Abstract

Optimizing oocyte maturation and embryo culture media could enhance in vitro embryo production. The purpose of the present study was to investigate the role of supplementing one carbon metabolism (OCM) substrates and its cofactors (Cystine, Zinc, Betaine, B2, B3, B6, B12 and 5-methyltetrahydrofolate) in maturation and/or embryo culture media on the rate of blastocyst formation and pregnancy outcomes following the transfer of the resulting blastocysts in bovines. In the first experiment, 2537 bovine oocytes were recovered from slaughterhouse ovaries and then matured either in conventional maturation medium (IVM) or IVM supplemented with OCM substrates (Sup-IVM). After in vitro fertilization, the putative zygotes from each treatment (IVM or Sup-IVM) were cultured in the media either without (IVM/IVC or Sup-IVM/IVC) or with (IVM/Sup-IVC or Sup-IVM/Sup-IVC) OCM supplementation. The blastocyst rate, assessed on day 8, was significantly increased in Sup-IVM/IVC group (34.90 ± 2.52) as compared to IVM/IVC (17.06 ± 1.69; P = 0.0001) and Sup-IVM/Sup-IVC (20.29 ± 2.75; P = 0.004) and non-significantly as compared to IVM/Sup-IVC (24.86 ± 5.37). In the second experiment, non-matured bovine oocytes were collected by transvaginal ovum pick up after FSH stimulation, randomly allocated into IVM/IVC (n = 275) and Sup-IVM/IVC (n = 260) and the blastocysts achieved at day 7 were transferred in recipient cattle. The blastocyst rate was significantly higher in Sup-IVM/IVC group (38.85%) as compared to the IVM/IVC group (23.64%; P < 0.0001). After single embryo transfer, the supplemented blastocysts were at least as competent as non-supplemented ones with a non-significantly higher (20% vs. 14%) pregnancy rate and the advantage of several good quality blastocysts available for future use. In conclusion, optimizing the maturation medium with OCM substrates and its cofactors could enhance the formation of viable blastocysts with the potential to increase the cumulative birth rate in cattle.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The preimplantation period is a critical stage in embryonic development that occurs during the first few days following fertilization. During this period, complex developmental and molecular processes take place, including fertilization, cleavage, genomic activation, and blastulation. These processes are regulated by epigenetic mechanisms and chromatin remodeling, which significantly affect postnatal health and phenotype1,2,3. Optimizing in vitro maturation (IVM) and in vitro culture (IVC) media by simulating the in vivo cellular niche and microenvironment is considered as a key approach for enhancing in vitro embryo production4,5.

The One-Carbon Metabolism (OCM) is essential for various cellular processes, including cell growth, epigenetic regulation, and antioxidant defense and consists of several interconnected pathways: The methionine and folate cycles, the betaine pathway and the trans-sulfurations6. In the methionine cycle, methionine is activated by adenylation to S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe); After serving as the universal methyl donor for methyl transferases, SAMe generates S-adenosylhomocysteine, which is then converted into homocysteine. Homocysteine can be re-methylated to complete the cycle. Alternatively, homocysteine can be transsulfurated to cystathionine and then cysteine to feed the de-novo glutathione (GSH) synthesis.

The OCM strictly depends on the availability of several substrates and co-factors sourced from diet and/or endogenous metabolism. These include the methyl donors 5-methyl tetrahydrofolate (5MTHF) and methylcobalamin feeding the re-methylation of homocysteine by methionine synthase (MS), and betaine, generated in mitochondria from choline oxidation7, feeding homocysteine re-methylation by betaine homocysteine methyl Transferase (BHMT). The transsulfuration of homocysteine to cystathionine and then cysteine is operated by the enzymes cystathionine beta synthase (CBS) and cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) whose activity is vitamin B6 dose-dependent8. Both MS and BHMT enzyme proteins function through zinc fingers, which are also essential for the activity of DNA methyl transferases and play a crucial role in methylation epigenetics9 and this makes the OCM also dependent on adequate zinc availability. Finally, the key enzyme methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR), responsible for the endogenous synthesis of 5MTHF, requires NADPH/niacin as the source of reducing equivalents and vitamin B2/FAD as the coenzyme (Fig. 1). In clinical trials, the oral supplementation of physiological amounts of these micronutrients was extremely effective in reducing blood homocysteine in both men10 and women11, which confirms the dependence of the OCM on the daily diet and its sensitivity to the manipulation of these substrates.

