Abstract

To increase the accuracy as well as effectiveness of predicting the level of CO2 in mushroom cultivating greenhouses, two optimized prediction models of long and short term memory neural networks (VMD-SSA-LSTM and VMD-DBO-LSTM) are proposed. To start with, time series data on greenhouse CO2 concentrations were decomposed to get intrinsic mode function (IMF) at various time scales. The sparrow search algorithm (SSA) or dung beetle optimization Algorithm (DBO) is then used to optimize the amount of hidden layer neurons, discover the best learning rate, find the optimal iteration times, and improve prediction accuracy. Finally, the SSA or DBO optimized LSTM network is applied to represent the dynamic time of the multi-variable feature series, resulting in CO2 concentration predictions. The model for forecasting presented in this research was used to forecast CO2 concentrations in an experimental greenhouse at Yunnan Normal University. A comparison experiment between the LSTM, EMD-LSTM and VMD-LSTM models is carried out, indicating that the VMD-SSA-LSTM and VMD-DBO-LSTM models outperform the others in terms of prediction accuracy, while VMD-DBO-LSTM model is faster in calculation. The results were compared to actual data, revealing mean absolute errors, mean absolute percentage errors, root-mean-square errors and R2 of the model optimized by SSA are 2.3488 ppm, 0.4593%, and 2.9958 ppm on sunny days, and 6.6212 ppm, 1.1721%, and 8.2909 ppm on cloudy days, respectively. The results of the model optimized by DBO are 2.6365 ppm, 0.5140%, 3.3014 ppm and 0.9919 on sunny days, and 5.1328 ppm, 0.8990%, 6.8016 ppm and 0.9942 on cloudy days, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An effective prediction model in an agricultural greenhouse is instrumental in enhancing the energy efficiency of the control system and ensuring environmental suitability. However, establishing an accurate model is challenging due to the delayed response of the environmental regulation process within the greenhouse1,2. The research indicates that the dynamic response of the greenhouse environment lags not only behind changes in external factors but also behind adjustments in system variables, such as air volume and air temperature. This lag contributes to a series of issues, including untimely adjustments, poor stability, and reduced operating efficiency. Among these factors, the CO2 content in the greenhouse is significantly affected by crops, thereby impacting crops growth. Elevated carbon dioxide concentrations impede crop respiration, while insufficient concentrations result in a reduction of photosynthetic rates. Therefore, understanding the dynamic patterns of CO2 fluctuations and accurately predicting future concentrations is essential for effectively managing CO2 levels. This knowledge enables precise regulation of CO2 concentrations, creating an optimal environment conducive to optimal crop growth.

Currently, agricultural greenhouses are widely used to cultivate plant crops and edible mushrooms. In consideration of the aforementioned, some experiments have been undertaken to maximize photosynthesis in plant crops using CO2 fertilization3,4. When CO2 is applied as a fertilized, it serves to enhance crop growth and elevate productivity5. The relationship between the amount of applied CO2 fertilization and crop productivity is no-linear, hence, determining the optimal quantity of CO2 is imperative for precision agriculture6,7. However, in greenhouse settings, the concentration of CO2 is influenced by both structural factors, including the ventilation level, and ambient variables such as light intensity. Consequently, achieving the saturate of the optimal CO2 concentration proves to be a challenging endeavor8. Mushrooms, another crop cultivated in greenhouses that does not photosynthesize, predominantly release CO2 through respiration. Consequently, CO2 level in the greenhouse tend to rise continuously, necessitating ventilation to prevent an increase in deformed mushroom output. Guo et al.9 utilized a closed-circuit device, GXH-305 CO2 infrared analyzer, to measure the CO2 release from edible mushroom across six culture materials. Their findings revealed that low CO2 concentration stimulated mycelia CO2 release. While high concentration inhibited it. Moreover, the sensitivity of edible mushrooms to CO2 concentration varied significantly at different growth stages, with the order being fruiting stage > entity primordium formation stage > mycelium growth stage10. During the fruiting body development stage, CO2 concentration emerges as the primary gas component significantly influencing fruiting body growth. Controlled CO2 concentration dictated the relative ratio of cap expansion to stalk elongation in the fruiting body. Excessively high concentration can hinder normal development of fruiting body, resulting in excessive stalk length and bud degeneration11. Therefore, it has important practical effect on the prediction of CO2 in mushroom greenhouse.

The mechanism of CO2 production through respiration in edible mushrooms is intricate. Additionally, environmental changes within a greenhouse are more complex compared to a “plant factory” due to the incomplete insulation of greenhouses12. Furthermore, it is important to take into account plant growth factors and different greenhouse environments, as the CO2 concentrations can be influenced by the conditions in which mushrooms develop. Hence, accurately forecasting the CO2 concentration in a mushroom greenhouse is a challenging task.

Researchers, both domestic and international, have put forth many approaches for predicting and providing early warnings for CO2 concentration. These methods can be broadly categorized into two groups: the model based on physical and chemical statistics and the model based on intelligent algorithm. Based on the model of physicochemical statistics, the change rule of CO2 emission was quantitatively analyzed from physicochemical point of view13. This type of prediction model requires precise experimental data to support it. The workload associated with this model is substantial, and its practicality and stability are low. Ensuring accurate forecast accuracy is challenging. Nevertheless, the ecosystem within an edible mushroom greenhouse is intricate, with numerous environmental elements that mutually influence one another. Currently, there is limited study on predicting the concentration of CO2 in greenhouses used for cultivating edible mushrooms, taking into account different environmental factors. Additionally, the accuracy of existing models for predicting CO2 concentration needs to be enhanced.

