Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 is a viral infection, best studied in the context of epithelial cell infection. Epithelial cells, when infected with SARS-CoV-2 express the viral S-protein, which causes host cells to fuse together into large multi-nucleated cells known as syncytia. Because SARS-CoV-2 infections also frequently present with cardiovascular phenotypes, we sought to understand if S-protein expression would also result in syncytia formation in endothelial cells. S-protein expression in endothelial cells was sufficient to induce the formation of multi-nucleated cells, with an average of 10% of all cells forming syncytia with an average of 6 nuclei per syncytia after 72 h of S-protein expression. Formation of syncytia was associated with the formation of gaps between cells, suggesting the potential for syncytia formation to compromise barrier function. Inhibition of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), but not Rho-associated protein kinase, inhibited the formation of syncytia, suggesting a role for MLCK in syncytia formation. Further supporting the role of cellular contractility in syncytia formation, we also observed a reduction in the occurrence of syncytia for endothelial cells grown on substrates with reduced stiffness. Because endothelial cells are exposed to physiological forces due to blood flow, we examined the effects of cyclic biaxial stretch and fluid shear stress. While biaxial stretch did not affect syncytia formation, endothelial cells exposed to fluid shear stress were more resistant to syncytia formation. Finally, we observed that endothelial cells are suitable host cells for SARS-CoV-2 viral infection and replication, and that viral infection also causes syncytia formation. Our studies indicate that endothelial cells, in addition to epithelial cells, should also be considered a target for SARS-CoV-2 infection and a driver of COVID-19-associated pathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

COVID-19 infection results in a spectrum of symptoms from mild fevers to severe pneumonia, which are mainly due to the virus infecting the lung epithelia. As epithelia and endothelia form vital barriers for the development and maintenance of the lung, excessive damage of these barriers results in loss of lung function ranging from severe coughs and can progress to acute respiratory distress syndrome1. Furthermore, in autopsy lung tissue samples of severe SARS-CoV-2 patients2, multinucleated cells, syncytia, were reported as a significant finding. This indicates that syncytia formation may be a pathological feature of SARS-CoV-2 virology. However, the potential impact on viral dissemination, pathology, and immune response of SARS-CoV-2 induced syncytia formation has yet to be determined.

SARS-CoV-2 cellular entry is by binding the Spike Glycoprotein (S-protein) on the virus to the host cell receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). The S-protein is a class I viral fusogen protein, consisting of two functional subunits S1 and S2, where S1 contains a receptor-binding domain for viral attachment and the S2 subunit contains a protease cleavage site responsible for membrane fusion of the host cell3. As the virus attaches to the cell, it undergoes conformational changes to deposit the viral genomic RNA into the cellular cytoplasm to begin its viral life cycle. In the process of synthesizing viral proteins, newly made S-proteins can accumulate on the cell surface, where they can interact with nearby (unaffected/naïve) cells4, initiating the fusion process, creating giant multinucleated cells. In addition, Theuerkauf, et al.5, showed that syncytia formation can still occur even with low, undetectable levels of S-protein.

Syncytia formation has also been observed in cell cultures and tissues infected with SARS-CoV-26, with a primary focus on epithelial cell models. Although SARS-CoV-2 mainly affect epithelial cells, there has been evidence supporting that vascular dysfunction is associated with this disease, including the endothelia7. The endothelium has many functional properties such as maintaining tissue homeostasis, vascular permeability, and structural and functional integrity8. When infected by SARS-CoV-2, it has been shown to induce massive damage in the endothelium from inducing apoptosis, altering cellular junctions, and thrombotic events9. Recent work has seen the presence of viral elements inside endothelial cells10 and within the pulmonary microvasculature with congestion and micro-thrombi in lungs of patients2. Furthermore, endothelial cells also express SARS-CoV-2 entry receptors, ACE2, and transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2), suggesting that it may be possible for viral infection of these cells.

Vascular dysfunction has largely been attributed to increased inflammation that results from endothelial infection and the associated innate immune activity. Initially infection of endothelial cells by SARS-CoV-2 was not considered to be a major contribution to viral infection11, but there has been a growing number of studies emerging supporting the hypothesis that there are direct viral-endothelial interactions, including infection of endothelial cells12. Patients with COVID-19 are at significant risk of thromboembolic complications13. This increased risk is thought to be due to several factors, including hypercoagulability associated with the virus, endothelial dysfunction, and inflammation14. Endothelial dysfunction can compromise the endothelial barrier, leading to heightened vascular permeability, which further exacerbates the risk of thrombus formation and edema15. The increase in endothelial permeability can damage blood-air, blood–brain- glomerular filtration, and intestinal-blood barriers16.

