Abstract

This paper presents an all-optical 4 × 2 encoder based on graphene-plasmonic waveguides for operation in the wavelength range of 8–12 μm. The basic plasmonic waveguide consists of a silicon (Si) strip and a graphene sheet supported by two dielectric ridges. Surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) are stimulated in the spatial gap between the graphene sheet and the Si strip. The effect of geometric parameters and chemical potential of the graphene sheet changes on the suggested waveguide’s waveguiding behavior is meticulously investigated using the three-dimensional finite-difference time-domain (3D-FDTD) method. The encoder comprises a straight waveguide to detect the state of the In0 input and two Y-combiners with outputs Out0 and Out1 to detect the state of the In1, In2, and In3 inputs. The encoder exhibits a minimum extinction ratio (ERmin) of 19 dB at a wavelength of 10 μm. In addition, the cross-talk (CT) and insertion loss (IL) values are −21.3 and −1.31 dB, respectively. The encoder offers an ultra-compact structure with a total footprint of 4.25 μm2. Due to its exceptional waveguiding features, low CT and IL values, and high ERmin, the proposed encoder holds promise for various communication and signal processing applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plasmonic devices are specialized structures capable of trapping light within subwavelength regions, significantly reducing the size of the overall structure1,2,3. These devices are adept at generating surface plasmon polaritons (SPPs) at the interface between metal and dielectric materials, facilitating their propagation along this boundary. However, within the materials themselves, the electromagnetic field attenuates severely4,5,6. The term “polariton” denotes the oscillation of the metal’s bound electrons in conjunction with the excitation of photons. In this scenario, photons are responsible for the excitation of surface plasmons, leading to the use of “plasmon polariton” to describe the interaction between a photon and a plasmon7. Noble metals such as gold (Au) and silver (Ag) are typically employed as plasmonic materials in the visible and near-infrared (NIR) spectrum to generate SPPs. However, these materials are not suitable for mid-infrared (MIR) to terahertz (THz) frequencies due to their high losses8,9,10. The introduction of graphene has revolutionized the fields of electronics and photonics. Graphene is distinguished by its remarkable electrical and optical characteristics, paving the way for its incorporation into various optoelectronic devices10,11. It is characterized by its ability to confine light in areas smaller than the stimulating wavelength, minimal losses, and a refractive index that can be adjusted through chemical doping or external voltage12,13. Graphene’s unique blend of optical and electrical properties renders it an exemplary material for optoelectronic applications. Plasmonic waveguides can be generally classified into four main categories: metal-insulator (MIM)14, insulator-metal-insulator (IMI)15, hybrid plasmonic16, and graphene-based plasmonic waveguides17, each category being suited for special wavelengths and applications.

Encoders are one of the most well-known digital devices in telecommunications and signal processing systems. An encoder has 2n inputs and n outputs, and only one of the inputs can be in the logical state “1” at any time. Optical encoders have been reported based on various structures, such as photonic crystals (PhCs)18,19, plasmonics20,21, and other schemes22,23,24. Moniem proposed a 4 × 2 optical encoder based on two-dimensional PhCs with a switching speed of 500 GHz and a total footprint of 1225 μm225. Abdulwahid et al. reported a 4 × 2 optical encoder using hybrid plasmonic waveguides26. It operates at the wavelength of 1310 nm with a maximum transmission value of 68.4%, a transmission threshold of 30%, and a footprint of 0.368 μm2. However, it requires two extra input control signals to function correctly. Haddadan and Soroosh designed a plasmonic priority encoder using graphene nanoribbons27. The encoder exhibits a contrast ratio of 13.1 dB and a cross-talk of −16.22 dB with a whole area of 1.92 μm2, operating at a wavelength of 7 μm. However, this encoder requires six graphene nanoribbons with different chemical potentials. As a result, the lack of designing an encoder with acceptable characteristics, minimum input signals, and a straightforward fabrication process is felt. In this paper, we design a 4 × 2 optical encoder based on suspended graphene plasmonic waveguides operating in the wavelength range of 8 to 12 μm. The performance of the proposed encoder is analyzed using the three-dimensional finite-difference time-domain (3D-FDTD) method.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: The basic suspended graphene plasmonic waveguide is presented in Section “The basic suspended graphene plasmonic waveguide”. In this section, the effects of the geometrical parameters and chemical potential of graphene on the properties of the waveguide are investigated. The encoder structure and simulation results obtained by the 3D FDTD method are presented in Section “Proposed 4×2 plasmonic encoder”. Finally, the conclusion is expressed in Section “Conclusion”.

