Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive disorder that affects the nervous system and causes regions of the brain to deteriorate. In this study, we investigated the effects of MR-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) for the delivery of human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) on the 6-hydroxydopamine (6-HODA)-induced PD rat model. MRgFUS-induced blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability modulation was conducted using an acoustic controller with the targets at the striatum (ST) and SN. Human MSCs were injected immediately before sonication. Here, we show that we can deliver human MSCs into Parkinsonian rats through MRgFUS-induced BBB modulation using an acoustic controller. Stem cells were identified in the sonicated brain regions using surface markers, indicating the feasibility of MSC delivery via MRgFUS. MSCs + FUS treatment significantly improved the behavioural outcomes compared with control, FUS alone, and MSCs alone groups (p < 0.05). In the quantification analysis of the TH stain, a significant reservation of dopamine neurons was seen in the MSCs + FUS group as compared with the MSCs group (ST: p = 0.03; SN: p = 0.0005). Mesenchymal stem cell therapy may be a viable treatment option for neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s. Transcranial MRgFUS serves as an efficacious and safe method for targeted and minimally invasive stem cell homing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative movement disorder characterized by relatively focal degeneration of mesencephalic dopamine (mesDA) neurons, the cell bodies of which are located within the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) in the midbrain1. The associated deprivation of axonal projections and subsequently reduced release of dopamine (DA) onto the striatal medium spiny neurons leads to the cardinal symptoms, such as bradykinesia, resting tremor, and muscular rigidity. As such, DA replacement therapy has been established and is now a gold standard for PD treatment2. Pharmaceutical strategies such as this are advantageous because they are non-invasive, and oral administration is fast acting. However, traditional medicine can only improve symptoms temporarily, as it cannot halt disease progression and can cause treatment-related motor fluctuations and dyskinesias for a while. On the other hand, surgical interventions, such as deep brain stimulation (DBS) and thermocoagulation, have also been developed as an alternative therapeutic option for PD3,4. Surgery has immediate and dramatic effects; however, it is invasive, and there is a risk of intracranial hemorrhage, facial palsy, dysarthria and paresthesia for surgical treatments5. Hence, there is an imperative need to develop innovative therapeutic strategies that can overcome the drawbacks of present treatments, to detain the progression of the disease and improve patients’ quality of life.

While MSCs are larger than the average BBB gap, focused ultrasound (FUS) does not strictly open the BBB to allow free passage based on molecular size alone. FUS modulates the BBB, creating a transient increase in permeability that induces changes in endothelial cell properties, upregulating adhesion molecules and increasing local cytokine release, which could aid in active cell transmigration. A study by Burgess et al.6 demonstrated that MRIgFUS, in combination with microbubbles, can allow even larger entities, such as neural stem cells, to traverse the BBB—further, Shen et al.7 suggested that the physical effects of FUS are accompanied by a biological response that enhances cell transmigration through interaction with the vascular endothelium. In this study, the MRIgFUS treatment likely involves a combination of physical opening, modulation of endothelial cells, and biochemical signalling that allow MSCs to cross the BBB.

Since the primary motor symptoms of PD are associated with DA neuronal loss, it implies that cell substituting within the specific brain area offers hope for ameliorating some of the significant neurological deficits of PD patients. Therefore, there has been a long-standing interest in cell-replacement therapy in treating PD. A more profound comprehension of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) function is needed for cell-replacement therapy of neurodegenerative disorders and the evolution of potent cell-derived treatments in regenerative medicine8. MSCs induce a range of biological effects, including neuroprotective, immunomodulatory, angiogenic, and chemotactic effects, and promote differentiation of the resident stem cells. MSCs have shown noteworthy therapeutic power in Parkinsonian animals9. Clinical trials also support the efficacy and safety of MSCs in PD10. Even though MSCs promise great therapeutic potential, there are challenges in their application to the central nervous system (CNS), particularly regarding the delivery efficacy associated with transplantation technologies.

Intracerebral transplantation is the most widely utilized procedure for delivering cells into the brain. The outcome has yet to be satisfied because only part of the patients responded well to this treatment11,12,13. However, there are various risks related to this procedure, such as surgical complications (hemorrhage and wound infection), tissue damage inducing inflammatory edema, and transplantation immune responses14,15. Intranasal delivery has been proffered to avoid these surgical risks but has been shown to be inaccurate and requires cell migration to the target brain areas16.

Magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound (MRIgFUS), which is applied transcranially to a specific brain area and combined with a systemically administered microbubble (MB) contrast agent, has been utilized to transiently increase the permeability of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), allowing neural stem cells (NSCs)17 and MSCs18 to cross from the bloodstream into the brain in healthy rats. The morphological changes observed in the brain vasculature of PD patients—such as alterations in capillary numbers, length, and diameter—highlight the need for new approaches that specifically target these changes. Hence, the current study explores MRIgFUS-enhanced intracranial transplantation of MSCs to determine whether this method could address these vascular alterations and enhance MSCs delivery in the PD model19. In the present study, we aimed to assess the therapeutic efficacy of targeted delivery of human bone marrow MSCs (hBM-MSCs) using MRIgFUS in the 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) PD model, when compared to intravenous hBM-MSCs administration, by evaluating behaviour performance as well as histological changes of SN and striatum.

Results

The experiments were designed to evaluate the efficacy of MRgFUS for delivering MSCs into specific brain regions (striatum and substantia nigra) in the 6-OHDA-induced Parkinson’s disease rat model. MSCs were delivered following BBB modulation using focused ultrasound, and behavioural outcomes were monitored to assess therapeutic efficacy. The MRgFUS parameters used in these experiments were peak-negative pressure at 0.128 MPa, pulse length of 10 ms, and pulse repetition frequency of 1 Hz. Microbubbles (20 µL/kg of Definity) were administered to aid BBB permeability.

MRgFUS-facilitated BBB permeability modulation

The goal of this experiment was to evaluate the efficacy of MRgFUS in enhancing BBB permeability in targeted brain regions, which is a critical step for subsequent MSC delivery in the Parkinson’s disease rat model. A schematic of the MRgFUS setup is depicted in Fig. 1. In brief, T2-weighted MR images were taken to precisely target the regions in the ST and SN in the lesioned hemisphere of the PD rats. 10 bursts at 0.128 MPa without microbubbles were used to capture the baseline emissions, followed by an intravenous injection of microbubbles. Upon detection of the acoustic threshold, the MSCs were injected immediately via the tail vein. The representative BBB permeability enhancement is shown in Fig. 2A, indicating that the enhancement was achieved in both the ST and SN. In addition, post-treatment T2* images (Fig. 2B) demonstrated no detectable hypo-intense signal in the targeted regions, which indicated no acute hemorrhage occurred due to the FUS sonication. Figure 2C shows the BBB permeability enhancement threshold for the ST (0.42 ± 0.10 MPa) and the SN (0.4 ± 0.09 MPa). No significant difference in the threshold was found between these two regions (p = 0.6).

Representative blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability modulation in Parkinson’s disease rats after Magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound. (A) T1-weighted images post-treatment demonstrated the BBB permeability enhancement in the striatum (ST) and substantia nigra (SN) in both coronal and sagittal views, compared to pre-treatment. (B) No obvious hypo-intense signal was found in the sonicated regions in the post-sonication T2* images. (C) The BBB permeability enhancement thresholds in ST and SN using the acoustic controller.

Mesenchymal stem cells are identified in the brain after FUS

This experiment aimed to determine whether the MRgFUS protocol could successfully facilitate the translocation of MSCs across the BBB into the brain parenchyma in the Parkinson’s disease rat model. To identify whether microbubble-mediated FUS exposure is able to translocate MSCs to the brain parenchyma, animals (n = 4) were sacrificed 2 h post-treatment. Two MSC surface markers, CD90 (Fig. 3A) and CD105 (Fig. 3B), were used to identify the MSCs in vivo and the Prussian blue stain (Fig. 3C) was able to pick out the iron-labelled MSCs in the sonicated region. In contrast, no stained or labeled cells were found on the contralateral side of the brain at this time point, indicating that MRgFUS could translocate the MSCs into the desired part of the brain.

Effects of FUS-induced MSCs transplantation on 6-OHDA-induced motor deficits

This experiment aimed to evaluate the therapeutic effects of MRgFUS-enhanced MSC transplantation on motor deficits in the 6-OHDA-induced Parkinson’s disease rat model. To determine whether dopaminergic neuroprotective effects could be achieved by transplantation of MSCs by FUS sonication in the 6-OHDA-induced Parkinsonian rat model, 4 different treatment groups were compared. Treatment efficacy was assessed using 2 motor function-related behavioural tests before treatment as the baseline and four weeks after the MSCs delivery as the endpoint. The percentage of left paw usage was measured in the cylinder test at the baseline and endpoint. The ratio of behavioural performance compared to the baseline measurement is shown in Fig. 4. MSCs + FUS treatment showed a significant improvement in left paw usage as compared with the control (p = 0.003) and the MSCs alone treatment (p = 0.03). In addition, the progression in apomorphine-induced rotations (AIR) was less in the MSCs + FUS condition as compared with the control (p = 0.002) and the MSCs alone (p = 0.02), indicating that the MSCs + FUS treatment had demonstrated neurorestorative effects on these PD-related behavioural outcomes.

