Abstract

Tylosema esculentum (marama bean), an underutilized orphan legume native to southern Africa, holds significant potential for domestication as a rescue crop to enhance local food security. Well-adapted to harsh desert environments, it offers valuable insights into plant resilience to extreme drought and high temperatures. In this study, k-mer analysis indicated marama as an ancient allotetraploid legume. Using 21.5 Gb of PacBio HiFi data, the genome was assembled with two assemblers, HiCanu and Hifiasm, followed by scaffolding with Omni-C data from Dovetail Genomics (Cantata Bio) using HiRise, resulting in a 558.78 Mb assembly with near chromosome-level continuity (N50 = 22.68 Mb, L50 = 8). Repeats accounted for 58.43% of the genome. Phylogenetic analysis indicated a close relationship with Bauhinia variegata and Cercis canadensis, diverging approximately 27.22 and 31.68 million years ago (Ma), respectively. Whole-genome duplication (WGD) analysis revealed an ancient duplication event in marama. Gene family analysis revealed expanded families enriched in pathways related to stress adaptation, energy metabolism, and environmental signaling, including the spliceosome, citrate cycle, and carbon fixation pathways. These findings highlight marama’s resilience to arid environments. In contrast, contracted gene families associated with secondary metabolite biosynthesis and defense pathways suggest a trade-off, potentially due to reduced pathogen pressure. Marama-specific genes were enriched in amino acid catabolism pathways, potentially playing roles in stress signaling and energy regulation. Core gene families shared with other legumes were enriched in conserved pathways, such as photosynthesis and hormone signaling, which are fundamental for plant growth and survival. Population analysis of geographically diverse samples revealed two distinct clusters, though phenotypic differences remain unclear. Overall, this study presents the first high-quality genome assembly of marama bean, offering a valuable genomic reference for understanding its unique biology and highlighting its potential for crop improvement in challenging environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tylosema esculentum, commonly known as the marama bean, is a long-lived perennial legume native to southern Africa (Fig. 1)1. Adapted to arid and semi-arid desert environments, marama employs a unique drought avoidance strategy by growing tubers that can weigh over 250 kg2 to store water, enabling survival in the prolonged hot and dry conditions of the Kalahari Desert (Fig. 1D)3. The domestication of marama has the potential to improve local food security due to the high nutritional value of its edible seeds, whose protein and lipid contents are comparable to those of commercial crops like soybean and peanuts4,5. A significant obstacle to marama breeding is its delayed flowering, typically occurring in the second year or later. This extended juvenile phase forces breeders to wait years to harvest seeds and assess desirable traits, significantly slowing the breeding cycle. Exploring the genotypic and phenotypic diversity in natural populations and employing molecular marker-assisted breeding strategies are effective alternatives to traditional breeding methods6,7. Key breeding goals for marama include shortening the flowering time to expedite seed acquisition and developing an erect growth habit to facilitate field harvests8. Additionally, overcoming self-incompatibility is essential for creating inbred lines that ensure stable inheritance of desirable traits and enabling crosses between previously incompatible varieties to produce new cultivars with favorable allelic combinations9,10. Studying marama also provides insights into plant adaptation to harsh environments, which is increasingly relevant in the context of global warming. A high-quality genome assembly will provide a valuable reference for exploring the genetic basis of relevant traits.

Morphology of wild T. esculentum (marama bean) from Namibia. (A). Brownish-black seeds, up to one inch long, are edible when roasted. The protein content is 30–39% dm and the lipid content is 35–48% dm11,12. (B). Prostrate form with stems up to 3 m long13. (C). Yellow flowers, beginning to bloom in midsummer, typically starting in at least the second year after planting. (D). Giant tubers weighing over 500 pounds, 90% of the weight comes from water2.

The estimated total genome size of T. esculentum is 1 gigabase (Gb), consisting 44 chromosomes (2n = 4x = 44), as determined through next-generation sequencing data and Feulgen staining6,14. A comprehensive dataset, accessible under PRJNA779273, encompasses Illumina whole-genome sequencing data from over 80 marama individuals sourced from various geographical locations in Namibia and South Africa, along with PacBio long reads from selected individuals. These data were used in assembling and analyzing the chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes of marama15,16,17. Comparative genomic studies were conducted to explore the genetic diversity within the marama organelle genome17,18. These studies revealed the presence of two distinct organelle genome types with substantial differences, the functional implications remain unknown. The assembly of the marama nuclear genome remained in a rudimentary state, with an N50 value of only 3 kilobases (kb), by Dr. Kyle Logue solely using short Illumina reads of marama17.

The advent of next-generation sequencing has significantly advanced genome assembly due to its cost-effectiveness, high speed, and throughput19. However, challenges persist in assembling complex genomes, such as polyploid and repeat-rich genomes, when solely relying on short reads from next-generation sequencing techniques. As a third-generation sequencing technology, PacBio offers longer reads, averaging over 10 kb and extending up to 25 kb, which addresses the shortcomings of previous methods. The latest PacBio HiFi sequencing enhances accuracy to over 99.9% while maintaining read length20, improving genome assembly quality. To further enhance genome assembly accuracy, particularly for complex genomes, high-throughput chromatin conformation capture (Hi-C) leverages genome-wide chromatin interactions to capture the 3D structure of chromosomes21,22. This is followed by sequencing, enabling accurate scaffolding of genome assemblies. Hi-C has become a widely used technology for studying complex plant genomes23,24.

This research aimed to generate the first high-quality genome assembly of T. esculentum (marama) using PacBio HiFi sequencing data. Preliminary assemblies were conducted using HiCanu25 and Hifiasm26, followed by scaffolding with Hi-C data and the HiRise assembler from Cantata Bio LLC to address the complexities of polyploid genomes. Comprehensive gene prediction and annotation were performed, and a comparative genomics study was conducted to analyze gene families in marama and related legumes. Functional uniqueness within the marama genome was identified, alongside phylogenetic analyses to clarify its evolutionary relationships and divergence from related species. Additionally, samples from different geographical regions were collected, and variants identified from resequencing data were used to explore the genetic diversity and population structure within the species, providing insights into marama’s evolution and adaptation. This work offers a valuable genomic resource to support future research and breeding efforts, enhancing marama’s potential as a resilient and sustainable food crop.

Methods

Sample collection and sequencing

Sample 4 of T. esculentum, cultivated in the Case Western Reserve University greenhouse from seeds of unknown provenance in Namibia, was utilized for DNA extraction and sequencing. Fresh young leaves (1 g) were ground in liquid nitrogen using a mortar and pestle, and high-molecular DNA was extracted using the Quick-DNA HMW MagBead kit (Zymo Research). DNA concentration was quantified using an Invitrogen™ Qubit™ 3.0 Fluorometer, and quality was assessed by electrophoresing 200 ng of DNA on a 1.5% agarose TBE gel at 40 V for 24 h.

For PacBio sequencing, DNA samples were submitted to the Genomics Core Facility at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Sequencing libraries were constructed using the SMRTbell® Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA). The libraries were sequenced on two 8 M SMRT® Cells using the Sequel® II platform generating 2,184,811 reads with a total yield of 21.5 Gbp.

