Abstract

From 2016 to 2019, 128 organic and conventional spring and winter pea fields in Germany were surveyed to determine the effects of cropping history and pedo-climatic conditions on pea root health, the diversity of Fusarium and Didymella communities and their collective effect on pea yield. Roots generally appeared healthy or showed minor disease symptoms despite the frequent occurrence of 4 Didymella and 14 Fusarium species. Soil pH interacted with the occurrence of the Fusarium oxysporum species complex (FOSC) and F. tricinctum that correlated with reduced or increased soil pH values, respectively. While legumes in the cropping history or reduced time between legumes correlated with occurrence of D. pinodella and to a lesser degree with the members of the F. solani species complex (FSSC), the reverse was true at least in organic spring peas for F. redolens. Only in conventional systems increased root infections with F. redolens and the FSSC were linked to root rot incidence whereas yields negatively correlated with the FOSC and positively with F. tricinctum isolation frequencies. Overall, this study shows that pea root rot pathobiome is rather stable and that the damage caused is mostly due to the interaction with environmental conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Peas are an important protein crop as well for human as for animal nutrition well adapted to cool climatic conditions. As leguminous crop, they simultaneously provide important ecological services such as biological N fixation. However, frequently pea production is limited by multiple soil-borne pathogens that cause pre- and postemergence death, wilts and foot and root rots which are collectively referred to as a ‘pea root rot pathogen complex’1.

The diversity and predominance of pathogens in the root rot complex can vary greatly depending on the pedo-climatic conditions, cropping history, geographical location, year and even between years within the same location2,3,4,5,6. Thus, in Germany, surveys from 2005 to 2007 in conventional spring peas7 and 2009–2012 in organic spring peas8 showed that the primary constituents of the pea root rot pathogen complex were the species Didymella pinodella (syns. Phoma medicagins, Phoma pinodella, Peyronellaea pinodella) typically accompanied by a moderate presence of Fusarium redolens, F. avenaceum, and the members of the F. solani (FSSC) and F. oxysporum (FOSC) species complexes. In contrast, in Canada, the pathogen complex is primarily characterized by the dominance of Aphanomyces eutheices and F. avenaceum5, whereas in the USA, F. avenaceum and FOSC are the most frequently reported9. Recent studies in France and the UK identified D. pinodella10 and the FOSC, FSSC and F. redolens11,12 as the predominant species within the pea root rot complex. Understanding the factors that shape the pea root rot complex pathogen community and their influence on yield is essential for effective disease risk assessment and disease management.

While peas are the most widely grown grain legume crop in Germany13, pea production in Germany sharply declined by 75% from 163.610 hectares (ha) in 2001 to about 42.000 ha in 201413. Low and instable yields together with high susceptibility to soil-borne pathogens had been discouraging farmers from growing this crop. With the implementation of the Germany protein crop strategy in 201214 and the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) greening measures in 2015, the trend was reversed and by 2022, pea production was about 107.000 ha. As organic pea production overall has remained relatively stable during the past 20 years15, this increase is primarily due to conventional farmers that are now integrating mostly spring pea into their rotations. Often, these farmers are growing legumes for the first time after more than 10 years, providing a unique opportunity to study the effects of cropping history on pea health. For this, from 2016 to 2019 we conducted yearly surveys on pea root health in conventional and organic peas, to evaluate the impact of farming system (organic versus conventional), pedo-climatic conditions and crop rotation management on root health and root rot pathogens and their influence on pea yield.

The specific objectives of the study were to (1) determine the current root health status and examine the identity and prevalence of root rot pathogens associated with spring and winter peas in Germany, (2) determine the effect of cropping systems on root health as well as the diversity of Fusarium and Didymella communities in pea roots and, (3) relate the changes in pea root health, cropping history and pedo-climatic conditions to the variations in the Fusarium and Didymella communities and pea yield. Additionally, (4) we present findings on the genetic variability of the FOSC and FSSC isolates recovered, and compare results from this study with the outcomes of a parallel survey on faba bean root rot in Germany6, in order to contribute to a better understanding of root health and pathogen dynamics in these two major protein crops.

Results

Environmental and soil conditions of the sampled fields

The 133 organic and conventional pea fields sampled represented a wide range of environments with respect to climatic and soil conditions (Tables 1 and 2). Sowing conditions ranged from very wet (up to 71 mm of rainfall in the 2 weeks preceding sowing) to completely dry, as well as from very cold (with a minimal mean temperature of −4.9 °C two weeks before sowing) to warm conditions (a maximum mean of 13.8 °C before sowing). Similarly, the conditions during plant emergence varied greatly, with up to 72 mm of rainfall two weeks after sowing to entirely dry periods (Table 1). For spring pea, the driest conditions were recorded in 2018, where a field received as little as 21 mm of rainfall from sowing to sampling. Wettest conditions were observed in 2016, with a spring pea field receiving a 533 mm of rainfall over the same period. In winter peas, the driest conditions were recorded 2016/2017, with a field receiving only 163 mm of rain during the growing season, while the wettest conditions occurred in 2018/2019, where a field received 1001 mm of rainfall from sowing to sampling (Table 1).

Soil types ranged from light sandy soil (up to 86% sand) to heavy clay soils (up to 50% clay) with pH levels ranging from 5.6 to 7.5 and a high variation in soil organic matter (SOM) content from only 1.1% to up to 5.1% (Table 1). The sampled fields grouped into 3 clusters based on their similarities in soil pH, sand, silt, clay and organic matter content. The first two dimensions of the Hierarchical Clustering on Principal Components (HCPC) analysis accounted for 77% of the variance in the dataset, 57% in the first dimension that separated sand dominated fields (Cluster I) from silty-clay soils in Clusters II and III (Table 2). The second dimension explained an additional 20% of the variance and showed the strongest association with SOM content.

Cluster I comprised 15 organic and 19 conventional spring pea fields and 2 conventional winter pea fields with sandy soils and a pH of around 6.4. The mean SOM content in Cluster I was 1.8% in organic fields and approximately 2.5% in conventional fields. The largest Cluster II comprised silty-clay soils with mean pH of 6.5 and 2.6% SOM, represented by 39 spring pea fields, 4 of organic and 21 out of the 29 organic winter pea fields. Cluster III soils were again silty-clay but with higher pH (about 7.1) and mean SOM contents (3.0 for spring pea and 3.5 for winter pea fields). Four of the 26 spring pea fields and 8 of the 11 winter pea fields were organic (Table 2).

