Abstract

Tunnel stability is a critical factor in complex geological conditions, particularly in rock masses with steeply dipping layers. Among widely used methods, the Convergence–Confinement Method (CCM), a prevalent two-dimensional (2D) approach, effectively captures the relaxation process preceding support installation. However, most studies focus on homogeneous or horizontally layered rock masses, often overlooking the influence of steeply dipping, and layered geological formations. This study investigates the influence of layer dip angle and layer position on the stress relaxation factor (λ) and tunnel deformation through parametric analysis. The results indicate that λ increases with steeper dip angles, such as 60° and 90°, and decreases as the layers are positioned farther from the tunnel center, for instance, two tunnel widths above or below. Tunnel deformation is highly influenced by these factors, and the optimized λ values allow the 2D Convergence–Confinement Method (CCM) predictions to closely correlate with 3D simulation results. These findings enhance the applicability of the Convergence–Confinement Method (CCM) for tunnel stability analysis in steeply dipping, layered rock masses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tunnels are essential for enhancing transportation infrastructure, particularly in regions with challenging geological conditions, such as Ethiopia. To address these challenges, Ethiopia has been integrating tunnels into its infrastructure through various large-scale geotechnical projects. Despite the relatively low number of tunnels constructed in recent decades, the country has encountered several significant tunnel collapses1,2,3. The primary failure mode in these tunnels is stress-induced, as indicated by the observed deformation patterns and stress distribution3,4,5. However, local geological structures may also impact the overall stability. Therefore, accurate assessment of the rock mass response is critical for preventing tunnel failure6. While 3D analysis offers a more accurate representation of rock mass behavior during tunneling, its application is often constrained by high computational demands and complexity. Consequently, tunnel engineers commonly favor 2D approaches for the analysis and design of underground excavations7.

The Convergence–Confinement Method (CCM), initially introduced by Panet and Guenot8, is the most widely adopted 2D approach for approximating the three-dimensional behavior of tunneling9,10. Despite its widespread use, existing studies on the 2D Convergence–Confinement Method (CCM) predominantly focus on tunnels located in homogeneous or horizontally layered media, overlooking the influence of steeply dipping layered rock masses. In practice, many excavations are carried out in inclined strata that contain weak zones11,12. Consequently, the applicability of the 2D Convergence–Confinement Method (CCM) for assessing the stability of tunnels in steeply dipping layered rock masses remains insufficiently investigated. Zhou et al.13 emphasized that the orientation of rock layers is a critical factor in determining the macroscopic behavior of rock masses, including excessive deformation and various failure mechanisms. However, the relationship between the optimal stress factor (λ) and different layer configurations, such as dip angle and layer positioning, has not been sufficiently explored.

This paper aims to evaluate the effectiveness of the 2D Convergence–Confinement Method (CCM) in assessing the behavior of tunnels in steeply dipping layered rock masses, by comparing its results with those obtained from 3D numerical analyses. Additionally, it investigates key factors influencing tunnel stability, including the layer dip angle and layer positioning, with a focus on their impact on the optimal stress relaxation factor and the response of the surrounding rock mass, particularly regarding tunnel convergence.

Study area

Location and topography

This study examines the geotechnical aspects of a newly constructed railway tunnel (T-04) along the Awash-Kombolcha-Hara Gebeya railway project (Fig. 1a and b). The tunnel, situated near Kara-Kore town, was constructed using the Drill and Blast method, tailored to address the prevailing geological conditions and project specifications. The structure spans a total length of 1530 m and reaches a maximum overburden depth of 322 m. Geographically, the tunnel is located at 10°27′N latitude and 39°58′E longitude, with its longitudinal axis oriented approximately in the south-to-north direction. The southern (entrance) portal is positioned at chainage 178 + 090 km, while the northern (exit) portal is situated at chainage 179 + 620 km. The tunnel intersects two distinct geological formations: the “Ashangi Formation-Tas”, predominantly composed of black and dark grey basaltic rocks, and the “Kemissie Formation-Tk”, consisting of rhyolite, ignimbrite, tuff, and volcanic ash.

