Abstract

Ocean surface temperatures and the frequency and intensity of marine heatwaves are increasing worldwide. Understanding how marine organisms respond and adapt to heat pulses and the rapidly changing climate is crucial for predicting responses of valued species and ecosystems to global warming. Here, we carried out an in situ experiment to investigate sublethal responses to heat spikes of a functionally important intertidal bivalve, the venerid clam Austrovenus stutchburyi. We describe changes in metabolic responses under two warming scenarios (five days and seven days) at two sites (muddy and sandy). Tidal flat warming during every low tide for five days affected the abundance of multiple functional metabolites within this species. The metabolic response was related to pathways such as metabolic energetics, amino acid and lipid metabolism, and accumulation of stress-related metabolites. There was some recovery after cooler weather during the final two days of the experiment. The degree of change was greater in muddy versus sandy sediments. Our findings provide new evidence of the metabolomic response of these important bivalve to heat stress, which could be used for resource managers when implementing strategies to mitigate the impacts of climate change on valuable marine resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change is affecting ecosystems worldwide. Earth’s temperature is gradually increasing due to elevated anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions1,2,3. Global ocean surface temperatures have increased 1.5 °C on average since 1860, with future projections suggesting that temperatures will continue to rise, driving sea-level rise, sea-ice and glacial melting, and the potential for more frequent and intense extreme weather events such as storms, tropical cyclones, and marine heatwaves2,4,5. These drivers are likely to affect marine organisms and ecosystems both directly and indirectly3,6,7,8.

Aperiodic extreme events (e.g., storms, heatwaves) and periodic cycles (e.g., seasons, tides, climate oscillations) are natural and have influenced estuarine and coastal marine ecosystems for longer than humans have been present on Earth. However, the rapidly warming climate has affected natural processes, including the frequency and intensity of storms and heatwaves, which is modifying biological communities in estuaries around the world, influencing the distributional ranges, life history strategies, and survival of organisms4,9,10.

Marine heatwaves are prolongated periods (> 90th percentile for five or more days) of anomalously high sea surface temperatures5,11,12, to which organisms must respond through acclimation, adaptation, relocation, or extinction5,12,13. Marine heatwaves, in combination with atmospheric heatwaves (i.e., prolonged periods of abnormally hot weather relative to the expected conditions), can profoundly affect the fitness of organisms, especially ectotherms which represent more than 95% of described marine taxa, as their physiological processes are largely temperature-dependent14,15,16,17. Temperature affects ectotherm metabolism14,15, which in turn can modify growth and reproductive rates, maximum body sizes, feeding behaviours, and other vital functions15,18,19,20.

The effects of heat stress on marine bivalves have been widely studied in laboratory set-ups and using commercially-important species, revealing effects of heat stress on bivalve growth, oxygen consumption, ammonia excretion, and metabolic changes21,22,23,24,25. Despite increasing general understanding of the ecological impacts of global warming on marine ecosystems and in few commercial shellfish species in laboratory conditions, effects on key species and valued resources in specific localities are often uncharacterised, limiting our ability to design effective conservation and management strategies that meet the needs of society. In this study, we carried out an in situ warming experiment to investigate metabolic responses of a culturally and ecologically important estuarine species in New Zealand. We focused specifically on the bivalve, Austrovenus stutchburyi (also known as cockle), which plays a pivotal role in soft sediment habitats throughout New Zealand by actively dispersing, mixing, and modifying the sedimentary environments it occupies. These suspension-feeding bivalves affect sediment biogeochemistry and pore water solute exchanges through bioturbation and biodeposition26,27. Cockles are known to support upper trophic levels (e.g., food for eagle rays, shorebirds) and are gathered as food by indigenous Māori, other recreational harvesters, and commercial fisheries28,29,30,31.

The objective of this study was to investigate and illustrate the metabolic responses of Austrovenus stutchburyi to elevated temperatures during low tide. We designed an experiment with two short-term warming scenarios (5- and 7-days duration) at each of two sites (sandy, muddy) in a North Island New Zealand estuary (Fig. 1) that five local Māori tribes (Ngāti Whakahemo, Ngāti Whakaue ki Maketū, Ngāti Mākino, Ngāti Pikiao, and Tapuika) are actively trying to restore. We hypothesised that metabolism would be elevated in warmed relative to ambient conditions, that responses (measured as metabolic abundance) would be stronger with a longer duration of warming (7 days, relative to 5 days), and that responses would be stronger in sandy sediments (more suitable habitat for cockles32), relative to muddy sediments.

Map of the study area showing (a) the location of Waihī Estuary in New Zealand, (b) experimental site locations in Waihī Estuary, (c) the arrangement of treatment plots in a randomised block design at each site, (d) birds-eye view of Open Top Chambers, OTCs, and control plots at the Mud site; (e) close-up view of OTC showing position of stake with temperature loggers attached (inset is study organism, the New Zealand cockle, Austrovenus stutchburyi). Maps in figures (a), (b), and (c) were created in ArcGIS Pro v.3.3 (ESRI – www.esri.com), and photos in (d) and (e) were taken by Stuart Mackay (NIWA).