In recent times, there has been a significant focus on the study of deep learning due to its capacity to attain advanced levels of abstraction from unprocessed data14,15. The machine learning algorithm utilizes an intelligence algorithm to train and test the dataset, resulting in the creation of a prediction model that is based on optimal parameters. The prediction model, utilizing an intelligent algorithm, possesses the capability to examine a greater number of environmental parameters and exhibits a high level of practicality. An artificial neural network (ANN) serves as the foundation for deep learning method, and its topology might vary based on the specific algorithm being used. Artificial neural networks (ANNs) have been employed to examine the nonlinear associations within the environment for meteorological data analysis16,17. The usage of artificial neural networks (ANNs) was also explored for the estimation of global carbon dioxide emission18 and greenhouse carbon dioxide (CO2) levels19. The previous study confirmed that an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) can be taught to identify the correlation between CO2 concentrations and environmental parameters. Nevertheless, the estimation was limited to current circumstances, making it challenging to apply for proactive management, such as CO2 fertilization. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) are employed in deep learning to interpret sequential data, such as voice and video20. Specifically, among the several recurrent neural network (RNN) methods, Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) stands out for its ability to analyze data over an extended time frame21. LSTM models were utilized to forecast the electrical conductivity and ion concentrations of nutrient solutions in greenhouse environments22. Moon et al.23 employed a long and short term memory model to predict the levels of CO2 in the greenhouse. Their projections were derived from the greenhouse environmental characteristics. Their model successfully predicted the fluctuations in CO2 levels at 10-min intervals, achieving a test accuracy of R2 = 0.7824. Therefore, after being trained, the LSTM model can be used to predict future levels of CO2 concentration. Subsequently, this can be utilized to maximize the process of CO2 enrichment in greenhouses, hence augmenting the process of photosynthesis. However, it still faces the disadvantages of restricted accuracy and slow computational speed.

An optimized LSTM prediction model was suggested to accurately predict CO2 concentrations in edible mushroom greenhouses. The model incorporates variational mode decomposition (VMD), the sparrow search algorithm (SSA) or dung beetle optimization algorithm (DBO), and a Long Short-Term Memory neural network (LSTM). The CO2 content in greenhouses is affected by cumulative changes in other environmental conditions. Light, temperature and humidity will affect the respiration of edible mushroom, and then affect the CO2 content. At the same time, for a naturally ventilated greenhouse, the outdoor wind speed will also affect the CO2 content. Therefore, light, temperature, humidity and outdoor wind speed are taken as input parameters, and CO2 content is taken as output. Five models, LSTM, EMD-LSTM, VMD-LSTM, VMD-SSA-LSTM and VMD-DBO-LSTM, were used to predict and compare the CO2 concentration in the greenhouse of edible mushroom growing in Yunnan Normal University, and the feasibility of VMD-SSA-LSTM and VMD-DBO-LSTM model was verified.

Metholdology

Signal decomposition method

Empirical mode decomposition (EMD)

Empirical Modal Decomposition (EMD) is a signal processing method for nonlinear, non-stationary time series25. After EMD processing, the original signal will be decomposed into the sum of several intrinsic mode functions (IMFs) based on the local characteristic time scale of the signal. At the same time, the EMD decomposed signal will be gradually smoothed, eliminating the problem that the basis function is not adaptive.

The basic EMD process is as follows:

-

Step 1 Set the original sequence as s(t), calculate the local maximum and minimum points in s(t), and use the cubic spline difference method to get the upper and lower envelope Imin (t) and Imax (t) of the original sequence.

-

Step 2 Calculate the average value of the upper and lower envelopes.

$$m\left( t \right) = \frac{{I_{\min } \left( t \right) + I_{\max } \left( t \right)}}{2}$$(1) -

Step 3 Calculate the new sequence.

$$h_{1} \left( t \right) = s\left( t \right) - m\left( t \right)$$(2) -

Step 4 Repeat step 3 and screen h1 (t) until the decomposed signal is stable.

-

Step 5 Finally, the decomposition of s(t) into k IMFs and the residual component rt (k).

$$\left\{ \begin{gathered} r_{2} (t) = r_{1} (t) - h_{2} (t) \hfill \\ r_{3} (t) = r_{2} (t) - h_{3} (t) \hfill \\ \ldots \ldots \hfill \\ r_{k} (t) = r_{k - 1} (t) - h_{k} (t) \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right.$$(3) -

Step 6 The original signal is reconstructed as:

$$s(t) = \sum\limits_{i = 1}^{k} {h_{i} } (t) + r_{k} (t)$$(4)

Variational mode decomposition (VMD)

Variational mode decomposition (VMD) is a completely non-recursive decomposition model26 that may adaptively find the correlated frequency bands while also estimating the appropriate modes, allowing for correct error balancing. The objective of VMD is to partition the input signal \(f(t)\), which consists of real-valued data, into distinct sub-signals or modes \({u}_{k}\). It is assumed that each mode \({u}_{k}\) is predominantly concentrated around the central frequency \({w}_{k}\). VMD is decomposed \(f(t)\) into k subsequences. The procedure consists of the following steps:

-

Step 1 The Hilbert transform is used to compute the related analytic signal for each mode \({u}_{k}\), and then the spectrum is generated.

-

Step 2 Shift the frequency spectrum of the modes to the baseband by utilizing their corresponding approximated center frequency.

