Abstract

In order to reduce the number of parameters in the Chinese herbal medicine recognition model while maintaining accuracy, this paper takes 20 classes of Chinese herbs as the research object and proposes a recognition network based on knowledge distillation and cross-attention – ShuffleCANet (ShuffleNet and Cross-Attention). Firstly, transfer learning was used for experiments on 20 classic networks, and DenseNet and RegNet were selected as dual teacher models. Then, considering the parameter count and recognition accuracy, ShuffleNet was determined as the student model, and a new cross-attention mechanism was proposed. This cross-attention model replaces Conv5 in ShuffleNet to achieve the goal of lightweight design while maintaining accuracy. Finally, experiments on the public dataset NB-TCM-CHM showed that the accuracy (ACC) and F1_score of the proposed ShuffleCANet model reached 98.8%, with only 128.66M model parameters. Compared with the baseline model ShuffleNet, the parameters are reduced by nearly 50%, but the accuracy is improved by about 1.3%, proving this method’s effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a non-invasive and low side-effect treatment method, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has held an important position in China’s medical system for thousands of years1, and is widely used in China and other Asian countries. As a carrier of traditional Chinese medicine treatment, Chinese herbal medicine has received widespread attention due to its important role in disease prevention, treatment, and daily health care. However, due to the large variety of Chinese herbal medicines and the differences between different classes, the identification and classification of these herbs largely rely on professionals such as doctors with specialized knowledge. Ordinary people mainly rely on image comparison for judgment, which can easily lead to errors and delays in disease treatment. Is there an effective Chinese herbal medicine recognition model that can achieve the effect shown in Fig. 1, allowing ordinary users to quickly and accurately identify the classes of Chinese herbal medicine like doctors or experts?

With the development of computer technology, especially the advancements in image processing and pattern recognition, the automation of Chinese herbal medicine recognition technology has become possible. Jia et al.2 identified Chinese herbal slices automatically by extracting six features, such as texture roughness, contrast, and orientation from the slice surface, using local texture details for classification. Cheng et al.3 processed colour images of five important herbal drinks, including rhubarb, using OpenCV (open-source computer vision library) with the help of a support vector machine classifier. Machine learning-based methods can automatically recognise Chinese herbs to a certain extent. Still, the recognition efficiency is not satisfactory due to the lack of high-level semantic information and susceptibility to environmental interference.

With the development of deep learning, especially Convolutional Neural Networks, which can extract features from low-level to high-level semantics, recognition accuracy in fields such as image classification and object recognition has been significantly improved. In 2018, Liu et al.4 designed a method for automatic recognition and classification of Chinese herbal medicine using image processing and deep learning, with GoogLeNet as the backbone network. In 2020, Huang et al.5 proposed a Chinese herbal medicine image classification method based on AlexNet. Xing et al.6 constructed a dataset containing 25,083 images of 80 classes of Chinese herbal slices and used DenseNet as the backbone network combined with the dropout method for recognition. Zhang et al.7 built a dataset and constructed a classification model with the VGG model as the backbone network for 17 unique Chinese herbal medicines in the Yellow River Delta region. In 2023, Yang et al.8 solves the problems of lack of data on traditional Chinese medicinal plants and low accuracy of image classification.

However, due to the large number of model parameters in classic convolutional neural networks, which makes them difficult to deploy on mobile devices, various lightweight networks such as the MobileNet series and ShuffleNet have emerged. In 2021, Wu et al.1 proposed a human-machine collaborative method for constructing a Chinese medicinal materials dataset, ultimately obtaining the human-machine collaboratively annotated dataset CH42, which contains 42 Chinese medicinal materials. Based on this, a backbone network, SeNet-18, was designed for Chinese medicinal material recognition. Hao et al.9 built a dataset for Chinese medicinal material classification (CHMC), including 100 classes, and used the EfficientNetB4 model as the backbone network for classification. In 2023, Hu et al.10 proposed a novel lightweight convolutional neural network, CCNNet, for Chinese herbal medicine recognition to achieve higher model accuracy with fewer parameters. This model compresses the CNN architecture with a ’bottleneck’ structure, obtains multi-scale features through downsampling, and enhances model performance using GCIR module stacking and MDCA attention mechanism. Miao et al.11 used an improved ConvNeXt network for feature extraction and classification of Chinese medicinal materials, achieving good recognition results. In 2024, Zheng et al.12 proposed a Chinese herbal medicine recognition method using a knowledge distillation model. It was implemented on the lightweight MobileNet_v3 network. Although there are many methods for Chinese herbal medicine recognition, most of them are analyzed on self-built datasets and existing public datasets can be used for comparative analysis. In 2024, Tian et al.13 built a dataset NB-TCM-CHM containing images of 20 common Chinese herbal medicines to address this issue.

In order to seek a balance between detection accuracy and the amount of model parameters, the cross-attention mechanism is widely used. The cross-attention mechanism14,15,16 can gradually optimize the attention weight distribution, improve the accuracy and resolution of feature extraction, and meet the comprehensive modelling needs of global semantics and local details of complex tasks, thereby improving the generalization and adaptability of the model. Therefore, it was introduced to solve the problem of large inter-class differences and small intra-class differences between images of different classes. Khader et al.14 proposed a novel Cascaded Cross-Attention Network (C-CAN) based on a cross-attention mechanism for efficient data classification of full-slide images. Chu et al.15 proposed a dual-coordinate cross-attention transformer (DCCAT) network that introduced a dual-coordinate cross-attention mechanism for automatic thrombus segmentation on coronary artery OCT images. Shen et al.16 proposed a novel double-cross attention feature fusion method for multispectral target detection. The complementary information of RGB and thermal infrared images is aggregated through the cross-attention mechanism to improve detection performance. Although many scholars have conducted in-depth research on Chinese herbal medicine image recognition, there is still room for improvement in model parameters and accuracy.