Based on the evidence mentioned above, we have recently reported12 that IVM supplementation of bovine oocytes with the aforementioned OCM substrates and cofactors improved the mitochondrial mass and DNMT3A protein expression in oocytes, the DNA integrity of both oocyte and granulosa cells, the DNA methylation level of female pronuclei in the zygotes and, thereafter, the blastocyst rate. These positive outcomes were achieved with supplementation limited to the 24 h of IVM, suggesting a lingering effect from adequate oocyte nourishment. however, it also suggests that maintaining this support during the embryo culture might further improve the outcomes. To this aim, in the present study we extended the supplementation with the same substrates to the phase of IVC. Subsequently, in a second experiment, in order to confirm that the blastocysts achieved by substrate supplementation are also developmentally competent, we also tested their ability to implant and to give a viable pregnancy after transfer in recipient cattle.

Results

Experiment 1

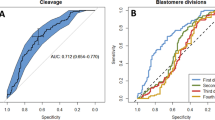

A total of 2537 oocytes were collected and randomly allocated to one of the 4 groups (Fig. 2A). The cleavage rate did not differ between groups and was always above 80% (data not shown). The blastocyst rate (Fig. 3) was higher in the Sup-IVM/IVC group (34.90 ± 2.52%; n = 600) compared to IVM/IVC (17.06 ± 1.69%; n = 1051; P = 0.0001) and to Sup-IVM/Sup-IVC (20.29 ± 2.75%; n = 563; P = 0.004) groups but was not different from the IVM/Sup-IVC group (24.86 ± 5.37%; n = 323; P = 0.128). There were no other statistically significant differences between the groups.

Study design for Experiment 1 (A) and Experiment 2 (B). IVM: In vitro maturation; IVC: In vitro culture; IVF: In vitro fertilization; IVM/IVC: Neither IVM nor IVC medium was supplemented; Sup-IVM/IVC: Only maturation medium supplemented with one carbon substrates and cofactors; IVM/Sup-IVC: Only embryo culture medium supplemented with one carbon substrates and cofactors; Sup-IVM/Sup-IVC: Both maturation medium and embryo culture medium supplemented with one carbon substrates and cofactors.

Experiment 1. Blastocyst rates in treatment groups. IVM/IVC: neither IVM nor IVC medium was supplemented, Sup-IVM/IVC: Only maturation medium supplemented with one carbon substrates and cofactors. IVM /Sup-IVC: Only embryo culture medium supplemented with one carbon substrates and cofactors. Sup-IVM/Sup-IVC: Both maturation medium and embryo culture medium supplemented with one carbon substrates and cofactors. Different letters stand for significant differences.

Experiment 2

A total of 535 immature COCs were collected from 32 donors and were randomly allocated to either supplemented (Sup-IVM/IVC, n = 260 COCs) or non-supplemented (IVM/IVC, n = 275 COCs) IVM (Fig. 2B). As depicted in Table 1, the blastocyst rate in Sup-IVM/IVC (38.85%) was higher than IVM/IVC group (23.64%; P < 0.0001).

The IVM/IVC group had 50 excellent or good quality blastocysts (50 out of 65 = 76.9%) and all of them were transferred in recipient cattle. The Sup-IVM/IVC had 84 excellent or good quality blastocysts (84 out of 101 = 84%), 60 of them were transferred in recipient cattle and 24 remained available for future use. The above single embryo transfers resulted in, respectively, 7 (14%) and 12 (20%) live births, which did not reach statistical significance. The ongoing pregnancies and the live births are detailed in Table 2.

