Abstract

The first cervical vertebra (C1) is atypical in shape and bears a complex relationship with important neurovascular structures such as the vertebral artery and cervical spinal cord which are at risk of injury during misplaced screw fixation of C1. Placement of screws into the lateral mass of C1 vertebra is performed for stabilization of the craniovertebral junction. The objective of this study was to describe ideal screw dimensions, precise entry points, safe bony corridors, and ideal trajectories for placement of lateral mass screws in the Emirati population. CT scans of 160 Emirati patients (> 18 years) were studied and variables relevant to lateral mass screw fixation were measured. Screw entry at the centre of lateral mass, below its junction with the posterior arch, allowed straight screws of lengths of 20 mm and 19.5 mm in Emirati males and females, respectively. A medial angulation of 20° in males and 15° in females allowed maximum bone purchase. Screw entry at the junction of medial margin of posterior arch and lateral mass allowed straight screws of length 18 mm in both males and females. We recommend safe cephalic angulations of 19° and 16°in males and females, respectively. The mean critical width was 7.6 mm in males and 6.8 mm in females which would safely permit screws of width 4.0 mm. Pre-operative knowledge of the above dimensions would help in greater precision, minimizing the risk of injury to neurovascular structures in the vicinity of C1 lateral mass.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The first cervical vertebra (C1) consists of a bony anterior arch, a posterior arch, and a lateral mass complex (Figs. 1 and 2). The C1 vertebra is atypical in shape and bears a complex relationship with important anatomical structures in the craniovertebral region1. The lateral mass articulates with the skull above and the C2 vertebra below through the superior and inferior articular facets, respectively. Purchasing the lateral mass of C1 with a screw and including it in a construct provides good biomechanical stability to the cranio-vertebral region for treating fractures, correction of congenital cranio-vertebral junction anomalies, and tumors of this region. In close relationship to the C1 lateral mass is the vertebral artery within the foramen transversarium laterally, the cervical spinal cord and meninges within the vertebral canal medially, and the C1 and C2 spinal nerves, all of which are at risk of injury during misplaced screw fixation of the lateral mass2,3,4.

Several surgical techniques have been used for the stabilization of the craniovertebral complex. Techniques such as plate and screw fixation require precise landmarks for accurate placement of screws and plates5. Fusion of the occipito-cervical or atlantoaxial vertebra is an accepted treatment option for upper cervical spine instability caused by cervical trauma and various other disorders6. The C1-C2 fusion techniques have limitations, particularly the inevitable loss of rotatory motion at this level6,7,8. C1 lateral mass fixation is a more reliable technique offering biomechanical stability comparable with other alternate procedures such as trans-articular fixation and wiring techniques2,9. Though the anatomy of the C1 vertebra is well known, neurosurgical landmarks such as entry points, safe bony corridors, and ideal screw trajectories for lateral mass fixation are still unclear and require clarification to enable a safe surgical procedure2,10,11. The optimal point of entry of the screw is sometimes difficult to ascertain during surgery due to the absence of reliable anatomic landmarks and insufficient anatomic data3,10. Although various studies have been conducted among different population groups, they recommend variable entry points, screw length, and screw trajectories3,4,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. Two entry points are commonly used by neurosurgeons, each of which presents its own benefits. The first is on the middle of the posterior surface of the lateral mass just inferior to its junction with the posterior arch (Entry Point A)(Fig. 1 and 2)17, and the second is immediately inferior to the junction of the medial margin of the posterior arch with the lateral mass (Entry Point B) (Figs. 1 and 2)2,11.

Morphometry of bones and body proportions is known to vary between genders and racial groups. To date, no studies have reported safe anatomic landmarks for the performance of lateral mass screw fixation in the middle eastern population, particularly that of the Emirati population group. This study aimed to review CT images and describe precise anatomic landmarks for screw entry, bony corridors, safe trajectories, and optimum screw dimensions, for placement of titanium screws into the lateral mass of C1 in the Emirati population.

Methodology

The study was conducted at the Radiology Department of Rashid Hospital, Dubai Health, Dubai after ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Mohammed Bin Rashid University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dubai, and Dubai Scientific Research Ethics Committee (IRB no. DSREC-04/2024_06 dated 29/04/2024). The study complied with the ethics and standards laid down by the Declaration of Helsinki and its revision. CT images of the cervical spine, obtained over the last eight years, were reviewed over a 12-month study period. As the study only involved a retrospective review of CT images, a waiver of informed consent was obtained from the Institutional Review Board. Only adults (> 18 years of age), who are natives of the United Arab Emirates (Indigenous Emirati population) and had undergone CT imaging of the cervical spine at Rashid Hospital, were included in this study. Patients with structural deformity of the C1 vertebra, fractures, previous C1 spine surgery, or osteoarthritis were excluded from the study. All patients were assigned coded study numbers (1-n). De-identified data was collected to maintain anonymity and stored in encrypted laptops. The CT machines used in the hospital included RH: Siemens Somatom Force, TC HD: GE Discovery CT750HD, and TC Resus: GE Optima CT660. All images were read using the Agfa Enterprise Imaging System for Picture archiving and communication system (PACS).