To address the aforementioned challenges, this paper proposes a Chinese herbal medicine recognition network based on knowledge distillation and cross-attention, named ShuffleCANet, aiming to reduce the number of model parameters while maintaining good recognition performance. Among them, the teacher model consists of DenseNet and RegNet, aiming to provide more knowledge to the student model with ShuffleNet as the backbone network. To enable the network to focus on more global and local information in the image during model training to improve recognition accuracy, this paper proposes a cross-attention mechanism and embeds it into the student model. The application of deep learning in the recognition and classification of Chinese herbal medicine also marks a key step in protecting and developing Traditional Chinese Medicine heritage.

The main contributions of this paper are:

-

1.

We propose a Chinese herbal medicine recognition model, ShuffleCANet, which achieves good recognition accuracy with a low parameters. Results on public datasets show that the proposed model achieves an accuracy of 98.8%, with only 128.66M model parameters. Compared with the baseline model ShuffleNet, the parameters are reduced by nearly 50%, but the accuracy is improved by about 1.3%.

-

2.

We propose a new cross-attention mechanism to enable the network to better focus on both global and local information in images during training. This addresses the issue of large inter-class and small intra-class differences among various classes of Chinese herbal medicine, thereby ensuring recognition accuracy.

Relate works

To effectively extract feature information from Chinese herbal medicine images and achieve automatic recognition, Liu et al.17 proposed a method for feature extraction and recognition of Chinese medicinal material images based on the grey-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM). First, based on obtaining colour CHM images, they are converted to grayscale images. The GLCM is then used to extract four texture feature parameters: angular second moment (ASM), inertia moment (IM), entropy, and correlation. These feature values are then used to resist geometric distortion for CHM image recognition. In 2021, Yu et al.18 used the grey-level co-occurrence matrix method to extract side texture features of medicinal materials. Combining the feature values of colour components in the HSV and colour space, they used a BP neural network for pattern recognition to identify rhizome-type Chinese medicinal materials.

With the development of Convolutional Neural Networks in 2016, Sun et al.19 proposed using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) for Chinese herbal medicine image recognition and added triplet loss to search for the most similar medicinal images. In 2019, Cai et al.20 proposed a Chinese herbal medicine recognition framework that combines ResNet with a Broad Learning System (BLS). In 2020, Huang et al.5 built a dataset containing five classes of Chinese herbal medicines by crawling Baidu images and, based on this dataset, proposed a Chinese herbal medicine image classification method based on the AlexNet model. Hu et al.21 drew on the concept of multi-task learning, using neural networks as the foundation and traditional features as a supplement, integrating the two to establish a new deep learning model, and collected 200 classes of Chinese herbal slices for Chinese herbal slice recognition. Wang et al.22 addressed the issue of low accuracy in the classification and recognition of Chinese herbal medicines during field practice in Changbai Mountain by using an ant colony optimization-based image segmentation algorithm to process the collected dataset. They proposed a deep encoding-decoding network to classify 15 Chinese herbal medicine image classes and solved the data scarcity problem through transfer learning. In 2021, Chen et al.23 designed a network architecture for high- and low-frequency feature learning. They used a parallel convolutional network to obtain low-frequency features and a multi-scale deep convolutional kernel to obtain high-frequency features. A semantic description network was utilized to achieve a feature learning model with generalization capabilities. Introducing the Wasserstein distance into the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) to complete the identification of herbal slices, thereby improving recognition accuracy. In 2022, Liu et al.24 proposed a method for classifying Chinese herbal plants based on image segmentation and deep learning using the GoogLeNet model to address the issues of numerous classes of Chinese medicinal materials, similar morphology, and complex backgrounds in dataset images. Qin et al.25 proposed an improved method based on the traditional Convolutional Neural Network (VGG). Firstly, this paper is not limited to the Conv-Batch Normalization (BN)-Max Pooling network structure model but adopts a three-layer (Conv-BN, Conv-Max Pooling, and Conv-BN-Max Pooling) interleaved network structure. Secondly, it uses GAP to connect the convolutional and fully connected layers (FC). In 2023, Huang et al.26 proposed the ResNet101 model, which combines SENet and ResNet101, adds a convolutional block attention module, and uses Bayesian optimization to classify Chinese herbal flowers.

Various lightweight models have emerged to meet the demand for deploying network models to mobile devices. In 2021, Tang et al.27 built a dataset containing 44,467 images of 160 classes of Chinese medicinal materials and used the ResNeXt-152 model as the backbone network for classification. Wu et al.1 proposed a human-machine collaborative method for constructing a Chinese medicinal materials dataset, resulting in the CH42 dataset, which includes 42 Chinese medicinal materials annotated through human-machine collaboration. Based on this, a backbone network, SeNet-18, was designed for Chinese medicinal material recognition. Xu et al.28 constructed a new standard Chinese medicinal materials dataset and proposed a novel Attention Pyramid Network (APN) that employs innovative competitive and spatial collaborative attention for the recognition of Chinese medicinal materials. In 2022, Han et al.29 proposed a Chinese medicinal materials classification method based on mutual learning. Specifically, two small student networks are designed to perform collaborative learning, each collecting knowledge learned from the other student network. The student networks thus acquire rich and reliable features, further enhancing the performance of Chinese medicinal materials classification. Hao et al.30 proposed a Chinese medicinal materials classification method based on Mutual Triple Attention Learning (MTAL), which utilizes a set of student networks to collaboratively learn throughout the training process, teaching each other cross-dimensional dependencies to obtain robust feature representations and improve results quickly. Wang et al.31 built a dataset containing 14,196 images and 182 common Chinese herbal medicine classes and proposed a Combined Channel and Spatial Attention Module Network (CCSM-Net) for effective recognition of Chinese herbal medicine in 2D images. Wu et al.32 addressed the issue of traditional Chinese medicine recognition, focusing more on the details of the recognition objects and proposed a model using spatial/channel attention mechanisms for image recognition, utilizing a dynamic adaptive mechanism to help the model balance global and detailed information. In 2024, Zhang et al.33 built a Chinese herbal medicine classification and recognition model, which was constructed using a residual neural network combined with a convolutional block attention module, and applied a fusion of local binary pattern features and transfer learning strategies to improve the model’s recognition accuracy. Li et al.34 used Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) to improve the recognition accuracy of Traditional Chinese Medicine images.

