Abstract

The effects of absorber structure–controlled by adjusting the thickness ratio of doped and undoped InGaAs layers–and metal-semiconductor interface treatment methods were investigated in waveguide-type UTC-PDs. Ultraviolet-ozone (UVO) and ammonia solution cleaning of the InGaAs surface improved the interface quality in terms of contact resistivity and bias-temperature stability. Nevertheless, devices cleaned using buffered oxide etchant (BOE) exhibited higher photoresponsivity and superior frequency characteristics. This phenomenon is attributed to the reduction of dark current (IDark) caused by the residual interfacial oxide layer at the metal/InGaAs interface. In contrast, the influence of absorber structure variation was negligible. These results demonstrate that the interface condition plays a more dominant role than absorber modification in determining device performance. Therefore, optimizing the interface condition while maintaining a high-quality oxide layer is essential for further enhancing UTC-PD performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The performance of microwave and millimeter-wave photonic systems strongly depends on photodiodes (PDs) with high saturation power, wide bandwidth, and high responsivity1. PDs are essential components in radio-over-fiber links, phased-array antennas, and the photonic generation of terahertz (THz) signals2,3,4. However, the output linearity and frequency response of PDs are often limited by the space-charge effect, which originates from the spatial distribution of photo-generated carriers within the depletion region. The accumulated charge screens the internal electric field and reduces carrier transport efficiency, which can lead to current saturation and gain compression under high optical input power5,6. Furthermore, the space-charge effect, in conjunction with the intrinsic trade-off between optical absorption and carrier transit time in conventional p-i-n PDs, severely restricts both bandwidth and power handling capabilities. To simultaneously achieve high power and high bandwidth, the uni-traveling-carrier photodiodes (UTC-PD) structure was proposed in 19977. The UTC-PD selectively uses electron transport in a p-type InGaAs absorber, where electrons are generated as minority carriers, while excluding the slower hole transport. In this structure, a wide-bandgap InP electron collection layer (collector) and a diffusion-barrier layer enable unidirectional electron transport toward the collector, maintaining charge neutrality through background holes in the absorber8. With electrons traveling ballistically at high velocity in the depleted collector and with suppression of the space-charge effect, the UTC-PD achieves high linearity, high saturation output power, and wide bandwidth9.

Recent studies have focused on further improving the efficiency of UTC-PDs to enhance RF output power while maintaining high bandwidth; thus, modified UTC-PD structures incorporating an undoped absorber layer have been investigated10,11,12,13. On the other hand, for conventional PDs, efforts to achieve higher frequency performance and lower dark current have led to evaluations of the effects of the metal-semiconductor interfacial oxide layer and interface treatment methods for passivation14,15. Similarly, in the field of photovoltaics, it has been demonstrated that minimizing interfacial defect states through effective surface treatment is essential for suppressing carrier recombination and improving device efficiency16. However, the combined effects of absorber structure and interface treatment on UTC-PD characteristics have not been systematically investigated.

In this study, we investigate the influence of the absorber configuration—controlled by the thickness ratio of doped and undoped InGaAs layers—and the metal-semiconductor interface cleaning methods on the DC, reliability, photocurrent, and frequency performance of UTC-PDs. The UVO cleaning method was used to improve the quality of metal-semiconductor interface by restoring the stoichiometric composition17,18. In addition, a waveguide structure was employed to achieve a more uniform optical-power distribution in the absorber through light incidence via evanescent-coupling effect19,20,21,22. The experimental results reveal that the interface condition plays a more dominant role than absorber modification in determining the dark current, photoresponsivity, and overall device reliability. This finding highlights the critical importance of developing optimized interfacial oxides and surface-cleaning processes for achieving superior UTC-PD performance.

