Abstract

Squeezed states of light, generated through four-wave mixing (FWM), are increasingly recognized as valuable resources for various applications in quantum sensing, quantum imaging, and quantum information processing. In this study, we report achieving more than − 7.8 dB of intensity-difference squeezing (IDS) in two-mode squeezed states from hot 85Rb vapor and − 5.0 dB from hot 87Rb vapor, utilizing a fiber electro-optic modulator (EOM) within a single home-made diode laser system. By mitigating the effects of undesired multimode from the EOM on the squeezing, we experimentally demonstrated the IDS of 85Rb and 87Rb atoms within a single experimental setup, benefiting from the EOM’s ability to provide higher frequency shifts. This advancement may expand the scope of applications for hot atomic-vapor-based quantum technologies, leveraging the capabilities of the EOM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Quantum light sources generated from warm atomic ensembles have garnered significant attention as essential resources for advancing photonic quantum science and technologies1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Notably, the generation of nonclassical light through the spontaneous four-wave mixing process in atomic ensembles has been successfully demonstrated through several pivotal quantum optics experiments. These include time-resolved Hong–Ou–Mandel interference, high-visibility Franson interference of time-energy entangled photon pairs, the generation of hyper-entangled photon pairs, four-photon Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger (GHZ) entanglement, and the entanglement swapping of photon-polarization qubits12,13,14,15,16,17.

Squeezed states of light have been developed as promising resources for various applications18,19,20,21,22,23. Among the various methods for generating squeezed states, four-wave mixing (FWM) in hot atomic vapor has garnered significant attention due to its distinct advantages. Compared to conventional methods, such as those employing nonlinear crystals, the FWM approach offers unique benefits that address specific limitations of traditional techniques. Nonlinear crystals, such as those used in optical parametric oscillators (OPOs), are well-established for achieving high squeezing levels, often exceeding 10 dB. Notably, the wavelength and bandwidth of squeezed states produced via the FWM process are inherently compatible with atomic transitions, a critical characteristic for applications in quantum sensing and quantum memory. Additionally, the FWM process from a dense atomic ensemble with a single laser source exhibits significant nonlinearities, which facilitate the generation of strong quantum correlations and entanglement without the requirement for an optical cavity24,25.

Squeezed states of light are highly advantageous for quantum sensing due to their ability to reduce quantum noise below the standard quantum limit in a specific quadrature25,26. This noise reduction enhances measurement sensitivity, making it possible to detect minute changes in physical parameters with unprecedented precision. In atomic magnetometry, squeezed light can improve the sensitivity of magnetic field measurements by reducing noise in the measurement process, allowing the quantum magnetic gradiometer with sub-shot-noise sensitivity using entangled twin beams with differential detection27. The enhanced quantum correlations inherent to squeezed states also contribute to their utility in scenarios requiring precise phase measurements, such as gravitational wave detection18 or optical interferometry28. These applications benefit from the ability of squeezed light to surpass classical noise limits, thereby achieving higher resolution and accuracy. The squeezed states from hot atomic vapor systems have been utilized in various applications, including quantum sensing27,28,29,30,31,32, quantum imaging33,34, and quantum information processing35,36,37,38,39,40.

The generation of squeezed states via FWM in hot atomic vapor systems has been effectively realized using a so-called double-Λ scheme, interacting with the pump and probe-seed beams generated from a single, narrow-linewidth high-power CW Ti-Sapphire laser system. This configuration effectively circumvents fundamental limitations such as spontaneous emission and absorption, while taking advantage of the significant nonlinearities inherent in the process41. Such efficient and large nonlinearity is crucial for producing robust squeezing42,43. To achieve high-quality, frequency-shifted single-mode beams, which are critical for efficient squeezed state generation, these studies commonly rely on acousto-optic modulators (AOMs). However, most research on the generation and application of squeezed states from hot atomic vapor has focused on 85Rb, largely because AOM-based setups exclude atomic species with larger hyperfine structures, such as 133Cs and 87Rb. These species are of particular interest due to their potential for enhanced quantum memory performance and stronger atomic interactions, which could lead to more robust quantum correlations and improved squeezed state generation.

