Abstract

This paper presents a novel investigation of a magnetic sensor that employs Fano/Tamm resonance within the photonic band gap of a one-dimensional crystal structure. The design incorporates a thin layer of gold (Au) alongside a periodic arrangement of Tantalum pentoxide (\(\:{\text{T}\text{a}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{5}\)) and Cesium iodide (\(\:\text{C}\text{s}\text{I}\)) in the configuration \(\:[\:\text{A}\text{u}/{\:\left(\right({\text{T}\text{a}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{5})/(\text{C}\text{s}\text{I}\left)\right)}^{\text{N}}]\). We utilized the transfer matrix method in conjunction with the Drude model to analyze the formation of Fano/Tamm states and the permittivity of the metallic layer, respectively. These states can be manipulated based on the left-handed and right-handed circular polarization of electromagnetic waves, along with an applied magnetic field. Several key parameters were optimized, including material selection, layer thickness, unit cell periodicity, and the angle of incidence, to enhance the sensor performance. Additionally, we investigated how variations in magnetic field strength influence the position of Fano/Tamm resonance in the reflectivity spectrum of the interacting electromagnetic waves within a specific wavelength range of 60 μm to 140 μm. The proposed sensor displays good performance investigated by calculating several parameters like, sensitivity, figure of merit, quality factor and resolution. One of them, it shows a maximum sensitivity of 57 nm/Tesla within a magnetic field strength of 20 to 140 Tesla, positioning it as a promising candidate for various applications in magnetic field measurement and telecommunications, particularly in the unique far-infrared region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fano resonance has drawn the interest of numerous researchers because of its exceptional performance. The phenomenon was first identified in 1961 by the Italian physicist U. Fano1,2. This phenomenon is a notable type of optical resonance, resulting from the constructive and destructive interference between a discrete bound state and a continuous state. Unlike the symmetric Lorentzian resonance, the asymmetric Fano resonance manifests as an exceptionally sharp line that stretches from maximum to minimum, leading to high sensitivity within the structure3,4,5,6. The Fano formula is known as asymmetric resonance appears due to interaction between two scattering amplitudes, slow-varying background, and narrow-band. The asymmetric and ramp dispersion of Fano state is extremely promising in many applications specifically in a wide range of photonic devices, such as switches, reflectors, lasers, optical fibers, detectors, non-linear devices, and sensors7,8. Not only are the optical devices engaged with Fano modes, but they are also related to other broad range of applications, including optoelectronic, chemical, and biological applications9,10,11. Recently, Fano resonance has been used in a variety of advanced photonic applications such as optical sensors, low-power switches, and Fano-transistors based on its dignified peaks with respectable variations within a narrow range of wavelengths12,13. Moreover, in recent years, many researchers have sanctified their studies and researches for producing high- Q value Fano resonance modes in one-dimensional photonic crystal structures14,15.

Conversely, Tamm plasmon resonance (TPR) has attracted significant interest from researchers in recent decades as a unique type of electromagnetic surface state. The excitation or manifestation of TPR results from the confinement of the electromagnetic state at the interface between metal and photonic crystal structures16,17. Specifically, the TPR is a so-called surface plasmon resonance (SPR) that involves a collective oscillation of electrons at the outer surface of a metallic layer18,19. This occurs due to the coupling between photons and electrons propagating along the surface of the conductive material. Both experimental and theoretical studies have illustrated the characteristics of TPR that are achieved in a narrow peak of reflectance, transmittance, or absorption spectrum20,21. Moreover, the characteristics of Tamm plasmon resonance (TPR) can be modified by altering the thickness of the dielectric materials or the Bragg mirror, as well as the metallic plasmon. TPR is an effective tool for detecting minor changes at the outer surface and displays distinctive dispersion properties. Due to these features of the Tamm state, it can be applied in a variety of fields, including optical fibers, optical switching, sensors, absorbers, and various devices in microelectronics, biomedical science, microfluidics, and photonics22,23,24,25.

In this regard, photonic crystals (PhCs) are known as artificial nanostructures with periodic refractive indices that extend into one, two, and three dimensions (1D,2D, and 3D)26,27,28,29. PhCs attracted considerable attention due to their ability to control the propagation of the entire electromagnetic waves (EMWs) spectrum. In 1D PhCs, resonant peaks can appear in different shapes because of light localization28,30,31. Photonic crystals (PhCs) are composed of inhomogeneous arrays of periodic dielectric materials with alternating refractive indices and a defined lattice constant. A significant characteristic of these engineered structures is their capacity to confine and transmit specific ranges of incident light frequencies by propagating along the direction of periodicity, a phenomenon known as photonic band gaps (PhBGs)32,33. In fact, PhBGs are unique regions that trap limited bands of wavelengths of EMWs. Consequently, the frequencies of EMWs that are immure in these stopped bands can’t propagate in PhCs due to multi-Bragg scattering34,35. Additionally, defect modes arise in photonic band gaps (PhBGs) when a defect layer interrupts the periodic layers. The properties of PhBGs are significantly influenced by the permittivity and permeability of the materials used, along with factors such as the angle of incident radiation and the thickness of each material in the structure. As a result, photonic crystals have been applied in various technological sectors, especially in liquid, gas, temperature, biochemical sensors, and reflectors36. Recent studies have highlighted the applications of periodic PhCs in environmental biotechnology, biomedicine, optical communication, optical waveguide, optoelectronics, photodiodes, optical isolators, high-speed signal processing, and multi-channel filters37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46.

