Abstract

The increasing trend of salinization of agricultural lands represents a great threat to the growth of major crops. Hence, shedding light on the salt-tolerance capabilities of three environment-resilient medicinal species from the Apiaceae, i.e. fennel, ajwain, and anise as alternative crops was aimed at. Two genotypes from each of the three medicinal species were exposed to a wide range of water salinities, including 0 (control), 40, 80, and 120 mM NaCl and comparative changes in the leaf photosynthetic pigments, osmoticums, antioxidative enzymes, ionic homeostasis, essential oil, and plant growth were assessed. Even though certain genotype- and species-specificities were observed in the salt-induced modifications of these physiological attributes, decreasing in growth, plant dry mass, root volume, relative water content, and K+ concentration concomitant to increasing in the catalase, ascorbate peroxidase, and guaiacol peroxidase activities, malondialdehyde, total soluble carbohydrates, proline and Na+ concentrations, Na+/K+, and essential oil were common to the examined species and genotypes. The K+ concentration of the stressed plants of anise genotypes was smaller, giving shape to a greater Na+/K+ than those of fennel and ajwain. Unlike anise, fennel and ajwain genotypes retained and/or increased the chlorophyll and carotenoids concentrations when exposed to 120 mM NaCl. The greater salt-induced increases in the catalase, ascorbate peroxidase, and guaiacol peroxidase activities along with the less-heightened Na+/K+ were concomitant to the smaller depressions in the total plant dry mass and root volume of the fennel and ajwain genotypes, portraying these species more resilient to saline water, compared to anise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Production of crop plants, including the medicinal species, in arid-semiarid regions of the world is challenged by high soil and water salinities. Stress-induced decreases in plant growth and above-ground dry mass have been established for different medicinal plant species1. Excess soluble salts in soil are harmful to most plant species as they impose osmotic, ionic, and secondary stresses (e.g., oxidative stress) to the plants2,3. The osmotic, ionic, and oxidative stresses, altogether, may suppress photosynthetic functions and hence the plant shoot and root growth and dry mass4. Due to the chemical similarities between Na+ and K+, Na+ may act as a competitor to K+ during the uptake process, leading to perturbation of cellular Na+/K+homeostasis in plants exposed to saline environments5. Oxidative damage is one of the aftermaths of salinity; in effect, in order to withstand salinity, the reactive oxygen species (ROS) concentration in plant cells must be tightly regulated. Therefore, a sustained ion homeostasis suits best for plant salt tolerance when it is co-occurred with an effective antioxidative defense2. Even though response to saline conditions may vary with plant species, some responses are shared not only among different genotypes of a same species but they are more or less present also in different species. Osmolytes accumulation is a common response to various abiotic stresses exhibited by different types of plants, from herbaceous annuals6,7to tree species8,9and is often taken as an osmo-protective mechanism10. Indeed, a balance between proline synthesis, degradation, and transport, along with an effective means of scavenging stress-induced ROS, are all necessary for the maintenance of growth and development under different environmental conditions. Even though enzymatic and non-enzymatic defenses are constitutively expressed, the extent of the defensive response may vary with plant species and genotype examined, and duration, nature, and intensity of the stress. A lacuna of comparative studies on biochemical and physiological behaviors of medicinal species in saline environments is evident. Anise (Pimpinella anisum) is a medicinal plant in the Apiaceae family. Its fruits (i.e., aniseed) contain 1–4% of essential oil, anethole being the major component (75–90%) of the essential oil11. Fennel (Foeniculum vulgareMill.) is another aromatic plant from the Apiaceae family, whose mature edible seeds are used for different purposes, including in folk medicine, pharmaceutical and cosmetic products, and production of food preserving compounds in food industries12,13. Ajwain (Trachyspermum ammi L.) also belongs to the Apiaceae and accumulates an essential oil containing about 50% thymol14. The growth, physiological functions, and essential oils content of medicinal plants may vary with genotype and the environmental conditions13,15, particularly salinity14. This investigation was undertaken with the goal of assessing key physiological traits that may affect differences in the response of a set of three medicinal species from Apiaceae family (i.e. anise, fennel, and ajwain) to saline water. Photosynthetic pigments, osmolytes, antioxidative enzymes, and ionic modifications were chosen to assure a mechanistic examination of the differences in sat-associated growth penalties among genotypes of these species.

Results

Results of statistical analysis

All examined traits, including leaf chlorophyll (Chl) and carotenoids (Cars) concentrations, ascorbate peroxidase (APX), guaiacol peroxidase (POX), and catalase (CAT) activities, malondialdehyde (MDA), proline, total soluble carbohydrates (TSC), shoot Na+ and K+ concentrations, and Na+/K+, relative water content (RWC), plant above-ground dry mass (SDM), plant’s total (shoot + root) dry mass (TDM), seed essential oil concentration, and root volume were significantly affected by species, genotype, and salinity effects and at least one of the species × genotype, species × salinity, genotype × salinity, and species × genotype × salinity interactions (Table 1). Considering the fact that all traits (with the exception of RWC) were affected at least by one of the first order interactions (i.e., species × genotype, species × salinity, and genotype × salinity) or the second order interaction (i.e. species × genotype × salinity interaction), for obeying the statistical rules and the ease of comparisons, hereunder only the means for species × salinity and species × genotype × salinity will be explained and discussed.

Mean comparisons for species × genotype × salinity

Data of the second order interaction (i.e., species × genotype × salinity) indicates that salt-induced modifications in Chl and Cars concentrations of the ajwain, fennel, and anise were genotype-specific (Table 2). While salt-induced changes in Chl concentration of genotype Yazd (fennel) and Isfahan (anise) weren’t notable, those of the two ajwain genotypes and Marvdasht genotype (anise) were suggestive of 31–48% decreases, but that of genotype Shiraz (fennel) indicated 51% increase, compared to those grown under the non-saline conditions. Cars concentration of fennel genotype Shiraz increased by more than 58% but that of Yazd indicated no notable change in the presence of 120 mM NaCl. Ajwain genotype Nahadjan indicated a 100% increase but no significant changes were observed in the salt-stressed Ghahdrijan plants. Anise genotypes Marvdasht and Isfahan indicated 53% increase and 14% decrease, respectively, when treated with 120 mM NaCl.

