Abstract

Humans sometimes synchronize their steps to mechanical oscillations in the environment (e.g., when walking on a swaying bridge or with a wearable robot). Previous studies have discovered discrete frequencies and/or amplitudes where individuals spontaneously synchronize to external oscillations, but these parameters are often chosen arbitrarily or for convenience of a successful experiment and are sparsely sampled due to time constraints on subject availability. As a result, the parameter space under which human gait synchronization occurs is still relatively underexplored. Here we systematically measure synchronization over a broad range of parameters in machine oscillations, applied vertically near the body center of mass during walking. Two complementary experiments were utilized to characterize the amplitudes and frequencies where subjects’ gait matched the oscillation frequency within ± 0.02 Hz for at least 80% of 20 consecutive steps (i.e., synchronization). Individuals were found to synchronize at lower amplitudes and in less time when the oscillation frequency was nearer their baseline step frequency, as well as over a broader range of frequencies during larger oscillation amplitudes. Subjects also had a greater tendency to synchronize with oscillation frequencies below (rather than above) their baseline step frequencies. The results of this study provide a comprehensive mapping of parameters where synchronization occurs and could inform the design of exoskeletons, rehabilitation devices and other gait-assistive technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human locomotion is characterized by coordination of the limbs oscillating in time. The arms and legs swing forward and backward and even the body’s center of mass (CoM) bobs up and down1 as it ultimately travels in the desired direction and at the desired speed. When one oscillating system (e.g., locomotion) interacts with a second, the two systems can become synchronized, whether through entrainment or some other process. During synchronization, phase is mostly constant (known as phase-locking) and both systems oscillate at or near the same frequency2.

Synchronization has been observed in human locomotion under a broad range of circumstances where gait frequency is spontaneously matched to the frequency of an external oscillation. For example, gait synchronization sometimes occurs when humans walk over a swaying pedestrian bridge3,4,5 or on an oscillating treadmill6,7,8,9. Humans also synchronize their steps to the frequency of periodic torque pulses from wearable robots such as ankle10,11,12 or hip13,14 exoskeletons, and with rhythmic electrical stimulation of the medial gastrocnemius15. These examples reflect interactions between human subjects and artificial systems acting on specific joints and/or muscle groups within the body.

Despite the diverse circumstances under which humans synchronize their gait to external oscillations, there are also examples where synchronization does not occur or is rare9. In particular, the oscillation frequency plays a prominent role in determining whether synchronization will or will not occur. Previous studies have found that gait synchronization is weaker or does not occur when frequency of the external oscillation is either too high or too low, relative to the nominal gait frequency of the individual16,17. Indeed, a frequency of zero or infinity would be inconvenient or unattainable to manage synchronization, and so a finite range of intermediate frequencies should exist where humans spontaneously synchronize, on average. Although most studies quantify discrete frequencies where synchronization occurs, oscillation frequency as a continuous parameter is usually sparsely and arbitrarily sampled as a limitation of subject availability and reasonable time constraints on experiments.

The amplitude of an external oscillation also likely plays a substantial role in determining whether gait synchronization will occur. Trivially, an amplitude of zero will of course fail to elicit any meaningful synchronization. However, presumably there exists a low amplitude threshold where synchronization first occurs, and this threshold can be considered a metric of subject sensitivity to synchronization. That is, an individual can be considered more sensitive if they synchronize to lower amplitude oscillations. Notably, few gait synchronization studies involving machine oscillations have examined the effect of varying amplitude.

Beyond the independent influence of frequency and amplitude on synchronization—e.g., when one is varied, and the other is constant—it is likely that both parameters synergistically help determine when synchronization will occur. For instance, individuals may be more likely to synchronize over a broader range of frequencies given a larger amplitude, or at lower amplitudes (i.e., higher sensitivity) with frequencies requiring smaller adjustments (closer to baseline walking frequencies) versus at more extreme frequencies requiring larger adjustments. Here, we conducted two complementary experiments to comprehensively determine both the range of frequencies (as a function of amplitude) and the sensitivity to amplitudes (as a function of frequency) where gait becomes synchronized with external oscillations. Together, they help determine a mapping of synchronization behavior similar to the region of 1:1 frequency locking indicated as part of an Arnold tongue diagram18,19.

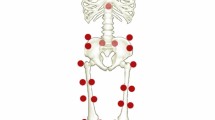

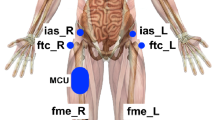

In both experiments, we used an experimental mechatronics system to apply vertical force oscillations to human participants walking on a treadmill in real time (Fig. 1). This system was previously used to evaluate metabolic energy expenditure of individuals synchronized with oscillations from the system17. It comprises a series of pulleys and cables connecting electromagnetic actuators to a body harness worn by participants during experiments. External forces are applied to the torso by varying tension in the harness via the actuators with the explicit intention of more directly affecting the body’s CoM and its dynamics. We see this interaction as a more direct manipulation of the fundamental task of locomotion—as opposed to other gait synchronization studies that have used wearable robots placed at specific joints—since the muscles, joints and other tissues of the legs are ultimately coordinated to affect the trajectory of the CoM through space and time20. Furthermore, we intend to reduce the potential for localized effects that may occur when specific joints or limbs are acted on, whilst simultaneously acknowledging that no system is immune to specialized influence through its connection to the body or any number of extraneous factors associated with the design of a specific system.

System schematic and images. (A) A schematic of the oscillator system is depicted in the sagittal plane. (B) Images of a subject walking in the system during a trial, from the side and from behind. Downward force came as the resultant of self-equalizing oblique cables. A curtain was used to blind the subject from any motion of the pulleys or motors, and headphones were used to play ambient noise to block out rhythmic sounds from the system. Harness pulleys were mounted on rollers to allow realignment with the subject’s fore-aft position on the treadmill.

In the first experiment (Time-varying Amplitude (TVA), Fig. 2A), a sinusoidal current signal was sent to the motors at a constant frequency (Δfm) relative to the subject’s baseline preferred step frequency (fp) and an amplitude that gradually increased over time (Am, as a percentage of subject body weight BW; see Materials and Methods for details). The motor amplitude where synchronization initially occurred (step frequency fs matched motor frequency fm) was considered as the subject’s sensitivity in that trial (\(A_{m}^{*}\)). In the second experiment (Time-varying Frequency (TVF), Fig. 2B), the motor amplitude was held constant, but the frequency was gradually modulated—first away from and then returned to the subject’s baseline preferred step frequency. The frequency where synchronization was first rejected (step frequency not equal to motor frequency) was considered the subject’s frequency range (\({\Delta }f_{m}^{*}\)). Subjects participated in seven TVA trials (\({\Delta }f_{m} = 0, \pm 3, \pm 6, \pm 9 \% f_{p}\)) and six TVF trials (\(A_{m} = 10, 20, 30\% {\text{ BW}}\); Δfm > fp and Δfm < fp) for a total of thirteen trials per subject (N = 10). In both experiments, time-varying oscillations were used to efficiently test a more comprehensive parameter space (for TVA: 1% to 30% BW in 1% amplitude increments; for TVF: − 10% to + 10% fp in 1% frequency increments), as opposed to discrete selections of amplitude and frequency in each trial for convenience and/or brevity of the experiment.