Nevertheless, the adjustability of PhCs through external electric or magnetic fields is considerably easier, more sensitive, and faster than that achieved through temperature variations and as well mechanical strain. For this reason, the external magnetic field stimulates a notable impact on the permittivity of dispersive materials, especially semiconductors and metals, which is attributed to the magneto-optic effect47. In general, the impact of the magneto-optic effect is assorted into categories such as Faraday, Voigt, Zeeman, cotton-Mouton, and Magneto-Optical Kerr Effect (MOKE)48,49. The Faraday Effect marked the inception of Magneto-Optical (MO) interaction. Specifically, in 1845, Michael Faraday witnessed the rotation of the polarization plane of linearly polarized light passing through lead-borosilicate glass under an applied magnetic field50. In contrast, between 1876 and 1878, John Kerr observed the rotation of the polarization plane of linearly polarized light upon reflection from the surface of iron, whether with in-plane or perpendicular-to-the plane of polarization51. Unlike Faraday effect, which exhibits a linear proportionality to the applied magnetic field in non-magnetized materials, Voigt effect shows a relationship that is proportional to the square of the magnetic field intensity. In Faraday effect, the external magnetic field aligns parallel to the propagation direction of the incident electromagnetic radiation52. In contrast, in Voigt effect, the external magnetic field aligns perpendicular to the propagation direction of the electromagnetic radiation52,53. Moreover, Faraday Effect along with its reflective counterpart, Magneto-Optical Kerr Effect (MOKE), are extensively employed for detecting the magnetization of many materials. The MOKE provides a distinctive method for determining the surface magnetization of thin films with heightened sensitivity54. Whilst the eigenmodes in Voigt effect are linearly polarized, they can be either left or right circularly polarized in Faraday effect. Additionally, any linearly polarized wave can be viewed as a superposition of two circularly polarized components: a left-circularly polarized (LCP) and a right-circularly polarized (RCP) one55.

Meanwhile, Aly et al., demonstrated the tunability of the defect mode inside the PhBG of the 1D defective PhCs based on the variations in the intensity of the applied magnetic field35. In their research study, the defect layer is designed from an n-doped Si semiconductor material. Their findings investigated that the defect mode can be shifted downwards the short wavelengths with the increase in the cyclotron frequency for RCP configuration. In contrast, the increase in the cyclotron frequency for LCP introduces a little shift in the position of the defect mode compared to RCP case towards the linger wavelengths. Therefore, their design could provide a relatively high sensitivity of 29 nm/Tesla for RCP case. However, a highly doping concentration value is required toward achieving such sensitivity.

In addition, Belyaev have experimentally introduced magneto plasmonic crystal comprising noble and ferromagnetic metals deposited on one-dimensional subwavelength grating to act as a magnetic field sensor54. The detection procedure is mainly based on the emergence of the MOKE at a narrow spectral region corresponding to the surface plasmon-polaritons excitation. However, the attained sensitivity is not exceedingly over 3 × 10–6 Oe.

Moreover, Aly et al., investigated the tunability of the PhBG inside a 2D PhC structure comprising cylindrical rods of Ag in a square lattice of a dielectric medium55. In this regard, their numerical results demonstrated the appearance of some dispersionless or flat bands, which in turns makes the designed structure of a potential interest through many optical applications such as filters, switches and modulators as well.

In this regard, we have introduced a simple design based on the 1D PhCs to act as a highly sensitive magnetic field sensor. The proposed design can be effective for a long range of the magnetic field values. Meanwhile, the considered structure comprises a thin layer of Au combined with a periodic arrangement of \(\:{\text{T}\text{a}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{5}\) and \(\:\text{C}\text{s}\text{I}\) through the optimum design, \(\:[\:\text{A}\text{u}/{\:\left(\right({\text{T}\text{a}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{5})/(\text{C}\text{s}\text{I}\left)\right)}^{\text{N}}]\). In addition, the applied magnetic field is introduced based on Faraday configuration. Interestingly, the designed structure demonstrates the coupling between Fano and Tamm plasmon resonance modes which represents the mainstay of our study. This coupled mode provides a highly sensitive response regarding the applied magnetic field copared to some of the previous studies. In particular, Au metallic layer receives some variations on its permittivity with the presence of the applied magnetic field as being discussed in the upcoming section. Therefore, the shift in the spectral position of the coupled Fano/Tamm mode is expected. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time in which the excitation of the coupled Fano/Tamm resonance could be introduced to act as a sensor for the magnetic field. Meanwhile, a detailed optimization process have been carried out to adopt the best performance of the designed sensor. In this context, our designed structure was initially introduced as [A(BC)N], where the symbol A represents the metallic material as the first layer, and (BC) denotes the periodic structure of the PhC with N representing the number of periods. Therefore, our numerical finding demonstrates firstly the emergence of the coupled Fano/Tamm resonant mode based on some organic and nonorganic materials in the design of our PhC structure.

In contrast to conventional materials, polymers were utilized as organic media, including Polychlorotrifluoroethylene (PCTFE), polymethylpentene (PMP), and high-density polyethylene (HDPE). In polymers, the refractive index mismatch is generally smaller compared to other layered structures, such as vacuum-deposited inorganic dielectrics56,57. However, this limitation can be overcome by incorporating a substantial number of layers. Additionally, the refractive index of polymeric layers can be fine-tuned through copolymerization or by blending miscible pairs of polymers58,59. The combination of polymers and dielectrics can enhance the structural integrity of photonic crystals and adjust the effective refractive index by increasing or decreasing the contrast between the two materials. Consequently, polymers play a vital role in photonic applications, with notable examples including plastic optical components such as Fresnel lenses, polarizers, diffusers, split ring resonators, and light pipes60,61.

In this regard, the maximum sensitivity of the designed structure could receive 57 nm/Tesla under RCP. The innovation of the proposed design lies in its straightforward detection process, providing high performance without the need for a defect layer, cavity, or magnetic fluid. Moreover, this sensor achieved high sensitivity and superb performance in needless doping semiconductors as in a previous study53. As a result, this sensor demonstrates a brilliant response for small and wide ranges of an applied magnetic field; it can be fruitful in a broad range of applications in optical communication systems and scanning applicants.

Our approach relies on the principles of the transfer matrix method and the Drude model. Numerical results show that the external magnetic field has a significant impact on the permittivity of the metal layer within the periodic photonic crystal at the resonant peak. As a result, the position and intensity of the coupled Tamm/Fano resonance mode are greatly influenced by the strength of the applied magnetic field. Given these characteristics, this design serves as an excellent candidate for magnetic applications and medical biosensors, as well as for optical communication systems, particularly in the infrared range of the spectrum.

This paper is organized as follows: In Sect. 2, we discuss the fundamental equations used in our analysis. Section 3 presents the numerical results and discussions on the reflectance characteristics of the 1D photonic crystals, achieved through a thorough optimization of all sensor parameters to determine the optimal design for the photonic crystal magnetic field sensor. Finally, Sect. 4 summarizes the conclusions drawn from this study.

