Abstract

This study investigates heat transfer coefficients during two-phase flow boiling of distilled water within a horizontal, rectangular mini-channel with asymmetric heating. The microchannel dimensions are 180 mm × 4 mm × 1.5 mm. Experimental observations of flow structures were made through a transparent channel wall. Experiments were conducted under low Reynolds number conditions (281 ≤ Re ≤ 499), with measurements of inlet pressure, pressure drop, volumetric flow rate, heater power supply parameters, and temperatures at various points. The employed model assumed negligible influence of material properties on temperature and time-independent heat transfer. The flow resistance based on the two-phase separated flow Lockhart–Martinelli model was used to determine the water velocity profile in the mini-channel. The velocity profile satisfied the Poisson equation. The copper block and working fluid temperature distributions were assumed to adhere to appropriate energy equations with suitable boundary conditions. The Trefftz method was applied to solve these equations, providing the water velocity profile and 2D temperature distributions. Based on the calculated temperature distributions, the Nusselt number at the heating surface-water interface was determined. The experimental results were subsequently compared with theoretical correlations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The increasing need to dissipate high heat fluxes from miniaturized industrial and domestic devices has driven demand for micro- and mini-scale cooling solutions. Power electronics and microprocessor electronics, in particular, require efficient cooling due to their high heat generation rates. Micro- and mini-channels with boiling flows, integrated directly into the heat-generating structures, are becoming common solutions1. Some cooling systems prioritize low pumping power and, consequently, low Reynolds number flows2,3. Flow boiling heat transfer, known for its high heat transfer coefficients, is well-suited for these conditions.

In engineering modelling, a direct heat conduction problem (DHCP) is defined by its governing equation, boundary conditions, material properties, and geometric characteristics. When even one of these elements are unknown, it becomes an inverse heat conduction problem (IHCP). In the paper the Trefftz method was applied to numerically analyze experimental data on water boiling flow within a single, asymmetrically heated, rectangular mini-channel.

The experiment focused on low Reynolds number boiling flow in a rectangular mini-channel. The authors aimed to determine the heat transfer coefficient and other thermal and flow parameters. Lillo G. et al.4 investigated similar topics, presenting data on flow boiling heat transfer and vapor quality at dry-out for refrigerant R1233zd(E). By introducing a correction for asymmetric flows to their original model, the modified Cioncolini and Thome5 approach achieved a mean absolute error (MAE) of 7.40% compared to the entire annular flow database considered in the paper.

Kandlikar and Balasubramanian6 studied low flow rate boiling in small channels, resulting in laminar flow. They modified the Kandlikar correlation for large-diameter pipes7,8 to suit mini-channels, incorporating the laminar single-phase heat transfer coefficient for liquid flow. The correlation was further extended to microchannels, emphasizing nucleate boiling as the dominant component. A comparison of heat transfer coefficient trends with vapor quality in mini- and micro-channels revealed high agreement betweenexpected and observed values in both laminar and deep laminar regions.

Shah9 introduced a new correlation, which was validated using a comprehensive dataset covering a wide range of conditions in both small and large channels. The dataset included 42 fluids flowing through single and multi-channels with diameters ranging from 0.38 mm to 41 mm. These channels had various shapes (rectangular, round, triangular), heating configurations (partial, full), and spatial locations (horizontal, vertical). The proposed correlation achieved a mean absolute deviation (MAD) of 18.8% and outperformed existing correlations in terms of accuracy.

Ma X. et al.10 presented a novel comprehensive heat transfer correlation for estimating heat transfer coefficients during saturated/subcooled flow boiling in micro/mini-channels. The hydraulic diameters of these channels ranged from 0.1 to 3 mm. The dataset covered a variety of operational conditions, including heat flux, reduced pressure, mass flux and vapor quality. Six established flow boiling heat transfer correlations were evaluated using the micro/mini-channel data points. However, these correlations proved inaccurate due to high liquid subcooling and heat flux. To address this, a new predictive correlation was developed based on the current dataset, categorizing flow boiling into three stages: subcooled boiling, developed nucleate boiling, and nucleate boiling deterioration. The proposed model accurately predicted over 80% of data points within a ± 30% error margin.

Zhang W. et al.11 proposed a heat transfer correlation for flow boiling at low liquid Reynolds numbers in small-diameter channels. This correlation combined nucleate boiling and forced convection mechanisms, using terms derived from the Forster and Zuber12 pool boiling correlation and the Hewitt and Hall-Taylor13 annular flow model. The correlation exhibited satisfactory performance when compared to a comprehensive database, with mean deviation and RMS errors of 19.1% and 24.3%, respectively, across various experimental conditions, such as different flow orientations and channel geometries for several fluids. The authors noted that existing turbulent flow boiling correlations, such as Chen’s14, Schrock and Grossman’s15, and Dengler and Addoms’16, can be obtained from a generalized version of their newly developed correlation.

This paper aims to develop and solve a two-dimensional model for boiling heat transfer in an asymmetrically heated, horizontal rectangular mini-channel. The presented energy equations, with corresponding boundary conditions, led to direct and inverse Cauchy-type problems, one in the solid copper block and the other in the fluid. Inverse problems are known for their sensitivity to input data and ill-posed nature, often leading to unstable solutions17. Therefore, the calculation methods must prioritize stability and accuracy, which are characteristics of Trefftz function-based methods. These methods offers several advantages, making it valuable for solving both direct and inverse problems engineering. A key strength is that the solution exactly satisfies the governing differential equation, ensuring high accuracy. Calculations are also relatively simple, as the method typically uses polynomial T-functions. Another advantage is flexibility in handling various boundary conditions - from temperature and flow to discrete or continuous conditions. Like any computational method the method has limitations. It only applies directly to linear partial differential equations, though combining it with methods like homotopy perturbation or Picard iteration allows solving some nonlinear problems. Another challenge is the Runge phenomenon - oscillations at boundaries of the domain when too many T-functions are used. This can be reduced through adjustment calculus, though it remains an issue. Notably, combining the Trefftz method with the Finite Element Method (FEM) helps mitigate this, as FEM generally requires fewer T-functions.

