Abstract

Misoprostol was originally used to treat gastric ulcers, and has been widely used in abortion, cervical maturation, induced labour and postpartum hemorrhage. But there are still many undetected adverse events (AEs). The purpose of this study was to provide a comprehensive overview of the safety of misoprostol. Adverse events related to misoprostol were collected from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database from the first quarter of 2004 to the second quarter of 2024. This study used proportional disequilibrium methods such as reporting odds ratio (ROR), proportional reporting ratio (PRR), Bayesian confidence propagation neural network (BCPNN), and empirical Bayes geometric mean (EBGM) to detect AEs. After analyzing 17,427,762 adverse event reports, a total of 2032 adverse events reports related to misoprostol were identified, involving 23 system organ classes and 30 preferred terms. The most common AEs were foetal exposure during delivery(n = 201), uterine tachysystole(n = 95), uterine rupture (n = 95), and heart rate decreased (n = 93). Although most AEs complied with the drug instruction, new AEs signals such as congenital aqueductal stenosis and congenital brain damage were also identified. Clinicians should make appropriate evaluation when using misoprostol, closely monitor the indicators of patients, and have appropriate countermeasures for possible adverse events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Misoprostol can inhibit gastric acid secretion. It was first marketed in the 1980s to prevent gastric ulcers1. Misoprostol, as a synthetic prostaglandin E1 analogue, is commonly used in obstetrical and gynecological diseases and has been widely used in abortion, cervical maturation, induced labour and postpartum hemorrhage2. The administration routes include oral, vaginal, rectal, or sublingual2,3. Vaginal misoprostol was a more effective option for cervical maturation and induced labor, but it had more maternal and neonatal complications4. Oral misoprostol caused fewer tachysystole than vaginal misoprostol and might reduce the occurrence of cesarean Sections5. Sublingual administration of misoprostol shortened delivery time without increasing related complications, and appeared to be superior to oral and vaginal routes6.

Misoprostol could cause uterine smooth muscle fibers to contract and cervical relaxation7. In terminating pregnancy, mifepristone was often combined with misoprostol1. The study showed that terminating pregnancy at home using misoprostol alone was also effective, safe and acceptable8,9. Even if the pregnancy was extended, the success rate was more than 95%9. In terms of fertility after abortion, misoprostol treatment was comparable to expected treatment10. Oral misoprostol was a safe choice for term prelabor rupture of the membranes (TPROM) induction, and the occurrence of adverse reactions could be reduced by adjusting the dose and frequency of administration11. Due to its low price, room temperature storage, and long shelf life, misoprostol was widely available worldwide12,13. Moreover, misoprostol could also be used to treat asthma and protect heart tissue from damage caused by paclitaxel and doxorubicin14,15,16.

The common adverse reactions of misoprostol included nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, dizziness, etc.17. Some studies showed that misoprostol could cause cervical laceration, tachysystole, and uterine rupture in pregnant women18,19,20,21. In addition, the teratogenic risks of misoprostol also need to be taken seriously. Many studies showed that it could lead to fetal complications such as hydrocephalus, Moebius Syndrome, Holoprosencephaly, cleft lip and paddle, and brainstorm ischaemia, etc.22,23,24,25. However, the number of studies on misoprostol is limited, and there is currently a lack of comprehensive research on adverse reactions related to misoprostol.

Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation of the safety of misoprostol is necessary. By analyzing the FAERS data, adverse events (AEs) related to misoprostol were obtained. Doctors can understand the safety issues of misoprostol based on this. When using this drug in clinical practice, they can weigh the pros and cons, determine a better treatment plan, and seek greater benefits for patients.

