Abstract

Recently, deep-learning-based approaches have been widely applied in sEMG-based gesture recognition. While some existing methods have explored the integration of time-domain and frequency-domain features, many still face challenges in comprehensively leveraging the complementary information from both domains, often due to limitations in capturing multi-scale temporal dependencies or sub-optimal fusion strategies. To address these persistent limitations and further enhance accuracy and robustness, we propose the Multi-Scale Dual-Stream Fusion Network (MSDS-FusionNet), a novel deep learning framework that integrates temporal and frequency-domain features for enhanced gesture classification accuracy. MSDS-FusionNet introduces two key innovations: the Multi-Scale Mamba (MSM) modules, which extract multi-scale temporal features through parallel convolutions with varying kernel sizes and linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces, enabling the capture of temporal patterns at multiple scales and the modeling of both short-term and long-term dependencies; and the Bi-directional Attention Fusion Module (BAFM), which effectively combines temporal and frequency-domain features using bi-directional attention mechanisms to fuse complementary information and improve recognition accuracy dynamically. Extensive experiments on the NinaPro dataset demonstrate that MSDS-FusionNet outperforms state-of-the-art methods, achieving accuracy improvements of up to 2.41%, 2.46%, and 1.38% on the DB2, DB3, and DB4 datasets, respectively, with final accuracies of 90.15%, 72.32%, and 87.10%. This study presents a robust and flexible solution for sEMG-based gesture recognition, effectively addressing the complexities of recognizing intricate gestures and offering significant potential for applications in prosthetics, virtual reality, and assistive technologies. The code of this study is available at https://github.com/hdy6438/MSDS-FusionNet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although surface electromyography (sEMG) signals have been widely adopted in human-machine interface (HMI) systems for gesture recognition, existing algorithms still exhibit notable limitations that hinder their performance. Early approaches frequently rely on handcrafted features, linear models, or subject-specific calibration, which can fail to capture the complex neuromuscular characteristics inherent in sEMG signals1,2,3,4. While these methods show certain efficacy, they tend to overlook subtle sEMG variations and noise interference, thus restricting their generalization and robustness when confronted with diverse user populations and dynamic usage conditions5,6,7. Furthermore, the inherent instability of sEMG signals, which are highly susceptible to interference from factors like sweat, muscle fatigue, and electrode displacement, poses a significant challenge for reliable, real-world applications8,9. Consequently, advanced learning-based strategies are required to better exploit the latent information in sEMG signals and improve classification accuracy10,11,12,13.

In recent years, deep learning has emerged as a powerful means of learning compact and high-level representations directly from raw sEMG data14,15. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) effectively capture local spatial features and hierarchical structures, facilitating the detection of salient signal components in multiple scales16,17,18. Meanwhile, recurrent neural networks (RNNs), especially variants like long short-term memory (LSTM), excel at modeling temporal dependencies by preserving past information over extended sequences19,20,21. Hybrid models that integrate CNNs and RNNs have further advanced the field by jointly capturing spatial and temporal characteristics, thereby improving recognition robustness22,23,24,25.

While significant strides have been made in deep learning for sEMG classification, many existing deep networks still primarily emphasize time-domain patterns or integrate frequency cues in a partial or sub-optimal manner26,27,28. This often leads to difficulties in comprehensively representing the full spectrum of sEMG signals, due to architectural limitations in capturing multi-scale dynamics or sub-optimal fusion strategies. This limitation is particularly pronounced in complex gesture recognition tasks, where both temporal and frequency-domain features are crucial for accurately capturing the intricate dynamics of muscle activity23,24. Consequently, despite these advancements, comprehensively integrating and leveraging the physiologically significant frequency-domain features remains a challenge for many deep learning methods. Specifically, higher frequencies in sEMG signals often correlate with fine motor control and rapid muscle responses, whereas lower frequencies are more indicative of sustained muscle contractions29,30,31. Moreover, frequency-domain analysis provides critical insights into muscle fatigue, contraction intensity, and muscle fiber recruitment patterns32,33,34,35. However, many state-of-the-art architectures-particularly those originally designed to emphasize time-domain structure-cannot fully encapsulate this frequency information, largely due to inherent limitations in their model design and feature-extraction pipelines36,37,38.

To address the limitations of existing approaches, we propose a novel Multi-Scale Dual-Stream Fusion Network (MSDS-FusionNet) for high-accuracy surface sEMG-based gesture classification. The MSDS-FusionNet leverages a dual-stream architecture that processes sEMG signals through two primary branches: the Temporal Branch and the Frequency Branch. The Temporal Branch extracts multi-scale temporal features by employing multiple Multi-Scale Mamba (MSM) modules, which utilize parallel convolutions with varying kernel sizes to capture temporal patterns across different scales. These features are subsequently refined via Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces (Mamba)39, facilitating efficient sequence modeling across diverse temporal resolutions and enhancing the network’s capacity to capture intricate temporal dynamics in sEMG signals. In parallel, the Frequency Branch is designed to extract frequency-domain features by combining convolutional layers with recurrent units, enabling the model to capture the dynamic muscle activity patterns embedded in the frequency spectrum of sEMG signals. The temporal and frequency-domain features from both branches are then integrated through the proposed Bi-directional Attention Fusion Module (BAFM), which effectively fuses complementary information to generate the final gesture classification output. This fusion strategy allows MSDS-FusionNet to leverage both temporal and frequency-domain insights, enabling the model to simultaneously capture critical dynamic patterns in the time domain and important frequency components in the frequency domain. By focusing on both domains, BAFM enhances the model’s ability to recognize complex gestures with improved accuracy and robustness. The bidirectional attention mechanism not only integrates complementary information but also improves the model’s stability by overcoming the limitations of relying on a single domain’s features. As a result, MSDS-FusionNet achieves superior performance in gesture recognition tasks, benefiting from the comprehensive and flexible fusion of temporal and frequency-domain features.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

-

We propose a novel Multi-Scale Dual-Stream Fusion Network (MSDS-FusionNet) for high-accuracy sEMG-based gesture classification. This network leverages a dual-stream architecture to capture both multi-scale temporal and frequency-domain features, providing a comprehensive representation of sEMG signals.

-

We introduce the Multi-Scale Mamba (MSM) modules, which are designed to extract features at different temporal resolutions. These modules enable the network to capture both short-term and long-term dependencies in the sEMG signals, enhancing the model’s ability to recognize complex gestures.

-

We develop the Bi-directional Attention Fusion Module (BAFM), which effectively fuses the features extracted from the temporal and frequency branches. This module leverages bi-directional attention mechanisms to integrate complementary information across different modalities, improving the overall classification performance.

-

We conduct extensive experiments on the NinaPro dataset, demonstrating that the MSDS-FusionNet outperforms state-of-the-art methods in terms of accuracy, precision, and recall. Specifically, our model achieves an accuracy of 90.15% on the NinaPro DB2 dataset, 72.32% on the NinaPro DB3 dataset, and 87.10% on the NinaPro DB4 dataset, which represents an accuracy improvement of up to 2.41%, 2.46%, and 1.38% on the NinaPro DB2, DB3, and DB4 datasets, respectively, compared to existing state-of-the-art methods.

Related work

Temporal-domain methods have been foundational in analyzing sEMG signals for gesture recognition, primarily focusing on the sequential dynamics of muscle activity. For instance, Khushaba et al. (2021) proposed a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network for myoelectric pattern recognition, which emphasized temporal features for modeling sequential muscle contractions19. While these methods effectively capture temporal patterns and work well for many tasks, they are inherently limited in fully leveraging the rich complementary information present in the frequency domain, which is crucial for capturing the full complexity and nuance of sEMG signals. Sun et al. (2021) also employed an LSTM network to decode sEMG signals and predict motor intentions in neuro-robotics21. Their approach, typical of models primarily focused on the temporal domain, does not explicitly integrate frequency-domain features, indicating a gap in fully capitalizing on multi-domain insights for enhanced performance in dynamic or nuanced gestures.

Frequency-domain methods have gained prominence in sEMG gesture recognition due to their ability to capture the spectral content of muscle activity. These features are especially crucial in analyzing rapid muscle contractions and subtle differences between gestures that may not be visible in the time domain. The significance of frequency-domain features has been well established in recent research, where they are shown to complement time-domain features by providing insights into muscle fatigue, contraction intensity, and fiber recruitment patterns. Indeed, recognizing the complementary nature of these domains, some studies have begun to explore their joint utilization. For example, Zhang et al. (2022) highlighted the importance of combining both temporal and frequency-domain features for sEMG-based gesture recognition. Their dual-view deep learning approach demonstrated that integrating frequency-domain features leads to improved classification accuracy, as these features capture distinct aspects of muscle activity that time-domain methods may miss26.

