Abstract

Each treatment cycle of radiopharmaceutical therapy (RPT) is administered as a single dose. We aimed to investigate a personalized metronomic RPT paradigm, employing multiple lower-dose administrations, to evaluate its effect on delivering radiopharmaceuticals to tumors. We developed a physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model applied to metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients to analyze the impact of metronomic framework and various infusion durations (1–4 h) on absorbed doses (ADs) in tumors and organ-at-risk (OAR). We designed a treatment algorithm to select optimal regimens with high AD, while investigating what we term radiopharmaceutical delivery payload (RDP). This metric evaluates the efficiency of radiopharmaceutical delivery by quantifying the proportion of the administered dose that successfully reaches the target tissue. The goal is to optimize trade-offs between RDP and tumors-AD among injection profiles, amongst varying radioactivity (1-22GBq), total radiopharmaceutical mass (25-210nmol), number of injections (2–6), and time intervals (12–36 h) between injections. Our framework applied to five patients led to increased AD between 2 and 358 Gy (between 2 and 146%) higher than normally administered to patients, safeguarding OARs. Using single-dose scenarios to match ADs in metronomic approach, led to significant increase in injected activities, requiring injection of 0 to 9GBq additional activity (reducing RDP by 3–75%). Maintaining total administered radioactivity within clinically therapeutic levels, increasing frequency, time interval, and infusion duration increases tumors and OARs AD by 0.05-73%, while it decreased tumors-to-OARs AD ratios by 0.1–30%. Based on the PBPK modeling approach, metronomic RPT appears to improve efficacy (RDP) in delivered doses to tumors for a given total injected radioactivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Radiopharmaceutical therapy (RPT) is emerging as a very promising paradigm in cancer treatments via selective targeting of tumors while minimizing damage to healthy tissue1. Meanwhile, the theranostic paradigm allows imaging of the same targets as treated by RPT2,3. As an example, pharmaceuticals can be labeled with positron (e.g., 68Ga, 18F) or gamma (e.g., 111In) emitters for imaging, and with beta (e.g., 177Lu) or alpha emitters (e.g., 225Ac) for treatment of previously staged tumors4. This enables pre-, intra- and/or post-RPT imaging of tumors and organs-at-risk (OARs).

Like conventional chemotherapy5, present-day RPT involves single administrations of a radiopharmaceutical to all patients in a given therapy cycle. However, while researchers aim to enhance tumor targeting by increasing this amount, it also raises the absorbed dose (AD) to healthy organs. While effective, this approach can lead to significant toxicity due to high radiation doses delivered over a short time, potentially limiting its efficacy and tolerability in some patients. Developing techniques that increase the tumor-AD without increasing the administered activity has the potential to significantly improve RPT outcomes. Interestingly, metronomic chemotherapy, has shown potential as a viable approach in cancer treatment. This approach as a low-dose (i.e., the amount or quantity of medication administered during each instance of treatment), long-term, repeatedly administered method has been used as an alternative regimen to conventional chemotherapy6,7, and has demonstrated inhibitory effects on cancer and a positive influence on the quality of life of patients8. Motivated by these findings, in the present work, we aim to assess the effect of a metronomic approach to RPT compared to common single-dose RPT.

We focus on RPT of prostate cancer, the most prevalent type of cancer amongst men. The majority of deaths from prostate cancer are attributed to metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC), which is characterized by extensive metastases throughout the body9. Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is a protein that is physiologically expressed in prostatic tissue and located on the cell surface, with 100 to 1000 times upregulated expression in prostate cancer and mCRPC cells compared with normal prostate cells10. Because of its overexpression in prostate cancer, this protein is known as a biomarker. It has been demonstrated that many entities can successfully target PSMA, including monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and low-molecular-weight (LMW) peptides, which are capable of binding to PSMA receptors on the surface of cancerous cells11. As a result, targeting PSMA receptors with these entities has become a major focus of RPT research.

A crucial aspect of treatment planning is selecting the optimal amount of radiopharmaceutical, comprising both labeled and unlabeled peptides to administer, avoiding the creation of a toxic environment in the body due to the unwanted radiation12,13. In order to prevent over- and under-treatments, personalized therapy should be considered for a specific patient, which requires pharmacokinetic data of each patient14. Molecular imaging techniques such as positron emission tomography (PET), planar gamma-camera imaging, or single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), provides a noninvasive way to visualize the distribution of radiopharmaceuticals in the body and measure biological processes. With the use of mathematical modeling, computational models can be created of a patient (e.g., virtual patient15) which allows researchers to simulate different treatment regimens with the goal of increasing safety and efficacy. This involves fitting pharmacokinetic (PK) models to the acquired data and personalizing the model. This approach enables the development of a PK model tailored to the specific physiology of each patient.

Computational models are capable of accurately estimating the biodistribution of therapeutics to assure patient safety and effectiveness of therapy. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models are powerful computational tools for assessing important pharmacokinetic parameters and estimate the concentration of radiopharmaceuticals in each organ. This information can the used to calculate the AD to each organ16,17,18. As these models are based on the physiology of the OARs as well as the pathophysiology of tumors19, they can facilitate the development of accurate and personalized treatments. In essence, a PBPK model describes the behavior of radiolabeled substances by considering the main physiological processes, such as administration, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME)16,20,21,22.

