Abstract

When underground tunnels in coal mines traverse geological structurally abnormal zones (faults, collapse columns, fractured zones, etc.), excavation-induced unloading leads to instability and failure of the engineering rock mass. Rock masses in fractured zones are in elastic, plastic, and post-peak stress states, and the process of excavation through these zones essentially involves unloading under full stress paths. To explore the mechanical response of sandstone under different stress levels, based on the investigation of possible stress paths, a systematic study is conducted on various unloading paths, including elastic-axial compression with unloading of confining pressure, elastic-constant principal stress with unloading of confining pressure, plastic-axial compression with unloading of confining pressure, plastic-constant principal stress with unloading of confining pressure, plastic-constant axial D1 displacement with unloading of confining pressure, plastic-equal proportional unloading of axial and confining pressures, and post-peak-synchronous unloading of axial and confining pressures. Characteristics of full stress-strain curves under seven unloading paths are obtained. The deformation patterns caused by unloading are analyzed, and the relationship between unloading paths and strain increments is investigated. Results show that, as the degree of unloading increases, the unloading deformation modulus ( E ) in the elastic stress state exhibits a trend of initial increase, then stabilization, followed by decrease, while in the plastic stress state, E gradually decreases. Both elastic and plastic states show an increasing trend in Poisson’s ratio (µ). The normalized plastic shear strain γp/γpmax and dilation angle (ψ) conform to a single exponential function, and there is a negative correlation between initial confining pressure and dilation angle. These findings support the enrichment and development of unloading rock mechanics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

When underground coal mine roadway passes through abnormal areas of geological structure (fault, collapse column, crushing zone, etc.), excavation induces unloading instability and failure of engineering rock mass, leading to frequent disasters. As shown in Fig. 1, the rock mass in the fracture zone is in three stress states1: elastic, plastic and post-peak, corresponding to the original consolidated normal rock mass, fissure lithitization zone and fracture zone. The process of excavation through the fracture zone is essentially unloading under the full stress path. Therefore, exploring and studying the mechanical response of surrounding rock unloading under the full stress path can comprehensively and accurately grasp the rock feedback under different stress levels, which has important theoretical significance and practical value for the stability control of surrounding rock in the geological anomaly area.

The research of rock unloading mechanics is developed gradually from the loading rock mechanics. At the early stage of the study, Wu2 et al. believed that the rock unloading path had a greater impact on deformation and a lesser impact on strength. With the deepening of the research, Li3 et al. found that the unloading path had a significant impact on rock strength characteristics and deformation characteristics. Jager4 proposed for the first time in 1966 that there was a certain relationship between rock mechanical properties and stress paths, but due to the lack of experimental conditions, no in-depth study was conducted. In 1971, Swansson5 et al. conducted a rock unloading experiment and found that the unloading path had little impact on rock strength. Swansson’s conclusions were confirmed by Crouch6 in 1972. In terms of unloading mechanical characteristics of engineering rock mass, Ha7 and Li8 et al. proposed unloading rock mass mechanics based on the excavation of the Three Gorges project, and discussed unloading path, anisotropy of rock mass, rock mass size effect, rock mass rheological characteristics, etc. In terms of mechanical properties of indoor rock unloading, stress state, stress path, unloading rate and characteristic samples are mainly considered. In true triaxial unloading study, He9, Li10, Du11,12, Rong13, Yin14, Xu15 et al. conducted single-side unloading experiments on granite, marble, sandstone and cement mortar, analyzed the influence of intermediate principal stress on rock strength and failure characteristics, and explored the rock failure mechanism under the disturbance effect. The effect of unloading rate on rock mechanical properties is analyzed, and the crack evolution law is discussed by acoustic emission time-frequency characteristics. Zhang16, Huang17,18, Lv19, Li20, Xie21, Xu22, Duan23 carried out triaxial experiments of rock under different unloading paths, analyzed the mechanical and strength characteristics, and studied the deformation and expansion parameter evolution law in unloading direction. The elastic modulus E, Poisson’s ratio µ, rupture Angle θ, dilatancy Angle, cohesion force c, internal friction Angle ψ and other parameters were investigated. Scholars such as Zhang24 and Ma25 respectively used the Rock Top multi-field coupling tester and the improved SHPB test system to conduct in-depth discussions on the damage characteristics and energy evolution laws of rocks under stress-seepage coupling and combined static and dynamic stress states. They revealed the energy conversion and release mechanisms of rocks during the unloading process and their impacts on the structural stability of rock masses. The research by Wu26 and Liu27 further focused on the influences of the three-dimensional unloading path and the loading/unloading rates on the strength and deformation characteristics of rocks under the initial condition of high stress. They disclosed the significant reduction in rock strength and the complexity of deformation and failure behaviors during the unloading process. Collectively, these studies have formed a solid foundation for the research on the mechanical response characteristics of sandstone under full-path unloading and provided abundant background information and theoretical support for this study.

The failure mechanism of rock unloading was studied, and the influence of unloading path on residual strength was obtained. In the study of rock unloading mechanical properties, scholars mainly consider the influence of single or two factors in stress path, coal and rock characteristics, mining environment, raw rock stress and unloading rate, and effectively reveal the deformation, strength and fracture characteristics of rock under different unloading paths. However, there are few reports on full path unloading considering the stress characteristics of geological anomaly area. This study aims to explore the mechanical response characteristics of sandstone during full-path unloading under different stress levels, with a particular focus on stability control of surrounding rock in geological anomaly zones (such as faults, collapse columns, fault zones, etc.). By systematically conducting experiments under various unloading paths, we intend to reveal the mechanical response mechanisms of surrounding rock under complex unloading paths, providing new theoretical support and practical guidance for stability control of surrounding rock in geological anomaly zones.

Test overview and unloading path analysis

Sample preparation

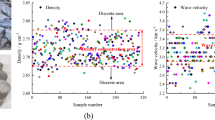

This experiment takes sandstone as the research object, the rock has no natural joints, uniform texture and good integrity. The standard sample was prepared according to the requirements of the method for determining the physical and mechanical properties of coal and rock. The core diameter was 50 mm and the cutting length was 100 mm. The unevenness of the two ends of the sample, the diameter deviation of the upper and lower ends and the axial deviation meet the requirements of the national standard. First of all, the appearance of defects, color difference, poor homogeneity, texture difference of large sample. Uniaxial test: 30 sandstone samples, which have undergone rigorous screening, were selected for the experiment. Triaxial test: 15 sandstone samples were selected for testing under each confining pressure (5 MPa, 10 MPa, 20 MPa, 30 MPa, and 40 MPa) to ensure data reliability. Triaxial unloading test: Based on the results of the uniaxial and triaxial tests, 5 representative sandstone samples (such as those in the elastic, plastic, and post-peak states) were selected for experiments under different unloading paths. As shown in Fig. 2, the ultrasonic wave velocity test system of SonicView-SX for rock samples was adopted to carry out the P-wave test. The P-wave velocity of sandstone was mainly concentrated between 2500 m/s and 2700 m/s, and samples in discrete areas were removed. According to this, the samples in the wave velocity concentration area are selected for single, triaxial and triaxial unloading experiments.