Experiment protocols. (A) In the Time-varying Amplitude (TVA) Experiment, motor frequency is held constant (fm, blue) while motor amplitude increases over time (Am, dark red). Subjects are predicted to eventually synchronize their gait with the force oscillations (by matching their step frequency fs with the motor frequency fm), and the corresponding amplitude defines sensitivity (\(A_{m}^{*}\)). This experiment is repeated for multiple motor frequencies (Δfm) relative to their baseline preferred frequency (fp), and waveforms of current sent to the motors (Ic(t) in red; not to scale) are shown with amplitude gradually increasing over time. (B) In the Time-varying Frequency (TVF) Experiment, motor frequency is varied gradually over time, and amplitude is held constant. Subjects are predicted to synchronize their gait with the oscillations over a finite range of motor frequencies (\({\Delta }f_{m}^{*}\)) relative to their baseline preferred step frequency. This experiment is repeated for multiple amplitudes.

In this manuscript, we refer to synchronization as the process by which individuals match the frequency of their step cycle—either voluntarily or involuntarily—to that of an external oscillation. Previously, most studies have used this phenomenon to test walking control mechanisms regarding nonlinear oscillators in the central nervous system (i.e., through the process of entrainment)11. However, in the current work, we remain agnostic as to the specific control mechanism(s) involved; instead, our objective is to map out the oscillation parameters where human walking is observed to synchronize with an external oscillation system and to confirm whether humans track oscillation parameters gradually changing in real time. Between the two experiments, we expect the results to provide helpful insights to researchers developing wearable robots and rehabilitation protocols by providing a thorough understanding of the intrinsic range of frequencies and amplitudes where individuals are responsive to external machine oscillations applied to the torso during walking.

Results

An example trial from the TVA Experiment is shown in Fig. 3. Step frequency (magenta, Fig. 3A) begins approximately at the preferred cadence measured during baseline (fp) but gradually drifts toward the motor frequency (fm) after active oscillations begin at time zero. Eventually, synchronization emerges and is sustained until the oscillations cease near the end of the experiment. During active oscillations, motor amplitude (dark red, Fig. 3B) slowly increases over time, and the measured impulse from the upward cable (light blue) increases in proportion to amplitude (\(J_{c} = 0.018A_{m}\), R2 = 0.920). Traces of force profiles from active oscillations (red, Fig. 3C) show increasing peak force at three demonstration amplitudes during the experiment (Am = 10, 20, 30% BW force) and match reasonably well to the commanded force signal sent to the motors (grey dashed lines). Phase of the force traces is inconsistent at low amplitude but stabilizes after the subject becomes synchronized with the system. The alignment of peak force from active oscillations occurs after double stance (DS) and before midstance (MS) of the step cycle (i.e., slightly after toe off from the trailing leg).

Example trial. The TVA Experiment is shown for \({\Delta }f_{m} = + 6\% f_{p}\). (A) Step frequency over time (fs, magenta), begins near baseline preferred and drifts toward motor frequency (fm, blue) during synchronization. (B) Motor amplitude (Am) shown in red (left axis) and the positive (i.e., pulling upward) measured impulse (Jc) relative to baseline plotted in light blue (right axis). (C) Mean active force oscillation (± 1 standard deviation) plotted for Am = 20, 30% BW, and all traces shown for Am = 10% BW, since force alignment is inconsistent sans synchronization. Force signal commanded to motors (grey dashed), shown for comparison to measured forces. Force curves are associated with data outlined in boxes in (A) and (B), labeled (i), (ii) and (iii). Alignment of force oscillations relative to double stance (DS) and middle stance (MS) is viewed relative to the step cycle.

Subjects are more likely to synchronize with oscillation frequencies near baseline

The majority of subjects synchronized with external oscillations in all trials of the TVA Experiment. Synchronization was confirmed when a subject’s step frequency matched the motor frequency within ± 0.02 Hz for at least 16 out of 20 consecutive steps (see Methods for more details). Towards the beginning of the experiment, subjects tended to exhibit step frequencies near those measured during baseline conditions; however, as motor amplitude increased over time, subjects began to vary step frequency in the direction of the motor frequency until synchronization occurred (Fig. 4). The number of subjects who synchronized at least once during the trial varied per the oscillation frequency prescribed. For example, in trials with relatively high motor frequencies (Δfm = 6, 9%) only 7 out of 10 subjects synchronized, whereas in trials with frequencies closer to baseline (Δfm = ± 3%), 9 out of 10 subjects synchronized. Note, individual data for all subjects, including for those who did not synchronize, are shown in Figure S1 of the Supplementary Materials.

Frequency response to TVA experiment. Filtered subject step frequency (Freq.) is shown over time (magenta is median and grey shaded region is 25–75th percentiles of data from all subjects who synchronized during the trial). Motor frequency is held constant (blue) and subject baseline preferred is indicated (dashed grey line) for reference. The prescribed motor amplitude (Amp.) is shown (red) over the course of the experiment. The number of subjects included in each data trend are indicated at the top of each subplot (N).

Subjects exhibited varying sensitivity to synchronization depending on the motor frequency prescribed in experiments (Fig. 4). In general, subjects synchronized at lower oscillation amplitudes and in less time when motor frequencies were prescribed more closely to their baseline preferred step frequency. For example, when motor frequency was 3% higher or lower than preferred step frequency at baseline, subjects first synchronized at the relatively small amplitudes of 11 and 6% BW (75 and 51 s after initiation of active oscillations, respectively; Fig. 4A,D). Conversely, for motor frequencies of 9% higher and lower than baseline, subjects did not synchronize until amplitudes as high as 26 and 18% BW were observed (209 and 167 s after initiation of active oscillations, respectively; Fig. 4C,F). In general, subjects tended to synchronize at lower amplitudes in less time (i.e., higher sensitivity), with oscillation frequencies closer to subjects’ preferred step frequencies at baseline, and also, at frequencies lower than baseline (Δfm < 0).

