Abstract

Fatigue driving is one of the potential factors threatening road safety, and monitoring drivers’ mental state through electroencephalography (EEG) can effectively prevent such risks. In this paper, a new model, DE-GFRJMCMC, is proposed for selecting critical channels and optimal feature subsets from EEG data to improve the accuracy of fatigue driving recognition. The model is validated on the SEED-VIG dataset. The model first selects critical EEG channels using the Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm, extracting important electrode channel information to enhance recognition accuracy. These electrode channels are used to construct a Functional Brain Network (FBN), from which the topological feature set is extracted. Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) is then applied to extract the intrinsic mode components as network nodes, thereby reducing the influence of the number of electrode channels on the brain functional network. The topological features extracted from these components form the suboptimal feature set. To minimize redundant information, we propose an improved Reversible Jump Markov Chain Monte Carlo (RJMCMC) algorithm for selecting the optimal feature subset, ensuring both the efficiency and accuracy of fatigue recognition. The optimal feature subsets were input into various classifiers, and the results showed that the K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN)-based classifier achieved the highest recognition accuracy of 96.11% ± 0.43%, demonstrating the method’s stability and robustness. Compared to similar studies, this model shows superior performance in fatigue driving recognition, which is of significant value for research on fatigue driving detection and prevention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to statistics, approximately 1.19 million people lose their lives each year due to road traffic accidents1, with fatigued driving being one of the direct causes of these accidents2. The occurrence of fatigued driving is influenced by a variety of factors, including monotonous driving environments, long driving times and distances, lack of sleep, chronic sleepiness, and drug or alcohol abuse3,4,5. Driving requires continuous monitoring of the surrounding environment, and prolonged high-intensity attention can lead to driver fatigue, which in turn affects cognitive and operational abilities. Therefore, detecting fatigued driving is critical for improving road safety, as it can help prevent casualties and property losses resulting from traffic accidents.

Currently, fatigue detection technologies for drivers primarily rely on vehicle motion data6, facial recognition7, and physiological signals8 to assess fatigue levels. However, vehicle motion data is subject to delays, which hinder timely fatigue prevention. Facial recognition, on the other hand, is easily affected by external factors, such as lighting and eye obstructions, leading to reduced detection accuracy. Physiological signals can provide real-time and efficient assessment of a driver’s fatigue state. Studies have shown9 that electrocardiogram (ECG) and skin conductance signals offer relatively low accuracy in fatigue detection, while EEG signals are more accurate. Moreover, EEG is considered the “gold standard” for determining driver fatigue10,11,12.

It is worth noting that critical channels in EEG signals can provide the most valuable information for driver fatigue detection13. Studies have shown that extracting critical channels not only effectively reduces computational complexity but also reveals the core roles of specific brain regions during fatigue states14. For example, Chen et al.15 analyzed the changes in EEG covariance matrices learned by the SACC-Caps Net model, which found that the connections in the frontal, parietal, and central regions play important roles in maintaining attention, integrating sensory information, and performing driving tasks. Additionally, Xu et al.16 analyzed dynamic functional networks (DFC) and discovered that as driving time increases, overall efficiency declines, but the brain compensates for the overall functional attenuation by enhancing local information processing capabilities. Proper rest can significantly restore local efficiency and reorganize brain functional networks. Furthermore, the entropy values of brain regions exhibit significant changes under fatigue states, particularly a decrease in complexity in the occipital region at the back of the brain17. This change is likely associated with the occipital lobe’s critical role in visual information processing, where fatigue leads to reduced visual processing efficiency, thereby affecting driving behavior. These findings further validate the potential of EEG signals in fatigue detection. Moreover, the combination of cross-channel feature extraction and deep learning techniques has further enhanced the robustness and accuracy of EEG-based fatigue detection18. The E-Key system, which integrates convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with attention mechanisms, has successfully achieved 97.8% fatigue detection accuracy and 98.5% identity verification accuracy19. Overall, EEG signals, with their high temporal resolution and strong robustness against external interference, demonstrate significant advantages in driver fatigue detection. They not only provide reliable technical support for fatigue detection but also lay a solid theoretical foundation for the development of brain-computer interface (BCI) technology, promoting its widespread application in real-world scenarios.

In EEG signal analysis, EMD is a widely applied signal processing method. By selecting representative EEG channels for EMD processing, more distinguishable features can be extracted, thereby optimizing tasks such as classification and recognition of EEG signals. In related studies, Wang et al.20 applied EMD and autocorrelation coefficients to filter the FP1 and FP2 electrode signals on the forehead, while using Common Spatial Pattern (CSP) to extract EEG variance features. These features were then input into a particle swarm optimization-support vector machine (PSO-SVM) classifier for fusion and optimization, resulting in an accuracy of 95.94%. In the context of driving fatigue detection, Zou et al.21 successfully employed multi-scale entropy based on EMD to identify fatigue, achieving the highest recognition accuracy of 88.74%. Zhang et al.22 used an EMD method based on Hilbert’s yellow transform, achieving an accuracy of 82% for fatigue detection. In summary, EMD is an ideal tool for analyzing EEG signals, as it can effectively handle the nonlinear and nonstationary characteristics of EEG signals. By decomposing the signal into intrinsic mode functions (IMFs), EMD preserves local dynamics, frequency, amplitude information, and time-varying trends, which reflect the original physical properties of the signal and enhance the accuracy and depth of signal analysis23,24,25. Overall, the nonlinear decomposition capability of EMD enables it to more sensitively capture subtle changes in EEG signals, thereby improving the accuracy and stability of fatigue detection.

After extracting the EEG signal feature set using EMD, the optimal feature subset must be selected for driving fatigue recognition. The feature subset is dynamically obtained by traversing different feature dimensions, with an embedded adaptive penalty mechanism to reduce computational complexity and improve recognition accuracy. Momenzadeh et al.26 used hidden Markov models combined with multiple feature criteria for feature selection, demonstrating high robustness and generalization. Wu et al.27 proposed a pipeline-based machine learning approach for cross-checking and complementing Markov boundaries (PM-CCMB) for feature selection, making the selected features more interpretable and enhancing the model’s robustness. Ji and Schmidler28 proposed an adaptive Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method to address the feature selection problem in multimodal scenarios. It is evident that Markov chains are an important tool for feature subset selection.

In summary, EMD is a powerful adaptive signal decomposition tool that performs excellently in fatigue detection, particularly in EEG signal processing, and holds broad application prospects in signal analysis and processing. Markov chains are an important tool for feature subset selection. Based on this, the present study proposes a feature generation framework that combines EMD:

-

(1)

DE is used to select a subset of electrode channels highly correlated with fatigue. EMD is then applied to extract IMFs, construct an FBN, and extract topological features to form a suboptimal set.