-

Step 3 Compute the bandwidth by evaluating the Gaussian smoothness of the demodulated signal, namely by calculating the L2 norm of the gradient. The ensuing constrained variational problem is delineated as follows:

$$\left\{ \begin{gathered} \mathop {\min }\limits_{{\left\{ {u_{k} } \right\},\left\{ {w_{k} } \right\}}} \left\{ {\sum\limits_{k} {\left\| {\partial_{t} \left[ {\left( {\delta (t) + \frac{j}{\pi t}} \right)u_{k} (t)} \right]e^{{ - jw_{k} t}} } \right\|_{2}^{2} } } \right\} \hfill \\ s.t.\sum\limits_{k} {u_{k} = f} \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right.$$(5)where \({u}_{k}\) is the kth modal component; \({w}_{k}\) represents the frequency center associated with the kth mode; the unit impulse function is donated by \(\delta (t)\). The quadratic penalty term and Lagrange multiplier \(\lambda\) are introduced to make the problem unconstrained. At last, it is solved by alternate direction multiplier method (ADMM).

Model optimization method

Sparrow search algorithm (SSA)

Sparrow search algorithm (SSA)27 is an innovative optimization method inspired by the foraging and anti-trapping behavior of sparrows.

The SSA optimization process is described as follows:

The discoverer position \({X}_{i,j}^{t+1}\) update formula is:

where \(i_{{ter_{\max } }}\) is the upper limit of iterations; \(X_{i,j}^{t}\) is the position of the i-th sparrow in the j-th dimension; \(\alpha\) \(\in\) (0,1], represents a randomly generated number; R2 \(\in\) [0,1], indicates a value that serves as a warning; ST \(\in\) [0.5,1], represents a value that is considered safe; Q Signifies that the random numbers adhere to a normal distribution; L is a 1 × d matrix where every element is 1.

Subscriber location \(X_{i,j}^{t + 1}\) Updated:

Among this,

where Xp is the optimal location of the current discoverer; Xworst is the current worst position overall; A is a 1 × d matrix in which the value of 1 or − 1 is designated at random to each element.

Assuming that between 10 and 20% of the sparrows had knowledge of the risk. Cognizant of the peril, the sparrow will rapidly relocate to the secure area, and the alert position \(X_{i,j}^{t}\) is denoted as:

where Xbest is the current optimal position overall; β is a random variable representing the step control parameter, which is distributed according to a normal distribution with a mean of 0 and a variance of 1. K \(\in\) [− 1,1], is a random value; fi is the current fitness value of an individual sparrow; fg is the current global optimal fitness value; fw is the worst global fitness value. ε represents a constant.

The steps of the SSA algorithm are as follows.

-

Step 1 Begin by setting the initial population, the ratio of predators to prey, and the number of iterations.

-

Step 2 Compute the fitness value and arrange it in descending order.

-

Step 3 Update the location of the finder.

-

Step 4 Update the location of new entrants.

-

Step 5 Update the alert position (the sparrow which is aware of the danger).

-

Step 6 Calculate the fitness value and update the sparrow position.

-

Step 7 The output is displayed if the prerequisites are satisfied. Alternatively, iterate through Steps 2 to 6 again.

Dung beetle optimization algorithm (DBO)

DBO algorithm is a new swarm intelligence-based optimization algorithm proposed by Shen’s team in 202328, which is mainly inspired by the rolling, dancing, foraging, stealing and reproduction behaviors of dung beetles. According to the developed DBO algorithm, the dung beetle group consists of rolling dung beetles, brooding dung beetles, young dung beetles and thieving dung beetles.

To simulate ball rolling behavior, dung beetles need to move in a given direction throughout the search space, assuming that the intensity of the light source also affects the path of dung beetles. During the rolling process, the position of the rolling dung beetle is updated:

where t represents the number of current iterations; xi(t) represents the position information of the i dung beetle at the t iteration; K ∈ (0,0.2]; b represents the constant (0,1); \(\alpha\) is a natural coefficient assigned − 1 or 1; Xw represents the global worst position; Δx simulates changes in light intensity, with higher values indicating weaker light sources.

When the beetle encounters an obstacle, it needs to dance to reposition itself, and in order to simulate the dance, it uses the tangent function to get a new rolling direction. Define the position update of the rolling dung beetle as follows:

where |xi(t) − xi(t − 1)| is the difference between the position of the i beetle at the t and t − 1 iterations; θ indicates the tilt angle, and the position is not updated when θ is 0, π/2 and π.

Selection of suitable spawning sites is crucial for dung beetles, so a boundary selection strategy is proposed to simulate the spawning area of female dung beetles, and the dynamic renewal of spawning area can promote the development of local areas, as defined below:

where X* represents the current local optimal position; Lb* and Ub* represent the lower and upper bounds of the spawning area, respectively. R=1 − t/Tmax, where Tmax indicates the maximum number of iterations; Lb and Ub represent the lower and upper bounds of the optimization problem, respectively.

After determining the spawning area, female dung beetles will choose the egg balls in this area to lay eggs. As can be seen from Eq. (12), the boundary range of the spawning area is dynamically changing. Therefore, the position of the hatching dung beetle is also dynamic during the iteration process, defined as follows:

where, Bi(t) represents the position information of the i hatched dung beetle at the t iteration; b1 and b2 represent two independent random vectors of size 1 × D, and D represents the dimension of the optimization problem.

Grown dung beetles will come out of the ground to find food, called little dung beetles, so it is necessary to establish an optimal feeding area to guide dung beetles to forage. The optimal feeding area boundary is defined as follows:

where Xb represents the global optimal position; Lbb and Ubb represent the lower and upper bounds of the optimal feeding area, respectively. Other parameters are defined as Eq. (12). The beetle’s position is updated as follows:

where xi(t) represents the position information of the i little dung beetle at the t iteration; C1 represents a random number that follows a normal distribution; C2 represents a random vector belonging to (0,1).

It is common in nature for some dung beetles to steal dung balls from other dung beetles, called thief dung beetles, and their stealing ensures that the algorithm can escape the local optimal solution. During the iteration, the thief’s location information is updated as follows:

where xi(t) represents the position information of the i thief at the t iteration; g is a random vector of 1 × D with a normal distribution. S indicates the constant.

