Abstract

The effectiveness of using vegetation to reinforce slopes is influenced by the soil and vegetation characteristics. Hence, this study pioneers the construction of an extensive soil database using random forest machine learning and ordinary kriging methods, focusing on the influence of plant roots on the saturated and unsaturated properties of residual soils. Soil organic content, which includes contributions from both soil organisms and roots, functions as a key factor in estimating soil hydraulic and mechanical properties influenced by vegetation roots. This innovative approach of using organic content to estimate soil properties performs well when applied to machine learning models for soil database development. The results reveal that organic content markedly affects the hydraulic properties of soils, more than their mechanical properties. The finding illustrates the importance of exploring the hydraulic effects of vegetation on slope stability in addition to the traditional emphasis on mechanical reinforcement. This rooted soil database has practical applications in GIS-based analyses for mapping regional slope stability, incorporating the role of plant roots. A case study demonstrated the database’s utility, showcasing that vegetation effectively limited rainwater infiltration and improved slope stability. Therefore, this research offers a valuable approach to improving slope stability through informed vegetation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rainfall-induced landslides pose increasingly significant threats to public safety and infrastructure stability, especially in areas where rainfall tends to become more intense as a result of climate change1,2,3. Most failed slopes consist of residual soils which are the in-situ products of the parent rocks4. Residual soils commonly exist in an unsaturated condition when the groundwater table (GWT) is deep5,6. Unsaturated soils have additional shear strength contributed by matric suction (i.e., the negative pore-water pressure), which decreases with an increase in moisture content7. Slope failures triggered by rainfall are attributed to the decrease in matric suction and the consequent decrease in soil shear strength when rainwater infiltrates from the soil slope surface7. The largest change in matric suction and shear strength occurs near the ground surface where infiltration starts to occur. As a result, rainfall-induced residual soil slope failure surfaces are typically shallow and generally have a depth of less than 2 m8,9,10,11. Moreover, Rahardjo et al.12 found that slope geometry and GWT positions are the secondary controlling factors for slope instability as compared to the soil permeability and rainfall characteristics (i.e., intensity and duration). Therefore, soil properties at shallow depths are of great importance in slope stability evaluation under varying rainfall conditions.

Furthermore, the necessity for conducting 3D analysis of slope failure becomes evident when there are lateral alterations in slope geometry. Emphasizing its paramount significance, the preferred and recommended approach for assessing slope stability involves employing a 3D analysis13,14,15,16. Beyond just geometry, various factors influencing slope stability, including soil characteristics, rainfall patterns, and groundwater table depths, exhibit considerable spatial variability within a given region17. Recent research endeavours have aimed to account for these variations by incorporating them as input map layers in physically based models integrated with geographic information systems (GIS)18,19,20,21,22. As seepage and slope stability analyses largely rely on the availability of soil properties, the development of a database for shallow depths of soil is therefore important for developing regional slope susceptibility maps23.

Compared to saturated soils, the presence of air in unsaturated soils results in their different hydraulic and mechanical properties. The unsaturated permeability and shear strength vary with matric suctions. As the loss of shear strength contributed by the matric suction has been proven to be the main cause of rainfall-induced slope failures, many studies have highlighted the importance of incorporating unsaturated soil properties in seepage and slope stability analyses21,24,25,26,27,28. In summary, the important saturated and unsaturated soil properties for seepage and slope stability analyses include saturated permeability (\({k}_{s}\)), soil–water characteristic curve (SWCC) which describes the relationship between the soil water content and the matric suction, effective cohesion (\(c^{{\prime}})\), effective friction angle (\(\phi^{{\prime}}\)) and an additional unsaturated shear strength parameter (\({\phi }^{b}\)) which indicates the rate of change in shear strength with respect to the matric suction29. However, a thorough search of the relevant literature yielded only a very limited number of studies that worked on the database incorporating unsaturated soil properties. This is because the development of a soil database usually involves laboratory testing data from a large number of soil samples. The measurements of unsaturated soil properties are much more costly and time-consuming than measurements of saturated soil properties in the laboratory30.

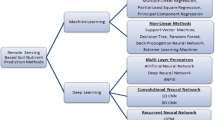

The most representative database is the Unsaturated Soil Hydraulic Database (UNSODA) which collected unsaturated hydraulic data from countries around the world and is free for downloading31. However, UNSODA contains very little data from regions other than Europe and North America. This limitation has given motivations for the use of pedotransfer functions (PTFs) to estimate the unsaturated hydraulic properties from the basic soil data32. The Global Soil Hydraulic Properties (GSHP) database33 is a recently developed global database that has applied PTFs on a collection of soil databases such as UNSODA and the hydrophysical database for Brazilian soils (HYBRAS)34, as well as additional data searched from available publications. GSHP has greatly increased data coverage to span all continents. However, there are still many areas such as tropical regions with poor data availability and data reliability. Nevertheless, the PTFs used to develop GSHP only considered soil texture while ignoring the effect of clay minerals and vegetation. This resulted in a low accuracy when predicting soil properties in tropical regions based on a large amount of temperate soil measurements33,35. Moreover, the linear regression PTFs may fail to capture the complicated relationship among the variables. Therefore, as computing capacities increase, machine-learning methods have attracted more attention in predicting both saturated and unsaturated hydraulic and mechanical soil properties such as \({k}_{s}\), SWCC, \(c^{{\prime}}\), \({\phi }^{{\prime}}\), and \({\phi }^{b}\)10,36,37,38,39.

Based on the soil properties of samples extracted from the field and tested in the laboratory, researchers have trained a random forest machine learning model and used it to predict the soil properties at additional locations where only basic soil properties are available in tropical areas10. The developed soil database includes the important saturated and unsaturated soil hydraulic and mechanical properties (i.e., \({k}_{s}\), SWCC, \(c^{{\prime}}\), \({\phi }^{{\prime}}\), and \({\phi }^{b}\)). In addition to collecting and predicting soil properties at scattered locations, Li et al.10 further adopted the ordinary kriging method to interpolate the values of each soil property at unsampled locations in Singapore. However, although the grain size distribution (GSD) and Atterberg Limits were considered in their machine learning model, the possible effect of vegetation on soil properties was ignored in the prediction of the soil properties.

