Abstract

In complex sensory environments, visual cross-modal conflicts often affect auditory performance. The inferior parietal cortex (IPC) is involved in processing visual conflicts, namely when cognitive control processes such as inhibitory control and working memory are required. This study investigated the effect of bilateral IPC tRNS on reducing visual cross-modal conflicts and explored whether its efficacy is dependent on the conflict type. Forty-four young adults were randomly allocated to receive either active tRNS (100–640 Hz, 2-mA for 20 min) or sham stimulation. Participants repeatedly performed tasks in three phases: before, during, and after stimulation. Results showed that tRNS significantly enhanced task accuracy across both semantic and non-semantic conflicts compared to sham, as well as a greater benefit in semantic conflict after stimulation. Correlation analyses indicated that individuals with lower baseline performance benefited more from active tRNS during stimulation in the non-semantic conflict task. There were no significant differences between groups in reaction time for each conflict type task. These findings provide important evidence for the use of tRNS in reducing visual cross-modal conflicts, particularly in suppressing semantic distractors, and highlight the critical role of bilateral IPC in modulating visual cross-modal conflicts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In daily life, we often encounter environments rich with both visual and auditory stimuli. Audiovisual cross-modal conflicts occur when auditory and visual information do not match or contradict each other1. Although these conflicts are often mild, they significantly impact specific populations, such as the elderly and individuals with neurological impairments, affecting their daily life quality2. Audiovisual cross-modal conflicts manifest in two types: visual cross-modal conflicts (auditory targets with visual distractors), and auditory cross-modal conflicts (visual targets with auditory distractors). To effectively resolve conflicts, the top-down processes of cognitive control help us inhibit irrelevant stimuli (i.e., inhibitory control) while maintaining the relevant information (i.e., working memory, WM)3.

An asymmetrical behavioral performance has been reported between visual and auditory cross-modal conflicts4,5. Visual cross-modal conflicts tend to impair auditory task performance more significantly than vice versa5,6. The different filtering mechanisms in each modality, as well as the strong modality bias of the visual, may explain the asymmetrical interference effect of the distractors6.

Neuroimaging studies have reported the crucial role of frontoparietal cortex activation in inhibiting interference during cognitive tasks7,8. Most of them emphasize the prefrontal regions9,10,11, particularly the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, while the parietal region has been relatively understudied despite evidence suggesting inferior parietal cortex (IPC) activity as the critical neural bases underlying inhibiting interference6,12. Some evidence suggests that the primary contribution of the IPC is associated with WM storage7,14,15. Prefrontal regions play an important role in top-down control processing2,6, which supports active information storage in the IPC and contributes to inhibiting interference from sensory representations7,15. On the other hand, the role of IPC has also been related to inhibiting irrelevant information16,17,18. Investigations involving both healthy individuals19 and clinical populations20 have illustrated that the inhibition or impairment of either the left or right IPC leads to poorer task performance in inhibiting visual distractors.

Our earlier research has shown increased bilateral IPC activation during an auditory WM task with semantic visual distractors6. Notably, changes in IPC activation (i.e., the difference between the no-distractor and distractor conditions) were positively correlated with changes in task performance improvements. Similarly, a functional near-infrared spectroscopy study implicated activation of the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex in non-semantic visual cross-modal conflict processing, and the changes in bilateral IPC activation were also linked with inhibition of semantic and non-semantic distractors12. These findings suggest that the IPC and prefrontal cortex have equally important roles in reducing cross-modal conflicts, with increased IPC excitability closely associated with inhibiting the interference effect of visual cross-modal distractors.

Transcranial electrical stimulation (tES), including techniques like transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS), is a promising tool for understanding the role of various cortical areas and enhancing cognitive functions21,22. Some meta-analysis reviews have reported the effects of tDCS and tACS on improving working memory and inhibitory control performance, but the effect sizes are small23,24. Meanwhile, its application has mainly targeted prefrontal regions, neglecting the potential benefits of parietal stimulation.