MDA concentration of the salt-exposed plants of the genotypes of all examined species were increased (Table 2), though the extent of the increases varied among the genotypes, leading to the species × genotype × salinity interaction. For example, the smallest salt-induced increase (i.e. 18%) in MDA concentration was observed in genotype Ghahdrijan (ajwain) and the greatest increases (i.e. 112–118%) belonged to the two anise genotypes. CAT and APX activities of the salt-stricken plants tended to increase in all genotypes of the three examined species, but differences in the magnitude of the increases resulted in the species × genotype × salinity interaction (Table 3). The greatest salt-induced increases in the APX activity (i.e. 159–189%) were detected in genotypes Ghahdrijan and Nahadjan (ajwain). The greatest amounts of CAT activity were found in genotypes Shiraz and Yazd (fennel), irrespective of the NaCl concentration. POX activities of both of the fennel genotypes (i.e., Shiraz and Yazd), Nahadjan (ajwain), and Marvdasht (anise) were increased with increase in NaCl concentration, i.e. the increases varied from 271 to 310% upon exposure to 120 mM NaCl. But POX activity of the genotypes Ghahdrijan (ajwain) and Isfahan (anise) were decreased by 10% and 88%, respectively, when grown in the presence of 120 mM NaCl. The two examined anise genotypes (i.e., Marvdasht and Isfahan) indicated the smallest amounts of POX activity, irrespective of NaCl concentration.

Unlike 5 to 20-fold increases in the Na+ concentration of the salt-stricken plants, K+ concentration decreased by 41–65%, leading to 10 to 40-fold increases in Na+/K+ of different genotypes of the three examined species, compared to the non-stressed plants (data not-shown). The smallest salt-induced increase in Na+ concentration (i.e. nearly 500%) belonged to genotype Nahadjan (ajwain). The smallest K+ concentrations were observed in the anise genotypes, i.e. Marvdasht and Isfahan (Table 3). The smallest (i.e. nearly 10-fold increase) and greatest increases (i.e. nearly 15 to 20-folds) in Na+/K+ of the salt-stressed plants were detected in genotype Nahadjan (ajwain) and the two anise genotypes, i.e. Marvdasht and Isfahan, respectively. Seed essential oil concentrations of the stressed (120 mM NaCl) plants of genotypes Shiraz (fennel) and Ghahdrijan and Nahadjan (ajwain) were more or less 100% greater than those of the non-stressed plants. While seed essential oil of genotype Yazd (fennel) was greater than the other genotypes (i.e. fennel and ajwain genotypes), it did not increase significantly due to 40 and 80 mM NaCl. It must be mentioned that seed essential oil data for the Yazd plants exposed to 120 mM NaCl was not obtained. SDM and TDM of all of the examined genotypes were decreased substantially when exposed to 120 mM NaCl. Though, the extent of the salt-induced decreases in SDM (47–58%) was smaller in the fennel genotypes (i.e. Yazd and Shiraz) and the genotype Ghahdrijan (ajwain), compared to decreases (64–74%) in the genotype Nahadjan (ajwain) and the two anise genotypes (i.e. Isfahan and Marvdasht). Genotypic differences for the salt-induced decreases in the TDM were more or less similar to those observed for SDM, i.e. fennel genotypes (i.e. Yazd and Shiraz) and the genotype Ghahdrijan (ajwain) tended to maintain (at least in part) the TDM in the presence of saline water.

Mean comparisons for species × salinity

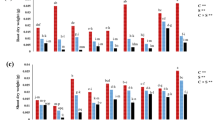

Mean comparisons of species × salinity interaction indicated that unlike anise, where the Cars concentration (Fig. 1a) and POX activity (Fig. 1d) remained unchanged and CAT activity (Fig. 1b) increased only by 35%, fennel and ajwain indicated modest increases in the Cars concentration and 2 to 3-fold increases in the POX and CAT activities under saline conditions. APX activity of the salt-exposed fennel increased by 53% but those of ajwain and anise were increased by 2 to 3-folds, compared to the non-stressed plants (Fig. 1c). The smallest and greatest salt-driven increases in the MDA concentration were observed in the ajwain and anise, respectively (Fig. 2a). Leaf proline concentration of anise tended to be smaller than those of fennel and ajwain (Fig. 2b). TSC concentration of ajwain tended to be smaller than those of fennel and anise (Fig. 2c), but RWC was in the descending order of fennel > ajwain > anise (Fig. 2d). Salt-induced increases in the Na+ concentration were greatest for anise (Fig. 3a), but shoot K+ concentration of ajwain tended to be slightly greater than those of fennel and particularly anise (Fig. 3b), leading to the greatest increases in the Na+/K+ of anise (Fig. 3c) compared to those of fennel and particularly ajwain. Root volume of all of the examined species was decreased with increase in salinity; albeit, the smallest extent of the decrease was found in fennel (Fig. 3d).

Mean comparisons of (a) carotenoids (Cars) concentration and activities of (b) catalase (CAT), (c) ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and (d) guaiacol peroxidase (POX) of fennel, ajwain and anise medicinal species under four concentrations of NaCl (0, 40, 80, and 120 mM) in irrigation water. Each mean is accompanied by an error bar. Means bearing a same letter do not differ significantly according to the least significant difference (LSD) at the 0.05 level of statistical probability.

Mean comparisons of (a) malondialdehyde (MDA), (b) proline, and (c) total soluble carbohydrates (TSC) concentrations and (d) relative water content of fennel, ajwain, and anise medicinal species under four concentrations of NaCl (0, 40, 80, and 120 mM) in irrigation water. Each mean is accompanied by an error bar. Means bearing a same letter do not differ significantly according to the least significant difference (LSD) at the 0.05 level of statistical probability.

Mean comparisons of (a) Na+ and (b) K+ concentrations, (c) Na+/K+, and (d) root volume of fennel, ajwain and anise medicinal species under four concentrations of NaCl (0, 40, 80, and 120 mM) in irrigation water. Each mean is accompanied by an error bar. Means bearing a same letter do not differ significantly according to the least significant difference (LSD) at the 0.05 level of statistical probability.