The steps of DBO algorithm can be roughly summarized as follows:

-

Step 1 Initialize the parameters of the dung beetle group and DBO algorithm.

-

Step 2 Calculate the fitness value fb according to the objective function.

-

Step 3 Update the position of rolling dung beetles, incubating dung beetles, small dung beetles and dung beetles, determine whether each dung beetle is outside the boundary.

-

Step 4 Update the current optimal solution and its fitness value, and repeat the above steps until t meets the termination condition and outputs the global optimal solution Xb and its fitness value fb.

Long short-term memory neural network (LSTM)

In neural networks, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) are neural networks that have feedback structures. The inputs of these neural networks are not only related to the current input and the weight of the network, but they are also related to the input of the network before the input period29. RNN utilize the hidden layer state information from the previous time step to compute the current output, making it well-suited for handling time series data. Nevertheless, RNNs suffer from the issue of gradient vanishing. As the time series duration increases, RNNs experience a decline in their capacity to learn, leading to the failure of model training. To address this issue, Hochreiter et al.30 proposed Long Short-Term Memory neural network (LSTM) in 1997. The LSTM neural network is a modification of the recurrent neural network that substitutes the hidden layer of neurons with a cell state and three gate structures. This allows for the updating of control information on the cell state31. Figure 1 illustrates the internal unit structure of the LSTM.

The Long Short-Term Memory neural network calculation formula is as follows:

where xt is the input; it represents the input gate; ft represents the forget gate; ct is the cell unit status behind the input and forget gates at the time t; ot is the cell unit status of the output gate at the time t; ht is the all output status of the LSTM unit; σ, tanh represents sigmoid function and hyperbolic tangent activation function, respectively; Wxi, Whi, Wci, Wxf, Whf, Wcf, Wxc, Whc, Wxo, Who and Wco are the weight coefficients; bi, bf, bc and bo are bias vectors.

Input gate screens fresh information and chooses whether to input it. The forget gate determines the discarding of historical information in accordance with the activation function. The output gate regulates the ultimate output and retention of information32. Thus, LSTM has the capability to selectively preserve relevant information based on the cell unit state and three gates topologies. It also has strong predictive accuracy and can perform more precise prediction analysis.

VMD-SSA-LSTM model prediction process

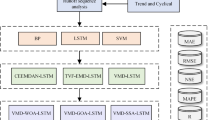

The CO2 concentration data sequence in the greenhouse is a dynamic signal influenced by several environmental parameters. In this paper, variational mode decomposition, sparrow search algorithm and long short-term memory neural network are combined to construct a prediction model of CO2 concentration in the greenhouse of edible mushroom cultivation based on VMD-SSA-LSTM to predict CO2 concentration. Figure 2 displays the flow chart of the greenhouse CO2 concentration prediction model, which is based on VMD-SSA-LSTM.

The specific forecasting steps are as follows.

-

Step 1 Data collection and processing: The Internet of Things is employed to gather data on temperature, relative humidity, and CO2 concentration within the greenhouse. Simultaneously, a compact weather station is utilized to collect real-time data on wind speed, temperature, and relative humidity outside the greenhouse. The collected data is then subjected to pre-processing and analysis. The data serves as input for the model.

-

Step 2 The VMD approach was employed to decompose the data series of CO2 concentration, and k components were obtained. Through the VMD method, the non-stationary and nonlinear CO2 concentration series are decomposed into different scale data components, which are relatively stable and have different local characteristics.

-

Step 3 Begin by defining the search parameters for the sparrow population size N, maximum number of iterations M, and the range of parameters for the number of hidden layer neurons H, training times E, and learning rate η. Next, choose the mean square error (MMSE) as the objective function for the optimization algorithm. Finally, develop the search algorithm and establish the long and short period channel network Phase coupling model (SSA-LSTM).

-

Step 4 Utilize SSA-LSTM prediction models as input for each component to derive k prediction models.

-

Step 5 Ultimately, combine the projected values from each of the k prediction models to derive the predicted value of CO2 concentration.

Similarly, replacing the SSA optimization model with DBO can be obtained VMD-DBO-LSTM model prediction process.

Experiment

Experimental data collection

The CO2 concentration of a mushroom growing greenhouse on an experimental platform in Kunming, Yunnan Province was selected as the focus of this study. Data was collected each 1 min with an environmental parameter monitoring system based on the Internet of Things. A total of 5760 environmental data were collected, spanning from September 15, 2023 to September 16, 2023 (sunny days) and October 7, 2023 to October 8, 2023 (cloudy days). These data include key environmental factors outside the greenhouse such as solar radiation, temperature, relative humidity, and wind direction, as well as indoor temperature and indoor relative humidity. They are utilized as experimental data in this paper for predicting greenhouse CO2 concentration in the future. The specific information of the mushroom greenhouse is presented in Table 1.

Experimental data preprocessing

The pretreatment of greenhouse environmental parameter data involves two steps:

-

(1)

Abnormal data processing

The data collected from the sensors undergoes processing using the Pauta criterion. According to this rule, if the absolute disparity between the collected value of the greenhouse environmental parameter and its average value exceeds 3 times its standard deviation, it is flagged as abnormal data. In such cases, the data at the anomaly point will be replaced with the average value of the data on both sides of the anomaly point.

where Xn represents collection value of greenhouse environmental parameters; Xn' is the parameter value after the exception data is processed; \(\overline{X}\) represents mean of the greenhouse environmental parameter data series; \(\sigma_{{x_{n} }}\) is the standard deviation of greenhouse environmental parameter data series; n is the data size.