Geotechnical parameters

At the tunnel site, subsurface investigations were conducted, including soil investigation boreholes, in situ field testing, and laboratory analysis of samples retrieved from the boreholes. These investigations were performed to characterize the ground conditions and geotechnical properties of the site. For the basaltic and volcanic ash units, rock mass properties were estimated using conversion equations embedded in the “RocData” software, based on geotechnical data from reports in the surrounding area. Furthermore, a fault zone, consisting of highly fractured rock mass, is located at the interface of the two lithological units, occurring at the transition between the “Kemissie Formation” and the “Ashangi Formation”. The rock mass material properties are summarized in Table 1.

Mechanical properties of interfaces between rock layers

The interfaces between rock layers exhibit distinct mechanical characteristics, as their strength and deformability are governed by the properties of the adjacent rock masses14. According to Huang et al.15, the shear modulus, friction angle, and cohesion of these interfaces can be approximated as the average values of the two adjoining materials, while the tensile strength is defined by the lesser value of the two materials (Eqs. 1 and 2). In line with this methodology, the mechanical properties attributed to the discontinuity interfaces between the different rock layers are summarized in Table 2.

The normal stiffness (\({k}_{n}\)) is calculated as:

where \(E\) is the elastic modulus of the rock mass or support material, and d is the thickness of the interface.

The shear stiffness (\({k}_{s}\)) is given by:

where G is the shear modulus of the rock mass or support material, and d is the thickness of the interface.

The shear modulus of the rock mass, calculated as: \(G=\frac{E}{2\left(1+v\right)}\), with ν being the Poisson’s ratio of the rock mass.

Shotcrete

Shotcrete is a specialized concrete material applied to the excavated surface of tunnels. Its primary function is to stabilize the surrounding rock mass by preventing loosening and providing structural support. The shotcrete lining serves to seal rock joints, mitigate rockfall, and control overbreak. The material properties of the shotcrete used in the numerical analysis are provided in Table 3.

Rock bolt properties

The tunnel support system includes an anchoring arrangement comprising Ø26 mm rock bolts, each with a length of 4 m. These rock bolts are installed in accordance with the specifications defined for each support class. The bolts are fully grouted along their entire length using a cement-based grout or resin with equivalent characteristics. The cement grout is designed to achieve a minimum compressive strength of 21.0 MPa after 7 days. The material properties of the rock bolts used in this study are detailed in Table 4.

Numerical modeling

The numerical analysis conducted in this study begins with a 2D finite element method (FEM) analysis using the Phase2 version 8.0 software package. This analysis evaluates the stress distribution associated with tunnel excavation and support installation based on a 2D numerical model16. Subsequently, a 3D distinct element method (DEM) analysis is performed using 3DEC version 5.20 to investigate the effects of fault dip angle and fault line location on the deformation behavior of the tunnel.

Development of the 2D model

To evaluate the effect of truncated boundary distance on the vertical and lateral deformation of the tunnel, a series of stress–strain analyses were conducted on the rock mass. These analyses varied the boundary width and height while maintaining consistent material properties, in-situ stress conditions, and other parameters. Based on the results of the preliminary analysis, the model width was set to 8 times the tunnel opening width (80 m or B + 70 m), and the model height was set to 8 times the tunnel opening height (80 m or H + 70 m) (Fig. 2).

The tunnel has a horseshoe-shaped cross-section with dimensions of 9.08 m in width and 9.84 m in height (Fig. 2b). The tunnel center is located 324 m below the ground surface. In this study, the 2D model was discretized using six-noded triangular elements. The mesh design was carefully optimized to ensure accurate results while maintaining computational efficiency17. A graded mesh was applied across all models, with finer mesh elements in regions of high-stress gradients, such as near the tunnel opening. The mesh density gradually decreases from the center outward to the model boundaries.