Discussion

Even though direct measurement of photosynthesis capacity may lead to an accurate measure of plant production capacity, thus far more interest has focused on the more-readily quantifiable photosynthetic pigments, instead of a direct measurement of photosynthetic rate. Chl and Cars are key components of the photosynthetic machinery, as they play key role in harvesting light energy, stabilizing membranes, and transducing energy. Thus, leaf Chl concentration provides an accurate proxy for leaf photosynthethic capacity16. A tendency of the two fennel genotypes to increase and maintain the Chl concentration in the presence of moderate (i.e. 40 and 80 mM NaCl) and high (i.e. 120 mM NaCl) salt concentrations (Table 2), respectively, rendered it different from the ajwain and to some extent anise, whose Chl concentrations were decreased at least in the presence of the 120 mM NaCl. Moreover, anise and ajwain tended to contain smaller amounts of Chl, irrespective of the NaCl concentration, compared to fennel. Such lowered investment in Chl synthesis is thought to limit the photochemical energy production needed to carboxylation17. For instance, a papaya genotype characterized by low Chl concentration was outcompeted by a genotype with high Chl, in terms of growth, shoot and root dry mass. Our finding with salt-stricken anise and ajwain is in line to those of Pandey et al.18 on canola and Shinde et al.19 on groundnut, where they reported drought-induced decreases in Chl concentrations. Our data agrees also, to some extent, with those of Sardar et al.20, where they reported nearly 60% and 40% decreases in Chl and Cars concentrations, respectively, of anise plants that had been exposed to 120 mM NaCl. Even though salinity increased the Chl and Cars content per leaf area, thicker and narrower leaves of stressed wheat plants led to a decreased Chl and Cars content on a per plant basis21. Such scenario may be applicable to the Chl response of the examined fennel genotypes of the present study. The increased Chl concentration of the stressed fennel plants of Shiraz and in a lesser (i.e. statistically non-significant) extent Yazd genotypes may be attributed to a probable increase in chloroplast concentration of photosynthetic cells of the stressed plants22. As it has been argued in the literature16, the suppressed Chl concentration of ajwain and anise may have stemmed from an accelerated Chl degradation and/or a suppressed biosynthesis of this pigment under saline conditions. Leaf proline concentration of fennel was less affected by salt, in comparison to those of anise and ajwain (Fig. 2b); the serious Chl degradation of the salt-exposed plants of anise and ajwain genotypes (Table 2) was concomitant with proportional increases in the proline concentration. The notable salt damage to the Chl of anise and ajwain seems to be in relation to the increased proline synthesis and, hence, accumulation in these species. Glutamine serves as a precursor for both Chl and proline biosynthesis22. Hence, lack of a notable contribution of proline to the stress-response of the stressed plants (exemplified by the salt-stressed fennel genotypes in the present study) may eliminate a redirection of the photoassimilates towards this protective osmolyte, thereby favoring a maintained Chl concentration.

The observed decrease in Cars concentration of genotype Isfahan (anise) in response to salinity contrasted the other anise, ajwain and fennel genotypes, as Cars concentration of the latter genotypes was increased or at least maintained particularly under the moderate concentrations (i.e. 40 and 80 mM) of NaCl. Moreover, the two anise genotypes were outnumbered by the fennel and ajwain genotypes in terms of Cars concentration. Cars are comprised of a primary and a secondary group of molecules23. Primary Cars, mainly accumulating under favorable conditions and residing within the thylakoid membranes, serve in light harvesting, photoprotection, and supporting the structural integrity of the photosynthetic compartments. Secondary Cars, on the other hand, tend to accumulate under stressful conditions, exert antioxidant effects, and contribute to the acclimation of plant to different stresses (including salinity). We did not attempt discriminating the primary and secondary Cars in the examined species, though, the worsened MDA accumulation (i.e. 112–118% increases in the anise genotypes) in the salt-stricken plants of the same genotype confirms the existence of causative relationships between the decreased Cars concentration and the aggravated lipid peroxidation in anise. Reactive oxygen species may elicit carotenogenesis through affecting redox state of electron carriers of the chloroplastic electron transport chain of the stressed plants22. It may, therefore, be argued that the proposed carotenogenesis has enabled the salt-stricken plants of fennel, ajwain, and anise (with the exception of genotype Isfahan) genotypes of the present study to maintain (and in some cases, accumulate) the Cars pigments (Fig. 1a).

With the exception of the genotype Nahadjan (ajwain) which indicated a 98% increase (Table 2), the salt-driven increases in proline concentration were hardly greater than 50% (Fig. 2b). Though, the increases in TSC concentration were nearly 50, 95, and 300% for fennel, ajwain, and anise, respectively (Fig. 2c). Plants respond to osmotic stress at all levels of organization; the basic cellular responses such as osmotic adjustment are conserved among all plants. The osmotic adjustment is recognized as a major mechanism of plant resistance against drought24. Therefore, the commonness of salt-induced increase in either proline or TSC concentrations among the three examined species was not surprising. The descending orders of the examined species (i.e. averaged over the genotypes and NaCl concentrations) in terms of proline and TSC concentrations and RWC (Fig. 2d) were fennel = ajwain > anise, fennel > anise > ajwain, and fennel = ajwain > anise, respectively. The latter orders and, more importantly, the 26–31% decreases in the RWC of the salt-sensitive anise plants (Table 3) indicate that maintaining leaf water status (depicted in RWC) of these species is rather associated to the proline than the TSC concentration. Biosynthesis and amassment of osmolytes such as proline and soluble sugars stem from the upregulation of related genes in the stressed plants7. Moreover, homeostasis, intra- and intercellular transport, metabolism dynamics and, hence, turnover of proline are tightly controlled at the cellular level. It must be understood that compatible solutes such as proline and soluble carbohydrates are multifunctional molecules. It is simplistic to consider proline as a sole osmoticum, as it has the ability to integrate plant development with environmental cues25. Thus, the accumulated proline acts most probably as both an osmoticum and a ROS scavenger. Moreover, in addition to being compatible solutes, soluble carbohydrates are also known as primary products of photosynthetic metabolism and signaling and regulatory molecules9. A direct relationship between stress-dependent increase in the concentration of a particular osmolyte and acquirement of stress tolerance is not fully established9. Though, it is believed that proline accumulated during a stress episode is degraded to provide a supply of energy to drive growth once the stress is relieved. Despite a commonly hold view that proline accumulation brings about stress-tolerance19, an increasing number of literature18 are indicative of a weak relationship between proline accumulation and stress-tolerance. Hence, despite the notable difference among the species and genotypes in terms of salt tolerance (i.e. reflected in SDM, TDM, and root volume alterations), no substantial differences in the proline concentration of different species and genotypes therein were observed.

