Abstract

Schistosomiasis poses a significant global health threat, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions like Sudan. Although numerous epidemiological studies have examined schistosomiasis in Sudan, the genetic diversity of Schistosoma haematobium populations, specifically through analysis of the mtcox1 gene, remains unexplored. This study aimed to investigate the risk factors associated with urogenital schistosomiasis among school pupils in El-Fasher, Western Sudan, as well as the mtcox1 genetic diversity of human S. haematobium in this region. A cross-sectional study was conducted among school pupils aged 4 to 19 years. In total, 196 urine samples and 196 fecal samples were collected from participants across schools, health centers, and refugee camps in El-Fasher. Samples were examined using simple centrifugation/sedimentation technique and formol-ether concentration method to detect S. haematobium and S. mansoni eggs, respectively. S. haematobium mtcox1 partial gene was amplified and sequenced by the Sanger technique. A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was generated by MEGA software, and a haplotype network was constructed using PopART v.1.7 with the median-joining network method. In this study, S. haematobium was detected in 6.1% (12/196) of the participants while no S. mansoni ova were observed in fecal samples. The infection was more common among those who relied on indirect water supply like tankers (6, 50%). No infection was observed among residents of refugee camps. Only eight samples were PCR-positive, which were successfully sequenced, and included in the genetic diversity analysis. A unique haplotype (Hap_1) with no sequence diversity was found among cox1 sequences from El-Fasher strains. Both El-Fasher S. haematobium haplotype (Hap_1) and Gezira haplotype (Hap_31) fall within the mainland Africa group (group 1). In conclusion, this study identified a novel S. haematobium strain and provides insights into the evolutionary history and phylogeography of S. haematobium in Sudan, particularly in the western region. This genetic data could help in the control and monitoring of urogenital schistosomiasis in this region. For the first time, we utilized the DNA mtcox1 barcoding to investigate S. haematobium haplotypes in Western Sudan.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schistosoma is a genus of trematodes, or parasitic flatworms, responsible for schistosomiasis, also known as bilharzia or snail fever, which is a significant health concern in humans and animals1. The World Health Organization (WHO) ranks schistosomiasis as the second-most important parasitic disease after malaria, especially in tropical regions2,3. An estimated 250 million people are infected worldwide, with around 700 million at risk4. The WHO reports that schistosomiasis is recorded in 78 countries, with 90% of infected individuals requiring treatment located in Africa5. The disease predominantly affects children aged 6 to 15 years, who exhibit the highest prevalence and intensity of infection6,7. In Sub-Saharan Africa, S. mansoni (which causes intestinal schistosomiasis) and S. haematobium (responsible for urogenital schistosomiasis) are estimated to cause 280,000 deaths per year8. The main approaches to controlling schistosomiasis include drug treatment of infected patients and snail control9,10. Thus, effective diagnosis and identification of schistosome infection are crucial for treating schistosomiasis and significantly reducing the endemicity of the disease. The emergence of advanced molecular and bioinformatics techniques has made species identification easier, enhancing diagnostic accuracy. In many developing countries with endemic schistosomiasis, microscopical examination is commonly used to identify schistosome eggs in stool and urine samples, due to its quick, easy, and inexpensive nature11. Additionally, other studies have employed DNA sequence-based identification techniques by targeting the species-specific genes encoding for the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (cox1) to identify Schistosoma species11,12,13,14. The cox1 gene is found universally within mitochondrial genomes and is recognized as a useful DNA barcoding region to infer species identification and explore haplotype diversity15,16. The cox1 gene represents a significantly conserved segment with a higher phylogenetic signal than other mitochondrial genes17,18. Some authors declare that the cox1 gene is highly effective for rapid discrimination between closely related species and for evaluating intraspecific diversity among species18,19,20.

