Abstract

With the increasing demand on high-density integration and better performance of micro-nano optoelectronic devices, the operation temperatures are expected to significantly increase under some extreme conditions, posing a risk of degradation to metal-based micro-/nano-structured metasurfaces due to their low tolerance to high temperature. Therefore, it is urgent to find new materials with high-conductivity and excellent high-temperature resistance to replace traditional micro-nano metal structures. Herein, we have proposed and fabricated a thermally stable graphene assembly film (GAF), which is calcined at ultra-high temperature (~ 3000 ℃) during the reduction of graphite oxide (GO). Compared with micro-nano metals that usually degrade at around 550 ℃, the proposed GAF maintains a high extent of stability at an extremely high temperature up to 900 ℃. In addition, to make GAF a prime candidate to replace micro-nano metals, we have modified its fabrication process for improving its conductivity to 1.3 × 106 S/m, which is quite close to metals. Thus, micro-nano optoelectronic devices could retain high efficiency even when GAF replaces the crucial micro-nano metals. To verify the thermostability of optoelectronic devices composed of GAF, we have compared the high-temperature resistance performance of two structures capable of achieving plasmon-induced transparency (PIT) at the THz region, one using micro-nano metals (Aluminum) and the other GAF. The Al metasurface displayed a near-complete loss of PIT effects after a high-temperature treatment, while GAF could remain excellent PIT properties at above 900 ℃, thus enable to fulfil its optimum performance. Overall, the proposed thermostable metasurface provides new pathway for the construction of thermostable optoelectronic devices that can operate under ultra-high temperature scenario.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the advancement of electronics and communication technologies, portable devices including smart phone, laptop etc. are getting smaller and more integrated. In this way, it is inevitable that the improvement of the computing power derived from the increase of the integration degree is at the expense of huge thermal density, potentially compromising performance and reliability1,2. In addition, as we know, the melting points of micro-nano metals are much lower than their corresponding bulk materials, which will seriously hinder their function under extremely high temperature conditions.

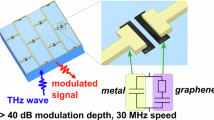

Carbon allotropes and their derivatives composed of mainly sp2 C-C backbone, have been considered as one of the best candidates for heat spreading materials3,4,5,6,7. Currently, the pyrolytic graphite films derived from polyimide film through carbonization and graphitization have become the primary materials for solving the overheating problem of electronics, though their thermal conductivity decrease from 1610 to 622 W m− 1 K− 1 as the increase of the polyimide film thickness. Hence, it is desirable to develop a new material which possesses characteristics, such as ultra-high conductivity, high-temperature resistance, lower thickness, and others. Graphene, a flat monolayer of hexagonal array of carbon atoms, is undoubtedly one of the most fascinating and extensively studied heat conducting materials due to its extraordinary in-plane thermal conductivity8,9,10. As a graphene-based macroscopic material, graphene assembly film (GAF) has also been significantly studied due to its excellent thermal conductivity when the thickness of GAF is in the range of 3–14.5 μm, demonstrating the superior performance in thermal management11,12. GAF not only exhibits excellent thermal management performance but also garners considerable attention for its applications in the terahertz (THz) frequency range13,14,15,16. These advantages of graphene make it an excellent material for developing applications involving THz metasurfaces. Therefore, we believe that the insightful combination of thermal management and THz operation frequencies would provide a novel perspective and potential for exploring the thermal applications of metasurfaces in the THz regime.

THz metasurfaces consisted of arrays of sub-wavelength artificial meta-atoms enable to efficiently manipulate THz wave, which have exhibited great application potentials in the field of material detection17,18,19, defense and security20,21, and bio-sensing22,23,24,25. Comparing with the conventional THz devices which are suffered from the difficulties such as heaviness, inefficiency and difficulty in integration, THz metasurfaces are able to take the advantage of the strong localization capability derived from the sub-wavelength artificial meta-atom to overcome the above limitations. The plasmon-induced transparency (PIT) exhibited in metasurfaces has garnered significant interest. Most of the PIT effects arise from the interaction between two modes with similar frequencies but different Q-factors: a bright mode with a broad linewidth and a dark mode activated through near-field coupling, not directly by external fields26,27,28,29,30,31. Additionally, in some cases, both modes are excitable with one being a low Q-factor bright mode and the other a high Q-factor mode referred to as the quasi-dark mode, and sometimes it may be directly termed as a bright mode32,33,34. However, due to traditional microfabrication techniques such as photolithography and reactive ion etching, PIT metasurfaces are not only costly and time-consuming but also impractical for large-scale fabrication. Moreover, the most important thing is that the majority of the materials used for construction of the unit cells of traditional metasurface is aluminum (Al) whose melting point is relatively low, which will seriously hinder its application. Improving the temperature limit of thermal stability could protect the metal-based devices from degradation in rapid heating up process during the service, which has become one of the trickiest problems in this area.