Discussion

An adequate function of the OCM and its methylation, along with its antioxidant output, plays a primary role in reproduction, affecting all phases of the process, from gametogenesis to embryo development, and the issue might be even more relevant in case of in-vitro manipulation of gametes and embryos13. The OCM is strictly dependent on the timed availability of its substrates, which depends on the diet in vivo as well as from the culture media composition in vivo. Animal models have already shown that the OCM is upregulated during oocyte meiotic resumption14, which may represent a period of increased risk for metabolic failure. Accordingly, We have already demonstrated that supplementing the maturation medium of bovine oocytes with OCM substrates was able to double the rate of zygotes eventually resulting into a blastocyst after IVC12. Downstream to oocyte maturation, it is well described that after fertilization a wide global DNA de-methylation occurs, which is followed by a peak of re-methylation at time of blastocyst expansion15. This phase of intensive re-methylation has been confirmed also in cows16 and may carry a risk of OCM failure. Therefore, in this study, we evaluated the effect on blastocyst rates of extending supplementation from oocyte maturation to the final stages of blastocyst expansion (Experiment 1).

Our data confirm the positive effect of the supplementation of the IVM medium with substrates and co-factors of the OCM on the blastocyst rate of bovine embryos. Just like already shown in a previous study12, the blastocyst rate of IVM-supplemented embryos was roughly doubled as compared to non-supplemented controls. Thus, the enhancement of the OCM candidates as a tool to increase the yield from IVM in animal breeding and, possibly, in human IVM. Further translating to human reproduction, these findings also endorse the importance of an adequate diet, and/or supplementation for expectant mothers, as only well-nourished oocytes seem capable of initiating a viable pregnancy. The supplementation during IVC instead of IVM resulted in a non-significantly lower blastocyst rate as compared to IVM supplementation and a non-significantly higher blastocyst rate as compared to non-supplemented controls. The smaller sample size of this group may account for the lack of statistical significance in both comparisons. It is also possible that the increased demand at time of re-methylation in blastocysts is of minor entity compared to the peak of demand occurring in maturing oocytes, which reflects in the different effect size of the supplementation. However, based on crude blastocyst rates, the IVM supplementation appeared to be better than the IVC supplementation that was itself better than having no supplementation at all.

Extending the supplementation to both the IVM and the IVC phase did not further improve the outcomes. In fact, it appeared to be detrimental, as the oocytes supplemented in both phases produced significantly less blastocyst than those supplemented only during IVM. The reason for this decline is not in a possible low tolerability to the supplements in the IVC phase because the oocytes supplemented only during IVC behaved quite well. Thus, the reason seems to be in an excess of supplementation. Methyl donors are powerful inducers of GSH synthesis17 and the extended supplementation may have generated a condition of reductive stress, i.e. a redox imbalance toward excessive reducing power18. However, our study did not check the redox balance and the above explanation remains speculative.

Pending further investigations on OCM supplementation in IVC, a positive effect of OCM support during IVM on the blastocyst rate appears plausible and confirmed by the present data. However, it was also possible that the supplementation forced to final development also zygotes from oocytes with intrinsic problems leading to non-viable extra blastocysts, i.e. that the improved yield was just cosmetic. Moreover, it has been suggested that a main reason for OCM failure in assisted reproduction is the increased relative metabolic demand from FSH stimulation and multiple follicle development13, thus slaughterhouse collected oocytes (experiment 1) might have been a best case compared to in vivo FSH-stimulated oocytes.

To address these questions, in Experiment 2 we tested the pregnancy outcomes from the transfer of blastocysts obtained from oocytes aspirated from FSH-stimulated heifers and supplemented during IVM. Also, in the IVM of FSH-stimulated oocytes, the supplementation of the OCM resulted in a significant increase of the final blastocyst rate and with a similar amplitude. Therefore, if any increased demand was in place, it appeared to be compensated by the supplements. In addition, the blastocysts obtained from IVM-supplemented oocytes were at least as viable and developmentally competent as those obtained by non-supplemented IVM showing overlapping, if not better, live birth rates. Moreover, the IVM-supplemented group had an extra of 24 blastocysts available for future use, which might further expand the increased yield. This might have a true economic relevance in the expansion of the farms livestock and would be of even higher value if confirmed in the clinical setting. In a recent clinical trial19 aimed at evaluating the efficacy of the same supplementation in PCOS women undergoing ART, the supplemented women reported a blastocyst rate that was, again, twice that of the control group (55% vs. 32%; p = 0.0009), which was also reflected in pregnancy rates (58% vs. 33%; n.s.).