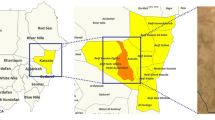

Schistosomiasis undeniably represents a global health threat, particularly in tropical and semi-tropical regions like Sudan. In Sudan, schistosomiasis remains a major public health concern, with over eight million individuals estimated to be at risk of infection21,22,23. Studies on Schistosoma began in the early twentieth century24, with significant contributions made in the 1980s25,26. The disease is endemic, with reported prevalence rates of urogenital and intestinal schistosomiasis in various regions of the country21,22,23. Several factors, including the expansion of irrigation projects, drought, storms, recurrent floods, lack of access to safe and clean drinking water, and poor hygiene, play a significant role in the endemicity of schistosomiasis in Sudan27. Although available data shows a high rate of Schistosoma transmission among the local Darfur population28,29,30, studies that address schistosomiasis in Darfur state are scarce. In a previous study, we examined the frequency of urogenital schistosomiasis in school children in El-Fasher31. El-Fasher is the largest city and the capital of the North Darfur State in Sudan. The ongoing conflict and humanitarian crises in the Western region have resulted in internally displaced persons (IDP) camps, which house vulnerable populations, including children at risk of infectious diseases32. Over 4.5 million refugee population (including IDPs) were internally displaced, with nearly 3 million residing in camps in Darfur33. Sampling from these camps is essential for providing crucial insights into the prevalence and impact of the disease in conflict-affected regions, such as North Darfur. School-aged children living in areas with poor sanitation are particularly at risk due to their tendency to spend time swimming or bathing in water contaminated with infectious cercariae34.

Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the risk factors associated with urogenital schistosomiasis among school pupils in El-Fasher. Notably, no S. mansoni ova were observed in the fecal samples. Furthermore, we investigated the mtcox1 variation of human S. haematobium in Western Sudan. Despite the numerous epidemiological studies on schistosomiasis in Sudan, the genetic diversity of the S. haematobium population using mtcox1 remains unexplored. These findings will offer a better understanding of the genetic diversity, variable disease manifestations, and epidemiology of S. haematobium in Western Sudan and its relationship with other geographical populations. It could also help in developing new strategies for treatment, vaccination, and diagnosis of the disease in the region.

Results

Examination of urine and fecal samples for shistosoma in school children

Microscopic examination revealed the presence of S. haematobium eggs in 12 samples (6.1%) (Fig. 1), of which eight (66.67%) were confirmed positive by PCR analysis. Additionally, microscopic examination of 196 fecal samples did not reveal any S. mansoni ova, indicating a negative result for fecal schistosomiasis.

Factors associated with S. haematobium infection

All participants were male and regularly came into contact with contaminated water from Foula pond for activities such as washing and playing, typically for more than 30 min around midday. As indicated in Table 1, the study population was categorized based on their water sources, which included direct water supply (canals and faucets) and indirect water supply (tankers and donkey-assisted water carriers). In this study, the highest prevalence of S. haematobium was observed among those who relied on indirect water supply like tankers (6, 50%). Conversely, there were no positive cases of Schistosoma infection among those who relied on faucets for their water supply. Regarding the residents of the study population, schistosomiasis was most prevalent among household dwellers, with Makraka having the highest prevalence (11, 91.67%), followed by Tambasie (1, 8.33%). In contrast, no infections were found among residents of the camps (p = 0.2191). In addition, the study population was grouped depending on their age as follows: 10–15 years, 16–19 years, and 4–9 years. The highest prevalence of urogenital schistosomiasis was observed in individuals aged 10 to 15 years (8 positives, constituting 66.67%), followed by those aged 16 to 19 years, and 4 to 9 years, each with a prevalence of 16.67% (p = 0.5839), as illustrated in Table 1.

In the present study, hematuria was detected in 14 out of the 196 urine samples (7.14%). Of these, 12 samples tested positive for S. haematobium, while 2 samples tested negative for the presence of S. haematobium eggs. The remaining 182 urine samples, which showed no signs of hematuria, also tested negative for schistosomiasis. As indicated in Table 1, a significant association was observed between the presence of hematuria and Schistosoma infection (p < 0.0001).

Results of the molecular phylogenetic and haplotype analysis

Sequences of partial cox1 detected from El-Fasher S. haematobium strains, isolated from Western Sudan, revealed four nucleotide variations when compared with the reference sequence (NC_008074), see Fig. 2. These nucleotide variations were found at four positions (positions 708, 1235, and 1237–1238, the position numbering is according to the reference sequence). Interestingly, El-Fasher strains and Senegal strains displayed a high degree of similarity in these variations. On the other hand, Gezira strains, isolated from Central Sudan, shared the same nucleotide variation with South African strains and showed high similarity with strains from Egypt (Fig. 2).

