Abstract

To alleviate water resource shortages and tensions and meet the water diversion needs of different river basins, buried (cross-dam) pipelines have become an essential component of water diversion projects. They are installed in levee projects in key river basins such as the Yellow River, Jingjiang River, and Beijiang River. Due to the complex engineering structure and multiple sources of vibration excitation, if vibrations propagate along the pipeline axis towards the surrounding levee, they could have an adverse impact on the stability and safe operation of the levee. To accurately identify the vibration and transmission characteristics of the buried pipeline dikes, determine its primary vibration sources, and clarify the propagation laws of pipeline vibrations within the levee, this study, based on prototype observation data and utilizing signal fusion processing technology, investigates the inherent vibration characteristics of the buried pipeline dikes from the perspectives of excitation, transmission, and response. At the same time, by introducing the “finite element-infinite element” theory, a coupled finite element-infinite element model is established for the pipeline, levee, anchor piers, support piers, foundation, and infinite half-space. This model is then used to analyze the site response induced by flow-induced vibration in buried pipeline levee structures. The results show that the primary vibration frequencies of the buried pipeline dike structure are the unit rotation frequency of 74.4 Hz and the blade vibration frequency of 24.8 Hz. These vibration sources originate from the pump unit and propagate outward along the pipeline axis. Using the transmission range of the vibration source as the basis for determining the vibration impact range, it was established that the horizontal vibration impact of the buried pipeline extends 10 m on either side of the pipeline axis, while the vertical vibration impact extends 7.5 m below the dike crest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Given that the buried pipeline-dike system generates coupled vibrations involving the “water flow-pipeline-dike” interaction during actual operation, along with external factors, the buried pipeline experiences complex non-stationary and non-periodic vibration excitations. These excitations propagate along the pipeline and reach the dike soil, potentially causing soil settlement or even collapse, thereby threatening the overall safety and stability of the dike structure. Therefore, it is of great importance to clarify the composition of pipeline vibrations, determine the transmission characteristics of coupled vibrations, study the specific impact of pipeline vibrations on the levee, and define the range of vibration influence.

The vibration characteristics of buried pipeline-dike structures are closely linked to the vibration transmission characteristics of the pipeline. As the primary source of vibration in the buried pipeline-dike system, the vibration characteristics of the pipeline largely determine the overall vibration behavior of the structure. The vibration characteristics of a buried pipeline levee are closely linked to the vibration transmission characteristics of the pipeline. As the primary source of vibration in the buried pipeline levee structure, the pipeline’s vibration properties largely determine the overall vibration characteristics of the structure. In practical engineering applications, pipeline structures are diverse and complex. Straight pipe sections, elbow sections, and curved pipe sections can be flexibly connected, while discrete or continuous support forms can also be selected as needed. Guo et al.1 integrated the Power Flow Method (PFM) with the Finite Element Method (FEM) to establish a vibration transmission model for flexible pipelines. By analyzing the vibration transmission characteristics from a single-point excitation source, they were able to identify the vibration transmission path within the pipeline system. Gao et al.2 utilized the Laplace transform and Transfer Matrix Method (TMM) to study the Turbulence-Induced Vibration (TIV) of clamped-clamped pipe system, while also accounting for the effects of added mass and added damping. The results showed that this approach can accurately identify the frequency response of the pipeline. Chen et al.3 employed the Transfer Matrix Method (TMM) for multi-body systems to investigate the vibration characteristics of composite material pipelines. They found that the stability of the pipeline is correlated with the elastic modulus and shear modulus of the foundation. The results were consistent with ANSYS calculations, demonstrating the effectiveness of the method. Cao et al.4 developed a deep integration of global transfer matrices, hybrid transfer matrices, and variable-precision transfer matrices to address the high-frequency instability problem of long-span pipelines during lateral vibration. Wu et al.5 used a vibration transmission rate function to identify the uplift of sluice bottom plates under different layout methods and noise levels. The results indicated that this method is highly effective in pinpointing the location of uplift. Wang et al.6, based on the operational condition transfer path analysis method, constructed a two-stage vibration transfer model to study the paths with the highest vibration contributions, showing that the vertical damper nodes have the greatest impact on the overall structure’s vibration. However, research on the vibration transmission characteristics of buried pipeline dike structures is still quite limited.

Site vibration refers to the environmental vibrations caused by a vibration source, which propagate outward through the geological strata. These vibrations can easily induce secondary vibrations in nearby structures such as bridges, highways, levees, dams, and residential buildings, posing risks to the safety and stability of these structures and adversely affecting the physical and mental well-being of residents. Wang et al.7 developed a 3D finite element numerical model to investigate the impact of underground train operations on surrounding buildings. Their findings indicated that the vertical vibrations of the buildings showed a decreasing trend from the foundation to the top floors, with larger and less rigid rooms experiencing greater vibration intensities. Zhang et al.8, by introducing the finite-infinite element coupling theory, constructed a semi-infinite space numerical model encompassing the dam and downstream area to study the effects of high dam outflow on downstream sites. Chen et al.9 examined the noise issues caused by urban rail vibrations, analyzing building vibrations and corresponding noise in both time and frequency domains. They discovered a strong positive correlation between structural vibrations and noise. Xu et al.10 established a 2.5D finite element model of high-speed trains in permafrost environments and systematically studied the vibration response patterns under high-speed movement in plateau permafrost conditions. Liang et al.11, using an improved CMSRS method and prototype observation data, analyzed the causes of vibrations accompanying the discharge at the Jinping Hydropower Station. Zhang et al.12 analyzed the differences in vibration characteristics and attenuation relationships of the surrounding ground caused by buses and trains, focusing on the vibration propagation in saturated soil environments. Li et al.13 studied the vibration characteristics of surrounding ground induced by buried pipelines under horizontal lateral excitation, finding that the first natural frequency of the surrounding ground decreased as the input load magnitude increased, and the displacement peak was closely related to non-uniform load excitation. Currently, most studies on site vibration focus on the response of surrounding buildings to vibrations, but they have not employed appropriate methods to determine the vibration impact range of the source.

