Abstract

Decision-making under risk lies at the core of strategic action in human activities. Nevertheless, the neural mechanisms underlying decision-making in trial-and-error-based learning in the absence of explicit risk ratios have not been thoroughly understood. This study investigates the neural correlates of long-term success during repeated risky decision-making. We combined a motion detection task with a higher-level risk task in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) paradigm. Twenty-five healthy adults participated in an fMRI task that required stopping a ball covertly moving at a constant speed at a certain spot. Participants initially selected a task difficulty level progressively related to the magnitude of the monetary reward and then attempted the task of chosen difficulty. Positive versus negative feedback (a monetary gain versus no gain) contrast comprised clusters in the striatum, executive control regions, and the Default mode network (DMN). The activity in brain regions associated with metacognitive functions (DMN nodes) and not in those involved in reward evaluation and risk-taking (striatum) was positively related to the exploration index, which reflects the effectiveness of risk-taking. This study provides insights into the functional roles of the DMN (especially, its anterior node) in high-level decision-making in risky environments, highlighting its importance in metacognitive control during reward-related learning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The empirical problem of experimental measurement of risk attitudes is one of the current challenges for economic, cognitive, and social disciplines. Despite enduring controversies, there is a consensus about a set of predominantly incentive-based measurement techniques commonly used in economic experiments (see1 for a brief review). Traditionally, researchers have tacitly assumed that these measures are reliable indicators of risk attitudes in a variety of domains. These include, inter alia, experimental games, survey questions, and real-world scenarios such as insurance purchases, risky driving behavior, or financial market decisions. In practice, however, the expected parallelism often turns out to be an exception rather than the rule2. The study of decision-making under risk has traditionally focused on scenarios involving explicit information about the probabilities and magnitudes associated with a gamble3,4. Lottery-based designs offer clear advantages, such as high experimental control and well-defined benchmarks derived from microeconomic models5. However, it is uncertain whether the perception of probabilities in such controlled settings translates to decisions made based on personal experience and individual capabilities. Recent meta-analyses confirm the challenges in transferring findings across different domains of decision-making2,6. Notably, research has shown that while risk-taking tendencies in driving a car have identifiable neuroanatomical correlates7, similar correlations are not observed for risk-taking tendencies assessed through self-report questionnaires.

Neural underpinnings of risky decision-making are typically studied through paradigms that represent either“one-shot” decisions or dynamic interactions with the environment. One-shot decisions1, such as lottery-based tasks, monetary incentive delay tasks, self-reported surveys, Balloon Analogue Risk Task, or Bomb Risk Elicitation Task — involve clear, explicit risks and well-defined choices between safe and risky options. However, this determinism often limits the generalizability of findings, as the cognitive processes guiding the choice between two numerical options do not smoothly translate to other scenarios, such as inflating a balloon in the Balloon Analogue Risk Task2. On the other hand, dynamic tasks like the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT)8 and multi-armed bandit problems9 force participants to engage with options and learn of the reward contingencies. However, these tasks have their limitations; since each attempt yields some form of reward, the element of risk diminishes, and the focus shifts to quickly identifying advantageous options rather than making choices between genuinely safe and risky alternatives.

We combine the advantages of these two approaches in a single decision task where the risk associated with options emerges directly from the participant’s performance. In this task, participants are dealing with a ball rolling at constant speed over a circumference on a computer screen. Most of the route takes place in a virtual tunnel split into 9 segments of diminishing length, labeled from 0 to 8 (see the section “Study overview” for further details). Participants have to first choose a segment, and then roll a ball and stop it within the chosen segment of the tunnel to collect a reward, before moving to the next trial. This task parallels real-world decision-making scenarios which combine experience and luck, such as driving, sports, gambling, or investments. At the performance level, we use a well-established motion error prediction task10. At the higher, cognitive level, we introduce a task involving risky options, similar to a bandit problem or the IGT8. These tasks are interlinked: each new round of feedback from the motion error prediction task serves as a source of subjective probability for participants in the high-level risk-based task.

Since our tasks are repeated, maximization of gains through the entire experiment requires proper selection of the segment, given one’s ability to find the option yielding the highest expected reward. From a neural perspective, two competing possibilities exist regarding the mechanisms underpinning long-term success. The first posits that a consistent level of risk aversion, tied to explicit information about probabilities and value processing, is crucial for task performance. This would primarily engage neural structures such as striatum (Str)11,12,13,14, amygdala15, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC)3. Alternatively, the second hypothesis suggests that reinforcement and the processing of feedback are more critical. According to this latter perspective, the feedback phase is particularly significant, as it is presumed to be where decisions about the higher-level task are most effectively shaped16. On a surface level, the mentioned functions may recruit cortical centers involved in control and performance monitoring, such as the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC)17,18, as well as regions associated with reward delivery in risk-related tasks19,20,21. However, one may assume more complex dynamics that involve using feedback to update beliefs on one’s performance and, therefore, riskiness of attempting an action of a certain difficulty. That would probably involve the Default mode network (DMN) governing self-referential processes22.

The aim of our study was to explore neural correlates of effective decision-making in an environment involving risks depending on one’s competence. We model the behavioral task of our decision makers by a simple maximal expected payoff rule that stipulates the selection of the sector with the highest expected reward given one’s own past performance. Based on this model, we construct an empirical measure of behavioral strategies of every decision maker as the ratio of factual outcomes to the value of the maximal empirical expected payoff (EI, see Eq. 3). Combining this approach with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), we gain new insights into the brain mechanisms that facilitate effective decision-making in dynamic and realistic risk environments.

Results

Behavioral results

Choice Patterns and Outcomes. a A histogram indicating a total quantity of successful (Success) and unsuccessful (Miss) attempts on each segment collapsed across the entire sample. A ratio of successful and unsuccessful attempts may give an impression of objective difficulty of each option. b A histogram of a percentage of rounds when a given segment was established as an optimal option (Mean Max Sector) and when a given segment was actually chosen (Mean Choice). Notably, segments 1-3 were underestimated and segments 4-5 were overestimated by participants suggesting a tendency for a riskier choices, compared to the optimal segment. c The distribution of the exploration index. Values slightly below 1 reflect efficient exploratory behavior, whereas substantially lower values indicate excessive exploration and higher risk-taking that reduce performance. Values above 1—rare in practice—reflect overly conservative, exploitation-dominated strategies.

