Abstract

This study investigates the broadband noise generated by an aircraft steering control valve assembly during steering maneuvers. A nonlinear spool dynamics model, incorporating coupled steady-state and transient fluid forces, is established and validated through AMESim simulations and experimental test. Through this model, the critical influence between the return orifice size and the stability of cone-type poppet valve is revealed. The results demonstrate that spool stability is significantly enhanced by optimally matching the dimensions of the return and inlet orifices, which leads to an effective reduction in pressure fluctuations and vibration-induced noise. Bench tests of the optimized configuration show that the overall sound pressure level (OSPL) is reduced by more than 10 dB(A). Furthermore, on-aircraft tests confirm a peak noise reduction exceeding 20 dB(A) within the 200–800 Hz frequency band. This research offers novel insights into optimizing cone-type poppet valve stability and provides a practical engineering solution for achieving “Silent Cockpit” noise control in civil aircraft.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background

The advent of the “Silent Cockpit” concept in civil aviation1 has placed a premium on the design of hydraulic components that balance high efficiency with low-noise characteristics. The nose wheel steering system, a critical system for aircraft ground directional control, is essential for mitigating the risk of runway excursions. According to ASN statistics, runway excursions accounted for 117 of 720 total aviation accidents between 2017 and 2022, representing 16.25% of all incidents2 . As a core hydraulic element in the system, the steering control valve assembly catches particular attention to its acoustic performance. Due to its proximity to the cockpit, noise originating from fluid dynamics and mechanical vibration is readily transmitted into this area, potentially compromising pilot comfort and thus necessitating stringent noise control measures.

Modern mainstream civil aircraft typically employ fly-by-wire, hydraulically actuated nose wheel steering systems. Steering inputs are provided by the pilot via a handwheel and rudder pedals. The system’s control unit processes feedback signals from steering angle sensors to generate electrical commands. These commands actuate the control valve, which in turn modulates the hydraulic flow and pressure delivered to the steering actuator. This mechanism ultimately achieves closed-loop position control of the nose wheel3.

As depicted in the hydraulic schematic in ‘Fig. 1’, a typical aircraft nose wheel steering system is composed of several key components: an oil filter, a check valve, a bypass valve, a solenoid valve, an electro-hydraulic servo valve, a shimmy damper valve, an anti-cavitation valve, a relief valve, a compensator with cone-type poppet valve, and a steering actuator.

During normal operation, system pressure is supplied through the solenoid-controlled bypass valve, while the electro-hydraulic servo valve is utilized for actuator position control. In a failure scenario (i.e., shimmy damping mode), the compensator supplies hydraulic fluid to the actuator’s low-pressure chamber via the anti-cavitation valve to prevent cavitation. Should excessive external loads be applied to the nose wheel, the relief valve promptly releases pressure from both actuator chambers, thereby protecting the system from overload.

Abnormal noise was observed from the steering valve assembly of a specific aircraft model during steering maneuvers. Subsequent analysis identified the source of this noise as a direct-acting, cone-type poppet valve located within the compensator section.

Research status

The stability of a cone-type poppet valve is governed by multiple factors, including its internal structural parameters, external excitations, and the inherently low damping of the hydraulic system. Consequently, enhancing valve stability and suppressing the associated noise remain critical technical challenges. This subject therefore constitutes a significant and ongoing area of research within the field of hydraulics4.

Liu Xiaohong et al.5 employed CFD technology to analyze the velocity and pressure fields of oil in flow channels, revealing the influence of channel configuration and structural parameters on pressure loss and hydrodynamic forces in hydraulic integrated valve blocks. By optimizing relevant flow channel parameters, they reduced pressure loss as well as vibration and noise in hydraulic integrated valve blocks, offering a new approach for noise reduction in valve assemblies.

Rongsheng Liu et al.6 addressed the prevalent issue of excessive pure-tone noise in pressure-reducing valves. Through computational fluid dynamics simulations, the paper elucidated the correlation between flow field characteristics and noise generation. A comprehensive analysis was conducted on the position, quantity, and diameter of the spool oil holes. Finally, noise experiments verified the accuracy of the simulation model, providing guidance for noise reduction design and improvement of direct-operated pressure-reducing valves.