This study focuses on the buried pipeline-dike structure of a specific water system. Based on prototype observation data of the buried pipeline levee and employing signal fusion processing technology, the research investigates the vibration characteristics of the levee from the perspectives of vibration source composition, vibration transmission direction, and frequency-domain transmission characteristics. The primary vibration sources of the pipeline are identified, the transmission patterns of vibrations between different measurement points are determined, and the vibration transmission path is established. Additionally, a coupled finite element-infinite element model is developed for the pipeline, levee, anchor piers, support piers, foundation, and infinite half-space. Using load inversion theory and actual measurement data, the excitation load is determined, enabling an analysis of site responses induced by flow-excited vibrations in the buried pipeline levee. The study explores the vibration characteristics of the buried pipeline levee structure and identifies the vibration impact range of the buried pipeline on the levee.

Basic theory

Basic theory of EEMD

Due to the nonlinear and non-stationary nature of pipeline vibration signals, traditional frequency domain decomposition methods face significant limitations in their application. To overcome this challenge, the Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (EEMD) method was introduced. This technique improves the continuity of the signal across various time scales by adding Gaussian white noise sequences to the original signal, taking advantage of the uniform distribution of the noise’s frequency spectrum. After processing the signal using EMD, the vibration signal is decomposed into multiple Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs). By performing EMD on signals with different Gaussian white noise sequences multiple times and averaging the corresponding IMF components within the same frequency band, the influence of Gaussian white noise is reduced. This enables a more accurate representation of the true characteristics of the original vibration signal.

The steps for performing EEMD decomposition on the original vibration signal are as follows:

-

(1)

Add Gaussian white noise \(\omega (t)\) to the original signal \({x_c}(t)\), yielding the signal \(x(t)\), as shown below:

$$x(t)={x_c}(t)+\omega (t)$$(1) -

(2)

Apply the Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) to the signal \(x(t)\) to obtain the Intrinsic Mode Functions (IMFs) as follows:

$$x(t)=\sum\limits_{{i=1}}^{n} {{c_i}} (t)+{r_n}(t)$$(2)In the equation, \({r_n}(t)\) is the residual signal, \({c_i}(t)\) is the parameters of the i-th Intrinsic Mode Function (IMF).

-

(3)

Repeat steps (1) and (2) for the j-th iteration (j = 2, 3, …, n), where white noise is added to the original signal in each iteration.

$$\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{l}} {{x_j}(t)={x_c}(t)+{\omega _j}(t)} \\ {{x_j}(t)=\sum\limits_{{i=1}}^{n} {{c_{ji}}} (t)+{r_{jin}}(t)} \end{array}} \right.$$(3)In the equation, \({\omega _j}(t)\) is the white noise added during the j-th iteration, \({c_{ji}}(t)\) represents the iii-th Intrinsic Mode Function obtained from the j-th decomposition.

-

(4)

Based on the principle of uncorrelated random sequences with a statistical mean of zero, perform an overall averaging of the \({c_{ji}}(t)\) values obtained from the multiple iterations. This averaging process helps to cancel out the effects of the added white noise on the IMFs. The final decomposition of the original signal can be expressed as:

$${c_i}(t)=\frac{1}{N}\sum\limits_{{j=1}}^{N} {{c_{ji}}} (t)$$(4) -

(5)

After performing EEMD decomposition, the reconstructed signal xc(t)x_c(t)xc(t) can be expressed as follows:

$${x_c}(t)=\sum\limits_{{i=1}}^{n} {{c_i}} (t)+{r_n}(t)$$(5)

Improved EEMD basic theory

The traditional EEMD method can become computationally complex and less efficient when dealing with longer signal sequences. To address this, the EEMD method has been improved, and in this study, we refer to the modified version as Modified Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition (MEEMD).

For non-stationary signals \(x(t)\), the decomposition steps of the MEEMD method are as follows:

-

(1)

In the original signal \(x(t)\), add Gaussian white noise \({n_i}(t)\) with zero mean, opposite signs, and amplitudes of \({a_i}\). The signals can be expressed as follows:

$$x_{i}^{+}(t)=x(t)+{a_i}{n_i}(t),x_{i}^{ - }(t)=x(t) - {a_i}{n_i}(t)$$(6)In the equations, \({a_i}\) is set to be 0.1 to 0.2 times the standard deviation of the original signal \(x(t)\), \(i=1,2, \cdots ,{\text{Ne}},{\text{Ne}}\) is the number of added white noise realizations, and it is generally chosen to be within 100 iterations.

-

(2)

Perform Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) on \(x_{i}^{+}(t)\) and \(x_{i}^{ - }(t)\) separately to obtain the corresponding components \(\operatorname{IMF} _{{k1}}^{+}(t)\) and \({\text{IMF}}_{{k1}}^{ - }(t)\), and then calculate the ensemble average as follows:

$${{\text{IMF}}_{1}^{\prime }} (t) = \frac{1}{{2~N}}\sum\limits_{{i = 1}}^{{N_{c} }} {\left[ {{{\text{IMF}}_{{il}}^{ + }} (t) + {{\text{IMF}}_{{in}}^{ - }} (t)} \right]}$$(7)Calculate the permutation entropy \({H_P}\)of \({\operatorname{IMF} _1}(t)\), and use the permutation entropy \({H_P}\) to determine whether \(\operatorname{IMF} _{1}^{\prime }(t)\) is an anomalous signal. If the entropy value \({H_P}\) exceeds the predefined threshold of permutation entropy \(\left[ {{H_P}} \right]\), the signal is considered anomalous; otherwise, it is approximately regarded as a stationary signal. Typically, \(\left[ {{H_P}} \right]=0.7\).

