Abstract

Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) is a widely used scale to assess performance status. KPS ≥ 50% implies that patients can live at home. Therefore, maintaining KPS ≥ 50% is important to improve the quality of life of patients with glioblastoma, whose median survival is less than 2 years. This study aimed to identify the factors associated with survival time with maintenance of KPS ≥ 50% (survival with KPS ≥ 50%) in patients with glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype. Ninety-eight patients with glioblastomas, IDH-wildtype, who were treated with concomitant radiotherapy (RT) and temozolomide (TMZ) followed by maintenance TMZ therapy, and whose KPS at the start of RT was ≥ 50%, were included. The median survival with KPS ≥ 50% was 13.3 months. In univariate analysis, preoperative KPS (≥ 80%), KPS at the start of RT (≥ 80%), residual tumor size (< 2 cm3), methylated MGMT promotor, and implantation of BCNU wafer were associated with survival with KPS ≥ 50%. In multivariate analysis, KPS at the start of RT (≥ 80%), methylated MGMT promotor, and residual tumor size (< 2 cm3) were significantly associated with increased survival with KPS ≥ 50%. A strategy of maximum possible tumor resection without compromising KPS is desirable to prolong the survival time with KPS ≥ 50%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glioblastoma is the most common malignant brain tumor1. The standard treatment is maximal safe resection, followed by radiotherapy (RT) and temozolomide (TMZ)2. Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) of the disease have been reported from data from clinical trials3,4,5. However, only a few studies have investigated the prognostic value of maintaining Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) of patients with glioblastoma6,7.

KPS is a widely used scale to assess performance status. KPS ≥ 50% indicates that patients can live at home and take care of most of their personal needs. Patients with KPS < 50% require the equivalent of institutional or hospital care8. Therefore, there is a significant difference in the quality of life of patients with KPS 40% and those with KPS 50%.

The revision of the classification of brain tumors has led to a change in the diagnostic criteria9,10. In the WHO 2021 classification of the tumors of the central nervous system, gliomas with mutations of isocitrate dehydrogenases 1 and 2 (IDH1/2) are no longer categorized as glioblastoma. Diffuse gliomas without IDH mutations that fulfill one of the following characteristics, i.e., microvascular proliferation, necrosis, TERT promoter mutation, EGFR gene amplification, and + 7/−10 chromosome copy number alterations are now referred to as glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype10.

In this study, we reviewed the data of patients with glioblastomas, IDH-wildtype based on WHO 2021 classification to identify the factors associated with survival time maintaining KPS ≥ 50% (survival with KPS ≥ 50%).

Materials and methods

Patients

The ethics review committee of the Fujita Health University approved this retrospective study (Approval No. HM22-434). Data of patients with glioblastoma who were first operated at the Fujita Health University Hospital between 2007 and 2021 were reviewed. All diagnoses were rereviewed according to the WHO 2021 classification of tumors of the central nervous system10 and only cases with glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype who qualified all the following criteria were included in this study: (1) exclusively supratentorial cases; (2) age ≥ 18 years; (3) treated with concomitant RT and TMZ followed by maintenance TMZ therapy; (4) KPS ≥ 50% at the start of RT.

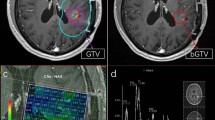

KPS score was determined from the review of medical records. Tumor size was measured from the contrast-enhanced area on MRI performed within 3 days after surgery. In many studies on glioblastoma, the extent of resection has been used to assess residual tumor11,12; however, the size of the residual tumor may vary depending on the preoperative size of the tumor, even if the degree of removal is the same. Therefore, for the purpose of this analysis, the residual tumor volume was categorized into large (≥ 2 cm3) or small (< 2 cm3) based on a previous report13.

Histopathological and molecular assessment

DNA was isolated from frozen tissues or formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kits (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) or DNA FFPE Tissue Kits (QIAGEN), as previously described14. DNA aliquots were subjected to degenerate oligonucleotide-primed polymerase chain reaction (DOP-PCR). Comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) was used to evaluate gain of chromosome 7 and loss of chromosome 10. The detailed procedure for CGH is described elsewhere15.

