Abstract

The literature shows a lack of significant research on the synthesis of large spherical PbTe quantum dots (QDs), particularly with controllable sizes and morphology. Here, we present for the first time a novel hot-injection method for the tunable, high-quality synthesis of cubooctahedral PbTe QDs within the size range of 10 nm to 16 nm. This method employs a combination of oleic acid (OA) with shorter carboxylic acids, including octanoic (OctA), decanoic (DA), and lauric acids (LA), tested at various volumetric ratios. Our investigation reveals that different ratios of these acids result in diverse morphologies. Lower concentrations (0.5:5.5 and 1:5) favor cubical morphologies while increasing the concentration of short ligands induces a transformation to cubooctahedral shapes. This shape change is associated with the disruption of nanocrystal (NC) crystallinity. Higher ratios of short ligands produce PbTe NCs with a crystallite core and an amorphous shell. Our findings demonstrate the tunability and precise control achieved with this mixed capping ligand hot-injection method, which significantly impacts QD applications in photovoltaics, electronics, and energy. Notably, shorter capping ligand (OctA) result in more monodispersed PbTe QDs, yielding larger cubooctahedral QDs up to 16 nm. Conversely, using capping ligands with lengths similar to OA leads to unstable and less tunable synthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lead chalcogenide QDs like PbTe show considerable potential for telecommunications1, photo-electrics2, thermo-electrics3, as well as photovoltaics4 applications due to their size-tunable electronic bandgap that results from the quantum confinement effect5,6,7,8. These applications require precise control over QD size and morphology, as these properties directly influence optical and electronic behavior. Despite the growing interest, achieving consistent size and shape control in PbTe QDs remains challenging, especially as particle size increases. Previous studies demonstrate that synthetic parameters — such as reaction time, temperature, capping ligand, and the ratio of ligands to metal salts — are crucial for controlling size and shape of PbTe QDs9,10,11.

Ligands play a significant role in determining the shape and size of QDs. The morphology of Pb-chalcogenide QDs can be tuned by choosing a specific ligand and controlling its concentration. Usually, increasing the carboxylic acid ligand concentration boosts the QDs’ growth11,12. Shrestha et al. reported that increasing the concentration of OA slow down the nucleation and promote the growth of larger QDs by reducing supersaturation, leading to fewer nuclei and larger particles12. Murray et al. successfully synthesized PbTe QDs of various sizes from ~ 4 nm to 14 nm by manipulating OA concentration, using a hot-injection method13. Such transformations often lead to cubic shapes above ~ 10 nm11,12,14.

Additionally, ligand chain length and branching significantly impact precursor reactivity. Shorter or less branched ligands tend to increase reactivity, leading to the formation of smaller, more uniform QDs under controlled conditions13,15. Liu et al. used various carboxylic acid lengths to check their influence on the reactivity of the Pb precursor. They mixed OA with carboxylic acids of varying carbon chain lengths (C8-C24), including octanoic, dodecanoic, myristic, and lignoceric acids, to synthesize Pb-chalcogenide QDs using a non-injection and low-temperature approach (growth temperature of 30–120 °C). Various Pb-ligand monomers precipitated at temperatures of 80 –25 °C during the cooling process16. Niu et al. used different combinations of DA and oleylamine (OLA) in the non-injection method for PbTe QD shape control. Spherical particles were formed with the excess of DA, however with the OLA excess the final QDs shape was cubical17.

Achieving large, spherical PbTe QDs is challenging due to their tendency to adopt cubic shapes when particle sizes exceed 10 nm, as surface energy minimization favors cubic morphologies, which complicates their use in uniform layer fabrication for optoelectronic applications11,18,19,20,21. T. Mokkary et al. synthesized large PbTe QDs (20 nm, 28 nm, and 40 nm) using a complex, non-standard hot-injection method10. Moreover, some progress has been made with other Pb-chalcogenides, such as PbSe and PbS. For instance, V. Sousa et al. developed a heating-up method to produce 13 nm spherical PbSe QDs, though their work did not extend beyond this specific size22. Similarly, D. Cadavid et al. synthesized 16 nm cubic PbSe QDs, extending their size up to 30 nm through annealing at 450 °C, albeit at the expense of synthesis process complexity23. While these studies offer insights into achieving larger, spherical forms of Pb-chalcogenide QDs, large, spherical PbTe QDs have yet to benefit from a similarly well-defined protocol, highlighting the need for innovative approaches to achieve scalable and monodisperse PbTe QD synthesis in spherical shape.

In this manuscript, we present a modified hot-injection synthesis method that combines OA with shorter carboxylic acids (OctA, DA, and LA) to tune PbTe QD size and morphology across a range of 10–16 nm. By varying the molar ratios of OA with these short-chain ligands at a constant temperature of 180 °C, we achieve significant control over QD morphology, enabling the formation of larger, more uniform spherical particles. This controlled synthesis offers a novel approach to address the limitations of conventional OA-based methods, presenting a versatile solution for creating PbTe QDs suitable for photovoltaic and other optoelectronic applications.

Experimental

Materials

Squalane (99%), tellurium (99.999% powder), lead (II) acetate trihydrate (99%), and lauric acid (99%) were purchased from Acros Organics; Trioctylphosphine (TOP, technical grade 90%) oleic acid (technical grade 90%) octanoic acid (98+%), and decanoic acid (99%) were purchased from Alfa Aesar; Hexane (AR) was purchased from Bio-Lab; Ethanol (99.99%) was purchased from Romical.

