Abstract

In this paper, we discuss quantum friction in a system formed by two metallic surfaces separated by a ferromagnetic intermedium of a certain thickness. The internal degrees of freedom in the two metallic surfaces are assumed to be plasmons, while the excitations in the intermediate material are magnons, modeling plasmons coupled to magnons. During relative sliding, one surface moves uniformly parallel to the other, causing friction in the system. By calculating the effective action of the magnons, we can determine the particle production probability, which shows a positive correlation between the probability and the sliding speed. Finally, we derive the frictional force of the system, with both theoretical and numerical results indicating that the friction, like the particle production probability, also has a positive correlation with the speed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the study of condensed matter physics, the discussions on frictional forces in microscopic systems are always of interest. In these systems, the quantum fluctuations play a crucial role in the dissipation process of frictional force. Generally speaking, the internal relative motion can excite the internal degrees of freedom (DOFs) of the system through the interaction between these internal DOFs, which leads to the production of quasi-particles by the kinetic energy of the internal relative motion. Accordingly, the energy dissipation processes of the frictional force in different systems are carried out by different elementary excitations, such as phonons, electrons, plasmons, magnons, etc 1,2,3,4. At high temperatures, the dissipation process is usually dominated by phonons, and the classical dynamics of the phonons make the major contribution. As the temperature decreases, quantum dynamics gradually come into play, and in the dissipation processes, electrons, plasmons, or other collective excitations take on dominant roles. In the past, the corresponding friction in these processes has been widely studied 5,6,7,8,9,10, and with the development of experimental technology, magnetic friction has also been observed 11. The dissipation of this friction is carried out by magnons, so magnetic friction is also called spin friction.

As magnetic materials are controlled down to the nanometer scale, the dissipation and friction in quantum spin systems have attracted considerable interest. The occurrence of magnetic friction was studied theoretically using a nanometer-sized tip scanning a magnetic surface, examining the dynamics of a classical spin model interacting through dipolar and exchange interactions 12. And a similar approach was also applied to discuss the temperature-dependence of the magnetic friction 13. Kadau studied the magnetic friction between two Ising spin systems and found that near the critical temperature the friction is the strongest 11. These works all focused on purely classical models. By considering the contribution of quantum fluctuations, we found the bosonic model to be almost equivalent to the general model of electronic friction, by transforming the Heisenberg model into a bosonic model via the Holstein-Primakoff transformation 14. The above studies on frictional force are based on models that the interfaces consist of two identical surfaces or one surface coupled to a nanoparticle. In reality, friction usually occurs at interfaces composed of two different materials, and in many cases, quantum spins can lead to friction by interacting with other DOFs. Johan, Brevik and et al studied the Casimir friction between a magnetic and a dielectric material. In this work, the internal DOFs of the magnet were modeled as a single frequency quantum oscillator to obtain the temperature-dependence of the magnetic friction 15. However the contribution of dispersive magnons has not been discussed, and additionally, the dissipation and frictional force mediated by a intermedium instead of vacuum gap have not been considered.

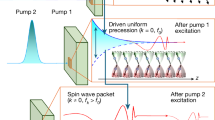

Most quantum friction models are sandwich-like, i.e., a vacuum gap sandwiched between two objects 5,8,15, and the excitations of the vacuum are always photons, refering to ‘photon-mediated friction’. In our study, we focus on the frictional force in the case of two objects separated by some intermedium whose excitations are quasi particles. Specifically, we build a model that the interface is formed by two metallic surfaces separated by a ferromagnetic intermedium. The internal DOFs of the both metallic surfaces are electrons and the excitations of the intermedium are magnons. The whole system is built as plasmons coupled to magnons, and the structure of the model is similar to the graphene plasmons form polaritons with the magnons of two-dimensional ferrromagnetic insulators 16. By relative sliding, one surface moves uniformly parallel to the other causing friction in the system. Our goal is to study the magnon-mediated plasmon friction, through calculation and analysis of the system’s effective action of the magnons, particle production probability and etc.

The remaining content of this paper is structured in the following manner. In Section 2, we introduce the model to study frictional force. Section 3 gives the effective action of the magnons in the system. Section 4 gives the calculation of the probability of particle production. In Section 5, we discuss the friction force of this system. And Section 6 is the summary of this work.