The median-joining haplotype network inferred from cox1 sequences of El-Fasher S. haematobium strains showed two groups when compared with other highly similar cox1 sequences from Africa and Asia. Both groups are linked via a long line with multiple hatches that indicate mutational steps. They contain haplotypes predominately from mainland Africa with haplotypes from Zanzibar and the three haplotypes of Hodeidah in Yemen. The majority of the samples are clustered around the main haplotype (Hap_2) by a separate single line with up to three mutations. Sudanese strains haplotypes, from El-Fasher (Hap_1) and Gezira (Hap_31), are present in group 1. El-Fasher strains and Senegal strains (Hap_3, Hap_4, and Hap_2) shared close common ancestries, with the two groups being separated by missing or unsampled haplotypes and originating from a common haplogroup (Hap_2). Gezira strains shared the same haplotype (Hap_31) with South African strains (Fig. 3). Group 2 forms networks between Tanzania, Zanzibar, and Coastal Kenya.

Median-joining haplotype network inferred from the cox1 partial sequences of the El-Fasher S. haematobium strains (red color) showing mutations when compared with other related regional and Asian (Yemen) strains. Haplotypes are indicated with circular nodes, with node size representing haplotype frequency and different node colors indicating the geographic distribution of samples. Hatch marks on lines connecting nodes represent mutational steps while missing individuals or unsampled haplotypes are symbolized by small black nodes. El-Fasher strains are released individuals.

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the phylogenetic tree represents the relationships among a set of S. hematobium strains from different countries. The S. hematobium strains grouped into two branches. El-Fasher strains were present in the same clade with the Senegal strain (FJ586241) while Gezira strain shared the same clade with the South African strain (JQ397397).

Discussion

In this study, for the first time, we utilized the DNA cox1 barcoding to investigate S. haematobium haplotypes in Western Sudan. Interestingly, a unique haplotype (Hap_1) with no sequence diversity was found between partial cox1 sequences of strains isolated from school pupils in the El-Fasher region of Sudan. This suggests that there is a single dominant strain in the region, or these pupils may have been infected from a common source, i.e. Foula pond. However, increasing the sample size could reveal greater diversity among strains. In conformity with our findings, Quan et al. studied genetic diversity in S. haematobium isolated from the White Nile State in Southern Sudan by a randomly amplified polymorphic DNA marker ITS2 using PCR–RFLP analysis. The study found that most strains exhibited a pan-African S. haematobium genotype, indicating a high degree of genetic uniformity across the region35. In a previous study, Webster et al. reported low levels of genetic diversity among 61 unique haplotypes from across Africa36. Also, Sady et al. found that the genetic diversity of S. haematobium was low across Yemen37.

When compared with other strains with highly similar cox1 sequences through multiple sequence alignment, the El-Fasher S. haematobium strains shared a unique haplotype with four nucleotide variations (positions 708, 1235, and 1237–1238) (Fig. 2). In order to understand the biogeography and history of these strains, PopART was employed to infer and visualize the genetic relationship between these strains and other regional strains through the median-joining (MJ) method38. MJ evolutionary network showed two groups linked via a long branch with multiple hatches, each representing a mutational step. Both groups primarily consist of haplotypes from mainland Africa, along with haplotypes from Zanzibar and three specific haplotypes from Hodeidah in Yemen (Fig. 3). As presented in the literature, DNA cox1 barcoding of S. haematobium populations revealed that the 61 unique haplotypes are split into two distinct groups. One group contains haplotypes predominantly from mainland Africa, with a few haplotypes from Zanzibar (Group 1), while the other comprises samples exclusively from the Indian Ocean islands and neighboring African coastal regions (Group 2)36. In accordance with our findings, Sady et al. found that the haplotypes from Hodeidah are involved in group 137.

