Abstract

The ore mining sites commonly experience slope instability, which is causing concern for the workers’ safety and the operation’s stability. Considering the Ziluoyi iron ore mining site as a case study, uniaxial compression strength and shear tests are performed on the lower disk peripheral rock, ore body, and upper disk peripheral rock, leading to the extraction of compressive strength and elastic modulus (lower disk: 77.7 MPa–9.093 GPa; ore body: 19.6 MPa–4.619 GPa; upper disk: 55.47 MPa–5.573 GPa). Further, using the Hoek–Brown criterion in conjunction with the Moher–Columb criterion, the cohesion and internal friction angle of various samples are appropriately determined (lower disk: 21.124 MPa–35.614°; ore body: 21.66 MPa–26.5°; upper disk: 42.916 MPa–25.743°). By employing an appropriate rock mass reduction model, its constants (m and s) and RMR score for the consisting layers (schist layer and ore body) of the three understudy slopes (Slope#1–Slope#3) are evaluated. An effective algorithm based on the Morgenstern–Price method is employed and its effectiveness is also proved by comparing its factor of safety results with those of Geo-Slope for various slope structures subjected to different loads. Subsequently, the stability analyses of various slopes are methodically examined by predicting the factor of safety values under multiple types of loading (i.e., self-weight + groundwater, slope self-weight + groundwater + blasting vibration force, and self-weight + groundwater + seismic force). The factor of safety values of the slopes pertinent to Slope#1/Slope#2/Slope#3 subjected to the above loading conditions are obtained as 1.354/1.273/1.188, 1.326/1.239/1.169, and 1.321/1.232/1.162, respectively. Upon comparing these results with those of a valid homeland specification, it becomes clear that the results are able to meet safety standards and ensure efficient mine operation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a major resource-mining country, open-pit mining has taken up a large part of China’s mining industry as a crucial mining approach. The main safety problem that open-pit mines face is slope deformation and instability. Slope deformation is always associated with mining. With the continuous extraction of open-pit mines and deepening of mines, the problem of deformation and instability of slopes becomes more visible and constantly affects the safety and production of the mine. The susceptibility of slopes to deformation is mostly influenced by factors such as the type of rock, the valley shape, the angle of the slope, and the parameters of jointing1,2,3,4. Additionally, the method of excavation also plays a significant role in determining the stability of slopes. If the potential slope instabilities and safety issues are not paid attention to, it may cause loss of life and huge economic losses. Therefore, studying the deformation and failure mechanisms and stability of open-pit mines and waste dump slopes is more necessary and important now.

So far, many research works have been conducted to tackle the challenge of mine slope stability. For instance, Malkawai et al.5 performed a reliability analysis of slope stability via the Monte Carlo simulation method (MCSM) in conjunction with the first-order second-moment method of uncertainty. The obtained results revealed that the reliability index (β) is independent of the seed random number generator, and a sample size of 700 or more is recommended for the MCSM. Digvijay et al.6 presented a summary of various approaches for slope stability analysis. The main purpose was to explain the methodological assumptions, the factor of safety calculations, soil types and conditions, output applicability, and limitations, but no specific results from these methods were mentioned. Kolapo et al.7 utilized both linear equilibrium techniques and numerical modeling to assess slope stability in mining operations. The results provide an overview of several case studies of slope failure in mining operations that highlight the importance of monitoring and evaluating slope stability in mining operations. Nalgire et al.8 employed Geo-Slope software and a variety of finite slope stability techniques to perform stability analysis of the dump slope at the WCL Makardhokara-2 open-pit mine. The results were indicative of the fact that increasing the diameter of the soil nail could lead to an increase in the factor of safety (FOS), whereas increasing the spacing between the nails resulted in a reduction in the FOS. Wang et al.9 developed a safety factor calculation model for cemented tailings backfill in large depth-to-width ratio stopes accounting for the layer effect, top load, and lateral pressure coefficient. The results showed that the safety factor of cemented tailings backfills lessens with the increase in the top load, lateral pressure coefficient, and bulk density, whereas it exhibited an increasing trend with the increase of cohesion, internal friction angle, and bonding force ratio. Hu et al.10 conducted a stability analysis and confidence level assessment of backfill mining under high and steep rock slopes (HSRSs). For this purpose, Slide software and MCSM were utilized to examine the stability and failure probability of HSRSs. The backfill mining method showed better seismic stability and lower potential levels of destruction compared to the traditional open-stop mining method. Oo et al.11 analyzed the design and stability of multiple concurrently excavated veins in the Hermyingyi Tin-Tungsten (W-Sn) Nine, focusing on weak rock mass conditions and different mining methods. The performed study recommended the development of stopes with width dimensions lower than 3 m in all parallel multiple veins simultaneously in weak rock mass conditions to minimize potential stope failure. Zhang et al.12 examined and evaluated the landslide risk of stope slopes in high-altitude and cold mines, specifically focusing on the Dongbang slope of the Beizhan Iron Mine in Hejing County, Xinjiang. The landslide risk monitoring level of the Dongbang slope in the Beizhan Iron Mine was identified as level 2, which indicated the possibility of a slight landslide risk in such a frigid region. Ren et al.13 investigated slope failure mechanisms in the Changshanhao open-pit mine and developed an optimal drilling plan that ensures slope stability. The obtained results revealed that slope failures in Changshanhao open-pit mine occur in various forms such as wedge sliding, bedding sliding, and toppling failure. Jahanbakhshzadeh et al.14 proposed a new analytical approach to evaluate the stress state in backfilled stopes with inclined walls. The variations of stresses along the opening height and width, including the difference between the hanging wall and the footwall, were taken into account for various inclination angles of the walls. The research findings revealed the capabilities of the proposed solution in considering the non-uniform stresses along the opening width and providing a more inclusive understanding of the stress distribution in backfilled stopes with inclined walls. Jaiswal et al.15 introduced a novel classification system called “rock slope instability score (RSIS)” for assessing rock slope stability. It considered geological and geotechnical parameters, as well as the impact of human activities and triggering parameters, including those often overlooked in existing classifications due to climate change. Kundu et al.16 established novel methods for quantifying the kinematic susceptibility of rock slopes using adjustment factors of slope mass rating (SMR) by developing an automated computer application called EasySMR for calculating kinematic susceptibility and SMR. In another work, Ansari et al.17 examined the characteristics of phyllite-derived soil and its impact on hill slope instability along National Highway-7 in Uttarakhand, India. Four locations were studied, and stability analysis was carried out using different methods. In the performed investigation by Ansari et al.18, geotechnical data was collected from eight sites in the Lesser Himalayan region, showing that limit equilibrium analysis would have a better correlation with the discrete element method than finite element results. The study also suggested that a single mode of numerical analysis may not be enough to predict accurate results for initiating economic remedial measures. In another investigation, Nkanyane et al.19 examined slope failure susceptibility along the R37 road via DIPs and FLAC-Slope. One of the main objectives was to assess the impacts of strata orientation and water presence on slope stability, demonstrating that water presence decreases stability. The study highlighted toppling as the primary failure mode and emphasized the need for effective drainage, proactive monitoring, and advanced modeling techniques to ensure safer infrastructure and mitigate risks in regions prone to slope instability.