Instrumentation

High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) imaging was carried out using a JEOL JEM-2100F microscope, operating at 200 keV, equipped with a GATAN 894 US1000 camera. The images were taken using a GATAN 806 HAADF STEM detector. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) analysis was performed using a JEOL JEM-2100F TEM operating at 200 keV equipped with an Oxford Instruments X-Max 65T SDD detector. The probe size during the analysis was set to 1 nm. AZtec software (v. 3.3) was used for the EDS data analysis. The quantitative analysis was performed by the standardless Cliff − Lorimer method. HRTEM experiments were conducted on a JEOL JEM-2010F microscope, using an accelerating voltage of 200 keV. EDS was conducted using a Noran System Six mounted on the microscope, manufactured by Thermo Fisher Scientific. HRTEM images were recorded using a K2 direct detection camera manufactured by Gatan-Ametek and operated in linear mode. ImageJ software was used for NC size and size distribution calculations. The image processing was performed using the threshold function. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded on an x-ray diffractometer (PANalytical X"Pert Pro) using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) to determine the NC structure. The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) study was performed by XPS ESCALAB 250 from Thermo Fisher Scientific. NMR experiments were conducted on a Bruker Avance III HD (400 MHz and 101 MHz for 1H and 13C, respectively) spectrometer.

PbTe QDs synthesis

0.75 M trioctylphosphine telluride (TOP-Te) stock solution was prepared in a glove box. The solution was stirred overnight until it became clear and yellow (flask A). Then, it was removed from the glove box and connected to the nitrogen Schlenk line just before the beginning of the reaction. The reaction was performed in a 50 mL three-necked round-bottom flask B. Flask B was connected to a thermocouple on one side, the other was stopped with a rubber septum, and in the middle was connected a condenser, which was connected to a Schlenk line. The lead-acid precursor was prepared by dissolving Pb(OAc)2·3H2O in a mixture of OA and short ligand (OctA, DA, or LA) in squalene. The molar concentration of lead in the solution (ligands and solvent) was 0.1 M. The ratios between the long ligand (OA) and the short ligand (OctA/DA/LA), were 6: 0, 5.5: 0.5, 5: 1, 4.5: 1.5, 4:2 and 3: 3. The mixture was stirred and heated to 40 °C under vacuum until the bubbling stopped (to avoid pumping the solution into the Schlenk-line apparatus). Then, the temperature was raised to 100 °C and kept there for 45 min. The resulting transparent solution containing the lead-acid precursor was heated to 180 °C under nitrogen and kept at this temperature for 10 min. The color of the solution turned yellowish. From flask A, 6 mL of 0.75 M TOP-Te solution (corresponding to a 1:3 Pb/Te molar ratio) were rapidly injected into the hot lead-acid solution and vigorously stirred. The color of the solution quickly turned black due to instant nucleation. Rapid injection and vigorous stirring are essential for narrow size distribution due to the rapid nucleation. The temperature dropped to 155–170 °C immediately after the injection. 2 min after the injection, the reaction was quenched by replacing the heating mantle with a water bath.

A typical synthesis of 14.6 nm PbTe QDs starts with a lead-acid precursor solution containing 0.570 g Pb(OAc)2·3H2O (1.5 mmol), 5 mL OA, 1 mL OctA, and 9 mL of squalane in a three-necked round bottom flask. After evacuating all water and acetic acid content under vacuum at 100 °C, the reaction solution was heated to 180 °C. 6 mL of 0.75 M TOP-Te solution (4.5 mmol) were rapidly injected into the hot reaction mixture. The reaction temperature dropped to 156–158 °C. The growth time at this temperature range was 2 min. The reaction was quenched with a water bath. When the temperature reached 30 °C, 8 mL of hexane were added and the reaction mixture was transferred into a 50 mL centrifuge tube. The tube was centrifuged for 4 min at 4400 rpm to separate the PbTe QDs from the supernatant. After QDs were dispersed in 20 mL of ethanol and centrifuged for an additional 4 min at 4400 rpm, the precipitated QDs were redispersed in hexane for further storage. The final QD solution was filtered through a 0.22 µ filter and 0.1µ filter as an additional cleaning step.

Results and discussion

PbTe QDs synthesis with oleic acid

Size calculation and morphology analysis were carried out by HRTEM. HRTEM, selective area electron diffraction (SAED), and XRD methods were utilized to determine QDs’ crystallinity and crystal structure. EDS was performed to calculate each synthesis’s Te: Pb atomic ratio. XPS was used for elemental and electronic state analyses. NMR spectroscopy was utilized for ligand binding to the QD.

At the beginning of this work, the PbTe QDs synthesis protocol with OA ligand (PbTe-OA), published by Urban J. J. et al., was chosen as the initial reference protocol for the QDs synthesis11. The published synthesis was modified according to our research preferences. Here is a simplified description of the PbTe QDs synthesis process using the hot injection method with OA, TOP, Te, and Pb(OAc)2. The initial step required for the precursor solutions preparation is mixing Pb(OAc)2 with OA, and Te with TOP, to form Pb-oleate and TOP-Te, respectively. The OA acts as a surfactant, stabilizing the growing nanocrystals and controlling their size and shape. The TOP-Te serves as a source of tellurium, facilitating the growth of PbTe nanocrystals. Rapid injection of the complex into the hot Pb-oleate precursor solution initiates nucleation. Pb-oleate complex reacts with TOP-Te precursor to form PbTe nuclei. After the desired growth period, the reaction is quenched by rapid cooling of the solution, and the QDs are formed24.