Prescribed boundary conditions and in-situ stress

The boundary conditions for the model were defined using a combination of stress and velocity constraints to accurately replicate the behavior of the tunnel. The model dimensions in Phase2 were carefully selected to encompass the zone of influence induced by tunnel excavation, thereby minimizing boundary effects on the analysis. A key aspect of the model construction involved assessing the surrounding pressure to evaluate the stability of the rock mass around the tunnel13. This study employs two distinct approaches for this evaluation, as outlined below.

Model-1: By considering rock pressure theory

In this section, the rock pressure theory proposed by Bierbaumer18 is employed to determine the tunnel loading. According to the theory, a tunnel is subjected to a load from the rock mass, which is bounded by a parabola of height. The crown of the tunnel (H) is located at a depth of 319.5 m from the ground surface. To simulate the overburden gravitational loading at the top of the crown, a vertical stress of 1.19 MPa was applied. This value is based on an average material density of 2700 kg/m3, an overburden depth of 319.5 m, and a reduction factor of 0.138.

Model-2: By considering the total depth

In situ stresses are influenced by the depth below the ground surface. The support pressure and tunnel closure are also affected by these in situ stresses. Therefore, the tunnel depth, or overburden, is a critical parameter in assessing the surrounding pressures in tunnels15. In this section, the entire depth is considered in the calculation of deformations within the rock mass surrounding the tunnel. As such, the top boundary of the model is located 284 m below the ground surface. To simulate the overburden gravitational loading, a vertical stress of 7.67 MPa is applied at the top of the model. This value is derived from an average overburden material density of 2700 kg/m3 and an overburden depth of 284 m.

Material constitutive models

The constitutive model describes the relationship between applied stress and material deformation. In this study, the shotcrete support is assumed to remain in an elastic state, as its modulus of elasticity is significantly greater than that of the surrounding rock. Consequently, an elastic isotropic constitutive model was used to simulate the behavior of the shotcrete material. The rock masses in Phase 2 were modeled using a linear elastic-perfectly plastic Mohr–Coulomb constitutive model. While more advanced rock constitutive models, such as strain-softening, can more accurately capture the nonlinear stress–strain behavior of rock masses, they require several input parameters. Therefore, the Mohr–Coulomb model was deemed sufficient for this study. The Mohr–Coulomb model is a conventional approach for representing the failure of soils and rocks14. The mechanical behavior of interfaces is represented by the Coulomb slip model.

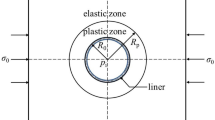

2D simulation with the CCM method

In the 2D analysis, the tunnel excavation and support installations were simulated using the Convergence–Confinement method (CCM). The deformation occurring prior to the application of the support system could not be directly modeled; however, its effects were indirectly accounted for by using the stress relaxation coefficient (λ)19. The stress relaxation coefficient (λ) was applied to simulate the delayed installation of the support during the field tunneling process. During excavation, a portion of the initial ground stress, \({(1-\uplambda )\sigma }^{0}\), is induced on the surrounding ground before the support is applied. Subsequently, a portion of the remaining stresses is transferred to the tunnel supports, which are installed after a total stress release when λ = 1. The stress release factor refers to the portion of ground stresses acting at the end of the preceding stage. A summary of the 2D computation phases is shown in Fig. 2.

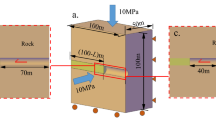

Development of the 3D numerical model

In this paper, the 3DEC Version 5.20 software package, developed by Itasca20, is used to construct the 3D numerical model and perform the stress analysis associated with tunnel excavation and support installations. It is also employed to evaluate the performance of the proposed 2D plane strain solutions. The 3D model is a brick-shaped polyhedron with dimensions of 80 m in the X and Z directions, and 50 m in the Y direction, as shown in Fig. 3. The tunnel is excavated through a rock mass consisting of Basalt, Volcanic Ash, and a fault zone.

