Abstract

This study delves into the impact of precise health management coupled with physical rehabilitation on bone biomarkers in elderly patients with osteoporosis. Two hundred and forty individuals diagnosed with senile osteoporosis were randomly assigned to either the observation group (precision health management group, n = 120) or the control group (routine health management group, n = 120). Patients in the control group received standard health care, while those in the observation group received personalized health care along with physical therapy. Pain levels (assessed by VAS score), understanding of osteoporosis, confidence in managing osteoporosis, bone density, and biochemical markers of bone metabolism were compared between the groups at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months before and after the intervention. Following the intervention, the observation group exhibited significantly reduced VAS values and PTH levels at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months compared to the control group (P < 0.05). Additionally, scores on the Osteoporosis Knowledge Scale, Osteoporosis Self-Efficacy Scale, bone mineral density (BMD), ALP levels, and calcium levels were significantly higher in the observation group compared to the control group (P < 0.05). The integration of precise health monitoring with tailored physical therapy shows substantial efficacy in reducing pain among elderly individuals suffering from osteoporosis. Moreover, it empowers them in managing their health effectively, while also contributing to increased BMD and improved bone biomarker levels. This holistic approach merits recommendation for clinical implementation and warrants further investigation through rigorous study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporosis poses a critical health concern for the elderly population. As individuals age, there is a gradual decline in bone mass, leading to conditions like osteopenia and osteoporosis. This decrease in bone density significantly heightens the risk of bone fractures, subsequently increasing morbidity and mortality rates1. Rehabilitation approaches for osteoporosis have become increasingly diversified, enabling clinicians to design personalized treatment plans for each patient.

Research indicates that physical activity can effectively enhance cortical bone density and strength in older individuals, particularly at sites of bone loading. However, it’s important to note that the improvements in bone strength resulting from exercise in the elderly may stem from a reduction in cortical bone and/or an increase in tissue density rather than an increase in bone size (periosteal hyperplasia)2,3. In recent clinical practice, the integration of precise health management with physical rehabilitation has emerged as a crucial aspect of osteoporosis treatment. Despite this recognition, there remains a dearth of research evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of combining precise health management with physical rehabilitation in clinical settings4. Therefore, over the course of a one-year research period, investigating how this combined approach can positively influence bone biomarker levels in elderly patients with osteoporosis is deemed clinically significant. These findings have the potential to equip clinicians with invaluable insights for devising more tailored and effective treatment strategies for osteoporosis patients5,6.

This study involves the random assignment of 240 patients with age-related osteoporosis to either the intervention or control group. The primary objective is to explore how precise health management and physical rehabilitation impact bone biomarkers in this patient demographic. Ultimately, the aim of this research is to provide theoretical guidance for the postoperative care of individuals with age-related osteoporosis.

Participants and methods

Participants

This study started in January 2021 and ended in December 2022. A total of 240 patients diagnosed with senile osteoporosis were enrolled from both outpatient and inpatient departments of our hospital between January 2021 and December 2021. The cohort comprised 128 males and 112 females, with an average age of (66.82 ± 5.42) years. Inclusion criteria: (1) Clinical diagnosis meeting the relevant diagnostic criteria outlined in the 2016 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Senile Osteoporosis by the American Medical Association. (2) Age between 60 and 75 years. (3) Sufficient cognitive ability to complete the scale content and cooperate with intervention and regular reviews. (4) Normal cognitive function screening results, ensuring cooperation with intervention and regular assessments. (5) Voluntary participation in the study. (6) All study participants and their families provided signed informed consent forms. Exclusion Criteria: (1) Allergy to any drugs used in this study. (2) Presence of significant organ damage, such as heart, liver, or kidney complications. (3) Secondary osteoporosis due to factors such as medication use or disuse. (4) Receipt of regular anti-osteoporosis treatment within the past 3 months. (5) Occurrence of other diseases during the intervention period that could potentially impact the intervention.

The research team randomly selected 240 patients and divided them into two groups: the observation group (receiving precise health management, n = 120) and the control group (receiving routine health management, n = 120). Both groups had health management files established using health management software and were prescribed oral anti-osteoporosis drugs, specifically calcitriol and vitamin D calcium chewable tablets. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Hospital of Hebei Medical University (No.20200606).

Routine health management

Routine health management included standard disease education and management practices. This encompassed educating patients about osteoporosis causes, precautions for fracture prevention, dietary and exercise guidelines, as well as information on medications affecting osteoporosis.