The behavioural data were collected to compare pre-treatment and the endpoint. MSCs + FUS treatment significantly improves the outcome in the cylinder and apomorphine-induced rotation tests. (A) MSCs + FUS elicited a significant improvement in the cylinder test compared to control and MSCs treatments. (B) MSCs + FUS showed a less progressive rotation response as compared to MSCs and control.

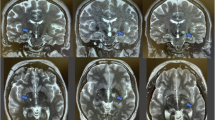

Histological characterization of dopaminergic neurons and quantification of TH stain

This experiment aimed to investigate the effects of MRgFUS-facilitated MSC transplantation on the integrity of dopaminergic neurons in the striatum and substantia nigra by quantifying tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) expression. In the nigrostriatal pathway, the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) in the midbrain projects to the striatum (ST) (caudate nucleus and putamen). Therefore, the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in this 6-OHDA-induced PD model produces dopamine neuron depletion in both the ST and SN, which can be characterized by the tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) stain. To verify the efficacy of FUS-facilitated MSCs transplantation in promoting neuron function, we calculated the ST and SN neuron fibre density by quantifying their TH immunoreactivity on the lesioned site and employed the contralateral regions as the control for each animal. Figure 5 shows the representative TH stain for 4 different conditions in the ST and SN. In the control and FUS alone treatment, the ST and SN on the lesioned hemisphere demonstrate a significant loss of TH-positive neurons. MSCs alone achieved a slight improvement in the number of ST and SN TH-positive neurons. Moreover, MSCs + FUS showed a restorative effect on the lesioned side. The quantitative data of the TH stain is plotted in Fig. 6. The results are shown as the relative ratio by dividing the contralateral side into the ipsilateral side. MSCs + FUS treatment (ST: 33 ± 6%; SN: 40 ± 3%) significantly increased the TH expression as compared to MSCs (ST: 28 ± 2%; SN: 32 ± 5%) in both the ST (p = 0.03) and SN (p = 0.0005).

Discussion

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have drawn much attention due to their remarkable immuno-modulatory, neurotrophic, and neurogenic properties20,21. Here we show how MSCs, in combination with FUS, can be a tool to provide the neuroprotective effects on the 6-OHDA-induced Parkinsonian rat model. By using an ST-SN sonicating pattern to the nigrostriatal pathway, we were able to achieve MSCs transcranial delivery and thus improve pathological and behavioural traits of PD. The treatment was well-tolerated by the animals, without evidence of abnormal behaviour. In addition, no treatment-induced tissue damage was found in histology and MRI observation.

Human bone marrow-derived MSCs have shown therapeutic potential for the development of regenerative treatments in PD, and systemic administration of these cells has been tested in preclinical and clinical studies22,23. In PD models, MSCs exhibit immunomodulatory effects after infiltrating injury sites in response to particular chemotactic recruitment24 and releasing several growth and immunoregulatory factors; therefore, MSCs can alleviate inflammation and improve tissue healing25. Moreover, MSC-based therapy has been used to modulate inflammation and accommodate tissue regeneration in treating PD and many other neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative illnesses26. In these studies, different routes of administration were examined. In one study, Venkataramana et al.22 demonstrated the stereotaxic injection of MSCs into the lateral ventricles; in the other studies, the systemic (intra-arterial or intravenous) routes were chosen27,28,29. These studies suggested that systemic administration of MSCs is safe and effective in delaying the progression of neurological deficits. However, the efficiency of MSC homing within the brain remains unclear.

Extravasation of infused stem cells to injured sites occurs in a similar way with endogenous immune cells (dendritic cells, T-cells, monocytes), in that stem cells also follow the steps of chemoattraction, margination, rolling, adhesion, and diapedesis, which is a consequence of similar expression profiles of integrins, cytokine and chemokine receptors (e.g., VCAM-1, beta1 integrins)30,31. In the CNS, many preclinical studies have shown that pretreatment with focused ultrasound (FUS) in the presence of preformed microbubbles non-destructively modifies the vascular endothelial microenvironment, demonstrated by an up-regulation of chemokines, cytokines, cell adhesion molecules (CAM) and trophic factors (CCTFs)32,33,34. This pattern of FUS-mediated biological alterations allows significant enhancement of stem cell homing and transmigration compared with simple intra-vascular injection35.