-

(2)

Greedy Forward (GF) Selection algorithm is employed to evolve multiple solutions from a high-dimensional feature space and determine various candidate feature subsets. These subsets are input into the RJMCMC for probabilistic evaluation.

-

(3)

The DE-GFRJMCMC model is constructed and tested for fatigue recognition on the SEED-VIG dataset

The structure of this paper is as follows: Sect. 1 introduces the topic; Sect. 2 discusses the selection and extraction of the SEED-VIG dataset; Sect. 3 covers model construction; Sect. 4 presents the results analysis; and Sect. 5 concludes the paper.

SEED-VIG dataset

SEED-VIG is a dataset for driving fatigue alertness estimation provided by Zheng and Lu29. A total of 23 subjects in the dataset (mean age 23 years, 12 females) participated in the experiments, each of which lasted for 2 h. All subjects had normal vision and were prohibited from consuming caffeine, tobacco, and alcohol before participating in the experiments. Most of the experiments were conducted in the late afternoon to increase the likelihood of fatigue. During the experiment, EEG signals were acquired at a rate of 1000 Hz. A total of EEG signals from 17 electrode channels were collected. The channel locations and experimental scenes are shown30 in Fig. 1. In subsequent EEG processing, the sampling rate was reduced to 200 Hz.

Eye movements were recorded using SMI ETG eye-tracking glasses, and PERCLOS values were calculated as alert markers. The formula for calculating the PERCLOS value is shown in Eq. (1), where CLOSE is the eye closure time31. The experiments were calculated every 8 s and 885 times per experiment. In this study, only dichotomous cases were considered, i.e., awake (\(\:PERCLOS<0.4\)) and tired (\(\:PERCLOS\ge\:0.4\)) states. When the data set was analyzed, it was found that subject 13 remained in the tired state throughout the experiment. Therefore, subject 13 was identified as tired (\(\:PERCLOS<0.6\)) versus sleepy (\(\:PERCLOS\ge\:0.6\)).

This study uses the 17 channels of the SEED-VIG dataset to construct the feature set, and calculates PERCLOS from eye-tracking data as the label to assess driver fatigue. By combining EEG and eye-tracking data, the accuracy of fatigue detection in driving can be improved32.

Methodology

Figure 2 illustrates the flow of the critical channels and feature selection framework described in this paper. The DE-GFRJMCMC method proposed in this study involves the following key steps: selecting critical channels using graph optimization; to mitigate the impact of a large number of nodes, EMD is applied to obtain IMFs for constructing the FBN; the topological features of the constructed FBN are then extracted to form a suboptimal set; the GF algorithm is applied to the suboptimal set to identify different candidate feature subsets, which are subsequently evaluated probabilistically using the RJMCMC method.

Differential evolution for EEG Channel selection

DE, as a powerful global optimization method, has been widely applied to complex optimization tasks due to its high robustness, flexibility, and outstanding exploration capability in high-dimensional solution spaces. Compared with other meta-heuristic algorithms, such as Genetic Algorithms (GA) and Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), DE demonstrates significant advantages in feature selection and multi-objective optimization tasks, particularly in balancing feature dimensionality reduction and classification accuracy, enabling the generation of efficient optimization solutions33. For instance, DE excels in handling the nonlinearity and multimodal characteristics of EEG data. When combined with Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT), it effectively identifies the most relevant features, significantly improving the accuracy and efficiency of EEG signal classification34. Furthermore, DE retains exceptional robustness in high-dimensional complex data environments by flexibly adjusting parameters such as mutation factors and crossover probabilities, further solidifying its position as a core tool in the optimization field35. In summary, the Differential Evolution algorithm, with its superior global search capabilities, excellent balance, and strong adaptability to nonlinear and multimodal data, has become a highly promising tool in the fields of feature selection and multi-objective optimization, demonstrating significant value in practical applications such as EEG signal classification and fatigue detection. The specific steps are as follows:

Step 1: Initialization.

-

(1)

Population Initialization. A population of \(\:N\) candidate solutions was initialized. Each candidate solution, denoted as \(\:{X}_{i}^{\left(0\right)}\)for \(\:i=\text{1,2},\cdots\:,N\), represents a potential selection of brain electrical channels. Each candidate \(\:{X}_{i}\) was a binary vector of length \(\:m\), where \(\:m\) was the total number of channels. The binary vector indicates whether a channel was selected (1) or not (0).

$$\:{X}_{i}^{\left(0\right)}=\left[{x}_{i1}^{\left(0\right)},{x}_{i2}^{\left(0\right)},\cdots\:,{x}_{im}^{\left(0\right)}\right],\:{x}_{i1}^{\left(0\right)}\in\:\left\{\text{0,1}\right\} $$ -

(2)

Fitness Function. The fitness of each candidate solution is evaluated using a predefined objective function \(\:f\left({X}_{i}\right)\), which measures the quality of the selected channels:

$$\:f\left({X}_{i}\right)=computeEnergy\left(S\left({X}_{i}\right)\right)$$where \(\:S\left({X}_{i}\right)\) was the set of selected channels corresponding to the non-zero entries of \(\:{X}_{i}\).

Step 2: Mutation.

Differential mutation. For each candidate \(\:{X}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\), a mutant vector \(\:{V}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\) was generated by combining three distinct individuals \(\:{X}_{r1}^{\left(t\right)}\), \(\:{X}_{r2}^{\left(t\right)}\), \(\:{X}_{r3}^{\left(t\right)}\) randomly selected from the population, where \(\:{r}_{1}\ne\:{r}_{2}\ne\:{r}_{3}\ne\:i\).

F is a scaling factor that controls the amplification of the differential variation. To ensure a binary vector, the mutant vector is multiplied by 2:

Step 3: Crossover.

Binomial crossover. A trial vector \(\:{u}_{i}^{\left(t+1\right)}\) was generated by mixing the components of the mutant vector \(\:{V}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\) with the target vector \(\:{X}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\). The crossover operation is controlled by a crossover probability \(\:{C}_{r}\).

The trial vector is also ensured to be a binary vector:

Step 4: Selection and Iteration.

-

(1)

Fitness Evaluation. The fitness of the trial vector \(\:{U}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\) was evaluated using the objective function \(\:f\left({U}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\right)\):

$$\:f\left({U}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\right)=computeEnergy\left(S\left({U}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\right)\right)$$The trial vector is accepted as the next generation candidate if its fitness is better than the current candidate \(\:{X}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\):

$$\:{X}_{i}^{\left(t+1\right)}=\left\{\begin{array}{c}{U}_{i}^{\left(t\right)},if\:f\left({U}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\right)>f\left({X}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\right)\\\:{X}_{i}^{\left(t\right)},otherwise\end{array}\right.$$ -

(2)

Best solution tracking. The best individual and its fitness are tracked during the optimization process. If the fitness of \(\:{U}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\) is better than the current best fitness, update the best solution. If \(\:f\left({U}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\right)<\text{b}\text{e}\text{s}\text{t}\text{F}\text{i}\text{t}\text{n}\text{e}\text{s}\text{s}\), bestIndividual =\(\:\:{U}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\), bestFitness = \(\:f\left({U}_{i}^{\left(t\right)}\right)\).