By utilizing an electro-optic modulator (EOM), for the first time, quantum-correlated twin beams with a maximum intensity-difference squeezing of 6.5 dB have been generated in hot cesium vapor44. It is possible to generate and utilize squeezed states of light from a broader range of atomic species due to the significantly higher efficiency of diffraction (on the order of 10%) at much larger frequency shifts (up to tens of GHz), while maintaining very good phase-locking44. Despite these notable advantages, the integration of EOMs in hot atomic vapor systems for squeezing applications has been largely unexplored. This is primarily because the probe-seed frequency component modulated by the EOM spatially overlaps with the pump laser beam. While the scanning range of an AOM is smaller than that of an EOM, the multimode effects from EOMs can influence the squeezing process. The choice of AOM for many squeezing experiments was based on specific experimental requirements, rather than a lack of alternative options. However, the impact of undesired modes arising from the probe-seed frequency component modulated by the EOM on squeezing has not yet been experimentally investigated.

In this work, we experimentally demonstrate that utilizing a fiber EOM integrated within a home-made diode laser system enables more than − 7.8 dB of intensity-difference squeezing (IDS) from FWM in hot 85Rb vapor. To the best of our knowledge, this is the best squeezing achieved in diode-laser-pumped twin beam systems, highlighting the potential of EOM-based systems to produce robust squeezing comparable to AOM-based systems42,45. Leveraging the capabilities of this EOM-based system, we investigate the gain spectra of probe and conjugate beams in 85Rb and 87Rb and also generate 5.0 dB of IDS in hot 87Rb vapor using the same setup. Additionally, we investigate the effects of undesired multimode contributions on squeezing.

Experimental schematic

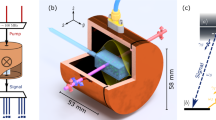

Figure 1(a) shows the experimental setup in detail. A home-made external cavity diode laser (ECDL) generates a 795 nm beam near the D1 transition line of rubidium isotopes 85Rb and 87Rb. This beam is then introduced into a home-made master oscillator power amplifier (MOPA) system with a tapered amplifier, which amplifies the ECDL beam’s power after spatial mode-cleaning by a single-mode fiber (SMF). Since large detuning, in the range of 3 to 6.8 GHz, is required for the double-Λ scheme as shown in Fig. 1(b), a high-power pump beam, typically between 400 and 700 mW, is necessary42,43,44,45. While the amplified beam is mostly used as a pump beam directed into the vapor cell, a small fraction of this beam is picked off via a polarizing beam splitter (PBS) into a fiber EOM (model: EOSPACE AZ-0S5-10-PFA-PFA-780-UL), producing a weak probe-seed beam detuned by 3.036–6.835 GHz to the red-detuning of the pump beam, alongside other undesired multimodes (such as the frequency components of the pump laser). To suppress these undesired multimodes, we use a spectral filtering system consisting of three sequential etalon filters. In our experiment, the etalon filters have a full width at half maximum linewidth of 950 MHz, free spectral range of 17 GHz, and 85% peak transmission. Prior to entering the vapor cell, both the pump and probe-seed beams pass through two 4F systems equipped with twin lenses (L1-L2 and L3-L4), which adjust the beam waists and loosely focus the beams at the vapor cell. The beams are then combined via a PBS and directed into isotopically pure Rb cells, 85Rb and 87Rb, each 12.5 mm in length, heated to approximately 121 ℃ and 131 ℃, respectively. At the center of the vapor cell, the beam waists for the pump and probe-seed are 530 μm and 330 μm (1/e2 radius) with a power of 600 mW and 10 µW, respectively. This configuration ensures overlap throughout the cell while the pump intensity is strong enough for the FWM process.

(a) Schematic of the experimental setup utilized for generating IDS. ECDL, external-cavity diode laser; OI, optical isolator; HWP, half-wave plate; MOPA, master-oscillator power amplifier; CL, cylindrical lens; PBS, polarizing beam splitter; FC, fiber collimator; L, lens; BB, beam blocker; BPD, balanced photodetector; SA, spectrum analyzer. (b) Energy level diagram of the double-Λ system associated with the D1 transition line of rubidium, illustrating the experimental generation and detection of the squeezed state of light via FWM. νHF, hyperfine splitting; Δ, one-photon detuning; δ, two-photon detuning; DM, D-shaped mirror. The FWM process occurs within a heated Rb vapor cell where two beams, the pump and probe-seed, intersect at a small cross-angle. After polarization and spatial filtering to eliminate the pump beam, the resulting FWM twin beams are detected by the BPD. The output from the BPD is subsequently analyzed by a radio frequency SA.

