Abstract

The liverwort Arnellia fennica has a circumarctic distribution with disjunct and scarce localities in the Alps, Carpathians, and Pyrenees. Within the Carpathians, it is only known from the Tatra Mountains (in Poland), where so far only four occurrences have been documented in the forest belt of the limestone part of the Western Tatras. The species is considered a tertiary relict, which owes its survival during the last glaciation period to low-lying locations in areas not covered by ice. Previously, it has been demonstrated that this plant does not produce gemmae in the Tatra Mountains, nor does it reproduce sexually, hence it has not spread in this massif despite the high availability of potential habitats. These studies address the following questions: (1) why A. fennica, an arctic-alpine species, has only been found at low elevations in the Tatra Mountains so far, (2) what were the possibilities of its survival during the glaciation period as verified based on the latest paleoglaciological map, (3) how this species persists in the Tatras and why it remains a rare plant. As a result, nine additional new occurrences were found, bringing the total to 13 throughout the massif. Some of the sites were found in the high mountain area. For the first time, the production of gemmae in the Tatra population of A. fennica was observed and documented, along with the presence of male specimens of this dioecious species. Genetic studies have shown that individuals from all three groups of sites are genetically homogeneous, indicating a lack of sexual reproduction. The only way of dispersal for A. fennica in the Tatras is through propagule production. The uniqueness and specificity of these structures have been described, which differ significantly from the common model known in liverworts. The rarity of the species in the Tatra massif is attributed to the inefficient mode of vegetative reproduction and the absence of sexual reproduction. Paleoglaciological analysis of all montane sites (historical and new) of A. fennica showed that half were located in areas covered by glaciers. The hypothesis of this liverwort’s survival during the glaciation period, at lower elevations, should be rejected. In light of the new data obtained, montane localities should be considered as secondary, which could have arisen after the glacier retreated only from high-mountain populations producing propagules transported downhill.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The liverwort Arnellia fennica (Gottsche & Rabenh.) Lindb. is currently classified within the monotypic family Arnelliaceae Nakai, which consists of only one species1. In earlier classifications, this family was more comprehensively defined. It included genera such as Southbya Spruce, Gongylanthus Nees, Stephaniella J.B. Jack, and Stephaniellidium S. Winkl. ex Grolle2,3. Subsequent taxonomic realignments were based on differences in the morphological and molecular structure of these genera. Based on morphological evidence, J. Váňa and others4 distinguished a new family, Southbaceae Váňa, Crand.-Stotl., Stotler et D.G. Long, comprising the genera Southbya and Gongylanthus. They also postulated that Arnelliaceae is a monotypic family. This depiction was later confirmed by the results of phylogenetic studies within the large group of leafy liverworts in the order Jungermanniales5. In the absence of molecular data confirming the placement of the genera Stephaniella and Stephaniellidium within Arnelliaceae or Southbyaceae, they are assigned to the family Stephaniellaceae R.M. Schust according to Schuster’s proposal6. Based on morphological data, this classification has been maintained, with the simultaneous emphasis that the mentioned genera cannot be classified within Arnelliaceae, Southbyaceae, and Gymnomitriaceae7. Arnelliaceae exhibits several morphological features that differentiate it from Southbyaceae, such as (1) a leaf border composed of thick-walled and swollen cells, (2) the presence of underleaves and a distinct perianth, and (3) the absence of elongated cells near the base of leaves4. The isolated character of Arnellia fennica is also emphasized by its chromosome number n = 6 (plant material from Alaska8), which is uncommon for liverworts. It is worth noting that specimens from Europe (the Tatra Mountains) have n = 99.

The global distribution of Arnellia fennica includes subarctic America, Western and Eastern Canada, North-Central USA, Europe, Siberia, and the Russian Far East2,10. In Europe, this plant is known from the northern part of the continent (Svalbard, Norway, Sweden, Finland) as well as from the mountain ranges of the continental part, namely the Alps (Austria, Switzerland, Italy, Slovenia, Germany, France), the Pyrenees (France), and the Carpathians (Poland)10,11,12. A. fennica is one of the rarest liverworts in Poland, with the Tatra Mountains being its only known location in the Carpathians and Central Europe. It is considered an endangered species in the country (category EN13), and also endangered in the entire Tatra Mts (EN14). To date, it has been reported from 5 localities (possibly two referring to the same site, thus actually 4), located in the montane zone from 1040 to 1360 m above sea level. All of them are within the Polish Western Tatras, in the massifs of Giewont and Zawrat Kasprowy9. In many phytogeographic concepts, A. fennica is regarded as an arctic-alpine species and a glacial relict2,15,16. J. Szweykowski and others9 hypothesize the tertiary age of A. fennica in the Tatras. This implies that the plant was present even before the Pleistocene glaciation, and its survival during the glacial period was only possible in cirques (or gullies), in the lower elevations of the Tatras not covered by glaciation. According to the cited authors, this hypothesis is supported by the montane distribution of A. fennica in the Tatras.

The genetic underpinnings of A. fennica’s persistence in the Tatra Mountains remain largely unexplored. Previous research has suggested the absence of sexual reproduction in this population9, a factor that could significantly impact its genetic diversity and evolutionary potential. To delve deeper into this aspect, the present study employs advanced genetic techniques, including the sequencing and assembly of organellar genomes and nuclear ribosomal DNA region. These analyses aim to shed light on the genetic structure and variability within the Tatra population of A. fennica, providing crucial insights into its reproductive strategies, dispersal patterns, and evolutionary history. By examining the genetic variation of this species, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of its resilience and vulnerability in the face of environmental challenges, ultimately informing conservation efforts for this rare and endangered liverwort13.

The aim of the conducted research was: (1) to determine the current distribution, population and genetic resources of the rare, arctic-alpine liverwort Arnellia fennica in its only known area of occurrence in the Carpathians (Polish Western Tatra Mountains), (2) to determine the dispersal strategy of A. fennica, thereby explaining the reasons for its rarity in this massif, and (3) to verify the hypothesis proposed by earlier researchers regarding the possibility of the survival of A. fennica in valleys at lower elevations of the Tatras, in the context of previously identified montane sites and the absence of sexual and asexual reproduction (through gemmae).

The implementation of the designed research should provide answers to the following questions:

-

1.

Why are the Arnellia fennica sites concentrated exclusively at low (montane) elevations in the Tatras, a species of arctic-alpine origin? Why did this liverwort not colonize areas above the upper tree line despite the ample availability and diversity of limestone habitats after the glacier retreat?

-

2.

How does this species persist in the Tatras, given that according to the literature9, it does not produce gemmae (known in this plant) or generative organs here? Do the Tatras populations reproduce sexually or are they clones? The answer to this question is crucial in interpreting the species distribution pattern, particularly in explaining its absence in the high mountain zone of the Tatras.

-

3.

Why is Arnellia fennica such a rare species in the Tatras despite the potentially high availability of habitats?