Figure 5 shows subjects’ amplitude sensitivity to synchronization in a format similar to an Arnold tongue diagram, where the region of synchronization is defined near baseline (i.e., one-to-one frequency locking). Here, however, the region highlights the lowest motor amplitude where subjects first began to synchronize with external oscillations (\(A_{m}^{*}\) in Fig. 5) as they slowly increased in the TVA experiment. Decreased sensitivity was found at motor frequencies far away from baseline preferred step frequencies. Specifically, the amplitude and time to initial synchronization both increased by approximately 1.7% BW and 15 s, respectively, for every ± 1% difference in motor frequency away from baseline (p < 0.001*, see Table 1). Subjects also demonstrated higher sensitivity to motor frequencies lower than baseline preferred step frequency (\(A_{m}^{*}\) lower when Δfm < 0 vs. when Δfm ≥ 0). In fact, subjects were approximately 53% more sensitive to synchronization at negative versus positive motor frequencies (p = 0.007*). The external impulse felt by subjects increased linearly with the prescribed motor amplitude (\(J_{c}^{*} = 0.019A_{m}^{*}\), R2 = 0.906) and thus, may have mechanically contributed to the sensitivity of subjects’ interactions with the oscillation system.

Amplitude sensitivity to synchronization. Motor amplitudes where subjects first synchronized with the external oscillations (\(A_{m}^{*}\)) are shown to indicate subject sensitivity as a function of motor frequency (Δfm). The measured external impulse associated with amplitude sensitivity (\(J_{c}^{*}\)) is also shown in a second vertical axis. Each data point represents the observed sensitivity of a single subject during a single trial (N = 56). Interpolation from a linear regression model is shown. In this experiment, lower amplitudes are interpreted to mean that a subject has higher sensitivity to synchronization and vice versa. In this sense, subjects exhibited higher sensitivity to synchronization at motor frequencies below their preferred step frequency at baseline (i.e., Δfm < 0).

Frequency range of synchronization increases with oscillation amplitude

During the TVF Experiment, all subjects (10 out of 10) synchronized with external oscillations in all conditions, albeit to varying degrees. Most subjects immediately synchronized with oscillations as they were initiated at subjects’ previously measured baseline step frequencies. As the motor frequency slowly drifted away from baseline values, subjects began to adjust their step frequency to maintain synchronization (Fig. 6). In some cases, subjects were able to follow the motor frequency through the maximal range; however, subjects often did not maintain synchronization throughout, and instead reverted to a more moderate step frequency. In the latter case, these subjects typically reinitiated synchronization as the motor frequency drifted back towards baseline values near the end of the experiment. Note, individual data for all subjects, including for those who did not synchronize, are shown in Figure S2 of the Supplementary Materials.

Frequency response to TVF experiment. Filtered subject step frequency (Freq.) is shown over time (magenta is median and grey shaded region is 25–75th percentiles of data from all subjects who synchronized during the trial). Motor frequency is varied over time (blue) and subject baseline preferred is indicated (dashed grey line) for reference. The prescribed motor amplitude (Amp.) is shown (red) as a step function until the end of the experiment. The number of subjects included in each data trend are indicated at the top of each subplot (N).

Synchronization frequency range was defined by the most extreme step frequencies subjects synchronized to during the experiment (either above or below baseline), before reverting to more moderate cadences. Although frequency range was not significantly different depending on whether the motor frequency was drifting away or towards baseline values (p = 0.722, see “Direction” in Table 1), it increased with motor amplitude (p < 0.001*) and thus, external impulse (Fig. 7). For example, on average, subjects synchronized their walking over a broader range of frequencies above baseline with 30% BW amplitudes versus 10% BW (range was 6.69% and 3.59% fp,t, respectively). The same was true for motor frequencies below baseline: range was − 9.89% fp,t with 30% BW amplitudes versus − 7.70% fp,t with 10% BW. The best-fit exponent describing the effect of motor amplitude on frequency range had a value of 0.31, meaning it increased sharply at lower amplitudes, and then more gradually at larger amplitudes. This exponent may, in part, be influenced by a ceiling effect in the data, given some subjects were able to follow motor frequencies over the full range. Frequency range increased more rapidly with motor amplitude by 55.1% (p < 0.001*) for frequencies below baseline step frequency (\({\Delta }f_{m}^{*} = - 3.63A_{m}^{0.31}\)) versus for those above (\({\Delta }f_{m}^{*} = 2.34A_{m}^{0.31}\)). That is, subjects exhibited synchronized gait at more extreme low versus high frequencies.

Frequency range of synchronization. The range of frequencies associated with subject synchronization (\({\Delta }f_{m}^{*}\)) are shown as a function of motor amplitude (Am) prescribed in testing conditions. A linear function was used to map external impulse from the oscillations onto motor amplitude, relative to baseline. Each data point represents a single subject during a single trial (N = 114), where variation in motor amplitude data is artificially added for visibility. Interpolation is used to show trendlines of frequency range over motor amplitude (solid black curve).

Discussion

Synchronization depends on oscillation parameters

A majority of subjects adjusted step frequency to synchronize with external oscillations in both experiments, but it depended greatly on the prescribed frequency and amplitude of the oscillations, as well as the experiment protocol itself. For example, subjects exhibited synchronization in 56 out of 70 trials for the TVA experiment and in 60 out of 60 trials for the TVF experiment. Synchronization was likely easier in the TVF experiment initially, since the active oscillations were initiated at the individual’s baseline frequency (requiring little to no gait frequency adjustment) before eventually drifting to higher/lower frequencies later in the trial. Additionally, subjects consistently exhibited synchronization at lower amplitudes in the TVA experiment (higher sensitivity) when oscillation frequencies were closer to preferred baseline step frequency (Fig. 5), requiring less adjustment from subjects to synchronize. However, this effect may have also been due to the fact that smaller step frequency adjustments simply took less time to adapt to regardless of amplitude changes (recall, amplitude increased nearly linearly with time in the TVA experiment). Changes in synchronization sensitivity were shown statistically by the positive coefficient in front of the motor frequency term (β = 1.711, p < 0.001*, see Table 1) indicating synchronization at lower amplitudes occurring sooner in the experiment (i.e., higher sensitivity) for motor frequencies near baseline.

Previous studies have shown that the baseline preferred step frequency in humans can be explained by minimization of energy expenditure21,22,23, where trade offs predict an optimal intermediate step frequency24,25. On the one hand, energy cost associated with swinging the leg increases at higher frequencies26,27,28, but on the other hand, cost also increases at lower frequencies (longer steps) due to rising collisional energy losses that must be replaced with net positive work of the leg muscles in order to maintain steady gait29,30. It is possible that synchronizing with an external oscillation could help to reduce metabolic expenditure31, perhaps even at step frequencies not equal to baseline. Although we previously found no significant effect of synchronization on the energy cost of walking, we did however, identify energy saving strategies with regards to the alignment of force oscillations within the step cycle17. Regardless, the tendency to synchronize gait with an external oscillation would likely be moderated by the energetic penalty of adjusting step frequency away from baseline preferred.