This study employed the Trefftz method with two sets of T-functions to determine (a) the water velocity profile within the mini-channel, (b) the 2D temperature distributions for the heated copper block and the flowing water. The applied methods are meshless analytical-numerical techniques that approximate the solution to the governing equation using a linear combination of Trefftz functions. The coefficients of this combination are determined using the known boundary conditions.

Comparisons between Trefftz function method results and exact solutions of heat transfer problems can be found in18,19, which also evaluate the accuracy and stability of the obtained solutions. The relative errors of temperature identification did not exceed 2.59% (for errorless data) and 20.09% (for noisy data at 0.09 standard deviation). Papers20,21,22,23,24,25,26 compare the results of Trefftz function-based numerical solutions to those obtained using other methods, such as energy balance equations20, Fourier’s law21, radial functions22, Fourier transform23, numerical simulations24, and correlation equations25,26. The significant differences were observed when comparing the heat transfer coefficient (HTC) determined using the Trefftz method and the correlation equations. The maximum relative error between the experimental results and those predicted using HTC correlations ranged from 7% to even 50%, with higher values occurring for two-phase flow26. Hybrid methods combining Trefftz functions with other computational methods (e.g., detailed solution method, Picard iteration method, radial functions, homotopy perturbation method) are discussed in27. More information on Trefftz methods and their applications in solving direct and inverse engineering problems is included in papers28,29,30.

A crucial aspect of this study’s experimental component was selecting a suitable method to measure the void fraction during boiling in a mini-channel. The methods can be categorized into the following groups31:

-

electrical methods, based on measuring the two-phase structures’ electrical capacitance, resistance, or impedance,

-

acoustic methods,

-

optical methods,

-

X-ray methods, and.

-

image-based methods.

Electrical capacitance methods are suitable for nonconductive fluids. The dielectric constant of the boiling fluid depends on void fraction and can be measured using standard techniques32,33,34. However, due to the small size of the mini-channel, changes in dielectric constant may be minimal, potentially below the sensitivity limits of standard instruments.

For electrically conductive working fluids, resistance or impedance can be measured between electrodes in the two-phase mixture31. Both resistance and impedance are functions of void fraction.

Acoustic methods measure the attenuation or reflection of acoustic signals from two-phase structures as a function of void fraction. These signals typically fall within the audible and ultrasonic frequency ranges35,36.

Optical methods utilize a visible light detector and illuminator in a transparent-walled channel. Phase boundaries are identified by changes in light intensity, which affect the detector’s electrical current37,38. These methods are well-suited for counting regular two-phase structures (bubbles) in transparent channels.

X-ray methods use X-rays to record images of two-phase structures for analysis. However, these methods are less commonly used due to the specialized equipment and safety requirements.

Image-based methods record sequences of two-phase structure images using a high-speed film camera39. These methods require at least one transparent surface on the control volume and high-intensity light sources due to the short exposure times. Computer codes are used to analyze the recorded images, with a key function identifying interfacial boundaries in two-phase structures. A distinguishing feature of image-based methods is the ability to determine local void fraction. Based on prior experience40 and the methods’ relative simplicity, image-based methods were used to obtain measurement data for this study.

This study has two main objectives. First, it experimentally investigates flow boiling of water in a horizontally oriented, asymmetrically heated rectangular mini-channel. Key measurements include temperatures, flow resistance, electrical input parameters, void fraction, and mass flux. Second, it applies and validates the Trefftz method as a stable and efficient semi-analytical approach for solving direct and inverse heat conduction problems in the heating block and refrigerant41,42,43,44,45. The analysis includes velocity profiles, temperature distributions, and Nusselt numbers, which are compared with theoretical correlations. The study therefore combines an experimental approach with computational analysis using the Trefftz method. The experiment provides essential, real-world validation of the computational model, a feature not achievable through CFD simulations. This integration of methodologies is not a conventional strategy for problems concerning flow boiling in mini-channels. Therefore, the authors consider this paper to be a significant contribution to the field.

Data and methodology

The main flow loops and their components are presented in Fig. 1.

Flow loop: 1 – measurement module with the mini-channel, 2 – temperature and pressure sensors [Czaki K-type, Kobold], 3 – LED lighting, 4 – cooler, 5 – rotameter [Heinrichs], 6 – filter, 7 – gear precision pump [Tuthill DGS 38 PP], 8 – pressure control, 9 – compressed air tank, 10 – compressed air valves, 11 – preheater, 12 – computer for experiment controlling and LabView software, 13 – high speed camera [Vision Research, Phantom 711], 14 – DC power supply [direct current TDK Lambda], 15 - Timer based on ATmega 32 microprocessor, 16 – facility control unit [NI cDAQ-9178 chassis], Pca. – compressed air pressure sensor. Drawing made with Corel Designer 2022 software, https://www.coreldraw.com.

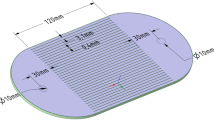

Figure 2 shows the experimental setup, featuring a mini-channel fabricated by bonding three transparent glass plates and a cuboidal copper block. Figure 3 shows a detailed view of the mini-channel and the measurement module. The copper block serves as both a sturdy foundation and a mass heater, as depicted in Fig. 4. Four planar resistance heaters, attached to steel substrates and sintered onto the copper block, were powered by a GEN 50 − 30 TDK Lambda power supply. This generated the thermal energy required to initiate flow boiling within the channel. The mini-channel walls were constructed of Optiwhite glass, allowing sufficient illumination. A high-speed camera recorded the two-phase boiling structures.