Crop rotations

The proportion of legumes in the five years preceding pea sampling varied considerably depending on system and pea type. In 14 out of the 23 organic spring and 27 out of the 29 organic winter pea fields legumes had been cultivated in the five years preceding our sampling (Fig. 1). In contrast, out of the 81 conventional fields sampled, 59 had not been cropped to any legume in that period.

Legumes in organic and conventional crop rotations. (A) Spring pea and (B) Winter pea: On the left, the number of fields with legumes grown in the past five years prior to sampling; on the right, the number of fields and the time since legumes were last cultivated before sampling. Data for more than 11 years were not available.

In half (7) organic spring pea fields with legumes in the past five years, grain legumes had been cultivated once (four times pea and two times faba bean and once, pea and faba bean). Clover and alfalfa were grown on 13 fields either in one out of 5 years (8 fields), or for two (3 fields) or three (2 fields) consecutive years. All except one organic farms grew cereals, either in one (3 fields), two (2 fields), three (4 fields), four (9 fields) or five (4 fields) years during the preceding 5-years. In addition, eight out of the 23 organic spring pea fields grew this crop in mixture with oats (Avena sativa; 5 fields), false flax (Camelina sativa; 2 fields) or spring wheat (Triticum aestivum; 1 field) (Supplementary Table S1).

Grain legumes were present once (9 times), twice (5 times) and trice (once) during the five years before organic winter peas. Out of these 15 cases, 11 fields had been planted with pea, 9 once and 2 twice; faba beans were grown in 4 fields once. Additionally, clover and alfalfa had been grown on 17 fields, either for one (10 fields) or two years (7 fields). Cereals had been grown in all 29 fields: 9 times twice and 9 times trice, 10 times for four years, and once in all five years before winter peas. All organic winter peas were grown in mixtures with triticale (19 fields), rye (9 fields) of winter wheat (1 field) (Supplementary Table S1).

Among the 20 conventional spring pea fields with legumes in the previous five years, 11 had been cultivated with pea once and two twice and one with faba bean. In one of the winter pea fields two years grass-clover and in one faba beans had been grown. Five farmers also had clover and alfalfa based mixtures in the rotations. The conventional 5-year rotation plans included two (14 fields), three (29 fields), four (23 fields) or five (5 fields) years of cereals. Only two conventional fields had not at all been sown to cereals (Fig. 1). Conventional peas were predominantly cultivated as pure stand (73 fields), whereas three spring pea fields were grown in mixture either with barley (2 fields) or false flax (1 field). Among the 5 conventional winter pea fields, two farmers grew the crop in mixture with triticale (Supplementary Table S1).

Field level root rot incidence and root health status

Overall, a total of 2560 pea roots were assessed for the severity of root rot symptoms. In spring pea fields (total number of roots assessed, n = 1945), root heath status ranged from completely healthy (disease severity rating DSR = 1; absence of any symptoms) to moderately diseased (DSR = 6.1 in organic fields, n = 441 and; DSR = 6.2 in conventional fields, n = 1504). Mean DSR in organic peas (3.0) was significantly higher (P = 0.04) than in conventional peas (2.2). Clearly visible symptoms of field level root rot with mean DSR > 3 were recorded in 7 (30%) out of 23 organic and 15 (20%) with no statistically significant year or systems effects (Table 3). Root rot was equally severe in the 15 organic spring pea pure stands and the 8 organic species mixtures (Supplementary Table S2).

Winter peas appeared mostly healthy with overall mean DSR of 2.0 and 1.5 in organic (N = 29; n = 515) and conventional (N = 5; n = 100) fields, respectively. Moderate field level root rot was recorded only on two organic winter pea fields (7%) sampled in 2017 with mean DSR of 4.3 and 5.5 (Table 3).

Fusarium and Didymella species associated with pea roots

A total of 5097 isolates representing 4 Didymella and 14 Fusarium spp. were recovered from 2651 roots used for the fungal isolations over the 4-yr study period (Supplementary Table S1). With 56% of all roots infected, D. pinodella was the most frequently recovered species, followed by F. redolens, F. avenaceum and the members of the FOSC with approximately 27% infected roots. Members of the FSSC (18% roots infected) and the species F. tricinctum (14%) were the next most frequently isolated. Fusarium equiseti and F. culmorum were found with overall root infection rates of about 5%. Also found but represented with few isolates only were the species F. acuminatum, F. graminearum, F. sporotrichioides, F. crookwellense, F. torulosum, F. flocciferum, F. sambucinum, D. pinodes, D. lethalis and D. eupyrena (syn. Juxtiphoma eupyrena).

Isolation frequencies varied significantly depending on the fungal species (P < 0.0001), pea type (spring vs. winter, P = 0.002) and year (P = 0.005) with significant interactions between fungal species isolation frequencies and pea type, growing system and year (P < 0.0001). Organic spring pea roots were infected more frequently with D. pinodella (P = 0.005) and members of the FOSC (P = 0.003) compared to conventional spring peas (Fig. 2). The higher overall isolation frequencies of D. pinodella in organic systems compared to conventional were mainly due to higher frequencies of this species in 2016 and 2017 in organic fields compared to the conventional (ca. 70% infected roots in organic systems vs. ca. 40% infected roots in conventional systems). In 2018 and 2019, the species showed similar frequencies in both management systems (ca. 30 and 60% roots infected in 2018 and 2019, respectively). The FOSC members were consistently 10–20% more frequent in roots collected from organic (35–51%) compared to conventional systems (28–35%), but these differences were not statistically significant (Supplementary Table S3). In contrast to FOSC and D. pinodella, organic spring pea roots were less frequently infected with F. tricinctum (P = 0.0006) and F. culmorum (P = 0.006) compared to conventional although at overall low frequencies. Isolation frequencies of F. redolens (P = 0.08), the FSSC (P = 0.6), F. avenaceum (P = 0.01) and F. equiseti (P = 0.01) varied somewhat among years with no statistically significant effect of management system (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S3). None of the isolation frequencies of the individual fungal species was affected by species mixtures in organic spring peas (Supplementary Table S2).