Although many methods are applied to Chinese herbal medicine recognition, most are based on self-built datasets for experiments, and there are few publicly available datasets. Tian et al.13 built a dataset (Dataset 1) containing 3,384 images of fruits from 20 common Chinese herbal medicines through web crawling to address this issue. Traditional Chinese Medicine experts annotated all images suitable for training and testing Chinese medicinal material identification methods. In addition, this study also established another dataset (Dataset 2) containing 400 images taken by smartphones, providing material for the practical efficacy evaluation of Chinese medicinal material identification methods.

Method

Basic principles of knowledge distillation

The knowledge distillation flowchart is shown in Fig. 2. Its basic idea is to train a teacher model that performs well on the target dataset, then distil the knowledge learned by the teacher model and transfer it to a student network with weaker feature representation capabilities. Through the transfer of knowledge, the training of the student model is guided, thereby improving the model’s performance. The essence of knowledge distillation lies in constructing a student model and then having it fit the distribution of the teacher model, enabling the small network to learn the knowledge of the large network. Knowledge distillation not only reduces the network size but also focuses on retaining the knowledge from the teacher network. In addition, the richness of the information contained in the teacher model in the knowledge distillation method will also affect the final training effect of the model. Theoretically, the richer the “dark knowledge” information of the teacher model, the more knowledge can be transferred to the student model, and the better the training effect of the student model.

Chinese herbal medicine recognition network based on knowledge distillation and cross-attention

To obtain a streamlined and efficient network model with low computational cost for Chinese herbal medicine recognition. This paper proposes a Chinese herbal medicine recognition network based on knowledge distillation and cross-attention. The general process of this method is as follows:

-

1.

Training and selection of the teacher model. Since the lightweight student model needs to acquire knowledge from the teacher model, the classification performance of the teacher model directly affects the classification performance of the lightweight student model. As shown in Fig. 3, this paper trains and tests multiple network models on the Chinese medicinal materials dataset using the deep transfer learning method of fine-tuning pre-trained networks, selecting the teacher model with excellent performance as the basis for subsequent lightweight model research.

After experimental analysis, DenseNet and RegNet networks were ultimately selected as teacher models (see the experimental section for details) to train the student model for higher accuracy. DenseNet breaks away from the conventional thinking of improving network performance by deepening (ResNet) and widening (Inception) network structures. Instead, it considers features, utilizing feature reuse and bypass settings to significantly reduce the number of network parameters and alleviate the gradient vanishing problem to some extent. DenseNet adopts a dense connection mechanism, which connects all layers. Each layer is concatenated with all previous layers along the channel dimension, achieving feature reuse and serving as the input for the next layer. This alleviates the phenomenon of gradient vanishing and enables better performance with fewer parameters and computations. The design philosophy of RegNet is to improve performance by increasing the width and depth of the model, proposing a new network design paradigm that focuses on designing a network design space rather than a single network instance. The entire process is similar to classic manual network design but elevated to the level of design space. The RegNet design space provides simple and fast networks under various flop ranges.

-

2.

Obtain soft labels from the pre-trained teacher model. After selecting the Convolutional Neural Network as the teacher model, obtain the soft targets from the teacher model. Soft targets serve as the carrier to transfer the “knowledge” from the teacher model to the student model, acting as a bridge for information migration from the teacher model to the student model. By converting the output of the teacher model into “soft targets”, the “dark knowledge” possessed by the teacher model, which performs well on the target training set, can be transferred to the student model. In this chapter, the traditional method of obtaining soft targets in knowledge distillation is chosen-using the classification probabilities and logits output generated by the teacher model during the training phase as the “soft targets” for training the student model. These “soft targets” guide the optimization direction of the student model, which performs better than having the student model learn high-dimensional features directly from the data. However, in many cases, the logit output of the softmax function on the teacher model often has a high probability of the correct classes. In contrast, the probabilities of all other classes approach zero. Apart from the true labels provided in the labelled dataset, not much other valuable information is provided. Hinton et al. introduced a softmax function with “temperature” to address this issue to generate the prediction probability for each class. Introducing the “temperature” parameter enhances the influence of low-probability classes. The specific form of the distillation temperature is:

$$\begin{aligned} \operatorname {softmax}\left( x_i\right) =\frac{\exp \left( \frac{Z_i}{T}\right) }{\Sigma _j \exp \left( \frac{Z_i}{T}\right) } \end{aligned}$$(1)where \(x_i\) is the i-th element of the prediction vector, \(Z_i\) is the probability of the i-th classes in the output vector, j is the total number of classes, and T is the temperature parameter. As the temperature parameter value T increases, the probability distribution generated by the softmax function becomes “softer”, providing more valuable information for model training. The inclusion of “soft targets” provides the student model with “dark knowledge” information from the teacher model, which has functions such as explanation, comparison, and integration. After the teacher network training is completed, the soft targets of the teacher model are obtained through the formula (1).

-

3.

Selection of lightweight student model. Streamlined and efficient lightweight convolutional neural networks have the advantages of low computational cost, minimal computer storage usage, and suitability for various loads. Through training with different models, this paper considers aspects such as accuracy and parameter count, ultimately selecting the ShuffleNet network as the backbone network for the student model. ShuffleNet, to some extent, draws inspiration from the DenseNet network by replacing the “shortcut” structure from Add to Concat, achieving feature reuse. However, unlike DenseNet, ShuffleNet does not densely use Concat, and after Concat, there is a channel transformation to mix features, which is one of the important reasons why it is both fast and accurate. Overall, this model starts from the perspective of directly affecting the model’s running speed, achieving the current best balance between speed and accuracy, making it very suitable for mobile model applications. Specific training results can be found in the Result section.

As shown in Fig. 4, the student model uses ShuffleNet as the backbone model, consisting of Conv1, MaxPool, Stage2, Stage3, Stage4, Cross-Attention, GlobalPool, and FC, aiming to improve detection accuracy while reducing the number of model parameters.