-

(3)

Evolution process. The process of mutation, crossover, and selection is repeated for a predefined number of generations G or until convergence is achieved.

-

(4)

Optimal channel selection. The best individual bestIndividual after G generations represents the optimal subset of channels that minimize the objective function.

IMF-FBN

Functional brain networks effectively measure correlations between brain regions, but their construction is influenced by electrode channels36. To overcome this limitation, we decompose EEG signals using EMD, with the IMF components serving as network nodes to construct functional brain networks37.

IMF-FBN Construction

Firstly, the EEG with the number of channels N is denoted as:

Let each sampled EEG data (denoted as \(\:{X}_{i}\)) contain Sampling time \(\:T\) for collecting EEG signals, and the sampled data with \(\:f\) as the sampling frequency be denoted as:

where \(\:{x}_{i,j}\)denotes the \(\:j\)th sampled data value of the \(\:i\)th electrode. \(\:L\) is the total length of the data and \(\:L=T\times\:f\).

Taking the sampling data \(\:{X}_{i}\) as an example, the following steps for constructing the FBN are briefly described as follows.

Step 1: EMD.

EMD is performed on \(\:{X}_{i}\)38. After finite iterations, the original signal \(\:x\left(t\right)\) was decomposed into a finite set of IMFs. A new set of EEG data can be obtained by computing the raw information from all EEG channels in turn and is noted as.

Where, \(\:{IMF}_{i,j}\) is the \(\:j\)th IMF component of electrode \(\:i\). The procedure of the proposed method is illustrated in Algorithm 1.

Step 2: Calculate the correlation between IMF (without losing generality, taking the Phase lock value (PLV) as an example, PLV is an effective method for analyzing connectivity in EEG signals, quantifying the phase synchrony between EEG channels39,40. It captures the phase synchrony of different frequency components within EEG signals, reflecting the interdependence between signals. This method is particularly suitable for nonlinear and non-stationary EEG signals, and is effective in revealing the dynamic changes in brain functional networks.) and construct the correlation matrix.

Phase locking can reflect the functional connectivity of the brain. The Fast Fourier Transform is applied to the Intrinsic Mode Functions D, resulting in \(\:F=\left\{{f}_{1},{f}_{2},\cdots\:,{f}_{N}\:\right\}\). The PLV between each pair of signals \(\:\left(x,y\right)\) is then calculated:

Then, the element \(\:{M}_{plv}\left(i,j\right)\) of the adjacency matrix \(\:{M}_{plv}\) is determined based on PLV. The formula can be expressed as:

Step 3: Threshold selection.

Since the FBN based on \(\:{M}_{plv}\) is a fully connected network, this network is too complex and does not effectively reflect the relationship between channels41. Therefore, we will simplify the fully connected network based on the scale threshold and select effective edges with a scale threshold \(\:t=0.2\)42. Based on threshold \(\:t\), the correlation matrix is binarized to generate an adjacency matrix. Calculation rules can be described as:

\(\:{M}_{plv}\left(i,j\right)\) here reflects the connection among the EEG electrode channels, and the resulting adjacency matrix is denoted as \(\:{M}_{binaryzation}\).

Topological feature extraction of networks

In the study of brain functional networks, Node Strength (NS), Clustering Coefficient (CC), and Eigenvector Centrality (EC) are commonly used topological features that reveal the structural characteristics of brain functional networks from different perspectives, including local connection strength, local modular characteristics, and global network importance.

NS quantifies the total connection weight between a node and other nodes, reflecting the functional strength and importance of the node within the local network. In fatigue states, abnormal increases or decreases in brain region activity are often reflected by changes in NS, providing important insights into the physiological mechanisms related to fatigue.

CC measures the ability of a node to form local clusters, describing the localized properties of the network. It reveals the level of cooperation between nodes and their neighbors in the brain functional network and reflects the impact of fatigue on network modularity and local clustering characteristics.

EC, as a global topological feature, measures the importance of a node within the entire network, taking into account not only the node’s own connections but also its connections with other influential nodes. Changes in the global role of certain key brain regions under fatigue states can be captured using EC.

To comprehensively reveal the effects of fatigue on brain functional networks, these three indicators—NS, CC, and EC—are integrated to analyze the topological characteristics of brain functional networks from both local and global perspectives. The specific calculation formulas are as follows:

-

(1)

NS. Strength is the weighted variable of degree or the sum of the weights of all adjacent links. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

$$\begin{array}{*{20}c} {s_{i}^{w} = \mathop \sum \limits_{{j \in N}} w_{{ij}} } \\ \end{array}$$(4)where \(\:i\) represents the number of nodes, \(\:j\) represents the number of samples, and \(\:w\) represents the connectivity matrix.

-

(2)

CC. Used to describe the degree of aggregation of nodes in the network42,43. The CC value of node i is represented by \(\:{C}_{i}\), see the formula

$$\begin{array}{*{20}c} {C = \frac{1}{n}\mathop \sum \limits_{{i \in N}} C_{i} = \frac{1}{n}\mathop \sum \limits_{{i \in N}} \frac{{2t_{i} }}{{k_{i} \left( {k_{i} - 1} \right)}}} \\ \end{array}$$(5)In the command, \(\:{t}_{i}\) refers to the actual number of connected edges and the maximum possible number of connected edges \(\:{k}_{i}\left({k}_{i}-1\right)/2\).

-

(3)

EC. Eigenvector centers reflect the importance of node connection contributions. The specific calculation formula is as follows:

$$\begin{array}{*{20}c} {x_{i} = c\mathop \sum \limits_{{j = i}}^{n} a_{{ij}} x_{j} } \\ \end{array}$$(6)

Where \(\:c\) is the proportionality constant, denoted by \(\:x={\left[{x}_{1},{x}_{2},{x}_{3},\cdots\:,{x}_{n}\right]}^{T}\), when the steady state is obtained after many iterations, it can be denoted by the following matrix form, where \(\:x\) is expressed as the eigenvector corresponding to the eigenvalue \(\:{c}^{-1}\) of matrix \(\:A\):

Here \(\:x\) is denoted as the eigenvector corresponding to the eigenvalue \(\:{c}^{-1}\) of the matrix \(\:A\).

