Abstract

Aptamers have shown potential for diagnosing clinical markers and targeted treatment of diseases. However, their limited stability and short half-life hinder their broader applications. Here, a real sample assisted capture-SELEX strategy is proposed to enhance the aptamer stability, using the selection of specific aptamer towards PD-L1 as an example. Through this developed selection strategy, the aptamer Apt-S1 with higher binding affinity and specificity towards PD-L1 was obtained as compared to the aptamer Apt-A2 which was screened by the traditional capture-SELEX strategy. Moreover, Apt-S1 exhibited a greater PD-L1 binding associated conformational change than Apt-A2, indicating its suitability as a biorecognition element. These findings highlight the potential of Apt-S1 in clinical applications requiring robust and specific targeting of PD-L1. Significantly, Apt-S1 exhibited a lower degradation rate in 10% diluted serum or pure human serum, under the physiological temperature and pH value, compared to Apt-A2. This observation suggested that Apt-S1 possesses higher stability and is more resistant to damage caused by the serum environmental factors, highlighting the superior stability of Apt-S1 over Apt-A2. Furthermore, defatted and deproteinized serum were used to investigate the potential reasons for the improved stability of Apt-S1. The results hinted that the pre-adaptation to nucleases present in serum during the selection process might have contributed to its higher stability. With its improved stability, higher affinity and specificity, Apt-S1 holds great potential for applications in PD-L1 assisted cancer diagnosis and treatment. Meanwhile, the results obtained in this work provide further evidence of the advantages of the real capture-SELEX strategy in improving aptamer stability compared to the traditional strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to their high target binding affinity and specificity1, low production cost and ease of modification, aptamers have been widely used as biorecognition elements in detecting drug residues, monitoring environmental pollutants and diagnosing clinical markers2. Moreover, aptamers can also be used as targeted agents for antibacterial, antiviral and cancer treatment3.

Although much progress has been made in aptamer applications, there are still some bottlenecks that hinder the further utilization of aptamers. One prominent bottleneck is the stability of aptamers, especially in practical applications. The low stability and short half-life of aptamers can result in their rapid clearance rate in vivo4, consequently leading to shortened durations for aptamer-assisted targeted therapy and imaging window time5. Therefore, it is urgently necessary to enhance the robustness (i.e., stability) of aptamers to bolster their applicability and effectiveness.

At present, chemical modification is the main strategy to enhance aptamer stability6. For example, imidazolium coordinated thymidine has been employed to modify the aptamer towards L-arginine amide to improve its detection stability7. However, this modification strategy would introduce extra labor and cost8, and some aptamers may not be easily amenable to chemical modifications9. Additionally, chemical modifications have the potential to alter the conformation of the aptamer, thereby reducing the degree of conformational change in the process of recognizing and binding to the target substance. Consequently, this limits the sensitivity of the detection system to a certain extent10. Therefore, it is imperative to explore alternative strategies for enhancing aptamer stability11.

Traditionally, aptamers were screened by the systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) strategy, capture SELEX or other derivative strategies12,13. Due to its high selectivity, sensitivity and diversity (Table S1), capture-SELEX finds extensive applications in biomedical research, including drug discovery, tumor marker identification, and biosensor development14. However, these approaches typically employ ordinary buffers as the screening system15, neglecting the inclusion of real samples that the aptamers would encounter in their intended applications. It is crucial to acknowledge that the composition, and physical and chemical factors contained in complex samples would seriously affect the stability of aptamers16, thereby discounting their detection performance. In our previous work, we introduced a real milk sample assisted SELEX strategy for selection of specific aptamer towards sarafloxacin (SAR)17. In this strategy, the real sample with which the aptamer would interact in real-work scenarios was employed during the screening process. This approach allowed the aptamer to undergo pre-adaptation to the complexities of the authentic sample in advance. Such pre-adaptation to real sample would confer aptamer resistance to adverse factors in the real sample. Here, to improve the aptamer stability, a real sample assisted capture-SELEX strategy illustrated by selection of specific aptamer towards PD-L1 (Programmed death ligand-1) is proposed (Fig. S1).

