Abstract

The most common treatment method for patients with acute ischemic stroke with large vessel occlusion is mechanical thrombectomy. However, complications such as cerebral edema and hemorrhage transformation after MT can affect patient prognoses, while decompression craniectomy considerably improves patient prognoses. The aim of this study was to identify clinical indicators, such as the neutrophil/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio, to predict DC. A retrospective analysis was conducted in AIS-LVO patients who received MT at Huizhou Central People’s Hospital and the Affiliated Hospital of Guilin Medical University. The patients were randomly divided into training, internal validation group and external validation group sets to generate and validate a nomogram model. Multivariate binary logistic analyses indicated that SBP > 178.5 mmHg, WBC > 12.05*109/L, PT > 14.54 s, and NHR > 8.874*109/mmol were independent risk factors for DC after MT in patients with AIS-LVO. In the training set, the area under the curve indicated good accuracy. Calibration curve results showed the average error in the training set was 0.038, and 0.036 in the validation set, showing good model fit. NHR was an independent risk factor for DC treatment after MT in AIS-LVO patients. A nomogram based on NHR accurately predicted if DC treatment was required after MT in patients with AIS-LVO.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stroke is one of the main diseases causing disability and death. From epidemiological data, the prevalence rate of stroke in China is approximately 11%, and the mortality rate is approximately 1/10001. Acute ischemic stroke with large vessel occlusion (AIS-LVO) accounts for 9%–27% of all stroke cases2.

AIS treatment is facilitated by opening blocked blood vessels as soon as possible and saving the ischemic penumbra. For patients with AIS-LVO, recanalization rates in occluded vessels are low, and long-term prognoses are poor for those administered intravenous thrombolytic therapy. Thanks to the development of interventional therapy technologies for cerebrovascular diseases, endovascular interventional therapies, such as arterial thrombolysis, stent implantation, and mechanical thrombectomy are increasingly used at early disease stages. Several studies have reported that for patients with AIS-LVO in the anterior circulation, endovascular therapy, mainly mechanical thrombectomy (MT) exerts significant health benefits3,4,5,6,7.

Decompression craniectomy (DC) is a surgical AIS intervention and one of the most important rescue treatments for patients with AIS-LVO. The necessity of DC after MT mainly depends on the patient’s specific condition and surgical indication. According to the latest medical guidelines and research, DC is recommended in certain circumstances, such as for some stroke patients undergoing MT, In particular, patients with severe complications following AIS such as hemorrhage transformation due to cerebral edema or large infarction, midline displacement of more than 5 mm, and neurological deterioration after MT, higher baseline NIHSS score, lower admission GCS score, and unsuccessful revascularization. In a multicenter registry, 9% of acute ischemic stroke patients (< 60 years) treated with MT required decompression craniotomy8. A recent study showed that DC for large hemispheric infarction improved survival and reduced disability rates9. Currently, controversy remains on the timing of DC10. The procedure is often performed after brain herniation, which greatly reduces patient prognoses. In view of this, clinicians need to use early and convenient clinical indicators to facilitate rapid treatment and decision-making.

At present, more and more researchers have explored the correlation between inflammatory markers and AIS. For example, Lux et al.11 have proposed the relationship between neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio and lymphocyte-monocyte ratio and clinical outcomes at 3 months after mechanical thrombus resection after stroke. Oh et al.12 proved that higher NLR, higher MHR, and lower LMR were closely related to the poor prognosis of patients after MT. Li et al.13 found that higher RPR, MHR, and NLR may be independent risk factors for predicting poor 3-month prognosis in AIS patients receiving MT. However, there are few studies on the relationship between NHR and AIS, the neutrophil count to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio (NHR) is a clinically accessible inflammation indicator. Stroke, which causes brain injury, induces multiple mechanisms, including cell excitotoxicity, oxidative stress, and inflammatory responses14. Neutrophils are components of the inflammatory response system and have important roles in inflammation15. High-density lipoprotein-C (HDL-C) prevents free cholesterol and triglyceride accumulation in blood vessels and suppresses lipid plaque formation. When compared with other reported serological biomarkers, including matrix metalloproteinase-9, growth differentiation factor-15, and thioredoxins16,17, NHR is readily accessible. Therefore, we explored the relationship between NHR and AIS-LVO patients to determine if DC was required after MT and to construct a nomogram prediction model using routine blood indicators.