The type of compatible osmolytes synthesized in salt-stressed plants may be species- and genotype-specific3. In addition to compatible solutes such as proline, sugars (i.e., sucrose and fructose), and complex sugars (i.e. trehalose, raffinose, and fructans), inorganic ions such as K+ and Na+ may contribute much to the osmotic adjustment in many species. From the greater concentrations of K+ found in the genotypes Nahadjan (ajwain) and Shiraz (fennel) (Table 3), Na+ in the genotype Yazd (fennel), and TSC and to a certain degree proline in the two fennel genotypes, it may be inferred that fennel and ajwain have relied on different osmoticums to maintain the plant water status, depicted in a somewhat sustained RWC (Table 3; Fig. 2d). It may be further inferred that lack of such osmoregulatory measures in anise has contributed to its liability against saline water.

Salt-induced secondary stress includes the generation of ROS such as hydroxyl radicals, hydrogen peroxide, and superoxide anions, resulting in harms to an array of macromolecules (e.g. lipids), cellular compartments, and physiological functions3. An increased MDA concentration is taken as a reflection of ROS-induced cellular damages. Our data on MDA accumulation in the salt-stricken plants (Fig. 2a) is suggestive of commonality of oxidative damage among the examined genotypes of fennel, ajwain, and anise. The greater increase in the MDA concentration of the anise genotypes (Table 2) indicates a graver lipid peroxidation and hence oxidative damage to this species, compared to fennel and ajwain. Many stresses (including salt stress) induce enzymatic and non-enzymatic systems to scavenge the ROS; the most widely occurring enzymatic scavengers include CAT, superoxide dismutase, and POX3. Interestingly, the APX activities were more or less comparable in the ajwain, fennel, and anise genotypes (Fig. 1b), but the greatest CAT activities were found in the fennel (Table 2; Fig. 1c). Furthermore, the smallest POX activities were detected in the anise genotypes (Fig. 1d). Constitutive expression and activity of antioxidative enzymes in different plant species and differences (i.e. among species) in the level of constitutive activity is established26. Therefore, not only the observed activity of the examined antioxidative enzymes, but the notable differences between the level of activities of APX, CAT, and POX in the non-stressed plants stems also from the constitutive nature of this defense mechanism. The report of de Azevedo Neto et al.27, confirming activation of antioxidative defense of salt-stressed maize plants and a more pronounced antioxidative defense in the salt-tolerant maize genotype in comparison to the salt-sensitive one, is supportive of our findings. Associative relationship between salt tolerance and induction of different antioxidative enzymes in different pea genotypes is confirmed28. The previously discussed increase in Cars concentration of the salt-stressed plants of these three species (Table 2) is suggestive of an accelerated non-enzyme antioxidative defense; albeit, acceleration of this type of defense was more pronounced in fennel and ajwain, compared to anise (Fig. 1a).

A high extracellular level of Na+ in salt-exposed plants creates a steep thermodynamic gradient that favors a passive Na+ influx. Salty ions taken up by the roots are expected to undergo long-distance transport in the transpiration stream to the shoots, leading to an eventual accumulation in the leaves. It is generally thought that (at least for the glycophytes) an increased K+/Na+ selectivity during uptake and reduced Na+ translocation from the root to the shoot are involved in the overall salt tolerance at a whole plant level. The smallest increases in Na+ concentration and, hence, Na+/K+ of salt-stricken plants occurred in the genotype Nahadjan (ajwain), but the smallest K+ concentrations and, hence, the greatest increases in the Na+/K+ belonged to the anise genotypes, i.e. Marvdasht and Isfahan (Table 2). These results are suggestive of a graver disturbed ionic homeostasis in the salt-treated anise, compared to fennel and, particularly, ajwain (Fig. 3a and b). The gravely altered Na+/K+ of the salt-exposed anise in the present study (Fig. 3c) was anticipated, since according to a recent report20 ion homeostasis of anise’s root and shoot were perturbed by 120 mM NaCl. The latter report indicated that 60–87% increases in the anise tissue Na+ concentration were accompanied by 44–66% decreases in K+concentration, compared to the non-stressed plants. Plant cells often maintain the internal steady state despite occurrence of an array of environmental perturbations tending to disturb normality; ions fluxes in a controlled fashion creates an ion homeostasis under normal conditions29. Mechanisms involved in regulation of ion balance and occurrence of osmoregulation, i.e. by the ion accumulation and compartmentation, are among the most important intrinsic cellular-based salt tolerance mechanisms common to different species and genotypes. Osmotic adjustment in plant cells is accomplished by synthesis of compatible osmolytes and absorption of certain inorganic ions from the soil. While osmoregulation must be realized without undue concentration of the inorganic ions in the cytosol, on one hand, the potentially harmful effects of the accumulated ions must be lessened by osmoprotectants (i.e. proline and TSC herein), on the other. The necessity of an ion homeostasis in saline environments is not limited to the glycophytes. Thus, an upregulated expression of ion homeostasis-related genes is observed in the plant species that exhibit a clear halophilism30. The most important mechanisms involved in reduction of cytoplasmic Na+ and hence ion homeostasis include restricting Na+ uptake, increasing Na+ efflux, and compartmentalizing Na+in the vacuole3. Our finding that genotype Yazd (fennel) accumulates the greatest amount of Na+agrees with those of Shafeiee & Ehsanzadeh31, where they defined fennel as a medicinal plant that its tolerance to modest salinities is coupled to notable increases in proline and Na+ concentrations. The increased shoot Na+ concentration of genotype Yazd may have implications in undertaking osmoregulation in this rather salt-resilient fennel genotype. As the salt-exposed plants of the latter fennel genotype tended to sustain the physiological functions, it may be presumed that the potentially toxic Na+ was compartmented in the vacuoles.