Mutational analyses of IDH1/2 and TERT promoter were performed using PCR and Sanger sequencing, as previously described14. The following primer sequences were used: forward 5′-CGGTCTTCAGAGAAGCCATT-3′ and reverse 5′-CACATTATTGCCAACATGAC-3′ for IDH1 gene; forward 5′-CTCACAGAGTTCAAGCTGAAGAAG-3′ and reverse 5′- CTGTGGCCTTGTACTGCAGAG-3′ for IDH2 gene; and forward 5′-CAGCGCTGCCTGAAACTC-3′ and reverse 5′-GTCCTGCCCCTTCACCTT-3′ for TERT promoter gene. The sequence analysis was performed using an ABI Prism 3100 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA).

MGMT promoter methylation was measured by methylation-specific PCR using the EZ DNA Methylation-Direct™ Kit (Zymo Research Corp., Orange, CA) as previously described16.

Paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinized, placed in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 7.0), processed five times for four minutes in a microwave oven at 600 W, and incubated overnight at 4 °C with monoclonal antibody Ki-67 (1:25 dilution) (clone MIB-1; BioGenex, Fremont, CA, USA) in PBS containing 5% bovine serum albumin and 3% horse serum. The MIB-1 index was calculated as the percentage of tumor cell nuclei immunolabeled for anti-Ki67 antibody, for a total of 1,000 tumor cell nuclei, as previously described17.

Statistical analysis

We examined the influence of the following factors on survival time with maintenance of KPS ≥ 50%: sex, age, preoperative KPS, KPS at the start of RT, residual tumor size, treatment with bis-chloroethyl nitrosourea (BCNU) wafer, treatment with bevacizumab, the status of methylation of MGMT promoter, and MIB-1 index.

All analyses were performed using JMP software (version 13; SAS Institute Japan, Tokyo, Japan). PFS was defined as the time from the date of first surgery to the date of confirmation of tumor recurrence/regrowth, or patient death. Tumor recurrence was determined using the Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) criteria based on MRI findings. The survival time with maintenance of KPS ≥ 50 was defined as the time from the date of initial surgery to a KPS < 50%. OS was defined as the period between the date of first surgery and the date of death or last follow-up. Survival outcomes were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and between-group differences were assessed using the log rank test. Multivariate proportional hazards regression analysis was used to identify the factors associated with maintenance of KPS ≥ 50. P values < 0.05 were considered indicative of statistical significance.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 152 patients underwent surgery and were diagnosed with glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype during the study reference period. Of these, 98 patients qualified the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were included in this study (Fig. 1). The characteristics of the study population are summarized in Table 1. Sixty patients (61.2%) were male and 38 (38.8%) were female. The mean and median age of the patients at surgery was 62.8 ± 12.5 years and 66 years, respectively. The distribution of preoperative KPS scores in our cohort was as follows: 100% (8 patients), 90% (39 patients), 80% (30 patients), 70% (9 patients), 60% (11 patients), and 50% (1 patient); the average preoperative KPS was 82.1% ± 11.5%. The distribution of KPS scores at the start of RT was as follows: 100% (2 patients), 90% (30 patients), 80% (26 patients), 70% (18 patients), 60% (12 patients), and 50% (10 patients); the average KPS at the start of RT was 76.1% ± 13.6%. Histologically, ninety-five cases were diagnosed as glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype due to microvascular proliferation and/or necrosis, whereas three cases were histologically diagnosed as malignant astrocytoma harboring IDH-wildtype and molecularly diagnosed as glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype. The status of methylation of MGMT promoter was checked in 90 patients, and methylation of MGMT promoter was found in 43 cases (47.8%). MIB-1 index ranged from 6.3 to 67.3% with an average of 34.7%. BCNU wafer was implanted in 64 cases (65.3%), and 51 patients (52.0%) received bevacizumab treatment before KPS decreased below 50%.