-

(3)

If \(\operatorname{IMF} _{1}^{\prime }(t)\) is an abnormal signal, continue executing steps (1) and (2) until the component is no longer classified as an abnormal signal. Once the \(P - 1\) abnormal components have been separated, remove them from the original signal \(x(t)\) to obtain the following:

$$R(t)=x(t) - \sum\limits_{{j=1}}^{{P - 1}} {\operatorname{IMF} _{j}^{\prime }} (t)$$(8)

Perform Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) on the remaining signal \(R(t)\). The resulting components from this decomposition should be arranged in descending order, from high frequency to low frequency.

The MEEMD method avoids the unnecessary ensemble averaging present in the original EEMD method, resulting in components that are more representative of intrinsic mode functions (IMF). This approach also reduces reconstruction errors caused by the addition of white noise and ensures the completeness of the decomposition. The number of ensemble iterations should satisfy the condition \({\varepsilon _n}=\varepsilon /\sqrt N\), where N is the number of ensemble iterations, \(\varepsilon\) is the amplitude of the added white noise, and \({\varepsilon _n}\) is the final standard deviation of the error, defined as the difference between the input signal and the sum of the corresponding IMFs.

Vibration wave transmission theory

Infinite element method for wave propagation problems

When performing dynamic analysis using the finite element method (FEM), fixed boundaries cannot accurately simulate the behavior of an infinite field, as they can cause stress wave reflection and rebound. This leads to wave interference, with superposition and cancellation occurring in specific regions, ultimately affecting the accuracy of the analysis results. To address this issue, the Infinite Element Method (IEM) is introduced. By incorporating damping to absorb energy, this method enables precise simulation of infinite field conditions, allowing for more accurate wave propagation analysis.

The dynamic stress response \(\sigma _{{ij}}^{Z}=(x,y,t)\) generated by the vibration wave \({Z_0}(x,y,t)\) at the interface between the finite element and infinite element consists of two components: the free-field stress generated at the finite element nodes and the damping force generated at the infinite element nodes. The relationship between these three components is as follows:

In the equations,\(\sigma _{{ij}}^{{{Z_0}}}(x,y,t)\) is the free-field stress, \(\sigma _{{ij}}^{{{\text{IBD}}}}(x,y,t)\) is the damping force.

According to the wave propagation theory in a semi-infinite field space, the projections of the free-field stress at the finite element nodes, generated by the vibration wave, can be expressed in terms of both the tangential and normal components as follows:

In the equations, \(\rho\) is the material density, \({c_{\text{s}}}\) is the material shear wave speed, \({z_{\text{s}}}\) is the material compression wave speed, \(\sigma\) is the tangential stress at the finite element nodes, \(\tau\) is the Normal stress at the finite element nodes.

By combining the mechanical properties equations of the finite element damping materials, we can derive the tangential and normal stresses at the infinite element boundary when stress waves are transmitted as follows:

In the equations, \({\sigma ^{\text{v}}}\) is the tangential stress at the infinite element nodes, \({\tau ^{\text{v}}}\) is the normal stress at the infinite element nodes.

Finite element–infinite element coupling theory

The numerical model for solving problems related to finite element-infinite element coupling essentially involves partitioning different computational regions of the model into distinct element types. By establishing the equilibrium equations based on the condition of stress and displacement continuity at the interface between the two types of elements, the stress and displacement components at any node within the unknown field can be solved. The coupling process is as follows:

-

(1)

Establish motion equations for the near field and far field:

$$\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{L_1}(\left\{ {{X^1}} \right\},\left\{ {{F^1}} \right\})=0} \\ {{L_2}(\left\{ {{X^2}} \right\},\left\{ {{F^2}} \right\})=0} \end{array}} \right.$$(12)In the equations, \({L_1}\) is the function relationship related to the near field, \({L_2}\) is the function relationship related to the far field, X is the variable to be solved, F is the interaction force at the interface between the near field and far field, and the subscripts 1 and 2 denote the near field (finite element region) and far field (infinite element region), respectively.

-

(2)

Establish the displacement equation at the interface:

$$\left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {\left\{ {{U^1}} \right\}={f_1}(\left\{ {{X^1}} \right\},\left\{ {{F^1}} \right\})} \\ {\left\{ {{U^2}} \right\}={f_2}(\left\{ {{X^2}} \right\},\left\{ {{F^2}} \right\})} \end{array}} \right.$$(13)In the equations, U is the displacement at the interface, f is the function that describes the relationship between displacement, stress, and the variable to be solved.

-

(3)

Establish the continuity equation at the interface:

$$\left\{ \begin{gathered} \left\{ {{U^1}} \right\}=\left\{ {{U^2}} \right\} \hfill \\ \left\{ {{F^1}} \right\}+\left\{ {{F^2}} \right\}=\left\{ 0 \right\} \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right.$$(14) -

(4)

Jointly Solve Eqs. (12), (13), and (14) to determine the unknown variables in the near field and far field.

Vibration characteristics of buried pipelines in dike projects

The structure of buried pipeline dike engineering is complex, and the interference from multi-source excitations adds difficulty to the analysis of the vibration transmission characteristics of the buried dike structure. Correctly identifying the vibration and transmission characteristics of the buried pipeline dike structure and determining its main vibration sources are prerequisites for conducting subsequent site response analyses. Based on prototype observation data from buried pipeline dikes and incorporating signal fusion processing techniques, this study investigates the vibration characteristics of the buried pipeline dike from the perspectives of vibration source composition, vibration transmission direction, and frequency domain transmission characteristics.