In our study, we found that subjects had an increased amplitude sensitivity and frequency range at motor frequencies below baseline preferred step frequency. For example, in the TVF Experiment, an interaction term between the non-linear motor amplitude (\(A_{m}^{0.31}\)) and the sign of motor frequency (\(sgn\left[ {{\Delta }f_{m} } \right]\)) had a linear coefficient significantly less than zero (β = − 0.635, p < 0.001*, see Table 1), meaning that subjects synchronized over a broader frequency range with motor frequencies below baseline versus above. A similar tendency towards synchronization at lower frequencies was found in the regression model for the TVA Experiment. While we cannot rigorously explain the reason behind this effect, there are many possibilities. For example, perhaps extra effort of the stance leg to accommodate longer steps (at lower frequencies) is partly offset by assistance from vertical force oscillations. That is, push off may be downregulated in the presence of supplemental upward external forces just after toe off. Future studies could use electromyography of the triceps surae to confirm if downregulation occurs. Some evidence of increased synchronization at frequencies below baseline have also been found in Arnold tongue diagrams of walking on an oscillating treadmill6, as well as with periodic electrical stimulation of the leg muscles32, and so this effect may also be explained by non-mechanical mechanisms.

Other researchers have employed external actuator systems to encourage step frequency modulation in subjects, not through synchronization with external oscillations but rather by experimentally manipulating subjects’ energy cost surfaces33,34,35. These studies aimed to motivate relatively modest changes in step frequency (± 2–8%). In the current study, we observed instances of relatively large step frequency adjustments: between − 11.5 and + 13.1% for the TVA Experiment and between − 14.2 and + 10.8% for the TVF Experiment. Indeed, some subjects synchronized at the most extreme frequencies prescribed in all trials and as such, our data may still not capture the full range of synchronization.

Given the range of synchronization frequencies increased with amplitude (Fig. 7), this may help to explain our observations of larger step frequency adjustments in our experiments more generally. For example, Simha et al.34 used an external actuator system to provide near-constant forces of ± 15% BW near the lower torso (compared to our dynamic force oscillations of up to 30% BW magnitude) and found step frequency adjustments of about 1.3%. However, this study used quasi-static forces pulling in the fore-aft direction as opposed to our dynamic oscillations in the vertical direction, so any comparisons should be considered with great caution. Still, it is possible that humans are more sensitive to dynamic forces as opposed to static forces acting on the body.

Other, more comparable studies, have shown similar adjustments to step frequency (14–15%) during synchronization with exoskeletons at a constant speed12,14,16 and even found synchronization at frequencies greater than 50% above baseline in some cases, when allowing for proportional changes to treadmill speed12. On the other hand, these studies applied intermittent torque pulses at the ankle or hip instead of continuous sinusoidal oscillations at the CoM. The degree to which synchronization with external oscillations generalizes across different body parts and waveform shapes (e.g., square vs. sinusoid) is not currently well understood. We have at least performed similar experiments with the same system described here but with different subjects and found consistent results, including a tendency for synchronization at frequencies closer to baseline step frequency, at frequencies below baseline, and at higher amplitudes17.

Force oscillations are consistently aligned with the gait cycle

During synchronization, the phase alignment of force oscillations relative to the gait cycle is nearly constant. Of all the possible alignments available, synchronized subjects in our experiments consistently walked with a phase that aligned the peak upward active oscillation force after toe off of the trailing leg—i.e., after double stance and before midstance (Fig. 3C). It is unclear why subjects seem to prefer this particular alignment with force oscillations; however, these results are highly consistent with those of a previous experiment conducted with the same oscillation system17. In that study, we noted that the preferred phase alignment was associated with increased positive net work from oscillations, and subjects who received more positive work had reduced metabolic energy expenditure.

Although it is possible that the preferred phase alignment during synchronization is limited to some arbitrary characteristics of our oscillation system, a different study also found that energy consumption is reduced when horizontal external periodic forces provide net positive power to the body CoM36, and this occurred at a similar (though not identical) alignment of force oscillations. Other synchronization studies using joint exoskeletons have found that individuals align the timing of periodic forces so as to maximize positive mechanical power from the device, either during push off at the ankle10 or slightly later to assist leg swing initiation at the hip13. Subjects in the current study arguably chose a similar strategy; that is, they aligned peak upward forces at approximately peak upward CoM velocity to incur maximal positive external power. In addition, synchronization with electrical stimulation of the medial gastrocnemius was coordinated with plantar flexion torques during push off—actions in the gait cycle highly associated with positive CoM work—but also, towards the end of the swing phase15. The sum of these studies may suggest that individuals often prefer to synchronize with oscillatory perturbations that assist or enhance positive power at the affected joint or body, but more work is needed on this topic.

Given subjects generally preferred a specific phase alignment during synchronization, one may consider whether phase of the initial oscillation helped to determine the occurrence of synchronization in any given trial. However, this seems unlikely, given the experiment protocol. For example, in all trials of the TVA Experiment, the initial motor amplitude was sufficiently low (1% BW) such that subjects did not synchronize for 95 steps on average, over which time, they would have been exposed to the full range of phase alignments. This is because phase shifts with every step when step frequency is not synchronized to the external oscillation. As such, the initial phase likely played a small role, if any, in determining synchronization. Notably, when comparing trials with synchronization versus without it, no specific value of initial phase was identified in either group. While some subjects were less likely to synchronize than others, this was not due to initial phase. One subject accounted for 50% of TVA trials where synchronization did not occur (Subject 8, see Supplemental Materials), two subjects had two of seven trials where they did not synchronize (Subjects 7 and 9), and all others had one or less trials where they did not synchronize. Therefore, we speculate that the tendency for synchronization may be related to unknown individual characteristics. It will be important to identify these characteristics in future studies so that potential applications can be tailored to the individuals who might benefit the most (e.g., in rehabilitation).

Implications for wearable robots and rehabilitation

Importantly, the level of assistance that exoskeletons should provide to their human wearers for rehabilitation purposes or performance enhancement remains an open debate and one that could benefit from studies on gait synchronization. In recent years, a promising new technique for exoskeleton control has emerged, referred to as human-in-the-loop optimization. In this approach, parameters of an assistive torque are modulated in real time to minimize some physiological objective such as metabolic energy cost37,38,39 or muscle activity38. With human-in-the-loop optimization, the actions of the exoskeleton are prescribed to the wearer—that is, the machine adjusts to the human. However, there are other applications where it may be helpful for the human to adjust to the machine (e.g., rehabilitation, robot-assisted motor learning)40.