-

(2)

Normalization processing

To improve the accuracy of forecasting, the environmental parameter data in the greenhouse is normalized due to the differing dimensions of these parameters. The calculation formula is:

where Xmax represents the maximum value, while Xmin is the minimum value, X* represents the normalized value.

The fluctuation of outdoor weather significantly impacts the release of CO2 from indoor edible mushrooms. Conversely, the CO2 concentration within the greenhouse imposes limitations on the growth of edible mushroom fruiting bodies. Therefore, enhancing the prediction accuracy of CO2 concentration within the greenhouse holds paramount importance for comprehending the growth status of edible mushrooms and environmental discrimination. The CO2 data, acquired through field measurement, exhibits distinct nonlinearity and non-stationarity. This characteristic makes it suitable for evaluating the precision of different prediction models.

During the prediction phase, 70% of the data is allocated for training purposes, while the remaining 30% is reserved as the test dataset (as illustrated in Figure 3). Following the generation of prediction results, the error distribution between the predicted value and the actual values of the model in the test set is examined. Various evaluation criteria are employed to assess the predictive accuracy of diverse models.

Evaluation criteria for experimental results

Five metrics, namely mean absolute error (MAE), mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), root mean square error (RMSE), R2 and time complexity, are utilized to evaluate and compare the predictive performance of different forecasting systems.

MAE is used to represent the mean absolute error between the predicted value and the actual value, it is calculated as Eq. (12). It expresses the difference between the predicted value and the actual value of each sample on average. MAE has the same dimension as y, the smaller the better. In order to overcome the deficiency of MAE, namely its dependence of unit scale, MAPE (mean absolute percentage error) is introduced. MAPE is a statistical index to measure the accuracy of the prediction, which is a percentage value, calculated as Eq. (20). It is generally believed that MAPE is less than 10% means the prediction accuracy is high. The disadvantage is that when yactural is equal to 0, the calculation doesn’t work. In general, RMSE (root mean square error) can well reflect the degree of deviation between the predicted value of the regression model and the true value, which is calculated as Eq. (22). However, in actual problems, MAE and RMSE are susceptible to the influence of outliers, that means outliers can affect model performance significantly. The denominator of the calculation formula of R2 represents the dispersion degree of the original data, while the numerator is the error of the predicted data and the actual data. Quotient of the two eliminate the influence of the dispersion degree of the original data. It is the change of the data to characterize a good or bad fit. R2 is calculated as Eq. (23), The value ranges from 0 to 1. The closer to 1, the better the model fits the data.

The accuracy of the prediction approach enhances as the error decreases, leading to a more effective forecast outcome. In addition, time complexity is an important index to measure the algorithm execution time, which reflects the increase of the algorithm running time with the size of the problem.

Results and analysis

In this paper, five models LSTM, EMD-LSTM, VMD-LSTM, VMD-SSA-LSTM and VMD-DBO-LSTM are selected for experimental comparison.

Results of CO2 concentration sequence decomposition based on EMD and VMD

Considering the evident nonlinear and non-stationary nature of the CO2 concentration data series in edible mushroom greenhouse, the EMD and VMD algorithm was applied in this study to decompose the CO2 concentration data collected from September 15 to September 16, 2023 (sunny days) and October 7 to 8, 2023 (cloudy days). The top 70% of CO2 concentration data series was selected as input, with each component of the CO2 concentration data serving as the output. The decomposition results are depicted in Fig. 4.

As can be seen from Fig. 4, the CO2 concentration sequence is decomposed into 7 IMFs and a residual term, and IMF increases in order of frequency. With the increase of decomposition times, the image tends to be a smooth curve. The component IMF1–IMF4 has a high frequency and high volatility, while the component IMF5–IMF7 has a low and stable overall frequency. Therefore, EMD decomposition can effectively reduce the volatility of CO2 concentration series, decompose the stable part of CO2 concentration series, and reduce the error for the subsequent CO2 prediction.

It can be seen from Fig. 5, the CO2 concentration data series was decomposed into 5 intrinsic mde functions (IMFs) by the VMD algorithm. The implicit change information and local characteristic information of the greenhouse CO2 concentration data series were highlighted in each IMF component. Among these components, IMF2 to IMF5 exhibit strong variability, high frequency and certain random disorder, representing the influence of random uncertainties, both internal and external, on the features of the CO2 concentration variation in greenhouses. The volatility of IMFs on cloudy days is significantly greater than that on sunny days.

Utilizing the VMD algorithm to decompose greenhouse CO2 concentration data offers several advantages. Firstly, it helps mitigate the impact of non-stationarity and wave motion on prediction accuracy. By decomposing the data into Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs), the VMD algorithm extracts underlying trends and patterns, allowing for more stable and predictable data representations. Additionally, the decomposition process reduces the complexity of the CO2 concentration data, thereby simplifying the prediction task based on LSTM neural networks.

Compared with EMD decomposition, VMD has better decomposition precision and noise resistance. In particular, when the VMD is used to process the CO2 concentration data set in the greenhouse, the mode aliasing is better overcome, reflecting that the VMD can achieve better separation of signals with similar frequencies. Compared with the IMFs obtained after decomposition of VMD and EMD, EMD is decomposed into a series of IMF components from high frequency to low frequency, and each IMF component has a wide frequency band, while each IMF component obtained from VMD decomposition has a limited bandwidth around its own central frequency, so VMD decomposition results are more accurate.

By incorporating VMD-decomposed data into the LSTM model, the neural network can focus on capturing the essential features and dynamics of the CO2 concentration variations without being overwhelmed by noise or irrelevant information. This streamlined approach enhances the efficiency and effectiveness of the prediction process, leading to more accurate forecasts of CO2 concentration in the greenhouse. Overall, the integration of VMD decomposition with LSTM modeling represents a powerful strategy for improving prediction accuracy while reducing computational complexity.