Sample size estimation

The sample size was estimated based on a study done by Yuwakosol9 on the C1 lateral mass of the Thai population. They reported a mean medial inclination of 2.67 ± 1.8°. Using the formula, where Z is the normal ordinate, with a relative precision of 15% and a 95% confidence interval, it was estimated that 80 subjects should be studied. As the study dealt with two strata (i.e., male and female), 80 males and 80 females were studied in the Emirati population. After stratifying the subjects based on gender, a retrospective consecutive sampling method was employed.

Measured variables

The key variables observed in the Emirati population include:

-

1.

Max_AP_C1 – Maximum anteroposterior distance of C1 vertebra in midline (Fig. 1)

-

2.

Max_TD_C1 – Maximum transverse diameter of C1 vertebra (Fig. 1)

-

3.

D_EA_Mline – Distance from Midline to Screw Entry Point A on the middle of the posterior surface of lateral mass just inferior to its junction with the posterior arch (Fig. 1)

-

4.

D_EB_Mline – Distance between Midline to Screw Entry point B on the lateral mass inferior to the junction of lateral mass with medial margin of the posterior arch (Fig. 1)

-

5.

D_EB_EA – Distance between Entry Point B and Entry Point A.

-

6.

D_EA_A1 – Distance from Screw Entry Point A to the anterior cortex of Lateral Mass (LM) following a straight trajectory at Point A (Fig. 3)

-

7.

DEA_MBP – Distance from Entry Point A to Point A2 on the anterior surface of lateral mass following a medial angulation at Entry Point A allowing for maximum bone purchase (Fig. 3)

-

8.

MA_MBP – Safe degree of medial angulation from Entry Point A to Point A2 (Fig. 3)

-

9.

LA_EA – Safe degree of lateral angulation at Entry Point A (Fig. 3)

-

10.

M_MA_EA – Degree of maximum Medial Angulation at Entry Point A

-

11.

D_A2_ICA – Distance between Point A2 on the anterior cortex of lateral mass and internal carotid artery (ICA) (Fig. 3)

-

12.

D_A1_ICA—Distance between Point A1 on the anterior cortex of lateral mass and internal carotid artery (ICA) (Fig. 3)

-

13.

B_Lat – Distance between Straight screw trajectory at Entry Point A and foramen transversorium (Fig. 3)

-

14.

B_Med – Distance between Straight screw trajectory at Entry Point A and the vertebral canal (Fig. 3)

-

15.

D_A1_T – Distance between Point A1 on anterior cortex of lateral mass to anterior tubercle of C1 (Fig. 3)

-

16.

Max_W_LM – Maximum width of Lateral Mass (LM) (Fig. 4)

-

17.

C_W – Critical width of pedicle between foramen transversarium and the vertebral canal (Fig. 4)

-

18.

D_EB_B1 – Distance between screw entry Point B and the Point B1 on the anterior cortex of lateral mass depicting a straight trajectory of screw(Fig. 4)

-

19.

D_EB_B2—Distance between entry Point B and the Point B2 on the anterior cortex of lateral mass allowing for maximum bone purchase (Fig. 4)

-

20.

MA_EB_MBP – Safe degree of medial angulation at Entry Point B for maximum bone purchase; (Fig. 4)

-

21.

LA_EB – Safe degree of lateral angulation at Entry Point B (Fig. 4)

-

22.

HPA_J_LM– Height of Pedicle analog at its junction with the LM (Fig. 5)

-

23.

HLM_I_PA – Height of lateral mass inferior to the pedicle analog (Fig. 5)

-

24.

S_Cd_EA – Maximum caudal angulation of screw at Entry Point A (Fig. 5)

-

25.

S_Cp_EA – Maximum cephalic angulation of screw at Entry Point A (Fig. 5)

-

26.