In the FWM process within a double-Λ scheme, the pump fields are parametrically converted into probe (Stokes) and conjugate (anti-Stokes) fields, as shown in Fig. 1(b). To maintain strong quantum correlations between the twin beams, the probe and conjugate, it is essential to avoid undesired nonlinear processes while achieving high FWM gain. In order to achieve it, we need to use both one-photon detuning (Δ) and two-photon detuning (δ)46. The probe-seed beam is introduced at a small phase-matching angle (θ ≈ 0.32°) relative to the pump beam, where maximum squeezing is observed. In this process, the probe and conjugate beams are jointly amplified; the probe beam is amplified, exhibiting the FWM gain feature, while the conjugate beam is generated. In effective phase matching, the conjugate beam propagates at approximately the same angle of ~ 0.32° with respect to the propagating direction of the pump beam.

The intensity-difference squeezing of the generated twin beams is measured by a balanced photodetector (BPD) with a transimpedance gain of 105 V/A. A crucial step prior to detection is filtering out pump scattering, which significantly limits squeezing efficiency in our scheme. This is accomplished through a two-stage filtering process. Initially, polarization filtering is employed using a PBS with an extinction ratio of approximately 3000:1 to effectively remove the pump light. Subsequently, spatial filtering is conducted using a D-shaped mirror, which selectively isolates the FWM twin beams and further separates them from the pump beam, thereby minimizing pump scattering. The twin beams are then routed to the BPD. The output from the BPD is analyzed using a radio-frequency spectrum analyzer (SA) equipped with a resolution bandwidth (RBW) of 30 kHz and a video bandwidth (VBW) of 300 Hz. To measure the standard quantum limit (SQL) of our system, we divert the pump beam prior to the cell and measure the intensity-difference noise between two coherent beams, separated by a 50:50 beam splitter. Since the SQL in our experimental system is determined by Poisson noise, the noise spectrum of the SQL in SA should be frequency-independent and scale linearly with optical power, which is clearly shown in our data.

Gain spectra of probe and conjugate beams in 85Rb and 87Rb

In 85Rb, the conditions optimized for squeezing are a cell temperature of 121 ℃, a one-photon detuning of ≈ 0.9 GHz, and a two-photon detuning of -8 MHz. We defined the FWM gain as the relative amplified value of the output power to the input power of the probe-seed beam. The FWM parametric gain features under these conditions are shown in Fig. 2(a). When the probe-seed beam is scanned and its transmission is observed, a strong gain of about 16 is featured at 3 GHz red and blue detuning from the pump, with the power of the probe-seed normalized. Ideally, this indicates that the resulting probe beam comprises 94% of a correlated beam and roughly 6% of an uncorrelated coherent probe-seed beam. This relationship can be expressed simply as \(\:{P}_{\text{p}}=G{P}_{0}\) and \(\:{P}_{\text{c}}=\left(G-1\right){P}_{0}\) where \(\:{P}_{\text{p}}\): probe power, \(\:{P}_{\text{c}}\): conjugate power, \(\:{P}_{0}\): probe-seed power, and \(\:G\): FWM gain42. Consequently, there is a reduction in quantum noise by a factor of \(\:1/\left(2G-1\right)\) compared to the SQL at the given output optical power. The dispersive character of the redder FWM gain peak arises from the interplay between Raman absorption, electromagnetically induced transparency, and FWM gain43.

It is observed that the FWM gain at a probe-seed detuning of + 3.036 GHz is stronger than that of -3.036 GHz (relative to the pump detuning). However, under the condition of a probe-seed detuning of + 3.036 GHz, the conjugate beam experiences absorption near the resonance, resulting in a larger discrepancy in the gain between the probe (Fig. 2(a)) and the conjugate (Fig. 2(b)). Consequently, such discrepancies lead to a significant reduction in squeezing. To achieve high-quality squeezing, the gains of the twin beams need to be closely matched. During our experiments, we deliberately allow the probe-seed beam to be absorbed by slightly adjusting the two-photon detuning. This approach is effective in noisy systems like ours for suppressing additional noise introduced by the probe-seed beam.