Test instruments and equipment

As shown in Fig. 3, the instrument and equipment for uniaxial, triaxial and triaxial unloading experiments in this time are Rock-600-50 ROCK multi-field coupling rheological experimental instrument designed and developed by Lille University of Technology in France. The composition and appearance of the experimental system are shown in Fig. 3. The experimental system is equipped with three independent loading systems, namely, axial pressure system, confining pressure system and pore water pressure system. The maximum axial stress can reach 500 MPa, the maximum piston stroke is 20 mm, the maximum circumferential pressure can reach 60 MPa, and the maximum pore water pressure can reach 60 MPa. The multi-field coupling of temperature, fluid, chemistry and mechanics of rock, concrete and other materials can be carried out. The sample size is 50 mm (diameter) ×100 mm (height), the control mode of stress, displacement and deformation can be realized, and the basic data such as stress and strain can be collected in real time. The programming port can realize the rock mechanics experiment of complex stress path. The system can measure the stress-strain curve and a series of mechanical parameters such as elastic modulus, Poisson’s ratio and compressive strength of sandstone under different unloading paths.

Rock 600 − 50 triaxial rheometer. (a) Oil source; (b) shaft, confining pressure loading pump; (c) Monitoring and Control panel; D-computer acquisition control system (d-1 host, d-2 display); (e) base lifting pump; F-base (f-1 axial displacement sensor, f-2 circumferential displacement sensor); (g) Power supply; (j) confining chamber return oil pump; k- Rock sample.

Unloading path analysis and experimental scheme determination

Underground hazards, particularly tunnel collapses and mine water inrushes, are often induced by excavation unloading. Therefore, conducting research on the mechanical behavior of rock failure induced by unloading is of significant theoretical and practical importance for preventing underground hazards and ensuring the safety of underground engineering. When analyzing the stress distribution of rock masses near fault zones, we observe a notable gradient change in stress states. Rock masses far from fault zones, being distant from the unloading influence zone, primarily exhibit elastic stress states, displaying mechanical characteristics of intact rock. After tunnel excavation, the surrounding rock undergoes elastic unloading, with tangential stress states presenting various possibilities of loading, constant, and unloading. Hence, the first stress path is summarized as: axial loading, constant, and unloading, with radial unloading. As the rock mass approaches the fault zone, it gradually enters the plastic stage, where internal cracks initiate and the mechanical properties of the rock undergo significant changes. After tunnel excavation, the surrounding rock is in a plastic unloading state, with tangential stress states again presenting various possibilities of loading, constant, and unloading. Thus, the second stress path is summarized as: axial loading, constant, and unloading, with radial unloading. Within the fault zone, the rock mass is entirely in the post-peak stage, with fully developed internal fractures and significantly reduced rock strength. After tunnel excavation, the surrounding rock is in a post-peak unloading state, with tangential stress states presenting the possibility of unloading only. Hence, the third stress path is summarized as: axial unloading and radial unloading.

In order to study the mechanical properties of sandstone under different unloading paths, triaxial experiments with uniaxial and different confining pressures σ3 (5 MPa, 10 MPa, 20 MPa, 30 MPa and 40 MPa) are firstly carried out to determine the peak strength σm. No matter how the unloading experiment scheme is designed, the final unloading point should be greater than the uniaxial compressive strength σd, in order to study the rock failure problem. The reference line of unloading point is shown in Fig. 4. On this basis, rock mechanics experiments under different unloading paths were conducted. Through curve fitting, it was found that confining pressure and principal stress presented a significant linear relationship. The fitting formula was \(\:y=94.32+4.4x\), and the fitting coefficient R2=0.98. The uniaxial compressive strength is lower than the fitting line, indicating that the stress state has a certain effect on the ultimate strength.

Axial and confining pressures each exhibit three stress states: loading, unloading, and stability, as illustrated in Fig. 5. From a permutation perspective, there are nine potential combinations of axial and confining pressure states, including constant axial and confining pressures, unloading of both, unloading of axial while confining remains constant, constant axial with unloading of confining, unloading of axial while loading confining, loading of axial with unloading confining, loading of axial while confining remains constant, constant axial with loading confining, and loading of both. These combinations correspond to four stability states: stable, locally unstable, unstable, and extremely unstable. The stable state, where failure cannot occur, falls outside the scope of this study. Initially, a preliminary discussion and analysis are conducted on the relationship between stress paths and instability states.

Figure 6 shows the in-depth interpretation of the stability. The green area is the stable stress path and the red area is the non-stable stress path. As the color deepens, the instability increases, which is the focus of the stress path research. The scheme of confining pressure loading under axial pressure loading is not considered, the main reason is that the radial stress in excavation or mining is decreasing, the problem of loading “catch-up” is not considered, and the loading “catch-up” is not easy to reach the instability condition. The four conditions that need to be discussed mainly include confining pressure unloading under axial compression loading, constant confining pressure under axial compression loading, constant confining pressure unloading under axial compression unloading and confining pressure unloading under axial compression unloading. The confining pressure under axial compression loading is a conventional triaxial problem, and the stress path is the basis for studying different unloading paths. There are two possibilities for confining pressure unloading under axial compression loading. The first possibility is that the loading speed is less than the unloading speed, and the second possibility is that the loading speed is greater than the unloading speed. Both cases may lead to the instability of coal and rock, but there are certain differences in the instability. Axial pressure invariance can be divided into two cases: principal stress invariance and D1 displacement invariance, in which D1 displacement invariance is a non-supplementary energy scheme. Axial pressure unloading confining pressure unloading mainly discusses eccentricity stress σ1-σ3 constant, confining pressure and axial pressure equal ratio unloading, this scheme is representative in synchronous unloading.

Figure 7a shows all possible paths of the rock. The blue line is axial loading, the lower line is axial unloading, and the green line is confining pressure loading on the right and confining pressure unloading on the left. Continue loading along the hydrostatic pressure line (red line) at the elastic-plastic point M, and the system will maintain stability. The outer side is the strength envelope. When the axial and confining pressure load synchronously (MG, MF) reaches the strength envelope, instability failure will occur. The essence of rock unloading induced failure is the increase of deviatoric stress, among which the unloading paths of MB (increasing axial pressure σ1 unloading confining pressure σ3), MC (constant axial pressure σ1 unloading confining pressure σ3) and MD (axial pressure σ1 confining pressure σ3 unloading synchronously and the axial unloading rate is less than the confining pressure unloading rate) belong to the condition of increasing deviatoric stress. ME (axial unloading rate is equal to confining pressure unloading rate) unloading path belongs to the condition of constant deviator stress. Considering that it should conform to objective reality and have the most promoting effect on failure, the same unloading type is representative.