Results

Seafloor temperature and sediment characteristics

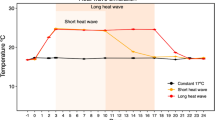

Mean sediment temperatures recorded during the experiment ranged from 22.5 °C to 28.0 °C, and from 22.5 °C to 34.0 °C in the OTC treatments (Fig. 2). Mean temperature differed significantly by treatment (p < 0.05; Table 1; Fig. 2), but no significant differences were observed between sites and the Site × Treatment interaction was not significant (p > 0.05; Table 1; Fig. 2). Pairwise tests revealed that both Short and Long OTC treatments had significantly higher temperatures than Controls (p < 0.05; Table 1; Fig. 2). Combining all experimental days together (i.e., temperatures recorded during OTC incubations), temperature differed significantly between Controls and OTCs (Long and Short) at the Sand site, and all three treatments were significantly different from each other at the Mud site (Table S1; Figure S1).

Boxplots showing the sediment temperature (°C) recorded during the seafloor warming experiment period (eight consecutive days) across sites (Sand, Mud) and treatments (Control, Short, Long). Note the lower temperatures and smaller control-treatment differences on days 7 and 8 due to the arrival of cooler, cloudier weather. Thick lines = median, dots = outliers.

Experimental treatments were unlikely to have any effect on sediment characteristics such as grain size. Analysis confirmed that sediment mud content (percent silt and clay particles < 63 µm) differed significantly by site (Mud > Sand), but not by treatment. Patterns observed for the other sediment properties assessed were idiosyncratic: site × treatment interactions for chlorophyll-a and phaeophytin, and site and treatment effects for organic matter content (Table S2, Figure S2).

Effects of seafloor warming on shellfish metabolites

In total, 46 metabolites were identified in Austrovenus stutchburyi adductor muscle tissue across sites and treatments (Table 2). The average abundance of metabolites per sample differed significantly by site and treatment, and there was also a significant site × treatment interaction (Table 3, Fig. 3a). Metabolite abundance was higher at Mud than at Sand in all treatments, and considerably higher in the Short treatment (Fig. 3a). For example, metabolite abundances in Control and Short treatments were both significantly greater at Mud than at Sand (Fig. 3a). Among treatments, metabolite abundance was highest in the Short duration treatment (but significantly higher than the other treatments at Mud only; Fig. 3a).

Boxplots showing (a) total metabolite abundance (biomass) and (b) metabolite diversity (Shannon-Weiner) recorded in plots during the experiment (Sites: Sand, Mud; Treatments: Control, Short, Long). Significant differences p < 0.05 between treatments within a site are shown as “a, b, c”, while significant differences (p < 0.05) within treatments between sites are indicated with “*”. Thick lines = median, dots = outliers.

Patterns of metabolite diversity were less clear (Fig. 3b). Metabolite diversity differed by site, and there was a significant site x treatment interaction (Table 3, Fig. 3b). Metabolite diversity values in Control and Long treatment plots were both significantly higher at Sand than at Mud (Fig. 3b). However, patterns for the Short treatment were divergent, i.e., significantly lower than other treatments at Sand, and significantly higher than other treatments at Mud.

Significant differences in metabolomic composition (the presence and relative abundance of all metabolites) were detected between sites and treatments using multivariate analyses (p < 0.05; Table 3, Fig. 4). The bootstrapped nMDS ordination plot showed distinct metabolite composition according to site and treatment, with a clear separation between the metabolite composition at Sand and Mud (Fig. 4). Post-hoc pairwise tests revealed that all sites and treatments were significantly different from one another (p < 0.05; Fig. 4).

Bootstrapped non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (nMDS) ordination plot showing the metabolomic composition across sites and treatments. Triangles (Sand) and Circles (Mud) indicate average multivariate metabolite composition at each Site. Control, Short, and Long treatments are indicated with green, yellow, and blue colours, respectively. Symbols close together in ordination space indicate greater similarity in multivariate composition.

Of the 46 metabolites recorded, SIMPER analysis identified six metabolites as the main drivers of differences between sites and treatments: Alanine, Aspartic acid, Glycine, Glutamic acid, Proline, and Succinic acid (Fig. 5; Table S3). Overall, most of the differences in metabolite concentrations were identified in the Short treatment at Mud, relative to the Sand site or any other treatment (Table 4; Fig. 5). The concentrations of Alanine, Glycine, Glutamic acid, Proline, and Succinic acid were significantly higher in Short compared to the other treatments in Mud site (p < 0.05; Table 5; Fig. 5). At the Sand site, the concentrations of Alanine and Glycine were significantly higher in Short treatment compared to Control and Long treatments, while the concentrations of Aspartic acid and Glutamic acid were significantly higher in Long treatment compared to the other treatments (p < 0.05; Table 5; Fig. 5). The concentrations of Proline and Succinic acid across treatment were significantly different only in Mud site, while in Sand site concentrations were similar (p < 0.05; Table 5; Fig. 5). Significant differences across all treatments in concentrations of metabolites between Sand and Mud site were identified for Glycine, while the concentrations of Alanine, Aspartic acid, Glutamic acid, Proline, and Succinic acid recorded in Control and Short treatments were significantly different between sites (p < 0.05; Table 5; Fig. 5).

Boxplots showing the abundance (biomass) of the most relevant metabolites expressed (identified by the SIMPER analysis) during the seafloor warming experiment: (a) Alanine, (b) Aspartic acid, (c) Glycine, (d) Succinic acid, (e) Proline, and (f) Glutamic acid across sites (Sand, Mud) and treatments (Control, Short, Long). Significant differences p < 0.05 between treatments within a site are shown as “a, b, c”, while significant differences (p < 0.05) across treatments between sites are shown as “*”. Thick lines = median, dots = outliers.