Transcranial random noise stimulation (tRNS), a relatively new tES technique, is rapidly gaining popularity25. It delivers alternating currents with constantly changing polarity at random frequencies, often described as “white noise” due to its constant power spectral density across the specified frequency range. The signal is drawn from a Gaussian distribution with a mean current of zero. It can modulate brain excitability by using an alternating current randomly selected from a predefined range of intensities, notably effective in high-frequency tRNS (hf-tRNS) from 100 to 640 Hz26. Despite the fact that the mechanisms underlying tRNS remain incompletely understood, some studies have reported that tRNS can induce significant and dependable neuromodulatory effects on neural plasticity and behavioral outcomes25,27. There are two primary proposed mechanisms for tRNS. One mechanism enhances brain activity through stochastic resonance, which raises neural firing thresholds and increases neuronal responsiveness to stimuli28. The other mechanism shortens the hyperpolarization phase by prolonging the opening time of voltage-gated sodium channels, thereby altering neuronal excitability and firing patterns29. By modulating neuronal excitability in the IPC, a key region involved in inhibiting cross-modal conflicts, tRNS may enhance the suppression of irrelevant stimuli, thereby facilitating more efficient conflict resolution. Since the first tRNS study described its effect on the motor cortex, it has demonstrated effectiveness in many areas, such as perception30, learning31, and higher cognitive function25. Compared to other forms of tES, tRNS may generate more intense effects on behavior and longer-lasting performance improvements30. In addition, the polarity-independent characteristic of tRNS allows it to use both electrodes to simultaneously stimulate different cortical areas32. Furthermore, its advantages, such as less pain and greater tolerance, contribute to the successful blinding of participants in studies30,32. Despite promising research results, its effectiveness in modulating higher cognitive processes is variable (e.g., reported positive effects in working memory33, inhibitory control34, and attention35, as well as null effects36,37) and further exploration is necessary. To our best knowledge, none of the previous tES studies targeting the bilateral IPC have examined its role in visual cross-modal conflict tasks.

In summary, this is the first study to select the bilateral IPC as the stimulation brain area to explore the effect of hf-tRNS in semantic and non-semantic visual cross-modal conflicts. This contributes to the effective use of this technique for clinical applications and a better understanding of the specific contribution of IPC in reducing visual cross-modal conflicts. In this study, we chose the paced auditory serial addition test (PASAT) as the auditory target task, with the single digit as the semantic visual distractor and the WAIS-III Digit Symbol-Coding as the non-semantic visual distractor6,12. This allowed us to evaluate bilateral IPC activity and classify the conflict type based on the distractors (digits or symbols) in the task. Based on previous studies, we hypothesized that active tRNS might improve task performance both during and after stimulation, with potentially greater benefit in semantic conflicts.

Results

Participants performed the visual cross-modal conflict tasks with two conflict types (semantic and non-semantic) across three phases (baseline, online, and offline), and were randomly assigned to either the tRNS or sham group.

Demographic characteristics of active tRNS and sham groups

Four participants were excluded from the analysis due to incomplete participation or problems with task performance. The final sample comprised 40 young participants, 20 in the tRNS group (mean age = 23.80 years, SD = 1.58) and 20 in the sham group (mean age = 23.05 years, SD = 0.95). Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics and shows no significant differences between the tRNS and sham groups in age, gender, Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (EHI) scores, Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) scores, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-Y) scores, or WM ability. Additionally, participants maintained a focused gaze on visual distractors during tasks, with an average fixation ratio of 91.45%.

Visual cross-modal conflict task

Accuracy Table 2 shows the average task performance, including accuracy (percentage of correct responses) and reaction time (RT), for each conflict type at all assessment phases in both groups. No significant differences in baseline accuracy or RT were found between the tRNS and sham groups across each task (p > 0.05). Significant main effects of time were observed, with increased accuracy during both the online (β = 0.22, CI = [0.04, 0.41], p = 0.018) and offline phases (β = 0.35, CI = [0.16, 0.54], p < 0.001). The interaction between group and time revealed significantly greater accuracy improvements in the tRNS group compared to sham during the online (β = 0.36, CI = [0.10, 0.63], p = 0.005) and offline phases (β = 0.39, CI = [0.12, 0.66], p = 0.003). Post-hoc analyses indicated significant increases in accuracy from baseline to online in both the semantic conflict task (β = -0.39, CI [-0.78, -0.00], corrected p = 0.042) and the non-semantic conflict task (β = -0.42, CI [-0.81, -0.02], corrected p = 0.033) (see Fig. 1a; Table 3). Furthermore, there was a significant increase in accuracy from baseline to offline, with a larger improvement observed in the semantic conflict task (β = -0.66, CI [-1.06, -0.25], corrected p < 0.001) compared to the non-semantic conflict task (β = -0.44, CI [-0.84, -0.04], corrected p = 0.023). Regarding group comparison, the tRNS group revealed significantly higher accuracy than the sham group during the offline phase of the semantic conflict task (β = -0.66, CI [-1.21, -0.10], corrected p = 0.020), with no significant differences observed in other phases or for the non-semantic conflict task (all corrected p ≥ 0.186).

Behavioral results. (a) Accuracy as percentage of correct responses and (b) mean reaction time for PASAT with non-semantic and with semantic distractor task, including post-hoc tests with emmeans. Error bars indicate confidence intervals. Significance indicates (*) = p < 0.05, (**) = p < 0.01, (***) = p < 0.001.