Dual-stream fusion networks have indeed emerged as a prominent approach for combining time-domain and frequency-domain features, leveraging the strengths of both domains to achieve enhanced performance in gesture recognition, particularly for complex and dynamic movements. Kim et al. (2021) explored the combination of CNN and LSTM networks to process both time-domain and frequency-domain features for gesture classification20. This dual-domain integration allowed the model to better capture both the dynamic and spectral characteristics of muscle activity. Peng et al. (2022) introduced the MSFF-Net24, which processes time-domain and frequency-domain features separately before fusion, enhancing robustness by addressing issues like muscle fatigue. Similarly, Zabihi et al. (2023) presented a transformer-based model that integrates time-domain and frequency-domain features in a dual-stream framework23, achieving higher recognition accuracy. Zhang et al. (2022) also demonstrated the effectiveness of dual-stream networks, integrating both temporal and frequency-domain features into their deep learning model26. While these dual-stream methods represent a significant advancement, many still face challenges in comprehensively capturing multi-scale temporal dependencies and effectively fusing highly complementary information from both domains. This often stems from sub-optimal designs in their feature extraction pipelines or fusion mechanisms, which may not fully exploit the nuanced interplay between temporal dynamics and frequency characteristics across different scales, limiting overall accuracy and robustness for increasingly complex gesture recognition tasks. Thus, there remains a critical need for more sophisticated architectures capable of fine-grained multi-scale temporal modeling and adaptive, bidirectional fusion of time and frequency information.

Data and preprocessing

Datasets

The NinaPro dataset, one of the largest publicly available sEMG databases, which can be downloaded at https://ninapro.hevs.ch, is extensively utilized for evaluating various HMI-based methods; it comprises ten sub-datasets labeled from DB1 to DB101,2. In this study, we utilized three sub-datasets from this database, DB2, DB3, and DB4, to comprehensively validate the effectiveness of the proposed MSDS-FusionNet. Specifically, DB2 contains 12-channel upper limb sEMG data collected from 40 healthy subjects performing 49 hand movements, along with a rest position, sampled at a frequency of 2000 Hz. The 12 sEMG channels correspond to specific electrode placements: columns 1-8 are electrodes equally spaced around the forearm at the height of the radio humeral joint; columns 9 and 10 capture signals from the main activity spots of the flexor and extensor digitorum superficialis muscles; and columns 11 and 12 record signals from the main activity spots of the biceps brachii and triceps brachii muscles 1,2. The 49 hand gestures encompass 12 fundamental finger movements (exercise A), 8 finger and 9 wrist movements (exercise B), 23 grasping and functional movements (exercise C), and 9 force patterns (exercise D). The NinaPro DB3 dataset contains sEMG data from 11 transradial amputees, and NinaPro DB4 comprises data from 10 non-amputee individuals. Table 1 provides further details about the three sub-datasets employed in this research, with the Fig. 1 visualizes the gesture classes in the NinaPro dataset.

Signal preprocessing

Denoising the raw data

A band-pass filter with a frequency range of 10–500 Hz, capturing the primary components of sEMG signals5, is first applied to remove low- and high-frequency noise. Then, a 50 Hz notch filter is utilized to eliminate power line interference, a frequent issue in signal acquisition6. Finally, a wavelet filter with Symlet mother wavelets, order 8, and a decomposition level of 15 is applied. Recent studies demonstrate that the wavelet transform effectively isolates and removes persistent noise components7,40. This denoising approach significantly enhances signal-to-noise ratios in various biomedical applications, including sEMG41,42.

Dataset division and normalizing

In this study, we employed a subject-dependent division strategy to train and validate our model using each subject’s sEMG data individually3,4. For each subject, the data were divided by using the 1st, 3rd, 4th, and 6th repetitions of each gesture for training, while the 2nd and 5th repetitions were reserved for validation43. This approach allowed the model to learn from a diverse set of gesture examples while being tested on different, unseen repetitions to ensure a fair evaluation. Training and validating separately for each subject helps the model to adapt to each individual’s specific sEMG patterns without interference from other subjects. We also excluded rest state data to avoid class imbalance, which enabled the model to focus more effectively on distinguishing between active gestures44. This approach provides us with an accuracy metric for each subject, which we then averaged to evaluate the overall performance across the dataset4.

To ensure a consistent probability distribution across both the training and test sets, we apply \(\mu\)-law normalization and Max normalization, as defined in Equations 1 and 2, respectively.

where the input is represented by \(x\), and the new range of the signal is indicated by parameter \(\mu\), which is set to 2048 in this study.

where \(x_{\text {max}}\) is maximum amplitude of the input signals.

This normalization step effectively standardizes the data, addressing dimensional variations among the channels of sEMG data, and contributes to more stable network convergence during training.

Data augmentation

To enhance model robustness and avoid overfitting, we employ data augmentation techniques tailored to reflect realistic sEMG signal variability.

First, a sliding window segmentation with overlapping is applied, using 200 ms windows with a 5 ms overlap. This approach captures the temporal dynamics of sEMG signals while maintaining a high temporal resolution, allowing the model to learn from both local and global patterns45,46. The 200 ms window length is chosen based on empirical studies indicating that it balances the need for capturing sufficient temporal context while ensuring manageable computational complexity27,45. The 5 ms overlap ensures that adjacent windows share information, preventing abrupt transitions and preserving continuity in the data.

To further diversify temporal characteristics, each window has a 50% probability of undergoing time-scale modification, where time is scaled by random factors sampled uniformly from the range \([0.8, 1.2]\). This simulates natural variations in muscle contraction speeds, accounting for factors like fatigue or differences in user movement patterns, and strengthens model generalization across various temporal dynamics47.

We also incorporated frequency-domain augmentation, where each (original or time-scaled) signal has a 50% probability of being transformed via FFT and injected with Gaussian noise \(N(0, 0.5^2)\) across the frequency spectrum. This approach mimics real-world noise sources such as electrical interference and sensor movement, providing resilience against environmental noise45. Finally, an inverse FFT (iFFT) is applied to convert the augmented signals back to the time domain, preserving their original structural integrity while adding realistic variations. These combined methods effectively increase dataset size and variability, enabling the model to better handle amplitude, frequency, and temporal variations commonly encountered in practical sEMG applications.

Model architecture

The proposed MSDS-FusionNet, illustrated in Fig. 2, is designed to process sEMG signals by extracting and fusing features across multiple temporal scales and frequency domains. The network comprises two primary branches: the Temporal Branch and the Frequency Branch. The Temporal Branch is designed to capture multi-scale temporal features, while the Frequency Branch focuses on extracting frequency-domain features. These features are then fused to generate final classification output using the proposed Bi-directional Attention Fusion Module (BAFM), and the entire network is trained with deep supervision strategies to ensure robust feature learning48.

Overall architecture

The input to MSDS-FusionNet is a sEMG signal matrix of size \(400 \times 12\), where 400 denotes the number of time steps and 12 represents the number of sensing channels. The architecture processes this input through separate temporal and frequency branches before fusing the extracted features.

Temporal branch

The Temporal Branch begins by spliting the 12 input channels into two subsets, each containing 6 channels. Each subset undergoes an initial projection through a \(1 \times 1\) convolutional layer, expanding the channel dimension from 6 to 64, yielding projected feature maps \(\varvec{X}_{\text {proj}} \in \mathbb {R}^{400 \times 64}\), which are crucial for effectively mapping the input signals into a high-dimensional feature space, enabling the network to capture more complex temporal patterns.