Yao Jing et al.7 investigated the problems of cavitation and spool vibration inside pressure poppet valves in aviation hydraulic systems. Using Detached Eddy Simulation (DES) and visualization experiments, the paper demonstrated that cavitation within the valve is induced by circumferential vortex rings formed by the interaction between the valve orifice jet and wall constraints. Moreover, an increase in the pressure differential across the valve orifice intensifies flow field pulsations, thereby providing a theoretical basis for understanding the causes of spool vibration in aviation poppet valves.

Liu et al.8 established a nonlinear dynamic model employing a segmented, lumped-parameter approach to analyze the flutter phenomenon in a cryogenic oxygen poppet valve. Numerical simulations successfully reproduced limit cycle oscillations under specific conditions, revealing that the system was locally stable but globally unstable. It was also found that the frequency of self-excited oscillations decreased as the pressure difference increased. Flow augmentation was ultimately proposed as a method for oscillation suppression.

Chabane et al.9 developed a coupled 1D method integrating thermodynamics, wave propagation, and CFD-corrected fluid load models to address chatter in conventional safety valves under backpressure. Experimental results validated that chatter intensity increases when backpressure exceeds 10% of the set pressure. The study showed that optimizing the connecting piping is an effective way to suppress such chatter.

Jie10 established a reduced-order fluid excitation model to analyze flow-induced vibration in spring-loaded pressure regulators under low-load conditions. Instability occurred primarily at low flow rates due to negative damping from transient fluid excitation. Vibration was suppressed by increasing bypass outlet length and reducing spring pre-compression.

Research Gap: A notable gap in the existing literature is that the impact of return orifice damping on spool stability has been largely overlooked11. To address this gap, the present study systematically investigates the stability control mechanism associated with return throttle damping in direct-acting poppet valves. This is achieved through a combination of theoretical modeling, AMESim simulation, and experimental validation. The results confirm that optimizing the return throttle parameters significantly enhances valve stability and reduces noise, thereby providing a novel technical pathway for improving the performance of such components.

Mathematical modeling

System description and functional principles

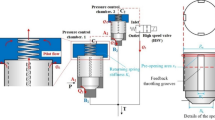

The component under investigation is a direct-acting, cone-type poppet valve located within the compensator section of the aircraft’s nose wheel steering system. As depicted in Fig. 2, this valve is composed of three primary components: a spool, a spring, and a valve seat. Unlike conventional throttle valves, it is characterized by an internal flow path design that incorporates four return orifices at the rear of the spool.

Functionally, this assembly operates as a classical "mass-spring" system. The spool acts as the mass, and the spring provides the restoring force. In a hydraulic environment, such a system is inherently characterized by low mechanical damping. Consequently, during operation, the spool is highly susceptible to fluid-dynamic forces that can induce oscillations, a phenomenon known as flow-induced vibration12. Such vibration can, in turn, lead to several adverse effects, including the generation of acoustic noise, significant pressure fluctuations within the hydraulic system, and the potential for long-term structural fatigue damage. The focus of this study is the unique role of the four return orifices, which can be engineered to provide a significant source of hydraulic damping, thereby stabilizing the spool’s motion.

Fluid dynamics equations

Based on the continuity equation13, the upstream chamber pressure dynamics are described by:

where:

\(\rho\): Fluid density, kg/m3;

\({V}_{1}\): Upstream chamber volume, m3;

\({Q}_{in}\): Inlet flow rate, L/min;

\({Q}_{out}(x,{p}_{1})\): Outlet flow rate, L/min;

Assuming incompressible flow, the pressure rise rate is given by:

where:

\({P}_{1}\): Inlet pressure, Pa;

\({E}_{1}\): The volume elastic modulus of the pressure chamber at \({V}_{1}\), Pa;

The outlet flow rate through the valve opening is:

where:

\({C}_{d}\):Flow coefficient, dimensionless;

\(A(x)\): Effective flow area at valve opening, m2;

\(\Delta P\): Pressure difference across the valve port, Pa;

The flow area \(A(x)\) is a function of spool displacement \(x\):

Substituting (4) into (3):

Combining (1), (2), and (5), the upstream pressure dynamics can be expressed as:

For the spool top region, the pressure dynamics are similarly described:

where:

\({V}_{2}\): Volume of the space formed between the conical top of the poppet valve and the valve seat. This volume is related to the spool displacement, but \({V}_{2}\) is very small;

\({E}_{2}\): The volume elastic modulus of the pressure chamber at \({V}_{2}\), Pa;

\({Q}_{in}(x,{p}_{1})\): Flow rate into the space volume formed between the conical top of the poppet valve and the valve seat,\({Q}_{in}\left(x,{p}_{1}\right)={Q}_{out}(x,{p}_{1}\));

\({Q}_{out}(x,{p}_{2})\): The flow rate out of the top region of the poppet valve.