On the descriptive level, two key observations emerge. Firstly, an asymmetry in Positive (success in stopping the ball within the targeted segment) and Negative (failure to do so) outcomes on the choice scale can be observed (Fig. 1, panel a). The initial segments 0 and 1 were relatively seldom chosen, suggesting that subjects either do not tend to start from the lower options or extrapolate their beliefs about their competence on higher difficulty levels to lower ones. Additionally, there is a noticeable frequency of choosing the segment 8 despite of the low success rate, which indicates the presence of systematic risk-embracing behavior.

To add, participants consistently chose a segment higher than suggested by maximum payoff expectation \(C^*\) from the Eq. 1 (Wilcoxon’s W=78172, p=0.000093; Fig. 1, panel b). This shift to the right of the most advantageous sectors may be explained by either risk-seeking behavior or exploratory strategies.

This point is further clarified by the Exploration index (EI, Eq. 3) distribution (Fig. 1c, panel c). Some participants successfully deviated from the \(C^*\) option to gain new information and ultimately increase their earnings. However, a significant portion, with a noticeable cluster around an exploration index value of less than 0.5 (see the section “Data analysis”), appeared to deviate in favor of riskier options. At the behavioral level, it is difficult to determine whether this pattern reflects a deliberate risk preference that disregards more guaranteed options or rather an inefficient integration of feedback. However, in the following sections, we address this question from the neural perspective.

Imaging results

First, a contrast was examined between the pre-choice periods followed by 1) repeating the previous segment choice and 2) choosing another segment (see the section “fMRI data processing” for description of the contrasts). A number of brain regions were activated to a greater degree during the period leading to a segment choice change, namely, the bilateral superior and inferior parietal lobules, left paracentral lobule, left middle occipital gyrus, left superior and middle frontal gyri, and left precuneus (see Table 1 and Fig. 2). No brain region was more active in the pre-choice period related to maintaining the previous segment choice.

Second, for the Late versus Early period of the ball movement, four major clusters were activated. The activation map comprised primarily regions within bilateral paracentral lobule, supplementary motor cortex, insula, anterior and middle cingulate, occipital cortex, thalamus, and caudate nucleus. At the Early stage, greater activation was revealed in the bilateral putamen and right lingual gyrus, see Fig. 2 and Table 1.

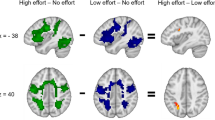

Last, for the Positive vs Negative feedback contrast, key brain regions activated were bilateral striatum, anterior cingulate cortex, medial orbitofrontal cortex, medial superior frontal gyrus, right temporo-occipital cortex, left angular gyrus and inferior parietal cortex, and number of left frontal cortical areas, see Fig. 3 and Table 2. Noteworthy, inclusion of covariates of participants’ sex and z-transformed age resulted in no meaningful changes to the activation maps for any of the contrasts, demonstrating these responses to be sex- and age-independent, see Supplementary Data S1-S6 for details. No significant activation clusters were revealed in the reverse Negative vs Positive feedback contrast.

fMRI activity contrast maps of: Pre-choice period leading to a choice of another vs same segment (A); Late vs Early ball movement period (B). Panels are separated by a dotted line. Another> Same and Late> Early clusters are presented in warm colors (positive t values), Early > Late clusters are presented in cold colors (negative t values). The activation pattern emerged is a spatial processing pattern (A) and combination of a motor circuit and a reward anticipation circuit (B). x and z refer to MNI coordinate of a corresponding slice. SFG superior frontal gyrus, SPL superior parietal lobule, FFG fusiform gyrus, MCC midcingulate cortex, ACC anterior cingulate, Tha thalamus, Cer cerebellum, Ins insula, Caud caudate nucleus, Put putamen, FrOper frontal operculum, PreC precentral gyrus, SMA supplemetary motor area.

The Positive vs Negative feedback contrast activation map.The pattern comprised the striatum and several nodes of the Default mode network. x and z refer to MNI coordinate of a corresponding slice. IFG inferior frontal gyrus, AnG angular gyrus, ACC anterior cingulate, OFC orbitofrontal cortex, Str striatum.

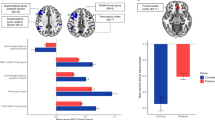

Furthermore, multiple regression revealed a positive relationship between the z-transformed Positive vs Negative feedback contrast value and z-transformed EI value. More precisely, clusters were located in the 1) pregenual and supragenual anterior cingulate and medial orbitofrontal cortex, 2) left middle temporal and supramarginal gyri, 3) left superior and middle frontal gyri, see Fig. 4 and Table 3. For this analysis, the addition of covariates of participants’ sex and z-transformed age yet exerted some statistical map changes, did not affect the general pattern, evidencing consistency of these results across sexes and different ages within adulthood, see Supplementary Data S7-S8 for details. Individual z-transformed filtered values averaged within cluster, significantly correlated with z-transformed EI value, Pearson’s r=0.808, r=0.811, r=0.742 (all p<0.001), for midline anterior, temporo-parietal, and lateral frontal clusters, respectively. Notably, the anterior cingulate / medial orbitofrontal clusters from the t-test and regression results partly overlay, see Supplementary Data S9–S10 for details.

While applied to the two remaining contrasts, the same multiple regression procedure produced no additional significant clusters related to the EI score.

The results of the regression of Positive vs Negative feedback contrast by z-transformed Exploration index.Bottom panels depict correlation between the z-transformed cluster-averaged filtered scores and z-transformed Exploration index. Anterior midline and left lateral Default mode network nodes exhibit a significant correlation with the Exploration index value. Note: the correlation values and scatter plots are provided for illustrative purposes, and should not be interpreted as inferential statistics about the population this sample was drawn from. z refers to MNI coordinate of a corresponding slice. r Pearson’s correlation coefficient, TPJ temporo-parietal junction, SFG superior frontal gyrus, MFG medial frontal gyrus, pACC pregenual anterior cingulate / medial orbitofrontal cortex.