The network-based enrichment analyses identified 17 metabolic pathways affected by the seafloor warming experiment (Table 6; Figs. 6 and 7). At the Sand site, 15 metabolic pathways were affected by warming, with nine metabolic pathways identified in each Short and Long treatment (Table 6; Fig. 6). At the Mud site, nine metabolic pathways were affected by the warming experiment. The Short and Long treatments affected eight and five metabolic pathways, respectively (Table 6; Fig. 7). Of the 17 metabolic pathways affected, glutathione metabolism was the metabolic pathway most affected (identified in both warming treatments at both sites), followed by beta-alanine metabolism and vitamin B6 metabolism pathways that were identified in Short and Long treatments at Sand, and in Short treatments at Mud. Arginine and proline metabolism pathways were affected in Long treatments at Sand, and in Short and Long treatments at Mud (Table 6; Figs. 6 and 7).

Metabolic network-based enrichment pathways (p-score < 0.05) in Austrovenus stutchburyi. The connections show the metabolic pathways affected in (a) Short and (b) Long warming in site Sand. Red circles: pathways; purple circles: modules; yellow circles: enzymes; blue circles: reactions; green circles: compounds; green squares: input compounds. Labels of modules, enzymes, reactions, and compounds are shown in Figure S3.

Metabolic network-based enrichment pathways (p-score < 0.05) in Austrovenus stutchburyi. The connections show the metabolic pathways affected in (a) Short and (b) Long warming in site Mud. Red circles: pathways; purple circles: modules; yellow circles: enzymes; blue circles: reactions; green circles: compounds; green squares: input compounds. Labels of modules, enzymes, reactions, and compounds are shown in Figure S4.

Discussion

Global warming is increasing land and sea surface temperatures, which intensify the frequency and severity of extreme weather events such as marine heatwaves. Warmer, longer, and more frequent marine heatwaves are driving significant changes in the metabolic rates, growth, reproduction, and survivorship of marine organisms with implications at individual, population, community, and ecosystem levels. In this study, we investigated metabolic responses of a key ecosystem engineer—the New Zealand cockle, Austrovenus stutchburyi—at two sites with different sedimentary conditions and following exposure to two different durations of warming. Our results demonstrated that seafloor warming affects the metabolite abundance in cockles, altering their energetics, amino acid and lipid metabolism, and contributing to the accumulation of stress-related metabolites, with greater effects in muddy sediment compared to sandy sediments.

Under normal conditions, bivalves maintain a balance of metabolites to support growth, reproduction, and survival. Yet, during heatwaves, metabolic rates of bivalves are likely to accelerate, leading to higher energy demands and changes in metabolic pathways21,22,23,33,34. We hypothesised that the metabolic response of Austrovenus stutchburyi to seafloor warming would be stronger following longer periods of warming, relative to short, and that responses would be stronger in sandy sediments compared to muddy sediments. Results of our study were contrary to both hypotheses.

The context and details of our experiment may have affected the results. The OTCs imposed heat stress through passive warming, and the magnitude of stress depended on the weather at the time of the field work. During the first six days of the experiment, maximum daily air temperatures were increasing and the weather was fine and sunny. Cloudy and cooler conditions occurred on days seven and eight, thus, the heating imposed by the heat (OTC) treatments was reduced during the final two days of the experiment. This would have affected the Mud site slightly more than the Sand site because Mud site had two cooler days at the end of the experiment, compared to one cooler day at Sand (Fig. 2). This relaxation in heat stress at the end of the experiment may have allowed for some recovery in the cockles and concomitant changes in metabolites detectable in their tissues. For example, it could explain why the highest abundance of metabolites was detected in the Short, rather than Long, heat exposure treatment (significantly so at Mud; Fig. 3). It also explains why the multivariate dissimilarity in metabolite composition (Fig. 4) was greatest between Control and Short treatments, particularly at the Mud site. Furthermore, the OTCs were removed during high tide which could also influence the metabolomic response of cockles due to relaxation in heat stress, movements of individual cockles into or out of plots, and the deeper burrowing behaviour of cockles when undergoing thermal stress35,36.

We identified an interesting pattern of significant increase and decrease in metabolites such as Alanine, Carbamic acid, Lysine, Methionine, Ornithine, Phenylalanine, Proline, and Succinic acid between Short and Long treatments in Sand and Mud sites. In Sand site, metabolites decreased in Short treatment and increased in Long treatment, while in Mud site results showed the opposite pattern. The higher metabolic responses observed in muddy sediments could be the result of less stratification and maintenance of warmer temperatures compared to sandy sediments. Sandy sediments tend to dry out at low tide and warm faster, but also release heat faster with the tidal flooding, in contrast to muddy sediments that remain in a state of near saturation at low tide, develop less stratification of temperature, and maintain heat/cold levels with tidal flooding37,38. These statements align with our results suggesting that muddy sediments trapped warmer temperatures and enhanced metabolomic activities to a greater degree than the sandier sediments.

Metabolic responses (i.e., changes in metabolite abundance, diversity, and composition) of Austrovenus stutchburyi were likely related to changes in physiological rates and biochemical reactions, for example, energy and oxygen demanding processes. Our analyses revealed several metabolites and metabolic pathways that responded to the heat stress treatments of our in situ experiment. These responses were mainly related to (1) effects on energy metabolism, (2) accumulation of stress-related metabolites, (3) disruption of amino acid metabolism, and (4) impacts on lipid metabolism, which we discuss in the sections below.

