Abstract

Trophic interactions regulate populations, but anthropogenic processes influence primary productivity and consumption by both herbivore and carnivore species. Trophic ecology studies often focus on natural systems such as protected areas, even though livestock globally comprise the majority of terrestrial vertebrate biomass. Here we explore spatial and temporal patterns in the distribution of biomass between plants, and large herbivores and carnivores (> 10 kg) in Norwegian rangelands, including both wildlife and livestock. We find high spatial variation in the relationship between plant and herbivore biomass, with both positive and negative divergence in observed biomass from expectations based on primary productivity. Meanwhile, despite recent partial recoveries in carnivore densities across Norway, carnivore biomass is still lower than expected based on herbivore biomass, even if livestock are excluded from the estimation. Our study highlights how temporal trends in both herbivores and carnivores reflect policy development. The role of livestock husbandry and wildlife management is thus key in determining realised biomass distributions in anthropogenically influenced ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Energy flows through ecological communities from primary producers to top-level consumers. This leads to pyramidal patterns of biomass across trophic levels with remarkably consistent biomass scaling between prey and predators1 and between herbivores and vegetation2,3. At the same time, consumers can influence the biomass of lower trophic levels through top-down cascades4,5. Bottom-up energetic flows and top-down trophic cascades may vary in importance between ecosystems and over time and space6,7. Trophic interactions determine the structure of communities, ecosystems and even biomes, and play a huge role in ecosystem functioning with impacts on global climate8,9.

Anthropogenic activity alters trophic networks through a range of impacts, including climate change, direct exploitation, agriculture, forestry, land-use change, pollution and the spread of non-native species10. Global environmental change may affect bottom-up energetics. For example, global warming or nitrogen deposition may increase primary productivity in temperature-limited environments11,12, . Changes in productivity can also cause shifts in vegetation composition, such as shrub expansion in the tundra13, which can alter consumer dynamics14. Land-use changes and agricultural policies influence the prevalence of natural ecosystem, wildlife and livestock. Anthropogenic changes can also affect cascading properties of trophic interactions. Wildlife management influences the degree of human harvest, or supplementary feeding, of game species. This can be through the selective removal of top predators from ecosystems, which can lead to increasing densities of herbivores8,15 and meso-predator release16.

Global biomass distributions have been changed to a state where the vast majority of non-human mammal biomass today is comprised of a few species of livestock17,18. Recently, in some regions, notably Europe, a combination of social, economic, legal and political drivers have driven rural land abandonment, a decrease in livestock densities, and increases in wild herbivores19,20 and carnivores21.

Empirical studies investigating biomass distributions within ecological communities have generally focused on systems that retain natural communities, such as national parks and restored or rewilded systems1,2. However, in many (if not most) parts of the world, free-ranging livestock and wild species overlap in distribution22. Wild herbivores and livestock are under different management regimes within the same areas but have a common impact on primary production. Thus, it is important to understand how wildlife and livestock fit into trophic biomass distributions for a more integrated nature and agricultural management.

In this study we investigate how biomass distribution varies across time and space between trophic levels. We focus on the outfields, or rangelands of Norway (termed utmark in Norway); the unimproved and unenclosed land mostly comprising alpine and arctic tundra and forests. The study concentrates on large vertebrate consumers (> 10 kg), including livestock and wildlife, as well as vegetation. Norway is a highly suitable study system having good historical data on wildlife and livestock populations and a long history of wildlife and livestock dynamics across ecosystems20,23. In Norwegian forests, herbivores have undergone a shift from livestock dominance in the 1950s to parts of the country now having predominantly wild herbivore populations, while alpine regions remain largely dominated by livestock20. Large carnivore populations have shown some recent recovery in Europe24,25,26 In Norway, large carnivore populations (wolf Canis lupus, brown bear Ursus arctous, wolverine Gulo gulo and lynx Lynx lynx) have staged a partial recovery since the cessation of state bounties in the 1970’s and 1980’s, but densities remain very low due to the widespread use of lethal means to limit their populations to politically determined numbers and distributions to specific zones25,27,28, later referred to as carnivore management zones.

This analysis has the following objectives: First, to quantify the biomass of large herbivores and carnivores in Norway as far back in time as possible, second, to compare observed biomass of consumer guilds with the biomass at lower trophic levels, based on published trophic biomass scaling relationships1,2 and third to answer the following questions: 1. Are herbivore and carnivore biomass as expected given net primary productivity (NPP), and if not, where do deviations exist? 2. Is realized carnivore biomass in line with expectations based on wild herbivore populations (i.e. carnivore populations are at a level appropriate for wild prey)? We predict (1) that herbivore biomass is on average in line with expectations from NPP, albeit with regions with higher and lower biomass than expected (i.e. over- or under-grazing), and (2) that carnivore biomass is lower than expectations from realized (and expected) herbivore biomass, but with lower deviation in carnivore management zones.