GFRJMCMC feature selection

The combined Greedy Forward Selection and RJMCMC approach effectively selects an optimal subset of features. The greedy step quickly identifies a promising subset44, while the RJMCMC refinement explores the model space more thoroughly to ensure that the selected subset is optimal45. This method balances computational efficiency with the thoroughness needed to find the best feature set for the task.

Step 1: Initialization.

-

(1)

Feature Set Initialization. Let \(\:F=\left\{{f}_{1},{f}_{2},\cdots\:,{f}_{m}\right\}\) represent the full set of m features. Initialize the selected feature subset \(\:{S}^{\left(0\right)}\) as an empty set: \(\:{S}^{\left(0\right)}=\varnothing\:\). Define the target number of features to select as k, where k represents the number of selected features.

-

(2)

Objective Function. Define the objective function \(\:f\left(S\right)\) that evaluates the quality of a feature subset \(\:F\). This could be based on the cross-validated loss of a k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN) model:

$$\:f\left(S\right)=kfoldLoss\left(crossval\right(fitcknn({X}_{S},y),{\prime\:}KFold{\prime\:},5\left)\right)$$where \(\:{X}_{S}\) was the dataset restricted to the features in \(\:S\), and \(\:y\) was the target variable.

Step2: Greedy Forward Selection.

-

(1)

Greedy Addition. For each feature \(\:{f}_{i}\in\:F/{S}^{\left(t\right)}\), evaluate the performance of adding \(\:{f}_{i}\) to the current subset \(\:{S}^{\left(t\right)}\).

$$\:Compute\:f\left({S}^{\left(t\right)}\cup\:\left\{{f}_{i}\right\}\right)\:for\:each\:{f}_{i}\in\:F/{S}^{\left(t\right)}$$Select the feature \(\:{f}^{*}\) that results in the lowest cross-validated loss:

$$\:{f}^{*}=arg\underset{{f}_{i}\in\:F/{S}^{\left(t\right)}}{\text{min}}f\left({S}^{\left(t\right)}\cup\:\left\{{f}_{i}\right\}\right)$$Update the selected subset:

$$\:{S}^{\left(t+1\right)}={S}^{\left(t\right)}\cup\:\left\{{f}^{*}\right\}$$ -

(2)

Stopping Criterion. Continue adding features until no further improvement is achieved or the target number of features k is reached:

$$\:If\:\left|{S}^{\left(t+1\right)}\right|\ge\:k,\:stop\:$$

Step 3: RJMCMC Refinement.

-

(1)

Posterior Probability Calculation. After GF identifies a promising set of candidate feature subsets, RJMCMC is employed to refine the selection by exploring the model space more thoroughly. The posterior probability of a feature subset \(\:{M}_{k}\) given the data is computed:

$$\:P\left({M}_{k}|Data\right)\propto\:P\left(Data|{M}_{k}\right)\cdot\:P\left({M}_{k}\right)$$where \(\:P\left({M}_{k}|Data\right)\) is the likelihood and \(\:P\left({M}_{k}\right)\) is the prior probability of the model \(\:{M}_{k}\).

The RJMCMC algorithm refines the feature subset by sampling from the posterior distribution. Propose a new feature subset \(\:{M}_{k}^{{\prime\:}}\) by either adding or removing a feature from the current subset \(\:{M}_{k}\):

$$\:{M}_{k}^{{\prime\:}}=\left\{\begin{array}{c}{M}_{k}+\left\{{f}_{i}\right\},\:with\:probability\:{p}_{a}\\\:{M}_{k}-\left\{{f}_{i}\right\},with\:probability\:{p}_{b}\end{array}\right.$$where \(\:{f}_{i}\) is a feature in F, and \(\:{p}_{a}\) and \(\:{p}_{b}\) are probabilities for adding and removing features, respectively.

-

(2)

Acceptance Criterion. The proposed model \(\:{M}_{k}^{{\prime\:}}\) is accepted with probability:

$$\:\alpha\:=min\left(1,\frac{P\left({M}_{k}^{{\prime\:}}|Data\right)}{P\left({M}_{k}|Data\right)}\cdot\:\frac{q\left({M}_{k}|{M}_{k}^{{\prime\:}}\right)}{q\left({M}_{k}^{{\prime\:}}|{M}_{k}\right)}\right)$$where \(\:q\left({M}_{k},{M}_{k}^{{\prime\:}}\right)\) is the proposal distribution. Repeat the proposal and acceptance steps for a predefined number of iterations N or until convergence:

$$\:If\:\left|{M}_{k}^{{\prime\:}}\right|\ge\:k,\:stop\:$$

Step 4: Final Feature Subset Selection.

The final subset of features \(\:{S}^{*}\) was the one that achieves the lowest cross-validated loss after the RJMCMC refinement:

Classification

Cognition classification is affected by the classifier. Therefore, choosing a suitable classifier is particularly important. Because EEG data are nonlinear and non-smooth, the results obtained from the classification of different classifiers can be different. To find the optimal combination of classifications, in this study, the following six classifiers are used: KNN46, SVM47, Decision Tree (DT)48, Bayesian Network (BN)49 and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA)50.

Feature smoothing

The degree of driver fatigue evolves gradually over time, with associated fluctuations in fatigue-related characteristics that must be appropriately managed. Applying feature smoothing techniques to reduce noise and account for potential trends can enhance the accuracy and reliability of fatigue detection. Kalman filter has real-time performance in curve smoothing, strong noise rejection, good dynamic adaptability51,52. The effectiveness of Kalman filter has been well established in previous studies53. Consequently, this study employs a Kalman filter to smooth the features, thereby improving the robustness of fatigue identification.

Results and discussion

Model performance evaluation

In order to verify the rationality of the model design, we conduct ablation experiments on the model to reveal the importance of modules in the model, enhance the interpretability of the model, and ensure the robustness of the model. Table 1 below presents the detection performance of model pairs for fatigue under ablation experiments.

In terms of overall performance, the feature selection strategies employed by different models had a significant impact on their effectiveness. The featureless selection approach consistently served as the benchmark method, achieving 80.86% accuracy, an F1 score of 81.36%, and an AUC of 92.86%, but it lacked feature optimization capabilities. Greedy Forward Selection exhibited a decrease in performance (72.60% accuracy, 72.60% F1 score, and 90.14% AUC), indicating that this method may have omitted critical features. Similarly, RJCMC, when used independently, achieved performance comparable to the benchmark (80.82% accuracy, 81.31% F1 score, and 92.86% AUC), suggesting that its optimization capabilities are also limited. However, when Greedy Forward Selection was combined with RJCMC, the model’s performance was significantly enhanced, achieving an accuracy of 96.11%, an F1 score of 96.07%, and an AUC of 99.29%. This improvement suggests that the two methods complement each other in feature selection, leading to enhanced model performance. The ablation experiments further demonstrated that individual feature selection methods have limitations in capturing key features, whereas the combination of Greedy Forward Selection and RJCMC effectively addresses these limitations, significantly improving model performance. These results underscore the importance of a well-designed feature selection strategy in enhancing the effectiveness of classification models and highlight the advantages of synergistically optimizing multiple feature selection methods.