Leveraging the advantage of an EOM for higher frequency shifts, we investigate squeezing in 87Rb using the same system. In addition to the larger detuning of the probe-seed beam for the D1 line (νHF = 6.834 GHz), we need to adjust several parameters: one-photon detuning (Δ), two-photon detuning (δ), and temperature (T). In our experiment, we found maximum squeezing in 87Rb under the conditions of Δ ≈ 1.3 GHz, δ = -11 MHz, and T ≈ 131 ℃. The blue traces in Fig. 2 show the parametric gain features of the FWM twin beams under these conditions. We observe a gain of approximately 12 for a probe-seed red-detuning of 6.834 GHz relative to the pump frequency and around 9 for the blue-detuning of 6.834 GHz. Similar to the 85Rb case, the squeezing is significantly reduced at a probe-seed blue-detuning of 6.835 GHz relative to the pump frequency.

(a) Probe transmission and (b) generated conjugate beam spectra obtained by frequency-scanning the probe-seed in 85Rb (red curves) and 87Rb (blue curves) atoms. For 85Rb, besides the linear absorption, a narrow and strong parametric gain feature is observed at ± 3.036 GHz relative to the pump frequency, set at 0.9 GHz towards the blue-detuning from the 85Rb 5S1/2, F = 2 to 5P1/2, F = 3 transition. Similarly, for 87Rb, in addition to the linear absorption, distinct parametric gain features are observed at ± 6.835 GHz from the pump frequency, which is tuned to 1.3 GHz blue-detuned from the 87Rb 5S1/2, F = 1 to 5P1/2, F = 2 transition.

Squeezing in 85Rb and 87Rb

Figure 3 shows the successful measurement of -7.8 dB of IDS in the low-frequency domain from 40 to 500 kHz in 85Rb, with a squeezing bandwidth of approximately 3.5 MHz, under the conditions of a pump power of 600 mW and a probe-seed power of 8 µW. The probe beam is amplified to 111 µW (gain ≈ 15), and the conjugate beam is generated with a power of 109 µW, resulting in a total optical power of 220 µW. We find that the noise peak near 2 MHz originates from electronic noise in a laser source. The observed reduction in squeezing levels at higher frequencies can be attributed to several factors. First, we observe that the squeezing bandwidth varies with the one-photon detuning, which is directly related to slow-light delay and absorption42. Second, the relative phase instability between the pump and probe-seed decreases the squeezing bandwidth44. Third is the spectral response range of the BPD, determined by the transimpedance gain, as indicated by the electronic background noise, as shown in Fig. 3(a). Lastly, unlike the squeezing in twin beams from an optical parametric oscillator, which amplifies vacuum states, our system requires consideration of the noise inherent in the probe-seed beam. If the probe-seed beam is not shot-noise-limited and exhibits additional noise, this probe-seed noise affects the output IDS signal45.

In order to quantify the degree of squeezing and check the contribution of system noise, we vary the probe-seed power and measure the intensity-difference noise between the twin beams from the FWM process. Figure 3(b) shows the SQL of our experimental system as a function of total optical power. As the intensity-difference noise is jointly amplified in the FWM process, the proportion of correlated noise relative to the SQL reflects the degree of squeezing under ideal conditions, in the same sense as the quantum noise reduction of \(\:1/\left(2G-1\right)\). This correlation results in a reduction in the slope of the IDS compared to the SQL, as shown in Fig. 3(b). Thus, we estimate the degree of squeezing by comparing the slopes of SQL and IDS. The ratio of these slopes of the IDS to SQL as a function of the total optical powers is calculated to be 0.134, corresponding to about − 8.7 dB of IDS. From the directly measured squeezing degree of -7.8 dB in Fig. 3(a), the suppression due to the system noise is estimated to be ~ 0.9 dB. We attribute the main contributing factors of our system noise to pump scattering and the electronic noise of the detection system (refer to Fig. 3(a)). The optical and system losses are 5.5(2)% and 8.0(2)%, respectively, leading to a total detection loss of 13.5(2)%. This indicates that our results are nearing the maximum achievable degree of squeezing. Our experimental parameters are different from those of the Ref42. The two-photon detuning condition depends on other experimental parameters such as gain, optical depth, one-photon detuning, and phase-matching angle. We think that the cause of difference with the previous result is slightly different experimental conditions.