El-Fasher haplotype (Hap_1) was linked with highly diverse haplotypes from Senegal, with two black nodes corresponding to unknown haplotypes. This indicates that these haplotypes may either have become extinct or have not yet been sampled, implying the potential for undiscovered genetic diversity in these regions. Gezira strains, which were isolated from Central Sudan, shared the same haplotype (Hap_31) with South African strains. This indicates that the Gezira region may have experienced an inflow of South African S. haematobium, or vice versa, through human migration and trade (Fig. 3). The Hap_31 of Gezira strains also had a direct genealogy with the haplotypes of Egypt and Kenya strains, Hap_32 and Hap_27, respectively. Additionally, it had a link with a Hap_2 of strains isolated from the East African region (Tanzania, Mozambique, and Zanzibar), Senegal, and Hodeidah in Yemen. Based on geographical data, the White Nile River passes through Uganda and South Sudan, connecting Lake Victoria to Sudan and Egypt. Lake Victoria is in East Africa and is bordered by Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya. This suggests the spread of genetically similar strains of S. haematobium from East Africa to Sudan and Egypt may be attributed to the lake or the spread of the water-dwelling intermediate snail host, belonging to the genus Bulinus. It is worth mentioning that the Kenyan strain inflow has been reported in the White Nile State of Southern Sudan35. The movement of people between Sudan, Egypt, and Yemen driven by factors such as familial connections, employment opportunities, and educational pursuits, may facilitate the spread of genetically related S. haematobium strains across these regions. Notably, the majority of haplotypes diverged from Hap_2 by a single link with up to three mutations, connecting to other haplotypes. This suggests that Hap_2 persists within populations and spreads across different regions, likely facilitated by population movement.

In this study, S. haematobium was detected in 12/196 (6.1%) of school pupils in El-Fasher, which disagrees with studies conducted in various parts of Sudan22,27,29,30,39. Microscopic examination revealed hematuria in 85.7% of individuals with a significant association with S. haematobium infection. This is consistent with a study conducted in Al-Lamab Bahar Abiad, Khartoum, which reported a hematuria rate of 77.8% among infected individuals40. No presence of S. mansoni was detected in fecal samples. In contrast, previous studies conducted in other regions of Sudan have reported S. mansoni infection rates of 2.95%, 5.9%, and 0.9% in Um Asher, the White Nile River basin, and Gezira, respectively22,30,39. Meanwhile, in Egypt, the prevalence was higher (4.3%)41. These differences may be attributed to the absence of detected Biomphalaria snails, the intermediate host of S. mansoni, in the El-Fasher region owing to environmental conditions that may not be suitable for the survival and distribution of Biomphalaria snails. In El-Fasher, especially at the edges of the Foula pond, the snails that were detected and morphologically identified, according to the Sudanese Health Ministry guide on schistosomiasis, belonged to the Bulinus genus (Fig. 1).

The prevalence of S. haematobium in the study population varied based on water sources. Higher infection rates were observed among individuals relying on tankers, canals, and donkey-assisted water carriers for their water supply. No infections were found among those who relied on faucets, which provide treated water. A previous study in North Darfur state indicated that water pollution in the area is primarily associated with the methods of water transportation, storage, and handling, rather than the water sources themselves42. Moreover, a lack of significant association was observed between the infection and the age groups within the study population, consistent with a previous study22, but conflicting with findings from a study conducted in Khartoum40. Additionally, the current study indicated that pupils residing in Tambasae and Makraka areas exhibited the highest infection rates in contrast to those residing in the Nifasha and Zamzam camps. This could be because hygienic conditions and sanitation systems in the camps were better, as the water was regularly checked, and disposal of human excreta and sewage was adequately treated42. Therefore, providing clean water supplies and adequate sanitary systems are required, alongside snail control, to prevent the spread of schistosomiasis in the western region of Sudan, especially in El-Fasher.

We acknowledge certain limitations in this study, particularly the limited number of positive cox1 gene samples, almost all of which were from Makraka, with only one from Tambasae. The lack of sequence diversity in the cox1 gene could be due to a single dominant strain in the southern part of this region (where Makraka is located) or it may indicate that these pupils were infected from a common source, such as Foula Pond, a primary water source for the inhabitants of El-Fasher. It is possible that the genetic diversity among S. haematobium populations in western Sudan could become more apparent with an increased sample size. Therefore, further studies with larger sample sizes are recommended. Additionally, while adding 10% formalin to the positive samples primarily serves to preserve the schistosome eggs and prevent microbial degradation during transport, formalin may impact DNA quality for molecular analysis. To mitigate this, formalin-fixed samples were washed three times with MilliQ water and centrifuged to remove residual formalin. Furthermore, as Schistosome DNA was extracted and amplified from whole urine samples, the resulting DNA sequences represent the genetic profile of a pooled S. haematobium population infecting each individual host. However, no mixed chromatogram peaks or multiple peaks at single nucleotide positions (in the case of mutations) were observed, suggesting that the haplotypes accurately reflect the genetic diversity within the S. haematobium populations.

