Abstract

Electro-tactile stimulation (ETS) can be a promising aid in augmenting sensation for those with sensory deficits. Although applications of ETS have been explored, the impact of ETS on the underlying strategies of neuromuscular coordination remains largely unexplored. We investigated how ETS, alone or in the presence of mechano-tactile environment change, modulated the electromyogram (EMG) of individual muscles during force control and how the stimulation modulated the attributes of intermuscular coordination, assessed by muscle synergy analysis, in human upper extremities. ETS was applied to either the thumb or middle fingertip which had greater contact with the handle, grasped by the participant, and supported a target force match. EMGs were recorded from 11 arm muscles of 15 healthy participants during three-dimensional exploratory force control. EMGs were modeled as the linear combination of muscle co-activation patterns (the composition of muscle synergies) and their activation profiles. Individual arm muscle activation changed depending on the ETS location on the finger. The composition of muscle synergies was conserved, but synergy activation coefficients altered reflecting the effects of electro-tactile modulation. The mechano-tactile modulation tended to decrease the effects of ETS on the individual muscle activation and synergy activation magnitude. This study provides insights into sensory augmentation and its impact on intermuscular coordination in the human upper extremity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sensory systems work harmoniously to provide us with the necessary information to execute motor tasks efficiently. Sensory inputs such as vision, somatosensory, and vestibular information provide feedback integral to motor control. This feedback allows for adjustment and fine-tuning of goal-oriented movements in response to changes in the internal and external environments1,2,3. Through ongoing streaming of information, sensory signals constantly update physiological status and external environmental information, allowing for proper guidance of neuromuscular system initiation and overall navigation of the surrounding environment4.

Sense of touch is considered part of sensory input, but it is highly under-appreciated5 as compared to vision and auditory information. The tactile system, equipped with over 10,000 receptors sensitive to 10-ms interruptions, can process a great deal of information when presented effectively6. Touch perception, particularly in our fingers and hands, plays a crucial role in effective communication, shaping our sense of self, and influencing our fundamental understanding of the world7. These tactile stimuli and the sensory neural dynamics integrated with our motor intentions and joint configurations8 allow for the execution and monitoring of active tactile manipulations9,10,11. Daily activities to interact with the external world are often taken for granted in individuals with intact sensory systems, without much consideration of how destructive a loss of sense of touch can be to our quality of life12. Often caused by nerve damage or amputation of limbs, a loss of touch in the fingers and hands can severely decrease manual dexterity and use of fine motor skills, loss of unconscious ability to communicate through body language, as well as the ability to sense limb movement and position, all of which can be mentally and physically damaging to the affected individual13,14. For individuals suffering from loss of tactile perception, electro-tactile stimulation is a promising approach to restore or substitute their missing sense of touch15.

Electro-tactile stimulation (ETS) is produced by applying electrical currents or voltage pulses to the skin surface, directly stimulating nerve fibers inside the skin16. Medically, ETS is better known for its use in prosthetics, restoring the sense of touch for patients in their missing arms or digits and allowing for greater grasp and control of prosthetics17,18. In rehabilitative applications, ETS was proven to improve shoulder abduction and flexion in patients with chronic stroke19. Applications of ETS also reach into the realm of sensory augmentation, such as enhancing cochlear implant speech recognition in noisy environments20 or improving proprioception and balance for peripheral neuropathic patients15. Although the concept has been explored for the past 40 years, ETS continues to be an area of interest for clinical applications, with its pros being that it is an inexpensive, noninvasive, and portable mode of stimulation that is already available for commercial use21.

While the applications and functional impacts of ETS have been studied, there is still a significant gap in our understanding of how it affects the underlying strategies of neuromuscular coordination and control. Multiple studies12,14 have demonstrated that ETS can effectively serve as a mode of aiding sensory substitution, augmentation, and restoration. However, there is a lack of comprehensive explanations for the underlying physiological mechanisms. To fully comprehend the role of ETS as a sensory augmentation tool and its ability to aid in improving and restoring different aspects of motor control, further investigation into its impacts on fundamental physiological signals is necessary. Using electromyography (EMG) signals can be a beneficial approach to exploring how ETS influences underlying neuromuscular control. Information at the individual muscle level can provide significant insights into the motor control system, and the changes in muscle activity may serve to quantify the impact of ETS. Studies examining changes at the EMG level during ETS for non-prosthetic applications are currently underdeveloped. Using EMG to study the effects of ETS allows for the observation of how different stimulation factors affect the human upper extremity at both the individual and neuromuscular coordination levels.

Muscle synergy analysis has been widely used to determine neuromuscular coordination and control strategies in humans. When studied in healthy participants, muscle synergies represent functional intermuscular coordination patterns used to reliably produce motor functions during natural motor behaviors22,23. Muscle synergies are collected by measuring EMG signals of multiple muscles during motor tasks. Afterward, muscle synergies can be identified from the EMG data through a variety of computational methods24, but most commonly, non-negative matrix factorization (NNMF) is considered the most conventional method to identify muscle synergies due to its neurophysiological data interpretability. Previous studies have observed the effects of various modes of sensory alterations, such as deafferentation25, noxious stimulation26, and mechanical environment compliancy27, on the muscle synergy structure of animals and humans. Also, one study modeled interactions of afferent neural dynamics on the efferent response of a biomimetic hand exerted by one muscle synergy throughout grasping dynamics28. However, there remains a need to further investigate the underlying mechanisms that allow for the alteration of synergy attributes in case changes to the sensory feedback system are introduced. Looking at both the individual muscle level and the intermuscular level can allow us to view the effects of ETS on both underlying neural strategies for movement and functional outcomes of muscle activation.

This study aimed to investigate how electro-tactile stimulation modulates the EMG activity of individual muscles under various motor task constraints and how the stimulation modulates the attributes of muscle synergies to meet the task constraints by coordinating multiple muscles in the human upper extremity. First, we hypothesized that electro- and/or mechano-tactile modulation on the finger induced changes in individual muscle activity in the arm during isometric force generation. Second, we hypothesized that electro- and/or mechano-tactile stimulation on the finger would significantly modulate the intermuscular coordination characteristics in the arm.To test the hypotheses, healthy individuals generated isometric forces by grasping the handle of a mechanical device, and EMG activation was recorded from key arm muscles. The study tested six experimental conditions during the force generation at the hand: the force target matching condition without any stimulation or padding (Control); providing electro-tactile stimulation on the finger whose force application on the handle would support or oppose force target matches defined as pro- or anti-target stimulation (PTS or ATS), in which PTS delivered stimulation to the finger requiring greater contact with the handle based on the target direction (the thumb was stimulated for the “Pushdown” target and the middle finger was stimulated for the “Pullup” target), while ATS delivered stimulation to the opposite finger for each respective target direction); mechanical padding (MP), introduced as a way to change the mechanical environment in a grasping posture to match target forces; and providing a combination of pro- or anti-target stimulation with mechanical padding (PTS + MP or ATS + MP). Muscle synergy analysis was performed to identify the attributes of muscle synergy vectors and their activation profiles for each of the six conditions.