On the basis of this, three stress paths are determined: ① axial compression unloading confining pressure ② axial compression/axial displacement constant unloading confining pressure ③ axial compression confining pressure equal ratio reduction. Initial stress can be divided into elastic, plastic and post-peak states. Combined with the above discussion and analysis of stress paths, the optimal unloading path is determined. The specific plan is shown in Fig. 7b. In the analysis of the unloading scheme, it is found that not only the unloading path has a certain influence on the mechanical properties of rock, but also the initial damage, unloading rate and control mode have an important influence on the unloading mechanical behavior of rock.

-

a.

(a) Unloading scheme under elastic stress Because the elastic midpoint of sandstone is below uniaxial compressive strength σd, the confining pressure unloading scheme with constant axial pressure is not feasible. In order to explore the influence of unloading in the elastic section on the mechanical behavior of sandstone, the unloading point is set as the uniaxial compressive strength σd, and the sandstone is still in the elastic section.

-

b.

(b) Unloading scheme at the level of plastic stress. Tangential stress may increase, remain unchanged or decrease after unloading of roadway in the plastic zone, and the invariance here also includes D1 displacement unchanged.

-

c.

(c) At the residual strength stage of unloading scheme at the post-peak stress level, the sandstone has been cracked, mainly due to the friction on the fracture surface caused by lateral constraints. The stress path that the tangential stress increases and remains unchanged after the peak cannot be realized, and the unloading of confining pressure will cause rapid attenuation of residual strength. Therefore, the stress path of simultaneous unloading of axial pressure and confining pressure after the peak is objective and feasible. The simultaneous unloading of axial pressure and confining pressure at different stages of residual strength after the peak is discussed.

Study on mechanical properties of sandstone under full unloading path

Analysis of elastic-plastic unloading point

The elastic-plastic unloading point was determined by the curves of deviational-stress (σ1-σ3) -axial strain ε1 under different confining pressures, and the curves of elastic-plastic unloading point and confining pressure σ3 were plotted, as shown in Fig. 8.

With the increase of confining pressure σ3, the elastic unloading point fluctuates between 64 MPa and 73 MPa. Due to the hydrostatic pressure, the compaction stage disappears. In the process of deviatoric stress loading, the curve starts at the elastic section. The whole length of the elastic section curve is basically the same, so the elastic unloading point does not change greatly. Because the pressure value of the elastic unloading point is low, which is less than the uniaxial compressive strength σd, using this point as the unloading point will lead to the absence of the unloading path of sandstone, and can not truly reflect the complexity and objective reality of the stress path. According to the analysis, the elastic-plastic cut-off point corresponding to the confining pressure of 5 MPa is 90.90 MPa. Therefore, taking uniaxial compressive strength σd as the elastic unloading point can ensure the failure of sandstone. The plastic unloading point presents a linear increase trend with the increase of confining pressure σ3, and the linear relation is y = 2.76x + 89.77 (R2 = 0.98). The main reason is that with the increase of confining pressure σ3, the plastic stage keeps lengthening, but the position of the elastoplastic cut-off point does not change significantly, resulting in the plastic midpoint constantly moving upward and the plastic unloading point showing an increasing trend.

Variation law of stress-strain curves of sandstone under different unloading paths

Analysis of stress-strain curves of elastic unloading sandstone

Figure 10b shows the plastic principal stress constant curve. There is a plateau at the end of the curve of confining pressure 5 MPa, that is, residual stress. For the sake of data aesthetics, all curves are treated with “tail”, and the initial stable point of vertical fall is the residual strength. The asterisk represents the unloading point. As shown in Fig. 9a, after unloading, the growth rate of axial strain ε1 in the early peak period is greater than radial strain ε3, indicating that the dominant effect of axial loading is stronger than that of circumferential unloading. In the peak σm and post-peak stages, the radial strain ε3 develops laterally, indicating that the influence of near rupture and initial post-peak unloading on radial deformation ε3 is stronger than that of axial deformation ε1. With the increase of confining pressure σ3, the axial yield interval decreases and the radial yield platform also decreases. Unloading under low confining pressure is more sensitive to deformation ε, while unloading under high confining pressure has a weak effect on deformation ε. Post-peak residual strength σr is positively correlated with confining pressure σ3.

As shown in Fig. 9b, confining pressure σ3 has a significant influence on the pre-peak stress-strain curve slope. The slope of the deviatoric stress σ1-σ3 axial strain ε1 curve increases with the increase of confining pressure σ3. After unloading, the sandstone begins to yield when it reaches the ultimate stress level. Regardless of the size of the initial confining pressure σ3, the deviator stress σ1-σ3 axial strain ε1 curves show a slow oblique and vertical fall after the peak, indicating that the initial fracture is slow and stable, and the cracks are quickly through in the later period. The deviational-stress σ1-σ3 radial strain ε3 curve shows a long “slip” after the peak, and the growth rate of radial strain ε3 in this process is significantly greater than that of axial strain ε1, indicating that unloading contributes to the development of lateral deformation. Initial confining pressure σ3 has little influence on the unloading failure process of principal strain-invariant elastic low (uniaxial compressive strength σc). The slope of unloading failure curve is basically the same, and the value of residual strength σr is similar. With the increase of confining pressure σ3, the total axial strain gradually decreases, and the deformation in the post-peak slow failure stage is similar. This difference is mainly due to the radial binding action in the loading stage.

Analysis of stress-strain curve of sandstone under plastic unloading

As shown in Fig. 10a, since the sandstone is already in the plastic zone, the plastic characteristics continue to intensify after the initial unloading, reaching the peak stress σm in a short period of time. With the increase of confining pressure σ3, the post-peak stress-strain curve changes from slow flexible failure to ductile brittleness failure, and the radial deformation ε3 changes significantly, and the instantaneous post-peak drop indicates that the radial deformation ε3 induces sudden global failure.

In Fig. 10b, the principal stress σ1 is influenced by both the deviatoric stress σ1-σ3 and the confining pressure σ3. When the confining pressure σ3 is in a state of unloading, to maintain this equilibrium, the deviatoric stress σ1-σ3 compensates for the decreased confining pressure σ3, keeping the principal stress σ1 constant. Upon the initiation of unloading, as the confining pressure σ3 increases, the rate of entering the yield state gradually decreases, demonstrating the impact of confining pressure σ3 on strength. The axial strain ε1 curve of deviatoric stress σ1-σ3 exhibits a yield-tensile plateau after peak, where a stable concave post-peak axial deformation ε1 suddenly increases, followed by a vertical drop, indicating significant brittle failure characteristics. The radial strain ε3 of deviatoric stress σ1-σ3 shows lateral expansion. At low to medium confining pressures (≤ 20 MPa), horizontal expansion initiates immediately at the unloading point. At high confining pressures σ3 (≥ 30 MPa), rapid yield occurs initially at the unloading point, with a sudden increase in curve slope. Failure occurs soon after reaching the yield point, and the curve drops at a certain angle, indicating less prominent brittle characteristics.