Energy metabolism

Marine bivalves rely on a finely tuned balance of energy metabolism to sustain essential biological functions, including growth, reproduction, and maintenance of homeostasis. Previous studies have shown that heat stress affects both the energy balance and homeostasis of marine bivalves23,33,39. Bivalve metabolism typically relies on oxygen (aerobic metabolism), with oxygen used to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP), generating a steady supply of energy to support various physiological processes. Elevated temperatures can reduce concentrations of dissolved oxygen in sedimentary pore water. Importantly, elevated temperatures can also accelerate metabolic rates in bivalves, leading to increased energy demands and causing a shift from aerobic to anaerobic respiration pathways22,23,33,34,39,40. This shift results in activation of beta-alanine pathway and the accumulation of anaerobic metabolites such as lactate, succinate, and alanine, which aligned with our findings, as these metabolites are suggested byproducts of anaerobic glycolysis and are indicative of metabolic stress, signalling a reduced efficiency in energy production23,33,39,41. Accelerated metabolism of bivalves as response to warming temperatures also accumulates metabolites within the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle to supports increased energy demands and higher metabolic rates due to heat stress, which in turn increases the abundance of aspartic and glutamic acids supporting replenishing functions towards the TCA cycle33,34, which aligned with our results that showed increases on aspartic and glutamic acids.

Stress metabolites

Seafloor warming may trigger increases in stress-related metabolites, which play crucial roles in protecting bivalve cells from thermal damage. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are among the most critical stress-related metabolites that increase during heat stress. Elevated ROS levels can lead to oxidative stress, damaging cellular components such as lipids, proteins, and DNA33,34,41,42. Our results showing increases in proline, taurine, glycine, and activation of arginine and proline pathways in response to heat stress, which align with previous studies suggesting that bivalves produce osmolytes such as these metabolites during heat stress. These osmolytes stabilize proteins and membranes, helping cells maintain their structure and function under thermal stress34,39,42. However, the sustained production of osmolytes during extreme warming events can be energetically costly and may divert resources away from other critical processes such as growth, reproduction, and immune responses, which could affect the fitness of bivalves, making them more susceptible to additional stressors such as disease or predation33,34.

Amino acids

Amino acids are essential building blocks for proteins and play a vital role in numerous metabolic pathways, including the synthesis of enzymes, hormones, and structural proteins. The metabolism of amino acids is closely linked to the overall health and function of marine bivalves, however, under heat stress conditions a disruption of the normal metabolic processes occurs, leading to significant alterations in amino acid profiles. Our findings indicated increases in proline and arginine, and the activation of arginine and proline metabolism pathways following heat stress. These results aligned with previous studies in other bivalve species showing that elevated temperatures increased the levels of specific free amino acids, such as proline and arginine33,34,41,42.

Proline accumulation is particularly important, as it provides multiple protective roles during thermal stress. Proline acts as an osmoprotectant, stabilizing proteins and membranes, and as a scavenger of ROS, reducing oxidative damage39,43. The increased synthesis of proline in response to heat stress reflects an adaptive mechanism aimed at enhancing cellular protection and survival. Arginine, another amino acid that often increases during heat stress, plays a key role in the production of nitric oxide (NO), a signalling molecule involved in vasodilation, immune responses, and cellular defence mechanisms. The upregulation of arginine metabolism during heat stress may be part of a broader adaptive response aimed at enhancing cellular protection and maintaining homeostasis under adverse conditions33,34,39. Yet, heatwaves and heat-spikes may disrupt amino acid metabolism, affecting the production of essential enzymes, structural proteins, and other critical molecules. This may lead, for example, to the accumulation of nitrogenous waste products, such as ammonia, that could further stress the organism23,34,39.

The disruption of amino acid metabolism could also affect immune responses of bivalves. Arginine and glutamine, for example, are thought to be critical for the synthesis of immune-related proteins and the functioning of immune cells33,34,42. Our results also indicated effects on the glutathione metabolism pathway (increases of glutathione, glycine, and glutamic acid) as a result of heating. Previous studies suggested that glutathione is an important antioxidant molecule with the ability to scavenge reactive oxygen species21,23,24,33,34. Our results also showed responses of the vitamin B6 metabolism pathway to warming temperatures. Vitamin B6 is a critical co-factor for a diverse range of biochemical reactions that regulate basic cellular metabolism, including decarboxylation, transamination, elimination, racemization, and transsulfuration reactions which impact overall physiology21,44. Decreases in nicotinic acid (a form of vitamin B and related to the vitamin B6 metabolism pathway) were identified, which suggests an increased use of these metabolite to prevent effects on oxidative stress and maintain the stability of DNA and cell structure21.

Lipids

Lipids are essential for physiological functions in marine bivalves, including energy storage, membrane structure, and signalling pathways. The metabolic processes driving lipid synthesis, storage, and use are highly sensitive to environmental change, including temperature fluctuations caused by marine heatwaves23. Our results showed alterations in fatty acid biosynthesis and Wnt signalling metabolic pathways as result of elevated temperatures, significantly altering lipid metabolism in bivalves, leading to changes in both the quantity and composition of lipids. We also identified decreases in palmitic acid and pentadecanoic acid, which suggest that cockles used lipid energy reserves for the production of acetyl CoA—a byproduct of fatty acids oxidation, an important intermediate metabolite of the Krebs cycle, aligning with findings in other bivalve species23,33. Another critical aspect of lipid metabolism is the composition of membrane lipids. Higher temperatures can increase the saturation of fatty acids, resulting in reduced membrane fluidity as observed previously21,23. Reduced membrane fluidity can impair the function of membrane-bound proteins, including those involved in ion transport, signal transduction, and cellular communication, disrupting cellular homeostasis and leading to a loss of cellular integrity.