Discussion

In the present study, we aimed to investigate a risky situation, assuming that the riskiness of different options is linked to the individual’s performance experience, similar to how decision-making is performed in closed-loop feedback contexts while driving, doing sports, playing pocket billiards, etc. To investigate the information flow from a low-level operation to a high-level decision-making, we established a composite task. At the performance level, we employed the motion error prediction task10, while at the higher, cognitive level, we introduced a task involving risky options, akin to a bandit problem or the IGT8. These tasks are interconnected so that the feedback from the motion error prediction task serves as a source of subjective probability for participants in the high-level risk-based task. Sequential processing of behavioral data allowed for computation of individual optimal segment choices at each round, deviations from the optimal segment, and an index of reward amount-related consequences of these deviations, i.e., the exploration index.

The approach we present, encapsulated in the EI, has the potential to serve as a robust measure of risk. This index is easy to interpret, and it demonstrates a clear correspondence with neural responses, further validating its utility in assessing risk-related behaviors. However, despite the procedure’s clarity, a comprehensive psychometric study would be needed to validate this task as a standardized tool for eliciting individual risk preferences (e.g., through measures of internal consistency, test–retest reliability, and comparisons with self-report and behavioral risk measures).

In terms of behavior, in a dynamic setting, choosing a riskier option than the one yielding the maximum expected return can be interpreted as a risk-seeking behavior. This observation slightly contradicts classical economic assumptions that agents are generally risk-averse and highlights the importance of the environment and decision-making conditions. If we consider risk as the degree of exploration, then avoiding risk may prevent individuals from achieving higher expected returns. Hence, effective performers typically show an Exploration Index around 0.9-1. Lower scores indicate too much exploration with little gain, while higher scores reflect that participants are more successful than their previous trajectory would demonstrate, which means they explore not enough (risk-averse).

Regarding the fMRI results, the first contrast involved the time periods followed by the choice of the same segment as a previously chosen one and the choice of a different segment. Comparing these conditions, we aimed to highlight brain regions involved in making a decision related to the choice of a segment for the next round based on feedback received. We suggested that the delay between the feedback presentation and the initiation of the subsequent action, whether it involves adjusting the first sector or pressing the trial-run button, is used to make this decision. This delay could be loosely connected to the exploration–exploitation balance. However, as shown by recent intracranial EEG evidence16, decision-related processes typically occur almost immediately after feedback presentation. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the time period immediately preceding the confirmation of the next sector choice is primarily associated with preparatory motor and spatial adjustment processes rather than with decision-making per se.

In our study, the time period preceding the change of the target sector is marked with greater activation of the superior parietal lobule (SPL) along with the left superior frontal gyrus, specifically the left frontal eye field23. SPL is a region known to be involved in spatial processing and imagery24. Current data suggest posterior SPL to be primarily involved in spatial processing, while anterior SPL in the visuomotor control25. This function involves, aside from the SPL, the frontal eye fields that demonstrate strong functional connectivity with the SPL26. Hence, the activation pattern may reflect anticipatory processing associated with adjustments in the spatial configuration of the next trial. Thus, the most plausible explanation is related to technical operations aiding in task performance, not to assessing risk levels or one’s own competence.

The contrast between the late and the early stages of the ball movement revealed numerous activation loci. Several areas clearly indicate movement preparation and execution, namely the precentral and postcentral gyri, as well as the supplementary motor area. These results may be explained by the participant’s planning and finally performing a motor action (button push) at a precise moment he or she considers matching the segment of interest.

Other brain regions involved in the contrast comprise caudate, thalamus, cerebellum, inferior frontal cortex, midcingulate, anterior insula, and occipital cortex. This large set of functionally diverse areas, nevertheless, roughly matches the reward anticipation circuit described in numerous studies, e.g.19,27,28. Indeed, our experimental task may also be simplistically viewed as a reward paradigm that, similarly to the monetary incentive delay task, features a reward reception feedback period and reward anticipation period. Interestingly, the presence of the clear reward anticipation pattern at a late stage of the ball run may evidence participants expecting to win in a substantial portion of trials. To summarize, we interpret the distributed activation pattern in the current contrast as a combination of motor action preparation and execution, and anticipation of the monetary reward feedback.

A characteristic detail of this activation pattern in our study is that the caudate nucleus is activated at a late stage of the ball run, while the putamen is deactivated. While some data suggest its involvement in gain anticipation27,28, in the contrast we examined, putamen activity is greater at the early stage than at the late stage. This finding might be related to the functional role of the putamen within the reward learning or motor system. Current data suggest that the putamen is not heavily involved in reward prediction error coding. Instead, it establishes stimulus-action-reward relationships29 and is more closely connected with the motor system30.

In our paradigm, participants had no a priori information on certain segment choice and response timing that provides the reward, making putamen activation immediately before the button push excessive. This information is updated during the feedback only. Thus, putamen activation during the reward anticipation might be limited to tasks where the rewarded action and the reward feedback do not coincide, or some relevant information must be kept during the anticipation phase. An alternative explanation might be the putamen’s role in principal motor program preparation at the early stage, followed by caudate activation for more temporally precise action.

The feedback stage is probably the most important one for our study because making a choice in the following round is putatively drawn in 300 ms after the feedback reception16. The contrast between the Positive and Negative feedback prompting reception and non-reception of monetary reward, respectively, comprised a number of activated brain regions. As expected, the bilateral striatum was active. The striatum typically exhibits a greater response during the monetary reward reception compared to a non-reception or monetary loss19,28,31,32,33. This response is motivated by the striatum’s role as a part of a dopaminergic system31 in reward learning covering feedback processing34, reward prediction error processing29,31, and options’ relative utility valuation29,31,35,36.

The striatum is involved in reward learning regardless of context31 and the reward type32,37. Thus, we may speculate that positive feedback-related striatum activity in our study integrates monetary rewards together with the subjective rewarding experience of performing well. Thus, we consider monetary gains and success experiences as linked to one another and make no attempt to split them in the current discussion.