Results

Modulation of arm muscle activation at the individual muscle level

The electro-tactile stimulation modulated the individual arm muscle activation depending on the task constraints during force generation. The EMG magnitude presented as the ratio of each muscle activation recorded in five experimental conditions, normalized by the control condition, recorded in a single representative participant during (a) Pushdown and (b) Pullup directional force generation. * indicates the statistical difference between a test condition and the control (Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, alpha = 0.05). The group analysis (n = 15) shows the percentage of the participants with the increase, decrease, mixed (some muscle activation increased and others decreased within the same participant), or no modulation cases of the muscle activation magnitude recorded at each of the five test conditions during (c) the Pushdown and (d) Pullup directional force generation. (Brachioradialis, BRD; biceps, BIm; triceps long and lateral heads, TRIlong and TRIlat; deltoids, anterior, middle, and posterior fibers; AD, MD, and PD; pectoralis, clavicular fibers, PECTclav; flexor digitorum superficialis, FDS; flexor pollicis longus, FPL; flexor digitorum profundus, FDP. PTS, pro-target stimulation; ATS, anti-target stimulation; MP, mechanical padding; PTS + MP, pro-target stimulation + mechanical padding; ATS + MP, anti-target stimulation + mechanical padding)

As compared to the control, the EMG magnitudes of the individual muscles in the five experimental conditions involving electro-tactile stimulations and mechanical padding were significantly modulated depending on the direction of the targeted force. For example, the EMG magnitude of BRD, BIm, MD, PECTclav, and FPL was modulated (Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test, *, p < 0.05) in a representative participant across different experimental conditions during the force generation in the Pushdown direction (Fig. 1a). In contrast, the activation magnitude of TRIlong, TRIlat, MD, PD, PECTclav, and FDP was affected (Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test, *, p < 0.05) across the experimental conditions during the force generation in the Pullup direction (Fig. 1b).

The five experimental conditions induced the statistically significant modulation (Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test, p < 0.05) of the EMG magnitude of one or more muscles in 80% of the participants, at least in both target directions (Fig. 1c and d). Though the electro-tactile stimulation or mechanical padding was applied in the same way across participants, the effects of the test conditions on the EMG magnitude seemed to vary among the participants, especially during the Pushdown force target matches. However, the EMG magnitude modulation still showed a trend depending on the stimulation location on the fingertip and the target force direction.

While the electro-tactile stimulation given on the thumb tended to decrease the muscle activation in the arm, the stimulation on the middle finger tended to increase the muscle activation regardless of the direction of force generation. For example, when the thumb was stimulated, the PTS, PTS + MP, and ATS + MP conditions to match the Pushdown force target (Fig. 1c) and the ATS condition to match the Pullup force target (Fig. 1d) induced a decrease in the EMG magnitude of one or multiple muscles in about 40, 50, and 60% of the participants, respectively. In contrast, when the middle finger was stimulated, the ATS condition to match the Pushdown force target (Fig. 1c) and the PTS and PTS + MP conditions to match the Pullup force target (Fig. 1d) induced an increase in the EMG magnitude of one or multiple muscles in about 55, 50, and 40% of the participants, respectively. Also, the middle finger required a smaller voltage (5.43 ± 0.41 V; n = 15) compared to the thumb voltage (5.81 ± 0.58 V; n = 15) to evoke about the same level of sensation, which indicates that the middle finger tended to be more sensitive during calibration than the thumb.

The pairing of the mechanical padding, inserted between the hand and the handle in the grasping posture, induced the modulation of the EMG magnitude in both force target matches. How the padding insertion affected the EMG magnitude depended on the direction of the target force. For the Pushdown force target match, all five experimental conditions including the padding condition decreased the EMG magnitude of muscles in the arm as follows: 40% of participants for PTS, 33% of participants for ATS, 40% of participants for MP, 46% of participants for PTS + MP, and 46% of participants for ATS + MP (Fig. 1c). In contrast, the mechanical padding tended to decrease the EMG magnitude of the arm during the Pullup force target match; the MP condition decreased the arm muscle activation in 53% of the participants during Pullup force generation (Fig. 1d). Also, when the padding was added to the electro-tactile stimulation on the middle finger (PTS + MP), the percentage of the decrease in EMG magnitude increased during the Pullup force generation, compared to the stimulation only (PTS). The effects of electrical tactile modulation tended to be similar to those of MP when the electrical stimulation was applied to the finger, as opposed to the target matching direction (ATS). For example, Fig. 1c shows that both ATS and MP induced the increase in the overall EMG magnitude in 60%, and 46% of participants respectively during the Pushdown force generation. Also, both ATS and MP decreased the EMG magnitude in 60%, and 53% of participants respectively during Pullup directional force production (Fig. 1d).

The effects of electro-tactile modulation were affected in the presence of MP, which resulted in a decrease in the EMG magnitude. Figure 1c shows that, during the Pushdown force generation, when PTS and MP were applied (PTS + MP), the percentage of the decrease in the EMG magnitude increased. Also, the percentage of the increase in the EMG magnitude decreased in the case of ATS + MP, compared to ATS only. Similarly, during Pullup directional force production, the PTS + MP condition induced a higher percentage of the EMG decrease among participants (Fig. 1d).

The composition of two muscle synergies underlying isometric force generation is conserved across five test conditions (n = 15; mean ± STD). The top plot shows the Pro-Pushdown muscle synergy with activation of the triceps long and lateral heads, middle and posterior deltoids, flexor digitorum superficialis, and flexor digitorum profundus. The bottom plot shows the Pro-Pullup muscle synergy with activation of brachioradialis, biceps, anterior and middle deltoids, pectoralis clavicular fibers, and flexor digitorum superficialis, flexor pollicis longus, and flexor digitorum profundus.

Conservation of the muscle synergy composition given electro-tactile stimulation

All participants across the control and test conditions required two muscle synergies to account for at least 90% of the total variance underlying isometric force generation. Figure 2 shows the average distribution of muscle weights of the two muscle synergies, per experimental condition across all participants (n = 15; mean ± STD). Each of the two synergies was named based on when the synergy was mainly activated to generate force. For example, the first muscle synergy, Pro-Pushdown synergy (W1), was mainly activated to match the Pushdown directional force target. This synergy included the activation of TRIlong, TRIlat, MD, PD, FDS, and FPS. In contrast, the second synergy, Pro-Pullup synergy (W2), was activated to generate the upward and forward directional force. This synergy was dominated by the activation of BRD, BIm, AD, MD, PCF, FDS, FPL, and FDP.

