Abstract

Tonsillectomy is among the most frequently performed surgical procedures in pediatric patients. The incidence of postoperative pain in children after tonsillectomy is high. Patient age and postoperative pain are significant factors that increase the incidence of emergence agitation in children. The study aims to evaluate the impact of spraying dexmedetomidine and lidocaine on the bilateral tonsillar fossa before tonsillectomy on postoperative pain and agitation in children. A total of 140 children aged 4–12 years, who underwent elective tonsillectomy were randomly assigned to four groups: Group N received 5 ml of normal saline, Group L received 5 ml of 2%lidocaine(2 mg/kg) plus saline, Group D received 5 ml of 2 µg/kg dexmedetomidine plus saline, and Group LD received 5 ml of 2 µg/kg dexmedetomidine plus 2 mg/kg 2%lidocaine plus saline. These solutions were applied to the bilateral tonsillar fossa 3 min before surgical incision, following intubation and under general anesthesia. Heart rate and mean arterial pressure were monitored at six time points: upon entering the room(T0),start of operation(T1),end of operation(T2),5 min after extubation (T3),10 min after extubation (T4),and 20 min after extubation (T5).Restlessness was assessed using the Pediatric Anesthesia Emergence Delirium scale at T3, T4, and T5.Postoperative pain was evaluated with the FLACC(Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability) scale at T3, T4, T5, one hour (T6), and six hours (T7) post-extubation. Anesthetic drug dosage, extubation time, sinus bradycardia, respiratory adverse events, nausea, vomiting, and reoperation for hemostasis within 24 h were documented. Dexmedetomidine groups (D and LD) exhibited reduced agitation and pain compared to non-dexmedetomidine groups (N and L) (P < 0.05), and required less anesthesia during surgery (P < 0.05). Lidocaine did not alleviate postoperative pain or agitation (P > 0.05). Dexmedetomidine slightly decreased heart rate and mean arterial pressure (P < 0.05), but without clinical significance. No differences were observed in operation duration, PACU stay, postoperative nausea/vomiting, or respiratory events among all groups (P > 0.05). In summary, preoperative tonsillar spraying of dexmedetomidine contributes to reduced emergence agitation and postoperative pain in pediatric patients undergoing tonsillectomy.But spraying lidocaine doesn’t help with that.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tonsillectomy is among the most frequently performed surgical procedures in pediatric patients. The high incidence of postoperative pain in children is attributed to surgical stimulation of the terminal oropharyngeal nerves, ongoing inflammation following the procedure, and oropharyngeal muscle spasms1. Over 60% of children report moderate to severe pain post-surgery2. Pain can induce systemic changes in the cardiovascular, neuroendocrine, immune, and metabolic systems3.

Emergence agitation refers to a state of inconsistency between behavior and consciousness that occurs during the recovery period from general anesthesia, characterized by unconscious movements, incoherent speech, irrational speech, crying or moaning, and delusional thinking. Patient age and postoperative pain are significant factors that increase the incidence of emergence agitation in children, and compared to adult patients, children are more prone to emergence agitation.4,5

Dexmedetomidine is a drug that helps children relax and feel less pain during surgery without affecting their breathing6. It’s good for easing pain after tonsillectomy6. To avoid slow waking up, the IV drip needs to be stopped 30 min before the end of surgery. A high dose can affect blood pressure and heart rate7. Traditional administration of dexmedetomidine typically involves intravenous or intramuscular injection. While these methods are rapid in onset, they are invasive and may cause pain and discomfort to patients, particularly in pediatric populations, where acceptance is relatively low. In contrast, buccal mucosa administration offers a noninvasive alternative. Patients are required merely to hold the medication in the buccal area, eliminating the need for injection and thus improving patient compliance. In addition, intranasal or transmucosal administration of dexmedetomidine has been shown to avoid first-pass metabolism and enhance bioavailability, offering a noninvasive and well-tolerated alternative to intravenous routes8,9. A mouth spray version is easier to use, has fewer side effects, and helps pediatric patients recover faster10,11. In addition, it also reduces pain by stopping pain signals from the body12,13.