Prediction of CO2 concentration based on LSTM, EMD-LSTM, VMD-LSTM

In this paper, the first 70% of the data collected from September 15th-16th, 2023 (sunny days) and October 7–8th, 2023 (cloudy days) were chosen as training samples. The CO2 concentration of the greenhouse for the subsequent 864 min, or the last 30% of data, was predicted using the LSTM, EMD-LSTM, VMD-LSTM model. To train and forecast each IMF component derived from EMD and VMD decomposition, an LSTM model is employed. The input consisted of six variables, while the output comprised one variable. The overall predicted greenhouse CO2 concentration results were obtained by aggregating the predicted results of each IMF component. The performance of the prediction model presented in this study was assessed using three different models: the LSTM, VMD-LSTM, and VMD-SSA-LSTM, which were employed to forecast the CO2 concentration in greenhouses, respectively. Figure 5 displays the prediction results of each model for the last 30% of the data.

It can be seen from Fig. 6 that the prediction of greenhouse CO2 content on sunny days is more accurate than that on cloudy days. It is worth noting that the simple LSTM model has the largest deviation from the measured CO2 concentration value, while the prediction accuracy of EMD-LSTM and VMD-LSTM models has been improved.

Figure 7 shows the comparison of errors in predicting CO2 concentration by the LSTM, EMD-LSTM, and VMD-LSTM models, where the horizontal reference line represents the 0 scale. The simple LSTM model has the largest error, reaching ± 30 ppm and ± 50 ppm on sunny and cloudy days, respectively, and the prediction results are not satisfactory. As shown in Figure 7a, the prediction error of CO2 concentration by EMD-LSTM and VMD-LSTM models on sunny days is similar, and the error is between ± 10 ppm. As shown in Fig. 6b, the overall error on cloudy days is larger, ranging from ± 50 ppm. Compared with VMD-LSTM, the prediction error of EMD-LSTM is larger, especially on cloudy days. Note When using EMD for data decomposition, the machine regards some noise as features due to excessive sample noise interference, which disrupts the preset classification rules and leads to overfitting. The results show that the prediction accuracy of the training set is better, but the prediction accuracy of the test set decreases greatly. It can be seen from the results that the prediction effect of modal decomposition of data is better than that of LSTM alone, and VMD is better than EMD in terms of decomposition accuracy and noise resistance.

Prediction of CO2 concentration based on VMD-SSA-LSTM and VMD-DBO-LSTM

In this part, the empirical mode decomposition (EMD) method was abandoned, then the CO2 concentration of the greenhouse for the last 30% of data, was predicted using the VMD-SSA-LSTM and VMD-DBO-LSTM model. The measured data and the predictions were then compared. The experimental procedure is illustrated in Fig. 2. To train and forecast each IMF component derived from EMD and VMD methods, an LSTM model is employed. The input consisted of six variables, while the output comprised one variable. The overall predicted greenhouse CO2 concentration results were obtained by aggregating the predicted results of each IMF component. The performance of the prediction model presented in this study was assessed respectively. Figure 8 displays the prediction results of each model for the last 30% of the data.

By visually comparing Fig. 8 with Fig. 6, the accuracy of VMD-LSTM after optimization is greatly improved, but the performance on cloudy days is still worse than that on sunny days. As shown in Fig. 9, the prediction errors of VMD-LSTM model optimized by SSA and DBO are close to each other, but the prediction results of VMD-DBO-LSTM model are more accurate and closer to the actual value of CO2 concentration. Figure 9 shows the comparison of errors in predicting CO2 concentration by the LSTM, VMD-SSA-LSTM, and VMD-DBO-LSTM models, where the horizontal reference line represents the 0 scale. As shown in Figure 9a, the VMD-DBO-LSTM model has the smallest prediction error of CO2 concentration, ranging from ± 10 ppm on sunny days to slightly larger error of ± 20 ppm on cloudy days.

The higher accuracy and faster operation speed reflect the DBO has the characteristics of strong optimization ability and fast convergence speed, especially in cloudy days.

To conduct quantitative analysis and evaluation of the prediction results of the five models, MAE, MAPE, RMSE and R2 were utilized as evaluation metrics in this research. Tables 2 and 3 present the statistical results of each prediction model under different weather conditions.

As can be seen from Tables 2 to 3, VMD-DBO-LSTM and VMD-SSA-LSTM have similar performance on sunny days. Among them, MAE, MAPE and RMSE of VMD-SSA-LSTM test data are 2.3488 ppm, 0.4593% and 2.9958 ppm, respectively, which are 74.0%, 74.5% and 73.2% lower than that of LSTM model. The MAE, MAPE and RMSE of VMD-DBO-LSTM test data were 2.6365 ppm, 0.5140% and 3.3014 ppm, respectively, which were 70.8%, 71.4% and 70.5% lower than that of LSTM model.

Under cloudy conditions, the VMD-DBO-LSTM model has the highest prediction accuracy on cloudy days. The MAE, MAPE and RMSE of VMD-SSA-LSTM training data were 6.6212 ppm, 1.1721% and 8.2909 ppm, respectively, which were 69.9%, 70.2% and 67.1% lower than that of LSTM model. MAE, MAPE and RMSE of VMD-DBO-LSTM training data are 5.1328 ppm, 0.899% and 6.8016 ppm, respectively, which are reduced by 76.7%, 77.1% and 73.0% compared with LSTM model, respectively.

