Abstract

To retrospectivly investigate the short-term clinical outcomes of one-stop and two-staged endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) procedures for treatment of varicose veins (VVs) and iliac vein compression syndrome (IVCS). In this study, 424 patients were treated for VVs and IVCS from June 2017 to June 2020, 91 underwent one-stop stent angioplasty (SA) and EVLA, 132 underwent two-staged SA and EVLA, 104 underwent one-stop balloon angioplasty (BA) and EVLA, and 97 underwent two-staged BA and EVLA. Clinical outcomes and complications were recorded at 3 and 12 months post-intervention. Quality of life (QoL) was assessed with the venous clinical severity score (VCSS) and Villalta scale. Patients in the SA groups were older (p < 0.05) with higher BMI values (p < 0.05). The incidences of iliac vein stenosis (p < 0.001) and recurrent VVs (p < 0.01) were lower in the one-stop SA group. The VCSS was significantly improved (p < 0.05) at 12 months after the one-stop SA procedure. The one-stop SA procedure effectively relieved symptoms, decreased symptom recurrence, and improved the QoL of patients with VVs and severe IVCS. The two-staged BA procedure is recommended for patients with longer life expectancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Varicose veins (VVs) of the lower extremities is commonly encountered by vascular surgeons. Most patients present with complaints of limb soreness, swelling, pigmentation, and ulceration as the main clinical manifestations, which severely diminish quality of life (QoL)1. As an alternative to high ligation and stripping of the great saphenous vein, endovenous laser ablation (EVLA) is recommended as the first-line treatment in patients with great saphenous vein (GSV)- small saphenous vein (SSV) insufficiency owning to good efficacy, minimal invasiveness, and an excellent safety profile2,3,4.

Iliac vein compression syndrome (IVCS), also known as May–Turner syndrome, is caused by compression of the iliac vein due to abnormal anatomy of the iliac artery or pelvic cavity. Once it affects the lower extremity and deep vein valves, symptoms similar to primary deep vein insufficiency will appear, including varicose veins of the lower limb, edema of the lower limb, and pigmentation. When the disease worsens, there may be symptoms of severe deep vein valve insufficiency, such as leg ulcers, or secondary thrombosis in the iliofemoral vein.In clinical, VVs are often accompanied by different degrees of IVCS and restoration of iliac vein blood flow by balloon angioplasty (BA) or stent angioplasty (SA) significantly improves QoL. Previous studies5,6 showed that the combination of high ligation /EVLT performed after stent placement during the same hospitalization period is an effective therapeutic strategy for patients with IVCS and VVs during short-term follow-up. However, the choice of either the one-stop or two-staged procedure for treatment of both IVCS and VVs is difficult because of the lack of relevant research.

Methods

Study approval

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (No. 2021 − 353) and the second hospital of Anhui Medical University (No. YX2023-86) and conducted in accordance with the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects described in the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients voluntarily consented to the interventions after thorough clarification of each treatment option. Prior to inclusion in this study, written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Patients

The cohort of this multicenter retrospective study included 424 patients (187 males and 235 females) diagnosed with VVs and IVCS by ultrasonography or digital subtraction angiography from June 2017 to June 2020 at one of 2 participating hospitals: 227 patients at Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (Nanjing, China), and 197 at the Second Hospital of Anhui Medical University (Hefei, China).

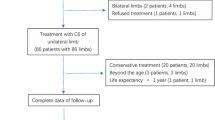

Individuals fulfilling the selection criteria were assigned to one of four treatment groups: (i) one-stop SA (oSA group; 91 patients; SA and EVLA; one hospitalization); (ii) two-staged SA (tSA group; 132 patients; SA and EVLA; two-staged hospitalization; (iii) one-stop BA (oBA group; 104 patients; BA and EVLA; one hospitalization; or (iv) two-staged BA (tBA group; 97 patients; BA and EVLA; two-staged hospitalization).