Herein, to further improve the heat resistance threshold of metasurfaces, we have introduced the GAF with ultra-high conductivity to replace the Al material and proposed a thermo-stable PIT THz metasurface fabricated by a laser ablation processing system, which is composed by a 515 nm picosecond laser, a scan lens, and a matching scanning platform. The characteristics of GAF with unique preparation process determine their excellent thermal stability, which could contribute metasurfaces to serve stably in high-temperature environment. To demonstrate the thermo-stable ability of the proposed GAF at high temperature, we have compared the heat resistance threshold of two PIT structures based on GAF and Al. The PIT metasurface whose unit cells are composed by Al becomes more and more unstable due to the deformation of the Al microstructures with the increasing temperature, while GAF is able to maintain the excellent characteristics. The PIT metasurface composed by Al microstructure arrays completely loses the performance until the ambient temperature reaches 900 ℃, while the GAF not only maintains the excellent performance but also maintains intact. To further substantiate the operational mechanism of the proposed PIT metasurfaces, investigations have been conducted on the theoretical analysis using the coupled harmonic oscillator model, as well as on the distributions of the electric fields. Furthermore, the significant group delay performance associated with the PIT effect has been calculated, demonstrating potential applications in slow light technology and THz communications. These results prove that our proposed framework paves a new way for designing thermostable devices, and can further be extended to multifunctional integrated designs.

Design and fabrication

The melting of metals at high temperatures is a common phenomenon in many industrial processes. Fig. 1 shows the schematic of micro-nano Al metasurface and graphene assemble films after thermal treatment at different temperatures, which both were placed in a muffle furnace in the range of 300–900 °C to observe their behavior under extreme thermal stress. The size of the unit cell fabricated by photolithography is consistent with our optimized geometric size: w = 10 μm, a = 80 μm, b = 85 μm, h = 0.3 μm, t = 1000 μm and the distance between the two nanoslots is g = 5 μm. Besides, the conductivity of Al is set to 3.56 × 107 S m− 1 and the period of the unit cell P is set to 105 μm. The geometrical parameters of GAF are w = 40 μm, a = 220 μm, b = 240 μm, and g = 50 μm. When the sample was subjected to heating in a muffle furnace, reaching approximately 600 °C, conspicuous alterations in the surfaces of samples were observed, which shows the thermal stability of Al is compromised under high temperature. It should be noted that melting point is crucial for understanding the limitations of micro-nano Al metasurfaces in high-temperature applications. Some previous research results have indicated that for particles with diameters ranging from 44 to 121 nm, the onset temperature for Al melting is lowered to 590 °C35. Moreover, Firmansyah et al. proposed that certain Al nuclei may undergo partial melting between 300 and 600 °C, persisting in their molten state until reaching 690 °C36. The GAF composed of a few layers of stacked graphene exhibits relatively high thermal stability, making it exceptionally resistant to degradation at elevated temperatures. When the temperature was elevated to 600 °C, the GAF remained unaffected whereas the metallic components of the Al metasurfaces began to deteriorate, which has highlighted the superior thermal stability of GAF compared to traditional configuration. As melting and eventually forming a thin layer of alumina (Al2O3), the Al metasurface underwent a dramatic transformation, which has limited their applicability in extremely heated environments. Contrastingly, the GAF maintained their structural integrity and stability even at 900 °C proving its potential for use in high-temperature environments. The enduring stability of graphene at such elevated temperatures opens avenues for its application in relevant fields that demand high thermal stability, such as aerospace, automobile, and electronics.