Structure design and mathematical model

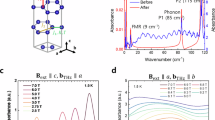

In this section, we have introduced the construction of the designed PhC magnetic field sensor. The proposed design demonstrates the emergence of the coupled Fano/Tamm resonance mode inside the PhBG. In this regard, this sensor is composed of a thin metallic layer covers the top surface of our periodic PhC. Here, each unit cell of our designed PhC is composed of Tantalum pentoxide (Ta2O5) and Cesium iodide (CsI), with thicknesses of \(\:{\text{d}}_{1}=5{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) and \(\:{\text{d}}_{2}=14\mu\:m\), respectively. Additionally, the surface layer is a superfine metallic slab with thickness \(\:{\text{d}}_{\text{m}}=6\text{n}\text{m}\) and refractive index \(\:{\text{n}}_{\text{m}}\).Then, the whole designed structure is immersed between air and substrate with refractive indices \(\:{\text{n}}_{0}\) and \(\:{\text{n}}_{\text{s}}\), respectively. Finally, the suggested design is exposed to the applied magnetic field (H) as shown in Fig. 1.

The schematic diagram depicts a multi-layer photonic crystal structure composed of \(\:{\text{T}\text{a}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{5}\:\text{a}\text{n}\text{d}\:\text{C}\text{s}\text{I}\), with a thin gold film covering the front face and a silicon substrate underneath. The entire photonic crystal design is subjected to an applied magnetic field.

In this study, our sensor is analyzed using a unique theoretical approach. Specifically, after depositing a thin layer of metal on the surface of the PhC design, which is situated in front of the Ta2O5/CsI multilayers, this metallic layer of Au exhibits distinct optical properties due to its interaction with EMWs and the applied magnetic field. In particular, the inclusion of the metallic layer is crucial for the emergence of the coupled Tamm/Fano resonance within the PhBG. Moreover, the permittivity of this layer is very sensitive to the applied magnetic field. Interestingly, the transfer matrix method (TMM), Drude model and Faraday configuration represents the mainstay of our theoretical methodology to adopt the response of the incident EMWs in the presence of the external applied magnetic field. Meanwhile, the electric and magnetic components of the interacting EMWs through a distinct layer i of the designed structure can be described as62:

Where, \(\:{A}_{i}\) and \(\:{B}_{i}\) define the amplitudes of both electric and magnetic fields inside layer i. Then, \(\:{k}_{i}\) is the wave vector in the ith layer. Therefore, this vector can be described in the vicinity of the wavelength of the incident EMWs (λ), the refractive index of layer i and the incident angle through this layer such that; \(\:\:{k}_{i}=(2\pi\:/\lambda\:)\:{n}_{i}cos{\theta\:}_{i}\). Then, Eq. (1) can be summarized in a matrix form such as62:

Whereas the resultant response of the EMWs between the boundaries (x0 and x1) of a certain layer \(\:i\) with thickness \(\:{d}_{i}={x}_{1}-{x}_{0}\), provides the following form:

Herein, the matrix \(\:{m}_{i}\) describes the response of the incident waves through each layer of the designed structure such as63,64,65:

Here, \(\:\:{\text{Q}}_{\text{i}}=\frac{2\pi\:{d}_{i}}{\lambda\:}{cos}{\theta\:}_{i}/{n}_{i}\)and \(\:{{\upvarsigma\:}}_{\text{i}}=\frac{{cos}{\theta\:}_{i}}{{n}_{i}}\), for TM polarization state. In contrast, we have \(\:{Q}_{i}\) = \(\:\frac{2\pi\:{d}_{i}}{\lambda\:}{n}_{i}{cos}{\theta\:}_{i}\) and\(\:{\:\varsigma\:}_{i}={n}_{i}{cos}{\theta\:}_{i}\) for TE case. In this context, Eq. (4) can be used to govern the response of the incident radiation through the metallic layer and each unit cell of the designed PhCs. Then, the overall response of the interacting EMWs through our candidate can be written in the following matrix45,66:

Where, \(\:{m}_{m},{m}_{1},{and\:m}_{2}\) are the matrices of the metallic layer, the 1st and 2nd layers of PhC’s unit cell, respectively. Then, the reflection coefficient can be described in the vicinity of Eq. (5) such as29,67:

Convincingly, the reflectivity of the sensor is computed as the following formula68,69,70:

Hence, \(\:{\varsigma\:}_{0}\) and \(\:{\varsigma\:}_{s}\) stand for air and substrate, respectively such that:

Then, for Au thin metallic layer, its permittivity can be described in the vicinity of Drude model such as71,72,73:

Here,\(\:{{\upomega\:}}_{\text{m}}\) and\(\:\:{\rm\:Y}\) are denoted as the plasma and damping frequencies, respectively. Then, these constants for Au have the values 13.71013 × 1015 and 40.49009 × 1012 in rad\ sec as indicated in Table 1. Where, \(\:{\upomega\:}\) is the angular frequency of the incident radiation (\(\:{\upomega\:}=\raisebox{1ex}{$2{\uppi\:}\text{c}$}\!\left/\:\!\raisebox{-1ex}{${\uplambda\:}$}\right.)\), and c is the speed of light. Thus, the refractive index of Au could be computed from:

Now, to include the effect of the external applied magnetic field on the permittivity of Au layer, we have considered Faraday configuration. In particular, Faraday geometry explains the relative permittivity of metal when the direction of the external magnetic field is parallel to the propagation direction of the incident EMWs such that53,74:

In this regard, the frequency modes may be right or left circularly polarized. Therefore, the right circular polarization (RCP) and left circular polarization (LCP) are marked by subscripts of + and –, respectively. Meanwhile, the values of \(\:{{\varepsilon\:}}_{\text{a}}\) and \(\:{{\varepsilon\:}}_{\text{b}}\) is implied as follow75:

Whereas, \(\:{\omega\:}_{c}\) refers to the cyclotron frequency that can be explicated in the term of magnetic field strength (B) as in the form76:

Such that, \(\:e\) represents the electronic charge, \(\:{m}_{e}\) depicts to the electron mass. Therefore, the permittivity of the metallic layer due to the effect of the external magnetic field for both right and left circularly polarized light categories respectively could be listed as:

Results and discussion

In this section, we have introduced the numerical findings of our proposed magnetic field sensor. Firstly, Fig. 2 illustrates the coupling between Fano and Tamm resonances by utilizing an arbitrary selection of the PhC constituent materials. In this regard, the figure investigates the emergence of a coupled Fano/Tamm resonance at a wavelength of 104 \(\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\). In fact, the shift in the position of this resonant mode represents the mainstay of our designed sensor. To accomplish this task efficiently, the type and properties of the used materials should be examined carefully towards the best performance. Therefore, we have introduced through the upcoming subsections an extensive optimization process for the overall considered materials in the vicinity of their indices of refraction and thicknesses as well.