Figure 10c depicts a non-energy-supplementing stress path with constant axial displacement D1 and unloading of confining pressure σ3, primarily utilizing the elastic energy stored within the sandstone to induce failure. At low to medium confining pressures (σ3 ≤ 20 MPa), failure occurs immediately upon initial unloading, with the post-peak curve exhibiting a stepped decline, characterized by primary stable failure followed by secondary brittle failure. The step width correlates with the confining pressure, while the residual strength σr remains similar. At high confining pressures (σ3 ≥ 30 MPa), initial unloading intensifies plasticity, leading to a stepped decline upon reaching peak stress σm with shorter horizontal step widths and higher residual strength σr. Radial strain ε3 displays notable oblique tensile characteristics, with gradual post-peak failure and instantaneous drop upon the residual strength σr reaching a certain value.

As shown in Fig. 10d, during the unloading process with constant deviatoric stress σ1-σ3, the radial deformation ε3 exhibits horizontal expansion, while the axial deformation ε1 remains largely unchanged, with a sudden increase in axial deformation ε1 at the moment of failure. With increasing confining pressure σ3, the abruptness of axial strain ε1 gradually diminishes, showing lateral extension, albeit to a lesser degree than radial deformation ε3, indicating that failure is radially dominated. The residual strength σr positively correlates with confining pressure σ3. The post-peak radial deformation ε3 curves reveal that as confining pressure σ3 increases, the post-peak radial deformation ε3 transitions from arcuate to vertical dropout, suggesting a shift from plastic to brittle failure. The lengths of the horizontal platforms in post-peak radial deformation vary, posing significant challenges in predicting and forecasting failure.

Stress-strain curve analysis of post-peak sandstone synchronous unloading

As shown in Fig. 11, when a stable residual strength σr is formed after sandstone enters the peak, both axial pressure σ1 and confining pressure σ3 are unloaded simultaneously. Under high confining pressure (σ3 ≥ 30 MPa), the deviatorially stressed σ1-σ3 axial strain ε1 curve shows rebound characteristics, that is, the axial deformation ε1 gradually decreases, and the radial strain ε3 curve shows a nearly vertical drop rule, indicating that the radial unloading guiding effect is not significant, and the axial unloading rate is mainly greater than the radial unloading rate. At low and medium confining pressures (σ3 ≤ 20 MPa), the deviational-stress σ1-σ3 axial strain ε1 curve is significantly different from that at high confining pressures, and the strain ε shows an increasing trend after unloading, and secondary failure occurs in the unloading process. The radial strain ε3 curve of deviational stress σ1-σ3 shows that the radial deformation ε3 presents a slow growth trend with the increase of unloading capacity, and does not change after reaching a certain value.

Analysis of deformation change rules caused by unloading

During the unloading experiment, the confining pressure σ3 is gradually removed after the unloading point, and the deformation of sandstone changes essentially from the unloading. The variation characteristics of strain ε during the unloading process are discussed. From initial unloading to residual strength σr, the unloading stress path with the same confining pressure is selected for comparative analysis, and the strain characteristics from the unloading starting point to the peak stage are discussed. Due to the complex unloading paths, the same initial confining pressure (20 MPa) is selected for each unloading path for analysis. As shown in Fig. 12, axial strain ε1, radial strain ε3 and confining pressure σ3 of each unloading path have similar overall trends, but their variation rules are obviously different. Figure 12 (a) and (b) show unloading under elastic stress. As shown in Fig. 12a, in scheme I, before confining pressure σ3 is greater than 6.67 MPa, axial strain ε1 plays a dominant role, mainly because axial loading rate is greater than confining pressure unloading rate, and axial strain ε1 is greater than radial strain ε3. When the confining pressure σ3 is less than 6.67 MPa, the radial strain changes and values increase rapidly, exceeding the axial strain change rate. In this case, the radial strain plays a dominant role of ε3, and the unloading effect is remarkable. When the confining pressure σ3 is greater than 12 MPa, the bulk strain εv is basically unchanged; when the confining pressure σ3 is less than 12 MPa, the bulk strain εv is in an expanded state; when the confining pressure σ3 is less than 6.67 MPa, the bulk strain εv is greater than the radial strain ε3. As shown in Fig. 12b, axial strain ε1 and its growth rate increase with the increase of unloading quantity ∆σ3, and the change rate of axial strain reaches the maximum in the early stage of failure. The overall variation law of radial strain is the same as that of axial strain. Different from conventional loading, the variation quantity and rate of radial strain are larger than axial strain, resulting in the initial negative volume strain εv, and the sandstone has been in the expansion state at the initial unloading stage. Due to the leading effect of radial strain ε3, the volume strain εv and radial strain ε3 have the same variation law, and the volume strain εv is less than the radial strain ε3 in the whole unloading process.

Figure 12c–f show the unloading under plastic stress. As shown in Fig. 12c, axial strain ε1 gradually increases with the increase of ∆σ3 unloading amount, and a sudden increase occurs at the moment of rupture. The values of axial strain ε1 and radial strain ε3 are basically consistent, and the volume strain εv coincides with radial strain ε3. The volume strain εv is always in an expansion state, indicating that the regulation effect of axial loading confining pressure unloading on deformation is similar. The confining pressure σ3 at the unloading failure point is 16.60 MPa. As shown in Fig. 12d, axial strain ε1 shows a gradual increasing trend, but its value is smaller than radial strain ε3, indicating that unloading plays a leading role. When the confining pressure σ3 reaches 18.68 MPa, the radial strain ε3 is equal to the volume strain εv, the radial strain ε3 is greater than the volume strain εv at the early stage of unloading, and the radial strain ε3 is less than the volume strain εv at the late stage of unloading. The volume expansion effect is significant, and the confining pressure σ3 at the unloading failure point is 13.19 MPa. As shown in Fig. 12e, when confining pressure σ3 is greater than 10 MPa, axial strain ε1 basically remains unchanged. When the confining pressure σ3 is less than 10 MPa, the axial strain ε1 shows a gradual increasing trend, and the axial strain rate reaches the maximum near the failure. In the unloading process, the radial deformation ε3 plays a dominant role, and the radial strain ε3 shows a gradually increasing trend and the changing rate is faster and faster. The bulk strain εv is between the axial strain ε1 and the radial strain ε3, and the changing trend is consistent with the radial strain ε3. The confining pressure σ3 at the unloading failure point is 7.49 MPa. As shown in Fig. 12f, radial strain ε3 is larger than axial strain ε1 on the whole, indicating that radial strain ε1 plays a dominant role under the same unloading condition. The volume strain εv gradually increases with the increase of unloading quantity ∆σ, and the difference between the volume strain εv and radial strain ε3 becomes larger and larger, resulting in more and more significant expansion characteristics of sandstone. The confining pressure σ3 at the unloading failure point is 12.66 MPa.