FUS, in combination with microbubbles, can elicit a wide range of bioeffects in the brain. Therefore, monitoring and controlling the exposure level is necessary to achieve consistent, reversible BBB permeability enhancement. Various feedback control algorithms have been employed to induce transient enhancement in BBB permeability, while avoiding overexposure of the brain36,37,38,39. In this study, we used a modified version of the controller using the sub-harmonics or ultra-harmonics to determine the operating pressure, as O’Reilly et al. reported40. In addition, there was no damage in the post-treatment T2* images, indicating that the sonication was tolerated by the animals.

The results presented here build upon several previous reports. It was previously shown that neural stem cells are capable of differentiating into a neuronal lineage in vivo at 24 h6. In this study, a shorter time point (2 h) was able to detect the cell deposition within the brain parenchyma. Poon et al. showed that MBs + FUS mediated BBB modulation allowed immune cells to translocate in the brain parenchyma immediately after sonication in vivo41. Shen et al. delivered human neural progenitor cells (hNPCs) via FUS-mediated BBB permeability modulation, and they were able to identify the Molday iron oxide nanoparticles (MIONs) two hours post-FUS sonication7, which is similar to what we observed in this study.

Intracarotid (IA) infusion of MSCs to a similar PD rat model has been conducted, and transient BBB disruption by mannitol was found necessary to achieve the delivery to the brain23. Without mannitol-induced BBB disruption, MSCs do not efficiently cross the BBB in PD rats. The FUS-induced delivery of MSCs can be compared to the IA mannitol infusion method. Mannitol infusion-induced BBB opening leads to the global distribution of MSCs within the brain, whereas FUS provides a localized cell accumulation. The disadvantage of mannitol-induced BBB disruption is that it may result in increased BBB permeability in off-target brain areas, which would, for instance, permit higher exposure to endogenous neurotoxins (i.e., albumin) and may lead to adverse impacts such as vaso-vagal responses and focal seizures42. Future work on combining the IA injection of MSCs and FUS sonication might have the potential to increase the number of therapeutic cells in the desired region.

The current study has several limitations which should be addressed in future work. Firstly, the number of MSCs was given based on the literature values6, which used 2 million cells via intravenous injection. Lee et al.32. intravenously injected 3 million of MSCs in combination with FUS and resulted in a more than 2 folds increment in MSCs delivery. This indicates a higher amount of stem cells can be further examined on the therapeutic efficacy.

Secondly, using the cell transplantation method in an animal model requires an immunosuppressant for the whole session of treatment, which is somehow not representative of the clinical context. The long-term use of immunosuppressants can cause several side effects43. This limitation can be conquered by using individual patients’ grafting products, which would require further investigation to demonstrate safety, and would increase treatment cost44. Furthermore, although the MSCs can be maintained in cell culture for some time, we only used the cells within six passages due to the design of the experiment. It might be useful to conduct a repeated or fractional treatment using the same patch of cells to examine the therapeutic outcome over a longer treatment duration.

Finally, although the FUS-facilitated MSCs transplantation provides a significant improvement in the TH stain, the behavioural outcome is not yet optimal. For instance, the sonicated region could be extended to cover the entire nigrostriatal pathways. In our setup, the MSCs were infused upon the detection of sub- or ultra-harmonic signals; a more robust volume of BBB permeability enhancement can be achieved by a phased-array system45. There are several documented ways that the number MSCs could be increased in the brain: Firstly, the microbubble dose could be increased46. Secondly, the sonications could be repeated47,48. Thirdly, intra-arterial infusion of cells23,27 increases the available cells and thus increases the delivery. However, the optimal number of MSCs in the brain for the treatment of any brain condition has not been studied with FUS and should be investigated in the future.

In conclusion, our results provide proof-of-concept validation as well as the efficacy and safety of using MRgFUS for enhancing cellular delivery. The characteristic non-invasiveness and repeatability of MRgFUS-mediated delivery show the great potential of treatment paradigms for neurodegenerative disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease, especially for patients who are poor surgical candidates. The encouraging results offer motivation for further application and assess its feasibility for clinical translation.

Methods

Animals

A total of thirty-two male Wistar rats (Taconic Biosciences, USA) that had a mean weight of 301 ± 11 g were used in this study. All animal procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee at Sunnybrook Research Institute and are in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care and ARRIVE guidelines. Animals were housed in the Sunnybrook Research Institute animal facility (Toronto, Canada) on a reverse light cycle and were allowed water and food ad libitum. All the rats were immunosuppressed with 12.5 mg/kg cyclosporine A (PHR1092, Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) via daily subcutaneous injection starting the day before the treatment and continuing up to the day they were sacrificed.