-

4.

Could the montane sites of Arnellia fennica overlaid on the paleoglaciological map confirm the hypothesis of the possibility of this plant’s survival during glaciation in lower elevations?

-

5.

Why are the current, low-lying Arnellia fennica sites concentrated around Giewont (Mała Dolinka, Strążyska Valley) and Zawrat Kasprowy (Żleb pod Czerwienicą), while absent in lower elevations, in similar limestone habitats in the Western or High Tatras?

Materials and methods

Object and area of study

Arnellia fennica is a leafy liverwort. The stems are light green, 1–2.5 mm wide and 1–3 cm long, simple or rarely with lateral branches emerging from the axils of ventral leaves (amphigastria). The leaves are opposite, erect, overlapping, fused at the base, rotundate to elliptical, bordered by 1–2 rows of thick-walled and radially elongated cells. Cells in the central part of the leaf measure 23–28 μm, are isodiametric, thin-walled, often with bulging thickenings. Amphigastria are subulate, 4–6 cells wide at the base. Gemmae are rarely formed, on the lower side of the leaves, 1–2 celled, thin-walled, colorless, 12–13 × 18–24 μm. A. fennica is dioecious17; Fig. 1).

Object and area of study: (A) location of the Tatra Mountains on the map of Europe; (B) Arnellia fennica on limestone rocks in Kalacki Żleb gully (photo by P. Górski, June 22, 2019), (C) division of the Tatra Mountains: 1 - state border, 2- a rough range of sedimentary calciferous rocks located in the northern part of the massif, G - Mt Giewont, KW - Mt Kominiarski Wierch, O - Mt Osobitá.

The Tatra Mountains are the highest mountain range in the Carpathians (Fig. 1). They form part of the Central Western Carpathians. The main ridge of the Tatra Mountains is 80 km long (56.5 km in straight line) and has a maximum width of 18.5 km (averaging 15 km). The Tatra Mountains are a border range separating Poland and Slovakia. The area covers 785 km², of which 610 km² (77.7%) lies in Slovakia and 175 km² (22.3%) lies in Poland18. The massif is divided into the Belianske Tatras, the Western Tatras, and the High Tatras (Fig. 1C).

The Belianske Tatras are located entirely in Slovakia. They cover an area of 67.5 km² and their main ridge is approximately 13 km long. They are entirely composed of sedimentary rocks, mainly limestone, marl, and dolomite. The highest peak is Havran, at 2152 m above sea level (m a.s.l.). The High Tatras cover an area of 335 km². They are the highest mountain range with the culmination being Gerlachovský štít peak (2655 m a.s.l.), which is also the highest peak in the Carpathians. On the Polish side, Mt. Rysy (2499 m a.s.l.) is the highest peak in Poland and forms part of the border ridge. The major part of the High Tatras – 253 km² – is located in Slovakia19. The length of the main ridge is 16.5 km18. The High Tatras are mostly composed of a crystalline core of granitoids, with minor sedimentary rocks. The Western Tatras (approximately 382.5 km²) occupy almost half of the entire area of the Tatra Mountains. The majority of them, 292 km², are located in Slovakia19. The length of the main ridge is approximately 42 km. The highest peak is Bystrá (2248 m a.s.l.) located in Slovakia. On the Polish side, Starorobociański Wierch (2176 m a.s.l.) is the highest peak. Metamorphic rocks (mainly gneissic rocks and crystalline slates) and sedimentary rocks predominate in the geological structure. The contribution of magmatic rocks (granite) is low.

These studies were conducted in an area where sedimentary calcareous rocks occur. They mainly cover the northern part of the Tatras (Fig. 1C). The major limestone formations in the area of Poland in the Western Tatras are formed by Mt. Giewont (1894 m a.s.l.), Mt. Kominiarski Wierch (1829 m), Zawrat Kasprowy (1625 m a.s.l.) and the northern parts of the mountain valleys (e.g., the Dolina Strążyska, Dolina Kościeliska, and Dolina Chochołowska Valleys). The nomenclature for vascular plants, mosses, and liverworts has been adopted according to polish species lists20,21,22.

Field research

The research took place from 2020 to 2023 across the entire area of limestone occurrence in the Polish part of the Western and High Tatras. A particular focus was placed on hard-to-reach habitats at higher elevations in the mountains. During fieldwork, each occurrence of Arnellia fennica was recorded and designated as a “record.” Two “records” more than 100 m apart were considered separate “localities.” This method identified places with locally larger populations of A. fennica without multiplying the number of sites. All historical herbarium materials of A. fennica in Poland were examined. These materials are stored in the herbaria of the W. Szafer Institute of Botany of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Kraków (National Collection of Biodiversity, KRAM B) and the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań (POZW). The latest study depicting the extent of glaciers in the Tatras in the form of a KML layer in Google Earth was used for paleoglaciological considerations23.

Molecular analyses

Total genomic DNA from five stems from each tuft was extracted using the Qiagen Mini Spin Plant Kit (Qiagen, Germany). Details regarding DNA quantification and nanopore sequencing are identical to those in previous studies24,25. The purity and quantity of DNA samples were assessed spectrophotometrically using a Cary 60 spectrophotometer (Agilent) and the Qubit fluorometer and Qubit™ dsDNA BR Assay Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, NM, USA). The fragmentation and DIN parameter were checked by capillary electrophoresis using Tapestation (Agilent) with a Genomic kit. The prepared library was sequenced using FLO-MIN114 (ONT) flow cell and sequenced using a Minion Mk1C device equipped with the latest Minknow software. Raw reads were basecalled using Dorado 0.5.1 (ONT) using the SUP model with enabled duplex reads calling. For downstream analyses, reads containing duplex flags were extracted using Samtools software26. Applying high-quality duplex reads (Q > 30) allows for the assembly of error-free organellar genomes using exclusively nanopore sequencing technology27. Obtained raw reads were trimmed using porechop 0.2.4 and assembled using Flye 2.91 assembler28, which produced complete, circularized plastome and mitogenome contigs. The nuclear NOR sequences were identified by mapping the assembled sequences on a Calypogeia sinensis Bakalin et Buczkowska 16s rRNA-ITS1-5.8s rRNA-ITS2-26s rRNA region29. To identify SNPs, BAM files generated during the assembly process were analyzed using CLAIR3 v.1.0.030 and the r1041_e82_400bps_sup_v400 model, with parameters set to -t = 120, -p - min_coverage = 20, and -enable_long_indel. Variants in homopolymeric regions, which are particularly susceptible to deletion errors in long-read sequencing technologies, were excluded from the subsequent analysis.