Neglecting internal leakage in the poppet valve, according to the thin-walled orifice flow formula:

where:

\({C}_{c}\): Flow coefficient for the thin-walled orifice;

\(A\): Total area of the four orifices, m2;

Similarly, for the downstream side of the poppet valve return port:

Where:

\({P}_{3}\): Poppet valve outlet pressure, Pa;

\({E}_{3}\): Bulk modulus of the fluid in the outlet chamber of the poppet valve, Pa;

\({Q}_{in}\left(x,{p}_{2}\right)\): Flow rate into the return chamber of the poppet valve, where \({Q}_{in}\left(x,{p}_{2}\right)={Q}_{out}\left(x,{p}_{2}\right)\);

\({V}_{3}\): Volume of the outlet chamber of the poppet valve, including the return line volume, m3;

From Eq. (9), it can be seen that increasing the volume \({V}_{3}\) can reduce fluctuations in the return pressure \({p}_{3}\) caused by flow rate variations.

For the return pressure \({p}_{3}\), it is primarily generated by frictional losses. Assuming the tank pressure at the end of the return line is 0, the pressure drop can be calculated using the formula for frictional losses in a long circular pipe:

where:

\(d\): Equivalent diameter of the return line, m;

\(l\): Equivalent length of the return line, m;

\(u\): Dynamic viscosity of the fluid, N·s/m2 (Pa·s).

Performing Laplace transform on Eqs. (1) to (10) yields:

Since \({v}_{2}\ll {v}_{1}\), \({v}_{2}\ll {v}_{3}\), and because the compensator pressure \({p}_{3}\) is typically only around 0.5 MPa, the variation of the fluid bulk modulus due to pressure can be neglected, i.e., \({E}_{1}\approx {E}_{2}\approx {E}_{3}=E\). Therefore, the above Eq. (11) can be simplified to:

Spool dynamics

The spool is subject to hydraulic, spring, friction, inertial, and fluid dynamic forces.

Spring force:

The spring force acting on the spool mainly consists of the force due to initial preload and the force generated by the spool’s motion. It can be expressed as:

where:

\({F}_{spring}\): Spring force acting on the valve poppet, N;

\(K\): Spring stiffness, N/m;

\({x}_{0}\): Initial spring compression (preload), m;

\(x\): Valve opening position (spool displacement), m.

Friction force

The friction force acting on the spool primarily includes Coulomb friction (also known as static friction) caused by friction and viscous friction caused by motion14. Its expression can be written as:

where:

\({F}_{friction}(x)\): Total friction force, N;

\({F}_{f}\): Coulomb friction force, N;

\({F}_{h}\): Viscous friction force in the conical region of the spool, N;

\({F}_{Z}\): Viscous friction force in the cylindrical region of the spool, N;

\({u}_{1}\): Coulomb friction coefficient, dimensionless;

\({F}_{N}\): Normal contact force between the spool and the sleeve, N;

\(Sgn\): Signum function, related to the direction of motion, taking values of + 1 or −1;

\({u}_{v}\): Fluid dynamic viscosity coefficient, m2/s;

\({d}_{3}\): Spool diameter, mm;

\({L}_{1}\): Overlap length between the poppet cone angle and the valve seat, mm;

\(\alpha\): Half-angle of the poppet cone, (°);

\(h(x)\): Axial clearance between the spool cone and the valve seat (function of x), mm;

\({L}_{2}\): Overlap length in the cylindrical section between the spool and the valve seat, mm;

\(h\): Radial clearance between the spool cylindrical section and the valve seat, typically around 5–7 µm;

\(\dot{x}\): Spool velocity, m/s.

The term \({u}_{1}{F}_{N}Sgn\left(\dot{x}\right)\) in the above equation represents the Coulomb friction force. Its magnitude is mainly influenced by the surface roughness of the spool and sleeve. Since the machining precision of spools and sleeves is usually high, and hydraulic oil provides lubrication, this value is small and can often be neglected in dynamic characteristic studies.