Boundary

The boundary conditions and model dimensions used in the 3D model were selected as a combination of stress and velocity constraints, similar to those used in the 2D model. However, for the 3D model, the length of the numerical model in the Y direction is set to 50 m (Fig. 3). The boundary edges in the Y direction are fixed to ensure stability and accurate simulation results. As a result, the model length is more than five times the width of the tunnel opening. According to Hoek et al.21, the model length in the tunnel direction should be at least four and a half times the tunnel width from the advancing face.

Discretization of the 3D-model

Discretization of blocks in 3DEC is achieved by subdividing the blocks into smaller elements, which can be either quadrilateral or tetrahedral. Quadrilateral elements offer higher accuracy and are well-suited for plasticity calculations; however, the presence of inclined discontinuities and varying lithologies in the current model makes the application of quadrilateral elements more challenging. In contrast, tetrahedral elements provide greater flexibility in meshing irregular block geometries22. Therefore, tetrahedral zoning is employed for the present study (Fig. 4a and b).

Excavation and ground support

The A3 rock class involves challenging gear placements with potential hazardous falls, requiring advanced climbing skills. The length excavated and immediately supported is 2 m per stage. The numerical model extends 50 m along the tunnel axis. Therefore, the entire excavation and support installation process is carried out in 26 stages. The adopted excavation procedure aligns with the actual field sequences. The bolts were simulated in 3DEC software using the “Cable” structure element provided within the software20. The shotcrete was modeled using the “Liner” structure element (Fig. 5a and b) available in 3DEC software20.

Calibration of 2D CCM with the 3D numerical results

The CCM controlling parameter λ was calibrated to ensure that the 2D CCM and 3D numerical analyses predicted the settlement profile as accurately as possible. The following procedure was applied: Vertical displacements computed by the CCM method at 20 different locations along the top of the model were used to create a simulation line (S2D), while displacements obtained from the 3D analyses (S3D) formed an observation line. The difference between the two was quantified using the sum of the squared errors method, as expressed in Eq. 3:

Several 2D calculations were performed by varying the stress release coefficient (λ) in steps of 0.05 until the optimal value based on the comparison criteria was determined. Ultimately, the appropriate stress release coefficient (λ) was obtained by fitting the 2D calculation results to the 3D results (Fig. 6), thereby minimizing the value of Eq. 3.

In this paper, the initial value of the stress relaxation factor (λ) was determined by considering the ground load pressure based on the height formula proposed by Protodyakonov23 (Eq. 4):

where λ is the stress relaxation factor, \({\sigma }_{Protodyakonov}\) is the vertical stress on the tunnel wall, calculated using Protodyakonov’s parabola. Protodyakonov’s parabola is a method in rock mechanics used to estimate the stress distribution around underground openings, such as tunnels, to understand the behavior of the rock mass during tunnel excavation. \({\sigma }_{V}\) represents the total vertical stress, including all vertical stresses acting on the tunnel, such as the weight of the overlying rock and any additional loads.

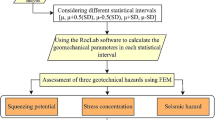

Parametric study

A parametric study was conducted to investigate the influence of different layer dip angles and layer locations on the stress relaxation coefficient (λ) and the tunnel rock behavior, specifically in terms of the convergence of the surrounding rock. In this study, only one parameter was varied at a time to isolate and observe the specific effect of that parameter on the results. The parametric calculations were performed using Phase2 and 3DEC software.

Effect of layer dip angle (β)

In this section, the effect of the layer dip angle (β) on the convergence of the tunnel surrounding rock and the corresponding stress relaxation coefficient (λ) is studied. Five dip angles, β = 0°, 30°, 45°, 60°, and 90°, are selected, where 0° and 90° represent horizontal and vertical layers, respectively (Fig. 7). The dip angles are chosen based on the recommendations of Jingyuan24 and Do et al.25.

