Abstract

The g-C3N4/CS biosensor was designed, fabricated, and tested using compounds such as glucose, urine, lactose, and flutamide at a molarity of 10 µM, which could demonstrate a high sensitivity of 200 μm-1 for flutamide. Powerful effective medium theory and FDTD simulation were used to predict the most favorable mode and plasmonic properties of a graphite carbon nitride and chitosan nanocomposite. The research also explores the characteristics of surface plasmon resonance exhibited by the nanocomposite as the chitosan content is adjusted. Subsequent simulations are conducted on nanocomposites incorporating a thin layer and a modified gold structure. The intricate simulations ultimately reveal the optimal combination, tested under three different pH conditions (6.2, 7.2, and 8). In acidic conditions, the kinetic profile yielded a KD= 3.45 × 10−7, surpassing the KD value of a thin film. The Au significantly outperformed the alternative material. The biosensor demonstrated linear behavior across a wide concentration range from 1 to 150 µM, achieving a detection limit of 120 nM with its high sensitivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A significant improvement in our ability to regulate diseases due to the quick diagnosis of these conditions has been seen in recent years1,2. The well-known surface plasmon resonance (SPR) is one useful tool for researching molecule interactions3,4. The technique is used in drug discovery5, clinical diagnostics6, and other domains as a transducer in affinity sensors7. One can use the label-free approach for SPR imaging or integral measurements8,9. The several uses of the method, including the detection of electrochemical processes such as ion adsorption and nucleation, have been covered in a great deal of papers and reviews10,11. 4-nitro-3-trifluoromethyl-isobutilanilide, or flutamide (FLT), is a non-steroidal anti-androgen that controls the release of testosterone12,13. It is commonly prescribed for managing prostate cancer, with a typical dosage of 250 mg taken three times daily to restrict testosterone production by prostate cancer cells14,15. FLT is also used in screening assays and identifying endocrine disruptors. Side effects of FLT may include gynecomastia and tenderness, and the drug typically becomes bioavailable within 1 to 2 h after consumption16,17.

Much research has focused on FLT sensing from many perspectives. For example, Yiran Luo et al. used an electrocatalyst formed by a composite of carbon particles and tungsten disulfide for the electrochemical detection of flutamide18 with a low sensitivity for environmental application. Also, Afshan Mehrabi et al. by cyclic voltammetry and differential pulse voltammetry tried the electrochemical behavior of the FLT as its selectable sensing19. In another work, rGO nanosheets covered molybdenum tungsten electrodes claiming real-time detection of FLT with the lowest detection limit 20. The fluorescent property of nitrogen/sulfur co-doping of carbon quantum dots was utilized for FLT determining in the environment and pharmaceutical tablets20. By studying the works for FLT sensing, one infers that the challenge is wide with its details in applications variety, sensing conditions such as selectivity, sensing range, linearity, and so on.

Two-dimensional materials like graphene, graphene oxide, and graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) have attracted a lot of attention from the scientific community recently because of their electrical and optical characteristics as well as their potential as substrates for composite matrices. Because of its great chemical and thermal durability, g-C3N4, a polymeric semiconductor with an optical band gap of 2.7 eV, has been demonstrated to have advantageous physical and chemical characteristics as well as a high reduction potential21,22,23,24. Like graphite, g-C3N4 is primarily composed of carbon and nitrogen with sp2 hybridization25. It is a member of the class of carbon nitrides that are distinguished by their distinct covalent bonding between atoms26. Because g-C3N4 contains heptazine and tri-s-triazine rings, it is thought to be the most stable type of carbon nitride27,28. Its structure consists of tri-s-triazine units organized in a π-conjugated planar layered framework, which offers remarkable resistance to acidic and alkaline conditions and thermal stability up to 600 ºC. Due to the strong condensation capacity of the tri-s-triazine rings, which are joined by weak van der Waals forces between layers, g-C3N4 is an indirect semiconductor with exceptional photocatalytic and electrocatalytic capabilities13,29. Conversely, chitosan is a biopolymer formed from chitin that is non-toxic, biocompatible, bioactive, and biodegradable30. It is used in a wide range of sectors including water treatment, paper, textiles, food, medicine, and agriculture due to its special properties31,32. Furthermore, chitosan is a well-liked option for developing sensors and biosensors due to its superior film-forming properties33,34. Also, it is a prime contender for biological material receptors due to its amino bonding and capacity to fortify composite structures35,36. SPR sensors are highly sensitive to minute changes in molecule concentration, as they rely on alterations in the refractive index of the near-surface environment. Unlike fluorescent techniques that necessitate the labeling of molecules37, SPR can detect biological interactions without the need for additional materials, saving time and money. Additionally, SPR sensors offer real-time monitoring of interactions, allowing for the observation of dynamic changes over time38. They also require small sample volumes, making them suitable for applications with limited or costly samples. Furthermore, this non-destructive method can be applied to living or sensitive samples without causing harm39.