Effect of management system on isolation frequency (%) of the top eight fungal species recovered from spring and winter pea roots. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) between organic and conventional fields for each fungal species separately (Sidak-adjusted pairwise least significant means comparisons). The horizontal line in the boxplot shows the median value, the bottom and tops of the box the 25th and 75th percentiles and the vertical lines the minimum and maximum values, outliers as single points. Mean values are marked with triangles.

On average, 89% (72–98%) of the organic winter pea roots were infected with D. pinodella. Infections with Fusarium spp. were considerably lower (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S3) with F. avenaceum most frequently recovered (27% overall mean isolation frequencies), followed by F. redolens and the FSSC (9%). The remaining Fusarium species occurred overall at frequencies of 6% and lower (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S3). Conventional winter pea roots followed a similar trend with D. pinodella (58%) predominant, followed by F. avenaceum (22%) and F. redolens (19%) (these data were not included in any statistical analysis due to very small sample size (N = 5)) (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S3).

Phylogeny

Based on the single-locus phylogeny the 30 FSSC isolates belonged to three different lineages, all nested within clade 3 (Fig. 3). The majority of the isolates (28 out of 30) closely matched Fusarium vanettenii (syn. F. pisi, F. solani f. sp. pisi). In addition, one isolate was placed within the F. solani sensu stricto lineage, and one isolate matched F. breviconum.

The maximum likelihood (RAxML) tree constructed using partial tef1 alpha gene sequences from 30 isolates of the Fusarium solani species complex (FSSC) examined in this study highlighted in bold and red (i.e. FOEP-this study). FOSC isolates from parallel previous study6 recovered from faba bean were also included in the analysis were also included in the analysis (FOEP isolates). Epi- and ex-type strains are marked with a ‘T’53,69. The scale bar represents 0.04 expected changes per site, and the tree is rooted with F. thapsinum (H05557S1 DCPA).

The 17 FOSC isolates were nested within six clades (Fig. 4). The largest group consisting of 6 isolates (clade 8 in this study) showed the closest genetic relationship to the previously classified F. oxysporum forma specialis (f. sp.) pisi (PG108; MIAE 08036) and f. sp. conglutinans (NRRL 36364). Two isolates were associated with clade 7, described as the F. fabacearum and F. gossypinum in Lombard et al. (2019) which were not entirely resolved in our single-locus analysis. In addition, individual isolates were nested within clades 5 and 13 corresponding to the previously described F. cugenangense and F. odoratissimum (Lombard et al., 2019).

The maximum likelihood (RAxML) tree constructed based on partial tef1 alpha gene sequences from isolates of the Fusarium oxysporumspecies complex (FOSC) used in this study, highlighted in bold and red (e.g., FOEP-this study). The FOSC isolates from parallel previous study6 recovered from faba bean were also included in the analysis and are indicated in red with host in brackets. Along with the FOSC clades are given proposed species names in the FOSC along with epi- and ex-type strains (in bold) suggested by Lombard et al.16. The scale bar represents 0.005 expected changes per site, and the tree is rooted with F. udum (CBS 177.31).

The relationship between pathogen occurrence, root health, yield and environmental factors

Cool temperatures in early spring favored F. redolens in organic winter peas and both, organic and conventional spring peas were favored by cool temperatures in early spring. In addition, in spring peas, the species was overall reduced in wetter years, and only in organic systems if more grain legumes occurred in the rotation (Table 4).

The members of the FOSC in organic and conventional spring peas were negatively correlated with pH and in conventional systems with cluster III soils while cluster I soils favored their occurrence. In contrast, in organic winter peas overall warm temperatures and wet conditions correlated with FOSC occurrence. The isolation frequencies of the FSSC members correlated positively only with the frequency of grain legumes in the rotation under conventional conditions. No significant effects of environmental conditions in organic systems could be found (Table 4).

Warmer temperatures during the season affected F. avenaceum in organic spring peas negatively while in conventional spring peas, it was favored by higher humidity. In organic winter peas this species correlated negatively with the clay content of the soil (Table 4).

In conventional spring peas, F. tricinctum was positively correlated with warm temperatures before sowing, cereals in the rotation and the soil pH and sand contents. The positive association with pH was also observed in winter peas. In organic spring peas, it only correlated with wetter conditions during the season. In spring peas F. equiseti was not affected by environmental conditions while in organic winter peas the species correlated positively with warmer temperatures during the season (Table 4).

The main factor correlating with increased D. pinodella in all growing systems was the cropping history. Both, in conventional spring peas and organic winter peas, the longer the break since the last grain legumes were grown the lower the frequency of D. pinodella isolations. In organic spring peas, instead, the species correlated with the years since conversion to organic which in fact also is an indicator of legume frequency in the system. In organic spring peas, an overall warm season enhanced the frequency while good water supply after sowing was associated with reduced infections. In contrast, in winter peas warm conditions with good water supply around sowing reduced D. pinodella root infection rates (Table 4).

Except for F. redolens and the FSSC complex in the conventional spring peas none of the fungal species identified correlated with field level root rot incidence, i.e. disease severity > 3 (Table 4).

Water availability, cropping history and soil properties correlated with organic spring pea yields in various ways but not for conventional spring peas or organic winter peas (Table 4). Only conventional yields appeared to be weakly affected by the frequencies of root associated Fusarium and Didymella spp. but in part with contradictory trends. Correlations were negative with the FOSC (r = −0.34) complex but positive with F. tricinctum (r = 0.34) (Table 4).

Discussion

Pea roots appeared mostly healthy irrespective of the highly variable pedo-climatic conditions and rotational histories of the 128 organic and conventional spring and winter pea fields sampled. Despite this, 14 Fusarium spp. and 4 Didymella spp. were isolated, including D. lethalis and F. flocciferumwhich were identified for the first time in Germany17,18. Didymella pinodella was the predominant species, followed by F. redolens, F. avenaceum and members of the Fusarium oxysporum species complex (FOSC). These findings agree with previous reports from Germany which also found similar spectra of these potentially pathogenic fungi in symptomatic pea roots7,19 and predominantly asymptomatic faba bean6 roots. Winter pea roots in particular appeared healthy. These cultivars typically have a higher tannin content than spring peas19. This may have contributed to the higher resistance and absence of symptom expression which makes them particularly attractive to organic farmers. In contrast, most winter pea varieties are not attractive to conventional farmers due to their indeterminate growth which requires a support crop and poses technical challenges in planting and harvesting including the low economic value of the crop. Consequently, all winter pea farmers included in this study cultivated this crop in mixtures and they were predominantly organic.