To support genome scaffolding, fresh leaf samples from the same plant were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and shipped on dry ice to Dovetail Genomics (Cantata Bio) for Omni-C library preparation. Omni-C, an advanced Hi-C technology, employs sequence-independent endonucleases to achieve uniform genome-wide coverage, eliminating biases from restriction enzyme-based methods. Chromatin was fixed with formaldehyde, extracted, and digested with DNAse I before ligation to biotinylated bridge adapters. Proximity ligation was followed by crosslink reversal, removal of non-internal biotin, and library preparation using NEBNext Ultra enzymes and Illumina-compatible adapters. Libraries were enriched via streptavidin bead capture and amplified by PCR. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeqX platform, achieving ~30x coverage.

For transcriptome sequencing, high-quality RNA was extracted from leaf tissue (young leaves at the growing tip) and root tissue (root tips and young roots of germinated seeds) using the Quick-RNA Plant MiniPrep™ Kit (Zymo Research Corporation, Catalog No. 50–444-618). RNA quality and quantity were estimated by running a sample on a 2% agarose gel. RNA sequencing libraries were prepared by Novogene following a standard workflow. Messenger RNA (mRNA) was enriched from total RNA using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads, fragmented, and reverse-transcribed to synthesize first-strand cDNA using random hexamer primers, followed by second-strand synthesis. Library construction involved end repair, A-tailing, adapter ligation, size selection, amplification, and purification. Quality assessment was conducted using a Qubit fluorometer and real-time PCR for quantification, as well as a bioanalyzer for size distribution evaluation. The libraries were pooled and sequenced on the NovaSeq 6000 platform, generating 6.8 Gbp of transcriptomic data for root tissues and 7.2 Gbp for leaf tissues.

For the population study, Illumina whole-genome sequencing (WGS) data were generated for 84 individuals collected from various geographic regions in Namibia and South Africa. Details of sequencing protocols and data processing, are described in a previous study16. These data are available in the NCBI SRA database under Bioproject PRJNA779273.

De novo genome assembly and quality assessment

The preliminary assembly of PacBio HiFi reads was generated using two assemblers: Hifiasm v.0.18.5 (Cheng et al. 2021) with a haplotype number set to four, and HiCanu25 with an estimated genome size of 1 Gb based on previous assessments6. The HiRise pipeline27,28 was then used to scaffold the de novo assembly with the help of Dovetail OmniC reads. These reads were aligned to the draft assembly using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA)16 (https://github.com/lh3/bwa). HiRise analyzed the read pair distances within scaffolds to generate a likelihood model for genomic distance, which was used to identify and correct misjoins.

K-mer analysis of the PacBio HiFi reads was performed using Jellyfish v. 2.3.029 (https://github.com/gmarcais/Jellyfish) with a k-mer length of 21. The results were used to construct k-mer spectra with GenomeScope 2.030 (http://qb.cshl.edu/genomescope/genomescope2.0/). Assembly quality was assessed with QUAST v. 5.2.031 (https://github.com/ablab/quast) and visualized using Matplotlib v. 1.3.132. Genome completeness was evaluated using BUSCO v. 5.3.033 (https://busco.ezlab.org/) against the Embryophyta ortholog database (embryophyta_odb10, 1614 genes) and the Fabales ortholog database (fabales_odb10, 5366 genes).

Additionally, the genome assembly was compared to that of Bauhinia variegata (ASM2237911v2)34, the closest species with an available genome sequence, by aligning the assemblies with minimap2 v. 2.2816 (https://github.com/lh3/minimap2). The pairwise mapping data (PAF) was visualized using a dot plot created with the R package pafr (https://github.com/dwinter/pafr) to assess synteny and validate the assembly’s structure.

Gene prediction and functional annotation

A de novo repeat library was constructed for the assembly using RepeatModeler (v. 2.0)35. This custom library, combined with the Dfam v3.0 database36, was used to annotate and mask repetitive elements in the genome assembly with RepeatMasker v. 4.1.437 (https://www.repeatmasker.org/). Alignments were conducted using the rmblastn search engine38. For gene prediction, transcriptomic data were aligned to the genome assembly using HISAT2 v. 2.2.123,39, resulting in SAM files that were converted to sorted BAM files and combined using SAMtools v. 1.20. The BRAKER v 3.0.8 pipeline B40, which integrates evidence-based and ab initio approaches for gene annotation, was employed. The pipeline utilized RNA-Seq spliced alignment data to train GeneMark-ET v. 4.7141, incorporating both genome sequence and RNA-Seq evidence. The resulting gene models were then used to train Augustus v. 3.5.042 for final gene predictions.

A statistical summary of the annotation was generated from the resulting GFF file using the AGAT v. 1.0.0 toolkit43. The completeness of the gene annotation was assessed using BUSCO against the embryophyta_odb10 database. Functional gene annotation was performed using eggnog-mapper 2.1.1244 (http://eggnog-mapper.embl.de/), referencing the eggNOG 5 database45.

Evolutionary analyses: phylogenetic relationships, whole genome duplication, and gene enrichment

To investigate the evolutionary relationships of T. esculentum and related species, a comparative genomics study was conducted on the gene families of 13 legumes and one outgroup species, soapbark. The protein data of 9 species were retrieved from the JGI Phytozome v. 13 database46: Arachis hypogaea (v1.0)47, Cicer arietinum (v1.0)48, Medicago truncatula (Mt4.0v1)49, Lotus japonicus (Lj1.0v1)5051, Glycine max (Wm82.a2.v1)52, Phaseolus acutifolius (v1.0)53, Vigna unguiculata (v1.1)54, Lupinus albus (v1)55, Cercis canadensis (v3.1)56, and four from NCBI GenBank: Bauhinia variegata (ASM2237911v2)34, Prosopis alba (ASM479914v2), Prosopis cineraria (ASM2901754v1)57, and Quillaja saponaria (AO_1.2)58. CD-HIT v. 4.8.159 with a threshold of 0.95 was applied to retain only the longest isoform of each protein. OrthoFinder v. 2.4.060 was then utilized with an all-against-all method to identify orthologous genes across these species, which revealed the evolutionary relationship among these plant taxa.

A total of 157 single-copy orthologs were identified among 14 species and aligned using MAFFT v. 7.52061. Regions with poor alignment and high divergence were removed using Gblocks v. 0.91b62, specifying a minimum block length of 5, while all gaps were retained as meaningful. The trimmed alignments were concatenated into a single FASTA file. A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed using concatenated protein sequences in IQ-TREE v. 2.2.2.763 with the ModelFinder Plus (MFP)64 algorithm to automatically select the optimal substitution model. Tree topology robustness was assessed with 1000 bootstrap replications. Approximate divergence times for C. arietinum and M. truncatula (31.9 million years ago) and for G. max and V. unguiculata (25.3 million years ago) were retrieved from TimeTree (http://www.timetree.org)65. These divergence times were used to calibrate the overall divergence times in the phylogenetic tree using the Timetree Wizard66 in MEGA 1167.