The model

In this study, we consider the system formed by two metallic surfaces separated by a ferromagnetic intermedium with thickness h, and the diagrammatic sketch of the model is shown in Figure 1. Due to the metallic nature of both surfaces, the primary basic excitations with spin on the two surfaces are bound to be electrons as the internal DOFs. The excitations of the intermedium are magnons. The structure of this model is similar to the graphene plasmons form polaritons with the magnons of two-dimensional ferrromagnetic insulators 16. By focusing on the case of plasmons coupled to magnons, our goal is to study the magnon-mediated plasmon friction. And also, we follow the natural unit such that \(\hbar =c=1\). Thus, the effective internal DOFs of the metallic surfaces that are coupled to the intermedium are assumed to be plasmons, and the Hamiltonian of this plasmons for the two metallic surfaces can be expressed as 17:

and

where \(\varvec{r}_{\parallel }=\begin{pmatrix}x,y\end{pmatrix}\) is the two dimensional Cartesian coordinates in the L-surface. Similar to the dispersion relation of massive particles, u is the group velocity of the plasmon. It is proportional to the Fermi velocity of electron, which is the Fermi momentum of the electron \(p_F\) divided by its mass \(m_F\). \(\Omega\) is the gap or proper frequency of the plasmon, \(\Omega ^2=4\pi e^2n_0/m_F\), where e is the elementary charge and \(n_0\) is the average density of electrons in the material. Here we denote the DOFs of the two surfaces via subscripts L and R, i.e., the R-surface and the L-surface. \(\phi _{R(L)}\) is the scalar field corresponding to the plasmon of R(L)-surface, and \(\pi _{R(L)}\) is the corresponding canonical momentum of the field. So \(H_L\) and \(H_R\) are Hamiltonians describing the scalar field of system. The integral measure \(\int \textrm{d}^2\varvec{r}_{\parallel }\) means \(\int _{-\infty }^{\infty } \textrm{d}x \int _{-\infty }^{\infty } \textrm{d}y\). For the magnons, the Hamiltonian is taken as 18:

where z is the third Cartesian coordinate Perpendicular to the L-surface. \(b(\varvec{r}_{\parallel },z)\) and \(b^\dagger (\varvec{r}_{\parallel },z)\) are the annihilation and creation operators of the Holstein-Primakoff bosons which describe the magnons 19. J is the interchange parameter of the Heinsenberg model, and S is the spin quantum number of the spin magnetic moment in the ferromagnet 20.

Inspired by the model of magnon-plasmon coupling 21, we define the coupling terms between R/L-surface and the magnet as:

and

Here \(C(\varvec{r}_{\parallel })\) is the interacting strength which is assumed to be \(\varvec{r}_{\parallel }\) dependent rather than t, and \(C^*(\varvec{r}_{\parallel })\) is the complex conjugation of \(C(\varvec{r}_{\parallel })\).

The transition amplitude from a ground state to the other is defined as \(Z=\langle 0|U_\textrm{I}(\frac{T}{2},-\frac{T}{2})|0\rangle\), where \(U_\textrm{I}(\frac{T}{2},-\frac{T}{2})\) is the time evolution operator of the system and \(|0\rangle\) refers to the ground state. This transition amplitude also can be written as a functional integral 22:

where \(\int \textrm{d}^4X=\int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\textrm{d}t \int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\textrm{d}x \int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\textrm{d}y \int _{-\infty }^{\infty }\textrm{d}z\), integrations over time t and the coordinates. Since the corresponding Lagrangian can be derived using the Legendre transformation, the free parts of the Lagrangian can be written as

and the interaction parts are expressed as:

and

The effective action of the magnons

In our model, the ferromagnet plays a mediating role in the coupling between the plasmons belonging to the R- and L-surface, i.e., the virtual magnons carry the interaction between the two surfaces, which makes it necessary to analyse the free Green’s function of the magnons. To achieve this goal, we first derive the effective action of the magnons via a functional integral:

Here, we define the four-dimensional space-time coordinates as \(X=(t,x,y,z)\) and \(X'=(t',x',y',z')\). Since it is Gaussian-like shape, the integral can be performed directly and the effective action of the magnon can be expressed as:

where the kernels are defined as the following Fourier transformations with an infinitesimal positive parameter \(\epsilon\):

and

These two kernels can be obtained by taking the second time derivative of the free time-ordered Green’s function of the plasmons. Note that the additional frequency factor \(\omega ^2\) results from the coupling between the canonical momentum of the plasmon and the magnon field. \(\varvec{k}_{\parallel }=\begin{pmatrix}k_x,k_y\end{pmatrix}\) is the Fourier momentum corresponding to \(\varvec{r}_{\parallel }\).