Subsequently, each projected feature map is sequentially processed through three proposed Multi-Scale Mamba (MSM) modules, which are designed to extract temporal features at different scales, while internal MaxPooling operations progressively reduce the temporal dimension:

Each MSM module reduces the temporal length by a factor of 2, maintaining the channel dimension at 64. At each scale, corresponding feature maps from the two subsets are fused using the BAFM, resulting in refined and downsampled fused feature maps \(\varvec{F}_{\text {fused}}^{(s)} \in \mathbb {R}^{64 \times 64}\) for each scale \(s \in \{1, 2, 3\}\), rwhich are then concatenated along the channel dimension:

To ensure stability in the feature distributions, Batch Normalization is applied to the concatenated features \(\varvec{F}_{\text {concat}}\), resulting in \(\varvec{F}_{\text {bn}}\), which are then processed by an additional MSM module to further extract and fuse multi-scale features, reducing the temporal length to 32:

Finally, a \(1 \times 1\) convolutional layer is applied to project the channels from 192 back to 64, generating the ultimate temporal branch feature representation \(\varvec{F}_{\text {temp}} \in \mathbb {R}^{32 \times 64}\) , consolidating the rich multi-scale information extracted by the MSM modules into a compact and refined output for the temporal stream.

Frequency branch

The Frequency Branch captures the frequency-domain characteristics of sEMG signals, complementing the temporal features extracted by the Temporal Branch. It first applies a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to convert the input sEMG signals from the time to the frequency domain, decomposing them into constituent frequency components that reveal muscle activation patterns. The real part of the FFT output is extracted to form the frequency-domain representation \(\varvec{X}_{\text {fft\_real}} \in \mathbb {R}^{400 \times 12}\). A subsequent \(1 \times 1\) convolution projects the channels from 12 to 64, yielding the projected frequency-domain feature map \(\varvec{X}_{\text {proj\_freq}} \in \mathbb {R}^{400 \times 64}\), which expands the feature space to capture more complex frequency patterns.

The projected frequency-domain feature map is then processed through a linear layer to further refine the representation, resulting in \(\varvec{X}_{\text {linear\_freq}} \in \mathbb {R}^{400 \times 64}\). This linear transformation enhances the feature representation by allowing the model to learn a more compact and discriminative frequency-domain feature space. To capture the temporal dependencies within the frequency domain, a Bi-directional Gated Recurrent Unit (BiGRU)49 is applied to the linearized frequency-domain features:

The BiGRU layers enable the network to learn dependencies in both forward and backward directions, thereby enriching the frequency-domain feature representation with contextual information. Subsequently, another linear layer reduces the channel dimension from 128 back to 64, resulting in the final frequency-domain feature map \(\varvec{F}_{\text {freq}} \in \mathbb {R}^{400 \times 64}\). This final representation captures the essential frequency-domain characteristics of the sEMG signals, which are crucial for recognizing complex gestures. Finally, downsampling operation is performed to reduce the feature length from 400 to 32, resulting in a final frequency-domain feature map \(\varvec{F}_{\text {freq}} \in \mathbb {R}^{32 \times 64}\).

Feature fusion

The features extracted from the Temporal Branch and Frequency Branch, denoted as \(\varvec{F}_{\text {temp}}\) and \(\varvec{F}_{\text {freq}}\), respectively, are subsequently fused using the BAFM. This fusion mechanism effectively combines the complementary information from both branches, while reducing the feature length from 32 to 1 through internal MaxPooling, resulting in a fused feature vector:

The fused feature representation \(\varvec{F}_{\text {fusion}}\) is then passed through a linear classification layer to produce the final prediction \(\hat{y}_{\text {fusion}} \in \mathbb {R}^{49}\), which is a vector of probabilities corresponding to the 49 gesture classes.

Deep supervision

To improve training stability and enhance the learning of multimodal features, deep supervision is incorporated into the MSDS-FusionNet architecture. This approach is applied to the classification outputs from the Temporal, Frequency, and Fused branches, providing additional supervisory signals during training.

Each branch includes an auxiliary linear classification layer, which is only active during training to facilitate learning of intermediate representations. These layers are defined as:

where \(\varvec{F}_{\text {temp}}\) and \(\varvec{F}_{\text {freq}}\) represent the feature representations from the Temporal and Frequency branches, respectively. These linear layers are employed to generate auxiliary classification outputs during training, providing additional feedback to the network.

To address the class imbalance and focus the learning on hard-to-classify examples, we utilize focal loss50, which is defined as:

where \(\hat{y}_y\) is the predicted probability for the true class y, and \(\alpha\) and \(\gamma\) are hyperparameters controlling the emphasis on difficult samples.

The classification outputs from each branch (\(\hat{y}_{\text {temp}}\), \(\hat{y}_{\text {freq}}\), and \(\hat{y}_{\text {fusion}}\)) contribute to the total loss through their respective focal losses. The overall loss function \(\mathcal {L}_{\text {total}}\) is a weighted sum of the losses from each branch:

where \(\lambda _{\text {temp}}\), \(\lambda _{\text {freq}}\), and \(\lambda _{\text {fusion}}\) are weights balancing the losses, set to 1, 1, and 2, respectively, in this study. This multimodal supervision allows the network to learn more discriminative features across different modal, leading to improved performance and faster convergence during training.

Multi-Scale Mamba (MSM) module

Illustration of the Multi-Scale Mamba (MSM) module. Multiple convolutional branches with different kernel sizes (e.g., 3, 7, 14, 21) extract features at various temporal scales. The outputs are concatenated along the channel dimension, normalized using Layer Normalization, and projected back to the original channel size via a \(1 \times 1\) convolution.

The Multi-Scale Mamba (MSM) module, depicted in Fig. 3, is engineered to proficiently acquire temporal features across various scales by employing parallel convolutional branches with diverse kernel sizes, thereby enabling the extraction of features at distinct temporal resolutions.

Specifically, given an input feature map \(\varvec{X} \in \mathbb {R}^{L \times C}\), the MSM module applies four parallel 1D convolutional layers, each with a distinct kernel size \(k_i \in \{3, 7, 14, 21\}\):

where \(\text {Conv}_{k_i}\) represents a 1D convolution with kernel size \(k_i\). Each convolutional branch preserves the channel dimension C and is followed by the Mamba module to refine the features:

The kernel sizes of 3, 7, 14, 21 are chosen for physiological motivation, as the temporal structure of the sEMG reflects a hierarchy of muscle-electrical events-from the rapid depolarization of individual muscle fibers up through the coordinated discharge of motor units over tens of milliseconds. By matching convolutional kernel lengths to these physiological time-scales, the MSM module ensures each branch is tuned to capture a specific layer of neural-muscular activity:

-

Kernel size 3 (\(\approx\)1.5 ms at 2 kHz) This very narrow window aligns with the duration of an individual muscle fibre action potential at the skin surface, which is typically on the order of 1-2 ms51. The branch is therefore sensitive to the sharp onset and peak of single-fiber spikes, capturing the fastest temporal dynamics of muscle activation.

-

Kernel size 7 (\(\approx\)3.5 ms) Covering roughly the bi-phasic half-cycle of a motor unit action potential (MUAP), this mid-short kernel matches the early depolarization-repolarization phase (\(\approx\)3-5 ms)52. Capturing this half-wave detail aids in distinguishing subtle shape variations across different motor unit firings.

-

Kernel size 14 (\(\approx\)7 ms) Spanning the typical full half-width of a MUAP (\(\approx\)5-8 ms)52, this kernel size is tuned to the complete depolarization-repolarization cycle within a single motor unit burst. It thus extracts mid-range temporal features such as peak-to-peak duration and the summation of multiple fibers firing in close succession.

-

Kernel size 21 (\(\approx\)10.5 ms) Approaching the total duration of an MUAP (\(\approx\)8-14 ms)52 and overlapping with the lower bound of motor unit discharge clustering windows (5-20 ms)53, this branch captures the broader, slower components of muscle activity. It integrates over whole-burst waveforms and initial clustering patterns, which often correlate with force development and sustained contraction phases.

By aligning each convolutional branch with a known biophysical time-scale-from sub-millisecond individual fibre events up to \(\approx\)10 ms motor unit bursts-MSM can disentangle fast spikes, half-wave morphology, full-wave dynamics, and longer clustering patterns in parallel. This physiologically grounded, multi-resolution design enriches feature diversity and ultimately strengthens gesture discrimination, robustness, and cross-subject generalization.

To maintain consistent temporal alignment across branches and meet the downsampling requirements, MaxPooling is applied to normalize the sequence length to \(L_o\).

The outputs from the parallel branches, each representing features extracted at a different temporal resolution, are concatenated along the channel dimension:

This concatenation aggregates multi-scale information into a unified representation.