Gene count data generated by OrthoFinder were used to calculate gene family size variation across the phylogenetic tree using CAFE5 v. 5.0.068. To mitigate potential noise from excessively large gene families and those with high variance, families with more than 100 gene copies were filtered out using the clade_and_size_filter.py script. The resulting data on gene family expansions and contractions (with a p-value < 0.05) were then mapped onto the phylogenetic tree, providing a visual representation of these evolutionary changes. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analyses were performed using TBtools 2.069 and the KEGG database70,71,72 on genes from the expanded and contracted gene families of T. esculentum. The top enriched pathways were visualized using ggplot2 in R, sorted by enrichment factor.

Orthologous gene families were also analyzed among five selected legumes, T. esculentum, B. variegata, C. canadensis, G. max, and P. alba, which include both closely related species of T. esculentum as well as representatives from different phylogenetic clusters. The distribution of shared and species-specific gene families was visualized using the VennDiagram package v. 1.7.369 in R 4.3.128. Genes in core gene families, shared by all five legumes, and genes in the T. esculentum-specific gene family were used for KEGG enrichment analyses with TBtools v. 2.0. The results were visualized using ggplot273 in R, offering a comprehensive understanding of the common and unique functional pathways among these five legumes.

For further investigating the evolutionary relationships between T. esculentum and its closely related legume species, C. canadensis and B. variegata, whole genome duplication (WGD) events were analyzed. The coding sequences (CDS) of the genomes were self-aligned to identify homologous gene pairs using DIAMOND (v. 2.1.8)74 with an e-value threshold of 1 × 10−10, in conjunction with WGD tools (v. 1.1.1)75. The synonymous substitution rates (Ks values) were subsequently calculated using the ksd function from the WGD tools, which employs PAML (v. 4.9 h)76 for codon-based maximum likelihood analysis. A Ks threshold of 0.1 was applied to exclude local duplication minimizing noise. The results of WGD were visualized as a curve plot using ggplot2 (v. 3.5.1) in R (v. 4.3.1) (R Core Team, 2023), offering a graphical representation of evolutionary relationships.

Population genetics analysis

The population study included 31 independent marama samples, with 24 collected from wild plants across various locations in Namibia: 3 from Tsjaka (S22 75.039 E19 20.712), 1 from Okamatapati (S20 40.233 E18 21.59), 8 from Aminuis (S23 38.000 E19 22.00), 4 from Osire (S21 02.031 E17 21.244), 3 from Tsumkwe (S19 21.000 E20 16.000), 2 from Ombujondjou (S20 18.600 E17 58.525), 2 from Epukiro (S21 39.642 E19 25.092), and 1 from Otjiwarongo (S20 46.092 E16 65.123). 6 samples were collected from the University of Pretoria Farm, where they had been cultivated for over thirty years with an unknown original source. Additionally, one sample was grown from seed collected from the Namibia Farm (21°23′48.5″ S 19°44′59.6″ E). DNA extraction was described in detail in the previous study16,77, and the whole-genome sequencing (WGS) reads are available in the NCBI SRA database under Bioproject PRJNA779273.

Paired-end Illumina reads were aligned to the genome assembly with BWA v 0.7.17 mem16, followed by conversion of SAM files to sorted BAM files using SAMtools v. 1.20. SNPs were called using BCFtools mpileup78. SNP processing involved multiple filtering steps to ensure high-quality variants. VCF files from different samples were first merged using BCFtools merge, and then filtered to retain only biallelic SNP variants using BCFtools view. Quality and depth filtering was applied with BCFtools filter, using thresholds of QUAL ≥ 30, DP > 10, and DP ≤ 100. The filtered VCF file was then normalized with BCFtools norm using the reference genome to ensure consistent variant representation. A final filter step retained variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) greater than 0.05 and SNP missing call rate lower than 0.3 for the population study.

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using PLINK v.2.0079, and the first two components were visualized using ggplot2 in R v.4.3.128. ADMIXTURE v.1.2380 was used to assess population structure, with the optimal number of populations determined through cross-validation errors and visualized with ggplot2. For phylogenetic analysis, the VCF file was converted to a PHYLIP alignment using vcf2phylip.py (v. 2.8)81 and a maximum likelihood tree was constructed with IQ-TREE (v. 2.2.2.7)63 using 1000 bootstrap replicates. The resulting tree was visualized using Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) (v. 6)82.

Results

Estimation of genome size and heterozygosity

A total of 21.5 Gbp PacBio HiFi reads were generated and analyzed to characterize the genomic properties of T. esculentum. K-mer analysis was conducted using a k-mer length of 21, and the resulting distribution was modeled with GenomeScope 2.0, producing a k-mer spectra map that revealed peaks corresponding to 1-fold, 2-fold, and 4-fold coverage (Fig. 2). The data more closely aligned with a tetraploid genome model than the initially hypothesized hexaploid model for T. esculentum. The predicted genome size for a single chromosome set was 277.44 Mb, which is comparable to the compact genome of the legume species Amphicarpaea edgeworthii, with a genome size of 298.1 Mb and a haploid chromosome number of 11 (2n= 22)83,84. Additionally, the k-mer spectra indicated substantial heterozygosity, with 2.2% of the genome exhibiting heterozygous characteristics. Notably, both the aaab (1.410%) and aabb pattern (0.498%) were observed at high frequencies, suggesting that T. esculentum may possess a complex ploidy structure, potentially indicative of an ancient allotetraploid that has accumulated mutations over time, leading to an elevated aaab pattern ratio30.

De novo genome assembly and evaluation

2,184,811 PacBio HiFi reads were subjected to preliminary assembly using HiCanu and Hifiasm. HiCanu produced a complete genome assembly of 1.24 Gb, composed of 9,532 contigs, a size that aligns closely with the expected structure of four chromosome sets. This assembly exhibited an N50 value of 1.28 Mb and an L50 value of 252 (indicating the minimum number of contigs whose combined length equals half the genome size) (Table 1). In contrast, Hifiasm generated a partially phased assembly of 558.23 Mb with higher continuity, consisting of 4,175 contigs. This assembly demonstrated a markedly improved N50 of 2.75 Mb and an L50 of 35. Both assemblies achieved high completeness, with BUSCO scores exceeding 99% when evaluated against the embryophyta_odb10 database.

Subsequently, the Hifiasm assembly was submitted to Dovetail Genomics (Cantata Bio) for Scaffolding using Omni-C data to capture chromatin interactions (Supplementary Figure S1). The final assembly size was 558.78 Mb, which is close with the estimated size of 554.88 Mb for the two sets of chromosomes. Despite the relatively high contig count (3,888), continuity was significantly improved, as evidenced by an N50 of 22.68 Mb, reaching chromosome-level assembly. The longest scaffold was 56.19 Mb (Fig. 3A). The L50 was reduced to 8, meaning that the top eight scaffolds collectively represented 50% of the genome size (Fig. 3B). The average guanine-cytosine (GC) content across all contigs was 37.20% (Table 1; Fig. 3C). BUSCO completeness remained robust, with a score of 99.1% against the Embryophyta database and 93.6% against the Fabales database.

Approximately 58.43% of the T. esculentum genome assembly was annotated as repetitive sequences (Table 2). The most prevalent repeat component, long-terminal repeat (LTR) retroelements, accounted for 22.61% of the genome, with Gypsy/DIRS1 elements comprising 15.65% and Ty1/Copia elements contributing 3.48%. Low-complexity regions (LCRs) and simple repeats represented 11.77% and 7.45% of the genome, respectively.