Critical channel selection

We used differential evolution to evaluate critical EEG channels, with the results shown in Table 2. Statistical analysis indicates that O1, OZ, O2, POZ, TP7, and TP8 are the top six critical channels among the 23 subjects. These findings suggest that most critical pathways related to fatigue recognition originate from the occipital lobe, with the temporal lobe contributing less, highlighting the occipital lobe’s significant role in fatigue recognition54. The occipital lobe, primarily responsible for visual processing, is crucial for monitoring road safety and responding to external stimuli. It is strongly linked to visual tasks13,55 and reflects changes in brain activity during driver fatigue.

As fatigue sets in, the brain’s ability to process visual information declines. Studies have shown55 that the occipital region, a key area in brain functional networks, undergoes significant changes during driver fatigue, making it an effective feature for fatigue detection. Therefore, the occipital lobe can serve as a crucial region for detecting these changes. As fatigue progresses, it diminishes the brain’s information processing capacity, reducing visual processing efficiency, slowing reaction times, and lowering alertness. This makes the occipital lobe central to recognizing early signs of fatigue. This finding aligns with Zhang et al.56, who concluded that the occipital lobe is essential for coordinating brain activities, particularly across different states of consciousness.

Although the temporal lobe plays a smaller role, it contributes to auditory processing and memory functions, which are also relevant for fatigue recognition57. Studies58,59 have shown that the temporal lobe, particularly the auditory cortex and hippocampus, is essential for processing auditory stimuli and storing them in working or long-term memory. This ability is crucial for interpreting complex auditory patterns, such as recognizing changes in pitch or rhythm, which may indicate fatigue. Moreover, research has found that the left temporal lobe contains more information related to driver fatigue14. The optimal channel scheme selected by differential evolution does not isolate any single brain region, suggesting that the impact of fatigue is not confined to one area but involves comprehensive processing across multiple brain regions, in line with previous studies60. In conclusion, the predominance of the occipital lobe in fatigue recognition highlights its critical role in visual processing and attention maintenance, both of which are essential for detecting and recognizing fatigue.

To assess the impact of critical channels on the global functional brain network, we evaluated them using global efficiency. Previous studies61 have shown that global efficiency significantly decreases under fatigue, indicating a reduction in the efficiency of information transfer between brain regions, which leads to a decline in overall information processing capacity. The results, presented in Table 3, show that removing critical EEG electrode channels causes a decrease in global efficiency, consistent with previous findings61. This suggests that critical electrode channels are crucial for efficient information transfer within the brain’s functional network. As global efficiency decreases, so does the efficiency of information propagation, reflecting a reduced ability of the brain to process and transfer information in a fatigued state. This underscores the importance of these channels in analyzing fatigue states, as confirmed by previous studies62,63. It also further highlights the effectiveness of differential evolution in selecting critical channels.

Fatigue identification of critical channels

Previous studies have shown that node strength, clustering coefficients, and eigenvector centrality are key indicators of network importance64 and are also beneficial for recognition tasks62. In this study, based on the proposed framework, node strength, clustering coefficient, and eigenvector centrality were selected to form the feature subset. These feature subsets were then input into five classical classifiers, with Kalman filtering applied for fatigue recognition. To evaluate the generalization performance of the framework, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, F1 score, and AUC were used as evaluation metrics. Additionally, K-fold cross-validation offers a reliable method for performance evaluation and helps mitigate model overfitting. Accordingly, this study used five-fold cross-validation65, conducting 50 training sessions, and the final results were averaged across these 50 tests.

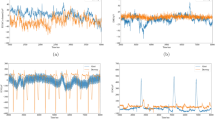

As shown in Figs. 3 and 4, and 5, the clustering coefficient yields the best recognition performance for fatigue detection, achieving the highest results with the KNN classifier. The accuracy was 96.11%±0.43%, sensitivity 96.12%±0.43%, specificity 95.50%±0.60%, F1 score 96.07%±0.44%, and AUC 99.29%±0.15%. Compared to node strength, the clustering coefficient showed a 0.5% higher accuracy, 0.51% higher sensitivity, 0.91% higher specificity, 0.51% higher F1 score, and 0.21% higher AUC. Compared to eigenvector centrality, it was 3.23% higher in accuracy, 3.24% higher in sensitivity, 2.67% higher in specificity, 3.21% higher in F1 score, and 4.99% higher in AUC. These results demonstrate the clustering coefficient’s effectiveness in fatigue recognition. Node strength exhibited the second-best recognition performance, also achieving the highest results with the KNN classifier. Eigenvector centrality achieved the third-best performance, with the highest recognition accuracy in the decision tree classifier.

Additionally, we found a positive correlation between the clustering coefficient and the passage of time. For instance, in the sixth subject, as shown in the figure, the increase in the clustering coefficient suggests that connectivity between nodes in the brain network strengthens, thereby enhancing the processing of local information66,67. Research64 has shown that brain network topological features, such as Functional Connectivity (FC) and the clustering coefficient, are influenced by temporal autocorrelation. Regions with higher temporal autocorrelation tend to show higher FC and clustering coefficients. Moreover, clustering in brain networks is closely related to working memory68. Therefore, during mental fatigue, the brain compensates for fatigue by strengthening communication within local brain regions. This finding aligns with previous fatigue studies.

To evaluate the performance of the best feature subsets, five classical classifiers (BN, DT, SVM, LDA, KNN) were employed. The results, presented in Figs. 3 and 4, and 5, indicate that node strength and the clustering coefficient demonstrate good recognition performance and robustness when using the KNN classifier, while eigenvector centrality shows good performance and robustness with the decision tree classifier. Further analysis suggests that KNN’s superior performance with node strength and the clustering coefficient can be attributed to its non-parametric nature and ability to capture local dependencies and nonlinear relationships in the data69. KNN, as a non-parametric algorithm, does not assume a specific data distribution. It can flexibly adapt to complex datasets and capture local patterns and structures. This proximity-based classification method determines the class based on nearest neighbors, effectively reflecting the local relational characteristics of the data. It is particularly suited for indicators like node strength and clustering coefficient that describe local connectivity patterns. In contrast, classifiers such as SVM, Bayes, and decision trees may struggle to efficiently handle the complex structures of network-derived features. These classifiers often rely on specific model assumptions or decision rules, making it difficult to flexibly capture local patterns and complex associations, potentially leading to variations in recognition accuracy. Therefore, future classifier selection should consider the properties of the features and the underlying data distribution.