In addition, Mao et al.20 provided a robust assessment of rock slope stability in coastal areas by applying fuzzy set theory to Qslope classification. The obtained results emphasized a high degree of synergy and rapid stability assessment, which is essential for timely and effective hazard mitigation. Agbelele et al.21 employed the Bishop slice method, which combines both analytical and numerical approaches using the SLOPE/W module of GeoStudio 2018 R2 software. The investigation revealed that increasing soil cohesion is capable of enhancing slope stability, as indicated by safety factors obtained from both analytical and numerical methods. Rao et al.22 adopted the Bishop’s simplified method based on the limit equilibrium technique to perform a comparative analysis of two-dimensional and three-dimensional slope stability. The obtained results indicated that 2D slope analysis generally yields a more conservative estimate of the FOS compared to 3D analysis. Igwe and Chukwu23 examined the geotechnical parameters of the slopes, and the stability analysis was carried out using GeoStudio software developed by Geo-slope International Limited. The stability analysis of the mine tailing dumps at Enyigba, Southeastern Nigeria, indicated calculated safety factors ranging from 0.8 to 1.33, signifying critical to poor slope stability when exposed to landslide triggering agents. Bissaya et al.24 combined survey data with stereographic mapping to describe common networks in DIPS software. The kinematic analyses revealed the presence of stable, potential, and key blocks, with the most potential failure modes being the primary and secondary key-block patterns. Kenmoe et al.25 conducted the stability analysis of the cut slopes in the locality of Limbe via numerical modeling in the GeoStudio software, specifically using Bishop’s approach for Slope/W analysis. Field and laboratory works were conducted to collect data for analysis. The results were indicative of the fact that the studied slopes have safety factor values less than 1, which indicates their unstable character. Epada et al.26 conducted geophysical soundings, specifically vertical electrical soundings, with a Schlumberger electrode array configuration to monitor the behavior of electrical resistivity in landslides. The geoelectrical surveys lead to the establishment of a three-layered earth model with a conductive surface layer, an intermediate layer indicating the presence of an aquifer, and a relatively resistant deep layer. Ji et al.27 utilized Newmark’s sliding block theory to analyze the permanent displacement and calculate rotational displacement in the presence of horizontal ground acceleration history. The parametric studies indicate that reliability-based allowable displacement design is a promising approach for seismic slope analysis. Cheng and Lau28 addressed issues in the current design and construction of engineered slopes and presented alternative and more appropriate approaches for slope stability analysis and stabilization. The authors offered alternative approaches and practical recommendations for field investigation, design, and on-site implementation, with the aim of establishing best practices in the design and construction of engineered slopes. Zheng et al.29 analyzed slope stability using the elastoplastic finite element method, specifically focusing on the FOS calculations and the location of critical sliding surfaces. The investigators recommended adjusting the Poisson’s ratio to ensure that the inequality holds while reducing the strength parameters (c and φ) to obtain a high-precision FOS and a suitable distribution of plastic zones. Jiang et al.30 applied the partial order set theory to evaluate slope stability with an open-pit mine slope as an engineering background. The obtained results revealed that the evaluated stability conditions are consistent with the actual situation, thus confirming the rationality and applicability of the method. Yu and Xu31 mainly utilized both qualitative and comparative analyses to control the variables of single-row spacing and double-row spacing to explore the stability of determining pile spacing in slope engineering. The experimental data showed that the stability of the slope work could be effectively enhanced in the case of pile spacing of 2 m. Saim and Kasa32 aimed to analyze the FOS of slopes and determine the critical slip surface by using computer software based on the LEM and FEM. The obtained results revealed that the FOS values obtained by the FEM were generally high and the FOS values obtained by the LEM method were slightly lower. For each analysis and approach, the shape and location of the critical slip circle were almost the same. Li et al.33 proposed an intelligent prediction method for slope stability based on the improved pelican optimization algorithm (IPOA) and the optimized random forest (RF) algorithm. The results were indicative of the fact that the slope instability prediction model based on the improved IPOA and RF algorithms would be reliable and effective, and the prediction accuracy was up to 90.4%. Meko et al.34 implemented the finite element (PLAXIS 2D) and LEM (slide software) software to analyze the stability of two critical soil slope sections and two rock critical slope sections. The obtained results revealed that critical slope “Introduction” and “Engineering background and mining status” sections of the soil were in dry conditions and unstable under wet conditions. However, the critical rocky slope sections were stable in both dry and wet slope conditions. Kumar et al.35 discussed a probabilistic analysis of Mount St. Helens’ slope stability using a hybrid computational model, employing probability theory and statistics to map the uncertainties in rock parameters and evaluate the reliability index and probability of failure under seismic and non-seismic situations. In another work, Kumar et al.36 reviewed various methods for three-dimensional slope stability analysis developed since the 1970s, with specific applicability to distinct circumstances. The conducted research could serve to comprehensively present the various aspects of slope stability analysis.

In the present investigation, the evaluation of slope stability of several crucial slopes of the Ziluoyi iron ore mining site is of concern. For this purpose, uniaxial compression strength and shear tests are conducted on the lower disk peripheral rock, ore body, and upper disk peripheral rock at the Ziluoyi iron ore mining site. This is done to determine the compressive strength and elastic modulus of the samples. Using the Hoek–Brown criterion and the Moher–Columb criterion, the cohesion and internal friction angle of the different samples were calculated. Additionally, the constants (m and s) and rock mass reduction (RMR) score for the main consisting layer (i.e., schist layer and ore body) of the understudied slopes (Slope#1, Slope#2, and Slope#3) are evaluated via an appropriate RMR-based model. The stability analysis of the above-mentioned slopes is carried out using Geo-Slope and 3D Mine software, as well as an efficient algorithm based on the Morgenstern–Price approach. To this end, the factor of safety (FOS) values are predicted under different types of loading combination conditions, including self-weight + groundwater, slope self-weight + groundwater + blasting vibration force, and self-weight + groundwater + seismic force. In several cases of loading scenarios, the predicted FOSs by the proposed algorithm are verified with those of Geo-Slope, and a reasonably good agreement is achieved. Subsequently, the FOS values for the slopes pertaining to Slope#1/Slope#2/Slope#3 under the above loading conditions were found to be 1.354/1.273/1.188, 1.326/1.239/1.169, and 1.321/1.232/1.162, respectively. Upon comparing these results with an appropriate specification, it could be concluded that they meet safety standards and ensure efficient operation of the mine.

Engineering background and mining status

Engineering background

Ziluoyi iron ore mine is located in Aketao County, Kizilsu Kirgiz Autonomous Province, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. The corresponding geographic location map has been presented in Fig. 1a. The mining approach utilized in this mine is open pit mining and is in the early stages of the open infrastructure operation. The understudied iron mine mainly consists of three waste dumps, which are denoted by Waste Dump#1–3 (see Fig. 1b). The main characteristics of these dumps are as follows: Waste Dump#1: the eastern dry selection station, slope height 78 m, average slope angle 23°, base angle 10–17°; (2) Waste Dump#2: slope height 159 m, average slope angle 30°, average base angle 25°; (3) Waste Dump#3: slope height 318 m, average slope angle 35°, average base angle 34° (see Fig. 1). The average thickness of the ore body is 40.31 m, the average TFe grade is 36.17%, and the average mFe grade is 32.01%. The mining area possesses simple tectonics, and monoclinic tectonics, with an approximately east-west strike, a northward tendency, and a dip angle of 45° to 55°. The terrain is generally high in the west, low in the east, high in the south, and low in the north, and the terrain is more undulating. The mining area has a plateau continental climate, which is cold in winter and mild in summer. The mining area is windy, with long frost-free periods, large temperature differences between day and night, and abundant sources of light and heat. The Kushan River is located 1 km northeast of the mine, which can supply the mine’s water demand.