The study utilized the effective medium theory to simulate a composite material incorporating graphitic carbon nitride through the surface plasmon resonance method. By altering the composition to include chitosan, the final composite was examined using SEM, FT-IR, and XRD techniques. The composite was then tested by kinetic parameter under varying pH conditions, with the most optimal linear response achieved at a pH of 6.2, demonstrating a sensitivity of 200 μm−1.

Method and designing

Material

For the purpose of making phosphate buffer solution (PBS), sodium phosphate dibasic (Na2HPO4), sodium phosphate monobasic (NaH2PO4), and urea (CH4N2O, 98%) were acquired from Dr. Tajalli comp. Flutamide (C11H11F3N2O3) was acquired from Taiwan’s Sigma Aldrich. No purification was performed; all reagents were used exactly as received.

The study utilized double-distilled and deionized water, with chitosan supplied by Sabz Gostaresh Azin Turkan in Maragheh, Iran. The synthesis of g-C3N4 involved the bottom-up method, where small particles were used to create complex structures40. In contrast, the top-down method involved breaking down large materials into smaller particles and thin nanosheets41. The bottom-up approach included techniques such as ionic liquid, supramolecular pre-assembly, and hydrothermal methods to synthesize g-C3N4 sheets on a large scale through thermal polymerization or carbonization of small organic compounds like melamine, cyanimide, Dicyanamide, or urea. Dante et al. obtained g-C3N4 by pyrolyzing melamine cyanurate at 650 ◦C for 50 min under atmospheric conditions for glucose sensing42. The top-down approach utilized chemical exfoliation and ultrasonic exfoliation methods, with chemical exfoliation being preferred for its efficiency and ability to adjust the g-C3N4 structure easily for large-scale production43,44.

Device of analysis

Using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å), XRD (XPERT-PRO, Pan Analytical B.V., The Netherlands) was used to analyze the crystal structure of the produced sample. FTIR analysis of the functional group presence was conducted with a JASCO FT-IR 4600LE spectrometer. The SEM (JSM-6510) was used to examine the microstructure and surface morphology. utilizing energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) to examine the chemical composition. Moreover, we also used the Bionavis SPR 210 device for kinetic testing.

Modification of biosensor

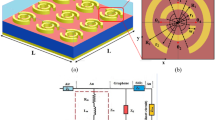

The g-C3N4/CS/Au SPR sensing medium was made by carefully following a methodical process. First, 3 ml of CS was dissolved in 3 ml of 1% acetic acid solution. Next, this solution was supplemented with an extra 3 mg of g-C3N4. The mixture was ultrasonically agitated for 5 h to guarantee a consistent dispersion throughout. Next, using the spin coating process, a small amount (25 µL) of the resultant blend was carefully placed onto a gold layer and allowed to dry entirely45. The outcome was the successful development of an exquisitely precise and elegant g-C3N4/CS /Au SPR sensing medium (see Fig. 1a).