The results of the current driver fatigue related studies using the SEED-VIG dataset are analyzed in Table 4:

It can be seen that the fatigue recognition accuracy of DE-GFRJMCMC reaches 96.11% (± 0.43%) using the same dataset, which improves the fatigue recognition accuracy of our method compared to previous work78. Comparing these methods, we believe that the feature selection framework based on DE-GFRJMCMC has some advantages in driving fatigue recognition.

Limitations and future work

Although this study proposes a new approach to feature extraction and verifies the effectiveness of the new features by comparing them with traditional entropy values and common brain network topology features. However, there are some limitations in this study:

-

(1)

PLV is susceptible to volume conduction effects, causing false positive inference.

This study constructs brain functional networks based on PLV, which holds significant value in building functional brain networks and analyzing neural connectivity. However, its inherent sensitivity to volume conduction effects is a major limitation. This sensitivity can lead to spurious synchronization and false positive inferences, thereby affecting the reliability of functional brain networks and the accuracy of subsequent analyses. To address this limitation, future studies could consider adopting more robust functional connectivity measures against volume conduction effects, such as the Weighted Phase Lag Index (wPLI), Weighted Functional Connectivity Strength (wPLI-delta), or Corrected Phase Locking Value (Corrected PLV), which focus on non-zero phase lag connections and effectively reduce spurious synchronization effects. Additionally, integrating PLV with source localization techniques (e.g., sLORETA or beamforming) and Independent Component Analysis (ICA) could help eliminate collinear signals caused by volume conduction, reconstruct the true sources of neural activity, and enhance the interpretability of brain network structures.

-

(2)

In this paper, only three topological features among multiple network topological features were selected for analysis, and more features can be introduced to detect fatigue driving EEG signals in subsequent studies.

This study focuses on three topological features that effectively capture key changes in brain networks under fatigue states: NS, CC, and EC, which respectively measure local connectivity strength, modular characteristics, and global network influence. However, the study does not fully encompass other important features, such as characteristic path length, small-worldness, and betweenness centrality, which may further reveal the complex effects of fatigue on functional brain networks. Future research could expand to a broader feature set to capture the temporal dynamics of fatigue. Additionally, more advanced algorithms for feature selection and dimensionality reduction could be introduced to reduce computational complexity and mitigate the risk of overfitting.

The DE-GFRJMCMC feature selection method proposed in this study effectively improves the accuracy of fatigue identification, and has application potential in vehicle early warning system to improve road safety. In future research, the integration of multi-source information, such as driver’s facial features or electrocardiogram, can be explored to further improve feature accuracy and comprehensiveness.

Conclusion

This paper presents a feature screening method based on the DE critical EEG electrode channels selection framework and GFRJMCMC optimal feature subset screening for fatigue recognition. This method uses EEG data from critical channels and optimal topological feature subset constructed by IMF-FBN to identify driver fatigue. The open dataset SEED-VIG was used to verify the method, achieving a classification accuracy of 96.11. The analysis of recognition performance shows that the feature optimization framework based on DE-GFRJMCMC has high classification accuracy. Fatigue recognition using this framework can provide insight into the driver’s true fatigue state, as EEG signal information cannot be falsified. This approach will lead to more accurate identification of driver fatigue in the future.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from BCMI Laboratory, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. Data are available https://bcmi.sjtu.edu.cn/home/seed/seed-vig.html with the permission of BCMI Laboratory, Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

References

Organization, W. H. Global Status Report on Road Safety 2023 (World Health Organization, 2023).

Zhang, G., Yau, K. K., Zhang, X. & Li, Y. Traffic accidents involving fatigue driving and their extent of casualties. Accid. Anal. Prev. 87, 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2015.10.033 (2016). Epub 20151127.

Ting, P. H., Hwang, J. R., Doong, J. L. & Jeng, M. C. Driver fatigue and highway driving: A simulator study. Physiol. Behav. 94(3), 448–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.02.015 (2008). Epub 20080302.

Nilsson, T., Nelson, T. M. & Carlson, D. Development of fatigue symptoms during simulated driving. Accid. Anal. Prev. 29(4), 479–488 (1997).

Hu, S. et al. Efficient detection of driver fatigue state based on all-weather illumination scenarios. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 17075. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67131-5 (2024).

Hou, J. J. et al. A systematic review for the fatigue driving behavior recognition method. J. Intell. FUZZY Syst. 46(1), 1407–1427. https://doi.org/10.3233/JIFS-235075 (2024). PubMed PMID: WOS:001163267400090.

Lin, N. & Zuo, Y. Advancing driver fatigue detection in diverse lighting conditions for assisted driving vehicles with enhanced facial recognition technologies. PLOS ONE. 19(7), e0304669. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0304669 (2024).

Zong, S. J. et al. Application and challenges of EEG signals in fatigue driving detection. PROGRESS Biochem. Biophys. 51(7), 1645–1669. https://doi.org/10.16476/j.pibb.2023.0399 (2024). PubMed PMID: WOS:001282146600012.

Nalwaya, A., Das, K. & Pachori, R. B. Automated emotion identification using fourier–bessel domain-based entropies. Entropy 24(10), 1322. https://doi.org/10.3390/e24101322 (2022). PubMed PMID: 37420342.

Zhang, W. et al. Partial directed coherence based graph convolutional neural networks for driving fatigue detection. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 91(7), 074713 (2020).

Wu, E. Q. et al. Novel nonlinear approach for real-time fatigue EEG data: An infinitely warped model of weighted permutation entropy. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 21(6) 2437–2448. https://doi.org/10.1109/tits.2019.2918438. (2020).

Othmani, A. et al. EEG-based neural networks approaches for fatigue and drowsiness detection: a survey. Neurocomputing 557, 126709. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2023.126709 (2023).

Wang, H., Xu, L., Bezerianos, A., Chen, C. & Zhang, Z. Linking attention-based Multiscale CNN with Dynamical GCN for driving fatigue detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 70, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1109/tim.2020.3047502 (2021).

Tang, J. et al. Attention-guided multiscale convolutional neural network for driving fatigue detection. IEEE Sens. J. 24(14), 23280–23290. https://doi.org/10.1109/jsen.2024.3406047 (2024).

Chen, C. et al. Self-attentive channel-connectivity capsule network for EEG-based driving fatigue detection. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil Eng. 31, 3152–3162 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2023.3299156

Xu, T. et al. Effects of rest-break on mental fatigue recovery based on EEG dynamic functional connectivity. Biomed. Sign. Process. Control. 77, 103806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2022.103806 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Driving fatigue classification based on fusion entropy analysis combining EOG and EEG. IEEE Access. 7, 61975–61986. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2019.2915533 (2019).

WANG Hongtao, Y. H. et al. A review of driving fatigue detection based on EEG signals. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 50(11), 54–65. https://doi.org/10.13245/j.hust.221105 (2022).