The viscous friction force \(h(x)\) in the conical region of the spool is inversely proportional to the displacement-dependent parameter \(h(x)\). Therefore, after the valve opens,\(h(x)\gg h\). The clearance formed between the conical surface of the spool and the conical surface of the seat increases, weakening the fluid shear effect. Consequently, the viscous friction force generated by fluid motion rapidly decreases. In the study of the valve element’s dynamic characteristics, the viscous friction in the annular conical region of the poppet valve can be neglected, retaining only the viscous friction between the cylindrical section and the valve seat.

Since the overlap length \({L}_{2}\) in the cylindrical section between the spool and the valve seat and the radial clearance \(h\) between the spool cylindrical section and the valve seat are both constants, the viscous friction force \({F}_{Z}\) in the cylindrical region of the spool is proportional to the spool velocity \(\dot{x}\).

Spool gravity and inertial force

Based on force analysis, the spool inertial force can be expressed as:

where:

\({F}_{g}\): Mass force, N;

\(m\): Total mass of the spool plus one-third of the spring mass, kg;

\(g\): Gravitational acceleration,9.8 m/s2;

\(\ddot{x}\): Spool acceleration, m/s2;

In the spool dynamic studies, the spool’s gravitational force component \(mg\) is typically neglected due to the small mass of the spool. However, for high-frequency response valves, the acceleration term \(m\ddot{x}\) significantly impacts the dynamic characteristics and must be considered.

Flow forces

Flow forces acting on the spool primarily consist of two components: steady-state flow force and transient flow force.

Steady-state flow force arises when the spool is held at a fixed opening. It results from the change in fluid momentum as oil flows through the valve orifice and acts on the spool. This force can be resolved into axial and radial components.

Transient flow force is an additional force generated by the change in fluid momentum within the flow passages due to spool movement. Its direction opposes the spool’s velocity vector, effectively simulating a damping force. This force becomes particularly significant during rapid spool motion.

Research indicates that flow forces directly influence critical valve performance metrics, including stability, response speed, and vibration/noise levels.

Steady-state flow force

The flow force significantly impacts valve performance and is one of the most critical forces affecting valve stability. The radial hydraulic forces acting circumferentially on the spool balance each other, while the axial component is the primary flow force affecting poppet valve performance15.According to the momentum theorem, for the axial direction, the impulse \(\dot{I}\) imparted by external forces on the fluid over a time interval \(\Delta t\) equals the change in fluid momentum:

where:

\(\dot{I}\):The impulse exerted on the fluid by external forces;

Selecting the poppet inlet cross-section A1 and the cross-section A2 of the enclosed space between the poppet and seat (where fluid velocities are \({v}_{1}\) and \({v}_{2}\) respectively), the momentum change for the inflow rate \({Q}_{in}\) is:

\(\rho\): Fluid density, kg/m3;

The axial external force \({F}_{1}\) acting on the fluid (downward direction) equals the change in axial fluid momentum:

Eliminating \(\Delta t\) gives:

Furthermore, for steady flow,

Combining Eqs. (20), (21), and (22) yields:

Similarly, considering the control surfaces defined by cross-section \({A}_{2}\) (enclosed space) and the four orifice cross-sections \({A}_{3}\) on the poppet spool (fluid velocities \({v}_{2}\) and \({v}_{3}\), respectively), the momentum theorem gives the external force \({F}_{2}\) (downward direction) as:

According to Newton’s third law, the force exerted by the spool on the fluid equals the reaction force exerted by the fluid on the spool. Therefore, the total flow force \({F}_{F}\) acting on the spool is

Simplifying Eq. (25) gives:

When \(\frac{1}{{A}_{1}}\)>\(\frac{\mathit{sin}\alpha }{{A}_{3}}\) , he steady-state flow force \({F}_{F}\) is positive (upward), acting to close the valve orifice. This represents a negative feedback force;

When \(\frac{1}{{A}_{1}}\)<\(\frac{\mathit{sin}\alpha }{{A}_{3}}\) , the steady-state flow force \({F}_{F}\) is negative, acting to open the valve orifice. This represents a positive feedback force.

When \(\frac{1}{{A}_{1}}\) =\(\frac{\mathit{sin}\alpha }{{A}_{3}}\) , the steady-state flow force \({F}_{F}\) is zero.