Optimization of biosensor

To enhance the sensitivity of the biosensor, the effective medium theory was applied to a composite of graphitic carbon nitride and varying percentages of chitosan (10%, 20%, and 30%)44. Surface plasmon resonance and resonance angle changes were utilized due to their high sensitivity to surface alterations. The biosensor was simulated using the FDTD method46, showing different states such as modified surface in five scenarios47, as illustrated in Fig. 1b.

Result

Surface measurement

The sample had sheet-like structures, as seen by the subsequent SEM image (Fig. 2a), with CS particles linked to g-C3N4 sheets that had a diameter of around 30 nm. The elements C, N, and O were found in the composite, with weight percentages of 37.89%, 56.07%, and 6.04%, respectively, according to an elemental analysis (Fig. 2b). Also, after injecting flutamide onto the composite, EDS was prepared, which is shown in Fig. 2c. The results showed that the presence of F and O atoms in the flutamide structure was clearly seen in EDS. In the measured 2θ range, the XRD pattern of chitosan exhibited a broad diffraction peak at 2θ around 21 that is characteristic fingerprint of semi-crystalline chitosan. The peaks at 12.8° and 27.6° in g-C3N4 are in good accordance with those reported in literature. The more intense peak at 27.6° is attributed to (002) plane due to stacking of layers in conjugated aromatic system. The less intense peak at 12.8°, however, seems well to the layered packing structure of tri-s-triazine units, assigning to (100) plane in JCPDS 87–1526 card. XRD pattern of drug loaded nanocomposite provides some typical peaks of Flutamide at 2θ of 9° to 25.3° but not all of them, representing well dispersion of drug particles within the nanocomposite matrix (see Fig. 2d)47,48. The FTIR spectra of the g-C3N4, CS, g-C3N4/CS and g-C3N4/CS/FLT samples are depicted in Fig. 2e. The distinctive peaks of CS and g-C3N4 were identified in the g-C3N4/CS sample49. The CS sample exhibited strong absorption peaks at 1024 and 1068 cm-1 attributed to the C-O stretching vibration of alcoholic hydroxyl groups50. The presence of N-H breathing modes in the 3000–3600 cm–1 range suggests the presence of surface N–H or NH2 groups. Peaks in the 1200–1600 cm-1 region indicate the stretching vibration of the aromatic CN heterocycle, while bands at 810 cm–1 are linked to the respiratory vibration of the heptazine units. XRD analysis confirmed the successful combination of g-C3N4 and CS, as shown in Fig. 2d and f alongside the FTIR data34,51.

Optimization of the flow rate

Initially, we assessed the performance of the biosensor when exposed to different concentrations of FLT (0.1, 1, and 10 µM). At FLT concentrations of 1 and 10 µM, there was a change in the surface plasmon resonance angle, and no reaction was observed compared to 0.1 µM52. To address the mass transport limitation (MTL) effect in analytical studies, flow rate optimization was deemed necessary. MTL occurs when an analyte binds to the immobilized ligand faster than it diffuses to the biosensor’s surface, impacting kinetic parameters53,54. Various flow rates of FLT were tested to optimize this parameter. The response curve for Ka was consistent across all flow rates except for 10 µL min−1. A smoother exponential curve and reduced signal were observed at a flow rate of 10 µL min−1. However, there was no significant difference in the reaction between flow rates of 30 µL min−1, 40 µL min−1, and 50 µL min−1 (1 µM). Similarly, there was no notable difference in the dissociation rate with flow rates ranging from 30 to 330 s. A slower flow rate appeared to allow FLT to remain on the composite surface longer for binding, as evidenced by a longer dissociation time indicating interaction between FLT and the composite material. A flow rate of 10 µL min−1 was ultimately chosen for further testing due to its strong RU signal and minimal MTL.