Materials and methods

Data source

The FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) is a database that includes reports of adverse drug events, medication errors, and more, updated quarterly26. The FAERS database receives voluntary reports from healthcare professionals, consumers and manufacturers26. We searched for American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) report files from the first quarter of 2004 to the second quarter of 2024, taking into account the time of market launch of misoprostol and the time of public data release from the FAERS database. Each ASCII file contains seven aspects of content, including Patient Demographic and Administrative Info (DEMO), DRUG (Drug/Biologic Info), MedDRA Terms for Adverse Event (REAC), Patient Outcomes (OUTC), Report Sources (RPSR), Drug Therapy Start/End Dates (THER), and MedDRA Terms for Diagnoses/Indications (INDI).

Data extraction and analysis

We used the Medex_UIMA_1.3.8 system to standardize and unify drug names in the database. Data extraction was performed according to the drug name “misoprostol” and the drug must be the primary suspected (PS) drug. Deleting unrelated drugs or combination drugs, by specific keywords as follows: diclofe, naprosyn, mifepristone, eczema, naproxen, we obtained all drug information related to misoprostol. In addition, age groups were also divided as follows:<18, 18 ~ 55, 55 ~ 65,>=65. The measurement dates (days) for the occurrence time of adverse events were divided into the following: <7, 7 ~ 28, 28 ~ 60, >=60. Countries with a report count of ≥ 50 were presented. Reports of indications ≥ 30 were presented. In this study, the preferred term (PT) and system organ class (SOC) from the medical dictionary for regulatory activities (MedDRA26.1) were used to classify and describe signals of adverse events (AEs). We downloaded files from the FAERS database and removed duplicate records. For data with the same caseid in the DEMO table, only the most recent report based on the date was retained27. A single adverse event report may correspond to multiple adverse events. Some sum may not egaul the number of reports as they may be several items for one report as for exemple for outcomes.

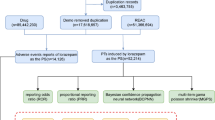

Disproportionality analysis is a commonly used method for detecting drug warning risk signals in the FAERS database. The principle of the disproportionality method is to compare the degree of imbalance between the target drug and adverse events and other drugs and adverse events, in order to evaluate the correlation between the target drug and adverse events28. According to different statistical principles, it can be divided into the frequency method and the Bayesian method28. Both methods are based on the four grid table (Supplementary table S1) to quantify the degree of imbalance between the target drug and adverse events, in order to identify potential pharmacovigilance risk signals28. Both methods have their own advantages and disadvantages, and there is currently no gold standard for them. The frequency method has high sensitivity but low specificity, and is easily affected by individual values28. The Bayesian method has high specificity and stable signals, but its sensitivity is average28. This study used the reporting odds ratio (ROR) and proportional reporting ratio (PRR) in the frequency method, as well as the Bayesian confidence propagation neural network (BCPNN) and empirical Bayes geometric mean (EBGM) methods in the Bayesian method to detect the signals of AEs. The formulas and thresholds of the four algorithms are shown in Supplementary table S2. When four algorithms simultaneously detect a signal, it is the signal determined in this study. The joint use of multiple algorithms allows for cross-validation to reduce false positives27. A higher value indicates a stronger signal strength, suggesting a stronger association between the target drug and adverse events27. All analyses were performed using R 4.3.1.

Results

Characteristics on adverse event reports related to misoprostol

We downloaded files from the first quarter of 2004 to the second quarter of 2024 in the FAERS database and deleted 3,435,092 duplicate records. For data with the same caseid in the DEMO table, only the most recent report based on the date was retained. This study obtained 17,427,762 adverse event reports from the FAERS database (Fig. 1). Among them, there were 2032 adverse events reports with misoprostol as the primary suspected (PS) drug (Fig. 1). The number of adverse events increased in recent years, peaking in 2020 (22.29%). From the perspective of gender distribution, females were the main group, accounting for 75.84%, while males accounted for 8.66%. In terms of age distribution, the incidence of adverse events was higher in the 18–55 age group (50.98%). Most of the reports were from consumers (38.98%), pharmacists (20.57%), and physicians (19.88%). The countries with the reports included Other (35.97%), Germany (22.29%), United States (18.65%), France (8.61%), China (4.87%), United Kingdom (3.69%), Italy (3.2%), and Denmark (2.71%) (top 8).