To integrate and refine the concatenated features, a \(1 \times 1\) convolutional layer is applied, which reduces the channel dimension back to C. Layer Normalization is then applied to stabilize the feature distribution:

The final output \(\varvec{X}_{\text {MSM}} \in \mathbb {R}^{L_o \times C}\) consolidates the multi-scale temporal features into a compact and expressive representation.

By leveraging parallel convolutional branches, Mamba-based feature refinement, and effective fusion through Layer Normalization and \(1 \times 1\) convolution, the MSM module achieves a balance between capturing diverse temporal scales and preserving computational efficiency.

Bi-directional attention fusion module (BAFM)

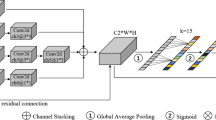

Structure of the Bi-directional Attention Fusion Module (BAFM). Two input feature maps are independently enhanced through \(1 \times 1\) convolutions, concatenated, and transformed via successive \(1 \times 1\) convolutions with Batch Normalization and ReLU activations. The final fusion combines the features using element-wise multiplications and integrates them through MaxPooling.

The proposed Bi-directional Attention Fusion Module (BAFM), depicted in Fig. 4, is designed to fuse features from different branches or subsets. BAFM facilitates bi-directional attention-based interactions between two input feature maps to produce a single, enriched output feature map.

To align two input feature maps \(\varvec{F}_1, \varvec{F}_2 \in \mathbb {R}^{L \times C}\) into a shared embedding space, BAFM first applies \(1 \times 1\) convolutions to each feature map, which is followed by Batch Normalization and a ReLU activation function:

where \(\varvec{f}_1\) and \(\varvec{f}_2\) represent ’enhanced’ or ’re-calibrated’ versions of the original input features. The \(1 \times 1\) convolution acts as a channel-wise feature projector, allowing the network to learn the optimal representation of each feature map in a shared embedding space before they are concatenated along the channel dimension:

The concatenated feature \(\varvec{f}_3\) (holding joint information from both streams) is processed by two successive \(1 \times 1\) convolutions, Batch Normalization and ReLU activation, to generate a fused feature to generate \(\varvec{f}_c\).

where feature map \(\varvec{f}_c\) acts as a learned ’fusion-gate’ or ’attention-weighting’ map, which is designed to learn and encapsulate the most salient and complementary information derived from the interaction of both input streams.

The final fused feature \(\varvec{F}\) is computed by a tri-linear interaction with a clear physical interpretation: \(\varvec{f}_c \odot \varvec{f}_1\): The ’fusion-gate’ \(\varvec{f}_c\) adaptively weights the enhanced features from the first stream (\(\varvec{f}_1\)). \(\varvec{f}_c \odot \varvec{f}_2\): The ’fusion-gate’ \(\varvec{f}_c\) similarly weights the enhanced features from the second stream (\(\varvec{f}_2\)). \(\varvec{f}_1 \odot \varvec{f}_2\): This term captures the direct, second-order interaction between the two feature streams, representing shared or co-dependent information. The fusion process can thus be expressed as:

where \(\odot\) denotes element-wise multiplication.

By summing these three components, the BAFM achieves a comprehensive fusion that considers not only the gated, salient features from each stream independently (via \(\varvec{f}_c\)) but also their direct mutual interaction (\(\varvec{f}_1 \odot \varvec{f}_2\)). This creates a highly enriched and context-aware final representation \(\varvec{F}\). A MaxPooling operation is then applied along the temporal dimension to reduce the feature length to the expected value of \(L_o\), resulting in the final output feature map \(\varvec{F}_{\text {out}} \in \mathbb {R}^{L_o \times C}\).

Experimental setup

Implementation details and evaluation metrics

The experiments were conducted using the PyTorch 2.1.1 library on a workstation with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 24GB GPU and an Intel i5-13600KF processor. Network parameters were optimized using the Adam optimizer, with an initial learning rate set at 0.001. For each subject, the training process consisted of 200 epochs, with a batch size of 1024.

The classification performance of proposed MSDS-FusionNet is validated using the following metrics:

where \(C\) is the number of classes, \(TP_i\) and \(FP_i\) are the true positives and false positives for class \(i\), respectively.

Performance comparison

We compared the proposed MSDS-FusionNet with state-of-the-art methods on the NinaPro DB2, DB3, and DB4 datasets. The performance of the models was evaluated using the same training and testing protocols, and the results were averaged across all subjects to provide a comprehensive assessment of the models’ generalization capabilities.

Ablation study

To further evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed MSDS-FusionNet, we conducted an ablation study to assess the contributions of the Temporal Branch, Frequency Branch, MSM, and BAFM. we compared the performance of the full model with four variants on the NinaPro DB2 dataset: (1) Temporal Branch only, (2) Frequency Branch only, (3) MSDS-FusionNet with all MSM replaced by conventional \(1 \times 1\) convolutional layer, and (4) MSDS-FusionNet with all BAFM replaced by simple channel concatenation and fused via a \(1 \times 1\) convolutional layer.

Evaluation of various fusion approaches

In addition to the ablation study, we evaluated the effectiveness of different fusion approaches within the MSDS-FusionNet framework. Specifically, we compared the proposed BAFM with alternative fusion methods, including:

-

Convolution-based: This method concatenates the features along the channel dimension and applies a \(1 \times 1\) convolution to fuse them.

-

Self-Attention-based: This method concatenates the features along the channel dimension and applies a fully connected layer and self-attention mechanism to learn the interactions between the features, followed by layer normalization.

-

Cross-Attention-based: This method employs a cross-attention mechanism to learn the interactions between the features followed by layer normalization, allowing for adaptive fusion based on the relevance of each feature.

-

Element-wise Addition: This method simply adds the features together, assuming they are aligned in terms of their dimensions.

-

Element-wise Multiplication: This method multiplies the features together, which can enhance the interaction between the features.

Each of these fusion methods was implemented within the MSDS-FusionNet framework, and their performance was evaluated on the NinaPro DB2 dataset. The results were compared to assess the effectiveness of the proposed BAFM in enhancing the model’s classification performance.

Cross-subject experiment

To evaluate the generalization performance of the proposed MSDS-FusionNet across different subjects, we conducted a cross-subject experiment on the NinaPro DB2 dataset. In this experiment, the model was trained using the 1st, 3rd, 4th, and 6th repetitions of each gesture from all subjects, while the 2nd and 5th repetitions were reserved for validation. This cross-subject evaluation provides insights into the model’s ability to generalize across different individuals and adapt to diverse sEMG patterns.

Computational cost analysis

To evaluate the computational cost of the proposed MSDS-FusionNet in real-world applications, we conducted an empirical analysis of the model’s inference time. The inference time was measured by averaging the time taken to process a single input sample across multiple runs, ensuring that the results are representative of typical operational conditions. This analysis provides insights into the model’s efficiency and suitability for real-time applications in sEMG-based gesture recognition.

Results and discussion

Performance comparison

The performance comparison of the proposed MSDS-FusionNet with state-of-the-art methods on the NinaPro DB2, DB3, and DB4 datasets is presented in Table 2. To rigorously validate our model’s superiority, we conducted one-sample t-tests comparing the mean accuracy of our proposed MSDS-FusionNet (derived from multiple runs) against the reported accuracy of each baseline method.

The proposed MSDS-FusionNet achieved a mean accuracy of 90.15% on the NinaPro DB2 dataset. This performance is statistically significantly higher (P < 0.05) than all compared baseline methods: Attention-CNN 18 (P-value < 0.001), Dilation LSTM 21 (P-value < 0.001), CNN-LSTM 20 (P-value = 0.001), DVMSCNN 26 (P-value < 0.001), CNN 54 (P-value < 0.001), MvCNN 22 (P-value = 0.002), Transformer 23 (P-value = 0.003), MSFF-net 24 (P-value = 0.007), ALR-CNN 25 (P-value = 0.019), and NKDFF-CNN 27 (P-value = 0.023). On the NinaPro DB3 dataset, MSDS-FusionNet achieved a mean accuracy of 72.32%. This represents a statistically significant improvement (P < 0.05) over all baselines: Bi-RSTF 19 (P-value < 0.001), DVMSCNN 26 (P-value = 0.001), MvCNN 22 (P-value < 0.001), ALR-CNN 25 (P-value < 0.001), RIE 28 (P-value < 0.001), and NKDFF-CNN 27 (P-value = 0.001). Furthermore, on the NinaPro DB4 dataset, MSDS-FusionNet achieved a mean accuracy of 87.10%, demonstrating statistically significant superiority (P < 0.05) compared to all existing methods: DVMSCNN 26 (P-value < 0.001), MvCNN 22 (P-value < 0.001), MSFF-net 24 (P-value = 0.001), RIE 28 (P-value = 0.001), and NKDFF-CNN 27 (P-value = 0.009).