At small valve openings, the poppet tip acts as the primary restriction. The relationship between flow rate \({Q}_{in}\) and poppet displacement \(x\) is:

where:

\({C}_{d}\): Discharge coefficient, dimensionless;

\(A(x)\): Effective flow area at displacement,m2;

\(\Delta P\): Pressure drop across the valve orifice, Pa;

The steady-state flow force is then:

Transient flow force

The transient flow force primarily arises from the dynamic force generated by the abrupt change in fluid momentum under unsteady operating conditions (such as rapid valve opening/closing or sudden flow rate changes). Its mechanism manifests as a force opposing the spool movement, thereby exhibiting a significant damping effect. The transient flow force for a poppet valve can be expressed as16:

Since:

Combining Eq. (31) with Eq. (32) yields:

where:

\({F}_{s}\): Transient flow force, N;

\({d}_{1}\): Valve seat orifice diameter, m;

\(L\): Equivalent flow path length of fluid within the valve chamber,m;

The direction of the transient flow force \({F}_{s}\) is opposite to the direction of the flow rate change \(\frac{d{Q}_{in}}{dt}\). Consequently:

When the valve opening is accelerating open( \(\dot{x}\) > 0, \(\frac{d{Q}_{in}}{dt}\) > 0), the transient flow force acts to close the valve port.

When the valve opening is accelerating closed (\(\dot{x}<0\), \(\frac{d{Q}_{in}}{dt}<0\)), the transient flow force acts to oppose the closing (inhibits closure) of the valve port.

Poppet spool dynamic equation

During its motion, the poppet spool is subjected to the combined action of hydraulic pressure, gravity, inertial force, spring force, friction force, and flow-induced force. Its dynamic equilibrium equation can be expressed as:

where \({F}_{P}\) is the hydraulic force, which can be expressed as:

Combining Eqs. (13), (14), (15), (26), (30), (33), (34), and (35), and when the valve orifice opening is small, flow throttling occurs primarily at the tapered section of the poppet. Neglecting the relatively small gravitational term \(mg\), the Coulomb friction term \({\mu }_{1}{F}_{N}Sgn\left(\dot{x}\right)\), and the viscous friction term \(\frac{{u}_{v}\pi {d}_{3}{L}_{1}}{\mathit{sin}\alpha }\frac{\dot{x}}{h(x)}\), the equation simplifies to:

System simplification and stability analysis

Since the return oil volume \({V}_{3}\) is typically very large, pressure \({p}_{3}\) is relatively stable according to Eq. (9). Applying the incremental Laplace transform to Eq. (36) and transforming it into the standard second-order form yields (Derivation process please find the Appendix), the equation simplifies to:

where Static Gain: \({K}_{S}=\frac{{A}_{1}}{{K}_{2}}\);

Undamped Natural Frequency: \(\omega =\sqrt{\frac{{K}_{2}}{m}}\);

Damping Ratio:\(\xi =\frac{{c}_{t}}{2\sqrt{m{K}_{2}}}\);

And \({K}_{1}\approx {A}_{1}\);

The necessary and sufficient conditions for the stability of this second-order system are: \(\xi >0\) and \({K}_{2}>0;\)

Since \(K,X\) and \({\Delta P}_{12}{\Delta P}_{12}\) are all positive, the stability requirement becomes:

Since \(-\frac{K}{2X{\Delta P}_{12}}<0\), So substituting the expression for C:

For this inequality to hold (particularly ensuring the left side can be negative but bounded below), it follows that:

Additionally, poppet valve mass-spring systems are typically underdamped. Enhancing system stability can be achieved by appropriately increasing the damping ratio \(\xi\). This can be done either by increasing the numerator \({c}_{t}\) or decreasing the denominator \(2\sqrt{m{K}_{2}}\).

Reducing \(2\sqrt{m{K}_{2}}\) can be accomplished by Decreasing the spool mass m or Decreasing \({K}_{2}\).

Since \(K>0\), this implies making:

which again requires:

Key stability conclusions:

\({A}_{3}<{A}_{1}*\mathit{sin}\alpha\) Is a necessary condition for system stability derived above, and moderate reduction of \({A}_{3}\) enhances system stability. But \({A}_{3}\) cannot be made excessively smaller than \({A}_{1}*\mathit{sin}\alpha\), as this could drive \({K}_{2}\) < 0, leading to instability.