Observation of intensity-difference squeezing in the D1 line of 85Rb. (a) Intensity-difference noise spectra. Electronic, the electronic noise spectrum (black curve); pump, the pump scattering noise spectrum (gray curve); FWM, the intensity-difference squeezing spectrum (red curve); SQL, the standard quantum limit (blue curve). (b) Intensity-difference noise as a function of total optical power at an analysis frequency of 150 kHz; SQL (blue squares) and FWM (red circles). The ratio between the two slopes is calculated to be -8.7 dB.

Figure 4 shows the measured IDS from the generated FWM twin beams in 87Rb. We observed the maximum squeezing of -5.0 dB, under the conditions of the pump, probe, and conjugate powers set at 600 mW, 111 µW, and 109 µW, respectively, and a gain of approximately 10. Compared with the result in Fig. 3(a), the maximum squeezing occurs in the low-frequency domain but exhibits a lower degree of squeezing and narrower bandwidth, because of the collision noise and lower gain. Under our experimental conditions of a pump power of 600 mW and a cell temperature of 131 ℃, we could achieve a higher gain. However, this results in higher collision noise46 compared to the case with 85Rb at 121 ℃. The maximum degree of squeezing saturates near 121 ℃ and decreases beyond this temperature, reducing the squeezing bandwidth at the same time. However, if higher pump power is available, achieving higher gain at a lower temperature could lead to greater squeezing. The main reasons for the differences in the squeezing results and experimental parameters between 87Rb and 85Rb are different atomic properties such as hyperfine levels. Since 87Rb requires a larger detuning, its nonlinear susceptibilities are smaller than those of 85Rb, resulting in reduced FWM gain under the same conditions47. In our experiment, because the detuning condition for the FWM gain is important for optimal squeezing, the energy difference between hyperfine ground states affects the conditions of one-photon detuning (Δ) and two-photon detuning (δ). To achieve an FWM gain of ~ 10, we need to raise the temperature higher than for 85Rb, where collision-driven decoherence begins to dominate46. Furthermore, although we used an isotopically pure 87Rb cell, a minor fraction of 85Rb is present, as shown in Fig. 2(a). This residual 85Rb introduces additional absorption at the probe’s frequency for 87Rb squeezing, as discussed in48. This extra absorption reduces both the degree and the bandwidth of squeezing.

Observation of intensity-difference squeezing in the D1 line of 87Rb. (a) Intensity-difference noise spectra. Electronic, the electronic noise spectrum (black curve); pump, the pump scattering noise spectrum (gray curve); FWM, the intensity-difference squeezing spectrum (red curve); SQL, the standard quantum limit (blue curve). (b) Intensity-difference noise as a function of total optical power at an analysis frequency of 150 kHz; SQL (blue squares) and FWM (red circles). The calculated ratio of the two slopes is -6.1 dB.

Multimode effect on the squeezing

The probe-seed mode frequency component modulated by the fiber-EOM is spatially overlapped with the pump laser beam. The power of the carrier mode (residual pump mode), one of the undesired multimodes, is predominantly higher than all other multimodes, as shown in Fig. 5(a). To investigate the effect of undesired multimode (residual component of pump-mode frequency) originating from the fiber-EOM, therefore, we focus on the ratio of the residual pump-mode (carrier mode) to the desired probe-seed mode under the condition of our best squeezing. We measure the quantum noise spectra of the squeezing according to the ratio of the residual carrier mode to the probe-seed mode (Fig. 5(b)). A ratio of ≪ 0.5% is achievable only when using a spectral filtering system composed of three successive etalon filters, whereas a ratio of approximately 0.5% is achievable with two successive etalon filters. The other ratios are obtained by using spectral filtering with a single etalon filter.