Lidocaine, a local anesthetic, is effective for surface anesthesia, with research14,15showing that it can significantly reduce pain in children after tonsillectomy when applied to the tonsillar fossa. The pairing of dexmedetomidine with lidocaine offers unique benefits in local anesthesia.16,17.

The objective of this study is to assess the effects of preoperative bilateral tonsillar fossa application of dexmedetomidine and lidocaine on postoperative pain and agitation in children following tonsillectomy. The goal is to inform anesthetic strategies for pediatric tonsillectomy, enhance patient comfort during the procedure.

Materials and methods

Clinical trial oversight

We conducted this double-blind, randomized, parallel-group clinical trial at the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University, Jiangxi Province, China, from June 2023 to December 2023.The study protocol received ethical approval from the Clinical Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University (Approval (ethics number: No.LLSC-2023042601) and is registered with the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2300072611, registered on 19/06/2023).

Study participants

In this study, we selected children aged 4–12, both genders, with an ASA physical status classification of Class I, who were diagnosed with chronic tonsillitis and were scheduled for tonsillectomy along with adenoidectomy in the Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. The guardians of these children have provided informed consent. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Mental or cognitive abnormalities;(2) Known allergies to the study drugs;(3) Severe sinus bradycardia;(4) Children with severe preoperative agitation or anxiety;(5) Weight more than 95% or less than 5% of peers;(6) Children whose families refuse to participate in the clinical trial.

Randomization and blindness

Randomization Method: A statistician uninvolved in subject recruitment used SPSS 26.0 software to generate a random number table. Blinding Implementation as follows:(1) The statistician created a random sequence;(2) An anesthetic assistant compiled an allocation sequence based on this sequence, duplicated it four times, and placed each copy in sealed, opaque envelopes. These were then securely stored by the anesthetic assistant, anesthesiologist, statistician, and anesthetic nurse;(3) An anesthesiologist determined if patients fulfilled the inclusion criteria;(4) For eligible patients, the anesthetic assistant, using the random number table, assigned the patient to a group, prepared the experimental drugs independently, and handed them to the anesthesiologist for administration. An anesthetic nurse, blind to group assignments, collected the data. Unblinding occurred post-experiment unless emergencies necessitated earlier revelation. The initial unblinding disclosed patient group assignments without medication details, followed by statistical analysis before a second unblinding. In cases of severe adverse reactions requiring knowledge of medication specifics, breaking the blind was performed.

Study procedures

Children were randomly assigned to four groups in a 1:1:1:1 ratio: a normal saline group (N Group), a lidocaine group (L Group), a dexmedetomidine group (D Group), and a dexmedetomidine-lidocaine combination group (LD Group). The PAED emergence Delirium and FLACC behavioral pain assessment tool was utilized as the primary outcome measure. Based on preliminary experimental data, the mean and standard deviation of PAED and FLACC scores at various time points for the four groups were used to determine the sample size required to detect statistically significant differences. With a two-sided α of 0.05 and a power of 1—β, the maximum sample size per group was calculated to be 32 patients using PASS software 15. Accounting for a 10% study dropout rate, 35 patients per group are needed, totaling 140 patients.

Before anesthesia, venous access was established and electrocardiographic monitoring initiated. Vital signs including blood oxygen saturation (SpO2), noninvasive blood pressure, body temperature, and Narcotrend anesthesia depth were continuously monitored. All children received the following medications for anesthesia induction: 0.1 mg/kg dexamethasone sodium phosphate, 0.1 mg/kg penehyclidine hydrochloride, 2 mg/kg propofol emulsion, 4 μg/kg fentanyl citrate, and 0.2 mg/kg cisatracurium besylate.

After confirming successful intubation and starting mechanical ventilation, treatments were applied as follows: Group N received 5 ml of normal saline sprayed onto the tonsillar fossa. Group L received 5 ml of 2% lidocaine (2 mg/kg) in normal saline sprayed onto the tonsillar fossa. Group D received 5 ml of dexmedetomidine (2 μg/kg) in saline sprayed onto the tonsillar fossa. Group LD received 5 ml of a mixture containing both dexmedetomidine (2 μg/kg) and 2% lidocaine (2 mg/kg) in normal saline sprayed onto the tonsillar fossa.