Since our purpose is to study frictional force, relative sliding is required in the system. Here we assume that the R-surface is moving uniformly parallel to the L-surface, and then the terms containing the plasmon DOFs should undergo a Galilean transformation, i.e.,

which makes the Green’s function of the R-plasmons transforms as:

Then the additional Green’s function of the magnons can be calculated via the functional integral from the effective action as follows 22:

The free Green’s function can be obtained by dropping the interaction terms in Eq (13). And in consideration of the boundary conditions of the ferromagnet, this free Green’s function of the magnons can be classified into four correlators:

-

a)

the bulk-bulk correlator: \(G_\textrm{F}(t-t',{\varvec{r}}_{\parallel }-{\varvec{r}}'_{\parallel };z-z')\),

-

b)

the R-surface correlator: \(G_\textrm{F}(t-t',\tilde{\varvec{r}}_{\parallel }-\tilde{\varvec{r}}'_{\parallel };z-z'=0)\),

-

c)

the L-surface correlator: \(G_\textrm{F}(t-t',{\varvec{r}}_{\parallel }-{\varvec{r}}'_{\parallel };z-z'=0)\),

-

d)

the R-L correlator: \(G_\textrm{F}(t-t',{\varvec{r}}_{\parallel }-{\varvec{r}}'_{\parallel };z-z'=h)\).

The subscript ‘F’ means Feynmann propagator which corresponds to the free Green’s function in Quantum Field Theory (QFT). Since the coupling between the plasmons and the magnons exists only on the surfaces, it is necessary to calculate the R-L correlator, which can be expressed through Fourier transformation using the standard approach as follows:

where the kernel \(G_\textrm{F}(\omega ,\varvec{k}_{\parallel };0-h)\) is defined via the inverse Fourier transformation:

and obviously, \(G_\textrm{F}(\omega ,\varvec{k}_{\parallel };0-h) = G^*_\textrm{F}(\omega ,\varvec{k}_{\parallel };h-0)\).

The probability of particle production

During the relative sliding, the accumulated energy results from particle production. To obtain the frictional force, we need to track the energy transfer in the system, making it necessary to determine the probability of particle production. Since our model assumes weak interaction, we can calculate the probability of particle production using perturbation theory.

The probability for the system staying at the ground state is \(|Z|^2\), so \(\mathscr {P}=1-|Z|^2\) means the probability of particle production. And \(\mathscr {P}\) can be calculated from the effective action of the magnons in Eq (13) via functional integral[16]:

where \(\Gamma\) is the collection of 1 particle irreducible(PI) diagram in QFT 22. In the perturbation expansion in powers of coupling strength, the sliding-dependent contribution to \(\textrm{Im}\Gamma\) always forms a series of terms, leading to a small \(\textrm{Im}\Gamma\), i.e.,

Thus, we the probability of particle production can be written as:

After performing the functional integral, we can obtain the expression for \(\Gamma\):

In general, the coupling strength \(|C(\varvec{r}{\parallel })|\) is sufficiently small for perturbation calculations, allowing \(\Gamma\) to be expanded in powers of \(|C(\varvec{r}{\parallel })|\). To the order of \(|C(\varvec{r}_{\parallel })|^4\), \(\Gamma\) can be written as:

Here the leading-order terms are not vanishing. However, physically speaking, the leading-order corresponds to the case where either the L- or R-surface is absent. Since our aim is to investigate the magnon-mediated plasmon friction between the two surfaces, we ignore the leading-order terms. Additionally, the terms in the absence of either of the two surfaces, \(\textrm{Tr}[|C|^4 G_\mathrm{{F}} \Delta _\mathrm{{R}} G_\mathrm{{F}} \Delta _\mathrm{{R}}]\) and \(\textrm{Tr}[|C|^4 G_\mathrm{{F}} \Delta _\mathrm{{L}} G_\mathrm{{F}} \Delta _\mathrm{{L}}]\), are not required, since we investigate the magnon-mediated plasmon friction between the two surfaces. Then the lowest ordered nontrivial contribution can be expressed as follows:

where T is the duration of the system and A is the total area of the surface. The kernels of R-plasmon and L-plasmon in frequency-momentum space can be obtained from Eq (14) and Eq (15) respectively as:

and

The integrand on the complex \(\omega\)-plane has only two poles, which depend on the relative velocity \(\varvec{v}\):