Data and methods

Participants

We retrospectively analyzed patients with AIS-LVO who underwent MT at Huizhou Central People’s Hospital and the Affiliated Hospital of Guilin Medical University between January 2019 and January 2023. Inclusion criteria: (1) National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score ≥ 6; (2) Brain-computer tomography angiography (CTA), Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), or Digital Substracted Angiography (DSA) confirmed for internal carotid or middle cerebral artery cerebral infarction; (3) age > 18 years; and (4) MT during the time window. We excluded the following: (1) patients with no blood indicators within 24 h after admission; (2) patients with a previous history of cerebral infarction; (3) patients with a history of infection in the previous 3 weeks; (4) patients undergoing recent radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or immunotherapy; and (5) patients refusing treatment.

Data collection and processing

At admission, we collected patient clinical data, including age, sex, systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), affected side, responsible artery, hypertension, smoking, alcohol, atrial fibrillation (AF), and hyperlipidemia history. Also, blood routine examinations, comprehensive metabolic panels, and coagulation function indices were collected within 24 h, including peripheral blood white blood cell (WBC) counts, neutrophil (NE) counts, lymphocyte counts, monocyte counts, platelet counts, prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thrombin time (APTT), D-dimer (D-D) results, fibrinogen, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), albumin levels, and neutrophil count to HDL-C ratios (NHR). Patients undergoing DC during hospitalization were considered a study endpoint.

Statistical analysis

SPSS 25.0 and R-4.2.2 were used for all statistical analyses. We randomly divided patients from Huizhou Central People’s Hospital into an internal validation set and a training set in a ratio of 3:7. In addition, we used patients from the Affiliated Hospital of Guilin Medical University as external validation sets. Data were tested for normality, and results conforming to normal distributions were represented using the mean ± standard deviation and compared using Student’s t-tests. Data not conforming to normal distributions were represented by the median (inter-quartile range) (M (IQR)), and compared using Mann–Whitney U tests. Statistical data were expressed as quantity (percentages N (%)) and comparisons between groups were performed using chi-squared or Fisher’s tests. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. In the training set, for statistically significant variables, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated and the best cutoff values were divided into high and low groups. Non-statistically significant variables were divided into high and low groups by the mean. We calculated the AUC through the ROC curve, to select the truncation value with the largest AUC as the best truncation value, and then convert the continuous variable into the binary variable according to the truncation value for subsequent statistical analysis.

A univariate logistics regression model was constructed for grouped variables, and the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Statistically significant variables from univariate analyses were included in the multivariate logistics regression model to select independent influencing factors. Statistics were two-sided and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistically significant factors from multivariate logistics analyses were plotted in forest plots (GraphPad Prism 8). The nomogram prediction model was constructed in R-4.2.2 to calculate the area under the curve (AUC) in ROC curves in training and validation sets to assess prediction performance. Calibration curves for training and validation sets were drawn to assess the coincidence degree. Model decision curve analysis (DCA) was also performed.

Results

Baseline characteristics

We recruited 397 patients with AIS-LVO, and SPSS was used to randomly determine training (n = 170), internal validation sets (n = 73), and external validation sets (n = 154) (Fig. 1). The mean age in the training set was 56 years (51, 64), with 112 men and 58 women. The average SBP was 148 (129, 165) mmHg and DBP was 85.5 (76, 97) mmHg. In this group, 82 patients had left lesions and 97 had the middle cerebral artery as the main lesion. Also, 55.3% of patients had hypertension, 20.6% had AF, 22.4% had hyperlipidemia, 42.4% had a history of smoking, and 17.1% had an alcohol history.

The mean age in the internal validation group was 56 years (51, 64), with 55 men and 18 women. The average SBP was 143 (122, 158) mmHg, and DBP was 86 (77, 95) mmHg. In this group, 34 patients had left-sided lesions and 38 had the middle cerebral artery as the main lesion. Also, 56.2% of patients had hypertension, 24.7% had AF, 20.5% had hyperlipidemia, 34.2% had a history of smoking, and 9.6% had an alcohol history.

No statistical significance was recorded in baseline data between groups (P > 0.05); baseline data were comparable (Table 1).