The composition of both synergies was similar across all control and experimental conditions regardless of how the model control synergy was computed. When the synergies of an individual, which underlay the control condition, were compared to the same participant’s synergies underlying the five test conditions, the lowest average similarity score of both muscle synergies was 0.94, while the highest was 0.97 (Table 1). Similarly, when the control synergies averaged across 15 participants were compared to all participants’ synergies, the lowest average score for both muscle synergies was 0.88, while the highest was 0.92 (Table 2), which were statistically significant (p < 0.05). All the values of the scalar product were higher than the statistical threshold of 0.76. Thus, the scalar products of the muscle synergy vectors across the five test conditions were considered statistically similar.

Electro-tactile stimulation, alone or paired with mechano-tactile input, modulates arm intermuscular coordination by altering the magnitude of muscle synergy activation profiles. (a) Modulation of pro-pushdown synergy (W1) activation during the Pushdown directional force generation. (b) Modulation of pro-pushdown synergy (W1) activation during the pullup directional force generation. (c) Modulation of pro-pullup synergy (W2) activation during the pushdown directional force generation. (d) Modulation of pro-pullup synergy (W2) activation during the pullup directional force generation. See the Fig. 1 legend for the full terms of the five test conditions.

Modulation of the muscle synergy activation given electro-tactile stimulation

While the composition of muscle synergies did not change across experimental conditions, the activation profiles of the synergies were altered to account for the modulation of muscle coordination in the arm (Fig. 3). However, the activation profile of the Pro-force directional synergy (the Pro-Pushdown synergy for the Pushdown task, and the Pro-Pullup synergy for the Pullup task) did not tend to change. For example, to match the Pushdown or Pullup force target, the activation profile of the Pro-Pushdown synergy (Fig. 3a) or Pro-Pullup synergy (Fig. 3d) did not change. In contrast, the activation profile of the Pro-Pushdown synergy was mainly modulated during the Pullup directional force generation, observed in greater than 60% of participants (Fig. 3b). Similarly, the activation profile of the Pro-Pullup synergy was mainly modulated during the Pushdown directional force generation, observed in greater than 50% of participants (Fig. 3c).

Also, Fig. 3 shows that the simultaneous application of electro-tactile modulation and mechanical padding tended to decrease the activation magnitude of muscle synergy regardless of force generation direction. During the Pullup directional force generation, the PTS + MP condition decreased the proportion of the participants who increased the Pro-Pushdown synergy (W1) activation magnitude, compared to PTS only (Fig. 3b). Also, the ATS + MP condition increased the subject percentage which decreased the W1 synergy activation magnitude, compared to ATS only. Similarly, during the Pushdown directional force generation, the PT.

S + MP condition increased the participant percentage which decreased the Pro-Pullup synergy (W2) magnitude (Fig. 3c). The ATS + MP condition also decreased the subject percentage which increased the magnitude of W2 synergy activation.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the influence of electro-tactile stimulation (ETS) on the finger, alone and alongside mechanical padding as a way to change the mechanical environment of motor performance, on individual arm muscle activation and intermuscular coordination, quantified by muscle synergy analysis, in healthy individuals. The overall magnitude of EMG activity in the arm significantly increased and decreased when the middle finger and thumb were stimulated, respectively, regardless of target force direction or the presence of the mechanical padding. The effects of electro-tactile modulation tended to be similar to those of mechanical padding when the electrical stimulation was applied to the finger in the opposite direction of the intended force generation. Also, the concurrent application of ETS (PTS or ATS) with mechanical padding (MP) as a means of mechano-tactile modulation weakened the effects of the ATS and PTS on the overall EMG magnitude regardless of target force direction. Moreover, muscle synergy analysis showed that the synergy composition remained conserved across all experimental conditions, while synergy activation magnitudes were modulated depending on the experimental condition. Furthermore, the presence of MP tended to decrease the effects of electro-tactile stimulation (PTS or ATS) on the synergy activation magnitude depending on the direction of the target force. Overall, the findings suggest that electro-tactile stimulation in the hand can modulate individual muscle activation and intermuscular coordination in the arm by changing the activation profile of muscle synergies but not the composition of the synergies.

Our findings support that the stimulation location can be an essential factor in the modulation of overall EMG activation when using ETS as a tactile modulation. Considering decreased EMG activity as a more efficient strategy to perform force generation in an intended direction, thumb stimulation tended to decrease muscle activity while the stimulation on the middle finger increased the magnitude of muscle activation. Moreover, we observed the higher sensitivity of voltage calibration for the middle finger compared to the thumb. Similar to our study, previous studies on the effect of electro-tactile stimulation location showed a significant change in postural balance efficiency by changing the stimulation location15,29. Although these studies imply the importance of stimulation location on postural balance efficiency, they didn’t identify neurophysiological mechanisms underlying such change in postural balance. Therefore, we acknowledge more research is needed to comprehensively interpret the correlation between the location of the neural stimulation and the neuromuscular control response30. Our results showed the importance of the location selection for electro-tactile stimulation in altering motor task performance in a desired way. Electro-tactile feedback can generally enhance somatosensory sensation throughout multi-joint motor tasks. It is noteworthy that the stimulation location can influence neuromuscular control due to the hypothesis that different biofeedback locations can be intrinsically involved in different sensorimotor loops31. Accordingly, caution might be considered when designing future neuro-rehabilitative frameworks involving somatosensory augmentation for different neuropathic populations such as those with peripheral neuropathy.

Our study showed that the effects of anti-target electro-tactile stimulation (ATS) and changing mechano-tactile environment (MP) on modulating the EMG activation magnitude could be similar regardless of the nature of the sensory modulation. For example, throughout the Pushdown force generation task, both ATS and MP increased the amplitude of EMG activity. Also, they decreased the EMG activation magnitude during the Pullup directional force production (Fig. 1c and d). However, the underlying neurophysiological mechanism remains unclear. Still, the observation that the effects of electro- and mechano-tactile modulation on neuromuscular control can be similar in a specific biomechanical condition can provide insight into designing new somatosensory augmentation paradigms.