Figure 12g shows post-peak stress unloading. The axial strain ε1, radial strain ε3 and volumetric strain εv all increase with the unloading amount ∆σ increasing. The secondary failure occurs when the confining pressure σ3 reaches 9.45 MPa, and then the axial strain ε1, radial strain ε3 and volumetric strain εv all increase linearly during the unloading process. The values and variation trends of radial strain ε3 and volumetric strain εv are basically consistent. The starting point of the volume strain εv is in the expansion state and the volume increases with the unloading quantity ∆σ. The order of significant degree of influence of unloading on strain is: axial loading confining pressure unloading < axial constant confining pressure unloading < axial confining pressure equispecific unloading.

Figure 13 shows the law of strain increment change under different unloading paths, and the number in the horizontal coordinate represents the unloading stress path, in the same sequence as Table 1. Regardless of the unloading path, the strain is present as follows: volume strain increment ≥ radial strain increment ≥ axial strain increment. In scheme III and Scheme VII, axial strain increment, radial strain increment and volume strain increment are basically equal, indicating that the unloading direction plays a leading role in the failure, and the sandstone constantly expands during the unloading process.

The above research takes strain increment as the starting point to discuss the influence of unloading on deformation law, and there is a certain relationship between unloading amount and deformation amount. The incremental ratio of strain confining pressure proposed by scholar28 is introduced. This parameter can well reflect the degree of influence of confining pressure unloading on deformation. The larger the absolute value is, the more sensitive the unloading confining pressure is to the deformation in this direction. It is defined as the ratio of unloading quantity and strain increment from unloading start point to unloading end point, as shown in Formula (1) :

Among them:\(\Delta {\dot {\varepsilon }_1}\), \(\Delta {\dot {\varepsilon }_3}\), \(\Delta {\dot {\varepsilon }_{\text{v}}}\) represents axial strain increment, radial strain increment and volume strain increment.

Table 1 shows the increment ratio of strain confining pressure in different unloading paths when the initial confining pressure is 20 MPa, and the stress path when the confining pressure drops to 0 MPa is when the axial confining pressure is discharged synchronously after the peak. The overall law of strain confining pressure increment ratio is shown in Formula (2).

Because the unloading quantity ∆σ3 is the same, the strain confining pressure increment ratio is consistent with the strain increment. The order of confining pressure strain increment ratio under different unloading paths is axial < radial < volume, indicating that the sensitivity of strain variation in unloading direction (radial) is greater than that of axial strain during unloading, and the volume expansion effect is more significant.

The confining pressure strain increment ratios vary in different directions for different unloading paths. Here, seven unloading paths are discussed. In the path of unloading confining pressure with constant elastic principal stress, the relatively small axial confining pressure strain increment ratio is due to the absence of axial loading, resulting in small axial strain and correspondingly small confining pressure strain increment ratio. Similarly, in the paths of unloading confining pressure with constant plastic principal stress and unloading both axial pressure and confining pressure proportionally in plasticity, the axial confining pressure strain increment ratio is also small. However, plastic unloading points have greater control over axial deformation than elastic unloading points, leading to a smaller axial strain increment ratio in the elastic path compared to the plastic path with constant principal stress. In the path of unloading confining pressure with constant plastic D1 displacement, the axial confining pressure strain increment ratio is approximately 0%·MPa⁻¹, primarily because the axial deformation remains essentially unchanged, resulting in no axial confining pressure strain increment. The relatively large axial confining pressure strain increment ratio in the path of unloading confining pressure with elastic axial compression is mainly due to the axial stress loading rate exceeding the confining pressure unloading rate, with the axial stress dominating the deformation field evolution. The main reason for the higher axial confining pressure strain increment ratio in the path of unloading confining pressure with plastic axial compression compared to the elastic path is the influence of the unloading point.

The plastic path of unloading confining pressure with axial compression exhibits the highest radial confining pressure strain increment ratio, indicating the highest sensitivity to unloading and the greatest impact on radial deformation. The radial confining pressure strain increment ratios are also relatively high in the elastic path of unloading confining pressure with axial compression and the plastic path of unloading confining pressure with constant principal stress. The radial confining pressure strain increment ratios are equal in the elastic path of unloading confining pressure with constant principal stress and the plastic path of unloading both axial pressure and confining pressure proportionally, suggesting similar control effects on radial strain despite different stress levels and paths. The radial confining pressure strain increment ratio is relatively small in the plastic path of unloading confining pressure with constant D1 displacement, mainly due to axial deformation control leading to weakened radial deformation and a smaller change in radial deformation caused by unloading. The radial confining pressure strain increment ratio is also small in the post-peak path of synchronous unloading of axial pressure and confining pressure, where the axial unloading rate exceeds the radial unloading rate, resulting in significant axial rebound and constrained radial expansion. The volumetric confining pressure strain increment remains basically unchanged, indicating that the rate of dilatancy change is consistent regardless of the unloading path under various stress states.

Based on the above analysis, the variation of confining pressure strain increment ratios in sandstone under different unloading paths conforms to the deformation laws of rock unloading. This is attributed to the significant influence of the rate of change in unloading stress difference on the deformation rate of sandstone, where unloading directions induce radial deformation development, thereby promoting volumetric expansion. Under the same confining pressure, the axial and radial confining pressure strain increments in the stress path of unloading confining pressure with axial compression are greater than those in other unloading paths, indicating the highest sensitivity to deformation. The confining pressure strain increments corresponding to the stress path of synchronous unloading of axial pressure and confining pressure post-peak are equal and relatively low, reflecting linear unloading characteristics. The volumetric confining pressure strain increments tend to be consistent.

Analysis of variation rules of mechanical parameters of sandstone under different unloading paths

Under the unloading path, mechanical parameters such as deformation modulus E and Poisson’s ratio µ deteriorate continuously. Compared with conventional loading, the unloading mechanical parameters are significantly different, and the inherent mechanical laws and mechanisms are also different. Therefore, based on the characteristics of different unloading stress paths, the influences of elastic, plastic and post-peak stress state unloading on mechanical parameters of sandstone were studied.

Deformation modulus E and Poisson’s ratio µ

Under the three-axis unloading path, there is no unified standard and formula to calculate the corresponding mechanical parameters, especially the significant radial deformation and volume expansion characteristics of unloading, so it is necessary to consider the mechanical parameters under the combined influence of confining pressure and axial pressure. In order to obtain the parameters of each state during unloading, it is assumed that the stress-strain curve during unloading satisfies the generalized Hooke’s law. Since the pseudo-triaxial experiment is carried out, the deformation modulus E and Poisson’s ratio µ are obtained by transforming the formula, as shown in formula (3).