Here, we do not consider the antiparticles corresponding to the plasmons, because our model focuses on plasmon-magnon coupling, which is an effective interaction rather than a fundamental electromagnetic interaction. After substituting Eq (20), (27), and (28) into Eq (26), and evaluating the integral over \(\omega\) using the residue theorem [17], we obtain the expression for \(\Gamma\) as follows:

Note that \(\varvec{v}_{\parallel } \cdot \varvec{k}_{\parallel }\) can be regarded as the energy pumped into the system by the relative motion 23. Thus, by taking into account the identity,

Eq (30) can gives two Dirac \(\delta\)-functions \(\delta (\varvec{v}_{\parallel } \cdot \varvec{k}_{\parallel } - 2\sqrt{u^2\varvec{k}_{\parallel }^2+\Omega ^2})\) and \(\delta (\varvec{v}_{\parallel } \cdot \varvec{k}_{\parallel } - \sqrt{u^2\varvec{k}_{\parallel }^2+\Omega ^2} -JS\varvec{k}_{\parallel }^2)\). The former corresponds to plasmon excitation, while the latter corresponds to magnon-plasmon hybrid excitation on the R-surface. Since the magnons only play the role in mediating, here we only focus on the former case, and the corresponding probability of particle production can be written as:

with the condition \(-\varvec{v}_{\parallel } \cdot \varvec{k}_{\parallel } + \sqrt{u^2\varvec{k}_{\parallel }^2+\Omega ^2} +JS\varvec{k}_{\parallel }^2>0\), which means no magnon being excited. Without loss of generality, we set the velocity \(\varvec{v}_{\parallel }\) along the x-direction, i.e.,

Thus, the probability of particle production becomes:

By using the property of Dirac \(\delta\)-function,

the item of Dirac \(\delta\)-function in Eq (34) can be expressed as:

which gives a threshold speed \(v_P \ge 2u\), i.e., the plasmons are excited when the relative motion speed is bigger than 2u. This threshold speed is similar to the quantum friction between two graphene sheets 24. Obviously, here the probability decreases as the thickness of the ferromagnet increases.

To observe how the probability changes with increasing velocity v, we set the coupling strength \(C(\varvec{k}_{\parallel })\) to a constant value, denoted by the real-valued parameter C, and temporarily ignore the dispersion of the plasmons by setting \(u=0\). Then the probability of particle production can be expressed as follows:

Since this work is a theoretical study based on perturbative QFT, the results for particle production rate and friction originate from the perturbative expansion of the coupling strength C, which appears as a coefficient in the results. Our goal here is to explore the correlation between probability \(\mathscr {P}\) and speed v, which is independent of the constant coefficients C, A and T. Therefore, we use the probability of particle production as \(\mathscr {P}/(TAC^4)\) for numerical integration over \(k_y\), and show the result in Figure 2, which indicates a very significant and positive correlation between probability \(\mathscr {P}\) and speed v. In addition, the threshold speed \(v_\textrm{P}\) tend to zero naturally due to the elimination of the plasmons’ speed u.

Frictional force

According to the physical significance of \(\Gamma\), the energy accumulated by the excitations due to the relative motion can be expressed as:

And then we can write the dissipation power per unit area as:

where \(\varvec{F}_\textrm{fric}\) is the friction acting on the R-surface. After taking the same setup of Eq (33) as \(\textrm{Im}\Gamma\), the frictional force becomes:

Like the particles production rate of Eq (34), it has the same Dirac \(\delta\)-function, thus, the frictional force also corresponds to the same threshold speed \(v_\textrm{P}=2u\). Similar to \(\mathscr {P}\), the frictional force can be expressed as:

Similar to the probability \(\mathscr {P}\), to study the correlation between friction \(F_\textrm{fric}\) and speed v numerically, we also use the friction as \(F_\textrm{fric}/C^4\) and the result is shown in Figure 3. Like most frictional forces, here it is also positively correlated with speed.