The obtained QDs’ size was 12.6 ± 1.1 nm (σ = 8.7%); the QDs were cubical (Fig. 1a-c). EDS results represent an atomic ratio of 1: 1.32 of Te to Pb (Table 1); the spectrum is shown in Figure S1. The SAED showed the following planes: [200], [220], [400], [420], and [422] (inset in Fig. 1d). The d-spacing was calculated using ImageJ software from the HRTEM images. The corresponding d-spacings of 0.331 nm and 0.185 nm were correlated to the [200] and [222] planes, respectively.

(a) Low-magnification HRTEM image of cubic PbTe-OA QDs of 12.6 ± 1.1 nm size. The image depicts the shape and uniformity of the QDs, (b) high-magnification HRTEM image represents the QDs crystallinity, (c) PbTe-OA QDs size histogram, and (d) SAED and XRD pattern of cubic PbTe-OA QDs (red) and PbTe pattern from the database -PDF 01-078-1904 (blue).

Powder XRD patterns of PbTe-OA QDs demonstrated the crystallinity of the particles. The diffraction pattern of PbTe-OA was matched with the available pattern in the database (PDF 01-078-1904). PbTe-OA QDs showed a major rock salt crystal structure with an Fm-3m space group and a lattice constant of a = 6.438 Å. The pattern exhibits peaks at 2Ɵ angles of 23.8, 27.5, 39.4, 48.9, 56.9, 64.6, and 71.6, which correspond to [111], [200], [220], [222], [400], [420], and [422] crystal planes of PbTe-OA QDs, respectively (Fig. 1d). Previously, similar XRD patterns were demonstrated in the literature25,26,27. The crystallite size of the PbTe-OA QDs was estimated, using Scherrer’s equation, from their (200) peak. The calculated nanocrystal (NC) size was 10.2 nm.

An XPS analysis was carried out. The full survey spectrum can be found in Figure S14. The survey spectrum contains all the characteristic Pb, Te, O, and C peaks. Moreover, the high-resolution spectra for Pb-4f and Te-3d are shown in Fig. 2. The Pb 4f5/2 peaks appear around 142–143 eV; the Pb 4f7/2 peaks can be found at 137–138 eV. Furthermore, the Te 3d3/2 and Te 3d5/2 can be found at 585–586 eV and 575–576 eV binding energies, respectively. A doublet originating from the spin-orbit coupling can be detected in both cases. A similar XPS analysis has been reported previously in the literature28,29.

According to the literature the nanocrystal formation mechanism may also be represented by the reaction equations (Eqs. 1–3). Lead precursor reacts with TOP-Te to form PbTe QDs. The overall reaction releases acetic acid and TOP as byproducts7,11,30.

Step 1: Formation of Pb-Oleate Complex:

-

(1)

Pb(Acetate)2 + 2 OA → Pb(Oleate)2 + 2 HAc ↑.

Step 2: Formation of TOP-Te Complex:

-

(2)

Te + TOP \(\:\underrightarrow{\varDelta\:}\) TOP-Te

The TOP-Te solution is injected into the lead oleate solution at high temperatures between 130 °C and 180 °C. The reaction proceeds immediately, leading to the formation of PbTe QDs through the following reaction:

-

(3)

Pb(Oleate)2 + TOP-Te \(\:\underrightarrow{\varDelta\:}\) PbTe QDs + byproducts

Control over the reaction parameters such as temperature, reaction time, and precursor concentrations is necessary to optimize size, shape, and properties of the resulting PbTe nanocrystals3,31. The presence of OA helps in controlling the growth direction and morphology of the nanocrystals, favoring the formation of desired shapes. It is well known that the ligand plays an essential role in QD-shape formation, and for this reason, we decided to carry out the synthesis with short ligands11.

PbTe QDs synthesis incorporating short-chain ligands

From a literature survey, it was found that QD synthesis with only short ligands failed due to the low solubility of Pb-carboxylate complexes at relatively high temperatures (~ 80 C°)16. Based on these results, we decided to solve this problem and shed some light on this matter. Initially, a synthesis with a short ligand was executed without using OA. However, the attempts to synthesize the QDs with short ligands such as OctA, DA, and LA were unsuccessful. Consequently, we decided to execute the synthesis with different volumetric ratios between the short ligand and the OA ligand. The volumetric ratios of the short ligands to OA were 0.5: 5.5, 1: 5, 1.5: 4.5, 2: 4, and 3: 3.

All analytical techniques were performed as described for the reference synthesis in previous section. It is worth noting that the crystallite structure of all NCs in this study matches that of the reference synthesis. Full XRD analysis of all QDs is provided in Figure S7 and Tables S16–S29. Moreover, the EDS spectra and Pb: Te atomic ratios are mentioned in Figures S2-S6 and Table 1. Similarly, the SAED analysis can be found in Figures S10-S12.