Phylogeny

The phylogenetic analysis included complete chloroplast and mitochondrial genome sequences from 29 specimens of leafy liverworts, with Ptilidium ciliare (L.) Hampe (Ptilidiales) as the outgroup. These genomes were aligned using MAFFT, and Gblocks 0.91b was employed to remove ambiguously aligned regions. PartitionFinder2 was used to identify the most suitable partitioning strategies and corresponding models for nucleotide substitution, with dataset blocks designated in advance based on various genetic elements and codon positions. The Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and a ‘greedy’ algorithm, considering branch lengths as independent, guided the selection of the optimal partitioning scheme. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using maximum likelihood (ML) as implemented in IQ-Tree2 with 2000 non-parametric bootstrap replicates. The resulting trees of mitochondrial and plastomes datasets were compared using the phytools 1.0–3 R package’s31 cophylo function.

Results

Distribution of Arnellia fennica in the Tatra Mountains

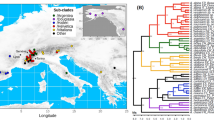

Arnellia fennica is found exclusively in the Western Tatra Mountains (Fig. 2). Due to conducted research, nine new localities of this plant have been identified (for a total of 15 records). Considering historical data, A. fennica has a total of 13 localities. So far, this species has been observed in the Giewont massif (Mała Dolinka and Strążyska Valleys) and on Mt. Zawrat Kasprowy (Żleb pod Czerwienicą gully). The latest studies indicate that the largest Tatra populations of this plant are located on the northern slopes of Mt. Kominiarski Wierch (6 localities and 12 records). The locations of A. fennica are distributed in altitudes ranging from 1040 m (minimum altitude; Strążyska Valley, leg. I. Szyszyłowicz, det. J. Váňa;15,32) to 1605 m (maximum; Mt. Długi Giewont, leg. P. Górski, 2022). Taking into account historical and current data, the majority of records are found in the altitude range of 1301–1600 m above sea level (Fig. 3).

It is worth noting that all confirmed locations of Arnellia fennica are associated with high-mountain limestone massifs, i.e., those where subalpine and alpine vegetation belts are developed. These include Kominiarski Wierch, Giewont, and Zawrat Kasprowy. This applies to both montane and high-mountain locations. No montane locations of this liverwort have been found in areas with low (in forest belts) limestone rocks (e.g., Siwiańskie Turnie, Wielkie/Małe Koryciska, several valleys of the Western Tatra region up to the limestone rocks of the High Tatra region around Kopy Sołtysie). The number of potentially favorable and montane habitats for the discussed species in the Polish Tatra Mountains is extensive. Despite this, the Arctic-alpine A. fennica is exclusively associated with the coldest regions of the northern faces of high-mountain massifs.

List of localities

New localities

The Massif of Mt. Kominiarski Wierch ̶ locality 1: Dudowe Spady (in the western part), northern slopes of Mt. Kominiarski Wierch, at the mouth of the gully descending from the summit, limestone rocks, MGRS 34UDV1555, 49.246682°N, 19.832614°E, alt. 1321 m a.s.l., leg. P. Górski 3/2020, 13.07.2020, 12.08.2023, present male specimens (POZNB 4557, record 1); Dudowe Spady (in the western part), northern slopes of Mt. Kominiarski Wierch, at the mouth of the gully descending from the summit, limestone rocks, approximately 45 m higher in the gully from record 1, MGRS 34UDV1555, 49.246322°N, 19.832391°E, alt. 1340 m a.s.l., leg. P. Górski 5/2020, 13.07.2020, 12.08.2023, c. gemm. (POZNB 4558, record 2); locality 2: Dudowe Spady (in the western part), northern slopes of Mt. Kominiarski Wierch, in the upper part of the gully descending from the summit, MGRS 34UDV1455, 49.243907°N, 19.831219°E, alt. 1554 m a.s.l., leg. P. Górski 1188/2023, 12.08.2023, c. gemm., present male specimens (POZNB 4564); locality 3: Dudowe Spady (in the eastern part), northern slopes of Mt. Kominiarski Wierch, at the mouth of the gully descending from the summit, closer to Kufa, MGRS 34UDV1555, 49.246035°N, 19.8353640°, alt. 1418 m a.s.l., P. Górski 412/2021, 12.08.2021 (record 1); Dudowe Spady (in the eastern part), northern slopes of Mt. Kominiarski Wierch, at the mouth of the gully descending from the summit, closer to Kufa, approximately 25 m south of record 1, MGRS 34UDV1555, 49.245850°N, 19.835515°E, alt. 1411 m a.s.l., leg. P. Górski 294/2020, 5.11.2020 (POZNB 3549, record 2); locality 4: Dudowe Spady (in the eastern part), northern slopes of Mt. Kominiarski Wierch, at the mouth of the gully descending from the summit, closer to Kufa, approximately 113 m south of locality 2 (record 1), MGRS 34UDV1555, 49.245052°N, 19.835754°E, alt. 1510 m a.s.l., leg. P. Górski 302/2020, 5.11.2020 (POZNB 3568); locality 5: Dudowe Spady (in the eastern part), northern slopes of Mt. Kominiarski Wierch, at the mouth of the gully descending from the summit, closer to Kufa, approximately 240 m from locality 3 (record 1) and about 155 m from locality 4, MGRS 34UDV1555, 49.244614°N, 19.837775°E, alt. 1541 m a.s.l., leg. P. Górski 494/2021, 15.09.2021 (POZNB 3948); locality 6 (the extreme locations of record 1–5 are approximately 92 m apart from each other): northeastern slopes of Mt. Kominiarski Wierch, in the upper part of Żleb Żeleźniak, limestone rocks, MGRS 34UDV1655, 49.243651°N, 19.848250°E, alt. 1402 m a.s.l., leg. P. Górski 343/2020, 1002/2023, 9.11.2020, 19.06.20023, c. gemm., present male specimens (POZNB 3621, 4561, record 1), MGRS 34UDV1655, 49.243319°N, 19.848221°N, alt. 1449 m a.s.l., P. Górski 1004/2023, 19.06.2023 (record 2), MGRS 34UDV1655, 49.243155°N, 19.848386°E, alt. 1443 m a.s.l., P. Górski 1011/2023 (record 3), MGRS 34UDV1655, 49.242948°N, 19.848261°E, alt. 1461 m a.s.l., leg. P. Górski 1009/2023, 19.06.2023, c. gemm. (POZNB 4562, record 4), MGRS 34UDV1655, 49.242920°N, 19.847681°E, alt. 1465 m a.s.l., leg. P. Górski 1012/2023, 19.06.2023 (POZNB 4563, record 5).

The Massif of Mt. Giewont ̶ locality 7: Mt. Długi Giewont, upper part of the Sucha Giewoncka Valley, on a rocky slope just above the debis slope, MGRS 34UDV2356, 49.255333°N, 19.946689°E, alt. 1523 m a.s.l., leg. P. Górski 929/2022, 25.10.2022 (POZNB 4457); locality 8: Mt. Długi Giewont, from the side of the Sucha Giewoncka Valley, high on the vertical northern walls, rocky ledges with alpine grasslands, MGRS 34UDV2356, 49.254504°N, 19.947231°E, alt. 1605 m a.s.l., leg. P. Górski 935/2022, 25.10.2022 (POZNB 4479).