PD-L1, which is a member of B7 family with negative immune regulation effect18, can specifically recognize and bind to PD-1 on immune cells. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is an important immune checkpoint, which can inhibit the activation of T cells and help tumor cells to realize immune escape19. PD-L1 aptamer has been used for diagnosis and treatment of tumors, but its stability has not been considered20. PD-L1 aptamer with high stability would facilitate improving the efficiency of cancer diagnosis, imaging and targeted immunotherapy.

Here, a real sample assisted capture-SELEX strategy was proposed to screen aptamer towards PD-L1 from random sequence library. Based on such selection strategy, the aptamer Apt-S1 with higher PD-L1 binding affinity was obtained as compared to the aptamer Apt-A2 which was screened by the traditional capture-SELEX approach. More importantly, Apt-S1 suggested higher stability in human serum superior to that of Apt-A2. Meanwhile, defatted serum and deproteinized serum were respectively used to investigate the potential reasons for improved stability of aptamer screened by this selection strategy.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

The oligonucleotide single strands used in this work were respectively synthesized by Sangong Bioengineering (Shanghai, China) and GENEWIZ (Suzhou, China) using HPLC, tPage or hPage purification method, respectively, and listed in Table 1. PD-L1, PD-1, B7-1 and PD-L2 proteins were purchased from Acrobiosystems (Beijing, China). Streptavidin magnetic beads and magnetic beads for protein adsorption were purchased from Primag Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). The serum, defatted serum and deproteinized serum were respectively purchased from Solabao company (Beijing, China) and Nova Medical Technology (Shanghai, China). All chemicals used in this study were analytical grade or higher.

Real serum assisted screening of PD-L1 aptamer

The candidate aptamers specifically towards PD-L1 protein were respectively selected by serum assisted capture-SELEX strategy and traditional capture-SELEX strategy from random oligonucleotide sequence library. For the serum assisted capture-SELEX strategy, the human serum sample was diluted 10 × with traditional SELEX buffer (90 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 30 mM Tris–HCL, 10 mM KCl, pH 7.5) for use as the screening buffer. On the other hand, traditional SELEX buffer was still used for traditional capture-SELEX strategy.

Two hundred microliters of magnetic beads were vortexed for 30 s prior to being washed with washing buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM EDTA·Na2, 0.02 Tween 20, pH 7.5) three times. In the first round of screening, 10 μL of 10 μM ssDNA random library was mixed with 10 μL of 10 μM complementary probe before addition of 30 μL binding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCI, 1 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.02% Tween 20, pH 7.5) and incubation at 90℃ for 10 min. After being cooled at 0℃ for 20 min, 50 μL binding buffer and 50 μL ssDNA solution were added to the washed magnetic beads before being gently mixed at 30℃ for 30 min. After discarding the supernatant by magnetic separation, the magnetic beads were further washed with washing buffer three times. After removing the unbound ssDNA, 30 μL traditional SELEX buffer and 20 μL PD-L1 protein were respectively added before incubation at 30℃ for 30 min. After discarding the magnetic beads, the supernatant containing ssDNA was used as a template for PCR. A total of 50 μL volume was used for PCR amplification reaction. Fifty microliters of biotinylated PCR products were mixed with 100 μL washed magnetic beads before addition of 50 μL binding buffer and incubation at 30℃ for 1 h. After discarding the supernatant, 200 μL washing buffer was added to wash thrice before addition of 50 μL of 0.2 M NaOH and incubation at 37℃ for 30 min to generate ssDNA. After adjusting the pH value to 7.0, the denatured ssDNA was used as the secondary ssDNA library. Subsequently, the selection process was performed according to the procedure of the first screening round, and the concentrated ssDNA was repeatedly screened.

The recovery rate of concentrated ssDNA from each round was determined by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) with Mastercycler® EP Realplex2 (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). The Ct value was determined according to the qRT-PCR amplification curve, and while the Ct value stopped to change any more, the aptamer screening process could be completed.

Sequencing and structure analysis of the candidate aptamers

The candidate aptamers screened by two strategies were amplified by PCR, and PCR products were purified for high-throughput sequencing through large-scale parallel cloning and ligation DNA sequencing (Applied Biosystems CO. Ltd., Foster City, CA, USA). Predication of the secondary structures of the candidate aptamers were performed by the mfold software (http://mfold.rna.albany.edu).

Characterization of the candidate aptamers

The dissociation constant (Kd) values, specificities and PD-L1 binding associated conformational change of the candidate aptamers screened by two strategies were respectively determined.