Three inspection lines have been considered in the stope, which is represented by Slope#1, Slope#2, and Slope#3. The upper part of Slope#1 line denotes the original rock step after stripping. Slope#2 line represents east-west-oriented, consisting of six original rock steps. The Slope#3 test line is located on the west side of the mining range. The layout of these lines is illustrated in Fig. 1b. Additionally, three subfigures 1c-e have been provided by manually pulling the wire to cut the section and importing them into Auto CAD via 3D Mine software.

(a) Geographical location of the mine in Xinjiang Province; (b) Three-dimensional topographical map of the Ziluoyi open-pit iron mine and its main stopes and waste dumps created by 3D Mine 2023.03 https://www.3dmine-cn.com/index.php?m=content&c=index&a=lists&catid=8; (c) Slope#1; (d) Slope#2; (e) Slope#3.

Current status of the understudied slopes

The profile shape of Slope#1, as illustrated in Fig. 1c, has a slope height of 160 m, an overall slope angle of 34°, and a maximum step slope angle of 63°, which satisfies the initial design requirements. The top lines of the fairly horizontal step slope at levels 4237, 4261, 4285, and 4309 m have some collapse, and the width of the safety platform does not meet the requirements of 8 m.

The profile shape of Slope#2, as presented in Fig. 1d, has a slope height of 94 m, an overall slope angle of 22°, and a maximum step slope angle of 59°, in accordance with the initial design requirements. The top lines of the horizontal step slope at levels 4321 and 4309 m have a certain collapse, and the width of the safety platform does not meet the requirements of 8 m.

The profile shape of Slope#3, as illustrated in Fig. 1e, has a slope height of 251 m, a slope angle of 28°, and a maximum step slope angle of 61°, which meets the initial requirements. The existing slope represents a natural slope with a transport channel embedded in its upper part.

Materials and methods

Mineral rock sample collection and processing

Herein, the reference standard employed for rock sampling is “Methods for Determining the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Coal and Rock; Part I: General Requirements for Sampling (GB/T 23561.1–2009)”37. In addition, this recommendation plus to “Standard of Testing Methods for Engineering Rocks Mass (GB/T 50266 − 2013)”38 are utilized for further specimen processing and testing.

Mineral rock sample collection

According to the current production situation of Ziluoyi Iron Mine and the recent mining and stripping plan, the samples were sampled on the ground, as shown in Fig. 2. In this sampling, large rock samples are selected in the stope, and no obvious joints or cracks are detected in the rock blocks, thereby, the selected rock blocks would be hard enough and almost with their full-strength capacity will undergo the applied loads. In addition, the rock blocks are cubic and the size is not less than 300 mm × 300 mm × 300 mm as much as possible. If joints and cracks are developed, the rock strength is low, or the large rock samples mentioned above cannot be extracted. In such a case, smaller rock blocks can be taken, however, the minimum size of which should not be lower than 200 mm × 200 mm × 200 mm, and the number of rock samples should be increased accordingly. By the way, the number of rock samples in each layer in each site is not recommended to be less than six. After the rock samples are appropriately extracted, it is quickly wrapped and sealed with plastic film and tape.

Processing of mineral rock specimens

First, the ore rock block was drilled with a diamond drill to extract a 50 mm diameter ore sample. Then, the ore rock specimens are sawed into a cylindrical shape with a diameter of 50 mm and a height of 100 mm by implementing a rock sawing machine. During sawing, water was utilized to cool the sample and the cutter as well. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the end of the sample was flattened and cooled with emulsion.

Experimental procedure

The testing equipment adopts the E45.605 mining rock mechanical properties testing system, which benefits three closed-loop control modes, including stress, strain, and displacement. This device is capable of calculating the maximum compressive strength, shear strength, elastic modulus, and other strength parameters of the mining rock mass.

Uniaxial compression strength

To proceed with the uniaxial compression strength, the sample should be placed in the center of the bearing plate of the material testing machine. To this end, we should adjust the spherical seat so that the center line of the testing machine, the upper and lower bearing plates, and all nine samples are suitably positioned in a straight line, and therefore, the force applied on the top and below the specimen will be almost uniform. Let us start the material testing machine sample at a loading rate of 0.5 MPa/s to 1.0 MPa/s until failure and then record the load degradation. According to the reported load and strain at the time of the specimen’s failure, the corresponding single-pump compressive strength of the mineral rock body can be readily calculated as follows: \({R}_{c}=\frac{P}{F}\), where \({R}_{c}\) represents the compressive strength of specimens (unit: MPa), P denotes the specimen breaking load (unit: N), and F signifies the initial cross-sectional area of the specimen (mm2).

Shear test

The samples are placed in a plate shear machine with a variable angle and subjected to a shear test at five different angles of 40°, 45°, 50°, 55°, and 60° (fifteen samples in total, three samples for each angle chosen for the shear test with loading rate of 0.8–l.2 mm/min) until the samples fail and the failure load is recorded. The curve was fitted with the best method using shear stress as the vertical coordinate axis and positive normal stress as the horizontal coordinate axis, and the internal friction angle and rock cohesion were obtained in the diagram. The shear stress (τ) and positive normal stress (σ) can be correlated to the exerted load (P) in the following form:

where P represents the specimen shear damage load (unit: N), α is the angle between the specimen and the horizontal plane (unit: °), and F denotes the shear surface area (unit: mm2).

Determination of the physical and mechanical parameters of geotechnical bodies

Rock shear strength

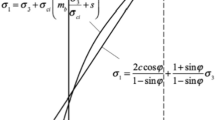

The Mohr-Coulomb’s strength curves can be evaluated by Eq. (2) and the positive normal stress and the shear stress on the rupture surface can be calculated as:

where \({\sigma}_{1}\) denotes the maximum principal stress at failure, \({\sigma}_{3}\) represents the minimum principal stress acting on a rock specimen, and \({\sigma}_{c}\) signifies the uniaxial compressive strength of the rock mass. In addition, m represents the material constants of the rock mass, depending on the nature of the rock mass.

Substituting the corresponding sums into Eq. (2) shows the coordinates of the points on the Moore envelope relative to the plane and in it, giving n parameter points. Then, the point data of these parameters are appropriately regressed to determine the rock shear strength parameters. Based on the Hoek–Brown scheme to evaluate the rock mass shear strength parameter, the key point is the selection range, and its best range is given by 0 < \({\sigma}_{c}\) < 0.25.

Theoretical foundation

The safety of a non-coal surface mine slope is mainly related to the slope self-weight, slope angle, groundwater, seismic force, and other factors, and its safety level is related to the slope height and slope hazard level.

According to “Technical Specification for Slope Engineering of Non-Coal Surface Mines (GB51016-2014)”39, the hazard level of the surface mine slope could be divided according to Table 1.

In addition, the safety classification of open slope work based on the slope height and slope hazard level are presented in Table 2.

According to the requirements of “Technical Specification of Non-Coal Open-Pit Mining Slope Engineering Technology (GB51016-2014)”39, the evaluation of this acquisition field is considered for the following three loading conditions:

Load combination I (slope self-weight + groundwater);

Load combination II (slope self-weight + groundwater + blasting vibration force);

Load combination III (slope self-weight + groundwater + seismic force).

The design factor of safety for overall slopes under different load combinations shall meet the required factor of safety as specified in Table 3.

Limit equilibrium analysis (LEA) based on the Morgenstern–Price approach

Herein, limit equilibrium analysis is carried out to assess the stability of the understudied slopes. Compared with the traditional bar-splitting methods (Swedish bar-splitting method, simplified Bishop’s method), the Morgenstern–Price (M–P) method40,41 is commonly recognized as the best bar-splitting method for evaluating the factor of safety of an arbitrarily shaped slip surface, as demonstrated in Fig. 3a. The basic idea is that the soil body of the landslide is appropriately divided into n soil vertical strips (\((1 \le i \le n)\)). Let us take the i-th soil strip with horizontal width bi and tangential width li for the mechanical analysis, and the associated applied forces on this vertical element include the self-weight of the soil strip Wi, the horizontal force Qi, the normal inter-strip force Ei and Ei+1, the tangential inter strip force Xi and Xi+1, and the normal counterforce Ni and the tangential force Ti at the bottom surface of the element (see Fig. 3b).