In this work, we developed a PBPK model with twenty-one compartments, including two separate tumors and one compartment representing all other tumor lesions, to study the effects of 177Lu-labeled PSMA peptides on mCRPC patients. We conducted in-silico analyses to investigate the effects of a metronomic RPT approach and various infusion durations on AD of tumors and OARs. We have defined a parameter called radiopharmaceutical delivery payload (RDP) to tumors, which is determined by the ratio of the combined time-integrated activity (TIA) of tumors to the TIA of the total administered activity during the treatment cycle. This parameter reflects the proportion of administered labeled peptides that are decaying within the tumor and affecting tumor cells, serving as an indicator of treatment effectiveness. In clinical trials, the relevance of this parameter extends to efficacy. The RDP helps assess treatment efficacy by indicating how tumor TIA, and consequently the tumor-AD, varies for a specific amount of administered activity with and without metronomic approach. Additionally, to evaluate safety in clinical trials, the AD to OARs is monitored simultaneously. To select the best treatment regimen that balances RDP and total tumors AD, we designed a treatment algorithm which considered the kidney and salivary gland as OARs, and varied the activity (1-22GBq), total amount of administered radiopharmaceutical (\(\:{2}^{5}-{2}^{10}\)nmol), number of injections (2-6), and time interval (12–36 h) between injections, aiming to maximize the AD to tumors while minimizing adverse effects.

Materials and methods

Creating virtual patient

PBPK modeling

A PBPK model, consisting of twenty-one compartments, was designed in Simbiology/MATLAB (MATLAB R2019b, The MathWorks, Inc) as depicted in Fig. 1. The model encompasses all physiologically and physically relevant mechanisms in the human body, such as blood flow between connected organs, plasma protein binding, nonlinear PSMA-specific association, internalization, excretion, the release of 177Lu from cells, and its physical decay (equation (S1-S13), and Fig. S1 in supplementary materials). The model includes two discrete circulatory systems, one for labeled and one for unlabeled peptides, and considers the competition for binding to free receptors of equivalent affinity. Furthermore, the systems are integrated through the physical decay of the radioactive substance. A comprehensive elaboration of the model and parameters (Tables S1 and S2) is provided in the supplemental (Part 1).

Personalization of the model

Personalizing the model requires both measurement and estimation of various parameters. Parameters such as volume of tumors, kidney, and salivary glands, tubular excretion rate (TER), and body surface area (BSA) need to be measured. On the other hand, a number of parameters need to be estimated, including [RSAL,0], [RK,0] and [RTU,0]; i.e. binding site densities, and λSAL, release, λK, release and λTU, release; i.e. release rates, for salivary glands, kidney and tumors respectively, background corrections for tumor 1 and 2 (\(\:{c}_{1}\:\)and \(\:{c}_{2}\)) (ROITumor = c muscle + tumor) which indicate the quantity of labeled peptides in muscle that impacts tumors, and fSAL; i.e. perfusion of salivary glands, using data points from time-activity curves acquired through \(\:\gamma\:\)-camera images in the initial treatment cycle. Estimation details are provided below.

Pre- and intra-RPT imaging

In clinical practice, PSMA PET/CT imaging is used to affirm the expression of PSMA in tumors and metastatic lesions, thus facilitating the diagnosis of prostate cancer and identifying metastatic lesions distributed throughout the body. We use this information as part of the personalization of the model. Table S1 includes the data obtained by Kletting et al.17 from 68Ga PSMA PET/CT imaging of 5 mCRPC patients, which was used to determine the appropriate amount of 177Lu-PSMA I&T for clinical injection. After injection of 177Lu-PSMA I&T, Kletting et al.17 performed 4–5 times imaging during therapy using a \(\:{\upgamma\:}\)-camera at various time points (0.5 h, 2 h, 1 d, 2 d, 3 d post-injection for P1,P2, and P5, 0.5 h, 2 h, 1 d, 4 d for P3 and 0.5 h, 2 h, 1 d, 2 d, 5 d for P4) (Fig. S2), and this data was used to estimate individual parameters by fitting the model to the amount-time data.

Parameter estimations

Since the \(\:{\upgamma\:}\)-camera images obtained from patients during therapy are not accessible, we extracted 5 data points from diagrams provided by Kletting et al.17 (Fig. S2) using the GetData Graph Digitizer software (available at getdata-graph-digitizer.com). The individual model parameters were estimated by fitting our PBPK model to the extracted data via nonlinear regression and nonlinear least squares optimization. The method is based on minimizing sum of squares of the residuals between the model and the data using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm (Simbiology Model Analyzer). The difference between the fitted time activity curve TAC and the data points acquired from γ-camera imaging was assessed using Mean Squared Error (MSE), Sum of Squared Errors (SSE), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), calculated using equations S14-S17. MSE and SSE assess the proximity of model predictions to observed data, whereas AIC and BIC strike a balance between model fit and complexity, facilitating model selection. AIC and BIC penalize models with more parameters to prevent overfitting. Log-likelihood evaluates the likelihood of observed data given the model parameters, essential for parameter estimation. These metrics collectively inform the processes of model fitting, selection, and parameter estimation in Simbiology.

Mathematical modeling

Biodistribution simulations and AD

The therapeutic impact from 177Lu-PSMA radiopharmaceutical treatment was calculated as AD by integration over 30,000-min post-injection for relevant organs, including the two tumor lesions, the tumor residual, the kidney, and salivary glands based on the MIRD formalism (equations (S18-23), Table S3, and S4 in supplementary materials (Part 2))20. This duration corresponds to about 3.13 half-lives of 177Lu, by which time the majority of the radiopharmaceutical has decayed and been cleared from the body, making further contributions to the absorbed dose negligible14,16,17,19.