For anesthesia maintenance, propofol was administered at a rate of 6–12 mg/kg/h, and remifentanil at 0.1–0.3 μg/kg/min, maintaining the Narcotrend index at 40–50. All children underwent bilateral tonsillectomy and adenoid ablation using low-temperature plasma under nasal endoscopy, performed by the same surgeon.

After surgery, children were moved to the PACU and given atropine and neostigmine to counteract any remaining muscle relaxant effects. The endotracheal tube was taken out once they were awake, breathing well (more than 14 breaths a minute and over 6 ml/kg per breath), and had an SpO2 of over 96% after clearing their airway. They were watched for 20 min, and if all was well, they went back to their ward. If their heart rate fell below 60 beats a minute, they got atropine right away.

Outcome variables

The primary outcome measure was to evaluate the impact of the treatments on The PAED and FLACC Score. The PAED scale measures how restless children are at 5, 10, and 20 min after their breathing tube is removed. The FLACC scale rates their pain at the same times, plus 1 h and 6 h later. Restlessness during recovery was assessed using the Pediatric Anesthesia Emergence Delirium (PAED) scale18. The PAED score is based on the evaluation of five aspects of the child’s behavior: eye contact with medical staff, purposeful behavior, awareness of surroundings, restlessness, and consolability. Each item is scored from 0 to 4, with a total score of 20. The higher the score, the more severe the condition. A PAED score of 12 or above indicates that the child has experienced emergence delirium. Postoperative pain was assessed using the face, legs, activity, cry and consolability behavioral pain assessment scale (FLACC)19. The FLACC score is based on the evaluation of Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, and Consolability. Each item is scored from 0 to 2, and the child’s pain score is the sum of the scores of the five items, with a maximum of 10 points. A score of 0 indicates relaxation, 1–3 points indicate mild discomfort, 4–6 points indicate moderate pain, and 7–10 points indicate severe pain.

Secondary outcomes included heart rate (HR) and mean arterial pressure (MAP) measured at the following time points: upon entering the room (T0), the start of surgery (T1), the end of surgery (T2), 5 min post-extubation (T3), 10 min post-extubation (T4), and 20 min post-extubation (T5). Additionally, secondary outcomes encompassed intraoperative anesthetic dosage, the duration of endotracheal intubation, the occurrence of perioperative sinus bradycardia and respiratory adverse events, and the incidence of nausea, vomiting, and the need for reoperation for hemostasis within 24 h after surgery.

Statistical methods

Data analysis was conducted with SPSS 26.0 software. Normally distributed quantitative data were reported as mean ± SD. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s correction was used to assess differences between groups. Non-normal quantitative data were depicted as median (M) and IQR, and the Kruskal–Wallis test was employed for group comparisons. Categorical data were presented as frequencies (n) and percentages (%), and the chi-square test was utilized for analysis. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Comparison of baseline data of four groups of children

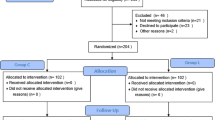

The baseline characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. This study enrolled a total of 140 children who were scheduled for tonsillectomy (Fig. 1). However, due to the temporary cancellation of surgery for upper respiratory tract infections and changes in surgical methods, only 134 children were ultimately included in the statistical analysis. The reasons for exclusion were as follows: two children in the normal saline group, one in the lidocaine group, and one in the dexmedetomidine combined with lidocaine group had their surgeries temporarily canceled. Additionally, one child in the lidocaine group and one in the dexmedetomidine group had a change in surgical procedure.

The gender distribution across the groups was not statistically different, as indicated by the chi-square test (P > 0.05). Age, height, and weight were reported as mean ± standard deviation, and no significant differences were found among the groups using one-way ANOVA (P > 0.05).

Comparison of PAED and FLACC scores among the four groups

The PAED and FLACC scores for the four groups are presented as median (interquartile range) in Table 2 and 3, respectively, and were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test.

At time points T3, T4, and T5, the PAED scores for Groups N (Saline) and L (Lidocaine) were significantly higher than those for Groups D (Dexmedetomidine) and LD (Combination), with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in PAED scores between Groups D and LD P > 0.05).

Similarly, at time points T3, T4, T5, T6, and T7, the FLACC scores for Groups N and L were significantly higher than those for Groups D and LD (P < 0.05), indicating more pain in the saline and lidocaine groups compared to the dexmedetomidine and combination groups. Again, there was no significant difference in FLACC scores between Groups D and LD (P > 0.05).