Vegetation can be used to reinforce soil slopes mechanically and hydrologically40,41,42,43. Research comparing the soil–water characteristic curves (SWCCs) of bare and vegetated soils demonstrates alterations in soil water retention and saturated permeability44,45,46. Additionally, investigations into vegetation’s impact on soil shear strength reveal varying degrees of enhancement47,48. When comparing soil and soil with roots, researchers found that soil with roots has a substantially higher organic content (OC) than soil without roots49,50. Furthermore, Shi et al.51 found that root development increases the OC in the soil. Another study by Ni et al.52 which investigated the effect of plant roots on soil hydraulic properties found that the OC in the soil increased after 15 months of plant growth. Hence, results from previous studies demonstrate that as the root content in the soil increases, the organism content in the soils also rises, leading to an overall increase in OC. Therefore, the OC derived from igniting oven-dried soil with root samples in a furnace, comprising both root biomass and other organisms in the soil, is one of the factors that influence soil properties53. Higher OC typically leads to increased soil water retention capacity, especially in sandy soils54,55. On the other hand, the effect of OC on soil shear strength has conflicting results from the literature on peat soils. Gui et al.56 found that an increase in the OC resulted in a decrease in the soil shear strength with an increase in \(c^{{\prime}}\) and a decrease in \(\phi^{{\prime}}\). In contrast, researchers found that both \(c^{{\prime}}\) and \(\phi^{{\prime}}\) increased with OC though the study claimed that the data were not enough to establish a reliable relationship between organic content and \(\phi^{{\prime}}\)57. This is congruent with the previous findings based on a comparison of shear strength parameters between bare soil and root-soil mixtures in which roots showed more impacts on \(c^{{\prime}}\) but very limited and inconsistent effects on \(\phi^{{\prime}}\)48. The conflicting results from the previous studies can be explained by the reduction in soil density when OC increases57,58. Therefore, the change in soil density should be considered when predicting soil properties for root-soil mixtures with different OC. Hence, studies have shown that OC influences soil properties and should be incorporated as an input parameter when estimating soil properties using machine learning model. The application of OC in correlating soil properties with machine learning models and further developing a database for residual soils with roots is a novel approach to the best of the authors’ knowledge. This pioneering method not only evaluates vegetation’s impact on various soil properties but also addresses a critical gap in understanding how vegetation influences slope stability in the context of climate change. Recognizing the significant influence of vegetation on soil properties and the crucial role of unsaturated soil properties in water balance and slope stability analyses, this study embarked on creating a pioneering database. This database encompasses unsaturated soil properties of residual soils with varying levels of OC categorized as low, medium, and high. Figure 1 illustrates the scope of this study. This study first predicted soil properties for root-soil mixtures using the random forest (RF) method with the incorporation of OC and dry density in addition to GSD and Atterberg limits as input parameters. Then the spatial distributions of each soil property at the three OC levels were mapped using the ordinary kriging method (OK) and consequently a database for residual soils with roots was developed. A spatial map (Fig. 2) illustrates the slope locations with actual measurements obtained from laboratory testing of soil samples and predictions obtained from the machine learning model. The Kriging-estimated locations integrate both datasets, offering a more comprehensive representation of the spatial variability. Furthermore, this research incorporates a case study in a specific region of Singapore, focusing on regional water balance and slope stability analyses. The case study plays a pivotal role in the research by providing a comprehensive evaluation of the influence of vegetation on regional slope stability. It addresses a critical gap identified by Li and Duan59, where traditional regional analyses have prioritized mechanical reinforcement while often neglecting the hydrological impacts of vegetation on soil properties.

Locations of measurements and predictions used in machine learning and ordinary kriging. (software: ArcGIS Pro; version number: 3.1; URL: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview).

The effect of vegetation on soil properties and slope stability varies significantly depending on the type of residual soil slopes and the OC levels. In some instances, even with substantial root presence and high OC levels, factor of safety of slope may not improve significantly due to the unique characteristics of the vegetation and soil. Conversely, other residual soil slopes may respond effectively to stabilisation efforts. These variations underline the need for more informed and adaptable slope stabilisation strategies, particularly under changing climatic conditions. By integrating this innovative approach, the study aims to illuminate the broader, multifaceted impact of vegetation on slope stability. It emphasizes the importance of considering both hydraulic and mechanical factors in regional slope stability assessments, paving the way for more holistic and effective strategies.

Soil properties prediction

Description of predicting properties

Given the importance of both saturated and unsaturated soil properties in water balance and slope stability analyses, the saturated permeability (\({k}_{s}\)), soil–water characteristic curve (SWCC), effective cohesion (\(c^{{\prime}})\), effective friction angle (\(\phi^{{\prime}}\)) and an additional unsaturated shear strength parameter (\({\phi }^{b}\)) from laboratory experiments were collected. The soil samples include both residual soil and residual soil with roots. To present the SWCC, one of the most used best-fit equations proposed by Fredlund and Xing60 (Eq. 1) was adopted in this study:

where \(\theta\) is the calculated volumetric water content for a specified matric suction, \({\theta }_{s}\) is the saturated volumetric water content, \(\psi\) is the matric suction, \({\psi }_{r}\) is the parameter related to residual suction and recommended to be 1500 kPa for most residual soils61 and \(a\), \(n\), and \(m\) are fitting parameters.

Using SWCC and the saturated permeability (\({k}_{s}\)), the permeability function of unsaturated soils can be estimated29. On the other hand, the shear strength of unsaturated soils can be calculated using Eq. 27:

where \({u}_{a}\) is the pore-air pressure, \({u}_{w}\) is the pore-water pressure, \(\left(\sigma -{u}_{a}\right)\) is the net normal stress, and \(({u}_{a}-{u}_{w})\) is the matric suction.

Therefore, the saturated and unsaturated hydraulic properties for both residual soils and residual soils with roots can be represented by \({\theta }_{s}\), \(a\), \(n\), \(m\) and \({k}_{s}\) and are used for water balance analyses. The saturated and unsaturated mechanical properties for both residual soils and residual soils with roots can be represented by \({c}^{\prime}\), \({\phi }^{\prime}\) and \({\phi }^{b}\), and are used for slope stability analyses. \({\phi }^{b}\) does not have to be obtained from laboratory tests and can be estimated based on the unsaturated shear strength equations which do not require the \({\phi }^{b}\) angle62,63,64.

For some samples without \({\phi }^{b}\) measurements from the laboratory, unsaturated shear strength was estimated based on \({c}^{\prime}\), \({\phi }^{\prime}\), SWCC and plasticity index (PI)62. From the shear strength curve that plots shear strength versus matric suction, mean \({\phi }^{b}\) was calculated over a range until 100 kPa (when air entry value is larger than 100 kPa) or from the air entry value (AEV) to 100 kPa (when air entry value is smaller than 100 kPa). The maximum suction was limited to 100 kPa to keep consistent with the suction range used in the past laboratory tests to obtain the shear strength of soils. A past study measuring the soil suction across various sites in Singapore found the maximum suction to be less than 75 kPa65. Furthermore, past studies involving seepage analysis for residual soil slopes in Singapore, have limited the maximum suction to less than 100 kPa66,67. Thus, in the regional analyses, the initial maximum suction was also limited to 100 kPa to avoid unrealistically high suctions in shallower depths resulting from a deep GWT.