View of the experimental configuration. The annotations correspond identically to those presented in Fig. 1. Drawing made with Corel Designer 2022 software, https://www.coreldraw.com.

To prevent uncontrolled heating from incandescent light, we used a proprietary LED system (Fig. 1) featuring a Citizen CL-L233-HC13L1-C LED diode. The mini-channel components were bonded with LOCTITE® SI 5145 adhesive. The rectangular mini-channel, measuring 180 mm in length, 4 mm in width, and 1.5 mm in depth, had a cross-sectional area of 6 mm² (Fig. 4). Five thermocouples (Czaki TP-201, 0.5 mm diameter) were installed: one at the inlet, one at the outlet, and three within the copper block (Fig. 4). Two pressure sensors 0–2.5.5 bar were placed at the inlet and outlet. A precision gear pump circulated distilled water at a maximum flow rate of 1.5·10− 7 m³/s, ensuring a stable laminar flow (Reynolds number range of 281 ≤ Re ≤ 499). These low Reynolds number conditions are common in miniature cooling systems for electronic devices. The experimental stand is also presented in the video attached to the article.

View of the mini-channel and measuring module, markings: 1a – mini-channel, 17 – LED lighting radiator, other markings as in Fig. 1. Drawing made with Corel Designer 2022 software, https://www.coreldraw.com.

a General view of the mini-channel and thermocouples placed inside the copper block, b longitudinal cross-sections. Drawing made with Corel Designer 2022 software, https://www.coreldraw.com.

The experimental measurement procedure conducted on the stand (Fig. 1) involved the following steps:

-

a.

Circulating the fluid through the mini-channel at a predetermined volumetric flow rate, inlet temperature, and pressure.

-

b.

Gradually heating the fluid in two stages: first with a preheater to reach the boiling point, followed by a copper heating block for the mini-channel.

-

c.

Collecting key thermal and flow data, including the water’s volumetric flow rate, inlet and outlet temperatures, inlet pressure, pressure drop along the mini-channel, heater power input, and temperatures at three points on the copper heater. Each measurement session lasted 6–7 s, during which all experimental data were recorded and saved to a computer disk.

-

d.

Capturing two-phase flow structures using a high-speed video camera and storing the footage on a computer disk.

The LabView software controlled the experiment, continuously reading key parameters: inlet/outlet temperatures, copper block temperatures, inlet pressure, pressure drop, heating power, and volumetric flow rate. The program also accessed tabulated working fluid properties from Refprop. Each measurement involved the system being stabilized with the desired input parameters. Experimental data and working fluid properties were recorded within a brief 6–7 s window. Subsequently, a sequence of 100 high-speed images (7000 frames per second) was captured by the camera. The sequence was limited to 100 images due to the time constraints of saving images to the computer. The high-speed camera images were utilized to determine the local void fraction within the channel through a specialized image analysis procedure in the MATLAB environment, as referenced in papers40,46,47,48. Table 1 summarizes the experimental thermal-flow parameters and their uncertainties.

The system incorporated high-precision sensors and a computer for data acquisition to minimize temperature measurement uncertainty. The LabView platform facilitated efficient calibration of the temperature measurement channels. Figure 5; Table 2 illustrate a calibration curve for one of the thermocouples used in the experiment. Employing National Instruments measurement modules and K-type thermocouples, the calibration process maintained a maximum measurement uncertainty of 0.5 K.

Under certain conditions, the evaporation front within the mini-channel exhibited stochastic reversals of its movement direction. This phenomenon occurred during experiments with low mass fluxes (G ≤ 72 kg/(s m²)) and high heat fluxes (q ≥ 186 kW/m²) while maintaining constant mass flux and electrical power supply. The observed reversals were accompanied by fluctuations in both inlet and outlet pressures and temperatures, as depicted in Fig. 6.

The phenomenon observed by the authors during experimental investigations is frequently encountered in experiments concerning boiling in mini-channels49,50,51. It is characterized by a local pressure increase on the heating surface, which is associated with the formation, subsequent expansion, and often the coalescence of vapor bubbles on the heating surface. A large and sudden increase in bubble volume causes flow instabilities, including local flow reversal related to the vapor bubble’s expansion. This phenomenon is particularly interesting due to the temporal dependencies in the periodic flow disturbances. The authors plan to undertake this issue for consideration in future experimental research and computational analyses.

Mathematical model and numerical method

Heat transfer mathematical model

In study46, a three-dimensional model was developed to determine the temperature distribution in a copper block, and the analysis of numerical results showed that the temperature did not vary along the width (it was constant), so this direction was considered negligible and omitted from the model. The mathematical model presented below is an adaptation of the models described in46. Heat transfer within the heater body was considered in three dimensions: height, length, and width. Conversely, heat transfer in the copper block and mini-channel was limited to height and length. Our analysis revealed negligible temperature variations within the heater body along the copper block’s width. Consequently, in the 2D model presented, the heating copper block’s temperature is influenced solely by vertical position (y) and horizontal position along its length (x). As in47, we assume a time-independent heat transfer process with constant material and liquid properties within the experimental module. Additionally, we postulate that the heating block temperature distribution adheres to the Laplace Eq.

where \(\:\left(x,y\right)\in\:{{\Omega\:}}_{1}=\left\{\left(x,y\right),\:0<x<L,\:0<y<{H}_{2}\right\}.\:\)In Eq. (1), we assume that both vertical walls surrounding the copper block are insulated. The temperature of the heating block, is known at three measurement points (xi, Hm), where i = 1, 2, 3. Furthermore, as outlined in47, we consider the following boundary conditions at the fluid-to-copper heater contact surface at both ends of the mini-channel

where Tapprox means the approximation of temperature measurements with a polynomial.