Comparison of heart rates (HR)and mean arterial pressure (MAP) of four groups of children at different times

Heart rate (HR) data for the four groups, expressed as mean ± standard deviation, are detailed in Table 4 and were analyzed using one-way ANOVA.

At T0, there were no significant differences in HR among the four groups (P > 0.05). At T1 and T2, Groups L (Lidocaine), D (Dexmedetomidine), and LD (Combination) had significantly lower HR compared to Group N (Saline) (P < 0.05), with no significant differences in HR observed between Groups L, D, and LD (P > 0.05). At T3, T4, and T5, Group L’s HR was lower than Group N’s, and both Groups D and LD had lower HR than Groups N and L, all with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). However, there was no significant difference in HR between Groups D and LD (P > 0.05).

MAP for the four groups, expressed as median (interquartile range), is presented in Table 5 and was analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test.

At T0, there were no significant differences in MAP among the four groups (P > 0.05). At T1, Groups D (Dexmedetomidine) and LD (Combination) had significantly lower MAP compared to Group N (Saline) (P < 0.05), with no significant differences observed among Groups L (Lidocaine), D, and LD (P > 0.05). At T2, the MAP did not significantly differ among the four groups (P > 0.05). At T3, T4, and T5, Groups D and LD had significantly lower MAP than Groups N and L (P < 0.05), with no significant difference between Groups D and LD (P > 0.05).

Comparison of operation duration, recovery duration and intraoperative consumption of propofol and remifentanil among the four groups

Operation duration, recovery duration, and intraoperative consumption of propofol and remifentanil for the four groups are shown in Table 6 as median (interquartile range) and were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test.

There were no significant differences in operation time and recovery time across the four groups (P > 0.05). However, Group D (Dexmedetomidine) and Group LD (Combination) had significantly lower intraoperative consumption of propofol and remifentanil compared to Group N (Saline) and Group L (Lidocaine), with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in intraoperative consumption of propofol and remifentanil between Group D and Group LD (P > 0.05).

Comparison of the incidence of various adverse reactions during perioperative anesthesia among the four groups

The incidences of various perioperative adverse reactions for the four groups are presented as n (%) in Table 7 and were analyzed using the chi-squared (χ2) test.

There were no significant differences in the incidence of adverse respiratory events, nausea and vomiting within 24 h post-operation, or the incidence of reoperation for hemostasis within 24 h post-operation among the four groups (P > 0.05). However, the incidence of sinus bradycardia during perioperative anesthesia was significantly higher in Groups D (Dexmedetomidine) and LD (Combination) compared to Groups N (Saline) and L (Lidocaine) (P < 0.05).

Discussion

The study found that preoperatively applying 2 μg/kg dexmedetomidine to the bilateral tonsillar fossa led to lower FLACC (pain) and PAED (agitation) scores postoperatively compared to using 2 mg/kg 2% lidocaine or normal saline. Moreover, combining dexmedetomidine with lidocaine did not result in better outcomes than dexmedetomidine alone. Significantly, no difference in FLACC and PAED scores was observed at various postoperative time points between the use of 2 mg/kg 2% lidocaine and normal saline in the bilateral tonsillar fossa.

The study enriches the limited literature on the use of dexmedetomidine in tonsil surface anesthesia. It demonstrates that dexmedetomidine, whether administered alone or in combination with lidocaine, significantly reduces postoperative PAED (Post-Anesthesia Emergence Delirium) and FLACC (Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability) scores compared to normal saline and lidocaine alone. This indicates that a 2 μg/kg dose of dexmedetomidine is effective in alleviating agitation and pain following tonsillectomy. However, the study’s limitation lies in the absence of a comparison with buccal administration alone, which prevents a definitive conclusion on whether the observed analgesic effects are predominantly due to the systemic absorption of buccally administered dexmedetomidine or its direct local analgesic action on the tonsil.