Several more brain areas activated in the current contrast are closely related to executive functions. Namely, dorsal (supragenual) anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and left superior frontal gyrus. dACC, along with the dorsal prefrontal cortex, is crucial for“cold” functions for action planning and goal-directed behavior38. In a task involving incomplete information, dACC signaling is related to more accurate behavioral performance in the subsequent trials39. More importantly, dACC participates in the estimation of the cost-benefit ratio of allocating cognitive control to a certain task40. Thus, involvement of the dACC and superior frontal gyrus may indicate“cold” cognitive processing of the feedback.

Aside from the striatum and executive cortical regions, several activation clusters were revealed that could probably be attributed to the DMN. More precisely, an anterior midline node covering portions of the pregenual anterior cingulate (pgACC) and medial orbitofrontal cortex (MOFC), and a lateral node located predominantly in the left angular gyrus. Unlike the dorsal and subgenual parts of ACC41, pgACC is not clearly associated with outcome valuation. Moreover, pgACC activation in our study covers predominantly areas p24ab and p32 known to be involved in the interoception and negative emotions processing42. Being closely connected with the nucleus accumbens, MOFC appears to have a major role in reward value processing43,44,45. Additionally, the MOFC is involved in decision-making of whether to perform a risky choice aiming for an additional reward or not46. According to results from the UK Biobank dataset47, the MOFC connectivity with the ACC is greater in risk-prone people. Therefore, the MOFC / pgACC cluster may be involved both in a reward valuation and in planning a subsequent risky action. The angular gyrus responds to the task difficulty48 and may participate in estimating the difficulty of performing at a current segment, aiding the comparison between options on their complexity.

Though region-by-region interpretation of the neural activation contrast sounds plausible, our study aimed to understand the impact of the DMN as a cohesive system in decision-making in a risky environment. DMN may indeed be activated in response to a reward reception19,22. Reward also increases the DMN-Str connectivity, with this effect correlated with the Big5 openness and agreeableness49. Intra-DMN connectivity and DMN connectivity with the hippocampus and amygdala increase during experiencing a surprise50 that probably may be generalized into a reward prediction error. DMN external connectivity is also correlated with risk seeking51.

However, processing of rewards and risk is not the primary DMN purpose. For instance, a recent review of the DMN cognitive functions barely mentions reward-related learning52. Moreover, the topographic DMN pattern for reward-related tasks is the most distinct one, compared to patterns of other DMN functions22. Like in our study demonstrating strong cingulate/prefrontal activation and no posterior DMN node involvement, a corpus of research in the reward function documents medial prefrontal activation with attenuated, if any, posterior cingulate and precuneus response22.

Main DMN function is considered to be self-reflection or, more broadly, internal-focused processing22,53. Given this DMN node’s (especially, the anterior one) multifunctionality, it might combine reward-related and self-related processing in our task. That may include future planning and some functions described above such as updating beliefs in one’s competence and, therefore, subjective probabilities to hit the spot on a certain difficulty level. This perspective assumes that DMN is possibly involved in the task by granting a set of metacognitive functions aimed at self-assessing performance and riskiness of certain options.

Thus, three major brain systems are significantly activated at the moment of a positive feedback reception, namely the reward system per se, the executive system, and a metacognitive system (DMN). The principal question our study aims to answer is how the activity of these systems is related to participants’ ability to effectively make risky decisions. To mitigate individual differences in task performance and only account for proficient decision-making, we estimated the EI that reflects the effectiveness of taking exploratory risks. Using this variable as a regressor, we obtained a reward-related spatial brain activation pattern, which is positively linked to the amount of winnings extracted from the exploratory choices.

The pattern comprised portions of the pgACC / MOFC, middle temporal and supramarginal gyri, and left superior and middle frontal gyri. The pgACC / MOFC cluster demonstrated a substantial intersection with the corresponding cluster in the reward vs non-reward contrast, and the left frontal cluster also featured a small intersection. It worth noting that the regression revealed no significant activation clusters in the basal ganglia. Therefore, the cortical metacognitive system (DMN) and, to a lesser degree, the executive brain system play a more important role in balancing exploration and exploitation, compared to the subcortical reward system.

The preceding data on the striatum are ambiguous in spite of the predictions we could make, related to exploration-exploitation balance and its effectiveness. Striatum activity is higher for immediate reward than for a delayed one31,54 that would contribute to a preference for exploitative strategies. However, striatum facilitates risky decisions27,55 and its activity is positively related to the amount of the reward31 that would increase exploration at the most difficult options. This conflicting nature of the striatum’s putative influence on the exploration-exploitation balance may be a reason we observe no evidence for such influence in our study. Noteworthy, due to recent evidence, the striatum belongs to neither the exploratory nor the exploitative brain activation pattern, and dopaminergic drugs exert no direct effects on the exploration-exploitation balance56.

Concerning the DMN role in exploration, DMN may produce exploitative choices56, may be related to long-term consequences and, consequently, to exploratory choices57, or may be unrelated to the exploration-exploitation balance9. Some research suggests that DMN activity is representative of ambiguity rather than risk58. The most consistent brain regions governing exploration-exploitation balance are the rostrolateral and dorsolateral prefrontal cortices59,60,61, not present in our results, and the VMPFC/OFC9,16,56,60,62 that may partly intersect with the DMN anterior cluster in our study.

Our study has not directly tested the DMN relationships with the exploration-exploitation balance per se. Instead, we demonstrated the relationships between the DMN and exploration effectiveness. Therefore, the DMN activity arising after the positive feedback and putatively reflecting the metacognitive functions (reassessing one’s own competence and updating beliefs on success chances in a task of a given difficulty) is crucial for a reasonable and efficient engagement in the exploratory risks. We are unaware of the prior data evidencing this role of the activity of the DMN as a cohesive network.

The main takeaway for neuroeconomic modeling is that as decision-making tasks become increasingly metacognitive, the role of domain-specific regions appears to diminish, giving way to processes related to learning and information updating. Our task was designed to reproduce tasks common to real-life behavior, such as driving a car, rather than abstract lottery-like choices. In our dynamic risk context, the probability of gaining nothing is negligible; hence, the risk component becomes secondary to the ability to aggregate information over time. Thus, the observed statistical association between DMN activity and EI can be taken as a preliminary support for the behavior in such tasks being driven by metacognition and learning to a greater degree than by pure risk attitudes.