The basic suspended graphene plasmonic waveguide

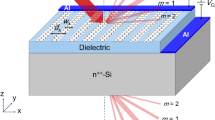

Figure 1a shows schematically the proposed basic plasmonic waveguide. It consists of an Au layer on a dielectric substrate, a thin silicon (Si) spacer layer, a Si strip at the center of the waveguide, and a graphene sheet supported by two dielectric ridges. As seen in Fig. 1b, the geometric parameters are the gap between the graphene sheet and the Si spacer layer (h), which includes a gap between the graphene sheet and the Si strip, and the height of the Si strip (h1), the width of the Si strip (h2), the height of the Si spacer layer (h3), and the distance of the dielectric ridges to the Si strip (d). The parameter d is chosen large enough that the existence of the dielectric ridges does not affect the propagation mode of the waveguide. In Fig. 1c, the possible fabrication processes of the suggested waveguide are plotted. The steps can be as follows: (i) deposition of the Au layer on the dielectric substrate via thermal atomic layer deposition and sputtering methods28,29, (ii) deposition of Si and patterning it to for the spacer layer and the strip using e-beam lithography30,31, (iii) deposition of the SiO2 layer using plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD)32,33, (iv) transfer of the CVD graphene grown on copper onto the SiO2 layer by employing the wet transfer method34, and (v) selective etching of the middle part of the SiO2 layer by dipping the entire device into 1:6 buffered oxide etch (BOE), which uniformly removes SiO2 across the substrate, including the area below the graphene sheet35. The fabrication process of the proposed suspended graphene-based waveguide and its experimental results have been detailed in Ref.35.

The other affecting parameter is the chemical potential (μc) of the graphene sheet. Applying chemical doping and an electrostatic field varies the chemical potential of graphene by changing the number of charge carriers, as follows36:

where ħ is the reduced Planck’s constant, vF = 106 m/s is the Fermi velocity, and \(f\left( E \right) = \left\{ {1 + \exp \left[ {\left( {E - \mu_{c} } \right)/k_{B} T} \right]} \right\}^{ - 1}\) is the Fermi distribution function, kB is the Boltzmann’s constant, and T is temperature. The complex permittivity of graphene (εg) is expressed in terms of the background relative permittivity (εr), surface conductivity of graphene (σg), free space (ε0) permittivity, operation angular frequency (ω), and graphene thickness (Δ) as follows37:

The surface conductivity of graphene defined by the Kubo formula consists of two parts, inter-band (σg-inter) and intra-band (σg-intra), calculated by the following equations17:

Here, e is the electron charge, and τ donates the relaxation time, which in the wavelength range of MIR to THz is expressed by38:

where Г and μm are the scattering rate and graphene mobility, respectively. The mobility of carriers in graphene can be changed from 1000 cm2/V.s when manufactured through CVD to 230000 cm2/V.s for suspended and exfoliated graphene35. As mentioned, altering the carrier density in graphene through chemical doping or applying an external voltage can also modify its chemical potential, affecting its conductivity. The relationship between the chemical potential of graphene and the external voltage (Vext) is as follows39,40:

where n0 is the intrinsic carrier concentration of graphene and Cp is the capacitance in F/m2, corresponding to the capacitor formed by the suspended graphene sheet, the Au metal, and the dielectrics between them. As demonstrated in Fig. 1b, the alteration of external voltage results in a corresponding change in the charge stored within the capacitor. This fluctuation in charge carriers directly influences the chemical potential of graphene, subsequently modifying its surface conductivity. Consequently, this leads to a variation in the permittivity of graphene, which in turn affects the effective refractive index and the overall optical characteristics of the structure. Thus, it can be deduced that the performance of the device can be effectively controlled through the application of an external voltage between the graphene sheet and the metal layer.