Figure 5(b) shows the noise spectra according to the ratio of the carrier mode to the probe-seed mode, under the conditions of Fig. 5(a). As the ratio of the carrier mode increases, both the maximum degree of squeezing and the squeezing bandwidth decrease at the same time. The spectra clearly demonstrate the significant impact of the undesired multimode; even a small proportion of multimode (~ 0.5%) substantially affects the quantum noise characteristics of the squeezed state. Specifically, a multimode presence of only 0.5% results in a reduction of 0.8 GHz in the squeezing bandwidth compared to the case where the multimode ratio is ≪ 0.5%. Moreover, the presence of multimode introduces additional noise across all frequencies, leading to a reduction in the maximum degree of squeezing. Notably, we are able to observe squeezing as long as the ratio does not exceed 25%.

The residual component of pump-mode frequency originating from the fiber-EOM cannot be contributed to generate a conjugation beam of probe-seed mode, because of the phase-matching condition. Basically, the added coherent state \({\left| {\left. \alpha \right\rangle } \right._p}\) of the pump component in the spatial mode of the probe-seed can be explained by the rapid increase of the background noise. Therefore, the physical mechanism of this phenomenon about the decrease in squeezing is the increase in coherent photon noise according to the ratio of the residual carrier mode to the probe-seed mode.

Multimode effect on the squeezing. (a) Multimode spectra of the probe-seed beam. Each graph shows the spectrum for each specified ratio of the probe-seed mode (at -3 GHz, which is desired) to the carrier mode (at 0 GHz, which is undesired). Zero-detuning is set to the carrier frequency. Each graph is arranged by the ratio along the y-axis, while the power (z-axis) is normalized to the power of the desired probe-seed mode. (b) Observed IDS under the multimode effects. The electronic noise and pump scattering noise spectra are represented by black and grey traces, respectively. The IDS spectra corresponding to the probe-seed to multimode ratio of less than 0.5% (red), 0.5% (green), 12.5% (magenta), 25% (cyan), and 50% (yellow) are also shown. The blue dashed line represents the SQL, normalized to 0 dB.

To further quantify the effect of the undesired multimode, we investigate the intensity-difference noise power versus total optical power, following the same method as in Fig. 3(b). The ratios of the two slopes, FWM and SQL, in each case are 0.134, 0.589, and 0.964, corresponding to -8.7 dB, -2.3 dB, and − 0.16 dB, respectively (see Fig. 6(a)). Figure 6(b) shows the corresponding spectral mode characteristics for each case, with matching colors for clarity. These results reaffirm that the degree of squeezing significantly diminishes as the ratio of the multimode increases. Specifically, the degree of squeezing is reduced by a factor of four when the multimode ratio reaches 12.5%, and squeezing becomes barely perceptible at a ratio of 25%. Notably, as the ratio of the multimode increases, additional power-dependent noise is introduced, with the noise power increasing more than linearly. This trend becomes more pronounced at higher multimode ratios.

(a) Intensity-difference noise as a function of total optical power at an analysis frequency of 150 kHz. Blue squares, SQL; red circles, the probe-seed to multimode ratio of ≪ 0.5%; green triangles, 12.5%; and magenta inverted triangles, 25%. (b) Corresponding probe-seed beam spectra with each color trace representing different ratios of probe-seed to multimode when zero-detuning is set to the carrier: Red trace, the ratio of ≪ 0.5%; green trace, 12.5%; magenta trace, 25%.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have experimentally demonstrated the generation of intensity-difference squeezing with strong quantum correlations of over − 7.8 dB from 85Rb atoms and − 5.0 dB from 87Rb atoms using an EOM-based single diode laser pumping system. Our system leverages the high-efficiency frequency shift capability of the EOM. Our results indicate that our squeezing system, utilizing a home-made MOPA with ECDL and an EOM-based system, can achieve a quality of squeezing comparable to that obtained with Ti: sapphire lasers and AOM-based systems. Particularly, we have explored the impact of undesired multimode on the quality of squeezing. Given that our system utilizes both an EOM and a diode laser, our research has the potential to broaden the application of hot atomic-vapor-based quantum technologies in various fields that require the unique capabilities of EOMs.

Data availability

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Willis, R. T. et al. Correlated photon pairs generated from a warm atomic ensemble. Phys. Rev. A. 82(5), 053842 (2010).

Willis, R. T. et al. Photon statistics and polarization correlations at telecommunications wavelengths from a warm atomic ensemble. Opt. Express. 25, 14632–14641 (2011).