Designing treatment algorithm considering critical AD for OARs

The procedure of injection profile selection for treatment planning involves two main phases, as shown in Fig. 2. The primary phase involves the selection of the maximum activity in the range of 1 to 22 GBq for each considered total amount of administered radiopharmaceutical (\(\:{2}^{5}-{2}^{10}\) nmol) at each specified injection profile, which consists of varying numbers of injections (2, 4, or 6) and intervals between injections (12, 24, or 36 h). This selection is predicated upon the critical AD for the potentially dose-limiting organs (8 Gy for kidney23 and 7.5 Gy for salivary glands17 in each treatment cycle). Thus, for each profile and for each total amount, the maximum activity which is safe to inject is selected. Subsequently, the ratio of the summation of TIA of the tumors to the TIA of the total administered activity in that treatment cycle is calculated using Eq. (1) which we denote as “radiopharmaceutical delivery payload” (RDP) (supplementary materials (part 2, equation (S24), Fig. S3)). The TIA of total activity injected is referred to an ideal scenario where all the administered activity is effectively localized within the tumor, with its therapeutic effect only declining due to radioactive decay and not due to clearance from the body. Increase in RDP correspond to a higher proportion of the injected radiopharmaceutical reaching the tumor.

Where N is number of tumor compartments, i refers to each tumor compartment, \(\:TI{A}_{i}^{Tu}\) represents the time-integrated activity for tumor i, and \(\:{TIA}_{{A}_{0}}\) represents the time-integrated activity for the injected radiopharmaceutical. To determine the optimal injection profile in the second phase of treatment algorithm, the Pareto front approach was taken into consideration. The Pareto front method identifies a set of profiles where no profile can be improved in terms of parameters (such as AD or RDP) without negatively affecting another parameter. Essentially, it illustrates the best possible trade-offs between conflicting parameters and aids in finding a spectrum of optimal profiles. In the context of our problem with AD and RDP, the Pareto front curve represents the optimal trade-offs between these two parameters. Due to the dissimilarity in units for these two parameters, normalization was performed to ensure that all parameters were on a common scale, which enabled profile comparison. Using this approach, point A is considered to dominate point B, if A has higher value than B in at least one parameter and no lower value in any other parameter. For example, point A dominates point B if it has both higher AD and RDP, or if it has equal AD and higher RDP, or if it has equal RDP and higher AD.

Metronomic RPT: mechanism, impact on tumor-to-OARs AD ratio, and administration duration effect

To identify the reasons behind the difference in AD between metronomic and single-dose injection approaches an analysis was performed which focused on examining the temporal variation in the quantity of labeled peptides present in different sub-compartments. Sub-compartments refer to the vascular compartment, extracellular compartment, compartment representing receptors on the cell membrane, unspecific binding compartment, and intracellular compartment, which together represent an organ. To model each organ, we used a combination of these compartments based on the physiology of each organ.

First, the impact of dividing clinically injected therapeutics into 2, 4, and 6 equal doses and administration with different time intervals (12 h, 24 h, and 36 h) on AD and tumors-to-OARs AD ratio was analyzed for all patients. The second step of the evaluation involved using our PBPK model to investigate the impact of injection frequencies and time intervals between administrations on presence of labeled peptides in sub-compartments which affect tumors and OARs AD as determined by formulas (S17-20) in supplementary materials. This calculation considers the fraction of labeled peptides bound to serum proteins in blood flow, as well as the portion of peptides in the vascular and interstitial spaces of the muscles and tumor lesions, and those attached to the receptors on the cancer cells and internalized within them. Additionally, the effect of administering the radiopharmaceutical with different durations of infusion (such as bolus injection, 1, 2, 3, and 4 h) on the tumors’ AD and tumor-to-OARs AD ratio was also analyzed.

Results

Parameter estimation and model validation

Fitting of the designed PBPK model to data acquired from \(\:\gamma\:\)-camera imaging (Fig. S2) results in estimation of individual parameters for five patients (Figs. S4-S8 and Tables S5-S9). The discrepancy between the fitted Time Activity Curve (TAC) and the data points obtained from \(\:\gamma\:\)-camera imaging was quantified using MSE, SSE, AIC, and BIC which yielding average values of \(\:2.4\times\:{10}^{-11}\), \(\:1.53\times\:{10}^{-10}\), \(\:-439\), \(\:-430\), and Log-Likelihood of \(\:230\:\)among all patients, respectively. Additionally, the outcome of the designed PBPK model were visually compared with the data presented by Kletting et al.17 for all 5 patients (Fig. S2).