Accurate health management combined with physical rehabilitation

Accurate health management

Patients underwent accurate management for a duration of 2 years, with intervention measures tailored to their individual risk factors. Specific interventions included strengthening patients’ awareness of osteoporosis management through various channels such as the WeChat platform, regular lectures, home education sessions, and remote real-time monitoring. This monitoring involved tracking patients’ diet, exercise, physiological indicators, and medication adherence through health management software and continuously updated wearable devices. Guidance and adjustments were made according to individual patient conditions to improve lifestyle factors and provide psychological support7. (1) Build a digital platform: the platform includes patient case data, fracture risk assessment system, osteoporosis knowledge, quality of life and other scale assessment systems. (2) Sustainable osteoporosis health management based on the digital platform: (1) Continuous systematic health education: the combination of regular on-site education guidance and information push means is adopted to provide targeted long-term and continuous comprehensive guidance on osteoporosis health knowledge, diet guidance, exercise guidance, medication guidance and psychological guidance; Especially for patients with a higher risk of fracture, special emphasis is put on fall prevention programs: such as room layout, balance training, scientific support and so on. ② Develop a standardized treatment plan: According to the results of the stratified assessment of fracture risk and the results of laboratory examination, develop a scientific anti-osteoporosis treatment plan, and constantly adjust and optimize the treatment plan according to the follow-up data in the database. (3) Continuous information follow-up and guidance supervision: establish a follow-up mechanism based on the digital platform, push medication reminders and follow-up reminders on time, and regularly push diet, exercise list, etc.

Specific physical rehabilitation program

Patients were provided with the option to choose from aerobic exercises such as walking and Taijiquan based on personal preferences. Each exercise session lasted approximately 15 min, with patients maintaining a heart rate close to the appropriate target rate (calculated as 170 minus age) during exercise. Exercise intensity was controlled to induce mild fatigue, gradually increasing as the session progresses. After a 5-minute rest period, strength training commenced. Exercises including leg elevation, half squats, plank holds, and seated rows were selected based on individual capabilities. Each exercise comprised 8 repetitions per set, with a total of 3 sets and a 1-minute rest between each set. Balance training followed after a 10-minute rest period. This included one-legged balance exercises, with patients maintaining balance for over 1 min per leg. Additionally, ankle joint exercises involved rotating each foot clockwise and counterclockwise 5 times, repeated for a total of 5 sets. Foot exercises were performed using a toe towel for 1 min. Finally, patients engaged in another 10 min of walking. Family members accompanied patients throughout the exercise session, with training duration, intensity, and frequency adjusted accordingly based on the partner’s endurance level.

Observation indicators

Pain levels

The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was utilized to evaluate pain levels in both groups before treatment and at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-treatment. Scores ranged from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating no pain. A score below 3 signified effective pain relief, while scores between 4 and 6 indicated manageable pain. Scores of 7 to 10 indicated inadequate pain relief, with increasing intensity impacting appetite and sleep8.

-

(1)

Nutritional balance is the key to maintaining bone health9. Patients should consume foods high in calcium, low in salt, and moderate in protein, while ensuring adequate intake of vitamin D, avoiding caffeine and alcohol interference with calcium absorption, and ensuring comprehensive nutritional support for the bones. Osteoporosis patients should eat more calcium rich foods, such as milk, yogurt, cheese and other dairy products, and bean products such as tofu, soybean milk. In addition, deep-sea fish, leafy vegetables, and nuts are also good sources of calcium. A balanced diet ensures diverse calcium intake. Vitamin D is crucial for bone health as it promotes the absorption of calcium and phosphorus, maintains bone strength, and reduces the risk of fractures. Daily intake can be achieved through sun exposure and consumption of foods rich in vitamin D, such as seafood and egg yolks. If necessary, consider supplementing with vitamin D supplements in moderation. High salt, high sugar, high-fat, and excessive caffeine intake should be avoided in diet, as these unhealthy habits can lead to calcium loss and affect bone health. At the same time, quit smoking and limit alcohol consumption, avoid overeating and excessive consumption of raw, cold, and stimulating foods to protect bone health.