Effect of layer location (L)

In this study, the layer location (L) is defined as the minimum distance between the tunnel center and the adjacent layer. The influence of the distance from the layer to the tunnel opening (as shown in Fig. 8) on the tunnel convergence and the corresponding stress relaxation coefficient (λ) is examined. Various layers, positioned above, below, and at the center of the tunnel opening, are considered. The distance of the layer from the tunnel opening (L) is expressed in terms of the tunnel span (B).

Results and discussion

Effect of layer dip angle on the stress relaxation factor

As shown in Fig. 9, the settlement profiles for different layer dip angles vary significantly. When the layer is oriented horizontally (i.e., layer dip angle 0°) or vertically (i.e., layer dip angle 90°), the settlement profile follows a symmetrical pattern. However, for layer dip angles of 30°, 45°, and 60°, the presence of inclined lithologies and discontinuities causes the settlement profiles to follow an asymmetrical pattern. Such asymmetrical patterns are expected when a tunnel is excavated through inclined lithologies.

In addition, the surface settlement is slightly influenced by the layer dip angle. When the layer is oriented horizontally (i.e., layer dip angle 0°) or vertically (i.e., layer dip angle 90°), the settlement profile follows a symmetrical pattern, with the maximum settlement occurring at the tunnel centerline. However, for layer dip angles of 30°, 45°, and 60°, the presence of inclined lithologies and discontinuities causes the settlement profiles to follow an asymmetrical pattern. Such an asymmetric pattern is expected when a tunnel is excavated through inclined lithologies. As shown in Fig. 9, the location of maximum settlement shifts from the tunnel centerline toward the area with weaker lithology. When the layer dip angle is 0°, the stress relaxation factor (λ) is relatively small. Higher values of λ are obtained for steeply dipping layered rock masses (i.e., β = 60° and 90°). The value of λ increases from 0.3 to 0.6 as the layer dip angle changes from 0° to 90°, indicating that the optimum stress relaxation factor (λ) has a direct relationship with the layer dip angle. Thus, as the layer dip angle increases from 0° to 90°, the stress relaxation factor (λ) increases considerably, and vice versa.

Effect of layer dip angle on deformation of surrounding rock

Table 5 shows the variations in displacements calculated using the 2D CCM and 3D analysis for different layer dip angles. As expected, the deformations of the tunnel wall varied with the layer dip angle. The maximum deformation of 71.4 mm occurred when the layer dip angle was 45° at the crown of the wall. The second-largest deformation of 70.8 mm occurred at the right side of the wall, also for a layer dip angle of 45°. This is due to the change in the rock mass behavior between sliding and bending at a 45° dip angle25. Furthermore, when the inclination angle is 45°, the principal shear stress in the layered surrounding rock reaches its maximum value26.

The deformations are less than 20 mm, or 2% of the tunnel width. Since the convergence of the surrounding rock mass is less than 2% of the tunnel diameter, this indicates that the serviceability of the tunnel is satisfactory for all layer dip angles3,27.

Effect of layer location on the stress relaxation factor

As expected, the settlement profile varies significantly with different layer locations. As shown in Fig. 10, the surface settlement is strongly influenced by the layer location. Figure 10a illustrates that when the layer is located at the center (i.e., L = 0), a relatively larger settlement of 25.99 mm is observed. Additionally, the settlement profile follows an unsymmetrical pattern. Such asymmetrical settlement is expected when a tunnel is excavated through inclined lithologies27. As shown in Fig. 10b–d, the settlement values are slightly higher on the right side than the left side of the tunnel center. This is because the rock mass on the right side has relatively lower quality compared to the left side.

Therefore, the value of λ decreases from 0.45 to 0.25 as the layer location shifts from the center to 2B above the tunnel. As the layer location moves from the center to 2B below the tunnel, the stress relaxation factor (λ) decreases from 0.45 to 0.3. This demonstrates that the optimal stress relaxation factor (λ) is highly influenced by the layer’s position. Thus, when the layer is located closer to the tunnel center, a higher stress relaxation factor (λ) is obtained, and vice versa.