A total of 49,343 protein-coding genes were predicted using BRAKER 3(Table 3), with an average of 6.3 exons per gene, with each exon measuring 218.35 bp, and 5.1 introns per gene, averaging 369.56 bp in length. Evaluation of gene set completeness using BUSCO, with reference to the Embryophyta core gene database, revealed a completeness of 95.8%. The predicted gene set was further annotated using eggNOG-MAPPER against the eggNOG database v. 5.0.2, with results summarized in Supplementary Table S1.

Comparison of the genome assemblies of T. e sculentum and B. variegata

Genomes of a limited number of plants from the Cercidoideae subfamily have been assembled, with B. variegata being the closest evolutionary relative to T. esculentum85. The genome assembly of B. variegata (ASM2237911v2) spans 326.4 Mb and consists of 14 chromosomes (2n= 28), ranging in size from 18.26 Mb to 27.62 Mb34. The T. esculentum genome assembly was aligned to the B. variegata genome using minimap2, and the results were visualized as a dot plot with the R package pafr (Fig. 4). The alignment revealed partial collinearity, with conserved regions forming distinct diagonal lines. However, the presence of numerous missing alignments and structural variations, including inversions and translocations, highlights substantial genomic divergence between the two species. To further investigate, Illumina reads from three randomly selected T. esculentum samples (M1, M40, Index1) were mapped to the B. variegata genome using Bowtie2 v2.4.486 (https://github.com/BenLangmead/bowtie2). The overall alignment rate was approximately 20.36%, whereas mapping the same reads to the Vigna radiata genome (PRJNA301363) resulted in a significantly lower alignment rate of 2.7%87. These findings underscore the highly divergent nature of the T. esculentum genome compared to other legumes.

Dot plot of T. esculentum scaffolds aligned to the 14 chromosomes of the B. variegata genome (ASM2237911v2). This figure, created using the R package pafr, visualizes the alignment of T. esculentum scaffolds to the B. variegata genome based on a pairwise mapping format (PAF) file generated by minimap2. Each row represents a B. variegata chromosome, labeled on the right with its GenBank ID34. Columns represent T. esculentum scaffolds, sorted by size, with only scaffolds exceeding 1 Mb shown. Highly fragmented contigs are excluded for clarity. Black dotted lines indicate alignment points between the two genomes. Axis ticks mark genomic scales in megabase pairs (Mb).

Phylogenetic analyses, along with the evolution of gene families and whole genome duplication analysis of T. esculentum and related species

Ortholog analyses were performed on 14 species including 13 legumes, including three Cercidoideae (C. canadensis, B. variegata, and T. esculentum), two Caesalpinioideae (P. alba and P. cineraria), and eight Faboideae (A. hypogaea, C. arietinum, M. truncatula, L. japonicus, G. max, P. acutifolius, V. unguiculata, and L. albus), along with one outgroup species Q. saponaria, after using 95% similarity threshold to retain only the longest isoform. Out of a total of 510,326 genes, 472,973 (92.68%) were assigned to 33,383 orthogroups, with 40,527 genes in 9,466 orthogroups, identified as species-specific. The 157 single-copy orthogroups were used to construct a phylogenetic tree, with Q. saponaria as outgroup to root the tree (Fig. 5A). The divergence between B. variegata and T. esculentum was estimated to occur approximately 27.22 million years ago (Ma), and divergence with C. canadensis occurred 31.68 million years ago. The gene family number variation is close to that of B. variegata, with more gene families (2,231) underwent expansion than contraction (1,155). A total of 6707 genes in the T. esculentum expanded gene family and 951 genes in the contracted families were underwent KEGG pathway enrichment analyses using TBtools (Fig. 5B and C, Supplementary Table S4 and S5).

Evolutionary dynamics of gene families in T. esculentum and 13 related species. (A) A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed using concatenated protein sequences from 157 single-copy orthologs of T. esculentum and 13 other species, including 12 legumes and Q. saponaria as the outgroup. Sequences were aligned using MAFFT, and the tree topology was supported by 1000 bootstrap replicates. Gene family expansion and contraction counts, calculated by CAFE, are color-coded in blue (expansion) and red (contraction). Divergence times (million years ago, Ma) are annotated on the tree nodes. (B) KEGG enrichment analysis of genes in the 1155 contracted gene families of T. esculentum. (C) KEGG enrichment analysis of genes in the 2231 expanded gene families of T. esculentum. Enriched pathways are ranked by enrichment factor. Dot size indicates the number of enriched genes, while dot color represents significance, with red denoting higher significance and purple lower significance.

The contracted gene families in marama are primarily enriched in pathways associated with plant defense and stress adaptation, including plant secondary metabolite biosynthesis (00999), tropane, piperidine, and pyridine alkaloid biosynthesis (00960), and cutin, suberine, and wax biosynthesis (00073) (Fig. 5B). The contraction of genes in these pathways suggests a reduced capacity for synthesizing specialized metabolites and protective compounds, which are typically essential for defense against biotic stressors, such as pathogens88,89. This reduction likely reflects the lower pathogen pressure in marama’s native arid environment, where pathogen diversity and abundance are limited. Consequently, marama appears to prioritize resource allocation toward critical survival processes, such as drought tolerance, rather than extensive defense mechanisms. These findings highlight the trade-offs in marama’s genome that contribute to its resilience and efficient adaptation to harsh conditions.

The expanded gene families in marama are enriched in pathways essential for cellular function, energy metabolism, and stress adaptation, contributing to its remarkable resilience in arid environments (Fig. 5C). Key pathways such as the citrate cycle (TCA cycle) (00020), pyruvate metabolism (00620), and carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms (00710) highlight marama’s ability to optimize energy production and carbon assimilation under resource-limited conditions, critical for survival in drought-prone areas90,91. The expansion of arginine biosynthesis (00220) is particularly important, as arginine serves as a precursor for molecules involved in stress signaling, osmotic balance, and the detoxification of reactive oxygen species92,93. The increased presence of GTP-binding proteins (04031) reflects an expanded set of signaling molecules that play key roles in cellular communication, stress responses, and protein trafficking, enabling rapid adaptation to fluctuating environmental conditions94,95. Additionally, the expansion of the spliceosome pathway (03040) enhances RNA processing and gene expression regulation, supporting marama’s ability to fine-tune its transcriptome under stress96,97,98. Finally, the enrichment in structural proteins (99992) underscores the importance of maintaining cellular integrity, including DNA repair and cytoskeletal stability, ensuring marama’s structural resilience in extreme conditions99. Together, these expanded gene families provide marama with enhanced capabilities for energy production, stress response, and cellular maintenance, reinforcing its capacity to thrive in harsh, resource-limited environments.

Gene families in T. esculentum were compared to those of four selected legumes, B. variegata, C. canadensis, G. max, and P. alba (Fig. 6A). A total of 24,995 orthogroups were identified, of which 13,977 (55.92%) were core gene families shared across all five legumes, encompassing 24,348 genes. Additionally, 5,824 (23.30%) species-specific orthogroups were identified including 1,271 exclusive to T. esculentum, comprising 4,191 genes. KEGG enrichment analyses were performed on T. esculentum genes in both core and species-specific gene families (Supplementary Table S4 and S5), providing insights into the functional roles of the genes in each group.