In conclusion In this study, S. haematobium was detected in 6.1% of the school pupils in El-Fasher, which disagrees with studies conducted in various parts of Sudan. For the first time, we utilized the DNA cox1 barcoding to investigate S. haematobium haplotypes in Western Sudan. Interestingly, one unique haplotype (Hap_1) with no sequence diversity was found between partial cox1 sequences of El-Fasher strains. El-Fashir S. haematobium haplotype (Hap_1) and Gezira haplotype (Hap_31) fall within the African mainland S. haematobium cox1 group. This study provides an insightful understanding of the evolutionary history and phylogeography of S. haematobium in Sudan, particularly in the western region. The genetic data presented could therefore contribute to the monitoring and control of urogenital schistosomiasis in the country.

Methods

Study design and study setting

This cross-sectional study was carried out in El-Fasher, the capital of the North Darfur State in Sudan. Samples were collected from various schools, health centers, and camps throughout the city. The residential areas that make up the sample collection are Tambasie in the north, Makraka located in the south, and Awlad Elreef situated in the west of the city. The city’s north and south are home to the camps Zamzam and Nifasha, respectively. Water sources for daily activities include tankers, wells, canals, ponds, and tap water, typically transported by donkeys, tankers, or cars. In the center of El-Fashir city, there is a large pond called Foula, which fills with rainwater every autumn but gradually decreases and sometimes even dries up in the winter. This pond contains Bulinus snails (Fig. 1). The pond serves as a water source, especially for villagers who come with donkeys to sell their wares in markets near the pond. Children often swim in this pond on their way back from school, especially in the summer, and cars are washed along its banks.

Study population

The sample size was estimated according to the equation N = t2 * p (1-p)/m2, where a 95% confidence level (t), 15% prevalence of the disease (p), and a 5% margin of error (m) were assumed. According to the sample size calculation, a total of 196 urine and 196 fecal samples were collected randomly for this study. Samples were obtained from all 196 participants (100%) who were provided with collection tubes. In line with guidance from the National Schistosomiasis Control Program (NSCP) in El-Fasher, and based on a preliminary survey of 30 randomly selected females that showed no cases of schistosomiasis, only males were recruited as participants. Although this selection may limit generalizability to the entire population, it enhances the depth and relevance of the findings within this higher-risk group. The participants included school pupils, ranging in age from 4 to 19 years, with a mean age of 11.5 years. We included individuals up to age 19 who were still in school, as they may be affected by similar risk factors or exposures as younger school-aged individuals.

Urine and stool samples were requested to be provided in dry, clean, well-labeled plastic containers. Approximately, 5–10 ml of urine and 5–7 g of feces were collected. The samples were collected between 10:00 am and 2:00 pm, as this period was reported as the time of maximum egg excretion10. Positive samples were preserved in 10% formalin. Moreover, sociodemographic and associated risk factors were obtained via a standardized questionnaire.

Macroscopical examination

Urine specimens were examined macroscopically for appearance and color. Hematuria and chemical properties were assessed using reagent strips manufactured by Laboquick Ltd., Turkey. Stool specimens were visually examined for consistency, color, and the presence of worms.

Microscopical examination

Urine samples were microscopically examined for the presence of S. haematobium eggs by using the simple centrifugation/sedimentation technique, as previously described43. Eggs were counted, and the result was recorded as eggs per 10 ml of urine. For the microscopic diagnosis of S. mansoni infection in fecal samples, the formol-ether concentration method was performed44. The result obtained was expressed as eggs per gram of feces.

All microscopic slides containing the eggs of S. haematobium or S. mansoni were considered positive, whereas the absence of the eggs was recorded as negative.