RT Significant reductions in RT were observed during both online (β = -70.84, CI = [-91.42, -50.25], p < 0.001) and offline phases (β = -120.98, CI = [-156.01, -84.74], p < 0.001). The semantic conflict task showed longer RTs compared to the non-semantic conflict task (β = 46.49, CI = [36.79, 56.20], p < 0.001), indicating higher cognitive demands for semantic conflict. The interaction between group and time revealed significant RT reductions across the entire task in the tRNS group compared to sham during the online (β = 29.21, CI = [6.99, 51.41], p = 0.010) and offline phases (β = 62.54, CI = [-2.39, 45.17], p = 0.001). Additionally, the interaction among group, time, and conflict type showed a significant effect during the online phase compared to baseline (β = 28.42, CI = [2.67, 54.13], p = 0.030), suggesting differential effects of tRNS on non-semantic versus semantic conflict tasks in the online phase. Post-hoc tests indicated significant improvements across all three assessment phases in both groups (Offline > Online > Baseline, all corrected p < 0.01), except for the comparison between offline and online phases in the tRNS group (β = -25.30, CI = [-58.37, 7.80], corrected p = 0.200), indicating a gradual improvement in RT over time, and the online effect of tRNS may have sped up the improvement of non-semantic conflict so that it reached the offline level faster (see Fig. 1b; Table 3). However, there were no significant group differences in all assessment phases for both tasks (all corrected p ≥ 0.089), suggesting that the interaction between group and time was largely influenced by overall time-related improvements rather than by specific group differences.

Relationship between task performance at baseline and changes in each evaluation period in both groups

Significant negative correlations were observed between baseline accuracy and changes only in the online phase of the non-semantic conflict task for the tRNS group (r = -0.46, corrected p = 0.033) (Fig. 2). No significant correlations were found for the offline phase of the non-semantic conflict task, nor for any phase of the semantic conflict task in the tRNS group (all corrected p > 0.05). Similarly, no significant correlations were observed in either phase for either task in the sham group (all corrected p > 0.05).

Adverse effects and blinding

None of the participants reported significant adverse effects. Perception of stimulation did not significantly differ between the tRNS and sham groups (see Table 4). In the blinding assessment, 35.0% of participants in the tRNS group guessed they received real stimulation, 45.0% guessed placebo, and 20.0% were uncertain. In the sham group, 40.0% guessed received real stimulation, 40.0% guessed placebo, and 20.0% were uncertain. There was no significant difference in guessing between the sham and tRNS groups (χ2 = 0.18, p = 0.744).

Discussion

This study investigated the effect of a single-session tRNS over the bilateral IPC on visual cross-modal conflicts involving semantic and non-semantic conflict types, assessed at online and offline phases. Our results confirmed our hypothesis that tRNS significantly enhances task performance in both types of visual conflicts, highlighting its effectiveness in modulating cognitive processes related to cross-modal conflicts. Namely, the tRNS effect improved task accuracy during both online and offline phases, contrasting with no significant changes observed in the placebo condition. Furthermore, in the offline phase, the tRNS group showed a significant and larger task accuracy increase in the semantic conflict task compared to the non-semantic conflict task and the sham group. A gradual decrease in RT in both groups was observed, with no significant group differences. Additionally, correlations between baseline accuracy and changes in both online and offline phases for both conflict tasks were only found in the tRNS group but not in sham. These findings suggest that tRNS over the IPC enhances cognitive processes involved in resolving cross-modal conflicts, with a particular effect on improving task accuracy, especially in the semantic conflict task.

Our results extend previous studies by demonstrating the effect of tRNS on reducing cross-modal conflict, with increased accuracy during the online and offline phases of both conflict tasks, highlighting its common effect in processing visual conflicts. This improvement likely results from tRNS modulating IPC excitability to enhance inhibitory control, helping to suppress irrelevant distractors. The IPC plays a critical role in resolving cross-modal conflicts, with its activation linked to better inhibition of visual distractors6,12. Previous research has demonstrated that tRNS can enhance performance in tasks requiring visual discrimination11, attention38, and WM33. Compared to tDCS, tRNS is more effective and reliable for enhancing WM performance in healthy individuals33 and in people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder39. Shalev et al.35 further demonstrated that hf-tRNS over bilateral posterior parietal cortices enhanced selectivity in visual attentional processing and improved individuals’ ability to prioritize targets over visual distractors. Similarly, Contò et al.28 reported a significant improvement in the suppression of task irrelevant visual information and facilitated learning of the trained visual task after hf tRNS over bilateral parietal cortices. Our findings are consistent with these studies33,40,41,42, confirm that effective modulation of the parietal cortex can significantly improve task performance during conflicts40,43, particularly in the inhibition of cross-modal distractors6,12. On the other hand, sensory processing of task-relevant information may also be enhanced by tRNS, as proposed by the stochastic resonance hypothesis44. This suggests that tRNS enhances the signal-to-noise ratio, improving the quality of sensory processing of relevant information, which allows participants to better prioritize stimuli and filter out distractors, ultimately leading to better performance on conflict tasks. Thus, the observed improvement in task performance across both conflict tasks likely reflects a combination of enhanced inhibitory control and improved sensory processing of relevant stimuli.