In our simulations, we model Si and Au materials using the Palik41 and CRC42 models, respectively. To simulate the waveguide, we used the commercial software Ansys Lumerical and the 3D-FDTD method43. This software offers a comprehensive set of tools for simulating complex photonic devices. Additionally, we set perfectly matched layers in all directions as boundary conditions to prevent light reflection towards the encoder. We also utilized a local fine mesh surrounding the graphene sheet to achieve accurate results.

In the following, the effects of geometric parameters on the features of the basic waveguide are studied. Figure 2 shows the distribution of the magnitude of the electric field |E| for the fundamental transverse magnetic (TM) mode as a function of the Si strip width in the z-y plane at λ = 10 μm. The width changes from 70 to 130 nm with steps of 10 nm. The parameters h, h1, h2, h3, and μc are 100, 20, 80, 20 nm, and 0.6 eV, respectively. The field intensity increases at the center of the stimulated mode as the width increases. Additionally, the waveguide acts as a single-mode waveguide with a width of 120 nm in the wavelength range of 8 μm to 12 μm. For w = 130 nm, the second-order mode is also excited at λ = 8 μm. Therefore, the waveguide is single-mode for w = 120 in the wavelength range of 8–12 μm.

The graphs in Fig. 3a demonstrate the real and imaginary parts of the effective refractive index (neff) of the fundamental mode for w variations. The real part is more sensitive to changes in the w parameter than the imaginary part. Using linear approximation, the rate of change of the real part to w is d[Re(neff)]/dw = 3.776 × 10−2 nm−1. Conversely, the imaginary part has an almost constant value of Im(neff) ≈ 0.032. To have criteria for evaluating the performance of the proposed waveguide, two parameters called figure-of-merit (FOM)44 and confinement loss (LC)45 are defined as follows:

where λ is given in μm. The FOM represents the propagation length normalized to the SPP’s wavelength, and the LC represents the losses arising from the leaky nature of the modes and the non-perfect structure of the waveguides. It is obvious that higher values of FOM and lower values of LC are desirable. Figure 3b shows the FOM and LC of the waveguide as a function of w variations. The highest value of FOM = 627.9, achieved for w = 130 nm at λ = 10 μm. However, the waveguide becomes multimode for w = 130 nm at λ = 8 μm. The FOM for w = 120 nm is 620.3 and does not differ significantly from that for w = 130 nm. In addition, the LC has a negligible change for w variations due to the almost constant value of the Im(neff).

