Abstract

Glass system of 45B2O3–20ZnO–30BaO–5X, (where X represents CaO, MgO, Al2O3, TiO2, CuO and Fe2O3) in mole percentage was investigated for gamma ray radiation shielding experimentally. Six glass composites were fabricated and the density was measured experimentally and the BZBCa glass sample has the least density with a value of 3.932 g cm−3 and this is due to the presence of CaO in it, and the sample BZBFe has the highest density with a value of 4.031 g cm−3. Through comparing the linear attenuation coefficient (LAC) data (experimental and Phy-X) for the BZBX glass samples, the LAC values for glass samples obtained experimentally and using Phy-X are in a very close range. All the glass samples have the greatest LAC values at 0.0595 MeV, the lowest energy value. Sample BZBCu has a LAC value of 16.203 1/cm, which is also the highest LAC value among all the studied glasses, this is as a result of the high density of this glass and due to the high atomic number of Cu. The glasses’ transmission factor (TF) at 1 cm thickness against energy was determined. The TF values of all the glasses were almost zero. The TF values increased significantly for all the glasses when the energy was increased to 0.662 MeV, and for sample BZBCa its TF value increases 74.08%, which was the highest TF value increase. The half-value layer and other shielding parameters have been determined experimentally.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Our environment is not devoid of radiation, whether the radiation is natural or man-made. Natural radiation is cosmic rays coming from space and radiation coming from the interior of the Earth, whether from radioactive rocks, global warming, etc. Meanwhile, industrial radiation is employed in many fields including agriculture, industry, and medicine. In the medical field, radiation is used in surgery, treatment, and radiological diagnosis, and in the agricultural field, radiation is used to fertilize soil, nourish plants, preserve agricultural food products, and develop animal production. In the industrial field, radiation is used in industrial radiography, industrial metrology, well logging, calibration systems, etc. As radiation spreads, protection must be provided because it is harmful to living organisms and can cause tissue damage and cancer if a person has exposure to a large radiation dose. Therefore, protection from radiation reduces the health risks resulting from it1,2,3,4,5.

One of the main radiation protection factors is the manufacture of shielding materials. There are many materials that are used to protect against ionizing radiation5. Concrete is used for its low cost and high durability, but it can degrade over time and is an inelastic material6. Lead is an effective material against ionizing photons due to its high atomic number and density, but it is considered a toxic substance7. Boron is considered a highly efficient neutron absorber, but it does not show its efficiency with photons and other particles8. Because of these limitations, there has been and continues to be continuous development in preparing shielding materials that provide the least environmental damage, the highest shielding efficiency, and are suitable for the place to be protected.

Density is known to play an important role in the attenuation process. Recently, glass systems of different densities have been manufactured, and each glass compound has different properties. We are always looking for materials that are environmentally friendly, low in cost, adaptable and durable, in addition to good protection against ionizing photons and neutrons9,10. These properties are available in glass, and it is possible to change the density of the compound easily by replacing some oxides with others. In addition to this, it is possible to obtain a transparent glass composition that has all the mentioned properties. For this reason, glass is suitable as a shielding material in industrial and medicine applications11,12.

There has been the recent use of borate glasses in myriad applications because they are characterized by good durability, mechanical, and thermal properties, and also the addition of heavy metals gives them a high ability to attenuate radiation13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21. Adding barium oxide and zinc oxide to borate glasses gives the compound an increase in density in addition to improving thermal stability and improving its mechanical properties. In this work, the proportions of B2O3, BaO and ZnO in the compound were fixed, and different types of other oxides were added, such as titanium oxide, iron oxide, and copper oxide. The addition of these oxides gives different properties in terms of transparency and density, in addition to thermal and attenuation properties22,23,24,25.

The use of the experimental method in shielding measurements is important before using the shielding material in various applications, because it gives realistic results for the shielding composite. Experimental measurement requires the presence of radioactive point gamma source (emits single or multi-lines) and a detector works to determine the radiation falling on it and calculate its intensity, as well as a lead collimator so that a narrow beam can be obtained during the measurement. Before measuring, the detector should be calibrated in terms of energy and efficiency, and the distances between the source, the shielding material, and the detector should be adjusted26,27,28,29.