Results

Biomass within trophic levels

Net primary productivity across Norway varied from a mean of 272 000 kg C km− 2 in year 2001, to 357 000 kg C km− 2 in year 2018 (Fig. 1a, Figure S1). NPP was highest in the lowlands in the southeast of the country and along the coast, peaking at over 1 000 000 kg C km− 2, and lowest in mountain regions and in the north (Fig. 2a; Figure S2).

Biomass trends in trophic levels across Norway. (a) Shows the average biomass density per trophic levels vegetation (as NPP, 2000–2021, see also Figure S1), large herbivores (> 10 kg 1907–2015) and large carnivores (> 10 kg, 1846–2015); the contributions of livestock and wild herbivores to total herbivore biomass are indicated. (b) and (c) show the species contributions to biomass of livestock and large wild herbivores. Part (d) shows the contribution of carnivore species to total carnivore biomass. Note the different extents of the data series on the x axis, and that the y axis in part (a) is log10 transformed, while the others are linear.

Herbivore biomass at the national scale was at its highest in 1939 at 488 kg km− 2 and was lowest in 1959 at 250 kg km− 2 (Fig. 1a). There was a high turnover of species within the herbivore guild. In 1939 livestock (mostly cattle) comprised 97% of herbivore biomass across Norway while in 2009 livestock comprised 53% of the total herbivore biomass (mostly sheep Ovis aries, Fig. 1a and b). This turnover mainly comprised a replacement of cattle with the wild cervid species moose (Alces alces), red deer (Cervus elaphus) and roe deer (Capreolus capreolus; Fig. 1b and c). In 2015, herbivore biomass was highest in municipalities along the west coast of Norway and in northern Oppland county (Fig. 2b, see Figure S3 for map of counties). Herbivore biomass density maps of all species across the study period are shown in Figure S4.

Carnivore biomass was highest at the start of the period of data availability, in 1847 at 1.32 kg km− 2 (Fig. 1d). The minimum carnivore biomass of 0.009 kg km− 2 was reached in 1934 before rising again to around 0.12 kg km− 2 in recent years. In 2015 carnivore densities were highest in eastern and northern counties of Norway (Fig. 2c). Carnivore biomass density maps of all species across Norway between 1846 and 2015 are shown in Figure S5.

Biomass between trophic levels

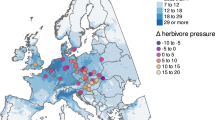

In 2015, the biomass density of all herbivores was higher than expected based on NPP in most of Western and Mid-Norway as well as in Northern Norway (Fig. 3a). At the same time, herbivore biomass density was lower than expected in South Norway, the coast of Nordland and the mountains of northern Trøndelag. Concurrently, carnivore densities were lower than expected based on observed herbivore densities across the whole of the country, except for Hedmark and southern Trøndelag (Fig. 3b).

Deviation between observed and expected biomass of herbivores (left, ( a,c,e)) and carnivores (right, (b,d,f)) across all species and ecosystems (top) and specific to forest species and ecosystem (middle) and alpine species and ecosystems (bottom). Data are from the year 2015. Maps created in R58, using the package sf59.

Within forest ecosystems (and forest consumer species) herbivore biomass was generally in line with or lower than expected across much of the country in 2015. The southern counties of Telemark and Aust- and Vest-Agder had the largest negative deviation from expected herbivore biomass, along with Finnmark in north Norway. In contrast, there was higher forest herbivore biomass than expected based on NPP in Akershus, Østfold and parts of Oppland (Fig. 3c). Within alpine ecosystems, there were higher biomass densities than expected in the mountains in the south, as well as in Finnmark. In Trøndelag and Nordland, alpine herbivore biomass densities were generally lower than expected based on NPP (Fig. 3e). In both forest (Fig. 3d) and alpine (Fig. 3f) ecosystems, carnivore biomass densities in relation to herbivore biomass densities were similar to the overall pattern, with lower carnivore densities than expected in most of the country, with the exception of Hedmark which had forest carnivores in line with expectations from forest herbivores (Fig. 3d) and Finnmark, where forest carnivores were higher than expected given the densities of forest herbivores (Fig. 3d).