As a natural and general outcome, the physical mechanism underlying the positive correlation between friction and v is that, as the sliding speed increases, more plasmons are excited between the two surfaces, resulting in greater energy dissipation and thus higher friction. However, exceptions exist; for instance, in the low-speed regime, friction initially increases with speed, but after reaching a certain threshold, it starts to decrease. Our previous work has explored such a model 8, and we are still working toward identifying a satisfactory physical mechanism to explain this phenomenon.

The numerical result in Figure 3 also shows that the frictional force is quadratic with respect to relative speed. The predicted quantum friction force is described by the non-analytic function of relative velocity v, which cannot be expanded in the Taylor series at \(v=0\). By performing a Taylor expansion of Eq (41) around \(v\rightarrow 0\), we can obtain:

From the numerical analysis in Fig. 3, it is clear that as \(v\rightarrow 0\), \(F_\textrm{fric}=0\). And the first-order coefficient with respect to v can be calculated as:

This indicates that, in the low-dissipation limit, friction does not exhibit linear dependence on speed. Thus, the frictional force can be expanded as a series in v, with the coefficient of the linear term being zero. In this study, we focus on the dissipative force generated by motion, which we define as a type of sliding friction. Consequently, other frictional forces that do not depend on motion, such as static friction, are not included in the model.

Additionally, the force decreases exponentially with increasing ferromagnetic layer thickness. This decay originates from Eq (20), where integrating over the z-component of momentum naturally leads to an exponential decay. The possible physical mechanism is as follows: Eq (20) describes the propagator of magnons within the ferromagnetic layer. When the system is confined in the z-direction, magnons transfer between the two surfaces, coupling with plasmons. As the magnons propagate, their energy gradually dissipates until they vanish, while the plasmons gain energy and become excited.

Conclusion

In this paper we have studied a magnon mediated friction between two metallic surfaces separated by a ferromagnetic intermedium with thickness h. The internal DOFs in the two metallic surfaces are assumed to be plasmons, while the excitations in the intermediate material are magnons. To study the frictional force in the system, we assume the R-surface is moving uniformly parallel to the L-surface at a constant velocity, creating relative sliding. The derivation starts from the effective action of the magnons, and then we analyse the free Green’s function of the magnons since these magnons carry the interaction between the two surfaces. To handle the energy transfer in the system for friction, it is necessary to address the probability of particle production.The theoretical approach to particle production probability shows that a threshold speed exists, and numerical analysis indicates a positive correlation between the probability and the speed. Finally, we derived the frictional force of the system, both the theoretical and numerical results agree with the behaviors of the particle production probability, i.e., the friction also has a positive correlation with the moving speed.

Furthermore, it is interesting to consider the case of a system with magnon-plasmon hybrid excitation. The probability of particle production can be expressed as

with the condition \(-\varvec{v}_{\parallel } \cdot \varvec{k}_{\parallel } + \sqrt{u^2\varvec{k}_{\parallel }^2+\Omega ^2} +JS\varvec{k}_{\parallel }^2<0\). Comparing Eq (40) with Eq (30), we can see that it is no exponential factor in Eq (40), which means the probability of magnon-plasmon hybrid excitations does not decrease as the thickness of the ferromagnet increases. This indicates that the corresponding frictional force must be independent of h.

Data availability

This article is a theoretical work and all data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Persson, B. N. J. & Spencer, N. D. Sliding Friction: Physical Principles and Applications. Physics Today 52, 66–68. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.882557 (1999).

Persson, B. Sliding friction. Surface Science Reports 33, 83–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-5729(98)00009-0 (1999).

Mason, B., Winder, S. & Krim, J. On the current status of quartz crystal microbalance studies of superconductivity-dependent sliding friction. Tribology Letters - TRIBOL LETT 10, 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009042816366 (2001).

Dayo, A., Alnasrallah, W. & Krim, J. Superconductivity-dependent sliding friction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 1690–1693. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.1690 (1998).

Pendry, J. B. Shearing the vacuum - quantum friction. Journal of Physics: Condensed Matter 9, 10301. https://doi.org/10.1088/0953-8984/9/47/001 (1997).

Zolfagharkhani, G., Gaidarzhy, A., Shim, S.-B., Badzey, R. L. & Mohanty, P. Quantum friction in nanomechanical oscillators at millikelvin temperatures. Phys. Rev. B 72, 224101. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.72.224101 (2005).