The Massif of Zawrat Kasprowy ̶ locality 9: northern slopes in the eastern part of the Mt Zawrat Kasprowy, closer to Jaworzyńska Pass, partially shaded by rowans and spruces, limestone rocks in a wide gully, MGRS 34UDV2655, 49.250819°N, 19.995505°E, alt. 1382 m a.s.l., leg. P. Górski 1085/2023, 15.07.2023, c. gemm. (POZNB 4560).

Historical localities

Locality 10: Dolina Strążyska Valley, near Sycząca, alt. 1040 m a.s.l., leg. I. Szyszyłowicz, 18??, erroneously named and published as Jungermannia crenulata Sm.32. ; prof. J. Váňa carried out a revision based on specimens deposited in the herbarium in Prague, Czech Republic (PRC15); the same herbarium material is also present in Kraków, Poland (KRAM B-198331); between 2020 and 2023, the presence of Arnellia fennica at this locality was not confirmed; locality 11: between the forest on Jaworzynka and the ‘Magóra Cave’, alt. 1154 m a.s.l., leg. I. Szyszyłowicz as Jungermannia crenulata, 16.09.188232, KRAM B-198332); this locality was confirmed later by J. Szweykowski and others9: Żleb pod Czerwienicą gully, rock outcrops in the central part of the gully, alt. 1275 m a.s.l., leg. J. Szweykowski and others, 15.08.1983 (POZW 24704); between 2020 and 2023, the presence of Arnellia fennica at this locality was not confirmed; locality 12: Mała Dolinka Valley, northeastern slopes of Mt Giewont at the boundary between the forest and rock walls, alt. 1200 m a.s.l., leg. J. Szweykowski, M. Koźlicka, 29.08.1983 (POZW 247059), ; this locality was confirmed in 2022 (MGRS 34UDV2256, 49.254341°N, 19.932501°E, alt. 1308 m a.s.l., leg. P. Górski 783/2022, 18.10.2022, POZNB 4559); locality 13: Kalackie Koryto gully, limestone rocks, alt. 1350–1360 m a.s.l., leg. J. Szweykowski, H. Klama, 22-23.08.1985 (POZW 23608, 236379), ; this locality was confirmed in 201133, and 2023 (MGRS 34UDV2456, 49.255855°N, 19.959827°E, alt. 1340 m a.s.l., P. Górski 1094/2023, 16.07.2023).

Habitats of Arnellia fennica in the Tatra Mountains

Arnellia fennica occurs on limestone rocks in the Tatra Mountains, specifically on ledges with vegetation of the Carici sempervirentis-Festucetum tatrae Szaf., Pawł. et Kulcz. (1923) 1927 association (Seslerion tatrae Pawł. 1935 alliance) or directly on bare, vertical rock surfaces. Within the investigated sites, the following vascular plants were recorded within patches of A. fennica: Carex firma Host, C. sempervirens Vill., Bellidiastrum michelii Cass., Swertia perennis L., Salix silesiaca Willd., Ranunculus alpestris L., Heliosperma quadridentatum (Murray) Schinz & Thell., Saxifraga paniculata Mill., Viola biflora L., Potentilla crantzii (Crantz) Beck ex Fritsch, Trisetum alpestre (Host) P. Beauv., Phyteuma orbiculare L., Campanula polymorpha Witasek, Valeriana tripteris L., Primula elatior (L.) Hill, Luzula sylvatica (Huds.) Gaudin, and Selaginella selaginoides (L.) P. Beauv. The moss layer consists of mosses such as Ditrichum flexicaule (Schwägr.) Hampe, Orthothecium rufescens (Dicks. ex Brid.) Schimp., Bartramia halleriana Hedw., Timmia norvegica J.E. Zetterst., Fissidens dubius P.Beauv. var. dubius, Plagiopus oederiana (Sw.) Limpr., Mnium thomsonii Schimp., Thuidium assimile (Mitt.) A.Jaeger, Barbula crocea (Brid.) F.Weber & D.Mohr, Bryum elegans Nees, and liverworts - Mesoptychia heterocolpos (Thed. ex Hartm.) L. Söderstr. & Váňa, M. collaris (Nees) L. Söderstr. & Váňa, Metzgeria pubescens (Schrank) Raddi, Trilophozia quinquedentata (Huds.) Bakalin, Scapania gymnostomophila Kaal., S. aequiloba (Schwägr.) Dumort., S. calcicola (Arnell & J. Perss.) Ingham, Cololejeunea calcarea (Lib.) Schiffn., Plagiochila porelloides (Torr. ex Nees) Lindenb., Aneura pinguis (L.) Dumort., Preissia quadrata (Scop.) Nees, Conocephalum salebrosum Szweyk., Buczk. & Odrzyk., and Pedinophyllum interruptum (Nees) Kaal.

Arnellia fennica is most commonly found in gullies beneath high and long ridges stretching in an east-west direction, with extensive walls generally exposed to the north (Fig. 4). Limestone rocks with A. fennica are consistently exposed and unshaded (or partially shaded), oriented along the long axis of the gully. It can be presumed that the microclimatic conditions in montane locations are influenced primarily by cold air descending from the northern faces of the massifs.

Habitats of Arnellia fennica in the Western Tatras: (A,B) outcrops of limestone rocks in the upper part of Żleb Żeleźniak gully beneath the walls of Mt. Kominiarski Wierch (June 19, 2023); (C,D) a wide (unnamed) gully beneath the massif of Zawrat Kasprowy (July 15, 2023); the patch with A. fennica is marked with a red arrow (photo by P. Górski).

Reproduction of Arnellia fennica in the Tatra Mountains

The conducted analysis revealed shoots producing vegetative propagules. Out of 7 examined samples from various locations, individuals with gemmae were found in 5 tufts. One sample had few stems with gemmae, ranging from 1 to 2. It is worth noting that Arnellia fennica produces propagules in a manner atypical for liverworts. Most representatives of this group produce gemmae at the apex of upper leaves. These structures can easily detach from the parent plant and be dispersed by wind or water. They are usually immediately visible in the field. In Arnellia fennica, vegetative propagules are formed on the abaxial leaf surfaces, typically at the base or middle part of the leaf. This means that they are (partially or entirely) covered by a pair of leaves located below. To find them within the gametophyte, each pair of upper gametophyte leaves must be spread apart, and the leaves above observed.

In the examined samples of Arnellia fennica, shoots (and leaves) in various stages of propagule formation were observed. Initially, the plant produces thread-like, multicellular outgrowths (filaments) on the lower side of the leaf, at the apex of which gemmae begin to detach (Fig. 5A,B). In the advanced stage, a larger portion of the lower leaf surface is densely covered with propagules (Fig. 6A-a1); filaments are no longer visible, and the propagules detach easily from the parent plant (Fig. 6A-a2). The gemmae are 1- or 2-celled and colorless (Fig. 6B).