Carnivore biomass in 2015 remained below expectations if expected carnivore biomass is estimated based on only wild herbivore biomass (i.e. excluding livestock) across most of the country (Fig. 4a). There are exceptions in Hedmark and southern Trøndelag where carnivore biomass is in line with wild herbivore biomass and Finnmark where carnivore biomass is higher than expected (Fig. 4a). Carnivore biomass is also lower than expected based on expected-herbivore-biomass (Fig. 4b), again with the exception in Hedmark and southern Trøndelag where carnivore biomass is in line with expectations.

Data underlying the three trophic levels was available for different time periods, limiting analysis of temporal trends in biomass deviations from expectations. However, prior to the 1950s, some counties in the south and west of Norway, had far higher herbivore biomass than expectations based on NPP estimated during 2000–2015 (Fig. 5a). In contrast, in northern counties such as Troms and Finnmark, herbivore biomass (mostly semi-domestic reindeer; Figure S4) remained in line with expectations based on NPP (estimated only between 2000 and 2015). Carnivore biomass was lower than expected based on herbivore biomass for all counties for the whole period in which herbivore data was available (Fig. 5b). However, prior to the 1920s, carnivore biomass was in line with what would be expected for herbivore biomass in the period 1929–2015, and in some counties, including Telemark and Aust-Agder, higher than expectations.

Temporal trends in herbivore (top, (a)) and carnivore (bottom, (b)) biomass across Norway’s 18 counties (excluding Oslo). Expected biomasses are shown as dashed lines. For expected herbivore biomass this is based on the average NPP across 2000–2021. For carnivores, the expected biomass is calculated based on herbivore biomass (1907–2015).

Discussion

In this study we present biomass estimates of carnivores and herbivores across space and time. We show that the biomass of herbivores and carnivores fluctuated over time. Herbivore biomass varied greatly in relation to expectations based on net primary productivity, while throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, carnivore biomass was lower than expected based on both observed and expected herbivore biomass. This study provides an integrated assessment of trophic structure at a national spatial scale and centurial temporal scale. Trophic structure is an important component of ecosystem function. Our study builds on previous studies1,2 by highlighting the need to account for both livestock and wildlife, since in our study region, livestock accounted for over half of the total herbivore biomass during the 20th century. The co-occurrence of livestock and wildlife is not specific to Norway, but is common throughout the world, and not surprising given the predominance of livestock in animal biomass17. In many rangelands livestock comprise the majority of herbivore biomass, for example 86% across Iceland29. However, many ecological studies still attempt to focus solely on “natural” ecosystems and dynamics30 ignoring the huge influence of livestock on ecological processes.

Herbivores shifted from livestock dominance in Norway during the early to mid-20th century, to approximately equal densities of wildlife and livestock at the end of the 20th century and into the 21st century; this expands the timeframe of the dynamics earlier reported20,31. Our analyses suggest that parts of the mountain regions have a greater herbivore biomass than expected given the vegetation productivity, filling one of many perspectives on the concept of overgrazing32. The high herbivore densities seen in the Norwegian mountains have been maintained for many decades in these regions (Fig. 5) with impacts on ecosystem functioning33. The maintenance of high herbivore densities in Norwegian mountains today likely has strong social and economic basis, calling for integrating historical context with ecology in understanding interactions between ecosystems and consumers33,34.

The distribution of biomass between trophic levels has been used as an indicator of ecosystem condition35 and both herbivores and carnivores are important contributors to ecosystem services36. Our results show that carnivore densities are lower than expectations based on herbivore biomass across Norway today, and have been since at least the 1920s, except for the eastern and northern parts of the country. Carnivores declined in the late 19th century due to intense state-sponsored persecution, were at a nadir throughout most of the mid-20th century, when the wolf was functionally extinct, bears were reduced to non-breeding occurrences and both wolverines and lynx were reduced to small remnant populations. Decades of changes to legislation has led to the return of breeding populations of all species during the late 20th century, largely within limited carnivore management zones26. Wolf and bear numbers remain low and are limited to counties with carnivore management zones, mostly along Norway’s eastern border. Lynx and wolverines are more widespread. However, lethal control and hunter harvest are used to maintain numbers and distributions within strict politically determined limits and zones, to reduce depredation of livestock. Carnivore management is a highly emotive and controversial issue in Norway37. Livestock losses to predation are substantial38,39,40 and livestock production practices have to adapt to carnivore presence41. The lower than expected carnivore biomass, even when considering only wild herbivores, suggests that Norwegian ecosystems have a reduced integrity and resilience compared to a natural state35. Impacts of deviations in trophic functioning on ecosystems can cascade across guilds of carnivores, herbivores and vegetation, with impacts also on biodiversity, soils, disease spread and on biogeochemical processes36.