In the online and offline phases, the post-hoc tests revealed that active tRNS significantly improved task accuracy in both conflict tasks. This is consistent with the literature indicating the tRNS effect on improving inhibitory control and WM41, as well as studies targeting the parietal cortex35,40 and its role in cross-modal conflict processing6. A meta-analysis of tRNS42 synthesized evidence from behavioral and physiological studies, suggesting that tRNS produces both online and offline effects that enhance neural processing during and after stimulation, respectively. Although the exact mechanism by which tRNS affects neural structures is unknown, the observed online benefits are likely driven by an increase in the signal-to-noise ratio within the IPC44. Meanwhile, long-lasting effects may arise from the modulation of neuronal excitability by voltage-gated sodium channels, resulting in changes similar to long-term potentiation. Our results suggest that tRNS effectively promoted spontaneous neuronal firing and long-term potentiation in the bilateral IPC, resulting in enhanced processing of visual cross-modal conflicts, with sustained improvements observed in the offline phase. Moreover, we observed a larger improvement in the accuracy of the semantic conflict task after active tRNS compared to the non-semantic conflict task. These results indicate the critical role of the target position in optimizing tRNS efficacy. As mentioned above, bilateral IPC activation increased during the inhibition of visual semantic cross-modal distractors6, while the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activated when visual non-semantic cross-modal distractors were inhibited12. Our results are in agreement with the idea that bilateral IPC modulation has a larger impact on inhibiting semantic conflicts. Additionally, compared to the sham group, tRNS produced a significant improvement in the semantic conflict task during the offline phase, further emphasizing its specific effect on inhibiting semantic conflict. This is also in line with the stochastic resonance theory, which suggests that tRNS may have a stronger effect on more difficult tasks, such as the semantic conflict task28,44.

The negative correlation between baseline accuracy and performance changes in the online phase of the non-semantic conflict task within the tRNS group suggests that individuals with lower initial performance levels may benefit more from tRNS, likely due to an enhanced signal-to-noise ratio in neural processing44. This is consistent with previous findings of tRNS over the inferior frontal cortex in an emotion perception task45, indicating inter-individual variability in the tRNS effect25. Interestingly, no significant correlations were found for either the semantic conflict or the offline phase of the non-semantic conflict task, indicating that tRNS effects are task-specific and timing-dependent. Moreover, no significant correlations were found in the sham group, further highlighting the effectiveness of tRNS in enhancing performance in visual cross-modal conflict and supports its role as a targeted intervention for cognitive enhancement. These results suggest the need to consider baseline cognitive capacity and task characteristics when designing tRNS interventions for cognitive enhancement.

On the other hand, previous studies have presented contrasting findings regarding the efficacy of tRNS in inhibition36,37. For instance, Brauer et al. found no significant effect of tRNS over the right inferior frontal gyrus at 1 mA with a full frequency range (0.1–640 Hz) for 30 min36, while Sallard et al. similarly reported null effects of hf-tRNS over the bilateral inferior frontal gyrus at 1 mA for 10 min37. These results may arise from variations in stimulation protocols, such as frequency range, target position, current intensity, and duration. In this study, we employed hf-tRNS, contrasting with Brauer et al.‘s use of full-frequency tRNS. While the exact mechanisms by which high-frequency stimulation affects neural structures remain unclear, there is growing evidence in the literature that high-frequency stimulation can effectively modulate neuronal activity and induce clinically meaningful effects in humans26,41. Regarding the target position, unlike the prefrontal regions chosen for their studies, our study selected bilateral IPC6,12. A study using magnetic resonance spectroscopy found a link between parietal GABA and the inhibition of task irrelevant information46, suggesting that tRNS modulation of the parietal cortex may influence the inhibition of distractors. Furthermore, their protocol’s lower current intensity or shorter stimulus duration indicate that stronger and longer stimulation may be required to modulate neuronal excitability and improve cognitive performance effectively47. These differences in stimulation parameters highlight the need to adapt tRNS protocols to specific cognitive tasks. Targeting the IPC with high-frequency stimulation, a crucial region involved in cross-modal conflict resolution, could explain the robust effects observed in this study.