Figure 10 illustrates a histogram showcasing the variation in error assessment criteria between projected and actual values across different prediction models. In general, the predictions on cloudy days were worse than those on sunny days, regardless of which algorithm was used. The main factors affecting the CO2 content in the greenhouse are the amount of CO2 released by the cultivated edible mushroom and the exchange rate of ambient air. Previous study33 has showed that edible mushroom consumed a lot of oxygen and metabolized CO2 during their growth. However, the specific amount of CO2 released will vary depending on factors such as the type of edible mushroom, growth stage, and environmental conditions. Among them, the cultivation environment conditions such as light, temperature, humidity and ventilation will also affect the metabolic activities of edible mushroom, and then affect the release of CO2. On cloudy days, due to frequent changes in cloud thickness and air quality, solar light will be affected to a certain extent, indirectly affecting the light environment, temperature, humidity and ventilation conditions in the greenhouse, resulting in extremely complex changes in CO2 concentration and reducing the prediction performance of the algorithm. Figure 10 clearly demonstrates the following trends: The VMD-SSA-LSTM and VMD-DBO-LSTM model showcases improved performance in predicting CO2 concentration. The time complexity of VMD-SSA-LSTM is O(k × t × n log n + p × g × d + e × n × l × h2) while VMD-SSA-LSTM is O(k × t × n log n + m × g × d + e × n × l × h2), as shown in Table 4. The overall time complexity structure of the two algorithms is similar because they use the same VMD decomposition and LSTM network, the main difference is the optimization algorithm part (SSA vs. DBO), but since they are both swarm intelligence algorithms, the complexity level is similar. The difference in actual running time between the two mainly depends on: (1) Selection of population size (p or m), (2) Number of iterations (g), (3) Convergence rate of the optimization algorithm itself. Even if choose the same population size and number of iterations, the convergence of the optimization algorithm itself is different. SSA optimization algorithm converges faster in the early stage and can find a better solution quickly, but tends to converge prematurely in the later stage and fall into local optimal. The DBO optimization algorithm is relatively stable in the early stage, and the quality improvement is more obvious in the later stage. Thus, the VMD-DBO-LSTM model is superior even though the variation of light, temperature and humidity in the greenhouse on cloudy days causes the prediction accuracy to decrease significantly. But the choice of optimization method requires trade-offs.

Conclusions

By contrasting the accuracy levels of the five prediction models, several conclusions can be identified:

When LSTM is solely utilized for prediction, significant prediction errors are observed. However, employing EMD and VMD for signal decomposition results in a reduction in prediction error. Subsequently applying DBO and SSA to optimize the LSTM prediction model leads to a substantial enhancement in both prediction capability and accuracy. This comprehensive approach effectively responds to the time characteristics of CO2 series variations in the greenhouse, offering an efficient means of stabilizing the environment and optimizing ventilation system performance. Higher quality solutions can be obtained by choosing DBO optimization mode, but the calculation time is longer. When computing resources are limited or an acceptable solution needs to be obtained quickly, the SSA optimization model is more suitable. It is noted that this study did not compare the anticipated findings with the errors associated with each mode order when decomposing the CO2 concentration signal. Future research will explore the prediction errors of various decomposition modes under diverse optimization conditions to allow for a more thorough comparison of model performance.

The comprehensive performance of the three prediction models is evaluated through multiple error criteria. The results highlight the significant benefits of the VMD-DBO-LSTM model in greenhouse CO2 forecasting. Compared with LSTM and VMD-LSTM models, VMD-DBO-LSTM model has excellent performance in predicting sunny days, with MAE and RMSE reduced by 70.8%, 70.5%, 67.4% and 66.2%, respectively.

There are three main limitations to the model proposed in the manuscript. (1) High calculation cost. Although VMD-DBO-LSTM model has the highest prediction accuracy when dealing with noisy and complex multivariable time series data, its calculation cost is relatively high. (2) Complexity of parameter optimization. Deep learning models usually contain a large number of parameters, and traditional trial-and-error methods for parameter adjustment are time-consuming and error-prone. (3) Subjectivity of parameter Setting. The performance of a VMD depends heavily on its parameter settings, and the existing parameter settings are often based on experience, which can lead to a decline in the quality of the decomposition results and affect the accuracy of the predictive model. These will be the problems to be solved in the future. Additionally, while weather conditions undoubtedly impact greenhouse CO2 levels, this study is limited to clear sky and cloudy conditions. Subsequent research phases will analyze CO2 levels prediction during various growth stages of edible mushrooms, providing a more comprehensive understanding of CO2 dynamics in greenhouse environments.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Afram, A. & Janabi-Sharifi, F. Review of modeling methods for HVAC systems. Appl. Therm. Eng. 67, 507–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2014.03.055 (2014).

Afroz, Z., Shafiullah, G. M., Urmee, T. & Higgins, G. Modeling techniques used in building HVAC control systems: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 83, 64–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.10.044 (2018).

Lotfiomran, N., Köhl, M. & Fromm, J. Interaction effect between elevated CO2 and fertilization on biomass, gas exchange and C/N ratio of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.). Plants 5, 1010–1016. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants5030038 (2016).

Walter, C. O. et al. Transient nature of CO2 fertilization in Arctic tundra. Nature 371(6497), 500–503. https://doi.org/10.1038/371500a0 (1994).

McGrath, J. M. & Lobell, D. B. Regional disparities in the CO2 fertilization effect and implications for crop yields. Environ. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/8/1/014054 (2013).

Kläring, H. P., Hauschild, C., Heißner, A. & Bar-Yosef, B. Model-based control of CO2 concentration in greenhouses at ambient levels increases cucumber yield. Agric. For. Meteorol. 143, 208–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agrformet.2006.12.002 (2007).

Linker, R., Seginer, I. & Gutman, P. O. Optimal CO2 control in a greenhouse modeled with neural networks. Comput. Electron. Agric. 19, 289–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0168-1699(98)00008-8 (1998).