Assessment of the kinetic parameters

Figure 3 shows the interactions between the composite and various concentrations of FLT. It was observed that at higher concentrations of FLT, the association process occurred more rapidly in the optimized conditions (pH 6, 25 °C) resulting in ka and kd values of 1.27 × 103 (Ms)–1 and 4.39 × 10-4 s–1, respectively. A low KD value of 3.45 × 10–7 indicated a strong affinity of the FLT-specific g-C3N4/Cs for FLT. Our findings suggest that the biotinylated composite is suitable for clinical evaluation in blood serum. The values of KD and KA were used to calculate ΔGb using specific Equations55,56.

The universal gas constant (R) is 8.314 J.K−1 mol− 1, where KA represents the affinity constant (1/KD) and T is the temperature in Kelvin. At a temperature of 298 K, the value of ΔGb for FLT and its specific composite interaction was − 30.486 kJ mol−1. The negative ΔGb value suggests that the interaction between FLT and the specific g-C3N4/CS is spontaneous57.

Figure 3 illustrates that the biosensor performs better under acidic conditions compared to other environments. The improved linear relationship is attributed to the absorption of hydrogen protons by the active groups in the g-C3N4 structure at pH 6.2, resulting in the formation of hydrogen groups. This transformation enhances the photocatalytic activity of g-C3N4 by facilitating the reaction with water to produce hydrogen and oxygen58. Conversely, in a neutral environment, the active groups in the g-C3N4 structure absorb hydroxide electrons and convert them into hydroxide groups59,60. This alteration diminishes the photocatalytic efficiency of g-C3N4 as the hydroxylated groups compete with the primary catalytic groups, hindering the photocatalysis process.

Calibration curve for FLT

The range of detection for the SPR-based biosensor designed for clinical diagnosis of FLT was evaluated by testing concentrations from 1 to 150 µM. The flow rate remained constant at 10 µL min−1, and the experiments were carried out at a temperature of 25 °C. Each concentration was injected four times to create a calibration curve for FLT concentrations. The study was performed in phosphate buffer solutions with varying pH levels (7.2, 6.2, and 8). The linear regression equations for pH 7.2 and pH 8 were y = 0.0002x + 0.0042 (R2 = 0.933) and y = 0.0001x + 0.0048 (R2 = 0.902), respectively. The buffer at pH 6.2 (y = 0.0002x + 0.0035, R2 = 0.9839) was identified as the optimal flow buffer. At higher FLT concentrations, the system response rose linearly; concentrations beyond 150 µM resulted in a plateau, mainly because the biosensor surface’s active sites were saturated. With a linear range of 1 to 150 µM and a calculated Limit of Detection (LOD) of 0.12 µM, this sample is appropriate for use in clinical settings. All experiments have been performed 5 times and the average results are reported.

Selectivity and stability of the biosensor

The g-C3N4/CS biosensor was tested using compounds such as glucose, urine, lactose, and flutamide at a molarity of 10 µM to evaluate its performance. Figure 4 displays the results, showing that the flutamide sensor produced a stronger signal compared to other compounds that were more susceptible to interference. The stability of the biosensor was also assessed at different times (1, 10, and 20) throughout the day at room temperature (25 °C) in a controlled environment. The results, depicted in Fig. 4 as an average of 3 measurements, revealed that the biosensor experienced less than a 3% reduction in performance over the course of the test, which was conducted with 3 repetitions. The stability of the composite can be attributed to the stability of graphitic carbon nitride and chitosan, as well as the conditions of the measurement environment61,62.

Ganesh et al. demonstrated that Flutamide can be reduced on exfoliated g-C3N413. The reduction of the FLT on g-C3N4 is facilitated by the evanescent field generated by the SPR. This field can influence the analyte up to 700 nm and trap it for reduction on g-C3N4. The evanescent field for thin films of gold and modified gold thin films is illustrated in Fig. 5. It was observed that with a thin layer of gold, the evanescent field can reach the analyte up to 200 nm. However, when a modified gold layer is used to sensing of analyte, the evanescent field can extend up to approximately 700 nm. This indicates that the field in the analyte environment, along with the trapping of Flutamide on the sensing substrate, enhances the reduction potential.