Previous studies have suggested that topical lidocaine application reduces post-tonsillectomy pain in children.1214 However, our results showed no significant difference in postoperative pain scores between the lidocaine and saline groups. Although the lidocaine group’s heart rate was lower than the saline group’s from T1 to T5, the lidocaine and saline groups didn’t differ much in how restless or in pain the children were after surgery. Here’s why: The lidocaine solution was diluted to a total volume of 5 mL, which may have reduced its local anesthetic efficacy; We didn’t put any medicine on the adenoids, so the lidocaine might not have helped much with the pain from that area; which is different from what other studies found.

Children with breathing problems are more likely to have trouble with their breathing during deep sedation. Dexmedetomidine is a good choice for pediatric patients because it reduces agitation without requiring additional respiratory support20. It also lowers the chance of breathing problems like wheezing and closing of the airway that can happen when a tube is put in or taken out20,21,22. In our study, the breathing problem rates in the groups given dexmedetomidine were 14.7% and 11.8%, which were lower than the 30.3% and 24.2% rates in the groups given normal saline and lidocaine, but the difference wasn’t big enough to be sure it was not by chance. No serious breathing problems happened in any group. Studies show dexmedetomidine can reduce irritation and swelling in the airway, which might make it less sensitive23,24. Another study11 found that giving dexmedetomidine through the nose could help with breathing problems in pediatric patients during tonsillectomy. But because we didn’t have many pediatric patients in our study, we can’t be sure if putting dexmedetomidine on the tonsil area is as good as putting it in the nose. We need more studies to be sure.

Dexmedetomidine significantly affects children’s heart rates and blood pressure22,24,25,26. Our study found higher rates of sinus bradycardia in children receiving dexmedetomidine, with or without lidocaine, compared to normal saline or lidocaine alone. This aligns with previous findings12,2622that dexmedetomidine can cause bradycardia and hypotension, which requires careful monitoring and management. Despite these effects, no severe cardiovascular events occurred in our study, and stable hemodynamics were maintained, reducing the risk of adverse outcomes.

The overall cardiovascular effects of dexmedetomidine are complex. At lower plasma concentrations, it induces modest reductions in heart rate and blood pressure. At higher concentrations, it may lead to bradycardia and hypertension7.Additionally, dexmedetomidine causes peripheral vasoconstriction through a direct action on vascular smooth muscle27. This mechanism may reduce postoperative bleeding, particularly in pediatric patients following tonsillectomies, where severe cases occasionally require additional surgical intervention to control hemorrhage. Dexmedetomidine may potentially decrease the need for such secondary procedures, thereby facilitating recovery28. However, in our study, only one child in the lidocaine group needed another surgery for bleeding within 24 h after the tonsillectomy. The use of low-temperature plasma technology has greatly reduced bleeding during surgery and the need for additional hemostasis in children, doing better than traditional methods29 Therefore, a large, multicenter, randomized trial is needed to see if dexmedetomidine can really decrease the risk of bleeding after tonsillectomies.

Dexmedetomidine and lidocaine have unique benefits when used together locally16,17. Studies have shown that dexmedetomidine can enhance the potency and duration of lidocaine’s local anesthetic effects. However, our study did not find significant improvements in postoperative pain and agitation scores with the combination compared to dexmedetomidine alone. This suggests that the benefits of lidocaine may be less pronounced when used with dexmedetomidine.

The experiment had several limitations. The study’s limitation lies in the absence of a comparison with buccal administration alone, which prevents a definitive conclusion on whether the observed analgesic effects are predominantly due to the systemic absorption of buccally administered dexmedetomidine or its direct local ana lgesic action on the tonsil. In addition, the intraoperative fentanyl dose (4 μg/kg) may be considered relatively high compared to some clinical practices, which could have influenced postoperative pain and agitation outcomes, potentially masking or augmenting the effects of dexmedetomidine and lidocaine. The concentration of lidocaine used was limited, and no comparisons were made between different concentrations; the experimental drug was not applied to the adenoid surface, which might have affected the results due to varying pain levels after adenoidectomy in different children; the postoperative follow-up period was brief, preventing an exploration of dexmedetomidine’s long-term analgesic effects, which may not have captured delayed emergence agitation or pain occurring after discharge from the PACU; not measuring blood drug concentrations at various times could introduce bias due to differences in drug absorption; and the noisy ward environment precluded an assessment of dexmedetomidine’s impact on children’s sleep quality during the first postoperative night. due to logistical constraints, we did not collect data on FLACC scores or rescue analgesia usage in the ward, limiting our ability to assess longer-term postoperative recovery. Future studies should consider extended monitoring periods and ward-based assessments to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of the interventions.