Vegetative propagation of Arnellia fennica observed on shoots collected in the Tatra Mountains: (A) prepared whole leaf with gemmae developing on the abaxial side: a1 - basal part of the leaf with very intense production of propagules, a2 - gemmae detached from the leaf during specimen preparation, (B) gemmae (photo by P. Górski).

The analysis of the collected plant material also resulted in the discovery of male plants of Arnellia fennica. Out of 7 examined samples, male specimens were present in 3 tufts. Plants with visible female organs (perianths) were not found.

Localities of Arnellia fennica on the paleoglaciological map of the Tatra Mountains

J. Szweykowski and others9 hypothesized that the montane localities of Arnellia fennica were refugia where this species survived during the last glacial period. Considering new localities, only half of the current montane localities were in ice-free areas (Fig. 7). The locality with the highest probability of survival was the lowest one in the Strążyska Valley, at an altitude of 1040 m a.s.l. The valley was not covered by glaciation, except for the upper part adjacent to the walls of Mt. Giewont23. The remaining localities, namely Kalackie Koryto and Żleb Żeleźniak, are much higher (1335–1360 m and 1402–1465 m above sea level, respectively). Although there are no terrain features indicating glaciation in these areas, it is suspected that thermal conditions would be extremely challenging for vegetation or could even preclude it. Notably, these gullies were directly adjacent to the northern walls of the Giewont and Kominiarski Wierch massifs. Therefore, it is doubtful that the montane localities of A. fennica served as refugia for this plant, ensuring its survival during the glacial period and acting as a gene pool for the establishment of populations of this species after the glaciation.

Localities of Arnellia fennica on the paleoglaciological map of the Tatra Mountains (based on KML layer in GoogleEarth23). Explanations: localities covered by glaciation − 1,3,4,7,9,11,12; sites outside the glacier-occupied area − 2,5,6,8,10,13; origin of sites (see List of localities): 1–9: Górski, Szczecińska, Sawicki (orig.), 10: I. Szyszyłowicz and J. Váňa15,32, 11–13: J. Szweykowski and others9.

Organellar genomes, infraspecific variation and phylogenetic relationships

The plastid genome of Arnellia fennica is a circular molecule of 119,773 bp in length (Fig. 8) that contains typical regions found in land plants: a large single copy (LSC) region; a small single copy (SSC) region; and two, 9,038 bp long, inverted repeat regions (IRs). A total of 122 unique genes were identified within the plastome of Arnellia, with only one copy from the inverted repeat regions. This includes 81 protein-coding genes, four ribosomal RNA genes, 31 transfer RNA genes, and six ycf genes with unspecified functions. The chloroplast genome of A. fennica contains 20 introns. Of these, ten protein-coding genes (rps12, ndhA, ndhB, rpl2, rpl16, rpoC1, ycf66, atpF, petB, petD) and six transfer RNAs (trnI-GAU, trnA-UGC, trnV-UAC, trnL-UAA, trnK-UUU, trnG-UCC) contain a single intron, while two genes (clpP and ycf3) contain two introns each. The base composition of the chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) is as follows: adenine (A) 33.0%, cytosine (C) 16.9%, guanine (G) 17.2%, and thymine (T) 32.9%, resulting in an overall GC content of 34.1%. Despite relatively high read coverage ranging from 150 to 350, no variation was detected within the sample (each sample comprises five stems from a patch) or at the intraspecific level. Comparative plastome analysis of all eight samples (each containing five stems from a single patch) did not reveal any variation within or between samples.

The mitochondrial genome of Arnellia fennica is 158,574 bp in length (Fig. 9), with a GC content of 44.7%. The overall GC content of the mtDNA is 44.7%, which is typical for most liverwort gene orders. The mitogenome of A. fennica contains 70 unique genes, including 42 protein-coding genes, 3 ribosomal RNAs, and 25 transfer RNAs, which is a typical set of mitochondrial protein-coding genes involved in respiration and protein synthesis. Similar to the plastome analysis, comparative analyses of the obtained mitogenomes did not reveal any differences among or within the samples.

The nrDNA repeat unit of Arnellia fennica follows a common organizational scheme (Fig. 10). A single unit comprises genes coding for 18 S (1,813 bp long), 5.8 S (159 bp), and 25 S nrRNA (1,984 bp), as well as two non-coding regions: internal transcribed spacer 1 (347 bp) and internal transcribed spacer 2 (1726 bp). Initial screening revealed two NOR haplotypes, which differ by one substitution (T-> C) at the 401 bp position of the 26 S rRNA gene. However, this variation was also found within the samples and differed only in frequency, which ranged from 0.32 to 0.45.

The phylogenomic trees based on mitochondrial and plastid datasets (Fig. 11) revealed similar topologies. Both datasets resolved Porellales as sister to Jungermanniales, but the common clade in relation to Ptilidiales (outgroup) was poorly supported (69% bootstrap support) in the case of the mitochondrial dataset. Within Jungermanniales, three main clades were formed: Cephaloziineae resolved as a sister to Jungermanniineae and Lophocoleineae, which formed a common, well-supported clade. Arnellia fennica was grouped together with Gymnomitrion concinnatum (Lightf.) Corda (with maximum bootstrap support in both datasets) and formed a sister clade to the Calypogeiaceae.

Incongruence between mitochondrial and plastid datasets was found within Cephaloziineae: the datasets were incongruent in resolving the position of Tricholocela tomentella (Ehrh.) Dumort., which in the plastome tree formed a common clade with Herbertus, while in the mtDNA-based tree, it was clustered with Heteroscyphus and Plagiochila.

Discussion

The discovery of high-altitude stands of Arnellia fennica in the Tatra Mountains, along with the observation of the plant’s production of vegetative propagules, has significantly altered the interpretation of its distribution and occurrence in the massif, historically and contemporarily. Research by J. Szweykowski and others9 suggests that Arnellia fennica shoots in the Tatra Mountains do not form gemmae or gametangia. According to the mentioned authors, this characteristic prevents the colonization of higher elevations after glacial retreat and explains why the sites of this arctic-alpine plant in the Tatra Mountains are restricted to montane areas. I. Szyszyłowicz also indicates that the collected gametophytes are sterile32, see page 74). Thus, the question arises: how does the population of A. fennica reproduce and persist in the massif? The only possible explanation is the fragmentation of leafy gametophytes. Previously, it was believed that this liverwort survived the Pleistocene glaciation in the montane zone, specifically in glacier-free areas, without dispersing during the postglacial period due to the absence of reproductive structures9. This assumption was supported by the limited number of known locations, all situated at lower mountain elevations, until the end of the 20th century9,15.