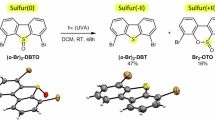

Fabrications

The epitaxial layer structures for UTC-PDs were grown on 2-inch InP substrates and consisted of a 1.15 μm InP/InGaAsP/InP waveguide layer, a 250 nm InGaAsP matching layer, a 120 nm n+-InP n-contact layer, a 155 nm InP collector, a 90 nm InGaAs absorber layer, a 20 nm p+-InP diffusion barrier, and a 50 nm p+-InGaAs p-contact layer. The detailed epitaxial structure is summarized in Table 1. Absorber-A comprised 30 nm of p+-InGaAs and 60 nm of undoped InGaAs, whereas Absorber-B consisted of 60 nm of p+-InGaAs and 30 nm of undoped InGaAs, as illustrated in Fig. 1 (a) and (b). To form the active mesa region, Ti/Pt/Au (300/200/3000 Å) metal stacks were deposited for p-contact metallization using i-line stepper photolithography and electron-beam evaporation. Rapid thermal annealing (RTA) was then performed at 425 °C for 30 s in an H2/N2 (30%) atmosphere. Afterward, a SiNX hard mask was deposited, and the epitaxial layers were etched by reactive ion etching (RIE) to a depth of approximately 2500 Å, followed by sequential wet-etching: the damaged layer was removed using an HBr solution (HBr : H2O2 : H2O = 8 : 2 : 100), and InP layer was etched using H3PO4: HCl = 6 : 1, and the InGaAsP layer was etched using H2SO4 : H2O2 : H2O = 1 : 1 : 10. As shown in Fig. 1 (d) and (e), the matching layer and waveguide were etched using both RIE and wet etching. The waveguide was tapered to a wider width toward the active mesa to enhance optical coupling efficiency. For n-contact metallization, Ni/Ge/Au/Ni/Au (50/300/500/200/7000 Å) metal stacks were deposited. Prior to p- and n-contact metallization, the surfaces of the p+-InGaAs p-contact and n+-InP n-contact layers were treated using either UVO or BOE cleaning. In the UVO treatment, the surfaces were oxidized under an O2 flow rate 0.5 L/min using a UV lamp and ozone generator for 10 min. The interfacial oxide layer formed by UVO was removed using an ammonia solution (NH4OH : H2O = 1 : 20) for 10 s, without deionized (DI) water rinsing. The UVO exposure time was optimized to 10 min to maximize the oxidation effect23. In contrast, BOE cleaning was performed using a 30 : 1 solution for 10 s, followed by DI rinsing 30 s. The Au thickness of 7000 Å in the Ni/Ge/Au/Ni/Au stack was chosen to match the top height of the p- and n-metal layers. The metal stacks were annealed at 375 °C for 30 s in an H2/N2 (30%) atmosphere. After p- and n-contact metallization, surface planarization was performed using a benzocyclobutene (BCB, Dow cyclotene 3022-46) layer with a 70 nm SiNX adhesion layer. The spin coating was performed at 5000 rpm for 30 s. After curing at 280 °C for 1 h under vacuum, the BCB layer showed a final thickness of approximately 2.4 μm. The BCB layer was then etched to the target height to expose the p- and n-contact metals using RIE with a CF4/O2 gas mixture. Figure 1 (f) shows a cross-sectional Focused Ion Beam-Scanning Electron Microscope (FIB-SEM) image of the fabricated UTC-PD structure. Finally, a Ti/Au metal extender and ~ 2 μm-thick Au electroplating were used to form the antenna pattern, as shown in Fig. 1 (c). The DC characteristics of the fabricated devices were measured using a Keysight B1500A semiconductor device analyzer for I–V analysis and a Keysight B1520A multi-frequency capacitance measurement unit (MFCMU) for capacitance measurement. In this study, devices with Absorber-A and UVO-treated interface are denoted as A-UVO, Absorber-B and UVO treatment as B-UVO, and Absorber-B and BOE treatment as B-BOE.

Modified UTC-PD band diagrams of (a) Sample-A with absorber-A and (b) Sample-B with absorber-B. (c) Top-view optical image of the fabricated UTC-PD with the antenna pattern. (d) Cross-sectional FIB-SEM image showing the matching layer and waveguide. (e) Top-view optical image of the fabricated UTC-PD before antenna formation. (f) Cross-sectional FIB-SEM image of the UTC-PD structure.

Results and discussion

Figure 2 (a) shows the resistance values extracted from transfer length method (TLM) measurements for devices with different absorber structures and metal-semiconductor interface treatments using UVO and BOE cleaning. The resistances of A-UVO (black squares) and B-UVO (red circles) are quite similar over the measured gap spacing range, whereas that of B-BOE (blue triangles) is noticeably lower than those of the UVO-treated devices. For quantitative comparison, the specific contact resistivity (ρc) and the semiconductor sheet resistance (Rsh) were determined from linear fitting of the measured TLM data. The parameters were extracted using the extrapolated transfer length (Lt) and contact resistance (Rc), based on the following relations: \({\rho _c}={L_t}^{2} \cdot {R_{sh}}\) and \({R_{sh}}={R_c} \cdot W/{L_t}\). The values of Rc and Lt were obtained from the total resistance relation using Eq. (1), where d is gap spacing and Z is the contact width.