Comparative analysis of gene families and evolutionary patterns in T. esculentum and related legumes. (A) Venn diagram showing the distribution of shared and species-specific gene families among T. esculentum and four other legume species. (B) Density curve illustrating the distribution of synonymous substitution rates (Ks) in homologous gene pairs among T. esculentum, B. variegata, and C. canadensis, provides insights into whole-genome duplication (WGD) events. (C) KEGG enrichment analysis of genes in core gene families shared by T. esculentum and the four legumes, highlighting enriched pathways. (D) KEGG enrichment analysis of genes in gene families unique to T. esculentum. Pathways are sorted by enrichment factor, with dot size representing the number of enrich genes and color indicating significance (red for higher significance, purple for lower significance).

Genes within the core gene families shared by the five legumes were enriched in pathways fundamental to plant growth, energy production, and stress response. Key enriched pathways include photosynthesis (00195, 00196), and plant hormone signal transduction (04075), which are essential for maintaining photosynthetic efficiency and regulating growth, both critical for legume development60,100. Additionally, pathways such as N-Glycan biosynthesis (00510) and GPI-anchor biosynthesis (00563) emphasize the significance of protein modification and cell wall maintenance in shared gene functions101,102,103,104. Metabolic pathways, including galactose metabolism (00052), highlight the role of energy regulation and signaling in supporting core biological processes105,106).

In contrast, marama-specific gene families were enriched in pathways associated with stress tolerance, energy storage, and specialized metabolism, which are crucial for its adaptation to harsh environmental conditions. Key pathways, including amino acid catabolism (00280, 00330, 00380 etc) and fatty acid degradation (00071), play pivotal roles in generating signaling molecules that regulate stress-responsive genes and proteins under stress conditions107,108,109,110. Additionally, pathways involved in terpenoid backbone biosynthesis (00900) and glucosinolate biosynthesis (00966) contribute to the synthesis of defense-related secondary metabolites, potentially enhancing marama’s ability to cope with both biotic and abiotic stressors111,112,113. Pathways such as DNA replication (03030) and porphyrin metabolism (00860) further support cellular maintenance and survival in extreme environments114,115. These findings underscore marama’s genetic adaptations that enable it to thrive in arid conditions, highlighting its potential for use in breeding drought-tolerant crops.

The synonymous substitution rate Ks values were calculated for homologous gene pairs in T. esculentum, B. variegata, and C. canadensis to investigate whole genome duplication (WGD) events and their evolutionary timelines (Fig. 6B). The Ks distribution for B. variegata (red curve) peaked at Ks value of 0.24, consistent with previous studies34,116, indicating a relatively recent WGD event. In contrast, the T. esculentum Ks distribution peaked at 0.30, suggesting that a WGD event occurred earlier than in B. variegata. For C. canadensis, the green curve showed only a small peak at a Ks value of 1.77, corresponding to the γ-WGT event within core eudicots approximately 120 million years ago117,118, with a broad divergence time range. Additionally, T. esculentum exhibited a minor slope starting at a Ks value of 2.08, suggesting the presence of an even more ancient WGD event. The detection of both recent and ancient whole-genome duplication signals in T. esculentum further supports the hypothesis that this species underwent multiple rounds of whole genome duplication, which likely contributed to its genome complexity.

Population analysis unveiled two distinct clusters

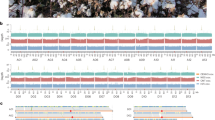

A total of 958,637,676 Illumina reads, corresponding to an estimated size of 100.4 Gbp, were generated for 31 T. esculentum individuals collected from various locations in Namibia and South Africa (Table 4). Following quality control filtering, 23,772 bi-allelic SNPs were retained for population analysis. Principal component analysis (PCA) revealed two distinct clusters among the 31 individuals (Fig. 7A). Notably, samples from Pretoria Farm and Namibia Farm exhibited genomic differentiation from wild plants collected across several locations in Namibia. Additionally, plants from the Northwest (NW) and Southeast (SE) regions showed no discernible genetic differentiation, while a previous study suggested the potential for dividing these two regions into two separate clusters based on mitogenome variants (Fig. 7A)119.

Population analysis of 31 T. esculentum samples reveals two distinct clusters. (A) Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plot of the first two principal components. Each dot represents one sample, colored by its sampling location. (B) Map showing sampling locations across Namibia, South Africa, and surrounding countries, with dot colors matching Panel (A) and sizes indicating sampling size. (C) Unrooted maximum likelihood (ML) tree constructed from a PHYLIP alignment of 23,772 SNPs, depicting the relationships among the 31 marama samples. (D) ADMIXTURE analysis of population structure at the optimal cluster number, K = 2.

A maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree, constructed from a PHYLIP alignment of the 23,772 SNPs, further corroborates the presence of two genetic clusters among the 31 T. esculentum individuals (Fig. 7C). Population structure analysis produced consistent results (Fig. 7D). Cross-validation error calculations performed using ADMIXTURE, indicated that the optimal number of clusters for the 31 individuals was K = 2 (Supplementary Figure S2). However, it remains unclear whether these two populations exhibit significant phenotypic differences, as considerable individual variation is already present within the species. Future systematic phenotyping and genotyping of larger sample sizes from diverse geographical locations will be essential for a more comprehensive understanding of T. esculentum’s evolutionary history and for providing guidance in variety selection for breeding programs.

Discussion

This study presents the first high-quality genome assembly of T. esculentum, featuring an N50 value of 2.75 Mb for contigs and 22.68 Mb for scaffolds, a significant improvement from the previous assembly’s 3 kb N50 achieved using only Illumina short reads by Dr. Kyle Logue. While the current genome assembly still contains numerous fragmented contigs, ongoing optimization efforts are anticipated to enhance its quality further. Despite these challenges, many contigs are sufficiently long, approaching near-chromosome level, enabling the study of genes of interest, providing a valuable reference for marama breeding and evolutionary research. This genomic resource establishes a foundation for investigating critical topics, such as the genetic mechanisms behind self-incompatibility, which is crucial for overcoming pollination barriers and developing stable inbred lines, as well as flowering time, which is essential for accelerating breeding cycles and improving crop productivity. Additionally, it provides insights into plant adaptation mechanisms, revealing how marama adapts to harsh desert and semi-desert environments. This information is critical for developing resilient varieties and enhancing the efficiency of breeding programs.

HiCanu generated an assembly with more fragmented contigs, yet it captured the entire genomic content, yielding a genome size approximating the tetraploid genome size of T. esculentum (marama). This is attributed to HiCanu’s default settings, which separate haplotypes at a low divergence threshold of 0.01%, preserving the integrity of the genome (https://canu.readthedocs.io/en/latest/faq.html). In contrast, the application of Hifiasm, coupled with the third-party purging tool Purge_Dups120, resulted in a genome assembly size that is closer to the expected two chromosome sets of marama. Despite this, the assembly still contains duplicated content. Further purging of duplications could refine the assembly by eliminating redundancies, but this may risk the collapse of critical repeats or segmental duplications essential for maintaining genomic stability.