Nevertheless, our study has some limitations that should be taken into account:

-

1.

We drew our conclusions based on the data of a sample dominated by young females. Risk-taking as well as its neural correlates are known to depend on the participants’ sex and age61,63,64, thus, we are unaware of how our results would generalize to a sample with different demographic characteristics. However, t-test and multiple regression results in our study did not prominently change after the addition of sex and age as covariates of no interest.

-

2.

Discussing the fMRI results, we used back inference, which does not guarantee valid conclusions. In this article, we do not claim to provide a comprehensive account of the neurocognitive processes accompanying risk-taking in competence-dependent situations. Instead, we aimed to formulate plausible hypotheses on the relative involvement of reward-related, cold cognitive, and metacognitive processes and their corresponding brain substrates in this kind of task. This field undoubtedly warrants further thorough investigations.

Methods

Subjects

The sample involved 25 healthy participants, 20 females and 5 males, ranging from 19 to 44 years (m\(\pm\) \(\sigma\) = 25.9±7.3). All subjects participated in a single functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanning day. Participants were free from standard MRI contraindications, had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and exhibited no large structural brain abnormalities that were evidenced by a T1 MRI scan.

The study protocol was approved by the local Institutional Review Board of the International Tomography Center, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Novosibirsk, Russia, approval number 091. All study procedures conformed to the WMA’s Declaration of Helsinki, 2013 revision. All participants provided written informed consent prior to entering the study and received monetary compensation.

Study overview

Stimuli presentation and data collection were implemented in JavaScript, built on the oTree behavioral research platform65. Participants received no guaranteed compensation, though they could earn a sum of money dependent on their performance (a local currency equivalent of 25 EUR, on average). Prior to the study onset, participants received full instructions and completed a short training session conducted outside the scanner. During this training session, all participants sat in front of a computer and performed nine non-incentivized trials, identical in structure and interface to those performed inside the scanner, using the same response buttons as during the fMRI task.

An overview of the paradigm is depicted in Fig. 5. Participants were instructed that during each run a small ball depicted on a screen moves clockwise with a constant velocity. The majority of its track was hidden under the coloured segments of a tube. Subjects’ aim was, first, to choose one of nine segments, and second, to stop the ball with a button push while it was right under the chosen tube segment.

Each consecutive segment was smaller than the previous one, that made it more difficult to stop the ball under the latter segments, compared to the earlier ones. However, the game score received for the correct execution also progressed with a segment, i.e., a correct ball stop under the segment 0 led to a 0 score gain, under the segment 1 led to a 1 score gain, ..., and under the segment 8 led to an 8 score gain. Scores were proportionally transformed to real money after the scanning completion at a linear scale. The principal idea of the paradigm was to allow participants a free choice either to use safer options with a lower payoff or more risky options with a higher payoff and to correct this choice dynamically based on the received gains.

A full run sequence therefore comprised choosing a target segment, running the ball, stopping it (if a participant wished, he or she could skip the whole first round and try to stop the ball on the second or on the third round), and attending the feedback, i.e., either subject won or lost and what was the real ball position to the moment it had been stopped. All commands were entered by pressing MR-compatible buttons. A full round of the ball had taken approximately 10.5 s; feedback screen duration was approximately 3.3 s; time to make a decision was not limited.

Participants took part in two or three scanning sessions of 302 s each. For consistency, we analyzed the first two fMRI sessions of each participant only. However, the full data from two or three sessions was included in the behavioral analysis.

Data analysis

Behavioral data analysis

The proposed paradigm is different from a number of renowned dynamical risk tasks in three ways, each impacting the selection of an indicator. Firstly, unlike in the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT) and trading simulators, outcomes are binary, which simplifies calculations and the subject’s perception of the outcome. Secondly, the risk choice options are intuitively ordered for participants, with nine segments clearly corresponding to ordered probabilities of success. Finally, the chance to succeed in playing a certain sector is implicitly evaluated by participants themselves, which requires no formal calculations on probabilities.

Overall, these changes render the decision-making environment more intuitive and ecologically valid, transforming the task into a multi-armed bandit problem with correlated arms. However, this complicates the analysis, as there is no known general Bayesian analytical solution for dependent arms66.

To summarize, the measurements can be presented as two data series: 1) of binary outcomes (0 or 1) and 2) of choice levels (0 to 8). Two approaches can be implemented in this settings: one involves using structural specifications to assess parameters of interest such as exploration/exploitation ratio coefficient67 and risk aversion coefficient68, while the other involves using descriptive indicators such as the frequency of using the most beneficial option (see69 for the details).

We opted for descriptive measures over structural assessment due to the absence of a universal optimal solution. Rather than simply counting how often a participant deviates from the most beneficial option, we estimated the efficiency of their choices by comparing the actual cumulative payoff to the payoff they would have obtained if they had consistently selected the empirically optimal option. Conceptually, this approach parallels efficiency-based measures used in tasks such as the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT), where performance is typically quantified as the proportion of advantageous choices or the net gain relative to the maximum attainable reward. In our case, the measure is normalized to reflect relative efficiency — how close the participant’s cumulative outcome is to the optimal benchmark given their individual experience. The indicator is computed in three steps: first, we identify the most advantageous segment at each time point; second, we calculate the expected payoff assuming the participant always selected this optimal segment; and finally, we compute the ratio between the participant’s actual payoff and this optimal benchmark. Since the most“profitable” segment was unknown, we first identified the segment with maximal expected payoff at the time stamp k:

Where \(C_k\) belongs to the set \(m \in \{0,...,8\}\) and represents the segment selected at time k; \(I^m_n\) denotes the indicator function, signifying that a segment m was successful in a round n; T(m, k) is a numerical value reflecting the total number of cases assuming a segment number m was chosen at a time k. In the context of the exploitation-exploration tradeoff paradigm, this could be considered as the“Exploitation” segment at a moment k. When we calculated \(C^*_k\) within our dataset, we applied a special correction by including only the levels where the user had at least three observations. This was done to avoid situations where a single attempt would disproportionately affect the overall dynamics of the calculation.