S_Cp_SI – Safe Cephalic Angulation of screw at Entry Point A in a Superimposed lateral image (Fig. 6)

shows the various screw trajectories at Entry Point A. Line A-A1: Distance from Screw Entry Point A to the anterior cortex of Lateral Mass at A1 following a straight trajectory at entry point A; Line A-A2: Distance from Entry Point A to maximum bone purchase at Point A2 following a medial angulation at Entry Point A; Line A-A3: Distance from entry point A to anterior cortex at A3 for safe lateral angulation; Angle (A1-A-A2): Degree of Medial angulation from Entry Point A to Point A2; Angle (A1-A-A3) – Degree of safe lateral angulation at Entry Point A; ICA: Internal Carotid Artery; Pink arrow: Distance between Straight screw trajectory at Entry Point A and foramen transversorium; Yellow arrow: Distance between Straight screw trajectory at Entry Point A and the vertebral canal; T—Anterior Tubercle of C1.

shows the various screw trajectories at Entry Point B. Line B-B1: Distance from Screw Entry Point B to the anterior cortex of Lateral Mass at B1 following a straight trajectory at entry point A; Line B-B2: Distance from Entry Point B to maximum bone purchase at Point B2 following a medial angulation at Entry Point B; Line B-B3: Distance from entry point B to anterior cortex at B3 for safe lateral angulation; Angle (B1-B-B2): Degree of Medial angulation from Entry Point B to Point B2; Angle (B1-B-B3) – Degree of safe lateral angulation at Entry Point B; WL -maximum width of lateral mass; CW: Critical width of pedicle between foramen transversarium and vertebral canal.

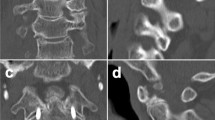

Some of the key measurements and landmarks are shown in Figs. 1–6. All parameters were measured in the bone window using the measuring tool in the PAC system software. Images in neutral neck position were studied in the axial and sagittal planes. Using axial and sagittal views, the entry points A and B were identified on the posterior surface of lateral mass immediately below its junction with the posterior arch. All measurements were done by a co-investigator (DS), who was trained to measure all parameters accurately by the principal investigator (IJP), radiologists, and the neurosurgeon. A pilot study was conducted, and the Intraclass Correlation analysis was performed to assess the reliability between the measured values of IJP and DS.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS, version 29.0. Mean, standard deviation (SD), and range were estimated for all the measured parameters. An independent student t-test for equality of means was performed to determine if the measured morphological parameters varied significantly between genders. P-values < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

A total of 470 CT scans (270 Emirati males and 200 Emirati females) were available during the study period. Using the consecutive sampling method, 160 adults (Male = 80 and Female = 80) fulfilling the inclusion criteria were studied in the Emirati population. CT Neck protocol was used to acquire 2.5 mm slice thickness. The tube potential was 100 kV and care dose 4D was used to modulate tube current. Other parameters included a rotation time of 1 s, an angle of tilt of zero degrees, pitch of 0.8, and matrix size of 512. Sagittal images were reconstructed in the workstation post-image acquisition and were used during the study. During the consecutive sampling, patient images that had rotated neck due to the presence of neck abscess, malignancy, and thyroid goiter (59 cases), dental implants causing scattered or blurred images (42 cases), or obvious degenerative changes of C1 due to osteoarthritis and spondylosis (16 cases) were excluded. No fractures or congenital anomalies of C1 were observed. Mean age of males was 51.3 ± 16.2 years (19-92y) and mean age of females was 47.1 ± 16.3 years (Range: 18–89y). The results of measured parameters are tabulated in Table 1. Intraclass correlation analysis showed a high correlation between the IJP and the DS (ICC coefficient > 0.94; p = 0.001).

Entry point A

Entry point ‘A’ was identified on the middle of the posterior surface of lateral mass just below its junction with the posterior arch of C1 (Figs. 1 and 2). The mean distance of Entry Point A to the midline was 17.4 ± 1.5 mm in males and 15.5 ± 1.2 mm in females (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). It is a commonly used entry point recommended by many neurosurgeons. The data of measured variables using entry point ‘A’ based on sex is shown in Table 1. The mean distances from the entry point ‘A’ to the anterior cortex point ‘A1’ with no inclination in any plane were 20.0 ± 2.1 mm and 19.5 ± 1.4 mm in males and females, respectively (p = 0.04) (Fig. 3). A screw with straight trajectory A-A1, lies at a safe distance of 9.2 mm away from the foramen transversarium laterally in both sexes (p = 0.86), and 8.5 mm and 6.5 mm away from the vertebral canal medially in the males and females respectively (p = 0.01). The mean distance from the entry point ‘A’ to the anterior cortex depicting the best bone purchase (Fig. 3) in males was 22.3 ± 2.5 mm allowing a medial inclination of 24.6 ± 4.3°; whereas in females, the mean distance from the entry point ‘A’ to the anterior cortex depicting the best bone purchase was 20.9 ± 1.2 mm allowing a medial inclination of 19.0 ± 1.1° (p = 0.001).