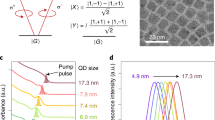

PbTe QDs synthesis with octanoic acid

The synthesis of PbTe QDs with varying ratios of OctA to OA demonstrates a systematic progression in morphological and structural transformations, as revealed by HRTEM (Fig. 3). The initial synthesis, PbTe-OctA0.5/OA5.5 QDs, yields monodispersed cubic particles with an average size of 11.7 ± 1.4 nm. When the OctA: OA ratio is adjusted to 1: 5, the resulting PbTe-OctA1/OA5 QDs display a more diverse morphology, with both cuboctahedral and cubic shapes, averaging 9.9 ± 1.0 nm in size. Increasing the OctA proportion to 1.5: 4.5 produces PbTe-OctA1.5/OA4.5 QDs with a more consistent hexagonal cuboctahedral structure and a mean diameter of 14.7 ± 1.4 nm. This synthesis represents a turning point, indicating the onset of a more defined cuboctahedral morphology. The PbTe-OctA2/OA4 QDs with a 4: 2 acids ratio, show continued trend, reaching an average particle size of 16.0 ± 1.3 nm. Finally, the PbTe-OctA3/OA3 QDs (3: 3 acids ratio) yield a dual-size distribution, combining small and large cuboctahedral particles. The size of large QDs is 15.9 ± 1.6 nm. A schematic representation of the morphology change from cubic to cuboctahedral shape shown in Fig. 3f.

The XRD analysis confirms a well-defined crystalline structure for all PbTe-OctA/OA QDs, providing results consistent with HRTEM and SAED analyses. The alignment of d-spacing and crystallographic planes across these techniques validates the uniformity of the crystallite structure, with findings closely matching the reference synthesis. This congruence between XRD, HRTEM, and SAED analyses reinforces the reliability of the structural characterization across all synthesized QDs. The XRD analysis reveals changes in crystallite sizes — 10.2, 9.1, 10, 11.6, and 10.9 nm — as the volume of the shorter ligand increases. The consistently smaller crystallite sizes observed via XRD compared to HRTEM (Table 2) strongly suggest the presence of an amorphous shell around the crystalline core, confirming morphological evolution and supporting structural changes with varying ligand volumes.

XRD analytical method can only detect the crystal size of crystalline structures32. The measured XRD NCs size for a ratio of 1.5: 3 of the synthesized particles was significantly smaller than the ones measured by HRTEM. It is well known that there could be differences between the two analytical methods33,34. However, the fluctuations in sizes can’t be so significant. As determined by HRTEM, the calculated core for all core-shell structures remained constant at around 8 nm. The shell thickness of 3.0 nm, 3.5 nm, and 4.2 nm was observed for PbTe-OctA/OA QDs of mentioned acid ratios. Based on these results, we may assume that the shell is mostly amorphous.

When EDS analysis was carried out, a higher Pb amount was detected compared to the reference synthesis (Table 1). With the increase in OctA volume, the atomic percentage of Pb also increased. In the last synthesis of PbTe-OctA3/OA3 QDs, a smaller percentage of Pb was observed than the other acid ratios. We assume that this difference results from the high number of small nanoparticles that evolved during the synthesis. EDS analysis concluded that the small nanoparticles contained Pb without any traces of Te (Figure S6). Moreover, the core and the shell of the NCs were analyzed by EDS, and the ratio between Te and Pb was different (Figure S3). The core displayed a ratio of 1: 0.84, and the shell exhibited a ratio of 1: 0.54 of Te to Pb, respectively. This provides strong evidence for the presence of a core-shell structure.

PbTe QDs synthesis with decanoic acid

The opening synthesis in this set of experiments was carried out with DA and OA in volumetric ratios presented in the previous section. The two first synthesized QDs were PbTe-DA0.5/OA5.5 and PbTe-DA1/OA5, and the size calculated by HRTEM was 9.9 ± 1.6 nm and 10.0 ± 1.9 nm, respectively. Their morphology was cubical and mostly mono-dispersed (Fig. 4a, b). Moreover, the morphological change starts at this acids’ ratio (1: 5) and continues to DA1.5/OA4.5 with QDs size of 8.9 nm ± 1.9 nm. In this synthesis, different morphologies can be detected; spherical and cubical shapes (Fig. 4c). The fourth synthesis was DA2/OA4. The QDs were mostly hexagonal/cuboctahedral in shape with an average size around 12.7 ± 1.8 nm (Fig. 4d). A core-shell structure was observed in this synthesis, similar to what was seen with OctA. The final synthesis in this series, DA3/OA3, resulted in cuboctahedral particles with a crystalline core-shell structure. Additionally, a significant number of smaller nanoparticles were observed. The average size of the larger particle population was 10.1 ± 2.4 nm (Fig. 4e).

D-spacings calculated from HRTEM images and SAED analysis are well correlated with the XRD analysis. These results indicate that all the DA/OA NCs have the same crystalline structure closely resembling the reference synthesis, independent of the ligand type utilized in the synthesis. The crystallite sizes calculated from XRD were 10 nm, 5.8 nm, 8.4 nm, 5.8 nm, and 5.1 nm for PbTe-DA0.5/OA5.5, PbTe-DA1/OA5, PbTe-DA1.5/OA4.5, PbTe-DA2/OA4, and PbTe-DA3/OA3 QDs, respectively (Table 2).