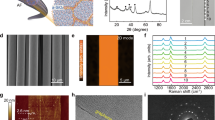

The preparation process of graphene assembly film (GAF) is described in Fig. 2a. Deionized water was used to dilute the GO slurry, which was thoroughly stirred to obtain the GO suspension with a concentration of 13 mg mL− 1. After evaporating at room temperature, the GO nanosheets in suspension were self-assembled to form GO film. The GO film was annealed in a high-temperature furnace under an argon atmosphere to create pre-GAF. The specific procedure involved sintering at 1300 °C for 3 h and annealing at 3000 °C for 1 h, where the heating rate from 1300 to 3000 °C was 5 °C min− 1. Next, the pre-GAF was calendered between two PET substrates at 100 MPa for 0.5 h, forming a dense layer-stacked GAF with a thickness of 14.5 μm, which is validated via the cross-sectional scanning electron microscope (SEM) images (Fig. 2d,e). GAF is large-scale structures formed by stacking graphene nanosheets in layers, which exhibits excellent electrical conductivity and low surface resistance. On a macroscopic scale, it exhibits metal-like behavior and excellent conductivity, with a measured electrical conductivity of 1.3 × 10⁶ S/m via the four-probe test, comparable to that of metals37,38. Additionally, GAF metasurfaces can serve as a transformative platform for flexible THz spoof plasmonics, as demonstrated in our previous studies39.

In addition, an ultrahigh thermal conductivity of the GAF was 1420.2 ± 12.8 W m− 1 K− 1. The excellent performance is attributed to the highly graphitized structure and the low defect concentration of GAF2, as confirmed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns and Raman spectrum (Fig. 2b,c). XRD patterns were acquired using X-ray D/MAX-RB instruments with Cu Kα radiation. Specifically, the (002) crystal plane shows a sharp diffraction peak at 26.5°, corresponding to an interlayer distance of 0.336 nm, demonstrating the highly graphitized structure of GAF40. Moreover, Raman spectra were recorded using a Renishaw Raman Spectrometer. The G band at 1580 cm− 1 and the weak D band at 1340 cm− 1 confirmed the low defect concentration and high degree of graphitization in the GAF41.

The GAF was fabricated using a one-step laser ablation process, allowing rapid and environmentally friendly patterning on various substrates. The system etches designs onto a photosensitive layer by following specific toolpath trajectories, thus bypassing traditional exposure and masking methods. The experimental setup includes a 515 nm picosecond laser, beam expander, scan mirrors, a telecentric scan lens and computer system for pattern fabrication, as shown in Fig. 3. The pico-second laser beam passes through an expender, two scan mirrors and the focusing lens is defocused on the GAF surface to induce graphene, which is adept at handling a diverse range of both rigid and flexible substates, along with a user-friendly and reliable operation. The proposed metasurface was prepared for experimental application upon completion of the laser ablation process.

Micro-nano Aluminum metasurface was produced by laser direct writing (LDW) with the DWL66 + system. A 1.5 μm thick layer of photoresist (AZ 1500) was spin-coated on a cleaned silicon wafer with 3000 rad/s and then baked for exposure. After exposure, a mixed solution of MIF 300 was employed for development, and deionized water was used as a fixing solution. Through the process of electron beam evaporation, a 200 nm thick layer of Al metal was deposited onto the patterned photoresist. Subsequently, the sample was immersed in acetone to dissolve and remove the excess metal, resulting in the creation of patterned nanostructures.

The morphology and microstructure of graphene cross-sections and nano-Al metasurfaces, both before and after heating, were examined by Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM, JEOL JSM-7100 F). The microstructures of the micro-nano Al metasurfaces and graphene metasurfaces, pre- and post-heating, were characterized by optical microscope (RX50M). X-ray diffraction (XRD) was employed to collect data in the 2θ range of 20 to 60°.

Result and discussion

Characterization of heat treatment

It has been reported that Al particles and thin films ignite at relatively low temperatures, typically between 560 and 800 °C42. Intriguingly, Al particles with diameters less than 1 μm demonstrate ignition at temperatures around 600 °C, a notable observation considering the size-dependent thermal properties of nanomaterials43,44. In this work, two samples were heat-treated by using a muffle furnace, which has a temperature range of 0–1000 °C and a precision of 1 °C. The temperature rises rapidly, typically taking 15–30 min to increase from room temperature to 1000 °C. Samples were heat-treated at temperatures of 300, 500, 700, and 900 °C using a heating rate of 10 °C min− 1, and then holding for 1 h. Fig. 4 shows the optical microscopy and typical scanning electronic microscopic (SEM) view of different samples before and after baking process. At room temperature (Fig. 4a), the micro-nano Al metasurface displayed a meticulously ordered array of nanostructures. The silicon substrate appeared quite stable, maintaining its structural integrity without any noticeable deformation. At around 900 ℃ (Fig. 4b), the Al structures underwent significant morphological changes and form drops on the surface. In contrast, the GAF exhibiting a different thermal response which characterized by their hexagonal lattice structure, were evenly distributed and exhibit high surface uniformity at room temperature initially, as shown in Fig. 4c. As the temperature rises, the graphene maintained its structural integrity far longer than the Al nanostructures. It can be seen from the comparison of Fig. 4d that the GAF displayed no deformations, indicating the GAF remarkable thermal stability and strength. However, this phenomenon was not readily discernible through metallographic microscope. To gain deeper insights of samples, SEM was employed to capture detailed images of the Al surface (Fig. 4e–h). The SEM images revealed a significant loss of clarity in the structural patterns of the Al structure, indicative of oxidation processes occurring on the surface. The oxidation, particularly noticeable at elevated temperatures, led to the formation of an Al2O3 shell. The increased thickness of Al2O3 shells suggests a substantial alteration in the nanostructure, where the metallic core of the Al particles undergoes gradual sacrifice in favor of the growing oxide layer. The observation aligned with the thermodynamic principles governing the behavior of Al at high temperatures. Al, known for its affinity for oxygen, forms a thin oxide layer even at room temperature. However, the kinetics of the oxidation process are accelerated at elevated temperatures like 900 °C. This accelerated oxidation results in the thickening of the Al2O3 shell, effectively consuming or even depleting the metallic Al at the core.