Chinese herbal medicine recognition model based on knowledge distillation and cross-attention. The ShuffleCANet model proposed in this article uses ShuffleNet as the backbone network. In order to reduce the number of model parameters while maintaining detection accuracy, a cross-attention module (blue rectangular area) is proposed. The entire model includes Conv1, Stage2, Stage3, Stage4, Cross-Attention and GlobalPool.

To make the student model more lightweight and enable the network to learn more global and local detail information from the image to improve the model recognition accuracy. This paper proposes a cross-attention module, as shown in the blue part of Fig. 4, to replace the Conv5 in the original network.

Assuming the output feature maps are c and s respectively. The cross-attention first cross-fuse the two feature maps to enable the network to learn more information. For the feature map c, c is multiplied by the weight coefficient \(\mathop {\alpha }\nolimits _{cc}\); s is multiplied by the weight coefficient \(\mathop {\beta } \nolimits _{cs}\), and then the two feature maps are added to obtain a new composition feature map C. Similarly, for the feature map s, we multiply c by the weight coefficient \(\mathop \beta \nolimits _{sc}\); s multiplies by the weight coefficient \(\mathop {\alpha }\nolimits _{ss}\), and then add the two feature maps to obtain a new feature map S.

Different weight settings are used for feature maps. This paper qualifies the respective weights as shown in Eq. (2) and satisfies \(\mathop {\alpha }\nolimits _{cc} + \mathop {\beta } \nolimits _{cs} = 1\), \(\mathop {\alpha }\nolimits _{ss} + \mathop \beta \nolimits _{sc} = 1\).

When focusing much more on channel attention, the feature map obtained after feature map C passing through the channel attention and spatial attention modules is represented as \(\mathop C\nolimits _{sc}\). Then, we multiply the weight feature of the feature map S after channel attention by the feature map \(\mathop C\nolimits _{s}\), to obtain the feature map \(\mathop C\nolimits _{\mathop {sc}\nolimits _1}\). To make the feature map’s obtained value within a reasonable range. Finally, we add the feature map obtained by multiplying feature map \(\mathop C\nolimits _{sc}\) by the coefficient \(\mathop \alpha \nolimits _{cc}\) and the feature map obtained by multiplying feature map \(\mathop C\nolimits _{\mathop {sc}\nolimits _1}\) by coefficient \(\mathop \beta \nolimits _{cs}\) to obtain the final feature map \(\mathop C\nolimits ^{'}\).

When focusing much more on spatial attention, the feature map obtained after feature map S passing through the channel attention and spatial attention modules is represented as \(\mathop S\nolimits _{cs}\). Then, we multiply the weight feature of the feature map C after spatial attention by the feature map \(\mathop S\nolimits _{c}\), to obtain the feature map \(\mathop S\nolimits _{\mathop {cs}\nolimits _1}\). To make the obtained value of the feature map is within a reasonable range. Finally, we add the feature map obtained by multiplying feature map \(\mathop S\nolimits _{cs}\) by coefficient \(\mathop \alpha \nolimits _{ss}\) and the feature map obtained by multiplying feature map \(\mathop S\nolimits _{\mathop {cs}\nolimits _1}\) by coefficient \(\mathop \beta \nolimits _{sc}\) to obtain the final feature map \(\mathop S\nolimits ^{'}\). As shown in Eq. (3),

This paper uses the channel and spatial attention module shown in Fig. 5, proposed by Wow al.35, to perform the above experiment.

The process of channel attention: Firstly, to perform global pooling and average pooling on the input feature map (pooling in the spatial dimension to compress the spatial size, it is convenient to learn the characteristics of the channel later). Then, the global and average pooling will be obtained. The average pooled result is sent to MLP learning in the multi-layer perceptron (based on the characteristics of the MLP learning channel dimension and the importance of each channel). Finally, the MLP output result is performed, and the “add” operation is performed, and then through Mapping processing of the Sigmoid function to obtain the final “channel attention value”. The formula is shown in (4),

The process of spatial attention: Firstly, to perform global pooling and average pooling on the input feature map (pool in the channel dimension to compress the channel size; it is convenient to learn the characteristics of the space later). Then, global and average pooling results are spliced according to channels. Finally, the convolution operation is performed on the spliced results to obtain the feature map, which is then processed through the activation function. The formula is shown in (5),

Loss function

Compared to hard targets, soft targets have the advantage of providing more information. Accordingly, a mixed loss function is used to guide the training of the student model during the training phase. The mixed loss function comprises a soft and hard target loss function in a linear combination. The mixed loss function is the formula (6).

Where \(\alpha\) is the balance coefficient between the soft and hard target loss functions. Under the constraint of soft targets, \(L_{soft}\) is the symmetric Jensen-Shannon divergence loss function. The formula is shown in (7). \(L_{hard}\) is the cross-entropy loss function under the constraint of hard targets, the formula is shown in (10).

Among them, \(Out_{teacher1}\) and \(Out_{teacher2}\) represent the result of two teachers, T represents the distillation temperature, JS is the loss function for calculating the divergence between two probability distributions, the formula is shown in (8).

Among them, P1 and P2 are two different probability distributions. KL represents the relative entropy formula, as shown in (9).

Among them, P and Q represent two probability distributions. p(x) and q(x) are represent the specific probabilities in a particular dimension.

Among them, CE represents the cross-entropy loss, and the formula is shown in (11). \(Out_{student}\) is the probability distribution output by the student model, \(Hard_{Label}\) is the actual probability distribution.

Among them, Label and Predict represent the true label and the probability distribution predicted by the student model, and N is the total number of samples.

Evaluation

In this paper, Top-1 Accuracy (ACC), Mean Precision (P), Mean Recall (R), and Mean F1_score are used as four metrics to evaluate the performance and reliability of the model. The confusion matrix is a table that summarises classification results, providing an intuitive representation of classification performance. It includes four important statistics: TP represents the number of samples that are positive and predicted as positive by the model. FP represents the number of samples that are actually negative but incorrectly predicted as positive by the model. FN represents the number of samples that are actually positive but incorrectly predicted as negative by the model. TN represents the number of samples that are negative and correctly predicted as negative by the model.