The results also revealed maximum medial inclinations of up to 31.8 ± 5.0° in males and 29.1 ± 0.9° in females (p < 0.001). The mean maximum lateral inclinations were up to 15.0 ± 3.2° in males and 12.9 ± 0.7° in females (p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). Our study showed a safe mean cephalic inclination of 10.8 ± 2.6° (1.2°–20.4°) in males and 10.9 ± 1.4° (1.1°-13.1°) in females (p = 0.8). The critical width (Fig. 4) between the vertebral canal and foramen transversarium was 7.6 ± 0.3 mm in males (7.0–8.5) and 6.8 ± 0.6 mm in females (5.0–7.9) (p = 0.001).

Entry point B

Entry point ‘B’ was defined on the posterior surface of lateral mass inferior to its junction with the medial margin of the posterior arch of C1 (Figs. 1 and 2). It is located at a mean distance of 14.0 and 12.3 mm from the midline in males and females respectively. The mean distances from the entry point ‘B’ to the straight exit point ‘B1’ (Fig. 4), with no inclination in any plane, were 18.4 ± 2.1 mm in males and 18.2 ± 1.3 mm in females (p = 0.47). Medial inclinations of 15.8 ± 6 degrees in males and 16.6 ± 2.2 degrees in females allowed for best bony purchase at Entry Point B (p = 0.02). Distances between entry point B and the anterior cortex depicting the best bony purchase was 21.1 ± 1.4 mm in males and 19.9 ± 1.3 mm in females (p = 0.01) (Fig. 4). Entry point B also allowed for safe lateral angulations of 23.2 ± 0.8 degrees in males and 21.2 ± 1.1 degrees in females, without risk of penetration of the medial wall of the foramen transversarium (p = 0.001) (Fig. 4).

Discussion

Several surgical techniques have been used for the stabilization of the craniovertebral complex of which C1 lateral mass fixation allows several unique advantages.13 Although the anatomy of the C1 vertebra is well known, the feasibility of neurosurgical landmarks such as entry point, screw dimensions, safe bony corridors, and ideal screw trajectories for lateral mass fixation have not been described in the Emirati population and therefore require clarification to enable a safe surgical procedure.3 Imaging and cadaveric studies have been instrumental in identifying safe screw corridors for placement of screws.18 Though Bi-Cortical screws have a higher pull-out strength compared to Uni-Cortical screws thereby achieving greater stability, the placement of bicortical screws which emerge from the anterior cortex carries the undue risk of injury to the hypoglossal nerve and the internal carotid artery.7,19 This study focuses on ideal screw dimensions and screw trajectories for the placement of C1 lateral mass screws in the Emirati population. The study reports on two commonly used entry points used by neurosurgeons and additional safety landmarks for ideal bony corridors and position of the internal carotid artery.

Entry point A

Goel et al. strongly recommended the use of Entry Point A for lateral mass screw fixation i.e., the center of the lateral mass below its junction with the posterior arch and 1–2 mm above the articular surface.17,20 However, locating Point A on the lateral mass is usually challenging due to the surrounding venous plexus, its rounded posterior surface, and the closely located C2 nerve root. 11,21 Sectioning or neurectomy of the C2 nerve root allows for better visualization but results in occipital numbness.11 However, for unknown reasons, patients in whom the C2 nerve was preserved reported post-operative neuralgia having a moderate to severe effect on their quality of life as reported via questionnaires.11,22.

In our study, the mean distances from the entry point ‘A’ to the straight anterior cortex point ‘A1’ were 20.0 ± 2.1 mm in males and 19.5 ± 1.4 mm in females (p = 0.04) (Fig. 3). The current study showed that entry of the screw with a trajectory perpendicular to Point A allowing no inclination permits a safe entry that is about 9.2 mm away from the foramen transversarium lodging the vertebral artery laterally in both sexes (p = 0.86), and 8.5 mm and 6.5 mm away from the vertebral canal medially in males and females respectively (p = 0.01). Other studies that recommend zero angulation at Entry Point A report a slightly lesser distance to the anterior cortex Point A1 of 17.6 mm in the German population7 and 17.3 mm in the Indian population23, with the exception of Ma et al., who reported 28.5 mm in the Chinese population10. The anteroposterior distance measured from Entry Point A to the anterior cortex at Point A1 was used to estimate the length of screw placements with zero inclination. The variations in distances observed are likely due to morphometric differences in the shape and size of C1 lateral mass in different populations.

There is a wide variation in the recommended medial and cephalic angulations at Entry Point A among different population groups (Table 2).