Limited amount activity curves for OARs

For each injection profile and the total amount of radiopharmaceutical considered, the maximum safe (Kidney AD < 8 Gy and salivary gland AD < 7.5 Gy) and achievable (i.e., the maximum activity that can be obtained for a certain amount of total administered radiopharmaceuticals) amount of injected activity is selected. This selection is made under the restriction imposed by limited amount-activity curve (LAAC) of kidneys and salivary glands. The term LAAC refers to an iso-contour that visualizes the critical AD to OARs (kidneys and salivary glands) in a two-dimensional plot, based on the total amount and activity of the radiopharmaceutical injected. To visualize the relationship between the total amount and activity of the administered profiles, the AD contour is plotted (Fig. 3, S9, and S10). Additionally, the renal and salivary gland LAAC are depicted by a purple iso-contour. Each gridline intersection within the contour represents a distinct injection profile. In the initial phase of the treatment algorithm, among the set of injection profiles which are under the LAACs, the maximum activity is selected for each specific total amount of radiopharmaceutical, and subsequently, RDP is computed. Figure 3a and b show these contours for second patient and for two doses with 24 h time interval profile, which for total amounts of \(\:{2}^{5}\)-\(\:{2}^{10}\) nmol determine the maximum activity to be 5, 5.4, 5.4, 5.4, 13, and 18 GBq, respectively. The findings for various administration frequencies and time intervals for patient two are illustrated in Figures S9 and S10. The same procedure applied for each patient.

To determine the maximum safe amount of administered radiopharmaceutical, AD contours for (a) kidney and (b) salivary glands are plotted for different combination of total injected amount of radiopharmaceuticals on the x-axis and its radioactivity on the y-axis, considering two injections with a 24-hour interval for patient two. The total amount of radiopharmaceutical represents the combined quantity of labeled and unlabeled peptides in nmol, while radioactivity indicates the amount of labeled peptides in GBq. Each gridlines intersection represents the AD (Gy) for a specific total amount of radiopharmaceutical with its corresponding activity. Purple (critical AD for OARs) isocontours indicate OARs constraint limited amount-activity curve (LAAC). Detail for other injection times and time intervals represents in supplementary materials (Figs.S9 and S10).

Quantification of the delivery efficacy of injected activity

To monitor the injected activity alongside the tumor AD, a subsequent phase of the algorithm was implemented which uses calculated RDP and AD to find trade-off between them. It is crucial to strike a balance between AD and RDP to select the best profile with a small injected activity while maximizing AD. We have summarized all the profiles with highest activity which are safe for OARs and achievable in Figs. S11, 4, and S12 to S14, corresponding to patients 1 to 5, respectively, providing visual representations of their AD and RDP values. These figures help to show the effectiveness and safety of various profiles for each patient. The purple curve indicates the RDP and bar chart shows AD in each injection profile for tumor 1, 2, tumor rest, and total tumors AD.

Using the metronomic approach, the total tumor AD, which is the sum of AD to each tumor compartment, ranged from 44 to 601 Gy (Fig. S15a), with an increase associated with higher A0 values, more frequent administrations coupled with extended intervals between injections. The payload of the radiopharmaceutical delivery ranged from 0.23 to 5.53% (Fig. S15b), showing a similar trend of increase with a greater number of injections and longer intervals. Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that RDP not only depends on A0, but also depends on total amount of injected radiopharmaceutical. A twofold increase in total injected radiopharmaceutical results in a notable decrease in specific activity (the ratio of labeled peptide to total amount of labeled and unlabeled peptides) ranging from 23 to 0.4%. This reduction in specific activity results in a reduced RDP for tumors and OARs due to more binding of unlabeled peptides to receptors. On the other hand, with an increase in the total administered radiopharmaceutical, the quantity of injected labeled peptides also rises, leading to an evident increase in AD to tumors and OARs. However, when the total amount remains constant across different profiles, the frequency and time intervals apply a significant influence on the RDP (Figs. S11a, 4a, S12a to S14a).

Implementing the Pareto Front method for metronomic profiles resulted in the selection of profiles that have higher values of either AD or RDP compared to other profiles, without simultaneously having lower values in both AD and RDP. This is clearly illustrated by the Pareto Front curves shown in Figs. S11b, 4b, S12b-S14b, corresponding to patients 1 through 5, respectively. Point 1 on the Pareto front curve represents the profile with the highest RDP, however, as one progresses along the Pareto front curve towards its last point, there is a trade-off observed: an increase in AD from 7 to 375 Gy and a simultaneous decrease in RDP by from − 1% to -75% because of increase in A0 from 0.4 to 16 GBq.

Our treatment algorithm for patients 1–5 proposed injection of A0 varied between 1 and 21GBq which results in a 2–146% rise in AD which is about 2–358 Gy compared to typical normal one size fit all dose, administered to patients (5.4-6 GBq) (Figs. S11a, 4a, S12a to S14a). To achieve a similar cumulative dose level as the metronomic regimen for tumors, using single-dose profile requires an additional 0–9 GBq of activity to be injected which decreasing the RDP by approximately − 3% to -75% (Fig. S15a). Moreover, adopting a personalized single-dose profile can alter AD by approximately − 14–48% when compared to metronomic profiles, but it requires injection of activity up to 11 GBq more than metronomic profiles demonstrating its impact on reducing the RDP within the range of -53–3% (Fig. S15). This emphasizes the importance of carefully selecting an appropriate infusion profile that balances the need for maximum impact on the tumor lesions and minimizing adverse effects.

Selection of optimal injection profiles using Pareto Front curve (a) Selecting optimal injection profile by finding a trade-off between AD and RDP of each profile. Tumor compartments AD (LHS) indicated by bar charts (its unit is Gy), and RDP of the tumors (RHS) shown by purple curve (its unit is percent) for patient two. According to our simulations, this patient may be clinically undertreated. Injection Number (N) = Number of injections, Time Interval (TI) = the time gap between each injection (hours), Total Amount (TA) = Total Amount of radiopharmaceutical (nmol), and A = labeled peptides (GBq). (b) Applying the Pareto Front method to identify optimal profiles which are on Pareto Front Curve (Red curve) after normalizing AD and RDP for each profile. Results for other patients are shown in supplemental Figs. S11-S14.