Ding, D. S. et al. Generation of non-classical correlated photon pairs via a ladder-ype atomic configuration: theory and experiment. Opt. Express. 20, 11433–11444 (2012).

Shu, C. et al. Subnatural-linewidth biphotons from a doppler-broadened hot atomic vapour cell. Nat. Commun. 7, 12783 (2016).

Lee, Y. S. et al. Highly bright photon-pair generation in Doppler-broadened ladder-type atomic system. Opt. Express. 24, 28083–28091 (2016).

Park, J., Kim, H. & Moon, H. S. Polarization-entangled photons from a warm atomic ensemble. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 143601 (2019).

Park, J. et al. Direct generation of polarization-entangled photons from warm atomic ensemble. Appl. Phys. Lett. 119, 074001 (2021).

Davidson, O. et al. Bright multiplexed source of indistinguishable single photons with tunable GHz-bandwidth at room temperature. New. J. Phys. 23, 073050 (2021).

Chen, J. M. et al. Room-temperature biphoton source with a spectral brightness near the ultimate limit. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 023132 (2022).

Davidson, O., Yogev, O., Poem, E. & Firstenberg, O. Bright, low-noise source of single photons at 780 nm with improved phase-matching in rubidium vapor, (2023). arXiv:2301.06049.

Craddock, A. N. et al. High-rate subgigahertz-linewidth bichromatic entanglement source for quantum networking. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 034012 (2024).

Dong, M. X. et al. Two-color hyper-entangled photon pairs generation in a cold 85Rb atomic ensemble. Opt. Express. 25, 10145–10152 (2017).

Dong, M. X. et al. Experimental realization of narrowband four-photon Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger state in a single cold atomic ensemble. Opt. Lett. 44, 3681–3684 (2019).

Park, J., Jeong, T., Kim, H. & Moon, H. S. Time-energy entangled photon pairs from Doppler-broadened atomic ensemble via collective two-photon coherence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 263601 (2018).

Park, J. et al. High-visibility Franson interference of time–energy entangled photon pairs from warm atomic ensemble. Opt. Lett. 44, 3681–3684 (2019).

Park, J. et al. Entanglement sweeping with polarization-entangled photon-pairs from warm atomic ensemble. Opt. Lett. 45, 2403–2406 (2020).

Park, J., Kim, H. & Moon, H. S. Four-photon Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger entanglement via collective two-photon coherence in Doppler-broadened atoms. Adv. Quantum Tech. 4, 2000152 (2021).

Aasi, J. et al. Enhanced sensitivity of the LIGO gravitational wave detector by using squeezed states of light. Nat. Photonics. 7, 613–619 (2013).

Treps, N. et al. A quantum laser pointer. Science 301, 940–943 (2003).

Lamine, B., Fabre, C. & Treps, N. Quantum improvement of time transfer between remote clocks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 123601 (2008).

Braunstein, S. L. & Van Loock, P. Quantum information with continuous variables. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77, 513 (2005).

Ast, M., Steinlechner, S. & Schnabel, R. Reduction of classical measurement noise via quantum-dense metrology. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 180801 (2016).

Taylor, M. et al. Biological measurement beyond the quantum limit. Nat. Photonics. 7, 229–233 (2013).

Corzo, N., Marino, A. M., Jones, K. M. & Lett, P. D. Multi-spatial-mode single-beam quadrature squeezed states of light from four-wave mixing in hot rubidium vapor. Opt. Express. 19, 21358–21369 (2011).

Zhang, K., Liu, S., Chen, Y., Wang, X. & Jing, J. Optical quantum states based on hot atomic ensembles and their applications. Photonics Insights. 1, R06–R06 (2022).

Pooser, R. C. et al. Truncated nonlinear interferometry for quantum-enhanced atomic force microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 230504 (2020).

Wu, S. et al. Quantum magnetic gradiometer with entangled twin light beams. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg1760 (2023).

Otterstrom, N., Pooser, R. C. & Lawrie, B. J. Nonlinear optical magnetometry with accessible in situ optical squeezing. Opt. Lett. 39, 6533–6536 (2014).

Dowran, M., Kumar, A., Lawrie, B. J., Pooser, R. C. & Marino, A. M. Quantum-enhanced plasmonic sensing. Optica 5, 628–633 (2018).