The clinical symptoms (i.e., degree of twisting, enlargement of superficial veins, pigmentation, dermatitis, and chronic ulcer) of all patients were graded in accordance with the CEAP (Clinical-Etiology-Anatomy-Pathophysiology) classification system. All analyses of the clinical data adhered to the Strengthening The Reporting Of Cohort Studies in Surgery (STROCSS) 2021 guidelines7.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were: (1) symptomatic VVs (pigmentation, dermatitis, and/or chronic ulcers); (2) CEAP classification ≥ C2; (3) non-thrombotic iliac vein stenosis ≥ 50%; (4) age, 18–85 years; (5) no history of anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy; (6) no surgical contraindication; (7) GSV and sapheno-femoral junction (SFJ) incompetence defined as reflux > 0.5 s seen on DUS imaging with an intrafascial length of at least 15 cm measured from the SFJ downwards; (8) GSV diameter between 0.3 and 1.5 cm6. The exclusion criteria were: (1) history of acute cardiovascular and/or cerebrovascular disease; (2) history of malignancy; (3) history of immune system disease; (4) pelvic congestion syndrome; (5) obstruction of the inferior vena cava; (6) patient refusal; and (7) incomplete baseline demographic/characteristic data.

Diagnosis and treatment

The diagnoses of all patients were confirmed by ascending phlebography of the lower limbs or ultrasonography. Indications for surgery included reduction of the iliac vein diameter of > 70% and involvement of > 2 pelvic collateral vessels. The diagnostic criteria for IVCS were: (1) detection of flow reversal in the ipsilateral internal iliac vein; (2) identification of multiple pelvic collaterals; and (3) enlargement of the ascending lumbar vein secondary to chronic venous hypertension, with pressure gradients across the compression exceeding 2 mmHg (2.66 cmH2O)8. The possibility of post-thrombotic syndrome-induced or thrombotic IVCS was excluded in all patients.

All endovenous procedures were conducted under local anesthesia with 10 mL of 1% lidocaine. Access to the ipsilateral femoral vein was achieved using the Seldinger technique. Prior to selective catheterization of the femoral vein, intravenous heparin (70 U/kg) was routinely administered. Stenosis of the iliac vein was re-assessed and measured by comparison to an adjacent non-stenotic vein segment using multi-angle venography. If the diameter reduction exceeded 50%, the stenotic lesion was managed with an appropriate balloon or stent. Subsequent to placement of the guidewire through the stenotic lesion, BA was performed utilizing a standard balloon dilation catheter (Mustang™, Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA; Atlas™, C.R. Bard Inc., Covington, GA, USA; or Armada™, Abbott Cardiovascular, Plymouth, MN, USA). The balloon diameter was 6–14 mm, the dilation time was 30–60 s, and the filling pressure was 3–6 atm. The therapeutic effect of balloon dilation was assessed by angiography and the proximal and distal iliac vein pressures were measured using a catheter.

Stenting of the iliac vein was conducted in roadmap mode utilizing a Nitinol stent (E-Luminex™, C.R. Bard Inc.; S.M.A.R.T. CONTROL™, Cordis, Santa Clara, CA, USA; or WALLSTENT™ Endoprosthesis, Boston Scientific). The proximal end of the stent was positioned within 3–5 mm of the iliac-vena cava junction. Inadequately expanded stents were post-dilated with a balloon post-deployment. Following the stenting procedure, a residual stenosis of < 20% was considered a procedural success. Additionally, the proximal and distal iliac vein pressures were measured (Fig. 1).

Patients who received the one-stop procedure underwent EVLA for VVs within 48 h after interventional surgery. Depending on the paitents’ general conditions or their own unwillingness, all others were readmitted for EVLA after 30 days as the second stage. For endovenous laser ablation (EVLA), Duplex ultrasound (DUS)-guided percutaneous access to the GSV around the knee was first obtained. After introducing the bare fiber, the tip was positioned approximately 2 cm below the SFJ. A 980-nm diode laser equipment (Eufoton) was used to ablate the GSV with 10 W in continuous mode, while the limb was compressed along the GSV for 5 min.