In addition, both the tRNS and sham groups showed a gradual decrease in RT throughout the experiment, likely attributable to the learning effect of repeated task performance. However, this improvement was confined to RT and did not influence accuracy, as evidenced by the similar performance of the sham group across all phases. Interestingly, there was no significant improvement in non-semantic conflicts from offline to online, possibly due to the online tRNS effect, which accelerates RT improvement to the offline level. Meanwhile, no significant difference in RT was found between the tRNS and sham groups, suggesting that the current tRNS protocol did not directly impact processing speed. Instead, tRNS seemed to facilitate accuracy-driven improvements. Since participants were instructed to prioritize accuracy over speed, this may explain why the tRNS effect was more evident in accuracy than RT.

Despite the promising results, this study has several limitations. First, the sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, although we controlled for baseline characteristics (e.g., age, cognitive abilities), residual group differences may still influence the results. Third, the lack of a no-distractor control condition (e.g., PASAT) makes it difficult to isolate the specific effects of tRNS on conflict inhibition. Additionally, participants’ relatively high baseline accuracy (around 90%) may have caused a ceiling effect, limiting the observed improvements. Finally, although the highest electric-field strength was estimated to be in the IPC, stimulation may have also affected nearby regions, and the potential influence of these adjacent areas on the results cannot be fully ruled out.

Conclusions

Taken together, our study provided behavioral evidence demonstrating that hf-tRNS over the bilateral IPC enhances task accuracy during visual cross-modal conflict tasks, particularly for semantic conflict. Correlation analyses showed a greater benefit for individuals with lower baseline performance in the online phase of the non-semantic conflict task, suggesting that tRNS efficacy may vary depending on baseline cognitive capacity and task characteristics. These findings contribute to a deeper comprehension of the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying bilateral parietal cortex involvement in such processes. Importantly, they advance our understanding of hf-tRNS as a potential therapeutic tool for improving cognitive functions. This work paves the way for future studies to investigate how tRNS impacts the neurophysiological features of each cross-modal conflict, as well as what differences and correlations exist between these features and behavioral performance using EEG techniques. Future research should be replicated with larger healthy and clinical populations, including control and more challenging task conditions, to isolate the specific effects of tRNS on conflict inhibition. Investigating the optimal stimulation parameters and long-term effects of tRNS will be key to understanding its clinical potential in cognitive rehabilitation and enhancement.

Methods

Participants

Forty-four young, healthy volunteers (22 males and 22 females), aged 21 to 25 years, participated in this study. The sample size exceeded the minimum requirement of 28 participants for achieving 95% power, with a significance level of 0.05, based on a medium effect size of 0.25 calculated using G*power. All participants were right-handed (EHI ≥ 80 points48), had normal vision and auditory abilities, and had no history of neurological or psychiatric disorders. Prior to inclusion, participants were assessed for current psychopathology using two psychological self-assessment scales (BDI and STAI-Y)49,50,51. A safety questionnaire for stimulation contraindications was also administered to assess participants’ adverse effects, safety, and tolerability52.

The Biological and Medical Ethics Committee of Dalian University of Technology approved the experimental protocol (approval number: DUTSFL230905-01), and all participants provided informed consent prior to their participation in the study. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Procedure

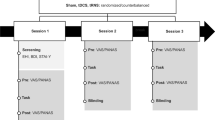

A double-blind, sham-controlled, parallel-group design was employed, randomly assigning participants to receive either active tRNS or sham stimulation (see Fig. 3). Randomization was based on age, gender, and WM ability assessed using (1) the forward and backward Corsi block tapping task, a measure of spatial WM capacity53, and (2) the forward and backward digit-span tasks, a measure of verbal WM capacity54. Cognitive assessments were conducted by a trained researcher.

Participants completed a practice session to minimize learning effects before the main experiment47. The experiment consisted of three phases: baseline (i.e., before stimulation), online (i.e., during stimulation), and offline (i.e., after stimulation) (see Fig. 1). Eye tracking (Portable Duo, Eyelink, Canada) was used to monitor fixation on visual distractors throughout the task. Finally, a sensation questionnaire about the success of blinding and discomfort from tRNS was measured for the participants.

Experimental task

We used the PASAT as the auditory target task based on our previous findings6,12. PASAT is an important and complex working memory test that requires high cognitive demands on multiple cognitive domains (i.e., attention, working memory, and information processing speed)55. Participants were randomly given a single digit ranging from 1 to 9. They were asked to add the current digit to the previous digit and respond correctly during inter-stimulus intervals. For visual distractors, we used the single digit as the semantic visual distractor and the WAIS-III Digit Symbol-Coding as the non-semantic visual distractor. The experimental task was programmed using E-Prime software (version 3.0). It included two conflict-type tasks: PASAT with semantic visual distractor (i.e., semantic conflict task) and PASAT with non-semantic visual distractor (i.e., non-semantic conflict task) (see Fig. 4). A block design was used, in which a 60 s task (semantic conflict task or non-semantic conflict task) was interleaved with a 30 s rest period. Each stimulus lasted 500 ms, followed by a 1500 ms inter-stimulus interval, with 29 responses required per block. Before, during, and after stimulation, each participant completed 6 blocks, with three randomized repetitions of the two task types, for a total of 18 blocks. To minimize potential learning effects, different versions of the tasks were used for each repetition. The primary outcomes were task accuracy and RT.