A slight medial angulation during the insertion of screws would certainly allow for better bone purchase resulting in greater biomechanic stability7. In our study, the mean distance from the entry point ‘A’ to the anterior cortex depicting the best bi-cortical bone purchase is 22.3 ± 2.5 mm in males allowing a medial inclination of 24.6 ± 4.3°. In females, the mean distance from the entry point ‘A’ to the anterior cortex depicting maximum bi-cortical bone purchase is 20.9 ± 1.2 mm with a medial inclination of 19.0 ± 1.1° (p < 0.001). Therefore, the study clearly showed that a medial angulation of 25° in Emirati males and 19° in Emirati females at Entry Point A allows for longer screws and better cortical purchase of bone ensuring better stability compared to zero inclination at entry. We also studied cephalic angulation from the Entry Point with the screw directed towards the anterior tubercle of C1 (Fig. 6). Our study showed a safe mean cephalic inclination of 10.8 ± 2.6° (1.2°–20.4°) in males and 10.9 ± 1.4° (1.1°-13.1°) in females (p = 0.8). A study by Albert et al., in the Indian population recommends a medial inclination of only 4° and a cephalad inclination of 5.4° which is far less compared to the Emirati population23. A Chinese study by Hong et al., recommends a medial inclination of 15° and a cephalad inclination of 20°12. A similar study in the German population recommends a safe medial inclination of only 7.9° and a cephalad inclination of only 2.4°, again significantly smaller inclinations compared to our Emirati findings7. A Caucasian study by Seal et al., allows a medial inclination of 15° and a cephalic inclination of 22°13. Goel, a strong advocate of Entry Point A recommends a medial inclination of 15° and a mean cephalic angulation of approximately 30°20. Our findings suggest that recommended medial inclination at Entry Point A is among the largest in the Emirati population (i.e. 25° in Emirati males and 19° in Emirati females) and least in the Indian and German populations (i.e. 4.0° and 7.9° respectively)7,23. Additionally, we also studied the maximum medial inclination at Entry Point A without risk of injury to the vertebral canal and the maximum lateral angulation without risk to the vertebral artery in the foramen transversarium. We report that Entry point A allows a maximum safe medial inclination of up to 32° in the male and 29° in the female in the Emirati population (p = 0.001).

Entry point B

Entry point ‘B’ was defined on the lateral mass at its junction with the medial margin of the posterior arch of C1 (Fig. 1). It is thought to cause less bleeding compared to Point A. Blagg et al., studied screw entry points in the New Zealand population and recommended that the best entry point is point ‘B’ where the medial margin of the posterior arch meets with the lateral mass2. They reported that the ideal direction was placement in the sagittal plane parallel to the posterior arch of C1 with no inclination at any plane. They state that a straight placement of the screw in the axial plane would allow for a mean distance of 8.8 mm from the vertebral artery foramen and 5.8 mm from the vertebral canal. Their study also allows a safe medial inclination of up to 20 degrees at Entry Point B2. Butt et al. studied the screw trajectory in subjects with Entry Point B, i.e., where the medial margin of the posterior arch meets the lateral mass11. They recommend zero degrees of angulation in the mediolateral and coronal planes with the screw passing straight forward from posterior to anterior. However, they propose a safe mean medial angulation of 23 ± 3.8° and a mean lateral angle of safety of 32 ± 5°. They reported the mean AP length of lateral mass from Entry Point B to be 17.7 + /- 1.7 mm (Range: 14.2 – 21.5) and the maximum width of the lateral mass to be 13.3 + /- 1.3 mm (Range: 10.1–16.6). In the current study on the Emirati population, Entry Point B allowed for a medial inclination of about 16° for best bony purchase, allowing a mean length of screw of 21 mm in males and 20 mm in females. Our study showed that Entry Point B allows a safe maximum medial inclination of 15.8° in the male and 16.6° in the female (p = 0.03), and a safe lateral inclination of 23° in the male and 21° in the female (p = 0.001). The study conducted by Blagg et al. reported that by using Entry Point B, none of the inserted screws breached the vertebral artery foramen, but were 2 mm in proximity to the foramen in only two cases2. However, the research done by Al-Habib et al., using entry point A, showed that the screw abutted the vertebral artery foramen in 23% of subjects with screw entry into the foramen in one subject21. These studies confirmed that the use of Entry Point A may predispose to vertebral artery injury unless a medial inclination is provided at Point A.