Commonly, the limit equilibrium formulation such as the M–P method does not employ Young’s modulus (E) in assessing the stability of the soil slope. This approach is mainly based on the effective parameters of the soil (effective cohesion, effective internal friction angle, pore pressure), as well as the geometrical data of the slope. The M–P method considers both normal and tangential equilibrium, along with the moment equilibrium for each slice.

This approach is applicable to both circular and noncircular slip surfaces. For example, compared to the simplified Bishop method, which considers only vertical and overall moment equilibriums and zero interslice shear force and applies to only circular slip surfaces, the M–P method is more general than this approach based on the above-mentioned main assumptions. Given the above-mentioned explanations, the M–P approach has been extensively utilized as an effective approach for evaluating the factor of safety of various slopes.

In Appendix A, the basic formulations used for the evaluation of FOSs under the action of groundwater, seismic, blast loading and their combinations based on the pseudo-static analysis and the M–P approach have been provided in some detail.

Software-based and M-P-based algorithm calculation procedures

Based on the effective M-P-based algorithm developed for evaluating the FOS of the slope structure in Appendix A.1 and its application to various loading scenarios displayed in Appendices A.2–A.4, we can effectually assess the FOS of various slopes with arbitrarily sliding surfaces for a wide range of important externally applied loading with self-weight. The calculations based on this algorithm have been performed by considering the initial values of \({F}_{s}=1.001\) and \(\lambda=0.001\) and the inter-element function of \(f\left(x\right)=\text{sin}x\). However, further computations reveal that the choice of this function has a trivial effect on the predicted FOS under various loading conditions. Additionally, the values of both \({e}_{1}\) and \({e}_{2}\) are set equal to 0.01, ensuring the required convergency in the performed stability analyses for each slope structure. The main sources of vibrations are related to the earthquake loading and the blasting loading of the nearby mining operations as each one has been technically explained in the following parts.

Based on China’s 2000 seismic ground motion zonation map42, seven distinct zones with different seismic peak ground acceleration (PGA) values can be detected as follows: (Zone#1) less than 0.05 g, (Zone#2) 0.05 g, (Zone#3) 0.10 g, (Zone#4) 0.15 g, (Zone#5) 0.20 g, (Zone#6) 0.30 g, and (Zone#7) greater than 0.40 g. The class of site (medium hard) and the probability of exceedance (10% over 50 years) were considered while creating the map. By this view, based on the zonation map location of the Ziluoyi iron ore mine, the PGA of the site was found to be 0.20 g. It should be noted that the seismic coefficients associated with acceleration values are generally lower than those corresponding to the PGA values. It is also important to note that selecting coefficients for slope stability analysis is somewhat subjective and lacks clear justification. For further stability analysis of the slope under horizontal earthquake loading, and based on previous works43,44,45 and considering various issues, a \({K}_{h}\) value of 0.12 is taken here for the case of seismic loading. In addition, further calculations based on the explosive quantity and the distance of the measuring point from the center of the explosion point using the relations given in Appendix A.3 lead to Kh = 0.112 for the case of blast loading.

The blast loading at the Ziluoyi iron ore mining site mainly arises from vibrations caused by nearby blasting activities. These operations are essential for fragmenting rock to extract ore, but they generate significant seismic waves that can impact adjacent structures and equipment. Factors such as the type and quantity of explosives, blast depth and distance from the ore mining site, and the geological makeup of the area can influence the intensity and frequency of these vibrations. To minimize their effects, engineers can implement vibration monitoring and adjust blast designs or timing accordingly, ensuring safety and preserving structural integrity in the surrounding environment. The detailed calculations of the blast loading and its role in the stability of the under-consideration slopes are given in Appendix A.4.

In the present investigation, slope stability is also evaluated based on Geo-Slope, 3D Mine, and Auto CAD software for the sake of comparison. The specific calculation steps have been presented in Fig. 4.

Methods of rock mass reduction

Although rock samples are taken from a natural rock body and prepared in a laboratory, they no longer represent the true mechanical properties of the natural rock body. This is because the samples lack weak structural surfaces that are unique to natural rock bodies and contribute to their overall integrity. Therefore, using laboratory-prepared rock samples alone to describe the mechanical properties of a natural rock body may not provide an accurate representation. Therefore, the mechanical parameters measured in the laboratory should be appropriately reduced by a certain percentage before applying them to natural rock bodies. The commonly used methods for rock mass reduction include the Fesinko method, the Gergi method, the empirical reduction method, and the Hoek–Brown criterion.

The Hoek–Brown strength criterion separates the determination of the rock mass index from the determination of the rock strength parameters. To this end, the rock mass index is estimated from geological field investigations, and then the rock strength criteria are rationally characterized based on empirical equations. Finally, the above two crucial factors are appropriately combined by reasonably establishing the relationships between the rock mass index and the empirical strength criterion. The Hoek–Brown empirical equations are the preferred and more popular method to determine the mechanical relationship between rock mass and rock.

The relationship between the principal stresses at the failure of the rock mass and those of the rock body reads:

where m and s represent the material constants of the rock mass, depending on the nature of the rock mass.

The RMR-based grading approach employs a multi-factor score and then its algebraic sum (RMR value) is appropriately utilized to assess the rock quality. The main six factors involved in grading are the uniaxial compressive strength of rock, rock quality designation (RQD), joint spacing, joint properties, groundwater status, and the effect of structural surface yield on slope engineering. The RMR scores of quartz schist and ore body, as well as the complete rock strength data, can be obtained from the physical and mechanical tests of the geotechnical body. The RQD value is commonly evaluated by core drilling and the rock quality is assessed based on the RQD index. Based on on-site geological records, geological surveys, and hydrogeological data reviews, we can obtain the geotechnical body joint spacing, joint conditions, groundwater conditions, and other parameters.

Results and discussion

Uniaxial compression test

The stress–strain curves of the uniaxial compression test of the coal seam and its top and bottom disk rocks are illustrated in Fig. 5, and the main results are presented in Figs. 6 and 7.

In Fig. 5a, various stages of cracking and development of microcracks within a sample under a uniaxial compression test have been displayed. Taking sample 03 as an example, the crack-initiation stress (\({\sigma}_{ci}\)) can be defined as the axial stress at which dilation begins, marked by the onset of a negative value on the crack volumetric strain-axial strain curve. On the other hand, the crack-damage stress (\({\sigma}_{cd}\)) is the stress level at which the axial strain starts to deviate from linearity. When the stress levels exceed this point, the material incurs damage that cannot be further tolerated under a permanent load. Additionally, the crack-damage stress (\({\sigma}_{cd}\)) also denotes the axial stress level at which the total volumetric strain reverses, and the failure stress (\({\sigma}_{f}\)) represents the maximum bearing stress of the sample just a short time before the final breakage and destruction.

According to the test results, the uniaxial compressive strength of the lower disk enclosing rock is between 66.9 and 86 MPa, with an average value of 77.7 MPa, and the modulus of elasticity is predicted to be in the range of 8.708–9.624 GPa, with an average value of 9.093 GPa. In addition, the uniaxial compressive strength of the upper disk enclosing rock ranges from 47.1 to 64.8 MPa, with an average value of 55.47 MPa, and the corresponding modulus of elasticity is estimated to be 4.991–5.976 GPa, with an average value of 5.573 GPa. Finally, the uniaxial compressive strength of the ore body varies from 18 to 21.1 MPa, with an average of 19.6 MPa, and the corresponding elastic modulus varies from 4.206 to 4.903 GPa, with an average of 4.619 GPa.