Conclusion

This study investigated the metabolic response of Austrovenus stutchburyi to an in situ seafloor warming experiment. Our findings revealed the metabolites and metabolic pathways affected by warming stress. We provide evidence showing that metabolic disruptions caused by extreme temperature events, including alterations in energy metabolism, stress-related metabolites, amino acid profiles, and lipid composition, can result in profound effects on bivalve physiology and functioning. The observed metabolic responses indicate that bivalves in sandy sediments could have greater resilience and adapt better to warming scenarios. Strategies to mitigate the impacts of climate change on these valuable marine resources should also explore the long-term impacts of marine heatwaves on bivalve metabolism to identify potential avenues for enhancing the resilience of these organisms in a warming world.

Methods

Study area

The seafloor warming experiment was carried out in Waihī Estuary, in the Bay of Plenty region, near Maketū and Pukehina Beach, North Island, New Zealand (Fig. 1a,b). Waihī Estuary is a tidal lagoon type estuary (tidal range 1.7 m) that is permanently open to the sea and dominated by intertidal soft-sediment flats (57% of the estuary). It has a relatively high freshwater inflow volume for an estuary of its size (2.6 km2 surface area), with freshwater arriving from three main channelised streams (Fig. 1). Previous habitat mapping in Waihī Estuary described eleven habitat classes, including “High Density cockle”, seagrass, and mangrove45. The 2024 habitat mapping effort informed site selection for the present study, with two experimental sites (each 10 × 60 m) established in sandy and muddy intertidal areas which were 200 m apart and of similar freshwater influence (Fig. 1b). The first site, Sand, had a lower proportion of silt–clay (17.25%) and moderate-to-high cockle densities (~ 764 per m−2). The second site, Mud, had a greater proportion of silt–clay (26.65%) and a lower abundance of cockles (~ 128 per m−2) (Fig. 1b).

Experimental design and set up

The experiment was conducted over an eight-day period at the peak of summer in New Zealand (16–23 February 2024). At the start of each low tide period during those days, as soon as the tidal flats were exposed to air, we deployed purpose-built open topped chambers (OTCs) to the tidal flats at each site (Fig. 1b,c). The OTCs were designed to promote the passive heating of enclosed sediments. The cone-shaped OTCs (80 cm base diameter, 30 cm top diameter) were constructed from transparent polycarbonate plastic (1.5 mm thickness) (Fig. 1e). All control and OTC plots received similar natural incoming sunlight radiation, but OTCs prevented convective cooling by the wind. Temperatures at the sediment surface were significantly warmer inside the OTCs (described in Results), while the opening at the top minimised differences in relative humidity.

OTCs were deployed (bottom edge pushed 1 cm into the sediment surface) at each site for four hours during daytime low tides for a period of either five or seven days (Short and Long duration treatments, respectively) as we were interested in the cumulative short-terms effects emulating the effects of a marine heatwave. For logistical reasons, the experiment started and ended one day later at the Mud site, but OTCs were deployed simultaneously at both sites for the majority of the experimental period (i.e., days 2–7). Temperatures increased inside OTCs over the 4 h deployment period, with differences between control (without OTCs) and treatment plots highest on sunny, breezy days (up to 4 °C). OTCs were removed each day prior to inundation by the tide and stored above the high tide mark overnight, thus, plot sediments were unenclosed and ‘untreated’ at night and during every high tide period during the experiment.

Ten replicate plots per treatment (Control, Short, Long) were established within the 10 × 60 area at each site, arranged using a randomised block design (same configuration at both sites). All plots were separated by 5 m. The design enabled statistical analysis based on two orthogonally crossed factors: Site (two levels: Sand, Mud) and Treatment (three levels: Control, Short, Long) (Fig. 1b,c). Sixty experimental plots were sampled in total (Fig. 1b,c).

Data collection

Environmental data

Temperatures (°C) inside all control and treatment plots were measured using temperature loggers (EnvLoggers, Electric Blue CRL) located 1 cm below and 5 cm above the sediment surface on wooden stakes (Fig. 1e). Temperatures were recorded every minute and logged in all plots (Control, Long, Short) during the experiment.

Sediment characteristics were determined from small cores of sediment (26 mm diameter × 20 mm deep) collected from each plot. Grain size (e.g., silt–clay content), microalgal pigment concentrations (e.g., chlorophyll-a, phaeophytin), and organic matter content (e.g., combustible fraction) were quantified using previously reported standard methods45,46,47.

Bivalve sampling

Austrovenus stutchburyi (Fig. 1e) were collected from each plot by hand (probing the upper 0–5 cm of the sediment column with fingertips to find and remove cockles). Ten A. stutchburyi individuals were collected per plot, except for two plots (1 Short and 1 Long) at the Mud site where fewer than ten total individuals were found. If more than ten cockles were found, we selected the ten largest individuals (20–30 mm) available for subsequent processing. Immediately after collection, cockles were dissected to remove all the muscle tissues to obtain a holist picture of the metabolic composition of this bivalve. Muscle tissue from the ten cockles per plot were combined into one representative sample per plot. Samples were snap frozen and stored in liquid N2 until further laboratory processing.