Unlike in48, we assume in subsequent calculations that the entire heat flux, q(x), generated by the four.

resistance heaters (see Fig. 3) is exclusively transferred to the copper block, i.e.,

where \(\:{\bigcup\:}_{i=1}^{4}{D}_{i}=\left[2.5;\hspace{0.33em}41.5\right]\cup\:\left[47.5;\hspace{0.33em}86.5\right]\cup\:\left[93.5;\hspace{0.33em}132.5\right]\cup\:\left[139.5;\hspace{0.33em}178.5\right]\).

The presented time-independent heat transfer model within the experimental module assumes that the boiling water flow in the horizontal mini-channel is laminar with a constant mass flux density. Additionally, the fluid temperature satisfies the energy equation in the form

where \(\:\left(x,y\right)\in\:{{\Omega\:}}_{2}=\left\{\left(x,y\right),\:0<x<L,\:{H}_{2}<y<{H}_{3}\right\}\).

For Eq. (4), the boundary conditions are as follows:

-

the fluid temperature at the inlet (Tin) and outlet (Tout) of the mini-channel is known,

-

the fluid temperature at the interface with the cooper block satisfies the condition.

Only one component of the fluid velocity, v(y,z), is non-zero and satisfies the Navier-Stokes equation in the specified form

where the dynamic viscosity of the mixture was assumed to be equal to that of the liquid phase. The Dirichlet boundary conditions for Eq. (6) were defined as follows

In the mathematical model, all considerations were limited to the length and height of the mini-channel. Consequently, the fluid velocity in Eq. (4) is equivalent to the average velocity calculated using the following formula

Intensive heating of the subcooled liquid flowing into the mini-channel induces convection evaporation. As the void fraction (ϕ(x)) increases due to the heat flux transferred to the fluid layer contacting the heater, a two-phase mixture forms within the mini-channel. The two-phase mixture reduces heat transfer from the heater block to the fluid. The heat flux absorbed by the vapor fraction results in vapor superheating, which is accounted for in the mean fluid temperature (Tf, ave)42.

Given the adopted assumptions and knowledge of the temperature distributions of the heating surface and fluid, the Nusselt number at the contact surface can be determined from the following condition

where the reference temperature Tf, ave was calculated as in42.

Trefftz method

The presented mathematical model addresses inverse heat conduction problems (IHCPs) in two distinct domains: the copper block and the fluid. These domains have different shapes and parameters. Additionally, a direct problem arises from solving Eq. (6).

Through the simultaneous solution of Eqs. (1) and (4), we derive a two-dimensional temperature profile within the heated copper block and the water, the heat flux transferred from the block to the working fluid, and the Nusselt number at the copper-fluid interface.

Two sets of T-functions were utilized in these computations: harmonic functions, representing solutions to the Laplace equation, and T-functions suitable for the energy Eq. (4), assuming a known polynomial velocity profile.

Harmonic polynomials, as defined by the formula

were used to obtain an approximate solution for Eqs. (1) and (6). The initial step in the calculations involved determining the temperature distribution of the copper block, following a procedure similar to that described in48. Subsequent stages of the calculation procedure included:

-

1.

Determining the flow resistance and then the liquid velocity based on the solution of Eq. (6)

-

2.

Calculating its average value using Eq. (8)

-

3.

Generating the T-function for Eq. (4)

- 4.

-

5.

Finally, computing the Nusselt number according to Eq. (9).

The solution to Eq. (6), derived using the Trefftz method, serves as the foundation for constructing the T-function in Eq. (4), as detailed in25.

Introducing into Eq. (6) dimensionless variables

where \(\:0\le\:\xi\:\le\:K,\:0\le\:\varsigma\:\le\:1\) and \(\:K=\frac{{H}_{3}-{H}_{2}}{W}\) is the cross-sectional aspect ratio characterizing the geometry of the mini-channel and substituting the derivative\(\:\:\:\frac{\partial\:p}{\partial\:x}\) with the expression \(\:\frac{{\Delta\:}p}{L}\), i.e. \(\:\frac{\partial\:p}{\partial\:x}\approx\:\frac{{\Delta\:}p}{L}\), allows Eq. (6) to be expressed as.

where \(\:0\le\:\xi\:\le\:K,\:0\le\:\varsigma\:\le\:1\) and \(\:K=\frac{{H}_{3}-{H}_{2}}{W}\) is the cross-sectional aspect ratio characterizing the geometry of the mini-channel and substituting the derivative\(\:\:\frac{\partial\:p}{\partial\:x}\) with the expression \(\:\frac{{\Delta\:}p}{L}\), i.e. \(\:\frac{\partial\:p}{\partial\:x}\approx\:\frac{{\Delta\:}p}{L}\:\) and the total flow resistance \(\:\frac{{\Delta\:}p}{L}\)in two-phases flow was calculated using the Lockhart–Martinelli model similarly to52.

Following the adopted notations, the Dirichlet boundary conditions (7) take the form.

An approximate solution to Eq. (12) can be expressed as the sum of the particular solution to Eq. (12) and a linear combination of harmonic polynomials \(\:{u}_{i,0}\left(\xi\:,\varsigma\:\right)\), i.e.

Minimizing the functional

allows for the determination of the coefficients of the linear combination \(\:{a}_{n}\).

The calculated liquid velocity within the channel is a polynomial that precisely satisfies Eq. (12) and approximately adheres to the boundary conditions (13). The mathematical model assumed negligible variations in physical parameters across the width of the measurement module. Consequently, in subsequent considerations of Eq. (4), the velocity is assumed to be Eq. (8). For this determined velocity profile, T-functions are generated for the energy Eq. (4) according to25:

where\(\:m=\left[n/2\right]\) ([.] denotes the greatest integer function) and the functions \(\:{u}_{n,i}\left(x,y\right)\) for n = 1,2,…satisfy the condition

The inverse of Laplace operator \(\:{L}^{-1}\) for monomials is defined as follows20

The properties of functions \(\:{w}_{n}\left(x,y\right)\) and \(\:{u}_{n,i}\left(x,y\right)\) are thoroughly discussed in25.