(a,b) Optical microscopy images of micro-nano Al at room temperature (a) and for 900 °C heat treatment (b). Scale bars:100 μm. (c,d) Optical microscopy images of GAF at room temperature (c) and for 900 °C heat treatment (d). Scale bars: 200 μm. (e–h) Low magnification top view SEM image (e) and high-resolution SEM image (f–h) of micro-nano Al for 900 °C heat treatment. Scale bars: 100 μm, 10 μm and 1 μm.

THz-TDS experimental analysis

To better visualize the plasmon-induced transparency response before and after high-temperature heating of these two meta-structures, we investigate the temperature dependence of the spectral characteristics in different metasurfaces by THz time domain spectrometer (THz-TDS). The working principle of a THz time-domain spectrometer in this experiment is shown in Fig. 5a, which consists of an ultrafast laser, four off-axis parabolic mirrors, a detection device and a time delay line45. The optical pulses produced by laser are split into two paths with the first path traveling directly to the detector, while the other exciting a THz emitter with THz pulses emitted through a GaAs photoconductive antenna. Four off-axis parabolic mirrors are used to collimate and focus terahertz waves. Since THz pulse has a longer duration than the optical pulse, the arrival time of the THz pulse can be changed relative to the optical pulse by employing a delay line. The THz waves generated by the sample then focused onto a (110) ZnTe crystal, which is used as the THz detector. The refractive index of the ZnTe crystal changes due to the THz electric field. As the probe light passes through the ZnTe crystal, its polarization state changes, and this change is proportional to the THz field. After the polarization rotation, the probe light is detected by an instrument consisting of a quarter-wave plate, a Wollaston prism, and a balanced detector to measure the polarization change of the probe light. Finally, the signal from the balanced detector is amplified by a lock-in amplifier and read out. Prior to conducting tests on the samples, the transmission spectrum of a high-resistance silicon wafer is measured, thereby serving as an effective reference signal for comparative analyses. Moreover, the transmission spectrum of the metasurface is obtained by \(\left| {\tilde {t}\left( \omega \right)} \right|={{{E_s}\left( \omega \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{E_s}\left( \omega \right)} {{E_r}\left( \omega \right)}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{E_r}\left( \omega \right)}}\), where \({E_r}\left( \omega \right)\) and \({E_s}\left( \omega \right)\) are the electric amplitudes transmitted through the metasurface and silicon substrate, respectively. In the case of GAF, the substrate is effectively equivalent to air.