To begin, a thin layer Au is embedded over the top surface of 5-unit cells of PhCs in which each one comprises two layers of strontium fluoride (SrF₂) and polymethylpentene (PMP). Therefore, this structure can be configured as [Au / (SrF₂/ PMP)5]. The initial thickness for each layer is set at \(\:{\text{d}}_{\text{m}}=4\:\text{n}\text{m}\) for Au layer, \(\:{\text{d}}_{1}=8\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) for SrF₂, and \(\:{\text{d}}_{2}=18\:{\upmu\:}\text{m}\) for PMP. Additionally, the angle of incidence is considered as, θ0 = 0°.

We aim to determine the optimal design for the photonic structure based on the materials used, the type of metal on the top surface, the thickness of each layer, the number of periods, and the angle of incidence, as well. In particular, the selection of these parameters will significantly impact the performance of the sensor.

Optimization of sensor parameters

In this subsection, we have started our optimization process towards the best performance of our sensing tool. Meanwhile, we have considered the case of the normal incidence for the interacting EMWs. The first imposed design for the optimization process incorporates two layers: SrF₂ and PMP, forming a unit cell of our PhC, along with a surface metallic layer of Au. All of parameters and values are kept as the same imposed values in the last subsection. The proposed structure is structured as [Metal / (SrF2/PMP)5.

This design shows the emergence of the coupled Tamm/Fano resonance mode as shown in Fig. 2. In this regard, we have optimized all of the materials used besides their thicknesses as follows.

Optimization of materials type

First, we examined the impact of a metallic layer on the sensitivity of the proposed structure, as shown in Fig. 3. Our design incorporates various fine layers of metals, including silver (Ag), aluminum (Al), gold (Au), and platinum (Pt). These metals possess distinct optical properties, including plasma frequency and damping constants, as detailed in Table 1. We can also derive their relative permittivity using the Drude approximation and Faraday geometry, as expressed in Eq. (15). Notably, the sensitivity of the design decreases when using metals like aluminum Al and Pt instead of Ag; it drops from 7.6 nm/Tesla to 5.8 nm/Tesla and 3.8 nm/Tesla, respectively. In contrast, the highest sensitivity value of 11.4 nm/Tesla is achieved when using Au on the surface of the structure, attributed to its favorable relative permittivity.

Then, Fig. 4 illustrates the optimal material chosen for the first layer of the photonic structure based on sensitivity values. Initially, we selected strontium fluoride (SrF₂) for our design due to its optical transparency, good thermal stability, high melting point, and low refractive index, achieving a sensitivity of approximately 11.4 nm per Tesla. However, when utilizing various materials that exhibit high thermal conductivity and stability at elevated temperatures such as gallium phosphide (GaP), silicon carbide (SiC), and those with excellent optical properties like zinc sulfide (ZnS) and gallium selenide (GaSe) none of them matched the sensitivity of the SrF₂ compound, the achieved sensitivity values for these materials are 9.8 nm/Tesla, 9.4 nm/Tesla, 9.2 nm/Tesla, and 11.2 nm/Tesla, respectively. Furthermore, sensitivity increases to 16 nm/Tesla when using hafnium dioxide (HfO₂), attributed to its high refractive index, low absorption, and excellent thermal stability. The highest sensitivity recorded is 21.8 nm per Tesla when employing transition metal oxides like tantalum pentoxide (Ta₂O₅), which possesses a high refractive index, large surface area, and high dielectric constant along with unique optical properties. In summary, the final configuration of the structure is labeled as \(\:[\:\text{A}\text{u}/{\:\left(\right({\text{T}\text{a}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{5})/(\text{P}\text{M}\text{P}\left)\right)}^{5}]\).

Next, we replaced PMP layer in each PhC’s unit cells with some different materials to enhance the contrast between its refractive indices and that of Ta2O5. We chose various polymer materials characterized by their low refractive index and stability, such as Polyethylene (HDPE), Polychlorotrifluoroethylene (PCTFE), and Polymethylpentene (PMP). As shown in Fig. 5, the sensitivity of these materials increased gradually, measuring 15.2 nm/Tesla, 16.4 nm/Tesla, and 21.8 nm/Tesla, respectively. However, cesium iodide (CsI), specified with its excellent clarity and transparency across a wide spectrum, exhibited greater contrast than polymers when used instead of PMP in the design of our PhC structure. In this regard, we can receive to a sensitivity of 24 nm/Tesla based on this material. Overall, the final configuration of the proposed design is represented as [Au / (Ta2O5/CSI)5].

Optimization of the thickness of each layer

In this subsection, we explore the optimal thickness of the metallic layer atop our proposed structure. As shown in Fig. 6, the sensitivity of the sensor is affected by variations in the thickness of Au layer, denoted as, \(\:{\text{d}}_{\text{m}}\). The diagram highlights the highest sensitivity in the presence of the applied magnetic field. When the magnetic field varies between 0 and 50 Tesla, we observed that the sensitivity increases gradually from 17 nm/Tesla to 24 nm/Tesla as the value of dm increases from 4 nm to 6 nm. However, further increase on the thickness of Au layer beyond 6 nm leads to a gradual decline in sensitivity, ultimately dropping below 10 nm/Tesla at dm = 12 nm. Among the considered thickness values of \(\:{\text{d}}_{\text{m}}\)=3, 6 nm, 12 nm, and 20 nm, the optimal thickness for achieving the desired optical properties and maximum sensitivity is 6 nm.

Next, Fig. 7 demonstrates the impact of Ta2O5 layers’ thickness (d1) on the sensitivity value of the sensor. Specifically, with thicknesses ranging from 3 μm to 20 μm (including 4 μm, 5 μm, 6 μm, and 10 μm), and an applied magnetic field varying from 0 Tesla to 50 Tesla, the sensitivity values fluctuate gradually between 7.2 nm/Tesla and 24 nm/Tesla. The highest sensitivity is achieved when the Ta2O5 layer thickness is of 5 μm. Conversely, increasing the thickness beyond 5 μm, leads to a decrease in the sensor sensitivity, dropping from the maximum to approximately 3 nm/Tesla. Therefore, the optimum thickness of Ta2O5 layers is considered to be 5 μm.

