Abstract

The extraction of coal seams with high gas content and low permeability presents significant challenges, particularly due to the extended period required for gas extraction to meet safety standards and the inherently low extraction efficiency. Hydraulic fracturing technology, widely employed in the permeability enhancement of soft and low-permeability coal seams, serves as a key intervention. This study focuses on the high-rank raw coal from the No. 13 coal seam at Xinjing Mine, utilizing a vacuum pressure saturation system, low-field nuclear magnetic resonance (LF-NMR) testing, and uniaxial compression mechanical testing to investigate the changes in porosity and connectivity of coal samples under conditions of high-pressure continuous immersion and high-low pressure cyclic immersion. Additionally, the uniaxial compression mechanical properties of the coal under various experimental conditions were analyzed. The findings reveal that the porosity of coal samples subjected to high-pressure continuous immersion and high-low pressure cyclic immersion initially decreases slightly before increasing as the immersion cycle progresses. The maximum porosity enhancements observed were 1.55% and 2.93%, respectively, while the total connectivity increased by 19.07% and 24.79%, respectively. Furthermore, The peak stresses of the coal samples were found to be 1.23–1.65 times, 1.65–3.21 times, and 1.56–4.24 times greater than those of the atmospheric-pressure continuous immersion, high-pressure continuous immersion, and high- and low-pressure cyclic immersion samples, respectively. The cyclic application of high and low confining pressures was shown to significantly promote the development of pore structures and enhance pore connectivity, leading to a more pronounced deterioration in coal body strength. These results provide a theoretical foundation and practical support for the application of hydraulic fracturing to improve permeability and the use of water injection to suppress gas outflow in coal seams with high gas content and low permeability within coal mines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coal, as a vital non-renewable resource, holds a significant share in the global energy mix. During mining and transportation, most coals encounter issues related to repeated cyclic water immersion1. During the mining of high gas content and low permeability coal seams, hydraulic fracturing technology is routinely employed to enhance the permeability of the coal seams2. This technique involves the injection of high-pressure fluids to create fractures within the coal, thereby facilitating gas extraction. Elastic mechanics, which pertains to the study of stress, deformation, and displacement in elastic solids under external forces or temperature changes, is utilized to analyze the mechanical behavior of the coal matrix3. The double effective stress theory in porous media is applied to account for the distinct effective stresses acting within the coal’s porous structure, which is crucial for understanding the mechanical interactions between the solid matrix and the fluid within the coal’s pores4. Furthermore, systematic guidelines encompassing various fracture expansion modes provide a structured approach to studying how fractures initiate and propagate within the coal seam5. These interdisciplinary methodologies collectively contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the coal’s mechanical properties and the evolution of its pore structure, which are critical factors in the efficiency of mining operations and gas recovery6. This process notably affects the mechanical properties and pore structure of coal bodies, particularly during the extraction of high gas and low permeability coal seams and when employing hydraulic fracturing technology to enhance coal seam permeability7. Currently, in coal mining operations, scenarios such as water drainage from the overlying goaf5, water-retaining coal seam mining8, and water injection for fire area sealing in the mining district9,10, also involve cyclic water immersion of coal masses. The impact of such immersion on the coal’s mechanical properties and pore structure can lead to the development of fractures in the goaf area and an intensification of spontaneous combustion phenomena11,12.

Coal rock, an intricate discontinuous and heterogeneous porous medium, exhibits physical and chemical properties that are significantly influenced by water. Numerous scholars worldwide have examined the effects of water on the physical, chemical, and mechanical characteristics of coal from various perspectives. It is widely accepted that water exerts a lubricating13, softening14, and erosive15effect on coal, leading to the expansion and softening of saturated coal16,17, a decrease in mechanical strength18,19, and the dissolution of inorganic minerals and organic humic substances within the coal matrix. These processes contribute to the secondary evolution of the coal’s pore structure20,21.

Pi et al.22 conducted experimental research on the evolution of mesopores, macropores, and microcracks within the coal matrix during the water immersion process. Wang et al.23 utilized three-dimensional scanning to elucidate the impact of water immersion duration on the morphology of rock discontinuities, revealing that immersion time significantly influences the development of these features. Wang et al.24 discovered that the hydration of minerals can induce localized stress concentrations and that the associated swelling due to water absorption fosters the propagation of microcracks within shale formations. Qin et al.25 employed computed tomography (CT) scanning and three-dimensional reconstruction to investigate the mechanical damage and pore evolution in granite subjected to cyclic water immersion, demonstrating a positive correlation between the number of cycles and both surface and non-closed surface porosity, while observing an initial increase followed by a decrease in closed surface porosity. Zhu et al.26 through a water-soaking and drying cycle experiment, observed disintegration in all tested rock samples, with the conductivity of the soaking solution increasing rapidly at first and then stabilizing over time. Li et al.27 examined the relationship between the mechanical damage of water-saturated granite, its water saturation level, and the distribution of thermal conductivity using optical scanning and mechanical testing, suggesting that thermal heterogeneity within the rock is markedly reduced upon saturation. Lu et al.28 applied an electro-hydraulic servo-controlled testing system to assess the uniaxial compression and water absorption properties of sandstone and mudstone, determining the relationship between their saturated water content and water temperature and finding that while water temperature inhibits water absorption in sandstone, it enhances it in mudstone. Additionally, water immersion had no significant effect on sandstone fracture development but promoted mudstone fracture evolution. Jia et al.29 utilized nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) experiments to assess the distribution of bound water, capillary water, and gravitational water within sandstone during the freezing of pore water at varying degrees of saturation. In the context of mining high gas content and low permeability coal seams, hydraulic fracturing technology is frequently implemented to enhance the permeability of the coal seams. A multitude of scholars globally have employed experimental methodologies such as Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) tests, Computed Tomography (CT) scans, and electro-hydraulic servo control tests to conduct in-depth studies on the fine structure, mechanical properties, and thermal conductivity changes of the submerged coal body. However, there has been a relative dearth of research focusing on the submerged pressure of the coal body, particularly the effects of high- and low-pressure cycling.