The effects and mechanisms of metronomic RPT

The results of this study demonstrate that increasing the frequency of administration (2, 4, and 6 injections) and prolonging the time intervals (12 h, 24 h, and 36 h) for the same amount of radioactivity administered clinically leads to significant increases in the AD of PSMA-positive compartments. To comprehend the underlying mechanism, the AD for tumors and OARs resulting from the labeled peptides in various sub-compartments was evaluated. As shown in Fig. 5a and b, the overall AD between five patients increased for tumors 1 and 2, as well as kidneys and salivary glands, by a range of 6–20%, 7–25%, 21–73%, and 17–56%, respectively, compared to a single-injection profile. These findings suggest that employing a metronomic approach may provide a promising alternative for achieving equivalent therapeutic outcomes for tumors compared to single-injection RPT, with reduced injected activity per patient. This is attributed to the increased ratio of peptides delivered to the tumor over labeled peptides injected using metronomic profiles. However, since the metronomic approach increases the AD to all PSMA-positive organs, it is important to monitor the AD to OARs as well. This approach not only yields economic benefits but also minimizes potential risks associated with unwanted irradiation for hospital staff and patients alike, by administering smaller, more frequent doses rather than a single large dose.

The overall AD in the tumors, resulting from labeled peptides present in muscle decreases in a range of 0.08–0.3 Gy (Figs. S16a, and S17a). Moreover, the overall AD in the tumor 1 and 2, kidney and salivary gland due to labeled peptides bound to proteins in blood serum (Figs. S16b, S17b, S18a, and S19a), as well as those in the vascular (Figs. S16c, S17c, S18b, and S19b) and interstitial spaces Figs. S16d, S17d, S18c, and S19c), decreases in a range of 9.5 × 10− 5 − 6 × 10− 4 Gy, 8.7 × 10− 5 − 3 × 10− 4 Gy, and 1 × 10− 3– 3 × 10− 3 Gy, respectively. On the other hand, AD due to the labeled peptides attached to the cell membrane receptors and those internalized into cells has shown a substantial increase. This increase ranges from 0.5 Gy to 1.6 Gy for peptides bound to receptors (Figs. S16e, S17e, S18d, and S19d) and from 1.6 Gy to 5.3 Gy for internalized peptides (Figs. S16f, S17f, S18e, and S19e), exceeding the reduction in AD observed in the other four subcomponents. Therefore, increasing of AD in PSMA-positive organs is attributable to more binding of labeled peptide to receptors which causes higher rate of internalization, and less presence in vascular and interstitial spaces. This results in reduction of AD level in PSMA-negative organs.

While the metronomic approach demonstrates promising outcomes in minimizing the activity injected to patients during treatment, it also presents certain limitations. Ideally, an effective treatment should increase the ratio of tumors-to-OARs AD. However, in the case of the metronomic approach, this ratio is reduced. This observation is indicated in Fig. 5c and d, where we see a decrease of 12–30%, 9–23%, 11–27%, and 8–20% in the tumor 1-to-kidney, tumor 1-to-salivary gland, tumor 2-to-kidney, and tumor 2-to-salivary gland AD ratios, respectively for all patients, compared to single dose injection.

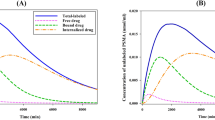

The findings demonstrate that, due to the administration of smaller amounts of radiopharmaceutical with more frequent intervals, a greater proportion of free receptors remain available for binding with labeled peptides at subsequent injection stages (Figs. S20a-S24a). The overall proportion of occupied receptors among all patients remains at 9.4% for two dose administration (2nd stage), remains at 5.2 to 5.7% for 4 dose administration (2nd to 4th stage), and remains at 3.6 to 4% (2nd to 6th stage) for 6 dose administration with 24 h time interval for tumor 1 (Figs. S25a). Moreover, the metronomic approach enhances the proportion of labeled peptides injected at each administration stage that successfully reach the receptors as shown in Figs. S20c, 6a, S22c-S24c. At the time receptors are occupied with the most labeled peptides (Tmax), 0.12% of injected labeled bind to receptors for single injection. This ratio is 0.15 − 0.13% for 2 dose administration (1st and 2nd stage), 0.17 to 0.15% for 4 dose administration (1st to 4th stage), and is 0.18 to 0.16% (1st to 6th stage) for 6 dose administration (Fig. 7a). Overall results among patients and other organs were demonstrated in Figs. S26a, S26c, and S26e.

Figures S20b-S24b, illustrate that increasing the time interval between injections enables a greater proportion of receptors to become available for binding in the next injection stage. For tumor 1 in time intervals of 12 h, 24 h, and 36 h, the overall proportion of occupied receptors among all patients due to disassociation of peptides or internalization are 25%, 9%, and 3%, respectively (Fig. S25b). Consequently, at Tmax, 0.12% of injected labeled peptides reaches to tumor 1 receptors (Figs. S20d, 6b, S22d-S24d), while this ratio is 0.15 and 0.11%, 0.15 and 0.13%, and 0.15 and 0.14% for 2 dose administration (at 1st and 2nd stage) (Fig. 7b) for 12 h, 24 h, and 36 h time interval, in order. Overall results among other organs for all patients are demonstrated in Figs. S26b, S26d, and S26f.