Results

Experimental data

Numerical calculations were performed for a range of heat flux densities produced by the four external flat heaters, spanning 216 ≤ q ≤ 340 kW/m² (Fig. 7). Water mass flux varied from 60 kg/(s m²) to 103 kg/(s m²), and other experimental parameters, including their measurement uncertainties, are listed in Table 1. Local void fraction values along the mini-channel length were determined as described in53. In the numerical calculations, experimental void fractions were approximated by a logistic curve (Fig. 8), resulting in exceptionally high coefficients of determination for the considered cases (average coefficient of determination R² = 0.9).

The arrow in Fig. 7 indicates the direction of increasing void fraction. An increase in heat flux or a decrease in mass flux leads to an increase in the void fraction.

Flow resistance and fluid velocity calculations

In the initial stage of the analysis, the flow resistance was evaluated using the two-phase separated flow model proposed by Lockhart and Martinelli54. Given the horizontal orientation of the mini-channel, the gravitational component of the pressure drop was neglected. It was assumed that the total pressure gradient of the two-phase mixture \(\:{\left(\frac{\varDelta\:p}{\varDelta\:L}\right)}_{TP}\) is the sum of the pressure gradient due to wall friction\(\:{\:\left(\frac{\varDelta\:p}{\varDelta\:L}\right)}_{T}\) and that resulting from the change in momentum, i.e., acceleration pressure drop \(\:{\left(\frac{\varDelta\:p}{\varDelta\:L}\right)}_{A}\), according to the following formula

The acceleration pressure drop was determined following the procedure analogously to55 while the frictional pressure drop was estimated using the relationship given in1

In Eq. (20), the superficial velocity of the liquid phase \(\:{j}_{l}\:\) and the two-phase friction multiplier \(\:{{\Phi\:}}_{l}^{2}\) were calculated following the methodology presented in55. The Fanning friction factor f was determined according to the approach described in56.

Figure 9 summarizes the experimental flow resistance values and those calculated from the separated Lockhart-Martinelli model. For most cases, the relative differences were below 30% and the largest errors were observed for the lowest heat fluxes. However, two extreme cases exhibited significant differences of 203% (run 9) and 240% (run 13), attributed to observed instabilities in the water and vapor flow through the mini-channel. These instabilities involved alternating channel filling with vapor or liquid, accompanied by pressure and temperature pulsations at the mini-channel inlet and outlet.

Flow resistance was used to determine the velocity component v(y, z) (Fig. 10a) and average velocity \(\:{v}_{x}\left(y\right)\) (Fig. 10b) from Eq. (6) without distinguishing between the liquid and gas phases. This approach reduced the computational complexity while preserving the correct trends in the variation of flow parameters. The number of Trefftz functions used to determine the velocity was selected to ensure that the value of the functional \(\:F\left({a}_{1},\dots\:,{a}_{N}\right)\) was below 10− 3, as shown in Fig. 11.

Values of the error functional \(\:F\left({a}_{1},\dots\:,{a}_{N}\right)\) (Eq. 15) depending on the number of T - functions for q = 299kW/m2, G = 72 kg/(m2s).

Nusselt number calculations

The heat transfer coefficient was calculated in a four-step process:

-

Void fractions were determined at specific cross-sections along the mini-channel using a method similar to53. A logistic curve, Fig. 8, approximated the void fraction distribution.

-

2D temperature profile within the heated copper block was calculated applying nine T-functions tailored for Eq. (1).

-

Given the liquid velocity profile and copper block temperature, the 2D water temperature profile was determined using the Trefftz method, employing T-functions defined by formula (16).

-

The Nusselt number was calculated using Eq. (9).

Figure 12 illustrates the 2D fluid temperature distribution obtained applying four T-functions.

Figures 13 and 14 illustrate the Nusselt number as a function of distance from the mini-channel inlet for all sixteen experiments. Figure 13 presents results for various mass fluxes, while Fig. 14 summarizes the Nusselt number for selected heat fluxes.

Analysis of the results in Figs. 13 and 14 revealed that the Nusselt number values ranged from 0.02 to 97, with higher values corresponding to higher heat fluxes. Additionally, the Nusselt number values decreased steadily with increasing distance from the mini-channel inlet. This trend was attributed to the growing void fraction of the vapor phase within the flow, which negatively impacted heat transfer between the copper block surface and the two-phase fluid.

Comparison of the experimental Nusselt numbers with correlations

The experimental Nusselt number values were calculated using T-functions, as outlined in Sect. 3.2. Three correlations developed explicitly for heat transfer in mini-channels were selected for comparison: Kandlikar correlation7, Mikielewicz correlation57, and Warrier et al. correlation58, Table 3.

The Nusselt number appearing in formulas (19)–(21) was calculated from the Dittus- Boelter59 relationship

The accuracy of the predicted correlation was evaluated using the maximum mean absolute error (MAE), defined by formula

Figures 15 and 16 compare the experimental Nusselt numbers determined from formula (9) with the results calculated from the correlations listed in Table 3.

Analysis of the results presented in Figs. 15 and 16 reveals that the Warrier et al.58 correlation provides the best fit among the indicated correlations, with a (MAE) of 15%. The Mikielewicz57 correlation follows with an MAE of 19%, and the Kandlikar correlation7 has an MAE of 33%.

The higher MAE for the Kandlikar correlation7 is likely due to its reliance on an extensive experimental database with a wide range of thermal and flow parameter variability and its applicability to mini-channels with hydraulic diameters significantly larger than those considered in this study. In contrast, the Warrier et al.58 and Mikielewicz57 correlations are designed explicitly for flows in mini-channels with small hydraulic diameters, typically not exceeding 1.2 mm58.