In terms of route of administration, oral (26.33%), transplacental (20.08%), and vaginal (16.88%) were common. As for serious outcomes, such as other serious (53.67%) and hospitalization (23.78%) were common. AEs occurred mainly within 7 days after medication (65.25%). The indications of misoprostol were mainly related to labour induction (27.65%) and abortion induced (23.13%). Please refer to Table 1; Figs. 1 and 2 for specific information. The number of adverse event reports for misoprostol per quarter was shown in Fig. 3.

Signals detection

Signals detection at SOC levels

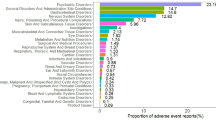

This study found that AEs associated with misoprostol mainly involved 23 system organ classes (SOCs) (Table 2). Among them, there were four systems that showed strong correlation with the four signal recognition methods, as follows: pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal conditions (n = 759, ROR 25.81, PRR 23.21, IC 4.53, EBGM 23.14), congenital, familial and genetic disorders (n = 150, ROR 6.51, PRR 6.4, IC 2.68, EBGM 6.39), injury, poisoning and procedural complications (n = 2114, ROR 3.87, PRR 3.03, IC 1.6, EBGM 3.03), and reproductive system and breast disorders (n = 236, ROR 3.85, PRR 3.76, IC 1.91, EBGM 3.76) (Table 2).

Signals detection at PTs level

The study ranked the top 30 PTs in descending order based on ROR (Table 3). The results showed that uterine tachysystole(n = 95, ROR 19203.92, PRR 18952.43, IC 12.32, EBGM 5103.31), abortion induced incomplete (n = 13, ROR 4546.76, PRR 4538.61, IC 11.43, EBGM 2751.07), foetal heart rate decreased(n = 93, ROR 1334.27, PRR 1317.18, IC 10.11, EBGM 1108.3), endometritis bacterial (n = 3, ROR 3492.68, PRR 3491.24, IC 11.18, EBGM 2327.83), and postpartum stress disorder (n = 9, ROR 6991.15, PRR 6982.48, IC 11.77, EBGM 3491.74) were high signals (Table 3). The most common AEs were foetal exposure during delivery(n = 201), uterine tachysystole(n = 95), uterine rupture (n = 95), and heart rate decreased(n = 93) (Table 3). In addition to the adverse reactions mentioned in the instructions, this study also discovered various congenital, familial and genetic disorders, such as congenital aqueductal stenosis and congenital brain damage (Table 3).

Discussion

Misoprostol was originally used to treat gastric ulcers, and had been widely used in abortion, cervical maturation, induced labour and postpartum hemorrhage1,2. In addition to the above indications, misoprostol also played a role in other areas. A study showed that the high-dose of misoprostol could relieve asthma by reducing IL-5 levels14. Animal experiments showed that misoprostol had antioxidant and anti-apoptotic effects and could protect rat heart from paclitaxel and doxorubicin damage15,16.