Noise reduction process and feasibility analysis of prototype observation data

To validate the separation effect of the EEMD and MEEMD algorithms in feature information extraction, a noisy signal composed of low-frequency, high-frequency, and white noise components is constructed. The pure signal is represented as \(x(t)\):

The noisy signal is represented as follows:

In this equation, t is the sampling time, with a sampling frequency of 100 Hz and a sampling duration of 10 s, \(\operatorname{randn} ({\text{t}})\) is the random white noise component.

The time history curves and power spectral density (PSD) comparison of the noisy signal\(X(t)\) and the pure signal \(x(t)\) are shown in Figs. 1 and 2, respectively. The separation effects of different algorithms on the pure signal and the noisy signal are illustrated in Figs. 3, 4, and 5.

From Figs. 3 and 5, it can be observed that the improved EEMD exhibits significant advantages in separating low-frequency signals. This method can accurately isolate signal components with final frequencies of 24.8 Hz and 3.2 Hz, which are highly consistent with the preset frequencies of the simulated signal shown in Fig. 2, thereby demonstrating the effectiveness of the improved EEMD in extracting meaningful information from simulated signals. Compared to the traditional EEMD decomposition method, the improved EEMD performs better in terms of separation effectiveness. Traditional methods often encounter varying degrees of mode mixing when processing low-frequency signals, leading to suboptimal separation results. In contrast, the improved EEMD effectively overcomes the mode mixing issue through its unique algorithm design, achieving more precise signal separation.

In order to quantify the effectiveness of the two decomposition methods, MEEMD and EEMD, the RMSE of the two methods was calculated, and the results were 0.1038 and 0.1454, respectively, which once again demonstrated the superiority of the MEEMD method.

Prototype observation and vibration source analysis

Project background

In a specific buried pipeline dike project, the pipeline experiences significant bends and variations, resulting in a complex layout. During the water conveyance process, the internal flow state of the pipeline is intricate, and the irregular water flow impacts the pipe walls, causing vibrations. These vibrations can extend along the pipe axis and also transmit to the dike’s soil. To ensure the safe and normal operation of the buried pipeline dike structure, it is crucial to collect vibration testing data for both the pipeline and dike under different operating conditions. Analyzing the prototype observation data using modern signal processing techniques is key to studying the vibration transmission from the excitation sources and understanding the specific impact range of pipeline vibrations on the dike’s soil. This serves as an important foundation for further analyzing the safety and stability of the buried pipeline dike structure. Figure 6 illustrates the layout of the measurement points collected on-site.

Vibration source analysis

The vibrations generated by the centrifugal pump during the startup and shutdown processes of the buried pipeline dike’s dynamic source are notably intense, containing comprehensive vibration information that is highly representative. This section analyzes the composition of the vibration sources in the buried pipeline dike using measurement point A, which is closest to the excitation source, under different operating conditions. Table 1 presents the prototype observation conditions, while Fig. 7a, b illustrate the frequency spectrum of the prototype observation data at measurement point A under operating conditions 1 and 2, respectively. From Fig. 7a, it can be observed that when the pump station unit is operational, the maximum amplitude of the prototype observation data occurs at 74.36 Hz, which is the primary frequency causing pipeline vibrations. Secondary frequencies are noted at 32.75 Hz and 125.46 Hz. Similarly, during the shutdown of the unit, the primary frequency remains at 74.36 Hz, while secondary frequencies are identified at 38.41 Hz and 98.09 Hz.

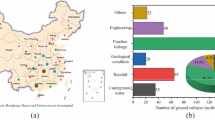

By statistically analyzing the occurrence of different spectral peak values across six measurement points under three operating conditions, the results are summarized in Table 2. Under different working conditions, blade frequency and rotation frequency are the main frequencies of the pipe-penetrating embankment structure, and other frequencies are secondary frequencies. However, the proportion of blade frequency and rotation frequency energy will be different.Based on existing research14,15,16, the composition of vibration sources in this buried pipeline dike project can be categorized as follows: (1) Low-frequency pulsations caused by the impact of slow-moving water flow, within the range of 0–10 Hz; (2) Mid-to-high frequencies, including the unit rotation frequency at 74.4 Hz and the blade vibration frequency at 24.8 Hz; (3) High-frequency vibrations resulting from coupling effects, occurring at frequencies above 90 Hz.

Vibration transmission path analysis

To investigate the transmission direction of vibrations among multiple measurement points, the transfer entropy method is introduced to explore the vibration transmission paths.

Feasibility verification of transfer entropy

To construct vibration signals that more accurately reflect the characteristics of buried pipeline dike engineering, the analysis is based on prototype observation data. The primary vibration sources of the buried pipeline structure are determined using vibration source analysis theory. Two interrelated simulated signals are constructed based on the frequencies of these sources, and the entropy values are calculated for different transmission directions and various time delay scales.

Based on the analysis above, the blade frequency of 24.8 Hz and the rotational frequency harmonic of 74.4 Hz frequently occur across various operating conditions and constitute the primary components of vibration sources. Therefore, let \({f_1}=24.8\) and \({f_2}=74.4\), and construct two simulated signals \({x_1}\) and \({x_2}\) that satisfy the following conditions: (1) Both \({x_1}\) and \({x_2}\) must include the primary frequencies \({f_1}\) and \({f_2}\); (2) In addition to containing all the characteristic information of \({x_1}\), \({x_2}\) must also have information not present in \({x_1}\); (3) The correlation between \({x_2}\) and \({x_1}\) is not fixed. Under these conditions, the simulated signals \({x_1}\) and \({x_2}\) can be expressed as follows:

In this equation, \(\lambda\) is the correlation coefficient.