Metabolomic data

A methyl chloroformate (MFC) alkylation derivatisation method was used for the analysis of metabolites in the adductor muscle tissue of the cockles, following protocols described by48. This method was used to distinguish amino and non-amino organic acids, and some primary amines and alcohols48. Briefly, samples were first dried using a refrigerated vapor trap SpeedVac concentrator (Thermo Scientific, New Zealand). Metabolite extraction was performed on each sample by adding a cold 1:1 methanol:water solution to the dried samples. Samples were vortexed and centrifuged, and the supernatants (derivatized samples) were then analysed with a gas chromatograph GC7890B coupled to a quadruple mass spectrometer MSD5977A (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). Different types of quality controls (QC) were used to ensure reproducibility of MFC measurements, which included blank samples, amino acid mixtures, and pooled QC samples from all samples48. The analysis of raw spectral data, data mining, and metabolite identification was performed using Chem Station (Agilent Technologies, Inc., US), Automated Mass Spectral Deconvolution and Identification System (AMDIS) software (http://www.amdis.net), and MassOmics R package—The University of Auckland49. Metabolomic data was normalised to biomass and the internal standard to compensate for potential technical variations prior to data analyses. MFC analysis, data mining, and metabolite identification were performed by the Mass Spectrometry Centre, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand.

Data analysis

Data recorded by the temperature loggers were analysed using the ‘myClim’ package50 in R software51. Temperature data were first trimmed to only include times when the OTCs were deployed. The one-minutely data from above and below the sediment surface from these periods were then averaged, providing one representative value per day per plot.

To test for differences in temperature, sediment characteristics, and to evaluate the effects of seafloor warming on shellfish metabolomic abundance (metabolite biomass, and diversity) between fixed factors (Site, Treatment), univariate PERMutational ANalysis Of VAriance (PERMANOVA) tests were conducted. PERMANOVA tests were based on Euclidean distance for the single variables, permutation of residuals under a reduced model, Type III sums of squares, and 9999 permutations. In addition, multiple contrasts (pair-wise tests with 9999 permutations) were conducted if fixed factors were significant in the main tests. Boxplots were constructed using the package ‘ggpubr’52 in R software (R Core Team 2022).

To assess metabolomic composition and investigate differences between sites and treatments, a bootstrapped non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (nMDS) ordination was created based on Bray–Curtis similarities53. To test for differences in metabolomic composition between sites and treatments, a PERMANOVA test was performed using Bray Curtis similarities, permutation of residuals under a reduced model, Type III sums of squares, and 9999 permutations53. As above, multiple contrasts were conducted if main effects were significant.

A SIMilarity PERcentage breakdown (SIMPER) analysis53 was carried out to determine metabolites accounting for > 70% of the dissimilarity between sites and treatments. The metabolites identified by the SIMPER analyses, as well as all the other metabolites identified, were also compared among sites and treatments following the same methodology as previously described. PERMANOVAs, bootstrap nMDS, and SIMPER analysis were carried out using PRIMER v7 software with PERMANOVA add on.

To investigate the metabolites and metabolomic pathways significantly affected by experimental factors (Site, Treatment), four network-based enrichment analyses were performed. The four network-based enrichment analyses (one for each treatment-site) were constructed based on the reference pathway library of Ruditapes philippinarum (Manila clam -Veneridae), which was judged to be the most closely related bivalve to Austrovenus stutchburyi available in the Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database54. Pathways involving one or more annotated metabolites that matched with the KEGG database with enrichment analysis p-scores < 0.05 were considered as potential primary pathways affected. Network-based enrichment analyses were constructed based on the method “diffusion”, limited number of nodes of 200, and 0.05 threshold55 using the R package “FELLA”56.

Data availability

All the data used is presented in the article and supplementary materials.

References

Wong, C. Earth just had its hottest year on record—Climate change is to blame. Nature 623, 674–675. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-03523-3 (2023).

IPCC. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds H.-O. Pörtner et al.) 2897–2930 (2022).

Huguenin, M. F., Holmes, R. M. & England, M. H. Drivers and distribution of global ocean heat uptake over the last half century. Nat. Commun. 13, 4921. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-32540-5 (2022).

Prum, P., Harris, L. & Gardner, J. Widespread warming of earth’s estuaries. Limnol. Oceanogr. Lett. 9, 268–275. https://doi.org/10.1002/lol2.10389 (2024).

Oliver, E. C. J. et al. Longer and more frequent marine heatwaves over the past century. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03732-9 (2018).

Deng, W. Ocean warming and warning. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 118–119. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01921-z (2024).

Li, Z., England, M. H. & Groeskamp, S. Recent acceleration in global ocean heat accumulation by mode and intermediate waters. Nat. Commun. 14, 6888. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-42468-z (2023).

Kruft Welton, R. A., Hoppit, G., Schmidt, D. N., Witts, J. D. & Moon, B. C. Reviews and syntheses: The clam before the storm—A meta-analysis showing the effect of combined climate change stressors on bivalves. Biogeosciences 21, 223–239. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-21-223-2024 (2024).