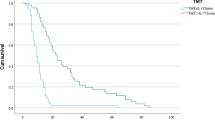

PFS, OS, and survival with KPS ≥ 50%

The median PFS, OS, and survival with KPS ≥ 50% were 7.1 months, 19.4 months, and 13.3 months, respectively (Fig. 2). The survival time with KPS ≥ 50% was longer than PFS.

Preoperative KPS, KPS at the start of RT, and survival with KPS ≥ 50%

First, we analyzed the relationship of survival with KPS ≥ 50% with preoperative KPS or KPS at the start of RT. Compared with patients with preoperative KPS ≤ 60%, patients with preoperative KPS ≥ 70% tended to show longer survival maintaining KPS ≥ 50% (p = 0.099), and compared with patients with preoperative KPS ≤ 70%, patients with preoperative KP ≥ 80% showed significantly longer survival maintaining KPS ≥ 50% (p = 0.0039); however there was no significant difference between patients with preoperative KPS ≥ 90% and ≤ 80% (p = 0.246) (Fig. 3). Regarding the contribution of KPS at the start of RT, although significant differences were observed between the two groups regardless of whether the cutoff value was set at 90%, 80%, or 70%, the most significant difference was observed using 80% as the cutoff value (Fig. 4). Therefore, we used the 80% cutoff value for both preoperative KPS and KPS at the start of RT.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with survival with KPS ≥ 50%

Several factors (sex, age, preoperative KPS, KPS at the start of RT, residual tumor size, status of MGMT promotor methylation, BCNU wafer implantation, treatment with bevacizumab, and MIB1-index) were analyzed to assess their potential association with survival with KPS ≥ 50%. Young age (< 65 years) group tended to show longer survival with KPS ≥ 50% (p = 0.053). Preoperative KPS (≥ 80%), KPS at the start of RT (≥ 80%), residual tumor size (< 2 cm3), methylated MGMT promotor, and implantation of BCNU wafer were found to be associated with survival with KPS ≥ 50% (Table 2; Fig. 5). In multivariate analysis, KPS at the start of RT (≥ 80%), methylated MGMT promotor, and residual tumor size (< 2 cm3) were associated with significantly longer survival with KPS ≥ 50%. Young age (< 65 years) tended to be associated with survival with KPS ≥ 50% (Table 2). The median survival with KPS ≥ 50% in groups harboring all three favorable factors (KPS at the start of RT [≥ 80%], methylated MGMT promotor, and residual tumor size [< 2 cm3]), two favorable factors, one favorable factor, and none of the favorable factors were 28.57, 15.39, 11.64, and 5.80 months, respectively (Fig. 6).

(a) The survival time with maintenance of KPS ≥ 50% in patients with residual tumor size ≥ 2 cm3 versus < 2 cm3. (b) The survival time with maintenance of KPS ≥ 50% in patients with methylated MGMT promoter versus those with unmethylated MGMT promoter. (c) The survival time with maintenance of KPS ≥ 50% in patients treated with BCNU wafer versus those not treated with BCNU wafer. The median survival time with maintaining KPS ≥ 50 for each group is provided in Table 2.

Discussion

Many studies about glioblastoma have focused on the survival time3,4,5. Because of the poor prognosis of glioblastoma, maintaining KPS is considered another goal of management. In this study of 98 cases of glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype treated with concomitant RT and TMZ, followed by maintenance TMZ, three factors (KPS at the start of RT [≥ 80%], methylated MGMT promotor, and residual tumor size [< 2 cm3]) were found to be associated with longer survival with maintenance of KPS at ≥ 50%. The results suggest that reducing the residual tumor size to less than 2 cm3 and not allowing the KPS at the start of RT to fall below 80% can help increase the survival time with maintenance of KPS at ≥ 50%.

Previous studies have highlighted the significant impact of the extent of resection on survival outcomes in glioblastoma patients18,19,20. Our findings are consistent with these reports, showing that patients with smaller residual tumors (< 2 cm³) were more likely to maintain a KPS ≥ 50. This underscores the importance of maximal safe resection in improving both survival and quality of life in glioblastoma patients. Furthermore, meta-analyses and recent studies confirm that gross total resection (GTR) significantly improves survival outcomes compared to subtotal resection (STR) or biopsy alone, and that minimizing residual tumor volume provides additional benefits. These findings highlight the critical role of safe but aggressive surgical approaches in optimizing patient outcomes.