Let \(\lambda\) take values of 0.1, 0.2, and 0.4, and plot the variation curves of the simulated signals with delay time, as shown in Fig. 8. From Fig. 8, it can be observed that when \(\lambda =0.4\), the \({T_{({x_1} - {x_2})}}\) curve is positioned above the \({T_{({x_2} - {x_1})}}\) curve, indicating that throughout the entire time scale, the information flow from \({x_1}\) to \({x_2}\) is greater than that from \({x_2}\) to \({x_1}\). Moreover, this trend diminishes as the correlation coefficient \(\lambda\) decreases. Therefore, it can be concluded that transfer entropy not only effectively determines the direction of information flow but also quantitatively assesses the correlation between the two information flows. Thus, it can be applied to buried pipeline dam engineering to identify the transmission path of vibrations.

Vibration transmission path analysis

Existing studies have shown that17,18,19,20: (1) The bend sections of pipelines powered by large pumps are subjected to the impact of fluid inertia forces, resulting in strong excitation forces. These excitation forces can superimpose with the vibrations of the pipeline, thereby increasing the hazards associated with pipeline vibrations. (2) At the moment of pump startup or shutdown, the significant changes in instantaneous fluid velocity can lead to the formation of periodic water hammer waves within the pipeline, which propagate along the pipeline axis. (3) Irregular vibrations in the pipeline can affect the physical and mechanical properties of the overlying soil, reducing its density and potentially causing subsidence in the upper soil layers.

Based on the above research findings, we first utilized a MATLAB filter to remove the information in the original vibration measurement data that falls within the frequency band of 0 to 0.5 Hz. Subsequently, we employed a joint denoising method combining MEEMD and SVD for signal decomposition and reconstruction. Finally, we analyzed the transmission path of the main vibration source at the bend of the buried pipeline during startup, using the time series from measurement point B to measurement point C under working condition 1 as an example. Additionally, we examined the vibration transmission directions between the pipeline segment and the overlying soil during shutdown for measurement points D to E, D to F, and E to F under working condition 2. The entropy value variation curves between these measurement points are shown in Fig. 9 (a), (b), (c), and (d), respectively.

From Fig. 9 (a), it is evident that the transmission entropy curve \({T_{(B - C)}}\) is significantly higher than the transmission entropy curve \({T_{(C - B)}}\), indicating that under the operating condition, the pump blade rotational frequency is transmitted from measurement point B to measurement point C. Similarly, the relationships among the transmission entropy curves of measurement points D, E, and F shown in Fig. 9 (b) and (c) indicate that during the shutdown of the pump, the water flow pulsations at the bend are strong, and vibrations are transmitted along the pipe axis to measurement point F while also transferring from measurement point D to the overlying soil. Additionally, Fig. 9 (d) reveals that part of the vibration at point F is transmitted to measurement point E, meaning that the vibration of the overlying soil is caused by the vibrations of the entire pipeline segment that runs through the embankment. Comparing Fig. 9 (b) and (d), we see that the transmission entropy curve between points D and E is completely separate without any overlaps, indicating that the vibration of the overlying soil is primarily transmitted from measurement point E. By analyzing the transmission entropy values between various measurement points under different working conditions, we can conclude that the vibration transmission path of the buried embankment pipeline is as follows: the irregular vibrations generated during pump operation originate from the pump station unit and progressively transmit outward along the pipe axis, leading to energy separation phenomena in the pipeline segment running through the embankment, with some vibration energy transferring to the overlying soil layer.

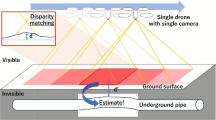

Research on the influence range of vibration from buried embankment pipelines

During the operation of buried embankment pipelines for water supply and drainage, the flow-induced vibrations generated by water flow propagate along the pipe axis and affect the stability and safe operation of the embankment. To accurately reflect the effects of flow-induced vibrations on the buried embankment and clarify the propagation patterns of pipeline vibrations within the embankment, we introduce the “finite element-infinite element” theory. This involves applying infinite element boundaries to establish a coupled finite-infinite element model comprising the pipeline, embankment, town pier, supporting pier, foundation, and infinite half-space. Using load inversion theory, we determine the excitation load based on measured data, allowing us to analyze the site response induced by the flow-induced vibrations of the buried embankment pipeline. By examining the magnitude of vibrations, their characteristics, and incorporating entropy theory, we can delineate the influence range of the buried embankment pipeline’s vibrations on the stability and integrity of the embankment structure.

Due to the proximity of measurement points B and C, both located on the pipeline, the similarity of vibration data in the frequency domain is relatively high. Therefore, when analyzing the vibration transfer characteristics, the multi-scale permutation entropy theory is used to merge the vibration data from points B and C21,22,23,24, creating a new measurement point B. This facilitates the study of the transfer of vibrations through the pipeline site. The distribution of measurement points is shown in Fig. 10.

Establishment of finite element-infinite element coupling model

The finite element numerical model has a width of 60 m, extending 30 m to each side of the pipeline axis. During the calculations, the overall model is treated as an ideal elastic body, with the plastic deformation of related materials disregarded. The finite element model diagram is shown in Fig. 11. Based on actual geological survey data, the finite element model is divided into four layers. The internal finite elements are bound to the boundary infinite elements, achieving coupling between the finite element model and the infinite element boundary. The parameters of the levee strata are listed in Table 3. The mesh size of the numerical model is a critical aspect that requires attention. When the mesh division satisfies the condition that at least eight elements exist within the minimum wavelength, the finite element calculation results align well with the measured data25,26. Considering the primary frequency distribution of pipeline vibrations and ensuring calculation accuracy, the mesh element size is set to 0.2 m.

Verification of finite element-infinite element coupling model

Correctly simulating the entire buried pipeline embankment structure is a prerequisite for subsequent analyses. This section will validate the accuracy of the coupling model from two aspects: the natural vibration characteristics of the model and the model’s response characteristics to excitation.