In this work, an experimental technique was utilized to determine the radiation attenuation performance of 45B2O3–20ZnO–30BaO–5 (Metal Oxide), since the metal oxides used were TiO2, Al2O3, CaO, CuO, Fe2O3 and MgO. Different gamma point sources such as Co-60, Am-241 and Cs-137, in addition a HPGe-detector (semiconductor high purity germanium detector) were used in the measurements. The linear attenuation coefficient (LAC) and the radiation shielding efficiency (RSE), as well as other shielding parameters were determined and compared with other commercial materials for shielding purposes.

Materials and methods

Fabrication of the glass system

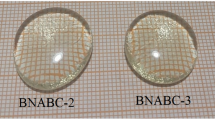

Six glass composites were prepared according to the glass system (45B2O3–20ZnO–30BaO–5X), (where X represents CaO, MgO, Al2O3, CuO, TiO2 and Fe2O3) in mole percentage via the melt-quenching method. The powders B2O3, ZnO, BaO and X-oxide were purchased from Sigma Aldrich Chemicals with ~ 99.8% purity. The powders were mixed, putted in aluminum crucible, heated to 1000 °C in electric furnace, the mixed powder was melted, transferred to another furnace with 350 °C for annealing, left inside the furnace till reach the room temperature and the glass was formed. The preparation steps can be summarized in Fig. 1 and the real picture of prepared glass is shown in Fig. 2. Table 1 tabulates the present glasses’ chemical composition.

Physical properties

The density of BZBX-glass sample is determined using the Archimedes method, which is based on the principle of buoyancy as shown in Eq. (1)22.

where mr and mL represents the mass in both liquid and air, respectively, in the case of water being used as the immersing liquid. By knowing the total molecular mass of the glass (M), the molar volume can be calculated by next equation22:

The packing density (Vt) and oxygen molar volume (Vo) have been deduced from the molar volume as given in the formula below:

where Vi represent the packing factor of the oxide calculated from its ionic radii30,31, \({x}_{i}\) and \({n}_{i}\) are the mole fraction and the fraction of oxygen atoms for each component oxide. The Poisson’s ratio (σ) can be obtained from packing density by using the following equation:

The refractive index of the prepared samples can be determined by next relation32,33:

From the refractive index, the dielectric constant (\(\varepsilon\)) and the reflection loss (R) can be calculated by the following formula34,35:

Attenuation parameters measurements

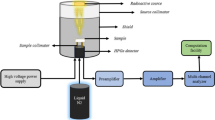

For the investigated glasses, Monte Carlo simulations were previously used to study their radiation shielding properties at specific energies3,4, while in this study, experimental methods were employed to measure these properties. This experimental approach provides direct measurements and enhances the understanding of the glasses’ shielding performance. Experimental work offers tangible results that reflect real-world conditions, highlighting differences that may not be captured through simulations. The current glass samples’ gamma-ray shielding parameters were experimentally measured via the narrow beam method, as shown in Fig. 3. The components include a gamma point sources with initial activity 1.48 kBq at 1 September 1998 (Am-241, Cs-137, and Co-60), a lead collimator (inner hole diameter: 8 mm), and a HPGe or high purity germanium detector with relative efficiency 24% and energy resolution 1.96 keV at second line of Co-60 (1.333 keV). The energy range of the point source emission is 0.060 to 1.333 MeV. The energy and efficiency calibration were done for the detector using this point sources and before the measurement takes place, calibration of the detector is required using a material with known attenuation, as is the glass sample’s position between the detector and the gamma source. Under identical conditions, the detector is run once with the sample and once without the glass sample (with thickness ranges from 3.4 to 4 mm) to determine the net count rate or the area under the photopeak for both cases, which are coded as C and Co, respectively. The detector is operated for a sufficient time to obtain the lowest error in the area measurements (< 1%) or to obtain 10,000 counts. The time here varies from one source to another. Cs-137 and Am-241 do not complete 20 min, while Co-60 takes an hour to obtain an error of less than 1% due to its half-life. From the net count rate which calculated using Genie-2000 software as shown in Fig. 4 and the measured glass sample’s thickness (t), it is possible to calculate the LAC, which is defined by the likelihood of gamma interaction through the glass sample’s linear thickness, and can be determined using Eq. (1)36,37,38,39,40:

Other important shielding factors, such as half-value layer (HVL) and tenth-value layer TVL), mean free path (MFP) and radiation protection efficiency (RPE), measure the ability of shielding materials to resist incident radiation, and can be found through Eqs. (2)–(5), which can also express and calculate N and N041,42:

Results and discussion

Figure 5 plots the fabricated glass sample’s density. Clearly, BZBCa has the least density with a value of 3.932 g cm−3 and this is due to the presence of CaO in it, followed by sample BZBM (3.944 g cm−3), sample BZBA (3.955 g cm−3), sample BZBT (3.965 g cm−3), sample BZBCu (g cm−3), while sample BZBFe has the highest density of 4.031 g cm−3 as a result of the presence of Fe2O3 in it which increases it’s atomic weight. Table 2 shows some physical properties of the fabricated glass such as molar volume (Vm), packing factor (Vt), oxygen molar volume (Vo) and refractive index, where the results showed that most of the properties are close to each other for the different prepared glass systems.

In terms of the BZBT glass sample, Fig. 6 compares the LAC data (experimental and Phy-X). As shown in Fig. 6 there’s a very close range in the LAC values for sample BZBT obtained experimentally as well as the one obtained using Phy-X. For example, at the lowest energy with a value of 0.060 MeV, the two results obtained has their highest values; result obtained by Phy-X is the highest with a LAC value of 15.875 cm−1 while experimentally the value was 15.438 cm−1. With a 0.060 to 0.662 MeV energy increase, the LAC values dropped drastically as shown in Fig. 6, where the experimental value decreases to 0.292 cm−1, while the Phy-X value decreased to 0.302 cm−1. At 1.33 MeV, the experimental (0.198 cm−1) and Phy-X values (0.204 cm−1) are in good agreement. The experimental LAC with its uncertainty compared with theoretical values is tabulated in Table 3.

Figure 7 compares the LAC for the different compositions at the examined energy levels. As expected, all the glass samples have the greatest LAC values at 0.0595 MeV, the lowest energy value. Sample BZBCu has a LAC value of 16.203 /cm, which is also the highest LAC value among all the studied glasses, this is as a result of the high density of this glass and due to the high atomic number of Cu. BZBA glass sample has a relatively low LAC and this is due to the low density of Al2O3. With a 0.0595 to 0.662 MeV energy increase, as shown in Fig. 7, we observed a great decrease in all the glass samples’ LAC values, with sample BZBCu experiencing the greatest decrease in LAC value from 16.203 cm−1 to 0.306 cm−1, while sample BZBA experiences the least decrease in LAC from 15.620 cm−1 to 0.302 cm−1. With a further 0.662 to 1.33 MeV energy increase, the decrease in the LAC values became lower, with sample BZBCu decreasing from 0.306 cm−1 to 0.206 cm−1 which was the highest observable decreased in LAC value due to the presence of CuO. Also, sample BZBFe which is the second highest observable decreased in the LAC due to the presence of Fe2O3 (this glass’s LAC reduces from 0.307 cm−1 to 0.208 cm−1). Hence samples BZBFe and BZBCu are the better candidate as a radiation attenuation material.

In Fig. 8, we plotted all the glasses’ transmission factor (TF) at 1 cm thickness against energy. When the incoming radiation was at very low energy (0.060 MeV), none of the glasses transmit the radiation and it was completely absorbed, as shown in Fig. 8, meaning the TF values of all the glasses were almost zero. Immediately as the radiation energy was increased to 0.662 MeV, the TF values increase significantly for all the glasses: for sample BZBCa its TF value increases 74.08%, which was the highest TF value increase due to the presence of Ca which has low atomic number; sample NZBM increases to 74.02%, sample BZBA increases to 73.97%, sample BZBT increases to 73.93%, followed by sample BZBCu which increases to 73.66%, and then the least increase was observed in sample BZBFe which increases to 73.57% due to the presence of Fe2O3. Further increase in the energy of the radiation from 0.662 MeV to 1.333 MeV shows a slow increase in the TF values for all the glasses and the TF for all glasses varied between 81.68% and 81.36%. The TF is very high at 1.333 MeV which means that most of the photons with high energy can penetrate these glasses.