To further investigate the role of SARS-CoV-2 in endothelial cells, we investigated if endothelial cells were susceptible to S-protein induced syncytia formation. Using primary endothelial cells (HUVEC) as an in vitro model for the endothelium, we demonstrated that expression of S-protein was sufficient to induce the formation of multinucleated syncytia, with an average of 6 nuclei per syncytia after 72 h of infection. We noted that syncytia had disrupted cell–cell adhesions, suggesting that the formation and growth of syncytia may compromise endothelial barrier function. Additionally, the development of syncytia was dependent on actomyosin contractility, in particular myosin light chain kinase activity, reducing the occurrence and size of syncytia. Notably, we observed that endothelial cells exposed to arterial levels of shear stress do not form syncytia, suggesting that syncytia formation would be most frequent in environments with low shear stress, such as the microvasculature. Lastly, we demonstrate that the SARS-CoV-2 virus can infect and fully replicate in endothelial cells. Taken together our findings demonstrate that endothelial cells can be a target of SARS-CoV-2, and that syncytia formation is an important aspect of SARS-CoV-2 pathophysiology in the endothelium.

Results

Expression of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein induces syncytia formation in endothelial cells

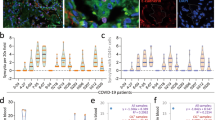

To determine if epithelial cells are susceptible to Spike protein-induced syncytia formation, we used an adenovirus to express the SARS-CoV-2 D614G Spike protein variant in HUVEC. Expression of S-protein resulted in the formation of large, multi-nucleated cells. Cells expressing 3 or more nuclei were identified as syncytia. The frequency of syncytia (percentage of syncytia per total number of cells) and the size of the syncytia (measured as nuclei per syncytia) both increased with time (Fig. 1A and Sup. Figure 1), occurring around 11% of all cells (Fig. 1B) and reaching an average size of 6 nuclei/syncytia (Fig. 1C) at 72 h. We observed that at longer timepoints, larger syncytia sometimes detached from the surface leaving large gaps in the monolayer (Fig. 1A and Video 1), and therefore chose 48 h as our ending time point for further experiments. Western blotting of S-protein (Fig. 1D) was performed to confirm S-protein expression. To control for the effects of adenoviral infection, we used a control adenovirus which expressed eGFP. Expression of GFP by adenovirus does not result in syncytia formation in endothelial cells (Sup. Figure 2), indicating that the formation of syncytia is specific to S-protein expression and not an effect of adenoviral infection. As an additional assessment of changes in cell–cell adhesion, we immunostained cells for VE-cadherin, the major adherens junction protein in endothelial cells. Larger syncytia exhibited loss of VE-cadherin at cell–cell adhesions (Fig. 1E).

Spike protein expression in endothelial cells results in the formation of syncytia. (A) Spike protein was expressed in HUVEC using S-protein expressing adenovirus. Confocal images taken at 20X with Ref scale bar, 100 μm. HUVECs stained with phalloidin to label actin and Hoechst to label nuclei. (B & C) Quantification of syncytia formation in S-protein expressing HUVEC. (B) Syncytia formation increased with time, with an average of 13% of syncytia formation after 72 h. Represent means ± standard deviation from three biological replicates. Significance was determined using a one-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni’s multiple testing correction (n = 3). P values are displayed as ns and ****p < 0.0001. (C) Average size of syncytia increased at 72 h. Represent means ± standard deviation from three biological replicates. Significance was determined using a one-way non-parametric ANOVA with Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn’s multiple comparison test (n = 3). P values are displayed as ns and **p < 0.01. (D) Western blot for protein expression of intact S-protein and GAPDH. (E) Cells exposed to S-protein long term (96 h) creates larger syncytia leaving large gaps in the monolayer and less defined VE-Cadherin (yellow arrows).

