Abstract

The ability to simulate and forecast extreme precipitation events has become increasingly important due to their significant impacts on society. From 29 July to 31 July 2023, Henan province was hit by extreme rainfall, which led to widespread flooding and significant economic losses (this event is referred to as “23·7”). The research assessed the model’s sensitivity to topography data (USGS and SRTM), initial and boundary conditions - IBC (FNL and ERA), and model initial times. Results indicated that while all experiments could capture the general rainfall pattern, their performance varied significantly. The model showed greater sensitivity to IBC than to topography. FNL IBC experiments initialized on 29 July better replicated the spatial distribution of precipitation, whereas ERA IBC experiments more accurately simulated its temporal evolution and heavy rain extent. While the use of SRTM topography demonstrates improvement in almost all FNL IBC experiments, it exhibits a decline in simulation performance for the ERA IBC experiments initialized on 28 July. The choice of initial time also significantly influenced the results. These results will be helpful in understanding how the combination of different topography data and IBC affects rainfall prediction in the WRF model and improves the forecast skills for heavy rainfall over the study region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Influenced by climate change, the frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation events will likely increase in the future1. These events often trigger floods and landslides which have substantial impacts on socioeconomic development and agricultural production. A stark reminder of this growing threat was the unprecedented rainstorm that struck central and northern Henan Province on 20 July 2021, which resulted in 398 fatalities and extensive damage to infrastructure2. Such extreme precipitation events caused enormous impacts on social and economic development, and human production and life. Therefore, precipitation estimation and simulation in a particular area are essential. Owing to the significant increase in extreme rainfall, accurate rainfall prediction is an urgent research issue in Henan province. From 29 July to 31 July 2023, the remnant circulation of Typhoon Doksuri moved northward, triggering an extreme rainstorm in Henan Province, China. This event produced significant precipitation along the eastern foothills of the Taihang Mountains, causing severe economic losses. Therefore, an in-depth study of it is of great significance for improving the forecasting capabilities for similar extreme weather events3.

Nowadays, numerical weather models have been widely used in precipitation simulation and forecasting4. Among various models, the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model as a regional climate model that dynamically downscales the General Circulation Model, is widely used in precipitation simulation and forecasting5,6,7. It performs well in simulating and forecasting variables such as temperature, humidity, and wind8,9,10. However, the task of simulating and forecasting the spatial and temporal variations of extreme precipitation remains a challenge for numerical models, due to the complex formation processes and rapid variation in a short period, especially for regions with a complex topography11,12,13,14. Therefore, the WRF model precipitation simulation performance in simulating precipitation events under diverse and varying conditions needs to be evaluated.

Many studies showed uncertainties in WRF models, such as initial and boundary conditions15,16,17,18. It is well known that model simulations are sensitive to the initial conditions of land surface state and other variables that play a role in triggering the convective system. Trier et al.19 proved that simulated atmospheric stability and convection initiation are affected by details in the initial soil moisture distribution. Wang and Yang20 found that the simulation results using different reanalysis data to force a WRF model produced remarkable differences in precipitation. Tewari et al.21 found that initial and boundary conditions played an important role in simulating the location of maximum precipitation.

Complex topography is one of the important geophysical features that control the local weather conditions and is another influential factor in precipitation simulation22. Topography is particularly important in cloud formation and the distribution of variables with altitude via atmospheric dynamics such as local and planetary boundary layer processes. Various studies have shown that improving the representation of topography by using updated high-resolution topography is important to improve the performance of the WRF model outputs23,24,25. For example, Teixeira et al.23 modeled precipitation using the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) as topography forcing. They showed differences of up to 500 m between United States Geological Survey (USGS) topography data and SRTM in the Portuguese Madeira Island. They also found changes in precipitation patterns associated with the change in topographic forcing, with increases in the mountains and decreases in the valleys.

Each of these studies investigates the sensitivity of the WRF model configured differently. Previous studies have demonstrated that the selection of different initial and boundary conditions can directly influence the success of WRF predictability and have attracted the most attention. However, until now, there is an apparent absence of a study encompassing a large ensemble that includes information about the impacts of the initial and boundary data source and the topography on the extreme precipitation simulations. The main objectives are understanding the sensitivity of model simulations to two initial and boundary conditions, and quantifying the dependence of the simulations on topography data.