According to the “Engineering Rock Classification Standard46”, rock with uniaxial compressive strength in the range of 15–30 MPa is classified as softer rock, that in the interval of 30–60 MPa is categorized as harder rocks, and that greater than 60 MPa is classified as hard rocks. Concerning this classification and the results obtained in the above paragraph, the lower disk enclosure, upper disk enclosure, and ore body mostly represent hard rock, harder rock, and softer rock, respectively.

Shear test

The shear stress and shear displacement for each sample can be calculated by utilizing Eq. (4):

where \(\tau\) denotes the shear stress (unit: kPa), \(\varDelta L\) is the shear displacement (unit: 0.01 mm), \(C\) is the calibration coefficient of the measuring force of the ring (unit: kPa/0.01 mm), \(R\) represents the measuring force ring micrometer reading (unit: 0.01 mm), \(\varDelta{L}^{{\prime}}\) denotes the shear displacement of the rotating wheel to turn a revolution (unit: 0.001 mm), and \(n\) is the number of revolutions of the rotating wheel.

The τ–ε curve of the ore body and its top and bottom disk rock shear tests under various angles have been illustrated in Fig. 8, whereas the τ–σ strength curves of different parts have been illustrated in Fig. 9.

According to the test results given in Fig. 9, the cohesion and the internal friction angle of the lower disk enclosing rock in order are predicted to be 21.124 MPa and 35.614°. The cohesion and the internal friction angle of the upper disk enclosure are obtained as 42.916 MPa and 25.743°, respectively. Finally, the cohesion of the ore body is predicted to be about 21.66 MPa, and the internal friction angle is obtained as 26.5°.

Determination of the physical and mechanical parameters of geotechnical bodies

The specific RMR scoring process for quartz schist and iron ore bodies is demonstrated in Tables 4 and 5.

According to Tables 4 and 5, the quartz schist exhibits an RMR score of 40, an m-value of 0.061, and an s-value of 0.000003. The iron ore body demonstrates an RMR score of 62, an m-value of 1.231, and an s-value of 0.00293.

The failure limits of quartz schist and iron ore bodies based on Mohr’s circles and strength envelopes have been also presented in Fig. 10a,b.

Using the presented results in Fig. 10a,b, the rock mass strength parameters can be derived by performing rock mass parameter calculations based on the Hoek–Brown criterion (see Table 6):

Stability analysis of the main stope slopes

In this subsection, the safe ranges of FOS values for different slope stopes under the actions of three loading conditions based on GB51016-201439 are first presented. Subsequently, by employing the pseudo-static approach and the LEA, as explained in “Limit equilibrium analysis (LEA) based on the Morgenstern–Price approach” section and Appendix A, we proceed with calculating the FOSs of the understudied slopes of Slope#1–Slope#3 under various load scenarios. In the subsequent parts, we will give a discussion on the obtained results, and the achieved results are compared with those of recommended ones by the above specification, and complementary explanations are also given. In continuing, the potential future works are also explained and displayed briefly.

Safety reserve factors for different stope slopes

Up till now, physical models have been also implemented for examining the stability of soil and rock slopes. In this regard, Cheng et al.47 conducted a series of large-scale model tests of expansive soil slope, demonstrating the nonuniform distribution of water content, resulting in nonuniform swelling deformation. The finite element method with an expansive model yielded a safety factor of 0.92. In another work, Alejano et al.48 reviewed footwall slope failure mechanisms, presented different techniques for obtaining FOSs, and conducted physical models to validate the approaches. It was strongly recommended to use FOS in the range of 1.4 to 1.5 for the actual slope design based on the observed differences. In the following, the allowable FOSs for the understudied slopes under various loading scenarios are displayed.

According to the heights of the understudied slopes and their corresponding hazard levels in view of Tables 1, 2 and 3 using specification GB51016-201439, the slope safety reserve factors for each quarry subjected to various load combinations can be obtained, as presented in Table 7.

In the following subsections, we evaluate the factor of safety of the three stope slopes at hand in the presence of various load combinations (I, II, and III) and then compare the predicted FOS values with those suggested by GB51016-201439 in Table 7. This will be beneficial in better judging the stability of the understudied slopes and possibly suggesting practical ways to enhance their stabilities.

Slope stability analysis of Slope#1, Slope#2, and Slope#3

First, we perform a comparison study to examine the capabilities of the proposed M-P-based algorithm in predicting the FOS of the planner slope structures associated with different stopes studied here. To this end, the predicted FOS values of such a slope under loading conditions I and III have been provided in Table 8. As is seen, in all studied cases, the proposed M-P-based algorithm is capable of capturing the FOSs obtained by Geo-Slope with a high level of accuracy. However, in the loading case of “self-weight” + “groundwater” + “seismic force”, the relative discrepancies between the results of these two approaches are slightly greater than those of the “self-weight” + “groundwater” loading case.

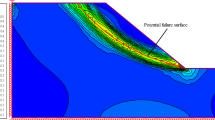

The variously employed load combinations and the calculation results of FOSs using the Geo-Slope software for assessing the stability analysis of the slope structures pertinent to Slope#1, Slope#2, and Slope#3 under various loading scenarios, as well as their corresponding sliding surfaces, have been presented in Figs. 11, 12 and 13.

Stability calculation results of the main slope of Slope#1: (a) Load combination I (slope self-weight + groundwater); (b) Load combination II (slope self-weight + groundwater + blasting vibration force); (c) Load combination III (slope self-weight + groundwater + seismic force) (note: the domains with dark-green, red, and light-green colors in order represent the quartz schist, the iron ore, and the slope prone to failure).

Stability calculation results of the main slope of Slope#2: (a) Load combination I (slope self-weight + groundwater); (b) Load combination II (slope self-weight + groundwater + blasting vibration force); (c) Load combination III (slope self-weight + groundwater + seismic force) (note: the domains with dark-green and light-green colors in order represent the quartz schist and the slope prone to failure).

Stability calculation results of the main slope of Slope#3: (a) Load combination I (slope self-weight + groundwater); (b) Load combination II (slope self-weight + groundwater + blasting vibration force); (c) Load combination III (slope self-weight + groundwater + seismic force) (note: the domains with dark-green and light-green colors in order represent the quartz schist and the slope prone to failure).

A discussion of the predicted stability analysis results

According to the plotted results in Fig. 11a–c, the predicted FOS values of Slope#1 under the load combinations of self-weight + groundwater, self-weight + groundwater + blasting vibration force, and self-weight + groundwater + seismic force in order are predicted to be 1.354, 1.273, and 1.188. As is seen, by inducing vibration from the ground in both blast and seismic loading cases, the predicted FOSs would reduce. A close comparison between the above-mentioned FOSs and those safe range values given for Slope#1 in Table 6 reveals that all the above-predicted values are on the safe side for various loading conditions. This indicates that the slope of Slope#1 satisfies the minimum stability requirements of the slope based on the specification GB51016-201439. Therefore, the slope of Slope#1 remains stable subjected to various loading conditions.