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of |E| as a function of the gap between the graphene sheet and the Si strip. The waveguide parameters are w = 120 nm, h = 100 nm, h3 = 20 nm, μc = 0.6 eV, and λ = 10 μm. The gap (h1) increases from 0 to 30 nm with steps of 5 nm. For the case of h1 = 0, the graphene sheet is placed on the Si strip, and there is no gap. Therefore, the permittivity of the graphene sublayer changes from that of air to that of Si. It causes a significant change in the electric field distribution of the fundamental mode. The electric field intensity is maximum in the graphene sheet and gradually decreases in the surrounding ambient. When h1 increases, the electric field is strongly confined to the gap area. The higher the value of h1, the less the confinement of mode and the lower the intensity of the field at the center of the waveguide. Figure 5a shows the real and imaginary parts of the neff for different values of h1 from 0 to 30 nm. A comparison between curves in Figs. 3a, 5a reveals that changes in h1 have a more significant effect on the real and imaginary parts of the neff than changes in w. When h1 = 0, the waveguide has the highest value of the imaginary part, which indicates higher waveguide losses. Creating a gap between the graphene sheet and the Si strip changes the boundary conditions for exciting SPP waves, leading to a significant difference in the real value of neff. As h1 increases, the cross-sectional area of the stimulated mode also increases, causing a reduction in light confinement and resulting in a decrease in the real part of neff. Additionally, the electric field spreads across more space in the ambient region of the structure as h1 increases. In Fig. 5b, the FOM and LC of the waveguide as a function of h1 is displayed. Except for h1 = 0, the FOM varies around 600 for other values of h1. Also, the LC decreases from 0.97 dB/μm to 0.163 dB/μm when h1 increases from 0 to 30 nm. Generally, there is no significant difference for h1 changes from 5 to 30 nm.

In Fig. 6a, the distribution of |E| for the fundamental TM mode is depicted at five wavelengths. Additionally, Fig. 6b illustrates the real and imaginary parts of the neff of the fundamental mode. The real part exhibits a decrease with a rate of −1.588 μm−1, as evident from the electric field intensity at the center of the waveguide in (Fig. 6a). Meanwhile, the imaginary part of neff shows a negligible change as the working wavelength varies. Figure 6c illustrates the FOM and LC of the basic waveguide as a function of the operation wavelength. It is worth noting that the Im(neff) also increases with increasing wavelength. However, this does not mean a linear upward trend in the LC because the LC parameter depends on the wavelength. For this reason, the highest and lowest values of the LC are equal to 0.1842 and 0.1599 dB/μm, observed at λ = 8 μm and λ = 11 μm, respectively.

In addition to the geometric variables, the chemical potential of the graphene sheet is also effective in its waveguiding behavior. Changing the chemical potential of graphene causes a change in its surface conductivity and, consequently, the permittivity of graphene. In Fig. 7a, the distributions of |E| for different values of the chemical potential of graphene from 0.2 to 0.7 eV at λ = 10 μm are observed. Although the waveguide acts as a multimode waveguide for μc = 0.2 eV, it is a single-mode waveguide for higher values of μc. Figure 7b presents the real and imaginary parts of the neff as a function of μc. The higher the μc value, the lower the real and imaginary parts of the neff. However, FOM gives a better criterion to choose a proper value of μc. The highest FOM is 618.2, which is obtained for μc = 0.4 eV (Fig. 7c).

(a) Distribution of the electric field |E| for different values of the μc parameter, (b) the real and imaginary parts of the neff, and (c) the FOM and LC parameters of the waveguide as a function of the μc parameter. The other parameters are w = 120 nm, h = 100 nm, h1 = 30 nm, h3 = 20 nm, and λ = 10 μm.

Proposed 4 × 2 plasmonic encoder

A 4 × 2 encoder has four inputs and two outputs. At any time, only one of the inputs is ON, and the outputs generate the binary code corresponding to the inputs. It is worth noting that the terms “ON” and “OFF” refer to logical “1” and “0” states, respectively. When the In0 input is ON, the outputs Out0 and Out1 are OFF. Therefore, to distinguish whether the input In0 is OFF or ON, an extra output called V is added to the structure. If the V output is ON, the In0 input is ON; otherwise, the In0 input is OFF. The modified truth table of a 4 × 2 encoder and its corresponding block diagram are provided in (Fig. 8).