Conclusion

-

1.

Applying 2 μg/kg dexmedetomidine to the tonsillar fossa before surgery can decrease agitation after tonsillectomy, ease postoperative pain, and lower anesthesia requirements during the operation in children.

-

2.

Preoperative spraying of 2 mg/kg 2% lidocaine onto the tonsillar fossa does not significantly reduce emergence agitation or postoperative pain in children undergoing tonsillectomy.

In short, dexmedetomidine before surgery helps pediatric patients feel better after tonsillectomy, but lidocaine doesn’t seem to help.

Data availability

The data are available from the corresponding author after a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PACU:

-

Postanesthesia care unit

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- PAED:

-

Pediatric anesthesia emergence delirium

- FLACC:

-

The face, legs, activity, cry, consolability behavioral tool

References

Sampaio, A. L., Pinheiro, T. G., Furtado, P. L., Araújo, M. F. & Olivieira, C. A. Evaluation of early postoperative morbidity in pediatric tonsillectomy with the use of sucralfate. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 71(4), 645–651 (2007).

Stewart, D. W., Ragg, P. G., Sheppard, S. & Chalkiadis, G. A. The severity and duration of postoperative pain and analgesia requirements in children after tonsillectomy, orchidopexy, or inguinal hernia repair. Paediatr. Anaesth. 22(2), 136–143 (2012).

Loeser, J. D. & Melzack, R. Pain: An overview. The Lancet 353(9164), 1607–1609 (1999).

Dahmani, S., Delivet, H. & Hilly, J. Emergence delirium in children: An update. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 27(3), 309–315 (2014).

Lee, S. J. & Sung, T. Y. Emergence agitation: Current knowledge and unresolved questions. Korean J. Anesthesiol. 73(6), 471–485 (2020).

Cho, H. K., Yoon, H. Y., Jin, H. J. & Hwang, S. H. Efficacy of dexmedetomidine for perioperative morbidities in pediatric tonsillectomy: A metaanalysis. Laryngoscope 128(5), E184–E193 (2018).

Bloor, B. C., Ward, D. S., Belleville, J. P. & Maze, M. Effects of intravenous dexmedetomidine in humans. II. Hemodynamic changes. Anesthesiology 77(6), 1134–1142 (1992).

Shen, F. et al. Effect of intranasal dexmedetomidine or midazolam for premedication on the occurrence of respiratory adverse events in children undergoing tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw. Open 5(8), e2225473 (2022).

Anttila, M., Penttilä, J., Helminen, A., Vuorilehto, L. & Scheinin, H. Bioavailability of dexmedetomidine after extravascular doses in healthy subjects. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 56(6), 691–693 (2003).

Abdel-Ghaffar HS, Abdel-Wahab AH, Roushdy MM. Dexmedetomidina transmucosa oral para controle da agitação ao despertar em crianças submetidas a amigdalectomia: ensaio clínico randomizado [Oral trans-mucosal dexmedetomidine for controlling of emergence agitation in children undergoing tonsillectomy: a randomized controlled trial]. Braz J Anesthesiol. 69(5):469-476 (2019)

Shen, F. et al. Effect of intranasal dexmedetomidine or midazolam for premedication on the occurrence of respiratory adverse events in children undergoing tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 5(8), e2225473 (2022).

Chen, Z., Liu, Z., Feng, C., Jin, Y. & Zhao, X. Dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant in peripheral nerve block. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 17, 1463–1484 (2023).

Rwei, A. Y., Sherburne, R. T., Zurakowski, D., Wang, B. & Kohane, D. S. Prolonged duration local anesthesia using liposomal bupivacaine combined with liposomal dexamethasone and dexmedetomidine. Anesth. Analg. 126(4), 1170–1175 (2018).

Hosseini Jahromi, S. A., Hosseini Valami, S. M. & Hatamian, S. Comparison between effect of lidocaine, morphine and ketamine spray on post-tonsillectomy pain in children. Anesth. Pain Med. 2(1), 17–21 (2012).