Transcranial stimulation protocol

The stimulation was delivered using a DC-Stimulator Plus (neuroConn, Ilmenau, Germany) via a pair of saline-soaked electrodes (5 cm × 7 cm, 0.9% NaCl) placed over the left and right IPC (P3 and P4) in accordance with the international 10–20 system (see Fig. 5). The tRNS group received 2-mA peak-to-peak hf-tRNS (100–640 Hz) for 20 min, using the “noise HF” mode, which generates random, normally distributed current levels at a sampling rate of 1280 samples/s. The resulting maximum current density was approximately 0.029 mA/cm2. The electric field distribution was modeled in SimNIBS (Version 4.0.1) to represent the peak intensity of the tRNS protocol, as shown in Fig. 5b. In the sham condition, no current was delivered for 20 min except during the first 60 s (with a 30 s ramp-up and -down) to keep participants blind to the condition56. The electrode impedances were kept below 5 kΩ during the stimulation.

Electrode placement and electric field distribution after stimulation. (a) Stimulation sites were localized using EEG 10/20 system. Saline-soaked electrodes were placed over P3 and P4 for bilateral parietal and sham stimulation. (b) Electric field distribution on the brain induced by parietal stimulation, modeled with SimNIBS (Version 4.0.1) software at peak intensity.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were done in R software (version 4.4.1). Baseline characteristics, WM ability, and sensation questionnaire results were analyzed using t-tests or chi-square tests.

Task performance was analyzed using the lme4 package. Namely, accuracy was analyzed using the function glmer, and RT was estimated using the function lmer. The p-values were computed with the lmerTest package. Group (sham or tRNS), time (baseline, online, and offline), conflict-type (semantic and non-semantic), and their interactions were included as fixed effects. Participant ID and trial numbers were included as random effects. Model fit was assessed using the Akaike Information Criterion. Post-hoc analyses were conducted using the emmeans package with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Correlation analyses examined relationships between accuracy (percentage of correct responses) at baseline and changes in each phase (offline–baseline and online–baseline) using Pearson’s product-moment correlation, with a statistical correction method suggested by Tu57. The results were considered significant at p < 0.05 (95% confidence interval).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- tRNS:

-

Transcranial random noise stimulation

- IPC:

-

Inferior parietal cortex

- tES:

-

Transcranial electrical stimulation

- tDCS:

-

Transcranial direct current stimulation

- tACS:

-

Transcranial alternating current stimulation

- hf-tRNS:

-

High-frequency tRNS

- EHI:

-

Edinburgh Handedness Inventory

- BDI:

-

Beck Depression Inventory

- STAI-Y:

-

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

- WM:

-

Working memory

- PASAT:

-

Paced auditory serial addition test

- RT:

-

Reaction time

References

Forster, S. & Lavie, N. Failures to ignore entirely irrelevant distractors: The role of load. J. Exp. Psychol. 14, 73–83 (2008).

Rienäcker, F. et al. The neural correlates of visual and auditory cross-modal selective attention in aging. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12, 1–11 (2020).

Hung, Y., Gaillard, S. L., Yarmak, P. & Arsalidou, M. Dissociations of cognitive inhibition, response inhibition, and emotional interference: Voxelwise ale meta-analyses of fMRI studies. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 39, 4065–4082 (2018).

Guerreiro, M. J. S. & Van Gerven, P. W. M. Now you see it, now you don’t: Evidence for age-dependent and age-independent cross-modal distraction. Psychol. Aging 26, 415–426 (2011).

Fu, D. et al. What can computational models learn from human selective attention? A review from an audiovisual unimodal and crossmodal perspective. Front. Integr. Nuerosci. 14, 10 (2020).

Cui, J. et al. Effect of audiovisual cross-modal conflict during working memory tasks: A near-infrared spectroscopy study. Brain Sci. 12, 1–17 (2022).

Dolcos, F., Miller, B., Kragel, P., Jha, A. & McCarthy, G. Regional brain differences in the effect of distraction during the delay interval of a working memory task. Brain Res. 1152, 171–181 (2007).

Rees, G., Frith, C. & Lavie, N. Processing of irrelevant visual motion during performance of an auditory attention task. Neuropsychologia 39, 937–949 (2001).

Van Gerven Pascal, W. M. & Guerreiro Maria, J. S. Selective attention and sensory modality in aging: Curses and blessings. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10, 147. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00147 (2016).