In this experiment, the TLM gap spacing varied from 2 μm to 30 μm, and the TLM pattern width was 200 μm. The extracted contact resistivities of A-UVO and B-UVO are 1.39 Ω µm2 and 4.51 Ω µm2, respectively, while that of B-BOE is 22.8 Ω µm2, as summarized in Table 2. The results indicate that UVO treatment followed by ammonia solution cleaning to remove the oxide layer reduces the contact resistivity by nearly five times compared with BOE cleaning. The oxidation of the InGaAs and InP surfaces by UVO treatment is known not only to remove defective surface layers formed during the processing but also to restore the stoichiometric composition of the semiconductor surface17. Therefore, the lower contact resistivity is likely attributed to the metal deposition performed immediately after sequential UVO oxidation and subsequent oxide removal using an ammonia solution. As shown in Fig. 2 (b-d), the current characteristics of the fabricated UTC-PDs were measured to compare the electrical behavior of each device. Figure 2 (b) reveals two notable differences: an increase in IDark for the UVO-treated devices and a shift in the slope-transition voltage in the IDark–V curves, indicating the crossover voltage (VX). The increase in IDark for the UVO-treated devices is likely attributed to the reduced contact resistivity and lower barrier height. Therefore, the barrier height was extracted from the forward current–voltage (I–V) characteristics, as shown in Fig. 2 (c), using Eq. (2), where ΦB is barrier height, k, T, and q are the Boltzmann constant, absolute temperature, and the electron charge, respectively. And A, A*, and IS denote junction area, Richardson constant, and saturation current. The Richardson’s constant of p-InGaAs is 61.9 A cm− 2 K− 224,25.

The extracted barrier heights for the A-UVO and B-UVO devices are 0.58 eV and 0.59 eV, respectively. These values are slightly lower than that of the B-BOE device (0.61 eV). This reduction is attributed to the restoration of stoichiometry at the p-InGaAs surface by the combined UVO and ammonia cleaning process. In addition, differences in VX among the samples were extracted from the transition points in the slope of the IDark–V curves as shown in Fig. 2 (b). For bias voltages lower than VX, the IDark is dominated by generation-recombination processes, whereas above VX it is mainly governed by tunneling current26. At relatively low voltages, the slopes of the IDark–V curves were nearly identical (~ 0.45) for all devices; however, the BOE-treated device exhibited a slope change at a lower voltage (-2.84 V), suggesting that the cleaning method induces distinct current transport mechanisms. To further clarify the dominant transport mechanism, the thermal activation energy (Ea) was analyzed based on the temperature dependence of the IDark–V curves, which were measured over a temperature range from 308 K to 398 K in 10 K increments. The IDark at a voltage of -1 V was used for comparison. Theoretically, the relationship among IDark, Ea, and T can be expressed as Eq. (3).

Based on this relation, a linear fit of ln(IDark) versus 1000/T was performed, as shown in Fig. 2 (d). Figure 2 (d) shows Ea values of 0.38 eV for UVO and 0.41 eV for BOE at lower temperatures (308 K ≤ T ≤ 348 K), and 0.43 eV for UVO and 0.46 eV for BOE at higher temperatures (358 K ≤ T ≤ 398 K). The obtained Ea values correspond to approximately 50–61% of InGaAs bandgap (0.75 eV); however, the Ea value for the UVO-treated device is slightly lower than that of the BOE-treated one. When Ea ≈ Eg/2, the dominant transport mechanism is the Shockley-Read-Hall (SRH) process, whereas for Ea > Eg/2, the diffusion mechanism also contributes27,28. In this study, the difference in Ea between BOE and UVO (~ 0.03 eV) likely due to the variations in the applied voltage drop by the different interface treatment methods. These DC characteristics indicate that the interface condition has a more significant influence on device performance than the absorber layer structure. To complement the DC analysis and assess the metal-semiconductor interface reliability of the fabricated devices, a bias temperature instability test of UTC-PD was performed at 298 K and 348 K. Figure 3 (a) shows the IDark measured during the stress time. Although the operating voltage is typically around − 1 V, a stress voltage (Vstress) of -7 V was applied to accelerate degradation, enabling the observation of degradation behavior within a short period, as illustrated in Fig. 3 (b). The inset in Fig. 3 (a) presents the bias application scheme for stress and relaxation time. A constant Vstress was applied to the p-metal for 1000 s, followed by a 1000 s relaxation time at 0 V, while the n-metal was grounded during the stress and relaxation times. Under a stress voltage of -7 V applied for 1000 s, the IDark measured at -7 V for the A-UVO and B-BOE was nearly identical, indicating that both devices share the same current transport mechanism under the applied Vstress condition.