Verification of natural vibration characteristics

The intrinsic vibration characteristics of a structure determine its response to other dynamic loads and represent its most fundamental attributes. Therefore, before conducting analyses of other dynamic loads, it is necessary to analyze and validate the natural vibration characteristics of the finite element-infinite element coupled model. The Eigensystem Realization Algorithm (ERA) can quickly obtain the modal parameters of a structure and is characterized by its low computational load and high accuracy27,28. Using the ERA algorithm, modal parameter identification is performed on the actual vibration signals from the pipeline and embankment measurement points during pump station operation. The first five natural frequencies of the pipeline are identified and compared with the results calculated from the coupling model, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4 indicates that the calculation results of the finite element-infinite element coupling model are close to the first five modal results obtained from the actual observational data using the Eigensystem Realization Algorithm, with a data error not exceeding 5%. Therefore, the finite element-infinite element coupling model can effectively simulate the true operating conditions of the buried pipeline embankment structure.

Vibration response verification

To ensure that the overall response of the model closely aligns with actual conditions, equivalent loads in three directions were obtained based on the basic theory of load inversion and applied to the finite element model29,30,31,32. The load application locations are shown in Fig. 12, and the time history inversion diagrams of load excitation in three directions are presented in Fig. 13. Response data from measurement points A to F were extracted and compared with the actual measured data at each point, with the variations in vibration intensity across different measurement points presented in Fig. 14. As seen in Fig. 14, the finite element-infinite element coupling model can effectively reflect the vibration response characteristics in all three directions at different measurement points, with the vibration magnitude at the pipeline measurement points being greater than that at the embankment measurement points. The overall average error is only 4.38%, confirming the accuracy of the coupling model.

Using measurement point B as an example, the vibration response extracted from the numerical model is compared with the prototype observation results to further validate the model’s accuracy. The power spectral density of vibration acceleration in all directions at measurement point B is shown in Fig. 15. The figure indicates that most of the energy at measurement point B is concentrated within one or more frequency ranges, with a noticeable presence of high-frequency white noise frequency bands. The dominant frequencies in the X direction are 6.2 Hz, 23.8 Hz, and 74.3 Hz, with vibration energy primarily concentrated in the frequency ranges of 22 Hz to 26 Hz and 74 Hz to 78 Hz. In the Y direction, the dominant frequencies are 51.4 Hz and 74.3 Hz, with energy mainly concentrated in the frequency range of 48 Hz to 80 Hz. In the Z direction, the dominant frequencies are 9.1 Hz, 25.4 Hz, and 74.3 Hz, with energy concentrated in the ranges of 8 Hz to 14 Hz, 24 Hz to 30 Hz, and 72 Hz to 78 Hz. From the results of the coupling model, the primary frequencies and energy concentration ranges in all three directions show minimal variation and are consistent with the prototype data, further confirming the model’s validity.

Analysis of vibration characteristics of buried dike under flow-induced vibration

To investigate the response characteristics of the dike under flow-induced vibration, 36 additional feature points and several characteristic cross-sections were selected for analysis. The locations of the feature points and cross-sections are shown in Fig. 16. The cross-sections are classified into two types: transverse sections parallel to the pipeline axis, such as Section A1F1, and longitudinal sections perpendicular to the pipeline axis, such as Section A1A6. The distance between adjacent feature points in the longitudinal sections is 5 m.

Distribution of vibration intensity in buried dikes

The distribution of vibration acceleration at the characteristic points along the longitudinal sections of the buried dike is shown in Fig. 17. It can be observed that the vibration intensity along the longitudinal sections exhibits a symmetrical distribution centered around the pipe axis. As the distance from the pipe axis increases, the vibration intensity decreases. During the initial stage of vibration propagation, the decay of vibration is relatively rapid; however, when the vibration reaches the transverse sections A2F2 and A5F5, although the vibration energy continues to diminish, the amplitude remains relatively stable.

Among the three directional vibrations, the response in the Y direction is the largest, followed by the Z direction, with the X direction exhibiting the smallest intensity. Thanks to the stabilizing effect of the concrete town foundation, the vibration intensity at the characteristic points along section A1A6 is not significant. The pattern of vibration intensity at the characteristic points along section B1B6 is similar to that of section A1A6, but overall, the vibration intensity is greater in section B1B6. Due to the constraint of the overlying soil on the pipe vibration and its absorption of vibration energy, the vibration intensity at section D1D6 is significantly lower than that of the other sections. The distribution of vibration intensity at section E1E6 is similar to that at section D1D6; however, since it is farther from the excitation source, the overall vibration intensity is low, following a pattern where the intensity is highest at characteristic point F3 and gradually diminishes toward both sides.

To investigate the vertical variation of site response caused by the vibrations of the buried dike pipeline, measurement point 4 is taken as a reference. Below this point, characteristic points are established every 2.5 m, labeled as G1, G2, G3, G4, G5, and G6. A schematic diagram of the vertical characteristic points is shown in Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11, and the variation in vibration responses at these vertical characteristic points is illustrated in Fig. 18.

The changes in vibration response at the vertical characteristic points are shown in Fig. 19. It can be seen that, except for characteristic point G1, which is relatively close to the pipe axis and exhibits higher vibration intensity, the vibration intensities in the three directions at the other characteristic points decrease as the depth of the measurement points increases, although the rate of decay gradually diminishes. The vibration intensity in all three directions reaches a critical value at characteristic point G3, beyond which the changes in vibration intensity are not significant. Therefore, the vertical vibration influence range extends to the area within 7.5 m below the top of the dike.