The studied soil properties include saturated permeability, shear strength parameters, and SWCC, with 46, 40, and 58 records, respectively. The soil samples were obtained from distributed residual soil slopes in Singapore that are located on four main geological formations in Singapore (Fig. 2). In particular, the four formations are Jurong Formation (JF) which consists of mainly sedimentary rocks and locates in the west and south-west, Bukit Timah Granite Formation (BTG) which consists of mainly igneous rocks and is located in the north and central-north, Old Alluvium (OA) and Kallang Formation (KF) which mainly consist of quaternary and alluvial deposits and are located in the east68. Due to the coverage of a wide range of values, the saturated permeability \({k}_{s}\) and SWCC fitting parameter \(a\) were transformed to log(\({k}_{s})\) and log(\(a)\) respectively, to achieve a better model performance10. To predict these properties, five basic soil properties (i.e., dry density, sand and fines fractions, PI, and OC) were incorporated as inputs. Figure 3 presents the boxplots for the five basic properties of soil samples from the different formations. Though dry density of soil could be ignored in the prediction for unsaturated properties for residual soils without roots10, it could be an important factor and was incorporated in this study to consider the significant variation of dry density for residual soils with and without roots57,58. For rooted samples, soil was collected from a depth of less than 30 cm below the soil surface. In contrast, for residual soil samples without root presence and no OC measurements, an OC value of 0 was assigned to represent negligible contributions from roots and organic matter.

Before establishing the relationship between the input and output soil properties, Pearson correlation analyses were carried out to quantify the strength of the correlation between each input and output. A correlation coefficient that is closer to 1 or − 1 shows a stronger correlation while a value closer to 0 reflects a weaker correlation between the two parameters. A positive correlation indicates the two variables tend to increase or decrease together while a negative correlation implies an increase in one variable is likely to be observed with a decrease in the other variable. However, some correlations do not have a confidence level of 95% and may not be statistically significant, thus the obtained correlations are not meaningful. The resulting correlation coefficients for each input and output are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1 shows that only sand or fines fractions are significantly correlated with log(\({k}_{s}\)). The correlation between either of them and SWCC or shear strength parameters is weak and insignificant. In comparison, PI or OC has a stronger and more significant correlation with SWCC than with the shear strength parameters or log(\({k}_{s}\)). Masi et al.69 also claimed that OC had no significant correlation with the saturated permeability. In comparison, the correlation between OC and the saturated volumetric water content \({\theta }_{s}\) is very strong with a coefficient of 0.7, which agrees with the existing findings that indicated soils with roots had a higher water retention capacity than soils without roots70,71,72. On the other hand, compared to other inputs, dry density or OC have a stronger and more significant correlation with \({\phi }^{\prime}\). An increase in OC is correlated to a decrease in \({\phi }^{\prime}\), which seems to contradict the findings that OC had a weak but positive correlation with \({\phi }^{\prime}\)69 or roots had a very limited impact on the friction angle as compared to the cohesion of soil47,48. However, Khaboushan et al.73 also claimed that shear strength parameters \({\phi }^{\prime}\) and \({\phi }^{b}\) had a negative correlation with OC and a positive correlation with \({c}^{\prime}\), though none of these correlations were statistically significant. Nevertheless, it should be noted that correlation does not provide any insight into causation and a negative correlation between OC and \({\phi }^{\prime}\) does not imply that higher OC results in a lower \({\phi }^{\prime}\). The correlation only examines the relationship between two variables or univariate data while ignoring the change in other variables such as dry density at the same time. An increase in dry density was also observed with a decrease in \({\phi }^{\prime}.\) Overall, by evaluating the linear relationship between each input and output, it was found that all the inputs have a strong correlation with some of the outputs (i.e., saturated permeability, SWCC or shear strength parameters). Meanwhile, the correlation between any of the inputs and \({c}^{\prime}\) or \({\phi }^{b}\) was observed as weak and insignificant in general. Thus, further investigations on the multivariant and nonlinear relationship are required.

Random forest model performance

To investigate the nonlinear relationship between input and output soil properties, RF machine learning model was used in this study as it was the recommended regression model for a limited data volume and has shown good performance when predicting soil properties in previous studies10,74. RF is an ensemble method with a collection of decision trees as estimators and the final prediction is the average of the predicted values from all the estimators that work in parallel75. As user-defined hyperparameters were involved in establishing the model, a five-fold cross-validation method was used in the hyperparameter tuning process to select the most appropriate settings for better generalisation performance on unseen data.

When predicting SWCC, a multioutput model was used as suggested by Li et al.10 to take the fitting parameters into account simultaneously. When predicting shear strength parameters and saturated permeability, single output models were established. In total, four single output models and a multioutput model were trained using the available data to detect the relationship between the output soil properties and the five input parameters (i.e., dry density, sand and fines fractions, PI, and OC). The training data consisted of 80% of the total data while the remaining 20% was used for testing the trained model. To evaluate the model performance, the mean absolute error (MAE), the root mean square error (RMSE), and R2 were calculated. Figure 4 compares the predicted and measured soil properties. A 1:1 reference line was also plotted in each subplot to indicate a perfect prediction which is equal to the measurement. The MAE, RMSE, and R2 metrics were also summarised in the plots. The figure shows that the data points are in trend with the reference line and the predictions are close to the measurement values. The MAE and RMSE of \({\phi }^{b}\) are relatively high, at 3.1° and 4.1°, respectively, with an R2 value of 0.59, indicating its inherent variability. This variability arises because the relationship between shear strength and matric suction is not linear. The value of \({\phi }^{b}\) is therefore not a constant but dependent on matric suction. Consequently, Vanapalli et al.63 suggested using normalised water content (i.e., \(\left[(\frac{\theta -{\theta }_{r}}{{\theta }_{s}-{\theta }_{r}})(tan {\phi }^{\prime})\right]\) ) and effective friction angle to estimate shear strength instead of using \({\phi }^{b}\). In this study, \({\phi }^{b}\) was included in the database as a reference value. For the slope stability analyses conducted with Scoops3D software in the case study, normalized water content and the effective friction angle was employed. The 95% confidence interval bounds, shown alongside the true and predicted values in the appendix (Figure A1), highlighting the prediction reliability. The predicted values largely fall within these bounds, reflecting the model’s ability to capture data variability and ensuring confidence in its accuracy.

Database development for residual soils with roots

With the established RF models, soil properties (i.e., saturated permeability, SWCC, and shear strength parameters) were then predicted for residual soil with roots. Three levels of OC (low, medium, and high) were defined based on the available OC measurements from soil samples containing roots. The 1st, 2nd, and 3rd quartiles of the OC measurements (OC = 4.1%, 6.2%, and 10.8%, respectively) were used to represent these three levels. Each of the three OC values, along with the other measured parameter values were used as the inputs to predict the soil properties. In this study, the changes in parameter values were predicted based on varying OC levels while keeping other basic soil properties constant, using the trained and validated machine learning model. The residual soil samples from 0 to 2 m depth with input soil properties available were filtered out. The saturated and unsaturated properties of residual soil with roots were then predicted. The database was developed for soils with roots at shallow depths given that the rainfall-induced slope failures mostly have a depth of less than 2 m8,9,10,11.

As the predicted properties of soils with roots are only at the discrete locations where the input properties are available, the ordinary kriging method76 was used to spatially interpolate the predicted soil properties to obtain continuous distributions of soil properties within the region. This approach employed a spherical model and was implemented using the Geostatistical Wizard in ArcGIS Pro. Cross-validation was conducted during the interpolation process to enhance accuracy and reliability. Based on the similarity of soil properties for residual soils from 0 to 2 m depth, the entire region was divided into a total of 97 zones10. The same 97 zones were adopted in this study to develop the database for soil with roots. From the distribution of each soil property that was obtained using the ordinary kriging method, the mean value of each zone was calculated to represent the corresponding property for residual soil with roots. Specifically, the mean values for each zone at different OC levels are displayed in Fig. 5. Additionally, a detailed summary of the mean properties for each zone is provided in Appendix A, Table A1.