Xu, T. et al. E-Key: an EEG-Based biometric authentication and driving fatigue detection system. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 14(2), 864–877. https://doi.org/10.1109/taffc.2021.3133443 (2023).

Wang, M. et al. Eye blink artifact detection based on multi-dimensional EEG feature fusion and optimization. Biomedical Signal Processing and Contro. 83, 104657. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc (2023).

Zou, S., Qiu, T., Huang, P., Bai, X. & Liu, C. Constructing multi-scale entropy based on the empirical mode decomposition(EMD) and its application in recognizing driving fatigue. J. Neurosci. Methods 341, 108691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2020.108691 (2020). Epub 20200526.

Zhang, M. et al. Research on driver’s fatigue detection based on Information fusion. Comput. Mater. Contin. 79(1), 1039–1061. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2024.048643 (2024).

Dong, J., Zhang, Y. & Hu, J. Short-term air quality prediction based on EMD-transformer-BiLSTM. Sci. Rep. 14(1), 20513. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-67626-1 (2024).

Yuzgec, U., Dokur, E. & Balci, M. A novel hybrid model based on empirical mode decomposition and Echo state network for wind power forecasting. Energy 300, 131546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2024.131546 (2024).

Brindha, G. S. & Manjula, J. (eds) Empirical mode decomposition (EMD) based denoising method for heart sound signal and its performance analysis. in 1st International Conference on Cognitive, Green and Ubiquitous Computing (IC-CGU) (2024).

Momenzadeh, M., Sehhati, M. & Rabbani, H. A novel feature selection method for microarray data classification based on hidden Markov model. J. Biomed. Inform. 95, 103213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2019.103213 (2019).

Wu, X., Jiang, B., Yu, K., c, M. & Chen, H. Accurate Markov boundary discovery for causal feature selection. IEEE Trans. Cybernet. 50(12), 4983–4996. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCYB.2019.2940509 (2020).

Ji, C. & Schmidler, S. C. Adaptive Markov Chain Monte Carlo for bayesian variable selection. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 22(3), 708–728. https://doi.org/10.1080/10618600.2013.819178 (2013).

Zheng, W. L. & Lu, B. L. A multimodal approach to estimating vigilance using EEG and forehead EOG. J. Neural Eng. 14(2), 0260171–0260114 (2017).

Zheng, W-L. & Lu, B-L. A multimodal approach to estimating vigilance using EEG and forehead EOG. J. Neural Eng. 14(2), 026017. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/aa5a98 (2017).

Gao, X. Y., Zhang, Y. F., Zheng, W. L. & Lu, B. L. (eds) Evaluating Driving Fatigue Detection Algorithms Using eye Tracking Glasses (IEEE, 2015).

Lian, Z. et al. Driving fatigue detection based on hybrid electroencephalography and eye tracking. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 28(11), 6568–6580. https://doi.org/10.1109/jbhi.2024.3446952 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Gong, D., Gao, X., Tian, T. & Sun, X. Binary differential evolution with self-learning for multi-objective feature selection. Inf. Sci. 507, 67–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2019.08.040 (2020).

al-Qerem, A., Kharbat, F., Nashwan, S., Ashraf, S. & blaou k. General model for best feature extraction of EEG using discrete wavelet transform wavelet family and differential evolution. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 16(3), 1550147720911009. https://doi.org/10.1177/1550147720911009 (2020).

Bilal, Pant, M., Zaheer, H., Garcia-Hernandez, L. & Abraham, A. Differential evolution: A review of more than two decades of research. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 90, 103479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engappai.2020.103479 (2020).

Joudaki, A., Salehi, N., Jalili, M. & Knyazeva, M. G. EEG-Based functional brain networks: Does the network size Matter? PLOS ONE 7(4), e35673. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0035673 (2012).

Zheng, R., Wang, Z., He, Y. & Zhang, J. EEG-based brain functional connectivity representation using amplitude locking value for fatigue-driving recognition. Cogn. Neurodyn. 16(2), 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11571-021-09714-w (2022).

Huang, N. E. et al. The empirical mode decomposition and the Hilbert spectrum for nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 454(1971) 903-95 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1998.0193

Wang, Z-M., Zhou, R., He, Y. & Guo, X-M. Functional integration and separation of Brain Network based on phase locking value during emotion Processing. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 15(2), 444–453. https://doi.org/10.1109/tcds.2020.3001642 (2023).

Su, R. et al. Constructing biomarker for early diagnosis of aMCI based on combination of multiscale fuzzy entropy and functional brain connectivity. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control. 70, 103000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc (2021).

Peng, Y., Qiu, T. & Wei, L. An Approach to Extracting Graph Kernel Features from Functional Brain Networks and Its Applications to the Analysis of the Noisy EEG Signals. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control. 80, 104269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2022.104269 (2023).

Rubinov, M. & Sporns, O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: Uses and interpretations. Neuroimage 52(3), 1059–1069. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.003 (2010).

Watts, D. J. & Strogatz, S. H. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature (1998).

Borboudakis, G. & Tsamardinos, I. Extending greedy feature selection algorithms to multiple solutions. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 35 (4), 1393–1434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10618-020-00731-7 (2021).

Liu, Y., Yang, C., Li, H. D. & Wang, J. IsoFrog: a reversible jump Markov Chain Monte Carlo feature selection-based method for predicting isoform functions. Bioinformatics 39(9), btad530 https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btad530 (2023).

Li, C. et al. Using the K-nearest neighbor algorithm for the classification of lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2012, 876545. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/876545 (2012).

Brinkmann, B. H. et al. Forecasting seizures using intracranial EEG measures and SVM in naturally occurring canine epilepsy. PLoS One 10(8), e0133900. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0133900 (2015).

Wang, G., Deng, Z. & Choi, K-S. Detection of epilepsy with electroencephalogram using rule-based classifiers. Neurocomputing 228, 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2016.09.080 (2017).

Feng, P. M., Ding, H., Chen, W. & Lin, H. Naive Bayes classifier with feature selection to identify phage virion proteins. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2013, 530696. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/530696 (2013).

Tahernezhad-Javazm, F., Azimirad, V. & Shoaran, M. A review and experimental study on the application of classifiers and evolutionary algorithms in EEG-based brain-machine interface systems. J. Neural Eng. 15(2), 021007. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/aa8063 (2018).

Bai, Y., Yan, B., Zhou, C., Su, T. & Jin, X. State of art on state estimation: Kalman filter driven by machine learning. Annu. Rev. Control. 56, 100909 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arcontrol.2023.100909 (2023).

Zhao, S. & Huang, B. Trial-and-error or avoiding a guess? Initialization of the Kalman filter. Automatica 121, 109184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.automatica.2020.109184 (2020).