The final mechanisms by which the enhancement of the OCM in oocytes increases the blastocyst rate remains to be elucidated. In the previous study12 we showed increased methylation of the female pronuclei in zygotes from supplemented oocytes, which fits with the findings of other studies pointing to the importance of the OCM in epigenetic regulation20. However, we could not demonstrate any quality difference between the IVM-supplemented vs. non-supplemented blastocysts, only the number was increased. This indicated the existence of a metabolic check-point based on OCM performance with no further differences once the threshold was satisfied. Such an “all or nothing” response well fits with our understanding of the effect of oocyte aneuploidy on blastocyst development. DNA methylation restrains transposons from adopting a chromatin signature permissive for meiotic recombination and may prevent the occurrence of erratic chromosomal events21. Oocyte aneuploidy during bovine oocyte IVM has been shown to be around 30% 22 and its prevention might explain the increased gain in blastocyst from supplemented oocytes. However, the aneuploidy rate was not checked and the issue will have to be further investigated.

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first study investigating the role of OCM supplementation in bovine IVC and we did it using a large number of oocytes, nevertheless some reasons for caution are to be considered. The main weakness of our study was the imbalanced sample size across groups, which may have hampered the statistical analysis in some cases. Moreover, the large size and the use of an in vivo experiment did not allow us to deepen our analyses and we had to infer on the data from the previous study on the same model to explain the mechanisms. In the in vivo experiment the oocyte donors and the embryo recipients were different animals of different ages, which resembles an oocyte donation program in the clinical setting and may serve as a best-case test. It is also worth noting that the pregnancy rate in our control group (14%) which is somewhat lower than expected and might reflect an issue of suboptimal outcomes from the control group as the reason for the differences vs. supplemented group. However, our recipient cows were aged between 46 and 50 months and were in later lactation stages, which is often associated to reduced reproductive performance due to various factors, including age-related declines in fertility, potential cumulative effects of previous lactations, and overall health status.

In conclusion, supplementing the OCM with physiologic amounts of micronutrients during the IVM of bovine oocytes significantly and substantially increase the yield of viable blastocysts with full ability to develop pregnancies. Additionally, supplementing the IVC phase also showed the potential to increase the yield, although the effect size seemed to be lower. Finally, supplementing both phases had a slight detrimental effect likely due to excess of supplementation. OCM supplementation candidates as a tool to improve the outcomes from assisted reproduction both in animal breeding and in the clinical setting and warrants further investigations.

Materials and methods

Ethics

All animal care protocols and all the experimental protocols used in this study were handled according to the guidelines and regulations provided by the Institutional Review Board and Institutional Ethical Committee of the Royan Institute. Also, the manuscript follows the recommendations in the ARRIVE guidelines. In addition, we clarify that no experiments on humans and/or the use of human tissue samples involved in this study.

Media and reagents

All media and chemicals were prepared from Gibco (Grand Island, NY) and Sigma Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO), respectively.

Experimental design

This study comprised two experiments. In the first experiment, oocytes were recovered from slaughterhouse ovaries and allocated into four experimental groups based on the supplementation of in vitro maturation (IVM) and/or in vitro culture (IVC) media. The second experiment involved oocytes collected via ovum pick-up after FSH stimulation, focusing exclusively on the most successful group from the first experiment, namely Sup-IVM/IVC, along with a control group. The embryos resulting from this experiment were subsequently transferred to recipients to evaluate their post-implantation developmental competence.

Design of Experiment 1

In the first experiment (Fig. 2A), bovine cumulus oocyte complexes (COCs) were aspirated from slaughterhouse ovaries from Holstein cows and addressed to IVM to be followed by IVC. The collected oocytes were randomly allocated to 4 groups corresponding to different interventions: (1) IVM/IVC, that is in vitro matured and then cultured in the standard medium without supplementation; (2) Sup-IVM/IVC, that is supplemented during IVM but not during IVC; (3) IVM/Sup-IVC, that is, supplemented only during IVC, and; (4) Sup-IVM/Sup-IVC, that is supplemented both during IVM and IVC. The OCM substrates and cofactors were supplemented as follows: Betaine (213.4 µM;23), Cystine (58.26 µM;24), Zinc bisglycinate (10 µM), Nicotinamide/B3 (16.37 µM;25), Pyridoxine/B6 (10 µM), Riboflavin/B2 (26.6 µM), 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5mTHF,1µM) and Methylcobalamin/B12 (1 µM). The cleavage and blastocyst rates were assessed, respectively, 3 and 8 days post fertilization.