However, current evidence suggests that the montane populations of Arnellia fennica in the Tatra Mountains are secondary in nature. They likely originated from high-mountain populations following glacial retreat, as a result of vegetative reproduction (gemmae) dispersal. Notably, the lower-lying stands of A. fennica are often found in relatively wide gullies that facilitate the transport of water and snow, which may contain viable propagules. Examples of such gullies include Kalacki Żleb, Żleb pod Czerwienicą, Dudowe Spady, and Żleb Żeleźniak.

This dispersal mechanism explains the absence of Arnellia fennica in montane positions on limestone rocks in the Western Tatras, which lack high-mountain characteristics. Since there are no high-altitude populations of this liverwort in the vicinity, there is no source of propagules for colonization of these rocky outcrops. In such locations, stands of A. fennica could only originate from spores. However, genetic studies conducted by our team indicate that spores are absent in the Tatra Mountains. This further refutes the notion that A. fennica survived in montane positions, as the absence of spores precludes the establishment of high-mountain populations.

Another issue is explaining why Arnellia fennica is rare in the Tatra Mountains. The discovery of propagules makes this more confusing, but only superficially. The efficiency of this dispersal method in A. fennica is low. Only a few (even a negligible number) gametophytes produce gemmae. This atypical method of production on the plant results in the reproduction of the local population at a given site. Consequently, there is the expansion of the turf or the establishment of additional ones in close proximity. The main means for propagule transport is likely water, due to their positioning at the base of leaves and being covered by a pair of leaves below on the stem. Long-distance transport of propagules is thus impeded and occurs very rarely. This explains why there are few montane sites, and within gullies, A. fennica is usually found at only one locality.

An interesting aspect to consider is the lowest occurrence of Arnellia fennica in the Strążyska Valley (1040 m above sea level, collected by I. Szyszyłowicz15. Here, we may have an example of long-distance transport of propagules by the Strążyski stream. Almost in a straight line, populations are located above in the Mała dolinka Valley under Mt. Giewont. The question of the rarity of this plant in the high-mountain area remains to be explained. Due to the described specificity of propagule dispersal, the spread of this liverwort can only occur through spores. This explains the reason for the rarity of A. fennica throughout the Tatra massif. This aligns with the findings regarding intraspecific variation revealed by the analysis of eight A. fennica mitogenomes, plastomes, and nuclear rRNA clusters.

Liverwort’s organellar genomes are known to be conservative in structure and gene content34,35. Mitogenomes and plastomes of Arnellia fennica assembled in this study support this hypothesis. The mitochondrial genome of A. fennica contains a complete set of introns, as does its closest relative Gymnomitrion concinnatum, which is known for its unusual mitogenome rearrangements36. The plastome of A. fennica has a complete gene set, which is characteristic for the suborder Jungermanniineae, while in the remaining suborders of Jungermanniales some gene losses were confirmed35,37,38.

The phylogenetic analysis of leafy liverwort organellar genomes was congruent with previously published results and clearly supports the division of this group into orders and suborders. However, the phylogenetic position of Arnellia was not investigated using NGS methods in earlier studies. Analysis based on two chloroplast loci (rbcL and rps4) grouped Arnellia in a common clade with species of the genera Gyrothyra and Harpanthus, but without significant support39. The current dataset placed Arnellia as a sister to Gymnomitrion (Fig. 11), but the plastome or mitogenome sequences of Harpanthus and Gyrothyra were not available.

Despite extensive research into the plastid and mitochondrial genomes of liverworts, there is a notable lack of identified intraspecific variation within these organellar genomes35,37,40. The studies conducted so far have primarily focused on broader phylogenetic relationships, structural conservation, and evolutionary dynamics at the interspecific level and above34,36. This focus has highlighted the overall conservation of liverwort plastomes and mitogenomes, including gene content, structure, and order, across various lineages within the group. The inherent stability and the uniparental inheritance of these organellar genomes contribute to their reduced genetic variability, making them highly conserved across liverwort species. The organellar genomes of A. fennica confirm this pattern.

The current body of research offers limited insights into intraspecific variation of liverwort plastomes and mitogenomes. Most sequenced organellar genomes represent single accessions, and only a few studies have analyzed 2–4 samples per species38,40,40,41,43. Studies on the genus Calypogeia revealed limited variation, with only a few single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the plastome and mitogenome, even when analyzing specimens from distant geographic regions41,42. Similarly, the intraspecific variation between two European specimens of Nowellia curvifolia (Dicks.) Mitt. was found to be remarkably low based on analysis of organellar genomes. The mitogenomes and plastomes were nearly identical, differing only by a single SNP in intergenic spacers, despite sampling sites located 600 km apart38. This minimal variation highlights the genetic homogeneity within European populations of this species and aligns with the generally low intraspecific variation observed in leafy liverworts. In the simple thalloid liverwort Pellia endiviifolia (Dicks.) Dumort., comparative analysis of six complete chloroplast genomes from two cryptic species with contrasting habitat preferences (terrestrial and water forms) revealed higher variation at the intraspecific level. Specifically, the water form specimens differed by only two substitutions and three indels found in intergenic regions. In contrast, the typical (terrestrial) form specimens showed 21 substitutions and eight indels, including 15 in coding sequences38. However, plastomes of simple thalloid liverworts appear to evolve at a faster rate compared to other liverwort lineages43.

Considering the lack of sexual reproduction and the relatively close distance between the collection sites of the studied Arnellia fennica samples, the monomorphism of organellar genomes and NOR regions is not surprising. The clusters on nuclear rRNA genes usually evolve faster than organellar genomes, and in some vascular plant species, where plastid genomes failed as molecular markers due to a low number of polymorphic sites, can provide evolutionary insights44,44,46. The small polymorphism detected within all analyzed samples is rather connected to the nature of rRNA clusters, which are present in several copies, than with interindividual variation within patches, as all samples have similar variant frequencies.

The gap in our knowledge about infraspecific variation highlights the potential for future studies aimed at exploring the genetic diversity within liverwort species, which could reveal subtle variations and contribute to a deeper understanding of liverwort population genetics, adaptation, and evolution.