For example, walking speed is often slower in seniors above a certain age41,42 as well as in many individuals affected by a wide range of neurological conditions (e.g., following stroke43). Thus, a common goal of rehabilitation is to help patients walk at faster speeds43,44,45. Since speed increases with step frequency22,25,46, one possible rehabilitation approach could be to incorporate a protocol similar to the Time-varying Frequency Experiment presented here, where oscillation frequencies are driven at a patient’s low baseline step frequency and are slowly increased over time. This protocol could potentially help patients to relearn walking with faster stepping cadences and—if incorporated with a self-paced treadmill—brisker speeds. Based on the results of the current study, it is unclear that the faster stepping cadences would be retained once external oscillations ceased. However, this rehabilitation approach would require much more extensive time exposure to synchronization over the course of weeks or months. The retention of learned gait patterns through synchronization over long time durations has not yet been demonstrated empirically.

A different rehabilitation approach could vary amplitude of external oscillations as in the Time-varying Amplitude Experiment presented here. This approach would allow individuals to retrain gait mechanics of the CoM through guidance by external oscillations, similar to studies demonstrating haptic guidance by robots to enhance motor skill learning47. Specifically, external oscillations would be used to guide the CoM through a desired trajectory (e.g., a normative trajectory measured in healthy individuals), and an adaptive oscillator controller48 could be used to manage easy synchronization with stepping. Slowly, the amplitude would be pulled back via an adaptive algorithm based on performance (“fading”49) until the patient could manage CoM mechanics of the desired trajectory through actions of their own legs with little to no external assistance.

Limitations

The experiments detailed in this manuscript were designed to quantify oscillation parameters (frequency, amplitude) under which humans demonstrate gait synchronization with external oscillations; in both experiments, time was an implicit variable. However, the time of exposure to oscillations relative to the rate of change of oscillation parameters in time likely plays a role in determining synchronization behaviors, perhaps most notably for subjects who have no prior experience with the system. In particular, since amplitude in the TVA experiment is approximately a linear function of time, it is unclear whether sensitivity results occur due to increasing amplitudes or from longer exposure times with oscillations. Here, we primarily analyze synchronization as a function of amplitude (rather than time) since this interpretation is consistent with results from the TVF experiment as well as other gait studies showing increased synchronization at higher amplitudes6,17 unchanging in time. Still, time of exposure remains an underexplored variable that may influence synchronization independent of varying oscillation parameters at the time scale of our experiments.

It is also possible that repeated exposures over longer time scales (e.g., across multiple days) may affect the degree of synchronization under various circumstances. Although each subject walked with external oscillations for a total of thirteen unique trials over the course of both experiments, we avoided repeated measurements on subjects for the same combination of oscillation parameters to avoid fatigue and overlong experiments. While it is certainly possible that prolonged exposure to external oscillations over consecutive days, weeks or even months may lead to increased levels of synchronization, a recent study found no significant increase in synchronization over consecutive days, on average13.

Another limitation of our study lies in the generalizability of our results to other oscillation systems. We explicitly designed our actuated pulley-cable system to provide vertical forces near the CoM of individuals wearing a body harness. But synchronization to forces applied at the limbs or extremities is likely to vary depending on the anatomy and function of the specific body segment. For example, attachment of artificial systems to the body is a common challenge to the design of wearable machines depending on its location on the body. In our system, straps associated with the body harness contribute some compliance and laxity such that they may sometimes rub and slide along the body. Despite our best efforts to minimize such effects, for example by maintaining a taught tension and facilitating proper fitting to subjects, it is possible that these and other factors may have influenced our results in an unknown manner.

Furthermore, our actuators are controlled with an open loop current control so as to provide sinusoidal tension in the harness. Due to this simple controller and some neglected dynamics in the pulley-cable system (compliance, pulley friction and inertia, etc.), oscillation forces experienced by subjects were not idealized sinusoids. We do not speculate as to the precise effect such imperfections may have on our results; however, the impulse of each oscillator cycle scales linearly with motor amplitude (Fig. 3B, R2 = 0.920) and so we consider this metric instead of others (e.g., work per cycle or peak power) somewhat arbitrarily.

We remain ignorant as to the precise biological mechanisms responsible for sensing and responding to external oscillations in the environment. Researchers have previously proposed an episodic supervisory architecture for walking control, where a neuro-mechanical periphery operates semi-autonomously until intervention is needed11. Still, many such theories require further testing, and unknown details persist with regards to the control of walking in the presence of external oscillations.

Conclusion

We have shown that humans adjust gait patterns to match mechanical oscillations from a custom-built mechatronics system and can track oscillations varying gradually in time. We conducted two complementary experiments and employed generalized linear mixed-effect regression models in order to quantify amplitudes and frequencies where subjects synchronize to external force oscillations. In general, subjects took less time before they synchronized with oscillations of significantly lower amplitudes (i.e., higher sensitivity) when the oscillation’s frequency was near their preferred baseline step frequency. Subjects also demonstrated a significantly increased frequency range with larger oscillation amplitudes. Furthermore, subjects tended to synchronize with significantly greater sensitivity and frequency range at lower versus higher oscillation frequencies (relative to baseline). Through both experiments, we have thoroughly sampled gait synchronization behaviors across fundamental parameters of external oscillations (amplitude and frequency), thus defining a comprehensive mapping of synchronization. These data can help inform future studies seeking to improve our understanding of synchronization in gait and simultaneously provide insights on the design and development of gait-assistive technologies and rehabilitation science.

Materials and methods

Participants

A convenience sample of ten healthy university students (five male, five female) were recruited. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) subject height was 1.71 ± 0.07 m, leg length was 0.91 ± 0.06 m, weight was 65.7 ± 12.2 kg and age was 26.2 ± 2.9 years. Subjects were excluded if they had any musculoskeletal injuries or neurological conditions affecting gait or the ability to carry a heavy backpack. All participants provided informed consent to participate, and these studies were approved by an ethics review board at the University of Calgary (REB16-1517). All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The participant shown in Fig. 1 provided their informed consent for their image to be included in an online open access publication.

Experiment protocol

Subjects were first asked to walk on a treadmill for ten minutes to establish a baseline gait measurement. During this time and throughout all testing, the treadmill belt speed (vb) was programmed so that non-dimensional speed, \(\tilde{v}\), approximately equaled 0.4.

where L is the subject’s leg length measured from the ground to the greater trochanter during standing and g is the gravitational acceleration on Earth (9.81 m s−2). The belt speed was rounded to the nearest tenth of a km/hour, per the treadmill’s available resolution, and this resulted in an average speed of 4.3 km/hour or about 1.19 m s−1 (range of 1.14 to 1.22 m s−1 for all subjects). During baseline testing, subjects wore a body harness connected to a pulley-cable system where actuators provided a constant nominal tension (approximately 10% BW) to reduce slack in the system, but the average net force on the body was zero since one cable pulled up while the others pulled down. Subjects also experienced added inertia from the motors and associated hardware connected in the system, as well as small amounts of friction and damping. Each subject’s baseline preferred step frequency (fp) was measured as the mean of data during the last minute of baseline, and the motor frequency (Δfm) was prescribed in testing conditions as a percent difference from this baseline.