Almost all Nusselt number values calculated using the Warrier et al.58 and Mikielewicz57 correlations fall within ± 30% of the values calculated from formula (9). The analysis indicates that these correlations better fit experimental data with a narrower range of thermal and flow parameter variability.

Conclusions

The present study focused on the application of a two-dimensional inverse heat conduction method to analyze flow boiling in an asymmetrically heated horizontal mini-channel. The results obtained from the numerical model were compared with experimental measurements and theoretical correlations. Based on the conducted analyses, the following conclusions can be drawn:

-

1.

The two-dimensional approach to solving inverse heat conduction problems (IHCPs) in flow boiling of water within an asymmetrically heated horizontal mini-channel was validated against experimental data, confirming its reliability.

-

2.

The Trefftz method effectively determined: the pressure drop of the water in mini-chanel, the two-dimensional temperature distribution in both the heated copper block and the working fluid, as well as (indirectly) their temperature gradients and the local Nusselt number at the block–fluid interface.

-

3.

The local Nusselt number exhibits significant variation along the length of the mini-channel. It reaches a maximum at the channel inlet, where single-phase flow or nucleate boiling predominates, and decreases downstream due to the development of convective boiling and an increase in void fraction.

-

4.

An increase in heat flux leads to higher local Nusselt number values, whereas variations in pressure drop along the mini-channel have a negligible influence on heat transfer performance.

-

5.

The numerical predictions obtained using the proposed model and the Trefftz method were compared with three existing theoretical correlations. The predicted Nusselt number values from the developed model were comparable to those obtained using the selected empirical correlations. The results showed satisfactory agreement, with the best fit observed for the correlation proposed by Warrier et al.

Future research will focus on both experimental and numerical investigations of time-dependent heat transfer under two-phase flow conditions in mini-channels.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- a :

-

Coefficient

- C :

-

Constant

- c p :

-

Specific heat capacity, J/(kg K)

- D:

-

Interval

- \({d}_{h}\) :

-

Hydraulic diameter, m

- DHCP:

-

Direct heat conduction problem

- F :

-

Functional

- f :

-

Fanning friction factor

- G :

-

Mass flux, kg/(s m2)

- g :

-

Gravity, m/s2

- H :

-

Height, m

- \({h}_{lv}\) :

-

Latent heat of vaporization, J/kg

- IHCP:

-

Inverse heat conduction problem

- j :

-

Superficial velocity

- K :

-

Cross-section aspect ratio

- L :

-

Length, m

- L :

-

Laplace operator

- M :

-

Number of data points

- MAE:

-

Maximum mean absolute error

- N :

-

Number of T- functions

- p :

-

Pressure, Pa

- q :

-

Heat flux, W/m2

- T :

-

Temperature, K

- u :

-

T- function (harmonic polynomial)

- \(\widetilde{u}\) :

-

Particular solution

- W :

-

Width, m

- \(w\) :

-

T- function

- v :

-

Velocity, m/s

- X :

-

Vapor quality

- x, y, z :

-

Coordinates, m

- \(\alpha\) :

-

Heat transfer coefficient, W/(m2K)

- Δ :

-

Difference

- μ:

-

Void fraction

- λ:

-

Thermal conductivity, W/(m K)

- φ:

-

Dynamic viscosity, kg/(m s)

- ρ:

-

Density, kg/m3

- \(\xi ,\varsigma\) :

-

Dimensionless variables

- \(\Phi\) :

-

Two-phase friction multiplier

- \(\Omega\) :

-

Domain

- A :

-

Accelerational

- approx :

-

Approximation

- ave :

-

Average

- C :

-

Copper block

- exp :

-

Experimental

- f :

-

Fluid

- in :

-

Inlet

- m :

-

Measurement

- l :

-

Liquid

- out :

-

Outlet

- pred :

-

Prediction

- sat :

-

Saturation

- sp :

-

Single phase

- T :

-

Frictional

- TP :

-

Total

- tp :

-

Two-phase

- v :

-

Vapor

- \(Bo=\frac{q}{G{h}_{lv}}\) :

-

Boiling number

- \(Co={\left(\frac{1-X}{X}\right)}^{0.8}{\left(\frac{{\rho }_{v}}{{\rho }_{f}}\right)}^{0.5}\) :

-

Convection number

- \(Fr=\frac{{G}^{2}}{{\rho }_{f}g {d}_{h}}\) :

-

Froud number

- \(Ja=\frac{{c}_{p,f}{\rho }_{f} ({T}_{sat,in}-{T}_{f,in})}{{\rho }_{v}{ h}_{lv}}\) :

-

Jacob number

- \(Nu=\frac{\alpha {d}_{h}}{{\lambda }_{f}}\) :

-

Nusselt number

- \(\mathit{Pr}=\frac{{\mu }_{f}{c}_{p,f}}{{\lambda }_{f}}\) :

-

Prandtl number

- \(Re=\frac{G{d}_{h}}{{\mu }_{f}}\) :

-

Reynolds number

References

Karayiannis, T. G. & Mahmoud, M. M. Flow boiling in microchannels: fundamentals and applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 115, 1372–1397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.08.063 (2017).

Kim, S. M. & Mudawar, I. Review of databases and predictive methods for pressure drop in adiabatic, condensing and boiling mini/micro-channel flows. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 77, 74–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2014.04.035 (2014).

Grabowski, M., Hożejowska, S. & Poniewski, M. E. Trefftz method-based identification of heat transfer coefficient and temperature fields in flow boiling in an asymmetrically heated rectangular mini-channel. Contemp. Issues Heat. Mass. Transf. Koszalin Univ. Technol. 1, 179–192 (2019).

Lillo, G., Mastrullo, R., Mauro, A. W. & Viscito, L. Flow boiling of R1233zd(E) in a horizontal tube: Experiments, assessment and correlation for asymmetric annular flow. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 129, 547–561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2018.09.117 (2019).