Phylogenetic analysis inferred from the tef1gene sequences placed the 17 FOSC isolates in 6 clades, all previously associated with pea and/or faba bean roots. This high phylogenetic diversity observed has been reported in other studies6,11,12,20 and likely is a result of the polyphyletic origin of different F. oxysporumformae speciales21. Additional analyses are needed to determine the role of these isolates in the pea root rot complex. This is particularly important as the FOSC members also includes endophytes with non-pathogenic characteristics. Also, the characteristics of the different FOSC isolates found in the same host plant but belong to different genetic lineages are not well understood. These isolates/lineages may potentially show high variation in aggressiveness or specific cultivar-pathogen interactions.

In contrast, the FSSC isolates were phylogenetically less diverse than FOSC, with most belonging to the Fusarium vanettenii lineage (syn. F. pisi, F. solani f. sp. pisi). One isolate was placed within the F. solani sensu stricto lineage, and one isolate matched F. breviconum. These results are consistent with previous studies which also reported similar phylogenetic diversity including the broader host range for the single FSSC isolates recovered from roots of several legumes including pea, faba bean, subterranean clover, white clover and winter vetch6,11,12,22.

Higher levels of root rot symptoms in conventional spring pea fields correlated with higher isolation frequencies of F. redolens and the FSSC. In contrast, in organic systems field level root rot incidence was recorded in approximately 30% of the fields but could not be linked to any of the major fungal species isolated. Under organic conditions, the lack of correlation between root health parameters (i.e. visible damage) and fungal species specific isolation frequencies as well as between these parameters and yield, could be due to the stronger impacts of soil conditions as inputs are severely limited. In addition, factors not evaluated in this study such as weed infestation, insect populations and other physicochemical soil conditions can overshadow the direct influence of root-health related factors on yields and infection rates of potentially pathogenic and other root-associated fungi.

While management system (organic vs. conventional) or pea type (spring vs. winter) did not affect the spectrum of fungal species isolated, differences in isolation frequencies were present especially for D. pinodella. This can be explained mostly by the overall lower frequency of legumes in the conventional cropping histories as repeated grain legume cropping has been shown to result in increased D. pinodella abundance in soil and roots of pea and faba bean2,6. The predominance of D. pinodella over Fusarium spp. in organic winter pea roots also agrees with previous results19. The high root infection rates by D. pinodella in organic winter peas compared to organic spring peas further suggest an ecological advantage of this species in cooler and moist environments compared to Fusarium spp. Infection success of D. pinodella is especially high directly after sowing and quickly declines within a few days especially in the presence of beneficial microorganisms such as F. equiseti23. It is also possible that the generally higher tannin content in winter peas along with variations in root exudation played a role in modulating the plant-associated microbiome and suppressing Fusarium infections.

In both, organic and conventional systems FOSC isolation frequencies negatively correlated with soil pH a fact that has been repeatedly reported6,24,25,26. As organic fields were primarily characterized by sand dominated low SOM soils (Cluster I) and lower pH levels while in conventional systems, silty soils (Cluster II) predominated (Table 2), it is likely that the abundance of FOSC in organically grown spring peas is at least partly due to the soil characteristics. Lower SOM and soil pH levels typically are characteristic of sandy soils. Such soils mostly have reduced water retention capacity resulting in lower yields of both peas (as observed in this study) and faba beans6 as yield of both crops highly depend on soil water availability. With yields already impeded in the sandy low SOM fields, the impact of FOSC on yield may not have been distinguishable any more in contrast to its impacts in the better conventional soils.

The cereal dominated conventional field histories resulted in higher isolation frequencies of F. tricintum and likely contributed to increased frequencies of F. culmorum in conventional spring pea roots compared to organic. Fusarium tricintum also correlated positively with soil pH and negatively with sand. The two species are typical members of the Fusarium complex associated with ear, stem and root rots in various small-grain cereals and maize and are responsible for pre-harvest mycotoxin contamination27,28. However, these species are usually of minor importance in the pea root rot complex and their roles are not fully understood. Thus, conventional spring pea yields actually correlated positively with the abundance of F. tricintum in roots, a relationship we also found in faba beans6. In contrast, F. tricinctum has been to be reported potentially important pathogen of soybeans29. Fusarium culmorum is often implicated as a weakly to moderately aggressive pea root rot pathogen30,31.

The wide spread occurrence of F. redolens, F. avenaceum, F. equiseti and the members of the FSSC in spring peas in both management systems over a range of soil and environmental conditions indicates their good adaptation to diverse pedo-climatic conditions. With the exception of F. equiseti which has been shown to contribute to disease reduction in various crops32,33 including pea root rot23, all of the remaining Fusarium species are a major part of the pea root rot complex across different climatic and soil conditions, including Canada, France, USA and Germany.

Consistent with recent results in spring faba bean6, abundance of F. redolens in spring pea roots correlated with cold conditions early in the season during sowing and plant emergence followed by a dry growing season. This highlights the importance of abiotic plant stressors in enhancing the colonization process by this potential pathogen, likely contributing to the higher abundance of this species in conventional pea roots with clear symptoms of root rot. Interestingly, in organic spring peas F. redolens correlated negatively with frequency of grain legumes in the rotation. This is in contrast to recent reports from Canada2 and Germany6 where increased abundance of this fungus positively correlated with grain legume-intensive rotations. These differences could be due to a combination of factors specific to this study, including the influence of prior legume crops and/or other soil and agronomic practices. These factors may have shaped the pea root rot complex community potentially favoring accumulation of more specialized fungal species like D. pinodella at the expense of F. redolens. It is also possible that specific soil suppressiveness against F. redolens that depends on the regular cropping of grain legume species played a role. A more in-depth microbial community analysis could help elucidate the interaction of cropping system and the broader microbial community structure in influencing the symptom expression and the presence or suppression of single pea pathogens. We also cannot exclude the possibility of the isolation procedure contributing to these results. The choice of agar medium and the inherent challenges of culture-based methods to recover specific fungal species have been reported previously5,34,35. To overcome these limitations DNA-based detection techniques like quantitative real-time (q)PCR assays or next generation sequencing (NGS) could be employed. However, qPCR assays targeting all major fungal species identified in this study have become available only after the start of this research34,36. Additionally, the application of NGS was beyond the scope and focus of this study, which was primarily focused on examining the occurrence of Fusarium and Didymella species, their genetic diversity and interactions with cropping systems and yield.