Methods and data

Study area

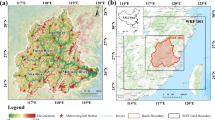

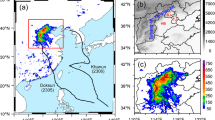

An extreme precipitation event occurred in Henan and its surroundings from 29 July to 31 July 2023. The remnant circulation center of Typhoon Doksuri is located in Henan Province. The subtropical high extended westward and northward, merging with a continental high-pressure ridge over western North China to form an east-west oriented “high-pressure dam.” This barrier impeded the northward-moving typhoon depression, causing it to slow down significantly upon entering Henan (Fig. 1). Influenced by the inverted trough system of the typhoon vortex, the precipitation has been particularly intense. Meanwhile, the southwestern moisture transport channel from the South China Sea and the southeastern moisture transport channel from the eastern seas of China converge in East China. Northern Henan is situated in the mid-to-lower reaches of the moisture transport flux center in East China, which is conducive to extreme heavy precipitation26. Additionally, influenced by the Taihang Mountains in northwestern Henan, these factors collectively triggered the extreme precipitation in northern Henan. On the 29th, the daily precipitation of the seven national stations of Xunxian, Linzhou, Huaxian, Xinxiang, Gongyi, Songshan, and Dengfeng (Fig. 2a) exceeded the historical extreme value in late July since the establishment of the station. Among them, the daily precipitation of Xunxian was nearly twice that of its historical extreme in late July.

Henan province is located in the North China Plain, the topography is flat in the center and east of Henan, and rugged in the west because of the mountains and basins. The elevation of the study area is between 50 m and 2000 m.

Data

The hourly observed precipitation data from 2752 stations were used to evaluate the model performance (Fig. 2b). To run the WRF model, two different boundary and initial condition datasets were used, which are the Fifth generation European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts reanalysis data (ERA) and Final Operational Global Analysis data (FNL). FNL is provided by the National Center for Environmental Prediction (NCEP), which has 1° x 1° spatial resolution at a frequency of six hours27. ERA is provided by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, which has 0.25° x 0.25° spatial resolution at a frequency of six hours28. Two topography data were used in this research. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) (Fig. 2a) is the corresponding topography obtained in the preprocessing module of WRF (defined as old)29. In the same way, Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM) is as the new data (Fig. 2b)30. The resolution of USGS and SRTM is 30 s (about 1 km) and 90 m. The difference between these two data is larger in the western part of Henan, and smaller in the east part of Henan (Fig. 2c). Figure 2d and e show the topography of FNL and ERA. The height increases roughly from east to west. In eastern Henan, the altitude is < 200 m; in central Henan, the height of the terrain ranges from 200 to 500 m; and in western Henan, the height is above 500 m. The WRF model has a higher resolution than the two reanalysis datasets, which represent more accurate and clearer coastlines and terrain details.

Model experiments

WRF nested three domains with horizontal resolutions of 27 km, 9 km, and 3 km (Fig. 3). The physical parameterizations were selected as follows: Thompson microphysical scheme; the Kain-Fristch cumulus convective scheme; Dudhia shortwave radiation, Rapid Radiative Transfer Model (RRTM) longwave radiation, Yonsei University boundary layer scheme, and the Noah Land surface model. And in domain 3, the cumulus convective scheme was turned off.

We designed experiments to evaluate models simulated starting from a different time. Through this extreme precipitation started from 0000 UTC on July 29, from 0000 UTC on July 28, and from 0000 UTC on July 27 (the spin-up is 6 h). And on every initial time, we designed four experiments. In this research, twelve experiments were set up (Table 1).

Statistical indexes

Several statistical indexes are used in this research, including the Pearson correlation coefficient (CC), root-mean-square error (RMSE), Bias, and mean absolute error (AE). CC quantifies the linear correlation between model simulations and observations, the higher CC means the better performance. RMSE is a commonly used metric to measure the difference between model simulations and observations, with the smaller RMSE means better performance. Bias is the difference between model simulations and observations, the best value is 0. AE reflects the actual magnitude of the deviation between model simulations and observations. In addition, four precipitation indexes: Probability of detection (HIT), False alarm ratio (FAR), Threat Score (TS), and ACCURACY are applied. The aim of these indexes is to further evaluate the model performance.