Effect of layer locations on deformation of surrounding rock

The calculated displacements using the 2D CCM and 3D analysis for different layer locations are presented in Table 6. The maximum crown deformation of 71.4 mm occurred when the layer was located at the center of the tunnel. As the layer moves further above the tunnel, the crown deformation values decrease. This indicates that the influence of the layer on the deformations of the surrounding rock mass diminishes as the layer is positioned farther from the tunnel. Therefore, the maximum deformations at the crown, right side, and left side walls occur when the layer is at the center. As the layer moves further below the tunnel, the deformation values at the tunnel walls decrease.

As expected, the calculated deformations of the tunnel walls vary with different layer locations. For example, when the layer location changes from the center to 1B above the tunnel, the deformations at the crown, floor, left side, and right side are reduced by 57.7%, 3.59%, 41.39%, and 80.37%, respectively. This shows that the layer location has a significant effect on the deformation of the tunnel surrounding rock mass. Furthermore, when the layer location changes from 1B above to 2B above the tunnel, the total deformation at the selected key points (i.e., crown, floor, left side, and right side) decreases by 26.16%, 23.73%, 22.22%, and 24.46%, respectively. This indicates that as the layer moves farther above the tunnel, the deformation values at the selected key points continue to decrease.

Furthermore, when the layer location is changed from the center to 1B below the tunnel, the deformations at the crown, left side, and right side are reduced by 50.28%, 27.91%, and 78.25%, respectively. When the layer location is changed from 1B below to 2B below the tunnel, the total deformation at the selected key points (i.e., crown, floor, left side, and right side) is reduced by 9.58%, 9.21%, 15.48%, and 16.88%, respectively. These results demonstrate that the layer location significantly influences the convergence of the tunnel surrounding rock. Additionally, the effect of the layer on the deformations at the selected key points diminishes as the layer moves farther below or above the tunnel center.

As shown in Table 6, the total displacement predicted by the CCM and 3D methods yields very similar results. For example, for a layer located 2B above the tunnel center, the 2D analysis slightly underestimates the deformations at the crown, floor, left side, and right side by 7.17%, 8.0%, 17.34%, and 22.83%, respectively, with a maximum variation of 22.83% compared to the 3D analysis. For a layer located 1B above the tunnel center, the 2D analysis underestimates the deformations at the crown, floor, left side, and right side by 10.59%, 8.47%, 16.67%, and 13.67%, respectively. For the layer located at the center, the 2D analysis slightly overestimates the deformations at the floor, crown, left side, and right-side walls by 0.84%, 4.58%, 11.63%, and 1.69%, respectively. For a layer located 1B below the center, the 2D analysis overestimates the deformations at the crown, floor, and left and right sidewalls by 7.04%, 10.52%, 3.23%, and 3.89%, respectively.

In summary, the total displacements predicted by the 2D CCM and 3D methods are very close, with a maximum deformation variation of 22.83%. Finally, in all the considered layer locations (i.e., L = 2B and 1B above, center, 2B and 1B below the center), the maximum displacement values calculated using the 2D and 3D analyses are 72 mm and 71.4 mm, respectively. The deformations are less than 20 mm or 2% of the tunnel width. Since the convergence of the tunnel surrounding rock mass is less than 2% of the tunnel diameter, this indicates that the serviceability of the tunnel is satisfactory for all layer locations28.

Conclusion

In this paper, the 2D Convergence–Confinement Method (CCM) for analyzing tunnels in steeply dipping layered rock masses is evaluated through a comparison with the fully 3D numerical method. The study focuses on a tunnel located along the Awash-Kombolcha-Hara Gebeya railway route. The comparison between the 2D CCM and 3D simulations was conducted in terms of settlement profiles and tunnel convergence. The results indicate that, for an optimal value of the stress relaxation factor (λ), the tunnel convergence predicted by the CCM method agrees well with the 3D simulations. Therefore, the 2D CCM can be effectively applied to analyze tunnels in steeply dipping layered rock masses.