Pairing MP with electro-tactile stimulation tended to increase the prevalence of the decrease in the overall EMG magnitude among participants, suggesting that the interaction between electro- and mechano-tactile modulations can enhance the efficiency of motor task completion. This observation was regardless of the electrical stimulation location on the finger. Previous studies showed the modulation of the EMG activation recorded during a stretch reflex in the human upper extremity in a mechanically compliant environment, although the EMG reflexes increased with the existence of perturbed compliant loads27,32. Our results did not conclusively show whether the EMG magnitude increased or decreased in the presence of mere mechano-tactile environment change. However, mechano-tactile modulation can be considered to have a dampening effect when implemented with ETS concurrently. In other words, mechano-tactile modulation alongside the ETS framework can be considered for designing more efficient motor task performance. Less muscle activation would be required to perform the same task throughout the combination of mechano- and electro-tactile modulations.

Our muscle synergy analysis indicates that synergy compositions remained conserved, while the activation profile of the synergies was modulated across all experimental conditions with varying tactile inputs in the hand. These results are congruent with the previous animal studies with somatosensory modulation by supporting the notion that the central nervous system requires somatosensory feedback to tune the modular organization of movement accurately33,34,35. For example, Cheung et al.34 compared muscle synergies observed in intact conditions and after sensory deafferentation in a frog model. Most muscle synergies were shared between the two conditions, but the amplitude and temporal patterns of the activation coefficients of muscle synergies were altered after the deafferentation. Similarly, the biomechanical simulation of frog hind limb movement showed how early proprioception might be used to implicitly plan a movement using spinally mediated muscle synergies33. Also, genetic manipulation to create muscle spindle-deficient mice induced impaired dynamic stability and alterations in the attributes of the modular organization of locomotion35. These results suggest that somatosensory input modulates the activation profiles of the centrally organized synergies36,37,38. Similarly, we infer that sensory augmentation using electro- and mechano-tactile modulation is involved in tuning the recruitment of modular patterns in neuromuscular control.

Some notable differences exist between the previous animal studies and our current human study. Our current study noninvasively applied electrical and mechanical tactile modulation in the hand during the performance of isometric force generation in the upper extremities of human participants. In contrast, the previous work in the animal models involved invasive procedures, such as the deafferentation of the lower extremity of bullfrogs by cutting the dorsal roots of the spinal cord34 or genetic manipulation to generate the absence of feedback from muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs in mice35. Thus, the extent to which changes in the attributes of muscle synergies can vary depending on the studies. Despite the significant differences in the study design, the same conclusion could be made from the current and previous studies: alterations in somatosensory input modulate the characteristics of the modular organization of movement orchestrated by the central nervous system.

We reason that nociceptive sensory modulation may re-organize the modular control of movement more dramatically than non-nociceptive, electro-, or mechano-tactile stimulation does. Previous human studies showed alterations of both synergy compositions and their activation profiles throughout pain-involving motor control during trunk movements25, upper extremity reaching39, and lower extremity gaits26. Also, a reduction in motor complexity was reported due to the recruitment of a smaller number of muscle synergies throughout grip-force generation for people with chronic elbow pain40. These studies pointed out that alteration or generation of subject-specific muscle synergies is considered a compensatory strategy exploited by participants to preserve baseline kinematics in the pain condition. However, our results on mechano- and electro-tactile modulation on force control induced the changes in the recruitment or activation of synergistic muscle activation patterns rather than the changes in the composition or number of synergies. The relatively mild changes in the modular organization of motor control can be due to the non-nociceptive and low-intensity nature of the tactile modulation we adopted in the study.

Our study provides insights into developing motor neurorehabilitation strategies using ETS by targeting neuromuscular coordination in people with motor deficits. Various studies have employed invasive electrical stimulation on the neurologically impaired population. These studies showed restoration in limb function after spinal cord injury both in the upper extremity of rat models41 and in the lower extremity gait of humans42. Also, previous studies of non-invasive sensory electrical stimulation in the human lower extremity after stroke43 showed improved gait and balance when rehabilitation was incorporated with the stimulation. The underlying neurophysiological mechanisms of the ETS-induced alterations are still unclear. Considering that stroke alters the attributes of muscle synergies (i.e., the number, composition, and/or activation profiles of muscle synergies) in the upper or lower extremity44,45,46,47, the ETS-induced positive changes can at least partly correlate with the modulation of the synergy attributes in neurological conditions. However, caution should be taken when designing ETS-based protocols. The ETS feedback of afferents can interfere with unrelated proprioceptive inputs transmitted from the CNS48. As a result, ETS-based rehabilitation should be designed to restore impaired intermuscular coordination while minimal unrelated proprioception is involved in the process.

One may wonder why the muscle weights of FPL in Pro-Pushdown synergy and FDP in Pro-Pullup synergy were relatively lower (Fig. 2), while the activation magnitudes of the FPL and FDP muscles were relatively high during the Pushdown (Fig. 1a) and Pullup (Fig. 1b) directional force generation, respectively. These inconsistencies stem from the fact that the EMG dataset was variance-normalized before applying NNMF to the EMG data to identify muscle synergies. The normalization procedure is useful and has been widely used in the literature because it prevents the synergy identification procedure from being biased toward muscles with large variance, such as FPL and FDP in the data.

ETS augmentation can potentially help new technologies in human movement augmentation. Movement augmentation is considered to augment the body such as the upper extremity with artificial limbs that can concurrently control or broaden the natural limb’s workspace49 (ref 1). One of the main challenges in the field is to design an optimum neural resource allocation for the extra robotic limb without hindering the biological limb coordinated motor control50 (ref 2). One study recruited neural allocation from muscle activations that do not generate task-relevant forces to control the extra degrees of freedom51 (ref 3). However, it has been shown that neural allocation from co-contracted muscles has limited control on the augmentation for generating a variety of movement reachings52 (ref 4). Also, sensory information can be considered as a neural allocation resource for controlling UE augmentations50 (ref 2). Therefore, recruiting the ETS framework can be a controlling signal for an extra limb or can modulate the activity of co-contracted muscles for the extra limb control based on muscular data.

The current study has a few limitations. As surface EMG electrodes were used, EMG crosstalk is more likely, especially for measuring activity from the finger flexor muscles. To minimize the risk of EMG crosstalk, we took extra precautions during the EMG electrode placement by observing the multi-channel EMG activities before any data collection to avoid any artificially similar EMG recording made across adjacent channels. Also, due to the limited number of force target locations tested in the study, our results cannot be generalized for the overall 3D force space. In order to draw more generalized conclusions related to the impact of directionality on ETS modulation of muscle activity, other directions need to be assessed in the same manner in a greater quantity and variety. Also, the age of participants ranged between 19 and 39. Thus, age-related variations in sensory response could not be properly addressed, although the variations are feasible. Observation of ETS application, specifically in older adults, may be interesting since sensory attenuation tends to increase with age53.