Figure 9 shows the HVL for the prepared glasses. The HVL at a very low energy value of 0.060 MeV was very small across all the glass samples as seen in Fig. 9. At this energy, the HVL is almost 0.044 cm for the glasses and this indicated a very thin layer of these glasses can be successfully attenuating the low energy photons. We observed a sudden increase in the HVL values of all the glasses as the energy increases from 0.060 MeV to 0.662 MeV with sample BZBCa increasing to 2.310 cm, sample BZBM increases to 2.308 cm, sample BZBA increases to 2.299 cm, sample BZBT increases to 2.295 cm, sample BZBCu increases to 2.268 cm, while sample BZBFe increases to 2.258 cm which was observed to be the least increase. It is Cleary seen the difference in the thickness of the glass sample needs to attenuate the photons with low and high energy levels, a layer of 0.044 cm is required in the case of shielding low energy radiation, while we need a layer with thickness greater than 2 cm in case of shielding the photons with energy of 0.622 MeV. As the energy increases to 1.333 MeV, the thickness needed to attenuate the photons also increases and reached to around 3.5 cm. Within the range of the energy considered, sample BZBFe and BZBCu has the least increase in HVL which invariably makes these glasses good shielding material.

Based on Fig. 10, the MFP of the glass materials was very low at the lowest energy of the radiation (0.060 MeV) and this is the same trend reported to the HVL in the previous figure. At 0.06 MeV, the MFP is around 0.064 cm for the prepared glasses, increasing to around 3.258–3. 333 cm at 0.622 MeV. The MFP results have almost the same trend with the HVL and the difference only in the values. The MFP at 1.333 MeV is in order of 4.819 and 4.940 cm.

The required thickness of a glass sample that is capable of attenuating 90% of the incoming radiation was plotted in Fig. 11 against the energy of the radiation, and as expected, at a lower energy level of the radiation, 0.060 MeV, the required thickness is relatively low for all the glass samples. For example, sample BZBT and sample BZBCa have the same TVL value of 0.145 cm, sample BZBA and sample BZBFe also have the same TVL value of 0.147 cm, while sample BZBCu has a TVL value of 0.142 cm and lastly sample BZBM has a TVL value of 0.143 cm. We noticed a drastic increase in the TVL values across all the glass samples as we increased the energy from 0.060 to 0.662 MeV whereby sample BZBCa shows the highest increase in TVL value from 0.145 cm to 7.674 cm, sample BZBM increased from 0.143 to 7.654 cm, then sample BZBA which increased from 0.147 to 7.636 cm, sample BZBT increased from 0.145 to 7.623 cm, followed by sample BZBCu which increased from 0.142 to 7.532 cm and lastly sample BZBFe increased from 0.147 to 7.503 cm. The TVL values at 1.333 MeV are high and equal to 11.375 cm for BZBCa and 11.096 cm for BZBFe. As we found in the HVL, the TVL for BZBFe and BZBCu are lower than the TVL for the remaining glasses.

In Fig. 12, we plotted the RPE for the prepared glasses. As expected, all the glass samples under study are 100% efficient at the lowest energy value of 0.060 MeV as shown in Fig. 12. As the energy increases to 0.662 MeV, the RPE dropped suddenly, sample BZBM dropped to 25.98%, sample BZBCa dropped to 25.92%, sample BZBA dropped to 26.03%, sample BZBT dropped to 26.07%, sample BZBCu dropped to 26.34%, while sample BZBFe dropped to 26.43%. We observed further drops in the efficiency of the glasses as we increased the energy of the radiation from 0.662 MeV to 1.333 MeV; sample BZBM dropped to 18.36%, sample BZBCa dropped to 18.32%, sample BZBA dropped to 18.43%, sample BZBT dropped to 18.44%, sample BZBCu dropped to 18.64%, while sample BZBFe dropped to 18.74%. In all the energy range from 0.662 MeV to 1.333 MeV, sample BZBFe has the highest efficiency of attenuating the radiation as such is the best glass for radiation attenuation among the studied glasses.

The Zeff value was highest for all the glasses at the lowest energy of the radiation as presented in Fig. 13, 0.060 MeV; sample BZBM has a Zeff value of 47.23, sample BZBCa has a Zeff value of 47.13, sample BZBT has a Zeff value of 47.00, sample BZBCu has a Zeff value of 46.96, sample BZBA has a Zeff value of 46.92, while sample BZBFe has a Zeff value of 46.51. As we further increase the radiation’s energy from 0.060 MeV to 0.662 MeV, the Zeff values dropped significantly, sample BZBCu dropped to 14.03, sample BZBFe dropped to 13.99, sample BZBCa dropped to 13.89, sample BZBT dropped to 13.84, sample BZBM dropped to 13.78, while sample BZBA dropped to 13.62. As we increased the energy of the incoming radiation from 0.662 MeV to 1.333 MeV, the dropped in the Zeff values dropped gradually; sample BZBCu dropped to 13.46, sample BZBFe dropped to 13.44, sample BZBCa dropped to 13.33, sample BZBT dropped to 13.28, sample BZBM dropped to 13.21, while sample BZBA dropped to 13.07.