The I–V curves were measured during the stress and relaxation time at three points per decade to monitor the variation of the current. Figure 3 (c) shows the change in IDark for the A-UVO (blue symbols) and B-BOE (black symbols) devices during DC bias stress and subsequent relaxation at 298 K (closed circles) and 348 K (opened squares). The IDark at -1 V gradually increases with both stress duration and temperature. During the relaxation phase, the IDark in the B-BOE device partially recovers (decreasing toward its initial value), whereas the IDark in the A-UVO device shows almost no change. For a more detailed comparison, the normalized IDark variation, ΔI/I0 (in percent, at -1 V) was calculated using Eq. (4).

The time dependence of ΔI/I0 during stress and relaxation was fitted using power-law models, \(\Delta I/{I_0}=A \cdot {t^{{n_s}}}\) (stress time) and \(\Delta I/{I_0}=B \cdot {t^{{n_r}}}\) (relaxation time), to extract the time exponent ns and nr. A higher ns indicates a faster degradation process, strongly driven by a high electric field under non-equilibrium condition, involving trap creation and carrier injection in the bulk, at specific interfaces, or within surrounding oxides29. Notably, the ns (~ 0.14) for the A-UVO device is independent of temperature and exhibits negligible recovery during the relaxation time. In contrast, ns for B-BOE shows a distinct temperature dependence. The ns value for B-BOE at 298 K is higher than that at 348 K, which can be explained by partial recovery of trapped charges at relatively lower temperature during voltage sweep (from − 4 V to + 1 V) used to monitor current variations during stress and relaxation30. Meanwhile, during relaxation, the IDark of B-BOE follows an exponent nr (~ 0.04) that remains nearly constant at both temperatures, suggesting that the same recovery mechanism dominates. The observed trends in the time exponents during stress and relaxation indicate that the degradation behavior strongly depends on the interface condition, which is influenced by the metal-semiconductor surface treatment method. Specifically, the recovery behavior observed in the B-BOE device implies the detrapping of trapped charges within the interfacial oxide layer and is consistent with the presence of a residual oxide layer between metal and InGaAs. To further investigate the interface condition, cross-sectional TEM images of devices magnified at Ti (metal)/ InGaAs (p-Ohmic)/ InP (diffusion barrier)/ InGaAs (absorber) stacks were compared, as shown in Fig. 4. The TEM image clearly reveals an ~ 10 nm interfacial oxide layer at the Ti/InGaAs interface in Fig. 4 (a) for the B-BOE device, whereas the A-UVO device exhibits a much thinner oxide layer (~ 2 nm), as shown in Fig. 4 (b). These structural observations strongly support the interpretation that the degradation and recovery behaviors observed in Fig. 3 are primarily governed by the properties of the interfacial oxide layer. While the TEM image alone cannot definitively distinguish whether the interfacial oxide layer is a residual layer or a newly grown one, the experimental conditions support the interpretation that it is a residual layer. Both the B-BOE and A-UVO samples were subjected to metal deposition immediately and simultaneously following their respective surface treatments, and were then annealed at 425 °C for 30 s using RTA. If the ~ 10 nm layer had grown during these subsequent processes, a similar thickness should have been observed in the A-UVO device, where the native oxide was initially removed. Consequently, the substantial thickness difference observed via TEM (~ 10 nm for BOE vs. ~2 nm for UVO) provides clear evidence that the layer in the B-BOE device is a residual layer remaining from insufficient etching rather than a result of subsequent processing. Although the present TEM analysis demonstrates a substantial difference in interfacial oxide thickness between BOE- and UVO-treated devices, a systematic study in which the interfacial oxide thickness is independently controlled, for example through controlled UVO processing, would be beneficial to further distinguish the respective contributions of oxide thickness and interface quality to the observed device behavior.