The schematic of the Si strips of the proposed encoder is shown in (Fig. 9). It consists of four input ports named In0, In1, In2, and In3 and three output ports named V, Out1, and Out2. Two stick-together bent Y-combiners are used to implement OR logic gates, and a straight waveguide is used to detect the In0 input. The distance between the centers of the input ports and the length of the bent section of the Y-combiners are denoted by Db and Lb, respectively. The layer arrangement and other structural parameters of the encoder are the same as those of the basic waveguide: w = 120 nm, h1 = 5 nm, h2 = 95 nm, h3 = 20 nm, and μc = 0.4 eV. It should be noted that two bent Y-combiners are used in the proposed encoder structure. In curved structures, the possibility of converting the guided mode into a radiation one increases with the reduction of light confinement. Although the highest FOM is attained at h1 = 15 nm, the optimal real part of neff shown in Fig. 5a corresponds to h1 = 5 nm. Therefore, this value has been selected for the h1 parameter. The initial values of Db and Lb are selected as 500 nm and 2 μm, respectively.

The distribution of |E| for different cases of the proposed encoder at λ = 10 μm is plotted in (Fig. 10). For this purpose, a surface monitor is used parallel to the graphene sheet with a distance of 5 nm. In Fig. 10a, only In0 is ON, and the other inputs are OFF; therefore, output V is ON. When only In1 is ON, stimulated SPPs propagate toward the Out0 port, and therefore, output Out0 becomes ON, as seen in (Fig. 10b). When In2 is ON, SPPs travel toward the port Out1 and change its logical state to ON (Fig. 10c). Lastly, when In3 is ON, SPP waves pass almost equally from the upper and lower waveguides toward the ports Out0 and Out1, and therefore, these two outputs are in the ON state, as observed in (Fig. 10d). In Fig. 11a–d, the transmission spectra of output ports for the four cases of the encoder are plotted. The performance of the proposed encoder can be measured by defining the minimum extinction ratio (ERmin) parameter as follows46:

where TON,min refers to the minimum transmission value in the logical “1” state (ON), and TOFF,max refers to the maximum transmission value in the logical “0” state (OFF). Ignoring the output V, the ERmin values are plotted for Out0 and Out1 ports in (Fig. 11e). Although the bent Y-combiners are identical, a negligible difference is seen in ERmin values for Out0 and Out1. This is attributed to the presence of the straight waveguide adjacent to the In1 waveguide, which leads to very weak coupling between the In0 and In1 waveguides and the structure asymmetry along the y direction. The ERmin at λ = 10 μm is about 19 dB for both Out0 and Out1 ports. In addition, the insertion loss (IL) of the device can be calculated from the transmission spectra of Fig. 11 as follows26:

The difference between the unity transmission and the transmission at any port determines the IL. The suggested encoder can be considered a system with an individual straight waveguide and two Y-combiners. The straight waveguide shows the minimum IL, while the maximum value of IL of -1.31 dB at λ = 10 μm corresponds to the Ou1 port. In the worst case, the IL increases to -2.6 dB at λ = 12 μm. The cross-talk (CT) is the power coupled from an ON waveguide to the adjacent OFF waveguide. If waveguide 1 is in the ON state and waveguide 2 is in the OFF state, CT can be calculated using the following equation26:

where P1,ON is the power in waveguide 1, and P2,OFF is the power in waveguide 2. The CT values are presented in transmission spectra shown in (Fig. 11a–c). In the worst case, the CT decreases to − 10.71 dB at λ = 12 μm.

Using the two bent Y-combiners involves two geometric parameters, Db and Lb, and the impact of their change is investigated in the following. In Fig. 12a, the transmission spectrum of Out0 is depicted for different Db values ranging from 500 to 800 nm with steps of 100 nm when In3 is ON. It is evident that higher Db values lead to lower transmission values, especially in the longer wavelengths. It should be noted that lower Db values than 500 nm increase the CT. The graphs in Fig. 12b do not show a linear relationship between the transmission spectra and the Lb parameter change. However, the transmission spectra change slightly for Lb values between 1.5 and 2.5 μm, except for Lb = 1 μm, where the device experiences high bending loss. In Fig. 12c, the transmission spectra at the Out0 port for different cases are compared when In3 is in the ON state. This figure proves the findings reported in the design of the basic waveguide. Moreover, it is seen that the existence of the spacer layer has no impact on the transmission spectrum of the encoder because it is far away from the stimulated fundamental mode region. The transmission spectra h3 = 20 nm and h3 = 0 are nearly identical. Finally, the results of the suggested encoder are compared with those of previously reported ones in (Table 1). It is observed that the proposed encoder has far better results than other previous works.