In univariate analysis, both preoperative KPS and KPS at the start of RT were related to the duration of KPS maintenance, but in multivariate analysis, only KPS at the start of RT was found to significantly influence the survival time with maintenance of KPS ≥ 50%. Thus, the KPS at the start of RT showed a stronger relationship with KPS maintenance than preoperative KPS. Similar results were reported in a previous study investigating the relationship between KPS and OS, where postoperative KPS was strongly associated with prolonged survival rather than preoperative KPS6,21.

Although bevacizumab has been reported to prolong KPS in Avaglio trial3, bevacizumab was not revealed to be a prognostic factor. This discrepancy may be attributed to the way bevacizumab is used. In Japan, bevacizumab is covered by insurance for use at the time of initial or recurrent disease. In our institution, bevacizumab is used in initial therapy when there is a large residual tumor and the patient’s KPS is low, and at recurrence when the patient’s KPS is high. Furthermore, there are 8 patients who have not yet used bevacizumab tumors and have maintained a KPS of 50 or higher. Based on the above, we believe that bevacizumab could not be extracted as a predictor of KPS maintenance.

Several previous studies have measured functional outcomes in patients with glioma, but most of these studies included several histological types of gliomas22,23. Only a few studies have evaluated the factors associated with maintaining KPS exclusively in patients with glioblastoma6,7. Chaichana et al. investigated the factors associated with functional independence (KPS ≥ 60%) following surgery in a cohort of 544 patients with primary and secondary glioblastomas. They found that preoperative KPS ≥ 90%, seizures, primary glioblastoma, gross-total resection, and TMZ were associated with improved functional outcome, whereas older age, coronary artery disease, and new postoperative motor deficit were associated with decreased functional outcome. In their study, 40% of cases had secondary glioblastoma. However, in the present study, we only included patients with IDH-wildtype diffuse glioma with one of the following characteristics: TERT promoter mutation, EGFR amplification, and gain of chromosome 7 and loss of chromosome 10 (the so-called molecular glioblastoma)24, in addition to histological IDH-wildtype glioblastoma, based on 2021 WHO classification of central nervous system tumors10. For glioblastoma, the combination of radiotherapy and TMZ is the standard therapy, and most patients have received these treatments. In their study, TMZ was used in only 29% of the patients. However, our study included only those who underwent these treatments, because it is important to identify the factors associated with maintenance of KPS among patients treated with standard treatment. The status of methylation of MGMT promoter has been recognized as a prognostic and predictive factor in glioblastoma25. Patients with methylated MGMT promoter show better responses to temozolomide and longer survival, consistent with our findings. In contrast, MGMT-unmethylated glioblastomas remain a significant challenge, emphasizing the need for novel therapeutic approaches to improve outcomes in this subgroup26,27. Because the maintenance of KPS is associated with survival time and response to treatment, the status of MGMT promoter methylation should be included in the analysis.

Sacko et al. reported that surgical resection (compared to biopsy) and low steroid dosage at RT onset were associated with longer survival time with functional independence7. Their study was limited to 84 cases of glioblastoma initially treated with concomitant RT and TMZ. Although their study was targeted at relatively uniform tumors, the status of IDH1/2 was not checked. Because IDH1/2 mutation is a driver mutation of IDH-mutant glioma and is associated with prognosis, IDH-mutant glioma has been distinguished from glioblastoma10,28. Moreover, as in the study of Chaichana et al., MGMT was not checked in their study.

Our findings suggest that maintaining KPS at the start of RT is important to prolong survival with KPS ≥ 50%. One way to reduce surgical dysfunction is to perform awake surgery29. Because of the rapid progression of glioblastoma, surgery is recommended as early as possible. However, owing to the need for various preoperative preparations, awake surgery is difficult to perform for glioblastoma. However, in recent studies, OS or PFS of patients with IDH-wildtype glioblastoma was not significantly different between groups that underwent surgery ≤ 7 days, > 7–21 days, or > 21 days from initial imaging30. Thus, it may be desirable to actively perform awake surgery even for glioblastoma to maintain KPS, even if the time to surgery is somewhat longer.