To enhance assembly quality, future efforts could incorporate data from alternative long-read sequencing platforms, such as Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), which generates reads of significantly greater length (up to several hundred kilobases)105. These longer reads would improve scaffolding continuity, enabling the generation of a chromosome-scale assembly. Additionally, increasing sequencing coverage would further enhance the assembly’s completeness and reduce fragmentation. The integration of these complementary technologies has the potential to address current limitations, such as phase ambiguities and incomplete scaffolding, ultimately producing a more refined and accurate reference genome. Further improvement in continuity and completeness is essential, particularly for the investigation of large structural variations121, which could play a crucial role in advancing marama breeding by uncovering their functional impact.

The improved assembly and annotation of T. esculentum establish a robust foundation for future research. This genomic resource enables deeper exploration into the genetic mechanisms underlying key traits, such as self-incompatibility and adaptation to harsh environments. It also supports the development of molecular markers for breeding programs aimed at enhancing marama as a crop. Continued advancements in genome assembly and annotation will be crucial for fully unlocking the genetic potential of marama and facilitating its broader application in food security and agricultural research.

Data availability

All sequencing data for marama are publicly accessible under BioProject PRJNA779273 at NCBI. This includes the PacBio HiFi data for Sample 4 (SRR23882924) (https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra: SRR23882924) used for genome assembly in this study, as well as Illumina WGS data from 31 individuals for population analysis. The final genome assembly is deposited under BioProject PRJNA1197564.

Change history

21 August 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-10913-2

Reference

Kang, Y. J. et al. Genome sequence of mungbean and insights into evolution within Vigna species. Nat. Commun. 5 (1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms6443 (2014).

Dakora, F. D. Biogeographic distribution, nodulation and nutritional attributes of underutilized indigenous African legumes. Acta Hortic. 979, 53–64. https://doi.org/10.17660/actahortic.2013.979.3 (2013).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 9 (4), 357–359. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.1923 (2012).

Evans, J. R. Improving photosynthesis. Plant Physiol. 162 (4), 1780–1793. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.113.219006 (2013).

Reed, J. et al. Elucidation of the pathway for biosynthesis of saponin adjuvants from the soapbark tree. Science 379 (6638), 1252–1264. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adf3727 (2023).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 10 (2), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giab008 (2021).

Hunter, J. D. Matplotlib: a 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 9 (3), 90–95. https://doi.org/10.1109/mcse.2007.55 (2007).

Del Carmen Martínez-Ballesta, M., Moreno, D., & Carvajal, M. The physiological importance of glucosinolates on plant response to abiotic stress in brassica. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14 (6), 11607–11625. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms140611607 (2013).

Goodstein, D. M. et al. Phytozome: a comparative platform for green plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 (D1), D1178–D1186. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr944 (2011).

Guan, D. et al. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 36 (9), 2896–2898. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa025 (2020).

Chang, C. C. et al. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 4 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13742-015-0047-8 (2015).

Chen, H. & Boutros, P. C. VennDiagram: a package for the generation of highly customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinform. 12 (1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-35 (2011).

Chen, C. et al. TBTools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant. 13 (8), 1194–1202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009 (2020).

Wang, J., Yu, Y., Li, Y. & Chen, L. Hexose transporter SWEET5 confers galactose sensitivity to Arabidopsis pollen germination via a galactokinase. Plant Physiol. 189 (1), 388–401. https://doi.org/10.1093/plphys/kiac068 (2022).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive tree of life (iTOL) v6: recent updates to the phylogenetic tree display and annotation tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 52 (W1), W78–W82. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkae268 (2024).

Liang, Z., Huang, P., Yang, J. & Rao, G. Population divergence in the amphicarpic species Amphicarpaea Edgeworthii Benth. (Fabaceae): microsatellite markers and leaf morphology. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 96 (3), 505–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.2008.01154.x (2009).

Lieberman-Aiden, E. et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science 326 (5950), 289–293. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1181369 (2009).

Liu, Y. et al. Insights into amphicarpy from the compact genome of the legume Amphicarpaea Edgeworthii. Plant. Biotechnol. J. 19 (5), 952–965. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13520 (2020).

Zhou, K. The regulation of the cell wall by glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins in Arabidopsis. Front. Cell. Dev. Biology. 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.904714 (2022).

Jackson, J. C. et al. The morama bean (Tylosema esculentum): a potential crop for southern Africa. Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 61, 187–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-374468-5.00005-2 (2010).

Bertioli, D. J. et al. The genome sequence of segmental allotetraploid peanut (Arachis hypogaea). Nat. Genet. 51 (5), 877–884. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0405-z (2019).

Mendes, F. K., Vanderpool, D., Fulton, B. & Hahn, M. W. CAFE 5 models variation in evolutionary rates among gene families. Bioinformatics 36 (22-23), 5516–5518. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa1022 (2020).

Li, J. Draft genome assembly, organelle genome sequencing and diversity analysis of Marama bean (Tylosema esculentum), the green gold of Africa. Doctoral dissertation, Case Western Reserve University, OhioLINK Electronic Theses and Dissertations Center. (2023).

Nurk, S. et al. HiCanu: accurate assembly of segmental duplications, satellites and allelic variants from high-fidelity long reads. Genome Res. 30 (9), 1291–1305. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.263566.120 (2020).

Ranallo-Benavidez, T. R., Jaron, K. S. & Schatz, M. C. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 1432. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-14998-3 (2020).

Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117 (17), 9451–9457. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1921046117 (2020).

Fu, L., Niu, B., Zhu, Z., Wu, S. & Li, W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28, 3150–3152. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565 (2012).

Gabriel, L. et al. BRAKER3: fully automated genome annotation using RNA-seq and protein evidence with GeneMark-ETP, AUGUSTUS, and TSEBRA. Genome Res. 34 (5), 769–777. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.278090.123 (2024).

Nagashima, Y., von Schaewen, A. & Koiwa, H. Function of N-glycosylation in plants. Plant Sci. 274, 70–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.05.007 (2018).

Stai, J. S. et al. Cercis: a non-polyploid genomic relic within the generally polyploid legume family. Front. Plant Sci. 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00345 (2019).

Phytozome Cercis canadensis v3.1 [Genome assembly]. DOE-JGI. (2023). http://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/info/Ccanadensis_V3_1

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28 (11), 1947–1951. https://doi.org/10.1002/pro.3715 (2019).

Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr. Protoc. Bioinf. 25 (1). https://doi.org/10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25 (2009).

Ragaey, M. M., Sadak, M. S., Dawood, M. F. A., Mousa, N. H. S., Hanafy, R. S., & Latef, A. a. H. A. Role of signaling molecules sodium nitroprusside and arginine in alleviating Salt-Induced oxidative stress in wheat. Plants, 11(14), 1786. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11141786 (2022).

Hubley, R. et al. The Dfam database of repetitive DNA families. Nucleic Acids Res. 44 (D1), D44–D81. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1272 (2016).

Jiao, Y. et al. A genome triplication associated with early diversification of the core eudicots. Genome Biol. 13 (1), R3. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2012-13-1-r3 (2012).