In vitro oocyte maturation

COCs were aspirated from 2 to 8 mm follicles of slaughterhouse ovaries through an 18-gauge needle attached to a vacuum pump (80 mm Hg pressure). The aspiration medium consisted of HEPES-buffered TCM-199 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and heparin (10 IU/mL). COCs with intact zona pellucida and cytoplasmic membrane, homogenous cytoplasm and at least 3 layers of compact cumulus cells were selected and transferred to maturation medium.

Selected COCs were incubated for 24 h in a maturation medium consisting of TCM supplemented with 10% FBS, 1 µg/mL estradiol-17β, 2.5 mM sodium pyruvate, 10 µg/mL follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), 10 µg/mL luteinizing hormone (LH), 0.1 mM cysteamine, 10 ng/mL epidermal growth factor and 10 µg/mL insulin-like growth factor (IGF, R&D, USA) at 38.5˚C, 6% CO2, and maximum humidity.

In vitro fertilization (IVF) and in vitro culture (IVC)

In vitro fertilization was carried out as previously described26. Briefly, after thawing the frozen sperm, motile sperms were selected using swim down method with PureSperm gradient. Then matured COCs were co-incubated with 106/mL sperms in 50 µL fertilization medium for 18–20 h at humidified atmosphere, 5% CO2 and 38.5 °C.

Approximately 20 h after fertilization, presumptive zygotes were mechanically denuded from cumulus cells using a pulled pasture pipette. Modified synthetic oviduct fluid (mSOF;27,28), i.e. SOF supplemented with myo-inositol (3mM) and ITS (insulin 5 µg/mL, transferrin 5 µg/mL and selenium 5ng/mL) was used for embryo culture. In the first 3 days, the putative zygotes were cultured in mSOF without glucose and serum (mSOF−) at 38.5 °C, 5% O2, 6% CO2 and in humidified air under mineral oil. On Day 3 post culture, embryos were transferred to SOF medium supplemented with 5% serum and 1.5 mM glucose (mSOF+). The cleavage and blastocyst rates were assessed on days 3 and 8 after fertilization, respectively.

Experiment 2

Design of Experiment 2

In the second experiment (Fig. 2B), GV oocytes recovered via ovum pick up from Holstein heifers were randomly allocated to IVM with or without the same OCM supplementation, which was followed by IVF and IVC in conventional medium up to day 7. The best quality blastocysts from both groups were then used for a single embryo transfer in recipient cattle. The ongoing pregnancy rate was assessed on days 35, 90 and 180 of gestation and the final number of live and dead calves were recorded.

Animals, ovarian stimulation and blastocyst production

For the second experiment, Holstein heifers (n = 32), with an average age of 11.2 months, were used as oocyte donors. Each heifer underwent only one round of ovarian stimulation. Seven days after estrus, the dominant follicle was ablated in order to synchronize the emergence of a new follicular wave. Forty-eight hours after follicle ablation, the ovarian stimulation program was started, consisting of six FSH injections (50, 50, 30, 30, 20 and 20 mg; Folltropin-V®; Vetoquinol, France) at 12 h intervals. OPU was performed 48 h after the final injection of FSH using ultrasound scanner equipped with 7.5 MHz vaginal sector transducer equipped with needle guide (Exago®; ECM International Inc, France). Follicles, larger than 5 mm, were aspirated into HEPES-tissue culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and heparin (100 IU/mL). Following aspiration, the collected COCs were randomly allocated to IVM supplementation (same supplements as for Experiment 1) followed by non-supplemented IVC (Sup-IVM/ICV) or non-supplemented IVM and IVC (IVM/IVC). The procedures for IVM and IVC were similar to those described for the first experiment whereas for IVF female selected sex sorted semen was used for fertilization. The respective blastocyst rates were assessed 7 days post fertilization.