Increasing \({c}_{t}\) can be achieved by enlarging \({c}_{t}=\frac{{u}_{v}\pi {d}_{3}{L}_{2}}{h}+\frac{L\rho Q}{X}\) Practical methods include:

Increasing diameters \({d}_{3}\), lengths (\({L}_{2}\), L).

Decreasing the radial clearance (\(h\)).

Restricting the spool displacement stroke (\(X\)).

Dynamic simulation analysis based on AMESim

An AMESim model of the steering control system was established as shown in Fig. 3. Stability impact analysis was conducted on key parameters of the poppet valve (such as return flow orifice diameter, maximum valve opening, etc. The main simulation parameters are listed in Table 1.

Analysis of simulation results is as follows:

With flow rate set at 7 L/min and jet force coefficient parameterized at 0.5, the maximum allowable poppet piston was constrained at 1 mm. Simulations were conducted for four cases of equivalent damping orifice diameter (1.8 mm, 2.0 mm, 2.2 mm, 2.5 mm). The resulting stability behaviour of the poppet valve is shown in Fig. 4.

As shown in Fig. 4, the poppet valves with damping orifice diameters of 2.0 mm, 2.2 mm, and 2.5 mm exhibit significant pressure fluctuations at the spool tip, whereas the valve with a 1.8 mm damping orifice demonstrates relatively stable spool pressure, that means with the decrease dimension of the orifice, the stability enhanced, this result matches with the analysis in chapter 2.

Experiments

Laboratory test

To experimentally validate the theoretical and simulation findings, a series of laboratory and on-aircraft tests were performed at environmental temperature. For the laboratory portion, a dedicated test rig was constructed to measure the acoustic and vibrational performance of the valve assembly under controlled conditions. The schematic and a photograph of the experimental setup are presented in Fig. 5, and four different dimension (1.8 mm, 2.0 mm, 2.2 mm,2.5 mm) return orifice valve pistons were tested in the test.

The test rig consists of a hydraulic power unit, the steering control valve assembly under test, and a comprehensive data acquisition system. To ensure the credibility and reproducibility of the experimental measurements, 2 high-precision sensors were employed and set about 10 cm far away from the return pipe). The key components and their specifications are detailed in Fig. 6. Valve assemblies with the four different return orifice sizes (1.8 mm, 2.0 mm, 2.2 mm, and 2.5 mm) were fabricated for comparative testing.

To evaluate performance of valves with different restrictor sizes, noise measurements were conducted under multiple flow conditions and command signal profiles. Specific test procedures were:

-

1.

Background noise measurement: Recorded ambient noise with steering control valve deactivated under pump-only condition.

-

2.

Steady-flow noise test: Applied constant current commands to the proportional servo valve (−8 mA to 8 mA in 1 mA increments) to establish stable flows through the test valve while measuring noise levels.

-

3.

Ddynamics-flow noise test: Generated flow transients via ramp commands (1 mA/s, 2 mA/s, 4 mA/s) and step commands (0 mA → 8 mA) to the proportional servo valve while acquiring noise data.

Experimental results

Laboratory bench test results

Under the procedures showed in 4.1, test was performed for 3 times on the bench as Fig. 5, the noise test result is similar each time. The data collected from the laboratory tests confirmed a strong correlation between the return orifice size and the generated noise. As shown in Fig. 6, overall sound pressure levels (OASPL) for different return orifice sizes demonstrate a general decreasing trend with reduced orifice diameter. This indicates that smaller return orifices enhance poppet stability, consequently mitigating flow-induced noise.

On aircraft test results

To validate the noise suppression performance of the optimized design under operational steering conditions, on-aircraft tests were conducted on a real aircraft. During these tests, acoustic sensors were positioned at ear level at both the captain’s and first officer’s stations within the cockpit. Comparative noise measurements were performed during closed-loop steering control to evaluate two different valve configurations: A baseline valve equipped with a 2.5 mm diameter return orifice and the optimized valve featuring a 1.8 mm diameter return orifice.

As depicted in Fig. 7, the valve with the 1.8 mm restrictor shows a significant reduction in noise across the 100–1000 Hz frequency band compared to the 2.5 mm baseline configuration. This reduction is particularly pronounced within the critical 200–800 Hz band, where peak sound pressure levels are attenuated by more than 20 dB(A).These experimental results conclusively validate the hypothesis that reducing return orifice diameter enhances poppet valve stability, thereby suppressing flow-excited structural–acoustic coupling phenomena.