Now, we have introduced the role of CsI layers thickness on the sensitivity of the proposed design. Figure 8 indicates that the increase of d2 value from 5 μm to 14 μm leads to a significant increase in the sensitivity from 8.6 nm/Tesla to 24 nm/Tesla. For further increase in the value of d2 over 14 μm, the sensitivity suffers from a significant decline receiving a value of 8 nm/Tesla at 24 μm. This decrement in the sensitivity value at higher thickness values could be due to the decrements in the total impedance of the crystal, which, in turn, will impact the resonant peak displacement through the PnBG. Also, changing the thickness of the first or second layer, indeed, will change the position of the Fano/Tamm peak based in Bragg rule and Quarter wave stack rule80,81. Therefore, the optimal thickness of \(\:{\text{d}}_{2}\), which manifests a brilliant optical performance of the sensor is equivalent to 14 μm.

Optimization of the periodicity number

Herein, this subsection debates the significant effect of the structure’s periodicity on the sensitivity of the magnetic sensor. As illustrated in Fig. 9, the periodicity number of our PhC structure, which is labeled in the N symbol, alternates between 3 and 12. Meanwhile, the sensitivity of the proposed sensor is significantly affected by the change in the periodicity number. Here, the sensitivity received 14.2 nm/Tesla at N = 3, then increased to 24 nm/Tesla at N = 5. For more increase in the value of N to 8, 10 and 12, the sensitivity of the designed sensor investigates a significant decrease as shown in Fig. 9. Therefore, N = 5 represents the optimal periodicity of the designed structure. Here, the increment in the periodicity number increases the total impedance of the PhC and struggles the shift of the resonant peak. Therefore, we select the optimal value of N that achieves maximum sensitivity with the lowest number and that be easier from the fabrication view.

The optimization of the incident angle

It is worth mentioning that Fig. 9 displays the sensitivity of our proposed design at different incident angles. In all previous optimization steps, the incident angle is fixed at the normal incidence case. Now, with the conservation of the obtained optimal parameters such as \(\:{\text{d}}_{\text{m}}=6\text{n}\text{m}\) of Au metal, thickness \(\:{\text{d}}_{1}=5\mu\:\)m of Ta2O5 ,and \(\:{\text{d}}_{2}=24\mu\:m\) of CsI, we now check the influence of incident angle on the sensor sensitivity. The incident angle is proposed with different values such as \(\:{0}^{^\circ\:}\), \(\:{30}^{^\circ\:}\), \(\:{50}^{^\circ\:}\), and \(\:{70}^{^\circ\:}\). Consequently, the maximum sensitivity of 24.4 nm/Tesla is achieved via changing the incident angle from zero to the angle of \(\:{30}^{^\circ\:}\). While any increase in angle beyond \(\:{30}^{^\circ\:}\) leads to a decrease in sensitivity value until reaches 18.2 nm/Tesla at \(\:{50}^{^\circ\:}\) and 9.2 nm/Tesla at \(\:{70}^{^\circ\:}\) as shown in Fig. 10.

The performance analysis of the proposed design

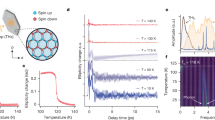

In this section, we present the overall performance of the 1D PhC sensor, based on the optimal values of the geometric and structural parameters of its constituent materials. To summarize, the optimal values for the various parameters are as follows: \(\:{\text{d}}_{\text{m}}=6nm\), \(\:{\text{d}}_{1}=5\mu\:m\), \(\:{\text{d}}_{2}=14\mu\:m\),and \(\:N=5\) with incident angle \(\:{30}^{^\circ\:}\). These parameters were determined after selecting Au metal along with Ta2O5 and CsI in the PhC structure. To interpret Fig. 11 depicts the optical characteristics of the coupled Tamm/Fano resonance with the variation of the external applied magnetic field from zero to 140 Tesla. The figure shows that both position and intensity of the resonant mode resulting in a straight line that extends from maximum to minimum, achieving high sensitivity is affected with the applied magnetic field.

This resonance is commonly known as asymmetric resonance due to the interference or coupling between two scattering amplitudes. Additionally, the coupling resonance of the Fano/Tamm position occurs in the absence of a magnetic field and solely due to the interaction between the EMWs and our designed PhC structure, specifically at \(\:{\lambda\:}_{res}=95.89\:\mu\:m\) as shown in Fig. 11.

On the other hand, applying a magnetic field of 20 Tesla yielded a maximum sensitivity of 57 nm/Tesla. However, increasing the magnetic field beyond 20 Tesla (to values such as 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, and 140 Tesla) resulted in an increase in the full width at half maximum (FWHM) from 6.27 μm to 8.51 μm. Concurrently, the sensitivity of our sensor decreased from its peak to 15.7143 nm/Tesla, as shown in Table 2. Additionally, there was a noticeable shift to shorter wavelengths in the spectrum when altering the coupling of the Fano-Tamm resonance line from \(\:{{\uplambda\:}}_{\text{r}\text{e}\text{s}}\)= 95.89 μm to \(\:{{\uplambda\:}}_{\text{r}\text{e}\text{s}}\) = 93.69 μm, which contributed to the broadening of the PhBG. Therefore, we assert that this resonance offers optimal performance in terms of high sensitivity, a favorable quality factor, and a low detection limit compared to alternatives. These factors can be quantified using the mathematical equations presented in the following formulas82,83:

Moreover, there are several important factors, including the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), which refers to the variation of the resonant position; Sensor Resolution (SR); Detection Accuracy (D.A) which is inversely proportional to the full width at half maximum; Dynamic Range (D.R); and Uncertainty ( \(\:{{\upsigma\:}}_{\text{P}\text{e}\text{a}\text{k}}\)). Consequently, all of these parameters can be performed using the following expressions84:

Furthermore, Table 2 shows that the performance of our candidate magnetic sensor design is influenced by various parameters. We observed that the sensitivity of the detector gradually decreases as the magnetic field strength increases from 20 Tesla to 140 Tesla, resulting in a decline in the Figure of Merit from 9.1 to approximately 1.8 /Tesla, as illustrated in Fig. 12(a). Additionally, there is an inverse relationship between the quality factor and sensor resolution as the applied magnetic field increases. While the quality factor decreases from 16.22 to 11, the sensor resolution improved from 313.5 nm/T² to 425.5 nm/T² under the applied magnetic field, enhancing the efficiency of our detector, as shown in Fig. 12(b). In Fig. 12(c), we also noted a gradual reduction in the dynamic range from 39.44 in the absence of a magnetic field to a maximum value of 32.11 at 140 Tesla. At the same magnetic field values, we observed an increase in the magnitude of uncertainty (\(\:{{\upsigma\:}}_{\text{P}\text{e}\text{a}\text{k}}\)).