PD model by intracranial injection of 6-OHDA to Substantia Nigra pars Compacta (SNc)

Animals were anesthetized initially with 5% isoflurane in the chamber and then reduced to 2.5% for the duration of the surgery with a mask. The procedure was performed on a stereotaxic apparatus (Model 940, Kopf, CA, USA). After hair removal from the scalp, an incision was made, and then a burr hole was carefully drilled based on the coordinates of substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc). A total of 2 µL 6-OHDA (5 mg/ml of 6-OHDA dissolved in saline containing 0.01% ascorbic acid, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was administered in the right SNpc with a Hamilton syringe (26-gauge, model 80030, NV, USA) at a flow rate of 0.4 µl/min. Coordinates from bregma were: AP = -5.3 mm, ML = + 2.0 mm, DV = -7.8 mm49. The syringe was left in place for 5 min after injection and then removed slowly50. The skin incision was then closed with 5–0 polydioxanone sutures. Pain relief medication (buprenorphine, 0.05 mg/kg) was given subcutaneously once daily for 3 days after surgery.

Behavioural evaluation – cylinder test and apomorphine-induced rotations (AIR)

The baseline behavioural evaluation was conducted to verify the success of this PD model on day 13 after surgery. In this study, we used the cylinder test and apomorphine-induced rotations to evaluate the animal mobility related to PD. In the cylinder test, the animals were placed in an approximately 20-cm-diameter cylinder, and a camera was placed on top of the cylinder to record the animal for 5 min. There was a minimum of 25 contacts to the wall of the forelimbs. For the apomorphine-induced rotation (AIR) test, the animals were evaluated with a subcutaneous injection of apomorphine (0.4 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). 10 min after injection, the rats were placed in an open field environment, and the complete turns contralateral to the lesion side were recorded quantitatively for a session duration of 10 min. The net asymmetry rotation score was expressed as the complete body turns per minute. Only animals with positive responses (a total of more than 30 rotations) would be selected for the following transplantation experiments51,52. The endpoint assessment of the two behavioural tests was conducted on day 41 before sacrificing the animals (Fig. 7).

Summary of experimental workflow. The injection of 6-OHDA was referred to as Day 0. The baseline and endpoint behavioural tests were performed on Day 13 and 41, respectively. The MSCs transplantation treatment using MRgFUS was conducted on Day 14. The endpoint of the study was six weeks after the 6-OHDA-induced PD surgery.

Cell culture

Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hBM-MSCs) (SC00BM1, Vitro Biopharma, Colorado, CO, USA) were cultured in low serum, complete medium (Vitro Biopharma, SC00B1) in 75 cm2 cell culture flasks in a 5% CO2-containing incubator at 37 °C. Cell number and viability were calculated with a Luna automated cell counter (Logos Biosystems, Inc., Gyeonggi-do, South Korea) via trypan blue exclusion. The medium was replaced twice a week until confluence, and the hBM-MSCs were used within six passages.

For the iron oxide labelled MSCs detection, 4 µL of superparamagnetic iron oxide (Fe3O4, No. 725358-5ML, Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the stem cell media 24 h prior to the transplantation experiments, as previously described17. For the in vivo injection, hBM-MSCs (both iron-labelled and non-iron-labelled) were treated with Accutase cell detachment solution (ZenBio Inc., Durham, NC, USA), collected, centrifuged, and re-suspended at a concentration of 4 × 106 cells/mL in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were maintained at 4 °C before the injection, for a maximum of 2 h.