Where Mod is the model results, and Obs is the observed values. NA is that the site shows rain and the model also shows rain; NB is the site shows no rain, and the model shows rain; NC is the site shows rain, and the model shows no rain; ND is the site shows no rain, and the model also shows no rain. In this paper, according to Chinese precipitation classification standards, different levels of precipitation are evaluated. When the rainfall at the station is greater than or equal to the threshold value, it is included in the threshold score (the threshold value of light rain, moderate rain, heavy rain, storm, and extraordinary storm within 24 h, which are 0.1 mm, 10 mm, 25 mm, 50 mm, and 100 mm, respectively).

Results

The Spatial distribution of precipitation

Figure 4 shows the spatial distribution of 72-hour (from 0000 UTC 29 to 2359 UTC 31 July 2023) and 24-hour accumulated (from 0000 UTC 29 to 2359 UTC 29 July 2023) precipitation. As can be seen in Fig. 4b, the center of this precipitation event is located in the northern part of Henan. The precipitation in Xunxian and its surrounding areas is categorized as an extreme precipitation event. Figure 5 reveals that all simulation cases reproduce the spatial distributions of the precipitation to a certain extent, i.e., large values in the northern part of Henan. However, when it comes to the precise location and range of the heavy rain area, various model experiments yield differing results.

From Fig. 5a and g, it can be seen that the spatial pattern of precipitation is highly sensitive to the IBC. The amount and area of precipitation are larger in experiments using ERA IBC compared to those using FNL IBC of 28 July and 29 July initializations. In the ERA IBC experiments, precipitation in northern Henan Province increased as the initialization time was advanced. In contrast, for the FNL IBC experiments, the 0000 UTC 28 July initialization performed the worst among all initializations. Significant discrepancies exist between model experiments and observations in terms of the precipitation pattern in southern Henan. The ERA IBC experiments overestimate the precipitation, while the FNL IBC experiments underestimate the precipitation for most experiments. Among all experiments, the ERA_0729_new experiment can capture the characteristics of the observed precipitation area and provide a more precise simulation in the northern part of Henan. Furthermore, the location of the simulated heavy rainfall center is more precise when using the new topography data. The performance of simulating 72-hour accumulated precipitation is similar to the performance of simulating 24-hour accumulated precipitation.

The spatial distribution of 24-hour accumulated precipitation of the ERA_0727_old (a), ERA_0727_new (b), ERA_0728_old (c), ERA_0728_new (d), ERA_0729_old (e), ERA_0729_new (f), FNL_0727_old (g), FNL_0727_new (h), FNL_0728_old (i), FNL_0728_new (j), FNL_0729_old (k), and FNL_0729_new (l) model simulation experiments.

In order to better evaluate the spatial distribution of the simulated precipitation, the 24-hour (0000 UTC 29 July – 2359 UTC 29 July) and the 72-hour (0000 UTC 29 July – 2359 UTC 31 July) accumulated precipitation from all model experiments with observations are compared. Station observations are interpolated to the 3 km grid, which is the same as the model grid, to calculate the CC, RMSE, Bias, and AE. These three indices have been calculated and shown in Table 2. For the 24-hour accumulated precipitation, the FNL_0729_new experiment performs best in the CC, RMSE, and AE, with values of 0.78, 28.91 mm, and 19.96 mm, respectively. The ERA_0728_old experiment shows the best performance in Bias, with a value of −6.34%. Almost all experiments underestimate the precipitation for the entire Henan region and the northern part of Henan. For the 72-hour accumulated precipitation, the FNL_0729_new experiment has the highest CC, and the ERA_0728_new experiment has the lowest Bias. These results indicate that the FNL_0729_new experiment provides the most accurate simulation of precipitation spatial distribution over both short and long durations, with higher CC. For most experiments, the CCs are higher, and the RMSEs are lower when using the SRTM topography data for the 24-hour accumulated precipitation in most experiments. Overall, for 29 July initializations using FNL IBC have higher CC and lower RMSE than using ERA IBC.