Concerning the slope of Slope#2, as illustrated in Fig. 12a–c, we obtain FOS = 1.326, 1.239, and 1.169 under self-weight, self-weight + groundwater, self-weight + groundwater + blast, and self-weight + groundwater + seismic loading conditions, respectively. On the other hand, according to Table 5, Slope#2 is mainly categorized as a slope with a slope hazard level of II and a slope safety level of III. Based on the specification GB51016-201439, the suggested FOS ranges for the design of the slope of Slope#2 under the action of the above loading combinations are obtained as 1.1–1.15, 1.08–1.13, and 1.05–1.10, respectively. As it is obvious, those FOSs predicted by the numerical scheme are all out of the aforementioned ranges and all of them are also greater than the maximum values suggested by GB51016-201439. This clearly indicates that the studied Slope#2 would be also highly stable based on GB51016-201439 under various scenarios of loading.

From Fig. 13a–c, the numerically predicted FOS values for the main slope of Slope#3 subjected to self-weight, self-weight + groundwater, self-weight + groundwater + blast, and self-weight + groundwater + seismic loading conditions in order are 1.321, 1.232, and 1.162. According to the presented results in Table 4, this slope is basically classified as grade III in both slope hazard and safety levels, resulting in the FOS ranges of 1.1–1.15, 1.08–1.13, and 1.05–1.10 for the above-mentioned loading scenarios. As is seen, all the above-predicted values are still higher than those of the greatest values recommended by the specification GB51016-201439; therefore, Slope#3 would be also stable under various loading conditions. Another important issue is that the predicted FOSs for the slope of this stope are lower than those of Slope#1 and Slope#2, indicating that the slope of Slope#3 is more prone to instability among these three cases. As a result, special applicable treatments should be applied to enhance the stability of the slope of Slope#3.

For all studied slopes (i.e., Slope#1–Slope#3), the predicted factor of safety values for the loading scenario of “Load combination III (slope self-weight + groundwater + seismic force)” are lower than those obtained for the loading scenario of “Load combination I (slope self-weight + groundwater)”. This result is also consistent with findings from other investigators49,50,51,52 who have elucidated that soil and rock slopes are generally more prone to instability under seismic loading.

Some general guidelines for enhancing stability

The following measures can be taken to prevent the destabilization of the slopes of the stope and to improve their stability under various combinations of loads:

-

1.

As explained in A discussion of the predicted stability analysis results section, the predicted FOS of various slopes acted upon by “self-weight + groundwater + seismic” are very close to the upper values of safe intervals of FOS suggested by the specification GB51016-201439. For example, regarding Slope#3, the predicted FOS by the modified M-P-based algorithm overestimates FOS’s upper value of the specification by only about 5.6%. This indicates that if the slopes could be suitably stabilized geometrically, mechanically, or by a combination of these two, the above-mentioned upper values can be more safely satisfied. More specifically, the feasible ways to enhance stability against dynamical loading include altering slope geometry, installing drainage, reinforcing the rock (via anchorages, prestressed cables, bolts, piles, and so on), or a combination of these techniques. For example, installing bolts in rock slopes is an effective approach used to enhance the stability and safety of steep terrain. The bolts can be anchored to the ground or other rock formations, distributing weight, and reducing the risk of movement in unstable areas. Proper installation is critical, as it ensures that the bolts effectively engage with the rock and provide the necessary support to enhance slope stability.

-

2.

Further calculations reveal that in most cases, the externally applied surcharge, seismic, and blast loading are incorporated into the reduction of the slope stability; however, there are some effective ways to enhance the slope stability. For example, it has theoretically/analytically proved that utilizing multiple sets of anchors with different orientations can provide a cost-effective way to fully stabilize a rock slope53. A graphical representation also illustrated that when one set of anchors is inclined at a specific angle to the normal at the failure plane, variations in the inclination of the second set of anchors by more than approximately 60 degrees do not significantly impact the FOS of the reinforced system. The importance of utilizing an anchorage system and its role in enhancing the stability of rock slopes was also highlighted by other investigators54,55,56; as a result, an appropriate anchorage system can be regarded as an effective reinforcing system against horizontal dynamical loadings.

-

3.

Monitoring slope deformation is crucial, especially during the freezing and thawing seasons and periods of heavy rainfall. These environmental conditions can significantly impact the stability of slopes, leading to potential hazards such as landslides and slope failure. By closely monitoring slope deformation during these periods, engineers and geologists can better understand the behavior of the slope and assess the risks involved. During the freezing and thawing seasons, the expansion and contraction of soil and rock materials can exert pressure on the slope, potentially leading to deformation. Similarly, heavy rainfall can saturate the soil, increasing its weight and reducing its shear strength, thereby making the slope more susceptible to movement. As is seen, both phenomena could be incorporated into the reduction of the slope stability. Continuous monitoring of slope deformation through techniques such as inclinometers, GPS monitoring, and remote sensing technologies allows for early detection of any adverse changes in the slope. This early warning system can help in implementing timely mitigation measures to prevent potential disasters. Hence, given the potential risks associated with slope deformation during freezing, thawing, and heavy rainfall, monitoring these parameters is essential for ensuring the safety of infrastructure and communities situated in these areas.

Future prospects

Herein, we employed RMR–based grading to assess the general rock quality of both quartz schist and ore body; however, SMR or CSMR or China SMR can provide more accurate grading frameworks and thereby can be utilized for complementary research works in the near future.

Additionally, stability analysis can be generally a complex and challenging task, particularly when dealing with large and complex geological formations. It often requires the exploitation of advanced mathematical and computational models to simulate the behavior of soil and rock masses and predict their response to various external factors. In recent years, there has been a growing interest in applying machine learning techniques to geotechnical engineering57,58,59 to improve the accuracy and efficiency of stability analysis. Machine learning (ML) algorithms60,61,62,63,64,65 can be trained on large datasets of geological and geotechnical data to learn patterns and relationships between different variables and predict the behavior of soil and rock masses under different conditions. This can help engineers and geologists make more informed decisions and design safer and more reliable engineering structures.

In addition, the exploitation of the three-dimensional Hoek–Brown strength criterion of rocks66,67,68,69,70 in conjunction with the three-dimensional modeling of slope stability can lead to more accurate results for FOS values of various slope stopes under different loading scenarios. The above-mentioned issues can be considered as important directions for future works, aiming at increasing our knowledge of the novel aspects of slope stabilities of both soil and rock media.

Concluding remarks

This article deals with the mechanical analysis and evaluation of the slope stability of the Ziluoyi iron ore mine as a case study based on geotechnical and geomechanical experiments, as well as numerical investigations, under various loading conditions. The main obtained results can be summarized as follows:

-

1.

Through the experimental study of the ore body and the surrounding rock samples of the upper and lower pans of the understudied mine, the main mechanical parameters of the representative rocks in the mine area are obtained as follows. The compressive strength and elastic modulus of the rocks of the lower pan in order are obtained as 77.7 MPa and 9.093 GPa, whereas the corresponding internal friction angle and cohesion based on the Hoek–Brown criterion and Moher circles in order are predicted to be 35.614° and 21.124 MPa. Furthermore, the compressive strength and elastic modulus of the rocks of the upper pan are obtained as 55.47 MPa, and the corresponding internal friction angle is predicted as 25.743°. In addition, the compressive strength and elastic modulus of the ore body are obtained as 19.6 MPa and 4.619 GPa, whereas the corresponding internal friction angle and cohesion are predicted to be 26.5° and 21.66 MPa.

-

2.

The slope layer of the mine is mainly composed of quartz schist and iron ore bodies. The RMR engineering rock evaluation method and the Hoek–Brown criterion reveal that quartz schist has a bulk weight of 26.0 kN/m3, a cohesion of 530 kPa, and an internal friction angle of 15.0°. The iron ore body has a bulk weight of 38 kN/m3, a cohesion of 1020 kPa, and an internal friction angle of 29°.