Finally, after examining the performance of this magnetic sensor by analyzing the coupling of the Fano/Tamm resonance location, we can deduce the magnitude of an applied magnetic field required to produce resonance at a specific position. Initially, we applied a magnetic field to demonstrate the asymmetric resonance \(\:{{\uplambda\:}}_{\text{r}\text{e}\text{s}}\); however, we are now reversing this process by fitting the simulated results, as shown in Fig. 13. Consequently, a fourth-degree fitting proves to be the most suitable method for determining the magnetic field component responsible for the positional transition in the simulated results. Thus, Eq. (26), which calculates the B value, is dependent on \(\:{{\uplambda\:}}_{\text{r}\text{e}\text{s}}\), where A, B, C, and D constants equal A=\(\:-\)7.2 × 103, B=1 × 106, C=6.5 × 107, and D=1.5 × 109, respectively.

A brief comparison of our work with the others

In summary, we provided a concise comparison of our selected sensor with various earlier PhC sensor designs. This comparison highlights the outstanding performance and efficiency of our candidate sensor, demonstrated by its high resolution and a quality factor within the wavelength range of 60 μm to 140 μm. Moreover, our approach does not depend on a defect layer or analyte sample; instead, the sensor’s response is primarily driven by the interaction of metal permittivity in the 1D PhC structure with changes in the magnetic field, which subsequently influences the position of the resonant peak. The detection mechanism is based on novel phenomena associated with the coupling of Fano and Tamm resonance modes. The observed shifts in the resonance peak position are linked to the magneto-optic effect of the metal used. Additionally, the sensor achieves a maximum sensitivity of 57 nm/T (or 57 × 10⁻⁴ nm/Oe), which is significantly higher than that of other magnetic sensors, which typically operate with a sensitivity around 10⁻⁶ nm/Oe54. In addition, the proposed sensor provided high values for all other performance parameters. Moreover, previous studies, such as53,55, have examined the Faraday effect PhCs, but they have not addressed the localization of plasmonic resonances in metals or their use for magnetic field detection. Our sensor, on the other hand, is an excellent option for magnetic field applications and telecommunications systems, particularly in the infrared range. This range is crucial for electromagnetic wave applications that urgently require this type of magnetic field sensor. Finally, Table 3 presents a brief comparison with some of the previous literature based on the achieved sensitivity regarding the designed structures. Meanwhile, we believe that our designed magnetic field sensor could be of a significant interest compared to its counterparts due to its relatively high sensitivity and design simplicity as well.

Conclusion

To sum up, we have introduced a magnetic field sensor based on a 1D photonic structure in which a thin metallic layer is deposited on the top surface of a 1D PhCs. Interestingly, the inclusion of the metallic layer leads to the emergence of a coupled Fano/Tamm resonant mode. In this regard, the shift of this resonant mode represents the mainstay of the detection procedure. In this regard, our theoretical methodology towards the investigation of the numerical findings is mainly based on the well-known TMM, Drude model and Faraday effect as well. The numerical findings demonstrate that an optimal structure of,\(\:[\:\text{A}\text{u}/{\:\left(\right({\text{T}\text{a}}_{2}{\text{O}}_{5})/(\text{C}\text{s}\text{I}\left)\right)}^{5}]\) provides a relatively high sensitivity of 57 nm/Tesla. Notably, this value was achieved at some optimal geometrical and structural parameters such a layers’ thicknesses, incident angle and periodicity number as well. Finally, we believe that our designed sensor could provide valuable insights for magnetic field detection.

Data availability

Requests should be addressed to corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Change history

25 March 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95034-6

References

Fano, U. Effects of configuration interaction on intensities and phase shifts. Phys. Rev. 124 (6), 1866 (1961).

Limonov, M. F. Fano resonance for applications. Adv. Opt. Photonics 13 (3), 703–771 (2021).

Huo, K. et al. Tunable Fano resonance in a one-dimensional photonic crystal containing a Weyl Semimetal. Opt. Commun. 561, 130518 (2024).

Chen, J. et al. Plasmonic sensing and modulation based on Fano resonances. Adv. Opt. Mater. 6 (9), 1701152 (2018).

Miroshnichenko, A. E., Flach, S. & Kivshar, Y. S. Fano resonances in nanoscale structures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82 (3), 2257–2298 (2010).

Limonov, M. F. et al. Fano resonances in photonics. Nat. Photonics 11 (9), 543–554 (2017).

Chen, J. et al. Fano resonance in a MIM waveguide with double symmetric rectangular stubs and its sensing characteristics. Opt. Commun. 482, 126563 (2021).

Singh, R. et al. Ultrasensitive terahertz sensing with high-Q Fano resonances in metasurfaces. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105(17) (2014).

Ahmed, R. et al. Tunable fano-resonant metasurfaces on a disposable plastic‐template for multimodal and multiplex biosensing. Adv. Mater. 32 (19), 1907160 (2020).

Klimov, V. V. et al. Fano resonances in a photonic crystal covered with a perforated gold film and its application to bio-sensing. J. Phys. D 50 (28), 285101 (2017).

Yu, Y. et al. Fano resonance control in a photonic crystal structure and its application to ultrafast switching. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105(6) (2014).

Nozaki, K. et al. Ultralow-energy and high-contrast all-optical switch involving Fano resonance based on coupled photonic crystal nanocavities. Opt. Express 21 (10), 11877–11888 (2013).

Heuck, M. et al. Improved switching using Fano resonances in photonic crystal structures. Opt. Lett. 38 (14), 2466–2468 (2013).

Yu, Y. et al. All-optical switching improvement using photonic-crystal Fano structures. IEEE Photonics J. 8 (2), 1–8 (2016).

Chang, W. S. et al. A plasmonic Fano switch. Nano Lett. 12 (9), 4977–4982 (2012).

Kumar, S. Titanium Nitride as a plasmonic material for excitation of Tamm Plasmon states in visible and near-infrared region. Photonics Nanostruct. Fund. Appl. 46, 100956 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Lasing effect enhanced by optical Tamm state with in-plane lattice plasmon. J. Opt. 18 (2), 025103 (2016).