Table 3 shows the maximum value of accumulated precipitation and its location of observation and the experiments. For the 24-hour accumulated precipitation, the ERA_0729_new experiment shows the smallest bias (−15 mm) in maximum intensity, while the ERA_0728_new and FNL_0727_new experiments most accurately simulate the precipitation center, with location biases of 0.27° in latitude and 0.04° in longitude. The distance of the extreme precipitation center between models and observation is about 30–200 km. The ERA_0728_old and FNL_0729_old experiments overestimate the precipitation maxima, while the other experiments underestimate the precipitation. Regarding the 72-hour precipitation, the ERA_0728_old experiment produces the closest match to the observed maximum amount, with a bias of 12.24 mm. The ERA_0727_old experiment most accurately reproduces the location of the precipitation center, with latitude and longitude biases of 0.13° and 0.05°, respectively. The distance of the extreme precipitation center between models and observation is about 15–150 km. The ERA_0728_old, ERA_0729_old, FNL_0729_old, and FNL_0729_new experiments overestimate the precipitation maxima, other experiments underestimate the precipitation maxima. Overall, these results suggest that all experiments tend to underestimate the precipitation maxima. Additionally, the location of the maximum precipitation tends to be relatively close to the observations in some experiments.

To quantify the intensity of rainfall and compare it with observational data, a probability density function (PDF) is plotted for all experiments (Fig. 6). The figure reveals that the PDF of the whole Henan region and its northern part differ significantly. For the 24-hour accumulated precipitation over the entire Henan region, the PDF of the FNL_0728_new is closer to the observational PDF up to 20 mm/day, and after 80 mm/day, the PDF of the ERA_0729_new are more closely with the observation. When using the new topography data, the PDF of the experiments matches the observed PDF more closely beyond 80 mm/day than when using the USGS data. In the northern part of Henan, the PDF of the FNL_0729_old experiment is closer to the PDF of observation between 130 mm/day and 180 mm/day, and the PDF of the ERA_0729_new experiment is closer to the PDF of observation after 180 mm/day. For the 72-hour accumulated precipitation over Henan province, the PDF of the ERA_0728_old experiment is closer to the PDF of observation between 40 mm/day to 60 mm/day, and the PDF of the ERA_0729_new experiment is closer to the PDF of observation after 80 mm/day. In the northern part of Henan, the PDF of the FNL_0729_new experiment is closer to the PDF of observation after 240 mm/day. Overall, the PDFs of the different experiments show significant variations. Both the IBC and topography data have a substantial impact on the PDF for different rainfall levels.

Figure 7 shows the 24-hour and 72-hour accumulated precipitation at the seven stations (Fig. 2a). From the figure, it can be seen that ERA IBC experiments show better performance than FNL IBC experiments at most stations. Topography data influence the model performance largely. When the new topography data is used, the performances of the FNL IBC experiments increase at most stations, and the performances of the ERA IBC experiments decrease at most stations for 0000 UTC 29 July initialization. For the 24-hour accumulated precipitation, the FNL_0729_old experiment shows the best performance at Xunxian station. While for the 72-hour accumulated precipitation, the FNL_0729_new experiment shows the best performance. The IBC plays an important role in simulating at the station, with the ERA IBC experiments outperforming those using the FNL IBC in most cases. The topography data plays a crucial role in simulating precipitation at the stations. For the experiments employing the ERA IBC, the model’s performance diminishes when the updated topography data is incorporated for most stations for the 0000 UTC 29 initializations. Conversely, in the FNL IBC experiments, the new topography data significantly enhances the model’s performance. Besides IBC and topography, the initial time also affects model performance. As the initialization time approaches, performance improves at some stations but deteriorates at others.

To further assess the precipitation forecasting capabilities of all experiments, four precipitation indices—HIT, FAR, TS, and ACCURACY—have been chosen for comparing the models. Considering the extreme precipitation event that occurred on July 29, these indices from 0000 UTC on July 29 to 2359 UTC on July 29 are analyzed, and the results are presented in Fig. 8. The figure indicates that the models perform better for light rain and extraordinary storms. In terms of HIT, the ERA_0728_new is highest for light rain, the ERA_0729_old is highest for moderate rain, the FNL_0727_old is highest for heavy rain, and the ERA_0728_old is highest for extraordinary storm. The HITs are higher when the new topography data is used for extraordinary storms in almost all cases. In terms of FAR, the experiments are higher for the moderate rain and lower for the extraordinary storm. The FARs are lower when the new topography data is used in most cases. Additionally, ERA IBC experiments achieve higher TS scores compared to FNL IBC experiments for extraordinary storms, and ERA IBC experiments achieve lower TS scores compared to the FNL IBC experiments for light rain in most cases. In terms of ACCURACY, FNL IBC experiments outperform ERA IBC experiments for light rain and moderate rain, while ERA IBC experiments are superior for other precipitation levels. When the topography data is changed, the ACCURACYs of ERA IBC experiments are higher for the 0000 UTC 27 July initialization, and the ACCURACYs of FNL IBC experiments are higher for the 0000 UTC 29 July initialization. Among them, the ERA_0729_new experiment exhibits optimal performance for the extraordinary storm, characterized by relative higher HIT, TS, and ACCURACY, as well as a lower FAR. The influence of topography data on precipitation indices is relatively minor.