Consequently, both increasing frequency and time interval provides peptides a greater opportunity to bind to PSMA receptors while reducing their presence in vascular and interstitial spaces. Hence, a clear elevation in TIA of tumors is observed in metronomic RPT regimens.

Infusion duration

This section analyzes the effects of different infusion durations on the AD. The findings exhibit an increase in the AD of tumor compartments from 0.05 to 1% and a decrease in total tumor-to-OARs in a range of 0.16–4.3%, compared to bolus injection with a rise in the injection duration (1 to 4 h). These outcomes can be justified based on former explanations provided, regarding peptides having more time to bind to receptors. As the infusion duration of the radiopharmaceutical increases, the peptides gradually diffuse into the interstitial space; and, because a considerable quantity of peptide is not immediately delivered into that space, labeled peptides have more time to bind to the receptors.

Discussion

PBPK models are physiologically-informed mathematical tools that aid in comprehending and forecasting the pharmacokinetics of radiopharmaceuticals, as well as their distribution in individual patients24,25. Hence, these models demonstrate a high capability in personalizing RPT26,27,28. The scope of this study is to optimize therapeutic regimens for radiopharmaceutical treatment by either increasing the tumor-AD for a given amount of administered radiopharmaceutical or by achieving a prescribed tumor-AD while minimizing the amount of administered radiopharmaceutical. By employing PBPK modeling, we aim to investigate whether a metronomic approach could potentially outperform the current Standard of Care. PBPK models have the potential to significantly contribute to the field by providing a structured framework for addressing clinical challenges. Utilizing such models to inform clinical decision-making involves assessing treatment strategies before clinical implementation and exploring various clinical treatment scenarios. Ultimately, our work provides a framework for optimization of RPTs, and generates hypotheses that need to be prospectively validated with clinical trial studies.

Using this modeling approach (Fig. 1, and S1-S8), a computational procedure was designed (Fig. 2) to optimize the quantity of therapeutic agents administered to maximize the tumor AD whilst minimizing the injected radiopharmaceutical. This facilitates the creation of personalized metronomic regimen planning for patients with mCRPC undergoing RPT. A comparative investigation of metronomic treatment profiles for 2, 4 and 6-stage infusions with 12, 24, and 36 h time interval was carried out with a clinically administered plan to illustrate the importance of implementing personalized metronomic treatment planning through the execution of the formulated algorithm. This was done by determining the maximum achievable and safe amount of activity that could be injected, based on the limited amount-activity curve of OARs (Fig. 3, S9, and S10).

In the field of radiopharmaceutical therapy, researchers have employed PBPK models to optimize treatments and enhance the therapeutic index, often through the implementation of single-dose personalized therapy16,20,21,22. These studies have primarily focused on increasing the biologically effective dose (BED)17 and tumor control probability (TCP)16,17,18. However, these studies have predominantly aimed at increasing the amount of injected radiopharmaceutical, which can inadvertently impact healthy organs.

The primary objective of our study was to simultaneously increase RDP, which is a parameter we introduced to track the ratio of administered radiopharmaceuticals that affect to tumor lesions, and AD to tumors. This entails maximizing the delivered dose to tumors while minimizing the amount of injected radiopharmaceutical. Such an approach allows for a more comprehensive assessment of treatment efficacy and optimization, by finding a trade-off between AD and RDP. In this study, we personalized our model by fitting designed PBPK model to data acquired from gamma-camera images to estimate patient-specific parameters and determine the maximum amount of radiopharmaceutical to inject. Our goal was to evaluate the feasibility of increasing the delivered dose to the tumor while minimizing injected radiopharmaceutical.

The initial stage of the algorithmic framework was designed for identifying optimal profiles with the objective of maximizing the AD for each total amount of injected radiopharmaceutical in each administration profile. However, this necessitates a considerable rise in activity levels, which may result in undesirable side effects in some profiles. To alleviate this, RDP—a metric that evaluates the efficiency of radiopharmaceutical delivery by quantifying the proportion of the administered dose that successfully reaches the target tissue—was defined and explored with the aim of either minimizing the administered activity while still maximizing the AD to the tumor. Hence, the second stage of the treatment strategy employed the RDP as a delivery efficacy factor and the Pareto front methodology to determine the optimal balance between the RDP and AD (Fig. 4, S11-S14).

The Pareto front method select a set of profiles where no profile can be improved in parameters (AD or RDP) without degrading another parameter. In other words, it represents the optimal trade-offs between conflicting parameters in a problem and offers multiple desirable solutions. The primary objective of this study is to establish a critical AD for OARs and assess the impact of the metronomic approach on tumor AD while simultaneously monitoring injected activity and the delivered ratio of injected radiopharmaceutical to the tumor target. It is evident that the RDP of OARs responds similarly to that of tumors. To assess the impact of the metronomic approach on OARs, we have presented the tumor to OAR absorbed dose ratio. This ratio implies that the RDP of OARs also increases when employing the metronomic approach.

It should be noted that all tumor compartments, including tumor 1, 2, and the rest, respond to treatment in the same manner. For instance, our simulations indicate that if the number of injections increases, the AD for all tumors would increase as well. However, due to the scope of our study, which aims to compare changes in the delivered dose to tumors using both single-dose and metronomic approaches, and considering that all patients in our study have mCRPC, assigning a separate compartment to each tumor lesion would significantly complicate the calculation process and does not affect our comparison between different injection profiles. To streamline our model, we allocated a specific compartment to represent all other tumor lesions. Subsequently, we computed the AD for each compartment, referring to the sum of all tumor ADs as the total tumor AD.