Molecular detection of S. haematobium

DNA extraction

Prior to DNA extraction, fixed urine samples were washed three times in MilliQ water and centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 5 min to remove formalin. To extract the genetic materials of Schistosoma eggs, the G- DEX™ IIb Genomic DNA extraction kit was used, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

PCR amplification of cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) gene

For molecular detection of S. haematobium, the partial cox1 mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) region was amplified using a universal forward primer Shb.F (5′-TTTTTTGGTCA TCCTGAGGTGTAT-3′) and species-specific reverse primer, Sh.R (5′-TGATAATCAATGACCCTGCAATAA-3′) for S. haematobium45. The PCR amplification was carried out with the FIREPol Master Mix (Estonia) and a PCR thermocycler (BioRAD, USA). The temperature cycle for the PCR was an initial step at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, 72 °C for 1 min, and the final extension step was prolonged for 7 min at 72 °C45. Amplicons were visualized and sized on a 2% agarose gel stained with SYBR Safe DNA (Invitrogen, Auckland, New Zealand). The amplified product for the specific mtcox1 gene is 543 bp.

DNA sequencing mtcox1 gene

The PCR products of the cox1 gene were commercially purified and sequenced using the Sanger dideoxy sequencing method at Macrogen Inc., Korea.

Bioinformatics analysis

Sequence analysis

The two chromatograms (forward and reverse) of the cox1 gene for each strain were visualized and analyzed using the Finch TV program version 1.4.046. The nucleotide Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLASTn; https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) was applied to search for highly similar sequences deposited in the NCBI GenBank database. The cox1 sequences were deposited in the GenBank nucleotide database under the accession numbers ON237715 to ON237719.

Molecular phylogenetic and haplotype analysis

For multiple sequence alignment (MSA), our cox1 sequences, along with highly similar sequences retrieved from the NCBI GenBank, were aligned using Clustal W2-BioEdit software47. The Gblocks server was then applied to eliminate poorly aligned positions48. Nucleotide divergence parameters, including haplotype diversity (h), nucleotide diversity (π), and the number of polymorphic sites (S) within a haplotype, were calculated using the Dna Sequence Polymorphism (DnaSP Version 6.12.03) software by utilizing the Jukes-Cantor correction model49. Rate variation among sites was modeled with a gamma distribution (shape parameter = 1), and evolutionary analyses were conducted using MEGA 1150. A neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was generated based on the Jukes-Cantor method with a bootstrap value of 100051. The haplotype network was constructed using the PopART Version 1.7 through the median-joining network method38.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.5.0 software. Bivariate analysis for categorical variables was conducted using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05, with a 95% confidence interval.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the GenBank nucleotide database repository under the accession numbers ON237715 to ON237719.

References

Colley, D. G., Bustinduy, A. L., Secor, W. E. & King, C. H. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet (London, England) 383, 2253–2264 (2014).

Sarvel, A. K., Oliveira, A. A., Silva, A. R., Lima, A. C. L. & Katz, N. Evaluation of a 25-year-program for the control of schistosomiasis mansoni in an endemic area in Brazil. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 5, e990 (2011).

WHO. Schistosomiasis 2015. WHO https://www.who.int/en/newsroom/fact-sheets/detail/schistosomiasis (2015)

Pumipuntu, N. Detection for potentially zoonotic gastrointestinal parasites in long-tailed macaques, dogs and cattle at Kosamphi forest park. Maha Sarakham Vet. Integr. Sci. 16(2), 69–77 (2018).

WHO. Schistosomiasis. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact (2022)

Amuta, E. U. & Houmsou, R. S. Prevalence, intensity of infection and risk factors of urinary schistosomiasis in pre-school and school aged children in Guma Local Government Area, Nigeria. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 7, 34–39 (2014).

Gbalégba, N. G. C. et al. Prevalence and seasonal transmission of Schistosoma haematobium infection among school-aged children in Kaedi town, southern Mauritania. Parasit Vectors 10, 1–12 (2017).

Pearce, E. & MacDonald, A. The immunobiology of schistosomiasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 499–511 (2002).

Coffee, M. What is schistosomiasis disease? Verywellhealth. https://www.verywellhealth.com/what-is-schistosomiasis-1958983 (2024).