Outcome assessment

Patient outcomes were evaluated bimonthly following the procedures. The assessors responsible for determining efficacy outcomes and the evaluators of safety and efficacy outcomes were blinded to the treatment allocations. The Venous Clinical Severity Score (VCSS) and Villalta scale were utilized to assess changes in clinical symptoms before the procedure and at 1 and 12 months afterward. Safety outcomes included bleeding events, recurrent venous thromboembolism, and mortality, which were monitored throughout the follow-up period and summarized at 10 days and 24 months. Clinically overt bleeding was categorized as “major” if the event resulted in a decrease in hemoglobin levels ≥ 2.0 g/dl, transfusion ≥ 2 U of red blood cells, or involvement of critical sites, while less severe clinically overt bleeding was classified as “minor.”

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Continuous variables were analyzed with analysis of variance (ANOVA) and categoric variables using the χ2 test. A value of P < 0 0.05 was considered statistically significant. R-4.3.1 was used for data analysis and graphing.

Results

Baseline and demographic characteristics

There were no significant differences in baseline and demographic characteristics among the four groups. As compared to the BA groups, individuals in the SA groups were older before the procedures (mean age, 50.67 vs. 51.54 years, respectively) with greater body mass index values (p = 0.002). Additionally, the prevalence of hypertension was higher in the tSA group than the other three groups (p = 0.047) (Table 1).

Procedure-related parameters

The procedure-related parameters of all four groups are shown in Table 2. There were no significant differences in the degree of iliac vein stenosis among the four groups. BA of the compressed common iliac vein was initially performed (diameter, 6–14 mm; dilation time, 30–60 s; filling pressure, 3–6 atm; cycles, 2–3). The therapeutic effect of balloon dilation was assessed by angiography and the proximal and distal common iliac vein pressures were measured with a catheter. After balloon dilation, 223 patients in the oSA and tSA groups who achieved stenosis of > 50% or iliac vein pressure change > 2 mmH2O (mean pressures, 2.23 and 2.22 mmH2O, respectively) underwent SA. Of these patients, 84.8% and 15.2% were implanted with one and two stents, respectively (41.7%, 34.5%, and 23.8% with the S.M.A.R.T. CONTROL™, E-Luminex™, and WALLSTENT™ Endoprosthesis stents, respectively). The mean stent diameter was 14.12 (range, 12–16) mm.

Follow-up

Baseline and demographic data were collected. All patients were monitored by a qualified chief physician from the research team. The VCSS was employed to assess changes in clinical symptoms and QoL before the procedure and at 3 and 12 months afterward. All 424 patients completed the follow-up examinations in the Outpatient Department with none lost to follow-up at 3 months. However, 52 patients were lost to follow-up at 12 months (13, 14, 15, and 10 patients in the oSA, tSA, oBA, and tBA groups, respectively) (Fig. 2).

During the follow-up period, 5 and 14 patients were diagnosed with deep vein thrombosis (DVT) at 3 and 12 months, respectively. Following BA alone, re-stenosis of the iliac vein was diagnosed in almost 90% of patients. The recurrence rate of VVs was significantly higher in the oBA and tBA groups than the oSA and tSA groups (14/104 and 11/97 vs. 3/91 and 5/132, respectively, p = 0.008). Moreover, the incidence of re-intervention was significantly higher in the oBA and tBA groups than the oSA and tSA groups (22/104 and 16/97 vs. 5/91 and 11/132, respectively, p = 0.008) (Table 3).

QoL assessment

QoL was assessed using the Villalta scale and VCSS at baseline and at 3 and 12 months after the procedure (Table 4). As compared to baseline, the Villalta scale and VCSS values were significantly decreased at 3 and 12 months. At 3 months after the procedure, there were significant differences in the Villalta scale, but not the VCSS, values among the four procedures. At 12 months, the Villalta scales and VCSS values were significantly decreased (p < 0.05) in the oSA group, indicating that patients in this group experienced the most benefits (Fig. 3).