In this study, analyses were performed across all ecosystems and species, but separately for the main ecosystems: forest and alpine. The trophic levels include species that predominantly use different ecosystems for example moose (forest) and reindeer (alpine). When analyses are separated by ecosystem type (across all three trophic levels), we arrive at the conclusion that forest herbivore biomass is lower than expected in Finnmark. Moose, red deer and roe deer have historically been absent from the far north of Norway, but now are partly colonizing the region. However, semi-domestic reindeer use forest habitats in Norway, especially in winter42, thus the herbivore trophic level is likely underestimated for the forest ecosystem in Finnmark. This exemplifies the habitat flexibility of some species implying that the habitat-specific results should be interpreted with caution.

The scale at which biomass of each trophic level was assessed varied, from 0.25 km2 for primary productivity, through municipalities for herbivores (median rangeland area of 418 km2) to counties (median rangeland area of 14 000 km2) for carnivores. This assumes that consumer habitat use is constant across the area assessed. This is unlikely to be the case, as both herbivores and carnivores are selective in their habitat use43,44,45. In addition, there are likely unaccounted errors in backcasting carnivore populations from hunting statistics, such as vehicle killings and illegal hunting. Our modelled estimates were reasonably similar to monitoring-based estimates of carnivore populations for bear and wolf. The models underestimated lynx and wolverine populations during a period of rapid increase (Figure S6) and may also overestimate populations in periods of population decrease.

We used published global biomass scaling models to estimated expected biomass at herbivore and carnivore trophic levels. The herbivore model used had a low coefficient of determination (0.04; Ref.2) with few sites in boreal or tundra ecosystems, which is a potential source of error. We also applied models developed predominantly in natural ecosystems (mostly national parks and protected areas), to a system with co-occurring livestock and wildlife. While we did standardise biomass estimates by the fraction of the year that livestock are in the rangelands, a caveat remains; that livestock populations in Norwegian rangelands, as in other northern systems, are subsidised through the winter season by supplementary feeding46. In addition, wild herbivore species can be subsidised through foraging on fertilized agricultural crops47. The absence of many of the livestock species (excepting semi-domestic reindeer) from ecosystems during the winter also has implications for the relationship between carnivore biomass and herbivore biomass. However, carnivore biomass was below expectations based on only wild herbivore biomass throughout most of the country (Fig. 4a). Similarly, bears hibernate during winter and have an omnivorous diet. Since bears contribute a high proportion of carnivore biomass, this increases the conservatism of our finding of lower carnivore biomass than expected from herbivore biomass. Both herbivore and carnivore guilds analysed here were limited to large species with an average biomass of over 10 kg. Herbivorous rodents, lagomorphs and avian and invertebrate herbivores fell outside this definition, yet all can influence vegetation dynamics in northern ecosystems. Thus, our analyses do not capture total vegetation-herbivore dynamics, only the species managed as game and livestock. Among the carnivores, golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) and red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) may rarely kill young of the smaller herbivore species considered, yet we assume that this seasonally restricted predation is limited enough that our study retains relevance for dynamics of managed species.

Livestock management is driven by economic and regulatory mechanisms in the region33,42. Populations of wildlife are also heavily influenced by human management, with sex and age specific hunting quotas used as management tools to influence population growth rates48,49. Thus, while our study focusses on biomass ratios between plants, herbivores and carnivores, all of these trophic levels are under strong human influence. Norway has been identified as having the greatest potential for rewilding in Europe50, however, given that herbivore biomass is already high relative to productivity, and carnivore management is heavily dictated by livestock concerns, the likelihood of enacting such a shift is very low.

Our approach identifies regions of Norway which have relatively higher or lower consumption across trophic levels, with relevance for livestock, wildlife and ecosystem management. The scarcity of carnivores in Norwegian ecosystems in relation to herbivore biomass likely has implications for ecosystem structure and functioning, biodiversity and ecosystem services8. The impact of reintroduced carnivores on carbon storage in North America has been estimated to be negative in grasslands but positive in forest ecosystems51. In Norway, high densities of forest herbivores (Fig. 2), reduce aboveground carbon storage by supressing tree biomass during secondary succession; this has potential feedbacks to climate52 as well as potential interactions with forest management53. Higher carnivore densities would be expected to limit forest herbivore populations leading to increased tree growth and carbon storage, but due to increased albedo under browsed conditions, especially during the snow-covered winter, the net climate effect of increasing carnivore densities in forests may be neutral54.