Stem cell transplantation therapy via MRgFUS

Prior to sonication, the rats were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane inhalation with medical air as the gas carrier. The hair on the top of their head was removed with clippers and depilatory lotion. The rats were then placed supine on an MR-compatible sled, and their head was coupled to a tank of degassed water with ultrasound gel. FUS treatment was conducted using a pre-clinical MRI-guided system (an in-house developed prototype of LP100, FUS Instrument Inc., Toronto, ON, Canada), which utilizes an in-house manufactured, spherically focused transducer (f0 = 580 kHz, focal number = 0.8, diameter = 75 mm). Pressure calibration of the transmit transducer was characterized using a planar fibre optic hydrophone (diameter = 10 μm, Precision Acoustic Ltd., Dorset, UK). MRI spatial coordinates were co-registered to the transducer motorized positioning system within a tank of degassed and deionized water to allow targets to be chosen from MR images with a 3-axis freedom. Ultrasound was delivered in 10 ms bursts with a pulse repetition frequency of 1 Hz, and the acoustic emission signals were captured using an in-house manufactured lead zirconate titanate (PZT) hydrophone, which has peak sensitivity at 870 kHz ± 5 kHz, stored on a scope card (ATS460, AlazarTech, Pointe-Claire, Quebec, Canada). The threshold for microbubble activation was defined as the pressure required for ultra-harmonic emissions to exceed the mean plus 10 standard deviations of the baseline ultra-harmonic (870 kHz) signal. A pressure ramp was used to detect the onset of ultra-harmonic signal, starting at a peak negative pressure of 0.128 MPa, where 10 s of baseline measurements were recorded prior to a bolus of microbubbles injection (20 µL/kg of Definity; Lantheus Medical Imaging, Massachusetts, USA). After injection, ultrasound pressure was increased by 0.008 MPa each second until the threshold was achieved, and then the pressure was fixed for the remainder of the 120 s sonication40. Meanwhile, MSCs, suspended in 0.5 mL of PBS as described above, were injected into the tail vein, followed by 0.25 mL of saline flush. T2-weighted images (4000 ms TR, 70 ms TE, 256 × 256 image matrix, 1.5 mm slice thickness) were acquired using a 7-Telsa MRI scanner (BioSpin 7030; Bruker, Billerica, Massachusetts, USA) to select regions on the lesioned side of the brain, which included one target at the SN and two locations at the striatum. T1-weighted images (500 ms TR, 5 ms TE, 256 × 256 image matrix, 1.5 mm slice thickness) were used to confirm the BBB permeability modulation after sonication using an MRI contrast agent (0.2 mL/kg Gadovist, Schering AG, Berlin, Germany). Post-sonication T2*-weighted images (800 ms TR, 3 ms TE, 256 × 256 image matrix, 1.5 mm slice thickness) were used to identify hemorrhage.

To verify the stem cell delivery using FUS, four animals receiving iron-labelled MSCs were sacrificed via transcardiac perfusion 2 h after the treatment.

Immunohistochemistry

When brain harvesting was required, transcardiac perfusion with saline and then 10% phosphate-buffered formalin were conducted under deep anesthesia. The brain was immersed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin for histological preparation. Fixed brain tissue was embedded in paraffin wax and sectioned at 5-µm thickness. Stem cell markers CD90 (1:250; ab181469, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and CD105 (1:250; ab268052, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions. Prussian blue stain (ab150674, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) was used to confirm the iron-labelled MSCs. Tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) stain (1:500; ab112, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) was used to detect the dopaminergic neurons within the brain.

Brightfield microscopy images (Zeiss Axio Observer Z1; Carl Zeiss, Germany) of brain sections were taken. MIPAV (NIH, Bethesda, MA, USA) software was used to quantify the presence of TH with standard contour and counting functions. The images were firstly converted to grayscale in order to calculate the average intensity, and then the corresponding regions of interest in the ST and SN were contoured. The results were analyzed to compare the TH presence from the lesioned side to the contralateral side.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were processed on a computer using GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). All values are displayed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The results were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the post hoc Dunnet test. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Data availability

Data is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Henchcliffe, C. & Parmar, M. Repairing the brain: cell replacement using stem cell-based technologies. J. Parkinsons Dis. 8, S131–S137 (2018).

Sethi, K. D. The impact of levodopa on quality of life in patients with Parkinson disease. Neurologist 16, 76–83 (2010).

Benabid, A. L. et al. Deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus for Parkinson’s disease: methodologic aspects and clinical criteria. Neurology 55, S40–S44 (2000).

Vitek, J. L. et al. Randomized trial of pallidotomy versus medical therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 53, 558–569 (2003).

Bagheri-Mohammadi, S. et al. Stem cell-based therapy for Parkinson’s disease with a focus on human endometrium-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 1326–1335 (2019).

Burgess, A. et al. Targeted delivery of neural stem cells to the brain using MRI-guided focused ultrasound to disrupt the blood-brain barrier. PLoS One 6, (2011).

Shen, W. et al. Magnetic enhancement of stem cell–targeted delivery into the brain following MR-guided focused ultrasound for opening the blood–brain barrier. Cell. Transpl. 26, 1235–1246 (2017).

Spees, J. L., Lee, R. H. & Gregory, C. A. Mechanisms of mesenchymal stem/stromal cell function. Stem Cell. Res. Ther. 7, 125 (2016).

Chen, Y., Shen, J., Ke, K. & Gu, X. Clinical potential and current progress of mesenchymal stem cells for Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review. Neurol. Sci. 41, 1051–1061 (2020).

Venkataramana, N. K. et al. Open-labeled study of unilateral autologous bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in Parkinson’s disease. Transl Res. 155, 62–70 (2010).