Roy, J. C., Boulard, T., Kittas, C. & Wang, S. Convective and ventilation transfers in greenhouses, part 1: The greenhouse considered as a perfectly stirred tank. Biosyst. Eng. 83, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1006/bioe.2002.0107 (2002).

Guo, J. X., Zhao, Y. H. & Shen, Y. Y. Studies on mycelial respiration of several kinds of Edible Fungi. Chin. J. Eco Agric. 10(3), 74–75. https://doi.org/10.1006/jfls.2001.0409.(inChinese) (2002).

Guo, J. X., Zhong, Y. H. & Zhang, S. X. Effects of carbon dioxide concentration on the growth and development of mushroom CO2. Chin. J. Eco Agric. 8(1), 49–52 (2000).

Turner, E. M. Development of excised sporocarps of Agaricus bisporus and its control by CO2. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 69, 183–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0007-1536(77)80035-1 (1977).

Zhang, Y., Yasutake, D., Hidaka, K., Kitano, M. & Okayasu, T. CFD analysis for evaluating and optimizing spatial distribution of CO2 concentration in a strawberry greenhouse under different CO2 enrichment methods. Comput. Electron. Agric. 179, 105811. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105811 (2020).

Graamans, L., Baeza, E., van den Dobbelsteen, A., Tsafaras, I. & Stanghellini, C. Plant factories versus greenhouses: Comparison of resource use efficiency. Agric. Syst. 160, 31–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2017.11.003 (2018).

Mnih, V. et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 518, 529–533. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14236 (2015).

Silver, D. et al. Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature 529, 484–489. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature16961 (2016).

Hu, Q., Zhang, R. & Zhou, Y. Transfer learning for short-term wind speed prediction with deep neural networks. Renew. Energy 85, 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2015.06.034 (2016).

Liu, Y., Racah, E., Correa, J., Lavers, D., Wehner, M., Kunkel, K. & Collins, W. Application of deep convolutional neural networks for detecting extreme weather in climate datasets application of deep convolutional neural networks for detecting extreme weather in climate datasets. (2016).

Jalaee, S. A. et al. A novel hybrid method based on cuckoo optimization algorithm and artificial neural network to Forecast world’s carbon dioxide emission. MethodsX 8(8), 101310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2021.101310 (2021).

Moon, T. et al. Estimation of greenhouse—CO2 concentration via an artificial neural network that uses environmental factors. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 59, 45–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13580-018-0015-1 (2018).

Zhao, F., Feng, J., Zhao, J., Yang, W. & Yan, S. Robust LSTM-autoencoders for face de-occlusion in the wild. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 27, 778–790. https://doi.org/10.1109/TIP.2017.2771408 (2018).

Greff, K., Srivastava, R.K., Koutník, J., Steunebrink, B.R. & Schmidhuber, J. LSTM: A Search Space Odyssey 1–11 (2016).

Moon, T., Ahn, T. I. & Son, J. E. Long short—Term memory for a model - free estimation of macronutrient ion concentrations of root—Zone in closed—Loop soilless cultures. Plant Methods https://doi.org/10.1186/s13007-019-0443-7 (2019).

Moon, T. & Son, J. E. Knowledge transfer for adapting pre-trained deep neural models to predict different greenhouse environments based on a low quantity of data. Comput. Electron. Agric. 185, 106136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2021.106136 (2021).

Moon, T., Choi, H. Y., Jung, D. H., Chang, S. H. & Son, J. E. Prediction of CO2 concentration via long short-term memory using environmental factors in greenhouses. Horticult. Sci. Technol. 38(2), 201–209. https://doi.org/10.7235/HORT.20200019 (2020).

Huang, N. E. et al. The empirical mode decomposition method and the Hilbert spectrum for non-stationary time series analysis. Proc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1998(454), 903–995 (1971).

Dragomiretskiy, K. & Zosso, D. Variational Mode Decomposition. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. Public. IEEE Signal Process. Soc. 62(3), 531–544 (2014).

Xue, J. & Shen, B. A novel swarm intelligence optimization approach : sparrow search algorithm A novel swarm intelligence optimization approach: Sparrow search algorithm. Syst. Sci. Control Eng. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642583.2019.1708830 (2020).

Xue, J. & Shen, B. Dung beetle optimizer: a new meta-heuristic algorithm for global optimization. J. Supercomput. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11227-022-04959-6 (2023).

Bedi, J. & Toshniwal, D. Empirical mode decomposition based deep learning for electricity demand forecasting. IEEE Access 6, 49144–49156. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2867681 (2018).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9(8), 1735–1780. https://doi.org/10.1162/neco.1997.9.8.1735 (1997).

Chen, Y., Cheng, Q., Fang, X., Yu, H. & Li, D. Principal component analysis and long short-term memory neural network for predicting dissolved oxygen in water for aquaculture. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 34(17), 183–191. https://doi.org/10.11975/j.issn.1002-6819.2018.17.024 (2019).

Yu, Y., Du, L., Yi, X. & Chen, G. Prediction method of NC machine tool’s motion precision based on sequential deeplearning. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 50(1), 421–426. https://doi.org/10.6041/j.issn.1000-1298.2019.01.049(inChinese) (2019).

Pavlík, M., Fleischer, P., Fleischer, P., Pavlík, M. & Šuleková, M. Evaluation of the carbon dioxide production by fungi under different growing conditions. Curr. Microbiol. 77(9), 2374–2384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-020-02033-z (2020).

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Project of Yunnan University Serving Key Industries (Grant No. FWCY-QYCT2024012 and No. FWCY-BSPY2024071), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12362023).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, H., Wang, Y., Ma, X. et al. Prediction of CO2 concentration in mushroom greenhouse via optimized long and short term memory algorithm. Sci Rep 15, 33726 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86394-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86394-0