The current study provides insights into understanding the mechanisms underlying sensory-motor interaction for the modular organization of multi-joint force control in the human upper extremity. The muscle synergy analysis in the presence of electro-tactile modulation can delineate the influence of the sensory inflow on the intermuscular coordination in the upper extremities. Also, our results can provide insights into the influence of somatosensory feedback on neuromuscular coordination which can be used as a neural controller in musculoskeletal modeling and simulation because the typical musculoskeletal models do not include sensory feedback components. Recruiting somatosensory data alongside proprioceptive feedback may improve musculoskeletal models’ quality for better precision in such simulations54. Furthermore, designing neuro-rehabilitative frameworks needs sensorimotor feedback data to effectively reconstruct primary motor tasks such as force generation55. Future works can include importing somatosensory data to design synergy-controlling neural prosthetics56,57 which can exclusively shape practical models of intelligent rehabilitative frameworks.

Methods

Participants

Fifteen young and neurologically intact participants (age: 25.47 ± 5.28 years (mean ± STD), 19–39 years (range), eight males and seven females) were recruited for this study. The required criteria for participation included: (1) being in the age range of 18–40 years old, (2) being neurologically intact, and (3) being able to provide and understand informed consent before participating in the study. All participants were right-hand dominant except one participant. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardian(s). All experimental protocols were approved by the University of Houston institutional committee. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Houston STUDY00001333 and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

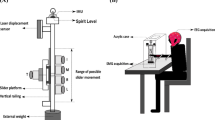

The experimental setup includes visual display of force targets, an ETS electrode configuration, and the handle with and without mechanical padding as mechano-tactile input. A participant grasps the handle, the end-effector of a robotic device, to match a target force, either a Pushdown or Pullup directional. Once a target match starts, one white ball (reflecting the participant’s force direction and magnitude) and one red ball (the target) appear on display to visually guide the isometric force target match. The target direction (red ball) is 180-degree visually flipped on a monitor to increase the cognitive load in the task performance. (a) When a Pushdown directional force target (represented as a red arrow) needs to be matched, the visual target (the red ball on display) is located in an upward and forward direction. (b) When a pullup directional force target needs to be matched, the red visual target on display is located in a downward and backward direction. (c) Electro-tactile stimulation electrode configuration. The electrode at the middle finger is where the stimulation is delivered, while the electrode at the wrist is its corresponding ground. The electrode at the thumb is another location of stimulation delivery, while the electrode at the palmar area is its corresponding ground electrode. (d) The handle used during the control, PTS, and ATS conditions (the handle circumference, 21.52 ± 0.45 cm). (e) The handle used during the MP, PTS + MP, and ATS + MP conditions including mechanical padding (7 mm of thickness) as mechano-tactile input (the handle circumference, 22.06 ± 0.50 cm).

Equipment

The KAIST upper limb synergy investigation system (KULSIS) is a robotic device that provides three-dimensional (3D) force and movement measurements for isometric force generation tasks in 3D space58. A display monitor was placed in front of the device that visually guided the participants’ isometric force-target matching tasks in experimental conditions (Fig. 4a and b).

The custom-designed electro-tactile stimulation device, created using Arduino boards59, provided voltage stimuli for the experiment. The device was attached to a power supply, a laptop containing the Arduino code, a terminal block, and commercially available self-adhesive electrodes (round, 32 mm diameter). The biphasic, square-shaped voltage stimulus was generated at 100 Hz with a 1-ms pulse width (20% duty cycle). The voltage amplitude was adjusted per participant and stimulation location during ETS calibration. The electro-tactile stimulus was delivered to one of the two stimulation locations per trial: the middle fingertip and the thumb of the non-dominant hand (Fig. 4c). The electrodes for the stimulation were placed in pairs: one active electrode and one ground electrode. The ground electrodes were placed at the wrist and the palmar thumb area for the middle finger and thumb, respectively. We determined the electrode configuration through trial and error, considering median nerve stimulation placement would evoke the most localized stimulation sensation.

Surface EMG signals (Delsys Trigno Sensors, Delsys, MA, USA) were recorded at 1 kHz from 11 different arm or finger muscles: brachioradialis (BRD); biceps (BIm); triceps, long and lateral heads (TRIlong and TRIlat); deltoids, anterior, middle, and posterior fibers (AD, MD, and PD); pectoralis, clavicular fibers (PECTclav); flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS); flexor pollicis longus (FPL); and flexor digitorum profundus (FDP). The electrodes were placed following the guidelines of the SENIAM protocol60 and the Anatomical Guide for the Electromyography61.

Experimental protocol

All motor tasks performed in the study were isometric; the arm remained stationary while a participant produced 3D force by grasping the handle, the end-effector of the robotic device (Fig. 4d and e). The handle was placed at 60% of his or her arm length from the acromion. The center of the handle was at the level of the participant’s acromion while the person sat on a chair. Participants used their non-dominant arms to perform the target matches. One of two targets was presented randomly during the experiment: one forward- and downward-directional and the other backward- and upward-directional. Both deviated from the horizontal plane by 45 degrees (one above and the other below) and were equidistant from the origin point. Once a new force target match started, one white ball (reflecting the participant’s force direction and magnitude) and one red ball (the target) appeared on display to visually guide the isometric force generation. The white ball displacement direction was visually flipped. For example, the participant should produce force to the right to move the ball left, upward to move the ball downward, etc. We intended to flip the movement direction of the visual guidance and used the non-dominant arm in the task performance to increase the task’s cognitive load. The rationale behind this was based on the previous study of Azbell et al.15 that showed that the more cognitively challenging the task is, the more influential the ETS would be in its role as a sensory augmentation tool. Participants were instructed to move the white ball (generating the end-point force) to match the target as closely as possible (15% logical radius of the target applied) and as soon as possible. The target match was made by moving the white ball into the 15% logical radius of the target ball and maintaining the target match for 1 s. The time limit of a single attempt for a successful target match was 14 s, including a one-second target matching hold period.

Before starting any data collection, the EMG electrodes were placed onto the 11 previously listed muscles on the participant’s non-dominant arm and the maximum lateral force (MLF) was measured to optimize the targeted force level for each participant. All participants used a non-dominant arm to perform motor tasks to increase the challenge of the task, which might increase the probability of recording the effects of electro-tactile stimulation12. The MLF of the non-dominant arm was collected three times, with 45 s of rest time in between each repetition, for normalization purposes. Afterward, two pairs of stimulation pads were placed on the participant’s non-dominant hand, at the tip of the thumb and middle fingers for stimulation and then at the palmer thumb area and wrist for the grounds, respectively, to prepare for stimulation calibration. Starting at 5.0 V for each finger location, the participant completed practice rounds of target matching, verbally confirming that they sensed electro-tactile stimulation on a specific finger once the user ball entered the 10% logical radius region on display. They also rated the sensation on a scale from 1 to 5, with 1 being very minimal sensation and 5 being extremely uncomfortable and nearly painful. The voltage for each finger was increased by 0.5 V until the participant confirmed that both stimulation locations were at a sensation level of 3.