The smallest salt-driven decreases in the SDM and TDM belonged to the two fennel genotypes and genotype Ghahdrijan (ajwain). Moreover, the smallest salt-induced decreases in root volume belonged to genotype Shiraz (fennel) and both of the ajwain genotypes. There is no doubt that reduced water supply to plants grown under saline soils conditions contributes to the suppressions in different growth attributes and crop yield32. In fact, the soil volume that is accessed by the growing root system expanding into and the consequent interactions between roots and soil are critical in the quantity of water absorbed and hence salt tolerance of crops. In agreement with the above notion, difference in salt tolerance of maize genotypes was proportional to differences in their root volume33. Findings of the foregone literature and our data, indicating greater root volume of salt-stricken plants of ajwain genotypes and the Shiraz fennel genotype, convinced us to attribute the greater salt tolerance of the mentioned genotypes to the maintained root volume. The foregone results depict anise as a more salt-sensitive medicinal species, compared to ajwain and fennel. In a recent study20, root and shoot dry mass of anise suffered seriously from 120 mM NaCl and (i.e., in line to our findings) it was found to be a salt-sensitive medicinal species. In another earlier study14, ajwain’s seed and plant dry mass were decreased by 50% and 27%, respectively, upon growing in the presence of 120 mM NaCl, which confirms the results of the present work. In contrary to certain rather distant reports that define fennel as a salt-sensitive species34, a recent report31 and the present work set forth fennel as a medicinal species with a modest capability of salt tolerance. Albeit, certain discrepancies and inconsistencies between our findings for some of the traits and the data in the literature is due mostly to differences in cultivars, environments, and experimental conditions. Given the findings of the scanty published works and the findings herein, fennel and ajwain seem to be capable of lowering the osmotic, ion imbalance, and oxidative damages and, hence, SDM and TDM penalties imposed by the saline water, at least in comparison to anise. These capabilities are indebted in part to the greater proline and TSC accumulation and thus RWC, Cars synthesis, CAT and POX activities, and smaller Na+/K+of the fennel and ajwain genotypes examined in this study. Given the frequently reported stress-driven enhancement in the essential oil of different plant species1, particularly fennel13and ajwain14, the increased essential oil concentration in the salt-stricken fennel and ajwain isn’t surprising. Essential oil production is dependent on the metabolic state and background conditions under which the plant developmental program has occurred35 and may vary with environmental conditions such as soil moisture and salinity. Nonetheless, the notable increase in the essential oil concentration of fennel and ajwain plants under saline conditions is a further evidence to the superiority of these salt-tolerant species, compared to anise, as potential alternative crop species amid the aggravating salinity in the agricultural soils of the arid-semiarid regions.

This study was designed and executed to compare the salt responses of three popular medicinal species, i.e. fennel, ajwain, and anise. Growth and dry mass penalties were common among the salt-stricken plants of the examined species. The presented data indicated that anise was more prone to the salt damages, though, salt tolerance capabilities of fennel and ajwain were comparable and, albeit, subject to genotypic differences. Despite the controversies on the importance of antioxidative defense in the plant’s salt response, the gathered data on the response of different genotypes of the present species were suggestive of contribution of root volume, enzymatic and non-enzymatic defenses of at least fennel and ajwain in their salt tolerance. A greater salt tolerance in the latter species was attributed mainly to the increased accumulation of the osmoticums such as proline and TSC, non-enzyme antioxodative molecules such as Cars, and activity of the ubiquitous enzymes such as CAT and POX. Moreover, partly maintained root volume and Na+/K+ contributed to the lowered salt-imposed SDM and TDM suppressions of fennel and ajwain. Our findings pave the way for more focused examinations of root morphology and architecture and further physiological functions of ajwain and fennel genotypes for production under saline field conditions.

Materials and methods

Experimental setup

A randomized complete block design pot experiment was conducted in three replicates during spring to fall 2018 at the Isfahan University of Technology (Latitude of 32º 38ʹ North, Longitude of 51º 39ʹ East, and an Altitude of 1620 m above sea level), Isfahan, Iran. Four levels of salt treatment (i.e. 0, 40, 80, and 120 mM NaCl) were tested on two genotypes of fennel, ajwain, and anise. Weather data indicated the monthly means for the minimum temperature to be 13.0, 20.7, 16.8, 13.5 and those for the maximum temperature to be 29.3, 39.3, 36.9, and 34.4℃ for May, June, July, August, and September, respectively. The seeds were sterilized in a 1% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite solution, washed with distilled water, sown 1 cm deep in germination trays in greenhouse in early-April 2018. Sufficient seedlings of each of the examined genotypes of the three species were produced by planting healthy seeds in these germination trays using a peat moss medium. Three healthy seedlings that were in their 3–4 leaf stage were transferred to each container in 24 to 26 April. Each container was 60 cm tall and 20 cm in diameter and was filled with a 3:1 mixture of a field soil and washed sand. This soil mixture was chosen to obtain a light-textured soil, a facilitated root growth, and subsequently a more accurate assessments on the rooting characteristics. The foregone potting soil was characterized to be a Sandy-Clay-Loam with organic matter = 0.3%, N = 0.063%, P= 33 mg/kg, K = 316 mg/kg, EC = 1.1 dS/m, and pH = 8.0. Since soil analysis did not indicate N, P, and K deficiencies, no fertilizers were applied to the soil. Each experimental unit consisted of two containers encompassing six plants. Four levels of salt treatment (i.e. 0, 40, 80, and 120 mM NaCl) were tested on Shiraz and Yazd genotypes of fennel, Ghahdrijan and Nahadjan genotypes of ajwain, and Marvdasht and Isfahan genotypes of anise two weeks after transferring the seedlings to the containers. The two fennel genotypes (i.e., Shiraz and Yazd) were selected from our previous experiments on the drought- and salt-responsiveness of fennel genotypes31. The seeds of the ajwain (i.e., Nahadjan and Ghahdrijan) and anise genotypes (namely, Isfahan and Marvdasht) were obtained from the Pakan Bazr of Isfahan, central Iran. The seedlings were irrigated with tap water upon necessity for three weeks to ensure uniformly established seedlings in all experimental units. While the control (non-saline) plants were irrigated with tap water, the 40 mM NaCl concentration was applied on May 18, when the plants had 7–9 leaves. In order to avoid an osmotic shock, the 80 and 120 mM levels of salt treatment were applied on May 18 in 2 and 3 steps, respectively. In each experimental unit, one container was subjected to these treatments for five weeks and then the plants were sampled and harvested on June 29 for measuring certain physiological attributes. The remaining container of each experimental unit was treated saline water until physiological maturity, where measuring root and shoot dry mass, root volume, and ion concentrations at the final harvest was carried out. Furthermore, since measurements of EC of the drained water of the containers treated with 80 and 120 mM NaCl indicated salt accumulations over the course of the experiment, the latter containers were subjected to leaching using irrigation with tap water 4 times.