Finally, the fabricated glass in this work was compared with other commercial glasses such as RS 360 (45SiO2–45PbO–10K2O + N2O)43, RS 353 G18 (70SiO2–10B2O3–9K2O–8N2O–2C2O–1BaO)43, PbBaP5 (55PbO–5BaO–41P2O5)44 at 661.6 keV. The half value layer parameter was estimated in Fig. 14 as a comparison and the results in the figure indicated that the fabricated glasses can be used as a shielding material against gamma-rays, since it is better the barite concrete45 as a shielding material, where the HVL of Barite materials was 2.539 cm at 661.6 keV, while the HVL of fabricated glass ranges from 2.258 up to 2.301 cm.

Conclusion

The 45B2O3–20ZnO–30BaO–5X (where X represents CaO, MgO, Al2O3, CuO and Fe2O3) glass system’s gamma ray shielding performance was determined by experimental and theoretical techniques. The variation between the two techniques was very small in all discussed gamma energies. The BZBX- glass samples’ LAC was found and it was observed that the sample BZBCu experienced the greatest decrease in LAC value from 16.203 cm−1 to 0.306 cm−1, while sample BZBA experienced the least LAC decrease from 15.620 cm−1 to 0.302 cm−1 at 0.0595 MeV. With a further 0.662 to 1.33 MeV energy increase, the decrease in the LAC values became slower with sample BZBCu decreasing from 0.306 cm−1 to 0.206 cm−1, which was the highest observable reduction in LAC value due to the presence of CuO. Also, sample BZBFe which is the second highest observable decreased in the LAC due to the presence of Fe2O3. In the 0.662–1.333 MeV energy range, sample BZBFe has the highest efficiency of attenuating the radiation, and as such is the best glass for radiation attenuation among the studied glasses.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Saca, N., Radu, L., Fugaru, V., Gheorghe, M. & Petre, I. Composite materials with primary lead slag content: Application in gamma radiation shielding and waste encapsulation fields. J. Clean. Prod. 179, 255–265 (2018).

Waida, J. & Rilwan, U. A comparative analysis of Radon-222 concentration in water sources and its potential stomach and lungs doses: A case study of Borno State University Campus and its Environs. Nexus Future Mater. 1, 39–50 (2024).

Alawaideh, S. E. et al. Effect of different metal oxides on the radiation shielding features of borate glasses. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 220, 111720 (2024).

Almuqrin, A. H., Mahmoud, K. A., Rilwan, U., & Sayyed, M. I. Influence of various metal oxides (PbO, Fe2O3, MgO, and Al2O3) on the mechanical properties and γ-ray attenuation performance of zinc barium borate glasses. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 56, 2711–2717 (2024).

Hamad, M. K. Evaluation of photon shielding properties for new refractory tantalum-rich sulfides Ta9(XS3)2 alloys: A study with the MCNP-5. Ann. Nucl. Energy 184, 109687 (2023).

Hamad, M. K. Effects of bismuth substitution on the structural and ionizing radiation shielding properties of the novel BaSn1−xBixO3 perovskites: An experimental study. Mater. Chem. Phys. 308, 128254 (2023).

Sayyed, M. I., AlZaatreh, M. Y., Dong, M. G., Zaid, M. H. M. & Matori, K. A. A comprehensive study of the energy absorption and exposure buildup factors of different bricks for gamma-rays shielding. Results Phys. 7, 2528–2533 (2017).

Demir, I., Gümüs, M. & Gökçe, H. S. Gamma ray and neutron shielding characteristics of polypropylene fiber-reinforced heavyweight concrete exposed to elevated temperatures. Construct. Build. Mater. 257, 119596 (2020).