These consistently statistically significant results robustly demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed MSDS-FusionNet in capturing multi-scale temporal and frequency features and fusing them through the BAFM module, leading to improved performance in hand gesture recognition tasks. The boxplot presented in Fig. 5 illustrates the classification accuracy of the proposed MSDS-FusionNet across the NinaPro DB2, DB3, and DB4 datasets among different subjects, highlighting the model’s robustness and generalization capabilities.

Confusion matrix analysis

To provide a deeper insight into the performance of the proposed MSDS-FusionNet, we conducted a detailed analysis of the confusion matrix on the NinaPro dataset, as shown in Fig. 6. This analysis reveals which specific gestures are most challenging for the model to classify, thereby offering practical insights for future improvements.

Overall, the model demonstrated exceptional performance on certain gestures, such as D-6 (Flexion of the thumb), which was classified with a perfect accuracy of 100.0%. This suggests that the sEMG signature for this specific gesture is highly distinct and well-captured by our model’s architecture. Conversely, some gestures proved to be particularly difficult, with C-3 (Fixed hook grasp) having the lowest accuracy at just 63.68%. The primary sources of these misclassifications are identified by examining the most significant confusion pairs in the matrix.

A high rate of confusion was observed between several pairs of gestures, particularly those with similar biomechanical or functional characteristics. For instance, C-5 (Medium wrap) was frequently misclassified as C-1 (Large diameter grasp) with a high error rate of 15.64%. Similarly, C-3 (Fixed hook grasp) was often confused with C-2 (Small diameter grasp), accounting for 12.77% of its misclassifications. These grasping gestures involve highly similar muscle synergies and activation patterns, leading to overlapping sEMG signals that are challenging to differentiate. The subtle differences in finger position or force distribution might not be adequately represented by the extracted sEMG features alone.

Another notable challenge was the distinction between similar wrist movements. For example, B-12 (Wrist pronation) was frequently mistaken for B-16 (Wrist ulnar deviation) (11.70% error rate), and B-11 (Wrist supination) was confused with B-12 (Wrist pronation) (3.26% error rate). These wrist movements engage complex and overlapping muscle groups, making the precise classification of their axes and directions difficult based on sEMG signals alone, which are inherently susceptible to cross-talk.

Furthermore, dynamic functional gestures presented significant challenges. C-22 (Turn a screw) was frequently misclassified as C-21 (Open a bottle) (11.12% error rate), and vice versa. The temporal and frequency characteristics of these gestures, both involving rotational hand movements, likely exhibit high similarity in their sEMG dynamics. The model struggled to capture the nuances that distinguish these actions, suggesting a need for more granular feature representation.

Based on this analysis, we identify several key factors contributing to the misclassifications: (1) Physiological Similarity: Many confused gestures share common muscle groups and activation patterns, leading to highly similar sEMG signals. (2) Subtle Biomechanical Differences: The fine details that differentiate similar gestures, such as the exact degree of finger flexion or the axis of wrist rotation, may not be salient enough in the sEMG signal to be effectively captured by the current model. (3) Signal Noise and Instability: Despite our preprocessing steps, sEMG signals remain prone to noise and inter-subject variability, which can obscure the subtle differences between gestures.

Limitations in feature extraction for similar muscle patterns

A deeper analysis of the feature extraction process reveals inherent limitations in distinguishing gestures with similar muscle activation patterns. Although the MSM module captures multi-scale temporal features through parallel convolutions with kernel sizes \(\{3, 7, 14, 21\}\), these kernels primarily focus on temporal resolution rather than spatial discrimination of muscle synergies. When two gestures activate overlapping muscle groups with similar timing patterns-such as C-5 (Medium wrap) and C-1 (Large diameter grasp), which both engage the flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus-the temporal features extracted by MSM exhibit high similarity, making them difficult to separate in the learned feature space.

Furthermore, the frequency branch, while capturing spectral characteristics through FFT and BiGRU processing, faces challenges when gestures exhibit similar frequency distributions despite different biomechanical functions. For instance, wrist movements like B-12 (Wrist pronation) and B-16 (Wrist ulnar deviation) generate comparable power spectral densities in the 20-150 Hz range, as they involve similar rates of motor unit recruitment. The BiGRU’s capacity to model temporal dependencies in the frequency domain is insufficient to resolve these subtle spectral differences, as the model lacks explicit mechanisms to emphasize discriminative frequency bands or to model the coupling between spatial electrode configurations and frequency content.

The BAFM fusion module, while effectively integrating temporal and frequency features through bi-directional attention, operates on already-extracted feature representations. When both temporal and frequency features are inherently similar for confused gesture pairs, the attention mechanism struggles to identify discriminative cues, leading to the observed misclassifications. This limitation suggests that sEMG signals alone may lack the necessary information richness to reliably distinguish all gesture types, particularly those involving complex, multi-joint coordination or subtle force variations that are not well-reflected in surface electrode recordings.

Ablation study

Performance and efficiency comparison

PCA visualization of the classification output data distribution for the proposed MSDS-FusionNet on an example subject in the NinaPro DB2 dataset. The 3D PCA projection illustrates the separability of different classes, with distinct clusters formed for each gesture category, with a Davies-Bouldin Index (DBI) of 2.1158, indicating strong discriminative power.

PCA visualization of the classification output data distribution for different ablation variants of the proposed MSDS-FusionNet on an example subject in the NinaPro DB2 dataset. Each subplot shows the 3D PCA projection of the network’s final layer output with a Davies-Bouldin Index (DBI) score, illustrating the separability of different classes.

The results of the ablation study are summarized in Table 3, and the classification accuracy for each model is visualized in Fig. 7. The Temporal Branch only model achieved an accuracy of 88.2%, while the Frequency Branch only model achieved 74.7%. The MSDS-FusionNet model without MSM achieved an accuracy of 86.3%, and the model without BAFM achieved 88.9%. The full MSDS-FusionNet model achieved the highest accuracy of 90.15%, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed architecture in capturing multi-scale temporal and frequency features and fusing them through the BAFM module.

In terms of computational efficiency, Table 3 also presents the number of parameters (Params) and Giga Floating Point Operations (GFLOPs) for each model. The Frequency Branch only model is the most lightweight in terms of parameters (0.52M) but suffers from the lowest accuracy. Conversely, the full MSDS-FusionNet model achieves the highest accuracy with a modest increase in computational load (3.71M Params, 0.37 GFLOPs) compared to its variants. Notably, removing the MSM module significantly reduces the model’s complexity but leads to a substantial drop in accuracy, indicating that the MSM module provides a significant performance gain for a reasonable computational cost. Similarly, the BAFM module adds minimal computational overhead (0.1M Params and 0.01 GFLOPs) while providing a crucial \(1.25\%\) accuracy improvement. Overall, the full MSDS-FusionNet model demonstrates a superior trade-off between classification performance and computational efficiency, justifying the inclusion of all its components.

PCA visualization and discriminative power analysis

To assess the discriminative power of features learned by our model, we performed Principal Component Analysis (PCA) visualization, generated using the matplotlib library (version 3.9.2, https://matplotlib.org/) in Python (version 3.9.7, https://www.python.org/), on the classification output data distribution of single samples from MSDS-FusionNet and its ablated variants on the NinaPro DB2 dataset. Additionally, we used the Davies-Bouldin Index (DBI) to quantify the clustering effect, where a smaller DBI value indicates tighter intra-class compactness and greater inter-class separation, signifying higher feature discriminability 55.

As depicted in Fig. 8, the complete MSDS-FusionNet model effectively separates different categories, forming relatively clear clusters. This demonstrates that the features it learns possess strong discriminative capabilities. This finding is further corroborated by its DBI score of 2.1158, which is the lowest among all variants, quantitatively confirming its superior performance in distinguishing between classes.

Conversely, Fig. 9 illustrates that the ablated variants exhibit varying degrees of reduction in feature discriminative ability. For instance, single-branch models, which include only a temporal branch (Fig. 9b) or a frequency branch (Fig. 9a), show severe overlap in their class clusters, making differentiation challenging. Their DBI scores of 4.1326 and 4.3483, respectively, are significantly higher than the complete model. This highlights the critical necessity of fusing both temporal and frequency features, as they provide complementary information essential for distinguishing complex gestures.