Unloading degree

Different unloading starting point and unloading degree have different influences on mechanical parameters. In order to effectively evaluate the corresponding relationship between unloading degree and mechanical parameters, unloading degree H is introduced to represent the degree of confining pressure unloading, and then the relationship between unloading degree H and deformation modulus E and Poisson’s ratio µ under different unloading paths is explored, as shown in Formula (4).

Where, σ30 is the confining pressure before unloading, MPa;σ3 is the confining pressure corresponding to the unloading failure moment, MPa; The larger the value of H, the higher the unloading degree. When H = 1, it indicates that the confining pressure is unloaded to 0 MPa, which corresponds to post-peak unloading.

Figure 14a shows the variation of deformation modulus (E) with unloading ratio (H) along the path of plastic deformation with axial compression and confining pressure unloading. As the unloading ratio (H) increases, the deformation modulus (E) gradually decreases, and the rate of decrease gradually accelerates with increasing H, reaching a maximum at the point of failure. A higher initial confining pressure (σ3) results in a faster decrease in deformation modulus (E). Under low initial confining pressures (σ3 ≤ 10 MPa), the unloading ratio (H) ranges between 30% and 50%, while under medium to high initial confining pressures (σ3 ≥ 20 MPa), the unloading ratio (H) remains approximately 20%. As the initial confining pressure (σ3) increases, the initial deformation modulus (E) also gradually increases, varying within a certain range before failure without any abrupt changes. Analysis reveals no positive correlation between the decrease in deformation modulus (E) and initial confining pressure (σ3).

Figure 14b illustrates the variation of Poisson’s ratio (µ) with unloading ratio (H) along the same path. Poisson’s ratio (µ) gradually increases with increasing unloading ratio (H), and the rate of increase accelerates, reaching a maximum near failure. At the point of failure, Poisson’s ratio (µ) experiences a sudden increase. There is a positive correlation between initial confining pressure (σ3) and Poisson’s ratio (µ), with values within a reasonable range. As the unloading ratio (H) increases, Poisson’s ratio (µ) exceeds 0.5 (Poisson’s ratio has an extreme value of 0.5 by definition), indicating that it is no longer within the elastic range and includes irrecoverable plastic deformation, particularly large lateral deformation caused by unloading. The fracture patterns of sandstone show multiple longitudinal tensile cracks, and unloading exacerbates radial deformation. Therefore, Poisson’s ratio in this context differs from its conventional meaning, and it is reasonable for the value to exceed 0.5.

Figure 15a shows the curves of deformation modulus E and unloading degree H under different unloading paths. The initial deformation modulus E is different in different unloading paths. When the elastic stress is horizontally unloaded, the deformation modulus E firstly increases and then decreases, and the local deformation modulus E changes linearly, mainly because the elastic unloading point is located in the elastic interval, the unloading process goes through the elastoplastic interval, and the constant deformation modulus corresponds to the elastic modulus. The unloading degree H of confining pressure path under constant elastic principal stress is close to 100%, which means that the sandstone is destroyed after complete unloading, which is consistent with the actual stress path setting. When the plastic stress is horizontally unloaded, the curve shows a decreasing trend, but the deformation modulus E of the confining stress path under constant plastic D1 displacement remains basically unchanged before the fracture, and gradually decreases near the fracture. The variation rule of initial deformation modulus in plastic stage is as follows: Scheme IV > Scheme VI > Scheme III > Scheme V, which reflects the difference of initial unloading stiffness. The unloading degree H varies with different plastic stress paths. The unloading degree H corresponding to the confining pressure unloading by plastic plus axial pressure is 16.62%, the unloading degree H corresponding to the confining pressure unloading by constant plastic principal stress is 33.88%, and the unloading degree H corresponding to the constant plastic axial pressure confining pressure unloading is 36.41%. The unloading degree H corresponding to the confining pressure under constant displacement of plastic D1 is 62.01%. The curve of the post-peak synchronous unloading deformation modulus E is complex. After the initial unloading deformation modulus decreases linearly, a drop occurs, which corresponds to secondary failure. The stiffness of sandstone is constantly weakened, and then the deformation modulus E slows down and increases until the unloading terminal point E is about 0 GPa. The initial deformation modulus E of post-peak synchronous unloading is the lowest. The main reason is that the rock is already in the post-peak state and loses its bearing capacity. The residual strength σr is maintained by the friction between blocks under the confining pressure σ3, so the deformation modulus E of sandstone at this stage is relatively low. In addition to post-peak synchronous unloading, the deformation modulus E at the level of elastic-plastic stress can be regression by using quartic polynomials to obtain the relationship curve between the deformation modulus E and the unloading degree H under the unloading condition of sandstone, as shown in formula (5).

Where, E0 is the deformation modulus corresponding to the initial unloading point, GPa; A, B, C and D are constant quantities dependent on the unloading path, which are obtained by curve fitting. Figure 15b shows the relationship between Poisson’s ratio µ and unloading degree H under different unloading paths. Poisson’s ratio µ tends to be consistent with the increase of unloading degree H, and the initial values vary with different stress paths. Poisson’s ratio µ varies as follows: elastic unloading > plastic unloading > post-peak unloading, among which, Poisson’s ratio in scheme II > Poisson’s ratio in scheme I. Under the confining stress path of elastic axial unloading, the loading velocity is much greater than the unloading velocity, and the sandstone mainly reflects the loading characteristics, so the radial deformation caused by unloading leads to the less obvious increase of Poisson’s ratio µ. The order of Poisson’s ratio µ in the plastic interval was as follows: scheme III > scheme V > Scheme IV > schemeVI, and the values of Poisson’s ratio µ in the last three were similar. Poisson’s ratio µ of simultaneous unloading after peak first linearly increased and then gradually decreased and fluctuated. In addition to post-peak synchronous unloading, Poisson’s ratio can be regression with quartic polynomial to obtain the relationship curve between Poisson’s ratio µ and unloading degree H under unloading condition, as shown in formula (6).

Where, µ0 is the deformation modulus corresponding to the initial unloading point; A, B, C and D are constant quantities dependent on the unloading path, which are obtained by curve fitting. To sum up, although the unloading path is complicated, the unloading deformation modulus E and Poisson’s ratio µ under the same stress state have basically the same change trend. The unloading deformation modulus E under elastic stress state presents a trend of first increasing, then stabilizing and then decreasing, the unloading deformation modulus E under plastic stress state presents a trend of gradual decreasing, and Poisson’s ratio µ both presents an increasing trend. The main difference comes from the initial value. It should be noted that different unloading paths lead to a large gap in unloading degree H, which is of great significance for the stability control of surrounding rock and the prediction and prediction of failure.