Then, we estimated the expected payoff as if the participant would choose only the \(C^*_k\) option with a corresponding empirical success rate:

After that, we computed a ratio reflecting a relationship between the participant’s actual gain and the one they would obtain using the most efficient“Exploitation” option only:

Thus, this can be regarded as the Exploration index (EI), which measures deviations from the options with the highest expected payoff (see Supplementary Data S11 for an example of EI computation). An index value slightly below 1 (e.g., 0.9–1.0) reflects effective exploratory behavior, where participants occasionally deviate from the most profitable option to test alternatives, yet maintain overall efficiency. Substantially lower values suggest excessive exploration or risk-taking that reduces overall performance, whereas values above 1—although rarely observed, as cumulative payoffs tend to equilibrate over repeated trials—indicate overly conservative or exploitation-dominated strategies. In other words, lower index values correspond to higher risk propensity, while higher values reflect more cautious decision strategies. However, it is important to note that these values should not be analyzed in absolute terms, as the optimal share of choices is not known.

Imaging methods

fMRI acquisition

The MRI and fMRI data were acquired in 2021-2022 at the International Tomography Center, Novosibirsk, Russia, using the 3 T Ingenia scanner (Philips, BEST, Netherlands) with a 16-channel head coil. Participants could see the stimuli on a screen of an MR-compatible display through an oblique mirror mounted on the top of a head coil. Subjects gave their responses by pressing one of two MR-compatible hand-held buttons. All participants were instructed to lie in a scanner as still as possible (except for pushing buttons) and to breathe normally during the scanning sessions.

The reference anatomical T1 scans were recorded with Turbo Field Echo sequence, repetition time (TR) / echo time (TE) = 7.6 ms / 3.7 ms, flip angle (FA) = 8 degrees, slice thickness = 2 mm, spacing = 1 mm, total 181 axial slices with in-plane matrix 288 × 288 or 256 × 256, voxel size 0.87 × 0.87 × 1 mm3 or 0.98 × 0.98 × 1 mm3.

Functional T2* scans were acquired using the Echo Planar Imaging sequence, TR / TE = 1,510 ms / 35 ms, FA = 70 degrees, slice thickness = 4 mm, gap = 0.4 mm, total of 30 axial slices with in-plane matrix 112x112, voxel size 1.96 × 1.96 × 4.4 mm3. Two sessions of the functional data were analyzed for each participant, 200 volumes each, 604 s in total. The first 3 volumes of each session were discarded to provide steady magnetization.

fMRI data processing

Data processing was performed using MATLAB (Mathworks, Inc.) and SPM12 (Welcome Trust Center for Neuroimaging, UCL) software. First, DICOM data were converted to NIfTI format. Functional data were motion corrected and slice-timing corrected. Then, structural images were skull-stripped to avoid co-registration errors and registered to the first functional volume. Functional data were normalized to the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space, resampled to 2 × 2 × 2 mm3 voxels, and smoothed with Gaussian kernel with full width at half-height of 6 × 6 × 6 mm3. None of the participants was excluded from the analysis for excessive head motion.

The onsets and durations of task events were extracted from the event markers recorded for synchronization purposes during the fMRI session. In the first level models, the BOLD signal was modelled with the following event types: (1) the period prior to the first button press, assuming the chosen segment would be the same as in a previous run; (2) the same period, assuming a different choice; (3) the period of adjusting the target segment with pressing buttons, assuming at least two buttons pressed; (4) the early part of the ball run, up to 2 s prior to a center of the chosen segment; (5) the late part of the ball run, up to the stop button press; (6) positive feedback; (7) negative feedback. To avoid the influence of the run duration on the fMRI activity in event types 4 and 5, linear and quadratic parametric modulations of these conditions by a chosen sector were included in the model. All regressors of interest were convolved with the standard hemodynamic response function. The constant term and a set of Friston-6 head movement regressors per session were added, and volumes with the total framewise displacement \(\ge\) 1 mm were regressed out. All aforementioned regressors were included in the general linear model to estimate beta-weight maps corresponding to each condition.

Based on these beta-weights, three contrasts of interest were computed, i.e., Pre-choice period assuming the different vs same choice (condition 2 – condition 1); Late vs early part of the ball run (condition 5 – condition 4); and Feedback on success vs failure (condition 6 – condition 7). These individual contrasts entered the second-level analysis that comprised a simple one-sample t-test and regression with z-transformed EI variable. The primary regression analysis involved the condition 6 – condition 7 contrast. The similar analyses of two other contrasts were considered exploratory.

The significance level was set at p<0.001, uncorrected on voxel level with subsequent cluster-level correction (p<0.05 FWE-corrected using standard Gaussian random field-based approach implemented in the SPM to introduce the correction). Anatomical regions were identified using the Automated Anatomical Labelling atlas, version 3.1. xjview plugin for MATLAB was used to create cluster reports and to generate slice images.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the osf.io repository without any restriction: https://osf.io/cr2fm/files/vjn3m.

References

Charness, G., Gneezy, U. & Imas, A. Experimental methods: Eliciting risk preferences. J. Econ. Behav. Organ.87, 43–51 (2013).

Frey, R., Pedroni, A., Mata, R., Rieskamp, J. & Hertwig, R. Risk preference shares the psychometric structure of major psychological traits. Sci. Adv.3, e1701381 (2017).

Levy, I., Snell, J., Nelson, A. J., Rustichini, A. & Glimcher, P. W. Neural representation of subjective value under risk and ambiguity. J. Neurophysiol.103, 1036–1047 (2010).

Tom, S. M., Fox, C. R., Trepel, C. & Poldrack, R. A. The neural basis of loss aversion in decision-making under risk. Science315, 515–518 (2007).

Glimcher, P. W. Decisions, Uncertainty, and the Brain: The Science of Neuroeconomics (MIT press, 2004).

Shou, Y. & Olney, J. Assessing a domain-specific risk-taking construct: A meta-analysis of reliability of the Dospert scale. Judgm. Decis. Mak.15, 112–134 (2020).