The desired oscillation amplitude was prescribed as a percentage of body weight force (BW) for individual subjects and was converted to Amperes when prescribing sinusoidal current oscillations to the motors. Ultimately, this resulted in near-sinusoidal continuous oscillations of tension in the harness, which contrast with intermittent force pulses used in previous studies (e.g., square waveforms16). Although the precise effect of waveform shape on synchronization has not been evaluated previously, we chose to use a sinusoid in part because vertical CoM motion is approximately sinusoidal (albeit slightly asymmetric in time) during walking, and because we wanted subjects to interact with both upward and downward forces in each perturbation cycle. More details regarding the oscillation system can be found in the Supplementary Information of a previous manuscript17.

Two distinct experiments were used to test subjects’ synchronization sensitivity and range. During the Time-varying Amplitude (TVA) Experiment (Fig. 2A), subjects walked in the harness for two minutes with constant, nominal tension to avoid cable slack. Next, oscillations were initiated at constant frequency (relative to the subject’s baseline step frequency), starting at very low amplitudes and slowly increasing in regular increments (1% BW every 16 cycles) until the amplitude reached a maximum of 30% BW (Fig. 2A). The oscillations continued at 30% BW for another 120 cycles and then ceased, allowing subjects to walk for two additional minutes and prepare for the end of the trial. Step frequency data were collected as amplitude increased over time, and the amplitude where the subject first synchronized was identified as a measure of the subject’s sensitivity to synchronization with the external oscillations. This experiment was repeated for multiple motor frequencies expressed as percent differences from baseline step frequency (\({\Delta }f_{m} = 0, \pm 3, \pm 6, \pm 9\% f_{p}\); see Fig. 2A).

During the Time-varying Frequency (TVF) Experiment (Fig. 2B), subjects walked on the treadmill while wearing the harness for two minutes with no active oscillations. Then current oscillations were prescribed to the motors at a constant amplitude and frequency matching baseline preferred step frequency. This allowed subjects to synchronize to the oscillations more easily at the start of the trial. After 120 cycles (slightly over a minute, on average), the motor frequency slowly drifted away from baseline in regular increments (0.01 Hz every 16 cycles, Fig. 2B) until reaching a maximum frequency 10% away from baseline. Step frequency was monitored until the subject rejected synchronization with the oscillations, and this frequency was noted as a measure of the subject’s frequency range. Eventually, the motor frequency drifted back towards baseline step frequency and subjects could reinitiate synchronization. Afterward, the oscillations ceased, and the subject walked for an additional two minutes before the trial’s end. This experiment was repeated for multiple amplitudes (Am = 10, 20, 30% BW) and frequencies drifting higher or lower than baseline step frequency (i.e., Δfm > 0 or Δfm < 0, respectively, Fig. 2B).

In both experiments, trial conditions were randomized to mitigate any ordering effects, and oscillations were initiated randomly relative to each subject’s gait cycle. A curtain was used to blind subjects from any motion of the pulleys or motors (Fig. 1b). Ambient noise was played through headphones to help block rhythmic sounds of the system. During trials, subjects were asked to walk in whatever manner felt “most natural” or required the least amount of effort. However, subjects were encouraged to explore different aspects of their gait, including step length.

Measurements and analysis

In order to measure step frequency and approximate CoM kinematics, inertial measurement units (IMUs; Xsens Technologies B.V., Enschede, The Netherlands) were placed at each ankle and the lower back. Signal peaks were detected from the ankle sensors and step frequency was calculated as the inverse of the time duration between peaks. Acceleration data from the back sensor were used to approximate center-of-mass motion (acquisition rate = 100 Hz). These data were integrated twice over time to get velocity and displacement, and a moving average (window set to stride time) was subtracted from the signal to adjust for low frequency drift error. A moving average filter (window of ± 5 steps at each data point) was also applied to step frequency measurements to illustrate trends more clearly over time. Step frequency (fs) data were normalized by the subject’s baseline frequency (fp) measured while walking in the system with the motors inactive.

Force oscillations applied to subjects in experiments were measured via custom in-line tension transducers built with strain gauges (Micro-Measurements CEA-06-125UW-350, Wendell, NC, USA) and configured in half-bridge circuits similar to previous experiments26. The strain gauges were bonded to C-shaped steel hooks and measured tension in cables pulling on the body harness during experiments (Fig. 1). The strain gauge signals were passed to a strain conditioning amplifier (National Instruments, SCXI-1000 with SCXI-1520 eight-channel universal strain gauge module connected with SCXI-1314 terminal block, Austin, Texas USA), digitized (NI-USB-6251 mass termination) and acquired in a custom virtual instrument in LabVIEW (National Instruments) at an acquisition rate of 100 Hz. The transducers were calibrated with known weights before every testing session using a least squares linear regression to quantify a conversion factor from volts to Newtons force (R2 > 0.99). At the beginning of each trial, a few seconds of data were collected where the subject stood still before starting the treadmill. During this time, the transducer signals measured force from the motors’ weight in the system plus nominal tension from the motors pulling the system taut. This initial tension was averaged over a ten second interval and subtracted from the subsequent signal in the trial.

Tension forces and kinematics were segmented into blocks of data comprising every step cycle identified in all trials. Step cycles were distinguished by peaks in the vertical acceleration of the CoM (approximately indicating the middle of double stance). These data were interpolated at regular intervals matching the average resolution of the raw data collection (about 55 data points per step) and means and SDs were calculated to represent an average step for each subject. The baseline tension force was subtracted from experiment force traces to approximate active oscillation force—that is, the tension forces from active oscillations prescribed to the motors. Oscillation forces from the upward-pulling cable were integrated over time, for each step, as a measure of the positive external impulse relative to baseline.

The timing of force oscillations was used to calculate phase relative to the gait cycle. Pulse signals were recorded in LabVIEW marking the timing of peak current sent to the motors relative to the start time of a given step cycle (Δtp). In addition to data synchronization, the pulse signals were used to calculate the phase alignment of peak current relative to the step cycle (ϕ), where 0° indicates the middle of double stance and midstance occurs at around 180°.