-

(2)

Suitable exercise types for osteoporosis patients: The appropriate exercise types for osteoporosis patients mainly include weight bearing aerobic exercise (such as walking, dancing), flexibility training (such as stretching), and strength training (such as lifting dumbbells). These exercises can reduce bone mineral loss, enhance bone strength, and improve body balance. In sports and rehabilitation exercises, it is necessary to control the intensity of exercise reasonably according to individual physical fitness and condition. In the initial stage, mild exercise is mainly used, and gradually the intensity can be increased appropriately after adaptation. If you feel uncomfortable, you should immediately adjust or stop exercising to ensure safety and effectiveness. Rehabilitation exercises include stepping, tiptoeing, hip abduction, knee extension, shoulder rotation, etc., which can be combined with dumbbells, elastic bands, etc. for strength training. Pay attention to gradual progress and avoid high-intensity, high impact sports such as jumping. Exercise for 30–60 min each time, 3–5 times a week. During exercise and rehabilitation, patients with osteoporosis should pay attention to safety protection. Choose a flat and non slip sports field, and wear appropriate protective equipment such as knee pads and wrist guards. Avoid high-intensity and high-risk sports, ensure standardized movements to prevent falls and injuries, and ensure sports safety.

-

(3)

Improving lifestyle habits: quitting smoking and limiting alcohol consumption is crucial for maintaining bone health. Quitting smoking can reduce the damage of nicotine to bones and promote bone formation; Moderate alcohol restriction can prevent increased bone resorption caused by alcohol, maintain bone metabolism balance, and thus reduce the risk of osteoporosis. Adequate sleep is crucial for bone recovery. Good sleep can regulate hormones, promote growth hormone secretion, and aid in bone repair and calcium absorption. It is recommended to maintain 7–9 h of high-quality sleep every night to maintain bone health and slow down the process of osteoporosis. Maintaining the same posture for a long time, whether it’s sitting or standing, can put unnecessary pressure on the bones and accelerate the development of osteoporosis. Therefore, it is recommended to change positions and engage in simple stretching activities at regular intervals to alleviate bone burden and maintain bone health.

Osteoporosis knowledge scale scores

The Osteoporosis Knowledge Scale questionnaire was employed to assess osteoporosis understanding in both patient groups before treatment and at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-intervention. This questionnaire encompassed three domains: osteoporosis risk factors, exercise knowledge, and calcium knowledge, comprising a total of 26 items. Points ranging from 0 to 26 were allocated based on the accuracy of responses. Higher scores denote a greater level of osteoporosis knowledge, with a Cronbach coefficient ranging from 0.84 to 0.87, alongside content validity exceeding 0.8, and demonstrating high reliability and validity.

Osteoporosis self-efficacy scale scores

Self-efficacy levels were assessed using the Osteoporosis Self-Efficacy Scale before intervention and at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-intervention. This scale comprised two dimensions: exercise efficacy and calcium efficacy, totaling 12 items. Scores range from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating a complete lack of confidence and 10 representing maximum confidence. The total score ranges from 0 to 120. Higher scores indicate higher levels of self-efficacy, with a Cronbach coefficient ranging from 0.88 to 0.95, demonstrating high reliability and validity10.

Bone density

Bone mineral density (BMD) changes were evaluated using GE Lunar Prodigy/DPX-X BMD (General Electric Company, United States) in the imaging department of our hospital before intervention and at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-intervention. Measurements were taken at the lumbar 1–4 segments (L1-L4) and the left femoral neck. BMD was calculated accordingly11.

Laboratory indicator levels

Biochemical indicators of bone metabolism, including alkaline phosphatase (ALP), parathyroid hormone (PTH), and blood calcium (Ca), were assessed in both patient groups before intervention and at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-intervention.

Patient satisfaction with the intervention

Patient satisfaction with the intervention was evaluated using a self-developed “satisfaction survey questionnaire” administered within the hospital. The questionnaire comprised 25 items, each scored on a 4-point scale. Levels of satisfaction were categorized as very satisfied, satisfied, or dissatisfied, with a maximum score of 100 points. Higher scores indicate increased patient satisfaction with the intervention.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis in this study was conducted using SPSS 20.0 statistical analysis software (IBM, USA). Measurement data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (\({\bar{\text{x}}}\) ± s), and inter-group comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Count data were expressed as percentages (%), and comparisons between groups were conducted using chi-square (χ2) analysis. A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

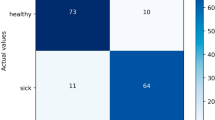

Comparison of pain scores between the two groups

The VAS scores in both groups exhibited significant decreases at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-intervention compared to pre-intervention, demonstrating statistical significance (P < 0.05). Moreover, the VAS scores of patients who underwent the intervention were significantly lower than those in the control group at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-intervention (P < 0.05) (Table 1; Fig. 1).