-

3.

An effective Morgenstern–Price-based algorithm in conjunction with pseudo-static seismic and blast loadings is employed to assess the mine slope stability in the presence of various loading conditions. Then, the effectiveness of the proposed approach in rational predicting the factor of safety of various slope structures under the self-weight, groundwater, and seismic loads was proved by comparing its obtained results with those predicted by Geo-Slope software.

-

4.

The proposed algorithm approach is also utilized to evaluate the mine slope stability in the presence of three loading conditions (i.e., self-weight + groundwater, slope self-weight + groundwater + blasting vibration force, and self-weight + groundwater + seismic force). The factor of safety values of the slopes pertinent to Slope#1/Slope#2/Slope#3 subjected to the above loading conditions are obtained as 1.354/1.273/1.188, 1.326/1.239/1.169, and 1.321/1.232/1.162, respectively. Further scrutiny and a comparison with those recommended by “Technical Specification of Non-Coal Open-Pit Mining Slope Engineering Technology39” indicate that all considered slope stopes meet the specification requirements.

Data availability

Data are contained within the article.

References

Ning, Y., Tang, H., Wang, F. & Zhang, G. Sensitivity analysis of toppling deformation for interbedded anti-inclined rock slopes based on the Grey relation method. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 78, 6017–6032. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10064-019-01505-2 (2019).

Ambrosi, C. & Crosta, G. B. Valley shape influence on deformation mechanisms of rock slopes. Geol. Soc. Lond. Special Publ.. 351(1), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1144/SP351.12 (2011).

Vatanpour, N., Ghafoori, M. & Talouki, H. H. Probabilistic and sensitivity analyses of effective geotechnical parameters on rock slope stability: A case study of an urban area in northeast Iran. Nat. Hazards. 71, 1659–1678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-013-0982-6 (2014).

Cundall, P. A. & Damjanac, B. V. Considerations on slope stability in a jointed rock mass. In ARMA US Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium ARMA-2016. (ARMA, 2016).

Malkawi, A. I., Hassan, W. F. & Abdulla, F. A. Uncertainty and reliability analysis applied to slope stability. Struct. Saf. 22(2), 161–187 (2000).

Mr. Digvijay, P., Salunkhe, A. P. G. C., Rupa, N. & Bartakke, P. R. K. An overview on methods for slope stability analysis. Int. J. Eng. Res. Technol. (IJERT) 6(3) (2017).

Kolapo, P. et al. An overview of slope failure in mining operations. Mining 2(2), 350–384 (2022).

Nalgire, T. et al. Slope stability analysis by geoslope. Helix 10(1), 71–75 (2020).

Wang, J., Yu, Q., Wang, G. & Tong, D. Stability analysis of cemented tailings backfill in stope considering layered structural characteristics. Minerals 13(9) (2023).

Hu, B., Wang, X., Li, S., Zhao, J. & Eugénie, N. M. Stability analysis and confidence level evaluation of backfill mining under high and steep rock slopes. Adv. Civil Eng. 2018, 1–12 (2018).

Oo, C. T. et al. Design and stope stability analysis of multiple concurrent excavated veins in underground mine; case study of Hermyingyi Tin-Tungsten (W-Sn) Mine. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 41(2), 1049–1072 (2022).

Zhang, R., Wu, S., Xie, C. & Chen, Q. Risk monitoring level of stope slopes and landslides in high-altitude and cold mines. Sustainability 14(13) (2022).

Ren, S. et al. Stability analysis of open-pit gold mine slopes and optimization of mining scheme in Inner Mongolia, China. J. Mt. Sci. 17(12), 2997–3011 (2020).

Jahanbakhshzadeh, A., Aubertin, M. & Li, L. A new analytical solution for the stress state in inclined backfilled mine stopes. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 35(3), 1151–1167 (2017).

Jaiswal, A. V. A. & Singh, T. N. A novel proposed classification system for rock slope stability assessment.

Kundu, J. S. K., Verma, A. K. & Singh, T. N. Novel methods for quantitative analysis of kinematic stability and slope mass rating in jointed rock slopes with the aid of a new computer application.

Ansari, T. K. A., Singh, K. H., Singh, T. N. & Sazid, M. Geotechnical and micro-structural characteristics of phyllite derived soil; Implications for slope stability, Lesser Himalaya, Uttarakhand, India.

Ansari, T. A. S. V., Singh, T. N. & Das, A. Slope instability analysis in Phyllitic rock in the lesser himalayan using three different modeling approaches.

Nkanyane, F. et al. The effects of strata orientation and water presence on the stability of engineered slopes using DIPS and FLACSlope: A case study of Tubatse and Fetakgomo engineered road slopes. Appl. Sci. 14(21), 9838 (2024).

Mao, Y., Chen, L., Nanehkaran, Y. A., Azarafza, M. & Derakhshani, R. Fuzzy-based intelligent model for rapid rock slope stability analysis using qslope. Water 15(16) (2023).

Agbelele, K. J., Adeoti, G. O., Agossou, D. Y. & Aïsse, G. G. Study of slope stability using the Bishop Slice method: An approach combining analytical and numerical analyses. Open. J. Appl. Sci. 13(08), 1446–1456 (2023).

Rao, B. et al. Comparative Analysis of 2D and 3D Slope Stability Problems Using Limit Equilibrium technique-based Bishop’s Simplified Method (Multiscale and Multidisciplinary Modeling, Experiments and Design, 2023).

Igwe, O. & Chukwu, C. Slope stability analysis of mine waste dumps at a mine site in Southeastern Nigeria. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 78(4), 2503–2517 (2018).

Bissaya, R., Medjo, R. E., Njom, B. & Ghogomu, R. T. A case study on the stability analysis and rockfall assessment on a massif at risk, Mbankolo, Cameroon. Arab. J. Geosci. 15(18) (2022).

Kenmoe, O. R. M., Chebou, G. N., Chamgoué, A. C., Ewang, K. M. & Mambou, L. L. N. Stability analysis of the cut slopes in the locality of Limbe using numerical modeling (South-West Cameroon). Arab. J. Geosci. 16(9) (2023).

Epada, P. D., Sylvestre, G. & Tabod, T. C. Geophysical and geotechnical investigations of a landslide in Kekem Area, Western Cameroon. Int. J. Geosci. 03(04), 780–789 (2012).

Ji, J., Zhang, W., Zhang, F., Gao, Y. & Lü, Q. Reliability analysis on permanent displacement of earth slopes using the simplified Bishop method. Comput. Geotech. ;117. (2020).

Cheng, Y. M. & Lau, C. Slope Stability Analysis and Stabilization: New Methods and Insight (CRC, 2008).

Zheng, H., Liu, D. F. & Li, C. G. Slope stability analysis based on elasto-plastic finite element method. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 64(14), 1871–1888 (2005).

Jiang, J. et al. An Evaluation Method of open-pit Slope Stability Based on Poset Theory10 (Geomechanics and Geophysics for Geo-Energy and Geo-Resources, 2024).

Yu, L. & Xu, X. Application of intelligent optimization algorithm in slope engineering stability. Green Energy Environm. Sustain. Dev. (2023).

Saim, N. M. & Kasa, A. Comparative analysis of slope stability using finite element method (FEM) and limit equilibrium method (LEM). Paper presented at: 2023 IEEE 14th Control and System Graduate Research Colloquium (ICSGRC) 5–5 (2023).

Li, M., Li, K., Qin, Q. & Yue, R. Slope stability prediction based on IPOARF algorithm: A case study of Lala Copper Mine, Sichuan, China. Expert Syst. Appl. 229, 120595 (2023).