Experimental conditions. Human participants performed motor tasks in six experimental conditions, including one control and five test conditions. The five test conditions are (1) pro-target stimulation (PTS), (2) anti-target stimulation (ATS), (3) mechanical padding (MP), (4) pro-target stimulation plus mechanical padding (PTS + MP), and (5) Anti-target stimulation plus mechanical padding (ATS + MP). (a) A chart showing stimulation location and force direction required for target matching in the conditions involving PTS and ATS. In the PTS-involving conditions, electro-tactile stimulation was delivered to the finger requiring greater contact with the handle based on the force target direction (i.e., the thumb was stimulated for the “Pushdown” target and the middle finger was stimulated for the “Pullup” target). In contrast, the ATS condition referred to the stimulation delivered to the opposite finger for each respective target direction (i.e., the thumb was stimulated for the “Pullup” target, and the middle finger was stimulated for the “Pushdown” target). (b) The combination of mechanical padding conditions (presence or absence) and electro-tactile stimulation conditions (presence or absence) created the six experimental conditions.

After MLF measurement and calibration of the stimulation were completed, the experimental task began. There were six different conditions (Fig. 5) in which the participant completed the target matching tasks: (1) Control, (2) Pro-Target Stimulation (PTS), (3) Anti-Target Stimulation (ATS), (4) Mechanical Padding (MP), (5) Pro-Target Stimulation plus Mechanical Padding (PTS + MP), and (6) Anti-Target Stimulation plus Mechanical Padding (ATS + MP). During the Mechanical Padding conditions (mechano-tactile input), commercially available slimes (Crystal Clear Slime Bucket, Aplus Toys Co., Ltd.) were evenly distributed (6 mm in thickness) in a plastic Ziploc bag and wrapped around the KULSIS handle once with ACE bandages, acting as a way to introduce a change in the mechanical environment for performing isometric force target matches (Fig. 4e). During the Pro-Target Stimulation condition, the location of stimulation delivery depended on which fingers required greater contact with the handle based on the target directions: the thumb was stimulated for the “Pushdown” force target match, and the middle finger was stimulated for the “Pullup” target. For the Anti-Target Stimulation condition, the other finger was stimulated for each target direction, respectively. The stimulation was delivered during the last 1-second hold period of the target matching task while the target match was maintained. Seven repetitions of each target direction were collected during each condition block. Three minutes of rest time were given in between conditions to minimize fatigue. The six experimental conditions were pseudo-randomly provided across participants. Also, the target directions per experimental condition were randomized.

Data analysis

All data analysis was executed using MATLAB. EMG processing included the following steps: the wavelet-based removal of ECG components, a DC component removal, rectifying EMG signals, the mean baseline removal, replacing negative values with zero, and filter application. A fourth-order Butterworth low pass filter (cutoff frequency, 10 Hz) was applied to extract the EMG envelope62. The last 1-second hold period of the target matches was represented as the 1000 data points of each trial. After filter characteristics were applied to this data, it was interpolated into 150 data points per trial. Then, the data were ordered according to the target location and concatenated for further synergy analysis. The EMG underlying the MLF trials underwent the same filtering, interpolating, and ordering process.

The maximum EMG value per muscle underlying the MLF trials and experimental trials was used to normalize the EMG magnitudes of any experimental condition. The data collected without mechano- and electro-tactile modulation were considered the control condition. The EMG data were normalized by their maximum value per muscle, but to be considered an activated muscle, the muscle activity during the participant’s control condition should be at least 20% of the most activated muscle. Further, the difference between the overall averaged EMG magnitudes of the control versus the experimental conditions was evaluated per muscle, determining the direction of the change of the modulation.

Muscle synergy analysis

Non-negative matrix factorization (NNMF) was applied to the EMG data space of each of the six experimental conditions to identify muscle synergies underlying the EMG data63. The NNMF is a feasible method for identifying non-negative features (i.e., synergy compositions) that are neurophysiologically meaningful and interpretable24. Also, NNMF does not constraint synergy compositions to be orthogonal, unlike other data reduction methods such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA). In NNMF, each non-orthogonal muscle synergy activation can be analyzed independently. In contrast, in PCA, muscle synergy components cancel each other out throughout the synergy extraction procedure, and therefore, final patterns are dependent on the activity of other synergies64. The EMG data underlying all target matching trials were concatenated and unit-variance-normalized throughout the NNMF implementation. Such variance normalization would prevent the outputted synergies from being biased toward muscles with high variance in a muscle synergy analysis45,47,65. Accordingly, the NNMF decomposes the primary EMG data matrix into synergy composition vectors (W) and synergy activation profiles of each of the muscle synergy compositions (C) as shown by Eq. 1.

To estimate the minimum number of muscle synergies for each motor task or condition, we calculated the variance accounted for (VAF) of the signal given the number of muscle synergies that consecutively increased from one to 11. Equation 2 shows the formulation of the VAF value, where SSE represents the sum of the squared residuals, and SST is the sum of the squared EMG data46. The main criteria in determining the appropriate number of synergies were that the number of synergies required to reconstruct the original EMG data had to have a mean global variance accounted for greater than 90%66.

We calculated similarity scores of a pair of muscle synergy vectors in comparison by computing their scalar product to compare the control synergy compositions to those of the other five experimental conditions within a single participant’s data (intra-subject variability). To assess the inter-subject variability in the synergy compositions, we computed the mean of the muscle synergies underlying control conditions of all 15 participants. We represented it as a unit vector to form a norm or representative synergy set. Then, the norm synergy set was compared to the synergies of the five experimental conditions of each participant.

Statistical analyses

The normalized EMG magnitude of each muscle recorded from a representative participant was measured in the five test conditions, PTS, ATS, MP, PTS + MP, and ATS + MP, compared with the control condition. The Kolmogrov-Smirnov test was used to test the normality of data distribution. Due to the non-normal data distribution, non-parametric tests were selected to compare the five conditions with the control. The two-sided Wilcoxon Rank Sum test was used to compare five conditions and the control to determine if their difference was significant. The scope of the work focused on understanding the neuromuscular modulation under each of the five different test conditions compared to the control. Therefore, a meaningful neurophysiological interpretation of each test condition compared to the control was performed rather than comparing the five test conditions to themselves. A significance level of 0.05 was set for all analyses.