Surface location of screw entry points

The distance from the midline is often used as a guide to identify the screw entry point. In our study, the mean distances of Entry Point A to the midline were 17.4 ± 1.5 mm in males and 15.5 ± 1.2 mm in females (p < 0.001). Hong et al. reported a similar distance of 17.6 ± 1.2 mm in the Chinese population12. Significantly larger distances of 22.15 mm and 21.6 mm were reported by Ma et al. and Gebauer et al., in the Chinese10. and German population7 respectively. The junction of the medial margin of the posterior arch and the lateral mass can be easily palpated in the patient during surgery and is often used as an effective landmark to determine the screw entry into the lateral mass. Entry Point B was located 14.0 mm from the midline in males and 12.3 mm in females (p = 0.01). We also observed that Entry Point A was located at mean distances of 3.4 mm from Entry Point B in Emirati males and 3.2 mm from Entry Point B in Emirati females (p = 0.01). In their study on the Thai population, Bunmaprasert et al., reported that the ideal entry point is on the lateral mass 3.0 mm lateral to the intersection of the inferomedial edge of the posterior arch and the lateral mass with a 15° medial inclination for longer screws, which is very similar to our findings14. Hong et al., also reported that the center of the C1 lateral mass was 3.4 mm lateral to the bony intersection described above, which is also comparable to our study.

Recommended width of screws

The width of the screw can be determined by two limiting parameters. The first limiting factor is the narrowest width (CW) between the foramen tranversarium and vertebral canal. In our study, the critical width was 7.6 mm ± 0.3 mm in males and 6.8 ± 0.6 mm in females (p = 0.001). The second limiting factor is the sum of the height of the lateral mass inferior to the pedicle analog plus the height of the pedicle analog, which is 10.0 mm in males and 9.4 mm in females in our study. Hence, based on our findings in the Emirati population we recommend a safe screw width of even 4.5–5.0 mm. Hong et al. recommend a screw width of 3.5 mm in the Chinese population. Similar studies by Gebauer et al.7 and Tan et al.,24 recommend a screw width of less than 4.0 mm to be safe in the German and Chinese populations respectively. Resnick et al., found that the mean diameter of the lateral mass screw that can be placed in the Caucasian population was 5.3 mm, thereby easily allowing safe passage of 4.0 mm screws without any risk of damage to neurovascular structures25.

Location of internal carotid artery

Very few studies report the distance of the internal carotid artery from the anterior cortex of C1. Bicortical screws that penetrate the anterior cortex may pose a hazard to injury of the internal carotid artery. In our study, the internal carotid artery was situated at a safe distance of 20.9 ± 2.2 mm (17.8–26.8) and 18.6 ± 1.3 mm (15.4–21.9) from the anterior cortex (Point A2) in males and females respectively (p = 0.001). Our study also showed that the internal carotid artery was located at a mean distance of 13.9 ± 2.5 mm (9.6–22.6) and 13.9 ± 1.3 mm (10.4–17.8) from Point A1 on the anterior cortex in males and females respectively. (p = 0.88). A trajectory of the screw with a slight medial inclination at Entry Point A avoids proximity to the internal carotid artery at the anterior cortex of the lateral mass.

The variation observed in screw trajectories and ideal screw size is likely due to the morphometric differences in body proportions among representative populations and racial groups. Knowing the morphometry of C1 lateral mass in each group would permit precise pre-operative planning and choice of surgical screw sizes for C1 fixation. Although fluoroscopic techniques and on-table guided image navigation are popular, they are never a substitute for knowledge of variations in C1 anatomy, especially while practicing among a culturally diverse population such as in the United Arab Emirates. It is recommended that surgeons, operating on the lateral mass of C1, must understand the anatomy of the C1-C2 vertebral complex to avoid unexpected complications11. Advanced pre-operative imaging can be used to identify and evaluate anomalies in the morphology of C1. While several surgical techniques have been used to stabilize the craniovertebral complex, such as plate and screw fixation and fusion techniques, they result in an inevitable loss of rotatory motion. C1 lateral mass fixation is a reliable technique offering substantial biomechanical stability. Minor complications that may occur include the formation of hematomas and pseudoarthrosis. Neurosurgeons have their personal preferences for the selection of entry points and trajectories. Entry Point B can be easily located at the bony intersection of the medial margin of the posterior arch and the lateral mass. Insertion of a screw in the anteroposterior direction avoids the necessity for any angulation due to the screw trajectory being far from the vertebral canal and the foramen transversarium11. Entry at Point B can minimize the bleeding from the plexus of veins and the C2 root that are often related to Entry Point A. Surgeons have attempted innovative approaches to minimize bleeding from the venous plexus26,27,28. Retraction of the C2 nerve or its resection, and the use of bipolar cautery, gel foam, or thrombin can also be used to overcome these challenges11. Passage of lateral mass screws horizontally at Entry Point B with no angulation allows a remarkably safe distance from the vertebral artery. However, screw entry at Point A with a slight medial inclination of 10–20 degrees minimizes the risk of vertebral artery damage and maximizes bone purchase resulting in better stability of fixation. Entry at Point A after resecting the C2 nerve root also makes it easier to open the C1/C2 joint space for curetting and placement of a bone graft, which would improve bony fusion.