To summarize this experimental part, a change in morphology can be detected starting from the 1: 5 ratio of the acids, just like in the OctA. However, the transformation continued through 1.5: 4.5. Only in PbTe-DA2/OA4, we started to detect mono-dispersed hexagonal-cuboctahedral QDs. Be that as it may, the mono-dispersity was ruined in PbTe-DA3/OA3. After the morphology change, the cuboctahedral particles started their growth. However, the PbTe-DA3/OA3 QDs weren’t stable and, after some time, aggregated. EDS analysis demonstrated that in the lowest acid ratios, the atomic ratio between Te: Pb matching the reference (Table 1). With the increase in DA volume, the percentage of Pb also increases. Within the PbTe-DA3/OA3 synthesis, the EDS atomic ratio was 1: 1.45. The lower percentage of Pb in this synthesis, compared to Pb-DA2/OA4 (1: 1.78 of Te: Pb), is attributed to a higher number of evolved small Pb nanoparticles. An increase in the small nanoparticle population, is related to an increase in the amount of the short ligand.

Overwhelmingly, the amorphous shell was observed in a set of DA/OA experiments except for the lowest DA0.5/OA5.5 ratio. Furthermore, the XRD NCs size calculated after the morphology change started, was ~ 8.4 nm, 5.8 nm, and 5.1 nm for PbTe-DA1.5/OA4.5, PbTe-DA2/OA4, PbTe-DA3/OA3, respectively (Table 2). The following results correlate with the core sizes of 8.0 nm, 7.7 nm, and 5.9 nm for the mentioned ratios, respectively. The core sizes were calculated from HRTEM images. The shell thickness was 0.4 nm for DA1.5/OA4.5, 2.5 nm for DA2/OA4, and 2.1 nm for DA3/OA3. The big standard deviation caused by the morphology change led to the odd PbTe-DA1.5/OA4.5 with the 0.4 nm thickness that differs from the trend. In addition, the QD silhouette diameter increased from 10.0 nm to 12.7 nm, with the increase in DA amount; however, the core size decreased.

Another new morphology can be detected in these grids: nanorods (Figures S13 a&b). The structure of the nanorod head and tail was different. The head facets of [200] and [220] and the tail facets of [200] and [222] were detected using the FFT function of the HRTEM image (Figures S13c&d). Moreover, the amorphic shell on the nanorod’s head is also clearly visible in the images. We assume that adding a relatively high amount of DA to the synthesis creates the appropriate environment for the nanorod’s growth. Probably nanorod growth depends on DA volume. Peng et al. demonstrated that the growth of quantum rods starts from a dot shape, where the dot acts as a “seed”. They show that nanocrystals were transformed from quantum dots into quantum rods by significantly increasing the monomer concentration. They claim that the growth of these nanorods is diffusion-controlled35. It is also important to mention that the 4: 2 ratios of DA to OA didn’t work.

PbTe QDs synthesis with lauric acid

In these experiments, we initiated the synthesis by combining LA and OA. Specifically, we employed the mentioned above ratios ranging LA volumes from 0.5 to 1.5 mL. The resulting QDs sizes were 11.3 ± 1.5 nm and 11.6 ± 1.6 nm, and 10.4 ± 1.6 nm for LA0.5/OA5.5, and LA1/OA5, and LA1.5/OA4.5, respectively (Fig. 5). First, two synthesises displayed a cubic shape, with truncated cubes as secondary forms. However, the last synthesis in the series was unstable and polydispersed. No core-shell particles were detected on the grid. In addition to cubes and truncated cubes, we could detect a high amount of small spherical nanoparticles (Table S15). The synthesis of LA1.5/OA4.5 was very unstable in comparison to all the other short ligands. The resalted QDs solution was transparent with a relatively low yield compared to Pb-OA QDs (Figures S8a&d). The two ratios of 2: 4, and 3: 3 didn’t work.

The EDS measurements showed a ratio of 1: 0.8 of Te: Pb in all the synthesized NCs (Figure S5 and Table 1). The lead atomic percentage was dramatically lower compared to the reference synthesis. The XRD NCs’ sizes were 8.8, 10.0, and 11.5 nm. With XRD analysis in sight, we could detect a slight increase in the NCs’ size from ~ 9.0 to 11.5 nm. However, the various shapes and sizes Make it hard to derive the same conclusion from the HRTEM imaging. It is easily seen that with the increase in LA volume, the particles are more dispersed in size and shape. All LA-synthesized QDs showed the same phenomenon of small nanoparticle formation, just like all the other ligands. Therefore, the small particles grow bigger with the increase in LA concentration. In the last synthesis, the growth of small spherical nanoparticles reached a new height of 3.1 ± 1.0 nm. From EDS analysis, it has been concluded that the small nanoparticles are Pb nanoparticles without Te traces (Figure S6). Because of high oxygen contamination, it is hard to detect the exact number of oxygens36. The only source of oxygen in our synthesis is the Tri-octyl-phosphine oxide (TOPO); TOP contamination. From this data, we can assume that the Pb nanoparticles are Pb-oxide species. As a result of this synthesis instability, we couldn’t synthesize the QDs in acid ratios of 2: 4 and 3: 3. Hence, we couldn’t determine the proper ratio for the complete morphology change. The mentioned synthesized ratios aggregated quickly, and no particles could be savored. The LA concentration does not play a role in the atomic ratios of Pb to Te; it stayed the same for all synthesized QDs in this series, 1: 0.8 of Te: Pb. Nonetheless, the lead amount was lower compared to the reference synthesis. This can be explained by the larger population of spherical lead nanoparticles mentioned earlier.