Also, in the following, the results of the designed biosensor are compared with previous research and are displayed in Table 1.

Real sample detection

The real sample was prepared using the gravity filtration procedure. The selective filter utilized was 0.45 micron. Without pausing, the river water moved steadily through the filter. We used the HPLC method to measure the FLT of the original sample, which was measured in five cases. The average of the measurements was 45.3 µM, which was raised to 100 µM by adding FLT to the sample (TDS: 590). diluted solutions were made using M1V1 = M2V2, and the results are shown in Table 2.

Conclusion

The purpose of the work was to improve the performance of an SPR biosensor employing g-C3N4/CS, a composite of g-C3N4 and CS. To precisely identify FLT, the researchers optimized the composition and flow rate of analytes by theoretical and experimental assessments. When exposed to FLT solution, the SPR sensor with the g-C3N4/CS thin film outperformed the unmodified gold chip with better signal fluctuations. Additionally, the sensor’s sensitivity increased by 200, allowing it to identify FLT at a low concentration of 0.12 µM. The potential of g-C3N4-based biosensors for biological applications is demonstrated by this work.

Data availability

Data will be available upon reasonable request by corresponding author: Hassan Nasiri (h.nasiri@tabrizu.ac.ir).

References

Council, N. R., Earth, D., Studies, L., Diagnosis, C. & Disease, C. o. o. J. s. Diagnosis and control of Johne’s disease. (2003).

Swami, S., Kayenat, F. & Wajid, S. SPR biosensing: Cancer diagnosis and biomarkers quantification. Microchem. J. 197, 109792 (2024).

Altug, H., Oh, S. H., Maier, S. A. & Homola, J. Advances and applications of nanophotonic biosensors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 5–16 (2022).

Loyez, M., Ribaut, C., Caucheteur, C. & Wattiez, R. Functionalized gold electroless-plated optical fiber gratings for reliable surface biosensing. Sens. Actuators B. 280, 54–61 (2019).

Mohan, S., Kato, E., Drennen, I. I. I., Anderson, C. A. & J. K. & Refractive index measurement of pharmaceutical solids: a review of measurement methods and pharmaceutical applications. J. Pharm. Sci. 108, 3478–3495 (2019).

Wang, J., Maier, S. A. & Tittl, A. Trends in Nanophotonics-enabled optofluidic biosensors. Adv. Opt. Mater. 10, 2102366 (2022).

Halima, H. B. & Errachid, A. Jaffrezic-Renault, N. Electrochemical affinity sensors using field effect transducer devices for chemical analysis. Electroanalysis 35, e202100451 (2023).

Gade, A., Sharma, A., Srivastava, N. & Flora, S. Surface plasmon resonance: a promising approach for label-free early cancer diagnosis. Clin. Chim. Acta. 527, 79–88 (2022).

Zhang, P. et al. Label-free imaging and biomarker analysis of exosomes with plasmonic scattering microscopy. Chem. Sci. 13, 12760–12768 (2022).

Kesavan, G., Pichumani, M. & Chen, S. M. Influence of crystalline, structural, and electrochemical properties of iron vanadate nanostructures on flutamide detection. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 4, 5883–5894 (2021).

Nataraj, N. et al. Electrochemical detection of anti-cancer drug flutamide in biological fluids with calcium molybdate/molybdenum oxide as an effective electrocatalyst. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 156, 105348 (2024).

Kesavan, G. & Chen, S. M. Highly sensitive manganese oxide/hexagonal boron nitride nanocomposite: an efficient electrocatalyst for the detection of anti-cancer drug flutamide. Microchem. J. 163, 105906 (2021).

Kesavan, G. & Chen, S. M. Sonochemically exfoliated graphitic-carbon nitride for the electrochemical detection of flutamide in environmental samples. Diam. Relat. Mater. 108, 107975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diamond.2020.107975 (2020).