With more and more widely used, its adverse reactions have gradually attracted people’s attention. In addition to the common gastrointestinal adverse reactions, other adverse reactions such as skin reactions, tachysystole, uterine rupture, teratogenesis and so on were also increasing. Some pregnant women experienced erythroma multiforme and toxic epidermal necrolysis after taking misoprostol orally during termination of pregnancy29,30. 140 cases (31.4%) of women experienced tachystole after induction of labor using misoprostol20. A meta-analysis suggested that vaginal misoprostol led to a higher incidence of tachysystole [OR: 1.48;95% CI: 1.09–2.01]31. A 49 year old woman experienced sudden hypotension and subsequently developed anaphylactic shock while using misoprostol to promote cervical ripening before hysteroscopy32. Misoprostol could cause uterine rupture in primipara33. Some pregnant women continued pregnancy after oral misoprostol, exposing the fetus to misoprostol, which might lead to congenital abnormalities, such as: Hydrocephalus, Moebius Syndrome and Holoprosencephaly, neural tube defects, heart malformation, and cleft lip and palate, etc.22,23,24,34. A study in Brazil showed a positive correlation between misoprostol and congenital abnormalities, with fetuses exposed to misoprostol having a 2.74 times higher risk of developing congenital abnormalities compared to those not exposed35. However, another study in Brazil revealed that there was no evidence of a strong teratogenic effect of misoprostol exposure during pregnancy, and the risk of congenital abnormalities increased by misoprostol was very low36. This study systematically evaluated adverse events related to misoprostol through in-depth analysis of the FAERS database from the first quarter of 2004 to the second quarter of 2024. It provided more accurate data support for clinical practice and public health decision-making.

-

This study found that misoprostol related adverse events increased significantly in recent years and reached a peak in 2020, which might be due to the fact that patients were mainly at home during the COVID-19 period and their activity space was restricted. A study only using misoprostol for medical abortion from December 2020 to December 2021 showed that among the 911 patients included, up to 90% had complete abortion, and three patients experienced adverse events requiring blood transfusion37. A network pharmacology study revealed that the core therapeutic targets of misoprostol for terminating pregnancy were HSP90AA1, EGFR, and MAPK1, which interfered with protein phosphorylation, cell localization, and protein hydrolysis regulation processes through the VEGF signaling pathway, calcium signaling pathway, and NF-κB signaling pathway38.

-

Misoprostol related AEs were more common in female patients because this drug was currently widely used to treat gynecological and obstetric diseases. Misoprostol was used in patients aged 18–55 years and was mostly used in adult women of reproductive age, which was in line with its current widely used indications. Most of the reports were from consumers, indicating that patients were more inclined to report adverse reactions directly after using misoprostol and had a higher level of awareness. Except other countries, the countries with more reports were Germany and the United States, which indicated that economically developed countries might pay more attention to adverse drug reactions, which was also conducive to other countries to strengthen their attention to adverse drug reactions. The main routes of administration for misoprostol were oral, transplacetal, and vaginal. Oral misoprostol induced labor was superior to vaginal administration in neonatal death, tachysystole, and preeclampsia, and had fewer adverse reactions in pregnant women and newborns39. The main indications were Labour induction and Abortion induced, which were consistent with the clinical indications of misoprostol. The common outcomes of taking misoprostol were hospitalization (23.78%), life threatening (7.94%), and death (6.07%), indicating that the adverse reactions of misoprostol should be taken seriously by both doctors and patients.

Misoprostol, as a commonly used drug in obstetrics and gynecology, had AEs mainly concentrated in pregnancy, puerperium and peripheral conditions, congenital, familial and genetic disorders, injury, poisoning and procedural complexes, and reproductive system and breast disorders, among other SOCs, and most of them were included in the drug instructions, indicating the reliability of the results of this study. At the PTs level, The most common AEs were foetal exposure during delivery (n = 201), uterine tachysystole (n = 95), uterine rupture (n = 95) and foetal heart rate decreased (n= 93), partially consistent with the drug instructions and previous studies. After using misoprostol for cervical maturation, 32% of patients experienced fetal heart tracin abnormalities, and three cases of tachystole and two cases of pelvic abruption occurred40. Oral or vaginal misoprostol could cause uterine rupture during induced abortion, and women with a history of cesarean section were more likely to experience uterine rupture41,42,43. About 15% of misoprostol induced abortions might fail, leading to fetal exposure to the drug and potentially inducing birth defects44. A meta-analysis showed that the use of misoprostol increased the risk of congenital malformations (OR = 3.56; 95% CI: 0.98–12.98), and prenatal exposure to misoprostol was associated with an increased risk of Mobius sequence and terminal transverse limb defects45. A study suggested that congenital malformations in Brazilian children were associated with abuse of misoprostol in early pregnancy25.