Kwon, M. S., Vorobyev, V., Moe, D., Parkkola, R. & Hämäläinen, H. Brain structural correlates of risk-taking behavior and effects of peer influence in adolescents. PloS one9, e112780 (2014).

Bechara, A., Damasio, A. R., Damasio, H. & Anderson, S. W. Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cognition50, 7–15 (1994).

Blanchard, T. C. & Gershman, S. J. Pure correlates of exploration and exploitation in the human brain. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci.18, 117–126 (2018).

Pascucci, D., Hickey, C., Jovicich, J. & Turatto, M. Independent circuits in basal ganglia and cortex for the processing of reward and precision feedback. NeuroImage162, 56–64 (2017).

Niv, Y., Edlund, J. A., Dayan, P. & O’Doherty, J. P. Neural prediction errors reveal a risk-sensitive reinforcement-learning process in the human brain. J. Neurosci.32, 551–562 (2012).

Kable, J. W. & Glimcher, P. W. The neural correlates of subjective value during intertemporal choice. Nat. Neurosci.10, 1625–1633 (2007).

Delgado, M., Locke, H., Stenger, V. A. & Fiez, J. Dorsal striatum responses to reward and punishment: effects of valence and magnitude manipulations. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci.3, 27–38 (2003).

Hsu, M., Krajbich, I., Zhao, C. & Camerer, C. F. Neural response to reward anticipation under risk is nonlinear in probabilities. J. Neurosci.29, 2231–2237 (2009).

O’Doherty, J. P., Deichmann, R., Critchley, H. D. & Dolan, R. J. Neural responses during anticipation of a primary taste reward. Neuron33, 815–826 (2002).

Domenech, P., Rheims, S. & Koechlin, E. Neural mechanisms resolving exploitation-exploration dilemmas in the medial prefrontal cortex. Science369, eabb0184 (2020).

Overmeyer, R., Kirschner, H., Fischer, A. G. & Endrass, T. Unraveling the influence of trial-based motivational changes on performance monitoring stages in a flanker task. Sci. Rep.13, 19180 (2023).

Ma, S., Zang, Y., Cheung, V. & Chan, C. C. Importance of punishment frequency in the iowa gambling task: an fmri study. Brain Imaging Behav.9, 899–909 (2015).

Jauhar, S. et al. Brain activations associated with anticipation and delivery of monetary reward: A systematic review and meta-analysis of fmri studies. PLoS One16, e0255292 (2021).

Fukui, H., Murai, T., Fukuyama, H., Hayashi, T. & Hanakawa, T. Functional activity related to risk anticipation during performance of the iowa gambling task. Neuroimage24, 253–259 (2005).

Halfmann, K., Hedgcock, W., Bechara, A. & Denburg, N. L. Functional neuroimaging of the iowa gambling task in older adults. Neuropsychology28, 870 (2014).

Mancuso, L. et al. Tasks activating the default mode network map multiple functional systems. Brain Struct. Funct.227, 1711–1734 (2022).

Murd, C., Moisa, M., Grueschow, M., Polania, R. & Ruff, C. C. Causal contributions of human frontal eye fields to distinct aspects of decision formation. Sci. Rep.10, 7317 (2020).

Trojano, L. et al. Coordinate and categorical judgements in spatial imagery: an fmri study. Neuropsychologia40, 1666–1674 (2002).

Wang, J. et al. Convergent functional architecture of the superior parietal lobule unraveled with multimodal neuroimaging approaches. Hum. Brain Mapp.36, 238–257 (2015).

Hutchison, R. M. et al. Functional connectivity of the frontal eye fields in humans and macaque monkeys investigated with resting-state fmri. J. Neurophysiol.107, 2463–2474 (2012).

Knutson, B. & Greer, S. M. Anticipatory affect: neural correlates and consequences for choice. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci.363, 3771–3786 (2008).

Oldham, S. et al. The anticipation and outcome phases of reward and loss processing: A neuroimaging meta-analysis of the monetary incentive delay task. Hum. Brain Mapp.39, 3398–3418 (2018).

Stimulus-Action-Reward, C. N. D. Different neural correlates of reward expectation. Learning95, 948–959 (2006).

Grahn, J. A., Parkinson, J. A. & Owen, A. M. The cognitive functions of the caudate nucleus. Prog. Neurobiol.86, 141–155 (2008).

Schultz, W. Reward functions of the basal ganglia. J. Neural Transm.123, 679–693 (2016).

Sescousse, G., Caldú, X., Segura, B. & Dreher, J.-C. Processing of primary and secondary rewards: a quantitative meta-analysis and review of human functional neuroimaging studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev.37, 681–696 (2013).

Votinov, M., Pripfl, J., Windischberger, C., Sailer, U. & Lamm, C. Better you lose than i do: neural networks involved in winning and losing in a real time strictly competitive game. Sci. Rep.5, 11017 (2015).

Seger, C. A. & Cincotta, C. M. The roles of the caudate nucleus in human classification learning. J. Neurosci.25, 2941–2951 (2005).

Montague, P. R. & Berns, G. S. Neural economics and the biological substrates of valuation. Neuron36, 265–284 (2002).

Serra, D. Decision-making: from neuroscience to neuroeconomics–an overview. Theory Decis.91, 1–80 (2021).

Lin, A., Adolphs, R. & Rangel, A. Social and monetary reward learning engage overlapping neural substrates. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci.7, 274–281 (2012).

Salehinejad, M. A., Ghanavati, E., Rashid, M. H. A. & Nitsche, M. A. Hot and cold executive functions in the brain: A prefrontal-Cingular network. Brain Neurosci. Adv.5, 23982128211007770 (2021).

Neta, M., Nelson, S. M. & Petersen, S. E. Dorsal anterior cingulate, medial superior frontal cortex, and anterior insula show performance reporting-related late task control signals. Cereb. Cortex27, 2154–2165 (2017).

Shenhav, A., Botvinick, M. M. & Cohen, J. D. The expected value of control: an integrative theory of anterior cingulate cortex function. Neuron79, 217–240 (2013).