Cioncolini, A. & Thome, J. R. Void fraction prediction in annular two-phase flow. Int. J. Multiph. Flow. 43, 72–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmultiphaseflow.2012.03.003 (2012).

Kandlikar, S. G. & Balasubramanian, P. An extension of the flow boiling correlation to Transition, laminar, and deep laminar flows and microchannels. Heat. Transf. Eng. 25, 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/01457630490280425 (2004).

Kandlikar, S. G. A general correlation for saturated two-phase flow boiling heat transfer inside horizontal and vertical tubes. J. Heat. Transf. 102, 219–228. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.2910348 (1990).

Kandlikar, S. G. A model for predicting the two-phase flow boiling heat transfer coefficient in augmented tube and compact heat exchanger geometries. J. Heat. Transf. 13, 966–972 (1991).

Shah, M. M. New general correlation for heat transfer during saturated boiling in mini and macro channels. Int. J. Refrig. 137, 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2022.02.019 (2022).

Ma, X. et al. Saturated/subcooled flow boiling heat transfer inside micro/mini-channels: A new prediction correlation and experiment evaluation. Int J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 210, 124184 (2023).

Zhang, W., Hibiki, T. & Mishima, K. Correlation for flow boiling heat transfer at low liquid Reynolds number in small diameter channels. ASME J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 127, 1214–1221 (2005).

Forster, H. K. & Zuber, N. Dynamics of vapor bubbles and boiling heat transfer. AIChE J. 1, 531–535. https://doi.org/10.1002/aic.690010425 (1955).

Hewitt, G. & Hall-Taylor, N. S. Annular Two-Phase Flow (Pergamon, 1970).

Chen, J. C. Correlation for boiling heat transfer to saturated fluids in convective flow. Ind. Eng. Chem. Proc. Design Devel. 5, 322–329 (1966).

Schrock, V. E. & Grossman, L. M. Forced convection boiling in tubes. NSE. 12, 474–481. https://doi.org/10.13182/NSE62-A26094 (1962).

Dengler, C. E. & Addoms, J. N. Heat transfer mechanism for vaporization of water in a vertical tube. Chem. Eng. Prog. Symp. Ser. 52, 95–103 (1956).

Hadamard, J. Sur les problèmes aux dérivées partielles et leur signification physique. Princeton Univ. Bull. 49–52 (1902).

Maciąg, A. & Walaszczyk, M. The usage of the Trefftz method to determine the Biot number. J. Appl. Math. Comput. Mech. 16, 47–55. https://doi.org/10.17512/jamcm.2017.4.05 (2017).

Movahedian, B., Boroomand, B. & Soghrati, S. A Trefftz method in space and time using exponential basis functions: application to direct and inverse heat conduction problems. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 37, 868–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enganabound.2013.03.001 (2013).

Piasecka, M., Hożejowska, S. & Poniewski, M. E. Experimental evaluation of flow boiling incipience of subcooled fluid in a narrow channel. Int. J. Heat. Fluid Flow. 25, 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatfluidflow.2003.11.017 (2004).

Hożejowska, S., Piasecka, M. & Poniewski, M. E. Boiling heat transfer in vertical minichannels. Liquid crystal experiments and numerical investigations. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 48, 1049–1059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2008.11.013 (2009).

Hożejowska, S., Hożejowski, L. & Piasecka, M. Radial basis functions in mathematical modelling of flow boiling in minichannels. In EPJ Web of Conferences (2017). https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/201714302037

Hożejowska, S. & Piasecka, M. The application of Fourier transform to the identification of temperature distribution in HFE-7100 flow boiling in an annular minigap. in MATEC Web of Conferences (2018). https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201824001012

Maciejewska, B., Hożejowska, S., Grabowski, M. & Poniewski, M. E. Numerical analysis of the boiling heat transfer coefficient in the flow in mini-channels. AMA 17, 595–604. https://doi.org/10.2478/ama-2023-0069 (2023).

Hożejowski, L. & Hożejowska, S. Trefftz method in an inverse problem of two-phase flow boiling in a minichannel. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 98, 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enganabound.2018.10.001 (2019).

Piasecka, M., Hożejowska, S., Maciejewska, B. & Pawińska, A. Time-dependent heat transfer calculations with trefftz and picard methods for flow boiling in a mini-channel heat sink. Energies (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/en14071832 (2021).

Kołodziej, J. A. & Grabski, J. K. Many names of the Trefftz method. Eng. Anal. Bound. Elem. 96, 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enganabound.2018.08.013 (2018).

Kołodziej, J. A. & Zieliński, A. P. Boundary Collocation Techniques and their Application in Engineering (WIT, 2009).

Li, Z. C., Lu, T. T., Huang, H. Y. & Cheng, A. H.-D. The Trefftz and collocation methods. In Numerical Methods for Partial Differential Equations (WIT, 2008).

Qin, Q. H. The Trefftz Finite and Boundary Element Method (WIT, 2000).

Gardenghi, Á. R. et al. Overview of void fraction measurement techniques, databases and correlations for two-phase flow in small diameter channels. Fluids https://doi.org/10.3390/fluids5040216 (2020).

Qian, H. & Hrnjak, P. Design and calibration of capacitive sensors for measuring void fraction in vertical headers of microchannel heat exchangers. Int. J. Refrig. 129, 224–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2021.05.012 (2021).

De Kerpel, K., Ameel, B., T’Joen, C., Canière, H. & De Paepe, M. Flow regime based calibration of a capacitive void fraction sensor for small diameter tubes. Int. J. Refrig. 36, 390–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrefrig.2012.10.010 (2013).

De Kerpel, K. et al. Calibration of a capacitive void fraction sensor for small diameter tubes based on capacitive signal features. Appl. Therm. Eng. 63, 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2013.11.006 (2014).

Alssayh, M., Addali, A., Mba, D. & Dao, T. Identification of two phase flow regime using acoustic emission technology. Int. J. Mech. Prod. Eng. 1, 27–31 (2013).