The micro-nano Al metasurface demonstrated a pronounced PIT window in the THz range at room temperature, as shown in Fig. 5b. It is noteworthy that the numerical outcomes exhibit substantial alignment with the related experimental data. The minor variances observed between the actual measurements and the simulations could stem from fabrication-related discrepancies. As the temperature escalated to 300 and 500 °C, the intensity of resonance peaks increased near 0.58 THz slightly. Particularly, the PIT window was attenuated gradually at 700 °C, accompanied by a pronounced red shift in resonance, indicating a loss in the electromagnetic response capabilities of material. The corresponding transmitted time-domain signals (Fig. 6) still exhibited resonance phenomena at 300 and 500 °C, with a frequency shift occurring at 700 °C. Fig. 5d–g shows the terahertz time-domain pulse signals for the Al metasurface and GAF at room temperature and 900 °C. Compared to the reference substrate, the terahertz pulse intensity of the metasurface is reduced, but it exhibits a strong resonance phenomenon, which is related to the terahertz response characteristics of the structural array. The resonance amplitude is more pronounced in Fig. 5e,g, where the oscillation magnitude of the pulse signals from the GAF is significantly increased. On the one hand, the micro-nano Al metasurface eventually lost its initial THz response characteristics almost entirely, with the deterioration becoming pronounced at 900 °C, shown in Fig. 5f. These observed thermal behaviors can be attributed to the primary mechanisms: (i) the reduction in the number of internal grain boundaries within the metallic structure, and (ii) the oxidation of the metal46. The former mechanism predominantly occurs at lower temperatures. This reduction in grain boundaries causes a blueshift in the resonance and increases the resonance oscillation strength. Such behavior is consistent with the earlier findings in gold47 and silver48 nanoparticles. It is noteworthy that the latter mechanism becomes dominant at higher temperatures. Here, the increase in the thickness of the Al2O3 shell, which envelops the metallic core, becomes a significant factor, as it provides a protective barrier but also leads to the sacrificial consumption of the metallic core. The consequent contraction of the metallic core results in a reduction in the scattering cross-section, thus lowering the peak intensity.

The time-domain signals results, heated at various temperatures 300, 500, and 700 °C were also analyzed, as depicted in the Fig. 6. Fig. 6a demonstrates a little decrease in the intensity of the THz pulses transmitted through the micro-nano Al metasurface compared to those transmitted through a silicon substrate. The sample may attenuate the pulse strength but enhance specific resonant characteristics of THz waves. It was observed that the time-domain signals for samples heated at 300 and 500 °C remained largely similar. However, a notable frequency shift occurred in samples heated to 700 °C, which is attributed to the oxidation of aluminum in the samples at higher temperatures. Therefore, the oxidation altered the properties of material and affected its interaction with THz pulses consequently. The time-domain signals of graphene from 300 to 700 °C depicted in Fig. 6b–d show remarkable consistency, indicating that graphene retains its intrinsic properties even at high temperatures. We believe that the performance of GAF could find many exciting high-temperature THz applications. In Fig. 6b–d, the larger amplitudes of the terahertz tail waves are observed, which could result from material dispersion broadening the terahertz pulse, free carrier absorption or relaxation dynamics in the medium, or reflections at optical interfaces. Variations in experimental parameters, such as laser power or crystal alignment, might also contribute.

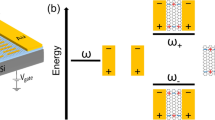

Mechanism of PIT

After analyzing the thermal properties of the prepared samples, it is necessary to briefly analysis the fundamental principles of the PIT effect (Fig. 7). It is noteworthy that the prepared GAF is a complementary asymmetric structure which can be explained by Babinet’s principle that the field distribution generated by a structure corresponds to that of its complementary structure under the same incident wave49. As can be seen in Fig. 7a, For the micro-nano Al metasurface, the SRR slot array resonates strongly at 0.42 THz when excited along the x-axis, while the closed wire resonator (CWR) slot array exhibits a transmission resonance at 0.66 THz. Upon combining the SRR and CWR into a single unit, a distinct transparency peak of 61% is noted at 0.54 THz between their resonant frequencies of 0.42 and 0.66 THz. On the other hand, Fig. 7b presents the results for the GAF. Similarly, with the GAF configuration, the corresponding PIT peak emerges at 0.509 THz. Specifically, when the SRR and CWR are both integrated simultaneously into a unit cell, a clear PIT effect with a transparency window at 0.509 THz is visible. The CWR does not support the odd eigenmodes due to its symmetry. Its lowest order eigenmode is even and can be regarded as an electric dipole resonance similar to that of the cut wires50. Thus, this resonance couples strongly to the radiation field that can be considered the bright mode. The SRR mode exhibits a higher quality factor which has weaker coupling with the incident light field, thus it is regarded as the quasi-dark mode.

To better explain the underlying mechanism of the PIT effect, we employ a simple two-particle PIT model51. This model considers a bright mode and a quasi-dark mode, referred to as “particle A” and “particle B” both of which couple to the incident THz electric field. The system is characterized by the following set of coupled differential Eqs. 51,52:

In the above equations, the variables \(({x_a},{x_b})\), \(({q_a},{q_b})\), \(({m_a},{m_b})\), \(({\omega _a},{\omega _b})\)\(({\gamma _a},{\gamma _b})\) and \(\kappa\) denote the displacements, effective charge, effective masses of two particles (the SRR and CWR elements), resonance angular frequencies, loss factor of particle A (B) and the coupling coefficient between the two particles, respectively. The relationships of \(({q_a},{q_b})\) and \(({m_a},{m_b})\) are defined as \({q_b}={{{q_a}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{q_a}} A}} \right. \kern-0pt} A}\) and \({m_b}={{{m_a}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{m_a}} B}} \right. \kern-0pt} B}\), which A and B are dimensionless constants indicating the free-space coupling strengths of the bright and quasi-dark modes to the incident THz wave.