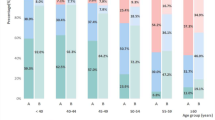

Comparison of osteoporosis knowledge scale scores between the two groups

The osteoporosis knowledge scale scores in both groups exhibited significant increases at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-intervention compared to pre-intervention, demonstrating statistical significance (P < 0.05). Additionally, the observation group achieved notably higher scores on the osteoporosis knowledge scale than the control group at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-intervention (P < 0.05) (Table 2; Fig. 2).

Comparison of osteoporosis self-efficacy scale scores between the two groups

The osteoporosis self-efficacy scale scores in both groups demonstrated a significant increase at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-intervention compared to pre-intervention (P < 0.05). Moreover, the observation group exhibited notably higher scores on the osteoporosis self-efficacy scale compared to the control group at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-intervention (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

Comparison of BMD between the two groups

The BMD of both groups exhibited significant increases at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-intervention compared to pre-intervention (P < 0.05). Notably, patients in the observation group demonstrated significantly greater BMD than those in the control group at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-intervention (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

Comparison of laboratory indexes between the two groups

ALP and Ca levels in both groups demonstrated significant increases at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-intervention compared to pre-intervention levels, while PTH levels exhibited significant decreases with statistical significance (P < 0.05). Additionally, ALP and Ca levels were notably elevated in the observation group compared to the control group at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-intervention, whereas PTH levels were significantly reduced in the observation group with statistical significance (P < 0.05) (Table 5).

Discussion

Osteoporosis is deemed clinically significant primarily when it culminates in a fracture, as it often remains asymptomatic until such an event occurs, leading to pain and potential disability2. With advancing age, there’s a natural decline in bone density, heightening the susceptibility to fractures, notably in the hip, spine, and forearm3. These fractures exert profound impacts on mortality rates, overall health, and impose substantial financial burdens. Global estimates indicate that as individuals age, approximately one-third of women and one-fifth of men over 50 will experience osteoporotic fractures. The elderly, in particular, face significant challenges due to physical frailty and functional decline4,12. Hence, it becomes imperative to identify strategies aimed at expediting the rapid rehabilitation of elderly patients with osteoporosis.

The increase in bone density involves three key factors: the initial closure of bone remodeling space, subsequent mineralization, and bone formation13. According to research, physical therapy plays a crucial role in preserving bone density, enhancing muscle strength, and improving stability14. Therefore, aerobic exercise and/or resistance training, even without accompanying drug therapy, can effectively mitigate bone density loss in osteoporosis, addressing the functional and health needs of the elderly. Exercise therapy not only stimulates the secretion of sex hormones and regulates the body’s blood state but also enhances the synthesis, metabolism, and reconstruction of bone and muscle tissues, thereby improving bone density and maintaining bone balance. Sun exposure facilitates the body’s absorption of calcium ions, promotes bone growth, and enhances immune function. When combined with proper nutrition and exercise, sun exposure ensures the absorption of necessary nutrients and promotes calcium ion absorption, thereby enhancing BMD and expediting the rehabilitation of osteoporotic hip fractures while improving patients’ daily living abilities. The study findings revealed a significant increase in BMD among patients in both the observation and control groups at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-intervention. Furthermore, patients in the observation group exhibited notably higher BMD levels than those in the control group (P < 0.05). These results underscore the effectiveness of combining precise health management and physical rehabilitation in enhancing BMD and mitigating the risk of osteoporosis, consistent with the findings of Chen et al.15.

Precise health management encompasses personalized treatment, comprehensive care, promotion of self-care awareness, appropriate nutrition, regular exercise, preventive measures, and recognition of the spiritual essence of each individual. By addressing these aspects, it aims to enhance patients’ physical and mental well-being, assist them in adopting a healthy lifestyle, boost their self-confidence, and alleviate pain16,17. Certain lifestyle factors such as alcohol consumption and smoking are detrimental to osteoporosis patients, making it essential to abstain from these habits for optimal bone health. However, adherence to maintaining good lifestyle habits can be challenging, especially in the long term. Enrolling patients in digital-based continuous osteoporosis health management has been shown to significantly increase the adoption of good lifestyle habits in the short term. Moreover, over time, the number of good lifestyle habits remains consistently high during the follow-up period, without significant decreases. Research findings indicated that following precise health management, the observation group achieved significantly higher scores on the osteoporosis knowledge scale and self-efficacy compared to the control group (P < 0.05). Compared to traditional health management, incorporating precise health management along with physical rehabilitation can motivate patients to enhance their self-care skills, alleviate clinical symptoms, and improve their overall quality of life18. This is attributed to the promotion of a positive and optimistic attitude by precise health management combined with physical rehabilitation, which also helps alleviate negative emotions such as tension and anxiety19. Furthermore, the study findings revealed a significant increase in ALP and Ca levels in both groups at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months post-intervention, accompanied by a notable decrease in PTH levels (P < 0.05). Additionally, the observation group exhibited significantly higher ALP and Ca levels compared to the control group, while PTH levels were notably lower (P < 0.05). Similarly, research by Harding et al. also found that bone metabolic marker levels undergo significant changes under precise health management, and physical rehabilitation can promote bone formation and increase bone density11,20,21.