Based on this, four evaluation metrics can be calculated. Accuracy (ACC) represents the proportion of correctly classified samples to the total number of samples, and the formula is shown in (12).

Precision (P) represents the proportion of samples that are actually positive among all samples predicted as positive by the model, and the formula is shown in (13).

Recall (R) refers to the proportion of samples that are correctly predicted as positive among all samples that are actually positive, and the formula is shown in (14).

F1_score is a metric that combines precision and recall to evaluate the performance of a model, used for comprehensive evaluation of the model’s performance across all classes in multi-class problems, and the formula is shown in (15).

Generally speaking, the number of parameters (Params), the number of floating-point operations (Flops) and the memory occupied by the model parameters (Model_size) are usually used to evaluate the complexity and speed of a model. Theoretically, for model deployment, the smaller the Flops, the better. The more parameters a model has, the more complex the network structure. However, the higher the complexity of a model, the more computational resources and time are usually required for training and inference36. Therefore, when designing an object detection model, it is necessary to balance the complexity and performance of the model.

Results and discussion

Experimental setting

The deep learning framework used in the experiment is Pytorch, the computing environment is a Linux system, and the GPU is RTX 3080x2 (20 GB). To ensure the reliability of the results, relevant parameters are set in this paper. During the training of the student model, the stochastic gradient descent (SGD) optimizer is used, with an initial learning rate of 0.001 and a momentum of 0.9. During training, the learning rate decays to 0.1 times the original every 20 epochs. For the teacher model training, the official parameters are used. The number of training epochs is set to 100, and the batch size is 64 images per batch. The distillation temperature T for knowledge distillation is set to 7, and the weight coefficient \(\alpha\) is set to 0.2.

Table 1 presents the model performance under different distillation temperatures T and weight coefficients \(\alpha\). The experimental results show that when T is set to 7 and is 0.2, the model achieved the highest accuracy on the test set, indicating that the model achieved optimal performance under this specific parameter configuration.

Dataset

Due to the scarcity of publicly available datasets related to Chinese herbal medicine, the dataset used in this paper is the NB-TCM-CHM dataset constructed in 2024 by the College of Medicine and Biological Information Engineering of Northeastern University and Research Institute for Medical and Biological Engineering of Ningbo University13. This dataset consists of two parts, Dataset1 and Dataset2, where Dataset1 comprises 3384 images of 20 common Chinese medicinal materials, all annotated by Traditional Chinese Medicine experts, and can be used for training and testing methods for identifying Chinese medicinal materials. In addition, a dataset containing 400 images (Dataset 2) was established by taking photos with a smartphone, providing material for the practical efficacy evaluation of Chinese medicinal material identification methods. All relevant experiments in this paper are conducted on Dataset1.

For deep learning models, if the number of images in the dataset is too small, it may lead to underfitting and other issues that affect accuracy. Since the available dataset contains only 3382 images (with two images damaged in the original dataset), this paper processes the dataset by random rotation angles, adding noise, adjusting brightness, etc., as shown in Fig. 6.

Through processing, the dataset was expanded to 25959 images for subsequent experiments. The information of the dataset before and after data augmentation is shown in Fig. 7.

Comparative experiments

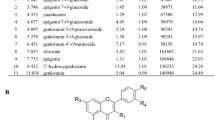

Comparative experiments were conducted with various classic network models to verify the proposed model’s effectiveness. All models adopted the idea of transfer learning. The models were first pre-trained on the public dataset ImageNet2012 and then trained and tested on the dataset used in this paper. All models use official code and parameter settings, only setting the output classes of their fully connected layers to 20. The performance comparison of each model is shown in Table 2.

The results in Table 2 show that the DenseNet and RegNet models achieved an accuracy of 0.991 and 0.989, respectively. Since the student model needs to perform better than the teacher model, this paper measures accuracy and F1_score, selecting DenseNet and RegNet as teacher models for guidance. ShuffleNet achieved 0.975 in both accuracy and F1_score, and this model has fewer parameters. Therefore, this paper chooses ShuffleNet as the backbone network of the student model.

Meanwhile, this paper also compares with classic networks such as AlexNet, VGG16, GoogleNet, and ResNet32. The results show that AlexNet and VGG16, as earlier CNN models, rely on deeper networks to extract features structurally. Still, they lack effective mechanisms to solve the gradient vanishing problem, which limits their ability to learn deeper features. GoogleNet and ResNet34 improve gradient flow by introducing measures such as residual connections, but there may still be challenges in balancing model complexity and parameter optimization. MobileNet_v2 and MobileNet_v3 adopt lightweight depthwise separable convolutions to reduce parameters and computation, but this design may sacrifice some representational capacity, especially in learning fine-grained features. MobileViT is a transformer-based algorithm model that utilizes self-attention and local self-attention mechanisms to effectively handle long-range dependencies and understand the relationships between different input elements. However, its ability is limited when recognizing certain classes of Chinese herbal medicines that are quite similar. The number of parameters may be small for lightweight models such as SqueezeNet, GhostNet, and MobileNeXt. However, due to the large inter-class differences and small intra-class differences in certain Chinese herbal medicines, the learning ability of the models is limited, resulting in suboptimal recognition accuracy. Although the accuracy (ACC) and F1_score of the proposed Chinese herbal medicine recognition network ShuffleCANet, based on knowledge distillation and cross-attention, do not surpass the performance of the two teacher models DenseNet and RegNet, the metrics are close. Notably, the parameter count of the model is significantly reduced. This is likely because the proposed model reduces the convolutional layers but enhances key features through a cross-attention mechanism, thereby improving the overall and detailed information in the images. This allows the network to better distinguish between classes. Additionally, through knowledge distillation, the student model learns more useful information, maintaining performance close to the teacher models while ensuring the model remains lightweight. Generally speaking, the smaller the model, the faster it runs, the shorter the test time for each batch, and the smaller its time complexity. To verify the time complexity of the model, this paper marks it by testing the number of parameters and model size. It can be seen from Table 2 that the model proposed in this paper is smaller and has fewer parameters. Compared with the baseline model, the number of parameters is nearly 50% less, but the accuracy is improved by 1.3%.