Syncytia formation requires myosin light kinase chain kinase activity. (A) Immunostaining treated groups shows syncytia formation (indicated by arrows). Confocal images taken at 20x, scale bar 100 μm. (B & C) Quantification of syncytia formation in S-protein expressing HUVEC. Ordinary one-way ANOVA compared DMSO vehicle control to treated groups. Syncytia formation was decreased significantly in ML7 treated group compared to Y-27632. Represent means ± standard deviation from three biological replicates. Significance was determined using a one-way non-parametric ANOVA with Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn’s multiple comparison test (n = 3). P values are displayed as ns, **p < 0.01, and ****p < 0.0001.

Inhibiting myosin light chain kinase inhibits S-protein driven syncytium formation

We hypothesized that there might be a biomechanical component for myosin contractility in driving S-protein mediated cell–cell fusion. To investigate the role of myosin, we examined the effects of two myosin inhibitors: Y-27632 which inhibits Rho Kinase (ROCK), and ML-7 which inhibits myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) (Fig. 2A). Both the incidence of syncytia (Fig. 2B) and size of syncytia (Fig. 2C) were significantly inhibited with ML-7 but not Y-27632 (Fig. 2A). Thus, it appears that myosin activation, through MLCK, is necessary for syncytia formation. This suggests that myosin activation may be an important step in the formation of syncytia.

Increased extracellular matrix stiffness increases S-protein-induced syncytia formation

To examine if syncytia formation was influenced by ECM stiffness, we examined syncytia formation of endothelial cells grown on 2 kPA and 64 kPa PDMS substrates (Fig. 3A). While we saw no significant differences in the average size of nuclei in a syncytia between the two stiffnesses (Fig. 3C), we observed a significant increase in the occurrence of syncytia at 64 kPa (Fig. 3B). Additionally, when comparing results on these PDMS substrates to results for cells cultured on glass (Fig. 1), we note that the frequency of syncytia and syncytia size was lower on both PDMS substrates as compared to glass substrates. These data suggest that syncytia formation is enhanced in environments with stiffer ECM.

Syncytia formation is regulated by substrate stiffness. Endothelial cells were grown on Cytosoft Imaging Stiffness plates of 2 kPa and 64 kPa for 48 h. (A) Cells were infected with the S-protein, then fixed and stained with phalloidin to label actin and Hoechst to label nuclei. Confocal images taken at 20x, scale bar 100 μm. (B & C) Frequency of a syncytia occurring is increased at 64 kPA, but the size does not differ between the two stiffnesses. Represent means ± standard deviation from three biological replicates. Significance was determined using non-parametric 2-tailed t-test with Mann–Whitney test (n = 3). P values are displayed as ns and ***p < 0.0002.

Endothelial cells adapted to fluid shear stress have reduced syncytia formation

In vivo endothelial cells are continually exposed to two major forces: fluid shear stress, the frictional drag of blood flow exerted on vessel walls and cyclic stretch due to the pulsatility of blood flow17. The mechanoadaptation of endothelial cells to shear stress or cyclic stretch includes dramatic changes in cell morphology, and thus we wondered if cells adapted to either force would be more or less prone to syncytia formation. Interestingly, endothelial cells exposed to arterial levels of fluid shear stress, 12 dynes/cm2 formed significantly less syncytia than cells grown in static culture (no shear stress) (Fig. 4A–C). This lack of syncytia formation was not due to reduced S-protein expression, as cells exposed to fluid shear stress at 12 dynes/cm2 can uptake an adenovirus under flow (Sup. Figure 3) and expression of S-protein under these conditions were similar (Fig. 4D). Endothelial cells exposed to lower levels of shear stress, 2 or 6 dynes/cm2 (Fig. 4B,C), had higher levels of syncytia formation, however, this was still at reduced levels as compared to cells grown in static culture. Collectively, these data show that there is an inverse relationship between exposure to shear stress and syncytia formation. To examine the effects of cyclic stretch, using the FlexCell, we imposed a 5% cyclic stretch at 0.25 Hz for 24 h after 24 h of S-protein infection (Fig. 4E–G). Unlike shear stress, we observed that cyclic stretch did not affect the frequency or size of syncytia formation.