Elevated water content and increased cycling between wet and dry conditions under various experimental settings exert varying degrees of influence on key mechanical parameters of coal samples. These include porosity16,30,31, elastic modulus32,33, electrical resistivity34, uniaxial and triaxial compressive strength35,36,37, angle of internal friction38, shear strength39, cohesive force40, and tensile strength41,42. Yao et al.43 explored the variation in mechanical properties of coal and rock with different moisture contents, proposing optimal dimensions for coal pillar dams in underground reservoirs within coal mines. Zhou et al.44 utilized mechanical property and acoustic emission tests to demonstrate that the mechanical properties of coal samples are significantly weakened with increasing water content. Zhang et al.45 employed acoustic emission testing to investigate the damage mechanisms of coal samples under compressive stress during water immersion. Gao et al.46 conducted studies on the mechanical characteristics of water-saturated coal, including stress-strain behavior, triaxial compression, and responses to cyclic loading. Lai et al.47 examined the evolutionary mechanisms of coal and rock softening and damage from the perspective of hydro-mechanical coupling. Wang et al.48 and Li et al.49 developed damage constitutive models based on the deformation and damage parameters of coal samples with varying water contents. Cai et al.50 analyzed the structural damage characteristics and acoustic emission patterns of coal samples during triaxial compression tests under saturated conditions. However, the existing literature on submerged coal bodies predominantly focuses on the mechanical damage models associated with dry and wet cycling. To date, scant attention has been directed towards the mechanical damage and degradation effects induced by cyclic high- and low-pressure variations within the coal matrix.

In this study, we conducted high and low pressure cyclic water immersion experiments to investigate the impact of such pressure cycling on the coal body’s pore structure, connectivity, and mechanical damage characteristics. Our primary focus was on understanding how the cyclic exposure to high and low peripheral pressures affects the coal’s pore structure and the degradation of its strength. This research aims to provide a theoretical foundation for the drilling hydraulic fracturing of high gas and low permeability coal seams, which is crucial for enhancing the penetration and water injection efficiency into the drilling holes, thereby inhibiting the gas outflow from coal seams in coal mines.

Experimental materials and methods

Experimental materials and sample preparation

The experimental coal specimens were sourced from the high-rank raw coal of the No. 13 coal seam at Xinjing Mine, characterized as a medium-ash, low-sulfur, and low-phosphorus high-rank anthracite. The industrial analysis of these coal samples, conducted in compliance with the GB/T212-2008 standard for “Methods of Industrial Analysis of Coal”, is detailed in Table 1.

Freshly obtained large coal samples were carefully wrapped in plastic food wrap and transported to the laboratory. Upon arrival, the coal surface was meticulously stripped, followed by precision cutting and polishing using a multifunctional jade carving machine to achieve a uniform dimension of 20 mm × 20 mm × 20 mm. Only samples with a smooth surface, free from fissures, and exhibiting a regular geometric shape were selected for subsequent experimental analysis.

Selection of coal samples

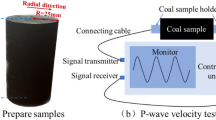

To mitigate the impact of sample-to-sample variability on the stability of subsequent experimental outcomes, a two-step selection process was implemented. Initially, coal samples were visually inspected to confirm adherence to standard cubic dimensions and the absence of apparent surface fissures. Subsequently, all dried specimens underwent ultrasonic wave velocity testing using a sonic detector (RSM-SY6 model, Wuhan Zhongyan Science and Technology Co., Ltd., China). This procedure is essential as it accounts for internal structural irregularities; specifically, when significant voids or fissures are present within a specimen, the ultrasonic pulse must circumnavigate these, leading to an extended propagation path and a consequent reduction in wave velocity. The internal homogeneity assessment results for the coal samples are depicted in Fig. 1. The velocities were predominantly found within the range of 1.767 to 2.288 km/s, with an overall average of 1.933 km/s. Specimens exhibiting wave velocities within a narrow band of 1.933 ± 0.06 km/s were selected. This criterion ensures that, macroscopically, the internal inconsistencies among samples with closely matching velocities are minimal, thereby guaranteeing the stability and rationality of the ensuing.

Methodology

Experimental setup and apparatus

The experimental apparatus comprises a Newmark low-field nuclear magnetic resonance (LF-NMR) testing system, a temperature-controlled drying unit, an acoustic emission (AE) monitoring system, a uniaxial compression mechanical testing system, and a vacuum-assisted water saturation setup. A schematic representation of the experimental apparatus is depicted in Figs. 2 and 3 illustrates some of the experimental coal samples and equipment.

Experimental procedure

To elucidate the effects of cyclic high and low-pressure water immersion on the pore structure and mechanical properties of coal, in this study, we conducted experiments simulating high and low pressure cyclic water injection to fracture the coal body. Our focus was on assessing the influence of cyclic pressure variations on the coal’s pore structure, connectivity, and mechanical damage characteristics. We aimed to elucidate the impact of high and low peripheral pressure cycling on the coal body’s pore structure and the degradation of its strength. These findings are instrumental in providing a theoretical foundation for the drilling hydraulic fracturing of high gas and low permeability coal seams. Enhancing the penetration and water injection efficiency into the drilling holes is crucial for mitigating gas outflow from coal seams in coal mines, thereby enhancing safety and operational support. The process commenced with the selection of coal samples, followed by cyclic saturation at pressures of 2.5 MPa (low pressure) and 8 MPa (high pressure)5, and subsequent testing using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) and Uniaxial Compressive Strength (UCS). It should be noted that, due to experimental constraints, the NMR and UCS analyses were conducted off-site. The detailed experimental steps are as follows:

-

1.