Vibration frequency distribution characteristics of buried dike

From the perspective of vibration intensity changes, the vibration intensity exhibits different patterns across characteristic points on the longitudinal and transverse sections. For the longitudinal section, the vibration intensity at the characteristic points is symmetrically distributed about the pipeline axis. Additionally, the farther a characteristic point is from the pipeline axis, the lower its vibration intensity. For the longitudinal section, the vibration intensity at the characteristic points first increases and then decreases. Therefore, taking longitudinal section B1B6 as an example, the study investigates the frequency spectrum variation of the surrounding characteristic points induced by site vibration. The acceleration power spectral density curves for each direction at the characteristic points along longitudinal section B1B6 are shown in Fig. 20.

The vibration power spectrum of each characteristic point in the longitudinal section B1B6 is shown in Fig. 20. As shown in the figure, the vibration frequency spectrum distribution and variation patterns in the X and Z directions at each characteristic point are relatively consistent. For the characteristic points closer to the pipeline, the vibration energy is primarily concentrated within a broad range of 16 Hz to 82 Hz. The structural inherent vibration characteristics are predominantly low-frequency, with less pronounced manifestation. As the distance between the characteristic points and the pipeline increases, the high-frequency energy concentration range gradually disappears, and the vibration energy becomes more concentrated (with the main energy frequency band narrowing). The structure’s natural vibration characteristics become more evident, primarily concentrated in the 2 Hz to 10 Hz range. Overall, the vibration energy in all directions at the longitudinal section characteristic points gradually attenuates as the distance from the pipeline increases, and the high-frequency energy concentration zones gradually disappear, indicating a trend towards lower frequencies. This suggests that as the pipeline vibrations propagate outward, the high-frequency vibration energy diminishes. By the time it reaches the characteristic points B2 and B5, the high-frequency vibration energy from the pipeline has completely dissipated, highlighting the low-frequency inherent vibration characteristics of the soil. Coupling this with the variation in vibration acceleration intensity at each point in this section indicates that the energy generated by the irregular vibrations of the pipeline has already dissipated by the time it reaches the characteristic points B2 and B5. Therefore, the horizontal vibration influence range of the buried pipeline is approximately 10 m on either side of the pipeline axis.

Conclusion

-

(1)

The components of the vibration sources in the buried pipeline dam project are as follows: (1) Low-frequency pulsations caused by slow water flow impacts, within the range of 0–10 Hz. (2) Mid to high frequencies from the rotation of the unit at 74.4 Hz and the blade vibration frequency at 24.8 Hz. (3) High-frequency vibrations generated by coupling effects, with a frequency range above 90 Hz.

-

(2)

The transmission path of the primary vibration source in the buried pipeline levee begins at the pump unit and propagates outward along the pipeline axis. Vibration reduction measures, such as anchor piers and support piers, can effectively reduce the transmission of vibration. Under operating conditions, the vibration energy from the pipeline section passing through the levee is mainly transferred to the upper soil layers.

-

(3)

The finite element-infinite element coupling model can accurately simulate the response of the semi-infinite domain of the pipeline dam under load excitation. Except for some individual points, The vibration energy is greatest in the Z direction (vertical), followed by the X direction (along the water flow), with the least energy in the Y direction (perpendicular to the water flow).

-

(4)

The horizontal vibration influence range of the buried pipeline dam extends 10 m on either side of the pipe axis, while the vertical vibration influence range extends 7.5 m below the top of the dam.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the fact that the project is a key project and the data at the measuring points have certain confidentiality but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Guo, X. M., Ma, H., Ge, H., Chen, S. & Wen, B. C. Vibration transmission characteristics analysis of a flexible casing-multiple pipes system. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 217111536. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.YMSSP.2024.111536 (2024).

Gao, C., Zhou, Y. L., Zhang, S. F. & Shi, S. X. Fluid-induced vibration analysis of pipe based on the transfer matrix method and added mass, added damping analogy method. Vibroeng. Procedia 49, 123–129. https://doi.org/10.21595/vp.2023.23347 (2023).

Chen, D. Y., Yang, J. W., Guo, W. C., Liu, Y. J. & Gu, C. J. Vibration study of a composite pipeline supported on elastic foundation using a transfer matrix method. J. Vib. Control 28 (7–8), 853–863. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077546320985370 (2022).

Cao, Y. H., Liu, G. M. & Hu, Z. Stability improvement of the transfer matrix method when calculating the high requency vibration of a pipeline conveying fluid. J. Vib. Shock 43 (02), 138–145. https://doi.org/10.13465/j.cnki.jvs.2024.02.015 (2024).

Wu, D. F., Xiang, H., Liu, C. Q., Shen, B. B. & Zeng, M. Y. Void-underneath identification method of cement concrete pavement using vibration transmissibility function. J. Beijing Univ. Technol. 50 (04), 453–465. https://doi.org/10.11936/bjutxb2022110018 (2024).

Wang, X. Y. Analysis of Dynamic Response and Vibration Transmission Path Contribution of High-Speed Railway Vehicles (Shijiazhuang Tiedao University, 2023).

Wang, L., Gao, X., Zhao, C. Y., Wang, P. & Li, Z. L. Vibration transfer from underground train to multi-story building: modelling and validation with in-situ test data. Undergr. Space 19, 301–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.undsp.2024.04.004 (2024).

Zhang, Y., Lian, J. J., Li, S. H. & Liu, F. Analysis of ground vibration propagation problems induced by high dam flood discharge using finite-infinite element coupled method. J. Vib. Shock 37 (15), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.13465/j.cnki.jvs.2018.15.003 (2018).

Chen, J. L. et al. Train-induced vibration and structure-borne noise measurement and prediction of low-rise building. Buildings 14 (9), 2883–2883. https://doi.org/10.3390/BUILDINGS14092883 (2024).

Xu, X. Y. Study on Near-Field Barrier is Olation and Ground Vibration Induced by Trainload in Frozen Field Using 2.5d Finite Element Method (Harbin Institute of Technology, 2019).