Thus, the linear susceptibility χ by solving Eqs. (1) and (2) for \({x_a}\) and \({x_b}\), which links the effective polarization \({\varvec{P}}={q_a}{x_a}+{q_b}{x_b}\) to the intensity of the incident electric field E, can be written as:

Here, \(Re\left[ \varvec{\chi} \right]\) and \(Im\left[ \varvec{\chi} \right]\) represent the dispersion and the absorption (loss) within the medium. In the case of the Al metasurface, the transmission coefficient is defined as T = 1-\(Im\left[ \varvec{\chi} \right]\), based on the Kramer-Kronig relations34. As for GAF, the reflection is calculated using the transmission equation in a standard fabricated structure according to the Babinet principle. We plot the theoretically fitted transmission and reflection spectra Fig. 7a,b, which show good agreement with the corresponding numerically simulated curves. The corresponding characteristic parameters in Table 1 are calculated by fitting the transmission spectra of multispectral PIT meta-molecule systems with the dimensionless constants of Al metasurface (and GAF) A = 4.591 (6.5), B = 0.713 (3.2). For a normally incident wave with E-field along the x-axis and y-axis, we also plot the E-field distributions at narrow transparency window to further illuminate the mechanism of PIT effect, as illustrated in Fig. 7e,f. One can observe that the E-field is almost suppressed at 0.54 and 0.509 THz, which indicates that the metasurface couples with the incident THz radiation weakly because of the out-of-phase field oscillation. Therefore, the transparency window of the PIT is a direct consequence of the weak hybridization of the CWR and the SRR. Similar electric field and current distributions echo the findings in other PIT phenomena involving bright and quasi-dark mode coupling, as referenced in literature34.

Group delay, which measures the time delay of a light pulse during propagation, is essential for assessing slow wave performance in PIT systems. It is defined as \(\Delta {t_g}= - d\phi /d\omega\), where \(\omega =2\pi f\) is angular frequency, and \(\phi\) is the transmission(reflection) phase shift53. The group delays of Al metasurface and GAF for x-polarization and y-polarization are shown in Fig. 7c,d. The maximum group delay for the former is observed to be 13.9 ps at around 0.54 THz (Fig .7c). Similarly, the sharp dispersion region leads to the maximum group delay of 9.93 ps (Fig. 7d). Such large positive group delays strongly support the slow light capability of the PIT metasurface, indicating that the design holds strategic importance for practical slow light device applications.

Conclusion

In this work, we have demonstrated performance of micro-nano Al metasurfaces and GAF after extreme temperature treatments, along with analysis of the PIT effects in the THz domain. These two types of metasurfaces exhibit markedly different behaviors when subjected to temperature effects. Remarkably, the GAF maintains its structural and spectral characteristics even when heated to 900 °C, indicating exceptional thermal stability. It shows a great potential for developing optical and electronic devices capable of operating in extreme environmental conditions. The micro-nano metal metasurfaces display a near-complete loss of PIT effects and spectral properties after the same high-temperature treatment. Not only are the temporal and spectral characteristics of these metasurfaces revealed in the THz domain, but their internal resonant mechanisms and slow light effects are also examined. Benefiting from the thermal stability of GAF, the proposed structure may be a superior candidate for THz applications, especially in the environments involving high temperatures. The thermal durability of graphene in maintaining its THz response capabilities opens avenues for its application in high-temperature sensors, THz communication systems, and thermal-intensive technologies.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Shen, B. W., Zhai, W. T. & Zheng, W. G. Ultrathin flexible graphene film: an excellent thermal conducting material with efficient EMI shielding. Adv. Funct. Mater. 24, 4542–4548 (2014).

Peng, L. et al. Ultrahigh thermal conductive yet superflexible graphene films. Adv. Mater. 29, 1700589 (2017).

Malekpour, H. et al. Thermal conductivity of graphene laminate. Nano Lett. 14, 5155–5161 (2014).

Wang, M. et al. Crack-free and scalable transfer of carbon nanotube arrays into flexible and highly thermal conductive composite film. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 539–544 (2014).