Fifty microliters of PD-L1 were mixed with pre-washed agarose magnetic beads in 500 μL SELEX buffer at 35℃ for 5 min before washing three times with washing buffer to prepare the PD-L1-magentic bead complex. Human PD-L1 have a HIS tag (HPLC-verified), which allows for its binding with the agarose magnetic beads. After being incubated at 95℃ for 5 min and ice bath for 10 min, the FAM-modified candidate aptamers with different concentrations (0, 12.5, 25, 50, 100, 200, 500 and 1000 nM) were respectively incubated with the PD-L1-magentic bead complex in SELEX buffer to prepare the aptamer-protein-magnetic-bead complex. After incubation in the dark at 37℃ for 30 min and discarding the supernatant, the complex was further washed with SELEX buffer thrice before resuspension in SELEX buffer. The fluorescence intensity (i.e., at 480/520 nm) of the resuspended sample was determined by an EnSpire microplate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

The Kd value of aptamer was further determined by nonlinear fitting analysis according to the following equation21:

Here, F is the detected fluorescence intensity, Fmax is the maximum fluorescence intensity, and X is the aptamer concentration.

The candidate aptamers with the lowest Kd value respectively selected by traditional capture-SELEX strategy and real sample assisted capture-SELEX strategy were named as Apt-A2 and Apt-S1, respectively. The specificities of Apt-S1 and Apt-A2 towards PD-L1 were evaluated using PD-L1 and its structural analogs (i.e., PD-1, B7-1 and PD-L2). Moreover, the PD-L1 binding associated conformational changes of Apt-S1 and Apt-A2 were determined by circular dichroism (CD) analysis using a JASCO J-815 CD spectrometer (Tokyo, Japan). Each CD spectra data were collected from 220 to 320 nm at the 1 nm intervals, and the background spectrum of SELEX buffer solution was subtracted from the CD spectra data.

Characterization of the robustness of aptamers

The placement stabilities of Apt-A2 and Apt-S1 were determined to evaluate the contribution of real sample assisted capture-SELEX strategy on the robustness of aptamer towards PD-L1. The lower the Ct value of qPCR, the better the integrity of the nucleic acid template, and the lesser the damage to it; on the contrary, the more serious the degradation of the nucleic acid template. Therefore, the Ct values of Apt-A2 and Apt-S1 after being placed at different conditions to evaluate their placement stabilities.

Results and discussion

Candidate aptamers screened from two strategies

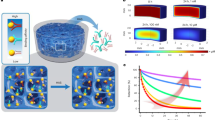

In the classical SELEX or capture-SELEX strategy, the aptamer undergoes a screening environment system that is different from the one in which it will ultimately encounter in its intended application. Such environmental inconsistency would further discount the stability and other detection performances of aptamer-based sensors22. To address this issue, subjecting the aptamer to a complex real sample during the screening process allows for pre-adaptation to the environmental factors it will encounter in its intended working environment. Based on such logic, our previous work proposed a real sample assisted SELEX strategy for selection aptamer specifically towards SAR17. Here, based on the principle of our previous selection strategy, a real sample assisted capture-SELEX strategy illustrated by screening specific aptamer towards PD-L1 is proposed to improve its stability (Fig. 1).

During the screening process, ssDNA sequences that could bind with PD-L1 were progressively enriched as the screening round number increased. The efficiency of the screening process was monitored by determining the recovery rate of ssDNA after each round. The calculation method for the recovery rate of ssDNA aptamers involved measuring the concentration of the supernatant before and after binding to PD-L1 using nanodrop ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometer. The recovery rate was determined by calculating the ratio of the concentration of the aptamer bound to PD-L1 to the initial concentration of the aptamer. The recovery rate for the two screening systems respectively reached 34.2% and 33.8% at the 8th round, and stopped to change after the 8th round (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, qRT-PCR results (represented by Ct value) also suggested that eight rounds could be considered as the optimal screening round number (Fig. S2). Therefore, the ssDNA sequences recovered from the 8th round were collected for subsequent sequencing for both selection systems.