Statistical results

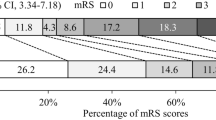

In the training group, SBP at admission, peripheral blood WBC, NE counts, D-D counts, and NHRs were statistically significant (Table 2). These variables underwent ROC curve analysis (Fig. 2) to calculate the best cutoff values (Table 3), with patients with the best cutoff values divided into high and low groups. Statistically significant variables were divided into high and low groups using the mean. After grouping continuous variables into categorical variables, univariate logistics regression results showed that for the responsible artery, SBP, WBC, NE, PT, D-D, and NHR were statistically significant (P < 0.05) (Table 4). After including data in multivariate logistics regression analyses, SBP (OR = 3.76, 95% CI 1.34–10.51, P = 0.012), WBC (OR = 3.65, 95% CI 1.36–9.77, P = 0.01), PT (OR = 2.58, 95% CI 1.12–5.94, P = 0.26), and NHR (OR = 3.17, 95% CI 1.23–8.17, P = 0.017) were independent risk factors (Table 5) for AIS-LVO patients undergoing DC after MT. To visualize data, forest plots were drawn to indicate independent risk factors (Fig. 3).

Constructing and validating a nomogram model

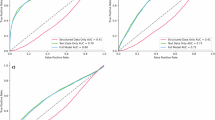

A nomogram prediction model (Fig. 4) for patients with AIS-LVO was assembled. SBP, WBC, and PT were continuous variables, while NHR was a categorical variable: 0 and 1 represented NHR ≤ 8.874 and NHR > 8.874, respectively. Each group in the nomogram corresponded to a score and the scores of each clinical variable were added to generate the total score. The total score matched the risk at the bottom of the nomogram, obtaining the probability further to undergoing DC for each AIS-LVO patient. Then, we assembled ROC and calibration curves and a DCA for training and validation sets. The AUC of the ROC curve for the training set = 0.769 (95% CI 0.69–0.849). The AUC of the ROC curve for the validation set = 0.672 (95% CI 0.54–0.804) (Fig. 5), these results showed that nomogram prediction performances were good. The training-set calibration curve showing the average error between predicted and actual risk in the prediction model was 0.038. The validation set calibration curve had an average error was 0.036 (Fig. 6) and showed that prediction and observation results were largely consistent. DCA for training and validation sets showed the nomogram was clinically significant (Fig. 7).

Discussion

Patients with AIS-LVO have extremely high mortality rates; approximately one-third deteriorate due to brain swelling, with dehydration drugs such as mannitol prescribed as temporary measures before DC18. DC is an important option for treating ischemic brain swelling, with more studies now indicating that early DC benefits patients. However, early predictors are required to help clinicians make timely and rapid decisions19,20,21. Most clinical reports and laboratory tests cannot predict DC or treat the condition18. Therefore, early DC predictors must be identified and validated.

In this study, SBP, WBC, PT, and NHR were independent risk factors for AIS-LVO patients undergoing DC after MT. Patients with AIS may have severe complications due to elevated BP, so BP must be decreased. It is generally accepted that patients with high BP (SBP > 180 mmHg and DBP > 100 mmHg) before MT are prone to bleeding transformation and require DC22. PT is an extrinsic pathway indicator. PT increases in patients with AIS may indicate bleeding transformation, which causes brain herniation and requires DC. However, no studies have articulated this view, so further investigations are required.

AIS-mediated cerebral ischemic stroke is a considerable stress that causes several responses leading to increased vasodilation and permeability to break the blood–brain barrier. The process is related to WBC, NE, T cell, and macrophage entry into damaged tissue23. Inflammatory and immune responses play key roles in cerebral ischemic stroke development24; microglia and astrocytes are rapidly activated, leading to cytokine and chemokine production and culminating in leukocyte infiltration25. Leukocytosis is an inflammatory response marker after cerebral infarction26. In addition, neutrophils, the most common marker of acute inflammation, are associated with stroke severity and infarct size, as reported in clinical studies27. In cerebral infarction ischemic tissue, neutrophils are the first blood-derived immune cells to invade28; they produce oxygen free radicals, release matrix metalloproteinases, aggravate inflammatory reactions, release proteolytic enzymes to damage endothelial cells, destroy the blood–brain barrier, cause brain tissue edema, and aggravate the cerebral infarction26.