When the proposed MSM module is removed (Fig. 9d), the discriminability of the feature distribution dramatically decreases, with its DBI score soaring to 4.4900, the worst among all models. This intuitively proves the crucial role of MSM in capturing multi-scale temporal features and significantly enhancing the model’s representation capabilities.

Similarly, removing the proposed BAFM (Fig. 9c) results in a clustering effect that, while superior to the single-branch and no-MSM models, shows noticeably reduced inter-cluster separation compared to the complete model. Its DBI score of 2.3615 is slightly higher than the complete model. This confirms the importance of the BAFM module for efficient and dynamic fusion of multimodal features, contributing to the model’s ability to create well-separated clusters.

In summary, both the qualitative PCA visualization results and the quantitative DBI scores consistently indicate that the complete MSDS-FusionNet architecture is most effective at learning highly discriminative gesture features. Furthermore, these findings emphatically demonstrate that each of its core components-the temporal/frequency dual branches, MSM, and BAFM-makes an indispensable contribution to the final performance, underscoring the synergistic benefits of their integration.

Insights into the importance of each branch and module

The Temporal Branch only model is unable to capture frequency-domain features, which provide critical insights into muscle activation patterns that are not readily apparent in the time domain. Studies have shown that different hand gestures are often associated with distinct frequency patterns in sEMG signals, enhancing the accuracy of classification models37,56. Specifically, higher frequency bands tend to reflect fast muscle contractions, while lower frequencies are associated with slower movements and muscle relaxation31. By analyzing the frequency spectrum of sEMG signals, the Frequency Branch can help distinguish subtle differences between gestures, thereby improving the overall performance of the hand gesture recognition system.

In contrast, the Frequency Branch only model lacks the ability to capture temporal dependencies, which are crucial for understanding the dynamic patterns of muscle activity. Temporal features provide information about the sequence of muscle activations during a gesture, enabling the model to differentiate between similar gestures with distinct temporal characteristics. By leveraging multi-scale temporal features, the Temporal Branch can effectively capture the temporal dynamics of muscle contractions, enhancing the model’s ability to recognize complex hand gestures.

The ablated MSDS-FusionNet model without MSM achieved a lower accuracy of 86.3%, indicating that the MSM modules play a crucial role in capturing multi-scale temporal features. The MSM modules enable the network to extract features at different temporal resolutions, providing a comprehensive representation of the sEMG signals. By leveraging multi-scale features, the network can capture both short-term and long-term temporal dependencies, enhancing the model’s ability to recognize a wide range of hand gestures.

Similarly, the ablated MSDS-FusionNet model without BAFM achieved a lower accuracy of 88.9%, highlighting the importance of the BAFM module in fusing features from different Branches. The BAFM module enables the network to integrate complementary information from the Temporal and Frequency Branches, enhancing the model’s ability to capture both temporal and frequency-domain features. By leveraging bi-directional attention-based interactions, the BAFM module can effectively combine features from different modalities, improving the model’s performance in hand gesture recognition tasks.

Evaluation of various fusion approaches

Table 4 presents a comprehensive performance comparison of different fusion methods within the MSDS-FusionNet framework on the NinaPro DB2 dataset. Our proposed BAFM consistently outperforms all other evaluated fusion strategies, achieving the highest accuracy of 90.15%, precision (macro) of 89.82%, and recall (macro) of 89.34%. This highlights the superior capability of BAFM in effectively integrating multi-scale temporal and frequency features for enhanced gesture classification.

A detailed analysis of individual fusion methods reveals distinct performance characteristics. The simplest fusion approaches, Element-wise Addition and Element-wise Multiplication, yielded the lowest accuracies of 88.75% and 88.50%, respectively. These methods combine features at a basic element level without considering their complex interdependencies or relative importance. While computationally inexpensive (indicated by ’-’ in the Params column as they typically don’t introduce learnable parameters for fusion itself), their inability to dynamically weigh or transform features limits their efficacy in capturing nuanced information from complementary domains. Element-wise multiplication, in particular, showed slightly worse performance than addition, possibly due to its sensitivity to feature scales and potential for suppressing valuable information if one feature type has small values.

The Convolution-based method, with 8,256 parameters, achieved an accuracy of 88.91%. This approach typically uses convolutional layers to learn local patterns across fused features. While it introduces learnable parameters, its performance is modest compared to attention-based methods. This suggests that convolutions, while effective for spatial feature extraction, may not be optimally suited for complex inter-domain feature fusion without more sophisticated architectures, as their localized receptive fields might struggle to capture long-range dependencies or global correlations between the temporal and frequency streams.

Moving to attention-based approaches, the Self-Attention-based method, involving 25,024 parameters, improved performance to 89.12% accuracy. This method allows the model to weigh the importance of different parts of the input features within a single stream (or concatenated streams). While a notable improvement over element-wise and convolution-based methods, indicating the benefit of learning dependencies, its performance is still limited. This could be attributed to its focus on internal dependencies, which might not fully leverage the distinct and complementary information present across separate temporal and frequency domains. In contrast, the Cross-Attention-based method, with 16,768 parameters, achieved a higher accuracy of 89.45%. This approach explicitly models the interactions between two distinct sets of features (e.g., temporal and frequency features), allowing each stream to query and attend to information from the other. The superior performance of cross-attention over self-attention suggests that actively learning the relationships between the two different feature domains is crucial for effective fusion, enabling a more targeted integration of information and leading to better discriminative power.

Finally, the proposed BAFM, with 33,856 parameters, achieved the best performance across all metrics. This demonstrates its effectiveness in enhancing the model’s classification performance by dynamically and adaptively fusing multi-scale temporal and frequency features. The BAFM’s design, which incorporates a mechanism to adaptively weight the contributions of different features based on their relevance and to capture complex interactions between the temporal and frequency domains, leads to superior information integration. The increased parameter count compared to other methods is justified by the significant boost in accuracy, precision, and recall, indicating that the additional complexity translates into a more sophisticated and effective fusion mechanism capable of discerning intricate patterns crucial for high-accuracy gesture classification.

These results collectively highlight that simple concatenation or localized fusion mechanisms are insufficient for optimal integration of diverse feature streams. Attention-based mechanisms, particularly cross-attention and our proposed BAFM, which dynamically model inter-feature relationships, are essential for leveraging the complementary information from both time and frequency domains, thereby leading to improved classification accuracy and robustness. The BAFM’s superior performance underscores the importance of a sophisticated and adaptive fusion strategy that can learn to weigh the contributions of different features based on their relevance and capture complex interactions.

Cross-subject experiment

The results of the cross-subject experiment on the NinaPro DB2 dataset are summarized in Table 5. The proposed MSDS-FusionNet achieved an accuracy of 85.72% in the cross-subject evaluation, demonstrating its ability to generalize across different individuals and adapt to diverse sEMG patterns. The model’s performance remained consistent across different subjects, indicating that the proposed architecture can effectively capture multi-scale temporal and frequency features and fuse them to improve classification performance. These results highlight the robustness and generalization capabilities of the MSDS-FusionNet in sEMG-based hand gesture recognition tasks.

Computational cost analysis

In addition to the theoretical complexity mentioned in the Tables 2 and 3, we conducted empirical measurements of computational cost to better reflect the model’s deployment feasibility. Specifically, we evaluated the inference performance of MSDS-FusionNet on an NVIDIA RTX 4080 GPU using PyTorch. Each inference was conducted on a single input sample of shape \(400 \times 12\), and the forward pass time was averaged over 500 trials after a warm-up phase of 10 runs. The resulting average inference time is 16.82 milliseconds per sample. During inference, the peak GPU memory consumption was measured to be 150.78 MB using PyTorch’s memory profiling tools. This empirical analysis indicates that the MSDS-FusionNet, while computationally intensive, is capable of achieving real-time performance for sEMG-based hand gesture recognition tasks. The model’s inference time of 16.82 ms per sample is suitable for applications requiring rapid response times, such as human-computer interaction and prosthetic control.