Gray, D. J., Ross, A. G., Li, Y.-S. & McManus, D. P. Diagnosis and management of schistosomiasis. Bmj. 342, d2651 (2011).

Sady, H. et al. Detection of Schistosoma mansoni and Schistosoma haematobium by Real-Time PCR with high resolution melting analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 16085–16103 (2015).

Kane, R. A. et al. A phylogeny based on three mitochondrial genes supports the division of Schistosoma intercalatum into two separate species. Parasitology 127, 131–137 (2003).

Webster, B. L. & Littlewood, D. T. J. Mitochondrial gene order change in Schistosoma (Platyhelminthes: Digenea: Schistosomatidae). Int. J. Parasitol. 42, 313–321 (2012).

Webster, B. L. et al. Occurrence of Schistosoma bovis on Pemba Island, Zanzibar: implications for urogenital schistosomiasis transmission monitoring. Parasitol. 145, 1727–1731 (2018).

Viricel, A. & Rosel, P. E. Evaluating the utility of cox1 for cetacean species identification. Mar. Mammal Sci. 28, 37–62 (2011).

Trobajo, R. et al. The use of partial cox1, rbcL and LSU rDNA sequences for phylogenetics and species identification within the Nitzschia palea species complex (Bacillariophyceae). Eur. J. Phycol. 45, 413–425 (2010).

Molitor, C., Inthavong, B., Sage, L., Geremia, R. A. & Mouhamadou, B. Potentiality of the cox1 gene in the taxonomic resolution of soil fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 302, 76–84 (2010).

Rodrigues, M. S., Morelli, K. A. & Jansen, A. M. Cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 gene as a DNA barcode for discriminating Trypanosoma cruzi DTUs and closely related species. Parasit. & Vectors 10, 1–18 (2017).

Hebert, P. D. N., Cywinska, A., Ball, S. L. & DeWaard, J. R. Biological identifications through DNA barcodes. Proceedings. Biol. Sci. 270, 313–321 (2003).

Lin, X., Stur, E. & Ekrem, T. Exploring Genetic Divergence in a Species-Rich Insect Genus Using 2790 DNA Barcodes. PLoS One 10, e0138993 (2015).

Maki, A. A., Hajissa, K. & Ali, G. A. Prevalence and intensity of urinary schistosomiasis among selected people in Tulus area, South Darfur State, Sudan. Int. J. Community Med. Public Heal. 8, 4221 (2021).

Hajissa, K. et al. Prevalence of schistosomiasis and associated risk factors among school children in Um-Asher Area, Khartoum. Sudan. BMC Res. Notes 11, 779 (2018).

Salah, E. & Elmadhoun, W. Urinary schistosomiasis in gedarif: An endemic new focus in Eastern Sudan. Sudan J. Med. Sci. 9, 163–167 (2015).

Wilson, R. A. Schistosomiasis then and now: What has changed in the last 100 years?. Parasitology 147, 507–515 (2020).

Babiker, A., Fenwick, A., Daffalla, A. A. & Amin, M. A. Focality and seasonality of schistosoma mansoni transmission in the Gezira Irrigated Area, Sudan. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 88, 57–63 (1985).

Babiker, S. M., Blankespoor, H. D., Wassila, M., Fenwick, A. & Daffalla, A. A. Transmission of schistosoma haematobium in North Gezira Sudan. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 88, 65–73 (1985).

Abou-Zeid, A. H., Abkar, T. A. & Mohamed, R. O. Schistosomiasis infection among primary school students in a war zone, Southern Kordofan State, Sudan: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pub. Heal. 13, 1–8 (2013).

Ahmed, A. A., Afifi, A. A. & Adam, I. High prevalence of schistosoma haematobium infection in Gereida Camp, in southern Darfur Sudan. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 103, 741–743 (2009).

Deribe, K. et al. High prevalence of urinary schistosomiasis in two communities in South Darfur: Implication for interventions. Parasit. Vectors 4, 14 (2011).

Ismail, H. A. H. A. et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical manifestations of schistosomiasis among school children in the White Nile River basin. Sudan. Parasit. & Vectors 7, 1–11 (2014).