Some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the relatively small sample size (n = 98) may restrict the generalizability of our findings. Future studies with larger cohorts are warranted to confirm the observed associations and to further investigate other potential factors affecting KPS maintenance in glioblastoma patients. Additionally, this was a retrospective study and the results may not be generalizable to all patients harboring glioblastoma. Approximately 1/3 of patients were excluded from this study because our study was limited to patients whose KPS at the start of RT was ≥ 50% and were treated with radiotherapy and TMZ. Finally, this study did not assess the contribution of Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) to the maintenance of KPS. TTFields has been reported to prolong OS and has recently been incorporated into therapy31. However, it was excluded from the list of variables because it was used in only 7 patients (7.1%) enrolled in this study. In addition, while most patients received the standard Stupp protocol (60 Gy in 30 fractions), hypofractionated regimens (40.5 Gy in 15 fractions or 25 Gy in 5 fractions) were used for elderly patients. Although these variations are unlikely to have significantly influenced the results, their potential impact on maintaining KPS > 50 warrants further investigation. Compared to previous reports, notable features of our study are the uniformity of diagnosis and treatment, and the fact that the status of MGMT promoter was investigated.

In conclusion, for patients of glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype treated with radiotherapy and TMZ, KPS ≥ 80% at the initiation of RT, methylated MGMT promotor, and residual tumor size < 2 cm3 were associated with longer survival time with maintenance of KPS at ≥ 50%. Since the status of MGMT promoter is identified postoperatively, neurosurgeons should endeavor to perform maximum possible surgical resection of the tumor without compromising the KPS at the start of radio-chemotherapy to prolong the period of KPS ≥ 50%.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Reni, M., Mazza, E., Zanon, S., Gatta, G. & Vecht, C. J. Central nervous system gliomas. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 113, 213–234 (2017).

Ohba, S. & Hirose, Y. Current and future drug treatments for glioblastomas. Curr. Med. Chem. 23, 4309–4316 (2016).

Chinot, O. L. et al. Bevacizumab plus radiotherapy-temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 709–722 (2014).

Gilbert, M. R. et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 699–708 (2014).

Stupp, R. et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 987–996 (2005).

Chaichana, K. L. et al. Factors involved in maintaining prolonged functional independence following supratentorial glioblastoma resection. Clinical article. J. Neurosurg. 114, 604–612 (2011).

Sacko, A. et al. Evolution of the Karnosky Performance Status throughout life in glioblastoma patients. J. Neurooncol. 122, 567–573 (2014).

Karnofsky, D. A. et al. The use of nitrogen mustards in the palliative treatment of carcinoma: With particular reference to bronchogenic carcinoma. Cancer 1, 634–656 (1948).

Louis, D. N. et al. The 2016 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary. Acta Neuropathol. 131, 803–820 (2016).

Louis, D. N. et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary. Neuro Oncol. 23, 1231–1251 (2021).

Lacroix, M. et al. A multivariate analysis of 416 patients with glioblastoma multiforme: Prognosis, extent of resection, and survival. J. Neurosurg. 95, 190–198 (2001).

Sanai, N., Polley, M. Y., McDermott, M. W., Parsa, A. T. & Berger, M. S. An extent of resection threshold for newly diagnosed glioblastomas. J. Neurosurg. 115, 3–8 (2011).

Grabowski, M. M. et al. Residual tumor volume versus extent of resection: predictors of survival after surgery for glioblastoma. J. Neurosurg. 121, 1115–1123 (2014).

Kuwahara, K. et al. Clinical, histopathological, and molecular analyses of IDH-wild-type WHO grade II-III gliomas to establish genetic predictors of poor prognosis. Brain Tumor Pathol. 36, 135–143 (2019).