Endothelial cells exposed to physiological shear stress have reduced syncytia formation. (A) Cells were infected with the S-protein under identified flow conditions for 48 h, then fixed and stain with Hoescht and actin. Confocal images taken at 20x, scale bar 100 μm. (B & C) Quantification of the frequency of a syncytia under flow conditions and size of syncytia. Represent means ± standard deviation from three biological replicates. Significance was determined using a one-way non-parametric ANOVA with Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn’s multiple comparison test (n = 3). P values are displayed as ns, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.0002, and ****p < 0.0001. (D) Intact S-protein expression was not affected by shear stress conditions. (E) S-protein infected HUVECs were seeded onto BioFlex amino plates coated with fibronectin exposed to cyclic stretch for 48 h. (F & G) Quantification of the frequency of a syncytia under stretch and size of syncytia did not differ. Represent means ± standard deviation from three biological replicates. Significance was determined using non-parametric 2-tailed t-test with Mann–Whitney test (n = 3). P values are displayed as ns.

SARS-CoV-2 virus is able to infect endothelial cells, promote syncytia formation, and undergo viral replication

To further understand the physiological relevance of our studies in which we express S-protein in endothelial cells, we conducted studies with the SARS-CoV-2 virus. HUVEC were successfully infected with either Omicron (Lineage B.1.1.529) or Italian (Isolate Italy-INMI1) SARS-CoV-2 virus at a MOI of 0.1 for 48 h (Fig. 5A). Syncytia were observed in cells infected with the Italian strain. Additionally, successful viral replication was observed for both strains (Fig. 5B). The titers observed for both strains in endothelial cells are similar to the titer levels observed for SARS-CoV-2 replication in epithelial cell lines18.

Infection of endothelial cells with SARS-CoV-2 virus results in syncytia formation and viral replication. HUVEC cells were infected with either the SARS-CoV-2 Delta (Italian) variant or the Omicron variant at an MOI of 0.1. (A) Cells were fixed and stained with Hoechst and phalloidin at 48 h post infection and imaged using an Echo Revolve fluorescent microscope. (B) Lysates from infected HUVEC were collected at 48 h post infection and analyzed by plaque assay to quantify virus titer. Data represents n = 3 for each condition.

Discussion

Endothelial activation and inflammation are major mechanisms driving the development of severe COVID-19 and even long-COVID symptoms19. Despite this, there has been some uncertainty regarding the susceptibility of endothelial cells to SARS-CoV-2 infection. While some studies have questioned the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to infect or replicate in endothelial cells20, endothelial cells do express SARS-CoV-2 entry receptors. Other groups have shown that SARS-CoV-2 can infect endothelial cells21. SARS-CoV-2 infection of endothelium can potentially lead to profound alterations in the endothelial cell phenotype, triggering endothelial dysfunction leasing to impaired vascular activity and multi-organ injury21. Our work adds to this existing literature, by showing that endothelial cells are both able to be infected by and support SARS-CoV-2 replication (Fig. 5). Additionally, we show that endothelial cells are susceptible to S-protein driven syncytia formation (Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4). These data suggest that in addition to epithelial cells, the endothelial cells are also vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of COVID-19. Infection of endothelial cells by SARS-CoV-2 is not surprising, given that the main mediator of viral entry of SARS-CoV-2 is through viral S-protein interactions with the ACE-2 receptor and TRMPSS212 and both are membrane receptors are present on the surface of endothelial cells. Using HUVECs, we were able to show that viral reproduction does occur in levels similar to epithelial cells18.

Syncytia formation may be a key phenomenon for viral spread to neighboring cells and enhanced viral replication capacity. Additionally, we hypothesize that the formation and growth of syncytia may directly contribute to vascular pathologies, such as loss of barrier, which may be especially important in the lung. We noted that larger syncytia had noticeable gaps at the cell–cell adhesion, suggesting compromised barrier function (Fig. 1). Additionally, time-lapse imaging showed that larger syncytia can detach from the surface, further compromising barrier function and leaving a large gap in the cell monolayer (Supplemental Figure 1 and Video 1). Exposure of the sub-endothelial ECM can also serve as a site for thrombosis, and we note that increased risk of thrombosis is present in COVID-19 patients14. The mechanisms which govern syncytia detachment from the substrate are not clear. We did not observe any increases in apoptotic markers in syncytia (data not shown) suggesting that syncytia detachment is not the result of apoptosis.