The scatter plots of simulated and observed 24-hour accumulated precipitation are shown in Fig. 9. From the figure, it can be seen that all experiments predominantly exhibit an underestimation of precipitation, and as the initial time increases, the degree of underestimation decreases. Furthermore, ERA IBC experiments demonstrate superior performance compared to FNL IBC experiments for most cases. Additionally, the model’s performance is influenced by the topography, which has the potential to enhance its accuracy in certain regions.

The scatter plots of observed versus simulated 24‑hour accumulated precipitation for the 12 experiments: ERA_0727_old (a), ERA_0727_new (b), ERA_0728_old (c), ERA_0728_new (d), ERA_0729_old (e), ERA_0729_new (f), FNL_0727_old (g), FNL_0727_new (h), FNL_0728_old (i), FNL_0728_new (j), FNL_0729_old (k), and FNL_0729_new (l).

The Temporal evolution of precipitation

Figure 10 displays the precipitation time series for several stations. At the Xunxian station, all experiments fail to simulate the precipitation peak occurring before 0600 on July 29 and overestimate the precipitation after 0000 on July 30. Among these, the ERA_0729_new experiment stands out as the best in simulating precipitation at this station for the second peak on July 29. For the Linzhou, Xinxiang, Gongyi, Songshan, and Dengfeng stations, the model experiments successfully identify several precipitation peaks on July 29. Nevertheless, most experiments overestimate the precipitation after 0000 on July 30, with FNL IBC experiments exhibiting the most significant overestimation. Overall, ERA IBC experiments perform better, and incorporating the new topography data enhances the model’s performance.

The CCs of 3-hour accumulated precipitation between observed precipitation and the experiments from 29 July to 31 July 2023 are shown in Fig. 11. From this figure, it can be seen that the CC of 0000 UTC 29 July initialization is higher than other initializations, both for ERA IBC and FNL IBC. It is evident from this figure that the CCs of ERA IBC experiments are higher compared to those of FNL IBC experiments in most areas. Upon altering the topography, an improvement in performance is observed in most areas. Additionally, the influence of IBC is more pronounced than that of topography, with a difference exceeding 0.1 in CCs.

The CCs between observed and simulated 3‑hour accumulated precipitation for the 12 experiments: ERA_0727_old (a), ERA_0727_new (b), ERA_0728_old (c), ERA_0728_new (d), ERA_0729_old (e), ERA_0729_new (f), FNL_0727_old (g), FNL_0727_new (h), FNL_0728_old (i), FNL_0728_new (j), FNL_0729_old (k), and FNL_0729_new (l).

Figure 12 shows the meridional precipitation propagation over Henan during this event. Observations indicate that precipitation bands are dispersed between 35°N and 36°N from 0800 UTC on July 29th to 1000 UTC on the same day, spreading from south to north. Subsequently, at 1300 UTC on July 29th and 0100 UTC on July 30th, two significant rain concentrations emerged between 36°N and 36.5°N. ERA_0729_old and ERA_0729_new experiments are able to capture the precipitation bands within the 35°N to 36°N latitude range, albeit slightly later than observed. However, FNL IBC experiments underestimate the intensity of the precipitation belt. Notably, the rain belt in the ERA_0729_new experiment aligns more closely with the observations compared to the rain belt in the ERA_0729_old experiment. Both the ERA IBC and FNL IBC experiments of the 0000 UTC 29 July initialization are able to identify the precipitation center at 0100 UTC on July 30th. However, there is a slight timing discrepancy: the ERA_0729_new experiment captures the precipitation center slightly later, while the FNL_0729_old experiment detects it earlier.