Stefanucci, A. et al. Assessment of the in-vitro toxicity and in-vivo therapeutic capabilities of Juglans regia on human prostate cancer and prostatic hyperplasia in rats. Food Bioscience. 57, 103539 (2024).

Student, S., Hejmo, T., Poterała-Hejmo, A., Leśniak, A. & Bułdak, R. Anti-androgen hormonal therapy for cancer and other diseases. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 866, 172783 (2020).

Sarrabay, A. et al. Low dose evaluation of the antiandrogen flutamide following a Mode of Action approach. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmcol. 289, 515–524 (2015).

Jyothi, B. J. & Sreelakshmi, K. Design and evaluation of self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system of flutamide. J. Young Pharmacists. 3, 4–8 (2011).

Luo, Y., Kasturi, P. R., Barwa, T. N., Dempsey, E. & Breslin, C. B. Amplifying Flutamide sensing through the Synergetic Combination of Actinidia-Derived Carbon particles and WS2 platelets. ACS Omega. 9, 29598–29608 (2024).

Mehrabi, A., Rahimnejad, M., Mohammadi, M. & Pourali, M. Electrochemical detection of flutamide with gold electrode as an anticancer drug. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 22, 101375 (2019).

Abd-AlGhafar, W. N., Shabana, R. A., El-Shaheny, R. & Tolba, M. M. A fluorescence switch-off nanosensor for sensitive determination of the antiandrogen drug flutamide in pharmaceutical and environmental samples. Analytical method greenness, blueness, and whiteness assessment. Microchem. J. 204, 111078 (2024).

Wang, Y., Liu, L., Ma, T., Zhang, Y. & Huang H. 2D graphitic carbon nitride for energy conversion and storage. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2102540 (2021).

Ismael, M. A review on graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) based nanocomposites: synthesis, categories, and their application in photocatalysis. J. Alloys Compd. 846, 156446 (2020).

Politano, G. G. & Versace, C. Electrical and optical characterization of graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide thin films. Crystals 12, 1312 (2022).

Singh, A. et al. Graphene oxide-chitosan nanocomposite based electrochemical DNA biosensor for detection of typhoid. Sens. Actuators B. 185, 675–684 (2013).

Zhou, Y. et al. N-doped graphitic carbon-incorporated g-C3N4 for remarkably enhanced Photocatalytic H2 evolution under visible light. Carbon 99, 111–117 (2016).

Niu, W. & Yang, Y. Graphitic carbon nitride for electrochemical energy conversion and storage. ACS Energy Lett. 3, 2796–2815 (2018).

Kumar, S., Battula, V. R. & Kailasam, K. Single molecular precursors for CxNy materials-blending of carbon and nitrogen beyond g-C3N4. Carbon 183, 332–354 (2021).

Shi, X., Pan, Y. & Liu, C. Polysaccharides derived from Ganoderma Lucidum applied to the extraction chitosan and development of electrochemical sensor based on extracted chitosan and graphitic carbon nitride modified electrode for determination nitrite in food samples. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 19, 100446 (2024).

Hayat, A. et al. Graphitic carbon nitride (g–C3N4)–based semiconductor as a beneficial candidate in photocatalysis diversity. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy. 47, 5142–5191 (2022).

(!!! INVALID CITATION !!! (Hayat et al. Zhang, 2023)). (2022).

Picos-Corrales, L. A. et al. Chitosan as an outstanding polysaccharide improving health-commodities of humans and environmental protection. Polymers 15, 526 (2023).

Gal, M. R., Rahmaninia, M. & Hubbe, M. A. A comprehensive review of Chitosan applications in paper science and technologies. Carbohydr. Polym. 309, 120665 (2023).

Nasiri, H., Baghban, H., Teimuri-Mofrad, R. & Mokhtarzadeh, A. Chitosan/polyaniline/graphene oxide-ferrocene thin film and highly-sensitive surface plasmon sensor for glucose detection. Opt. Quant. Electron. 55, 948 (2023).