Similar to the recommendation system57,58,59, for traditional Chinese medicine diagnosis, it is particularly important to accurately identify the class of Chinese herbal medicine and take measures to prescribe the right medicine. To improve detection accuracy, the attention mechanism has been widely used in convolutional neural networks and graph convolutional networks60,61,62. To validate the performance of the cross-attention module proposed in this paper, we conducted comparative experiments with CBAM35, BAM63, and AFA64 attention modules. The experimental results are shown in Table 3.

S_AFA(x0.5) indicates using the smallest scale ShuffleNet as the backbone network, with the addition of the AFA attention mechanism. S_AFA_1_no indicates using ShuffleNet as the backbone network with the AFA attention mechanism added after Conv1, but without using transfer learning during training. S_AFA_5 indicates the addition of the AFA attention mechanism after Conv5 in ShuffleNet. S_AFA_1_5 indicates the addition of the AFA attention mechanism after both Conv1 and Conv5 in ShuffleNet. S_AFA indicates replacing Conv5 with the AFA attention mechanism. S_CBAM indicates replacing Conv5 with the CBAM attention mechanism. S_BAM indicates replacing Conv5 with the BAM attention mechanism. S_AFA_1_CS_5 indicates the addition of the AFA attention mechanism after Conv1 and the CS attention mechanism proposed in this paper after Conv5. S_CS_no indicates replacing Conv5 with the CS attention mechanism proposed in this paper without using transfer learning during training. S_CS indicates replacing Conv5 with the CS attention mechanism proposed in this paper and using transfer learning during training. S_4 indicates deleting Conv5 without adding any attention mechanism.

By comparing the results of S_AFA_1_no with S_AFA_1, and S_CS_no with S_SC (ShuffleCANet) in Table 3, it can be seen that the performance of the model after transfer learning can be improved by nearly 8% in terms of ACC and F1_score compared to the model without transfer learning, indicating the importance of transfer learning. By comparing the performance of S_AFA, S_CBAM, S_BAM, and S_CS (ShuffleCANet), it can be seen that the proposed ShuffleCANet can improve by nearly 1% and has fewer parameters. Compared with the S_4 model, due to the proposed cross-attention mechanism having very few parameters, the accuracy and F1_score can be improved by 1.5% with a minimal increase in parameters, indicating that the proposed cross-attention model performs well in recognizing different classes of Chinese herbal medicine. Compared with the S_AFA(x0.5) model, although this model has a similar number of parameters to the proposed model, its feature learning capability is limited, resulting in a performance gap of nearly 15% compared to the proposed model. Through the comparative experiments, it can be seen that the proposed cross-attention module performs well in Chinese herbal medicine recognition.

To evaluate the generalization ability of the model, a confusion matrix was generated from the test set images containing 20 classes of herbs, as shown in Fig. 8. The labels 0-19 represent Alpiniae_Katsumadai_Semen, Amomi_Fructus, Amomi_Fructus_Rotundus, Armeniacae_Semen_Amarum, Chaenomelis_Fructus, Corni_Fructus, Crataegi_Fructus, Foeniculi_Fructus, Forsythiae_Fructus, Gardeniae_Fructus, Kochiae_Fructus, Lycii_Fructus, Mume_Fructus, Persicae_Semen, Psoraleae_Fructus, Rosae_Laevigatae_Frucyus, Rubi_Fructus, Schisandrae_Chinensis_Fructus, Toosendan_Fructus, Trichosanthis_Pericarpoium, respectively.

From Fig. 8, it can be seen that the recognition ability for the Chinese herbal medicine classes Armeniacae_Semen_Amarum and Persicae_Semen by the two teacher models DenseNet and RegNet, the proposed model ShuffleCANet, and ShuffleNet is relatively poor. The main reason may be that the differences between these two classes in the dataset are relatively small, indirectly indicating a problem of large inter-class differences and small intra-class differences among different Chinese herbal medicines, making it difficult for the models to recognize them. For the recognition of Armeniacae_Semen_Amarum and Persicae_Semen, ShuffleCANet has better recognition ability than the ShuffleNet model and shows good feature extraction and recognition ability for other classes.

Visualization

In this paper, the Grad-CAM method is used to visualize the features extracted from the intermediate layers of the model and the final output features of different models. This helps to further understand the features learned by the Chinese herbal medicine recognition model at different layers and to conduct comparison and analysis.

Figure 9 shows the visualization results of the output feature maps of Conv1, Stage2, Stage3, Stage4, and Cross-Attention after the completed model training. Figure 9 shows that the Chinese herbal medicine recognition model learning has an obvious hierarchy. After Stage 2, only the edge information of the image is learned in the shallow layers of the network. The visualization results of Stage 3 and Stage 4 show that as the number of network layers increases, the model gradually focuses on various regions of the medicinal materials. The visualization results after cross-attention indicate that the model has accurately focused on various herbs, demonstrating the effectiveness of the cross-attention mechanism proposed in this paper.

Similarly, this paper visualizes and analyzes the final output features of the teacher models RegNet, DenseNet, ShuffleNet, and ShuffleCANet, respectively, as shown in Fig. 10.

As seen from Fig. 10, the teacher models RegNet, DenseNet, and the proposed ShuffleCANet model can all focus well on key areas when detecting different classes of Chinese herbal medicine. In contrast, the ShuffleNet model tends to focus on certain areas of the image and fails to accurately locate the key areas, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed model in detecting classes of Chinese herbal medicine.