Huang, Y., Zhu, F., Jia, G. & Zhang, Y. A slide window variational adaptive Kalman filter. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 67(12), 3552–3556. https://doi.org/10.1109/TCSII.2020.2995714 (2020).

Qin, Y. et al. Directed brain network analysis for fatigue driving based on EEG source signals. Entropy (Basel) 24(8), 1093. https://doi.org/10.3390/e24081093 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Driving fatigue recognition with functional connectivity based on phase synchronization. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 13(3), 668–678. https://doi.org/10.1109/tcds.2020.2985539 (2021).

Zhang, Y. & Zhu, C. Assessing brain networks by resting-state dynamic functional connectivity: An fNIRS-EEG study. Front. Neurosci. 13, 1430. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.01430 (2019).

Liu, R., Qi, S., Hao, S., Lian, G. & Luo, Y. Using electroencephalography to analyse drivers’ different cognitive workload characteristics based on on-road experiment. Front. Psychol. 14, 1107176. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1107176 (2023). Epub 20230424.

Kumar, S. et al. A Brain system for auditory working memory. J. Neurosci. 36(16), 4492–4505. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4341-14.2016 (2016).

Kaiser, J. Dynamics of auditory working memory. Front. Psychol. 6, 613. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00613 (2015). Epub 20150511.

Qu, G. et al. A hybrid critical channel selection framework for EEG emotion recognition. IEEE Sens. J. 24(9), 14881–14893. https://doi.org/10.1109/jsen.2024.3380749 (2024).

Wang, H. et al. Dynamic reorganization of functional connectivity unmasks fatigue related performance declines in simulated driving. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 28(8), 1790–1799. https://doi.org/10.1109/tnsre.2020.2999599 (2020).

Wu, X., Zheng, W-L., Li, Z. & Lu, B-L. Investigating EEG-based functional connectivity patterns for multimodal emotion recognition. J. Neural Eng. 19(1), 016012. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/ac49a7 (2022).

Wang, F., Wu, S., Ping, J., Xu, Z. & Chu, H. EEG driving fatigue detection with PDC-based brain functional network. IEEE Sens. J. 21(9), 10811–10823. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2021.3058658 (2021).

Shinn, M. et al. Spatial and temporal autocorrelation weave complexity in brain networks. bioRxiv 2021.06.01.446561 https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.01.446561 (2022).

Sakti, W. W., Anam, K., Utomo, S. B., Marhaenanto, B. & Nahela, S. (eds) Artificial intelligence IoT based EEG application using deep learning for movement classification. in 2021 8th International Conference on Electrical Engineering, Computer Science and Informatics (EECSI) (2021).

Han, C., Sun, X., Yang, Y., Che, Y. & Qin, Y. Brain complex network characteristic analysis of fatigue during simulated driving based on electroencephalogram signals. Entropy 21(4). https://doi.org/10.3390/e21040353 (2019).

Dimitrakopoulos, G. N. et al. Functional connectivity analysis of mental fatigue reveals different network topological alterations between driving and vigilance tasks. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 26(4), 740–749. https://doi.org/10.1109/tnsre.2018.2791936 (2018).

Alavash, M., Doebler, P., Holling, H., Thiel, C. M. & Gießing, C. Is functional integration of resting state brain networks an unspecific biomarker for working memory performance? NeuroImage 108, 182–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.12.046 (2015).

Syriopoulos, P. K., Kalampalikis, N. G., Kotsiantis, S. B. & Vrahatis, M. N. kNN classification: A review. Ann. Math. Artif. Intell. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10472-023-09882-x (2023).

Chen, K. et al. An improved multi-source domain adaptation network for inter-subject mental fatigue detection based on DANN. Biomed. Eng.-Biomed. Tech. 68(3), 317–327. https://doi.org/10.1515/bmt-2022-0354 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. Attention-based multi-semantic dynamical graph convolutional network for eeg-based fatigue detection. Front. NeuroSci. 17 https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1275065 (2023).

Gao, D. et al. CSF-GTNet: A novel multi-dimensional feature fusion network based on convnext-GeLU- BiLSTM for EEG-signals-enabled fatigue driving detection. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 28(5), 2558–2568. https://doi.org/10.1109/JBHI.2023.3240891 (2024).

Chen, K., Chai, S., Xie, T., Liu, Q. & Ma, L. EEG spatial inter-channel connectivity analysis: A GCN-based dual stream approach to distinguish mental fatigue status. Artif. Intell. Med. 157, 102996. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2024.102996 (2024).

Hidalgo Rogel, J. M., Martínez Beltrán, E. T., Quiles Pérez, M., López Bernal, S. & Martínez Pérez, G. Huertas Celdrán A. studying drowsiness detection performance while driving through scalable machine learning models using Electroencephalography. Cogn. Comput. 16(3), 1253–1267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12559-023-10233-5 (2024).

Chen, K., Liu, Z., Liu, Q., Ai, Q. & Ma, L. EEG-based mental fatigue detection using linear prediction cepstral coefficients and Riemann spatial covariance matrix. J. Neural Eng. 19(6), 066021. https://doi.org/10.1088/1741-2552/aca1e2 (2022).

Li, Y., Wang, D. & Liu, F. The auto-correlation function aided sparse support matrix machine for EEG-Based fatigue detection. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 70 (2), 836–840. https://doi.org/10.1109/tcsii.2022.3211931 (2023).

Li, G. et al. Driver vigilance detection based on limited EEG signals. IEEE Sens. J. 23 (12), 13387–13398. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSEN.2023.3273556 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Guo, H., Zhou, Y., Xu, C. & Liao, Y. Recognising drivers’ mental fatigue based on EEG multi-dimensional feature selection and fusion. Biomed. Sign. Process. Control 79, 104237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bspc.2022.104237 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Hanying Guo: Model building, Writing original draft. Siying Chen: Writing original draft, Curation. Yongjiang Zhou: Models building, Writing original draft. Ting Xu: Curation, Supervision. Yuhao Zhang: Collecting data. Hongliang Ding: Calibrate. Thanks to all authors for their contributions to this article.

Funding

This work was supported by Sichuan Natural Science Foundation [grant number 2023NSFSC0386, 2022NSFSC0418].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G. Model building, Writing original draft.C. Writing original draft, Curation. Z. models building, Writing original draft.X. Curation, Supervision.Z. Collecting data.D. Calibrate.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, H., Chen, S., Zhou, Y. et al. A hybrid critical channels and optimal feature subset selection framework for EEG fatigue recognition. Sci Rep 15, 2139 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86234-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86234-1

This article is cited by

-

An improved feature extraction algorithm for EEG-based driving fatigue recognition

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

A novel similarity-constrained feature selection method for epilepsy detection via EEG signals

Journal of King Saud University Computer and Information Sciences (2025)