Meko, L., Chemeda, Y. C. & Meko, B. Road cut slope stability analysis for static and dynamic (pseudo-static analysis) loading conditions. Open. Geosci. 15(1) (2023).

Kumar, S. C. S., Burman, A., Singh, R. K., Bardhan, A. & Asteris, P. G. Probabilistic Slope Stability Analysis of Mount St.

Kumar, S. C. S. & Burman, A. Recent advances in 3d slope stability analysis: a detailed review. Model. Earth Syst. Environ.

GB, T.23561.1. Methods for Determining the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Coal and Rock-Part 1: General Requirements for Sampling. (Standards press of China, 2009). (In Chinese).

GB/T 50266-2013. Standard for Test Methods of Engineering Rock Mass. (Mohurd, 2013). (In Chinese).

GB/T 51016-2014. Technical Specification for Slope Engineering of Non-Coal Surface Mines. Beijing, China (2014). (In Chinese).

Morgenstern, N. R. & Price, V. E. The analysis of the stability of general slip surfaces. Géotechnique 15(1), 79–93 (1965).

Morgenstern, N. R. & Price, V. E. A numerical method for solving the equations of stability of general slip surfaces. Comput. J. 9, 388–393 (1967).

GB18306. China Earthquake Administration: Seismic Ground Motion Parameter Zonation Map of China. (China Standards Press, 2001).

Hynes-Griffin, M. E. & Franklin, A. G. Rationalizing the seismic coefficient method. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Waterways Experiment Station, Vicksburg, Mississippi, 1984, Miscellaneous Paper GL-84-13, 21.

Corps of Engineers & Washington. Slope Stability Manual EM-1110-2-1902 (Department of the Army, Office of the Chief of Engineers, 1982).

Marcuson, W. F. & Franklin, A. G. Seismic design, analysis, and remedial measures to improve the stability of existing earth dams-corps of engineers approach. In Seismic Design of Embankments and Caverns (ed. Howard, T. R.) (ASCE, 1983).

GB/T50218-2014. Standard for Engineering Classification of Rock Masses (China Planning, 2014). (In Chinese).

Cheng, Z., Ding, J., Rao, X., Cheng, Y. & Xu, H. Physical model tests of expansive soil slope. In Geo-Congress 2013: Stability and Performance of Slopes and Embankments III 2013, 731–740.

Alejano, L. R., Ferrero, A. M., Ramírez-Oyanguren, P. & Fernández, M. Á. Comparison of limit-equilibrium, numerical and physical models of wall slope stability. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 48(1), 16–26 (2011).

Huang, W. Stability of unsaturated soil slopes under rainfall and seismic loading, Doctoral dissertation, Nanyang University of Technology (2018).

Chen, Y. L. et al. Stability evaluation of slope subjected to seismic effect combined with consequent rainfall. Eng. Geol. 266, 105461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2019.105461 (2020).

Chen, C. Y., Chen, H. W. & Wu, W. C. Numerical modeling of interactions of rainfall and earthquakes on slope stability analysis. Environ. Earth Sci. 80(16), 524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-021-09855-5 (2021).

Layek, S., Villuri, V. G., Koner, R. & Chand, K. Rainfall & seismological dump slope stability analysis on active mine waste dump slope with UAV. Adv. Civil Eng. 2022(1), 5858400. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/5858400 (2022).

Shukla, S. K. & Hossain, M. M. Stability analysis of multi-directional anchored rock slope subjected to surcharge and seismic loads. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 31(5–6), 841–844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soildyn.2011.01.008 (2011).

Shukla, S. K., Khandelwal, S., Verma, V. N. & Sivakugan, N. Effect of surcharge on the stability of anchored rock slope with water filled tension crack under seismic loading condition. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 27, 529–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10706-009-9254-3 (2009).

Zheng, W., Zhuang, X. & Cai, Y. On the seismic stability analysis of reinforced rock slope and optimization of prestressed cables. Front. Struct. Civil Eng. 6, 132–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11709-012-0152-z (2012).

He, S., Ouyang, C. & Luo, Y. Seismic stability analysis of soil nail reinforced slope using kinematic approach of limit analysis. Environ. Earth Sci. 66, 319–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-011-1241-3 (2012).

Liu, B.K., Lu, W.Z.: Surrogate models in machine learning for computational stochastic multi-scale modelling in composite materials design, Int. J. Hydromechatronics 5(4), 336–365 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHM.2022.127037.

Nanehkaran, Y. A. et al. Comparative analysis for slope stability by using machine learning methods. Appl. Sci. 13(3), 1555 (2023).

Li, Y., He, X., Zhou, C.: Automatic modulation recognition based on a new deep K-SVD denoising algorithm. J. Data Sci. Intell. Syst. https://doi.org/10.47852/bonviewJDSIS32021244. (2023).

Wang, H., Sun, W., Sun, W., Ren, Y., Zhou, Y., Qian, Q. and Kumar, A.: A novel tool condition monitoring based on Gramian angular field and comparative learning. Int. J. Hydromechatronics 6(2), 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHM.2023.130510. (2023).

Mahmoodzadeh, A. et al. Prediction of safety factors for slope stability: Comparison of machine learning techniques. Nat. Hazards. 1, 1–29 (2022).

Wan, S., Guan, S., Tang, Y.: Advancing bridge structural health monitoring: insights into knowledge-driven and data-driven approaches. J. Data Sci. Intell. Syst. https://doi.org/10.47852/bonviewJDSIS3202964. (2023).

Gaur, H., Khidhir, B., Manchiryal, R.K.: Solution of structural mechanic’s problems by machine learning. Int. J. Hydromechatronics, 5(1) 22–43 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1504/IJHM.2022.122459.

Lin, S., Zheng, H., Han, C., Han, B. & Li, W. Evaluation and prediction of slope stability using machine learning approaches. Front. Struct. Civil Eng. 15(4), 821–833 (2021).

Tanimu, J., Shiaeles, S. & Adda, M. A comparative analysis of feature eliminator methods to improve machine learning phishing detection. J. Data Sci. Intell. Syst. https://doi.org/10.47852/bonviewJDSIS32021736 (2023).

Zhang, L. A generalized three-dimensional Hoek–Brown strength criterion. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 41, 893–915 (2008).

Priest, S. D. Determination of shear strength and three-dimensional yield strength for the Hoek–Brown criterion. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 38, 299–327 (2005).

Shen, J., Priest, S. D. & Karakus, M. Determination of Mohr–Coulomb shear strength parameters from generalized hoek–brown criterion for slope stability analysis. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 45, 123–129 (2012).

Ma, L. J. et al. A new elasto-viscoplastic damage model combined with the generalized Hoek–Brown failure criterion for bedded rock salt and its application. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 46, 53–66 (2013).

Zhang, Q., Zhu, H. & Zhang, L. Modification of a generalized three-dimensional Hoek–Brown strength criterion. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 59, 80–96 (2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y.; methodology, X.D. and Z.S.; validation, Z.Y. and A.M.A.W.; formal analysis, M.N.M.V.; investigation, X.D.; resources, B.O.; data curation, F.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Y. and A.Y.I.; writing—review and editing, Z.G. and Z.L.; visualization, Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Z., Song, Z., Ding, X. et al. Investigating slope stability of multiple stopes prone to instability in the Ziluoyi iron ore mining site. Sci Rep 15, 1900 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85770-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85770-0

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Damage quantification and response surface prediction of blasting-induced slope stability based on DFN

Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment (2026)

-

Correlation analysis and comprehensive evaluation of dam safety monitoring at Silin hydropower station

Scientific Reports (2025)