Campana, S. E., Stefánsdóttir, R. B., Jakobsdóttir, K. & Sólmundsson, J. Shifting fish distributions in warming sub-Arctic oceans. Sci. Rep. 10, 16448. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73444-y (2020).

Scanes, E., Scanes, P. R. & Ross, P. M. Climate change rapidly warms and acidifies Australian estuaries. Nat. Commun. 11, 1803. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15550-z (2020).

Hobday, A. J. et al. A hierarchical approach to defining marine heatwaves. Progress Oceanogr. 141, 227–238 (2016).

Gomes, D. G. E. et al. Marine heatwaves disrupt ecosystem structure and function via altered food webs and energy flux. Nat. Commun. 15, 1988. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-46263-2 (2024).

McGaughran, A., Laver, R. & Fraser, C. Evolutionary responses to warming. Trends Ecol. Evol. 36, 591–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2021.02.014 (2021).

Valente, S. & Colloca, F. A dataset of thermal preferences for Mediterranean demersal and benthic macrofauna. Sci. Data 11, 314. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-024-03168-5 (2024).

de Luzinais, V. G., Gascuel, D., Reygondeau, G. & Cheung, W. W. L. Large potential impacts of marine heatwaves on ecosystem functioning. Global Change Biol. 30, e17437. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.17437 (2024).

Barriopedro, D., García-Herrera, R., Ordóñez, C., Miralles, D. G. & Salcedo-Sanz, S. Heat waves: Physical understanding and scientific challenges. Rev. Geophys. 61, e2022RG000780. https://doi.org/10.1029/2022RG000780 (2023).

Harrington, L. J. & Frame, D. Extreme heat in New Zealand: A synthesis. Clim. Change 174, 2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-022-03427-7 (2022).

Payne, N. L. et al. Temperature dependence of fish performance in the wild: Links with species biogeography and physiological thermal tolerance. Funct. Ecol. 30, 903–912 (2016).

Lear, K. O. et al. Divergent field metabolic rates highlight the challenges of increasing temperatures and energy limitation in aquatic ectotherms. Oecologia 193, 311–323 (2020).

Plumlee, J. D. et al. Increasing duration of heatwaves poses a threat to oyster sustainability in the Gulf of Mexico. Ecol. Indicat. 162, 112015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.112015 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Responses of digestive metabolism to marine heatwaves in pearl oysters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 186, 114395 (2023).

Georgoulis, I. et al. Metabolic remodeling caused by heat hardening in the Mediterranean mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis. J. Exp. Biol. 225, 244795 (2022).

Jiang, Y., Jiao, H., Sun, P., Yin, F. & Tang, B. Metabolic response of Scapharca subcrenata to heat stress using GC/MS-based metabolomics. PeerJ 8, e8445 (2020).

Nguyen, T. V., Alfaro, A. C., Young, T., Ravi, S. & Merien, F. Metabolomics study of immune responses of New Zealand greenshell™ mussels (Perna canaliculus) infected with pathogenic Vibrio sp. Mar. Biotechnol. 20, 396–409 (2018).

Azizan, A. et al. Metabolite changes of Perna canaliculus following a laboratory marine heatwave exposure: Insights from metabolomic analyses. Metabolites 13, 815 (2023).

Lohrer, A. M. et al. Influence of New Zealand cockles (Austrovenus stutchburyi) on primary productivity in sandflat-seagrass (Zostera muelleri) ecotones. Estuarine Coast. Shelf Sci. 181, 238–248 (2016).

Tricklebank, K. A., Grace, R. V. & Pilditch, C. A. Decadal population dynamics of an intertidal bivalve (Austrovenus stutchburyi) bed: Pre-and post-a mass mortality event. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 55, 352–374 (2021).

Lam-Gordillo, O. et al. Climatic, oceanic, freshwater, and local environmental drivers of New Zealand estuarine macroinvertebrates. Mar. Environ. Res. 197, 106472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marenvres.2024.106472 (2024).

Fenton, K. F. et al. High densities of large tuaki, the New Zealand cockle Austrovenus stutchburyi, provide a post-settlement predation refuge for conspecific juveniles. Mar. Ecol. Progress Ser. 726, 85–98 (2024).

Marsden, I. D. & Adkins, S. C. Current status of cockle bed restoration in New Zealand. Aquacult. Int. 18, 83–97 (2010).

Yeoh, L. H., Thrush, S. F., Hewitt, J. E. & Gladstone-Gallagher, R. V. The effect of adult cockles, Austrovenus stutchburyi, on sediment transport. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 570, 151975 (2024).

Douglas, E. J., Lohrer, A. M. & Pilditch, C. A. Biodiversity breakpoints along stress gradients in estuaries and associated shifts in ecosystem interactions. Sci. Rep. 9, 17567. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54192-0 (2019).

Venter, L., Alfaro, A. C., Ragg, N. L., Delorme, N. J. & Ericson, J. A. The effect of simulated marine heatwaves on green-lipped mussels, Perna canaliculus: A near-natural experimental approach. J. Therm. Biol. 117, 103702 (2023).

Muznebin, F., Alfaro, A. C., Venter, L. & Young, T. Acute thermal stress and endotoxin exposure modulate metabolism and immunity in marine mussels (Perna canaliculus). J. Therm. Biol. 110, 103327 (2022).

Zhou, Z. et al. Temporal dynamics of heatwaves are key drivers of sediment mixing by bioturbators. Limnol. Oceanogr. 68, 1105–1116. https://doi.org/10.1002/lno.12332 (2023).