Mapping the developed database of saturated and unsaturated soil hydraulic and mechanical properties in each zone of Singapore. (software: ArcGIS Pro; version number: 3.1; URL: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview).

Regional analyses

Study area

To evaluate the impact of the vegetation as represented by the OC in the soil on the pore-water pressure changes and factor of safety of slopes, regional seepage and slope stability analyses were carried out on a zone (i.e., Zone 38) located in Bukit Timah Granite formation as a case study. Regional seepage analyses were performed using the distributed three-dimensional (3D) water balance model, GEOtop77,78. The GEOtop model incorporates the principles of energy and water fluxes to perform a regional water balance analysis while incorporating the effect of rainfall infiltration, subsurface water flow and surface run-off. The volumetric water content and pore-water pressure results from the water balance analyses were then imported to Scoops3D79 for the three-dimensional (3D) slope stability analyses. The Scoops3D software was developed by U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and has the ability to calculate the slope stability using 3D limit equilibrium methods such as Bishop’s Simplified method for complex topographies.

A rainfall intensity of 22.2 mm/hour was applied for 24 h in the water balance analyses following the guidelines from the Public Utilities Board (PUB) Code of Practice on Surface Water Drainage80. Thereafter, another 24 h of no rainfall was applied. There are four input maps (i.e., Digital Elevation Model (DEM), Slope angle, Aspect, Groundwater table) with a resolution of 5 m by 5 m presented in Fig. 6 that are required to define the three-dimensional topography and the groundwater table configuration of Zone 38 in the water balance analysis. The slope angle and aspect maps were generated using the Spatial Analyst tools in ArcGIS using the DEM81. The DEM was used for the slope stability analysis has a resolution of 1 m by 1 m. A lower resolution of 5 m input maps had to be used for the water balance analysis due to the computational limitation of the GEOtop model.

Input Maps of Zone 38 for Water Balance Analyses (a) DEM; (b) Slope Angle; (c) Aspect; (d) Groundwater table. (software: ArcGIS Pro; version number: 3.1; URL: https://www.esri.com/en-us/arcgis/products/arcgis-pro/overview).

Soil properties for Zone 38

The Fredlund and Xing SWCC parameters from the developed database for residual soils with roots were best fitted to obtain the van Genuchten82 best-fitting parameters \({a}_{vg}\) and \({n}_{vg}\) which are necessary inputs to define the van Genuchten SWCC and permeability function in the GEOtop model. Table 2 summarises the respective hydraulic and shear strength properties of Zone 38 required for the numerical analyses. Comparing the percentage increase between low and high OC, the increased presence of roots resulted in a decrease in saturated permeability of the soil by 23.3%. However, the shear strength properties such as the effective cohesion increased by a smaller percentage of 7.4%. Therefore, the soil database results for Zone 38 demonstrates that the OC in the soil has a greater influence on the hydraulic properties rather than the mechanical properties of the soil. In Scoops3D, the shear strength equation from Vanapalli et al.63 was utilised to estimate the shear strength contributed by the matric suction based on the normalized water content instead of using \({\phi }^{b}\) angle (Eqs. 3 and 4). Total cohesion \(C\) was used to represent the sum of the effective cohesion and the additional cohesion due to the matric suction7 (Eqs. 4). As the soil reaches a saturated state, the total cohesion will equal the effective cohesion as matric suction is zero.

where and \({\theta }_{r}\) is the residual water content and \((\frac{\theta -{\theta }_{r}}{{\theta }_{s}-{\theta }_{r}})\) is the normalized water content.

Pore-water pressure and slope stability changes

The pore-water pressure results from the water balance analyses are presented in Fig. 7. The difference in pore-water pressures between the different OC levels is minimal at the start of the rainfall (i.e., at 1st hour). However, the difference between low, medium and high OC becomes more apparent after a 24-h continuous rainfall. When rainfall stops, the difference in pore-water pressures between different OC levels decreases and is minimal again at the end of the drying period (i.e., at 48th hour). The high and medium OC soils have a smaller change in pore-water pressure than the low OC soil, especially at the end of the rainfall at 24th hour. Moreover, the high and medium OC soils remain unsaturated between the 0.75 m depth to the groundwater table while the low OC soil experiences positive pore-water pressures throughout the entire soil layer. This is due to the saturated permeability of high and medium OC soils being lower than those of the low OC soil as seen in Table 2. The low permeability of high and medium OC soils reduces the amount of rainfall infiltration, resulting in a smaller increase in pore-water pressure at the end of the rainfall at the 24th hour.

The factor of safety (FOS) is a number that represents the stability of slopes and is calculated by taking the ratio of the resisting moment over the driving moment. A factor of safety less than 1 would indicate slope failure as the resisting forces are less than the driving force. The percentage of pixels with a low factor of safety (FOS < 1.5) was calculated for the three different OC soils. This was achieved by calculating the number of pixels having a FOS less than 1.5 and thereafter dividing by the total number of pixels of Zone 38. The results are presented in Fig. 8. There is an increase in the number of pixels with a low factor of safety (FOS < 1.5) during the rainfall period between the 1st and 24th hour and thereafter it decreases during the no rainfall period between the 24th and 48th hour as observed in Fig. 8. This is due to the increase in pore-water pressures during the 1st and 24th hour and a decrease in pore-water pressure between the 24th and 48th hour as observed in Fig. 7.

Discussion

Influence of organic content on slope stability in Zone 38

Generally, the percentage of pixels with a low factor of safety (FOS < 1.5) is lower as the OC is higher with the high OC soil having the lowest percentage of pixels with FOS < 1.5. The high OC soil has the lowest increase in the percentage of pixels with low FOS at the end rainfall (from 0.2 to 1.2%) as compared to those of the low (from 0.3 to 2.8%) and medium OC soils (from 0.2 to 1.5%). This trend can be attributed to the increase in total cohesion and decrease in saturated permeability as the OC of the soil increases. The total cohesion, C (Eq. 4) was calculated for the different OC soils as seen in Fig. 9. The total cohesion for the high OC soil is always higher than the total cohesion for low and medium OC soil. Moreover, the total cohesion for the high OC soil at the end of the rainfall is higher for depths between 0.75 and 6 m as compared to that of the low OC soil. Therefore, the shear strength and factor of safety for high OC soil is higher resulting in a lower percentage of pixels with a low factor of safety. In terms of soil properties between low OC and high OC (Table 2), the increased presence of roots in the soil led to a 23.3% decrease in the saturated permeability while effective cohesion experienced a comparatively smaller increase of 7.1%. Hence, the 56% reduction in percentage areas with low factor of safety between low OC and high OC can be attributed to the decrease in permeability of the soil. As the permeability decreases, the amount of rainfall infiltration decreases, thus reducing the changes in pore-water pressures and shear strength of the soil. As such, it can be concluded that soils with high OC level are more effective in limiting rainfall infiltration thus improving the stability of slopes.