The novelty of this study is that it focuses on ideal screw dimensions and safe bony corridors for the placement of C1 lateral mass screws in the Indigenous Emirati population. This native Arab community forms a small yet significant 12% of the population, with 88% being expatriates from over 200 countries. Body proportions are known to vary between the genders and population groups. To the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have highlighted the morphometry of the C1 lateral mass with special relevance to neurosurgery in the Emirati population. This study attempted to elucidate the gaps in knowledge in C1 morphometrics in the Emirati population and compare it with morphometric studies in other population groups.

This study has a few limitations. We observed the CT imaging findings of 160 healthy young and elderly adults, with no obvious evidence of fracture or degenerative processes. Though the results of this study can be generalized to the native Arab population, the findings may differ in those with confirmed osteoporosis or other degenerative diseases. Although we studied a large sample of Emirati patients, with the benefit of providing key anatomical insights to the surgeon, variations may still exist, requiring that the surgeon ensure accuracy in the approach on a case-by-case basis.

Conclusion

In summary, the current study proposes ideal landmarks and safe trajectories for lateral mass screw placement in the Emirati population. We recommend the use of a straight trajectory at entry point B or a slight medial angulation while using entry point A to avoid injury to the vertebral artery within the foramen transversarium. A slight medial angulation of 10° in females and 15° in males at both entry points allows for better bone purchase. Screw lengths and screw widths are noted to be significantly smaller in females compared to males. A pre-operative knowledge of the above-mentioned findings may assist in exercising greater precision, thereby minimizing the unwanted risk of injury to crucial anatomical structures in the close vicinity of the C1 lateral mass.

Data availability

The de-identified datasets are available with the corresponding author and can be made available on reasonable request.

References

Chen, Q. et al. Posterior atlantoaxial fusion: a comprehensive review of surgical techniques and relevant vascular anomalies. J. Spine Surg. 6(1), 164–180 (2020).

Blagg, S. E., Don, A. S. & Robertson, P. A. Anatomic determination of optimal entry point and direction for C1 lateral mass screw placement. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 22(4), 233–239 (2009).

Hu Y, Dong W xin, Spiker WR, Yuan Z shan, Sun X yang, Zhang J, et al. An anatomic study to determine the optimal entry point, medial angles, and effective length for safe fixation using posterior C1 lateral mass screws. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 40(4):E191–198. (2015).

Elliott, R. E., Tanweer, O., Frempong-Boadu, A. & Smith, M. L. Impact of starting point and C2 nerve status on the safety and accuracy of C1 lateral mass screws: meta-analysis and review of the literature. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 28(5), 171–185 (2015).

Singla M, Goel P, Ansari MS, Ravi KS, Khare S. Morphometric Analysis of Axis and Its Clinical Significance -An Anatomical Study of Indian Human Axis Vertebrae. J Clin Diagn Res. AC04–9. (2015).

Harms J, Melcher RP. Posterior C1-C2 fusion with polyaxial screw and rod fixation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 26(22):2467–71. (2001).

Gebauer, M. et al. Evaluation of anatomic landmarks and safe zones for screw placement in the atlas via the posterior arch. Eur. Spine J. 19(1), 85–90 (2010).

Christensen DM, Eastlack RK, Lynch JJ, Yaszemski MJ, Currier BL. C1 anatomy and dimensions relative to lateral mass screw placement. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 32(8):844–8. (2007).

Yuwakosol, P. Morphometric Study for C1 Pedicle Screw Placement in Thai Patients. Asian J. Neurosurg. 17(3), 429–434 (2022).

Ma XY, Yin QS, Wu ZH, Xia H, Liu JF, Zhong SZ. Anatomic considerations for the pedicle screw placement in the first cervical vertebra. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 30(13):1519–23. (2005).

Butt, B. B. et al. Lateral mass screw placement in the atlas: description of a novel surgical technique, radiographic parameters, and review of the literature. J. Spine Surg. 7(3), 335–343 (2021).

Hong X, Dong Y, Yunbing C, Qingshui Y, Shizheng Z, Jingfa L. Posterior screw placement on the lateral mass of atlas: an anatomic study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 29(5):500–3. (2004).

Seal, C., Zarro, C., Gelb, D. & Ludwig, S. C1 lateral mass anatomy: Proper placement of lateral mass screws. J. Spinal Disord. Tech. 22(7), 516–523 (2009).

Bunmaprasert, T., Puangkaew, W., Sugandhavesa, N., Liawrungrueang, W. & Riew, K. D. The Intersection Between Lateral Mass and Inferomedial Edge of the C1 Posterior Arch: A Reference Point for C1 Lateral Mass Screw Insertion. Neurospine 18(2), 328–335 (2021).