Single embryo transfer

Seven days after standing estrus, recipient cows, aged 46–50 months, body score of 3-3.5, average body weight of 700 kg and corpus luteum larger than 20 mm, received a single excellent or good quality blastocyst through non-surgical embryo transfer. This grading is used based on the recommendation of International Embryo Transfer Society (IETS) over the deprecated four grading systems29. Embryo transfer was conducted non-surgically using recto-vaginal approach into the uterine horn ipsilateral to the corpus luteum.

The ongoing pregnancy rate was assessed on days 35, 90 and 180 of gestation using ultrasonography and the final number of live and dead calves were recorded.

Statistical analysis

All assessments were performed at least three times and Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. The normal distribution of data was checked with Shapiro-Wilk test. Data from Experiment 1 were analyzed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to assess the effects of IVM and IVC supplementation on blastocyst rate. This method allows for the examination of interactions between the factors as well as their main effects. Post hoc comparisons were conducted using Tukey to determine specific group differences when significant effects were identified.

In Experiment 2, independent sample t-tests were performed to compare the effect of IVM supplementation on blastocyst rate, pregnancy rate, live births rate and birth weight. This analysis was used to evaluate whether there were significant differences between the two groups.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS, and the chart was created using GraphPad Prism software. Results were considered statistically significant at a p-value of < 0.05.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Eckersley-Maslin, M. A., Alda-Catalinas, C. & Reik, W. Dynamics of the epigenetic landscape during the maternal-to-zygotic transition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 436–450 (2018).

Greenberg, M. V. & Bourc’his, D. The diverse roles of DNA methylation in mammalian development and disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 590–607 (2019).

Pfeffer, P. L. Building principles for constructing a mammalian blastocyst embryo. Biology 7, 41 (2018).

Pongsuthirak, P., Songveeratham, S. & Vutyavanich, T. Comparison of blastocyst and sage media for in vitro maturation of human immature oocytes. Reproductive Sci. 22, 343–346 (2015).

Son, W. Y., Lee, S. Y. & Lim, J. H. Fertilization, cleavage and blastocyst development according to the maturation timing of oocytes in in vitro maturation cycles. Hum. Reprod. 20, 3204–3207 (2005).

Dattilo, M., Giuseppe, D. A., Ettore, C. & Ménézo, Y. Improvement of gamete quality by stimulating and feeding the endogenous antioxidant system: mechanisms, clinical results, insights on gene-environment interactions and the role of diet. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 33, 1633–1648 (2016).

Teng, Y. W., Mehedint, M. G., Garrow, T. A. & Zeisel, S. H. Deletion of betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase in mice perturbs choline and 1-carbon metabolism, resulting in fatty liver and hepatocellular carcinomas. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 36258–36267 (2011).

Gregory, J. F., DeRatt, B. N., Rios-Avila, L., Ralat, M. & Stacpoole, P. W. Vitamin B6 nutritional status and cellular availability of pyridoxal 5′-phosphate govern the function of the transsulfuration pathway’s canonical reactions and hydrogen sulfide production via side reactions. Biochimie 126, 21–26 (2016).

Yusuf, A. P. et al. Zinc metalloproteins in epigenetics and their crosstalk. Life 11, 186 (2021).

Clement, A. et al. Hyperhomocysteinemia in hypofertile male patients can be alleviated by supplementation with 5MTHF associated with one carbon cycle support. Front. Reprod. Health 5, 1229997 (2023).

Schiuma, N. et al. Micronutrients in support to the one carbon cycle for the modulation of blood fasting homocysteine in PCOS women. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 43, 779–786 (2020).

Golestanfar, A. et al. Metabolic enhancement of the one carbon metabolism (OCM) in bovine oocytes IVM increases the blastocyst rate: evidences for a OCM checkpoint. Sci. Rep. 12, 20629 (2022).

Menezo, Y., Elder, K., Clement, P., Clement, A. & Patrizio, P. Biochemical hazards during three phases of assisted reproductive technology: repercussions associated with epigenesis and imprinting. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 8916 (2022).

Li, L. et al. Characterization of metabolic patterns in mouse oocytes during meiotic maturation. Mol. Cell. 80, 525–540 (2020).

Messerschmidt, D. M., Knowles, B. B. & Solter, D. DNA methylation dynamics during epigenetic reprogramming in the germline and preimplantation embryos. Genes Dev. 28, 812–828 (2014).