HDL-C is an important component of HDL and an important lipoprotein receptor for intracellular cholesterol efflux, which removes excess cellular cholesterol and maintains intracellular cholesterol metabolism. Normal HDL-C levels in the peripheral blood resist inflammation and oxidative effects to protect the vascular endothelium. However, lower HDL-C levels are significantly associated with cardiovascular events29. More importantly, HDL-C has the ability to inhibit neutrophil activation, attachment, diffusion, and migration. NHR is an important inflammation indicator and reflects relationships between tissue inflammation and oxidative stress via neutrophils and HDL-C. In patients with AIS-LVO after MT, studies have shown that post-stroke inflammation and its impact on the blood–brain barrier exacerbate the bleeding transition30. On the one hand, neutrophils invade the ischemic area and release pro-inflammatory cytokines, which aggravate brain injury and destroy the blood–brain barrier31. On the other hand, HDL can be anti-inflammatory and protect the blood–brain barrier by preventing inflammatory cells from adhering to endothelial cells and reducing the oxidation of LDL32. In our study, it was found that patients with poor prognosis after MT surgery had higher NHR levels, which may be mainly due to the fact that neutrophils are the main subgroup of white blood cells that respond to early infection after MT surgery in AIS patients, and a large number of activated neutrophils can affect the composition and function of HDL-C by changing the structure and the contents of various apolipoproteins, for example, by degrading apolipoprotein E (apoE), apoA-I and apolipoprotein a-ii (apoA-II), the reverse transport function of cholesterol is reduced, leading to acute cerebral infarction33,34. Secondly, it was found in an animal model that HDL-C and apoA-I, as the main component proteins, may interfere with the release of neutrophils by inhibiting the synthesis of cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-1β, improve the neutrophil-clearing efficiency of the body in inflammatory tissues, and inhibit the neutrophil-mediated inflammatory response35. However, studies have shown that little apoA-I in HDL-C in AIS patients, so the clearance of neutrophils by apoA-I is also impaired36. Overall, NHR increases in AIS patients due to the decreased level of apoA-I in AIS patients, which in turn reduces the effect of HDL-C on neutrophil development, differentiation, and adhesion. In addition, according to some previous studies, patients with high NHR levels have an increased risk of acute myocardial infarction, which proves that the relationship between NHR and cardiovascular disease death is linear37. In the nomogram we prepared, it can be found that the greater the NHR, the higher the incidence of adverse prognosis, which is consistent with most previous studies. So, we think it can be used as a strong predictor. In summary, in AIS patients after MT, NHR may increase the risk of AIS through abnormal inflammatory activity and lipid metabolism due to the interaction of increased neutrophils and decreased HDL-C, thus increasing the need for DC.

The nomogram is widely used in cancer, medicine, surgery, and other medical fields and has become a key component of modern medical decision-making38,39,40. Compared with traditional prediction methods, the nomogram can provide a more accurate individualized prognosis assessment of disease, thus effectively assisting the medical decision-making process41. This advantage may be due to the fact that traditional risk grouping methods group patients with similar characteristics, which leads to intra-group heterogeneity, which in turn affects the accuracy of predictions. In contrast, a nomogram can provide a personalized prediction probability based on an individual’s disease characteristics, avoiding the need to average or mix individual data. It can transform complex regression equations into intuitive graphs, making the prediction results clearer and easier to understand and facilitate the evaluation of patients’ conditions. For example, Longyan Meng and colleagues constructed an accurate nomographic model based on advanced age, bleeding conversion, TICI score, NIHSS score, and NLR to predict the likelihood of adverse outcomes after mechanical thrombus resection. The model provides clinicians with a valuable tool for rapid and personalized preoperative risk assessment in elderly patients aged 72 years and older. It verified that the AUC-ROC curve of the prediction model was 0.803. It mainly predicted adverse outcomes after MC in older patients over 72 years, and its predictive value in younger patients is questionable42. For another example, Manuel Cappellari and colleagues developed an IER-SICH histogram based on NIHSS scores, onset-to-end procedure time, patient age, unsuccessful recanalization, and Careggi collateral scores. To predict the risk of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage in stroke patients with anterior circulation large vessel occlusion treated with mechanical thrombectomy43. This tool helps guide clinical decision-making further. The AUC-ROC curve of the nomogram for predicting the probability of sICH was 0.778 in the training set and 0.709 in the validation set, which mainly predicted the likelihood of sICH in patients with circulatory LVO stroke who underwent mechanical thrombectomy. In this study, the AUC-ROC curve of our nomogram prediction model for AIS-LVO patients was 0.769 in the training set and 0.672 in the validation set. In addition, this study has certain predictive value for both young and old patients and patients with anterior or posterior circulation, and the target population is wide. Therefore, the model shows good prediction accuracy and excellent generalization, which is consistent with most current research results.