Calvert, G. A. Crossmodal processing in the human brain: Insights from functional neuroimaging studies. Cereb. Cortex 11, 1110–1123 (2001).

Tommasi, G. et al. Disentangling the role of cortico-basal ganglia loops in top–down and bottom–up visual attention: An investigation of attention deficits in parkinson disease. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 27, 1215–1237 (2015).

Sawamura, D. et al. The impact of visual cross-modal conflict with semantic and nonsemantic distractors on working memory task: A functional near-infrared spectroscopy study. Medicine 101, e30330. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000030330 (2022).

Todd, J. J. & Marois, R. Capacity limit of visual short-term memory in human posterior parietal cortex. Nature 428, 751–754 (2004).

Todd, J. J. & Marois, R. Posterior parietal cortex activity predicts individual differences in visual short-term memory capacity. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 5, 144–155 (2005).

Chikara, R. K. & Ko, L. W. Neural activities classification of human inhibitory control using hierarchical model. Sens. (Switzerland) 19, 1–18 (2019).

Corbetta, M. & Shulman, G. L. Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 201–215 (2002).

Gazzaley, A. & Nobre, A. C. Top-down modulation: bridging selective attention and working memory. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16, 129–135 (2012).

Hughes, M. E. et al. Sustained brain activation supporting stop-signal task performance. Eur. J. Neurosci. 39, 1363–1369 (2014).

Mevorach, C., Allen, H., Hodsoll, J., Shalev, L. & Humphreys, G. Interactivity between the left intraparietal sulcus and occipital cortex in ignoring salient distractors: Evidence from neuropsychological fMRI. J. Vis. 10, 89–89 (2010).

Friedman-Hill, S. R., Robertson, L. C., Desimone, R. & Ungerleider, L. G. Posterior parietal cortex and the filtering of distractors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100(7), 4263–4268 (2003).

Al Qasem, W., Abubaker, M. & Kvašňák, E. Working memory and transcranial-alternating current stimulation-state of the art: Findings, missing, and challenges. Front. Psychol. 13, 822545. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.822545 (2022).

Dedoncker, J., Brunoni, A. R., Baeken, C. & Vanderhasselt, M. A. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in healthy and neuropsychiatric samples: Influence of stimulation parameters. Brain Stimul 9, 501–517 (2016).

Hill, A. T., Fitzgerald, P. B. & Hoy, K. E. Effects of anodal transcranial direct current stimulation on working memory: A systematic review and meta-analysis of findings from healthy and neuropsychiatric populations. Brain Stimul 9, 197–208 (2015).

Schroeder, P. A., Schwippel, T., Wolz, I. & Svaldi, J. Meta-analysis of the effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on inhibitory control. Brain Stimul 13, 1159–1167 (2020).

Groen, O. et al. Using noise for the better: The effects of transcranial random noise stimulation on the brain and behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav Rev. 138, 104702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104702 (2022).

Harty, S. & Cohen Kadosh, R. Suboptimal engagement of high-level cortical regions predicts random-noise-related gains in sustained attention. Psychol. Sci. 30, 1318–1332 (2019).

Inukai, Y. et al. Comparison of three non-invasive transcranial electrical stimulation methods for increasing cortical excitability. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 10, 668. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2016.00668 (2016).

Contò, F. et al. Attention network modulation via tRNS correlates with attention gain. eLife 10, e63782. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.63782 (2021).

Peña, J. et al. Comparing transcranial direct current stimulation and transcranial random noise stimulation over left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and left inferior frontal gyrus: Effects on divergent and convergent thinking. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 16, 997445. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.997445 (2022).

Terney, D., Chaieb, L., Moliadze, V., Antal, A. & Paulus, W. Increasing human brain excitability by transcranial high-frequency random noise stimulation. J. Neurosci. 28, 14147–14155 (2008).

Contemori, G., Trotter, Y., Cottereau, B. R. & Maniglia, M. tRNS boosts perceptual learning in peripheral vision. Neuropsychologia 125, 129–136 (2019).

Ambrus, G. G., Paulus, W. & Antal, A. Cutaneous perception thresholds of electrical stimulation methods: Comparison of tDCS and tRNS. Clin. Neurophysiol. 121, 1908–1914 (2010).

Murphy, O. W. et al. Transcranial random noise stimulation is more effective than transcranial direct current stimulation for enhancing working memory in healthy individuals: Behavioural and electrophysiological evidence. Brain Stimul. 13, 1370–1380 (2020).

Brevet-Aeby, C., Mondino, M., Poulet, E. & Brunelin, J. Three repeated sessions of transcranial random noise stimulation (tRNS) leads to long-term effects on reaction time in the Go/No go task. Neurophysiol. Clin. 49, 27–32 (2019).