The positive correlations of F. avenaceum with cold seasons in organic spring peas and, wet seasons in conventional spring peas, suggest that abiotic plant stress enhances the colonization process by F. avenaceum. While this species plays a significant role in the pea root rot complex in Canada and the USA5,9 it is mostly an opportunistic pathogen in Germany where it has also been shown to be favored by cool and water logged conditions over winter6,19.

In organic systems, the FSSC frequencies were not affected by any of the pedo-climatic or rotational history characteristics tested while under conventional conditions it correlated with root rot incidence and a higher frequency of grain legumes in the rotation. This fungal complex is known to be of importance in pea root health3,9,12,37 and we have no explanation why it did not play a prominent role under organic conditions despite equal isolation frequencies in both systems.

Taken together, in all years, several potential pathogens could be found in predominantly asymptomatic pea roots, showing that the Fusarium and Didymella spp. associated with peas often reside in the roots without causing substantial damage6,38,39,40. The occurrence of such asymptomatic infections is likely the result41 of a balanced antagonism between the plants defense mechanisms and the virulence factors of the pathogens. Given that biological interactions are never neutral, we recently showed, for example, that asymptomatic infections with D. pinodella can reduce wheat biomass39 and can also cause severe pre-emergence death and post-emergence root rot in peas10. Asymptomatic root infections by D. pinodella and F. redolens have also been linked to reduced faba bean yields6, suggesting higher investment of the faba bean to maintain a balanced antagonism with these fungi. The negative correlation of conventional pea yields with members of the FOSC in this study suggests similar underlying interactions. Furthermore, environmental factors and the timing of root infections are important in maintaining balanced antagonism and influence disease development, including the expression of visible disease symptoms6. Fusarium and Didymella spp. are often opportunistic pathogens that can cause damage especially well if pant stress occurs in early crop growth stages, whereas pea can tolerate well root infections in later growth stages23 if environmental conditions are not too extreme (e.g. prolonged drought or rainy period). Furthermore, beneficial fungi in the roots may also have played a role in the lack of clear disease symptoms and the weak association between root rot severity and the major fungal species identified in this study e.g. beneficial F. equiseti23 and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi42,43 which have the ability to manipulate plant defense and/or pathogen infection sites.

Thus, pedo-climatic factors appeared to be the main drivers for the occurrence of the most common fungal species with clear differences between spring and winter grown peas. The most obvious interactions occurred with soil pH which interacted with the occurrence of certain fungi, especially the FOSC members and F. tricinctum that correlated with reduced or increased soil pH values, respectively. The interactions with cropping history varied depending on the fungal species. Higher frequency of legumes in rotation or shorter intervals between legumes was associated with the presence of D. pinodella and to a lesser extent the FSSC. However, for F. redolens in organic spring peas, the opposite trend was observed. This suggests some specific microbial interactions depending on the species are involved. Only in conventional systems, root health and yields were affected by specific fungal species. Root rot incidence was associated with increased infection rates of F. redolens and members of the FSSC complex. In contrast, yields were negatively correlated with the frequencies of FOSC complex members and positively with F. tricinctum.

Materials and methods

Surveys, sampling and disease assessments

Sample collection, fieldwork and laboratory analyses followed the procedures outlined in Šišić et al. (2022)6 which were used in parallel survey of faba beans. Between 2016 and 2019, 99 spring and 34 winter pea fields were sampled across Germany (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 1). Among the spring pea fields, 23 were managed organically and 76 conventionally. Most winter pea fields were managed organically (29 fields) and only 5 conventionally. Historical cropping data were collected directly from farmers. These included number of times (in years) that fields were planted to various leguminous species (pea, faba bean, lentil, lupin, soybean, clovers and alfalfa, vetch and the unspecified group of ‘other grain’ or ‘small seeded legumes’) and to cereals (aggregated across all cereal types) for 5 and 11 years preceding the sampling. Spring peas in 8 organic and 3 conventional fields as well as all organic winter peas and two conventional winter pea crops were grown in mixtures with cereals or false flax (Camelina sativa) (Supplementary Table S1).

Soil samples were collected in spring from a 0–20 cm depth by taking 20 cores from two randomly selected 5 m2 plots in each field, located 10 to 20 m apart. The samples were analyzed for soil pH, sand, silt, clay and soil organic matter content according to the DIN 7025:2018 − 0344 protocol. Meteorological data were obtained from the nearest weather stations which were always located within 10 km of the sampled fields.

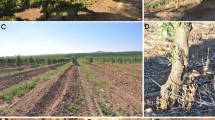

Root sampling was performed by uprooting 36 to 40 pea plants from each field during full flowering from the same two 5 m² areas used for soil sampling. Half of the roots were immediately washed and assessed for root rot severity using a scoring system ranging from 1 to 9, where a score of 1 represented healthy plants and a score of 9 indicated dying plants7 (Fig. 6). The other half of the roots was sent to the University of Kassel and preserved at −18 °C until fungal isolations were performed. At pea maturity, fields were visited again and grain yields were determined by hand harvesting 2.5 m² next to the 5 m² areas used for soil and root sampling (as the initial 5 m² area had been disturbed). Gain yield was adjusted to 86% dry matter before statistical analyses.

Fungal isolations, morphological and molecular characterization of isolates

Fungal isolations targeted species within the Fusarium and Didymella genera. Roots were first thoroughly washed in distilled water, surface sterilized using 3% sodium hypochlorite for 10 s and rinsed well in distilled water and placed on filter paper under a laminar flow hood for about 1 h to dry. From each root, three approximately 1-cm-long segments were cut out from the upper, middle and lower portions and placed on Coons media45 for incubation at 20˚C under a 12-hour light/dark cycle and black-light blue light. After an incubation period of 1 to 2 weeks, fungal colonies that developed from the root segments were sub-cultured separately into Petri dishes containing half-strength potato dextrose agar (19 g/l Difco PDA and 10 g/l agar). Pure cultures were generated either through hyphal tipping for Fusarium species or by transferring individual pycnidia for Didymella species. The obtained isolates were identified to the species level based on their cultural characteristics and the morphology of conidiogenous cells46,47.