Zhou, Z. et al. Thermal stress affects bioturbators’ burrowing behavior: A mesocosm experiment on common cockles (Cerastoderma edule). Sci. Total Environ. 824, 153621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.153621 (2022).

Harrison, S. & Phizacklea, A. Vertical temperature gradients in muddy intertidal sediments in the Forth estuary, Scotland 1. Limnol. Oceanogr. 32, 954–963 (1987).

Harrison, S. J. & Phizacklea, A. P. Temperature fluctuation in muddy intertidal sediments, Forth Estuary, Scotland. Estuarine Coastal Shelf Sci. 24, 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7714(87)90070-9 (1987).

Hu, Z. et al. Effect of heat and hypoxia stress on mitochondrion and energy metabolism in the gill of hard clam. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 266, 109556 (2023).

Alfaro, A. C., Nguyen, T. V. & Mellow, D. A metabolomics approach to assess the effect of storage conditions on metabolic processes of New Zealand surf clam (Crassula aequilatera). Aquaculture 498, 315–321 (2019).

Ivanina, A. V. et al. Interactive effects of elevated temperature and CO2 levels on energy metabolism and biomineralization of marine bivalves Crassostrea virginica and Mercenaria mercenaria. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 166, 101–111 (2013).

Venter, L., Alfaro, A. C., Lindeque, J. Z. & Jansen van Rensburg, P. J. The metabolic fate of abalone: Transport and recovery of Haliotis iris gills as a case study. N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 8, 1–18 (2024).

Ben Rejeb, K., Abdelly, C. & Savouré, A. How reactive oxygen species and proline face stress together. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 80, 278–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.04.007 (2014).

Parra, M., Stahl, S. & Hellmann, H. Vitamin B6 and its role in cell metabolism and physiology. Cells 7, 84 (2018).

Lam-Gordillo, O. et al. Integrating rapid habitat mapping with community metrics and functional traits to assess estuarine ecological conditions: A New Zealand case study. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 206, 116717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2024.116717 (2024).

Drylie, T. P. Marine ecology state and trends in Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland to 2019. State of the environment reporting. Auckland Council technical report. TR2021/09 (2021).

Douglas, E. J. et al. Macrofaunal functional diversity provides resilience to nutrient enrichment in coastal sediments. Ecosystems 20, 1324–1336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-017-0113-4 (2017).

Smart, K. F., Aggio, R. B. M., Van Houtte, J. R. & Villas-Bôas, S. G. Analytical platform for metabolome analysis of microbial cells using methyl chloroformate derivatization followed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. Nat. Protoc. 5, 1709–1729. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2010.108 (2010).

Guo, G. et al. MassOmics: An R package of untargeted metabolomics Batch processing using the NIST Mass Spectral Library. https://htmlpreview.github.io/?https://github.com/MASHUOA/MassOmics/blob/master/README.html (2020).

Man, M. et al. Microclimate data handling and standardised analyses in R. Methods Ecol. Evol. 14, 2308–2320. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.14192 (2023).

R-Core-Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria., https://www.R-project.org/ (2022).

Kassambara, A. ggpubr: ‘ggplot2’ Based Publication Ready Plots. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggpubr (2020).

Anderson, M. J., Gorley, R. N. & Clarke, K. R. PERMANOVA+ for PRIMER: Guide to Software and statistical methods. Plymouth: PRIMER-E (2008).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Picart-Armada, S. et al. Null diffusion-based enrichment for metabolomics data. PLOS ONE 12, e0189012. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189012 (2017).

Picart-Armada, S., Fernández-Albert, F., Vinaixa, M., Yanes, O. & Perera-Lluna, A. FELLA: An R package to enrich metabolomics data. BMC Bioinf. 19, 538. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12859-018-2487-5 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Te Rūnanga o Ngāti Whakahemo and Professor Kura Paul-Burke (Waikato University) for inviting and warmly welcoming the NIWA team on to the Pukehina Marae and encouraging us to carry out the fieldwork and experimentation in Waihī estuary. The authors also thank Saras Green and Jin Wang the Mass Spectrometry Centre, The University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand for assistance with MFC analysis, data mining, and metabolite identification. We also thank the Marine Ecology team (NIWA) in Hamilton, New Zealand for the processing of sediment and macrobenthic samples and Stuart Mackay (NIWA) for taking the photographs used in figure 1d-e. This research was part of the Ecosystem Function and Health project and Ecosystem resilience and rehabilitation in a changing climate in NIWA’s Coasts & Estuaries Centre.

Funding

This research was funded by the New Zealand Government’s Strategic Science Investment Fund (SSIF) to the National Institute for Water & Atmospheric Research (NIWA; CEME2301/2401 and CEME2402/2502) NIWA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

OLG conceived the study and led data compilation, statistical analysis, and manuscript preparation. OLG, EJD, SFH, and AML conducted the fieldwork and experiment to generate the data. SFH, EJD, and VC contributed to manuscript preparation. AML conceived the study, provided statistical advice, and contributed to manuscript preparation and finalisation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lam-Gordillo, O., Douglas, E.J., Hailes, S.F. et al. Effects of in situ experimental warming on metabolic expression in a soft sediment bivalve. Sci Rep 15, 1812 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86310-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86310-6

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Simulated heatwave alters intertidal estuary greenhouse gas fluxes

Nature Communications (2025)