Hirose, Y., Aldape, K., Takahashi, M., Berger, M. S. & Feuerstein, B. G. Tissue microdissection and degenerate oligonucleotide-primed polymerase chain reaction (DOP‐PCR) is an effective method to analyze genetic aberrations in invasive tumors. J. Mol. Diag. 3, 62–67 (2001).

Ezaki, T. et al. Molecular characteristics of pediatric non-ependymal, nonpilocytic gliomas associated with resistance to temozolomide. Mol. Med. Rep. 4, 1101–1105 (2011).

Ohba, S. et al. c-Met expression is a useful marker for prognosis prediction in IDH-mutant lower-grade gliomas and IDH-wildtype glioblastomas. World Neurosurg. 126, e1042–e1049 (2019).

Brown, T. J. et al. Association of the extent of resection with survival in glioblastoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2, 1460–1469 (2016).

Hallaert, G. et al. Partial resection offers an overall survival benefit over biopsy in MGMT-unmethylated IDH-wildtype glioblastoma patients. Surg. Oncol. 35, 515–519 (2020).

Karschnia, P. et al. Prognostic validation of a new classification system for extent of resection in glioblastoma: A report of the RANO resect group. Neuro Oncol. 25, 940–995 (2023).

Chambless, L. B. et al. The relative value of postoperative versus preoperative Karnofsky performance scale scores as a predictor of survival after surgical resection of glioblastoma multiforme. J. Neurooncol. 121, 359–564 (2015).

Bussière, M. et al. Indicators of functional status for primary malignant brain tumour patients. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 32, 50–56 (2005).

Recht, L., Glantz, M., Chamberlain, M. & Hsieh, C. C. Quantitative measurement of quality outcome in malignant glioma patients using an independent living score (ILS). Assessment of a retrospective cohort. J. Neurooncol. 61, 127–136 (2003).

Brat, D. J. et al. cIMPACT-NOW update 3: Recommended diagnostic criteria for diffuse astrocytic glioma, IDH-wildtype, with molecular features of glioblastoma, WHO grade IV. Acta Neuropathol. 136, 805–810 (2018).

Hegi, M. E. et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 352, 997–1003 (2005).

Kreth, F. W. et al. Gross total but not incomplete resection of glioblastoma prolongs survival in the era of radiochemotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 24, 3117–3123 (2013).

Sim, H. W. et al. A randomized phase II trial of veliparib, radiotherapy, and temozolomide in patients with unmethylated MGMT glioblastoma: The VERTU study. Neuro Oncol. 23, 1736–1749 (2021).

Ohba, S. & Hirose, Y. Biological significance of mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 in gliomagenesis. Neurol. Med. Chir. (Tokyo). 56, 170–179 (2016).

De Witt Hamer, P. C., Robles, S. G., Zwinderman, A. H., Duffau, H. & Berger, M. S. Impact of intraoperative stimulation brain mapping on glioma surgery outcome: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 30, 2559–2565 (2012).

Young, J. S. et al. Does waiting for surgery matter? How time from diagnostic MRI to resection affects outcomes in newly diagnosed glioblastoma. J. Neurosurg. 140, 80–93 (2023).

Stupp, R. et al. Effect of tumor-treating fields plus maintenance temozolomide vs maintenance temozolomide alone on survival in patients with glioblastoma: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 318, 2306–2316 (2017).

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Shigeo Ohba, Takao Teranishi, Masanobu Kumon, Daijiro Kojima, Kiyonori Kuwahara, Eriel Sandika Pareira, and Hikaru Sasaki. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Shigeo Ohba and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Fujita Health University (Approval No. HM22-434).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ohba, S., Teranishi, T., Matsumura, K. et al. Factors involved in maintaining Karnofsky Performance Status (≥ 50%) in glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype patients treated with temozolomide and radiotherapy. Sci Rep 15, 1750 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85339-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85339-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Awake craniotomy for brain tumor resection in the elderly: an institutional experience

Journal of Neuro-Oncology (2026)

-

GlioSurv: interpretable transformer for multimodal, individualized survival prediction in diffuse glioma

npj Digital Medicine (2025)