Aliyah, F., Kambali, I., Setiawan, A. F., Radzi, Y. M. & Rahman, A. A. Utilization of steel slag from industrial waste for ionizing radiation shielding concrete: A systematic review. Construct. Build. Mater. 382, 131360 (2023).

Linga, T.-C., Poona, C.-S., Lama, W.-S., Chanb, T.-P. & Fungb, K.-L. Utilization of recycled cathode ray tubes glass in cement mortar for X-ray radiation-shielding applications. J. Hazard Mater. 199–200, 321–327 (2012).

Chen, Q. et al. Influence of modifier oxide on the structural and radiation shielding features of Sm3+-doped calcium telluro-fluoroborate glass systems. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 57, 275–286 (2020).

Melo, G. H. A. et al. The effect of ZnO on the structural and radiation shielding properties in borophosphate glasses. Prog. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 618, 122528 (2023).

Ram, S., Chakravorty, D. & Bahadur, D. Effect of nucleating agents on the crystallisation behaviour of barium hexaferrite in a borate glass. J. Magn. Magn. Mat. 62, 221–232 (1986).

Ram, S. & Ram, K. IR and Raman studies and effect of γ radiation on crystallization of some lead borate glasses containing Al2O3. J. Mater. Sci. 23, 4541–4546 (1988).

Kumari, K., Ram, S. & Kotnala, R. K. Self-controlled growth of Fe3BO6 crystallites in shape of nanorods from iron-borate glass of small templates. Mater. Chem. Phys. 129, 1020–1026 (2011).

Ram, S. Infrared study of the dynamics of boroxol rings in the crystallization of BaFe12O19 microcrystals in borate glasses. Phys. Rev. B 51, 6280 (1995).

Ram, S. & Haldar, S. Medium-range structural ordering and macroscopic interactions in 1 to 2 mm thin two-dimensional platelets of borate glasses. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 195, 343–351 (1996).

Malidarre, R. B., Akkurt, I., Kocar, O. & Ekmekci, I. Analysis of radiation shielding, physical and optical qualities of various rare earth dopants on barium tellurite glasses: A comparative study. Prog. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 207, 110823 (2023).

Altowyan, A. S., Sayyed, M. I., Kumar, A. & Rashad, M. SrO–ZnO–PbO–B2O3 glassy insights: Unveiling the structural and optical features for gamma ray shielding efficacy. Opt. Mater. 152, 115534 (2024).

Sayyed, M. I., Hamad, D. & Rashad, M. The role of ZnO in the radiation shielding performance of newly developed B2O3–PbO–ZnO–CaO glass systems. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 223, 111896 (2024).

Fidan, M., Acikgoz, A., Demircan, G., Yilmaz, D. & Aktas, B. Optical, structural, physical, and nuclear shielding properties, and albedo parameters of TeO2–BaO–B2O3–PbO–V2O5 glasses. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 163, 110543 (2022).

Akçalı, O. et al. An investigation on gamma-ray shielding properties of quaternary glassy composite (Na2Si3O7/Bi2O3/B2O3/Sb2O3) by BXCOM and MCNP 6.2 code. Prog. Nucl. Energy 125, 103364 (2020).

Rajaramakrishna, R., Chaiphaksa, W., Kaewjaeng, S., Kothan, S. & Kaewkhao, J. Study of radiation shielding and luminescence properties of 1.5 μm emission from Er3+ doped zinc yttrium borate glasses. Prog. Opt. Int. J. Light Electron Opt. 289, 171273 (2023).

Abdel-Gawad, E. H., Sayyed, M. I., Hanafy, T. A. & Elsafi, M. Experimental investigation of radiation shielding competence of B2O3–Na2O–Al2O3–BaO–CaO glass system. Sci. Rep. 14, 14891 (2024).

Alasali, H. J., Rilwan, U., Mahmoud, K. A., Taha, A. & Hanafy, M. I. S. Comparative analysis of TiO2, Fe2O3, CaO and CuO in borate based glasses for gamma ray shielding. Nucl. Eng. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.net.2024.05.006 (2024).

Sayyed, M. I. et al. Exploring gamma radiation shielding: The role of BaO in borosilicate glasses. Silicon https://doi.org/10.1007/s12633-024-03045-1 (2024).

Guven, B., Ercenk, E. & Yilmaz, S. Investigation of radiation shielding properties of basalt-based glasses: Binodal/spinodal decomposition effect theory. Prog. Nucl. Energy 163, 104810 (2023).