To test the significance of the similarity of a pair of muscle synergies in comparison, we generated 1000 random synergies using the MATLAB built-in function, rand. Then, the scalar products of all possible pairs (499500 pairs) of the random synergies were calculated and ordered. The 95th percentile of the computed scalar products was deemed as the similarity threshold (0.76). Therefore, a pair of synergy vectors in comparison was considered statistically similar if their computed scalar product exceeded the similarity threshold46,66.

Data availability

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Johansson, R. S. & Cole, K. J. Sensory-motor coordination during manipulative actions. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2–815 (1992).

Riemann, B. L. & Lephart, S. M. The sensorimotor system, part II: The role of proprioception in motor control and functional joint stability. J. Athl. Train. 37, 80–84 (2002).

Scheidt, R. A., Conditt, M. A., Secco, E. L. & Mussa-Ivaldi, F. A. Interaction of visual and proprioceptive feedback during adaptation of human reaching movements. J. Neurophysiol. 93, 3200–3213 (2005).

Chen, X. et al. Therapeutic effects of sensory input training on motor function rehabilitation after stroke.https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000013387 (2018).

Zhou, Z. et al. Electrotactile perception properties and its applications: A review. IEEE Trans. Haptics 15, 464–478 (2022).

Kaczmarek, K. A., Webster, J. G., Bach-y-Rita, P. & Tompkins, W. J. Electrotactile and vibrotactile displays for sensory substitution systems. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 38, (1991).

Tan, D. W. et al. A neural interface provides long-term stable natural touch perception. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, (2014).

Wei, Y., Zou, Z., Qian, Z., Ren, L. & Wei, G. Biomechanical analysis of the effect of finger joint configuration on hand grasping performance: Rigid vs flexible. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 31, 606–619 (2022).

Ackerley, R. & Kavounoudias, A. The role of tactile afference in shaping motor behaviour and implications for prosthetic innovation. Neuropsychologia 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.06.024 (2015).

Wei, Y., Zou, Z., Wei, G., Ren, L. & Qian, Z. Subject-specific finite element modelling of the human hand complex: Muscle-driven simulations and experimental validation. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 48, 1181–1195 (2020).

Wei, Y. et al. From skin mechanics to tactile neural coding: Predicting afferent neural dynamics during active touch and perception. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 69, 3748–3759 (2022).

Zhao, Z., Yeo, M., Manoharan, S., Ryu, S. C. & Park, H. Electrically-evoked proximity sensation can enhance fine finger control in telerobotic pinch. Sci. Rep. 10, 163 (2020).

Robles-De-La-Torre, G. Haptic user interfaces for multimedia systems the importance of the sense of touch in virtual and real environments. (2006).

Meyer, S., Karttunen, A. H., Thijs, V., Feys, H. & Verheyden, G. How do somatosensory deficits in the arm and hand relate to upper limb impairment, activity, and participation problems after stroke? A systematic review. Phys. Ther. 94, 1220–1231 (2014).

Azbell, J., Park, J., Chang, S. H., Engelen, M. P. K. G. & Park, H. Plantar or palmar tactile augmentation improves lateral postural balance with significant influence from cognitive load. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 29, 113–122 (2021).

Saunders, F. A. Information transmission across the skin: high-resolution tactile sensory aids for the deaf and the blind. Int. J. Neurosci. 19, (1983).

Davis, T. S. et al. Restoring motor control and sensory feedback in people with upper extremity amputations using arrays of 96 microelectrodes implanted in the median and ulnar nerves. J. Neural Eng. 13, (2016).

Choi, K., Kim, P., Kim, K. S. & Kim, S. Two-Channel Electrotactile Stimulation for Sensory Feedback of Fingers of Prosthesis. (IEEE/RSJ International Conference, 2016).

Lam, P. et al. A haptic-robotic platform for upper-limb reaching stroke therapy: preliminary design and evaluation results. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 5, (2008).

Huang, J., Sheffield, B., Lin, P. & Zeng, F. G. Electro-tactile stimulation enhances cochlear implant speech recognition in noise. Sci. Rep. 7, (2017).

Malešević, J. et al. Electrotactile communication via matrix electrode placed on the torso using fast calibration, and static vs. Dyn. Encoding Sens. 22, (2022).

Safavynia, S., Torres-Oviedo, G. & Ting, L. Muscle synergies: Implications for clinical evaluation and rehabilitation of movement. Top. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabil. 17, 16–24 (2011).

Roh, J., Lee, S. W. & Wilger, K. D. Modular organization of exploratory force development under isometric conditions in the human arm. J. Mot. Behav. 51, 83–99 (2019).

Tresch, M. C., Cheung, V. C. K. & D’Avella, A. Matrix factorization algorithms for the identification of muscle synergies: Evaluation on simulated and experimental data sets. J. Neurophysiol. 95, 2199–2212 (2006).

Gizzi, L., Muceli, S., Petzke, F. & Falla, D. Experimental muscle pain impairs the synergistic modular control of neck muscles. PloS One 10, 0137844 (2015).

Den Hoorn, W., Hodges, P. W., Dieën, J. H. & Hug, F. Effect of acute noxious stimulation to the leg or back on muscle synergies during walking. J. Neurophysiol. 113, 244–254 (2015).

Perreault, E. J., Chen, K., Trumbower, R. D. & Lewis, G. Interactions with compliant loads alter stretch reflex gains but not intermuscular coordination. J. Neurophysiol. 99, 2101–2113 (2008).

Wei, Y. et al. Human tactile sensing and sensorimotor mechanism: From afferent tactile signals to efferent motor control. Nat. Commun. 15, 6857 (2024).

Zehr, E. P. et al. Cutaneous stimulation of discrete regions of the sole during locomotion produces sensory steering of the foot. BMC Sports Sci. Med. Rehabil. 6, 1–21 (2014).

Bao, X. et al. Electrode placement on the forearm for selective stimulation of finger extension/flexion. PloS One 13, e0190936 (2018).

Sienko, K. H., Balkwill, M. D., Oddsson, L. & Wall, C. Effects of multi-directional vibrotactile feedback on vestibular-deficient postural performance during continuous multi-directional support surface perturbations. J. Vestib. Res. 18, 273–285 (2008).

Krutky, M. A., Ravichandran, V. J., Trumbower, R. D. & Perreault, E. J. Interactions between limb and environmental mechanics influence stretch reflex sensitivity in the human arm. J. Neurophysiol. 103, 429–440 (2010).

Kargo, W. J., Ramakrishnan, A., Hart, C. B., Rome, L. C. & Giszter, S. F. A simple experimentally based model using proprioceptive regulation of motor primitives captures adjusted trajectory formation in spinal frogs. J. Neurophysiol. 103, 573–590 (2010).