Molecular confirmation of 124 Fusarium and 25 Didymella isolates representing 14 different fungal species was carried out by sequencing the translation-elongation factor 1 alpha (tef1) locus for Fusarium spp. and the β tubulin (tub2) for Didymella spp. (Supplementary Table S4)48,49. Genomic DNA was extracted from pure cultures grown on half-strength PDA (Fusarium spp.) and on Coons medium (Didymella spp.), following the method described by Doyle and Doyle (1987)50. The tef1gene was amplified using primers EF1 (5′ ATG GGT AAG GARG ACA AGA C 3′) and EF2 (5′ GGA RGT ACC AGT SAT CAT GTT 3′)48, and the tub2region was amplified with primers Btub2Fd (5′ GTB CAC CTY CAR ACC GGY CAR TG 3′) and Btub4Rd (5′ CCR GAY TGR CCR AAR ACR AAG TTG TC3′)49. The amplified products were visualized through electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel and then purified using the DNA Clean & Concentrator kit (Zymo Research, Freiburg, Germany) according to the manufacturers guidelines. Sanger sequencing was conducted in both directions by Macrogen Europe Laboratories (Amsterdam, Netherlands). The raw sequence data were assembled and any errors were manually corrected using SeqMan Lasergene software (DNAStar, Madison, WI, U.S.A.). Generated sequences were then used as queries for the Fusarium-ID v. 1.051 and NCBI52 databases to verify the taxonomic identity of the isolates.

In addition, single-locus phylogenetic analyses were conducted using tef1 gene sequences generated for 30 isolates of the Fusarium solani species complex (FSSC) and 17 isolates of the Fusarium oxysporum species complex (FOSC). Reference sequences (Supplementary Table S5 and Supplementary Table S6) for these analyses were sourced from previously published phylogenetic studies on the FSSC and the FOSC16,21,53 complexes. Representative isolates from the most recent studies on pea and faba bean root rots conducted in the UK, France and Germany6,11,12 were also included. The final datasets consisted of 126 tef1 sequences of the FSSC and 210 of the FOSC (Supplementary Table S5 and Supplementary Table S6). Sequence alignments were generated using MAFFT v.754 and were further adjusted manually with MEGA v655. A Maximum-Likelihood (ML) analysis was conducted with RAxML-VI-HPC v. 7.0.3, employing non-parametric bootstrapping with 1000 replicates via the Cipres portal56. For outgroup purposes, F. udum (CBS 177.31) and F. thapsinum (H05-557 S-1 DCPA) were used (Supplementary Table S5 and Supplementary Table S6). The resulting phylogenetic trees were visualized and edited in FigTree (version 1.4.4; http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/) and Adobe Illustrator CS5.157.

Data analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted in R58. Isolation frequencies (% colonized roots) were calculated by dividing the number of roots containing a species by the total number of roots processed. Additionally, if the mean disease severity score within a given field was greater than 3, the field was considered to be seriously affected, a condition that was assessed as the incidence on the field level6. The data collected from conventional winter pea fields are presented, however, these data were not included in statistical analyses due to the limited sample size (only 5 fields).

Root rot severity data were analyzed with non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests with the pea type (spring vs winter pea), management system (organic vs conventional), sowing pattern (pure vs mixed stands for spring pea only) and year as main factors. Kruskal multiple comparison tests were performed in case of significant effects. Benjamini and Hochberg59 stepwise adjustment controlled false discovery rates (FDR) and reduced type I errors. For the isolation frequency data, rare species (< 2% of total root colonization rates) were excluded from the analysis. Generalized linear mixed models with management system, pea type (spring vs winter pea), sowing pattern (pure vs mixed stands for organic spring pea only) and sampling year as factors were employed on proportional data with a binomial response and logit link function60. Fields were modeled as random effects, accounting for nested sampling replicates within each field. Model goodness was assessed using Pearson chi-square residual tests, normality checks, and outlier detection (package ‘DHARMa’61. Significant main effects were evaluated with ANOVA and Tukey’s correction for post hoc comparisons (P< 0.05) (package ‘lsmeans’62).

To explore the relationship between the frequencies of the eight most commonly isolated fungal species and yield, root rot incidence on the field level, cropping histories and pedo-climatic factors, Pearson correlation analysis was employed (package ‘Hmisc’63. Only statistically significant (p < 0.05) correlation coefficients of ≥ ± 0.30 are reported. In addition, to provide an overview of the soil types for the sampled fields, we employed hierarchical clustering on principal components (HCPC) using the ‘FactoMineR’ package64. This approach involves grouping of the fields into clusters based on similarities in soil abiotic properties namely, sand, silt, clay, organic matter content and pH. The R packages ‘maps’65, ‘raster’66 and ‘ggplot2’67 were used to show the coordinates of surveyed fields on a map of Germany. The ggplot2 visualizations were further enhanced with R package ‘ggsn’68 which was used to add scale bars and north arrows to the map.

Data availability

All data are included within the article and its supplementary materials. The complete raw data set generated during this study is available in Supplementary Table S1. Data can also be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Change history

18 July 2025

This article has been updated to amend the license information.

References

Wille, L., Messmer, M. M., Studer, B. & Hohmann, P. Insights to plant–microbe interactions provide opportunities to improve resistance breeding against root diseases in grain legumes. Plant. Cell. Environ. 42, 20–40 (2019).

Bainard, L. D. et al. Increasing the frequency of pulses in crop rotations reduces soil fungal diversity and increases the proportion of fungal pathotrophs in a semiarid agroecosystem. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 240, 206–214 (2017).

Esmaeili Taheri, A., Chatterton, S., Foroud, N. A., Gossen, B. D. & McLaren, D. L. Identification and community dynamics of fungi associated with root, crown, and foot rot of field pea in western Canada. Eur. J. Plant. Pathol. 147, 489–500 (2017).