COVID-19 can weaken the integrity of the endothelial barrier, leading to increased vascular leakage and the spread of the virus22. This barrier includes intercellular junctions, such as tight junctions and adherens junctions. Tight junctions are formed by junction adhesion molecules (JAMs), claudins, and occludin, along with proteins known as zonula occludens (ZO) that help connect them to the actin cytoskeleton. On the other hand, adherens junctions contain a protein called vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin), which mediates cell–cell contact through its extracellular domain16. COVID-19 patients have shown to have decreased levels of claudins, occudin, and VE-cadherin, increasing endothelial permeability16. In Fig. 1E, we observed that cells exposed to the S-protein for 96 h formed larger syncytia, resulting in bigger gaps and less defined VE-cadherin staining. Similarly, Nader et al.23 reported a decrease in VE-Cadherin surface expression when cells were exposed to the Human 2019-nCoV strain 2019-nCoV/Italy-INMI1.

The mechanisms that govern cell–cell fusion in the context of SARS-CoV-2 include ACE2/S-protein interaction. As the virus infects the cell, it alters the morphology, and the main change is to the host cytoskeleton network24. In this manuscript we provide additional mechanistic insight into the formation of syncytia, by showing the importance of myosin contractility in S-protein driven cell–cell fusion. Pharmacological inhibition of MLCK, but not ROCK, resulted in a significant decrease in the occurrence and size of syncytia (Fig. 2). Additionally, we demonstrate that increased ECM stiffness (from 2 to 64 kPa), similar to the lung and bone ECM25, significantly increases the occurrence of syncytia (Fig. 3). Additionally, there was a nearly tenfold greater incidence of syncytia formation for cells grown on glass (Fig. 1) to cells grown on softer polyacrylamide gels (Fig. 4E) further demonstrating that substrate stiffness, and by extension increases in cellular contractility, is positively correlated to the formation of syncytia. Increases in stiffness have been hypothesized by others to be important in severe COVID-1926.

The formation, remodeling, and stabilization of cell − cell adhesions in endothelial cells are mediated by actomyosin structures27. As actomyosin is inherently contractile and a conserved mechanism, we sought to disrupt this process via pharmacological inhibitors of MLCK and ROCK pathways to illustrate the role of contractility on syncytia formation. Our result with these inhibitors suggests that the MLCK pathway downregulates the formation of syncytia while ROCK is negligible. These results support work done by Kazakova et al., that ROCK contributes less to endothelial hyperpermeability than MLCK, which is critical for endothelial cell barrier dysfunction28. With a less permissible membrane via ML-7, this promotes a stronger barrier integrity to withstand the fusogenic capability of the S-protein.

An additional finding of our work is that endothelial cells adapted to arterial levels of fluid shear stress are more resistant to Spike protein-induced syncytia formation (Fig. 4A–D). Shear stress is inversely proportional to the third power of the vessel radius, it is estimated that mean shear stress is lowest in the large veins, where it is often < 1 dyne/cm2 and at least 20-fold higher in small arterioles and venules29,30. This suggest that endothelial cells located in areas of arterial levels of shear stress are less likely to form syncytia upon SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to venous levels of shear stress30. Furthermore, shear stress is linked to the development of endothelial phenotypic changes related to atherosclerosis. This is particularly influenced by factors such as flow separation and disturbances caused by low average shear stress, changes in flow gradients, oscillatory flow, and complex multifrequency multidirectional secondary flows31. Over time, these processes work together to facilitate plaque formation and instability, heightening cardiovascular risk. Moreover, patients with COVID-19 have been shown to be at an increased risk of cardiovascular complication, with evidence of SARS-CoV-2 replication found in all human autopsy coronaries32. Notably, several studies have identified microvascular complications as a potential complication of COVID-1933. However, it remains unclear whether the inhibitory effects of fluid shear stress on syncytia formation are related to the physical re-alignment of endothelial cells, such as changes in actin organization, that may prevent cell–cell fusion. In contrast to shear stress, we did not observe any effects of biaxial cyclic stretch on syncytia formation (Fig. 4E–G).

In summary our work demonstrates that endothelial cells are susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, including cell–cell fusion to form large multinucleated cells, known as syncytia. Endothelial cell syncytia formation can be influenced by actomyosin contractility, ECM stiffness, and adaptation to fluid shear stress. This work provides additional evidence for the potential role of endothelial cells in COVID-19 infections.