Discussion

In 1957, May et al.9 proposed that pelvic vein thrombosis mainly occurs on the left side because a lumen lesion of the left common iliac vein is closely related to anterior and posterior compression of the right common iliac artery and the lumbosacral vertebra. Later, Cockett et al.10 introduced the term iliac vein compression syndrome. Venous hypertension of the lower extremities, usually induced by VVs and/or IVCS, results in ulceration, deep vein thrombosis, and/or other serious pathological manifestations. Thus, improved procedures are urgently needed for treatment of VVs and IVCS.

EVLA is safe and effective for treatment of VVs11. However, EVLA alone is associated with a high recurrence rate of VVs with IVCS12. The results of the present study demonstrated that EVLA after SA or BA significantly improved the QoL of patients with VVs and IVCS. The VCSS values of the oSA and tSA groups were positively associated with those of the oBA and tBA groups, consistent with the findings of previous studies12,13. Following administration of the systemic oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban, venous stents can effectively and reliably relieve compression. Notably, there was no significant difference in stent patency between the oSA and tSA groups. Hypertension of lower extremities was eliminated over a relatively short period, which showed a tendency toward less DVT in the oSA group (p = 0.534). Post-intervention QoL was superior for patients in the oSA group as compared to the tSA group. Therefore, the one-stop procedure should be considered for treatment of VVs and IVCS.

Even though BA temporarily restored venous return and shortened the surgical duration, as compared to SA, complications of elastic recoil and intima injury remain problematic. Even if venous hypertension of the lower extremities is temporarily relieved, recurrent VVs is unavoidable. The restenosis rate was higher in the BA groups than the SA groups. Therefore, stent implantation is strongly recommended for treatment of symptomatic VVs and IVCS. Long-term follow-ups of up to 5 years have shown promising patency rates of venous stenting of 79.7–94% for IVCS14,15. In this study, three different types of bare-metal stents were applied and stent grafting was recommended only for co-existence of an arteriovenous fistula. Accordingly, to avoid complications associated with metal implants, BA is recommended for patients with longer life expectancy. The cohort of the present study included 16 relatively young patients (mean age, 36.88 years; CEAP classification, C2) who underwent BA for cosmetic reasons.

Notably, post-intervention QoL was superior in the tBA group than the oBA group. More than 30% of the IVCS patients in the tBA group were diagnosed recurrent IVCS during the second hospitalization and, therefore, were excluded from the tBA group. Thus, BA might not be particularly appropriate for all IVCS patients.

EVLA with the one-stop procedure was the most effective regimen. The use of stents was found to effectively alleviate iliac vein stenosis and hemodynamic instability, while reducing symptom recurrence. These findings suggest that a combined approach of iliac stent placement and EVLA is appropriate for patients with severe IVCS and VVs. However, further comprehensive evidence is needed to strengthen the validity of the one-stop vein stenting and EVLA procedure for patients presenting with symptomatic VVs and IVCS.

There were several limitations to this study that should be addressed. First, this was a multi-center retrospective non-randomized controlled trial. Thus, additional data are needed to further confirm the conclusions. Second, since the follow-up duration was relatively short, the long-term outcomes should be investigated to clarify the efficacy of the different procedures. Third, the effectiveness of radiofrequency ablation vs. EVLA for treatment of VVs was not assessed. Lastly, the long-term efficacy of EVLA with SA or BA on iliac vein function was not assessed, indicating the necessity for more comprehensive explorations from multiple perspectives to strengthen these conclusions.

Conclusions

EVLA with SA or BA relieved venous hypertension of the lower extremities. When performed concurrently, stent implantation and EVLA is an effective strategy for treatment of symptomatic VVs and IVCS. For patients with longer life expectancy, BA and EVLA should be performed sequentially.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Hamdan, A. Management of varicose veins and venous insufficiency[J]. Jama 308 (24), 2612–2621 (2012).