This study innovatively combines precision health management and physical rehabilitation methods to investigate the impact of elderly patients with osteoporosis on bone biomarkers22,23. The research not only enriches the theory of osteoporosis rehabilitation, but also provides scientific and effective intervention strategies for patients, making important practical contributions. Although this study has achieved certain results, there are still limitations. The relatively small sample size may affect the generalizability of the results; The research period is relatively short, making it difficult to comprehensively observe long-term effects; In addition, changes in bone biomarkers are influenced by multiple factors, and this study was unable to completely exclude all interfering factors. Future research can further explore the long-term effects of precision health management combined with physical rehabilitation on bone biomarkers in elderly patients with osteoporosis, and optimize rehabilitation plans. At the same time, the adaptability of patients with different constitutions to this treatment plan can be studied, as well as the comprehensive effect of combining other treatment methods, to provide better treatment strategies for elderly osteoporosis patients.

In conclusion, precise healthcare management combined with physical therapy demonstrates significant benefits for elderly individuals with osteoporosis. It effectively reduces pain, enhances self-management capabilities, increases BMD, and improves bone biomarker levels. Given these positive outcomes, this approach holds substantial promise for clinical application.

Data availability

The data and materials used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ALP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of variance

- BMD:

-

Bone mineral density

- Ca:

-

Blood calcium

- L1-L4:

-

Lumbar 1–4 segments

- PTH:

-

Parathyroid hormone

- VAS:

-

Visual analog scale

References

Lewiecki, E. M. et al. Efficacy and safety of transdermal abaloparatide in postmenopausal Women with osteoporosis: A randomized study. J. Bone Mineral. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Mineral. Res. 38(10), 1404–1414 (2023).

Stanghelle, B. et al. Effects of a resistance and balance exercise programme on physical fitness, health-related quality of life and fear of falling in older women with osteoporosis and vertebral fracture: A randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos. Int. J. Establ. Result Cooper. Between Eur. Found. Osteoporos. Natl. Osteoporos. Found. USA. 31(6), 1069–1078 (2020).

Zhang, F. et al. Effect of a home-based resistance exercise program in elderly participants with osteoporosis: A randomized controlled trial. Osteoporos. Int. J. Establ. Result Cooper. Between Eur. Found. Osteoporos. Natl. Osteoporos. Found. USA. 33(9), 1937–1947 (2022).

Stanghelle, B. et al. Physical fitness in older women with osteoporosis and vertebral fracture after a resistance and balance exercise programme: 3-month post-intervention follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 21(1), 471 (2020).

Perissiou, M. & Borkoles, E. The Effect of an 8 week prescribed Exercise and Low-Carbohydrate Diet on Cardiorespiratory Fitness, body composition and cardiometabolic risk factors in obese individuals: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Nutrients 12(2), 482 (2020).

Kistler-Fischbacher, M., Yong, J. S. & Weeks, B. K. A comparison of bone-targeted Exercise with and without antiresorptive bone medication to reduce indices of fracture risk in Postmenopausal Women with Low Bone Mass: The MEDEX-OP Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Bone Mineral. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Mineral. Res. 36(9), 1680–1693 (2021).

Bragonzoni, L. & Barone, G. Influence of coaching on effectiveness, participation, and safety of an exercise program for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: A randomized trial. Clin. Interv. Aging. 18, 143–155 (2023).

Kemmler, W. & Kohl, M. Effects of High Intensity Dynamic Resistance Exercise and Whey protein supplements on Osteosarcopenia in older men with Low Bone and Muscle mass. Final results of the Randomized controlled FrOST Study. Nutrients 12(8), 2341 (2020).