Conclusion

In summary, this paper presented an all-optical 4 × 2 encoder utilizing graphene-plasmonic waveguides. SPPs are stimulated in the gap between the graphene sheet and the Si strips. The effect of geometric parameters on the waveguide’s performance was analyzed through the 3D-FDTD method, demonstrating that introducing a gap between the graphene sheet and the Si strips significantly reduces losses. Additionally, the waveguiding characteristics can be controlled easily by applying an external voltage between the graphene sheet and the metal layer beneath the Si strips. The proposed encoder includes four input ports and three output ports to determine all the possible states of the input signals. The encoder demonstrates an ERmin of 19 dB at λ = 10 μm while maintaining the CT and IL parameters at −21.3 and −1.31 dB, respectively. In the worst case, the CT and IL reach −10.71 and −2.6 dB at λ = 12 μm, respectively. The device’s dimensions are 1.7 μm × 2.5 μm, offering an ultra-compact structure.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Oulton, R. F., Sorger, V. J., Genov, D., Pile, D. & Zhang, X. A hybrid plasmonic waveguide for subwavelength confinement and long-range propagation. Nat. Photon. 2 (8), 496–500 (2008).

Yang, L., Li, P., Wang, H. & Li, Z. Surface plasmon polariton waveguides with subwavelength confinement. Chin. Phys. B 27 (9), 094216 (2018).

Veronis, G. & Fan, S. Modes of subwavelength plasmonic slot waveguides. J. Lightwave Technol. 25 (9), 2511–2521 (2007).

Dmitriev, P. A. et al. Hybrid dielectric-plasmonic nanoantenna with multiresonances for subwavelength photon sources. ACS Photon. 10 (3), 582–594 (2023).

Saeed, M. et al. Graphene-based plasmonic waveguides: a mini review. Plasmonics 17 (3), 901–911 (2022).

Rezaei, M. H., Zarifkar, A. & Miri, M. Ultra-compact electro-optical graphene-based plasmonic multi-logic gate with high extinction ratio. Opt. Mater. 84, 572–578 (2018).

Luo, X., Qiu, T., Lu, W. & Ni, Z. Plasmons in graphene: recent progress and applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 74 (11), 351–376 (2013).

Albrecht, G., Ubl, M., Kaiser, S., Giessen, H. & Hentschel, M. Comprehensive study of plasmonic materials in the visible and near-infrared: linear, refractory, and nonlinear optical properties. ACS Photon. 5 (3), 1058–1067 (2018).

Naik, G. V., Shalaev, V. M. & Boltasseva, A. Alternative plasmonic materials: beyond gold and silver. Adv. Mater. 25 (24), 3264–3294 (2013).

Rezaei, M. H. & Zarifkar, A. Dielectric-loaded graphene-based plasmonic multilogic gate using a multimode interference splitter. Appl. Opt. 57 (35), 10109–10116 (2018).

Gómez-Díaz, J. S. & Perruisseau-Carrier, J. Graphene-based plasmonic switches at near infrared frequencies. Opt. Express 21 (13), 15490–15504 (2013).

Ullah, S. et al. Advances and trends in chemically doped graphene. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 7 (24), 2000999 (2020).

Sharma, T., Zhang, Z., Wang, J., Cheng, Z. & Yu, K. Past, present, and future of hybrid plasmonic waveguides for photonics integrated circuits. Nanatechnol. Precis. Eng. 7, 4, (2024).