The physiological traits, including Chl, Cars, proline, and TSC concentrations, RWC, MDA, and activity of certain antioxidative enzymes were measured on fresh leaf samples of the plants in one container (i.e. from the two containers of each experimental unit) that had been subjected to different NaCl concentrations for five weeks (i.e. June 30, when the anise plants were in full umbeling stage and those of fennel and ajwain were in in the early umbeling stage). The remaining measurements, including TDM, root volume, seed essential oil concentration, and shoot ionic concentrations were carried out at final harvest, i.e. at 70–80% physiological maturity. The 70–80% physiological maturity occurred at the first week of August for anise and the first week of September for ajwain and fennel.

Measurement of chlorophyll, carotenoids, proline, and total soluble carbohydrates concentrations and relative water content

Samples of 500 mg from photosynthesizing leaves were obtained and prepared for determining Chl concentration. They were extracted using 80% (v/v) acetone, filtered, centrifuged (5810R, Eppendorf Refrigerated Centrifuge, Germany) at 5,000 × g for 10 min. Chl and Cars concentrations were determined by reading the absorbencies (spectrophotometer: U-1800 UV/VIS, Hitachi, Japan) at 645, 663 and 470 nm, respectively and using acetone (i.e. 80%) as blank. Chl and Cars concentrations were quantified according to Lichtenthaler & Wellburn36and details given by Shafeiee & Ehsanzadeh31.

Bates et al.37procedure was used for determining the free proline concentration. Fresh leaf samples of 300 mg were obtained, powdered in aqueous sulfosalicylic acid, prepared for creating the supernatant according to Shafeiee & Ehsanzadeh31. Absorbance was read at 520 nm by spectrophotometer and toluene was used as a blank. Concentration of proline was determined using the standard curve prepared with 0 to 0.1 µg mL[–1 concentrations of this amino acid.

Leaf TSC was determined by homogenization of 300 mg of the fresh samples in 95% ethanol according to the procedure explained by Irigoyen et al.38and the details given in Shafeiee & Ehsanzadeh31 based on reading the absorption of the samples at 625 nm. A glucose standard curve was used for estimating TSC of the samples.

RWC was estimated by measuring fresh masses of the excised leaf discs. The leaf discs were kept in the laboratory in test tubes containing distilled water for 4 h, then the turgid masses were determined following blot drying. These samples were dried for 48 h in an oven at 72ºC. RWC was calculated using the Eq. (1)39.

Measurement of lipid peroxidation and activity of antioxidant enzymes

Thiobarbituric acid (TBA) reaction yields MDA which is a typical product of lipid peroxidation. Thus, lipid peroxidation was assessed in terms of the amount of Thiobarbituric acid reactive substances (TBARS) in the samples (Heath & Packer 1968)40. Fresh leaves were sampled (200 mg) and frozen at −30ºC until further measurements. Then, 0.5 mL of 0.1% three chloroacetic acid (TCA) was applied to the samples, homogenized, and subjected to centrifugation (10,000 g) for 5 min. Then, 1 mL of aliquot of the supernatant was mixed with 4 mL of 0.5% TBA in 20% TCA. Following heating the mixture for 30 min at 95ºC, it was immediately cooled by ice bath. The suspended turbidity was eliminated by centrifugation (10,000 g) and prepared for reading at 532 nm and MDA concentration was determined according to the further details given by Shafeiee & Ehsanzadeh31.

Extracts of 200 mg fresh mass (FM) leaf samples were obtained, transferred to −80ºC, then put into a pre-chilled mortar and pestle and grinded to a powder and homogenized with Na-phosphate buffer. The homogenate was centrifuged, prepared as detailed by Shafeiee & Ehsanzadeh31, and the supernatant was used to measure the protein content according to Bradford41 and assess the activities of the following enzymes.

CAT (EC 1.11.1.6) activity was determined by monitoring diminish in absorbance at 240 nm (by spectrophotometer) measuring the generation of water and oxygen molecules from conversion of H2O2. Specific activity of CAT was measured according to the procedure described by Chance & Maehly42. One unit of CAT activity is the amount of enzyme necessary to decompose 1.0 µmol L[–1 of H2O2 per minute.

The decline in absorbance at 290 nm for 2 min (by spectrophotometer) was monitored and used to measure the oxidation of ascorbate to dehydroascorbate43as a measure of the ascorbate APX (EC 1.11.1.11) activity. One unit of APX activity is the amount of the enzyme needed for the oxidation of 1 µmol of ascorbate per minute31.

POX (EC 1.11.1.7) activity measurement was based on the hike in absorbency at 470 nm for 2 min according to the procedure explained by Herzog & Fahimi44. The activity of enzyme was shown by units mg−1 protein. One unit of POX activity indicates the quantity of enzyme required for oxidation of 1.0 µM of guaiacol in 1 min.