Liu, Z. X. et al. Efficacy of Endovenous Laser Treatment Combined with Sclerosing Foam in Treating Varicose veins of the Lower Extremities[J]. Adv. Ther. 36 (9), 2463–2474 (2019).

Masuda, E. et al. The 2020 appropriate use criteria for chronic lower extremity venous disease of the American venous forum, the Society for Vascular Surgery, the American Vein and Lymphatic Society, and the Society of Interventional Radiology[J]. J. Vasc Surg. Venous Lymphat Disord. 8 (4), 505–525e4 (2020).

Radaideh, Q., Patel, N. M. & Shammas, N. W. Iliac vein compression: epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment[J]. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 15, 115–122 (2019).

Yang, L., Liu, J. & Cai, H. at al. The clinical outcome of a one-stop procedure for patients with iliac vein compression combined with varicose veins. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. ;6(6):696–701. (2018).

Guo, Z. et al. Effectiveness of iliac vein stenting combined with high ligation/endovenous laser treatment of the great saphenous veins in patients with clinical, etiology, anatomy, pathophysiology class 4 to 6 chronic venous disease. J. Vasc Surg. Venous Lymphat Disord. 8 (1), 74–83 (2020).

Mathew, G. & Agha, R. S. T. R. O. C. S. S. : Strengthening the reporting of cohort, cross-sectional and case-control studies in surgery[J]. Int J Surg, 2021, 96:106165. (2021).

Butros, S. R. et al. Venous compression syndromes: clinical features, imaging findings and management[J]. Br. J. Radiol. 86 (1030), 20130284 (2013).

May, R. & Thurner, J. The cause of the predominantly sinistral occurrence of thrombosis of the pelvic veins[J]. Angiology 8 (5), 419–427 (1957).

Cockett, F. B. & Thomas, M. L. The iliac compression syndrome[J]. Br. J. Surg. 52 (10), 816–821 (1965).

Huang, Y. et al. Endovenous laser treatment combined with a surgical strategy for treatment of venous insufficiency in lower extremity: a report of 208 cases[J]. J. Vasc Surg. 42 (3), 494–501 (2005). discussion 501.

Han, Y. et al. Clinical outcomes of different endovenous procedures among patients with varicose veins and iliac vein compression: a retrospective cohort study[J]. Int. J. Surg. 101, 106641 (2022).

Williams, Z. F. & Dillavou, E. D. A systematic review of venous stents for iliac and venacaval occlusive disease[J]. J. Vasc Surg. Venous Lymphat Disord. 8 (1), 145–153 (2020).

Knipp, B. S. et al. Factors associated with outcome after interventional treatment of symptomatic iliac vein compression syndrome[J]. J. Vasc Surg. 46 (4), 743–749 (2007).

Bashar, K. et al. Endovascular versus medical treatment of venous compression syndrome of the iliac vein - a systematic review[J]. Vasa 50 (1), 22–29 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Project funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82100517), Nanjing special fund for health science and technology development (YKK21073), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2020M670035ZX), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (SBK2020040321, SBK2020042213), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (0214-14380481), the Postdoctoral Research Funding Program of Jiangsu Province(2020Z368), the fundings for Clinical Trials from the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University, and the 2020 Jiangsu Province Shuangchuang Ph.D. Introducing Talent Project of Nan Hu and Xiaolong Du.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data collection: CH and KLS ; Analysis and interpretation: WC, YSL and WLL ; Writing the article: CH; Conception and design: LXQ, ZX, DXL and HN ; Overall responsibility: DXL and HN ; All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, H., Wang, C., Ye, S. et al. One-stop endovenous laser ablation leads to superior outcomes for varicose veins and iliac vein compression. Sci Rep 15, 1313 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85306-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85306-6