The second important finding reveals that the utilization of a metronomic approach results in the delivery of a higher proportion of injected radiopharmaceutical to both the tumor lesions and dose-limiting organs. The findings exhibit that despite a constant total dose of the administered radioactivity, an increase in the frequency of radiopharmaceutical infusion and an elongation of the inter-infusion intervals leads to an increase in delivery payload (Fig. 5). However, it led to a decrease in tumors-to-OARs AD ratio (Fig. 5). The higher delivery observed in the metronomic approach can be attributed to two factors. Firstly, by administering a smaller amount of labeled peptides at each injection stage, which occurs as the number of infusions increases, more free receptors become available for ligands to bind. Secondly, as the time interval between injections increases, the number of free receptors increases due to the reduced number of free peptides over time, providing more receptors available for ligands to bind (Figs. 6 and 7, S15-26). Model simulations suggest that an increase in the duration of administration may leads to a corresponding increase in AD but it reduces total tumor-to-OARs AD ratio as well.

The ratio of labeled peptide at tmax bound to receptors over total amount of labeled peptide injected at each injection stage for (a) different number of injections (24 h time interval), and (b) different time intervals (2 times injection). Note that only how much labeled peptide bound to receptors at that same stage considered.

Reducing the amount of radiopharmaceutical administered to patients using metronomic approach has both challenges and potential benefits. On the one hand, multiple infusions may necessitate more frequent hospital visits, extended stays, and increased demand on hospital staff and resources. On the other hand, there are significant environmental, safety, and economic benefits. Lower doses of radiopharmaceuticals can reduce the costs associated with the production, handling, and disposal of radioactive materials. For healthcare providers and staff, reduced unwanted irradiation, enhances safety. Furthermore, decreased radioactive usage in hospitals and clinics can lower waste management costs and reduce the need for extensive safety protocols and infrastructure to manage higher levels of radioactivity. These potential benefits underscore the importance of optimizing radiopharmaceutical doses for improved patient care and broader healthcare system efficiencies. This is because by enhancing delivery efficiency (the proportion of the administered radiopharmaceutical that successfully reaches the tumor) using metronomic technique, one can decrease the activity given to patients while yielding the same level tumor AD compared to a single-dose administration of a higher injected activity. Moreover, a personalized treatment approach (e.g. via theranostic digital twins) can help tackle the existing systematic undertreatment of RPT patients15,29. Theranostic digital twins are virtual patient-specific models that integrate patient data, including physiological, pharmacokinetic, and imaging information, to simulate and optimize treatment outcomes. By leveraging these virtual patients, clinicians can predict individual responses to different radiopharmaceutical regimens upfront, enabling more precise and effective treatment planning.

Based on our findings, we recommend adopting a metronomic approach to radiopharmaceutical administration, which involves smaller, more frequent infusions over extended intervals. This strategy optimizes receptor binding and increases the proportion of the administered radiopharmaceutical that successfully reaches the tumor, leading to higher AD to tumors while reducing the total administered radiopharmaceutical. While this approach offers enhanced safety, cost-efficiency, and reduced environmental impact, it requires careful clinical validation to balance logistical challenges, such as increased hospital visits, with therapeutic benefits. Additionally, improvements in the radiolabeling process, such as achieving higher specific activity, would further enhance RPT outcomes by allowing more labeled peptides to bind to tumor receptors.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that increasing the frequency of radiopharmaceutical administration and prolonging the inter-infusion intervals, as well as increasing infusion duration, can lead to a significantly increase in delivery payload to tumors due to a higher number of labeled peptides binding to tumor PSMA receptors. However, these techniques can reduce tumor-to-OARs AD ratio. Furthermore, a comparative analysis of metronomic treatment approach with conventional treatment plans showed that implementation of personalized metronomic treatment using the formulated algorithm results in a higher proportion of injected radiopharmaceutical being delivered to the tumor lesions. These findings provide valuable insights into the importance of PBPK modeling and personalized treatment planning in the optimization of therapeutic regimens and the advancement of RPT. Moreover, using PBPK modeling is seen as a useful way to explore the presence of radiopharmaceuticals in tissues in more detail, and fine-tuning of therapeutic regimens for individual patients, by creating a virtual patient. Overall, the metronomic approach has the potential to reduce injected radioactivities, leading to potentially fewer side effects and increased cost-effectiveness while still achieving acceptable results compared to traditionally implemented single-dose profiles. To advance the approach outlined in this study, potential next steps involve conducting further empirical studies to validate the findings, optimize the treatment regimen, and guide future advancements in RPT.

Data availability

All data used for this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Kletting, P. et al. Optimal preloading in radioimmunotherapy with anti-CD45 antibody. Med. Phys. 38, 2572–2578 (2011).

Barca, C. et al. Expanding theranostic radiopharmaceuticals for tumor diagnosis and therapy. Pharmaceuticals 15, 13 (2021).

Miller, C. et al. Implications of physics, chemistry and biology for dosimetry calculations using theranostic pairs. Theranostics 12, 232 (2022).

Fendler, W. P., Rahbar, K., Herrmann, K., Kratochwil, C. & Eiber, M. 177Lu-PSMA radioligand therapy for prostate cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 58, 1196–1200 (2017).