Wunderlin, R. P. Reorganization of the cercideae (Fabaceae: Caesalpinioideae). Phytoneuron 48, 1–5 (2010).

Cantalapiedra, C. P., Hernández-Plaza, A., Letunic, I., Bork, P. & Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38 (12), 5825–5829. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab293 (2021).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34 (18), 3094–3100. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191 (2018).

Hon, T. et al. Highly accurate long-read HiFi sequencing data for five complex genomes. Sci. Data. 7 (1), 399. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-00743-4 (2020).

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37 (5), 1530–1534. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msaa015 (2020).

Veličković, D. et al. Spatial mapping of plant N-Glycosylation cellular heterogeneity inside soybean root nodules provided insights into Legume-Rhizobia symbiosis. Front. Plant Sci. 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.869281 (2022).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. Kegg: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 (1), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/28.1.27 (2000).

Castresana, J. Selection of conserved blocks from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17 (4), 540–552. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334 (2000).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. Kegg for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51 (D1), D587-D592. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkac963 (2022).

Huerta-Cepas, J. et al. eggNOG 5.0: a hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 47. D309-D314. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1085 (2018).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst010 (2013).

Zhang, Z., Mao, C., Shi, Z. & Kou, X. The amino acid metabolic and carbohydrate metabolic pathway play important roles during salt-stress response in Tomato. Front. Plant Sci. 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.01231 (2017).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C., & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nature Biotechnology, 37 (8), 907–915. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4 (2019).

Manova, V. & Gruszka, D. DNA damage and repair in plants – from models to crops. Front. Plant Sci. 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00885 (2015).

Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27 (6), 764–770. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011 (2011).

Sudalaimuthuasari, N. et al. The genome of the mimosoid legume Prosopis cineraria, a desert tree. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23 (15), 8503. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23158503 (2022).

Punzo, P., Grillo, S. & Batelli, G. Alternative splicing in plant abiotic stress responses. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 48 (5), 2117–2126. https://doi.org/10.1042/bst20200281 (2020).

Mello, B. Estimating TimeTrees with MEGA and the TimeTree resource. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35 (9), 2334–2342. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msy133 (2018).

Lee, H. et al. Legume genome structures and histories inferred from Cercis Canadensis and Chamaecrista Fasciculata genomes. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.03.611065 (2024).

Serrano, M., Coluccia, F., Torres, M., L’Haridon, F. & Metraux, J. P. The cuticle and plant defense to pathogens. Front. Plant Sci. 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2014.00274 (2014).

Von Bubnoff, A. Next-generation sequencing: The race is on. Cell 132 (5), 721–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.028 (2008).

Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 34 (Web Server), W435–W439. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkl200 (2006).

Li, J. & Cullis, C. A. The multipartite mitochondrial genome of marama (Tylosema esculentum). Front. Plant. Sci. 12, 787443. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.787443 (2021).

Li, J. & Cullis, C. A. Comparative analysis of 84 chloroplast genomes of Tylosema esculentum reveals two distinct cytotypes. Front. Plant. Sci. 13, 1025408. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2022.1025408 (2023).

Li, J. & Cullis, C. A. Comparative analysis of Tylosema esculentum mitochondrial DNA revealed two distinct genome structures. Biology 12 (9), 1244. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology12091244 (2023).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25 (4), 1754–1760. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 (2009).

Pichersky, E. & Raguso, R. A. Why do plants produce so many terpenoid compounds? New Phytol. 220 (3), 692–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14178 (2016).

Keith, M. & Renew, A. Notes on some edible wild plants found in the Kalahari. Koedoe 18 (1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4102/koedoe.v18i1.911 (1975).

Liang, Q. et al. A view of the pan-genome of domesticated Cowpea (Vigna unguiculata [L.] Walp). Plant. Genome. 17 (1), e20319. https://doi.org/10.1002/tpg2.20319 (2023).

Omotayo, A. O. & Aremu, A. O. Marama bean [Tylosema esculentum (Burch) A. Schreib.]: an indigenous plant with potential for food, nutrition, and economic sustainability. Food Funct. 12 (6), 2389–2403. https://doi.org/10.1039/d0fo01937b (2021).

Winter, G., Todd, C. D., Trovato, M., Forlani, G. & Funck, D. Physiological implications of arginine metabolism in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00534 (2015).

Ortiz, E. M. vcf2phylip v2.0: Convert a VCF matrix into several matrix formats for phylogenetic analysis [Software]. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.2540861 (2019).

Cullis, C. et al. Development of marama bean, an orphan legume, as a crop. Food Energy Secur. 8, e00164. https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.164 (2019).

Khedr, A. H. A. Proline induces the expression of salt-stress-responsive proteins and may improve the adaptation of Pancratium maritimum L. to salt-stress. J. Exp. Bot. 54 (392), 2553–2562. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erg277 (2003).

Mascher, M. et al. A chromosome conformation capture ordered sequence of the barley genome. Nature 544 (7651), 427–433. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature22043 (2017).

Kong, W., Wang, Y., Zhang, S., Yu, J. & Zhang, X. Recent advances in assembly of complex plant genomes. Genomics Proteom. Bioinf. 21 (3), 427–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2023.04.004 (2023).

Hasan, N., Choudhary, S., Naaz, N., Sharma, N. & Laskar, R. A. Recent advancements in molecular marker-assisted selection and applications in plant breeding programmes. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 19 (1), 128. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43141-021-00231-1 (2021).

Mikheenko, A., Prjibelski, A., Saveliev, V., Antipov, D. & Gurevich, A. Versatile genome assembly evaluation with QUAST-LG. Bioinformatics 34 (13), i142–i150. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty266 (2018).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. Benchmarking orthogroup inference accuracy: revisiting Orthobench. Genome Biol. Evol. 12 (12), 2258–2266. https://doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evaa211 (2020).

Moghaddam, S. M. et al. The tepary bean genome provides insight into evolution and domestication under heat stress. Nat. Commun. 12 (1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22858-x (2021).

He, M. & Ding, N. Z. Plant unsaturated fatty acids: multiple roles in stress response. Front. Plant Sci. 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.562785 (2020).

Depuydt, S. & Hardtke, C. S. Hormone signaling crosstalk in Plant Growth Regulation. Curr. Biol. 21 (9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2011.03.013 (2011).

Cullis, C. A., Chimwamurombe, P., Barker, N. P., Kunert, K. J. & Vorster, J. Orphan legumes growing in dry environments: marama bean as a case study. Front. Plant. Sci. 9, 1199. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.01199 (2018).

Alexander, D. H., Novembre, J. & Lange, K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 19 (9), 1655–1664. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.094052.109 (2009).

Schmutz, J. et al. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature 463 (7278), 178–183. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08670 (2010).

Li, H., Jiang, F., Wu, P., Wang, K. & Cao, Y. A high-quality genome sequence of model legume Lotus japonicus (MG-20) provides insights into the evolution of root nodule symbiosis. Genes 11 (5), 483. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes11050483 (2020).

Kim, Y. & Cullis, C. A. A novel inversion in the chloroplast genome of marama (Tylosema esculentum). J. Exp. Bot. 68 (8), 2065–2072. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erw500 (2017).