However, the AUC curve of the verification set of this model is lower than that of the training set, and there are some differences, mainly due to the following two reasons: 1. We are not getting enough cases; 2. The number of arguments we set is relatively small. For example, Cappellari et al. included 1767 subjects. They set 5 variables, and the area under the curve obtained in the training set (0.778) and the verification set (0.709) was more accurate than the model in this study. Another example is Wang et al., who built a prediction model for aspiration pneumonia in patients with acute ischemic stroke, which included 3258 AIS patients and set 11 variables. The area under the curve obtained was 0.872 in the training set and 0.847 in the validation set, which was much more accurate than ours44. The development of our model in the current overall academic environment is insufficient, and this study just fills the blank of such a model. However, compared with other studies, this study has shortcomings, such as a temporary lack of case numbers and insufficient variables, for which we will have further extension plans.

In addition, the model developed by Longyan Meng and Manuel Cappellari was mainly composed of symptom scores, clinical manifestations, and patients’ baseline data, and some clinical data was difficult to evaluate and obtain. In contrast, the nomogram of this study mainly developed a new type of inflammatory marker’s impact on patient prognosis, which can be easily obtained through hospital admission and improved blood draw examination, and relevant data can be calculated from complete blood count and can be easily used through clinical case browsing, which is fast and convenient, reflecting the high clinical applicability of this model. It is a useful tool for clinicians to perform visualization and rapid risk assessment and can be widely used in patient clinical decision-making. For example, in clinical practice, we can calculate the NHR, WBC, PT, and SBP data of patients through admission screening so that preoperative risk assessment of patients can be completed at the time of admission. For patients with high preoperative risk assessment, we can inform patients and their families of relevant assessment risks after MT and perform preventive DC. In this way, the possibility of a poor prognosis can be avoided.

Thus, in this study, based on NHR, WBC, PT, and SBP, we constructed a nomogram to predict which AIS-LVO patients required DC after MT. The model showed good predictive performance and accuracy, was fully validated in a validation set, and facilitated correct and rapid clinical decision-making.

Study limitations

Our study had some limitations. DC indications may differ between different medical centers and affect statistical results. Serological data can continue to increase to facilitate a comprehensive assessment of risk factors. Therefore, a multi-center design is required for prospective validation studies.

Conclusions

NHR is an independent risk factor for AIS-LVO patients undergoing DC after MT. The nomogram was based on NHR and accurately predicted if AIS-LVO patients required DC after MT. The higher the level of NHR, WBC, PT, and SBP of patients, the greater the possibility of adverse prognosis of patients after MT surgery, which suggests that we may need to pay close attention to the changes in patient’s conditions and, if necessary, advance DC treatment can avoid the occurrence of adverse prognosis. Therefore, this model provides a treatment basis and decision-making tool for clinicians in the early stage of the disease.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

- AIS:

-

Acute ischemic stroke

- AIS-LVO:

-

Acute ischemic stroke with large vessel occlusion

- MT:

-

Mechanical thrombectomy

- DC:

-

Decompression craniectomy

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- NHR:

-

Neutrophil to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio

- CTA:

-

Computer tomography angiography

- MRA:

-

Magnetic resonance angiography

- DSA:

-

Digital substracted angiography

- AF:

-

Atrial fibrillation

- WBC:

-

White blood cell

- MC:

-

Monocyte count

- NE:

-

Neutrophil count

- Lym:

-

Lymphocyte

- PLT:

-

Platelet

- PT:

-

Prothrombin time

- APTT:

-

Activated partial thrombin time

- FIB:

-

Fibrinogen

- LDL-C:

-

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- ALB:

-

Albumin

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- AUC:

-

The area under the curve

- DCA:

-

Decision curve analysis

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

References

Wang, W. et al. Prevalence, incidence, and mortality of stroke in China: Results from a nationwide population-based survey of 480 687 adults. Circulation 135(8), 759–771 (2017).