Figure 13 illustrates the spatial distribution of the average temperature on July 29. Temperature plays a critical role in rainfall processes, as its variation directly influences vertical atmospheric motion and humidity distribution, thereby further affecting the formation and spatial patterns of precipitation. As shown in the figure, the temperature fields exhibit considerable differences between the ERA IBC and FNL IBC experiments. In the northern part of Henan, the temperature in ERA_0729_old is higher than that in FNL_0729_old, accompanied by greater precipitation in the ERA_0729_old experiment. It is also evident that changes in topographic data lead to modifications in temperature. These temperature variations, in turn, affect sensible and latent heat fluxes, ultimately influencing the spatial distribution of precipitation.

Figure 14 presents the spatial distribution of average relative humidity and surface wind on July 29. Humidity plays a critical role in the rainfall process by indicating the amount of moisture in the air, and high humidity enhances atmospheric moisture content, facilitating cloud development and precipitation formation. Meanwhile, the surface wind field significantly influences rainfall through its direction and intensity, which govern moisture advection and spatial distribution, thereby shaping the patterns and occurrence of precipitation. As shown in the figure, noticeable differences in humidity are observed between the ERA IBC and FNL IBC experiments, which likely contribute to variations in precipitation distribution. Additionally, topography exerts a clear influence on humidity patterns. Higher humidity levels generally correspond to increased precipitation. In terms of wind fields, the remnant circulation center of Typhoon Doksuri is situated over Henan. Changes in topographic data further modify the spatial structure of precipitation. Specifically, an increase in small- to medium-scale topographic features may enhance mechanical turbulence in mountainous regions, thereby suppressing local convection. This process favors the formation of more low-level clouds and reduces convective rainfall.

Conclusion and discussion

It is generally accepted that numerical models exhibit diverse behaviors depending on their configurations and the specific target regions they are applied. In this research, the extreme precipitation event in Henan from 29 to 31 July 2023 was simulated using the WRF model. The sensitivity of WRF simulation to two different reanalysis datasets (FNL and ERA), three different model initial times, and two topography data, a total of twelve WRF simulations were conducted. All experiments were able to capture the accumulated precipitation to an extent, but there were differences in the location, intensity, and timing of the precipitation.

Due to the distinct characteristics inherent in the ERA and FNL analyses, the precipitation simulations produced by the WRF model vary significantly when utilizing different IBCs. Hwang et al.31 discovered that the WRF model, when employing ECMWF analysis data as IBC, delivered more accurate precipitation simulations compared to those utilizing NCEP analysis data, especially for high-intensity precipitation. Similarly, Huang and Gao32 conducted WRF simulations across China spanning the years 2000–2014, utilizing both FNL and ERA reanalysis data. Their findings revealed that, in terms of precipitation and extreme precipitation simulations, the WRF model forced by ERA outperformed the WRF model forced by FNL. Our results align with these previous findings, indicating that the WRF model’s performance in simulating various levels of precipitation and the temporal distribution of precipitation is superior when using ERA data compared to observations, as opposed to simulations using FNL data. However, it is noteworthy that the FNL initial and boundary conditions excel in simulating the spatial distribution of precipitation in some cases. The enhanced performance of model simulations utilizing ERA data is consistent with previous research outcomes31. This superiority may be partially attributed to ERA’s higher resolution and more sophisticated data assimilation technique compared to FNL. Specifically, the data assimilation method employed in the FNL utilizes three-dimensional variational analysis, whereas the ERA reanalysis employs four-dimensional variational analysis, contributing to its enhanced capabilities.

The topography data plays an important role in simulating precipitation, the model performance is changed when using the high-resolution topography data. Li et al.33 found that the distribution characteristics of simulated precipitation are closer to the observations when the topography data was changed, and the refined terrain (SRTM) is beneficial to the model to effectively reproduce the distribution and evolution characteristics of local precipitation in the area with complex terrains. Conversely, Teixeira et al.23 reported a slight decrease in model skill when using SRTM data compared to the control simulation, although this reduction was minimal. Our research findings differ from previous studies in that when the SRTM topography data was used to replace the model’s default topography data. The performance of WRF simulated the spatial distribution of precipitation was improved when model default topography data were replaced by the high-resolution topography data for FNL IBC experiments. However, for simulations using ERA IBC initialized at 0000 UTC 28 July, the performance in simulating the spatial distribution of precipitation worsened when the topography data was updated. The biases in the simulated precipitation decreased for both ERA and FNL IBC when the new topography data were incorporated in most cases. The influence of topography data varies considerably across different stations and precipitation levels. These results highlight the complexities involved in incorporating high-resolution topography data into the model and suggest that the impact of such data may vary depending on the initial and boundary conditions used.