Tannaz, S., Moradkhani, M., Taherzade, M. & Rezaei, M. H. Ultracompact, high-extinction ratio XOR, OR, and Feynman logic gates based on plasmonic metal–insulator–metal directional couplers. Appl. Opt. 62 (3), 644–653 (2023).

Fitrakis, E.-P., Kamalakis, T. & Sphicopoulos, T. Slow light in insulator–metal–insulator plasmonic waveguides. JOSA B 28 (9), 2159–2164 (2011).

Sharma, T. Numerical analysis of a GaAs-based hybrid plasmonic waveguide with nanoscale optical confinement and low losses. Plasmonics 18 (1), 183–190 (2023).

Rezaei, M. H. & Zarifkar, A. Graphene-based plasmonic electro-optical SR flip-flop with an ultra-compact footprint. Opt. Express 28 (17), 25167–25179 (2020).

Yang, Y. P. et al. All-optical photonic-crystal encoder capable of operating at multiple wavelengths. Optik 142, 354–359 (2017).

Haddadan, F. & Soroosh, M. Low-power all-optical 8-to-3 encoder using photonic crystal-based waveguides. Photon Netw. Commun. 37, 83–89 (2019).

Hadi, M. M., Mohammed, J. K. & Atiyah, S. M. Design of 4×2 optical encoder utilizing nano-structure plasmonic IMI waveguides. Opt. Continuum 3 (3), 368–378 (2024).

Lu, C., Hu, X., Yang, H. & Gong, Q. All-optical logic binary encoder based on asymmetric plasmonic nanogrooves. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 12 (2013).

Crespo, D., Alonso, J., Morlanes, T. & Bernabeu, E. Optical encoder based on the Lau effect. Opt. Eng. 39 (3), 817–824 (2000).

Shi, Y., Ni, K., Li, X., Zhou, Q. & Wang, X. Highly accurate, absolute optical encoder using a hybrid-positioning method. Opt. Lett. 44 (21), 5258–5261 (2019).

Lee, C. H., Huang, H. J., Chang, J. P. & Chen, Y. C. Incremental optical encoder based on a sinusoidal transmissive pattern. IEEE Photon. J. 14 (1), 1–6 (2021).

Moniem, T. A. All-optical digital 4×2 encoder based on 2D photonic crystal ring resonators. J. Mod. Opt. 63 (8), 735–741 (2016).

Abdulwahid, S. H., Wadday, A. G. & Abdul Sattar, S. M. Structure of 4×2 optical encoder based on hybrid plasmonic waveguides. Appl. Opt. 62 (1), 102–107 (2022).

Haddadan, F. & Soroosh, M. Design and simulation of a subwavelength 4-to-2 graphene-based plasmonic priority encoder. Opt. Laser Technol. 157, 108680 (2023).

Makela, M. et al. Thermal atomic layer deposition of continuous and highly conducting gold thin films. Chem. Mater. 29 (14), 6130–6136 (2017).

Reck, K. A. et al. Early-stage silver growth during sputter deposition on SiO2 and polystyrene–comparison of biased DC magnetron sputtering, high-power impulse magnetron sputtering (HiPIMS) and bipolar HiPIMS. Appl. Surf. Sci. 160392 (2024).

Borini, S., Rossi, A., Boarino, L. & Amato, G. Patterning of porous silicon by electron-beam lithography. J. Electrochem. Soc. 150 (5), G311 (2003).

Cardenas, J. et al. Low loss etchless silicon photonic waveguides. Opt. Express 17 (6), 4752–4757 (2009).

Amirzada, M. R. et al. Prediction of surface roughness as a function of temperature for SiO2 thin-film in PECVD process. Micromachines 13 (2), 314 (2022).

Alayo, M., Pereyra, I. & Carreno, M. Thick SiOxNy and SiO2 films obtained by PECVD technique at low temperatures. Thin Solid Films 332 (1–2), 40–45 (1998).

Li, P. et al. Graphene-based transparent electrodes for hybrid solar cells. Front. Mater. 1, 26 (2014).