Measurement of seed essential oil concentration, root and shoot dry mass, and ionic concentrations

Severe growth suppression imposed by the 80 and 120 mM NaCl hampered seed production of the anise plants; therefore no sufficient seeds for extracting essential oil were obtained from the anise genotypes. Seed samples of 15 g (for fennel and ajwain plants) were taken, grinded, and subjected to hydrodistillation process at 100 °C in 200 mL of deionized water13. The essential oil phase was separated, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and percent of seed essential oil concentration was determined for fennel and ajwain genotypes.

Plant shoots of the three plants per container were harvested, weighed and dried at 70ºC for 48 h to determine the plant above-ground dry mass (SDM). Plant roots were harvested by washing out the soil carefully. Root volume was measured by laying the roots into a measuring cylinder with a known volume of tap water. Then the oven-dried weight of the roots was measured and used for determining the TDM. After grinding and ashing of the leaf samples for 4 h at 550ºC, the mineral ions were released with 2 N HCl, the concentrations of Na+ and K+ were assessed by a flame photometer (Corning Flame Photometer 410, Corning Medical and Scientific, Halstead Essex, UK) as described in Shafeiee & Ehsanzadeh31.

Statistical analysis

A factorial randomized complete block design was used for executing this experiment. Four levels of salt treatment (i.e. 0, 40, 80, and 120 mM NaCl) were applied on two genotypes of each of the species, i.e. fennel, ajwain, and anise, in three replications. Each experimental unit consisted of two containers and, hence, this experiment comprised of 144 containers representing 72 experimental units. Statistical Analysis Software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA) was used to conduct analysis of variance. Since interaction of species × salinity and species × genotype × salinity were significant, means of the interactions were compared (using least significant difference (LSD)), instead of the means of main effects, i.e. species, genotype, and NaCl concentration.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

de Medeiros, R. L. S., de Paula, R. C., de Souza, J. V. O. & Fernandes J.P.P. Abiotic stress on seed germination and plant growth of Zeyheria tuberculosa. J. Res. 34, 1511–1522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-023-01608-3(2023).

Nxele, X., Klein, A. & Ndimba, B. K. Drought and salinity stress alters ROS accumulation, water retention, and osmolyte content in sorghum plants. S Afric J. Bot. 108, 261–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2016.11.003 (2017).

Yang, Y. & Guo, Y. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms mediating plant salt-stress responses. New. Phytol. 217, 523–539. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14920 (2018).

Fan, Z. et al. Breaking the salty spell: Understanding action mechanism of melatonin and beneficial microbes as nature’s solution for mitigating salt stress in soybean. S Afr. J. Bot. 161, 555–567 .https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sajb.2023.08.056(2023).

Garcia-Caparros, P., Hasanuzzaman, M. & Lao, M. T. Ion homeostasis and antioxidant defense toward salt tolerance in plants. In: (eds Hasanuzzaman, M., Fujita, M., Oku, H., Nahar, K. & Hawrylak-Nowak, B.) Plant Nutrients and Abiotic Stress Tolerance. Springer, Singapore (2018): 415-436.

de Sousa, D. P. F. et al. Increased drought tolerance in maize plants induced by H2O2 is closely related to an enhanced enzymatic antioxidant system and higher soluble protein and organic solutes contents. Theor. Exp. Plant. Physiol. 28, 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40626-016-0069-3 (2016).

Sangu, E., Tibazarwa, F. I., Nyomora, A. & Symonds, R. C. Expression of genes for the biosynthesis of compatible solutes during pollen development under heat stress in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). J. Plant. Physiol. 178, 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2015.02.002(2015).

Yaish, M. W. Proline accumulation is a general response to abiotic stress in the date palm tree (Phoenix dactylifera L). Genetic Molec Res. 14, 9943–9950. https://doi.org/10.4238/2015(2015).

Kumar, D. et al. Effects of salinity and drought on growth, ionic relations, compatible solutes and activation of antioxidant systems in oleander (Nerium oleander L). PLoS ONE. 129, e0185017. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185017 (2017).

Tesfaye, S. G., Ismail, M. R., Ramlan, M. F., Marziah, M. & Kausar, H. Effect of soil drying on rate of stress development, leaf gas exchange and proline accumulation in robusta coffee (Coffea canephora Pierre ex Froehner) clones. Exp. Agric. 50, 458–479. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X15004938( (2014).

Ozel, A. Anise (Pimpinella anisum): changes in yields and component composition on harvesting at different stages of plant maturity. Exp. Agric. 45, 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0014479708006959 (2009).

Oktay, M., Gulcin, I. & Kufrevioglu, O. I. Determination of in vitro antioxidant activity of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) seed extracts. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 36, 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0023-6438(02)00226-8 (2003).

Akbari-Kharaji, M., Ehsanzadeh, P., Gholami Zali, A., Askari, E. & Rajabi-Dehnavi, A. Ratooned fennel relies on osmoregulation and antioxidants to damp seed yield decline with water limitation. Agron. Sustain. Develop. 40, 9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-020-0614-y (2020).

Ashraf, M. & Orooj, A. Salt stress effects on growth, ion accumulation and seed oil concentration in an arid zone traditional medicinal plant ajwain (Trachyspermum ammi [L]. Sprague) J. Arid Environ. 64, 209–220 (2006).

Ullah, H. & Honermeier, B. Fruit yield, essential oil concentration and composition of three anise cultivars (Pimpinella anisum L.) in relation to sowing date, sowing rate and locations. Ind. Crop Prod. 42, 489–499 (2013).

Croft, H. et al. Leaf chlorophyll content as a proxy for leaf photosynthetic capacity. Glob Change Biol. 23, 3513–3524. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13599 (2017).

Guimaraes, G. F., Gorni, P. H., Vitolo, H. F., Carvalho, M. E. A. & Pacheco, A. C. Sweet potato tolerance to drought is associated to leaf concentration of total chlorophylls and polyphenols. Theor. Exp. Plant. Physiol. 33, 385–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40626-021-00220-2(2021).