Limitations and future work

Although MSDS-FusionNet achieves state-of-the-art accuracy in sEMG-based hand-gesture recognition, its substantial model size and computational demands temper its broader applicability. With 3.71 million parameters and a 0.37 GFLOPs footprint-of which 3.15 million reside in the temporal branch-the network significantly exceeds the lightweight profiles of competing methods such as NKDFF-CNN (0.62 M) and RIE (0.89 M). This complexity may hinder real-time inference on embedded or wearable platforms with limited processing power and energy budgets. Moreover, all evaluations have been conducted on the NinaPro dataset under controlled laboratory conditions with standardized electrode placement and consistent signal quality. Our preprocessing pipeline-comprising 10–500 Hz band-pass filtering, a 50 Hz notch filter, wavelet denoising, and fixed 200 ms sliding windows with 5 ms overlap-assumes that physiological information is preserved and artifacts are removed uniformly across subjects and sessions. Yet, environmental factors such as strong electromagnetic interference, prolonged muscle fatigue, or electrode displacement beyond our simulated augmentations may degrade performance in real-world settings.

The predominance of subject-dependent training in our experiments further constrains the model’s immediate generalizability. While cross-subject evaluations indicate some transferability, MSDS-FusionNet still relies on per-user calibration to achieve peak accuracy. This limitation poses challenges for applications like prosthetic control or rehabilitation robotics, where rapid out-of-the-box functionality is crucial. Finally, the network’s multi-branch fusion architecture, though powerful, offers limited insight into which temporal or spectral features drive each classification decision. Without built-in mechanisms for interpretability-such as attention mechanisms or visualization tools-it remains difficult to diagnose errors or build user trust in clinical and assistive contexts.

A detailed analysis of the confusion matrix reveals that despite the high overall accuracy, the model struggles to distinguish between specific gestures that are biomechanically or physiologically similar. For example, the significant confusion between C-5 (Medium wrap) and C-1 (Large diameter grasp), or the low accuracy for C-3 (Fixed hook grasp) due to its frequent misclassification as C-2 (Small diameter grasp), highlights a key challenge. These misclassifications underscore the difficulty of capturing subtle, yet critical, differences in muscle activation patterns solely from sEMG signals.

To address these limitations, future research should explore multi-modal fusion to enhance feature discriminability. Integrating inertial measurement units (IMUs) data can provide 3D motion and rotation context to distinguish similar sEMG patterns, while force sensors offer contact and grip information to differentiate grasp types. Together, these modalities complement sEMG by capturing both kinematic and mechanical features across different temporal scales, improving robustness against signal variability. Furthermore, the use of specialized loss functions, such as a contrastive loss or a focal loss variant, could be employed to explicitly penalize misclassifications of these difficult-to-distinguish gesture pairs, forcing the model to learn more separated feature representations.

In addition, future research should pursue both data-centric and model-centric strategies. On the data side, incorporating adversarial training 57 and unsupervised domain-adaptation techniques 58 can expose the model to worst-case distortions and align feature distributions across different hardware setups or recording protocols. Expanding our dataset to include sEMG recordings under diverse environmental conditions-outdoor activity, motion artifacts, varying temperatures-and from a wider range of electrode types will further bolster robustness. In parallel, model compression techniques such as structured pruning, low-precision quantization, and knowledge distillation can dramatically reduce parameter counts and FLOPs, enabling deployment on low-power microcontrollers and embedded GPUs without sacrificing accuracy.

Improving interpretability is another key direction. Embedding self- or cross-modal attention layers would allow the network to highlight the most discriminative time-frequency regions, while tailored saliency-map visualizations (e.g., Grad-CAM for sEMG inputs) could reveal which signal segments drive each decision 59,60. From a learning-to-learn perspective, meta-learning frameworks like MAML could empower rapid fine-tuning on new users with only a handful of calibration samples 61, and continual-learning algorithms 62 could adapt to signal drift over extended use without forgetting previously learned patterns. Finally, piloting compressed versions of MSDS-FusionNet in real-time hand-gesture interfaces-such as wearable prosthetics or rehabilitation robots-will provide critical feedback on latency, energy consumption, recognition accuracy, and user experience. Such application-level trials are essential to validate the network’s practical viability and to identify any remaining challenges before widespread deployment.

Conclusion

In this study, we proposed a novel Multi-Scale Dual-Stream Fusion Network (MSDS-FusionNet) for sEMG-based hand gesture recognition. The proposed architecture leverages multi-scale temporal and frequency features extracted through the Temporal and Frequency Branches, respectively, and fuses them using the Bi-directional Attention Fusion Module (BAFM). The network is trained with deep supervision strategies to enhance feature learning and improve model generalization. Experimental results on the NinaPro DB2, DB3, and DB4 datasets demonstrate that the proposed MSDS-FusionNet outperforms state-of-the-art methods in hand gesture recognition tasks. The ablation study further confirms the effectiveness of the Temporal Branch, Frequency Branch, MSM, and BAFM in capturing multi-scale temporal and frequency features and fusing them to improve classification performance. The evaluation of different fusion methods within the MSDS-FusionNet framework highlights the superiority of the BAFM in effectively integrating multi-scale features, achieving the highest accuracy and precision. The Cross-subject experiment demonstrates the model’s ability to generalize across different individuals and adapt to diverse sEMG patterns. The proposed MSDS-FusionNet provides a robust and efficient solution for sEMG-based hand gesture recognition, with potential applications in human-computer interaction, prosthetic control, and rehabilitation robotics. Future work will focus on enhancing the model’s interpretability, reducing its computational complexity, and improving its generalization capabilities across diverse real-world scenarios. Additionally, exploring multi-modal fusion approaches and incorporating advanced feature extraction techniques will further enhance the model’s performance and applicability in practical settings.

Data availability

The NinaPro database used in this study are publicly available in https://ninapro.hevs.ch/. The code for the proposed MSDS-FusionNet is available in https: //github.com/hdy6438/MSDS-FusionNet.

References

Atzori, M. et al. Electromyography data for non-invasive naturally-controlled robotic hand prostheses. Sci. Data1, 140053. https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2014.53 (2014).

Pizzolato, S. et al. Comparison of six electromyography acquisition setups on hand movement classification tasks. PLoS ONE12, e0186132. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0186132 (2017).

Smith, J. & Doe, A. Subject-dependent models for surface electromyography analysis. J. Biomech.33, 123–134 (2020).

Wang, R. & Liu, Y. Cross-subject analysis in biometric models: Methods and evaluation. Pattern Recogn. Lett.33, 789–797 (2019).

Furno, G. & Tompkins, W. J. A learning filter for removing noise interference. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical EngineeringBME-30, 234–238, https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.1983.325225 (1983).

Abe, M., Yamashita, H., Jinno, S., Custance, O. & Toki, H. Reduction of noise induced by power supply lines using phase-locked loop. Rev. Sci. Instrum.93, 113901. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0124433 (2022).

Chen, J., Sun, Y., Sun, S. & Yao, Z. Reducing power line interference from semg signals based on synchrosqueezed wavelet transform. Sensors23, 5182. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23115182 (2023).

Chen, P., Li, Z., Togo, S., Yokoi, H. & Jiang, Y. A layered semg-fmg hybrid sensor for hand motion recognition from forearm muscle activities. IEEE Trans. Hum.-Mach. Syst.53, 935–944 (2023).

Chen, P. et al. Intra-and inter-channel deep convolutional neural network with dynamic label smoothing for multichannel biosignal analysis. Neural Netw.183, 106960 (2025).

Zafar, M. H., Langås, E. F. & Sanfilippo, F. Empowering human-robot interaction using semg sensor: Hybrid deep learning model for accurate hand gesture recognition. Results Eng.20, 101639 (2023).

Guo, L., Lu, Z. & Yao, L. Human-machine interaction sensing technology based on hand gesture recognition: A review. IEEE Trans. Hum.-Mach. Syst.51, 300–309 (2021).

Kadavath, M. R. K., Nasor, M. & Imran, A. Enhanced hand gesture recognition with surface electromyogram and machine learning. Sensors24, 5231 (2024).

Ni, S. et al. A survey on hand gesture recognition based on surface electromyography: Fundamentals, methods, applications, challenges and future trends. Applied Soft Computing 112235 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Yang, F., Fan, Q., Yang, A. & Li, X. Research on semg-based gesture recognition by dual-view deep learning. IEEE Access10, 32928–32937 (2023).

Li, W., Shi, P. & Yu, H. Gesture recognition using surface electromyography and deep learning for prostheses hand: state-of-the-art, challenges, and future. Front. Neurosci.15, 621885 (2021).