Coal samples were labeled (M1 to M13) and their initial masses were recorded. The pristine coal sample (M1) was directly tested, while the remaining samples (M2 to M13) were placed in an electric heat blast drying oven at 100 °C for 12 h to ensure thorough drying, after which their masses were re-evaluated.

-

2.

The dried coal samples were then placed into a vacuum-assisted saturation device, where a vacuum pressure of −0.1 MPa was maintained for 12 h.

-

3.

Following vacuum treatment, the samples were subjected to pressure saturation within the device at 8 MPa for 24 h, followed by 2.5 MPa for an additional 24 h, constituting one cycle of high and low-pressure water immersion. This cycle was repeated four times for the samples designated as HL1 to HL4. An alternative cycle, involving 48 h at 8 MPa, was also executed four times for the samples labeled H1 to H4. In addition, atmospheric pressure water immersion saturation was conducted for 48 h, constituting one cycle of atmospheric pressure water immersion. The experiment was repeated for a total of four cycles, corresponding to the coal samples designated as Atm1 to Atm4, respectively.

-

4.

After saturation, the surface moisture of the samples was carefully wiped off, and they were then subjected to NMR testing and uniaxial compression mechanical testing. These tests provided data on the initial T2 spectra, porosity, and complete stress-strain curves under varying cyclic saturation pressures.

-

5.

The water-saturated coal samples, under different pressure conditions, were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 90 min to consolidate the effects of the immersion cycles.

-

6.

Post-centrifugation, the samples were re-evaluated using NMR to ascertain the T2 spectra and porosity parameters, offering further insights into the coal’s structural integrity.

Results and discussion

Analysis of T2 spectra

Employing a porosity standard sample with the Newmark low-field Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (LF-NMR) testing system and applying a 5-point calibration method, we established a calibration curve correlating NMR signal intensity with porosity. The correlation coefficient (R²) of 1 demonstrates the system’s capability to objectively and precisely measure parameters associated with the pore structure of the coal samples, as depicted in Fig. 4.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) testing primarily utilizes time-domain NMR to ascertain the distribution of signal relaxation times, thereby extracting molecular interactions as physical insights. The experimental setup in question is designed to characterize the pore size and distribution within water-saturated coal samples by assessing the transverse relaxation time (T2) distribution of water within the coal’s pores. The correlation between the transverse relaxation time and the pore radius of the coal samples is delineated by the following Equation22 :

Where is the transverse relaxation time (ms), is the transverse surface relaxation strength (μm/ms), S is the pore surface area (μm2), V is the pore volume (μm3), FS is the pore shape factor (spherical pore, FS = 3, columnar pore, FS = 2, and fissure, FS = 1), r is the pore diameter in nanometers (nm).

Thus, the relationship between the coal sample’s pore diameter and transverse relaxation time (T2) is delineated by the subsequent equation:

Where \(\alpha\) is the conversion coefficient, \(\alpha =\rho {F_S}\).

The T2 relaxation time distribution of saturated coal samples, following water immersion at atmospheric pressure, cyclic high pressure, and low pressure, provides a comprehensive characterization of the internal pore structure and connectivity of the coal samples. The area under the distribution curve and the horizontal axis, along with the number and width of the peaks, serve as key parameters that delineate the distribution and connectivity of the coal’s internal pore structure. The longitudinal relaxation time (T2) is directly proportional to the size of the internal pores, with longer T2 values indicating larger pore sizes within the coal matrix. In comparison to the processes of high-pressure water immersion and high-low-pressure cyclic water immersion, the porosity of coal samples subjected to one to four cycles of atmospheric pressure water immersion was found to be 12.82%, 13.01%, 13.12%, and 13.13%, respectively. The water immersion process influences the absorption, expansion, and softening of the coal skeleton, as well as the dissolution and precipitation of organic and inorganic minerals within the coal, leading to a trend of decreasing and then increasing coal pore ratio. However, the effect of atmospheric water immersion on the experimental coals was not significant, and the impact of low-pressure water immersion on the pore size of the internal pore structure of the coal body was also found to be non-significant. Concurrently, the effect of low-pressure water immersion on the structure of the coal body is minimal, with changes being relatively stable and its pattern of change is fundamentally consistent with the laws observed in previous studies22. Therefore, this study primarily discusses the effects of high-pressure and cyclic water immersion on the structure of the coal body. The distribution curves of coal samples after saturation under different experimental conditions are depicted in Fig. 6.

Figure 6 reveals that during both high-pressure and cyclic high-low pressure water immersion processes, the porosity of the coal samples initially decreases slightly before increasing. The respective increases in porosity are 1.55% and 2.93%. Post the first cycle of high-pressure and cyclic high-low pressure immersion, as depicted in Fig. 6(a) and 6(b), the original coal exhibits a higher overall porosity compared to the experimental samples. This suggests that during the initial phase of water immersion, dissolution and precipitation of inorganic minerals, organic matter, and fine dust particles occur, while water gradually softens the coal matrix. The high-pressure immersion also intensifies the fracturing and compaction of the coal structure, leading to a minor reduction in pore volume, particularly within the smaller pores. As the experimental immersion progresses, as shown in Fig. 6(c), 6(d), 6(e), and 6(f), the coal’s pore connectivity is enhanced further due to water influence, with some small pores transforming into medium to large pores, thus causing the porosity to follow a pattern of initial decrease followed by an increase. The cyclic high-low pressure immersion exerts fatigue damage on the coal structure due to the varying pressure, which, in conjunction with the softening effect of water, reduces the stiffness and increases the plasticity of the coal samples. The static dissolution and dynamic material transport within the coal body alter its physical and mechanical properties to some extent. Under the coupled influence of multiple factors, the re-development of coal’s pore fractures is further facilitated, as illustrated in Fig. 6(g) and 6(h), where a minor development of macroporous structures is evident. This indicates that multiple cycles of high-low pressure water immersion, compared to continuous high-pressure immersion, significantly enhance the flexibility of the coal and more extensively trigger the destruction and development of pore fractures through plastic deformation under mechanical fatigue.