The frequency and voltage dependence of capacitance were measured, as shown in Fig. 5, to examine the influence of the interfacial oxide layer. The filled and open circles represent the capacitance values of the A-UVO and B-BOE devices, respectively. In Fig. 5 (a), although the undoped InGaAs layer in the absorber of the B-BOE device is thinner, it exhibits a lower capacitance than that of the A-UVO device in the frequency range from approximately 40 kHz to 1 MHz (AC volt = 100 mV). In particular, the capacitance at 100 kHz was reduced by about 8.3%, as shown in Fig. 5 (b), which supports the presence of an interfacial oxide layer.

As expressed in Eq. (5), the total capacitance can be reduced by the contribution of the interfacial oxide capacitance (Cox). Because Cox is inversely proportional to the oxide thickness (tox), it can be expected that the tox of the A-UVO device is thinner–approximately one-third that of B-BOE device–which is consistent with the TEM analysis results. Overall, comparisons of the DC characteristics, instability test, TEM analysis, and capacitance measurements indicate that the interface quality achieved with UVO treatment is superior to that obtained with BOE cleaning due to the presence of a residual interfacial oxide layer in the BOE-treated device.

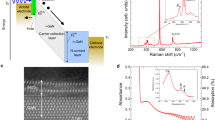

To evaluate the device performance as a photonics component, the photocurrent of devices with various active mesa widths (8 μm - black, 10 μm - red, and 12 μm - blue) and a common mesa length (3.2 μm) was measured, as shown in Fig. 6 (a-c). A lensed fiber was used to couple the incident light into the device through the waveguide. The photocurrent increased linearly with laser power and exhibited a clear dependence on the active area. The responsivity was extracted from the slope of the photocurrent–power curve for etch active mesa width, as shown in Fig. 6 (d), where the black, red, and blue symbols represent the A-UVO, B-UVO, and B-BOE devices, respectively. The responsivity also shows the linear dependence on active mesa width. In the device, a large active mesa area leads to wider depletion region at the junction, which enhances the vertical electric field and promotes the effective separation and collection of photo-generated charge carriers in the depletion region31. Owing to this enhanced charge separation and collection, both the photocurrent and responsivity increase as a function of the active mesa area. The responsivity of the BOE-treated device is higher across all active mesa widths than that of the UVO-treated devices, regardless of the absorber layer configuration. In UTC-PDs, the photocurrent is generated by minority electrons in the absorber layer that flow unidirectionally toward the collector8. Therefore, the reduction of IDark caused by the interface oxide layer on the p-Ohmic side increases the difference between the IDark and photocurrent, leading to an apparent enhancement in responsivity. These findings further demonstrate that the interface condition plays a more dominant role than absorber layer composition in determining the device responsivity. In addition, a performance comparison of PDs including p–i–n PDs, and UTC-PDs with various optical input configurations and absorber materials, is summarized in Table 3. The device presented in this work exhibits competitive performance compared with previously reported PDs.

Finally, to evaluate the high frequency performance, the fabricated UTC-PDs (active mesa area = 8 × 3.2 µm2) with BOE and UVO interface treatments were measured, as shown in Fig. 7 (a), and the corresponding measurement set-up is presented in Fig. 7 (b). A semiconductor-optical-amplifier integrated dual-mode laser (SOA-DML) was employed as a two-tone optical source for photomixing32, together with an erbium-doped fiber amplifier (EDFA) for optical power amplification. The emitted waves were detected using zero-bias detectors (ZBDs) operating in the WR6.5 and WR3.4 bands (Virginia Diodes Inc.), which cover frequency ranges of 100–170 GHz and 220–330 GHz, respectively. As shown in Fig. 7 (a), the measured voltage exhibits a gradual decrease with increasing frequency, representing the typical roll-off behavior of UTC-PD33. Nevertheless, both fabricated devices demonstrated stable operation up to 300 GHz. In particular, the measured voltage of the B-BOE device remained higher than that of the A-UVO device across the entire frequency range. This result is consistent with the responsivity trend observed in the photocurrent measurements, confirming that the B-BOE device exhibits better performance than the A-UVO. These findings suggest that the interfacial oxide layer, which suppresses IDark, is beneficial for improving UTC-PD performance. Although UVO treatment produces a cleaner metal-semiconductor interface and reduces contact resistance, it simultaneously increases IDark, leading to degraded responsivity and frequency response. Therefore, developing a high-quality interfacial oxide layer that effectively suppresses IDark after UVO surface treatment is essential for further enhancing UTC-PD performance.