Niu, Y. et al. Intensified pulse rotations buildup pea rhizosphere pathogens in cereal and pulse based cropping systems. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1909 (2018).

Chatterton, S. et al. Importance and causal agents of root rot on field pea and lentil on the Canadian prairies, 2014–2017. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 41, 98–114 (2019).

Šišić, A., Baćanović-Šišić, J., Schmidt, H. & Finckh, M. R. Farming system effects on root rot pathogen complex and yield of faba bean (Vicia faba) in Germany. Front. Plant Sci. 13 (2022).

Pflughöft, O., Merker, C., von Tiedemann, A. & Schäfer, B. C. Zur verbreitung und bedeutung von pilzkrankheiten in körnerfuttererbsen (Pisum sativum L.) in Deutschland. Gesunde Pflanzen. 64, 39–48 (2012).

Wilbois, K. P. et al. Steigerung Der Wertschöpfung Ökologisch Angebauter Marktfrüchte Durch Optimierung Des Managements Der Bodenfruchtbarkeit. Gesamtprojekt Abschlussbericht. 1–567 (2013). www.orgprints.org/28973.

Chittem, K. et al. Identification and characterization of Fusarium spp. associated with root rots of field pea in North Dakota. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 143, 641–649 (2015).

Šišić, A., Baćanović-Šišić, J., Gamba, F. M. & Finckh, M. R. Didymella pinodella: An important pea root rot pathogen in France to watch out for? J. Fungi 10, 44 (2024).

Jenkins, S. Examining Identity, Phylogeny and Pathogenicity Factors in Fusarium Species Affecting Pea (University of Warwick, 2018).

Gibert, S. et al. Identification, pathogenicity and community dynamics of fungi and oomycetes associated with pea root rot in northern France. Plant. Pathol. 71, 1550–1569 (2022).

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. FAOSTAT Statistical Database. Crop statistics (2024). http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QC.

BMEL. Plant production - Protein Crop Strategy. Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft (2012). https://www.bmel.de/EN/topics/farming/plant-production/protein-crop-strategy.html.

BMEL. BMEL-Statistik. Bundesministerium für Ernährung und Landwirtschaft (2024). http://www.bmel-statistik.de.

Lombard, L., Sandoval-Denis, M., Lamprecht, S. C. & Crous, P. W. Epitypification of Fusarium oxysporum – clearing the taxonomic chaos. Persoonia 43, 1–47 (2019).

Šišić, A., Baćanović-Šišić, J., Schmidt, H. & Finckh, M. R. First report of Didymella lethalis associated with roots of pea, subterranean clover and winter vetch in Germany, Switzerland and Italy. Plant Dis. 102, 2642 (2018).

Šišić, A., Baćanović-Šišić, J., Schmidt, H. & Finckh, M. R. First Report of Fusarium flocciferum causing root rot of pea (Pisum sativum) and faba bean (Vicia faba) in Germany. Plant Dis. 104, 283–283 (2020).

Baćanović-Šišić, J., Šišić, A., Schmidt, J. H. & Finckh, M. R. Identification and characterization of pathogens associated with root rot of winter peas grown under organic management in Germany. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 151, 745–755 (2018).

Maryani, N. et al. Phylogeny and genetic diversity of the banana Fusarium wilt pathogen fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense in the Indonesian centre of origin. Stud. Mycol. 92, 155–194 (2019).

O’Donnell, K. et al. A two-locus DNA sequence database for typing plant and human pathogens within the Fusarium oxysporum species complex. Fungal Genet. Biol. 46, 936–948 (2009).

Šišić, A. et al. The ‘forma specialis’ issue in Fusarium: A case study in Fusarium solani f. sp. pisi. Sci. Rep. 8, 1252 (2018).

Šišić, A., Baćanović, J. & Finckh, M. R. Endophytic Fusarium equiseti stimulates plant growth and reduces root rot disease of pea (Pisum sativum L.) caused by Fusarium avenaceum and Peyronellaea pinodella. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 148, 271–282 (2017).

Saeedi, S. & Jamali, S. Molecular characterization and distribution of Fusarium isolates from uncultivated soils and chickpea plants in Iran with special reference to Fusarium redolens. J. Plant. Pathol. 103, 167–183 (2021).

Orr, R. & Nelson, P. N. Impacts of soil abiotic attributes on Fusarium wilt, focusing on bananas. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 132, 20–33 (2018).

Singh, D., Kumar, A., Singh, A. K. & Tripathi, H. S. Induced resistance in field pea against rust disease through various chemicals/micronutrients and their impact on growth and yield. Plant. Pathol. J. 12, 36–49 (2013).

Bateman, G. L., Gutteridge, R. J., Gherbawy, Y., Thomsett, M. A. & Nicholson, P. Infection of stem bases and grains of winter wheat by Fusarium culmorum and F. graminearum and effects of tillage method and maize-stalk residues. Plant. Pathol. 56, 604–615 (2007).

Bernhoft, A., Torp, M., Clasen, P. E., Løes, A. K. & Kristoffersen, A. B. Influence of agronomic and climatic factors on fusarium infestation and mycotoxin contamination of cereals in Norway. Food Addit. Contam. Part. Chem. Anal. Control Expo Risk Assess. 29, 1129–1140 (2012).

Chitrampalam, P. & Nelson, B. D. Jr. Effect of Fusarium tricinctum on growth of soybean and a molecular-based method of identification. Plant. Health Progress 15, 124–129 (2014).

Persson, L., Bødker, L. & Larsson-Wikström, M. Prevalence and pathogenicity of foot and root rot pathogens of pea in southern Scandinavia. Plant Dis. 81, 171–174 (1997).

Safarieskandari, S., Chatterton, S. & Hall, L. M. Pathogenicity and host range of Fusarium species associated with pea root rot in Alberta, Canada. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 43, 162–171 (2020).

Horinouchi, H., Muslim, A., Suzuki, T. & Hyakumachi, M. Fusarium equiseti GF191 as an effective biocontrol agent against Fusarium crown and root rot of tomato in rock wool systems. Crop Prot. 26, 1514–1523 (2007).

Macia-Vicente, J. G., Rosso, L. C., Ciancio, A., Jansson, H. B. & Lopez-Llorca, L. V. Colonisation of barley roots by endophytic Fusarium equiseti and Pochonia chlamydosporia: Effects on plant growth and disease. Ann. Appl. Biol. 155, 391–401 (2009).