In addition, this study also found adverse events that were not documented in the drug instructions, such as postpartum hypopituitarism, postpartum stress disorder, amniocentesis abnormal, endometritis bacterial, and anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy. No literature reports have been found on misoprostol and postpartum hypopituitarism, postpartum stress disorder, and amniocentesis abnormal. Medical abortion could lead to endometritis. Two young women underwent a combination of mifepristone and misoprostol medical abortion in early pregnancy46,47. After the abortion, they showed symptoms of infection46,47. Gram positive cocci and pyogenic streptococcus (Group A streptococcus) were cultured in the uterine trophoblast tissue, which might be caused by endouterine migration from a preexisting colonization of the vaginal flora or exogenous contamination during the procedure46,47. Relevant prevention and hygiene measures were crucial46,47. Four deaths associated with C. sordellii endometritis and toxic shock syndrome occurred within one week after medically induced abortions48. Clinically, doctors should enhance their understanding of this clinical manifestation and conduct in-depth research on its relationship with medical abortion48. Anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy was previously referred to as amniotic fluid embolism. A 27 year old primiparous woman developed amniotic fluid embolism after vaginal misoprostol to enhance uterine contractions, but unfortunately passed away despite all efforts to save her49. Another 26 year old primiparous woman experienced amniotic fluid embolism after vaginal misoprostol to promote cervical maturation and induce uterine contractions50. After rescue, the patient turned danger into safety50. These suggested that clinical training for medical staff should be strengthened to timely detect early symptoms of amniotic fluid embolism, treat them as soon as possible, and reduce maternal mortality49. In addition, the hospital’s obstetrics ward, blood bank, and operating room should meet the needs of rescuing patients49. These AEs all showed high signals, revealing their potential risk information. Adverse events that were not recorded in the instructions but were considered high signal in this study should be taken seriously by clinical doctors to reduce potential adverse outcomes in clinical practice.

This study provided strong support for the safety of misoprostol by analyzing real-world data in detail through the FAERS database. However, this study still had some limitations. Firstly, spontaneous reporting could lead to data bias, and the data provided by healthcare professionals might be more comprehensive and reliable than data from other sources. Secondly, the submitted report might not be detailed enough and might not accurately assess adverse events. It was also impossible to calculate the incidence of adverse events. Besides, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency released a Drug Safety Update on Misoprostol on 6 February 2018, as follows: monitor patients closely and remove the vaginal delivery system immediately in cases of excessive or prolonged uterine contractions at the onset of labour, or if there is clinical concern for mother or baby51. The safety alerts of misoprostol might affect its use in obstetrics. Also, this study did not conduct sensitivity analysis on pooled indications at HLT levels of MedDRA. The lack of sensitivity analysis with a reference group containing only drugs with the same indicators was also the limitation of this study. In addition, multiple testing could accumulate the possibility of false positives, leading to an overall increase in error rates. Furthermore, we were unable to conduct a case review of reports and verify the signals. Finally, the causal relationship between misoprostol and adverse events could not be determined, and further studies were needed to explore the causal relationship. Despite these limitations, the results of this study had certain reference value for the clinical use of misoprostol by medical personnel.

Conclusion

This study analyzed the AEs data related to misoprostol in the FAERS database and found that most of the SOCs involved were included in the drug instructions, indicating the reliability of the results of this study. This study also found adverse events that were not documented in the drug instructions, such as postpartum hypopituitarism, postpartum stress disorder, amniocentesis abnormal, anaphylactoid syndrome of pregnancy, and endometritis bacterial. These AEs all showed high signals, revealing their potential risk information. Clinicians should make appropriate evaluation when using misoprostol, closely monitor the indicators of patients, and have appropriate countermeasures for possible adverse events.

Data availability

The study used data from the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) database. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the corresponding author, without undue reservation.