Cavaro, M. A void fraction characterisation by low frequency acoustic velocity measurements in microbubble clouds. Phys. Procedia 70, 496–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phpro.2015.08.294 (2015).

Ide, H., Kimura, R. & Kawaji, M. Optical measurement of void fraction and bubble size distributions in a microchannel. Heat. Transf. Eng. 28, 713–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/01457630701328031 (2007).

Górski, G., Litak, G., Mosdorf, R. & Rysak, A. Dynamics of a two-phase flow through a minichannel: Transition from churn to slug flow. Eur. Phys. J. Plus https://doi.org/10.1140/epjp/i2016-16111-x (2016).

Widyatama, A., Dinaryanto, O., Deendarlianto & Indarto & The development of image processing technique to study the interfacial behavior of air-water slug two-phase flow in horizontal pipes. Flow. Meas. Instrum. 59, 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flowmeasinst.2017.12.015 (2018).

Płaczkowski, K., Grabowski, M. & Poniewski, M. E. Novel twofold use of photographic technique for simultaneous flow boiling image recording and void fraction computation in a mini-channel experiment. Energies (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/en14154478 (2021).

Trefftz, E. Ein gegenstuck zum ritzschen verfahren. In Proc. 2nd Int. Cong. Appl. Mech. 131–137 (Zurich, 1926).

Grabowski, M., Hożejowska, S., Pawińska, A., Poniewski, M. E. & Wernik, J. Heat transfer coefficient identification in mini-channel flow boiling with the hybrid Picard-Trefftz method. Energies (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/en11082057 (2018).

Grysa, K., Maciag, A. & Pawinska, A. Solving nonlinear direct and inverse problems of stationary heat transfer by using Trefftz functions. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 55, 7336–7340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2012.07.072 (2012).

Hożejowska, S., Kaniowski, R. & Poniewski, M. E. Experimental investigations and numerical modeling of 2D temperature fields in flow boiling in minichannels. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 78, 18–29 (2016).

Maciejewska, B., Strak, K. & Piasecka, M. The solution of a Two-dimensional inverse heat transfer problem using the Trefftz method. Procedia Eng. 157, 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2016.08.341 (2016).

Hożejowska, S., Grabowski, M. & Poniewski, M. E. Implementation of a three-dimensional model for the identification of flow boiling heat transfer coefficient in rectangular mini-channel. In Proc. EFM (eds. Dančová, P., Novosád, P. & Pulec, J.) 178–182 (Franzensbad, Czech Republic, 2019).

Hożejowska, S., Kaniowski, R. & Poniewski, M. E. Application of adjustment calculus to the Trefftz method for calculating temperature field of the boiling liquid flowing in a minichannel. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat. Fluid Flow. 24, 811–824. https://doi.org/10.1108/HFF-01-2013-0022 (2013).

Grabowski, M., Hożejowska, S., Maciejewska, B., Płaczkowski, K. & Poniewski, M. E. Application of the 2-D trefftz method for identification of flow boiling heat transfer coefficient in a rectangular minichannel. Energies (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/en13153973 (2020).

Brutin, D., Topin, F. & Tadrist, L. Experimental study of unsteady convective boiling in heated minichannels. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 46, 2957–2965 (2003).

Özdemir, M. R., Mahmoud, M. M. & Karayiannis, T. G. Flow boiling of water in a rectangular metallic microchannel. Heat. Transf. Eng. 42, 492–516 (2021).

Wang, D., Wang, D., Hong, F., Xu, J. & Zhang, C. Experimental study on flow boiling characteristics of R-1233zd(E) of counter-flow interconnected minichannel heat sink. Int J. Heat. Mass. Transf 215 (2023).

Sobierska, E., Kulenovic, R., Mertz, R. & Groll, M. Experimental results of flow boiling of water in a vertical microchannel. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 31, 111–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2006.03.022 (2006).

Płaczkowski, K., Poniewski, M. E., Grabowski, M. & Alabrudziński, S. Photographic technique application to the determination of void fraction in Two-Phase flow boiling in mini channels. AMA 797, 299–306. https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMM.797.299 (2015).

Lockhart, R. W. & Martinelli, R. C. Proposed correlation of data for isothermal two-phase two-component flow in pipes. Chem. Eng. Prog. 45, 39–48 (1949).

Piasecka, M. Heat transfer mechanism, pressure drop and flow patterns during FC-72 flow boiling in horizontal and vertical minichannels with enhanced walls. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 66, 472–488 (2013).

Shah, R. K. & London, A. L. Laminar Flow Forced Convection in Ducts: A Source Book for Compact Heat Exchanger Analytical Data (Academic, 1978).

Mikielewicz, J. Semi-empirical method of determining the heat-transfer coefficient for subcooled, saturated boiling in a channel. Int. J. Heat. Mass. Transf. 17, 1129–1134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0017-9310(74)90114-8 (1974).

Warrier, G. R., Dhir, V. K. & Momoda, L. A. Heat transfer and pressure drop in narrow rectangular channels. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 26, 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0894-1777(02)00107-3 (2002).

Kreith, F. The CRC Handbook of Mechanical Engineering (CRC Press, Inc., 1998).

Funding

The research was funded by the Warsaw University of Technology, Plock Campus, grant no. 504/04480/7193/44.000000.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H., M.E.P. M.G, methodology, M.G, S.H., A.P., validation, S.H., A.P., formal analysis A.P., S.H., investigation, M.G., writing—original draft preparation, M.G., S.H., A.P., M.E.P., writing—review & editing, M.G., S.H., A.P., M.E.P., funding acquisition, M.G.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grabowski, M., Hożejowska, S., Pawińska, A. et al. 2D Trefftz method in identification of flow boiling heat transfer coefficient in horizontal minichannel. Sci Rep 16, 4547 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34627-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34627-7