In conclusion, our study shows that across large parts of Norwegian rangelands, herbivore biomass is high in relation to primary productivity and large carnivore biomass is low in relation to primary productivity. However, there is a high degree of spatial variation in these patterns. In ecosystems with co-occurring wildlife and livestock, dynamics are influenced both by natural trophic dynamics, acting in concert with management of ecosystems and single species. This calls for integrated management involving forestry, agricultural and wildlife sector stakeholders.

Methods

Biomass of trophic levels

Plant, herbivore and carnivore biomass were each quantified across Norwegian rangelands (uncultivated land mainly comprising forests and tundra above the latitudinal and elevational treelines). Herbivore and carnivore biomasses were estimated on the basis of hunting and livestock statistics and records. For herbivores these data were available at the municipality level and for carnivores at the county level. Administrative boundary changes have occurred (mostly merging of units). For both municipality and county data, boundaries in place prior to 2017 were used and are discussed in the text (Figure S3).

Plant biomass was quantified as net annual primary productivity (NPP). While productivity is a rate (biomass increment over time), this was deemed most appropriate since annual productivity is assumed to be more available to herbivores than standing plant biomass, of which a large pool is held in woody biomass. Furthermore, NPP has previously been used to predict global patterns in herbivore biomass2,3 and is thus required to estimate expected herbivore biomass. Annual NPP was downloaded from MODIS at 500 m spatial resolution, spanning the years 2000–202155. The global dataset was cropped and masked to the country of Norway, and NPP converted to kg C km− 2 yr− 1.

Herbivore biomass was estimated for the period from 1907 to 2015 for species over 10 kg. The approach extended the datasets presented by20,31, which were previously limited to 1949–2015. Agricultural statistics reports and reindeer herding reports were used to quantify livestock population biomass, while wild herbivore population biomass was quantified on the basis of population models parameterised by hunter-observations and hunting statistics. In contrast to the aforementioned studies, herbivore biomass was estimated as raw biomass densities rather than metabolic biomass densities. Biomass densities were quantified for livestock species (cattle Bos taurus, sheep Ovis aries, goats Capra hircus, horses Equus ferus caballus and semi-domestic reindeer Rangifer tarandus), and wildlife species; (moose Alces alces, roe deer Capreolus capreolus, red deer Cervus elaphus and wild reindeer Rangifer tarandus). Note that reindeer in Norway are comprised of both wild populations and semi-domestic populations (both are Rangifer tarandus ssp. tarandus) and due to their separate status and management are treated separately here. A small population (around 200 individuals) of muskox (Ovibos moschatus) exists in the Dovrefjell mountains in Central Norway which management authorities consider a non-native species20, and was subsequently omitted from this study. Prior to 2015, individual wild boar (Sus scrofa) were only occasionally observed in south-eastern and central Norway and due to extremely low and sporadic numbers at that time, are also omitted from this study.

Herbivore biomass densities were estimated for Norwegian municipalities at a decadal resolution (Table S1), using the pre-2017 administrative boundaries, and summing data where required to reflected merged municipalities. Livestock densities were standardised by the fraction of the year that each species spends in the rangelands (i.e. the population biomass for a species ranging for 3 months of the year would be standardised to 25%). Austrheim et al.31 provide further methodological details on the estimation of herbivore biomass densities.

Carnivore biomass was estimated using a backcasting population dynamic model based on the approach used for Finnish carnivores by Mykrä and Pohja-Mykrä56. All species of large carnivores (over 10 kg) in Norway were included: the grey wolf Canis lupus, wolverine Gulo gulo, brown bear Ursus arctos and Eurasian lynx Lynx lynx. Carnivore biomass estimates were based on hunting statistics at the county level (using county boundaries in existence prior to 2018) and covered the period 1847–2016. While this method using hunting statistics is likely to be error prone and makes the assumption that hunted individuals are accurately reported (the early bounty system and modern-day wildlife management practices facilitated fairly accurate and complete recording), it remains the best and only approach to quantify past population dynamics at this resolution56. Appendix A gives full methodological details regarding modelling carnivore biomass densities. Backcasted carnivore populations are shown in Figure S6. Carnivore data was estimated at an annual resolution, but is presented at a decadal resolution, matching that of herbivores (Table S1).