Due to dynamics in the system, there was a slight delay from when peak current was driven to the motors to when tension spiked in the harness. The average delay, Δϕ, was calculated for all subjects and trials, and phase was shifted as appropriate (\(\phi^{*} = \phi + {\Delta }\phi\)).

Defining synchronization, sensitivity and range

Synchronization was defined with arbitrary thresholds: any step frequencies within ± 3 SDs (about ± 0.02 Hz) of the prescribed motor frequency for at least 16 out of 20 (80%) consecutive steps. The SD of subjects was determined from the last minute of data during the baseline measurement (i.e., no active oscillations). Sensitivity was defined as the lowest motor amplitude where synchronization first occurred (\(A_{m}^{*}\)) during the TVA Experiment. As such, this metric indicates a behavioral threshold (i.e., synchronization), as opposed to a perceptual threshold (e.g.,50). Frequency range was defined as the highest (or lowest) motor frequency where synchronization occurred (\({\Delta }f_{m}^{*}\)) in the TVF Experiment, depending on the motor frequencies of a given trial condition. Frequency data for sensitivity and range were expressed as a percentage difference from the subject’s average step frequency over the final minute preceding active oscillations in each trial (%fp,t).

Statistical analysis

Filtered step frequency data were interpolated at equal time intervals matching the data acquisition rate. Median values of the interpolated data were taken across all subjects who synchronized at least once in the trial and at each time point. Quartiles characterized the spread of the distribution for each time point at 25% and 75% levels.

Generalized linear mixed-effects regression models were used to assess various outcomes during experiments. The mixed model was chosen to control for repeated measurements of subjects participating in multiple trials each; subject was included in the models as a random effect. The statistical models were implemented in MATLAB (R2020a, MathWorks) using the “fitglme” function with the maximum pseudo likelihood method for parameter estimation and a compound symmetric covariance structure.

Two separate models were used to assess synchronization amplitude sensitivity (\(A_{m}^{*}\)) and frequency range (\({\Delta }f_{m}^{*}\)) each. Fixed effects of the former included magnitude of the motor frequency (\(\left| {{\Delta }f_{m} } \right|\)) and an interaction term between motor frequency and its sign (\(\left| {{\Delta }f_{m} } \right| x sgn\left[ {{\Delta }f_{m} } \right]\)). An intercept was included in this model to assess whether subjects required non-zero amplitudes to synchronize, even when the motor frequency matched baseline preferred step frequency. Fixed effects of the second model included a linearized term for motor amplitude (\(A_{m}^{n}\)), where n was varied from 0.1 to 5.0 in order to determine the exponent that minimized the Akaike information criterion (AIC)51. This approach was taken to assess goodness of fit for different exponent values since residuals of the data clearly indicated a non-linear relationship when assuming a zero intercept (i.e., no synchronization range with zero amplitude oscillations). However, the precise nature of the non-linear relationship was unknown a priori. Finally, simple univariate linear regressions were used to compare prescribed motor amplitude with measured external impulse from the upward-pulling cable tension.

Significance of fixed model effects was evaluated with 95% confidence limits and post hoc t tests where p values were adjusted (padj) using the Bonferroni correction52, depending on how many tests were performed in each model. Tests were considered significant if padj < 0.05. Throughout the manuscript, unadjusted p values are reported, and significance is indicated with asterisks.

Data availability

All data generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Crowe, A., Schiereck, P., de Boer, R. W. & Keessen, W. Characterization of human gait by means of body center of mass oscillations derived from ground reaction forces. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 42, 293–303 (1995).

Strogatz, S. H. & Stewart, I. Coupled oscillators and biological synchronization. Sci. Am. 269, 102–109 (1993).

Dallard, P. et al. London Millennium Bridge: Pedestrian-induced lateral vibration. J. Bridg. Eng. 6, 1–6 (2012).

Strogatz, S. H., Abrams, D. M., McRobie, A., Eckhardt, B. & Ott, E. Crowd synchrony on the Millennium Bridge. Nature 438, 43–44 (2005).

Joshi, V. & Srinivasan, M. Walking crowds on a shaky surface: Stable walkers discover Millennium Bridge oscillations with and without pedestrian synchrony. Biol. Lett. 14, 20180564 (2018).

Nessler, J. A., Heredia, S., Bélair, J. & Milton, J. Walking on a vertically oscillating treadmill: Phase synchronization and gait kinematics. PLoS ONE 12, e0169924 (2017).

Peters, B. T., Brady, R. A. & Bloomberg, J. J. Walking on an oscillating treadmill: Strategies of stride-time adaptation. Ecol. Psychol. 24, 265–278 (2012).

Tackett, E. The Effect of Noise on Gait Synchronization to a Vertical Oscillating Treadmill (California State University San Marcos, 2018).

Bocian, M., Burn, J. F., Macdonald, J. H. G. & Brownjohn, J. M. W. From phase drift to synchronization—Pedestrian stepping behaviour on laterally oscillating structures and consequences for dynamic stability. J. Sound Vib. 392, 382–399 (2017).

Ahn, J. & Hogan, N. Feasibility of dynamic entrainment with ankle mechanical perturbation to treat locomotor deficit, in 2010 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology 3422–3425 (IEEE, 2010). https://doi.org/10.1109/IEMBS.2010.5627892.

Ahn, J. & Hogan, N. Walking is not like reaching: Evidence from periodic mechanical perturbations. PLoS ONE 7, e31767 (2012).

Thalman, C., Debeurre, M. P. & Lee, H. Entrainment during human locomotion using a soft wearable ankle robot. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 6, 4265–4272 (2021).

Lee, J., Huber, M. E. & Hogan, N. Gait entrainment to torque pulses from a hip exoskeleton robot. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 30, 656–667 (2022).

Baye-Wallace, L., Thalman, C. M. & Lee, H. Entrainment during human locomotion using a lightweight Soft Robotic Hip Exosuit (SR-HExo). IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 7, 6131–6138 (2022).

Thorp, J. E. & Adamczyk, P. G. Mechanisms of gait phase entrainment in healthy subjects during rhythmic electrical stimulation of the medial gastrocnemius. PLoS ONE 15, e0241339 (2020).

Ahn, J. & Hogan, N. The basin of entrainment of human gait under mechanical perturbation, in ASME Dynamic Systems and Control (2008).

Schroeder, R. T., Croft, J. L. & Bertram, J. E. A. Evaluating the energetics of entrainment in a human–machine coupled oscillator system. Sci. Rep. 11, 15804 (2021).

Glass, L. & Mackey, M. From clocks to chaos; the rhythms of life, in From Clocks to Chaos: The Rhythms of Life (Princeton University Press, 1988).

Milton, J. & Ohira, T. Mathematics as a laboratory tool: Dynamics, delays and noise, in Mathematics as a Laboratory Tool: Dynamics, Delays and Noise (Springer, 2014).