It remains an open question why Arnellia fennica in the Tatras produces male individuals, particularly since there is a lack (presumably, as they have not been found) of females. The literature mentions that perianths are very rarely produced in the area of the species’ compact distribution2,17. The presence of both sexes in the Tatras population is not supported by the results of our genetic studies based on organellar genomes, which resolved only one haplotype in all three genetic compartments. Mitochondrial and plastid genomes of leafy liverworts usually express low variation at the intraspecific level and cannot be used as an argument for rejecting the potential presence of females. Additionally, the nuclear multi-copy NOR regions, which are good indicators of recombinant events and efficient genotypic markers44,45, did not reveal any variation either. The maximum altitude of A. fennica in the Tatra Mountains is 1605 m above sea level. In this context, it is noteworthy to analyze the high-mountain character of the vertical distribution of this liverwort. Simultaneously, the limestone massifs in the Tatras, compared to the summits of crystalline rocks, are lower, and on the northern slopes of large rock formations like Giewont or Kominiarski Wierch, there are climatically lowered vegetation belts. The reference for these considerations will be the distribution of other Arctic-alpine liverworts in the limestone part of the Polish Tatras, based on our unpublished materials (a total of 150 sites). The following species were selected: Scapania gymnostomophila Kaal., S. cuspiduligera (Nees) Müll.Frib., and Schljakovianthus quadrilobus (Lindb.) Konstant. & Vilnet. The results indicate that the mentioned species have the highest number of occurrences in the altitude range of 1400–1600 m above sea level (Fig. 3). In this aspect, A. fennica conforms to the distribution pattern of other Arctic-alpine liverworts in the Tatras. Frequently, these plants grew together at the same locations. It is also possible to observe how the presence of propagules determines the potential dispersal of these calciphilic species, both in high-mountain and montane areas (S. gymnostomophila and S. cuspiduligera) and primarily in montane areas (A. fennica). The last species, Schljakovianthus quadrilobus, rarely produces gemmae17, and none have been recorded in the Tatra region (only specimens with perianths were observed twice; P. Górski). This also illustrates how the regular presence of propagules is associated with the widespread occurrence of these plants. Scapania cuspiduligera, which has the highest number of sites and often descends to lower elevations, produces them most abundantly and consistently. The lowest observation of it in the Tatras was in 2023 at the mouth of Dolina Białego Valley, near the stream, at an altitude of 937 (!) meters above sea level (POZNB 4575, P. Górski). It is noteworthy that among the species mentioned, similar to A. fennica, sporophytes are either unknown or rarely produced. In S. gymnostomophila, sporophytes are unknown (perianth observed 4 times in northern Europe, unobserved in the Tatra Mountains), in S. cuspiduligera - sporophytes are unknown (perianth often, male individuals rarely), and in Schljakovianthus, sporophytes have been observed twice in Sweden and Norway17,47 and P. Górski, personal observations). Another Arctic-alpine species, Mesoptychia heterocolpos (Thed. ex Hartm.) L.Söderstr. & Váňa, also rarely develops sporophytes17, but propagates abundantly, hence it is common in the Tatra Mountains (P. Górski, personal observations).

At the end of the considerations, it is worth mentioning areas where Arnellia fennica occurrences have not been confirmed. In Poland, this includes the large limestone massif of the Czerwone Wierchy, especially the north-facing walls from the Mułowa and Litworowa valleys. This liverwort has not been found in the Slovak Western Tatra, with particularly promising northern slopes of Mt. Osobitá. Additionally, this plant is absent in the Bobrovecká dolina and Juráňova dolina Valleys (with the Tiesňavy gorge). It has also not been observed in the Belianske Tatra despite the penetration of a large area adjacent to the northern side of the main ridge. This area represents the largest occurrence of limestone rocks in the entire Tatra range, with a significant habitat resource of Carici-Festucetum tatrae vegetation type. Professor J. Váňa, the author of the first report on A. fennica in this massif ()[15], searched for this plant in the Belianske Tatra, as communicated in electronic correspondence with P. Górski. Certainly, the Belianske Tatra requires further targeted field research to locate this plant.

Data availability

The raw reads were deposited in NCBI SRA archive under BioProject PRJNA1113346.2) The remaining raw data, containing detailed location information of the localities, are included in the article (see List of localities). The remaining raw data, containing detailed location information of the localities, are included in the article (see List of localities).

References

Söderström, L. et al. : World checklist of hornworts and liverworts. PhytoKeys 59, 1-821 (2016).

Schuster, R. M. The Hepaticae and Anthocerotae of North America. Vol. IV. (Columbia University Press, New York, 1980).

Crandall-Stotler, B. J., Stotler, R. E. & Long, D. G. Phylogeny and classification of the Marchantiophyta. Edinb. J. Bot. 66(1), 155–198. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0960428609005393 (2009).

Váňa, J., Grolle, R. & Long, D. G. Taxonomic realignments and new records of Gongylanthus and Southbya (Marchantiophyta: Southbyaceae) from the Sino-Himalayan region. Nova Hedwigia 95(1/2), 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1127/0029-5035/2012/0042 (2012).

Shaw, B. et al. Phylogenetic relationships and Morphological Evolution in a Major Clade of Leafy Liverworts (Phylum Marchantiophyta, Order Jungermanniales): Suborder Jungermanniineae. Syst. Bot. 40(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1600/036364415X686314 (2015).

Schuster, R. M. Austral hepaticae. Part II. Beihefte Zur Nova Hedwigia 119, 1–606 (2002).

Juárez-Martínez, C. & Ochoterena, H. Claudio Delgadillo-Moya, C. Cladistic analysis of the Stephaniellaceae (Marchantiophyta) based on morphological data. Syst. Biodivers. https://doi.org/10.1080/14772000.2015.1103322 (2015).

Inoue, H. Chromosome studies in some Arctic hepatics. Bull. Nat. Sci. Mus. Tokyo Ser. В (Botany) 2, 39–46 (1976).

Szweykowski, J., Koźlicka, M., Buczkowska, K., Chudzińska, E. & Barczak, H. Arnellia fennica (Hepaticae, Arnelliaceae) rediscovered in the Tatras. Fragmenta Floristica et Geobotanica 2 (1), 323–329 (1993).

Söderström, L., Urmi, E. & Váňa, J. Distribution of Hepaticae and Anthocerotae in Europe and Macaronesia. Lindbergia 27, 3–47 (2002).

Hodgetts, N. G. Checklist and Country Status of European bryophytes – towards a new Red List for Europe. Irish Wildlife Manuals, No. 84. (National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, 2015).

Ellis, L. T. et al. New national and regional bryophyte records, 53. J. Bryology 39(4), 368–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/03736687.2017.1384204 (2017).

Klama, H. & Górski, P. Red List of liverworts and hornworts of Poland (4th edition, 2018). Cryptogamie Bryologie 39(4), 415–441. https://doi.org/10.7872/cryb/v39.iss4.2018.415 (2018).

Górski, P. Red list of liverworts occurring in the Tatra Mountains (western carpathians, Poland and Slovakia). Nova Hedwigia Beiheft 150, 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1127/nova-suppl/2020/067 (2020).

Váňa, J. Arnellia fennica (Hepaticae) in den Karpaten. Preslia 47, 93–94 (1975).

Düll, R. Distribution of the European and Macaronesin liverworts (Hepaticophytina). (1983).

Damsholt, K. Illustrated Flora of Nordic Liverworts and Hornworts. 2nd edn (Nordic Bryological Society, 2009).

Radwańska-Paryska, Z. & Paryski, W. Wielka Encyklopedia Tatrzańska. (Wydawnictwo Górskie, 2004).

Nyka, J. Tatry Słowackie. Przewodnik. (Wydanie II, Wyd. Trawers, 2000).