Azab, H. & Hayden, B. Y. Correlates of economic decisions in the dorsal and subgenual anterior cingulate cortices. Eur. J. Neurosci.47, 979–993 (2018).

Palomero-Gallagher, N. et al. Human pregenual anterior cingulate cortex: structural, functional, and connectional heterogeneity. Cerebr. Cortex29, 2552–2574 (2019).

Rolls, E. T., Cheng, W. & Feng, J. The orbitofrontal cortex: reward, emotion and depression. Brain Commun.2, fcaa196 (2020).

Loh, M. K. & Rosenkranz, J. A. The medial orbitofrontal cortex governs reward-related circuits in an age-dependent manner. Cerebr. Cortex33, 1913–1924 (2023).

Jenni, N. L., Rutledge, G. & Floresco, S. B. Distinct medial orbitofrontal-striatal circuits support dissociable component processes of risk/reward decision-making. J. Neurosci.42, 2743–2755 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Dissociating value-based neurocomputation from subsequent selection-related activations in human decision-making. Cerebr. Cortex32, 4141–4155 (2022).

Rolls, E. T., Wan, Z., Cheng, W. & Feng, J. Risk-taking in humans and the medial orbitofrontal cortex reward system. NeuroImage249, 118893 (2022).

Kuhnke, P. et al. The role of the angular gyrus in semantic cognition: a synthesis of five functional neuroimaging studies. Brain Struct. Funct.228, 273–291 (2023).

Dobryakova, E. & Smith, D. V. Reward enhances connectivity between the ventral striatum and the default mode network. Neuroimage258, 119398 (2022).

Brandman, T., Malach, R. & Simony, E. The surprising role of the default mode network in naturalistic perception. Commun. Biol.4, 79 (2021).

Deza Araujo, Y. I. et al. Risk seeking for losses modulates the functional connectivity of the default mode and left frontoparietal networks in young males. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci.18, 536–549 (2018).

Smallwood, J. et al. The default mode network in cognition: a topographical perspective. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.22, 503–513 (2021).

Fuentes-Claramonte, P. et al. Shared and differential default-mode related patterns of activity in an autobiographical, a self-referential and an attentional task. Plos one14, e0209376 (2019).

Benningfield, M. M. et al. Caudate responses to reward anticipation associated with delay discounting behavior in healthy youth. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci.7, 43–52 (2014).

Matthews, S. C., Simmons, A. N., Lane, S. D. & Paulus, M. P. Selective activation of the nucleus accumbens during risk-taking decision making. Neuroreport15, 2123–2127 (2004).

Chakroun, K., Mathar, D., Wiehler, A., Ganzer, F. & Peters, J. Dopaminergic modulation of the exploration/exploitation trade-off in human decision-making. Elife9, e51260 (2020).

Krönke, K.-M. et al. Real-life self-control is predicted by parietal activity during preference decision making: A brain decoding analysis. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci.21, 936–947 (2021).

Hall, S. A. et al. Hypoactivation in the precuneus and posterior cingulate cortex during ambiguous decision making in individuals with hiv. J. Neurovirol.27, 463–475 (2021).

Tomov, M. S., Truong, V. Q., Hundia, R. A. & Gershman, S. J. Dissociable neural correlates of uncertainty underlie different exploration strategies. Nat. Commun.11, 2371 (2020).

Cockburn, J., Man, V., Cunningham, W. A. & O’Doherty, J. P. Novelty and uncertainty regulate the balance between exploration and exploitation through distinct mechanisms in the human brain. Neuron110, 2691–2702 (2022).

Zhou, Y. et al. The neural correlates of risk propensity in males and females using resting-state fmri. Front. Behav. Neurosci.8, 2 (2014).

Hu, B. et al. Being bold wisely: neural substrates underlying ability to exploit risk. Cerebr. Cortex33, 8431–8441 (2023).

Byrnes, J. P., Miller, D. C. & Schafer, W. D. Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull.125, 367–383 (1999).

Liu, Y., Bagaïni, A., Son, G., Kapoor, M. & Mata, R. Life-course trajectories of risk-taking propensity: A coordinated analysis of longitudinal studies. J. Gerontol.: Ser. B78, 445–455. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbac175 (2022) https://academic.oup.com/psychsocgerontology/article-pdf/78/3/445/49421388/gbac175.pdf.

Chen, D. L., Schonger, M. & Wickens, C. otree–an open-source platform for laboratory, online, and field experiments. J. Behav. Exp. Financ.9, 88–97 (2016).

Francetich, A. & Kreps, D. Choosing a good toolkit, i: Prior-free heuristics. J. Econ. Dyn. Control111, 103813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jedc.2019.103813 (2020).

Harada, T. The effects of risk-taking, exploitation, and exploration on creativity. PloS one15, e0235698 (2020).

Crosetto, P. & Filippin, A. The, “bomb’’ risk elicitation task. J. Risk Uncertain.47, 31–65 (2013).

Lawrence, N. S., Jollant, F., O’Daly, O., Zelaya, F. & Phillips, M. L. Distinct roles of prefrontal cortical subregions in the iowa gambling task. Cerebr. Cortex19, 1134–1143 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Andrey Savelov who performed MRI and fMRI data acquisition. Next, we want to acknowledge Peter Dayan and all participants of the 2023 neuro-seminars at Max Plank Institute and Higher School of Economics for their valuable discussions. We also express our gratitude to Philipp Chapkovski and Alexey Guzey for their aid in task scripting. Last, we should credit the principal idea behind the task used in our study to Prof. Vadim Petrovsky. This article was prepared within the framework of the Basic Research Program at HSE University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GC, AV, and PR designed the study, PR and GC collected the data, GC analyzed behavioral data, MM, RS, and PR analyzed the fMRI data, DB supervised and performed quality assurance of the fMRI analysis, all authors contributed to the interpretation of the results, GC and MM wrote the draft of the manuscript, all authors critically reviewed it and approved its submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chernov, G.V., Mel’nikov, M.Y., Belianin, A.V. et al. Default mode network activity is related to efficiency in a combined motion error and gambling task. Sci Rep 16, 4422 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34609-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34609-9