Analysis of sandstone expansion characteristics under different unloading paths

According to the deformation and fracture morphology of unloading direction, unloading has obvious dilatancy characteristics. In the study of quantitative dilatancy indicators, the dilatancy stage has entered the plastic zone, and elastic indicators such as volume strain cannot well characterize the plastic process, while dilatancy Angle can better describe the change process of rock inelastic volume. According to Vermeer29, Formula (7) of dilatancy Angle was proposed as follows:

Among them:\(\Delta \varepsilon _{{_{{\text{1}}}}}^{{\text{p}}}\), \(\Delta \varepsilon _{{_{{\text{v}}}}}^{{\text{p}}}\)Are axial plastic strain increment and volumetric plastic strain increment, respectively. Among them\(\Delta \varepsilon _{{_{{\text{v}}}}}^{{\text{p}}}{\text{=}}\Delta \varepsilon _{{_{{\text{1}}}}}^{{\text{p}}}{\text{+2}}\Delta \varepsilon _{{_{3}}}^{{\text{p}}}\),It can be expressed by axial plastic strain increment and radial plastic strain increment, as shown in Eq. (8) :

Scholars have found that there is a functional relationship between dilatancy Angle ψ and confining pressure σ3 and plastic parameters30,31. The plastic shear strain is the difference between axial and radial plastic strain. The dilatancy Angle ψ is adopted to analyze the change of sandstone dilatancy with plastic parameters in the unloading process. The axial elastic strain and radial elastic strain can be obtained according to generalized Hooke’s law. The plastic strain can be obtained by subtracting the elastic strain from the total strain, as shown in formula (9 ~ 13).

In order to analysis the dilatancy Angle under different unloading point bits, the change rule of normalized processing of plastic shear strain, the abscissa for γp/γpmax, starting point is the initial unloading time, the end is the ultimate bearing capacity. Figure 16 shows the relationship between dilatancy Angle of confining stress path relieved by plastic axial compression and normalized plastic shear strain, and analyzes the influence of confining pressure on dilatancy Angle.

As the normalized plastic shear strain increases, the dilation angle (ψ) exhibits an overall trend of rapid growth followed by stable variation. When the normalized plastic shear strain is less than 0.2, the dilation angle (ψ) shows a decelerating growth trend; when it exceeds 0.2, the dilation angle (ψ) remains stable. A normalized plastic shear strain of 0.2 serves as the inflection point for the dilation angle (ψ). Since the unloading point is within the plastic zone, the sandstone exhibits dilatancy characteristics. As the unloading amount increases, the lateral confining force decreases, providing space for lateral deformation and facilitating sample dilatancy, resulting in a rapid increase in the dilation angle (ψ). The dilatancy develops rapidly during the initial stage of unloading, with a sharp increase in dilatancy volume. The dilation angle (ψ) and normalized plastic shear strain satisfy an exponential function. By fitting the curve using the exponential function in Origin software, a correlation coefficient R2 = 0.85 is obtained, indicating that this exponential function can well characterize the relationship between the dilation angle and normalized plastic shear strain, as shown in Eq. (14).

By comparing with the dilatancy Angle (ψ) under different confining pressures in scheme III, it can be found that the larger the initial confining pressure σ3, the smaller the initial dilatancy Angle ψ, and the larger the initial unloading pressure σ3, the stronger the constraint ability and the weaker the dilatancy ability. With the decrease of initial confining pressure σ3, the lateral binding decreases, but the development and penetration ability of new cracks are enhanced, and the dilatancy ability is also enhanced, which results in the increase of dilatation Angle ψ. The stable dilatation Angle showed a positive correlation with the initial dilatation Angle. The corresponding dilatation Angle ψ of 40 MPa, 30 MPa, 20 MPa, 10 MPa and 5 MPa were 9.8°, 12.9°, 18.1°, 20.1° and 25.8°, indicating that the initial confining pressure and dilatation Angle were negatively correlated.

Discussion

This paper systematically analyzes the method for investigating the relationship between stress paths and rock stability, and based on this, conducts triaxial unloading tests under various stress paths. By designing multiple unloading paths, mechanical response data of sandstone under different stress states are obtained and subjected to in-depth analysis and research. The innovativeness of this research method and approach lies in its comprehensive consideration of the influence of stress paths on rock mechanical properties, rather than merely focusing on the mechanical properties of rocks under a single stress state. Previous scholars at home and abroad have revealed mechanical characteristics of rocks during the unloading process, such as changes in deformation modulus, increases in Poisson’s ratio, and other parametric issues. However, the research findings presented in this paper are more in-depth and specific, proposing a single-exponential functional relationship between normalized plastic shear strain and dilation angle, as well as a negative correlation between initial confining pressure and dilation angle. These conclusions have not been explicitly mentioned in previous studies. Nevertheless, to further uncover the intrinsic mechanisms of the rock unloading process, this paper suggests utilizing advanced numerical simulation techniques (such as finite element analysis, discrete element analysis, etc.) to simulate the rock unloading process and validate and compare these simulations with experimental results. This will provide new means and methods for studying rock mechanical properties and promote further development of related theories.

Conclusion

In order to explore the mechanical characteristics of sandstone unloading under elastic, plastic and post-peak stress states, based on the systematic analysis of the relationship between stress path and rock stability, triaxial unloading tests under full stress path were carried out to study the response of unloading path to stress-strain and mechanical parameters of sandstone.

-

(1)

A possible coordinate system is proposed based on the permutation and combination of axial pressure and confining pressure, and the stability levels of different stress paths are analyzed to obtain systematic and comprehensive unloading paths. As the confining pressure increases, the elastic unloading points fluctuate between 64 MPa and 73 MPa, while the plastic unloading points show a linear growth. The drop characteristics and post-peak extension characteristics of the stress-strain curves under different unloading paths are different. For the elastic-axial pressure increase and confining pressure unloading and plastic-unloading curves, obvious ductile flow occurs before brittle drop in the post-peak stage. For the elastic-main stress unchanged and confining pressure unloading and post-peak-simultaneous unloading curves, instantaneous sliding occurs after slow yielding failure, which reflects the influence of the unloading path on the fracture characteristics of sandstone.

-

(2)

During the unloading process, the effect of radial tension is obvious and gradually becomes dominant. The volumetric dilation phenomenon is significant, and the volumetric strain changes synchronously with the radial strain. The change trends of the strain increment and the ratio of strain to confining pressure increment are consistent. The variation law of the confining pressure strain increment ratio of sandstone under different unloading paths conforms to the unloading deformation law of rocks. The confining pressure strain increment ratio shows that the axial confining pressure strain increment is less than the radial confining pressure strain increment, which is less than the volumetric confining pressure strain increment. This indicates that during the unloading process, the sensitivity of strain change in the unloading direction (radial direction) is greater than that of the axial strain, and the volumetric expansion effect is more significant.