Expected consumer biomass

The expected herbivore biomass (HBexp) based on plant productivity was calculated using the global relationship published by Fløjgaard et al.2. This global relationship (Expected herbivore biomass = 0.643 × NPP0.47) was not as strong as relationships derived from African ecosystems2, however it was deemed most appropriate due to the present day, and historical, lack of mega-herbivores in Norway. The global relationship was selected rather than the European and North American relationships as the range of productivity values covered by the global model had a closer match with NPP in Norway (the European relationship had no datapoints, and the North American relationship had only five data points below the mean NPP of Norway).

[Eq1] from Fløjgaard et al.2, where HBexpi is expected herbivore biomass in year i, and NPP is the NPP in year i.

Expected carnivore biomass (CBexp) based on herbivore biomass was based on the scaling relationships published by Hatton et al.1. We used the relationship Carnivore biomass expected = 0.094 × Herbivore biomass0.73 from African communities noting that the scaling exponent was near identical in wolf-prey systems [0.72, Ref. 1].

[Eq2] from Hatton et al.1, where CBexpi is the expected carnivore biomass in year i and HB is the herbivore biomass in year i.

Deviations between observed herbivore biomass and expected herbivore biomass were calculated for 2000 (using observed herbivore biomass from 1999 with expected herbivore biomass in 2000), 2009 and 2015. Deviations between observed carnivore biomass and expected carnivore biomass were calculated for the common period of 1907–2015. Older carnivore biomass data are also presented here to visualize longer-term dynamics.

Biomass deviations were calculated across all species and limited to forest and alpine ecosystems. The ecosystem-specific estimates were based on NPP cells assigned to each major land-cover class using the AR50 land-cover map57 and the classes skog (forest) and snaumark (open vegetation). The open category includes land above the elevational and latitudinal treeline as well as less extensive lowland heaths. Consumer species were assigned according to their predominant habitat as follows: Moose, red deer, roe deer and cattle were classed as forest herbivores and wolf, bear and lynx as forest carnivores. Wild reindeer, semi-domestic reindeer, sheep and goats were classed as alpine herbivores and the wolverine as an alpine carnivore (horses were not included in either ecosystem). We note that most of these species use multiple habitats, however, we do not have the data to assign species’ proportional habitat use accounting for spatial and temporal variation. Finally, to address the question of whether carnivore biomass is in line with wildlife biomass, we estimated expected carnivore biomass based on only observed wild herbivore biomass (Eq. 3), and to address the question of whether carnivore biomass is in line with NPP, we estimated expected carnivore biomass as a function of expected herbivore biomass (Eq. 4).

[Eq3] from Hatton et al.1, where CBexpi is the expected carnivore biomass in year i and WHBi is the wild herbivore biomass in year i

[Eq4] from Hatton et al.1, where CBexpi is the expected carnivore biomass in year i and HBexpi is the expected herbivore biomass in year i (from Eq. 1).

All data processing and analyses were carried out in the R environment 4.3.258, using the packages sf59 and terra60 for spatial analysis and visualization.

Data availability

No primary data was generated in this study. All sources of data are cited in the manuscript.

References

Hatton, I. A. et al. The predator-prey power law: Biomass scaling across terrestrial and aquatic biomes. Science 349 (6252), aac6284 (2015).

Fløjgaard, C. et al. Exploring a natural baseline for large-herbivore biomass in ecological restoration. J. Appl. Ecol. 59 (1), 18–24 (2022).

Harfoot, M. B. et al. Emergent global patterns of ecosystem structure and function from a mechanistic general ecosystem model. PLoS Biol. 12 (4), e1001841 (2014).

Shurin, J. B. et al. A cross-ecosystem comparison of the strength of trophic cascades. Ecol. Lett. 5 (6), 785–791 (2002).

Knight, T. M. et al. Trophic cascades across ecosystems. Nature 437 (7060), 880–883 (2005).

Barbier, M. & Loreau, M. Pyramids and cascades: a synthesis of food chain functioning and stability. Ecol. Lett. 22 (2), 405–419 (2019).

Wilkinson, D. M. & Sherratt, T. N. Why is the world green? The interactions of top–down and bottom–up processes in terrestrial vegetation ecology. Plant Ecol. Divers. 9 (2), 127–140 (2016).

Estes, J. A. et al. Trophic downgrading of planet earth. Science 333(6040): 301–306 (2011).

Pringle, R. M. et al. Herbivore-initiated interaction cascades and their modulation by productivity in an African savanna. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 104 (1), 193–197 (2007).

Jaureguiberry, P. et al. The direct drivers of recent global anthropogenic biodiversity loss. Sci. Adv. 8 (45), eabm9982 (2022).