Liang, C. Research on Vibration Mechanism and Reduction Methods for Structures and Surrounding Ground under Excitations Generated by High Dam Flood Discharge (Tianjin University, 2020).

Zhang, Y., Zheng, X., Pang, W. X. & Li, B. Test analysis of ground vibration in saturated soil site caused by train. J. Heilongjiang Bayi Agric. Univ. 29 (01), 115–118 (2017).

Li, L. Y. et al. Analysis of site responses during shaking table test for the interaction between pipeline and soil. Earthq. Eng. Eng. Dyn. 35 (03), 166–176. https://doi.org/10.13197/j.eeev.2015.03.166.lily.021 (2015).

Zhang, J. W., Li, Z. Y., Yan, P., Li, Y. & Huang, J. L. The method for determining optimal analysis length of vibration data based on improved multiscale permutation entropy. Shock Vib. 134 (6), 156–173. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6654089 (2021).

Zhang, J. W., Hou, G., Cao, K. L. & Ma, B. Operation conditions monitoring of flood discharge structure based on variance dedication rate and permutation entropy. Nonlinear Dyn. 93 (4), 117–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-018-4339-2 (2018).

Krause, P. Chapter 5—Vibration Induced by Pressure Waves in Piping (Elsevier Science & Technology, 2014).

Ren, W. C. et al. Hydraulic characteristics of bifurcated pipes. J. Hydroelectric Eng. 41 (04), 28–36 (2022).

Yang, X. W., Lian, J. J., Wang, H. J. & Luo, L. W. Study on forced flow vibration induced by high-frequency pipe wall vibration. J. Hydroelectric Eng. 41 (06), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.11660/slfdxb.20220611 (2022).

Sun, W. Q. & Zheng, Z. Z. Nonlinear dynamic analysis of hydropwer generator shaft system under foundation excitations. J. Hydroelectric Eng. 39 (3), 96–105. https://doi.org/10.11660/slfdxb.20200310 (2020).

Zhang, J. W., Zhang, Y. N., Cheng, M. R. & Wang, L. B. Chaotic characteristic analysis of the vibration responses of pumping station pipelines under overflow conditions. J. Vib. Shock 41 (02), 290–296. https://doi.org/10.13465/j.cnki.jvs.2022.02.035

Li, Z. Y. Study on the Vibration Response of Dike Crossing Pipeline Based on Empirical Wavelet Transform and Time-wavelet Scaling Spectrum (North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power, 2023).

Li, X. R. Research on Surrounding Rock Stability and Safety Early Warning of Underground Powerhouse Based on Data Driving (North China University of Water Resources and Electric Power, 2022).

Zhang, J. W., Li, X. R., Yan, P. & Wang, Y. Surrounding rock stability monitoring based on cusp catastrophe theory and MWMPE. J. Vib. Meas. Diagn. 41 (06), 1199–1205. https://doi.org/10.16450/j.cnki.issn.1004-6801.2021.06.023 (2021).

Mohammadiha, O. & Ghariblu, H. Theoretical analysis of functionally graded thickness tubes under dynamic external inversion loading. Int. J. Impact Eng. 110, 162–170 (2017).

Davis, R. N., Neely, A. M. & Jones, S. E. Mass loss and blunting during high-speed penetration. Proc. Institution Mech. Eng. C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 218 (9), 1053–1062. https://doi.org/10.1243/0954406041991189 (2004).

Chen, X. W., Yang, S. Q. & He, L. L. Modeling on mass abrasion of kinetic energy penetrator. Chin. J. Theor. Appl. Mech. 41 (05), 739–747. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:0459-1879.2009.05.017 (2009).

Pu, Q. H., Hong, Y., Wang, G. X. & Li, X. B. Fast eigensystem realization algorithm based structural modal parameters identification for ambient tests. J. Vib. Shock 37 (06), 55–60. https://doi.org/10.13465/j.cnki.jvs.2018.06.009 (2018).

Cui, D. Y., Xin, K. G. & Qi, Q. Q. Modal parameter identification research for the extended eigensystem realization algorithm. Eng. Mech. 30 (08), 49–53. https://doi.org/10.6052/j.issn.1000-4750.2012.04.0234 (2013).

Li, H. K., Wang, G., Wei, B. W., Huang, W. & Chen, L. J. Inversion method for dynamic elastic modulus of arch dam prototype based on sensitivity analysis and particle swarm optimization algorithm. J. Water Resour. 51 (11), 1401–1411. https://doi.org/10.13243/j.cnki.slxb.20200155 (2020).

Ma, B., Ge, J. Z., Liang, S. & Lian, J. J. Study on the vibration characteristics of foundation sites induced by high arch dam discharge and optimization of discharge schemes. J. Tianjin Univ. (Nat. Sci. Eng. Technol. Ed.) 53 (01), 27–34 (2020).

Wang, H. J., Mao, L. D. & Lian, J. J. Research on vibration prediction of hydroelectric power plant structures based on RVM method. Vib. Impact 34 (03), 23–27. https://doi.org/10.13465/j.cnki.jvs.2015.03.004 (2015).

Li, H. K., Liu, S. L., Wei, B. W., Huang, J. L. & Fu, X. Research on the fusion method of multi measurement point dynamic response of discharge structures based on variance contribution rate. Vib. Shock 34 (19), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.13465/j.cnki.jvs.2015.19.029 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Lihui Gao: Conceptualization, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Visualization. Jing Xu: Conceptualization, Resources, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Data Curation. Shuai Xing: Conceptualization, Resources, Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, L., Xu, J. & Xing, S. Study on the vibration characteristics and influence range of buried dam pipeline. Sci Rep 15, 2323 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86545-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86545-3