Klama, H. & Górski, P. Red List of Liverworts and Hornworts of Poland4th edition, Cryptogamie, Bryologie 39, 4, 415–441. https://doi.org/10.7872/cryb/v39.iss4.2018.415 (2018).

Ochyra, R., Żarnowiec, J. & Bednarek-Ochyra, H. Census Catalogue of Polisch Mosses. (W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences, 2003).

Mirek, Z., Piękoś-Mirkowa, H., Zając, A. & Zając, M. Vascular Plants of Poland. An Annotated Checklist. (W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences, 2020).

Zasadni, J. & Kłapyta, P. The Tatra Mountains during the last glacial Maximum. J. Maps. 10(3), 440–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2014.885854 (2014).

Plášek, V., Sawicki, J., Seppelt, R. D. & Cave, L. H. Orthotrichum cupulatum HExfm. ex Vard. var. lithophilum, a new variety of epilithic bristle moss from Tasmania. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 92(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.5586/asbp/176370 (2023).

Sawicki, J. et al. Nanopore sequencing of organellar genomes revealed heteroplasmy in simple thalloid and leafy liverworts. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 92(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5586/asbp/172516c (2023).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 10(2), giab008. https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giab008 (2021).

Sawicki, J. et al. Nanopore sequencing technology as an emerging tool for studies diversity if plant organellar genomes. Diversity 16(3), 173. https://doi.org/10.3390/d16030173 (2024).

Kolmogorov, M., Yuan, J., Lin, Y. & Pevzner, P. A. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat. Biotechnol. 37(5), 540–546. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41587-019-0072-8 (2019).

Buczkowska, K. et al. Does Calypogeia azurea (Calypogeiaceae, Marchantiophyta) occur outside Europe? Molecular and morphological evidence. PLOS ONE 13(10), e0204561. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204561 (2018).

Zheng, Z. et al. Symphonizing pileup and full-alignment for deep learning-based long-read variant calling. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2, 797–803 (2022).

Revell, L.J. phytools: an R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things). Methods in Ecology and Evolution 3, 217–223. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00169.x (2012).

Szyszyłowicz, I. Hepaticae Tatrenses. O rozmieszczeniu wątrobowców w Tatrach. (Drukarnia Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, 1884).

Górski, P. & Váňa, J. A synopsis of liverworts occurring in the Tatra Mountains (western carpathians, Poland and Slovakia): checklist, distribution and new data. Preslia 86(4), 381–485 (2014).

Liu, Y., Cox, C. J., Wang, W. & Goffinet, B. Mitochondrial phylogenomics of early land plants: mitigating the effects of saturation, compositional heterogeneity, and codon-usage bias. Syst. Biol. 63, 862–878 (2014).

Yu, Y. et al. Chloroplast phylogenomics of liverworts: a reappraisal of the backbone phylogeny of liverworts with emphasis on Ptilidiales. Cladistics 36, 184–193 (2020).

Myszczyński, K., Górski, P., Ślipiko, M. & Sawicki, J. Sequencing of organellar genomes of Gymnomitrion concinnatum (Jungermanniales) revealed the first exception in the structure and gene order of evolutionary stable liverworts mitogenomes. BMC Plant. Biol. 18, 1–12 (2018).

Dong, S. et al. Plastid genomes and phylogenomics of liverworts (Marchantiophyta): conserved genome structure but highest relative plastid substitution rate in land plants. Mol. Phylogenet Evol. 161, 107171 (2021).

Sawicki, J., Krawczyk, K., Ślipiko, M. & Szczecińska, M. Sequencing of Organellar genomes of Nowellia curvifolia (Cephaloziaceae Jungermanniales) revealed the Smallest Plastome with Complete Gene Set and High Intraspecific Variation suggesting cryptic speciation. Diversity 13(2), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/d13020081 (2021).

Cailliau, A. et al. Phylogeny and systematic position of Mesoptychia (Lindb.) A. Evans. Plant. Syst. Evol. 299, 1243–1251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00606-013-0792-z (2013).

Sawicki, J. et al. The increase of simple sequence repeats during diversification of Marchantiidae, an early land plant lineage, leads to the first known expansion of inverted repeats in the evolutionarily-stable structure of liverwort plastomes. Genes (Basel). 11, 299 (2020).

Ślipiko, M. et al. Molecular delimitation of European leafy liverworts of the genus Calypogeia based on plastid super-barcodes. BMC Plant. Biol. 20, 243 (2020).

Ślipiko, M., Myszczyński, K., Buczkowska, K., Bączkiewicz, A. & Sawicki, J. Super-mitobarcoding in plant species identification? It can work! The case of leafy liverworts belonging to the genus Calypogeia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 15570 (2022).

Paukszto, Ł. et al. The organellar genomes of Pellidae (Marchantiophyta): the evidence of cryptic speciation, conflicting phylogenies and extraordinary reduction of mitogenomes in simple thalloid liverwort lineage. Sci. Rep. 13, 8303. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35269-3 (2023).

Szczecińska, M. & Sawicki, J. Genomic resources of three pulsatilla species reveal evolutionary hotspots, species-specific sites and variable plastid structure in the family Ranunculaceae. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 22258–22279 (2015).

Krawczyk, K. et al. Phylogenetic implications of nuclear rRNA IGS variation in Stipa L. (Poaceae). Sci. Rep. 7, 11506. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11804-x (2017).

Hemleben, V., Grierson, D., Borisjuk, N., Volkov, R. A. & Kovarik, A. Personal perspectives on Plant Ribosomal RNA genes Research: from Precursor-rRNA to Molecular Evolution. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 797348. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.797348 (2021).

Szweykowski, J. Scapania gymnostomophila Kaalaas: a new liverwort in the carpathians. Bull. de la. Société Des. Amis Des. Sci. et des. Lettres De Poznań Série B Sci. Matématiques et Nat. 14, 371–377 (1958).

Acknowledgements

We extend our thanks to the Directorate of the Tatra National Park (Poland) for supporting bryological research and granting permission to enter the area of Mt. Kominiarski Wierch. To Dr. Tomasz Zwijacz-Kozica and Dr. Antoni Zięba, we would like to express our gratitude for their assistance during the implementation of this project.

Funding

The research was funded by the Forest Fund through the State Forests (Poland). The publication was financedby the Polish Minister of Science and Higher Education as part of the Strategy of the Poznan University of LifeSciences for 2024-2026 in the field of improving scientific research and development work in priority researchareas.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.G.: Field research, Writing — original draft preparation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization, Funding acquisition; M.Sz: formal analysis, methodology, J.S.: formal analysis, visualization, writing — original draft preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Górski, P., Szczecińska, M. & Sawicki, J. Reproductive and persistence strategy of the liverwort Arnellia fennica after the last glaciation in the area of disjunction in Central Europe (Polish Tatra Mountains, carpathians). Sci Rep 15, 2030 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85757-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85757-x