Cheung, V. C. K., D’Avella, A., Tresch, M. C. & Bizzi, E. Central and sensory contributions to the activation and organization of muscle synergies during natural motor behaviors. J. Neurosci. 25, 6419–6434 (2005).

Santuz, A. et al. Modular organization of murine locomotor pattern in the presence and absence of sensory feedback from muscle spindles. J. Physiol. 597, 3147–3165 (2019).

Rana, M., Yani, M. S., Asavasopon, S., Fisher, B. E. & Kutch, J. J. Brain connectivity associated with muscle synergies in humans. J. Neurosci. 35, 14708–14716 (2015).

Pirondini, E. et al. EEG topographies provide subject-specific correlates of motor control. Sci. Rep. 7, 13229 (2017).

McMorland, A. J., Runnalls, K. D. & Byblow, W. D. A neuroanatomical framework for upper limb synergies after stroke. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 82 (2015).

Muceli, S., Falla, D. & Farina, D. Reorganization of muscle synergies during multidirectional reaching in the horizontal plane with experimental muscle pain. J. Neurophysiol. 111, 1615–1630 (2014).

Manickaraj, N., Bisset, L. M., Devanaboyina, V. S. & Kavanagh, J. J. Chronic pain alters spatiotemporal activation patterns of forearm muscle synergies during the development of grip force. J. Neurophysiol. 118, 2132–2141 (2017).

Ganzer, P. D. et al. Closed-loop neuromodulation restores network connectivity and motor control after spinal cord injury. Elife 7, e32058 (2018).

Wagner, F. B. et al. Targeted neurotechnology restores walking in humans with spinal cord injury. Nature 563, 65–71 (2018).

Sharififar, S., Shuster, J. J. & Bishop, M. D. Adding electrical stimulation during standard rehabilitation after stroke to improve motor function. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 61, 339–344 (2018).

Clark, D. J., Ting, L. H., Zajac, F. E., Neptune, R. R. & Kautz, S. A. Merging of healthy motor modules predicts reduced locomotor performance and muscle coordination complexity post-stroke. J. Neurophysiol. 103, 844–857 (2010).

Cheung, V. C. et al. Muscle synergy patterns as physiological markers of motor cortical damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 14652–14656 (2012).

Roh, J., Rymer, W. Z., Perreault, E. J., Yoo, S. B. & Beer, R. F. Alterations in upper limb muscle synergy structure in chronic stroke survivors. J. Neurophysiol. 109, 768–781 (2013).

Roh, J., Rymer, W. Z. & Beer, R. F. Evidence for altered upper extremity muscle synergies in chronic stroke survivors with mild and moderate impairment. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 124339 (2015).

Secerovic, N. K. et al. Neural population dynamics reveals disruption of spinal circuits’ responses to proprioceptive input during electrical stimulation of sensory afferents. Cell. Rep. 43, (2024).

Eden, J. et al. Principles of human movement augmentation and the challenges in making it a reality. Nat. Commun. 13, 1345 (2022).

Dominijanni, G. et al. The neural resource allocation problem when enhancing human bodies with extra robotic limbs. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 850–860 (2021).

Gurgone, S. et al. Simultaneous control of natural and extra degrees of freedom by isometric force and electromyographic activity in the muscle-to-force null space. J. Neural Eng. 19, 016004 (2022).

Lee, M. J. et al. Control limitations in the null-space of the wrist muscle system. Sci. Rep. 14, 20634 (2024).

Parthasharathy, M., Mantini, D. & Orban De Xivry, J.-J. Increased upper-limb sensory attenuation with age. J. Neurophysiol. 127, 474–492 (2022).

Zhang, H., Mo, F., Wang, L., Behr, M. & Arnoux, P. J. A framework of a lower limb musculoskeletal model with implemented natural proprioceptive feedback and its progressive evaluation. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 28, 1866–1875 (2020).

Clemente, F. et al. Intraneural sensory feedback restores grip force control and motor coordination while using a prosthetic hand. J. Neural Eng. 16, 026034 (2019).

Cole, N. M. & Ajiboye, A. B. Muscle synergies for predicting non-isometric complex hand function for commanding FES neuroprosthetic hand systems. J. Neural Eng. 16, 056018 (2019).

Hong, Y. N. G., Ballekere, A. N., Fregly, B. J. & Roh, J. Are muscle synergies useful for stroke rehabilitation? Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 19, 100315 (2021).

Park, J. H. et al. Design and evaluation of a novel experimental setup for upper limb intermuscular coordination studies. Front. Neurorobotics 13, (2019).

Manoharan, S. & Park, H. Characterization of perception by transcutaneous electrical stimulation in terms of tingling intensity and temporal dynamics. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 14, (2024).

Hermens, H. J. et al. European recommendations for surface electromyography results of the SENIAM project. Roessingh Res. Dev. 8, (1999).

Perotto, A. & Delagi, E. F. Anatomical Guide for the Electromyographer: The Limbs and Trunk. (Charles C. Thomas, Springfield, Ill, 2011).

Rose, W. Electromyogram analysis. (2011).

Lee, D. D. & Seung, H. S. Learning the parts of objects by non-negative Matrix Factorization. Lett. Nat. 401, (1999).

Ting, L. H. & Macpherson, J. M. A limited set of muscle synergies for force control during a postural task. J. Neurophysiol. 93, 609–613 (2005).

Roh, J., Rymer, W. Z. & Beer, R. F. Robustness of muscle synergies underlying three-dimensional force generation at the hand in healthy humans. J. Neurophysiol. 107, 2123–2142 (2012).

Seo, G. et al. Alterations in motor modules and their contribution to limitations in force control in the upper extremity after stroke. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 16, 937391 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank Amena Jangda and Stefan Manoharan for initially designing the data collection procedure and electro-tactile stimulation device, respectively.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This study was supported by the NSF CAREER Award (2145321 to Roh).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.D., G.S., H.P., and J.R. conceptualized and designed the study. H.S.P. developed the KULSIS robotic framework, and H.P. designed and prepared electro-tactile stimulation equipment. H.D., S.T., G.S., H.P., and J.R. designed the experimental protocol. H.D. and S.T. collected the experimental data. H.D., S.T., and J.R. analyzed experimental data and performed muscle synergy analysis. H.D., S.T., and J.R. wrote the manuscript. H.D., S.T., G.S., H.S.P., H.P., and J.R. edited and reviewed the original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Doan, H., Tavasoli, S., Seo, G. et al. Electro-tactile modulation of muscle activation and intermuscular coordination in the human upper extremity. Sci Rep 15, 2559 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86342-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86342-y