Following high-throughput sequencing, eight candidate aptamers towards PD-L1 were selected from the two systems. The ssDNA sequences were ranked in descending order according to the relative frequencies of the ssDNA sequences obtained from the sequencing results. The top four sequences with the highest frequencies from each system were chosen for experimental validation. These potential aptamers were respectively named as Apt-A1, Apt-A2, Apt-A3 and Apt-A4 for traditional capture-SELEX selection system and Apt-S1, Apt-S2, Apt-S3 and Apt-S4 for the human serum assisted selection system.

Characterization of the potential aptamers

The secondary structures of these candidate aptamers were predicted using the mfold software, and results suggested the presence of loop and hairpin structures in these ssDNA sequences (Fig. 3A and B; Fig. S3). Moreover, G-quadruplex structure can promote the recognition and binding of aptamers with their target molecules. Therefore, Apt-A2 and Apt-S1, which exhibited G-quadruplex structures and displayed the lowest folding energies, suggest higher stability of these aptamers, preliminarily indicating their potential for strong binding with PD-L1.

Characterization of Apt-S1 and Apt-A2. (A) Predicated secondary structure of Apt-S1. (B) Predicated secondary structure of Apt-A2. (C) The Kd value of Apt-S1. (D) The Kd value of Apt-A2. (E) The specificity of Apt-S1 for PD-L1 and its structural analogs (i.e., PD-1, B7-1 and PD-L2). (F) The specificity of Apt-A2 for PD-L1 and its structural analogs (i.e., PD-1, B7-1 and PD-L2). (G) Circular dichroism spectra of Apt-S1 before and after addition of PD-L1. (H) Circular dichroism spectra of Apt-A2 before and after addition of PD-L1. The error bars are defined by the standard deviation of the results from three parallel experiments.

Moreover, the Kd values of the selected candidate aptamers were also determined. The Kd values of Apt-A1, Apt-A2, Apt-A3, Apt-A4, Apt-S1, Apt-S2, Apt-S3 and Apt-S4 were 154.15 ± 21.23, 94.15 ± 14.13, 151.4 ± 18.73, 168.45 ± 19.87, 87.74 ± 12.63, 91.31 ± 11.98, 103.77 ± 15.17 and 99.25 ± 18.22 nM, respectively (Fig. 3C and D; Fig. S4). Here, Apt-A2 and Apt-S1 with the lowest Kd values from respective screening system also confirmed the results of the secondary structure analysis. These aptamers were subsequently selected for further analysis of specificity and robustness. Notably, although the Kd value of Apt-A2 was only slightly higher than that of Apt-S1, the Kd values of candidate aptamers screened by traditional capture-SELEX strategy were significantly higher than those obtained from the real serum assisted capture-SELEX strategy. This stark difference highlighted the substantial contribution of using real samples in enhancing binding abilities of candidate aptamers towards PD-L1.

Both Apt-A2 and Apt-S1 exhibited significantly stronger fluorescence intensity upon binding to PD-L1 in comparison to the blank control and other structural analogues (i.e., PD-1, B7-1 and PD-L2), suggesting their high selectivity for PD-L1 (Fig. 3E and F). More importantly, the PD-L1 binding associated fluorescence intensity of Apt-S1 was stronger than that of Apt-A2, further confirming its superior specificity towards PD-L1.

Aptamer conformational changes associated with PD-L1 binding

The circular dichroism (CD) spectra were used to analyze the PD-LI binding associated conformational changes of Apt-A2 and Apt-S1. After binding with PD-L1, Apt-A2 exhibited an increment at 250 nm and 265 nm (Fig. 3H). Meanwhile, PD-L1 binding caused a significant increment slope between 220–255 nm in Apt-S1 (Fig. 3G). CD spectra of nucleic acids can provide a lot of useful structural information23; and the larger CD spectral signal change is associated with the higher detection sensitivity of potential aptamer-based sensor24. Here, the results of conformational changes suggested that, compared to Apt-A2, Apt-S1 was more suitable for being used as a biorecognition element in developing aptasensors or targeted treatments with higher sensitivity.