Putnam, N. H. et al. Chromosome-scale shotgun assembly using an in vitro method for long-range linkage. Genome Res. 26 (3), 342–350. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.193474.115 (2016).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Laloum, T., Martín, G. & Duque, P. Alternative splicing control of abiotic stress responses. Trends Plant Sci. 23 (2), 140–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2017.09.019 (2018).

Kumar, S. et al. TimeTree 5: an expanded resource for species divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 39 (8), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msac174 (2022).

Kalyaanamoorthy, S., Minh, B. Q., Wong, T. K. F., Von Haeseler, A. & Jermiin, L. S. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods. 14 (6), 587–589. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.4285 (2017).

Tahjib-Ul-Arif, M. et al. Citric acid-mediated abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (13), 7235. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22137235 (2021).

Showalter, A. M. Structure and function of plant cell wall proteins. Plant. Cell. 5 (1), 9. https://doi.org/10.2307/3869424 (1993).

Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., Bollas, A., Wang, Y. & Au, K. F. Nanopore sequencing technology, Bioinformatics and Applications. Nat. Biotechnol. 39 (11), 1348–1365. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-021-01108-x (2021).

Singh, B. & Sharma, R. A. Plant terpenes: defense responses, phylogenetic analysis, regulation and clinical applications. 3 Biotech. 5 (2), 129–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13205-014-0220-2 (2014).

Bower, N. W., Hertel, K., Oh, J. & Storey, R. Nutritional evaluation of marama bean (Tylosema esculentum, Fabaceae): analysis of the seed. Econ. Bot. 42, 533–540 (1988).

Agarwal, P. K. et al. Constitutive overexpression of a stress-inducible small GTP-binding protein pgrab7 from Pennisetum glaucum enhances abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic tobacco. Plant Cell Rep. 27 (1), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-007-0446-0 (2007).

Young, N. D. et al. The Medicago genome provides insight into the evolution of rhizobial symbioses. Nature 480 (7378), 520–524. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10625 (2011).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis (2nd ed.) [PDF]. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4 (2016).

Takundwa, M., Chimwamurombe, P. M. & Cullis, C. A. A chromosome count in marama bean (Tylosema esculentum) by Feulgen staining using garden pea (Pisum sativum l) as a standard. Res. J. Biol. 2, 177–181 (2012).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G. & Kumar, S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38 (7), 3022–3027. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab120 (2021).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31 (19), 3210–3212. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 (2015).

Tuteja, N. & Sopory, S. K. Plant signaling in stress. Plant Signal. Behav. 3 (2), 79–86. https://doi.org/10.4161/psb.3.2.5303 (2008).

Varshney, R. K. et al. Draft genome sequence of chickpea (Cicer arietinum) provides a resource for trait improvement. Nat. Biotechnol. 31 (3), 240–246. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2491 (2013).

Basu, S., Ramegowda, V., Kumar, A. & Pereira, A. Plant adaptation to drought stress. F1000Research 5, 1554. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.7678.1 (2016).

Zhong, Y. et al. Chromosomal-level genome assembly of the orchid tree Bauhinia variegata (Leguminosae; Cercidoideae) supports the allotetraploid origin hypothesis of Bauhinia. DNA Res. 29 (2). https://doi.org/10.1093/dnares/dsac012 (2022).

Yuan, Y., Bayer, P. E., Batley, J., & Edwards, D. Current status of structural variation studies in plants. Plant Biotechnology J, 19 (11), 2153–2163. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13646 (2021).

Amarteifio, J. O. & Moholo, D. The chemical composition of four legumes consumed in Botswana. J. Food Compos. Anal. 11, 329–332 (1998).

Belitz, H.-D., Grosch, W. & Schieberle, P. Food chemistry (Springer Science & Business Media, 2004). Bower, N. W., Hertel, K., Oh, J. & Storey, R. Nutritional evaluation of marama bean (Tylosema esculentum, Fabaceae): analysis of the seed. Econ. Bot. 42, 533–540 (1988).

Iriti, M. & Faoro, F. Chemical diversity and defence metabolism: how plants cope with pathogens and ozone pollution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 10 (8), 3371–3399. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms10083371 (2009).

Enciso-Rodriguez, F. et al. Overcoming self-incompatibility in diploid potato using CRISPR-Cas9. Front. Plant. Sci. 10, 376. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2019.00376 (2019).

Batoko, H., Jurkiewicz, P. & Veljanovski, V. Translocator proteins, porphyrins and abiotic stress: new light? Trends Plant Sci. 20 (5), 261–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2015.03.009 (2015).

Yang, Z. PAML 4: Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Bio Evol, 24 (8), 1586–1591. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msm088 (2007).

Cullis, C. A., Chimwamurombe, P. M., Kunert, K. J. & Vorster, J. Perspective on the present state and future usefulness of marama bean (Tylosema esculentum). Food Energy Secur. 12 (2). https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.422 (2022).

Shi, H. et al. Manipulation of arginase expression modulates abiotic stress tolerance in Arabidopsis: effect on arginine metabolism and ROS accumulation. J. Exp. Bot. 64 (5), 1367–1379. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ers400 (2013).

Dainat, J. A. G. A. T. Another GFF analysis toolkit to handle annotations in any GTF/GFF format. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3552717 (2020)

Beihammer, G., Maresch, D., Altmann, F. & Strasser, R. Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-Anchor synthesis in plants: a glycobiology perspective. Front. Plant Sci. 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2020.611188 (2020).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C., & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using diamond. Nature Methods, 12 (1), 59–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3176 (2014).

Belton, J. et al. Hi–C: a comprehensive technique to capture the conformation of genomes. Methods 58 (3), 268–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.05.001 (2012).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 10 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-10-421 (2009).

Chen, H., spsampsps Zwaenepoel, A. Inference of ancient polyploidy from Genomic Data. Methods Mol Biol. , 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-2561-3_1 (2023).

Lomsadze, A., Ter-Hovhannisyan, V., Chernoff, Y. O. & Borodovsky, M. Gene identification in novel eukaryotic genomes by self-training algorithm. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 6494–6506. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gki937 (2005).

Hufnagel, B. et al. High-quality genome sequence of white lupin provides insight into soil exploration and seed quality. Nat. Commun. 11 (1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-14197-9 (2020).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. (2021). https://www.R-project.org/

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank K. Logue for help with the initial genome assembly, and P. Chimwamurombe, M. Takundwa, J. Vorster, and K. Kunert for providing marama samples from Namibia and from the University of Pretoria Farm, and to students in BIOL 301/401 in 2015 for their assistance with DNA extraction and those in BIOL 309 in 2018 for their contributions to sample collection.

Funding

This work was supported by teaching resources from the Department of Biology, Case Western Reserve University. The collections were supported by a grant from the Kirkhouse Trust to P. Chimwamurombe.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. conducted DNA extraction, performed genome assembly, data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. C.C. conceived the original project idea, extracted DNA, supervised the research, and assisted in writing and editing the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in the ordering of References. The references have been reordered and cited accordingly.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Cullis, C. Genome assembly and population analysis of tetraploid marama bean reveal two distinct genome types. Sci Rep 15, 2665 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86023-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86023-w