Comparative T2 relaxation time distribution of saturated coal samples following cyclic high and low pressure immersion (Figures a through h depict the T2 relaxation profiles of samples H1, HL1, H2, HL2, H3, HL3, H4, and HL4, respectively, compared to the control group M1, following saturated water immersion).

Analysis of pore connectivity

The total porosity of coal includes certain enclosed pore structures within the coal matrix, which do not adequately represent the connectivity among the various pores. Utilizing the principles of low-field nuclear magnetic resonance (LF-NMR), this study conducts an analysis of the coal’s pore connectivity under diverse experimental conditions (Pi, et al., 2022). The connectivity ratio is calculated using the equation provided below:

Where \({C_{{r_1}\sim {r_2}}}\) is the connectivity rate for pore size \([{r_1},{r_2}]\); \({V_{\text{t}}}\) is the total pore volume for pore size \([{r_1},{r_2}]\); and \({V_c}\) is the closed pore volume for pore size \([{r_1},{r_2}]\).

Following regression analysis, the permeability of the coal samples was determined using a free-fluid model suitable for the characterization of coal rock. The permeability (k) is calculated according to the subsequent equation:

Where k is the permeability of coal samples post-regression analysis; \(T_{{{\text{2gm}}}}^{{\text{b}}}\) is the geometric mean value of T2 during the residual water state of the coal samples; \({\varphi _{\text{e}}}\) is the proportion of connected pores and the effective porosity; \({\varphi _{\text{r}}}\) is the proportion of closed pores and the residual porosity of the coal samples.

The connectivity of various pore segments in the coal samples under different experimental conditions is presented in Table 2.

Table 2 indicates that the overall pore connectivity for raw coal samples is 38.07%. For coal samples subjected to continuous high-pressure immersion, the connectivity rates for micropores range from 8.23 to 35.85%, for small pores from 96.77 to 99.26%, for medium pores from 97.93 to 100%, and for large pores, it is consistently 100%. The total connectivity in these samples varies from 37.11 to 56.18%, marking an increase of 19.07%. In the case of coal samples undergoing cyclic high and low-pressure immersion, the connectivity for micropores extends from 8.11 to 40.67%, for small pores from 97.43 to 99.78%, for medium pores from 98.87 to 100%, and for large pores, it remains at 100%. The total connectivity in these samples ranges from 37.46 to 62.25%, reflecting an increase of 24.79%. Notably, medium and large pores exhibit the highest connectivity rates, with large pores consistently reaching 100%.

As the immersion cycles progress and the confining pressure around the coal body increases, the total connectivity of both continuously high-pressure soaked and cyclic high-low pressure soaked coal samples initially decreases and then increases. This trend is primarily attributed to the initial absorption and expansion of the coal matrix under high pressure, leading to a reduction in pore volume or blockage, and consequently, a decrease in porosity and connectivity, most notably within the micropores. However, with ongoing immersion cycles, the combined effects of internal dissolution, dynamic material transport, and the confining pressure of the immersion water promote the fracturing of the coal’s pore framework. This leads to an enlargement of the pore volume and an enhancement of connectivity.

The impact of cyclic high and low-pressure immersion on the coal body’s connectivity is significant, further substantiating that such cyclic pressure variations have a more pronounced effect on the degradation of coal body strength. The relationship between the total pore connectivity and permeability of the water-saturated coal samples under various experimental conditions is depicted in Fig. 7.

As depicted in Fig. 7, the total pore connectivity in coal samples exhibits an exponential relationship with permeability. The functional relationships for the high-pressure immersion process and the high-low-pressure cyclic immersion process are given by the equations \(y=5.634 \times {e^{\frac{x}{{0.231}}}}+28.985\) and \(y=2.108 \times {e^{\frac{x}{{0.167}}}}+34.982\), respectively, the corresponding coefficients of determination (R²) are 0.971 and 0.848, indicating a strong correlation. The permeability of the coal samples increases with greater total connectivity, demonstrating that the permeability of the coal is positively correlated with the connectivity of its pore structure. This suggests that the connectivity of the coal matrix can serve as a direct indicator of the coal’s permeability.

Analysis of uniaxial compressive strength

Figure 8 presents the complete stress-strain curves for raw coal, high-pressure continuous immersion, and high- and low-pressure cyclic immersion coal samples, revealing significant differences between the raw coal samples and those subjected to various immersion conditions. The stress-strain curve of the raw coal samples exhibits a rapid increase, with a peak stress of 19.5334 MPa, which is 1.23–1.65 times that of the peak stress observed in coal samples under atmospheric pressure continuous immersion, 1.65–3.21 times that of the peak stress under high-pressure continuous immersion, and 1.56–4.24 times that of the peak stress under high- and low-pressure cyclic immersion. Within the stress-strain curves of coal samples under diverse experimental conditions, the stress-strain rate of the coal samples increases with the increment of the water immersion cycle.