Pacheco, M. H. et al. BaO–reinforced SiO2–Na2O–Ca(O/F2)–Al2O3 glasses for radiation safety: On the physical, optical, structural and radiation shielding properties. Prog. J. Alloys Compd. 960, 171019 (2023).

Wu, J. et al. Comparative investigation of physical, X-ray and neutron radiation shielding properties for B2O3–MnO2–CdO borate glasses. Prog. Ceram. Int. 49, 30915–30923 (2023).

Makishima, A. & Mackenzie, J. D. Direct calculation of Young’s modulus of glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 12(1), 35–45 (1973).

Pauling, L. The Nature of the Chemical Bond: And the Structure of Molecules and Crystals; An Introduction to Modern Structural Chemistry 450 (Cornell University Press, 1940).

Marzouk, S. Y., Seoudi, R., Said, D. A. & Mabrouk, M. S. Linear and non-linear optics and FTIR characteristics of borosilicate glasses doped with gadolinium ions. Opt. Mater. 35, 2077–2084 (2013).

Singh, D. et al. Optical and structural properties of ZnO–PbO–B2O3 and ZnO–PbO–B2O3–SiO2 glasses. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 20, 075228 (2008).

Rammah, Y. S., Sayyed, M. I., Ali, A. A., Tekin, H. O. & El-Mallawany, R. Optical properties and gamma-shielding features of bismuth borate glasses. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 124, 832 (2018).

Rammah, Y. S., Sayyed, M. I., Abohaswa, A. S. & Tekin, H. O. FTIR, electronic polarizability and shielding parameters of B2O3 glasses doped with SnO2. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 124, 650 (2018).

Mariselvam, K. & Liu, J. Concentration effect of Tm3+ ions doped B2O3–Li2CO3–BaCO3–CaF2–ZnO glasses: Blue laser and radiation shielding investigations. Prog. Opt. Laser Technol. 154, 108262 (2022).

Hanamar, K., Hiremath, G. B., Hegde, B. G., Ayachit, N. H. & Badiger, N. M. Effect of the samarium on the mechanical and radiation shielding capabilities of lead-free zinc-borate-lithium glasses. Prog. Opt. Int. J. Light Electron Opt. 273, 170397 (2023).

Zanganeh, V. Effect of WO3 addition on mechanical, structural, optical, and radiation shielding properties of lead boro phosphate glasses system using Monte Carlo simulation. Prog. Opt. Int. J. Light Electron Opt. 269, 169900 (2022).

Guntu, R. K. EPR-TL correlation, in radiation shielding Ba(10−x)MnxLa30Si60 glasses. Prog. J. Mol. Struct. 1248, 131533 (2022).

Sayyed, M. I., Abdel-Gawad, E. H., Hanafy, T. A. & Elsafi, M. Experimental evaluation of radiation shielding characteristics of borate-based-glass system reinforced with titanium oxide. Opt. Mater. 154, 115738 (2024).

Elsafi, M., Almousa, N., Almasoud, F. I., Alyahyawi, A. R. & Sayyed, M. I. A novel epoxy resin-based composite with zirconium and boron oxides: An investigation of photon attenuation. Crystals 12(10), 1370 (2022).

Sayyed, M. I., Yasmin, S., Almousa, N. & Elsafi, M. Shielding properties of epoxy matrix composites reinforced with MgO micro- and nanoparticles. Materials 15(18), 6201 (2022).

Speit, B. Radiation-Shielding Glasses Providing Safety Against Electrical Discharge and Being Resistant to Discoloration (Google Patents, 1991).

Kaur, K., Singh, K. & Anand, V. Correlation of gamma ray shielding and structural properties of PbO–BaO–P2O5 glass system. Nucl. Eng. Des. 285, 31–38 (2015).

Singh, K. et al. Gamma-ray shielding and structural properties of PbO–SiO2 glasses. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B 266(6), 944–948 (2008).

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Writing the first draft of the manuscript and reviewing-editing were performed by Mohamed. Elsafi, M. I. Sayyed and Taha. A. Hanafy. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elsafi, M., Sayyed, M.I. & Hanafy, T.A. Experimental study of different oxides in B2O3–ZnO–BaO glass system for gamma-ray shielding. Sci Rep 15, 2618 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85230-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85230-9