Beck, P. S. & Goetz, S. J. Satellite observations of high northern latitude vegetation productivity changes between 1982 and 2008: ecological variability and regional differences. Environ. Res. Lett. 6 (4), 045501 (2011).

Zhang, L. et al. Disentangling the effects of climate variability and herbivory on spatial and temporal changes in northern vegetation greening. Ecol. Indic. 159, 111700 (2024).

Myers-Smith, I. H. et al. Climate sensitivity of shrub growth across the tundra biome. Nat. Clim. Change. 5, 887–891 (2015).

Wheeler, H. C., Høye, T. T. & Svenning, J. C. Wildlife species benefitting from a greener Arctic are most sensitive to shrub cover at leading range edges. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 212–223 (2018).

Enquist, B. J. et al. The megabiota are disproportionately important for biosphere functioning. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 1–11 (2020).

Prugh, L. R. et al. The rise of the mesopredator. Bioscience 59 (9), 779–791 (2009).

Bar-On, Y. M., Phillips, R. & Milo, R. The biomass distribution on Earth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115 (25), 6506–6511 (2018).

Greenspoon, L. et al. The global biomass of wild mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120 (10), e2204892120 (2023).

Apollonio, M. et al. Challenges and science-based implications for modern management and conservation of European ungulate populations. Mammal Res. 62 (3), 209–217 (2017).

Speed, J. D. M. et al. Long-term changes in northern large-herbivore communities reveal differential rewilding rates in space and time. PLoS One 14 (5), e0217166 (2019).

Cimatti, M. et al. Large Carnivore expansion in Europe is associated with human population density and land cover changes. Divers. Distrib. 27 (4), 602–617 (2021).

du Toit, J. T., Cross, P. C. & Valeix, M. Managing the livestock–wildlife interface on rangelands. Rangeland systems: processes, management and challenges, 395–425 (2017).

Rosvold, J. et al. Cervids in a dynamic northern landscape: holocene changes in the relative abundance of moose and red deer at the limits of their distributions. Holocene 23 (8), 1143–1150 (2013).

Chapron, G. et al. Recovery of large carnivores in Europe’s modern human-dominated landscapes. Science 346 (6216), 1517–1519 (2014).

Linnell, J. D. et al. Sustainably harvesting a large Carnivore? Development of Eurasian lynx populations in Norway during 160 years of shifting policy. Environ. Manag. 45, 1142–1154 (2010).

Strand, G. H. et al. Carnivore management zones and their impact on sheep farming in Norway. Environ. Manag. 64, 537–552 (2019).

Swenson, J. E. et al. The near extinction and recovery of brown bears in Scandinavia in relation to the bear management policies of Norway and Sweden. Wildl. Biol. 1 (1), 11–25 (1995).

Wabakken, P. et al. The recovery, distribution, and population dynamics of wolves on the scandinavian peninsula, 1978–1998. Can. J. Zool. 79 (4), 710–725 (2001).

Defourneaux, M. et al. Long-term changes in herbivore community and vegetation impact of wild and domestic herbivores across Iceland (Ambio, 2024).

Keesing, F. et al. Consequences of integrating livestock and wildlife in an African savanna. Nat. Sustain. 1 (10), 566–573 (2018).

Austrheim, G., Solberg, E. J. & Mysterud, A. Spatio-temporal distribution of large herbivores in Norway from 1949 to 1999: has decreased grazing by domestic herbivores been countered by increased browsing by cervids? Wildl. Biol. 17, 1–13 (2011).

Mysterud, A. The concept of overgrazing and its role in management of large herbivores. Wildl. Biol. 12 (2), 129–141 (2006).

Ross, L. C. et al. Sheep grazing in the North Atlantic region: a long-term perspective on environmental sustainability. Ambio 45 (5), 551–566 (2016).

Stark, S. et al. The ecosystem effects of reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) in northern Fennoscandia: past, present and future. Perspect. Plant. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 58, 125716 (2023).

Jepsen, J. U. et al. Panel-based assessment of ecosystem condition as a platform for adaptive and knowledge driven management. Environ. Manag., 1–17 (2024).

Ripple, W. J. et al. Status and ecological effects of the world’s largest carnivores. Science 343 (6167), 1241484 (2014).

Krange, O., Von Essen, E. & Skogen, K. Law abiding citizens: on popular support for the illegal killing of wolves. Nat. Cult. 17 (2), 191–214 (2022).

Swenson, J. & Andrén, H. A tale of two countries: large carnivore depredation and compensation schemes in Sweden and Norway. In People and wildlife Conflict or coexistence (R. Woodroffe, S. Thirgood, and A. Rabinowitz Eds.), p. 323 (Conservation Biology Series, 2005).