A comparative analysis of the peak stresses in the stress-strain curves of coal samples with cyclic high and low-pressure water immersion is depicted in Fig. 9. From Fig. 9, it is evident that the peak stresses of the experimental coal samples exhibit a progressive decrease with the increase in the water immersion cycle. Specifically, the peak stresses of the atmospheric pressure continuous immersion coal samples were 15.9049, 14.7106, 12.7491, and 11.8512 MPa, representing reductions of 18.5755%, 24.6898%, and 34.7321%, respectively, compared to the original coal samples. The peak stresses of the high-pressure continuous flooding samples were 11.8104, 9.0814, 7.9265, and 6.0892 MPa, which are 39.5372%, 53.5086%, 59.4207%, and 68.8265% lower than those of the original coal samples, respectively. The peak stresses of the high- and low-pressure cyclic flooding samples were 12.5028, 9.0104, 6.6606, and 6.6606 MPa, which are 35.9927%, 53.8717%, 66.1407%, and 76.4356% lower than those of the original coal samples, respectively.

During the initial stages of immersion, the peak stress of high and low-pressure cyclic immersion was greater than that of high-pressure continuous immersion. However, with the increase in the immersion cycle, the peak stress of high-pressure continuous immersion gradually became larger than that of high and low-pressure cyclic immersion. This indicates that the fatigue damage effect of high and low-pressure cyclic immersion is more pronounced than that of the high-pressure continuous immersion process on the coal skeleton, leading to further deterioration of the coal body’s strength. The peak stress of the original coal samples decreased by 35.9927%, 53.8717%, 66.1407%, and 76.4356%, respectively, compared to the atmospheric pressure immersion samples. The peak stress of the original coal samples is only 1.23–1.65 times that of the atmospheric-pressure immersion samples, suggesting that atmospheric-pressure immersion has a certain softening degradation effect on the coal body, but the degree of degradation is limited. This further confirms that high and low-pressure cyclic action significantly affects the fatigue damage of the coal body, which has a positive impact on the enhancement of coal seam penetration and coal seam gas extraction.

This trend suggests that the cyclic high-low-pressure immersion process induces more pronounced fatigue damage to the coal matrix, leading to a more significant degradation of coal strength. Such effects may have positive implications for enhancing coal seam permeability and facilitating coalbed methane extraction.

The calculations for the modulus of elasticity and the strain softening modulus of the coal samples are presented by the following equations:

Where \({E_x}\) is the calculation of the elastic (strain softening) modulus (MPa), \({\sigma _1}\) and \({\sigma _2}\) are the elastic modulus and the strain softening modulus correspond to the initial and final stress values in the linear phase, respectively (MPa), \({\varepsilon _1}\) and \({\varepsilon _2}\) are the respective values refer to the initial and final strain values at the beginning and end of the linear phase.

Figure 10 delineates the influence of atmospheric pressure immersion and cyclic high and low-pressure immersion on the elastic modulus of coal samples. As inferred from Fig. 10, it is evident that the increment in the number of immersion cycles significantly affects the elastic modulus of the experimental coal samples, with a negative exponential relationship observed. The relationship between the number of immersion cycles and the elastic modulus of the coal body for atmospheric pressure immersion, high-pressure continuous immersion, and high- and low-pressure cyclic immersion can be characterized by the following functions, respectively: \(y=1540.734 \times {e^{\frac{{ - x}}{{0.871}}}}+1145.911\), \(y=1816.285 \times {e^{\frac{{ - x}}{{0.961}}}}+655.338\) and \(y=3293.669 \times {e^{\frac{{ - x}}{{0.944}}}}+408.058\),

the correlation coefficients (R²) were determined to be 0.999, 0.999, and 0.996, respectively, indicating a very strong fit between the variables being studied. It is observed that with an increase in the cycle of water immersion, the elastic modulus of the coal body exhibits a significant negative exponential decline. This suggests that the degradation of the coal body skeleton due to water immersion is somewhat limited under atmospheric pressure, resulting in a relatively minor impact on the elastic modulus of the experimental coal body, with a reduction of only 28.591%. In contrast, the cyclic high and low-pressure water immersion has a more pronounced effect on the elastic modulus of the coal body, with reductions of 47.257% and 71.579%, respectively. This indicates that the weakening effect on the modulus of elasticity of the coal body is more substantial than that of high-pressure continuous water immersion, which saw decreases of 47.257% and 71.579%, respectively. The results are consistent with the full stress-strain peak stress comparison structure of the cyclic high- and low-pressure waterlogged coal samples. This further suggests that the water immersion process has effects of lubrication, softening, and scouring of inorganic minerals, organic matter, and structural surfaces within the coal body, leading to further deterioration of the skeletal structure of the coal body and a decrease in the mechanical properties of the coal and rock body. High-pressure continuous water immersion and high-low-pressure cyclic water immersion processes cause deformation and destruction of the coal body’s skeletal structure under pressure, leading to a redevelopment of the coal body’s pore structure, with the deterioration being more significant in the high-low-pressure cyclic water immersion process.

Damage mechanisms of coal bodies Induced by circulating high- and low-pressure leaching water

Coal body strength is influenced by a multitude of factors, including internal particle size, pore and cleavage structure, mineral composition, and the surrounding environment, all of which exhibit characteristics of random variables. Consequently, the strength of coal bodies subjected to cyclic high and low-pressure water immersion experiments adheres to the Weibull analytical law, a statistical model widely recognized for its ability to describe the strength distribution of materials51. The probability density function (PDF) that describes this distribution is given by the Weibull distribution formula:

Where m is the response characteristic of the coal-rock body to the external load; F is the characterization parameter of the Weibull distribution, and \(\varepsilon\) is the stress variable of the coal body.

The experimental coal body, when subjected to cyclic high and low-pressure water immersion, experiences gradual deformation and damage at the micro-element level. This damage can be effectively characterized by statistical damage variables. The evolution equation of the statistical damage for the experimental coal body is as follows:

Where D is the degree of damage within the experimental coal body.