Normani, S. et al. The impact of Tamm plasmons on photonic crystals technology. Phys. B Condens. Matter 645, 414253 (2022).

Homola, J., Yee, S. S. & Gauglitz, G. Surface plasmon resonance sensors. Sens. Actuators B 54 (1–2), 3–15 (1999).

Zhang, X. L. et al. Hybrid Tamm plasmon-polariton/microcavity modes for white top-emitting organic light-emitting devices. Optica 2 (6), 579–584 (2015).

Xue, C. et al. Wide-angle spectrally selective perfect absorber by utilizing dispersionless Tamm Plasmon polaritons. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 39418 (2016).

Almawgani, A. H. et al. Photonic crystal nanostructure as a photodetector for NaCl solution monitoring: theoretical approach. RSC Adv. 13 (10), 6737–6746 (2023).

Lheureux, G. et al. Tamm plasmons in metal/nanoporous GaN distributed Bragg reflector cavities for active and passive optoelectronics. Opt. Express. 28 (12), 17934–17943 (2020).

Paternò, G. et al. Tuning fullerene intercalation in a poly (thiophene) derivative by controlling the polymer degree of self-organisation. Sci. Rep. 6 (1), 34609 (2016).

Gong, Y. et al. Perfect absorber supported by optical Tamm states in plasmonic waveguide. Opt. Express. 19 (19), 18393–18398 (2011).

Yablonovitch, E. Inhibited spontaneous emission in solid-state physics and electronics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58 (20), 2059 (1987).

John, S. Strong localization of photons in certain disordered dielectric superlattices. Phys. Rev. Lett. 58 (23), 2486 (1987).

Iwasaka, M. & Asada, H. Floating photonic crystals utilizing magnetically aligned biogenic guanine platelets. Sci. Rep. 8 (1), 16940 (2018).

Kumar, N. & Suthar, B. Advances in Photonic Crystals and Devices (CRC, 2019).

Basyooni, M. A., Ahmed, A. M. & Shaban, M. Plasmonic hybridization between two metallic nanorods. Optik 172, 1069–1078 (2018).

Joannopoulos, J. D. et al. Molding the flow of Light12 (Princet. Univ. Press, 2008).

Devashish, D. et al. Three-dimensional photonic band gap cavity with finite support: enhanced energy density and optical absorption. Phys. Rev. B 99 (7), 075112 (2019).

Zhu, W. et al. Zak phase and band inversion in dimerized one-dimensional locally resonant metamaterials. Phys. Rev. B 97 (19), 195307 (2018).

Wu, F. et al. Broadband wide-angle multilayer absorber based on a broadband omnidirectional optical Tamm state. Opt. Express 29 (15), 23976–23987 (2021).

Liu, Y. M. et al. Nonreciprocal omnidirectional band gap of one-dimensional magnetized ferrite photonic crystals with disorder. Phys. B Condens. Matter 645, 414210 (2022).

Kumar, A., Kumar, N. & Thapa, K. B. Tunable broadband reflector and narrowband filter of a dielectric and magnetized cold plasma photonic crystal. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 133, 1–8 (2018).

Rostami, A. et al. A novel proposal for DWDM demultiplexer design using modified-T photonic crystal structure. Photonics Nanostruct. Fund. Appl. 8 (1), 14–22 (2010).

Peng, J. et al. Thin films based one-dimensional photonic crystal for humidity detection. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 263, 209–215 (2017).

Karrock, T. & Gerken, M. Pressure sensor based on flexible photonic crystal membrane. Biomed. Opt. Express 6 (12), 4901–4911 (2015).

Lei, L. et al. Dual-channel asymmetric absorption-transmission properties based on plasma metastructures-photonic crystals. Opt. Express 32 (22), 38023–38038 (2024).

Yang, C. et al. Device design for multitask graphene electromagnetic detection based on second harmonic generation. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Tech. 72 (7), 4174–4182 (2024).

Lei, L. et al. Broadband asymmetric absorption-transmission and double-band rasorber of electromagnetic waves based on superconductor ceramics metastructures-photonic crystals. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 57, 1018101–1018111 (2024).

Chen, M. S., Wu, C. J. & Yang, T. J. Optical properties of a superconducting annular periodic multilayer structure. Solid State Commun. 149 (43–44), 1888–1893 (2009).

Yang, C. et al. Electromagnetic detection design in liquid crystals Janus metastructures based on second harmonic generation. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 73, 7007811 (2024).

Kumar, N., Kaliramna, S. & Singh, M. Design of cold plasma based ternary photonic crystal for microwave applications. Silicon, 1–12 (2021).

Kumar, N. & Ojha, S. P. Toward modal dispersion characteristics of a new unconventional optical waveguide with a core cross-section of plano-concave lens shape. Optik 124 (9), 773–777 (2013).

Pidgeon, C. Handbook on Semiconductors (ed. M. Balkanski) (North-Holland, 1980).

Abate, S. Infrared and Ranzan spectroscopy: methods and applications. Appl. Opt. 31 (831), 10565 (1995).

Pershan, P. Magneto-optical effects. J. Appl. Phys. 38 (3), 1482–1490 (1967).

Lan, T., Ding, B. & Liu, B. Magneto-optic effect of two‐dimensional materials and related applications. Nano Select. 1 (3), 298–310 (2020).

Voigt, W. Doppelbrechung Von Im Magnetfelde Befindlichem Natriumdampf in Der Rischtung normal zu den Kraftlinien. Nachr. Von Der Gesellschaft Der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse 1898, 355–359 (1898).

Roumi, B., Fallahi, V. & Abdi-Ghaleh, R. Faraday rotation effect in a one-dimensional photonic crystal containing the Weyl semimetal Co3Sn2S2 (2024).

Aly, H., ElSayed, H. A. & A. and Tunability of defective one-dimensional photonic crystals based on Faraday effect. J. Mod. Opt. 64 (8), 871–877 (2017).

Belyaev, V. K. et al. Magnetic field sensor based on magnetoplasmonic crystal. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 7133 (2020).

Aly, A. H., Elsayed, H. A. & El-Naggar, S. A. Tuning the flow of light in two-dimensional metallic photonic crystals based on Faraday effect. J. Mod. Opt. 64 (1), 74–80 (2017).

Edrington, A. C. et al. Polymer-based photonic crystals. Adv. Mater. 13 (6), 421–425 (2001).