A parametric study was conducted to investigate the influence of layer dip angle and layer location on the corresponding value of the stress relaxation factor (λ) and the convergence of the tunnel surrounding rock mass. Both the 2D CCM and 3D numerical modeling were used in the parametric study. Based on the results obtained, the following conclusions can be drawn:

The optimum stress relaxation factor (λ) was found to be problem-dependent. The analysis shows that λ is influenced by the layer dip angle (β), with values increasing from 0.3 to 0.6 as the layer dip angle changes from 0° to 90°. Consequently, a higher stress relaxation factor is obtained for steeply dipping layered rock masses (i.e., β = 60° and 90°).

The convergence of the tunnel is also affected by the layer dip angle. The maximum deformation of 71.4 mm occurred when the layer dip angle was 45° at the crown of the tunnel wall. The second maximum deformation of 70.8 mm occurred for a layer dip angle of 45°.

The optimum stress relaxation factor is also influenced by the layer location. The value of λ decreased from 0.45 to 0.25 as the layer location moved from the center to 2B above the tunnel. When the layer is located farther from the tunnel center (i.e., 2B above or 2B below the tunnel), λ further reduces.

The results indicate that the deformation of the tunnel surrounding rock mass is directly related to the layer location. The maximum tunnel wall deformations occurred when the layer was positioned at the center of the tunnel.

The deformations predicted by the 2D CCM and 3D methods are very similar. The results show that, for an optimal value of λ, the tunnel convergence predicted by the CCM method agrees well with the 3D simulations. Therefore, the 2D CCM can be effectively applied to analyze tunnels in steeply dipping layered rock masses.

Data availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included in this article.

References

Zoppis, E., & Baldi, A.M. Gilgel Gibe II hydropower project in Ethiopia; TBM Tunnelling, when the rock turns into mud: Analysis of a major collapse, its causes and solutions. In: Geotechnical Aspects of Underground Construction in Soft Ground. CRC Press, pp 199–207 (2021).

Gebremeskel, N. H. & Gebregziabher, H. F. Developing guideline for risk management of tunnel construction in Ethiopia. Open J. Saf. Sci. Technol. 11, 171–183. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojsst.2021.114012 (2021).

Jilo, N. Z., Assefa, S. M. & Assefa, E. Numerical analysis of underground tunnel deformation: A case study of Midroc Lega-Dembi gold mine. Sci. Rep. 14, 7964. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-57621-x (2024).

Abate, S., Assefa, E. & Assefa, S. M. Analysis of the failure of Gilgel Gibe II hydropower head race tunnel using numerical approach. Model Earth Syst. Environ. 10, 497–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-023-01784-5 (2024).

Mishra, S., Mishra, A., Rao, K. S. & Gupta, N. K. Factors affecting crack length of a shallow tunnel under surface impact load. Indian Geotech. J. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40098-024-01018-0 (2024).

Duan, S. et al. Investigation on uncoordinated deformation and failure mechanism and damage modeling of rock mass with weak interlayer zone. Eng. Fail. Anal. 163, 108563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108563 (2024).

Do, N.-A., Dias, D., Oreste, P. & Djeran-Maigre, I. 2D tunnel numerical investigation: The influence of the simplified excavation method on tunnel behaviour. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 32, 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-013-9690-y (2014).

Panet, M. & Guenot, A. Analysis of convergence behind the face of a tunnel. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 20, A16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-9062(83)91744-8 (1983).

Karakus, M. Appraising the methods accounting for 3D tunnelling effects in 2D plane strain FE analysis. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 22, 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tust.2006.01.004 (2007).

Chang, L. et al. Limitation of convergence-confinement method on three-dimensional tunnelling effect. Sci. Rep. 13, 1988. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29062-5 (2023).

Wu, J.-H., Ohnishi, Y. & Nishiyama, S. Simulation of the mechanical behavior of inclined jointed rock masses during tunnel construction using Discontinuous Deformation Analysis (DDA). Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 41, 731–743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrmms.2004.01.010 (2004).