Evaluation of robustness of aptamers

The higher the amount of the initial DNA template, the sooner amplificated product is detected during the PCR process, and the lower the Ct value25. In other words, the lower the Ct value, the higher the amount of DNA template, and the lower the degree of template damage. The Ct values of Apt-S1 and Apt-A2 at 37℃ were lower than their Ct values at 27℃ and 32℃ (Fig. S5), indicating that human physiological temperature (i.e., 37℃) is more suitable for maintaining their stability. Under physiological temperature (i.e., 37℃) and pH value (i.e., 7.4), both Apt-A2 and Apt-S1 exhibited an increase in Ct values over time when placed in either 10% diluted serum or pure human serum (Fig. 4A and B). Such result suggested the gradual degradation of Apt-A2 and Apt-S1 during the placement period. Electrophoresis results also suggested that whether in pure human serum or 10% diluted serum, Apt-S1 and Apt-A2 were gradually degraded with the prolongation of placement time (Fig. S6). More importantly, the Ct value of Apt-A2 was consistently higher than that of Apt-S1 during the placement, indicating that Apt-A2 was more susceptible to damage from the serum environmental factors. Meanwhile, in both placement systems, the dispersion degree of Apt-S1 was also lower than that of Apt-A2 (Fig. S6), further demonstrating the superior placement stability of Apt-S1 compared to Apt-A2. Such results confirmed the higher robustness of Apt-S1 which was screened from pre-adapted serum environment in comparison to that of Apt-A2. Then, the next worthy issue is to clarify the potential contribution of the real sample assisted capture-SELEX to the enhanced robustness of the PD-L1 aptamer.

To further investigate the potential influence of different components in the serum, the placement stability of Apt-A2 and Apt-S1 in defatted and deproteinized serum was respectively evaluated. During the placement period, the stability of Apt-A2 and Apt-S1 in defatted serum was similar to that in pure serum (Fig. 4C). However, both the Ct values of Apt-A2 and Apt-S1 in deproteinized serum at different placement time points were lower than those in pure serum (Fig. 4D). Serum contains thermostable proteins such as nucleases that can degrade aptamers or other nucleic acid fragments26. The lower Ct values observed in deproteinized serum suggest the potential role of proteins in serum in influencing the stability of PD-L1 aptamer. Furthermore, these findings also suggested us that the pre-adaptation to nucleases present in serum during the selection process might have contributed to the improved robustness of Apt-S1.

Conclusion

In summary, a real serum sample assisted capture-SELEX strategy was proposed to screen PD-L1 aptamer with improved robustness (i.e., stability) from random sequence library. As a proof of concept, the aptamer Apt-S1, identified using the real capture-SELEX strategy, demonstrated higher affinity and specificity towards PD-L1 compared to the aptamer Apt-A2 screened by the traditional capture-SELEX strategy. Furthermore, Apt-S1 exhibited a greater PD-L1 binding associated conformational change. More importantly, Apt-S1 demonstrated increased resistance to the serum environmental factors, indicating its superior robustness compared to Apt-A2. Notably, this work presents the first report of improved aptamer stability in the presence of real samples. The improved robustness, along with higher affinity and specificity exhibited by Apt-S1, holds significant potential for its application in PD-L1 assisted cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Data availability

The data presented in the work are included in the article / supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

Tombelli, S., Minunni, M. & Mascini, M. Analytical applications of aptamers. Biosens. Bioelectron. 20, 2424–2434 (2005).

Krüger, A., de Jesus Santo, A. P., de Sá, V., Ulrich, H. & Wrenger, C. Aptamer applications in emerging viral diseases. Pharmaceuticals 14, 622 (2021).

Chen, A. & Yang, S. Replacing antibodies with aptamers in lateral flow immunoassay. Biosens. Bioelectron. 71, 230–242 (2015).

Chen, W., Voos, K. M., Josephson, C. D. & Li, R. Short-acting anti-VWF (von Willebrand factor) aptamer improves the recovery, survival, and hemostatic functions of refrigerated platelets. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 39, 2028–2037 (2019).

Adler, A., Forster, N., Homann, M. & Göringer, H. U. Post-SELEX chemical optimization of a trypanosome-specific RNA aptamer. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen 11, 16–23 (2008).

Prabhakar, P. S., Manderville, R. A. & Wetmore, S. D. Impact of the position of the chemically modified 5-furyl-2’-deoxyuridine nucleoside on the thrombin DNA aptamer-protein complex: Structural insights into aptamer response from MD simulations. Molecules 24, 2908 (2019).

Verdonck, L. et al. Tethered imidazole mediated duplex stabilization and its potential for aptamer stabilization. Nucl. Acid. Res. 46, 11671–11686 (2018).