Khandelwal, P., Yavagal, D. R. & Sacco, R. L. Acute ischemic stroke intervention. J. Am. College Cardiol. 67(22), 2631–2644 (2016).

Goyal, M. et al. Randomized assessment of rapid endovascular treatment of ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 372(11), 1019–1030 (2015).

Berkhemer, O. A. et al. A randomized trial of intraarterial treatment for acute ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 372(1), 11–20 (2015).

Campbell, B. C. et al. Endovascular therapy for ischemic stroke with perfusion-imaging selection. N. Engl. J. Med. 372(11), 1009–1018 (2015).

Saver, J. L. et al. Stent-retriever thrombectomy after intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA alone in stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 372(24), 2285–2295 (2015).

Jovin, T. G. et al. Thrombectomy within 8 hours after symptom onset in ischemic stroke. N. Engl. J. Med. 372(24), 2296–2306 (2015).

Adwane, G. et al. Frequency and predictors of decompressive craniectomy in ischemic stroke patients treated by mechanical thrombectomy in the ETIS registry. Rev. Neurol. 180(3), 177–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurol.2023.08.014 (2024).

Zhao, J. et al. Decompressive hemicraniectomy in malignant middle cerebral artery infarct: A randomized controlled trial enrolling patients up to 80 years old. Neurocritical Care 17(2), 161–171 (2012).

Hawryluk, G. W. J. et al. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury: 2020 update of the decompressive craniectomy recommendations. Neurosurgery 87(3), 427–434 (2020).

Lux, D. et al. The association of neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and lymphocyte-monocyte ratio with 3-month clinical outcome after mechanical thrombectomy following stroke. J. Neuroinflammation 17(1), 60. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-020-01739-y (2020).

Oh, S. W., Yi, H. J., Lee, D. H. & Sung, J. H. Prognostic significance of various inflammation-based scores in patients with mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke. World Neurosurg. 141, e710–e717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2020.05.272 (2020).

Li, X. et al. Novel peripheral blood cell ratios: Effective 3-month post-mechanical thrombectomy prognostic biomarkers for acute ischemic stroke patients. J. Clin. Neurosci. 89, 56–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2021.04.013 (2021).

Moskowitz, M. A., Lo, E. H. & Iadecola, C. The science of stroke: Mechanisms in search of treatments. Neuron 67(2), 181–198 (2010).

Manoochehri, H., Gheitasi, R., Pourjafar, M., Amini, R. & Yazdi, A. Investigating the relationship between the severity of coronary artery disease and inflammatory factors of MHR, PHR, NHR, and IL-25. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran https://doi.org/10.47176/mjiri.35.85 (2021).

Jeong, H. S. et al. Association of plasma level of growth differentiation factor-15 and clinical outcome after intraarterial thrombectomy. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. Off. J. Natl. Stroke Assoc. 29(8), 104973 (2020).

Zang, N. et al. Biomarkers of unfavorable outcome in acute ischemic stroke patients with successful recanalization by endovascular thrombectomy. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 49(6), 583–592 (2020).

Adams, H. P. Jr. et al. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: A guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke council, clinical cardiology council, cardiovascular radiology and intervention council, and the atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease and quality of care outcomes in research interdisciplinary working Groups: The American Academy of neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Circulation 115(20), e478-534 (2007).

Schwab, S. et al. Early hemicraniectomy in patients with complete middle cerebral artery infarction. Stroke 29(9), 1888–1893 (1998).

Sakai, K. et al. Outcome after external decompression for massive cerebral infarction. Neurol. Medico-Chirurgica 38(3), 131–136 (1998).

Robertson, S. C., Lennarson, P., Hasan, D. M. & Traynelis, V. C. Clinical course and surgical management of massive cerebral infarction. Neurosurgery 55(1):55–61 (2004). Discussion-2.

Powers, W. J. et al. 2018 Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 49(3), e46–e99 (2018).

Arumugam, T. V., Granger, D. N. & Mattson, M. P. Stroke and T-cells. Neuromolecular Med. 7(3), 229–242 (2005).

Feng, Y. et al. Postoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio predicts unfavorable outcome of acute ischemic stroke patients who achieve complete reperfusion after thrombectomy. Front. Immunol. 13, 963111 (2022).