Influence of input parameters on output soil properties

With the established RF models, further sensitivity analyses were carried out by calculating the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) values to estimate the change in the output soil properties resulting from a change in the input83. The SHAP values are different from correlation coefficients which only represent the strength of a linear relationship between two variables. A strong correlation does not give any insights into the impact of one on the other. An input may have a strong correlation with the output but has a very limited impact on the output at the same time. In comparison, the SHAP values reflect the different impacts of each input parameter on the output soil properties. The advantage of SHAP is that it can incorporate the interactions among the inputs which provide a more reliable evaluation of the impact. For example, SHAP incorporates the concurrent change in fines fraction with an observed change in sands fraction instead of solely changing the value of one input while ignoring the concurrent changes in other parameters.

The calculated SHAP values of each input parameter on the output soil properties are illustrated in Fig. 10. A higher impact is represented by a higher SHAP value. The two correlation coefficients for input parameters that most strongly affect each output soil property were bolded in Table 3 together with the correlation results. Overall, the input parameters that have stronger correlations also have higher impacts on the output soil properties. For example, PI and OC have a stronger correlation with and a higher impact on SWCC. However, there are some cases when two variables have no linear correlation detected, but one has a high impact on the other. In particular, there is no correlation between sand fraction and \({\phi }^{\prime}\) but sand fraction has a high impact on \({\phi }^{\prime}\). The correlation between the two variables failed to be captured because changes in other variables were not considered. A higher sand fraction was observed together with a higher \({\phi }^{\prime}\) when the dry density was higher and a lower \({\phi }^{\prime}\) when the dry density was lower. If only sand fraction and \({\phi }^{\prime}\) were incorporated, no linear correlation could be found since \({\phi }^{\prime}\) may increase or decrease with an increase in sand fraction. Therefore, SHAP values provide more significance in terms of parameter impact. Among all the input parameters, OC has a high impact on most of the output soil properties (i.e., \({\theta }_{s}\), \(a\), \(n\), \(m\) \({k}_{s}\), and \({\phi }^{b}\)). Therefore, in addition to the identified key inputs like PI, dry density, as well as sand and fines fractions, incorporating the influence of roots on residual soil properties is important.

Impact of organic content on soil properties across four geological formations in Singapore

Figure 11 illustrates the boxplots comparing changes in each property across different OC levels for the zones in the four formations. In general, an increase in OC leads to an increase in \(a\), \(m\), \({\theta }_{s}\), \({\phi }^{b},\) a slight increase in \({c}^{\prime}\), a decrease in \({k}_{s}\), and a negligible reduction in \({\phi }^{\prime}\). Specifically, the SWCC fitting parameter \(a\) was observed to increase with higher OC levels, particularly when OC increased from medium to high (Fig. 5A). Fredlund and Xing60 found that \(a\) was closely related to the air-entry value (AEV) of soil, which is the suction when air starts to occupy the largest pores in the soil during desorption. Therefore, the increase in \(a\) with OC is consistent with previous research findings in which soil with roots had a higher air-entry value (AEV) compared to the residual soils71,84. Nevertheless, a reduction in \(a\) was also identified in several JF zones in the southwest and a similar reduction in AEV was also found by Jotisankasa and Sirirattanachat85. At the same time, the fitting parameters \(m\), as well as the saturated volumetric water content \({\theta }_{s}\), also increased with OC in general. Due to the existence of roots that occupied some pore spaces, there was less space for water flow and a decrease in the saturated permeability \({k}_{s}\) was found as OC increased, which was also reported by Rahardjo et al.46 and Ni et al.52. Regarding shear strength parameters, soils with higher OC levels or more roots exhibited a slight increase in effective cohesion \({c}^{\prime}\). However, OC had minimal impact on \({\phi }^{\prime}\), consistent with findings in the literature47,48. Notably, an increase in \({\phi }^{b}\) was observed when OC increased from low to medium levels. Some studies also found a higher \({\phi }^{b}\) for soils with roots than soils without roots50.

Limitations and recommendations

This study identifies OC as a critical factor influencing soil hydraulic and mechanical properties, derived from both root biomass and other organic matter present in the soil. It assumes that higher root biomass corresponds to greater contributions from other organic sources. Consequently, for residual soil samples without root presence and no OC measurements, an OC value of 0 was assigned to represent negligible organic contributions. This approach introduces limitations, particularly in areas where soil conditions may vary significantly beyond the assumed parameters.

Additionally, the study assumes homogeneity of soil properties across depths. Variations in root architecture and root distribution with depth, which are critical factors influencing soil behaviour, were not considered, potentially simplifying the results. Furthermore, the study is focused on Singapore’s tropical climate, characterised by minimal seasonal variations, making the findings more applicable to plants with persistent foliage rather than those with higher proportions of decayed leaves. While this regional specificity limits the generalisability of the results to regions with differing climatic or seasonal conditions, the methodology presented offers a valuable framework that can be adapted and applied to other parts of the world.

Moreover, the dataset included 19 samples from JF, 11 from BTG, 37 from OA, and 3 from KF, with an uneven distribution across geological formations. This imbalance in sample representation may impact the machine learning model’s ability to accurately predict soil properties in zones with fewer data points. Additionally, not all samples underwent comprehensive laboratory testing; some included only one or two parameters, such as saturated permeability \({k}_{s}\), shear strength, or SWCC. This variability in the available data across soil properties could reduce the overall reliability of the results.

To address the identified limitations, future studies should collect a more balanced and extensive dataset that includes an even representation across geological formations and a broader range of OC levels. Comprehensive laboratory testing of all samples to measure a complete set of hydraulic and mechanical properties is recommended to improve data consistency. Additionally, incorporating detailed analyses of root architecture and root distribution with depth would provide a more accurate understanding of their influence on soil behaviour. Expanding the study to regions with varying climatic and seasonal conditions could enhance the generalisability of the methodology. Furthermore, integrating advanced machine learning techniques and refining the model with a larger dataset would improve the predictive accuracy of soil properties in zones with limited data.

Conclusions

This study successfully developed a comprehensive database for soils within a depth of 0–2 m in Singapore, encompassing both saturated and unsaturated hydraulic and mechanical properties. It incorporates the novel use of OC as an influencing factor in estimating soil properties using machine learning models. The OC consists of both root biomass and soil organisms, both of which increases with vegetation. This reflects the effect of vegetation on the soil properties and can be used as an input parameter to estimate and influence soil properties. The database includes key parameters such as saturated permeability, SWCC, and shear strength parameters, categorized across three OC levels. Utilizing RF machine learning method, the study first estimated these soil properties at various locations. The ordinary kriging method was then employed to interpolate these properties for continuous spatial distributions across Singapore. The inclusion of OC and dry density, along with GSD and PI, underscores the multifaceted impact of roots on soil properties. OC emerged as a highly influential factor, affecting most soil properties. The mean properties of soil with roots at the three OC levels from each of the divided 97 zones were calculated to represent the zonal soil properties in the database. Soils with higher OC levels tend to have higher water retention capacity, lower permeability, higher \({c}^{\prime}\) and \({\phi }^{b}\) but a similar \({\phi }^{\prime}\). The database’s distinct feature is its ability to integrate the influence of root biomass on soil hydrological and mechanical properties, offering new insights into vegetation’s role in altering pore-water pressure and slope stability. This is particularly evident in the case study focusing on a specific zone in Singapore, where increased OC levels corresponded to reduced saturated permeability and enhanced total cohesion, leading to improved slope stability, especially in high OC soils.