Prajapati, N., Niu, Z. & Novikova, I. Quantum-enhanced two-photon spectroscopy using two-mode squeezed light. Opt. Lett. 46, 1800–1803 (2021).

Liu, S., Lou, Y., Xin, J. & Jing, J. Quantum enhancement of phase sensitivity for the bright-seeded SU (1, 1) interferometer with direct intensity detection. Phys. Rev. Appl. 10, 064046 (2018).

Pooser, R. C. & Lawrie, B. Ultrasensitive measurement of microcantilever displacement below the shot-noise limit. Optica 2, 393–399 (2015).

Boyer, V., Marino, A. M., Pooser, R. C. & Lett, P. D. Entangled images from four-wave mixing. Science 321, 544–547 (2008).

Holtfrerich, M. W. & Marino, A. M. Control of the size of the coherence area in entangled twin beams. Phys. Rev. A. 93, 063821 (2016).

Pan, X. et al. Orbital-angular-momentum multiplexed continuous-variable entanglement from four-wave mixing in hot atomic vapor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 070506 (2019).

Liu, S., Lou, Y., Chen, Y. & Jing, J. All-optical entanglement swapping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 060503 (2022).

Pooser, R. C., Marino, A. M., Boyer, V., Jones, K. M. & Lett, P. D. Low-noise amplification of a continuous-variable quantum state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 010501 (2009).

Liu, S., Lou, Y. & Jing, J. Orbital angular momentum multiplexed deterministic all-optical quantum teleportation. Nat. Comm. 11, 3875 (2020).

Chen, Y., Liu, S., Lou, Y. & Jing, J. Orbital angular momentum multiplexed quantum dense coding. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 093601 (2021).

Liu, S., Lou, Y., Chen, Y. & Jing, J. All-optical optimal n-to-m quantum cloning of coherent states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 060503 (2021).

Lukin, M. D., Hemmer, P. R. & Scully, M. O. Resonant nonlinear optics in phase-coherent media. Adv. Mol. Opt. Phys. 42, 347–386 (2000).

McCormick, C. F., Marino, A. M., Boyer, V. & Lett, P. D. Strong low-frequency quantum correlations from a four-wave-mixing amplifier. Phys. Rev. A. 78, 043816 (2008).

McCormick, C. F., Boyer, V., Arimondo, E. & Lett, P. D. Strong relative intensity squeezing by four-wave mixing in rubidium vapor. Opt. Lett. 32, 178–180 (2007).

Ma, R., Liu, W., Qin, Z., Jia, X. & Gao, J. Generating quantum correlated twin beams by four-wave mixing in hot cesium vapor. Phys. Rev. A. 96, 043843 (2017).

Qin, Z. et al. Compact diode-laser-pumped quantum light source based on four-wave mixing in hot rubidium vapor. Opt. Lett. 37, 3141–3143 (2012).

Turnbull, M. T., Petrov, P. G., Embrey, C. S., Marino, A. M. & Boyer, V. Role of the phase-matching condition in nondegenerate four-wave mixing in hot vapors for the generation of squeezed states of light. Phys. Rev. A. 88, 033845 (2013).

Lukin, M. D., Matsko, A. B., Fleischhauer, M. & Scully, M. O. Quantum noise and correlations in resonantly enhanced Wave Mixing based on atomic coherence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 1847–1850 (1999).

Pooser, R. C., Marino, A. M., Boyer, V., Jones, K. M. & Lett, P. D. Quantum correlated light beams from non-degenerate four-wave mixing in an atomic vapor: the D1 and D2 lines of 85Rb and 87Rb. Opt. Express. 17, 16722–16730 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. RS-2023-00283146), the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation (IITP) (No. IITP-2024-2020-0-01606 and IITP-2022-0-01029), and Regional Innovation Strategy (RIS) through the NRF funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) (2023RIS-007).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.S.M. conceived the project. G.S, H.K., and H.S.M. designed the experimental setup and performed the experiments. G.S, H.K., and H.S.M. discussed the results and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sim, G., Kim, H. & Moon, H.S. Intensity-difference squeezing from four-wave mixing in hot 85Rb and 87Rb atoms in single diode laser pumping system. Sci Rep 15, 7727 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86479-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86479-w