References

Tang, J., Kapp, N., Dragoman, M. & de Souza, J. P. WHO recommendations for misoprostol use for obstetric and gynecologic indications. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 121, 186–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.12.009 (2013).

Kumar, N., Haas, D. M. & Weeks, A. D. Misoprostol for labour induction. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 77, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2021.09.003 (2021).

Tang, O. S., Gemzell-Danielsson, K. & Ho, P. C. Misoprostol: Pharmacokinetic profiles, effects on the uterus and side-effects. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 99(Suppl 2), S160-167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.09.004 (2007).

Hofmeyr GJ, Gülmezoglu AM. Vaginal misoprostol for cervical ripening and induction of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. CD000941. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000941 (2003).

Sheibani, L. & Wing, D. A. A safety review of medications used for labour induction. Expert Opin. Drug Saf. 17, 161–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/14740338.2018.1404573 (2018).

Pergialiotis, V. et al. Efficacy and safety of oral and sublingual versus vaginal misoprostol for induction of labour: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol. Obstet. 308, 727–775. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-022-06867-9 (2023).

Mifegymiso (mifepristone): 200 mg tablet [product monograph]. London [UK]: Linepharma International Limited, accessed 28 August 2024; https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00042704.PDF (2017).

Raymond, E. G., Weaver, M. A. & Shochet, T. Effectiveness and safety of misoprostol-only for first-trimester medication abortion: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Contraception 127, 110132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2023.110132 (2023).

Podolskyi, V., Gemzell-Danielsson, K., Maltzman, L. L. & Marions, L. Effectiveness and acceptability of home use of misoprostol for medical abortion up to 10 weeks of pregnancy. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 102, 541–548. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.14549 (2023).

Fernlund, A., Jokubkiene, L., Sladkevicius, P. & Valentin, L. Reproductive outcome after early miscarriage: Comparing vaginal misoprostol treatment with expectant management in a planned secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 59, 100–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.24769 (2022).

Padayachee, L., Kale, M., Mannerfeldt, J. & Metcalfe, A. Oral misoprostol for induction of labour in term PROM: A systematic review. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 42, 1525-1531.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2020.02.111 (2020).

Bakker, R., Pierce, S. & Myers, D. The role of prostaglandins E1 and E2, dinoprostone, and misoprostol in cervical ripening and the induction of labor: A mechanistic approach. Arch Gynecol. Obstet. 296, 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-017-4418-5 (2017).

Berghella, V. & Bellussi, F. Misoprostol before surgical abortion: Evidence-based and ready to be incorporated in clinical guidelines to change practice. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2, 100254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2020.100254 (2020).

Sheller, J., Dworski, R., Hagaman, D., Oates, J. & Murray, J. The prostaglandin E agonist, misoprostol, inhibits airway IL-5 production in atopic asthmatics. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 70, 185–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00065-5 (2002).

Aktaş, İ, Gur, F. M. & Bilgiç, S. Protective effect of misoprostol against paclitaxel-induced cardiac damage in rats. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 171, 106813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2024.106813 (2024).

Bilgic, S., Ozgocmen, M., Ozer, M. K. & Asci, H. Misoprostol ameliorates doxorubicin induced cardiac damage by decreasing oxidative stress and apoptosis in rats. Biotech. Histochem. 95, 514–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/10520295.2020.1727013 (2020).

Practice Bulletins—Gynecology, the Society of Family Planning. Medication abortion up to 70 days of gestation. Contraception 102, 225–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2020.08.004 (2020).

Oyelese, Y., Landy, H. J. & Collea, J. V. Cervical laceration associated with misoprostol induction. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 73, 161–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7292(00)00372-6 (2001).

Pevzner, L., Alfirevic, Z., Powers, B. L. & Wing, D. A. Cardiotocographic abnormalities associated with misoprostol and dinoprostone cervical ripening and labor induction. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 156, 144–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.01.015 (2011).