-

(3)

Under the same confining pressure, the axial and radial confining pressure strain increments along the stress path of increasing axial pressure while unloading confining pressure are both greater than those of other unloading paths, indicating that this unloading path has the highest sensitivity to deformation. For the stress path of synchronous unloading of axial pressure and confining pressure after the peak, the corresponding confining pressure strain increments are equal and both relatively low, reflecting the linear characteristics of unloading. The volumetric confining pressure strain increments tend to be consistent.

-

(4)

As the degree of unloading increases, the unloading deformation modulus E in the elastic stress state shows a trend of first increasing, then stabilizing, and finally decreasing, while the unloading deformation modulus E in the plastic stress state shows a gradually decreasing trend, and the Poisson’s ratio µ shows an increasing trend in both cases. The normalized plastic shear strain γp/γpmax and the dilatancy angle ψ conform to a single exponential function, and there is a negative correlation between the initial confining pressure and the dilatancy angle.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed in this study can be provided by the authors Gang Liu and Dongwei Wang according to reasonable requirements.

References

Gui, H. Impacts of Different Material Compositions on the Permeability of Fractured Fault Zone in Coal Measures (China University of Mining and Technology, 2017).

Wu, Y. & Li, J. Unloading properties of marble. Rock. Soil. Mech. 5(1), 31–38 (1984).

Li, J. et al. Research Progress of mechanical characteristics and constitutive model of Rock under Unloading Condition. J. Yangtze River Sci. Res. Inst. 34(07), 87–93 (2017).

Jaeger, J. C. Brittle Fracture Of Rocks. The 8th U.S. Symposium on Rock Mechanics (Port City Press, 1966).

Swansson, S. R. & Brown, W. S. An observation of loading path independence of fracture in rock. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstracts. 8(3), 271–281 (1971).

Crouch, S. L. A note on post-failure stress-strain path dependence in norite. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstracts. 9(2), 197–204 (1972).

Ha, Q. Loading rock mechanics and unloading rock mechanics. Chin. J. Geotech. Eng. 20(01), 3–5 (1998).

Li, J. & Wang, L. Study on unloading nonlinear mechanical characteristics of jointed rock mass. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 26(10), 1968–1975 (2007).

He, M. C., Miao, J. L. & Feng, J. L. Rock burst process of limestone and its acoustic emission characteristics under true-triaxial unloading conditions. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 47(2), 286–298 (2010).

Li, X., Du, K. & Li, D. True triaxial strength and failure modes of cubic rock specimens with unloading the minor principal stress. Rock. Mech. Rock. Eng. 48(6), 2185–2196 (2015).

Du, K. Study on the Failure Characteristics of deep rock and the Mechanism of Strainburst under true Triaxial Unloading Condition(China University of Mining and Technology, 2017).

Du, K. et al. Experimental study of Slabbing and Rockburst Induced by true-triaxial unloading and local dynamic disturbance. Cent. South. Univ. 49(9), 3437–3453 (2016).

Rong, H. True Triaxial test Study on Mechanical Properties of deep rock mass in Different Stress Paths (AnHui University of Science and Technology, 2018).

In, G. et al. Effect of loading and unloading rates on mechanical properties and energy char-acteristics of sandstone under true triaxial stress. J. China Coal Soc. 44(02), 454–462 (2019).

Xu, W. et al. Test study on true-triaxial loading and unloading for marble withunloaded single face. J. Southwest. Jiaotong Univ. 54(3), 526–534 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. Analysis of yield functions of marble under different loading and unloading stress paths. Chin. J. Rock Mechan. Eng. 33(12), 2497–2503 (2014).

Huang, R. & Huang, D. Study on deformation characteristics and constitutive model of rock on the condition of unloading. Adv. Earth Sci. 23(05), 441–447 (2008).

Huang, R. & Huang, D. Experimental research on mechanical properties of granites under unloading condition. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 27(11), 2205–2213 (2008).

Lv, Y., Liu, Q. & Hu, Y. Damage deformation characteristics and its strength criterion based on unloading experiments of granites. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 28(10), 2096–2103 (2009).

Li, J. et al. Experimental study of sandstone mechanical properties by unloading triaxial tests. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 29(10), 2034–2041 (2010).

Xu, J. Study on unloading characteristics and rockburst prediction method of deep sandstone in coal mine. Wuhan Univ. (2016).

Duan, S. et al. Experimental study of mechanical properties of staggered zones under loading and unloading conditions of high stresses. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 35(06), 1090–1101 (2016).

Xie, H. Q. & He, C. H. Study of the unloading characteristics of a rock mass using the triaxial test and damage mechanics. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 41(3), 366–366 (2004).

Zhang, P. et al. Research on the influence of different unloading paths on the damage characteristics and energy evolution law of sandstone under the coupling effect of stress and seepage. Rock. Soil. Mech. 45(02), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.16285/j.rsm.2023.0204 (2024).

Ma, Z. et al. Research on the mechanical characteristics and energy evolution law of combined coal and rock masses under different stress states and strain rates. Coal Sci. Technol. 1–13. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.2402.td.20240607.1422.002.html (2024).

Wuxing, W. et al. Strength reduction of initial high-stress Rock pillars under different triaxial unloading paths. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 56(5), 3519–3537 (2023).

Jie, L. et al. Study on failure mechanical behavior of coal in triaxial stress loading and unloading path. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 82(11) (2023).

Qiu, S. et al. Experimental research on mechanical properties of deep buried marble under different unloading rates of confining pressures. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 29(09), 1807–1817 (2010).

Vermeeer, P. A. & De Borst, R. Non-Associated Plasticity for Soils, Concrete and Rock (Delft University of Technology, 1984).

Detournay, E. Elastoplastic model of a deep tunnel for a rock with variable dilatancy. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 19(2), 99–108 (1986).

Alejano, L. R. & Alonso, E. Considerations of the dilatancy angle in rocks and rock masses. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 42(5), 481–507 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Heilongjiang Ground Pressure and Gas Control in Deep Mining Key Laboratory, Heilongjiang University of Science and Technology.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province Grant number YQ2023E039; Basic Scientific Research Operating Expenses of Heilongjiang Provincial Universities and Colleges of China, Grant number 2022-KYYWF-0554; the Scientific and Technological Key Project of “Revealing the List and Taking Command” in Heilongjiang Province, grant number 2021ZX02A03, 2021ZXJ02A04.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Gang Liu and Dongwei Wang wrote the main text of the manuscript and the experimental data processing and summaries, while Yao Zeng ,Shengxuan Wang,Yonglong Zan and Guoqing Wei were the co-authors responsible for collecting relevant information to organize the structure of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, G., Zeng, Y., Wang, D. et al. Study on the mechanical response characteristics of sandstone under elasticity plasticity and full path unloading after peak stress. Sci Rep 15, 1681 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85999-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-85999-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Mechanical response and energy dissipation law of double-fractured sandstone under dynamic load

Scientific Reports (2025)