Kheiri, R. Quantum, “contact’’ friction: The contribution of kinetic friction coefficient from thermal fluctuations. Friction 11, 1877–1894. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40544-022-0719-1 (2023).

Wang, Y. & Jia, Y. Quantum dissipation and friction attributed to plasmons. Modern Physics Letters B 36, 2150589. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0217984921505898 (2022).

Ge, L. Negative vacuum friction in terahertz gain systems. Phys. Rev. B 108, 045406. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.108.045406 (2023).

Khosravi, F., Sun, W., Khandekar, C., Li, T. & Jacob, Z. Giant enhancement of vacuum friction in spinning yig nanospheres. New Journal of Physics 26, 053006. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/ad3fe1 (2024).

Kadau, D., Hucht, A. & Wolf, D. E. Magnetic friction in ising spin systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 137205. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.101.137205 (2008).

Fusco, C., Wolf, D. E. & Nowak, U. Magnetic friction of a nanometer-sized tip scanning a magnetic surface: Dynamics of a classical spin system with direct exchange and dipolar interactions between the spins. Phys. Rev. B 77, 174426. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.77.174426 (2008).

Magiera, M. P., Wolf, D. E., Brendel, L. & Nowak, U. Magnetic friction and the role of temperature. IEEE Transactions on Magnetics 45, 3938–3941. https://doi.org/10.1109/TMAG.2009.2023623 (2009).

Wang, Y. & Jia, Y. Dissipation and friction of a quantum spin system. Eur. Phys. J. B 95, 75. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjb/s10051-022-00330-z (2022).

Høye, J. S. & Brevik, I. Casimir friction between a magnetic and a dielectric material in the nonretarded limit. Phys. Rev. A 99, 042511. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.99.042511 (2019).

Costa, A., Vasilevskiy, M., Fernández-Rossier, J. & Peres, N. Strongly coupled magnon-plasmon polaritons in graphene-two-dimensional ferromagnet heterostructures. Nano letters 23, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.3c00907 (2023).

Nguyen, V. H. & Nguyen, B. H. Basics of quantum plasmonics. Advances in Natural Sciences: Nanoscience and Nanotechnology 6, 023001. https://doi.org/10.1088/2043-6262/6/2/023001 (2015).

Funaki, H. & Tatara, G. Calculation of the magnon drag force induced by an electric current in ferromagnetic metals. Phys. Rev. B 106, 134435. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.106.134435 (2022).

Rastelli, E. & Lindgard, P. A. Exact results for spin-wave renormalisation in heisenberg, and planar ferromagnets. Journal of Physics C: Solid State Physics 12, 1899. https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3719/12/10/021 (1979).

Miura, D. & Sakuma, A. Microscopic theory of magnon-drag thermoelectric transport in ferromagnetic metals. Journal of the Physical Society of Japan 81, 113602. https://doi.org/10.1143/JPSJ.81.113602 (2012).

Dyrdał, A., Qaiumzadeh, A., Brataas, A. & Barnaś, J. Magnon-plasmon hybridization mediated by spin-orbit interaction in magnetic materials. Phys. Rev. B 108, 045414. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.108.045414 (2023).

Wen, X.-G. Quantum Field Theory of Many-Body Systems: From the Origin of Sound to an Origin of Light and Electrons (Oxford University Press, 2007).

Volokitin, A. Quantum friction and graphene 1112, 4912 (2011).

Farias, M. B., Fosco, C. D., Lombardo, F. C. & Mazzitelli, F. D. Quantum friction between graphene sheets. Phys. Rev. D 95, 065012. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.95.065012 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the fruitful discussions with Qiang Sun, and thank Mingyang Liu for helping to check the manuscript. This research was supported by Dongying Science Development Fund(No. DJB2023015), Chuxiong Normal University Doctoral Research Initiation Fund Project(No. BSQD2407), Yunnan Provincial Department of Education Science Research Fund Project(No. 2025J0942).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yang Wang, Ruanjing Zhan and Feiyi Liu completed theoretical calculations together, and obtained all the results of the manuscript. Yang Wang and Feiyi Liu co-wrote the manuscript. Feiyi Liu supervised the completion of this paper and all the revisions. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Zhang, R. & Liu, F. A functional integral approach to magnon mediated plasmon friction. Sci Rep 15, 2019 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85666-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85666-z