Xiong, B. et al. A global and local feature fused cnn architecture for the semg-based hand gesture recognition. Comput. Biol. Med.166, 107497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2023.107497 (2023).

Tuncer, S. A. & Alkan, A. Classification of emg signals taken from arm with hybrid cnn-svm architecture. Concurrency Computat. Pract. Exp.34, e6746 (2022).

Hu, Y. et al. A novel attention-based hybrid cnn-rnn architecture for semg-based gesture recognition. PLoS ONE13, e0206049 (2018).

Khushaba, R. N. et al. A long short-term recurrent spatial-temporal fusion for myoelectric pattern recognition. Expert Syst. Appl.178, 114977 (2021).

Kim, J.-S., Kim, M.-G. & Pan, S.-B. Two-step biometrics using electromyogram signal based on convolutional neural network-long short-term memory networks. Appl. Sci.11, 6824 (2021).

Sun, T., Hu, Q., Gulati, P. & Atashzar, S. F. Temporal dilation of deep lstm for agile decoding of semg: Application in prediction of upper-limb motor intention in neurorobotics. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett.6, 6212–6219 (2021).

Wei, W., Hong, H. & Wu, X. A hierarchical view pooling network for multichannel surface electromyography-based gesture recognition. Comput. Intell. Neurosci.2021, 6591035 (2021).

Zabihi, S., Rahimian, E., Asif, A. & Mohammadi, A. Trahgr: Transformer for hand gesture recognition via electromyography. IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering (2023).

Peng, X., Zhou, X., Zhu, H., Ke, Z. & Pan, C. Msff-net: multi-stream feature fusion network for surface electromyography gesture recognition. PLoS ONE17, e0276436 (2022).

Fatayer, A., Gao, W. & Fu, Y. semg-based gesture recognition using deep learning from noisy labels. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform.26, 4462–4473 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Yang, F., Fan, Q., Yang, A. & Li, X. Research on semg-based gesture recognition by dual-view deep learning. IEEE Access10, 32928–32937 (2022).

Jiang, B. et al. Nkdff-cnn: A convolutional neural network with narrow kernel and dual-view feature fusion for multitype gesture recognition based on semg. Digital Signal Processing156, 104772 (2025).

Jiang, B. et al. An efficient surface electromyography-based gesture recognition algorithm based on multiscale fusion convolution and channel attention. Sci. Rep.14, 30867 (2024).

Nguyen, P.T.-T., Su, S.-F. & Kuo, C.-H. A frequency-based attention neural network and subject-adaptive transfer learning for semg hand gesture classification. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett.9, 7835–7842. https://doi.org/10.1109/LRA.2024.3433748 (2024).

Ni, S. et al. A survey on hand gesture recognition based on surface electromyography: Fundamentals, methods, applications, challenges and future trends. Appl. Soft Comput.166, 112235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asoc.2024.112235 (2024).

Politti, F., Casellato, C., Kalytczak, M. M., Garcia, M. B. S. & Biasotto-Gonzalez, D. A. Characteristics of emg frequency bands in temporomandibullar disorders patients. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol.31, 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jelekin.2016.10.006 (2016).

Liu, Y., Zhou, J., Zhou, D. & Peng, L. Quantitative assessment of muscle fatigue based on improved gramian angular difference field. IEEE Sens. J.24, 32966–32980. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2024.3456479 (2024).

Li, N. et al. Non-invasive techniques for muscle fatigue monitoring: A comprehensive survey. ACM Comput. Surv.56, 1–40 (2024).

Gao, R. et al. Study on the nonfatigue and fatigue states of orchard workers based on electrocardiogram signal analysis. Sci. Rep.12, 4858 (2022).

Sun, J. et al. Application of surface electromyography in exercise fatigue: a review. Front. Syst. Neurosci.16, 893275 (2022).

Chen, W., Niu, Y., Gan, Z., Xiong, B. & Huang, S. Spatial feature integration in multidimensional electromyography analysis for hand gesture recognition. Appl. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/app132413332 (2023).

He, H. & Wu, D. Transfer learning for brain-computer interfaces: A euclidean space data alignment approach. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng.67, 399–410 (2019).

Côté-Allard, U. et al. Deep learning for electromyographic hand gesture signal classification using transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng.27, 760–771 (2019).

Gu, A. & Dao, T. Mamba: Linear-time sequence modeling with selective state spaces. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.00752 (2023).

Zhang, D., Niu, H. & Jiang, M. Modeling of islanding detection by sensing jump change of harmonic voltage at pcc by the combination of a narrow band-pass filter and wavelet analysis. In 2013 IEEE ECCE Asia Downunder, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1109/ECCE-ASIA.2013.6579275 (2013).

Diab, M. S. & Mahmoud, S. A 6nw seventh-order ota-c band pass filter for continuous wavelet transform. In 2019 International SoC Design Conference (ISOCC), 22–26, https://doi.org/10.1109/ISOCC47750.2019.9027752 (2019).

Han, D., Pei, L., An, S. & Shi, P. Multi-frequency weak signal detection based on wavelet transform and parameter compensation band-pass multi-stable stochastic resonance. Mech. Syst. Signal Process.70–71, 937–951. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.YMSSP.2015.09.003 (2016).

Lee, T. & Kim, S. Partitioning strategies in time-series data for neural network training. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw.25, 543–555 (2018).

Brown, C. et al. Addressing class imbalance in electromyography-based gesture recognition. Front. Neurosci.14, 976 (2021).

Zhang, C. et al. An end-to-end lower limb activity recognition framework based on semg data augmentation and enhanced capsnet. Expert Syst. Appl.213, 120257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2023.120257 (2023).

Nanthini, K. et al. A survey on data augmentation techniques. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Communication and Computing (ICCMC), 10084010, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCMC56507.2023.10084010 (2023).

Fons, E., Dawson, P., Zeng, X.-J., Keane, J. & Iosifidis, A. Adaptive weighting scheme for automatic time-series data augmentation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.08310 (2021).

Lee, M. A. et al. Making sense of vision and touch: Self-supervised learning of multimodal representations for contact-rich tasks. In 2019 International conference on robotics and automation (ICRA), 8943–8950 (IEEE, 2019).

Cho, K. et al. Learning phrase representations using rnn encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1406.1078 (2014).

Lin, T. Focal loss for dense object detection. arXiv preprint arXiv:1708.02002 (2017).

Merletti, R. & Muceli, S. Tutorial surface emg detection in space and time: Best practices. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol.49, 102363 (2019).

Dumitru, D., King, J. C. & Zwarts, M. J. Determinants of motor unit action potential duration. Clin. Neurophysiol.110, 1876–1882 (1999).

Asmussen, M. J., Von Tscharner, V. & Nigg, B. M. Motor unit action potential clustering-theoretical consideration for muscle activation during a motor task. Front. Hum. Neurosci.12, 15 (2018).

Xing, K. et al. Hand gesture recognition based on deep learning method. In 2018 IEEE Third International Conference on Data Science in Cyberspace (DSC), 542–546 (IEEE, 2018).

Zhang, S., Zhou, H., Tchantchane, R. & Alici, G. A wearable human-machine-interface (hmi) system based on colocated emg-pfmg sensing for hand gesture recognition. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron.30, 369–380 (2024).

Too, J., Abdullah, A. R., Zawawi, T. T., Saad, N. M. & Musa, H. Classification of emg signal based on time domain and frequency domain features. Int. J. Hum. Technol. Interact. (IJHaTI)1, 25–30 (2017).

Xie, H. Radio adversarial attacks on emg-based gesture recognition networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.21387 (2025).

Chan, P. P. et al. Unsupervised domain adaptation for gesture identification against electrode shift. IEEE Trans. Hum.-Mach. Syst.52, 1271–1280 (2022).

Côté-Allard, U. et al. Interpreting deep learning features for myoelectric control: A comparison with handcrafted features. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol.8, 158 (2020).

Tolooshams, B. et al. Interpretable deep learning for deconvolutional analysis of neural signals. Neuron113, 1151–1168 (2025).

Du, G. et al. Meta-transfer-learning-based multimodal human pose estimation for lower limbs. Sensors25, 1613 (2025).

Li, A., Li, H. & Yuan, G. Continual learning with deep neural networks in physiological signal data: a survey. In Healthcare, vol. 12, 155 (MDPI, 2024).

Acknowledgements