Coal, as a complex porous medium characterized by high heterogeneity and anisotropy, exhibits variations in the internal expansion rates of coal particles following water immersion52. These variations can lead to differential expansion, potentially inducing shear and tensile stresses between adjacent coal particles. The coefficients of water-absorption and expansion (β) may also vary among neighboring coal particles, further complicating the stress distribution within the coal body. The expansion stress (\({\sigma _s}\)), which arises from this differential expansion, can be quantified using the following equation:

Where α is the stress conversion factor caused by expansion; β1 and β2 are the expansion coefficients of neighboring coal particles and β1 > β2; \({V_f}\) is the amount of liquid absorbed by the experimental coal body under pressure p, calculated as follows:

Where \({V_f}\) is the amount of liquid absorbed by the experimental coal body under pressure p, m3; S is the saturation degree of the experimental coal body, %; \(\phi\) is the porosity of the experimental coal body, %; \({V_t}\) is the total volume of the experimental coal body, m3.

By substituting Eq. (9) into Eq. (8), we obtain the following result:

In accordance with Griffith’s criterion for material fracture53, the tensile stress (\({\sigma _{tn}}\)) necessary to initiate a new crack surface in an experimental coal body after undergoing n cycles of high and low pressure immersion is given by:

Where, \(\gamma\) is the surface energy of the experimental coal body per unit length of the cleft, J/m2; \({E_n}\) is the modulus of elasticity of the experimental coal sample after n times of high and low pressure cycles of water immersion, MPa; C is half of the length of the cleft, m.

The experimental coal body, when subjected to cyclic high and low-pressure water immersion, experiences progressive fatigue damage to its skeletal structure. Consequently, the elastic modulus (\({E_n}\)) of the experimental coal body decreases with an increasing number of water immersion cycles. Drawing upon damage theory54, the elastic modulus of the coal after n cycles of high- and low-pressure cyclic water immersion can be determined using the following formula:

Where \({E_0}\) is the initial modulus of elasticity, MPa.

Substituting Eqs. (6) and (12) into Eq. (11) yields:

It has been observed that as the number of high and low pressure cyclic water immersions on experimental coal samples increases, the tensile stress required to initiate new fissures within the coal body progressively diminishes. Upon completion of n cycles of such immersion, \({\sigma _s}>{\sigma _{tn}}\), the formation of new fissures within the coal body is anticipated, with the potential for existing pores and fissures to interconnect. Concurrently, the cyclic high- and low-pressure water immersion process may facilitate the dissolution or removal of organic and inorganic minerals from within the coal body’s pore space, thereby promoting porosity development. The experimental data presented in Table 2; Fig. 9 corroborate these findings, demonstrating the evolution of coal body integrity under cyclic water immersion conditions.

Conclusion

This study investigates the impact of cyclic high and low-pressure water immersion on the pore structure of coal using low-field nuclear magnetic resonance (LF-NMR) and uniaxial compressive strength testing. The principal findings are summarized as follows:

-

1.

Relative to the original coal samples, the porosity of samples subjected to normal pressure continuous immersion, high pressure continuous immersion, and high and low pressure cyclic immersion exhibited a minor decrease followed by an increase with the progression of immersion cycles. The porosity values for these samples ranged from 12.82 to 13.13%, 12.60–14.45%, and 12.70–15.83%, respectively, with maximum increases of 0.31%, 1.55%, and 2.93%. The impact under atmospheric pressure immersion was not significant. However, compared to high pressure continuous immersion, the cyclic high and low peripheral pressure action had a more pronounced effect on the fatigue damage to the coal body skeleton. In the context of water immersion, the effect was not markedly different, but the fatigue damage induced by the cyclic action of high and low peripheral pressure on the coal body skeleton was more substantial. This damage further reduced the stiffness of the coal samples, enhanced the plasticity of the coal samples, increased the flexibility of the coal body, and triggered a more extensive destruction and development of the pore fissures through the mechanical fatigue action associated with plastic deformation.

-

2.

The water immersion process significantly improved the pore connectivity of the coal samples. The total pore connectivity for samples under high-pressure continuous and high-low-pressure cyclic water immersion increased by 19.07% and 24.79%, respectively. The cyclic pressure variation was more effective in promoting pore structure development and connectivity, leading to a more pronounced degradation in coal strength. The total pore connectivity of both high-pressure and high-low-pressure immersed coal samples correlated exponentially with permeability, indicating that coal body connectivity directly reflects permeability.

-

3.

It has been observed that the peak stresses of raw coal samples are significantly higher than those of samples subjected to different immersion conditions. Specifically, the peak stresses of the raw coal samples are 1.23–1.65 times, 1.65–3.21 times, and 1.56–4.24 times greater than those of samples under atmospheric pressure continuous immersion, high-pressure continuous immersion, and high and low-pressure cyclic immersion, respectively. With an increasing number of immersion cycles, there is a continuous decrease in the peak stress of the experimental coal samples. The cyclic high and low-pressure immersion process exerts a more pronounced fatigue damage effect on the coal body skeleton compared to the high-pressure continuous immersion process. This differential effect is further emphasized by the negative exponential relationship between the soaking cycles of atmospheric pressure continuous immersion, high-pressure continuous immersion, and high and low-pressure cyclic immersion with the elastic modulus of the coal body. Notably, the cyclic high and low-pressure immersion has a more significant impact on the weakening of the coal body’s elastic modulus than the high-pressure continuous immersion. The results are similar to the full stress-strain peak stress comparison structure of cyclic high and low pressure immersion coal samples.

-

4.

