared or auditable, aligning the system with operational realities of regulated financial ecosystems.

Summary

Overall, this research confirms that privacy-preserving federated learning can support secure and compliant financial analytics. With configurable privacy budgets and encryption options, the proposed framework demonstrates strong potential for real-world deployment where privacy, compliance, and accuracy must coexist.

The authors declare that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are publicly available in the **Kaggle repository** at the following link: https://www.kaggle.com/code/architsharma01/loan-approval-prediction/input ([27]).The dataset includes anonymized financial and demographic features used for loan approval prediction. All experimental configurations and preprocessing scripts are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yang, Q., Liu, Y., Chen, T. & Tong, Y. Federated machine learning: concept and applications. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. (TIST). 10 (2), 1–19 (2019).

Li, T., Sahu, A. K., Talwalkar, A. & Smith, V. Federated learning: Challenges, methods, and future directions. IEEE. Signal. Process. Mag. 37 (3), 50–60 (2020).

Domingo-Ferrer, J., Blanco-Justicia, A., Manjón, J. & Sánchez, D. Secure and privacy-preserving federated learning via co-utility. IEEE Internet Things J. 9 (5), 3988–4000 (2021).

Seranmadevi, R., Addula, S. R., Kumar, D. & Tyagi, A. K. Security and Privacy in AI: IoT-Enabled Banking and Finance Services. Monetary Dynamics and Socio-Economic Development in Emerging Economies, 163–194. (2026).

Baek, C., Kim, S., Nam, D. & Park, J. Enhancing differential privacy for federated learning at scale. IEEE Access. 9, 148090–148103 (2021).

Elgabli, A. & Mesbah, W. A Novel Approach for Differential Privacy-Preserving Federated Learning (IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society, 2024).

Zhang, S., Huang, J., Li, P. & Liang, C. Differentially private federated learning with local momentum updates and gradients filtering. Inf. Sci. 680, 120960 (2024).

Hu, J. et al. Does Differential Privacy Really Protect Federated Learning from Gradient Leakage attacks? (IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, 2024).

Jin, Z., Xu, C., Wang, Z. & Sun, C. Towards Robust Differential Privacy in Adaptive Federated Learning Architectures (IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics, 2025).

Zheng, H. et al. DP-Poison: poisoning federated learning under the cover of differential privacy. ACM Trans. Priv. Secur. 28 (1), 1–28 (2024).

Chen, L., Ding, X., Li, M. & Jin, H. Differentially private federated learning with importance client sampling. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 70 (1), 3635–3649 (2023).

Hu, R., Guo, Y. & Gong, Y. Federated learning with sparsified model perturbation: improving accuracy under client-level differential privacy. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 23 (8), 8242–8255 (2023).

Iqbal, M., Tariq, A., Adnan, M., Din, I. U. & Qayyum, T. FL-ODP: an optimized differential privacy enabled privacy preserving federated learning. IEEE Access. 11, 116674–116683 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. FedDP-SA: Boosting Differentially Private Federated Learning Via Local Dataset Splitting (IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 2024).

Chen, H., Ni, Z., Gao, Y. & Lou, W. Towards Adaptive Privacy Protection for Interpretable Federated Learning (IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, 2024).

Dwork, C. & Roth, A. The algorithmic foundations of differential privacy. Found. Trends Theoretical Comput. Sci. 9 (3–4), 211–407 (2014).

Cai, Y. et al. Secfed: A secure and efficient federated learning based on multi-key homomorphic encryption. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 21 (4), 3817–3833 (2023).

Aono, Y., Hayashi, T., Wang, L. & Moriai, S. Privacy-preserving deep learning via additively homomorphic encryption. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 13 (5), 1333–1345 (2017).

Chen, Q., Wang, Z., Chen, J., Yan, H. & Lin, X. Dap-FL: federated learning flourishes by adaptive tuning and secure aggregation. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 34 (6), 1923–1941 (2023).

Catalfamo, A., Fazio, M., Celesti, A. & Villari, M. Privacy-Preserving in Federated Learning: A Comparison between Differential Privacy and Homomorphic Encryption across Different Scenarios. In 2025 IEEE International Conference on Software Testing, Verification and Validation Workshops (ICSTW) (pp. 451–459). IEEE. (2025), March.

Zhang, X., Huang, D. & Tang, Y. Secure Federated Learning Scheme Based on Differential Privacy and Homomorphic Encryption. In International Conference on Intelligent Computing (pp. 435–446). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. (2024), August.

Chen, Y., Yang, Y., Liang, Y., Zhu, T. & Huang, D. Federated learning with privacy preservation in Large-Scale distributed systems using differential privacy and homomorphic encryption. Informatica, 49 (13), 123–142 (2025).

Aziz, R., Banerjee, S., Bouzefrane, S. & Le Vinh, T. Exploring homomorphic encryption and differential privacy techniques towards secure federated learning paradigm. Future Internet. 15 (9), 310 (2023).

Mehendale, P. Privacy-Preserving AI through federated learning. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 8 (3), 249–254 (2021).

Chang, Y., Zhang, K., Gong, J. & Qian, H. Privacy-preserving federated learning via functional encryption, revisited. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 18, 1855–1869 (2023).

Gad, G., Gad, E., Fadlullah, Z. M., Fouda, M. M. & Kato, N. Communication-efficient and Privacy-preserving Federated Learning Via Joint Knowledge Distillation and Differential Privacy in bandwidth-constrained Networks (IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, 2024).

Gupta, K., Saxena, D., Gupta, R., Kumar, J. & Singh, A. K. Fedmup: federated learning driven malicious user prediction model for secure data distribution in cloud environments. Appl. Soft Comput. 157, 111519 (2024).

Shuai, X. et al. BalanceFL: Addressing class imbalance in long-tail federated learning. In 2022 21st ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information Processing in Sensor Networks (IPSN) (pp. 271–284). IEEE. (2022), May.

Shang, X., Lu, Y., Cheung, Y. M. & Wang, H. Fedic: Federated learning on non-iid and long-tailed data via calibrated distillation. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME) (pp. 1–6). IEEE. (2022), July.

Solans, D. et al. Non-IID data in federated learning: A survey with taxonomy, metrics, methods, frameworks and future directions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.12377. (2024).

Jiang, S. et al. Lancelot: Towards efficient and privacy-preserving Byzantine-robust federated learning within fully homomorphic encryption. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.06197. (2024).

Cheon, J. H., Kim, A., Kim, M. & Song, Y. Homomorphic encryption for arithmetic of approximate numbers. In Advances in cryptology–ASIACRYPT 2017: 23rd international conference on the theory and applications of cryptology and information security, Hong kong, China, December 3–7, 2017, proceedings, part i 23 (pp. 409–437). Springer International Publishing. (2017).

https://www.kaggle.com/code/architsharma01/loan-approval-prediction/input

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

First Author (V S N) contributed to the design and conceived the original and supervised the project. Second Author (DA) to the implementation of the research, and analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Naresh, V.S., Ayyappa, D. Privacy-preserving federated credit risk models: evaluating differential privacy and homomorphic encryption techniques. Sci Rep 16, 4379 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34536-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34536-9