Shalev, N., De Wandel, L., Dockree, P., Demeyere, N. & Chechlacz, M. Beyond time and space: The effect of a lateralized sustained attention task and brain stimulation on spatial and selective attention. Cortex 107, 131–147 (2017).

Brauer, H., Kadish, N. E., Pedersen, A., Siniatchkin, M. & Moliadze, V. No modulatory effects when stimulating the right inferior frontal gyrus with continuous 6Hz TACs and TRNs on response inhibition: A behavioral study. Neural Plast e3156796; (2018). https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/3156796 (2018).

Sallard, E., Buch, E. R., Cohen, L. G. & Quentin, R. No evidence of improvements in inhibitory control with tRNS. Neuroimage: Rep. 1, 100056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynirp.2021.100056 (2021).

Tyler, S., Cont` o, F. & Battelli, L. Rapid effect of high-frequency tRNS over the parietal lobe during a temporal perceptual learning task. J. Vis. 15, 393 (2015).

Berger, I., Dakwar-Kawar, O., Grossman, E. S. & Nahum, M. Cohen Kadosh, R. Scaffolding the attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder brain using transcranial direct current and random noise stimulation: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Neurophysiol. 132, 699–707 (2021).

Contò, F., Tyler, S., Paletta, P. & Battelli, L. The role of the parietal lobe in task-irrelevant suppression during learning. Brain Stimul 16, 715–723 (2023).

van der Groen, O. et al. Using noise for the better: The effects of transcranial random noise stimulation on the brain and behavior. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 138, 104702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104702 (2022).

Potok, W., Van Der Groen, O., Bächinger, M., Edwards, D. & Wenderoth, N. Transcranial random noise stimulation modulates neural processing of sensory and motor circuits, from potential cellular mechanisms to behavior: A scoping review. Eneuro 9, 0248-21.; (2021). https://doi.org/10.1523/ENEURO.0248-21.2021 (2022).

Sdoia, S., Zivi, P. & Ferlazzo, F. Anodal tDCS over the right parietal but not frontal cortex enhances the ability to overcome task set inhibition during task switching. PLoS ONE 15, e0228541. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228541 (2020).

van der Groen, O., Tang, M. F., Wenderoth, N. & Mattingley, J. B. Stochastic resonance enhances the rate of evidence accumulation during combined brain stimulation and perceptual decision-making. PLoS Comput. Biol. 14, e1006301 (2018).

Penton, T., Dixon, L., Evans, L. J. & Banissy, M. J. Emotion perception improvement following high frequency transcranial random noise stimulation of the inferior frontal cortex. Sci. Rep. 7, 11278 (2017).

Frangou, P. et al. Learning to optimize perceptual decisions through suppressive interactions in the human brain. Nat. Commun. 10, 474 (2019).

Sherman, E. M. S., Strauss, E. & Spellacy, F. Validity of the paced auditory serial addition test (pasat) in adults referred for neuropsychological assessment after head injury. Clin. Neuropsychologist 11, 34–45 (1997).

Oldfield, R. C. The assessment and analysis of handedness: The Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 9, 97–113 (1971).

Beck, A. T., Ward, C. H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J. & Erbaugh, J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 4, 561–571 (1969).

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, R., Vagg, P. R. & Jacobs, G. A. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (form Y). Mind Garden (1983).

Spielberger, C. State-trait anxiety inventory for adults. Garden (2008).

Fertonani, A., Ferrari, C. & Miniussi, C. What do you feel if I apply transcranial electric stimulation? Safety, sensations and secondary induced effects. Clin. Neurophysiol. 126, 2181–2188 (2015).

Arce, T. & McMullen, K. The corsi block-tapping test: evaluating methodological practices with an eye towards modern digital frameworks. Computers Hum. Behav. Rep. 4, 100099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100099 (2021).

Wechsler, D. Manual for the Wechsler adult intelligence scale. Psychol. Corporation (1955).

Tombaugh, T. N. A comprehensive review of the Paced Auditory serial addition test (PASAT). Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 21, 53–76 (2006).

Nitsche, M. A. et al. Pascual-Leone, A. Transcranial direct current stimulation: State of the art 2008. Brain Stimul. 1, 206–223 (2008).

Tu, Y. K. Testing the relation between percentage change and baseline value. Sci. Rep. 6, 23247 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We hereby acknowledge all participants for their contribution.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C., W.Y., L.H. conceptualized and designed the experiment. J.C. interpretation of data, writing of the original draft, and writing review and editing. W.Y. and L.H. analyzed the data and prepared figures. W.Y. and Z.L. acquired data and revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cui, J., Yu, W., Hu, L. et al. The effect of transcranial random noise stimulation (tRNS) over bilateral parietal cortex in visual cross-modal conflicts. Sci Rep 15, 4980 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85682-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85682-z