Nasiri, H., Abbasian, K. & Baghban, H. Highly sensitive quantification of Amlodipine in real samples using graphene oxide-chitosan surface plasmon resonance sensor. Sens. Actuators A: Phys., 115152 (2024).

Ngo, D. H. et al. Biological effects of chitosan and its derivatives. Food Hydrocoll. 51, 200–216 (2015).

Hong, F. et al. Chitosan-based hydrogels: from preparation to applications, a review. Food Chemistry: X, 101095 (2023).

Sohrabi, H. et al. Recent advances of electrochemical and optical biosensors for detection of C-reactive protein as a major inflammatory biomarker. Microchem. J. 158, 105287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2020.105287 (2020).

Kumar, V., Raghuwanshi, S. K. & Kumar, S. Recent advances in carbon nanomaterials based SPR sensor for biomolecules and gas detection—A review. IEEE Sens. J. 22, 15661–15672 (2022).

Pandey, P. S., Raghuwanshi, S. K. & Kumar, S. Recent advances in two-dimensional materials-based Kretschmann configuration for SPR sensors: a review. IEEE Sens. J. 22, 1069–1080 (2021).

Chen, L., Maigbay, M. A., Li, M. & Qiu, X. Synthesis and modification strategies of g-C3N4 nanosheets for photocatalytic applications. Adv. Powder Mater., 100150 (2023).

Abdelhafeez, I. A., Chen, J. & Zhou, X. Scalable one-step template-free synthesis of ultralight edge-functionalized g-C3N4 nanosheets with enhanced visible light photocatalytic performance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 250, 117085 (2020).

Dante, R. C. et al. A solid-state glucose sensor based on Cu and Fe–doped carbon nitride. Mater. Chem. Phys. 258, 124023 (2021).

Pourmadadi, M. et al. Two-dimensional graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) nanosheets and their derivatives for diagnosis and detection applications. J. Funct. Biomaterials. 13, 204 (2022).

Majdoub, M., Anfar, Z. & Amedlous, A. Emerging chemical functionalization of g-C3N4: covalent/noncovalent modifications and applications. ACS nano. 14, 12390–12469 (2020).

Nasiri, H., Abbasian, K. & Baghban, H. Sensing of lactose by graphitic carbon nitride/magnetic chitosan composites with surface plasmon resonance method. Food Bioscience. 61, 104718 (2024).

Sullivan, D. M. Electromagnetic Simulation Using the FDTD Method (Wiley, 2013).

Kirawanich, P., Tzeremes, G., Christodoulou, C., Yakura, S. J. & Islam, N. Electromagnetic wave penetrating through apertures: comparison of electromagnetic topology technique with FDTD method. IEEE Antennas. Wirel. Propag. Lett. 4, 151–154 (2005).

Zhang, X. et al. Direct Z-scheme In2O3/g-C3N4 nanocomposites: breaking through the performance limitations of conventional type II heterojunctions for photocathodic protection of Q235 CS in 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. J. Alloys Compd. 970, 172558 (2024).

Praus, P. et al. Graphitic carbon nitride: synthesis, characterization and photocatalytic decomposition of nitrous oxide. Mater. Chem. Phys. 193, 438–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchemphys.2017.03.008 (2017). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/

Varma, R. & Vasudevan, S. Extraction, characterization, and antimicrobial activity of chitosan from horse mussel modiolus modiolus. ACS Omega. 5, 20224–20230 (2020).

Nasiri, H., Baghban, H., Teimuri-Mofrad, R. & Mokhtarzadeh, A. Graphitic carbon nitride/magnetic chitosan composite for rapid electrochemical detection of lactose. Int. Dairy J. 136, 105489 (2023).

Pinho, B., Torrente-Murciano, L. & Dial‐A‐Particle Precise Manufacturing of Plasmonic nanoparticles based on early growth information—redefining automation for slow material synthesis. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2100918 (2021).