Blanca Alabadi, M., Civera, B., Moreno-Errasquin, A. J. & Cruz-Jentoft. Nutrition-based support for osteoporosis in Postmenopausal women: A review of recent evidence. Int J. Womens Health. 16, 693–705 (2024).

Talevski, J. et al. Effects of an 18-month community-based, multifaceted, exercise program on patient-reported outcomes in older adults at risk of fracture: Secondary analysis of a randomised controlled trial. Osteoporos. Int. J. Establ. Result Cooper. Between Eur. Foundation Osteoporos. Natl. Osteoporos. Found. USA. 34(5), 891–900 (2023).

Kong, J., Tian, C. & Zhu, L. Effect of different types of Tai Chi exercise programs on the rate of change in bone mineral density in middle-aged adults at risk of osteoporosis: A randomized controlled trial. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 18(1), 949 (2023).

Kemmler, W., Kohl, M., Fröhlich, M. & Jakob, F. Effects of High-Intensity Resistance Training on Osteopenia and Sarcopenia parameters in older men with Osteosarcopenia-One-Year results of the Randomized Controlled Franconian Osteopenia and Sarcopenia Trial (FrOST). J. Bone Mineral. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Mineral. Res. 35(9), 1634–1644 (2020).

De Souza, M. J. & Strock, N. C. A. Prunes preserve hip bone mineral density in a 12-month randomized controlled trial in postmenopausal women: The Prune Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 116(4), 897–910 (2022).

Kraljević Pavelić, S., Micek, V., Bobinac, D., Bazdulj, E. & Gianoncelli, A. Treatment of osteoporosis with a modified zeolite shows beneficial effects in an osteoporotic rat model and a human clinical trial. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood NJ). 246(5), 529–537 (2021).

Chen, G. et al. Biomarkers of postmenopausal osteoporosis and interventive mechanism of catgut embedding in acupoints. Medicine 99(37), e22178 (2020).

Okuda, R. & Osaki, M. Effect of coordinator-based osteoporosis intervention on quality of life in patients with fragility fractures: A prospective randomized trial. Osteoporos. Int. J. Establ. Result Cooper. Between Eur. Foundation Osteoporos. Natl. Osteoporos. Found. USA. 33(7), 1445–1455 (2022).

Barker, K. L. & Newman, M. Physiotherapy rehabilitation for osteoporotic vertebral fracture-a randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation (PROVE trial). Osteoporos. Int. J. Establ. Result Cooper. Between Eur. Found. Osteoporos. Natl. Osteoporos. Found. USA. 31(2), 277–289 (2020).

Baek, K. H. et al. Romosozumab in postmenopausal Korean women with osteoporosis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled efficacy and safety study. Endocrinol. Metabolism (Seoul Korea). 36(1), 60–69 (2021).

Shiraki, M. & Kuroda, T. Acute phase reactions after intravenous infusion of Zoledronic Acid in Japanese patients with Osteoporosis: Sub-analyses of the Phase III ZONE Study. Calcif. Tissue Int. 109(6), 666–674 (2021).

Harding, A. T. et al. A comparison of bone-targeted Exercise strategies to reduce fracture risk in Middle-aged and older men with Osteopenia and osteoporosis: LIFTMOR-M semi-randomized controlled trial. J. Bone Mineral. Res. Off. J. Am. Soc. Bone Mineral. Res. 35(8), 1404–1414 (2020).

Du, Z. et al. Effects of precision health management combined with dual-energy bone densitometer treatment on bone biomarkers in senile osteoporosis patients. Exp. Gerontol. 198, 112642 (2024).

de Nigris, F., Ruosi, C., Colella, G. & Napoli, C. Epigenetic therapies of osteoporosis. Bone 142, 115680 (2021).

Hakami, I. A. An outline on the advancements in Surgical Management of osteoporosis-Associated fractures. Cureus 16(6), e63226 (2024).

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This study was funded by 2021 Hebei Province medical science research project (No. 20211302).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZD and YP contributed to the conception and design of the study; LC and XY performed the experiments; YL, JZ and LZ collected and analyzed data; LC and XY wrote the manuscript; ZD and YP revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The First Hospital of Hebei Medical University (No.20200606). Prior to participation in the study, patients and their guardians provided informed consent, demonstrating their willingness to be included in the research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, L., Yan, X., Liu, Y. et al. Effect of precise health management combined with physical rehabilitation on bone biomarkers in senile osteoporosis patients. Sci Rep 15, 2458 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86188-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86188-4