Chen, H. et al. Aptamer modification improves the adenoviral transduction of malignant glioma cells. J. Biotechnol. 168, 362–366 (2013).

Shen, R., Tan, J. & Yuan, Q. Chemically modified aptamers in biological analysis. ACS Appl. Bio. Mater. 3, 2816–2826 (2020).

Jiang, Y. et al. Supramolecularly engineered circular bivalent aptamer for enhanced functional protein delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 6780–6784 (2018).

Zhao, J. et al. Analyte-resolved magnetoplasmonic nanocomposite to enhance SPR signals and dual recognition strategy for detection of BNP in serum samples. Biosens. Bioelectron. 141, 111440 (2019).

Zhu, C. et al. Recent progress of SELEX methods for screening nucleic acid aptamers. Talanta 16, 124998 (2024).

Wang, T., Chen, C., Larchera, L. M., Barreroa, R. A. & Veedu, R. N. Three decades of nucleic acid aptamer technologies: Lessons learned, progress and opportunities on aptamer development. Biotechnol. Adv. 7, 28–50 (2019).

Qian, S. W., Chang, D. R., He, S. S. & Li, Y. F. Aptamers from random sequence space: Accomplishments, gaps and future considerations. Anal. Chim. Acta 1196, 339511 (2022).

Mirian, M. et al. Generation of HBsAg DNA aptamer using modified cell-based SELEX strategy. Mol. Biol. Rep. 48, 139–146 (2021).

Zhou, J. & Rossi, J. Aptamers as targeted therapeutics: Current potential and challenges. Nat. Rev. Drug. Discov. 16, 181–202 (2017).

Ding, Y. J., Gao, Z. H. & Li, H. Real milk sample assisted selection of specific aptamer towards sarafloxacin and its application in establishment of an effective aptasensor. Sens. Actuat. B-Chem. 343, 130113 (2021).

Dermani, F. K., Samadi, P., Rahmani, G., Kohlan, A. K. & Najafi, R. PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint: Potential target for cancer therapy. Cell Physiol. 234, 1313–1325 (2019).

Boutros, C. et al. Safety profiles of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 antibodies alone and in combination. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 13, 473–486 (2016).

Lin, B. et al. Tracing tumor-derived exosomal PD-L1 by dual-aptamer activated proximity-induced droplet digital PCR. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 60, 7582–7586 (2021).

Zhou, N. et al. Selection and identification of streptomycin-specific single-stranded DNA aptamers and the application in the detection of streptomycin in honey. Talanta 108, 109–116 (2013).

Sola, M. et al. Aptamers against live targets: Is in vivo SELEX finally coming to the edge. Mol. Ther. Nucl. Acid. 21, 192–204 (2020).

Del Villar-Guerra, R., Trent, J. O. & Chaires, J. B. G-quadruplex secondary structure obtained from circular dichroism spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 57, 7171–7175 (2018).

Liang, S. et al. Measuring luteinising hormone pulsatility with a robotic aptamer-enabled electrochemical reader. Nat. Commun. 10, 852 (2019).

Dorak, M. T. Real-Time PCR. In Advanced Methods Series (ed. Dorak, M. T.) (Oxford Taylor & Francis, 2006).

von Köckritz-Blickwede, M., Chow, O. A. & Nizet, V. Fetal calf serum contains heat-stable nucleases that degrade neutrophil extracellular traps. Blood 114, 5245–5246 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 82174531) and High-Level Scientific Research Project Cultivation Program of Jining Medical University (No. JYGC2023KJ010).

Funding

National Nature Science Foundation of China,82174531,High-Level Scientific Research Project Cultivation Program of Jining Medical University,JYGC2023KJ010

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z., H.Z.Z. and H.L. performed the methodology; Y.Z., H.Z.Z. and Y.J.D performed the investigation; Y.Z. and H.Z.Z. performed the data curation; Y.Z. and H.Z.Z. wrote the original manuscript text; C.Y.Y. and H.L. reviewed and edited the manuscript text; H.L. concepted and supervised the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, Y., Zhang, H., Ding, Y. et al. Serum assisted PD-L1 aptamer screening for improving its stability. Sci Rep 15, 1848 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85813-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85813-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Aptamers in bioanalytical chemistry: current trends in development and application

Science China Chemistry (2025)