Zitnick-Anderson, K., Simons, K. & Pasche, J. S. Detection and qPCR quantification of seven Fusarium species associated with the root rot complex in field pea. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 40, 261–271 (2018).

Armstrong-Cho, C., Sivachandra Kumar, N. T., Kaur, R. & Banniza, S. The chickpea root rot complex in Saskatchewan, Canada- detection of emerging pathogens and their relative pathogenicity. Front. Plant Sci. 14, 1117788 (2023).

Šišić, A., Oberhänsli, T., Baćanović-Šišić, J., Hohmann, P. & Finckh, M. R. A novel real time PCR method for the detection and quantification of Didymella pinodella in aymptomatic and asymptomatic plant hosts. J. Fungi 8, 41 (2022).

Kraft, J. M. Fusarium root rot. In Compendium of pea diseases (ed Hagedorn, D. J.) 13–14 (APS Press, 1984).

Rodriguez, R. J., White, J. F. Jr, Arnold, A. E. & Redman, R. S. Fungal endophytes: Diversity and functional roles. New Phytol. 182, 314–330 (2009).

Šišić, A., Oberhänsli, T., Baćanović-Šišić, J., Hohmann, P. & Finckh, M. R. A novel real time PCR method for the detection and quantification of Didymella pinodella in symptomatic and asymptomatic plant hosts. J. Fungi. 8, 41 (2022).

Šišić, A. et al. Roots of symptom-free leguminous cover crop and living mulch species harbor diverse Fusarium communities that show highly variable aggressiveness on pea (Pisum sativum). PLoS ONE. 13, e0191969 (2018).

Schulz, B. & Boyle, C. The endophytic continuum. Mycol. Res. 109, 661–686 (2005).

Hu, J. L. et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal inoculation enhances suppression of cucumber Fusarium wilt in greenhouse soils. Pedosphere 20, 586–593 (2010).

Saldajeno, M. G. B. & Hyakumachi, M. The plant growth-promoting fungus Fusarium equiseti and the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Glomus mosseae stimulate plant growth and reduce severity of anthracnose and damping-off diseases in cucumber (Cucumis sativus) seedlings. Ann. Appl. Biol. 159, 28–40 (2011).

DIN 7025:2018-03. General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories (DIN EN ISO/IEC 17025:2018-03). 65 (2018). https://doi.org/10.31030/2731745.

Coons, G. H. Factors involved in the growth and the pycnidium formation of Plenodomus fuscomaculans. J. Agric. Res. 5, 713–769 (1916).

Boerema, G. H., Gruyter, J., Noordeloos, M. E. & Hamers, M. E. C. Phoma Identification Manual: Differentiation of Specific and Infra-Specific Taxa in Culture (CABI Publishing, 2004).

Leslie, J. F. & Summerell, B. A. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual (Blackwell Publishing, 2006).

O’Donnell, K., Cigelnik, E. & Nirenberg, H. I. Molecular systematics and phylogeography of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex. Mycologia 90, 465 (1998).

Woudenberg, J. H. C., Aveskamp, M. M., de Gruyter, J., Spiers, A. G. & Crous, P. W. Multiple Didymella teleomorphs are linked to the Phoma clematidina morphotype. Persoonia 22, 56 (2009).

Doyle, J. J. & Doyle, J. L. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochem. Bull. 19, 11–15 (1987).

Torres-Cruz, T. J. et al. FUSARIUM-ID v.3.0: An updated, downloadable resource for Fusarium species identification. Plant Dis. 106, 1610–1616 (2022).

Madden, T. The BLAST sequence analysis tool. In The NCBI Handbook [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Center for Biotechnology Information (US) 2002- (eds. McEntyre, J. & Ostell, J.) Chap. 16 (2002).

O’Donnell, K. et al. No to Neocosmospora: Phylogenomic and practical reasons for continued inclusion of the Fusarium solani species complex in the genus Fusarium. mSphere 5, e00810-20 (2020).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A. & Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729 (2013).

Stamatakis, A., Hoover, P. & Rougemont, J. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst. Biol. 57, 758–771 (2008).

Mordy Golding. Adobe Illustrator CS5: For web and Interactive Design (Lynda.com, 2010). [2010] ©2010.

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2013).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Brooks, M. E. et al. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized Linear mixed modeling. R J. 9, 378–400 (2017).

Hartig, F. DHARMa: Residual diagnostics for hierarchical (multi-level/mixed) regression models (2021).

Lenth, R. V. Least-Squares Means: The R package lsmeans. J. Stat. Soft. 69, 1–33 (2016).

Harrell, F. E. Jr. Package ‘Hmisc’: Harrell miscellaneous (2020).

Lê, S., Josse, J. & Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R package for multivariate analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 25, 1–18 (2008).

Richard, A. & Allan, R. maps: Draw Geographical Maps. 3.4.2 (2022).

Hijmans, R. J. raster: Geographic Data Analysis and Modeling. 3.6-30 (2010).

Wickham, H. Ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (Springer, 2016).

Tufekci, A. ggsn: A package for adding scale bars and north arrows to ggplot2 maps (2021).

Geiser, D. M. et al. Phylogenomic analysis of a 55.1-kb 19-gene dataset resolves a monophyletic Fusarium that includes the Fusarium solani species complex. Phytopathology®111, 1064–1079 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out within the framework of the research projects PATHO-ID (2814EPS40) and APSOLU (2814EPS035), funded by the German Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture within the framework of the BMEL protein plant strategy, in cooperation with the German Demonstration network Pea/Bean.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.Š., H.S., J.B.Š., M.F study design/methodology/investigation. A.Š. analyzed the results, prepared data presentation and drafted the manuscript. A.Š., H.S., M.F resources/funding acquisition. All authors discussed results, revised the manuscript and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Šišić, A., Baćanović-Šišić, J., Schmidt, H. et al. Effect of management system and pedoclimatic factors on Fusarium and Didymella communities associated with pea (Pisum sativum) roots in Germany. Sci Rep 15, 2653 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86018-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86018-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Organic minimum tillage systems based on intensification of legume cover cropping: agronomic and phytopathological aspects

Agronomy for Sustainable Development (2025)