Ivanova, E. et al. DNA methylation changes during preimplantation development reveal inter-species differences and reprogramming events at imprinted genes. Clin. Epigenetics. 12, 1–18 (2020).

Ereño-Orbea, J., Majtan, T., Oyenarte, I., Kraus, J. P. & Martínez-Cruz, L. A. Structural insight into the molecular mechanism of allosteric activation of human cystathionine β-synthase by S-adenosylmethionine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, E3845–E3852 (2014).

Xiao, W. & Loscalzo, J. Metabolic responses to reductive stress. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 32, 1330–1347 (2020).

Kucuk, T., Horozal, P. E., Karakulak, A., Timucin, E. & Dattilo, M. Follicular homocysteine as a marker of oocyte quality in PCOS and the role of micronutrients. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 40, 1933–1941 (2023).

Clare, C. E. et al. Interspecific variation in one-carbon metabolism within the ovarian follicle, oocyte, and preimplantation embryo: consequences for epigenetic programming of DNA methylation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 1838 (2021).

Zamudio, N. et al. DNA methylation restrains transposons from adopting a chromatin signature permissive for meiotic recombination. Genes Dev. 29, 1256–1270 (2015).

Nicodemo, D. et al. Frequency of aneuploidy in in vitro–matured MII oocytes and corresponding first polar bodies in two dairy cattle (Bos taurus) breeds as determined by dual-color fluorescent in situ hybridization. Theriogenology 73, 523–529 (2010).

Zhang, D. et al. Supplement of betaine into embryo culture medium can rescue injury effect of ethanol on mouse embryo development. Sci. Rep. 8, 1761 (2018).

Rushworth, G. F. & Megson, I. L. Existing and potential therapeutic uses for N-acetylcysteine: the need for conversion to intracellular glutathione for antioxidant benefits. Pharmacol. Ther. 141, 150–159 (2014).

Tsai, F. C. & Gardner, D. K. Nicotinamide, a component of complex culture media, inhibits mouse embryo development in vitro and reduces subsequent developmental potential after transfer. Fertil. Steril. 61, 376–382 (1994).

Hosseini, S. M. et al. Epigenetic modification with trichostatin A does not correct specific errors of somatic cell nuclear transfer at the transcriptomic level; highlighting the non-random nature of oocyte-mediated reprogramming errors. BMC Genom. 17, 1–21 (2016).

Hosseini, S. M., Moulavi, F. & Nasr-Esfahani, M. H. A novel method of somatic cell nuclear transfer with minimum equipment. Methods Mol. Biol. 1330, 169–188 (2015).

Wang, L. J. et al. Defined media optimization for in vitro culture of bovine somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) embryos. Theriogenology 78, 2110–2119 (2012).

Lindner, G. M. & Wright, R. W. Jr Bovine embryo morphology and evaluation. Theriogenology 20, 407–416 (1983).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Iran National Science Foundation (INSF; Project No: 97002657) and Deputy for Research, University of Tehran. The funder has no involvement in the design of the study or collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. The authors wish to express their great appreciations to the staff of Royan Institute for kind assistance to perform this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G.: Investigation, methodology and writing-original draft; A.N.N.: funding acquisition, supervision and writing-original draft; F.J.: formal analysis, investigation, supervision, validation and writing-original draft; N.S.B.: methodology S.R.V.: methodology; Y.M.: conceptualization and supervision; M.D.: conceptualization, methodology, supervision and writing- review editing; M.H.N.E.: conceptualization, methodology, supervision and writing-review editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Conflict of interest

MD reports personal fees from Parthenogen SAGL, outside the submitted work; In addition, MD is inventor of the pending patents “Dietary supplementation to achieve oxy-redox homeostasis and epigenetic stability” and “Combination of micronutrients to stimulate the endogenous production of hydrogen sulfide (H2S)”. All other authors have no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Golestanfar, A., Naslaji, A.N., Jafarpour, F. et al. One carbon metabolism supplementation in maturation medium but not embryo culture medium improves the yield of blastocysts from bovine oocytes. Sci Rep 15, 2749 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85410-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85410-7