Pandey, B. R., Burton, W. A., Salisbury, P. A. & Nicolas, M. E. Comparison of osmotic adjustment, leaf proline concentration, canopy temperature and root depth for yield of juncea canola under terminal drought. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 203, 397–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/jac.12207 (2017).

Shinde, S. S., Kachare, D. P., Satbhai, R. D. & Naik, R. M. Water stress induced proline accumulation and antioxidative enzymes in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L). Legume Res. 41, 67–72. https://doi.org/10.18805/LR-3582 (2018).

Sardar, A. et al. Effect of salinity stress on anise (Pimpinella anisum L.) seedling characteristics under hydroponic conditions. J. Environ. Agric. Sci. 14, 39–45 (2018).

Shah, S. H., Houborg, R. & McCabe, M. F. Response of chlorophyll, carotenoid and SPAD-502 measurement to salinity and nutrient stress in wheat (Triticum aestivum L). Agronomy 7, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy7030061 (2017).

Abdehpour, Z. & Ehsanzadeh, P. Concurrence of ionic homeostasis alteration and dry mass sustainment in emmer wheats exposed to saline water: implications for tackling irrigation water salinity. Plant. Soil. 440, 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-019-04090-1(2019).

Solovchenko, A. & Neverov, K. Carotenogenic response in photosynthetic organisms: a colorful story. Photosyn Res. 133, 31–47 (2017).

Zhang, J., Nguyen, H. T. & Blum, A. Genetic analysis of osmotic adjustment in crop plants. J. Exp. Bot. 50, 291–302. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/50.332.291(1999).

Kavi Kishor, P. B. & Sreenivasulu, N. Is proline accumulation per se correlated with stress tolerance or is proline homeostasis a more critical issue? Plant. Cell. Environ. 37, 300–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.12157 (2014).

Abogadallah, G. M. Insights into the significance of antioxidative defense under salt stress. Plant. Signal. Behav. 5, 369–374. https://doi.org/10.4161/psb.5.4.10873 (2010).

de Azevedo Neto, A. D., Prisco, J. T., Eneas-Filho, J., de Abreu, C. E. B. & Gomes-Filho, E. Effect of salt stress on antioxidative enzymes and lipid peroxidation in leaves and roots of salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive maize genotypes. Environ. Exp. Bot. 56, 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2005.01.008 (2006).

Hernandez, J. A., Jimenez, A., Mullineaux, P. & Sevilla, F. Tolerance of pea (Pisum sativum L.) to long-term salt stress is associated with induction of antioxidant defences. Plant. Cell. Environ. 23, 853–862. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-3040.2000.00602.x(2000).

Niu, X., Bressan, R. A., Hasegawa, P. M. & Pardo, J. M. Lon homeostasis in NaCl stress environments. Plant. Physiol. 109, 735–742. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.109.3.735 (1995).

Tran, D. Q. et al. Ion accumulation and expression of ion homeostasis-related genes associated with halophilism, NaCl-promoted growth in a halophyte Mesembryanthemum crystallinum L. Plant. Prod. Sci. 23, 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/1343943X.2019.1647788 (2020).

Shafeiee, M. & Ehsanzadeh, P. Physiological and biochemical mechanisms of salinity tolerance in several fennel genotypes: existence of clearly-expressed genotypic variations. Ind. Crop Prod. 132, 311–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.02.042 (2019).

Schleiff, U. Analysis of water supply of plants under saline soil conditions and conclusions for research on crop salt tolerance. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 194, 1–8 (2008). (2008).

Hu D.D. et al. Endogenous hormones improve the salt tolerance of maize (Zea mays L.) by inducing root architecture and ion balance optimizations. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 208, 662–674 (2022). (2022).

Shannon, M. C. & Grieve, C. M. Tolerance of vegetable crops to salinity. Sci. Hort. 78, 5–38 (1999).

Sangwan, N. S., Farooqi, A. H. A., Shabih, F. & Sangwan, R. S. Regulation of essential oil production in plants. Plant. Growth Regul. 34, 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013386921596 (2001).

Lichtenthaler, H. K. & Wellburn, W. R. Determination of total carotenoids and chlorophylls a and b of leaf extracts in different solvents. Biochem. Soc. Transac. 11, 591–592 (1994).

Bates, L. S., Waldren, R. P. & Teare, I. D. Rapid determination of free proline for water stress studies. Plant. Soil. 39, 205–207 (1973).

Irigoyen, J. J., Emerich, D. W. & Sanchez-Diaz, M. Water stress induced changes in concentrations of proline and total soluble sugars in nodulated alfalfa (Medicago sativa) plants. Physiol. Plant. 84, 55–60 (1992).

Smart, R. E. & Bingham, G. E. Rapid estimates of relative water content. Plant. Physiol. 53, 258–260 (1974).

Heath, R. L. & Packer, L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplasts. I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch. Biochem. Biophysic. 125, 189–198 (1968).

Bradford, M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 (1976).

Chance, B. & Maehly, A. C. Assay of catalase and peroxidase. Method Enzym. 2, 764–775 (1955).

Nakano, Y. & Asada, K. Hydrogen peroxide is scavenged by ascorbate-specific peroxidase in spinach chloroplasts. Plant. Cell. Physiol. 22, 867–880 (1981).

Herzog, V. & Fahimi, H. Determination of the activity of peroxidase. Anal. Biochem. 55, 554–562 (1973).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JN, PE, and MHE designed the experiment. JN conducted the experiment, collected and analyzed the data, and prepared Figs. 1, 2 and 3. PE and MHE supervised the study. PE prepared the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nouripour-Sisakht, J., Ehsanzadeh, P. & Ehtemam, M.H. Comparative response of fennel, ajwain, and anise in terms of osmolytes accumulation, ion imbalance, photosynthetic and growth functions under salinity. Sci Rep 15, 2520 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86256-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86256-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Multifaceted Adaptation of Hyssop To Salt Stress Integrating Organ-Specific Ionomic, Photosynthetic, Oxidative Stress Management, and Metabolic Mechanisms

Journal of Soil Science and Plant Nutrition (2025)