Conclusion

The effects of the InGaAs absorber structure and metal-semiconductor interface cleaning process on UTC-PD performance were systematically evaluated. Although UVO treatment reduced contact resistance and barrier height by improving interface quality, it also led to an increase in IDark and a consequent reduction in photoresponsivity, regardless of the absorber configuration. In contrast, BOE-treated devices exhibited superior photoresponsivity and frequency characteristics. These results confirm that interface treatment plays a more dominant role than absorber structural modification in determining overall device performance. Therefore, optimizing the interface condition while maintaining a high-quality interfacial oxide layer is crucial for achieving enhanced UTC-PD performance.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Kato, K. Ultrawide-band/high-frequency photodetectors. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 47, 1265–1281 (1999).

Cox, C. H., Ackerman, E. I., Betts, G. E. & Prince, J. L. Limits on the performance of RF-over-fiber links and their impact on device design. IEEE Trans. Microwave Theory Tech. 54, 906–920 (2006).

Nellen, S. et al. Photonic-enabled beam steering at 300 GHz using a photodiode-based antenna array and a polymer-based optical phased array. Opt. Express OE. 30, 44701–44716 (2022).

Baek, I. H. et al. Experimental characterization of photodiode transmitters for probabilistically shaped High-Speed THz wireless transmission. J. Lightwave Technol. 2025, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1109/JLT.2025.3596696 (2025).

Williams, K. J. & Esman, R. D. Design considerations for high-current photodetectors. J. Lightwave Technol. 17, 1443–1454 (1999).

Williams, K. J., Esman, R. D. & Dagenais, M. Effects of high space-charge fields on the response of microwave photodetectors. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 6, 639–641 (1994).

Ishibashi, T. et al. Uni-traveling-carrier photodiodes. In Ultrafast Electronics and Optoelectronics 83 (Optica Publishing Group, 1997). https://doi.org/10.1364/UEO.1997.UC3.

Ishibashi, T. & Ito, H. Uni-traveling-carrier photodiodes. J. Appl. Phys. 127, 031101 (2020).

Ito, H. et al. High-speed and high-output InP-InGaAs unitraveling-carrier photodiodes. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 10, 709–727 (2004).

Ishibashi, T., Muramoto, Y., Yoshimatsu, T. & Ito, H. Unitraveling-Carrier photodiodes for Terahertz applications. IEEE J. Select Top. Quantum Electron. 20, 79–88 (2014).

Zhou, G. et al. High-Power InP-Based waveguide integrated modified Uni-Traveling-Carrier photodiodes. J. Lightwave Technol. 35, 717–721 (2017).

Dyson, A., Henning, I. D. & Adams, M. J. Comparison of type I and type II heterojunction unitravelling carrier photodiodes for Terahertz generation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 14, 277–283 (2008).

Shi, J. W., Wu, Y. S., Wu, C. Y., Chiu, P. H. & Hong, C. C. High-speed, high-responsivity, and high-power performance of near-ballistic uni-traveling-carrier photodiode at 1.55-µm wavelength. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 17, 1929–1931 (2005).

Shi, M., Shao, X., Tang, H., Li, X. & Gong, H. Improved interface and dark current properties of InGaAs photodiodes by high-density N2 plasma and stoichiometric Si3N4 passivation. Infrared Phys. Technol. 122, 104084 (2022).

Tran, H. C. V. et al. Enhanced SWIR photodetection in colloidal quantum Dot photodiodes via tunneling current suppression. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 17, 15666–15674 (2025).

Wang, Y. et al. Sulfur-enhanced surface passivation for hole-selective contacts in crystalline silicon solar cells. Cell. Rep. Phys. Sci. 5, 102199 (2024).

Driad, R. et al. Surface passivation of InGaAs/InP beterostructures using UV-irradiation and ozone. In Conference Proceedings. 1998 International Conference on Indium Phosphide and Related Materials (Cat. No.98CH36129) 459–462 (IEEE, 1998). https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIPRM.1998.712523.

Crook, A. M. et al. Low resistance, nonalloyed ohmic contacts to InGaAs. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 192114 (2007).

Demiguel, S. et al. Very high-responsivity evanescently coupled photodiodes integrating a short planar multimode waveguide for high-speed applications. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 15, 1761–1763 (2003).