Therefore, by implementing a database that incorporates the influence of vegetation on soil properties in regional analyses, users can gain valuable insights into the extent to which vegetation can act as a slope stabilisation measure, or whether its effects are limited, suggesting the need to consider other measures for slope stability. Moreover, it is possible that the extent of the influence of OC level on slope stability could vary for different zones with different soil properties. To create effective guidelines for using vegetation to stabilize slopes in a region, it is important to map the potential impact of vegetation on slope stability in that specific area. The case study has shown a successful implementation of the developed database for soil with roots in the regional slope stability assessment. Similar workflows can be used for database development for soils with roots in other regions as well. The regional mapping of the potential effect of vegetation on slope stability will play an important role in the guideline on how vegetation should be used as an effective measure for regional slope stability. This regional mapping will provide valuable information that can be used to determine the most effective ways to utilise vegetation for slope stabilisation purposes.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study will be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Gariano, S. L. & Guzzetti, F. Landslides in a changing climate. Earth Sci. Rev. 162, 227–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earscirev.2016.08.011 (2016).

Lin, Q. & Wang, Y. Spatial and temporal analysis of a fatal landslide inventory in China from 1950 to 2016. Landslides 15, 2357–2372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-018-1037-6 (2018).

Seneviratne, S. et al. Changes in climate extremes and their impacts on the natural physical environment. 109–230 https://doi.org/10.7916/d8-6nbt-s431 (2012).

Li, Y., Satyanaga, A., Rangarajan, S., Rahardjo, H. & Lee, D.T.-T. Unsaturated properties of singapore urban soils. In Soils in urban ecosystem (eds Rakshit, A. et al.) 321–335 (Springer, Singapore, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-8914-7_15.

Lim, T. T., Rahardjo, H., Chang, M. F. & Fredlund, D. G. Effect of rainfall on matric suctions in a residual soil slope. Can. Geotech. J. 33, 618–628 (1996).

Rahardjo, H., Lee, T. T., Leong, E. C. & Rezaur, R. B. Response of a residual soil slope to rainfall. Can. Geotech. J. 42, 340–351. https://doi.org/10.1139/t04-101 (2005).

Fredlund, D. G., Morgenstern, N. R. & Widger, R. A. The shear strength of unsaturated soils. Can. Geotech. J. 15, 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1139/t78-029 (1978).

Bordoni, M. et al. Hydrological factors affecting rainfall-induced shallow landslides: From the field monitoring to a simplified slope stability analysis. Eng. Geol. 193, 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2015.04.006 (2015).

Cho, M. T. T., Chueasamat, A., Hori, T., Saito, H. & Kohgo, Y. Effectiveness of filter gabions against slope failure due to heavy rainfall. Soils Foundat. 61, 480–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2021.01.010 (2021).

Li, Y., Rahardjo, H., Satyanaga, A., Rangarajan, S. & Lee, D.T.-T. Soil database development with the application of machine learning methods in soil properties prediction. Eng. Geol. 306, 106769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2022.106769 (2022).

Rahardjo, H., Li, X. W., Toll, D. G. & Leong, E. C. The effect of antecedent rainfall on slope stability. In Unsaturated soil concepts and their application in geotechnical practice (ed. Toll, D. G.) 371–399 (Springer, Dordrecht, 2001). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-9775-3_8.

Rahardjo, H., Ong, T. H., Rezaur, R. B. & Leong, E. C. Factors controlling instability of homogeneous soil slopes under rainfall. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 133, 1532–1543. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(2007)133:12(1532) (2007).

Kumar, S., Choudhary, S. S. & Burman, A. Recent advances in 3D slope stability analysis: A detailed review. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 9, 1445–1462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-022-01597-y (2023).

Leong, E. C. & Rahardjo, H. Two and three-dimensional slope stability reanalyses of Bukit Batok slope. Comput. Geotech. 42, 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2012.01.001 (2012).

Xie, M., Wang, Z., Liu, X. & Xu, B. Three-dimensional critical slip surface locating and slope stability assessment for lava lobe of Unzen volcano. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 3, 82–89. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1235.2011.00082 (2011).

Xie, M., Esaki, T., Qiu, C. & Wang, C. Geographical information system-based computational implementation and application of spatial three-dimensional slope stability analysis. Comput. Geotech. 33, 260–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2006.07.003 (2006).

Wang, B., Liu, L., Li, Y. & Jiang, Q. Reliability analysis of slopes considering spatial variability of soil properties based on efficiently identified representative slip surfaces. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 12, 642–655. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2019.12.003 (2020).

Rahardjo, H., Li, Y. & Satyanaga, A. The importance of unsaturated soil properties in the development of slope susceptibility map for old alluvium in Singapore. in Proceedings of 8th International Conference on Unsaturated Soils (UNSAT 2023), 2–5 May 2023, Milos, Greece (2023).

He, J. et al. Prediction of spatiotemporal stability and rainfall threshold of shallow landslides using the TRIGRS and Scoops3D models. CATENA 197, 104999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2020.104999 (2021).

Sarma, C. P., Dey, A. & Krishna, A. M. Influence of digital elevation models on the simulation of rainfall-induced landslides in the hillslopes of Guwahati, India. Eng. Geol. 268, 105523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2020.105523 (2020).

Satyanaga, A. & Rahardjo, H. Role of unsaturated soil properties in the development of slope susceptibility map. Proceed. Institut. Civil Eng. – Geotech. Eng. 175, 276–288. https://doi.org/10.1680/jgeen.20.00085 (2022).

Weidner, L., DePrekel, K., Oommen, T. & Vitton, S. Investigating large landslides along a river valley using combined physical, statistical, and hydrologic modeling. Eng. Geol. 259, 105169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2019.105169 (2019).

Ip, S. C. Y., Rahardjo, H. & Satyanaga, A. Three-dimensional slope stability analysis incorporating unsaturated soil properties in Singapore. Georisk: Assess Manag. Risk Eng. Syst. Geohaz. 15, 98–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/17499518.2020.1737880 (2021).

Cho, S. E. & Lee, S. R. Instability of unsaturated soil slopes due to infiltration. Comput. Geotech. 28, 185–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0266-352X(00)00027-6 (2001).

Ng, C. W. W. & Shi, Q. Influence of rainfall intensity and duration on slope stability in unsaturated soils. Quarterly J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 31, 105–113 (1998).