XPS was used to study the elements’ elemental compositional and chemical oxidation states in the PbTe QDs. A complete XPS survey can be found in Figure S14. The high-resolution spectra of Pb-4f and Te-3d are represented in Figs. 2 and 6, S15-S16, for reference, OctA, DA, and LA, respectively. A surface (60 s) and a core (300 s) analysis were carried out in all cases. The results show that all Pb-4f7/2 peaks are centered around 137–138 eV, and the Pb-4f5/2 are centered around 142–143 eV. The reference synthesis as well as DA showed only Pb0 peaks correlated to Pb-metal. However, in OctA and LA a shoulder can be detected, which represents a Pb2+ peak, usually correlated to PbO. The most exciting result in this case is the ratio between the intensities of Pb0 and Pb2+ that can be determined in surface and core level measurements. The Pb-4f5/2 and pb-4f7/2 metal peaks are higher than the oxides in all surface measurements. However, in core level measurements, the oxide peaks grow and their intensity increases, indicating that the core is composed of PbTe oxide spices. In addition, the increase in LA is even higher than the metal; it may be explained by the small nanoparticle population composed of PbO. Further XPS analysis shows Te-3d3/2 and Te-3d5/2 peaks centered at 585–586 eV and 575–576 eV binding energies. In surface level measurements, higher peaks of oxides can be detected; after depth measurements of the core, the amount of Te0 increases. We should also mention that the intensity of metal Te is higher for OctA and LA at a core level.

Furthermore, the depth analysis for all the ligands is shown in Figure S17. We can conclude from the complete XPS analysis that changes in the carbon layer vary from sample to sample depending on the QD shell. The carbon percentage plot shows a moderate decline in samples with a core-shell structure, indicating that the shell is primarily amorphous and contains the ligands. In contrast, the reference sample, as well as the LA sample, exhibits a more drastic decrease in carbon, consistent with mostly crystalline QDs. This behavior aligns with a structure where the ligands form a thin shell on the surface of the nanocrystals. Additionally, all samples show surface contamination with oxygen, and the surface level was determined after 60 s of depth profiling to account for this.

An HNMR was performed to confirm the binding of the ligands to the QDs surface. When synthesizing the NCs using only OA as a ligand, the integration of the vinylic hydrogens and α hydrogens adjacent to the acid moiety aligns well with OA. This is illustrated by a 1:1 ratio, where each peak corresponds to two hydrogens, as depicted in Figure S18. Contrastingly, in the spectrum of particles synthesized with both OA and DA as ligands, the ratio between these peaks shifts to 1:11 (Figure S19), indicating a ratio of 1:10 for OA to DA. Evidence for ligands binding to the NCs can be obtained from the disappearance of the carboxylic peak of the acids around 8.5 ppm and the broadening of the vinylic peak at 5.34 ppm since the double bond of the acid is affected by the chemical surroundings of the NCs24. Figures S20-S21 represent the HNMR for pure OA and DA, respectively.

To summarize, the synthesis fails and aggregates at volumetric ratios higher than 3: 3 of the short ligands to OA. Even when the synthesis occurs in a 3: 3 ratio, the yield is low, and a relatively high amount of precipitant was observed (Figure S8). The stability of PbTe QDs was evaluated both immediately after synthesis and after two years of storage in hexane solvent for PbTe-OA, PbTe-OctA2/OA4, and PbTe-DA2/OA4 QDs. The results indicate that the QDs exhibit remarkable long-term stability, maintaining consistent shape and size distribution. The HRSTEM images show that the particles remain highly monodispersed over time, with no significant aggregation or morphological changes (Figure S22). This demonstrates the robustness of the QDs, confirming their suitability for applications requiring long-term stability. The EDS Pb: Te atomic ratios depend on the short ligand utilized in the synthesis. In OctA and DA acids, the Pb atomic percentage was higher compared to the reference synthesis. However, in LA, the Pb atomic percentage was significantly lower. The highest Pb percentage was found in PbTe-OctA/OA QDs. We observed that the shorter the ligand, the thicker the shell. This led us to believe that the shell is the main reason for particle growth (above 10 nm) and morphology change. The NCs’ shell thickness might be a possible explanation for the higher Pb percentage in the NCs.

According to XRD analysis, the same crystal structure was observed for all sets of experiments, including the reference synthesis. The crystallite structure, as was mentioned above, was cubic with an Fm-3m space group. The observed NCs’ sizes become smaller after the morphology change for OctA and DA. The sizes of the NCs in LA were consistent with TEM analysis. We can conclude that the higher the number of facets, the more intricate the morphology (cuboctahedral and truncated cubes). The same QD morphology, cuboctahedron, was obtained for OctA and DA in a 2: 4 volumetric ratios. It is also important to mention that this was the most stable synthesis for both acids. Figure 7 and Figure S9 demonstrates the correlation between the volumetric ratios and the diameter. The plot describes a drop in size after different volumetric ratios for the acids; this drop is correlated to the point of the morphology change. In a 1: 5 ratio, it is straightforward to conclude that the morphology of OctA changed rapidly. The second short ligand was DA, and the size drop occurred at a 1.5: 4.5 volumetric ratio. Compared to these two short ligands, we couldn’t determine the drop point for LA. However, we can define a linear regression in the particle size of PbTe-LA/OA QDs. It is easy to conclude that the morphology changes and growth of the new shape happened only after the cubical size drop. Additional information can be found in the supporting information (SI).