Liawrungrueang, W., Riew, K. D., Sugandhavesa, N. & Bunmaprasert, T. Atlas (C1) lateral mass screw placement using the intersection between lateral mass and inferomedial edge of the posterior arch: a cadaveric study. Eur. Spine J. 31(12), 3443–3451 (2022).

Senoglu M, Karadag A, Kinali B, Bozkurt B, icke C, Halacoglu Savran D, et al. 2017 C1 lateral mass screw insertion from the caudal–dorsal to the cranial–ventral direction as an alternate method for C1 fixation: A quantitative anatomical and morphometric evaluation. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. (2017).

Goel A, Desai KI, Muzumdar DP. Atlantoaxial fixation using plate and screw method: a report of 160 treated patients. Neurosurgery. 51(6):1351–6; discussion 1356–1357. (2002).

Davidson, C. T., Bergin, P. F., Varney, E. T., Jones, L. C. & Ward, M. S. Planning C2 pedicle screw placement with multiplanar reformatted cervical spine computed tomography. J. Craniovertebral Junction Spine 10(1), 46 (2019).

Hong JT, Lee SW, Son BC, Sung JH, Kim IS, Park CK. Hypoglossal nerve palsy after posterior screw placement on the C-1 lateral mass. Case report. Journal of neurosurgery Spine [Internet]. 2006 Jul [cited 2024 Aug 27];5(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16850964/, (2024).

Goel, A. & Laheri, V. Plate and screw fixation for atlanto-axial subluxation. Acta Neurochirurgica 129(1–2), 47–53 (1994).

Al-Habib, A. F., Al-Rabie, A., Aleissa, S., Albakr, A. & Abobotain, A. Atlas instrumentation guided by the medial edge of the posterior arch: An anatomic and radiologic study. J. Craniovertebral Junction Spine 8(2), 97–102 (2017).

Witiw, C. D., Mansouri, A., Badhiwala, J. H. & Nassiri, F. Journal club: C2 nerve root transection during C1 lateral mass screw fixation: does it affect functionality and quality of life?. Neurosurgery 76(5), 638–640 (2015).

Albert AM. Posterior Screw Placement on Lateral Mass of Atlas: An Anatomical Perspective. International J. Anatomy Radiol. Surg. (2020).

Tan M, Wang H, Wang Y, Zhang G, Yi P, Li Z, et al. Morphometric evaluation of screw fixation in atlas via posterior arch and lateral mass. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). (2003).

Resnick DK, Lapsiwala S, Trost GR. Anatomic suitability of the C1-C2 complex for pedicle screw fixation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). (2002).

Wada, K., Tamaki, R., Yui, M., Numaguchi, D. & Murata, Y. C1 lateral mass screw insertion caudally from C2 nerve root – An alternate method for insertion of C1 screws: A technical note and preliminary clinical results. J. Orthop. Sci. 22(2), 213–217 (2017).

Paterson A, Byrne S, Hansen M, Kuru R. Modified C1 lateral mass screw insertion using a threaded K-wire. A technical note. J. Clin. Neurosci. (2020).

Pan, J. et al. C1 Lateral Mass Screw Insertion With Protection of C1–C2 Venous Sinus: Technical Note and Review of the Literature. Spine 35(21), E1133 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Mohammed Bin Rashid University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Dubai for funding the research study. We also thank Mr. Tariq Fazal URrahman for all the help extended in the Radiology department of Rashid Hospital.

Funding

Mohammed Bin Rashid University of Medicine and Health Sciences, MBRU-CM-RG2023-10.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DS- Data acquisition, Data interpretation, Critical revision of the manuscript, approval of the final version NN– Study design, Critical revision of the manuscript, approval of the final version RA- Study design, Data acquisition, Critical revision of the manuscript, approval of the final version UAB– Study design, Data acquisition, Critical revision of the manuscript, Approval of the final version JL– Conceptualization, Study Design, Data Analysis, Drafting of the manuscript, Critical revision of the manuscript, Approval of the final version of the manuscript. BVJ– Conceptualization, Study Design, Data acquisition, Data interpretation, Drafting of the manuscript, Critical revision of the manuscript, and approval of the final version. IJP: Conceptualization, Study Design, Data acquisition, Data analysis, Drafting of the manuscript, Critical revision, and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declarations

All experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, abide by the Declaration of Helsinki, and were in line with the regulations of the institutional research and ethical committees at the Mohammed Bin Rashid University of Medicine and Health Sciences and Dubai Scientific Research Ethics Committee.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Suresh, D., Naidoo, N., AlSharhan, R. et al. Determining anatomically-safe corridors for placement of lateral mass screws in the first cervical vertebra of the Emirati population – a CT study. Sci Rep 15, 1992 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85181-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85181-1