Methods

Cell culture and transfection

Commercially available primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs; pooled, passages 2–5; Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) grown in EGM-2 medium (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) was used for all experiments. Cells were seeded on 35 mm glass bottom dishes with 20 mm micro-well (#D35-20.1.5-N, Celvis) coated with 20 µg/mL fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich; F1141). To express SARS-CoV-2 Spike D614G Protein, an adenovirus (Lot #20211130 T#4) with a PFU titer of 6.0 × 1010 PFU/mL, was purchased from Vector Biolabs and used in a concentration that infected nearly 100% of cells were infected, 10–30 MOI.

Cells were treated with 10 μM Y-27632 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) or 10 μM ML-7 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) 24 h prior to adenovirus.

Stiffness plates

CytoSoft-Imaging 24-well plates with a layer of silicon with stiffness of 2 kPa and 64 kPa were purchased from Advanced BioMatrix (#5185 & #5189; Carlsbad, CA). The surface was pre-coated with 40 µg/mL according to manufacture’s instructions.

Fluid shear stress

Cells were seeded onto ibidi chamber slides (ibidi-treated µ-slides I0.4 or 0.6, #80,186 or ibidi-treated µ-slides VI0.4, #80,606), coated with 60 µg/ml fibronectin. At 80% confluency, HUVECs were exposed to laminar various 2, 6, or 12 dynes/cm2 levels of shear stress using the ibidi pump system (#10,902, iBidi) with or without the S-protein (as indicated in figure legends) perfused in the media for 48 h.

Biaxial stretch

Amino-coated BioFlex plates (FlexCell; Lot# 211,122) were coated using 40 µg of fibronectin in 0.15 M NaCl at room temperature for 45 min. The fibronectin NaCl solution was taken off the plate and let dry for about 5 min before adding 2 mL of regular media or the adenovirus. The plate was then placed in the incubator for about 30 min to warm the media before seeding the cell. Each well was seeded with 500,000 cells, after 24 h after seeding all media was changed to regular media and then were stretched for 24 h. The parameters used for stretch were, shape was sine, elongation from 0 to 5%, frequency of 0.25 (15 breaths per minute), and DC % was 50. After 24 h of stretching samples were fixed and stained immediately after.

Cell fixation and labeling

Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed for 10 min at room temperature with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. After, the cells were permeabilized for 10 min at room temperature with 0.2% or 1X Triton X solution in PBS and blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin. Cells were then incubated overnight at 4 °C room temperature with the primary Ab diluted in blocking solution. The following primary antibodies were used: VE-cadherin (Cell Signaling Technology; D87F2; 1:400). Then incubation with the secondary Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (#A-31573, Thermo Fisher) and stained with rhodamine phalloidin (#PHDR1, Cytoskeleton) and stained with Hoechst 33,342 (Thermo Fisher).

Western blot

Cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (#BP-115, Boston BioProducts) supplemented with protease and phosphate inhibitor (#A32959, Thermo Scientific), following manufacture’s instructions for ibidi u-Slides. Samples were separated using a 4–20% precast gels (#4,561,094, Bio-Rad) and transferred to a PVDF membrane. Blots were incubated with anti-S1 antibody (40,591-T62,Sino Biological; 1:1000), and anti-GAPDH as a loading control (#G8795, Sigma Aldrich; 1:1000) overnight. Secondary antibodies used were anti-rabbit IgG (#7074, Cell Signaling; 1:5000) and anti-mouse IgG (#7076, Cell Signaling; 1:5000). Blots were imaged using Pierce SuperSignal West Pico Plus (#34,577, Thermo Scientific) and exposed on an Azure 300 imager.

Microscopy and image analysis

Fixed samples were imaged on a Zeiss LSM 710 or Leica Stellaris 8 confocal microscope at 20 × . Image analysis was completed using Fiji ImageJ. We analyzed syncytium forming cells by quantifying the abnormal phenotype of multi-nucleated cell (3 + nucli) in the frame.

SARS-CoV-2 viral infection experiments

SARS-CoV-2 variants Isolate Italy-INMI1 (NR-52284) and Lineage B.1.1.529; Omicron Variant (NR-56461) were obtained from BEI Resources. HUVEC were infected with either variant at an MOI of 0.1. Cells were fixed and stained with Hoechst and phalloidin at 48 h post infection and imaged using an Echo Revolve fluorescent microscope. Lysates from infected HUVEC were collected at 48 h post infection an analyzed by plaque assay.