Sichitiu, J., Vial, Y., Panchaud, A., Baud, D. & Desseauve, D. Tachysystole and risk of cesarean section after labor induction using misoprostol: A cohort study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 249, 54–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.04.026 (2020).

Kim, J. O. et al. Oral misoprostol and uterine rupture in the first trimester of pregnancy: A case report. Reprod. Toxicol. 20, 575–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2005.04.014 (2005).

Beuriat, P. A. et al. Isolated antenatal hydrocephalus after fetal exposure to misoprostol: Teratogenic effect of the cytotec?. World Neurosurg. 124, 98–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.12.177 (2019).

Pirmez, R., Freitas, M. E., Gasparetto, E. L. & Araújo, A. P. Moebius syndrome and holoprosencephaly following exposure to misoprostol. Pediatr. Neurol. 43, 371–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2010.05.026 (2010).

Vendramini-Pittoli, S., Guion-Almeida, M. L., Richieri-Costa, A., Santos, J. M. & Kokitsu-Nakata, N. M. Clinical findings in children with congenital anomalies and misoprostol intrauterine exposure: A study of 38 cases. J. Pediatr. Genet. 2, 173–180. https://doi.org/10.3233/PGE-13066 (2013).

Gonzalez, C. H. et al. Congenital abnormalities in Brazilian children associated with misoprostol misuse in first trimester of pregnancy. Lancet 351, 1624–1627. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(97)12363-7 (1998).

FAERS. Accessed 28 August 2024; https://www.fda.gov/drugs/surveillance/questions-and-answers-fdas-adverse-event-reporting-system-faers.

Jiang, Y. et al. Safety assessment of Brexpiprazole: Real-world adverse event analysis from the FAERS database. J. Affect. Disord. 346, 223–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.11.025 (2024).

Zhou, S. S. et al. Application of adverse drug reaction of data mining in pharmacovigilance. Chin. J. Mod. Appl. Pharmacy 06, 864–870 (2024).

Sahraei, Z., Mirabzadeh, M. & Eshraghi, A. Erythema multiforme associated with misoprostol: A case report. Am. J. Ther. 23, e1230–e1233. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0000000000000193 (2016).

Frezgi, O. & Russom, M. Toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with misoprostol: A case report. Int. Med. Case Rep. J. 16, 385–390. https://doi.org/10.2147/IMCRJ.S408342 (2023).

Taliento, C. et al. Safety of misoprostol vs dinoprostone for induction of labor: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 289, 108–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2023.08.382 (2023).

Shin, H. J. et al. Anaphylactic shock to vaginal misoprostol: A rare adverse reaction to a frequently used drug. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 61, 636–640. https://doi.org/10.5468/ogs.2018.61.5.636 (2018).

Thomas, A., Jophy, R., Maskhar, A. & Thomas, R. K. Uterine rupture in a primigravida with misoprostol used for induction of labour. BJOG 110, 217–218 (2003).

Brasil, R., Lutéscia Coelho, H., D’Avanzo, B. & La Vecchia, C. Misoprostol and congenital anomalies. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 9, 401–403. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1557(200009/10)9:5%3c401::AID-PDS527%3e3.0.CO;2-1 (2000).

Dal Pizzol, T. S., Sanseverino, M. T. & Mengue, S. S. Exposure to misoprostol and hormones during pregnancy and risk of congenital anomalies. Cad Saude Publica 24, 1447–1453. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0102-311x2008000600025 (2008).

Schüler, L. et al. Pregnancy outcome after exposure to misoprostol in Brazil: A prospective, controlled study. Reprod. Toxicol. 13, 147–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0890-6238(98)00072-0 (1999).

Raymond, E. G. et al. Clinical outcomes of medication abortion using misoprostol-only: A retrospective chart review at an abortion provider organization in the United States. Contraception 126, 110109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.contraception.2023.110109 (2023).