Radford, J., Alfrey, T. Jr & Schrenk, W. Reflectivity of iridescent coextruded multilayered plastic films. Polym. Eng. Sci. 13 (3), 216–221 (1973).

Hamley, I. W. The Physics of Block Copolymers (Oxford University Press, 1998).

Wheatley, J. & Schrenk, W. Polymeric reflective materials (PRM). J. Plast. Film Sheeting. 10 (1), 78–89 (1994).

Boyle, B. M. et al. Structural color for additive manufacturing: 3D-printed photonic crystals from block copolymers. ACS Nano 11 (3), 3052–3058 (2017).

Kumar, N., Suthar, B. & Rostami, A. Novel optical behaviors of metamaterial and polymer-based ternary photonic crystal with lossless and lossy features. Opt. Commun. 529, 129073 (2023).

El-Naggar, S. A. Tunable terahertz omnidirectional photonic gap in one dimensional graphene-based photonic crystals. Opt. Quant. Electron. 47 (7), 1627–1636 (2015).

Sharma, S. et al. Omnidirectional reflector using linearly graded refractive index profile of 1D binary and ternary photonic crystal. Optik 126 (11–12), 1146–1149 (2015).

Wolf, E. The influence of Young’s interference experiment on the development of statistical optics. Progress Opt. 50, 251–273 (2007).

Born, M. & Wolf, E. Principles of optics, 704 (Cambridge University Press, 1999).

Wu, F. et al. Ultra-large omnidirectional photonic band gaps in one-dimensional ternary photonic crystals composed of plasma, dielectric and hyperbolic metamaterial. Opt. Mater. 111, 110680 (2021).

Li, N. et al. Highly sensitive sensors of fluid detection based on magneto-optical optical Tamm state. Sens. Actuators B 265, 644–651 (2018).

Abohassan, K. M., Ashour, H. S. & Abadla, M. M. One-dimensional ZnSe/ZnS/BK7 ternary planar photonic crystals as wide angle infrared reflectors. Results Phys. 22, 103882 (2021).

Bright, T. J. et al. Infrared optical properties of amorphous and nanocrystalline Ta2O5 thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 114(8) (2013).

Bright, T. J. et al. Optical properties of HfO2 thin films deposited by magnetron sputtering: From the visible to the far-infrared. Thin Solid Films 520(22), 6793–6802 (2012).

Marković, M. & Rakić, A. Determination of optical properties of aluminium including electron reradiation in the Lorentz-Drude model. Opt. Laser Technol. 22 (6), 394–398 (1990).

Devarapu, G. & Foteinopoulou, S. Broadband near-unidirectional absorption enabled by phonon-polariton resonances in SiC micropyramid arrays. Phys. Rev. Appl. 7 (3), 034001 (2017).

Almawgani, A. H. et al. Optical detection of fat concentration in milk using MXene-based surface plasmon resonance structure. Biosensors 12 (7), 535 (2022).

Pidgeon, C. & Balkanski, M. Handbook on Semiconductors (Free carrier optical properties of semiconductors, 1980).

Hatef, A. & Singh, M. R. Effect of a magnetic field on a two-dimensional metallic photonic crystal. Phys. Rev. A Atomic Mol. Opt. Phys. 86 (4), 043839 (2012).

Kuzmiak, V. & Maradudin, A. Photonic band structures of one-and two-dimensional periodic systems with metallic components in the presence of dissipation. Phys. Rev. B 55 (12), 7427 (1997).

Bikbaev, R. G., Vetrov, S. Y. & Timofeev, I. V. Optical Tamm states at the interface between a photonic crystal and a gyroid layer. JOSA B 34 (10), 2198–2202 (2017).

Rakić, A. D. et al. Optical properties of metallic films for vertical-cavity optoelectronic devices. Appl. Opt. 37 (22), 5271–5283 (1998).

Ordal, M. A. et al. Optical properties of fourteen metals in the infrared and far infrared: Al, Co, Cu, Au, Fe, Pb, Mo, Ni, Pd, Pt, Ag, Ti, V, and W. Appl. Opt. 24(24), 4493–4499 (1985).

Ahmed, A. M. & Mehaney, A. Ultra-high sensitive 1D porous silicon photonic crystal sensor based on the coupling of Tamm/Fano resonances in the mid-infrared region. Sci. Rep. 9 (1), 6973 (2019).

Kumar, S. & Das, R. Refractive index sensing using a light trapping cavity: a theoretical study J. Appl. Phys. 123(23) (2018).

White, I. M. & Fan, X. On the performance quantification of resonant refractive index sensors. Opt. Express. 16 (2), 1020–1028 (2008).

Shaban, M. et al. Tunability and sensing properties of plasmonic/1D photonic crystal. Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 41983 (2017).

Mehdi Keshavarz, M. & Alighanbari, A. Self-referenced terahertz refractive index sensor based on a cavity resonance and Tamm plasmonic modes. Appl. Opt. 59 (14), 4517–4526 (2020).

Aly, A. H., El-Naggar, S. A. & Elsayed, H. A. Tunability of two dimensional n-doped semiconductor photonic crystals based on the Faraday effect. Opt. Express 23 (11), 15038–15046 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R400), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding

The authors acknowledge Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R400), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Project administration, A. H., H. A. E., M. M., and A. M.; Supervision, H. E. A., A. H., M. R. A., H.A.E., H. E. A., and A. M.; Software, A. M.; Visualization, H. A. E., A. M. ; Writing - review & editing, H. A. E., M. M., A. H., and A. M.; Writing - original draft, H. A. E., M. M., and A. M.; Methodology, A. M., M. M., H. A. E., H. E. A., and A. H.; Data curation, A. M., M. M., and H. A. E.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained an error in the Acknowledgements section. It now reads: “The authors acknowledge Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University Researchers Supporting Project number (PNURSP2025R400), Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.”

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elsayed, H.A., Medhat, M., Hajjiah, A. et al. A promising high-sensitive 1D photonic crystal magnetic field sensor based on the coupling of Fano\Tamm resonance in far IR region. Sci Rep 15, 1977 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85747-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85747-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

High-performance Terfenol-D/PMMA phononic crystal sensor for tunable acoustic wave control and magnetic field detection

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

The role of Faraday effect on the one-dimensional n-doped Si photonic crystals towards magnetic field sensing applications

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Advanced plasmonic sensor design for sperm detection with machine learning-driven optimization

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2025)