A comprehensive mechanism of damage to the coal body due to cyclic high- and low-pressure water immersion has been proposed, which elucidates and substantiates the secondary development of pore and fissure structures and the mechanical deterioration observed in experimental studies. In the context of drilling hydraulic fracturing operations aimed at enhancing penetration and inhibiting gas outflow from coal beds, particularly in high gas and low permeability coal mines, the impact of water pressure on the coal body’s pore structure and its connectivity must be taken into account. The cyclic high- and low-pressure immersion has been found to be more efficient and significant in weakening the coal body’s elastic modulus and affecting its pore structure and connectivity compared to sustained high-pressure conditions. This understanding is crucial for optimizing drilling practices and enhancing gas extraction efficiency in coal seams with low permeability.

Data availability

The data presented in the article originates from research projects conducted within the national key laboratory. While this information is not intended for public dissemination, it can be accessed upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author.

References

Zhang, G., Wang, E., Liu, X. & Li, Z. Research on risk assessment of coal and gas outburst during continuous excavation cycle of coal mine with dynamic probabilistic inference. Process. Saf. Environ. Prot. 190, 405–419 (2024).

Bao, J. et al. A fully coupled and full 3D finite element model for hydraulic fracturing and its verification with physical experiments. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 114, 92–100 (2019).

WANG, S., XIA, Y. & JIN Y., TAN P., & Experimental investigation on hydraulic fracture propagation of coal shale reservoirs under multi-gas co-production. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 44 (12), 2290–2296 (2022).

Zhang, H., Xu, W. & Liu, Y. Numerical simulation of hydraulic fracturing in low-permeability coal seams considering the effect of coal matrix shrinkage. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 67, 103758 (2019).

Xu, N., Bian, L., Fang, S., Wang, D. & Chen, L. Research on the prevention and control effect of hydraulic fracturing pressure unloading in deep strong pressure working face. CEEP 46 (1), 250–258 (2024).

Niu, H. et al. Study on pore structure change characteristics of water-immersed and air-dried coal based on sem-bet. Combust. Sci. Technol. 195 (16), 3994–4016 (2023).

Yi, S. et al. Study on the instability activation mechanism and deformation law of surrounding rock affected by water immersion in goafs. Water 14 (20), 3250 (2022).

Li, M., Zhang, J., Deng, X., Zhou, L. & Zhang, Q. Solid filling water retention mining methods and applications under aquifers. J. China Coal Soc. 42 (1), 127–133 (2017).

Bu, Y. C., Niu, H. Y., Qiu, T., Yang, Y. X. & Sun, L. L. Analysis of stage parameters of low-temperature oxidation of water-soaked coal based on kinetic principles. Sci. Total Environ. 946, 173947 (2024).

Sun, X. et al. Dynamic mechanical response and failure characteristics of coal and rock under saltwater immersion conditions. Sci. Rep. 14 (1), 11869 (2024).

Han, P. et al. Characteristics of progressive damage and damage ontology modeling of coal samples under long-term waterlogging effects. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 43 (4), 918–933 (2024).

Zhang, L., Wen, C., Li, S. & Yang, M. Evolution and oxidation properties of the functional groups of coals after water immersion and air drying. Energy 288, 129709 (2024).

Ma, S., Zhang, Q., Cao, J. & Xue, S. Study on the influence of gas desorption characteristics of different coal bodies under hydraulic permeability enhancement. Appl. Sci. 13 (21), 11648 (2023).

Hu, D., Zhang, F., Shao, J. & Gatmiri, B. Influences of mineralogy and water content on the mechanical properties of argillite. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 47 (1), 157–166 (2014).

Li, B. et al. Multi-source information fusion technology for risk assessment of water inrush from coal floor karst aquifer. Geomat. Nat. Haz Risk. 13 (1), 2086–2106 (2022).

Yao, Q. et al. Mechanisms of failure in coal samples from underground water reservoir. Eng. Geol. 267, 105494 (2020).

Niu, Y. et al. Experimental study on the characterization of coal electrical parameters under the conditions of water immersion and heating. China Saf. Sci. J. 30 (9), 37–42 (2020).

Yin, D. et al. Experimental study on mechanical properties of pressure waterlogged coal rock considering initial damage. J. China Coal Soc. 48 (12), 4417–4432 (2023).

Yi, X., Ge, L., Zhang, S. & Deng, J. Oxidation characterization of waterlogged coal based on the indicator gas method. Coal Sci. Technol. 51 (3), 130–136 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Effects of water soaked height on the deformation and crushing characteristics of loose gangue backfill material in solid backfill coal mining. Processes 6 (6), 64 (2018).

Song, S., Qin, B., Xin, H., Qin, X. & Chen, K. Exploring effect of water immersion on the structure and low-temperature oxidation of coal: a case study of Shendong long flame coal, China. Fuel 234, 732–737 (2018).

Pi, Z. et al. Low-field NMR experimental study on the effect of confining pressure on the porous structure and connectivity of high-rank coal. ACS Omega. 7 (16), 14283–14290 (2022).

Wang, F., Cao, P., Cao, R. H., Xiong, X. G. & Hao, J. The influence of temperature and time on water-rock interactions based on the morphology of rock joint surfaces. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 78, 3385–3394 (2019).

Wang, Y., Liu, X., Liang, L. & Xiong, J. Experimental study on the damage of organic-rich shale during water-shale interaction. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 74, 103103 (2020).

Qin, Z. et al. Identification of microscopic damage law of rocks through digital image processing of computed tomography images. Trait Signal. 36 (4), 345–352 (2019).

Zhu, S., Song, S., Sun, Q., Yan, B. & Wang, C. Characteristics of water-rock interactions in the deep lower coal footing under different test conditions. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 33, 3231–3237 (2014).

Li, Z. W., Zhang, Y. J., Gong, Y. H. & Zhu, G. Q. Influences of mechanical damage and water saturation on the distributed thermal conductivity of granite. Geo Therm. 83, 101736 (2020).