Analysis and discussion

The present study systematically demonstrates that reducing the return-flow orifice diameter significantly enhances the stability of cone-type poppet valves and effectively suppresses flow-induced vibration and noise. Both simulation and experimental results consistently support the core hypothesis: a smaller return orifice increases damping effects, thereby improving valve dynamic stability.

The mathematical model reveals that the stability of the valve core is highly sensitive to the return orifice size. A reduced orifice diameter increases back pressure in the return chamber, which enhances damping and suppresses self-excited oscillations. The AMESim simulations further confirmed that an orifice diameter below a critical value (e.g., 1.8 mm under the given conditions) prevents oscillatory behavior and ensures stable operation.

Experimental validation, including both bench tests and on-aircraft ground tests, strongly verified the theoretical and simulation findings. The laboratory tests showed a reduction of over 10 dB in overall sound pressure levels after optimizing the orifice size. on-aircraft tests further demonstrated a remarkable noise reduction of more than 20 dB(A) in the 200–800 Hz frequency band during steering maneuvers.

Compared to the noise reduction methods presented in [5,6,7,8,9,10], this study introduces innovations in noise reduction techniques. Specifically, the former mentioned literature has not investigated the influence of the return orifice on poppet valve stability. Furthermore, the proposed approach demonstrates significant advantages in terms of noise reduction effectiveness and the trade-off associated with weight increasing.

These findings underline the importance of considering return-flow damping in the design of high-performance aviation hydraulic valves. The proposed solution is not only effective, but also practical, as it requires minimal structural modification yet offers significant noise reduction, contributing directly to quieter cockpit environments. Future work could explore the interaction between orifice size and cone-type poppet valve’s other geometric parameters under varying operating conditions.

Conclusions

This study established a dynamic model of the poppet valve poppet, systematically investigating the influence mechanism of return orifice diameter on valve stability. Through optimized parameterization of AMESim simulations, the predictive accuracy was significantly enhanced, providing a theoretical foundation for stability-optimized design.

Based on theoretical and simulation analyses, comparative experimental validation was conducted with varying return orifice sizes. By implementing a hybrid test protocol that combines steady and transient flow conditions, the efficacy of the return orifice in enhancing poppet stability and attenuating flow-induced noise was conclusively demonstrated.

On-aircraft ground test validation under closed-loop steering control confirmed the practical effectiveness of the optimized design. A cockpit noise reduction of more than 20 dB(A) was achieved under representative operational conditions, validating the proposed solution’s applicability for noise control in civil aircraft. These results validate the effectiveness in closed-loop hydraulic systems and demonstrate robust adaptability under real-world conditions.

Collectively, this research integrates theoretical modeling, high-fidelity simulation, and multi-tiered experimental validation to establish a comprehensive technical framework for stabilizing complex poppet valves. The key scientific contributions include revealing the governing mechanism of restrictor diameter on valve stability, proposing a novel fluid-stability control paradigm, and delivering an engineered solution for poppet instability and noise mitigation.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from our industrial partner (Nanjing Electromechanical Hydraulic Co.,Ltd),but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of our industrial partner (Nanjing Electromechanical Hydraulic Co.,Ltd).

References

YANG Wen. Research on Commercial Aircraft Control Panel Based on Quiet Dark Cockpit [D]. Fudan University, 2013(in Chinese).

Wenjie, C. H. E. N. Study on the test and adjustment method of civil aircraft taxiing deviation [J]. Aerospace 11 (9), 732 (2024).

Xin, L. I., Xuebin, D. I. N. G. & Zijin, W. A. N. G. Design Technology and Research of Fly-by-Wire Steering System Control Law [C]// Proceedings of the 16th China Aviation Measurement and Control Technology Annual Conference, : 387–391 + 414. (2019).

Wanrong, W. U. CFD-based cavitation research and structure optimization of relief valve for noise reduction [J]. IEEE Access. 10, 66356–66373 (2022).

Liu, X. & Li, S. Yu, Shuai, et al. Study on vibration and noise reduction measures for flow channels in hydraulic integrated valve Blocks[J]. Mach. Tool. Hydraulics, : 1–12 (2025). (in Chinese).

Rongsheng, L. Improvement of noise reduction structure of Direct-Acting pressure reducing Valve[J]. Machines 12 (11), 807 (2024).