Elzain, I. A., SulimanAbdalla, H. & Elzaki, S. G. Identification of COX1 gene in urinary schistosomiasis among school children at Al-Fasher town Northern Darfur- Sudan. Sudan Med. Lab. J. 10, 9–16 (2022).

OCHA. OCHA Sudan: North Darfur State Profile. ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/sudan/ocha-sudan-north-darfur-state-profile-march-2023 (2023).

Kranz, O., Sachs, A. & Lang, S. Assessment of environmental changes induced by internally displaced person (IDP) camps in the Darfur region, Sudan, based on multitemporal MODIS data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 36, 190–210 (2015).

CDC. About schistosomiasis. https://www.cdc.gov/schistosomiasis/about/index.html (2024).

Quan, J.-H. et al. Genetic Diversity of Schistosoma haematobium Eggs Isolated from Human Urine in Sudan. Korean J. Parasitol. 53, 271–277 (2015).

Webster, B. L. et al. Genetic diversity within Schistosoma haematobium: DNA barcoding reveals two distinct groups. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6, e1882 (2012).

Sady, H. et al. New insights into the genetic diversity of Schistosoma mansoni and S. haematobiumin Yemen. Parasit Vectors. 8, 544 (2015).

Bandelt, H. J., Forster, P. & Röhl, A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 37–48 (1999).

Eltayeb, N. M., Mukhtar, M. M. & Mohamed, A. B. Epidemiology of schistosomiasis in Gezira area Central Sudan and analysis of cytokine profiles. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 6, 119–125 (2013).

Osman, R. et al. Prevalence of Schistosoma haematobium among School Children in Al-Lamab Bahar Abiad Area, Khartoum State, Sudan 2017: A cross sectional study. EC Microbiol. 14, 454–459 (2018).

El-Khoby, T. et al. The epidemiology of schistosomiasis in Egypt: summary findings in nine governorates. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 62, 88–99 (2000).

Soliman, A. A. et al. Water associated diseases amongst children in IDPs camps and their relation to family economics status: case study of Abushock IDPs Camp, North Darfur State. Sudan. Int. J. Res. Granthaalayah 5, 214–227 (2017).

Braun-Munzinger, R. A. Quantitative egg counts in schistosomiasis surveys. Parasitol. Today 2, 82–83 (1986).

Tulu, B., Taye, S. & Amsalu, E. Prevalence and its associated risk factors of intestinal parasitic infections among Yadot primary school children of South Eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res. Notes 7, 1–7 (2014).

Webster, B. L., Rollinson, D., Stothard, J. R. & Huyse, T. Rapid diagnostic multiplex PCR (RD-PCR) to discriminate Schistosoma haematobium and S. bovis. J. Helminthol. 84, 107–114 (2010).

Idris, A. B. et al. Identification of functional tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter variants associated with Helicobacter pylori infection in the Sudanese population: Computational approach. World J. Gastroenterol. 28, 242–262 (2022).

Thompson, J. D., Higgins, D. G. & Gibson, T. J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucl. Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 (1994).

Talavera, G. & Castresana, J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst. Biol. 56, 564–577 (2007).

Rozas, J. et al. DnaSP 6: DNA sequence polymorphism analysis of large data sets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 3299–3302 (2017).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 3022–3027 (2021).

Saitou, N. & Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 (1987).

Acknowledgements

The authors express gratitude to the participants and their guardians who took part in the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ABI and IAE conceived the idea and HSA and MAH supervised the project. Samples were collected and laboratory analyzed by IAE, , NMA, and MAH. Molecular analysis was conducted by SGE and IAE. Bioinformatics analysis was performed by ABI, AAK, and IAE. ABI, AAK, and IAE wrote the manuscript. ABI, AAK, and SY revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Federal Ministry of Health and the National Schistosomiasis Control Program (NSCP) in Sudan. Additionally, the study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medical Laboratory Sciences at Omdurman Islamic University. Informed consent was obtained from the participants and their parents or legal guardians after they were informed about the importance and objectives of the study. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Throughout the study, participants were not exposed to any danger.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elzain, I.A., Idris, A.B., Karim, A.A. et al. Analysis of DNA cox1 barcoding revealed novel haplotype in Schistosoma haematobium isolated from Western Sudan. Sci Rep 15, 2062 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85986-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85986-0