Golzaryan, A., Soltani, M., Moradi Kashkooli, F., Uribe, C. & Rahmim, A. An in silico study quantifying the effects of reducing salivary gland blood flow on tumor to organ-at-risk absorbed dose ratios. J. Nucl. Med. 64, P619–P619 (2023).

Moradi Kashkooli, F. & Soltani, M. Evaluation of solid tumor response to sequential treatment cycles via a new computational hybrid approach. Sci. Rep. 11, 1–15 (2021).

Wysocki, P. J., Lubas, M. T. & Wysocka, M. L. Metronomic chemotherapy in prostate cancer. J. Clin. Med. 11, 2853 (2022).

Cazzaniga, M. E. et al. Metronomic chemotherapy. Cancers 13, 2236 (2021).

He, L. et al. Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: academic insights and perspectives through bibliometric analysis. Medicine 99 (2020).

Silver, D. A., Pellicer, I., Fair, W. R., Heston, W. & Cordon-Cardo, C. Prostate-specific membrane antigen expression in normal and malignant human tissues. Clin. Cancer Res. Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res. 3, 81–85 (1997).

El Fakiri, M., Geis, N. M., Ayada, N., Eder, M. & Eder A.-C. PSMA-targeting radiopharmaceuticals for prostate cancer therapy: recent developments and future perspectives. Cancers 13, 3967 (2021).

Glatting, G., Bardiès, M. & Lassmann, M. Treatment planning in molecular radiotherapy. Z. Med. Phys. 23, 262–269 (2013).

Soltani, M. & Chen, P. Numerical modeling of fluid flow in solid tumors. PloS One 6, e20344 (2011).

Glatting, G., Eiber, M. & Kletting, P. The effect of total tumor volume on the biologically effective dose to tumor and kidneys for 177 Lu-labeled.

Rahmim, A. et al. Theranostic digital twins for personalized radiopharmaceutical therapies: reimagining theranostics via computational nuclear oncology. Front. Oncol. 12, 1062592 (2022).

Begum, N. J. et al. The effect of total tumor volume on the biologically effective dose to tumor and kidneys for 177Lu-labeled PSMA peptides. J. Nucl. Med. 59, 929–933 (2018).

Kletting, P. et al. Investigating the effect of ligand amount and injected therapeutic activity: a simulation study for 177Lu-labeled PSMA-targeting peptides. PLoS One. 11, e0162303 (2016).

Jiménez-Franco, L. D. et al. Effect of tumor perfusion and receptor density on tumor control probability in 177Lu-DOTATATE therapy: an in silico analysis for standard and optimized treatment. J. Nucl. Med. 62, 92–98 (2021).

Jiménez-Franco, L. D., Kletting, P., Beer, A. J. & Glatting, G. Treatment planning algorithm for peptide receptor radionuclide therapy considering multiple tumor lesions and organs at risk. Med. Phys. 45, 3516–3523 (2018).

Begum, N. J. et al. The effect of ligand amount, affinity and internalization on PSMA-targeted imaging and therapy: a simulation study using a PBPK model. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–8 (2019).

Siebinga, H. et al. A physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model to describe organ distribution of 68 Ga-DOTATATE in patients without neuroendocrine tumors. EJNMMI Res. 11, 1–12 (2021).

Hardiansyah, D. et al. Important pharmacokinetic parameters for individualization of 177Lu-PSMA therapy: a global sensitivity analysis for a physiologically‐based pharmacokinetic model. Med. Phys. 48, 556–568 (2021).

Willowson, K. P. et al. A comparison of 2D and 3D kidney absorbed dose measures in patients receiving 177Lu-DOTATATE. Asia Ocean. J. Nucl. Med. Biol. 6, 113 (2018).

Kletting, P. et al. Optimized peptide amount and activity for 90Y-labeled DOTATATE therapy. J. Nucl. Med. 57, 503–508 (2016).

Gospavic, R., Knoll, P., Mirzaei, S. & Popov, V. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model for biodistribution of radiolabeled peptides in patients with neuroendocrine tumours. Asia Ocean. J. Nucl. Med. Biol. 4, 90 (2016).

Hardiansyah, D. et al. The role of patient-based treatment planning in peptide receptor radionuclide therapy. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 43, 871–880 (2016).

Hardiansyah, D., Attarwala, A. A., Kletting, P., Mottaghy, F. M. & Glatting, G. Prediction of time-integrated activity coefficients in PRRT using simulated dynamic PET and a pharmacokinetic model. Phys. Med. 42, 298–304 (2017).

Hardiansyah, D., Guo, W., Kletting, P., Mottaghy, F. M. & Glatting, G. Time-integrated activity coefficient estimation for radionuclide therapy using PET and a pharmacokinetic model: a simulation study on the effect of sampling schedule and noise. Med. Phys. 43, 5145–5154 (2016).

Brosch-Lenz, J., Uribe, C., Rahmim, A. & Saboury, B. Theranostic digital twins: an indispensable prerequisite for personalized cancer care. J. Nucl. Med. (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, mathematical modeling and simulations, and analysis were performed by AG. The first draft of the manuscript was written by AG and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. This work was under the supervision of AR, BS, FMK, and MS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Golzaryan, A., Soltani, M., Moradi Kashkooli, F. et al. Personalized metronomic radiopharmaceutical therapy through injection profile optimization via physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling. Sci Rep 15, 4052 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86159-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86159-9