Yao Jing et al. Cavitation evolution mechanism and periodic flow of aviation pressure Poppet valve[J]. Flow Meas. Instrum. 102, 102811 (2025).

Shang, L. I. U. et al. Self-Excited Oscillation characteris -tics of check valve flow system [J]. J. Rocket Propuls. 37 (03), 1–5 (2011). (in Chinese).

CHABANE, S. et al. Vibration and chattering of conventional safety relief valve under Built-Up back pressure [J]. J. Press. Vessel Technol. 137 (4), 1–14 (2015).

JIAN Jie. Flow-Induced Vibration and Stability Research of Spring-Type Pressure Regulating Valve [D]. Harbin Engineering University, 2024(in Chinese).

MO Guangyi. Simulation and Experimental Study on Poppet Valve Vibration Coupling [D]. Zhejiang University, 2014(in Chinese).

Peizi, L. I. & Zhanlin, W. A. N. G. Aircraft Hydraulic Transmission and Servo Control. Volume 1 [M]. Beijing: National Defense Industry, 1979(in Chinese).

Wanlu, J. I. A. N. G., Yong, Z. H. U. & Chao, Y. A. N. G. Nonlinear Dynamic Behavior of Direct-Acting Relief Valve [J]. China Mech. Eng., 24(20): 2705–2709 (2013). (in Chinese).

LIU Wei. Research on Hydraulic Feedback Proportional Cartridge Valve for Large Engineering Machinery [D]. Zhejiang University, 2015(in Chinese).

Yunxiang, Y. A. N. G., Na, Y. A. N. G. & Xiaoyong, G. A. O. Simulation Study on Steady-State Hydrodynamic Force of Large Flow Hydraulic Poppet Valve [J]. China Metalforming Equip. Manuf. Technol., 60(01): 125–128 (2025). (in Chinese).

Hui, W. A. N. G. et al. Dynamic Characteristics and Stability Analysis of Direct-Acting Poppet Relief Valve [J] Vol. 47, 144–147 (Machine Tool & Hydraulics, 2019). 13(in Chinese).

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Corresponding authors are required to acknowledge co-author contributions using [CRediT (Contributor Roles Taxonomy)] (https://credit.niso.org) roles. Not all CRediT roles will apply to every manuscript and some authors may contribute through multiple roles. e.g. [Chen Yong]: Conceptualization; [Chen Wenjie]: Data curation; [Zhang Luxi]: Formal analysis; [Xu Yongxiang]: Funding acquisition; [Chen Wenjie]: Investigation; [Chen Wenjie]: Methodology; [Xu Yongxiang]: Project administration; [Chen Yong] : Resources; [ Zhang Luxi ]: Software; [Chen Yong]: Supervision; [Chen Wenjie]: Validation; [Zhang Luxi]: Visualization; [Chen Wenjie]: Writing—original draft; [Chen Wenjie]: Writing–review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix:

Appendix:

Analysis is performed near a steady-state operating point (X, Q). At this point, the spool displacement is \(x=X\) flow rate \({Q}_{in}=Q\), pressures are \({p}_{1}={P}_{1}\),\({p}_{2}={P}_{2}\),\({p}_{3}={P}_{3}\), and the pressure differences are \({\Delta P}_{12}={P}_{1}-{P}_{2}\) and \({\Delta P}_{23}={P}_{2}-{P}_{3}\). Introducing small-signal variations around the steady state gives:

where \(\delta {p}_{1}={p}_{1}-{P}_{1}\) and \(\delta {p}_{3}={p}_{3}-{P}_{3}\);

Since the return oil volume \({V}_{3}\) is typically very large, pressure \({p}_{3}\) is relatively stable according to Eq. (9). Therefore,\(\delta {p}_{3}\approx 0\), and consequently \(\delta {p}_{v}=\delta {p}_{1}\);

Applying the incremental Laplace transform to Eq. (36) yields:

where:

For small valve openings , \({p}_{2}\approx {p}_{3}\), thus \({\Delta P}_{12}\approx {KX}_{0}\) and \({\Delta P}_{23}\approx 0\); Consequently:

Equation (40) simplifies to:

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, W., Chen, Y., Xu, Y. et al. Stability analysis and noise reduction of a cone-type poppet valve in an aero-hydraulic system. Sci Rep 16, 4633 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34964-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34964-7