Plaque assay protocol: Vero E6 cells were seeded into 12 well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells per well and grown to a confluency of 80%. Eight ten-fold serial dilutions of Supernatants collected from SARS-CoV-2 infected HUVEC cells were used to infect each well of the 12-well plate. Plates were incubated for 1 h (rocking every 15 min) at 37 °C followed by an overlay with a 1:1 ratio of 1.0% agarose and Eagle’s Modified Essential Medium (without phenol red) supplemented with 5% FBS, 1% penicillin and streptomycin, 1% L-glutamine, 1% NEAA, and 1% sodium pyruvate. After 48 h, plates were fixed with 10% formaldehyde for 1 h. Plugs were removed and plates were stained with 1% crystal violet, 20% ethanol, and 79% diH2O. Plaque-forming units are represented as PFU/mL. For samples that were infected with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron the cells used for the plaque assay were Vero E6 cells that over express ACE2 and TMPRSS2 (VeroE6-ACE2/TMPRSS2).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 10 and are described in the figure legends. Normality was determined with Shapiro–Wilk test for parametric one-way ANOVA analysis with Bonferroni post-test. If not normal, non-parametric one-way ANOVA analysis with Kruskal–Wallis and Dunn’s post-test or non-parametric two-tailed Student’s t-test with Mann–Whitney was were done. Error bars represents represent means ± standard deviation. All statistical tests were conducted at a minimum 5% significance level (p< 0.05). Every experiment was completed three times, and a minimum of 10 field of view from each group were analyzed.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Upadhya, S., Rehman, J., Malik, A. B. & Chen, S. Mechanisms of lung injury induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Physiology 37, 88–88. https://doi.org/10.1152/PHYSIOL.00033.2021 (2022).

Ackermann, M. et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 120–120. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMOA2015432 (2020).

Chan, C. W. F. et al. High-throughput screening of genetic and cellular drivers of syncytium formation induced by the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41551-023-01140-z (2023).

Rajah, M. M., Bernier, A., Buchrieser, J. & Schwartz, O. The mechanism and consequences of SARS-CoV-2 spike-mediated fusion and syncytia formation. J. Mol. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JMB.2021.167280 (2021).

Theuerkauf, S. A. et al. Quantitative assays reveal cell fusion at minimal levels of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and fusion from without. iScience 24, 102170. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ISCI.2021.102170 (2021).

Chaudhary, S., Yadav, R. P., Kumar, S. & Yadav, S. C. Ultrastructural study confirms the formation of single and heterotypic syncytial cells in bronchoalveolar fluids of COVID-19 patients. Virol. J. 20, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12985-023-02062-7/FIGURES/4 (2023).

Tarnawski, A. S. & Ahluwalia, A. Endothelial cells and blood vessels are major targets for COVID-19-induced tissue injury and spreading to various organs. World J. Gastroenterol. 28, 275–275. https://doi.org/10.3748/WJG.V28.I3.275 (2022).

Xu, S. W., Ilyas, I. & Weng, J. P. Endothelial dysfunction in COVID-19: An overview of evidence, biomarkers, mechanisms and potential therapies. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2022(44), 695–709. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-022-00998-0 (2022).

Six, I. et al. The endothelium and COVID-19: An Increasingly clear link brief title: Endotheliopathy in COVID-19. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 6196. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJMS23116196 (2022).

Varga, Z. et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet (London, England) 395, 1417–1417. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5 (2020).

Schimmel, L. et al. Endothelial cells are not productively infected by SARS-CoV-2. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 10, e1350. https://doi.org/10.1002/CTI2.1350 (2021).

Perico, L., Benigni, A. & Remuzzi, G. SARS-CoV-2 and the spike protein in endotheliopathy. Trends Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TIM.2023.06.004 (2023).

Smeda, M. & Chlopicki, S. Endothelial barrier integrity in COVID-19-dependent hyperinflammation: Does the protective facet of platelet function matter?. Cardiovasc. Res. 116, e118. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvaa190 (2020).

Sutanto, H. & Soegiarto, G. Risk of thrombosis during and after a SARS-CoV-2 infection: Pathogenesis, diagnostic approach, and management. Hematol. Rep. 15, 225–225. https://doi.org/10.3390/HEMATOLREP15020024 (2023).