Wang, M. et al. Wafer-scale transfer of vertically aligned carbon nanotube arrays. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 18156–18162 (2014).

Teng, C. et al. Ultrahigh conductive graphene paper based on ball-milling exfoliated graphene. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1700240 (2017).

Barani, Z. et al. Thermal properties of the binary-filler hybrid composites with graphene and copper nano particles. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1904008 (2020).

Balandin, A. A. Thermal properties of graphene and nanostructured carbon materials. Nat. Mater. 10, 569–581 (2011).

Yan, Z., Liu, G. X., Khan, J. M. & Balandin, A. A. Graphene quilts for thermal management of high-power GaN transistors. Nat. Commun. 3, 827 (2012).

Xin, G. et al. Large-area freestanding graphene paper for superior thermal management. Adv. Mater. 26, 4521–4526 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. Improved heat spreading performance of functionalized graphene in microelectronic device application. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 4430–4435 (2015).

Renteria, J. D. et al. Strongly anisotropic thermal conductivity of free-standing reduced graphene oxide films annealed at high temperature. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 4664–4672 (2015).

Galiffi, E., Pendry, J. B. & Huidobro, P. A. Broadband tunable thz absorption with singular graphene metasurfaces. ACS Nano 12, 1006–1013 (2018).

Amin, M., Siddiqui, O., Abutarboush, H., Farhat, M. & Ramzan, R. A THz graphene metasurface for polarization selective virus sensing. Carbon 176, 580–591 (2021).

Wang, D. et al. Active wavefronts control with graphene-functionalized terahertz metasurfaces. Diam. Relat. Mater. 124, 108919 (2022).

Guo, G. X. et al. Programmable graphene metasurface for terahertz propagation control based on electromagnetically induced transparency. Carbon 208, 345–354 (2023).

Wang, C., Zhou, R. Y., Huang, Y. X., Xie, L. J. & Ying, Y. B. Terahertz spectroscopic imaging with discriminant analysis for detecting foreign materials among sausages. Food Control 97, 100–104 (2019).

Frank, T. et al. Discriminating between coherent and incoherent light with planar metamaterials. Nano Lett. 19, 6869–6875 (2019).

Siday, T. et al. Terahertz detection with perfectly-absorbing photoconductive metasurface. Nano Lett. 19, 2888–2896 (2019).

Jones, I., Rainsford, T. J., Mickan, S. P. & Abbott, D. Ab initio molecular orbital theory: a tool for THz spectroscopic investigation. Photon. Des. Technol. Packag. 60381I (2005).

Zheng, Y. et al. Metasurface-assisted wireless communication with physical level information encryption. Adv. Sci. 9, 2204558 (2022).

Siegel, P. H. Terahertz technology in biology and medicine. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 52, 2438–2447 (2004).

Yang, X. et al. Biomedical applications of terahertz spectroscopy and imaging. Trends Biotechnol. 34, 810–824 (2016).

Barulin, A., Nguyen, D. D., Kim, Y., Ko, C. & Kim, I. Metasurfaces for quantitative biosciences of molecules, cells, and tissues: sensing and diagnostics. ACS Photon. 11, 904–916 (2024).

Luo, X. Z. et al. Metal–graphene hybrid terahertz metasurfaces for circulating tumor dna detection based on dual signal amplification. ACS Sens. 9, 2122–2133 (2024).

Zhang, S., Genov, D. A., Wang, Y., Liu, M. & Zhang, X. Plasmon-induced transparency in metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 047401 (2008).

Papasimakis, N., Fedotov, V. A., Zheludev, N. I. & Prosvirnin, S. L. Metamaterial analog of electromagnetically induced transparency. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 253903 (2008).

Singh, R., Rockstuhl, C., Lederer, F. & Zhang, W. Coupling between a dark and a bright eigenmode in a terahertz metamaterial. Phys. Rev. B 79, 085111 (2009).

Gu, J. et al. Active control of electromagnetically induced transparency analogue in terahertz metamaterials. Nat. Commun. 3, 1151 (2012).

Manjappa, M., Srivastava, Y. K. & Singh, R. Lattice-induced transparency in planar metamaterials. Phys. Rev. B 94, 161103 (2016).

Cong, L. & Singh, R. Symmetry-protected dual bound states in the continuum in metamaterials. Adv. Opt. Mater. 7, 1900383 (2019).

Chiam, S. Y. et al. Analogue of electromagnetically induced transparency in a terahertz metamaterial. Phys. Rev. B 80, 153103 (2009).