Xia, F. et al. An asymmetric twin-waveguide high-bandwidth photodiode using a lateral taper coupler. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 13, 845–847 (2001).

Kato, K., Hata, S., Kawano, K., Yoshida, J. & Kozen, A. A high-efficiency 50 ghz InGaAs multimode waveguide photodetector. IEE J. Quantum Electron. 28, 2728–2735 (1992).

Demiguel, S. et al. Evanescently coupled photodiodes integrating a double-stage taper for 40-Gb/s applications-compared performance with side-illuminated photodiodes. J. Lightwave Technol. 20, 2004–2014 (2002).

Kang, S. C., Cho, J. C., Shin, J. H., Park, D. W. & Lee, E. S. New insights into I-line stepper based InGaAs/InP double-heterojunction bipolar transistors (DHBTs). Mater. Sci. Semiconduct. Process. 201, 110076 (2026).

Veteran, J. L., Mullin, D. P. & Elder, D. I. Schottky barrier measurements on p-type In0.53Ga0.47As. Thin Solid Films. 97, 187–190 (1982).

Maeda, T. et al. Schottky barrier contact on In0.53Ga0.47As with short-wave infrared transparent conductive oxide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 232102 (2022).

Jang, J. H. et al. Long-wavelength In0.53Ga0.47As metamorphic p-i-n photodiodes on GaAs substrates. IEEE Photon Technol. Lett. 13, 151–153 (2001).

Chen, H. et al. Dark current analysis in high-speed germanium p-i-n waveguide photodetectors. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 213105 (2016).

Sy, F. et al. Reliability characterization and modeling of high speed ge photodetectors. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Relib. 19, 688–695 (2019).

Musibau, S. et al. Degradation and recovery kinetics study of vertical and lateral Ge-on-Si photodetectors. In IEEE International Reliability Physics Symposium (IRPS) 1–10 (IEEE, 2024). https://doi.org/10.1109/IRPS48228.2024.10529439.

Palumbo, F. et al. Temperature dependence of trapping effects in metal gates/Al2O3/InGaAs stacks. Solid State Electron. 132, 12–18 (2017).

Fidan, M., Ünverdi, Ö. & Çelebi, C. Junction area dependent performance of graphene/silicon based self-powered Schottky photodiodes. Sens. Actuators A: Phys. 331, 112829 (2021).

Lee, E. S. et al. SOA-Integrated Dual-Mode laser and a PIN-Photodiode for compact CW Terahertz system. ETRI J. https://doi.org/10.4218/etrij.16.0115.0882 (2016).

Nellen, S. et al. Experimental comparison of UTC- and PIN-Photodiodes for Continuous-Wave Terahertz generation. J. Infrared Milli Terahz Waves. 41, 343–354 (2020).

Li, C. et al. High-responsivity vertical-illumination Si/Ge uni-traveling-carrier photodiodes based on silicon-on-insulator substrate. Sci. Rep. 6, 27743 (2016).

Arabhavi, A. M. et al. Type-II GaInAsSb/InP uniform absorber high speed Uni-Traveling carrier photodiodes. J. Lightwave Technol. 39, 2171–2176 (2021).

Li, N. et al. High-saturation-current charge-compensated InGaAs–InP uni-traveling-carrier photodiode. IEEE Photon Technol. Lett. 16, 864–866 (2004).

Sun, M. et al. Ultrafast evanescently coupled waveguide MUTC-PDs with high responsivity. Opt. Express. 32, 16455 (2024).

Rouvalis, E. et al. 170 ghz uni-traveling carrier photodiodes for InP-based photonic integrated circuits. Opt. Express. 20, 20090 (2012).

Ye, H. et al. High speed evanescent waveguide photodetector with a 100 ghz bandwidth. Appl. Phys. Express. 17, 012001 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Nano & Material Technology Development Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (RS-2024-00411969), in part by the Electronics and Telecommunication Research Institute (ETRI) grant funded by the Korean government (25ZB1300).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C.K. and J.C.C. contributed equally: conceptualization, fabrication, investigation, methodology, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. E.S.L.: conceptualization, methodology, resources, writing—review and editing, and funding. D.W.P.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing, and funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, S.C., Cho, J.C., Lee, E.S. et al. Influence of metal–semiconductor interface treatments and absorber structure on the performance and reliability of uni-traveling-carrier photodiodes (UTC-PDs). Sci Rep 16, 4749 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34935-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34935-y