Conclusions

This work, for the first time, presents a modified method for PbTe NCs synthesis using a combination of OA and short ligands (OctA, DA, and LA) as capping agents. Current study presents a novel, tunable method for producing large spherical PbTe QDs, challenging the natural tendency of these QDs to adopt cubic shapes at sizes above 10 nm. Our findings demonstrate how short ligands influence the size and shape of PbTe QDs, achieving cubooctahedral QDs up to 16 nm. This work highlights that the shape transformation involves the disruption of QDs crystallinity, leading to the formation of PbTe QDs with a crystalline core and an amorphous shell. Key observations include: (A) At low ligand concentrations (up to ~ 0.5 mM), OA controls QD morphology, resulting in cubical shapes. (B) At molar ratios of 0.5-1, short ligands dominate, producing various morphologies. (C) A 1:1 molar ratio of short ligands to OA yields the best results for spherical, monodispersed QDs. (D) Molar ratios exceeding 1:1 result in unstable or ineffective synthesis (all molar ratios can be found in SI). The study indicates that even shorter ligands and lower ratios could further refine morphology control. This research addresses a critical gap in the literature by introducing a controllable synthesis method that enables the production of large spherical PbTe QDs with precisely adjustable sizes. The reproducible synthesis method developed here is valuable for tuning PbTe QDs for various applications. Additionally, the discovery of a core-shell structure offers new insights into nanoparticle design. However, the absence of cubical QDs with short ligands points to the need for further mechanistic studies to understand QD formation. This work has significant potential for layer fabrication in electronic, optoelectronic, and energy applications, though additional systematic studies are necessary to optimize these processes.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Should any raw data files be needed in another format they are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Harrison, M. T. et al. Colloidal nanocrystals for telecommunications. Complete coverage of the low-loss fiber windows by mercury telluride quantum dots. Pure Appl. Chem. 72, 295–307 (2000).

Shuklov, I. A. & Razumov, V. F. Lead chalcogenide quantum dots for photoelectric devices. Rus. Chem. Rev. 89, 379–391. https://doi.org/10.1070/rcr4917 (2020).

Miskin, C. K. et al. Lead Chalcogenide nanoparticles and their size-controlled self-assemblies for thermoelectric and photovoltaic applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2, 1242–1252. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.8b02125 (2019).

Haciefendioglu, T. & Asil, D. PbTe Quantum dots and Engineering of the Energy Band Alignment in Photovoltaic Applications. Süleyman Demirel Üniversitesi Fen Edebiyat Fakültesi Fen Dergisi. 16, 434–443. https://doi.org/10.29233/sdufeffd.891908 (2021).

Wu, S., Cheng, L. & Wang, Q. Excitonic effects and related properties in semiconductor nanostructures: roles of size and dimensionality. Mater. Res. Express. 4 https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/aa81da (2017).

Murphy, J. E. et al. PbTe colloidal nanocrystals: synthesis, characterization, and multiple exciton generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 3241–3247. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja0574973 (2006).

Lin, Z. et al. PbTe colloidal nanocrystals: synthesis, mechanism and infrared optical characteristics. J. Alloys Compd. 509, 5047–5049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2011.02.028 (2011).

El-Rabaie, S., Taha, T. A. & Higazy, A. A. Characterization and growth of lead telluride quantum dots doped novel fluorogermanate glass matrix. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 30, 631–635. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mssp.2014.11.006 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Facile assembly of size- and shape-tunable IV-VI nanocrystals into superlattices. Langmuir 26, 19129–19135. https://doi.org/10.1021/la103444h (2010).

Mokari, T., Zhang, M. & Yang, P. Shape, size, and assembly control of PbTe nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 9864–9865. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja074145i (2007).

Urban, J. J., Talapin, D. V., Shevchenko, E. V. & Murray, C. B. Self-assembly of PbTe quantum dots into nanocrystal superlattices and glassy films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 3248–3255. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja058269b (2006).

Shrestha, A., Spooner, N. A., Qiao, S. Z. & Dai, S. Mechanistic insight into the nucleation and growth of oleic acid capped lead sulphide quantum dots. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 14055–14062. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6cp02119k (2016).

Murray, C. B., Noms, D. J. & Bawendi’, M. G. Synthesis and Characterization of Nearly Monodisperse CdE (E = S, Se, Te) Semiconductor Nanocrystallites, (1993). https://doi.org/10.1021/ja00072a025

Pan, Y. et al. Size controlled synthesis of monodisperse PbTe quantum dots: using oleylamine as the capping ligand. J. Mater. Chem. 22, 23593–23601. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2jm15540k (2012).

Guglielmi, Y., Cappa, F., Avouac, J. P., Henry, P. & Elsworth, D. Seismicity triggered by fluid injection-induced aseismic slip. Science 348, 1224–1226. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab0476 (1979).