Jin, R., Yang, G. & Li, G. Inflammatory mechanisms in ischemic stroke: Role of inflammatory cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 87(5), 779–789 (2010).

Jayaraj, R. L., Azimullah, S., Beiram, R., Jalal, F. Y. & Rosenberg, G. A. Neuroinflammation: Friend and foe for ischemic stroke. J. Neuroinflamm. 16(1), 142 (2019).

Kim, J. et al. Different prognostic value of white blood cell subtypes in patients with acute cerebral infarction. Atherosclerosis 222, 464–467 (2012).

Ceulemans, A.-G. et al. The dual role of the neuroinflammatory response after ischemic stroke: Modulatory effects of hypothermia. J. Neuroinflamm. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-7-74 (2010).

Briel, M. et al. Association between change in high density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality: Systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Bmj 338, b92 (2009).

Xia, L. et al. High ratio of monocytes to high-density lipoprotein is associated with hemorrhagic transformation in acute ischemic stroke patients on intravenous thrombolysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 977332 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. The association between monocyte to high-density lipoprotein ratio and hemorrhagic transformation in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Aging 12, 2498–2506 (2020).

Enciu, A. M., Gherghiceanu, M. & Popescu, B. O. Triggers and effectors of oxidative stress at blood-brain barrier level: Relevance for brain ageing and neurodegeneration. Oxidat. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013, 297512 (2013).

Bergt, C. et al. Human neutrophils employ the myeloperoxidase/hydrogen peroxide/chloride system to oxidatively damage apolipoprotein A-I. Eur. J. Biochem. 268, 3523–3531 (2001).

Cogny, A., Atger, V., Paul, J. L., Soni, T. & Moatti, N. High-density lipo-protein 3 physicochemical modifications induced by interaction with human polymorphonuclear leucocytes affect their ability to remove cholesterol from cells. Biochem. J. 314, 285–292 (1996).

Scanu, A. et al. High-density lipoproteins inhibit urate crystal-induced inflammation in mice. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 74, 587–594 (2015).

Ortiz-Munoz, G. et al. Dysfunctional HDL in acute stroke. Atherosclerosis 253, 75–80 (2016).

Jiang, M. et al. Prognostic role of neutrophil to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in the general population. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 807339 (2022).

Callegaro, D. et al. Development and external validation of two nomograms to predict overall survival and occurrence of distant metastases in adults after surgical resection of localised soft-tissue sarcomas of the extremities: A retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 17(5), 671–680. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00010-3 (2016).

Jehi, L. et al. Development and validation of nomograms to provide individualised predictions of seizure outcomes after epilepsy surgery: A retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 14(3), 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70325-4 (2015).

Hijazi, Z. et al. The novel biomarker-based ABC (age, biomarkers, clinical history)-bleeding risk score for patients with atrial fibrillation: A derivation and validation study. Lancet 387(10035), 2302–2311. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00741-8 (2016).

Shariat, S. F., Karakiewicz, P. I., Suardi, N. & Kattan, M. W. Comparison of nomograms with other methods for predicting outcomes in prostate cancer: A critical analysis of the literature. Clin. Cancer Res. 14(14), 4400–4407. https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4713 (2008).

Meng, L. et al. Nomogram to predict poor outcome after mechanical thrombectomy at older age and histological analysis of thrombus composition. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 8823283. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8823283 (2020).

Cappellari, M., Mangiafico, S., Saia, V., et al. IER-SICH Nomogram to Predict symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage after thrombectomy for stroke [published correction appears in stroke. 50(11), e341 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1161/STR.0000000000000209]. Stroke. 50(4), 909–916 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.023316

Wang, J. et al. Construction and evaluation of a nomogram prediction model for aspiration pneumonia in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Heliyon 9(11), e22048. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22048 (2023).

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Z. designed this study. Y.W. and J.X. are responsible for writing articles, conducting statistical analysis, reviewing articles, and creating images. H.L. responsible for collecting data and conducting statistical analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013) and was approved by the the Huizhou Central People’s Hospital Ethics Review Committee. The requirement for informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of Huizhou Central People’s Hospital because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, Y., Xiao, J., Luo, H. et al. Nomogram model for decompressing craniectomy after mechanical thrombectomy in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Sci Rep 15, 2726 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85538-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85538-6