Croft, J. L., Schroeder, R. T. & Bertram, J. E. A. The goal of locomotion: Separating the fundamental task from the mechanisms that accomplish it. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 24, 1675–1685 (2017).

Bertram, J. E. A. Constrained optimization in human walking: Cost minimization and gait plasticity. J. Exp. Biol. 208, 979–991 (2005).

Bertram, J. E. A. & Ruina, A. Multiple walking speed–frequency relations are predicted by constrained optimization. J. Theor. Biol. 209, 445–453 (2001).

Croft, J. L., Schroeder, R. T. & Bertram, J. E. A. The landscape of movement control in locomotion: Cost, strategy, and solution. Front. Psychol. 10, 716 (2019).

Schroeder, R. T., Bertram, J. E. A., Son Nguyen, V., Vinh Hac, V. & Croft, J. L. Load carrying with flexible bamboo poles: Optimization of a coupled oscillator system. J. Exp. Biol. 222, jeb203760 (2019).

Kuo, A. D. A simple model of bipedal walking predicts the preferred speed-step length relationship. J. Biomech. Eng. 123, 264–269 (2001).

Polet, D. T., Schroeder, R. T. & Bertram, J. E. A. Reducing gravity takes the bounce out of running. J. Exp. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.162024 (2018).

Doke, J. & Kuo, A. D. Energetic cost of producing cyclic muscle force, rather than work, to swing the human leg. J. Exp. Biol. 210, 2390–2398 (2007).

Doke, J., Donelan, J. M. & Kuo, A. D. Mechanics and energetics of swinging the human leg. J. Exp. Biol. 208, 439–445 (2005).

Kuo, A. D. Energetics of actively powered locomotion using the simplest walking model. J. Biomech. Eng. 124, 113–120 (2002).

Kim, J. & Bertram, J. E. A. Compliant walking appears metabolically advantageous at extreme step lengths. Gait Post. 64, 84–89 (2018).

Schroeder, R. T. & Bertram, J. E. Minimally actuated walking: Identifying core challenges to economical legged locomotion reveals novel solutions. Front. Robot. AI 5, 58 (2018).

Adamczyk, P. G. & Thorp, J. Zapping Walking People—Why, How, and What Happens? (2023).

Selinger, J. C., O’Connor, S. M., Wong, J. D. & Donelan, J. M. Humans can continuously optimize energetic cost during walking. Curr. Biol. 25, 2452–2456 (2015).

Simha, S. N., Wong, J. D., Selinger, J. C. & Donelan, J. M. A mechatronic system for studying energy optimization during walking. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 27, 1416–1425 (2019).

Wong, J. D., Selinger, J. C. & Donelan, J. M. Is natural variability in gait sufficient to initiate spontaneous energy optimization in human walking?. J. Neurophysiol. 121, 1848–1855 (2019).

Antonellis, P., Mohammadzadeh Gonabadi, A., Myers, S. A., Pipinos, I. I. & Malcolm, P. Metabolically efficient walking assistance using optimized timed forces at the waist. Sci. Robot. 7, eabh1925 (2022).

Ding, Y., Kim, M., Kuindersma, S. & Walsh, C. J. Human-in-the-loop optimization of hip assistance with a soft exosuit during walking. Sci. Robot. 3, eaar5438 (2018).

Zhang, J. et al. Human-in-the-loop optimization of exoskeleton assistance during walking. Science 356, 1280–1284 (2017).

Slade, P., Kochenderfer, M. J., Delp, S. L. & Collins, S. H. Personalizing exoskeleton assistance while walking in the real world. Nature 610, 277–282 (2022).

Basalp, E., Wolf, P. & Marchal-Crespo, L. Haptic training: Which types facilitate (re)learning of which motor task and for whom? Answers by a review. IEEE Trans. Haptics 14, 722–739 (2021).

Riley, P. O., Della Croce, U. & Casey Kerrigan, D. Effect of age on lower extremity joint moment contributions to gait speed. Gait Post. 14, 264–270 (2001).

Novaes, R., D., Miranda, A., S. & Dourado, V., Z. Usual gait speed assessment in middle-aged and elderly Brazilian subjects. Rev Bras Fisioter 15, 117–122 (2011).

Richards, C. L., Malouin, F. & Dean, C. Gait in stroke: Assessment and rehabilitation. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 15, 833–856 (1999).

Corbetta, D., Imeri, F. & Gatti, R. Rehabilitation that incorporates virtual reality is more effective than standard rehabilitation for improving walking speed, balance and mobility after stroke: a systematic review. J. Physiother. 61, 117–124 (2015).

Figueiredo, S. et al. Nordic walking for geriatric rehabilitation: A randomized pilot trial. Disabil. Rehabil. 35, 968–975 (2013).

Nilsson, J., Thorstensson, A. & Halbertsma, J. Changes in leg movements and muscle activity with speed of locomotion and mode of progression in humans. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica 123, 457–475 (1985).

Reinkensmeyer, D. J. & Patton, J. L. Can robots help the learning of skilled actions?. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 37, 43–51 (2009).

Ronsse, R. et al. Oscillator-based assistance of cyclical movements: Model-based and model-free approaches. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 49, 1173–1185 (2011).

Crespo, L. M. & Reinkensmeyer, D. J. Haptic guidance can enhance motor learning of a steering task. J. Motor Behav. 40, 545–557 (2008).

Medrano, R. L., Thomas, G. C. & Rouse, E. J. Can humans perceive the metabolic benefit provided by augmentative exoskeletons?. J. NeuroEng. Rehabil. 19, 26 (2022).

Akaike, H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. in 267–281 (Budapest, Hungary, 1973).

Dunn, O. J. Multiple comparisons among means. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 56, 52–64 (1961).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery grant (312117-2012 and 04823-2017) received by J.E.A.B., a University of Calgary Eyes High Doctoral Recruitment Scholarship (EHDRS) received by R.T.S., and a Biomedical Engineering Equipment Grant received by R.T.S. In addition, the authors would like to thank Gregory Sawicki, Vinzenz von Tscharner and Nigel Shrive for their helpful comments and discussion regarding this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.E.A.B. and R.T.S. conceived the project and experiments. R.T.S. performed all data collection and analysis, design and development of the mechatronics system, and composed the initial manuscript. R.T.S., J.E.A.B. and J.L.C. all contributed to subsequent manuscript revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Schroeder, R.T., Croft, J.L. & Bertram, J.E.A. Amplitude and frequency of human gait synchronization with a machine oscillator system. Sci Rep 15, 1629 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85202-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85202-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Self-reinforced piezoelectric chip for scaffold-free repair of critical-sized bone defects

Nature Communications (2025)