Ng, C. W. W., Qu, C., Ni, J. & Guo, H. Three-dimensional reliability analysis of unsaturated soil slope considering permeability rotated anisotropy random fields. Comput. Geotech. 151, 104944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2022.104944 (2022).

Rahardjo, H., Kim, Y. & Satyanaga, A. Role of unsaturated soil mechanics in geotechnical engineering. Geo-Eng. 10, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40703-019-0104-8 (2019).

Tsaparas, I., Rahardjo, H., Toll, D. G. & Leong, E. C. Controlling parameters for rainfall-induced landslides. Comput. Geotech. 29, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0266-352X(01)00019-2 (2002).

Fredlund, D. G. & Rahardjo, H. Soil mechanics for unsaturated soils (Wiley, 1993). https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470172759.

Fredlund, D. G. & Houston, S. L. Protocol for the assessment of unsaturated soil properties in geotechnical engineering practice. Can. Geotech. J. 46, 694–707. https://doi.org/10.1139/T09-010 (2009).

Nemes, A., Schaap, M. G., Leij, F. J. & Wösten, J. H. M. Description of the unsaturated soil hydraulic database UNSODA version 2.0. J. Hydrol. 251, 151–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1694(01)00465-6 (2001).

Wösten, J. H. M., Pachepsky, Y. A. & Rawls, W. J. Pedotransfer functions: bridging the gap between available basic soil data and missing soil hydraulic characteristics. J. Hydrol. 251, 123–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1694(01)00464-4 (2001).

Gupta, S. et al. Global soil hydraulic properties dataset based on legacy site observations and robust parameterization. Sci. Data 9, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01481-5 (2022).

Ottoni, M. V., Ottoni Filho, T. B., Schaap, M. G., Lopes-Assad, M. L. R. C. & Rotunno Filho, O. C. Hydrophysical database for Brazilian soils (HYBRAS) and pedotransfer functions for water retention. Vadose Zone J. 17, 170095. https://doi.org/10.2136/vzj2017.05.0095 (2018).

Tomasella, J., Hodnett, M. G. & Rossato, L. Pedotransfer functions for the estimation of soil water retention in Brazilian soils. Soil Sci. Soci. Am. J. 64, 327–338. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2000.641327x (2000).

Kim, Y., Satyanaga, A., Rahardjo, H., Park, H. & Sham, A. W. L. Estimation of effective cohesion using artificial neural networks based on index soil properties: A Singapore case. Eng. Geol. 289, 106163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2021.106163 (2021).

Lin, P. et al. Mapping shear strength and compressibility of soft soils with artificial neural networks. Eng. Geol. 300, 106585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2022.106585 (2022).

Pham, B. T. et al. Extreme learning machine based prediction of soil shear strength: A sensitivity analysis using monte Carlo simulations and feature backward elimination. Sustainability 12, 2339. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12062339 (2020).

Singh, V. K. et al. Modelling of soil permeability using different data driven algorithms based on physical properties of soil. J. Hydrol. 580, 124223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2019.124223 (2020).

Li, Y., Satyanaga, A. & Rahardjo, H. Characteristics of unsaturated soil slope covered with capillary barrier system and deep-rooted grass under different rainfall patterns. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 9, 405–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iswcr.2021.03.004 (2021).

Ni, J. J., Leung, A. K., Ng, C. W. W. & Shao, W. Modelling hydro-mechanical reinforcements of plants to slope stability. Comput. Geotech. 95, 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2017.09.001 (2018).

Liu, H. W., Feng, S. & Ng, C. W. W. Analytical analysis of hydraulic effect of vegetation on shallow slope stability with different root architectures. Comput. Geotech. 80, 115–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2016.06.006 (2016).

Bella, G., Barbero, M., Barpi, F., Borri-Brunetto, M. & Peila, D. An innovative bio-engineering retaining structure for supporting unstable soil. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 9, 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2016.12.002 (2017).

Leung, A. K. et al. Plant age effects on soil infiltration rate during early plant establishment. Géotechnique 68, 646–652. https://doi.org/10.1680/jgeot.17.T.037 (2018).

Ni, J., Leung, A. K. & Ng, C. W. W. Unsaturated hydraulic properties of vegetated soil under single and mixed planting conditions. Géotechnique 69, 554–559. https://doi.org/10.1680/jgeot.17.T.044 (2019).

Rahardjo, H., Satyanaga, A., Leong, E. C., Santoso, V. A. & Ng, Y. S. Performance of an instrumented slope covered with shrubs and deep-rooted grass. Soils Found. 54, 417–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sandf.2014.04.010 (2014).

Ali, F. H. & Osman, N. Shear strength of a soil containing vegetation roots. Soils Foundat. 48, 587–596. https://doi.org/10.3208/sandf.48.587 (2008).

Zhang, C.-B., Chen, L.-H., Liu, Y.-P., Ji, X.-D. & Liu, X.-P. Triaxial compression test of soil–root composites to evaluate influence of roots on soil shear strength. Ecol. Eng. 36, 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2009.09.005 (2010).

Rahardjo, H., Satyanaga, A., Wang, C. L., Wong, J. L. H. & Lim, V. H. Effects of unsaturated properties on stability of slope covered with Caesalpinia crista in Singapore. Environ. Geotech. 7, 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1680/jenge.17.00031 (2020).

Satyanaga, A. & Rahardjo, H. Stability of unsaturated soil slopes covered with Melastoma malabathricum in Singapore. Proceed. Institut. Civil Eng. – Geotech. Eng. 172, 530–540. https://doi.org/10.1680/jgeen.18.00215 (2019).

Shi, X., Qin, T., Yan, D., Tian, F. & Wang, H. A meta-analysis on effects of root development on soil hydraulic properties. Geoderma 403, 115363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2021.115363 (2021).

Ni, J. J., Leung, A. K. & Ng, C. W. W. Modelling effects of root growth and decay on soil water retention and permeability. Can. Geotech. J. 56, 1049–1055. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2018-0402 (2019).

Nong, X. F., Rahardjo, H., Lee, D. T. T., Leong, E. C. & Fong, Y. K. Effects of organic content on soil-water characteristic curve and soil shrinkage. Environ. Geotech. 8, 442–451. https://doi.org/10.1680/jenge.19.00028 (2021).

Minasny, B. & McBratney, A. B. Limited effect of organic matter on soil available water capacity. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 69, 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.12475 (2018).

Rawls, W. J., Pachepsky, Y. A., Ritchie, J. C., Sobecki, T. M. & Bloodworth, H. Effect of soil organic carbon on soil water retention. Geoderma 116, 61–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7061(03)00094-6 (2003).

Gui, Y., Zhang, Q., Qin, X. & Wang, J. Influence of organic matter content on engineering properties of clays. Adv. Civil Eng. 2021, 6654121. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6654121 (2021).

ElMouchi, A., Siddiqua, S., Wijewickreme, D. & Polinder, H. A review to develop new correlations for geotechnical properties of organic soils. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 39, 3315–3336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-021-01723-0 (2021).

Stewart, B. A. & Hartge, K. Soil structure: Its development and function (CRC Press, 1995).