Zhang, R. et al. Multi-target mechanism of misoprostol in pregnancy termination based on network pharmacology and molecular docking. Afr. J. Reprod. Health 28, 114–121. https://doi.org/10.29063/ajrh2024/v28i3.12 (2024).

Rahimi, M. et al. Comparison of the effect of oral and vaginal misoprostol on labor induction: Updating a systematic review and meta-analysis of interventional studies. Eur. J. Med. Res. 28, 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-023-01007-8 (2023).

Kandahari, N., Tucker, L. S., Schneider, A. N., Raine-Bennett, T. R. & Mohta, V. J. Fetal heart rate patterns and the incidence of adverse events after oral misoprostol administration for cervical ripening among low-risk pregnancies. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 36, 2199344. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2023.2199344 (2023).

Khosla, A. H., Sirohiwal, D. & Sangwan, K. A still birth and uterine rupture during induction of labour with oral misoprostol. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 42, 412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0004-8666.2002.409_4.x (2002).

Bennett, B. B. Uterine rupture during induction of labor at term with intravaginal misoprostol. Obstet. Gynecol. 89, 832–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00036-7 (1997).

Aslan, H., Unlu, E., Agar, M. & Ceylan, Y. Uterine rupture associated with misoprostol labor induction in women with previous cesarean delivery. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 113, 45–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0301-2115(03)00363-4 (2004).

Cavieres, M. F. Toxicidad del misoprostol sobre la gestación: Revisión de la literatura [Developmental toxicity of misoprostol: an update]. Rev. Med. Chil. 139, 516–523 (2011).

da Silva Dal Pizzol, T., Knop, F. P. & Mengue, S. S. Prenatal exposure to misoprostol and congenital anomalies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Reprod. Toxicol. 22, 666–671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2006.03.015 (2006).

Zhang, Y. et al. Chemical fingerprint analysis and ultra-performance liquid chromatography quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry-based metabolomics study of the protective effect of Buxue Yimu Granule in medical-induced incomplete abortion rats. Front. Pharmacol. 11, 578217. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2020.578217 (2020).

Gendron, N. et al. Group A Streptococcus endometritis following medical abortion. J. Clin. Microbiol. 52, 2733–2735. https://doi.org/10.1128/JCM.00711-14 (2014).

Fischer, M. et al. Fatal toxic shock syndrome associated with Clostridium sordellii after medical abortion. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 2352–2360. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa051620 (2005).

Yang, J. Analysis of one case of death caused by atypical amniotic fluid embolism during full-term induced labor with misoprostol. Chin. J. Misdiagn. 34, 8446 (2011).

Jia, X. Q. One case of delayed amniotic fluid embolism complicated with DIC caused by misoprostol induced labor. Shaanxi Med. J. 07, 871 (2010).

GOV.UK. Accessed Nov 21, 2024; https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/misoprostol-vaginal-delivery-system-mysodelle-reports-of-excessive-uterine-contractions-tachysystole-unresponsive-to-tocolytic-treatment.

Funding

This study was supported by the Gusu Health Talent Plan Research Project (No.GSWS2023016); the Science and Technology Development Plan of Suzhou (No.SLT2022012, SKYD2022010); School-Land Collaborative Innovation Research Project of Jiangsu Pharmaceutical Vocational College (No.20239602); and the Youth Natural Science Foundation of Zhangjiagang TCM Hospital Affiliated to Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine (No. ZZYQ2206).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: LY and WTX. Data analysis: LY. Interpretation of the data and drafingthe paper: LY and WTX. Critical revision of the paper for intellectual content: WTX. Writing review and editing work: WTX. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, L., Xu, W. A disproportionality analysis of FDA adverse event reporting system events for misoprostol. Sci Rep 15, 2452 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86422-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86422-z

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Drug-associated postpartum hemorrhage: a comprehensive disproportionality analysis based on the FAERS database

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology (2025)