Lu, Y., Wang, L., Sun, X. & Wang, J. Experimental study of the influence of water and temperature on the mechanical behavior of mudstone and sandstone. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 76 (2), 645–660 (2017).

Jia, H. et al. An NMR-based investigation of pore water freezing process in sandstone. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 168, 102893 (2019).

Yu, L. et al. Mechanical and micro-structural damage mechanisms of coal samples treated with dry–wet cycles. Eng. Geol. 304, 106637 (2022).

Pi, Z. et al. Experimental study on the influence of pore structure and group evolution on spontaneous combustion characteristics of coal samples of different sizes during immersion. ACS Omega. 8 (25), 22453–22465 (2023).

Han, P., Zhang, C., Wang, X. & Wang, L. Study of mechanical characteristics and damage mechanism of sandstone under long-term immersion. Eng. Geol. 315, 107020 (2023).

Tang, C. et al. Mechanical failure modes and fractal characteristics of coal samples under repeated drying–saturation conditions. Nat. Resour. Res. 30 (6), 1–18 (2021).

Song, M. et al. Effects of damage on resistivity response and volatility of water-bearing coal. Fuel 324, 124553–124567 (2022).

Yao, Q. et al. Effects of water intrusion on mechanical properties of and crack propagation in coal. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 49 (12), 4699–4709 (2016).

Han, P., Zhao, Y., Zhang, C. & Wang, X. Progressive damage characteristic and microscopic weakening mechanism of coal under long-term soaking. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 56 (11), 7861–7881 (2023).

Sun, X., Xu, H., Zheng, L., He, M. & Gong, W. An experimental investigation on acoustic emission characteristics of sandstone rockburst with different moisture contents. Sci. China Technol. Sc. 59 (10), 1549–1558 (2016).

Liu, X. et al. Research on mechanical properties and strength criterion of carbonaceous shale with pre-existing fissures under drying-wetting cycles. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 41 (2), 228–239 (2022).

Yao, Q. et al. Influence of moisture on crack propagation in coal and its failure modes. Eng. Geol. 258, 105156 (2019).

Liu, S. et al. Weakening mechanism and instability characteristics of coal pillar under mining disturbance and water immersion in water storage goaf. J. Min. Saf. Eng. 39 (6), 1084–1094 (2022).

Meng, F., Zhai, Y., Li, Y., Li, Y. & Zhang, Y. Experimental study on dynamic tensile properties and energy evolution of sandstone after freeze-thaw cycles. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 40 (12), 2445–2453 (2021).

Han, P., Zhao, Y., Zhang, C., Wang, X. & Wang, W. Effects of water on mechanical behavior and acoustic emission characteristics of coal in Brazilian tests. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mec. 122, 103636 (2022).

Yao, Q., Hao, Q., Chen, X. & Zhou, B. Design on the width of coal pillar dam in coal mine groundwater reservoir. J. China Coal Soc. 44 (3), 891–899 (2019).

Zhou, K., Dou, L., Song, S., Ma, X. & Chen, B. Experimental study on the mechanical behavior of coal samples during water saturation. ACS Omega. 6 (49), 33822–33836 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Damage evolution mechanism of coal rock under long-term soaking. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 46 (6), 1206–1214 (2024).

Gao, T. et al. Macro and micro fractures and strength reduction damage of faults with different water content. Sci. Technol. Eng. 24 (9), 3773–3780 (2024).

Lai, X., Zhang, S., Dai, J., Wang, Z. & Xu, H. Multi-scale damage evolution characteristics of coal and rock under hydraulic coupling. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 39, 3217–3228 (2020).

Wang, K., Jiang, Y. & Xu, C. Mechanical properties and statistical damage model of coal with different moisture contents under uniaxial compression. Chin. J. Rock. Mech. Eng. 37 (5), 1070–1079 (2018).

Li, B. et al. Mechanical properties and damage constitutive model of coal under the coupled hydro-mechanical effect. Rock. Soil. Mech. 42 (2), 315–323 (2021).

Cai, Y. et al. Acoustic emission characteristics of water-saturated coals under tri-axial stress condition in the process of deformation and failure. ESF 22 (3), 394–401 (2015).

Yu, X. et al. Uncovering the progressive failure process of primary coal-rock mass specimens: insights from energy evolution, acoustic emission crack patterns, and visual characterization. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 178, 105773 (2024).

Gong, S. et al. Dynamic Tensile Mechanical properties of Outburst Coal considering bedding effect and evolution characteristics of strain energy density. Explos Shock Waves. 43 (4), 043102–043101 (2023).

Zehnder, A. T. Griffith Theory of Fracture. In Encyclopedia of Tribology, edited by Q. Jane Wang and Yip-Wah Chung. Boston, MA: Springer, (2013).

Li, H. et al. Mode I fracture properties and Energy Partitioning of Sandstone under coupled static-dynamic loading: implications for Rockburst. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 127, 104025 (2023).

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 51804107), the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (grant number 2020JJ4260, 2021JJ30206), and the Key Projects of Hunan Education Department (grant number 21A0572), and the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Project for College students in Hunan Province (grant number S202411528042、S202411528194).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.Z.K. contributed to the study conception and experimental design. L.R. was involved in the experimental design, conducted the experimental tests, and drafted the manuscript. W.Y. and X.J.W. participated in the experimental testing and data analysis. L.J.Y. contributed to the coal sample mapping and experimental testing. Z.Y.F. and P.B. analyzed the experimental data and provided critical revisions to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zikun, P., Rui, L., Yan, W. et al. Experimental investigation into the Impact of Cyclic High Low Pressure Water Immersion on the Pore structure and Mechanical properties of coal. Sci Rep 15, 1288 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85746-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85746-0