Frimpong, R., Jang, W., Kim, J. H. & Driskell, J. D. Rapid vertical flow immunoassay on AuNP plasmonic paper for SERS-based point of need diagnostics. Talanta 223, 121739 (2021).

Dai, B. et al. Fluid field modulation in mass transfer for efficient photocatalysis. Adv. Sci. 9, 2203057 (2022).

Zheng, G., Mourdikoudis, S. & Zhang, Z. Plasmonic metallic heteromeric nanostructures. Small 16, 2002588 (2020).

Guselnikova, O. et al. Establishing plasmon contribution to chemical reactions: alkoxyamines as a thermal probe. Chem. Sci. 12, 4154–4161 (2021).

Dash, U. C., Swain, S. K., Jena, A. B., Dandapat, J. & Sahoo, A. K. The ameliorative effect of Piper Trioicum in attenuating cognitive deficit in scopolamine induced neurotoxicity in experimental rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 318, 116911 (2024).

Yu, F. et al. Functional groups to modify g-C3N4 for improved photocatalytic activity of hydrogen evolution from water splitting. Chin. Chem. Lett. 31, 1648–1653 (2020).

Wang, N., Cheng, L., Liao, Y. & Xiang, Q. Effect of Functional Group modifications on the Photocatalytic performance of g-C3N4. Small 19, 2300109 (2023).

Wang, D., Chen, J., Gao, X., Ao, Y. & Wang, P. Maximizing the utilization of photo-generated electrons and holes of g-C3N4 photocatalyst for harmful algae inactivation. Chem. Eng. J. 431, 134105 (2022).

Szymańska, E. & Winnicka, K. Stability of chitosan—a challenge for pharmaceutical and biomedical applications. Mar. Drugs. 13, 1819–1846 (2015).

Khajavian, M., Vatanpour, V., Castro-Muñoz, R. & Boczkaj, G. Chitin and derivative chitosan-based structures—Preparation strategies aided by deep eutectic solvents: a review. Carbohydr. Polym. 275, 118702 (2022).

Bhuvaneswari, C. et al. Conniving for the first time of BiVO4–rGO/CE-BN and its potential as enhanced electrochemical sensing of non-steroidal anti-androgen drug. Microchem. J. 184, 108174 (2023).

Kokulnathan, T., Vishnuraj, R., Wang, T. J., Kumar, E. A. & Pullithadathil, B. Heterostructured bismuth oxide/hexagonal-boron nitride nanocomposite: a disposable electrochemical sensor for detection of flutamide. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 207, 111276 (2021).

Borse, S., Murthy, Z., Park, T. J. & Kailasa, S. K. Pepsin mediated synthesis of blue fluorescent copper nanoclusters for sensing of flutamide and chloramphenicol drugs. Microchem. J. 164, 105947 (2021).

Funding

This research is supported by the University of Tabriz by grant no: S/1490.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hassan Nasiri: Software, validation, edit and writing, experience Karim Abbasian: Supervision, Edit and writing, Funding.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Ethical approval

Not included.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nasiri, H., Abbasian, K. Surface plasmon resonance detection of anti-cancer drug flutamide by graphitic carbon nitride/chitosan nanocomposite. Sci Rep 15, 2278 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86665-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-86665-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Ultrasensitive detection of amlodipine using plasmonic optical fiber sensors enhanced with graphene oxide and chitosan nanocomposite

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Monitoring miR-29a for targeted therapy of cholangiocarcinoma based on a photoelectric sensor

Microchimica Acta (2025)

-

Graphene-Enhanced Terahertz Metamaterial Biosensor for Tuberculosis Detection with XGBoost-Based Machine Learning Optimization

Plasmonics (2025)

-

Advanced low loss PCF-based SPR sensor for enhanced sensor length configurations flexibility with exceptional superior sensing performance capability

Applied Physics A (2025)

-

Optical Biosensor for Glucose Detection Based on the Green Synthesis of Silicon Nanoparticles using Ocimum Basilicum Purpurascens Extract

Silicon (2025)