Lin, T. et al. Field manipulation of electromagnetically induced transparency analogue in terahertzmetamaterials for enhancing liquid sensing. Opt. Lasers Eng. 157, 107127 (2022).

Yahiaoui, R. et al. Electromagnetically induced transparency control in terahertz metasurfaces based on bright-bright mode coupling. Phys. Rev. B 97, 155403 (2018).

Trunov, M. A., Umbrajkar, S. M., Schoenitz, M., Mang, J. T. & Dreizin, E. L. Oxidation and melting of aluminum nanopowders. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 13094–13099 (2006).

Firmansyah, D. A. et al. Microstructural behavior of the alumina shell and aluminum core before and after melting of aluminum nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 404–411 (2012).

Ordal, M. A., Bell, R. J., Alexander, R. W., Long, L. L. & Querry, M. R. Optical properties of Au, Ni, and pb at submillimeter wavelengths. Appl. Opt. 26, 744 (1987).

Cong, L., Xu, N., Zhang, W. & Singh, R. Polarization control in terahertz metasurfaces with the lowest order rotational symmetry. Adv. Opt. Mater. 3, 1176–1183 (2015).

Zhang, B. et al. Flexible terahertz spoof plasmonics based on graphene-assembled films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 124, 231703 (2024).

Akbari, A. et al. Highly ordered and dense thermally conductive graphitic films from a graphene oxide/reduced graphene oxide mixture. Matter 2, 1198–1206 (2020).

Reich, S. & Thomsen, C. Raman spectroscopy of graphite. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. Ser. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 362, 2271–2288 (2004).

Trunov, M., Schoenitz, M. & Dreizin, E. Ignition of aluminum powders under different experimental conditions. Propellants Explos Pyrotech. 30, 36–43 (2005).

Bulian, C. J., Kerr, T. & Pusynski, J. A. Ignition studies of aluminum and metal oxide nanopowders. Int. Pyrotech. Semin. Proc. 327–338 (2004).

Trunov, M. A., Schoenitz, M., Zhu, X. & Dreizin, E. L. Effect of polymorphic phase transformations in Al2O3 film on oxidation kinetics of aluminum powders. Combust. Flame 140, 310–318 (2005).

Mičica, M. et al. Spintronic terahertz emitters with integrated metallic terahertz cavities. Nanophotonics 13, 1899–1907 (2024).

Zhang, F., Proust, J., Gérard, D., Plain, J. & Martin, J. Reduction of plasmon damping in aluminum nanoparticles with rapid thermal annealing. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 7429–7434 (2017).

Bosman, M. et al. Encapsulated annealing: enhancing the plasmon quality factor in lithographically–defined nanostructures. Sci. Rep. 4, 5537 (2014).

Jung, Y. S., Sun, Z., Kim, H. K. & Blachere, J. Blueshift of surface plasmon resonance spectra in anneal-treated silver nanoslit arrays. Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 263116 (2005).

Zentgraf, T. et al. Babinet’s principle for optical frequency metamaterials and nanoantennas. Phys. Rev. B 76, 033407 (2007).

Koschny, T., Kafesaki, M., Economou, E. N. & Soukoulis, C. M. Effective medium theory of left-handed materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 107402 (2004).

Chen, M., Xiao, Z., Lv, F., Cui, Z. & Xu, Q. Dynamically tunable electromagnetically induced transparency-like effect in terahertz metamaterial based on graphene cross structures. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quant. Electron. 28, 1–9 (2022).

Yahiaoui, R., Manjappa, M., Srivastava, Y. K. & Singh, R. Active control and switching of broadband electromagnetically induced transparency in symmetric metadevices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 021101 (2017).

Hu, Y. et al. Bi2Se3 - functionalized metasurfaces for ultrafast all-optical switching and efficient modulation of terahertz waves. ACS Photon. 8, 771–780 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12304430), Hubei Key Laboratory for New Textile Materials and Applications (Grant No. FZXCL202312), Foundation of Wuhan Textile University (20220609) and the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (Grants No. 2024AFB888). This work is also supported by the Synergic Extreme Condition User Facility (SECUF), China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.H. wrote the original draft. B.Z. and X.H. were responsible for conceptualization and methodology. W.Q. and Z.W. conducted the analysis and investigation. J.B. and Y. X. prepared the visualizations. W.Z. and W.H. managed the project and acquired funding. W.H. and W.Z. reviewed and edited the manuscript. D.H. and S.W. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, X., Zhang, B., Han, W. et al. Thermostable terahertz metasurface enabled by graphene assembly film for plasmon-induced transparency. Sci Rep 15, 3673 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85309-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85309-3