Mabille, G. et al. Sheep farming and large carnivores: what are the factors influencing claimed losses? Ecosphere 6 (5), 1–17 (2015).

Tveraa, T. et al. The role of predation and food limitation on claims for compensation, reindeer demography and population dynamics. J. Appl. Ecol. 51 (5), 1264–1272 (2014).

Hansen, I. et al. Impacts of Norwegian large Carnivore management strategy on national grazing sector. J. Mt. Sci. 16 (11), 2470–2483 (2019).

Holand, Ø. et al. Reindeer pastoralism in Fennoscandia. In Reindeer Husbandry and Global Environmental Change, pp. 7–47 (Routledge, 2022).

May, R. et al. Habitat differentiation within the large-Carnivore community of Norway’s multiple‐use landscapes. J. Appl. Ecol. 45 (5), 1382–1391 (2008).

Bjørneraas, K. et al. Habitat quality influences population distribution, individual space use and functional responses in habitat selection by a large herbivore. Oecologia 168, 231–243 (2012).

Mobæk, R. et al. Density dependent and temporal variability in habitat selection by a large herbivore; an experimental approach. Oikos 118 (2), 209–218 (2009).

Ross, L. C. et al. Sheep grazing in the North Atlantic region: a long-term perspective on environmental sustainability. Ambio, 1–16 (2016).

Bjørneraas, K. et al. Moose Alces alces habitat use at multiple temporal scales in a human-altered landscape. Wildl. Biol. 17 (1), 44–54 (2011).

Milner, J. M., Nilsen, E. B. & Andreassen, H. P. Demographic side effects of selective hunting in ungulates and carnivores. Conserv. Biol. 21 (1), 36–47 (2007).

Lavsund, S., Nygrén, T. & Solberg, E. J. Status of moose populations and challenges to moose management in Fennoscandia. Alces 39(10) (2003).

Araújo, M. B. & Alagador, D. Expanding European protected areas through rewilding. Curr. Biol. (2024).

Wilmers, C. C. & Schmitz, O. J. Effects of gray wolf-induced trophic cascades on ecosystem carbon cycling. Ecosphere 7 (10), e01501 (2016).

Petersen, T. K. et al. Airborne laser scanning reveals uniform responses of forest structure to moose (Alces alces) across the boreal forest biome. J. Ecol. (2023).

De Vriendt, L. et al. Heavy browsing pressure by moose (Alces alces) can interfere with the objectives of ecosystem-based forest management. For. Ecol. Manag. 549, 121483 (2023).

Salisbury, J. et al. Net climate effects of moose browsing in early successional boreal forests by integrating carbon and albedo dynamics. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 128 (3), e2022JG007279 (2023).

Running, S. & Zhao, M. MODIS/Terra Net Primary Production Gap-Filled Yearly L4 Global 500m SIN Grid V061. 2021, distributed by NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center. https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MOD17A3HGF.061 (2021).

Mykrä, S. & Pohja-Mykrä, M. Back-calculation of Large Carnivore Populations in Finland in 1865–1915. In Annales Zoologici Fennici (BioOne, 2015).

Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (NIBIO), Arealressurskart - AR50. https://nibio.no/tema/jord/arealressurser (2022).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/ (2024).

Pebesma, E. J. Simple features for R: standardized support for spatial vector data. R. Journal 10 (1), 439. https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2018-009 (2018).

Hijmans, R. terra: Spatial Data Analyais. R package version 1.7–78. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=terra (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under Grant Agreement No. 869471 (CHARTER), the Nordic Borealization Network (NordForsk University Cooperation, project nr. 164079) and Norwegian Environment Agency (contract number 22047007). JDCL was funded by the European Biodiversity Partnership in the context of the TransWILD project under the 2021-2022 BiodivProtect joint call, co-funded by the European Commission (GA No. 101052342) and the Research Council of Norway (project 342821). ALK, EJS and JM were financed by the Research Council of Norway (project no. 160022/F40 NINA basic funding).

Funding

Open access funding provided by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS collated and curated the carnivore data. EJS and GA collated and curated the herbivore data. JDMS and AS analysed data with support from GA, JDCL, JM, ALK and EJS. JDMS wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Speed, J.D.M., Sobocinski, A., Kolstad, A.L. et al. The trophic distribution of biomass in ecosystems with co-occurring wildlife and livestock. Sci Rep 15, 1474 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85469-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85469-2