Freed, C. R. et al. Transplantation of embryonic dopamine neurons for severe Parkinson’s disease. N Engl. J. Med. 344, 710–719 (2001).

Olanow, C. W. et al. A double-blind controlled trial of bilateral fetal nigral transplantation in Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 54, 403–414 (2003).

Barker, R. A., Barrett, J., Mason, S. L. & Björklund, A. Fetal dopaminergic transplantation trials and the future of neural grafting in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 12, 84–91 (2013).

Perry, V. H., Andersson, P. B. & Gordon, S. Macrophages and inflammation in the central nervous system. Trends Neurosci. 16, 268–273 (1993).

Sinden, J. D., Patel, S. N. & Hodges, H. Neural transplantation: problems and prospects for therapeutic application. Curr. Opin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 5, 902–908 (1992).

Danielyan, L. et al. Therapeutic efficacy of Intranasally delivered mesenchymal stem cells in a rat model of Parkinson Disease. Rejuvenation Res. 14, 3–16 (2011).

Burgess, A. et al. Targeted delivery of neural stem cells to the brain using MRI-guided focused ultrasound to disrupt the blood-brain barrier. PLoS One. 6, e27877–e27877 (2011).

Lee, J. et al. Non-invasively enhanced intracranial transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells using focused ultrasound mediated by overexpression of cell-adhesion molecules. Stem Cell. Res. 43, 101726 (2020).

Guan, J. et al. Vascular degeneration in Parkinson’s Disease. Brain Pathol. 23, 154 (2013).

Cova, L. et al. Multiple neurogenic and neurorescue effects of human mesenchymal stem cell after transplantation in an experimental model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. 1311, (2010).

Krampera, M. et al. Regenerative and immunomodulatory potential of mesenchymal stem cells. Current Opinion in Pharmacology vol. 6 Preprint at (2006). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coph.2006.02.008

Venkataramana, N. K. et al. Bilateral transplantation of allogenic adult human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells into the subventricular zone of Parkinson’s disease: a pilot clinical study. Stem Cells Int. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/931902 (2012).

Cerri, S. et al. Intracarotid infusion of mesenchymal stem cells in an animal model of Parkinson’s Disease, focusing on cell distribution and neuroprotective and behavioral effects. Stem Cells Transl Med. 4, 1073–1085 (2015).

Prockop, D. J. et al. Defining the risks of mesenchymal stromal cell therapy. Cytotherapy 12, (2010).

le Blanc, K. Mesenchymal stromal cells: tissue repair and immune modulation. Cytotherapy 8, (2006).

Glavaski-Joksimovic, A. & Bohn, M. C. Mesenchymal stem cells and neuroregeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Experimental Neurology vol. 247 Preprint at (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.03.016

Brazzini, A. et al. Intraarterial autologous implantation of adult stem cells for patients with Parkinson Disease. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 21, 443–451 (2010).

Tsai, Y. A. et al. Treatment of spinocerebellar ataxia with mesenchymal stem cells: a phase I/IIa clinical study. Cell. Transpl. 26, 503–512 (2017).

Lee, P. H. et al. A randomized trial of mesenchymal stem cells in multiple system atrophy. Ann. Neurol. 72, 32–40 (2012).

Prowse, A. B. J., Chong, F., Gray, P. P. & Munro, T. P. Stem cell integrins: implications for ex-vivo culture and cellular therapies. Stem Cell. Res. 6, 1–12 (2011).

Rüster, B. et al. Mesenchymal stem cells display coordinated rolling and adhesion behavior on endothelial cells. Blood 108, 3938–3944 (2006).

Lee, J. et al. Non-invasively enhanced intracranial transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells using focused ultrasound mediated by overexpression of cell-adhesion molecules. Stem Cell. Res. 43, (2020).

Burks, S. R. et al. Investigation of cellular and molecular responses to pulsed focused ultrasound in a mouse model. PLoS One 6, (2011).

Ahmed, N., Gandhi, D., Melhem, E. R. & Frenkel, V. MRI guided focused ultrasound-mediated delivery of therapeutic cells to the brain: a review of the state-of-the-art methodology and future applications. Front. Neurol. 12, 938 (2021).

Ziadloo, A. et al. Enhanced Homing Permeability and Retention of Bone Marrow Stromal cells by Noninvasive Pulsed focused Ultrasound. Stem Cells. 30, 1216–1227 (2012).

Çavuşoǧlu, M. et al. Closed-loop cavitation control for focused ultrasound-mediated blood-brain barrier opening by long-circulating microbubbles. Phys. Med. Biol. 64, (2019).