Man, J., Huang, H., Ai, Z. & Chen, J. Analytical model for tunnel face stability in longitudinally inclined layered rock masses with weak interlayer. Comput. Geotech. 143, 104608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compgeo.2021.104608 (2022).

Zhou, Y.-Y. et al. The failure mechanism and construction practice of large underground caverns in steeply dipping layered rock masses. En. Geol. 250, 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2019.01.006 (2019).

Xing, Y., Kulatilake, P. H. S. W. & Sandbak, L. A. Rock mass stability investigation around tunnels in an underground mine in USA. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 35, 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-016-0084-9 (2017).

Huang, G. et al. 3-D discontinuum numerical modeling of subsidence incorporating ore extraction and backfilling operations in an underground iron mine in China. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 27, 191–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmst.2017.01.015 (2017).

Rocscience 2004c (2024) Phase2 8.0. https://www.rocscience.com/software/rs2

Daraei, A. & Zare, S. Modifying tunnel’s hazard warning levels based on the laboratory studies on different rock types. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 23, 2384–2390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-019-0326-5 (2019).

Bierbaumer, A. Die Dimensionierung des Tunnelmauerwerkes : Studien

Svoboda, T., & Mašín, D. Convergence-confinement method for simulating NATM tunnels evaluated by comparison with full 3D simulations. In Proc Int Conf Undergr Constr Prague 795–801 (2010).

Itasca. 3DEC user’s manual (5.20) (2016).

Hoek, E., Kaiser, P. K. & Bawden, W. F. Support of underground excavations in hard rock (CRC Press, 2000).

Shreedharan, S. Stability investigations of tunnels in a coal mine in China through 3D-discontinuum numerical modeling and field deformation monitoring data. 165 (2016).

Protodyakonov, M.M. Determining of mechanical properties of rockso. In: Third International Conference Strata Control. Paris (1960).

Jingyuan, W. Numerical analysis on the stability of layered surrounding rock tunnel under the conditions of different inclination angle and thickness. Am. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 4, 67. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtte.20190402.14 (2019).

Do, N. A. et al. Behavior of noncircular tunnels excavated in stratified rock masses—Case of underground coal mines. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 11, 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrmge.2018.05.005 (2019).

Abdellah, W. R., Ali, M. A. & Yang, H.-S. Studying the effect of some parameters on the stability of shallow tunnels. J. Sustain. Min 17, 20–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsm.2018.02.001 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Deformation patterns and surface settlement trough in stratified jointed rock in tunnel excavation. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 23, 3188–3199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-019-0477-4 (2019).

Daraei, A. & Zare, S. Modified criterion for prediction of tunnel deformation in non-squeezing ground conditions. J. Mod. Transp. 27, 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40534-018-0173-y (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the anonymous reviewers who tried to improve this manuscript

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. E.A: Administration, conceptualization, supervision, methodology analysis, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review, and editing. K.T: Data curation, software, validation, methodology, investigation, writing-original draft, writing-review, and editing. S.M.A: Conceptualization, methodology analysis, software, investigation, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing-review, and editing. N.Z.J: Methodology analysis, investigation, software, formal analysis, writing–review and editing. L.P: Formal analysis, writing—review and editing. C.S: Formal analysis, writing—review and editing. The authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Assefa, E., Tilahun, K., Assefa, S.M. et al. Stability evaluation of tunnels in steeply dipping layered rock mass using numerical models: a case study. Sci Rep 15, 2046 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85704-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85704-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Stability Assessment and Pillar Design of Underground Drift in Opal-Bearing Rock Masses: A Case Study from Wollo Opal Mining, Ethiopia

Geotechnical and Geological Engineering (2026)

-

Experimental study on the effect of stress and water content on resilient modulus of unsaturated subgrade soil: implications for pavement design

Arabian Journal of Geosciences (2025)

-

Seismic Analysis of Cross-Tunnels in Jointed Weak Rock Using a DEM-DFN Approach

Geotechnical and Geological Engineering (2025)