Meechan, J. G. Intra-oral topical anaesthetics: A review. J. Dent. 28(1), 3–14 (2000).

Goudarzi, T. H., Kamali, A., Yazdi, B. & Broujerdi, G. N. Addition of dexmedetomidine, tramadol and neostigmine to lidocaine 1.5% increasing the duration of postoperative analgesia in the lower abdominal pain surgery among children: A double-blinded randomized clinical study. Med. Gas Res. 9(3), 110–114 (2019).

Lu, Y. et al. Perineural dexmedetomidine as an adjuvant reduces the median effective concentration of lidocaine for obturator nerve blocking: A double-blinded randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 11(6), e0158226 (2016).

Sikich, N. & Lerman, J. Development and psychometric evaluation of the pediatric anesthesia emergence delirium scale. Anesthesiology 100(5), 1138–1145 (2004).

Peng, T. et al. A systematic review of the measurement properties of face, legs, activity, cry and consolability scale for pediatric pain assessment. J. Pain Res. 16, 1185–1196 (2023).

Walker, T. & Kudchadkar, S. R. Pain and sedation management: 2018 update for the Rogers’ textbook of pediatric intensive care. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 20(1), 54–61 (2019).

Cruickshank, M. et al. Alpha-2 agonists for sedation of mechanically ventilated adults in intensive care units: A systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 20(25), v–117 (2016).

Simonini, A. et al. Dexmedetomidine reduced the severity of emergence delirium and respiratory complications, but increased intraoperative hypotension in children underwent tonsillectomy: A retrospective analysis. Minerva Pediatr. (Torino). 76(5), 574–581 (2024).

Mikami, M. et al. Dexmedetomidine’s inhibitory effects on acetylcholine release from cholinergic nerves in guinea pig trachea: A mechanism that accounts for its clinical benefit during airway irritation. BMC Anesthesiol. 17(1), 52 (2017).

Tang, C. et al. Intranasal dexmedetomidine on stress hormones, inflammatory markers, and postoperative analgesia after functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Mediators Inflamm. 2015, 939431 (2015).

Gong, M., Man, Y. & Fu, Q. Incidence of bradycardia in pediatric patients receiving dexmedetomidine anesthesia: A meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pharm. 39(1), 139–147 (2017).

Tobias, J. D. Dexmedetomidine: Applications in pediatric critical care and pediatric anesthesiology. Pediatr. Crit Care Med. 8(2), 115–131 (2007).

Tasbihgou, S. R., Barends, C. R. M. & Absalom, A. R. The role of dexmedetomidine in neurosurgery. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 35(2), 221–229 (2021).

Richa, F. & Yazigi, A. Effect of dexmedetomidine on blood pressure and bleeding in maxillo-facial surgery. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 24(11), 985–986 (2007).

Yi, X., Deng, T., Zhu, H. & Fu, Y. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi 36(10), 768–771 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University Department of Anesthesiology all personnel.

Funding

This article is supported by the following funds: Jiangxi Provincial Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 20232ACB206050) 、The Open Project of Key Laboratory of Prevention and Treatment of Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular Disease, Ministry of Education (Grant No. XN201917) and Science 、Technology Plan Guidance Tasks of Ganzhou City (Grant No. GZ2020ZSF079) and Commissioned Research Project Contract of Gannan Medical University (Grant No. HX202204).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L., L.H.B. and D.X.J.: conceived and designed the study. L.H.B. and Y.W.Y.: conducted the study. L.H.B., Z.T. and L.X.: analyzed the data. L.H.B. and Z.T.: prepared the first draft of the manuscript. L.H.B., L.X., L.Z.L., Z.T., Z.M.L. and L.W.D.: contributed to the major revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the final manuscript revisions and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The trial obtained approved by the ethics review committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Gannan Medical University (ethics number: LLSC-2023042601) and registered in the China clinical trial registry (ChiCTR2300072611). The study was conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki for medical research involving human subjects.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, HB., Zheng, T., Zhong, ML. et al. Dexmedetomidine with lidocaine topical anesthesia reduces emergence agitation and postoperative pain after pediatric tonsillectomy. Sci Rep 16, 4871 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34802-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34802-w