Li, Y. & Duan, W. Decoding vegetation’s role in landslide susceptibility mapping: An integrated review of techniques and future directions. Biogeotechnics 2, 100056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bgtech.2023.100056 (2024).

Fredlund, D. G. & Xing, A. Equations for the soil-water characteristic curve. Can. Geotech. J. 31, 521–532. https://doi.org/10.1139/t94-061 (1994).

Zhai, Q. & Rahardjo, H. Determination of soil–water characteristic curve variables. Comput. Geotech. 42, 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2011.11.010 (2012).

Guan, G. S., Rahardjo, H. & Choon, L. E. Shear strength equations for unsaturated soil under drying and wetting. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 136, 594–606. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0000261 (2010).

Vanapalli, S. K., Fredlund, D. G., Pufahl, D. E. & Clifton, A. W. Model for the prediction of shear strength with respect to soil suction. Can. Geotech. J. 33, 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1139/t96-060 (1996).

Xu, Y. F. Fractal approach to unsaturated shear strength. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 130, 264–273. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(2004)130:3(264) (2004).

Rahardjo, H., Leong, E. C., Deutcher, M. S., Gasmo, J. M., & Tang, S.K. Rainfall-induced slope failures. Geotechnical engineering monograph 3, NTU-PWD Geotechnical Research Centre, Nanyang Technological Univ., Singapore, 1–86 (2000).

Rangarajan, S., Rahardjo, H., Satyanaga, A. & Li, Y. Influence of 3D subsurface flow on slope stability for unsaturated soils. Eng. Geol. 339, 107665 (2024).

Rahardjo, H., Satyanaga, A. & Leong, E.-C. Effects of flux boundary conditions on pore-water pressure distribution in slope. Eng. Geol. 165, 133–142 (2013).

Rahardjo, H., Aung, K. K., Leong, E. C. & Rezaur, R. B. Characteristics of residual soils in Singapore as formed by weathering. Eng. Geol. 73, 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2004.01.002 (2004).

Masi, E. B., Bicocchi, G. & Catani, F. Soil organic matter relationships with the geotechnical-hydrological parameters, mineralogy and vegetation cover of hillslope deposits in Tuscany (Italy). Bull Eng. Geol. Environ. 79, 4005–4020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-020-01819-6 (2020).

Gao, Z. et al. Root-induced changes to soil water retention in permafrost regions of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau China. J. Soils Sed. 18, 791–803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-017-1815-0 (2018).

Leung, A. K., Garg, A. & Ng, C. W. W. Effects of plant roots on soil-water retention and induced suction in vegetated soil. Eng. Geol. 193, 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2015.04.017 (2015).

Ng, C. W. W., Leung, A. K. & Woon, K. X. Effects of soil density on grass-induced suction distributions in compacted soil subjected to rainfall. Can. Geotech. J. 51, 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2013-0221 (2014).

Amiri Khaboushan, E., Emami, H., Mosaddeghi, M. R. & Astaraei, A. R. Estimation of unsaturated shear strength parameters using easily-available soil properties. Soil Tillage Res. 184, 118–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2018.07.006 (2018).

Ly, H.-B., Nguyen, T.-A. & Pham, B. T. Estimation of soil cohesion using machine learning method: A random forest approach. Adv. Civil Eng. 2021, 8873993. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/8873993 (2021).

Ho, T. K. Random decision forests. in Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition vol. 1, 278–282, https://doi.org/10.1109/ICDAR.1995.598994 (1995).

Wackernagel, H. Ordinary kriging. In Multivariate Geostatistics: An introduction with applications (ed. Wackernagel, H.) 79–88 (Springer, Berlin and Heidelberg, 2003).

Rigon, R., Bertoldi, G. & Over, T. M. GEOtop: A distributed hydrological model with coupled water and energy budgets. J. Hydrometeorol. 7, 371–388. https://doi.org/10.1175/JHM497.1 (2006).

Endrizzi, S., Gruber, S., DallAmico, M. & Rigon, R. GEOtop 2.0: Simulating the combined energy and water balance at and below the land surface accounting for soil freezing snow cover and terrain effects. Geoscient. Model. Devel. 7, 2831–2857. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-7-2831-2014 (2014).

Reid, M. E., Christian, S. B., Brien, D. L. & Henderson, S. T. Scoops3D: Software to analyze 3D Slope Stability throughout a Digital Landscape. Techniques and Methods https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/tm14A1 (2015) https://doi.org/10.3133/tm14A1.

Public Utilities Board. Code of practice on surface water drainage. (Seventh Edition – Dec 2018 with amendments under Addendum No. 1 – Apr 2021) (2018). Singapore: Public Utilities Board (PUB).

Satyanaga, A. & Rahardjo, H. Role of unsaturated soil properties in the development of slope susceptibility map. Proceed. Institut. Civil Eng. – Geotech. Eng. 175, 276–288 (2022).

van Genuchten, MTh. A closed-form equation for predicting the hydraulic conductivity of unsaturated soils. Soil Sci. Soci. Am. J. 44, 892–898. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1980.03615995004400050002x (1980).

Lundberg, S. & Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions (2017).

Wang, X., Li, Z., Chen, Y. & Yao, Y. Influence of vetiver root morphology on soil-water characteristics of plant-covered slope soil in south central China. Sustainability 15, 1365. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15021365 (2023).

Jotisankasa, A. & Sirirattanachat, T. Effects of grass roots on soil-water retention curve and permeability function. Can. Geotech. J. 54, 1612–1622. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2016-0281 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support from the Singapore Ministry of National Development and the National Research Foundation under the Cities of Tomorrow R&D Programme (CoT Award No. CoT-V4-2020-2) and School of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Nanyang Technological University. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not reflect the views of the Singapore Ministry of National Development and National Research Foundation, Singapore.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.L., S.R., H.R., A.S., C.L.W., H.K., T.H.N., C.H.P., S.G.; Methodology: Y.L., S.R., H.R., A.S.; Software: Y.L.; Formal analysis: Y.L., S.R.; Data Curation: Y.L., H.R., Y.S.; Investigation: Y.L., Y.S., A.H.H.; Visualization: Y.L., S.R.; Writing—Original Draft: Y.L., S.R.; Writing – review & editing: Y.L., S.R., H.R., Y.S., A.H.H., A.S., E.C.L., C.H.P., S.G.; Funding acquisition: H.R., H.K., T.H.N.; Supervision: H.R., E.C.L., S.K.W, C.L.W.; Project administration: H.K., T.H.N.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Rangarajan, S., Rahardjo, H. et al. Database of soil properties incorporating organic content from roots and soil organisms for regional slope stabilisation. Sci Rep 15, 1066 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85250-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85250-5

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Enhanced characterization of hydraulic conductivity via standard penetration test for sandy soils and weathered rocks

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Random forest-based prediction of shallow slope stability considering spatiotemporal variations in unsaturated soil moisture

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Data-Driven Modeling of Additional Root-Soil Stress in Unsaturated Clayey Silt at Varying Strain Levels

Geotechnical and Geological Engineering (2025)