Jang and Hong34 studied the lead time effect for heavy precipitation in Korea. They suggested that the effects of lead time should be considered for forecasting heavy rainfall. Jee and Kim35 mentioned that the lead time experiments can provide some insights to end-users on the best numerical model performance given a specific forecasting time. In the present work, we found that the precipitation amount is better simulated when the models are initialized at 0000 UTC on 29 July than at other times.

It is to be noted that the current study examined the sensitivity of different initial and boundary conditions and topography data for a specific heavy precipitation event. Therefore, further research needs to be conducted to obtain a general conclusion for different classes of precipitation events. However, the case study approach used herein could enable a better understanding of heavy precipitating events and their prediction.

Data availability

The datasets utilized in this study were obtained from three sources: the Fifth generation European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts reanalysis data (available at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets), the Final Operational Global Analysis data (accessible via https://rda.ucar.edu/datasets/d083002/), and meteorological observations from the China Meteorological Administration (available at https://data.cma.cn/).

References

Gründemann, G. J., van de Giesen, N., Brunner, L. & van der Ent, R. Rarest rainfall events will see the greatest relative increase in magnitude under future climate change. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 235 (2022).

Su, A. F., Lyu, X. N. & Cui, L. M. The basic observational analysis of 7.20 extreme rainstorm in Zhengzhou. Torrential Rain Disaster. 40, 445–454 (2021).

Chen, T. et al. Fine characteristics of the July 2023 extreme rainfall in North China and associated synoptic weather patterns. Acta Meteorologica Sinica. 82, 600–614 (2024).

Hiraga, Y. et al. Model-based Estimation of long-duration design precipitation for basins with large storage volumes of reservoirs and snowpacks. J. Flood Risk Manage. 17, e12992 (2024).

Chang, H. I. et al. The role of land surface processes on the mesoscale simulation of the July 26, 2005 heavy rain event over Mumbai, India. Glob Planet. Change. 67, 87–103 (2009).

Routray, A., Mohanty, U., Niyogi, D., Rizvi, S. & Osuri, K. K. Simulation of heavy rainfall events over Indian monsoon region using WRF-3DVAR data assimilation system. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 106, 107–125 (2010).

Mohanty, U., Routray, A., Osuri, K. K. & Prasad, S. K. A study on simulation of heavy rainfall events over Indian region with ARW-3DVAR modeling system. Pure Appl. Geophys. 169, 381–399 (2012).

Mölders, N. Suitability of the weather research and forecasting (WRF) model to predict the June 2005 fire weather for interior Alaska. Wea Forecast. 23, 953–973 (2008).

Yu, E., Sun, J., Chen, H. & Xiang, W. Evaluation of a high-resolution historical simulation over china: climatology and extremes. Clim. Dyn. 45, 2013–2031 (2015).

Duan, H. et al. Evaluation of the forecast accuracy of near-Surface temperature and wind in Northwest China based on the WRF model. J. Meteorol. Res. 32, 469–490 (2018).

Stephens, G. L. et al. The dreary state of precipitation in global models. J. Clim. 23, 2459–2478 (2010).

Gheusi, F. & Stein, J. Phenomenology of summer alpine rain events. Q. J. Roy Meteor. Soc. 139, 510–525 (2013).

Rotach, M. W., Ambrosetti, P., Ament, F., Appenzeller, C. & Zappa, M. The MAP D-PHASE: Real-time demonstration of weather forecast quality in the complex terrain of the alps. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 95, 1093–1107 (2014).

Bauer, P., Thorpe, A. & Brunet, G. The quiet revolution of numerical weather prediction. Nat 525, 47–55 (2015).

Golding, B. W. Quantitative precipitation forecasting in the UK. J. Hydrol. 239, 286–305 (2000).