Arvanitis, C. D., Livingstone, M. S., Vykhodtseva, N. & McDannold, N. Controlled Ultrasound-Induced blood-brain barrier disruption using Passive Acoustic emissions Monitoring. PLoS One 7, (2012).

Bing, C. et al. Characterization of different bubble formulations for blood-brain barrier opening using a focused ultrasound system with acoustic feedback control. Sci. Rep. 8, (2018).

Sun, T. et al. Closed-loop control of targeted ultrasound drug delivery across the blood-brain/tumor barriers in a rat glioma model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 114, E10281–E10290 (2017).

O’Reilly, M. A. & Hynynen, K. Blood-brain barrier: real-time feedback-controlled focused ultrasound disruption by using an acoustic emissions-based controller. Radiology 263, 96–106 (2012).

Poon, C., Pellow, C. & Hynynen, K. Neutrophil recruitment and leukocyte response following focused ultrasound and microbubble mediated blood-brain barrier treatments. Theranostics 11, 1655–1671 (2021).

Hersh, S. Evolving drug delivery strategies to overcome the blood brain barrier. Curr. Pharm. Des. 22, 1177–1193 (2016).

Machkhas, H., Harati, Y. & SIDE EFFECTS OF IMMUNOSUPPRESSANT THERAPIES USED IN NEUROLOGY. Neurol. Clin. 16, 171–188 (1998).

Stoker, T. B., Blair, N. F. & Barker, R. A. Neural grafting for Parkinson’s disease: Challenges and prospects. Neural Regeneration Research vol. 12 Preprint at (2017). https://doi.org/10.4103/1673-5374.202935

Jones, R. M. & Hynynen, K. R. Advances in acoustic monitoring and control of focused ultrasound-mediated increases in blood-brain barrier permeability. British Journal of Radiology vol. 92 Preprint at (2019). https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20180601

Song, K. H. et al. Microbubble gas volume: a unifying dose parameter in blood-brain barrier opening by focused ultrasound. Theranostics 7, 144–152 (2017).

Nhan, T., Burgess, A., Lilge, L. & Hynynen, K. Modeling localized delivery of Doxorubicin to the brain following focused ultrasound enhanced blood-brain barrier permeability. Phys. Med. Biol. 59, 5987–6004 (2014).

Treat, L. H., McDannold, N., Zhang, Y., Vykhodtseva, N. & Hynynen, K. Improved anti-tumor effect of liposomal doxorubicin after targeted blood-brain barrier disruption by MRI-guided focused ultrasound in rat glioma. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 38, 1716 (2012).

Sindhu, K. M. et al. Rats with unilateral median forebrain bundle, but not striatal or nigral, lesions by the neurotoxins MPP + or rotenone display differential sensitivity to amphetamine and apomorphine. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 84, 321–329 (2006).

Wang, F. et al. Intravenous administration of mesenchymal stem cells exerts therapeutic effects on parkinsonian model of rats: focusing on neuroprotective effects of stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha. BMC Neurosci. 11, 52 (2010).

Hudson, J. L., Fong, C. S., Boyson, S. J. & Hoffer, B. J. Conditioned apomorphine-induced turning in 6-OHDA-lesioned rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 49, 147–154 (1994).

Sundberg, M. et al. Improved cell therapy protocols for Parkinson’s disease based on differentiation efficiency and safety of hESC-, hiPSC-, and non-human primate iPSC-derived dopaminergic neurons. Stem Cells. 31, 1548–1562 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Shawna Rideout-Gros for her assistance as a veterinary technician and Jennifer Sun for processing the histology. The author also would like to thank Dr. Harriet Lea-Banks for editing the manuscript. Funding for this work was provided by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health (R01 EB003268), the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (FRN 119312), the Temerty Chair in Focused Ultrasound Research at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, the Beamish Family Foundation, and the Connor family.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was designed by S.-K. W, C.-L. T, and K.H. Animal experiments, including the PD model, MRIgFUS, and behavioural testing, were performed by S.-K. W and C.-L. T. Behavioural analysis, immunohistochemistry, and stereological counting were performed by S.-K. W and A. M. Finally, the manuscript was written by S.-K. W, C.-L. T., A. M., and K.H. All authors contributed to and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

K.H. is a co-founder of FUS Instruments, a company that is commercializing the preclinical FUS system used in this work. S.-K. W, C.-L. T, and A. M. declare no competing interestst.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, SK., Tsai, CL., Mir, A. et al. MRI-guided focused ultrasound for treating Parkinson’s disease with human mesenchymal stem cells. Sci Rep 15, 2029 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85811-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85811-8