Conclusion

To achieve a Chinese herbal medicine recognition model that can be deployed on mobile devices with lightweight requirements while ensuring performance, this paper proposes a Chinese herbal medicine recognition network based on knowledge distillation and cross-attention. This network uses ShuffleNet as the backbone of the student model. To enable the network to focus on global and local information in the image and improve recognition performance, this paper proposes a cross-attention model and integrates it into the student model. The student model is trained under the supervision of two teacher models, DenseNet and RegNet. The proposed student model, ShuffleCANet, achieves an accuracy and F1_score of 0.988, with model parameters amounting to 1.32M. Compared with the baseline model ShuffleNet, the parameters are reduced by nearly 50%, but the accuracy is improved by about 1.3%. Despite having significantly fewer parameters than the teacher models, the accuracy and F1_score are comparable, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method through experimental results. In the future, it is hoped to construct a more diverse dataset to enhance the model’s ability to recognize complex classes of Chinese herbal medicine.

Data availability

Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to Q.H.

References

Wu, N., Zhou, Y., Xu, H. & Wu, X. Chinese herbal recognition databases using human-in-the-loop feedback. In: Proc. 5th International Conference on Computer Science and Application Engineering. 1–6 (2021).

Jia, W., Yan, Y., Wen, C., Wu, C. & Wang, Q. Texture feature extraction research of sections of traditional Chinese medicine. J. Chengdu Univ. Trad. Chin. Med. 44, 1–6 (2017).

Cheng, M., Zhan, Z., Zhang, W. & Yang, H. Textual research of “Huangbo’’ in classical prescriptions. China J. Chin. Materia Med. 44, 4768–4771 (2019).

Liu, S., Chen, W. & Dong, X. Automatic classification of Chinese herbal based on deep learning method. In 2018 14th International Conference on Natural Computation, Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery (ICNC-FSKD) (ed. Liu, S.) 235–238 (IEEE, 2018).

Huang, F.-L. et al. Research and implementation of Chinese herbal medicine plant image classification based on Alexnet deep learning model. J. Qilu Univ. Technol. 34, 44–49 (2020).

Xing, C. et al. Research on image recognition technology of traditional Chinese medicine based on deep transfer learning. In 2020 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Electromechanical Automation (AIEA) (ed. Xing, C.) 140–146 (IEEE, 2020).

Zhang, W. et al. Chinese herbal medicine classification and recognition based on deep learning. Smart Healthcare 6, 1–4 (2020).

Yang, J., Xi, R., Zhang, Y. & Wang, W. Visual identification on Chinese herbal medicine plants based on deep learning. Chin. J. Stereol. Image Anal. 28, 203–211 (2023).

Hao, W., Han, M., Yang, H., Hao, F. & Li, F. A novel Chinese herbal medicine classification approach based on efficientnet. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. 9, 304–313 (2021).

Gang, H., Guanglei, S., Xiaofeng, W. & Jinlin, J. Ccnnet: A novel lightweight convolutional neural network and its application in traditional Chinese medicine recognition. J. Big Data 10, 114 (2023).

Miao, J., Huang, Y., Wang, Z., Wu, Z. & Lv, J. Image recognition of traditional Chinese medicine based on deep learning. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 11, 1199803 (2023).

Zheng, L., Long, W., Yi, J., Liu, L. & Xu, K. Enhanced knowledge distillation for advanced recognition of Chinese herbal medicine. Sensors 24, 1559 (2024).

Tian, D., Zhou, C., Wang, Y., Zhang, R. & Yao, Y. Nb-tcm-chm: Image dataset of the Chinese herbal medicine fruits and its application in classification through deep learning. Data Brief 54, 110405 (2024).

Khader, F. et al. Cascaded cross-attention networks for data-efficient whole-slide image classification using transformers. In International Workshop on Machine Learning in Medical Imaging (ed. Khader, F.) 417–426 (Springer, 2023).

Chu, M. et al. Dccat: Dual-coordinate cross-attention transformer for thrombus segmentation on coronary oct. Med. Image Anal. 97, 103265 (2024).

Shen, J. et al. Icafusion: Iterative cross-attention guided feature fusion for multispectral object detection. Pattern Recogn. 145, 109913 (2024).

Liu, Q., Liu, X. P., Zhang, L. J. & Zhao, L. M. Image texture feature extraction and recognition of chinese herbal medicine based on gray level co-occurrence matrix. Adv. Mater. Res. 605, 2240–2244 (2013).

Yu, X., Shi, L. & Bi, X. Big data of rhizome Chinese herbal medicine harvester from the perspective of internet. In 2021 International Wireless Communications and Mobile Computing (IWCMC) (ed. Yu, X.) 428–431 (IEEE, 2021).

Sun, X. & Qian, H. Chinese herbal medicine image recognition and retrieval by convolutional neural network. PLoS ONE 11, e0156327 (2016).

Cai, C. et al. Classification of Chinese herbal medicine using combination of broad learning system and convolutional neural network. In 2019 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (SMC) (ed. Cai, C.) 3907–3912 (IEEE, 2019).

Hu, J.-L. et al. Image recognition of Chinese herbal pieces based on multi-task learning model. In 2020 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM) (ed. Hu, J.-L.) 1555–1559 (IEEE, 2020).

Wang, Y., Sun, W. & Zhou, X. Research on image recognition of Chinese herbal medicine plants based on deep learning. Inf. Trad. Chin. Med. 37, 21–25 (2020).

CHEN, Y. & ZOU, L.-s. Intelligent screening of pieces of chinese medicine based on bmfnet-wgan. Chin. J. Exp. Trad. Med. Formulae 107–114 (2021).

Liu, S., Chen, W., Li, Z. & Dong, X. Chinese herbal classification based on image segmentation and deep learning methods. In Advances in Natural Computation, Fuzzy Systems and Knowledge Discovery: ceedings of the ICNC-FSKD 2021 17 (ed. Liu, S.) 267–275 (Springer, 2022).

Qin, Z. et al. An improved method of convolutional neural network based on image recognition of chinese herbal medicine. Int. J. Appl. Math. Mach. Learn. 3, 97–112 (2022).

Huang, M. & Xu, Y. Image classification of Chinese medicinal flowers based on convolutional neural network. Math. Biosci. Eng. MBE 20, 14978–14994 (2023).