Bolotin, K. I. et al. Ultrahigh electron mobility in suspended graphene. Solid State Commun. 146, 9–10 (2008).

Hanson, G. W. Dyadic Green’s functions and guided surface waves for a surface conductivity model of graphene. J. Appl. Phys. 103, 6 (2008).

Lu, H. et al. Graphene-based active slow surface plasmon polaritons. Sci. Rep. 5 (1), 1–7 (2015).

Rezaei, M. H. & Zarifkar, A. High-extinction ratio and ultra-compact two-bit comparators based on graphene-plasmonic waveguides. Appl. Opt. 58 (36), 9829–9838 (2019).

Pan, T. et al. Analysis of an electro-optic modulator based on a graphene-silicon hybrid 1D photonic crystal nanobeam cavity. Opt. Express 23 (18), 23357–23364 (2015).

Safinezhad, A., Eslami, M. R., Jafari Jozani, K. & Rezaei, M. H. Ultra-compact all-optical reversible Feynman gate based on suspended graphene plasmonic waveguides. Opt. Quant. Electron. 54 (5), 295 (2022).

Palik, E. D. Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids (Academic, 1998).

Lide, D. R. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (CRC, 2004).

Ansys Lumerical, F. D. T. D. Ansys Lumerical FDTD: Simulation of Photonic Components, Ansys, Inc. (Canonsburg, PA, USA, Version 2020).

Yarahmadi, M., Moravvej-Farshi, M. K. & Yousefi, L. Subwavelength graphene-based plasmonic THz switches and logic gates. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 5 (5), 725–731 (2015).

Xu, H., Wu, J., Xu, K., Dai, Y. & Lin, J. Highly nonlinear all-solid photonic crystal fibers with low dispersion slope. Appl. Opt. 51 (8), 1021–1027 (2012).

Eslami, M. R., Piran, P., Bakhtiari, S. & Rezaei, M. H. Implementation of all two-input/one-output logical operations using a simple electro-optical graphene-based plasmonic structure. Opt. Quant. Electron. 54 (7), 411 (2022).

Seif-Dargahi, H. Ultra-fast all-optical encoder using photonic crystal-based ring resonators. Photon Netw. Commun. 36 (2), 272–277 (2018).

Hadadan, F. & Soroosh, M. A new proposal for 4-to-2 optical encoder using nonlinear photonic crystal ring resonators. Int. J. Opt. Photon. 13 (2), 119–126 (2019).

Naghizade, S. & Saghaei, H. A novel design of all-optical 4 to 2 encoder with multiple defects in silica-based photonic crystal fiber. Optik 222, 165419 (2020).

Naghizade, S. & Khoshsima, H. Low input power an all optical 4×2 encoder based on triangular lattice shape photonic crystal. J. Opt. Commun. 42 (1), 17–24 (2021).

Haddadan, F., Soroosh, M. & Alaei-Sheini, N. Designing an electro-optical encoder based on photonic crystals using the graphene–Al2O3 stacks. Appl. Opt. 59 (7), 2179–2185 (2020).

Haddadan, F., Soroosh, M. & Alaei-Sheini, N. Cross-talk reduction in a graphene-based ultra-compact plasmonic encoder using an Au nano-ridge on a silicon substrate. Appl. Opt. 61 (11), 3209–3217 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. Kanwal: Software, Data curation, Methodology, Investigation, Writing. M. R. Saeed: Software, Methodology, Investigation, Writing. F. K. AL-Shammri: Investigation, Writing—review, and editing. M. H. Rezaei: Software, Methodology, Investigation, Supervision, Writing—review, and editing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kanwal, S., Saeed, M.R., AL-Shammri, F.K. et al. Cross-talk-free, high extinction ratio, and ultra-compact all‑optical 4 × 2 encoder using graphene-based plasmonic waveguides. Sci Rep 15, 3761 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86387-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86387-z