Liu, T. Y. et al. Non-injection and low-temperature approach to colloidal photoluminescent PbS nanocrystals with narrow bandwidth. J. Phys. Chem. C. 113, 2301–2308. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp809171f (2009).

Niu, J. et al. Controlled synthesis of high quality PbSe and PbTe nanocrystals with one-pot method and their self-assemblies. Colloids Surf. Physicochem Eng. Asp. 406, 38–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colsurfa.2012.04.046 (2012).

Bealing, C. R., Baumgardner, W. J., Choi, J. J., Hanrath, T. & Hennig, R. G. Predicting nanocrystal shape through consideration of surface-ligand interactions. ACS Nano. 6, 2118–2127. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn3000466 (2012).

Jin, H., Choi, S., Lee, H. J. & Kim, S. Layer-by-layer assemblies of semiconductor quantum dots for nanostructured photovoltaic devices. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 2461–2470. https://doi.org/10.1021/jz400910x (2013).

Lee, T. G. et al. Controlling the dimension of the quantum resonance in CdTe quantum dot superlattices fabricated via layer-by-layer assembly. Nat. Commun. 11 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-19337-0 (2020).

Ko, Y., Kwon, C. H., Lee, S. W. & Cho, J. Nanoparticle-based electrodes with high charge transfer efficiency through Ligand Exchange layer-by-Layer Assembly. Adv. Mater. 32 https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202001924 (2020).

Sousa, V. et al. Kolen’ko, high Seebeck coefficient from screen-printed Colloidal PbSe nanocrystals Thin Film. Materials 15 https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15248805 (2022).

Cadavid, D. et al. Influence of the Ligand stripping on the Transport properties of nanoparticle-based PbSe nanomaterials. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 3, 2120–2129. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACSAEM.9B02137 (2020).

Peters, J. L., De Wit, J., Vanmaekelbergh, D., Curve, S. & Coefficient, A. Surface Chemistry, and Aliphatic Chain structure of PbTe Nanocrystals. Chem. Mater. 31, 1672–1680. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b05050 (2019).

Lu, W., Fang, J., Stokes, K. L. & Lin, J. Shape evolution and self assembly of monodisperse PbTe nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 11798–11799. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja0469131 (2004).

He, J., Xia, Y., Naghavi, S. S., Ozoliņš, V. & Wolverton, C. Designing chemical analogs to PbTe with intrinsic high band degeneracy and low lattice thermal conductivity. Nat. Commun. 10 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08542-1 (2019).

Bauer Pereira, P. et al. Lattice dynamics and structure of GeTe, SnTe and PbTe. Phys. Status Solidi B Basic. Res. 250, 1300–1307. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssb.201248412 (2013).

Nithiyanantham, U., Ozaydin, M. F., Tazebay, A. S. & Kundu, S. Low temperature formation of rectangular PbTe nanocrystals and their thermoelectric properties. New J. Chem. 40, 265–277. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5NJ02113H (2016).

Davis, B. J. Growth, Characterization and Assembly of Lead Chalcogenide Nanosemiconductors for Ionizing Radiation Sensors, The University of Michigan, (2022). https://doi.org/10.7302/4753

Koole, R. Fundamentals and Applications of Semiconductor Nanocrystals. A study on the synthesis, optical properties, and interactions of quantum dots, (1980). https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/30548

Liu, H. et al. Near-infrared lead chalcogenide quantum dots: synthesis and applications in light emitting diodes. Chin. Phys. B. 28 https://doi.org/10.1088/1674-1056/ab50fa (2019).

Bunaciu, A. A., Udriştioiu, E., Aboul-Enein, H. Y. & Diffraction, X-R. Instrumentation and applications. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 45, 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408347.2014.949616 (2015).

O’Connell, K. & Regalbuto, J. R. High sensitivity Silicon Slit detectors for 1 nm powder XRD size detection limit. Catal. Lett. 145, 777–783. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10562-015-1479-6 (2015).

Jensen, H. et al. Determination of size distributions in nanosized powders by TEM, XRD, and SAXS. J. Exp. Nanosci. 1, 355–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/17458080600752482 (2006).

Peng, Z. A. & Peng, X. Mechanisms of the shape evolution of CdSe nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 1389–1395 (2001). https://pubs.acs.org/doi/full/10.1021/ja0027766 (accessed July 24, 2024).

Pan, W., Johnson, E. R. & Giammar, D. E. Lead Phosphate Particles in tap water: challenges for Point-of-use filters. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 8, 244–249. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.1c00055 (2021).

Acknowledgements

SL and AB are thankful to Ariel University for a Ph.D. fellowship. AS is grateful to Ariel University for a postdoctoral fellowship.

Funding

The research was partially funded by Arbel Energy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Svetlana Lyssenko: Methodology, Conceptualization, Validation, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. Michal Amar: Methodology, Investigation, Writing. Alina Sermiagin: Validation, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing. Ayan Barbora- Methodology, Formal analysis. Refael Minnes: Conceptualization, Methodology, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lyssenko, S., Amar, M., Sermiagin, A. et al. Tailoring PbTe quantum dot Size and morphology via ligand composition. Sci Rep 15, 2630 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86026-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86026-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

One pot synthesis of klockmannite CuSe nanoparticles for supercapacitors and the electrolyte role

Scientific Reports (2025)