Tang, Y. et al. Classification of Chinese herbal medicines by deep neural network based on orthogonal design. In 2021 IEEE 4th Advanced Information Management, Communicates, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IMCEC) Vol. 4 (ed. Tang, Y.) 574–583 (IEEE, 2021).

Xu, Y. et al. Multiple attentional pyramid networks for Chinese herbal recognition. Pattern Recogn. 110, 107558 (2021).

Han, M., Zhang, J., Zeng, Y., Hao, F. & Ren, Y. A novel method of Chinese herbal medicine classification based on mutual learning. Mathematics 10, 1557 (2022).

Hao, W., Han, M., Li, S. & Li, F. Mtal: A novel Chinese herbal medicine classification approach with mutual triplet attention learning. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 8034435 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Combined channel attention and spatial attention module network for chinese herbal slices automated recognition. Front. Neurosci. 16, 920820 (2022).

Wu, N., Lou, J., Lv, J., Liu, F. & Wu, X. Chinese herbal recognition by spatial-/channel-wise attention. In 2022 IEEE Conference on Telecommunications, Optics and Computer Science (TOCS), 1145–1150 (IEEE, 2022).

Zhang, C., Jiang, Y. & Dai, J. Design and implementation of Chinese herbal medicine image recognition classification model. J. Fujian Comput. 40, 14–20 (2024).

Yumei, L., Chenxu, Z. & Chuying, W. Image recognition of traditional Chinese medicine based on semantic recognition. In 2024 IEEE 7th Eurasian Conference on Educational Innovation (ECEI) (ed. Yumei, L.) 224–227 (IEEE, 2024).

Woo, S., Park, J., Lee, J.-Y. & Kweon, I. S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In: Proc. European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 3–19 (2018).

Hou, Q., Ke, Y., Wang, K., Qin, F. & Wang, Y. Synchronous composition and semantic line detection based on cross-attention. Multimedia Syst. 30, 1–12 (2024).

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I. & Hinton, G. E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst.25 (2012).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. Preprint at arXiv:1409.1556 (2014).

Szegedy, C. et al. Going deeper with convolutions. In: Proc. IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 1–9 (2015).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In: Proc. IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 770–778 (2016).

Sandler, M., Howard, A., Zhu, M., Zhmoginov, A. & Chen, L.-C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In: Proc. IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 4510–4520 (2018).

Howard, A. et al. Searching for mobilenetv3. In: Proc. IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 1314–1324 (2019).

Ma, N., Zhang, X., Zheng, H.-T. & Sun, J. Shufflenet v2: Practical guidelines for efficient cnn architecture design. In: Proc. European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 116–131 (2018).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K. Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In: Proc. IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 4700–4708 (2017).

Tan, M. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. Preprint at arXiv:1905.11946 (2019).

Tan, M. & Le, Q. Efficientnetv2: Smaller models and faster training. In: International conference on machine learning, 10096–10106 (PMLR, 2021).

Radosavovic, I., Kosaraju, R. P., Girshick, R., He, K. & Dollár, P. Designing network design spaces. In: Proc. IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 10428–10436 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. A convnet for the 2020s. In: Proc. IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 11976–11986 (2022).

Ding, X. et al. Repvgg: Making vgg-style convnets great again. In: Proc. IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 13733–13742 (2021).

Koonce, B. & Koonce, B. Squeezenet. Convolutional neural networks with swift for tensorflow: image recognition and dataset categorization 73–85 (2021).

Chollet, F. Xception: Deep learning with depthwise separable convolutions. In: Proc. IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 1251–1258 (2017).

Han, K. et al. Ghostnet: More features from cheap operations. In: Proc. IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 1580–1589 (2020).

Zhou, D., Hou, Q., Chen, Y., Feng, J. & Yan, S. Rethinking bottleneck structure for efficient mobile network design. In Computer Vision-ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, August 23–28, 2020, Proceedings, Part III 16 (ed. Zhou, D.) 680–697 (Springer, 2020).

Ding, X. et al. Unireplknet: A universal perception large-kernel convnet for audio video point cloud time-series and image recognition. In: Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 5513–5524 (2024).

Dosovitskiy, A. An image is worth 16x16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. Preprint at arXiv:2010.11929 (2020).

Mehta, S. & Rastegari, M. Mobilevit: light-weight, general-purpose, and mobile-friendly vision transformer. Preprint at arXiv:2110.02178 (2021).

Dong, X. et al. A hybrid collaborative filtering model with deep structure for recommender systems. In: Proc. AAAI Conference on artificial intelligence, vol. 31 (2017).

Mandal, S. & Maiti, A. Fusiondeepmf: A dual embedding based deep fusion model for recommendation. Preprint at arXiv:2210.05338 (2022).

Mandal, S. & Maiti, A. Heterogeneous trust-based social recommendation via reliable and informative motif-based attention. In: 2022 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), 1–8 (IEEE, 2022).

Fan, W. et al. Graph neural networks for social recommendation. In: The world wide web conference, 417–426 (2019).

Mandal, S. & Maiti, A. Graph neural networks for heterogeneous trust based social recommendation. In: 2021 international joint conference on neural networks (IJCNN), 1–8 (IEEE, 2021).

Rossi, R. A., Ahmed, N. K. & Koh, E. Higher-order network representation learning. Comp. Proc. The Web Conf. 2018, 3–4 (2018).

Park, J. Bam: Bottleneck attention module. Preprint at arXiv:1807.06514 (2018).

Cui, C. et al. Adaptive feature aggregation in deep multi-task convolutional neural networks. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 32, 2133–2144 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The Dezhou R&D Project under Grand DZSKJ202411 and the Dezhou Big Data and Intelligent Sensing Technology Engineering Research Center under Grand 10504001014 partly supports this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.H.: conceptualization, methodology, software, experimental, writing–original draft. W.Y.: methodology, writing–review and editing. G.L.: formal analysis, visualization. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hou, Q., Yang, W. & Liu, G. Chinese herbal medicine recognition network based on knowledge distillation and cross-attention. Sci Rep 15, 1687 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85697-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85697-6