Michalick, L. et al. Plasma mediators in patients with severe COVID-19 cause lung endothelial barrier failure. Eur. Respiratory J. 57, 2002384. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02384-2020 (2021).

Wu, X. et al. Damage to endothelial barriers and its contribution to long COVID. Angiogenesis https://doi.org/10.1007/s10456-023-09878-5 (2024).

Hahn, C. & Schwartz, M. A. Mechanotransduction in vascular physiology and atherogenesis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10(1), 53–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm2596 (2009).

Jureka, A. S., Silvas, J. A. & Basler, C. F. Propagation, inactivation, and safety testing of SARS-CoV-2. Viruses 12, 622–622. https://doi.org/10.3390/V12060622 (2020).

Lui, K. O., Ma, Z. & Dimmeler, S. SARS-CoV-2 induced vascular endothelial dysfunction: Direct or indirect effects?. Cardiovasc. Res. 120, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/CVR/CVAD191 (2024).

McCracken, I. R. et al. Lack of evidence of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 expression and replicative infection by SARS-CoV-2 in human endothelial cells. Circulation 143, 865–868. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.052824 (2021).

Xu, S.-W. et al. Endothelial dysfunction in COVID-19: An overview of evidence, biomarkers, mechanisms and potential therapies. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 44, 695. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41401-022-00998-0 (2022).

Jin, Y. et al. Endothelial activation and dysfunction in COVID-19: From basic mechanisms to potential therapeutic approaches. Signal Trans. Targeted Therapy 5, 293. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-020-00454-7 (2020).

Nader, D., Fletcher, N., Curley, G. F. & Kerrigan, S. W. SARS-CoV-2 uses major endothelial integrin αvβ3 to cause vascular dysregulation in-vitro during COVID-19. PLOS One https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0253347 (2021).

Xing, Y., Zhang, Q. & Jiu, Y. Coronavirus and the cytoskeleton of virus-infected cells. Subcell. Biochem. 106, 333–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-40086-5_12/TABLES/1 (2023).

Booth, A. J. et al. Acellular normal and fibrotic human lung matrices as a culture system for in vitro investigation. Am. J. Respiratory Critic. Care Med. 186(9), 866–876. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201204-0754OC (2012).

Kerch, G. Severe COVID-19—A review of suggested mechanisms based on the role of extracellular matrix stiffness. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 1187. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJMS24021187 (2023).

Angulo-Urarte, A. et al. Endothelial cell rearrangements during vascular patterning require PI3-kinase-mediated inhibition of actomyosin contractility. Nat. Commun. 9, 4826. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07172-3 (2018).

Kazakova, O. A., Khapchaev, A. Y. & Shirinsky, V. P. MLCK and ROCK mutualism in endothelial barrier dysfunction. Biochimie 168, 83–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BIOCHI.2019.10.010 (2020).

Ballermann, B. J., Dardik, A., Eng, E. & Liu, A. Shear stress and the endothelium. Kidney Int. 54, 100. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.06720.x (1998).

Givens, C. & Ellie, T. Endothelial mechanosignaling: does one sensor fit all?. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 25, 373. https://doi.org/10.1089/ars.2015.6493 (2016).

Davies, P. F. Hemodynamic shear stress and the endothelium in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 6, 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpcardio1397 (2009).

Eberhardt, N. et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection triggers pro-atherogenic inflammatory responses in human coronary vessels. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2023(2), 899. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44161-023-00336-5 (2023).

Nappi, F. & Singh, S. S. A. Endothelial dysfunction in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Biomedicines 10, 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10030654 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This project was funded in part by National Institute of Health award R35 GM119617 (to D.E.C.) and Virginia Commonwealth Heath Research Board Grant #236-03-21 (to D.E.C and R.L.H.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was initially conceived by KTV and DEC, with significant input also provided from RLH, AN, and FA regarding study design. KTV performed experiments and prepared data for Figs. 1, 2, 3 and 4. ME performed experiments and prepared data in Fig. 4. FA performed experiments and prepared data for Fig. 5. KTV and DEC wrote the main manuscript, and RLH and FA provided additional edits and feedback to the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Video 1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tieu, K.V., Espey, M., Narayanan, A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 S-protein expression drives syncytia formation in endothelial cells. Sci Rep 15, 3549 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86242-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86242-1