Bray, M., Han, D., Xuan, Y., Bates, P. & Williams, M. Rainfall uncertainty for extreme events in NWP downscaling model. Hydrol. Process. 25, 1397–1406 (2011).

Jha, S. K., Shrestha, D. L., Stadnyk, T. A. & Coulibaly, P. Evaluation of ensemble precipitation forecasts generated through post-processing in a Canadian catchment. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 22, 1957 (2018).

Hally, A., Richard, E. & Ducrocq, V. An ensemble study of hymex IOP6 and IOP7a: sensitivity to physical and initial and boundary condition uncertainties. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 1071–1084 (2014).

Trier, S. B., Chen, F. & Manning, K. W. A study of convection initiation in a mesoscale model using high-resolution land surface initial conditions. Mon Wea Rev. 132, 2954–2976 (2004).

Wang, B. & Yang, H. Hydrological issues in lateral boundary conditions for regional climate modeling: simulation of East Asian summer monsoon in 1998. Clim. Dyn. 31, 477–490 (2008).

Tewari, M. et al. Implementation and verification of Unified Noah Land Surface Model in WRF Model. Preprint at https://ams.confex.com/ams/84Annual/techprogram/paper_69061.htm(2004).

Amjad, M., Yilmaz, M. T., Yucel, I. & Yilmaz, K. K. Performance evaluation of satellite- and model-based precipitation products over varying climate and complex topography. J. Hydrol. 584, 124707 (2020).

Teixeira, J. C., Carvalho, A. C., Carvalho, M. J., Luna, T. & Rocha, A. Sensitivity of the WRF model to the lower boundary in an extreme precipitation event-Madeira Island case study. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 2009–2025 (2014).

Jiménez-Esteve, B., Udina, M., Soler, M. R., Pepin, N. & Miró, J. R. Land use and topography influence in a complex terrain area: A high-resolution mesoscale modelling study over the Eastern Pyrenees using the WRF model. Atmos. Res. 202, 49–62 (2018).

Saavedra, M., Junquas, C., Espinoza, J. & Silva, Y. Impacts of topography and land use changes on the air surface temperature and precipitation over the central Peruvian Andes. Atmos. Res. 234, 104711 (2020).

Yao, X. P. et al. Characteristics of the July 2023 extreme rainfall in North China and its water vapor supply. Acta Meteorologica Sinica. 82, 585–599 (2024).

Kalnay, E. et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 77, 437–471 (1996).

Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P. & Hirahara, S. Thépaut J. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. Roy Meteoro Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Skamarock, W. C. et al. A description of the Advanced Research WRF model version 4. Preprint at https://opensky.ucar.edu/system/files/2024-08/technotes_576.pdf(2019).

Rodríguez, E., Morris, C. S. & Belz, J. E. A global assessment of the SRTM performance. Photogramm Eng. Rem. S. 72, 249–260 (2006).

Hwang, J., Cha, D. H., Yoon, D., Goo, T. Y. & Jung, S. P. Effects of initial and boundary conditions on heavy rainfall simulation over the yellow sea and the Korean peninsula: comparison of ECMWF and NCEP analysis data effects and verification with dropsonde observation. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 41, 1787–1803 (2024).

Huang, D. & Gao, S. Impact of different reanalysis data on WRF dynamical downscaling over China. Atmos. Res. 200, 25–35 (2018).

Li, H., Xi, L. & Wang, X. M. A high-resolution numerical simulation of the 7.19 extraordinary heavy rainfall in Henan Province under topographic effect. Front. Earth Sci. 10, 1079369 (2023).

Jang, J. & Hong, S. Y. Quantitative forecast experiment of a heavy rainfall event over Korea in a global model: horizontal resolution versus lead time issues. Meteorol. Amos Phys. 124, 113–127 (2014).

Jee, J. B. & Kim, S. Sensitivity study on high-resolution WRF precipitation forecast for a heavy rainfall event. Atmos 8, 96 (2017).

Funding

Funding: the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 42330610) and the National Key R&D program of China (2023YFC3209301).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Liu Songnan: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Visualization; Writing – original draft. Su Aifang: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Writing – review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, S., Su, A. The sensitivity of WRF extreme precipitation simulations over the Henan Province to different topography and reanalysis data. Sci Rep 16, 4267 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34545-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34545-8